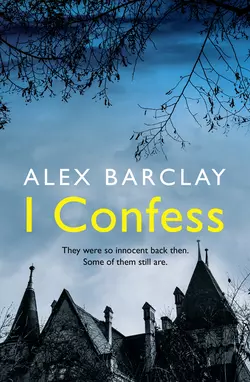

I Confess

Alex Barclay

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1074.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Gripping, stylish, convincing’ Sunday Times They won’t all live to tell the tale… Seven friends. One killer. No escape… A group of childhood friends are reunited at a luxury inn on a remote west coast peninsula in Ireland. But as a storm builds outside, the dark events that marred their childhoods threaten to resurface. And when a body is discovered, the group faces a shocking realisation: a killer is among them, and not everyone will escape with their lives… ‘Almost unbearably tense and shocking’ IRISH INDEPENDENT ‘Compelling…sharply observed’ IRISH TIMES