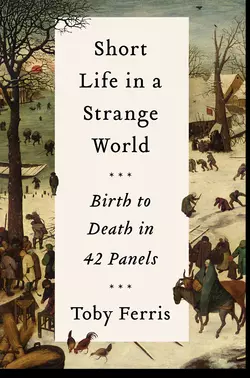

Short Life in a Strange World: Birth to Death in 42 Panels

Toby Ferris

Sure to be hailed alongside H is for Hawk and The Hare with Amber Eyes, an exceptional work that is at once an astonishing journey across countries and continents, an immersive examination of a great artist’s work, and a moving and intimate memoir. At the age of 42, his father not long dead and his young sons growing fast, Toby Ferris set off on a seemingly quixotic mission to track down each of the 42 surviving paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who, at the age of 42, had been approaching the end of his own short life. Over the next five years Ferris would travel to 22 galleries in 19 cities in 12 countries across 2 continents: Budapest to San Diego, Detroit to Naples, Berlin to Madrid, ticking off his Bruegels as he went. The results of his journeying are a revelation: Bruegel’s panels, their landscapes teeming with robust life, become a lens through which Ferris takes stock of the world, informing everything from mortality, fatherhood, and contemporary life, to the bombing of Rotterdam, the extinction of North American megafauna, and how to ward off bears in the forest. Short Life in a Strange World is a dazzlingly original hybrid of art criticism, philosophical reflection and poignant memoir, a book about one man’s obsession with Bruegel’s short life in a strange if familiar world, and the precisely-detailed yet cosmos-encompassing works in ink and oil which sprang from it. And it begins with the story of a boy who fell from the sky.

Short Life in a Strange World

Birth to Death in 42 Panels

Toby Ferris

Copyright (#ulink_64493b9d-c716-5c78-99ef-6d345cbc9594)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Toby Ferris 2020

Toby Ferris asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008340964

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780008340971

Version: 2019-11-06

Dedication (#ulink_3e6fdcd4-6796-5e3e-a3f2-d59f0d637345)

For Simon, Frank and Sid,

and in memory of Robert Henry

Contents

Cover (#u6006781a-3cc3-5c85-9aa2-e4134af60a2b)

Title Page (#u8821265b-f5ef-52d2-a262-e9eb101ed8a2)

Copyright (#u773cc1be-61d4-516e-a9e9-7f9901e7a59b)

Dedication (#ucd4be190-0e90-53e7-9c15-0ff55db2e05e)

The Panels (#u63b267b9-2a56-56c0-8168-8e603de59acc)

I Flight (#u50ac154b-5fa1-512b-819a-9bffa3b9b109)

II Census (#u3fd5d81e-cf78-53d9-b37e-a542cc80bff7)

III Fire (#u6f77520a-9612-5195-b3d5-3d1e0d3a721e)

IV Massacre (#litres_trial_promo)

V Grey (#litres_trial_promo)

VI Beggar (#litres_trial_promo)

VII Cold (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII Bear (#litres_trial_promo)

IX Technique (#litres_trial_promo)

X Gallows (#litres_trial_promo)

XI Singularity (#litres_trial_promo)

XII Crowd (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

List of illustrations (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Panels (#ulink_23a6cc99-d71a-5a16-8d36-faf6ceaa513f)

I Flight (#ulink_88786171-8c97-5297-9d6a-1db54635e6a3)

‘… the boy a frolic courage caught To fly at random …’

Arthur Golding, translating Ovid

I once saw a young man fall from the sky.

I barely knew him. Dan was perhaps twenty, on leave from the army. My girlfriend’s sister, Zabdi, worked as a paragliding instructor on the Isle of Arran, and Dan was a friend of her boyfriend, Chris. And so there we were on a September morning in the late 1990s, Dan and Chris and my girlfriend Anna and Zabdi and I, on the slopes of a green hill on the Isle of Arran, paragliding.

When we picked him up in the minibus, Dan, already a qualified and experienced paraglider, was watching a video of stunt paragliders performing wild manoeuvres, swinging energetically beneath their canopies in figures of eight, looping the loop, skirting crags, skimming lakes, and Dan was clearly inspired. Later, on the mountain, as I was harnessed up and ready to bumble into the air, Zabdi put her hand on my chest and told me to wait: Dan had taken off higher up and was coming overhead. We watched him glide over us for a few seconds, and then, at an altitude of a couple of hundred feet, he started to swing beneath his canopy much as we had seen them do on the video, back and forth, like a pendulum, higher and higher, six, eight swings sweeping out an ever-lengthening arc, just enough time for Zabdi to mutter something under her breath (for fuck’s sake, Dan). Sure enough, he got up too far above his canopy and dropped into it, and in the skip of a heartbeat was tumbling uncontrollably earthward. We watched him fall, lost in his billowing parachute silks, then part emerging, arms thrown out, wheeling, tumbling, and then, thud, into the hillside. As I recall it, the hillside shook, but perhaps it didn’t; perhaps it was just an interior thud I felt. I remember Zabdi screaming ‘Dan’ and belting down the hillside towards where he lay, invisible in the deep gorse. I unharnessed myself and ran after her. There he was, stretched out on his back, laughing uncontrollably. His canopy, we reasoned later, must have caught a little air just as he landed and broken his fall. And then there was that cushion of gorse. Lucky boy.

The helicopter, a red-and-grey Sea King, had to lollop over from the mainland, nevertheless, and airlift him to Glasgow. He was in traction for six weeks, broken bones and compressed vertebrae. He hated the army, didn’t want to go back, and was never happier, they told me, than when he was lying there, immobilized, contemplating his mad descent.

A couple of years later he went missing in Dundee after a night’s drinking and was believed murdered, or drowned, until they found his body in a disused factory. He had been climbing on the roof, and it had given way.

*

In 2012, at the age of forty-two, I decided that I would travel to see the forty-two or so extant paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. A mania for Bruegel had recently gripped me, and I had been thinking about little else. And then in early May of that year I realized that all of the paintings (except one) hung in public, or publicly viewable, collections. All were reachable. I suddenly saw that there was a great Bruegel Object out there, dismembered like the body of Osiris and strewn around the museums of Europe and North America, and I set myself to reconstitute it. I drew up a spreadsheet on which I recorded where the constituent limbs and parts of this prostrate god were located, and started to plan my journeys.

The Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, while it is on my spreadsheet, has been downgraded to a section devoted to probable copies, misattributions and mislabellings. Icarus is not one of the forty-two, is not authentic Bruegel but most likely a copy. It is unsigned and undated. It is painted on canvas. Most spreadsheet Bruegels are on wood panel, and can be dendrochronologically confirmed, and those that are on canvas are not in oil but in tempera. Radiocarbon dating of the Icarus is inconclusive – there are ambiguities in the calibration curve, thick layers of oxidized varnish which mask colours and throw off precision – but the samples of the oldest canvas harvested suggest a date from the end of the sixteenth century or the beginning of the seventeenth, thirty years after Bruegel died.

In January 2011, however, this doesn’t much matter: the spreadsheet is a year off, and the Icarus is the reason I am in the Bruegel room. I am drawn by its fame. W. H. Auden wrote a poem about it. So did William Carlos Williams. Everyone has seen it, in reproduction if not in fact.

I am in Brussels waiting for a friend whose flight is delayed; we are supposed to be on our way to Bruges, but I have a few loose hours to fill. I leave my bags at the station and walk up into the centre of the city, and locate what Auden called the Musée des Beaux Arts.

Museums are safe havens. International space. No one looks twice at you in a museum. No one expects you to speak French, for example, as they might elsewhere in Brussels, in the real city. So I have a cappuccino and a croissant, and I automatically belong. I start to breathe easy.

The museum is extensive, however, and, my coffee done, I get a little lost wandering in the modern wings. It turns out there is such a thing as nineteenth-century Belgian art. And a big thing it is. But eventually I clamber up to the upper galleries where they have constructed a chronological circuit from Van der Weyden to Rembrandt and Rubens, more or less. I pick a door at hazard: it is the wrong door, and I make my progress clockwise, back through history. I freefall past Rembrandts and Van Dycks and other brown paintings, start to meet some shuddering resistance around the end of the sixteenth century, and I am still some distance away from the fifteenth-century Flems where I expect softly to touch down and walk with the strange beasts in Eden, when I happen into the corner room of Bruegels.

Here is Icarus. My idle descent through the gallery may have come to an abrupt halt, but my life has just accelerated without my realizing it. I have entered the slipstream of an as yet invisible project, a dark mass lying in the future. If I could look down on myself, see myself situated in all the meaningful relations of my life, my hair would be streaming, my cheeks juddering, in the chill jets of air.

Gravity is a weak but insistent force. Perhaps not a force at all, but a geometry. Who knows where its centres lie, or to what we are tending?

My notebooks of the time are sketchy on the subject of Bruegel. I see that I made a solitary note about the Icarus. That ploughman, I observed, was never going to be able to turn his horse and his plough at the bottom of that field.

It is not a profound observation. I have picked up on an oddity of composition – the narrow, constrained hundred, the clodhopping ploughman and his lean horse. But it leads, I see now, to others. The ploughman’s weight distribution is all wrong. The sheep, also, are ill-managed, crammed into a perilous corner of a field.

Clodhopping ploughman: Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, detail.

And the ship is wrongly rigged. Bruegel made a number of drawings of ships for a series of engravings in the early 1560s, caravels and sloops and brigantines and oceangoing three-masters, all accurately observed and set down, their complex unreadable rigging read anyway by a sharp eye. An adopted son of the great port of Antwerp, he would have had time to learn. Anyway, this Icarus ship is wrongly rigged or cack-handedly painted (the anamorphic hull would suggest the latter). Expensive delicate ship, Auden calls it. But those tiny seamen are furling all the wrong sails, leaving the lateen at the back, the absurd straining foresail caught in a squall or a hurricane – how is the ploughman’s cap not blown off, zipped up into some vortex of winds? – the billow of the sail at odds, seemingly, with the play of its cross-spar, the whole contraption flapping about chaotically. The shrouds on the foremast are wrongly positioned (or again, poorly painted). Much too much sail, in too narrow a space (although a second ship in the background is charging into port with a full spread of sail and an apparent death wish).

The ship still manages to be a conception of no little beauty, stupidly buoyant and energetic, a Dionysiac vehicle.

Three of Bruegel’s ship engravings are ornamented with scenes from classical mythology: one, of three caravels in a rising gale, has Arion riding on his dolphin, playing his harp; another, of two galleys following a three-masted ship, has the fall of Phaethon unfolding like a great pantomime in the sky; and a third, of a ship not at all unlike that in the painting (only better done, and with a full spread of sail), has both Daedalus and a tumbling Icarus overhead.

Dionysiac vehicle: Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, detail.

Bruegel rarely painted classical gods or myths. His themes were biblical, vernacular. But ocean-going ships, with their whiff of impossible distance and difference, seem to have brought it out in him. And so this ship, fabulous technology, churns up Icarus in its wake.

Experienced paragliders will skip from thermal to thermal, or dance on the uplift over a ridge. I never attained any such level of skill. I could only lumber off a hilltop like a misevolved seabird, and then hang inert beneath my canopy while it and I floated softly earthwards at an angle of, approximately, 11.5 degrees. I could take off from and land at given points, the one a straightforward geometrical projection of the other. And that was it. There was to be no soaring. Dan, or Icarus, I was not.

It was extraordinary, nonetheless. As I picture it in memory, the world stretched beneath me like a Bruegelian landscape, blue mountains on the horizon, sea skirting the world, little villages in the distance, tiny copses below, miniature cows grazing the verdant champaign. I would survey all this, rigid in my harness, listening to the calm directions of my instructor, Zabdi, whose voice was relayed over a radio strapped to my shoulder.

In the evenings Zabdi and her boyfriend Chris would share their folklore: tales of paragliders colliding, their cords twisted into some double-helix of destruction, or of gliders veering off course, into mountains, out to sea, disappearing.

Most striking of all were the tales of paragliders sucked up tens of thousands of feet into black storm clouds before plummeting to earth again, frozen and asphyxiated. These stories of cloud suck, as it is known, may be folkloric, but they are also true. Survivors tell of encountering marvels up there: furious, volatile darkness, hailstones the size of oranges, incredible forces of updraught and precipitation. They would be tossed around in regions of lurid physics, as though buffeted in the red eye of Jupiter, would black out, and then, if they lived to tell of it, would be spat back frostbitten, wild-eyed, jabbering: ancient mariners of the upper airs.

*

Icarus’s wings would not have melted, we must conclude, but frozen. He would not have splashed spreadeagled as in the pseudo-Bruegel, his feathers fluttering down after him. He would have plunged, an icy meteorite, into the green sea.

Daedalus should have known. He was the great artificer, the great engineer. He could have reasoned it out, drawn some sort of empirical conclusion. There are high mountains in Crete, mountains capped with snow in late spring, early summer. It is cold up there, in the White Mountains.

Perhaps he was blinded by the desire to escape his Cretan prison. It was Daedalus who had constructed the wooden cow for Pasiphaë so that she could couple with the white bull of heaven; Daedalus who had devised the Cretan labyrinth, modelled on the maze that led to the underworld, to house her ungodly progeny. Here was a man who understood longing and how to channel it, be that longing bestial and unsightly, or youthful and yearning. Who is to say he did not also yearn, in his way?

In another version of the pseudo-Bruegel composition, also in Brussels, in the Van Buuren Museum, Daedalus is painted in the sky, looking back down at his tumbling boy. This may be a more precise copy of the lost original. Or, more likely, the mystified copyist has spelled out the logic which Bruegel deliberately elides. Bruegel wants the shepherd to be looking up at a great blankness, because it is out of just such an unknowable blankness – his father’s manic absence – that Icarus, solitary rebel angel, falls. There are no gods or men in the sky. They are all down here, slowly ploughing the heavy clay.

*

The Landscape with the Fall of Icarus came to light and was acquired by the Musées des Beaux-Arts in 1912, just nine years after the first powered flight. A painting for a modern age, an age of exhilaration.

The chief problem faced by the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk in 1903, once they had got their Flyer miraculously, stupidly, airborne, was learning how to operate it. No one had ever flown a powered aircraft before, there was no manual; the brothers had previously built and flown gliders, but gliders rely on thermals and updraughts, on a different ethos of flying. Now they were out on their own, piloting their precarious bird of struts and wires and great-spruce wood, in ignorance of the physics which was keeping them in the air. Four short flights (of, respectively, 120 feet, 175 feet, 200 feet and 852 feet) on 17th December concluded with a tumbling nose-down landing which irreparably damaged the contraption, and it never flew again.

The concept, however, had got irrevocably aloft. Pretty soon, to fly was to live. I grew up on stories of my father’s wartime experiences in open-topped biplanes – specifically, in the Fairey Swordfish, a plane so antiquated, so creaky, so simple, it was hard to bring down since the only critical parts were the engine and the pilot. You could shoot a Swordfish full of holes, as my father told me and as the Bismarck would discover to its cost, and it would keep on coming at you. Very slowly, but with a big torpedo.

No one shot my father’s Swordfish full of holes. He was eighteen when he volunteered for the Fleet Air Arm. His call-up papers in 1943 instructed him to bring a tennis racquet to his basic training. An astigmatic left eye kept him from piloting, but he flew as a gunner-navigator over the grey North Atlantic from his base in Scotland. Later his squadron was located in Canada, then Northern Ireland, and he finished the war in Ceylon, preparing for an invasion of Singapore which never happened. He saw no action at all. But he returned with a repertoire of stories – of snakes in his shower, of feuds with Canadian lumberjacks, of leave taken in New York City – garnered by a boy of eighteen, nineteen, twenty who had spent his early manhood sitting at the whirring, clattering, piston-thumping centre of a machine of Daedalic absurdity, hunting an invisible, perhaps wholly absent, enemy, exhilarated beyond measure. It would get no better than this.

On the day I first took to the air in a paraglider I was asked by a ten-year-old boy, nephew to Anna and Zabdi, to describe the exhilaration. And I told him that it had not been exhilarating, exactly, but an exercise in control: there had been adrenalin, for sure, but it had been released in a glut of hyper-attention. I had been, above all, attentive to details of harness and rigging, to the mechanics and materials keeping me aloft. He seemed disappointed, and I did not know how to communicate to him that I was in fact excited about this.

It was a version of excitement known to Daedalus, and not Icarus. Wilbur and Orville Wright would have understood. For them on that first day the exhilaration would have been as much in the play of canvas and wood, in the creak of the struts and the stench of petrol, as in any sensations of buoyancy and velocity. Bruegel, a miniaturist by instinct, his nose close to the oils on the canvas or panel, must have known something similar, painting his absurd ship. A good painting, like a real ship, is a Daedalic object: not a pretty thing of spirit and billows for the painter who labours in front of it, but a straining, groaning, improvable, precarious livelihood.

The ship on Bruegel’s canvas, by contrast, is all fluttering impetuosity, out of control, ignorant of physics. Alive.

I like to think of my spreadsheet as a modern-day Daedalic object, a thing of glue and feathers and grids and spars designed to harness the airy desires of my midlife, or a parachute gradually rippling and filling as I block out the paintings I have seen, breaking my fall.

Daedalus means cunningly wrought, but I am not sure how cunning my spreadsheet is. It is a reductive object. Bruegel is broken down into a simple alphabetical list, with each painting further broken down into a location, a date, a medium (oil on oak panel; tempera on canvas), a series of dimensions. I have calculated the area of each painting, and the proportion of each painting considered as a fragment of a vast singular object, which I call the Bruegel Object.

Roughly 1,082 cells of information, as it stands.

Where the information tapers off – beyond, in other words, my 1,082 cells of data – there is an effective infinity of empty cells stretching beside and below. To be precise, according to Microsoft’s published data on Excel, there are 1.71798691 × 10

cells, or 17 billion, give or take.

The totality of my data clings to the edge of a great sea of unknowing which represents, I suppose, everything which is not on the spreadsheet: my ignorance of Bruegel; my ignorance of the museums in which his panels hang; my ignorance of the cities which those museums grace; and my ignorance of the impulses or affinities which have brought me to the brink of this project.

Why Bruegel?, why all of it? and why now? are questions the spreadsheet is not designed to address.

Over 17 billion cells of ignorance, then. But I have my little monastic garden of 1,082 cells, my tidy simulacrum of the cosmos.

Why this mania to quantify? Bruegel himself was not immune. In all art, there is hardly a better documenter of his own work. Almost every panel is signed and dated. Logic demands that somewhere he kept a ruled notebook in which he listed each painting that he completed, its subject, its medium and materials, its size, its destination, its cost and price and sale date, perhaps a note on problems overcome, solutions supplied.

The documentation of the Bruegel Object is secure. This is, in part, its attraction. We know what, we know where, we know when. Exclusions and reassignments, among the panels if not the drawings, are minimal, almost impossible, at least since the nineteenth century when Bruegel’s panels were routinely ascribed to Bosch.

Bruegel understood. Quantified objects are easier to handle. They are a necessary simplification. Just as mathematics does not represent some underlying truth of the cosmos, but is a simplification of it, its noise and bustle and impurity reduced to clean lines, or just as a Wright Flyer or a Fairey Swordfish is a simplification of a kestrel and thus, like mathematics, a new thing of its own, so too my spreadsheet is a manageable representation of an unimaginable complexity: the Bruegel panels, their endlessly interacting content, and their filigree intersections with the world, and with me.

The labyrinth that Daedalus invented to house the Minotaur was a way of ritualizing, hence managing, monstrous and unnameable desire. And we, too, need a way either to handle or net the creatures of imagination which rear up in the recesses of the night: black certainty of failure, nebulous inadequacy, hints of diminishing power, the ghosts of age, decay and death. And conversely, we need a way to detect whatever fleet and fugitive neutrinos of joy, or curiosity, or bliss, or ecstasy, remain to us, interstitial but real. Rarely, rarely comest thou, spirit of delight, says Shelley. But the next time thou do comest, I’ll have spread my nets. I’ll be ready.

‘Language is a perpetual orphic song,

Which rules with Daedal harmony a throng

Of thoughts and forms, which else senseless and shapeless were.’

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Prometheus Unbound, Act 4: 415–17

On that first viewing of the Icarus, if my notes and my memory are anything to go by, I missed the dead man. At the bottom of the field, in the bushes, barely visible, there is the top of the bald or balding head of a dead man. An old man. A corpse. Icarus may have been escaping, on a mad escapade; this dead man was never so fleet of foot.

Perhaps it is proverbial (there are old Dutch proverbs about dead men and ploughs). Perhaps it is cryptic, a trace element of something strange. Bruegel liked to encode his paintings. It takes a moment to find Icarus, for one thing, and once you have him you can read all of Ovid in the canvas, near-enough. So here is a fragment of information that might be unspooled.

A banal fragment. Death lies concealed in everything, we all know that. There is no project conceived, just as there is no human or indeed mammalian or vertebrate or eukaryotic child conceived or split off, that does not contain the miniature story of its own end. But containment works two ways: that which is contained is also isolated. Bruegel has trapped this little death demon in his painting, and can then, for a spell, walk away from it. Think of him now, the painting done (even if this is not his painting), a youngish, moderately famous man, walking around in the sunlight somewhere, in Antwerp or Brussels, greeting his neighbours, clearing the smell of oils and turpentine from his nostrils, catching some early spring, perhaps, watching the ships spread economical sail with their cargoes of pepper and worked cloth for Lübeck or Cadiz, his spirits buoyant on the soft airs. For a while yet.

I never dared much, nor aspired to dare. I never risked much. There is very little risk in these projects, certainly. There is only a long slow gliding descent through the museums of Europe and North America, safe in international space: hotel, station, airport, museum. I expect no exhilaration, and no escape to speak of, because for all that motion in air is a form of freedom, at some point you will land again, and one rocky shore is much like another.

The world has its systems and those systems are your freedom. You cannot escape them. Go where you will, do whatever you do, you can only step from one path to the next, one script to another. Not only is there nothing new under the sun: it has all been commoditized for your convenience. Icarus, at the dawn of the historical world, assumed that up there somewhere transformation would be available. His world is Ovidian, after all, and at any point he might sprout branches, scales, talons, tusks, the whole calculus of his trajectory might alter. His father knew otherwise. But his father also knew that although one rocky shore, one Aegean tyranny, is much like another, there are, even so, gradations. Fine gradations of freedom. We are not all equally free, and we are not all equally bound. Some scripts are better than others. Marginally.

I clamber about over my spreadsheet these days much as Dan clambered over his factory roof. With less jeopardy, perhaps, but you can always fall through where you least expect. We do not approach death as from a distance, down a perspective avenue: we walk about on top of it, constantly, our feet touching the feet of the unremembered traces of ourselves which will one day replace us.

As a young teenager I, like Dan – only not like Dan, never with that much gaiety and abandon – climbed over the roofs of disused factories. Growing up, I lived near a concrete works in partial desuetude. These were factories that in their heyday had spun concrete lamp posts for the municipalities of England. But a concrete lamp post was, by the 1980s, a costly item, durable, but expensive. Steel was the thing now. Aluminium. So the factory was running down to nothing. In a couple of years the site would be a housing estate; for now the old concrete posts were left lying around overgrown by brambles, or half-buried like amphorae in Rome.

My brother and I roamed pretty freely over the site. It had its dangers but this was the 1980s, the last days of the wild youth of the world, in this corner of it anyway, and no one cared. On one occasion I slithered merrily on my arse down a sloping roof of corrugated fibreglass, and down the ziggurat of water tanks and drainpipes and packing cases at the corner of the building which had served as our ladder up, and then turned to watch my brother follow me. He descended with ashen care.

My brother was less fearful than me, by and large, so when he finally got down I made him explain: he had watched me go, and had seen how the roof had bowed and sagged under my weight. It had looked certain to him, he said, that I would plummet through it, on to the disused workbenches and ironmongery and cement floor many metres below.

Perhaps the roof was not as fragile as all that. Perhaps I did not come close to death that day. Perhaps some of the other structures I climbed on – water towers, stacked concrete pontoons, assorted roofs – were more perilous. I did in fact fall once or twice, once from some pontoons, once from the high ceiling of a building I was abseiling into down a steel wire; but I always just got up and patted myself down. On I plodded, through an ordinary life, past this individual I briefly met called Dan, and on from that. Until that day I stood in a room of the Beaux-Arts in Brussels, looking at the Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

II Census (#ulink_5093aa27-7f15-589a-9255-a5e989ad9dc8)

Brussels (8.284%)

‘The more things happen to you the more you can’t Tell or remember even what they were.’

William Empson, ‘Let It Go’

Two days after my encounter with the Icarus, I am back in Brussels and back in the museum, this time with my friend Steve Barley, who has finally arrived from Rome. Now I know how to get the chronology right, ascending to the empyrean of Bruegel as though by a winding stair or a twisting thermal. Thus we eddy from Robert Campin to Van der Weyden to Bosch to Joachim Patinir to Herri met de Bles. And so on and up.

We enter the corner room and I make a rapid audit, reminding myself. The right side of the room as you enter is Elder Bruegel; the left side is Younger Brueghel. I am here for the Elder Bruegel. Elder Bruegel is the great Bruegel. I ignore the Younger and settle to the business of scrutinizing Bruegel.

However, there is a distracting oddity. On the west wall of the room hangs the Elder’s Census at Bethlehem, a large panel painted in 1566. But on the south wall, roughly 8½ yards distant and hanging at an angle of 90 degrees to it, is another, near-identical Census at Bethlehem, painted by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger in about 1610. It is one of at least thirteen copies the Younger made of the original, all of them faithful and well executed.

I start by trying to ignore it: it is good, but it is hack work, a cynical workshop production, a pointless replica. I am here to focus. But it happens that there is a spot, situated at the apex of a triangle the base of which is formed by the two paintings, where you can take them both in. If you had bovine eyes, the whole corner would become a giant and blurry and (to your cow mind) bewildering stereoscope.

I do not have bovine eyes or a cow mind. If I want to compare Bruegel with Brueghel, Elder with Younger, I have to swivel my head. And in reality, there is not one triangle at the apex of which you stand. Either you stand in front of the Elder and glance at the Younger, far away, or you stand in front of the Younger and look over your shoulder obliquely at the Elder. There are two triangles (at least); you move in a zone between their vertices.

And in this god-like, cow-like zone, what do you see?

In both cases, a snowbound village scene dominated by children playing and scuffling in the snow and their elders scratching out a living with their fardels and pigs’ blood and snowed-under carts, their small and wintry concerns. Around the inn in the left foreground a crowd gathers, submitting their names to the census; others straggle in across the frozen river, and across the frozen pond. Mary and Joseph are unobtrusively there: Mary, riding on an ass, nine-tenths concealed in her blue robe; Joseph likewise hidden behind a large hat but waggling a two-handed saw over his shoulder.

They are both as yet unnumbered.

For Pieter Bruegel the Elder, there was only ever one Census. It was a singular object. Unlike his son, he did not run an extensive workshop, did not bang out copies. He made few paintings, each one in his own hand.

When he died in 1569 at the age of about forty-two, his eldest son was four or five years old, his youngest, Jan, just one. In terms of art history, there is no genealogical connection between father and sons, merely a tectonic overlap. Pieter the Younger inherited a series of world-famous images (if by world you are content to understand Northern and Habsburg Europe), probably in the form of what are known as cartoons, drawings used to transfer an image to a panel. His entire career down to his death in 1636 was grounded on these images, whether he was making direct copies or spinning genre pieces from them.

He most likely saw little of his father’s original work, much of it already carted away to the great imperial collections – hence the small differences which creep in, the errors in replication, the drift.

As with his name. Pieter the Elder had started out plain Pieter Brueghel of Breda, signing his name with a calligraphic flourish on the drawings he produced as a young man. When he started painting in oils towards the end of the 1550s, he dropped the ‘h’ and began signing his name Bruegel in chiselled capitals, frequently with a ligature between the v (the Roman u) and the e, usually with the date (and after 1562 the date is generally written in Roman rather than Arabic numerals, with two or three exceptions), never with a P. or Peter – in the couple of cases where a P. was placed in front of bruegel, the paintings later turned out to be rather careless modern forgeries. ‘Brueghel’ was a bit burgher, perhaps, a bit stomping peasant; ‘BRUEGEL’ is cleaner, more Roman, befitting a Stoic observer of stomping peasants.

His sons for some reason restored the ‘h’ to the family name. Brueghel. Early in his career, Pieter the Younger aped his father’s Latinizing capitals, but reverted to small-case letters for most of his copies, and he never creates a ligature between the v and the e, although he does occasionally between the h and the e. Until 1616, he always appended his initial, ‘P-Brueghel’. After 1616, he altered the spelling of his surname once again, reversing the v (or u) and e, ‘P-Breughel’. In these ways, the Younger distinguished himself not only from his father, but from his younger brother Jan, who always signed simply ‘Brueghel’. Subsequent generations, notably Jan Brueghel’s son, Jan Breughel the Younger, retained the order of e and the u: ‘Breughel’.

Father and sons and grandsons and great-grandsons, taken together, make a blurry bruegel/Brueghel/Breughel object.

There was also a daughter, Maria Bruegel. Or Brueghel? We are not even sure about Maria: some have it as Marie. We know nothing about her. Older than her brothers, most likely, and certainly older than Jan, who was born only months before his father died. Probability suggests death in infancy. Her brother Pieter the Younger would have seven children, only one of whom would survive to adulthood.

Some children barely draw breath. My mother recollects a brother, Harry, who died before morning on the night he was born. She says she heard him crying that single night in the 1930s, in the solitary room in the west of Ireland that would constitute his universe. Crying perhaps under the baptismal hand. Harry, in the eye of God. And then he was gone.

So too Maria. Gone. The merest flicker of data in the endless ticker-taping lists of the quick and the dead.

I move between the invisible apices of my triangles, comparing Bruegel with Brueghel. It is a midweek morning in early January, raining outside the museum and largely empty inside. This is where my as yet undefined project has brought me, dead-reckoning in a room of old paintings.

I am forty-two, around the age at which the Elder died. Forty-two is the number of Bruegels on the spreadsheet. My own father has died, a year or two previously, aged eighty-four. When I was born he was forty-four. I was the second son. There are two years between my brother and me. I have also recently become a father myself, to two sons, between whom there are two years. Pieter Bruegel had two sons: the Younger, and Jan the Elder, between whom there were four years.

And so on. You do not really explain an intersection by following up or down any of its convergent, or for that matter divergent, paths. It is sufficient to note that my midlife is characterized by the interaction of multiple convergent (divergent?) vectors: my dead father, my brother, my small sons, myself, and the Bruegels. Many similar triangles.

*

The census is an unusual subject. Bruegel has painted one of the culminating moments of bureaucratic life. Bureaucracy is the science of docketing the routine comings and goings of existence – births and deaths, taxes paid and taxes owing; it is a rolling programme of work, one without end.

A census, however, is a one-off. It is a flourish of the bureaucrat’s art. You do not merely keep the ball of a census rolling: it wants planning and execution. It is, properly speaking, a project, a projection of bureaucracy. And it has an end: a Domesday Book of taxable, pressable souls.

From a distance – to the administrator or historian – a census is an exercise in control and power, not always pleasant, but always impressive in its way, like a datastream ziggurat or Hoover Dam. Seen close to, however, it pixilates into a sequence of inexact iterations. The bureaucratic ground troops do not mechanically fill in blanks. They have to keep a weather eye cocked on the confusion of crowds, have to sort quickly, roughly (there are only so many categories) but accurately. They have to fix a point in time where there are no points in time.

Bruegel’s Census at Bethlehem therefore depicts a world in transformation. The census is drawn through the village, through that mess of humanity at the inn door, like the carding of wool. The stream of individuals passes back and forth over the frozen river: people come in nebulous and free to have their names written down in a book, their existence validated in ink; they go out docketed and numbered, but also informed, no longer unlicked stray lumps of humanity but named individuals, with a location and an occupation and a marital status, enjoying a spark of existence beyond their own clay.

*

How, then, to number the paintings which hang in this room? How to enter them on the spreadsheet?

On an adjacent wall to the Census in Brussels is the Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, a small sepia painting. Little figures skate on the frozen river, or huddle over their game of curling. On the bank, under a tree, a trap is set for birds: a heavy assembly of planks (in construction, not unlike the panel it is painted on) is propped up on a stick, a lure of crumbs beneath it; from the stick, there is the merest trace of a taut string leading into a house on the left of the panel. Snatch the stick from under the planks and you might catch a bird or two, just as the painter of panels, ever watchful, might catch and trap a soul, or a village of souls. Snatch the ice from under those skating children, and you might drag one or two down. The birder, the painter, the Devil are always watching, always waiting.

Always watching, always waiting: Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, detail.

The skaters and the birds are linked by two stylized black birds in the foreground. They are the same size in real terms as the skaters, the same tonality also; they could be mistaken at first glance for skaters.

Birds and skating villagers live a similar existence: birds have wings and skaters ease along at great speed; both are in danger, both seem at liberty. The birds could fly away, live in the woods, while the villagers could slide around that bend in the river and be gone in minutes, never to return. But the ice will melt and the villagers will remain. Winter birds, too, are territorial. All are rooted here.

Including Bruegel. Bruegel might have skated around that bend and away, to Antwerp, to Royal Brussels, to Rome and Naples and Calabria. But he came back. According to Karel van Mander, who included, in his 1604 Schilder-boeck, or Book on Painting, brief lives of the great Netherlandish painters, Bruegel frequently visited the villages around Antwerp and Brussels in disguise, infiltrating festival and kermis (a kermis – from ‘kirk mis’ or ‘church mass’ – being the annual festival held in honour of the village church’s named saint), observing but unobserved.

His panels are littered with figures standing on the edge of crowds, watching. Some are well-heeled, clearly not village folk, returned from the city for family weddings, to partake again, briefly, of the drunken, cavorting rhythms of village life.

One way or another, in paint as in life, this was Bruegel’s world.

*

Bruegel’s Bird Trap was a popular subject. There are at least 125 known and documented copies.

But what is a copy? If I were to take out paint and easel now, and run up some version of my own, would that constitute a copy? Number 126. Mark it down. At what point does the painterly spore of Bruegel peter out to blank snow? When can we say that the code has replicated itself into muddy, unrecognizable progeny, into mass reproduction?

On the wall opposite the Census, there is a large canvas, an Adoration of the Magi. This is not generally attributed to Bruegel, but may be after a lost composition, like the Icarus. It is in watercolour, an unusual medium for Bruegel. There is a tempera Blind Leading the Blind in Naples, and a Misanthrope; there is The Wine of St Martin’s Day in Madrid; otherwise it is all oil, all panel.

The canvas is badly damaged. Who knows how many panels have been lost over the years, painted over, chucked in skips, on bonfires. Van Mander mentions two versions of Christ Carrying the Cross (one remains); a Temptation of Christ, with Christ looking down over a wide landscape; a peasant wedding, in watercolour, with peasants giving presents to the bride; and one other watercolour in the hands of the same collector, undescribed. We know of others, gone missing. A crucifixion. A miniature Tower of Babel. The first in the sequence of The Months (April/May).

Whatever Bruegel saw when he contemplated his own Bruegel Object is lost to us, a ghost configuration. Whatever might be vouchsafed to posterity from a life lived – in Bruegel’s case, a lot; in my case, as in most cases, nothing – is only very approximately indexed to that life. I have very little interest in biography. It is not Bruegel’s completeness that I am interested in but my own. But I am conscious that the dead panels stand whispering beyond my spreadsheeted ring of firelight, and no amount of conjuring will induce them to step forward. It is too late.

When my father died in 2009, he was eighty-four years old. A double-Bruegel. The parallelisms proliferate. I consciously peg each year in my life, for example, to a year in my father’s, according to the age of our children: so in 2017, when my Bruegel project finished, my children were nine and eleven; my brother and I were nine and eleven in 1978.

Robert Henry Ferris in 1978 was making his last throw of the dice, leaving GEC, the General Electric Company – the huge conglomerate where he had worked, barring an interruption for war service, for nearly forty years – for a much smaller company, where he might just hope to be a bit of a big fish. That didn’t really work out either. He was fifty-three, and his heart wasn’t in it. He told me after he retired that, in all the years of his working life, he had never been early for work once. He had a lively mind and a fairly dull job. He didn’t travel much. He just sort of stopped.

One evening, at around that time, he sat down and wrote in an enormous year diary one line: It is said that in every life there is one story. This is mine.

One line a night was enough, he said. If you wrote one line a night you would soon have a great big book. I was nine, and I was impressed. But it was too late. He liked his sedentary whisky too much, could never find the energy to add anything to that one line. He could certainly write, but he lacked technique and discipline. And there it stayed on a shelf, the weighty volume with the solitary line and several hundred enormous blank pages, like the blank cells of my spreadsheet. A metaphor, and a bit of a shitty one at that. From time to time my brother or I would take down the volume and study it, either to shame him publicly (and he would laugh along jovially enough at his own foolishness) or to teeter privately on the brink of some immense intuition: not only was our father’s life unfulfilled, but all life was most likely unfulfillable. ‘It is this deep blankness is the real thing strange,’ writes the poet William Empson. And there it was, this deep blankness, sitting on a shelf in our living room.

My father went on in due course to his deeper blankness, his long home. But when he was in hospital dying, my brother was searching the census records of our paternal family. My father was always reticent with family history. He had been born in 1925 in Camden, had grown up there and on Portpool Lane off the Gray’s Inn Road, and later in Lee Green. There were some disconnected anecdotes – a story about a broken radio, about a Jewish funeral, about an aunt who sprinkled sugar on his buttered bread – not much else.

His mother had died of heart disease during the war when he was a very young man. He rarely spoke about her, but on one memorable evening over whisky towards the end of his life he found he could not recall her name. The grip of my father’s memory was utterly secure until his last day. But he could not remember his mother’s name.

Later, he dredged it up from somewhere. Anne. My brother uncovered more detail, and relayed it to my father in hospital. She was recorded as Annie on the census of 1911, at nine years old the youngest of five sisters growing up on what is now Tavistock Street, just off Drury Lane. She had been born around the corner on Stanhope Street, coloured black on Charles Booth’s poverty map of the late 1880s to designate ‘Lowest Class. Vicious, semi-criminal’. Stanhope Street along with the whole rookery around Clare Market was bulldozed soon after to make way for the arterial Kingsway. No. 1 Kingsway would become, until 1963, the head office of GEC, my father’s first place of work. In 1940, during the Blitz, he would firewatch from its roof, and could have lobbed a cricket ball through the vanished window of his mother’s slum birthplace.

Years later my grandfather told my mother that his wife – Annie – had had a temper on her. Choleric. Hot blood. Hasty heart. The death of her. She died, as I say, of heart disease in 1944, aged forty-two. Years of Bruegel. My father travelled down from Scotland where he was based with Coastal Command, whether in the nick of time, to watch by her bedside as the candles flickered out, or too late, I do not know. He was an only child. He and his father were thrust together to deal with this small loss in a world undergoing incalculable loss.

My father was not obviously close to his father. Pop, as he called him, lived with us until he died when I was eight. My mother says my father rarely addressed him, never had a conversation with him. Who knows if it was trauma, or sadness, or indifference which sundered or secretly united them.

When Pop died, only my father and my mother attended his funeral. My father took Pop’s remaining possessions – a few books, razor, alarm clock, wallet and clothes – and put them in a bin bag and slung them on the municipal dump. There was to be no gravestone, no memorial rose, no bench in a park, nothing to visit.

But within the year my father sat down at the empty diary and confronted its alarming blankness.

In truth, all this biographical detail was probably less use to my father than his anecdotes, and in any case it was difficult to gauge his response – his circuit of interest had contracted to the point where all that concerned him were the minutiae of the routines that were eking out his life.

But for my brother and me it assuaged the sense that here was a disconnected dot, about whom we knew not very much, going into the darkness. There was a chain. He was linked, and so were we. It was written in the census.

People may be numberless, but they are not identical; you are defined both by your similarity to and by your discrepancy from them. So, spot the difference.

The Younger’s panel is fractionally larger – he may have been working to Antwerp rather than Brussels feet. Whatever the reason, the result is that figure groups, for which there would have been separate cartoons, are pulled this way and that within certain tolerances, marginal plays.

No two figures are dressed alike, fabrics change colour, there are odd reversals. The woman in the lower right, for example, wears a red-green combination of overskirt and underskirt inverted in the Brueghel copy. There are microscopical differences between faces, individual posture. The Younger had his own way with trees, bushy rather than twiggy.

Criss-cross tracks, paths, desire lines: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Younger (left) and Elder (right).

And then, more slowly, I see that the Younger favours tracks. From the bottom right, where Mary has entered on her donkey or ass, to the top left across the frozen river; and again, from the wheels of the foreground frozen carts, there are criss-cross tracks, paths, desire lines, animating the space. This is a frozen world, but there is evidence of networks, organized around an axis.

The Elder’s foreground carts, by contrast, are going nowhere. There are no paths, just yellowish ice wallows. He has painted a village of spindly cartwheels, a spindly ladder against a spindly barn, spindly trees. And he has painted a world of endlessly repeated circles – the wreath, the barrels, and especially the cartwheels, thirty-one of them, including one a fraction below dead centre, hitched to no wagon and orthogonal to the viewer, as though it were not a material object at all, but a diagram of the interlocking cycles of village life and the seasons, of the great wheels of history and Christian redemption.

Hitched to no wagon: The Census at Bethlehem, detail.

And then finally I recognize what sets the two paintings apart: the Younger, perhaps seduced by those few inches in hand, has raised the branches of the largest foreground tree a fraction to reveal what in the Elder there is none of – a vanishing point, or what the Italians call a punto di fuga, a fugitive point, a point of escape. The Younger’s brown frozen river winds out of the panel. His father’s, by contrast, is entangled in the branches, perhaps coils around the back of the village, a labyrinthine waterway.

The only thing vanishing is that peculiar sun. The old world is ebbing to its conclusion.

The Younger – wittingly? unwittingly? – has made this dead cosmic circuitry bearable, transient. Along those paths and on that frozen river our eye is made to criss-cross, not circle, and finally escape the painting. And he has done all this in direct contravention of the central thought process of the original – that these circles go nowhere for a reason.

A vanishing point: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Elder (top) and Younger (bottom)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger may not have been a painter at all. He was unarguably an eminent man in the Antwerp art world – there is a portrait etching of him by Anthony van Dyck, in which, as it happens, he projects the sort of patient melancholy common to men with drooping noses and straggling moustaches. But he may only have been the inheritor of the cartoons and the general manager of a workshop which employed anonymous hands to complete the copies. It is possible that he had no artistic personality, nothing but a signature and a locked chest of cartoons which he carefully opened and closed as required, a bureaucrat among artists, ghosting through the system, the painted artefacts. The notion that somewhere in that swirl of hands and methods and corporate production was the memory of a five-year-old boy transfixed by the death of his father is nothing more than an absurd projection of my own.

But this is why I am here. I did not come into this room in Brussels to discover a truth, but to impose one. To make something of all this. This is one way in which we react to the accumulation of life. We make spreadsheets, trace genealogies, embark on projects, write essays. We pore over the data in search of patterns. All this must and will be made to mean something.

I stand in the corner room of the museum, then, observing small differences. Discriminating.

And there is in fact one final difference – a figure, present in the Elder’s panel but absent in all the Younger’s copies, suggesting a late emendation on the father’s part, a final gratuitous flourish of his art: it is the youth pulling on his skates, below the tiny child who cannot yet summon the courage to go out on the ice.

Life is treacherous, says the figure, but we have resources. We have skates. We can make of this treacherous ice our element. Sooner or later, we all pull on our skates and go out on the ice – as the father might have remarked to the son, had he had time.

We have resources: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Elder (left) and Younger (right).

This whole village, in fact, suddenly seems to be poised by the ice, spilling uncertainly but inevitably over its edges. Just to the right of the large tree by the water a father stands hands in pockets and watches his two small children testing the curious element.

The skater’s absence from all copies (bar one – a recently discovered panel has the skater, suggesting a late, rectifying glimpse of the original, or a post-mortem addition) implies that it was the father who was diverging, making changes on the hoof, inserting figures at the last minute, blotting out the vanishing point in a moment of inspiration, and the son who adhered more faithfully to the earlier version, the cartoon or, more likely, sheaf of cartoons. There is, after all, a sensibility in copying well, an alertness to detail. One of the Younger’s guiding virtues, you could say, was fidelity. Copying is meditative and respectful work, itself a way of thinking.

If he was occasionally caught out by the odd detail it hardly matters. At some point the fractional differences collapse into the far greater mass of similarities. The census is not a record of our individuality in the end, but of our solidarity. Thus there is not a source of pictorial DNA – the Elder – and a series of ever-degrading replications. Rather there are versions of versions all orbiting a hypothetical centre of mass (the cartoon), just as the small children of the village eccentrically orbit the centres of mass set up between them and their parents, and their parents in turn orbit the invisible barycentre which lies between them and their ancestors, and which we commonly call the community. Each of us, present or absent, exerts our own small constant gravitational tug, variable in time, hard to calculate, take account of; but there, nevertheless, in the mass of data points, and the geometry which comprehends it.

III Fire (#ulink_925f3521-243e-5020-9f92-577bd6bf3cb9)

Antwerp and Rotterdam (6.316%)

‘The air still moves, and by its moving cleareth, The fire up ascends, and planets feedeth.’

Fulke Greville, Caelica

Months pass, and I wage a phoney war against the looming Bruegel Object, pick off a panel here or there, drag myself like a forlorn expedition over the still-featureless map of all Bruegel. Finding landmarks.

The cities I visit are cities named in a dream of Europe. Rotterdam. Antwerp. Places you might struggle to put a pin in, but which underlie your notion of European. Once I have visited them, I hardly know that I have been there: waystages on a cosmic map.

Rotterdam, for instance. Rotterdam is a station, roadworks, new buildings, a long straight walk to the museum along a windy street. It is a museum built in the 1970s, an empty café with coloured chairs.

That is Rotterdam. Have I been there? Barely.

*

I am in Rotterdam with a friend, a painter called Anna Keen. Sister of Zabdi, my paragliding instructor. In Rome in the 1990s we were a couple. We lived behind the Colosseum on top of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s cavernous, mouldy, buried golden palace, with its revolving dining room and its obscene frescos.

Now Anna lives in Amsterdam, in a shed near the water, and I am paying a visit. In a couple of days my brother will join us.

The shed is part of a complex of work units – next door, for example, is a builder of speedboats, or racing yachts, I do not remember which. I only remember looking down the length of streamlined hulls, bright paintwork, varnish. Rigging? I don’t recall.

Anna’s shed is also her home and a source of income – she sublets parts of it as studio and living space to art students. Her brother Nick, a carpenter, has come over for a few days and built partition walls. Anna lives upstairs in the low-ceilinged loft that runs the length of the shed. You have to stoop as you walk along it. You ascend by a ladder between two antique electrostatic speakers into her wonky space of two thousand books and paint-stained electronics – laptop, router, amplifier, speakers – and naked plasterboard. A padded silver pipe runs up through the floor. Plastic flapping windows give on to the main space, where Anna has her own wooden boat propped up and her immense easel, and endless red-and-white packets of a line of budget food called Euro Shopper which for some reason she cannot stop buying, and presumably consuming, and wants to paint. On each packet is a schematic drawing indicating the packet’s contents – a red-and-white cow (milk), a red-and-white peanut (peanut butter), a red-and-white gravy boat (brown sauce), a red-and-white whisk (whipping cream, UHT). They are everywhere. A ready-made Warholian homogenization of all food and all household goods, in this most dehomogenized of spaces.

Anna has installed a large wood-burning stove in her kitchen, and it directs heat around the shed complex along silver-insulated pipes. It is February, the stove is working full time, and everything you touch is either scalding hot or icy. The inhabitants of the shed (three, four art students, Anna, Anna’s brother, Anna’s brother’s girlfriend, my brother, and me) shuffle around wrapped in scarfs and old jumpers, clutching mugs of tea, seeing how close we can get to the fiery stove without singeing our flesh. Whatever the stove radiates seems to dissipate within an inch or two of its cast iron: the zone of warmth is perilous and narrow.

I persuade Anna to come to Rotterdam and look at the Bruegel.

Rotterdam. To recapitulate: a station, a street, a museum, the wind, and The Tower of Babel.

Museums are for the most part horizontal structures. I do not know many properly vertical museums. But the Rotterdam museum contains one of the great essays in verticality. It is the smaller of Bruegel’s two Babel panels – the other hangs in Vienna – but the larger of the two towers. The compositions are similar. The Vienna tower is built around a cankerous rock and in the foreground, receiving obeisance from his stonemasons, there is a king (Flavius Josephus ascribed the building of the tower to Nimrod); the ships are much larger than those in the Rotterdam panel, the horizon subtly higher; in Rotterdam we are higher, therefore, and see further.

Essays in verticality: The Tower of Babel – Vienna (top) and Rotterdam (bottom).

The rocky outcrop jutting from the Vienna tower is not the foundation but the metamorphosis of the built structure – there can have been no pre-existing plugs of rock on this flat plain. The weight of the tower has compressed and transformed its materials. It is subsiding on the shore side into marshy land.

The Rotterdam panel, on the other hand, is a pure geometry. Lessons have been learned. The only transmutation of materials here is into upthrusting energies. No wonder the builders’ jealous god got worried.

Both towers not only dominate their respective landscapes: they are the landscape. Everything of interest on the nondescript plains is subsumed into the towers, just as a great city – Antwerp, for instance, or Brussels – will suck economic energy from the land and the seas which surround it.

Bruegel was an inheritor of the Netherlandish tradition of the World Landscape – painters such as Herri met de Bles and Joachim Patinir had for a generation before Bruegel produced increasingly broad and schematic landscapes where great rivers and mountains and plunging precipitate views and cliffs and oceans beyond stood as much for a representation of the cosmos as for anything you might see in nature.

Landscape started to emerge from the background, took a sociological, topological, cartographical, thematic turn. It became not just a reflection of cosmic order but the whole theatre of man and his salvation, the teatrum mundi, the theatre of the world.

Bruegel introduced a note of difference, however. A naturalism. Simon Schama observes that, relative to the work of Patinir and met de Bles, the landscapes of the early seventeenth century had been ‘deprogrammed’. They had ceased to be grand schematics of the cosmos, or moral topographies, and were now ‘just’ trees, woods, streams. And this process of deprogramming begins with Bruegel.

In around 1552, Bruegel, a young painter newly emerged from his apprenticeship, travelled to Italy, most likely with fellow painter Maarten de Vos and the sculptor Jacob Jonghelinck. He travelled down through France (we know of a lost gouache View of Lyon); proceeded over the Alps to Rome, where he stayed for two years; and then pressed on more briefly to Naples, Reggio Calabria, and in all likelihood Sicily.

Such a trip was not unusual for ambitious Northern painters, who were expected to educate themselves in the ruins of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. Bruegel most likely did precisely that but, perhaps at the instigation of the Antwerp printer Hieronymus Cock, he also documented his trip with reams of topological views: the Bay of Naples, Reggio Calabria, the Strait of Messina, Rome, the Alps. And on his return, it was with these views and a set of generic engravings – the so-called Large Landscapes, incorporating elements of his Alpine journey – that the young Bruegel established his reputation. ‘On his travels,’ wrote Van Mander, ‘he drew many views from life so that it is said that when he was in the Alps he swallowed all those mountains and rocks which, upon returning home, he spat out again on to canvases and panels.’

Bruegel had a precise eye. His work has been described as ‘ethnographic’, so fastidious is it with details of peasant life, and in the same way his World Landscapes never neglect shape of leaf or jizz of flying bird – a generic silhouette in the sky is, on closer inspection, a magpie or a cormorant; a foreground plant is not just an iris but an Iris germanica. The natural world adorns the schematic landscape, or the schematic landscape polarizes the naturalistic detail, in a way that Ruisdael or Hobbema, or Constable or Monet, would have understood. The real keeps impinging on the meaningfully arranged. And vice versa. We are caught in suspension between what God ordains and what Bruegel experiences. And the two are not necessarily aligned.

On his Italian journey, Bruegel must have seen and drawn, and, to judge from his versions of Babel, slightly obsessed over, the Colosseum. Both the Rotterdam tower and the Vienna tower are colosseums telescoping upward to infinity. Both are set on the plain. There are some distant hills in the Vienna panel, none in the Rotterdam panel. To repeat, both towers are the landscape, translations of the cosmic landscape into urban form. These are stone cities pulled up from the earth in the manner of origami trees, birthing strange rocks, over-topping the clouds, bending the frame of the earth. Symbolic, but also detailed. Naturalistic.

The Rotterdam tower – the later of the two, by some five years – is both an architectural and a chromatic fantasy.

At the top, the endless intricacy of its internal form is revealed. The Gothic variation and repetition of its windows and arches makes of them not merely entrances but a sort of hyperbolic internal structure, as though the builders had lighted on some multidimensional or geodesic solution to the incalculable stone weight of the structure that had defeated them in the Vienna panel; this fresh tower will go up and up supporting its own weight on tensile Gothic arches and windows.

Pollen of the mason’s art: The Tower of Babel (Rotterdam), detail.

There is no king here, no central intelligence and motive force. The builders of this monstrous beautiful thing scurry over its exterior and interior like the manifestation of an algorithm, working their twig-like cranes and filigree hoists, leaving deposits on the pinkish sandstone of white and red from where the marble dust and brick dust are shaken like chalks, pollen of the mason’s art.

*

At the base of both towers are culverts or sally ports where a boat might drift inside, sail right into the heart of the endlessly ramifying structure. You might load your ship with barrels of gunpowder and seek out the keystone, the arch or spar whose destruction would bring the whole of this tyranny crashing down. Every project has its point of weakness. A niggle, a suspicion, a discord. If there were not, there would be no need for a project. Straight life would suffice. The project is an attempt to reconcile irreconcilables, to square the circle. Something must be fudged in the process.

Freedoms, for instance. Manfred Sellink, cataloguer of Bruegel, finds the Rotterdam tower more menacing than the Vienna; the equally eminent Larry Silver regards it as an index of the productive capability of a free people (the Netherlanders) contrasted with the crooked construction of a subjugated slave race (the Spanish).

I do not know whether the tower is menacing or not. It is certainly fascinating. Did Bruegel have the ways of tyranny on his mind? It seems obvious to us – his Netherlands were part of the Habsburg Empire, effectively under Spanish rule. In his lifetime its people would start to resist, and, just months before his death, rebel.

Why else, after all, would you paint the Tower of Babel again and again (and again – there is documentary evidence of a third version from his Rome years, on ivory, now lost)? Who knows? The Colosseum must have made its impression on a young visual mind, its self-similarity, its modularity, its controlled barbarity. The Tower of Babel in the biblical sources represents hubris and fragmentation, but it also stands on the last edge of a unified world, one sufficiently sure of itself to embark on a grandiose building project. Bruegel’s contemporary and friend in Antwerp, the printer Christophe Plantin, would in the last year of Bruegel’s life begin setting his great bible, the Antwerp Polyglot, in five languages, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Aramaic and Syriac, with dictionaries and grammars, itself a monument to clarity in fragmentation – as though bringing all these languages together in one huge volume under a sufficient weight of scholarship might metamorphose the sedimentation of scripture into a solid impregnable rock.

Tower, Empire, Bible: grown sufficiently tall, sufficiently all-encompassing, sufficiently all-explaining, they become like the earth itself: inescapable, eternal, boundless.

What lies under the eye of God and eternity? Great landscapes and towers, and tiny people.

On the fourth spiral of the Rotterdam tower, very close to the mid-point of the panel, you can make out, if you crane in close, very close, and stare hard (with your god-like eye), a tiny procession with, at its centre, a red baldachin. Under this, it has been suggested, a pope is making his ascent of the tower. Roman colosseum, pope at Rome, tyrannical Spanish inquisitors. Draw your conclusions.

A society on the brink of revolution, or lying under the yoke of tyranny, grows cryptic. Things are necessarily hidden. We have no way of knowing where Bruegel’s sympathies lay. All we know is that his compositional instinct veered towards crypsis: hide the subject.

*

I am beginning to get a feel for the Bruegel map. An outsider’s feel. The feel of an autodidact.

The Bruegel tower in Rotterdam is a pin. I can wind a string around it, stretch it over to Vienna and wind it again.

I still do not know, in Rotterdam, that I will see them all, that this is my project, so the map of all Bruegel remains at this point mostly featureless, speculative, a land of hearsay. I know that there are plenty in Vienna; others are in Madrid, Paris, London, New York. I have looked at the Bruegel page on Wikipedia, and have promised myself a book on Bruegel. But which one? Another unknown landscape stretches out before me, of Bruegel scholarship.

It will be by no means my first project. I have spent half a lifetime working up projects: Robinson Crusoe canoes, antique flying machines that never fly. All useless devices, but each informed by the same creative spurt, each one a new, futile form of flight, of escape. Just like that tower on the plain, on the edge of the sea, fugitive city making for the skies.

In the early 1950s my father and a friend of his called Bill (surname unrecorded) booked themselves on to a coach tour of the Low Countries: Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam. But the authority of their guide, the tyranny of the schedule, the sluggishness of the coach immediately chafed, and they abandoned the tour and took themselves off on a mad jaunt of their own devising: church, bar, red-light district. My father still talked of it half a century later (although he glossed over the red-light districts; I learnt about these after he died, from a notebook he kept). The trip was, for the rest of his life, a reminder of the exultations to be had from torching the programme and careening off the map.

I have known similar moments of minor exultation. For example, I have walked out of more jobs than most people have had jobs.

Things change, one moment to the next. One moment you are employed, seemingly reliable, a plodder; the next you are enjoying some sort of giddy breakdown.

The last time I walked out of a job, my first son was not yet one year old. This is not responsible behaviour. After a few months, I ended up on my feet, again, just, but this had to be the last time. I have tried revolution. The knucklebones are just knucklebones, in the end, and the patterns are always familiar. Perhaps I did not burn deep enough, early enough; perhaps I should also have salted the black fields of my existence. But the suspicion remains: there might be other ways to model your life.

On our return from Amsterdam, my brother and I run into difficulties. We have chosen to take the train so that we can stop for a few hours in the Brussels museum and refresh ourselves with Bruegel, but the train lines are down at some key junction. We wait for an hour on a cold platform with Styrofoam coffees, then take a train to the next stop down the line – The Hague. We have to get off. No one knows what is happening. We are told to get on a certain train, which takes us to the next stop – Rotterdam. And we have to get off again. Thus it continues, all day: we work our way from Amsterdam to Brussels one stop at a time.

Bruegel did not live in a world of timetables. Deadlines? Highly doubtful, although I can at least imagine a time-is-money Hieronymus Cock goading on his young artist, clapping his hands together in a show of energy, dividing up the labour, watching his costs. I can also imagine his young artist, possessed of a peasant’s appreciation of his own value, resisting, taking his time, not so much doing as getting around to.

We live otherwise. We must get back to England today. At each stop, when it seems we have finally run out of luck, my brother and I furiously google alternative planes, buses, but then before we can act a train turns up and there is a frantic cramming to get aboard. Dordrecht. Roosendaal. Antwerp. It grows late. Dark. We miss our connection in Brussels. And we miss the Bruegels. In the thick press of quantified time, all spears of purpose are, sooner or later, shivered.

I have a superstition about travel: it has a prevailing wind. If you make a there-and-back-again journey, you will be swept along easily in one direction, and have to beat back painfully in the other. But this is more than an ordinary squall or countervailing trades: it is clear to me now that we have offended the Netherland Poseidon. We have treated his realm as one entity, a large flat land with a common language, dotted with emblematic Bruegels. But it is not. It is fractured: by language, by politics, by religion, by river and sea, by the repelling magnetic North–South grain. And so we are smashed this way and that.

*

In 1566, called by contemporaries the Wonderyear, the Netherlands, North and South, were host to a spate of image-breaking. Churches were sacked, statues and paintings smashed, pulled down and burned, and the consecrated host, which renegade hedge-preachers called ‘the baked god’, was generally humiliated.

Some of the hedge-preachers – so-called because they preached outside the town and beyond the reach of civic jurisdictions – were Calvinist ministers who had returned after the suspension of the Inquisition in the Netherlands by the regent Margaret of Parma in April of that year; others were disgruntled ex-monks jumping the walls. They preached reform, and they preached iconoclasm, and in August, starting on the 10th in the town of Steenvoorde in the industrialized Westerkwartier of Flanders, some made good on their preaching by leading a mob to the chapel and sacking its images.

The violence spread, reaching Ypres on the 15th, Antwerp on the 20th, Ghent on the 22nd, Tournai on the 23rd and Valenciennes on the 24th. In Antwerp, the Feast of the Assumption on the 15th passed off peacefully with a parade of a statue of the Virgin, but on the 19th a group of youths entered the church where it was housed and mocked it. They were dispersed, but returned on the 20th accompanied by half the town. After some psalm singing, the church was sacked, with the rioters parading in the vestments, drinking the holy wine, and bathing their feet in the holy oil. In Ghent, the image-breaking extended to mutilation, mock-torture and mock-execution of statues and paintings. The great Van Eyck altarpiece Het Lam Gods was only saved by being hastily disassembled and concealed in a locked tower of the church under guard, while the iconoclasts went about their business below.

For the most part, and in contrast to the iconoclasms elsewhere in Europe (France, Switzerland, England), the procedure was genial, carnivalesque and often very orderly, a holiday from incense and mummery. Through August and September, the hedge-preachers moved in to some of the now cleansed churches, cities were barricaded against the often complicit local authorities, independence declared. But the Spanish clamped down. Early in 1567 the Duke of Alba arrived from over the Alps with armies and siege trains, and the uncoordinated fires of rebellions were extinguished one by one.

By 1566, Bruegel had left Antwerp for Brussels, a distance of 30 miles, exchanging the commercial capital of the Spanish Netherlands for the political.

His birthplace is usually given as Breda (c.1525) or environs, but he seems to have grown to artistic maturity in Antwerp. It is supposed that he settled there after his return from Italy in 1554, although there is no documentary evidence. However, his early artistic endeavours were all drawings for engravings for Antwerp print houses (notably, the Sign of the Four Winds, run by Hieronymus Cock). His first surviving painting, which hangs in San Diego, dates from 1557, but only a handful of paintings were made before 1561. It was from 1562 that painting really took over. By 1563 he had settled in Brussels and married Mayken Coecke, daughter of his master, Pieter Coecke van Aelst, and the miniaturist Mayken Verhulst; Van Mander has Mayken Verhulst persuading Bruegel to settle in Antwerp in order to distance himself from a previous amour, a serving girl he wanted to marry but found to be a serial liar. In Brussels, Bruegel ran a small workshop (where, according to Van Mander, he delighted in spooking his assistants and pupils with ghostly noises), although there is little if any evidence of workshop hands in his painting (some have taken the sky in the Census, for example, that lurid sun and the flattened treetop through which it shines, to be by assistants). From 1562 Bruegel painted an average of five (surviving) panels or canvases per year, until 1568, the year before he died, implying that he must have died early in 1569.

And so there he is, Bruegel the Elder: a creature of paint and prints, of signatures and hearsay. Nothing more now.

The documentary evidence for my father’s life is similarly scant, if methodical. I have, for instance, a small stack of his notebooks, maintained over seventy years. Five, in total. As follows:

1 A discoloured brown notebook, Where Is It? printed in black across its cover, in which my father maintained a list of all the books he read from January 1939 until he lost his sight in the late 1990s. Seven hundred books in total, ordered both alphabetically and chronologically, with a column indicating the month and year they were finished, and a column indicating how many books by that author had now been read. He kept this notebook by his bed, where he did most of his reading, for as long as I remember.