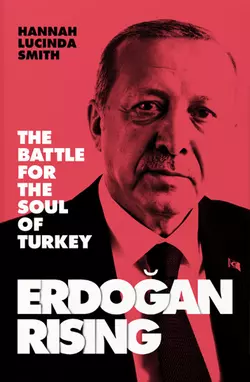

Erdogan Rising

Hannah Lucinda Smith

Everyone has heard of Erdogan: Turkey’s bullish, mercurial president is the original postmodern populist. Around the world, other strongmen are now following the path that he has blazed. For the first time, ERDOGAN RISING tells the inside story of how a democracy on the fringe of Europe has succumbed to dictatorship. Hannah Lucinda Smith, Turkey correspondent with The Times of London, has witnessed all that has befallen Turkey and the wider region since the onset of the Arab Spring. From the frontlines of the wars in Syria and eastern Turkey, through the refugee crisis and the attempted coup against Erdogan, she traces how chaos in the Middle East has blown back on a country that was once heralded as the model of Islamic democracy. With access to key insiders, she also paints a vivid portrait of Erdogan’s descent from flawed democrat to staunch authoritarian.ERDOGAN RISING is a story rooted in Smith’s first-hand experiences of a country divided, told through the eyes of a rich cast of characters. She journeys into the Turkey where Erdogan commands a following so devoted they compose songs in his honour, adorn their houses with his picture, and lay down their lives to keep him in power. But on the other side – sometimes just a few hundred metres down the road – she also meets the Turks who are mourning the loss of the country they once knew.ERDOGAN RISING serves as a chilling warning of democracy’s fragility – and reveals how much people can change.

ERDOĞAN RISING

The Battle for the Soul of Turkey

Hannah Lucinda Smith

Copyright (#ulink_18d5260e-b0c6-55ec-91ed-289d403bc1db)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Hannah Lucinda Smith 2019

Cover image © Getty Images/Bloomberg/Contributor

Hannah Lucinda Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008308841

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008308865

Version: 2019-08-26

Dedication (#u707da21c-7862-5bb4-965a-8c8498fbf5b1)

For my dad, who planted so many seeds

Epigraph (#ulink_fef9ac80-28c2-5e9d-8505-1be4a7229e3a)

Yet the school of Turkish politics was so ignoble that not even the best could graduate from it unaffected.

T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Contents

Cover (#u43f9da31-5fac-5ea9-be8f-ec69aa318b4f)

Title Page (#u3460cdbc-8042-5fd3-a5ab-69240409d4dd)

Copyright (#ucc6ae4ae-4d3c-54db-8baf-ed70bc98a32f)

Dedication

Epigraph (#ubf605a37-2e16-5e9a-8f1c-4ec16f01696f)

Maps (#ucef7d24f-63d0-5cd3-aaac-3b97a16dfd90)

Cast of Characters (#u9ac5fbd4-102a-5197-8e9f-a1f55e18145a)

Acronyms (#u6fe90fcb-8142-56e1-915a-ddf37021bed3)

Timeline (#u14051206-3a22-5325-bc38-43553db00774)

Introduction (#u3fa52145-3157-5af4-a8b0-8aeaa69746fe)

1 Two Turkeys, Two Tribes (#u2df00b5f-e992-5292-8f77-1015baf606af)

2 Syria: The Backstory (#ue6693044-1851-5713-b562-02e629443993)

3 Building Brand Erdoğan (#u1fa676d2-add5-5317-978c-2c3f90ecea4f)

4 Erdoğan and Friends (#u2fc104dd-82db-58fd-9253-79b777b60d3d)

5 Syria: The War Next Door (#litres_trial_promo)

6 The Exodus (#litres_trial_promo)

7 The Kurds (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Peace, Interrupted (#litres_trial_promo)

9 The Coup (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Atatürk’s Children (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Erdoğan’s New Turkey (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Spin (#litres_trial_promo)

13 The Misfits (#litres_trial_promo)

14 The War Leaders (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Erdoğan’s Endgame (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

MAPS (#ulink_2b6042e4-a4ea-5e54-9ee2-2b513b40df10)

Turkey (#u11b8d032-093f-56e7-b056-f227d1f8cc7a)

Syria and Turkish border region (#udc1acf60-fd99-5d37-8de9-8c021f1257a5)

Refugee smuggling routes from Turkey to Europe (#litres_trial_promo)

Kurdish region of Turkey, Iraq and Syria (#litres_trial_promo)

Istanbul (#litres_trial_promo)

Areas where Turkish army is fighting in northern Syria (#litres_trial_promo)

CAST OF CHARACTERS (#ulink_b58fb3af-8acb-5096-8c93-210ebf0bbe4f)

ACRONYMS (#ulink_feb07a4d-c0d7-53c0-9452-b713786beecb)

TIMELINE (#ulink_61bec080-009c-523b-84fc-9be61b3ac0fd)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_a86fede9-202c-5d46-99fb-42201d149f09)

July 2016

It is less than forty-eight hours since rogue soldiers tried to kill him and here Erdoğan is, back on stage. The sun is setting and the call to prayer is sounding, and the president is wiping a tear from his eye.

‘Erol was an old friend of mine,’ he starts, then breaks. ‘I cannot speak any more. God is great.’

Erol Olçok: Erdoğan’s ad man, his trusted spin doctor, his loyal friend. One of the first to race to the Bosphorus bridge last night, his corpse now before us in a coffin.

Nothing will be as it was before, for Olçok’s family, for Erdoğan, or for Turkey. Two nights ago, as Istanbul’s glitterati sat drinking on the banks of the Bosphorus, tanks filled the bridge and war planes split the skies. The army was revolting against Erdoğan – but soon Erdoğan’s own infantry was on the streets, with Erol Olçok at the first line. Bare-chested young men stood side by side with headscarved women in front of machine-gun fire on this midsummer night; others lay down on tarmac in front of rolling tanks. And as fortunes turned against the putschist generals, Erdoğan’s angry, shirtless, sweaty men removed their belts to whip the coup’s surrendering foot soldiers. Their twisted faces were lit with the perfect aura of an early summer’s morning in Istanbul: a glorious backdrop of dawn over the city that spans two continents. The images flew around social media within minutes. They were beautiful, and they were horrifying.

The coup has been crushed but the toll is huge. Two hundred and sixty-five people have died over the bloody span of this night, more than half of them civilians who came out to resist in Erdoğan’s name. Erol Olçok was shot dead alongside his sixteen-year-old son, Abdullah, as soldiers fired into the protesters on the bridge. Thousands more have been injured. There are still sporadic bursts of fighting as suspected plotters resist arrest; Istanbul’s airspace reverberates with the roar of patrolling F-16 fighter jets. The streets have been hauntingly quiet all weekend, as Turks stay inside, watch the news and pray.

Among the dead: a local mayor shot point blank in the stomach as he tried to speak with the soldiers; the older brother of one of Erdoğan’s aides; a famous columnist with the pro-government newspaper Yeni şafak. A crack team of special forces soldiers had burst into the Mediterranean resort where Erdoğan was holidaying, ready to kill him if necessary and missing him only by minutes.

Erdoğan has already bounced back, his close brush with death seemingly leaving no dent. He has returned to Istanbul, banished the soldiers back to their barracks, and called the coup attempt a ‘gift from God’ that will allow him to finally cleanse the state of those trying to destroy it. Six thousand people have been detained by the time he addresses the thousands-strong crowd at Erol Olçok’s funeral, at a mosque on the Asian side of Istanbul. The imam implores God as he leads the prayers for the slain man and his son: ‘Protect us from the wickedness of the educated!’

A weight is descending on Turkey. Each night Taksim Square fills with huge crowds of Erdoğan’s supporters, turning out to make sure his enemies don’t come back. Within days a state of emergency is declared, and every day thousands more suspected collaborators are arrested. The alleged ringleaders are paraded on state television with black eyes and bandages around their heads.

Privately, friends tell me they are worried. Goodbye to the Republic, writes one by text message. Goodbye to democracy.

The heart of my Istanbul neighbourhood, which usually bustles at all hours with street sellers, taxi drivers and prostitutes, is near-silent the morning after the coup; the pavements empty, the traffic thinned down to a few lonely cars. The only people I bump into as I walk around the deserted streets are the women who always stand on the main thoroughfare on a Saturday, selling black-and-white postcards to the shoppers. Usually they ask for five liras for this low-resolution print of Atatürk, father to the Turkish nation. Today, a middle-aged woman with blonde perm presses one silently into my hand.

‘Man, this is nothing but a country of cults,’ says my friend Yusuf a few days later, dazed and still trying to make sense of what is unfolding. ‘It’s Jerusalem in the Year Zero.’

In the years that have passed since July 2016, as I have filled newspaper column inches with stories of Erdoğan’s swelling crackdown on his opponents, his skewed election wins and questionable wars, I have been asked the same question time and again: ‘Why doesn’t the West just cut Erdoğan off? Make him a pariah, and leave him and Turkey to go their own way?’

The morality is complex but the answer is simple: we can’t turn our backs on Turkey because Turkey and Erdoğan matter. Forget old clichés about East-meets-West – it is far more important than that. Here is a country that buffers Europe on one side, the Middle East on another, and the old Soviet Union on a third – and which absorbs the impacts of chaos and upheaval in each of those regions. During the Soviet era, it took in refugees from the eastern bloc looking to escape the despotism of communism. When that empire collapsed, it became a place where the poor ex-Soviets went for work, and the rich showed up to party. Now, with the Middle East sinking into ever-greater turmoil, it is the world’s biggest refugee-hosting nation, with five million from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and others.

Turkey is a member of the G20, and is recognised as one of the world’s largest economies. It has the second biggest army in NATO, the Western military alliance which, with the rising expansionist ambitions of Russian President Vladimir Putin, is finding itself sucked into a new Cold War. More than six million Turks live abroad, the street ambassadors of a country that trades and negotiates with almost every other nation on earth. This is not a far-off hermit-state, isolated from the rest of the world. It is a major player, vital to global security and prosperity.

For millennia, the ground on which modern Turkey stands has been coveted and fought over because it stands at the nexus of trade routes and civilisations. To see it for yourself, spend an hour people-watching under the soaring ceiling of the new Istanbul airport, the biggest of Erdoğan’s increasingly outlandish vanity construction projects. It was opened in April 2019, and the Turkish government says that more than 200 million people will pass through its halls by the year 2022, making it the biggest and busiest in the world – twice as many passengers as Atlanta Airport, two and a half times as many as Heathrow. Cruise through its duty-free shopping area and you will spot Gulf Arab women wrapped in black fabric with only their eyes showing alongside sunburnt and flustered Brits in ill-advised tank-tops and shorts. There will be dreadlocked backpackers, preened Russian princesses, and, if you time it right, Islamic pilgrims swathed in white sheets making their way to Mecca. There will be people with wide Asiatic faces, and statuesque African women swathed in fabulous prints. Turkey sits at the centre of all of this.

It sits, too, at the centre of the journeys that the people on the wrong side of globalisation are making – the illicit trafficking routes that stretch from the Middle East and Africa, through Turkey and the Aegean Sea to Europe. In Istanbul’s backstreet tea shops another kind of travel market is flourishing, no less buoyant than that in the ticket halls of the new Istanbul airport. Here, shady men in leather jackets cut deadly deals with desperate people. Survival does not come guaranteed with a smuggler’s ticket to Europe, but it will cost you more than a budget flight from the shiny new airport.

So let’s think about what might happen if Erdoğan were to turn Turkey’s back on the West entirely, or if the country were to descend into full-on chaos. That surge of people in 2015, travelling from Turkey’s shores to Greece in search of a new life in Europe? That was nothing. There are millions more in the developing world still desperate to make that journey, and a collapsed Turkey could be their back door. What if, even worse, there were to be a major conflict or economic collapse in Turkey itself? Not only would thousands, perhaps millions, of Turks join the flow to Europe, but shrewd leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin would be quick to capitalise on the chaos to expand his territories and influence, just as he has done in Syria.

Erdoğan is no fool. He knows how important he is and he plays on it, often seeming to push his Western allies’ buttons just to see what will happen. He may sometimes look like a man deranged, but he is also a smart political operator who was refining his brand of populism a decade and a half before Donald Trump cottoned on. If Western countries want to contain and control Erdoğan – as they will have to if they are to keep Turkey stable and engaged in the world – then first they need to understand him. More than that, they need to understand why so many Turks adore him.

What is there to adore? On the face of it, not very much. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan lives in a thousand-room palace complex, Aksaray (White Palace), that he built almost immediately on becoming president. He and his followers have a taste for outlandish historical dressing-up. In a photo call with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, he posed on the staircase of Aksaray with soldiers decked out in costumes from the various eras of the Ottoman Empire. Despite his constant harping on about his working-class roots, and his apparent championing of the underdog against the elites, his wife and daughters dress in haute couture from the famous fashion houses of Europe.

The party Erdoğan leads, the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP), is the most successful in Turkey’s democratic history, even though it has never won more than 50 per cent of the vote. Erdoğan himself has stood at the helm of Turkish politics longer than any other leader in the country’s history. Since first becoming prime minister in 2003 he has quashed the power of the military, rewritten the country’s constitution, remoulded its foreign relations and mastered divide-and-rule politics better than any other current world leader.

Erdoğan’s grip on power might often appear shaky – he only just clinches victory each time he takes his country to the ballot box. But it is this constant sense of threat, this dread that he could be ousted and everything go back to the way it was before he came, that galvanises his supporters. He is not an Assad or a Putin, who use their faked and overwhelming electoral victories to cling on in their palaces. Erdoğan’s continuing dominance over Turkey rests as heavily on those who despise him as it does on those who idolise him. In order to be loved more, he must show his fanbase that there are those who are ready to overthrow him – and could feasibly do so. So, too, must they sense the constant threat in order to feel the wave of overwhelming ecstasy when he comes out on top after yet another crisis – and there have been many of those.

Turkey is still officially a candidate for EU membership, yet in my time covering this country as a newspaper correspondent I have been detained by the police twice, tear-gassed more times than I can remember, and had a Turkish tank turn its turret on me as I tried to speak with Syrians fleeing an onslaught of violence behind the closed border. From my front door I have watched the country I call home nosedive down the rankings for democracy, press freedom and human rights. Like every other journalist in Turkey I am constantly reconfiguring the limits of what I can say. Can I laugh? Criticise? Question? The threat of imprisonment or deportation always lingers in the air for the country’s international press corps, but for Turkish journalists it is real. Some sixty-eight are currently behind bars, the highest number of any country in the world. Add to them the tens of thousands of academics, opposition activists, serving politicians and alleged coup plotters who are also languishing in jail, waiting for trials that are likely to take years to come to court, and you start to get a sense of the kind of country Turkey has become – although a tourist searching for a cheap holiday might still look at the weak lira and the turquoise seas and happily bring their family here for a fortnight. While the package-deal masses race to the all-inclusive resorts and adventurous weekenders explore Istanbul’s atmospheric backstreets, Turks are watching their savings crumble, food prices soar and their children frantically search for any way out of the country.

To write – and to live – under Erdoğan’s tightening authoritarianism is to cohabit with a voice in your head that asks Are you sure you want to say that? every time you press send on an article or crack a joke with a stranger. It is to see your tendency for social smoking soar into a daily, furtive habit that you indulge by the window late at night, and then to look in the mirror in the morning and realise that the faint worry line between your eyebrows is setting into a deep crevice. Dictatorship screws with your sex life; it makes you go through an internal checklist on every person you meet – what are they wearing? Where are they from? Who do they work for and how far can I trust them? I hear my neighbours rowing more often these days, witness more fights breaking out on Istanbul’s streets. The Turks who love the way things are going like to rub it in everyone else’s face. The Turks who hate it usually spill everything to the Westerners they meet – some of the few safe sounding boards they have left. Conversations that start with ‘How long have you lived in Turkey?’ usually come round to ‘Why on earth do you still stay?’ The stress of wondering if your phone is tapped and your flat being watched slows down your brain, becomes a tiring distraction, while at some point, you realise that all your conversations with friends come back to politics, and that although there is plenty of material for cynical, satirical humour none of it makes you feel much better once you’re done laughing. To live in this system is to watch people you know be seduced by power and money, and happily throw away their moral compass as they pursue them. It is to suck up to people you despise because in order to survive you have to – and then to start despising yourself.

All of this creeps up on you, and by the time you realise what you are looking at it is already too late. It was only after the coup attempt that I saw clearly what had been happening all along – the descent of Turkey’s shaking democracy into one-man rule, the dawn of the state of Erdoğan. While I was focusing on the minutiae of daily news, on the war in Syria and the refugee crisis in Europe, his dominance had grown so entrenched that he had become inseparable from the state, and the state indivisible from the nation. Now, the answer to the eternal question posed by every journalist in Turkey is that it is fine to laugh and question and criticise – so long as you leave Erdoğan out of it. But in a country so monopolised, that leaves very little room for any discussion at all.

I have seen Turkey and Erdoğan through seven elections, dozens of terror attacks, a coup attempt, a civil war, foreign misadventures, slanging matches with Europe, mass street protests, a refugee influx and a massive purge of the public sector. And each time, when I have thought, this must be it, this will finish him, he has come out on top even stronger.

I have to give it to him – Turkey’s president has handed me some great material. Often, I have wished I could hand it back.

Erdoğan is the original postmodern populist. In power for seventeen years, his latest election win in June 2018 means he will stay until at least 2023. Already there is a generation of Turks who can remember little or nothing before the Erdoğan era, and his detractors have much to worry about. They fret over his creeping Islamisation of Turkey, once the staunchest of secular states. They point to his fierce crackdown on Kurdish rebels in the east of his country, where hundreds of thousands have been killed or displaced, and his cosiness with armed rebel groups of questionable ideology in Syria. Europe, which once saw Erdoğan as its darling, now deals with him increasingly as if he were an obnoxious teenager. The inhabitants of the Greek islands within spitting distance of the Turkish coast hold their collective breath and brace each time he threatens to open his borders to allow hundreds of thousands of migrants to flow across the Aegean in cheap plastic boats.

I have spent six years watching Erdoğan, speaking to his followers, and sniffing the winds. I think about him every day and write about him on most days, even though we have never met. But I never set out to be an Erdoğan-watcher, or even to be a Turkey correspondent.

In early 2013 I moved from London to Antakya, a tiny town on Turkey’s southern border with Syria, to pursue a career as a freelance war correspondent. The war next door had turned Antakya into a busy hive of spooks, arms dealers, refugees and journalists. The Syrian rebels had captured two nearby border crossings from President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, and I spent a year crossing back and forth through them into Syria to report on the spiralling slaughter. But as Syria turned darker and colleagues started to go missing at the hands of criminal gangs and Islamist militias, the journalists dropped away from Antakya. Along with most of the Syria reporter crowd I moved north, to Istanbul, where not so much was happening.

The huge Gezi Park protests, which in the spring of 2013 had briefly morphed from small environmentalist demonstrations into the most serious street opposition Erdoğan had ever faced, had now petered out into leftist forums scattered across Istanbul’s upmarket districts. They were happy protests – anyone could stand on a soapbox and, instead of clapping (too bawdy and overwhelming), the audience would wiggle their raised hands in appreciation. I doubt they caused Erdoğan too much anguish. For a year or so after Gezi, small-scale street demonstrations became the city’s number one participation sport – with protagonists boiled down to a hard core who just seemed to enjoy getting tear-gassed. One student ringleader I interviewed talked about upcoming protests as ‘clashes with the cops’, as if that were the main point of the event. The demonstrations became so common and predictable they were more of a nuisance than news. Several times over the course of that year, tear gas seeped into my bedroom as I tried to sleep.

I was bored and sad. I had left Syria, a story I had moved countries for and invested so much energy in. I yearned for the day I could go back and start reporting from there again. I was still dating a Syrian man down in Antakya, and I spent half of my time there with him. Strange as it feels to remember it now, there just wasn’t much of a story up in Istanbul.

But one day I fell in love. Travelling back from Antakya to Istanbul on the cheap late-night flight, I looked out of the window as the plane came in to land in a huge swoop across the city. On either side of the black scar of the Bosphorus, millions of pinprick lights marked out the shape of the shoreline, the traffic-clogged roads, the bridges and the palaces. From above, this scruffy city glistens, and I was glad to be back: it’s a feeling I still get every time the seatbelt sign comes on over Istanbul. It had taken me six months to realise that my banishment from Syria had landed me in the most beautiful, melancholy, fascinating city in the world. Gradually I stopped going down to Antakya, and my relationship with the Syrian fell away.

So, by chance rather than by my own good judgement, I was one of the few reporters based in Turkey full time when the news started flowing – the bombings, the diplomatic spats with Europe, and the overwhelming interest in Erdoğan. As the months progressed, I realised that even the most parochial, insignificant Turkish story could make a headline if Erdoğan were somehow involved. One I particularly remember is a story about his wife, Emine, and a speech she had made suggesting that the Ottoman sultans’ harem, the place where scores of potential sexual partners were kept, could be considered a bastion of feminism. The Western press went nuts – even though there is a serious line of academic debate that would concur with Emine. The interest in Erdoğan, as well as the growing chaos in Turkey, soon landed me regular work filing reports for The Times.

I found myself fascinated by him, too. The first time I saw Erdoğan in the flesh was not for a story – it was just because I happened to be in the area and was interested. In May 2013, while I was still living in Antakya, a double car-bombing hit Reyhanlı, another small Turkish border town hosting thousands of Syrian refugees. The attack was the first spill-over from the Syrian conflict, and the toll was horrific: fifty-two people killed and the heart of the town ripped out. Pieces of seared flesh were later found in the town’s sewers, so intense was the force of the blasts. Some Syrians headed back across the border into the war zone, fearing they might soon feel the brunt of the locals’ anger if they stayed. A week later, Erdoğan went to Reyhanlı to speak to the people. As it was only half an hour down the road from Antakya, I decided to go.

Compared to what I would see in later years, the crowd then was small and calm and Erdoğan’s speech was measured. But that day I noticed certain things I would go on to see again and again: how hundreds of people appeared to have been bussed in from every corner of the country, how party volunteers were handing out flags and baseball caps which, when televised, gave the appearance of a sea of red, and how the people who had showed up seemed to care far more about being close to Erdoğan than about what had happened in Reyhanlı.

How different that low-key event was to the time I saw him four years later, on a chilly May Sunday in 2017. It was a month after he had snatched narrow victory in a constitutional referendum to switch legislative power from the parliament to the president, and the AKP was holding its party congress in Ankara’s main basketball arena. By the time I took my seat at 8 a.m., the entire place was packed and rowdy with young men chanting for their hero. Erdoğan was due to take the stage around noon, to reclaim his place at the head of the party. He had nominally stepped down when he resigned as prime minister and was elected president three years earlier – the head of state was supposed to be politically unaffiliated according to the old, now-discarded constitution. In reality he had never loosened his grip over the party. He continued to campaign for the AKP in parliamentary elections, and had publicly ousted a prime minister who had dared to stray too far from his line.

As a political spectacle, the congress was incredible. There were men in the crowd who had arrived dressed as Ottoman sultans, sitting alongside Kurdish women holding banners proclaiming they were from şırnak, an eastern town that had recently been decimated by fighting between Turkish security forces and Kurdish militants. ‘Everything for the homeland!’ they whooped, ululating as Middle Easterners do at weddings – a bizarre celebration of their home town having been smashed to rubble. Music boomed non-stop from the speakers – a limited repeat playlist of Ottoman marching music, and the referendum campaign song titled ‘Yes, of course’. The one that got the loudest singalong was the dombra, a paean to Erdoğan and an unashamedly cringing anthem. ‘He is the voice of the oppressed, he is the lush voice of a silent world. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan!’ the lyrics begin, continuing on a similar theme through four verses.

Erdoğan entered the building as scheduled, accompanied by his wife and son-in-law, the then-energy minister Berat Albayrak, who most believe he is priming as heir. Tubs of red carnations had been strategically placed around the edges of the stands and Erdoğan threw them out to his adoring crowd as he did a victory lap. The grey men on the stage must have felt rather outshone as they reeled through their dry lists of candidates for various posts within the party. For top job Erdoğan was standing uncontested, and that was the only item on the agenda that really mattered.

Turkey is different from the other countries falling under the sway of strongmen. It boasts not one, but two – perhaps even three or four – coexisting personality cults.

There is Erdoğan’s, a cult in the ascendant I have seen evolve before my eyes. There is the cult of Abdullah Öcalan, the grandfatherly-cum-psychopathic leader of the PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party – the Kurdish militia fighting against the state in eastern Turkey), who has been banged up in an island prison since 1999, yet still commands a huge following among the Kurds and their diaspora. As well as the Turkish PKK there are affiliated militias fighting in his name in Syria, Iraq and Iran. His appeal stretches to Western leftists who are so enchanted by his ideas on women’s equality and government without the state that they are willing to overlook the atrocities that his gunmen and women commit. As the latest peace process broke down in the summer of 2015, I went to interview Öcalan’s brother in the south-eastern mountains of Turkey, having been told I would find him an intelligent, sensible kind of guy who would give me an honest account of his notorious sibling. Mehmet Öcalan’s home-grown figs were delicious, but the interview quickly veered into the bizarre. He tried to convince me that his brother knew, and by extension controlled, exactly what was going on in the Middle East day by day from his solitary prison cell, thanks to his psychic powers. Throughout, he referred to him as ‘Serok’ (Kurdish for ‘leader’) – never Abdullah or ‘my brother’.

There was, and perhaps still is, the cult of Fethullah Gülen, a wizened Islamic cleric who has been commanding a network of secretive followers since the 1960s. He has been living in exile on a secluded and heavily guarded ranch in Pennsylvania, USA since the 1990s, but until recently his devotees occupied high ranks within the Turkish bureaucracy, police and judiciary. They used their positions to bully and punish anyone who opposed them, most notably secularists who were uneasy with the idea of a secret Islamic cult wielding so much power in their country. Erdoğan and Gülen were allies, of sorts, until they fell out spectacularly in 2013 and began a personal war played out through the state. Erdoğan accuses Gülen of organising the attempted coup of 2016. At present, a Turk’s life can be ruined by the mere suggestion that they have at any time and in any way been affiliated with the movement.

And then there is the cult of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish republic and possibly the only man capable of raising a serious challenge to Erdoğan despite the fact that he has been dead for eighty-one years. Atatürk – or at least the Atatürk who is still very much alive in the imagination of today’s Turks – stood for almost everything Erdoğan despises, and vice versa. He was an unbending advocate for secularism, non-aggression in dealings with other states, and a Turkey that is allied to Europe and the West.

Atatürk has always been a Turkish hero, but increasingly he is also the figure Erdoğan’s opponents rally around. During the 2017 constitutional referendum campaign the streets of my Istanbul neighbourhood – a secular bastion that voted 81 per cent against Erdoğan’s plans to gather power in his own hands – turned into an open-air gallery of Atatürk-inspired artwork. The ‘İzmir March’, an anthem to militarism and Mustafa Kemal, was the unofficial theme tune of the ‘No’ campaign. It is common, both inside Turkey and without, to hear Erdoğan’s detractors bemoan how he is unravelling Atatürk’s legacy.

Maybe it said more about the state of the opposition than it ever did about the enduring strength of Atatürk. There is no question that this cult continues, but its cracks are beginning to show. Over the course of Erdoğan’s reign, those who have in the past quietly loathed Atatürk and all he stands for have found they can finally speak out. They are primarily the religious poor, dispossessed by Atatürk’s unbending secularism, though they also include liberals who wince at the thought of unbridled adoration in any direction. But those same liberals who once supported the downgrading of Atatürk’s legacy are now recoiling at Erdoğan’s transformation from man to deity by his followers. And so, Turkey has become a fascinating Petri dish – a perfect place to observe one cult of personality in the ascendant, alongside another in slow decline.

Over six years I have travelled to every corner of this huge, diverse, often baffling and always fascinating country, and have also reported on the chaos it borders in Iraq, Syria and south-eastern Europe. Along the way I have spoken to politicians, criminals, policemen, taxi drivers, warlords, flag-sellers, refugees … My notebooks are so stuffed with characters that the material could keep me writing for years. In Erdoğan, I have found the most compelling protagonist a writer could wish for.

But it wasn’t the coup attempt that spurred me to write this book, despite all its Hollywood drama and the front pages it garnered. That night in July 2016 was just the prologue, the scene-setter for the real tragedy that then unfolded. I started writing this book a year on, after the grandiose celebrations held on the first anniversary of the coup attempt revealed fully the depth of the personality cult that Erdoğan had assembled. By the time I had finished the first manuscript eleven months later, he had sealed power through the presidential elections that will keep him in his palace until 2023 – two decades at the top of Turkey.

This story is bookended by those two events, but at its core is the entire period in which I have taken a front-row seat at Turkey’s descent. When I arrived here in early 2013, thinking that I would stay for a few weeks to report on Syria before going back to my life in London, Erdoğan was just tipping over from being a flawed but largely tolerated democrat to a relentless autocratic populist. Within two years he had turned into a hate figure that the whole world had heard of – and then he led his country into its most turbulent era in decades. In the space of eighteen months in 2015 and 2016, Turkey suffered a refugee crisis, a wave of terror attacks, a fresh eruption of violence in its Kurdish region, and a coup attempt. Since then, even with some kind of daily stability and normality restored for most Turks, Erdoğan has consolidated his position further and stamped down harder on his opposition.

Spotting the narrative’s threads has not been easy: his path has not always been steady or clear. Multiple plot lines unfold simultaneously, linears converge and loop back on themselves. Events outside Turkey wash over its borders, feeding forces that are brewing inside the country while Erdoğan holds up his own skewed version of the world to his people like a fun-fair mirror. I worked forwards and backwards through shelves of my notebooks from Turkey and Syria as I wrote, trying to work out what I’d witnessed. I reread old diaries and rang up old friends, trawled through newspaper cuttings from the past twenty-five years and plundered the historical archives at The Times. I spoke to historians and political scientists and drew up huge lists of diplomats, Erdoğan’s insiders, lobbyists, advisers and opponents and contacted them all, asking them to speak either on the record or privately. Most of them ignored me, some of them refused. The ones that agreed usually did so on condition of anonymity, and each has shaded their own part of this portrait of Erdoğan and Turkey. Some names have been changed, usually in order to protect people who are still inside Syria or who have families there. In other cases I have referred to interviewees by first names only, or by the position they held. It is a mark of the current state of the country that I cannot thank or acknowledge by name most of the people who have helped me write this book; in the future, in better times, I hope I will be able to do so.

There is a vague chronology to this story, but Turkey never makes sense on a single timeline. To understand the present you need to link it to the past, and to unravel Erdoğan and his followers you must also acquaint yourself with all the other bit-part players who share his stage. Remembering recent history has become an act of rebellion in Erdoğan’s Turkey; memories are being erased and events rewritten as he fashions the country to his liking. By 2023, when the next elections are scheduled, the memories of the old parliamentary system will have faded and no one much under forty will have ever voted in an election in which he or his party did not, somehow, claim victory.

So this book is my attempt to document what I have seen, before it is erased from Turkey’s official story in the way that history’s winners always rub out the bits they do not like. It starts a year on from the coup attempt, in a country that has started to believe its own lies and the middle of a crowd high on the rush of its leader’s ascent.

1 (#ulink_4f0ab9b7-2ed8-595b-a9df-3b270213c419)

TWO TURKEYS, TWO TRIBES (#ulink_4f0ab9b7-2ed8-595b-a9df-3b270213c419)

July 2017 Coup anniversary

Stout old grandmas, svelte young women, mustachioed uncles and thick-set hard men: they are all moving together like a single being, and all waving Turkish flags high above their heads. I’m in the middle of a river of red. When I break away and climb up onto the footbridge over the highway they look like microdots in a pixellated image. I squint, and their fluttering crimson flags merge into one pulsating mass.

Serkan watches them stream past with a humorous, anticipatory eye.

‘BUYURUUUUUUUN!’ he shouts – the call of the Turkish hawker, which imperfectly translates to: ‘Please buy from me!’

A family stops to eye his wares, which he has spread on the pavement – a rough stall laden with cheaply made T-shirts, caps and bandanas on which are printed the serious face of a man with a heavy brow and a clipped moustache, usually depicted beneath an array of sycophantic headings:

OUR COMMANDER IN CHIEF!

OUR PRESIDENT!

TURKEY STANDS UPRIGHT WITH YOU!

Serkan – his own mannequin – dons the full set, a cap above his round and ruddy-cheeked face, one of his T-shirts stretched over his middle-age paunch, and his accessories of armbands and a scarf. He wears it all with aplomb, his friendly grin at odds with the stern printed image of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on display.

‘It’s just business,’ he confides once his customers have moved on. ‘I’ll sell at any political rally, but right now the Erdoğan merchandise sells the best.’

A few metres further down the pavement the next seller, Savaş, expands.

‘Maybe it’s because the people who buy the Erdoğan stuff are younger,’ he ventures. ‘But I sell about six or seven times more at the Erdoğan rallies than I do at the others.’

He is right. Turkey’s youth, its largest and most frustrated demographic, is over-represented in the crowd packing through an unremarkable Istanbul neighbourhood this July evening. There are families here too, and ballsy young women in headscarves hustling along in tight groups. One of them waves a printed placard: WE HAVE ERDOĞAN, THEY DON’T! But the more I keep moving with the mass of people, the more I might fool myself that I’m on my way to a football match.

Tonight these streets are theirs – the Erdoğan fanatics – celebrating the first anniversary of the failed coup, which, in the year since the guns fell silent, has opened the way for Erdoğan to grab even more power. For this crowd, that is a reason to party. We are heading for one of the icons of Istanbul, the graceful bridge arching over the Bosphorus Strait that, when the sun sets, sparkles with thousands of colour-shifting fairy lights. One of my favourite indulgences is to cross this bridge in a speeding public minibus late at night, boozy and sentimental. Look to the right as you cross from Europe to Asia and you see the southern end of the strait open out suddenly into the Sea of Marmara, backlit by the silhouettes of Istanbul’s Ottoman centre in the distance. To your left you see a decadent spread of rococo palaces along the river banks, alongside the turrets of the Kuleli military high school, alma mater of generations of ambitious young officers, and the minarets of the monumental, neo-Ottoman Çamlıca Mosque, Erdoğan’s flagship vanity project. However rowdy the bus is in the early hours, it always falls silent on the approach to this mesmerising vista.

Within weeks of the coup attempt the bridge was renamed and rebranded – now it is the 15th July Martyrs’ Bridge, a monument to Erdoğan’s finest hour. The road signs have been rewritten, and new announcements recorded for the bus routes. On this anniversary night it is the epicentre of the commemorations; the roads leading onto it have been lined with loudspeakers blasting out patriotic music to spur on the thousands of people milling around.

Erdoğan is the star of this show. First, he unveils a memorial to the martyrs. Stuck up on a grassy hill at the east side of the bridge, it resembles a space-age luminescent moon: huge, bright white and incongruous. Inscribed inside it are the names of the civilians who died. The Islamic funeral prayer is broadcast from here loudly, twenty-four hours a day, though, as one of my cynical friends points out, it is impossible to hear it over the roar of the traffic.

Next come the speeches from the stage set up at the apex of the bridge. The immediate audience is VIP only, but big screens have been arranged in the area just outside the eastern entrance for the tens of thousands who are here in order to be in close proximity to their leader. The event is also being streamed live on every Turkish TV channel. As Erdoğan takes his seat, a range of dignitaries take turns to pay homage.

‘Thank you to our martyrs, and thank you to our commander in chief!’ shrieks the announcer. ‘Recep. Tayyip. ERDOĞAAAAAAAAAN!’

Devout men in skullcaps spread flattened cardboard boxes on the road and kneel in the direction of Mecca. Everyone else falls silent as the announcer rolls through the names of the dead. Then Tayyip himself takes to the podium to deliver a speech full of invective against the traitors and the meddling foreign powers, packed with promises to chop off the heads of those responsible. He is then chauffeured to his private jet, which will fly him and his retinue to the capital, Ankara, where they will do it all over again.

Those who do not belong to Erdoğan’s fan club escape to Turkey’s liberal coastal towns, avoid the TV and newspapers, and drink cocktails on the shores of the Mediterranean until it is over. Yet their president finds them. Shortly before midnight, anyone using a mobile phone gets Erdoğan’s recorded message on the other end of the line: ‘As your president, I congratulate your July fifteenth democracy and national unity day. I wish God’s mercy on our martyrs and health for our veterans,’ he says in his distinctive, drawn-out tones. I get six calls within an hour from friends who just want to test it out, not quite believing that even Tayyip would pull such a stunt.

Events like the coup anniversary have become Turkey’s rock concerts – especially since the actual concerts dried up. I had tickets to see Skunk Anansie, a band I was obsessed with as a teenager, with an old school friend in Istanbul a few days after the coup. But the band cancelled the gig soon after the news broke of the 15 July massacres. Attendance at football matches – a working-class passion in Turkey – has also fallen since the Passolig, an electronic ticketing system designed to stamp out hooliganism, was introduced in 2014. Turkish politicians, though, always seem to find reasons to get on stage to bellow to their flag wavers.

At least the street sellers still have events where they can hawk their merchandise.

‘I used to sell at the football matches,’ says Mehmet, a small, gnarled old man with a thick grey moustache and a clear disdain for this evening’s show. ‘You know – fake team shirts, scarves, that kind of thing. Then they started cracking down on us. The Zabıta’ – a unique Turkish cross-breed of trading-standards-officer-meets-traffic-warden – ‘started issuing fines, and now the teams’ lawyers walk around and check out our stalls. If they see you selling anything with logos, they sue you.’

‘When did the crackdown begin?’ I ask.

‘When Erdoğan came to power!’ he laughs as he replies.

Even here, at Erdoğan’s own event, Mehmet is being screwed: official event marshals are riding around in pick-up trucks laden with Turkish flags and baseball caps bearing the official coup commemoration logo, cheap mementoes they are handing out for free. I pick some up to add to my burgeoning collection of Turkish political tat, and continue on towards the bridge.

Just before the arch takes flight the crowds grow so thick I lose the will to keep pushing through. Instead I stop, look around, and take in the febrile buzz. A friend and fellow journalist has texted me, warning that the riled-up crowd has been chanting abuse at the CNN news crew. I thought that, with my notebook firmly in my rucksack, I would blend in. I was wrong.

‘Excuse me, are you a journalist?’ asks a slight young woman in black abaya and headscarf who emerges from nowhere, catching me by my elbow, and off guard.

Yes, I reply, I am.

‘Which channel?’

Her eyes are hard and suspicious, not friendly as those of nosy Turks usually are. I tell her I work for a newspaper, not for TV, but she doesn’t believe me.

‘Really?’

My companion for the evening was caught in a mob attack during the coup in Egypt four years ago, and is alert to the warning signs. Other people are beginning to look around, so I shake the woman off and we push deeper into the crowd. When I stop again, I notice a young man with terrible teeth, dark brown and shunted into his mouth at weird angles, gazing up at the screen and grinning.

‘Tayyip!’ he yells as live pictures of his hero, just a few hundred metres down the road, flash up. ‘TAYYIIIIIIIIIIP!’

He is so enraptured he doesn’t notice me staring.

The Justice March

One week earlier: it’s the other tribe’s turn. On a humid Sunday afternoon scores of Turks in white T-shirts descend onto a corniche on the Asian bank of the Bosphorus. There is no Erdoğan merchandise on sale here.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the opposition, has just walked here from Ankara – a 280-mile, three-week trek in the blistering heat, accompanied by hundreds of police officers. Along the way he has gathered thousands of supporters shouting ‘HAK! HUKUK! ADALET!’ (Rights! Law! Justice!) as they weave through Istanbul’s poor outer suburbs. One side of the highway leading into the city has been shut down for the marchers. Vans travelling up the other side beep their horns in solidarity. From the balconies of crumbling concrete apartment blocks, women swathed in black burkas shake their fists and scream in fury. Others hold up their hands in a four-fingered salute with the thumb tucked under – the sign of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, adopted by Erdoğan’s fan club.

Kılıçdaroğlu walks the final mile alone – a small, defiant figure surrounded by rings of black-clad cops. No one thought he would get this far. When he began walking, spurred by the arrest of one of his party members, he was mocked. Now he is about to step on stage in front of hundreds of thousands – perhaps millions – of people who support him, and who despise Erdoğan.

But Kılıçdaroğlu’s face wouldn’t look quite right on a T-shirt. He is grey, diminutive, pushing seventy. A career bureaucrat. A man who has spent his seven years at the head of the Republican People’s Party, or CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi), Turkey’s secularist party, eclipsed by six-foot ex-footballer Erdoğan. So instead of Kılıçdaroğlu’s face the street sellers’ wares bear the face of a blue-eyed blond with sharp cheekbones and a debonair dash: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who not only founded Kılıçdaroğlu’s party, but also the Turkish republic. He was a polymath, a womaniser and a thirsty drinker, a war hero, a visionary and a statesman. And he is a hero – to this half of the country. He has been dead for eighty-one years, and he is still Erdoğan’s biggest rival.

Here is the Atatürk legend. He was born simple Mustafa, son of a former army officer and a housewife, in 1881 in Thessaloniki, now in modern Greece but at that time one of the richest and most diverse cities in the Ottoman Empire. He followed the familiar path for a bright boy from a modest background. First, he attended military school, where he studied Western philosophy alongside the bedrocks of literacy and numeracy, and was bestowed with the second name Kemal, meaning perfection, by a maths teacher. After finishing school he became an army officer.

He was serving an empire in decline. The Ottomans had once ruled a great stretch of the globe spanning Europe, Asia and Africa, but by the beginning of the twentieth century the peripheries were breaking away. The army Kemal joined was growing increasingly disloyal to the sultan, and by the onset of the First World War had all but overthrown him. Kemal was a lower-level player in the revolt, and a passionate advocate of reform. His experiences serving on fronts in the Balkans, North Africa and the Levant convinced him that such a huge, unwieldy, multi-ethnic empire could no longer survive and that it must be trimmed back to a Turkish nation state.

The Great War was the Ottoman Empire’s inglorious finale. By then it was being run de facto by the Young Turks, a cadre of military officers including Kemal. Meanwhile the sultan, Mehmet V, sat sulking in his palace in Istanbul, fully aware that almost all his power had drained away, even though by name he was still head of an empire.

Kemal was dismayed when his fellow officers decided to enter the war on the side of the Germans, but he fought with distinction. He secured his reputation as a war hero at the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915, when troops from Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand launched a huge naval attack on the Dardanelles, the last maritime bottleneck before Istanbul. Against all odds, the Turks led by Kemal beat them back in a final show of force – and then the empire crumpled entirely.

The Ottomans’ decision to ally with the Germans proved terminal. On 13 November 1918, just two days after the end of the war, British, French, Greek and Italian forces moved into Istanbul. Soon after, the Greeks seized a large swath of the Aegean coast and Thrace, the funnel of land leading from Istanbul into Europe. Meanwhile, the French had moved into the cities of the south-east, close to the current border with Syria, as well as the coal-rich regions of the north.

A new sultan, Mehmet VI, did little to prevent the unpicking of his empire. In 1920 he signed the Treaty of Sèvres, which recognised the various foreign mandates in his own lands. The fight appeared to have gone out of the Ottomans – but it had not gone out of Mustafa Kemal. Almost as soon as the armistice was signed he began hatching plans to reverse the damage. Slipping Istanbul, he headed for Samsun, a city on the Black Sea coast in northern Turkey, and began building a national resistance movement. Despite opposition from the sultan, who ordered him to cease his activities, by early 1920 Mustafa Kemal had built a massive following and established an alternative parliament in Ankara, a small city on the Anatolian plain. From there, he launched the Turkish war of independence, seizing back the Anatolian territories, the coast and then, finally, Istanbul. The last British warship departed the old imperial capital on 17 November 1922. Aboard was Mehmet, the last sultan, expelled in disgrace by the new parliament set up by Mustafa Kemal. Mehmet returned six years later, in a coffin, having lived out his remaining years on the Italian Riviera.

Five days after Mehmet was discharged, the sultanate was dissolved. His cousin, Abdulmecid, was appointed caliph – head of the world’s Muslims – but his tenure was similarly short. Less than two years later, the caliphate was also abolished. The 600-year-old Ottoman Empire was over.

Mustafa Kemal had led a movement that saved Turkish pride and reclaimed great swaths of its territories. From the ruins of the Ottoman Empire he established a modern republic: in 1923 the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, recognising Turkey as a sovereign state. For most men, this might have been enough. But it was here that Mustafa Kemal’s most remarkable work began. As the first president of the republic, from its founding in 1923 to his death in 1938, he set himself an enormous task: to pick up his people, shake out their old habits and mindsets, and reshape them as citizens for the twentieth century. Among his more famous reforms was to scrap the Ottoman alphabet, written in the same script as Arabic, and replace this with Latin letters. He introduced secularism into the constitution and banished God to the private sphere, and had everyone choose a surname in the Western tradition, leading to a plethora of colourful monikers in present-day Turkey. It is not unusual to meet a Mr ‘Oztürk’ (‘pure Turk’), ‘Yıldırıım’ (‘lightning’) or ‘Imamoğlu’ (‘son of an imam’). Mustafa Kemal’s own choice, ‘Atatürk’, means ‘Father of the Turks’. And he advocated passionately for the equal rights of women.

For the people who wave his flag, Atatürk is the man who saved Turkey from the fate of some of its unfortunate neighbours. ‘If it wasn’t for Atatürk, we would be like the Arabs!’ is a common refrain. If that sounds bigoted to a Westerner’s ears, then some time spent in the Middle East might bring you round. Travelling and working as a woman in the Arab world can be infuriating at best, scary at worst. I have been heckled, grabbed, groped, patronised and scorned during my time working in Arab countries – simply because I am a woman –though I would like to pay tribute here to my scores of male colleagues and friends in that part of the world who do not fit the stereotype, and who have often saved me from those situations. In Turkey, women seem simply to sigh inwardly at embarrassingly clichéd chat-up lines, and learn how to deal with machismo displays of jealousy and the constantly hungry stares from men. What they don’t sigh at but have to bear is the appallingly high, and apparently rising, rate of domestic violence and killings of women at the hands of their male relatives. Yet in the secular neighbourhoods of Turkey’s western cities at least, women can live almost as freely as they do in the West. I can go running, Lycra-clad, in the morning, and hit bars and clubs wearing mini-dresses at night in Istanbul. Atatürk’s admirers would credit that to him – whether that is true or not.

Atatürk’s fan club is secular (at least politically if not always privately), relatively wealthy, educated, well-coiffed and decidedly less spiky to deal with. In short, they are almost the mirror image of the Turks who turn out for Erdoğan. During Kılıçdaroğlu’s long walk, a joke goes around that his supporters who can’t be bothered to walk alongside him are sending their drivers instead. The people who turn out to what has become known as ‘the justice rally’ look like professors, writers and engineers. There are large groups of middle-aged women who arrive on chartered coaches from faraway cities, cackling between themselves at crude jokes as they walk to the parade ground. I watch sweet old retired couples in matching JUSTICE T-shirts walking hand in hand along the corniche. These people belong to the same Turkey as the old ladies with fur coats and small dogs who live in my 1960s apartment block, clinging to their crystal tumblers of whisky, their cigarettes and all the former glamour from those heady days. There is no horror-show dental work on display here.

‘Aaaaaah, we’re among the beautiful people!’ says Yusuf, a Turkish photographer who is firmly of this world, even though it pains him to admit it. When I really want to needle him I call him a ‘White Turk’, the lazy label for this half of the country. It refers to the elites, the secularists, ‘those people who sit by the Bosphorus sipping on their whiskies’, as one of Erdoğan’s staunchest allies once put it, with a visceral sneer of disgust. The president is proud to represent the other half of Turkey – the poor, the religious, the marginalised. ‘Your brother Tayyip is a Black Turk!’ he once roared in a speech to his faithful. Whenever I call Yusuf a White Turk, he rolls his eyes and huffs a little. But he never denies it.

The walk down the corniche to the Maltepe parade ground, where Kılıçdaroğlu will take the stage, has the air of a genteel Sunday stroll. The white-clad masses lick ice creams and pause for tea in the kitsch waterside cafés. There is a happy, easy hum of conversation – I pick up snippets of holiday stories, and of updates on how the children are doing at university. There is less venom here than at Erdoğan’s rallies – but also less sense of drive and direction. These people lost control of Turkey fifteen years ago, but they still wear the easy nonchalance of power. Meanwhile Erdoğan’s supporters are still full of the scrappy aggression of the underdog. Old habits are hard to give up.

Kılıçdaroğlu, the bureaucratic grey man, has always made an easy target for ridicule. During his rallies Erdoğan plays videos showing the state of Turkey’s hospitals in the 1990s, when Kılıçdaroğlu was head of the state health department. Admittedly they were terrible back then, full of filthy wards and mind-numbingly long queues. The crowd boos whenever Kılıçdaroğlu’s face pops up on the screen. And as Kılıçdaroğlu begins his walk, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım – a Erdoğan loyalist to the bone – mocks him.

‘Why don’t you use our high-speed trains?’ he baits, highlighting the sleek new rail link, one of the government’s vote-winning projects.

But by the time Kılıçdaroğlu nears Istanbul Erdoğan is spooked. As thousands of Justice March supporters file past the neo-Soviet-style billboards for the upcoming coup commemorations it becomes embarrassing for Erdoğan: this inadequate rival, stealing his thunder? And so he starts accusing him of tacitly supporting both Gülen, the alleged ringleader of the coup attempt, and the PKK – a known terrorist organisation – through this endeavour.

‘Politics in the parliament has become impossible, so I’m taking it onto the streets. They can’t cope with my free spirit,’ a suntanned and fit-looking Kılıçdaroğlu tells me, back in his Ankara office five days after he has finished the march. With so few trusting the ballot box, these rally turnouts have become the new battleground.

Each time the politicians call their legions to the streets, fierce debate breaks out over the numbers. The CHP claims two million attended Kılıçdaroğlu’s Justice Rally; the office of the Istanbul governor (a government appointee) counters, saying the real figure was 175,000.

Meanwhile, the government’s claims for its own rallies – generally held in the purpose-built Yenikapı parade ground on the European side of Istanbul – always stretch into the millions. At the post-coup ‘Unity Rally’, they claim five million. At a pre-referendum campaign meeting, despite the large gaps in the crowd, they say one million. When I write in my report for The Times that the figure appears to have been inflated, pro-government journalists howl in protest. One accuses me of being a Zionist trying to destroy Erdoğan. The headline in the rabidly loyal newspaper Sabah screams that ‘millions’ turned out on the bridge for the coup anniversary. But even the Sabah journalist loses faith by the first paragraph, revising the figures down to ‘hundreds of thousands’.

For perhaps the first time ever, Istanbul’s Office of the Chamber of Topographical Engineers finds itself in the position of political referee. It weighs in with a statement on the justice-rally numbers, couched in rather different language to the usual Turkish rhetoric:

The rally area of Maltepe is approximately 275,000 square meters. Participants were also located in an area that was closed to traffic, which is around 100,000 square meters. So citizens took part in the rally over a space covering 375,000 square meters … In estimating the participant number, it is usually accepted technically that three to six people are located per meter square, so it can be stated that at least 1.5 million joined the ‘Justice Rally’. Experts say that considering the fullness of the rally area, this number could even be as high as 2 million.

My own back-of-a-fag-packet calculations concur: the areas of the Maltepe and Yenikapı parade grounds are roughly similar, while the part of the bridge where Erdoğan’s coup commemoration was held is not large enough to hold more than 200,000.

‘They don’t inflate the numbers, they just make them up!’ Yusuf says, our calculations hieroglyphing pages of my notebook.

Mehmet the street hawker doesn’t need mathematics.

‘I spend my life in crowds and I know the size when I look at them!’ he says. ‘There were at least three million at the Justice Rally. They were lying when they said a hundred and seventy-five thousand.’

So, yes, Kılıçdaroğlu has boosted his image beyond anyone’s expectations. Yet over his shoulder looms the man who really called out the party faithful: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

The rivals

If you have ever read Daphne du Maurier you might recognise Erdoğan’s relationship with the blue-eyed blond. Just as the unnamed narrator of Rebecca obsesses over her husband’s dead first wife, it is easy to imagine how the thin-skinned Erdoğan, desperate to establish his own place in history, spends hours fretting over the continuing popularity of his biggest rival.

You could forget that Atatürk is no longer with us. He is so present in Turkey that you might expect him to pop up at a rally, or be interviewed on TV. Like the Queen, his face is so familiar it becomes difficult to see it objectively. Right now, he is the only person who might wield more power than Erdoğan. He is definitely the only one whose picture you will see more often as you travel around Turkey. Erdoğan’s face, always twenty years younger in photos than in real life, looms large from the banners strung between apartment blocks in conservative neighbourhoods. But it is Atatürk who hogs Turkey’s limelight.

It helps that he was photogenic – a natty dresser who instinctively understood the power of the camera at the exact moment the camera was becoming ubiquitous. Each stage of Atatürk’s career – officer, rebel, war hero, visionary – together with his transformation from conventional Ottoman gentleman to twentieth-century statesman and style icon, is represented in a series of classic images.

Anıtkabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum in Ankara, can probably be classed as his fanbase HQ, but you will find miniature shrines around every corner and underneath almost every shop awning. In his earliest portraits and photographs he looks like any other stiff-backed Ottoman officer. But in later images Atatürk swims, dances and flirts with the lens, dressed in finely tailored clothes and smoking monogrammed cigarettes. There is the famous silhouette of him stalking the front lines at the Battle of Gallipoli, deep in thought with a finger on his chin and a fez on his head. There is another of him in black tie and tails dancing with his adopted daughter, sleek in her sleeveless evening gown. There is the one where he stares directly into the lens, his cigarette in one hand and the other in his pocket, a Mona Lisa smile on his lips. There he is in a nerdish knitted tank top, teaching the newly introduced Latin alphabet to a group of enthralled children. The list goes on …

I like to try to guess the character of any individual Turk through the picture they display. Whenever I see a military Atatürk pinned up behind a counter I imagine the owner to be a patriot who looks back on his own military service with pride and warmth. If they have opted for a besuited and coiffed Kemal, I wager them to be pro-Western intellectuals. If, as in one meyhane (a traditional rakı-and-fish restaurant) close to my flat, the walls are plastered with various portraits from the start of his varied career to its end, I guess them to be full-blooded Atatürk fanatics.

My own favourite is the picture pulsing with such life and humour that the first time I saw it, hung behind the cash register of an Istanbul bakery, I yelped in delight. It is a colour photo of Atatürk on a child’s swing, aboard a pleasure steamer on a trip to Antalya. It was taken three years before his death, and he is not a well man. His sunken bright eyes and his receding blond hair, his pallor and stout middle betray his love of drink; he would die from cirrhosis of the liver aged fifty-seven. Yet he is grinning so widely you can almost imagine him whooping as he flies. A second, less famous frame taken minutes before or after this one shows him standing on the swing with a young child peeping between his legs. This, I thought, is a personality cult I could get with – and a personality cult is what it is. Insulting Atatürk or defiling his image can still land you with a prison sentence, or at the very least the probability of a beating from the nearest Atatürk devotee. Back in 2007, under Erdoğan’s government, a court decided that all of YouTube should be blocked because it carried a few videos deemed insulting to Atatürk. The ban stayed in place for two and a half years.

Internet censorship is still widespread, although these days insulting Erdoğan is far more likely to bring down a court order. Meanwhile, though, Atatürk’s genuine appeal burns strong. It is not unusual to see young Turks use an image of Atatürk as their Facebook profile picture, or tattoo his signature down their arm. You can buy T-shirts, mugs, bumper stickers and keyrings emblazoned with his face. My own collection boasts a wine carafe, an egg timer and a compact mirror. In almost every town you can find small museums dedicated to him in some way, staffed by volunteers and visited by Turks who earnestly take selfies with the Atatürk waxworks. During Gezi, the 2013 summer of riots sparked by plans to concrete over the eponymous park in Istanbul, the young protesters quickly realised that if they added an Atatürk image to the anti-Erdoğan slogans they spray-painted on the walls, the authorities would not paint them over. The council workers charged with this unenviable task decided to walk the tightrope between the two camps by painting out the slogans while fastidiously leaving the Atatürks. Though Erdoğan might dislike it, Atatürk’s cult endures. And so, Erdoğan has nurtured his own.

Shortly before the parliamentary elections of November 2015 – a contest in which Erdoğan, by that time president, was not even running – I visited his home district of Kasımpaşa, a port neighbourhood in central Istanbul. In a backstreet shoe shop, I found Fatma Özçelik, a lively 59-year-old who had known Tayyip from childhood.

‘Ooooh, he was so handsome!’ she told me. ‘So tall. So handsome! Yes, he’s a bit aggressive on screen. But what can you do?’

I asked who she would be voting for.

‘Tayyip!’ she replied.

But Erdoğan isn’t on the ballot, I said. Did she mean she would be voting for the AKP?

‘Nope!’ she insisted. ‘Don’t like any of them! I’m telling you, the guys ruling the AKP now are terrible. They’re blaming Tayyip for all their shit.’

I pressed on. But would she be giving her vote to Ahmet Davutoğlu, the prime minister (later purged by his boss for being too independent of spirit), knowing that it would actually be an endorsement of Erdoğan?

‘Nope! I don’t like that Davutoğlu, I don’t trust him. I don’t like any of them – only Tayyip! They can’t replace him. It can’t be the AKP without him.’

She would not countenance any other option, and I never did get to the bottom of whether she would be voting or not.

Around the corner I dropped in on Ahmet Güler, perhaps the most famous barber in Istanbul, with the country’s most famous customer. A small TV screen in a corner of his shop played live footage of Erdoğan speaking at a rally in the Kurdish city of Diyarbakır. Both Ahmet and the cloaked and shaving-foamed customer in his chair had the same clipped moustaches as their hero.

‘We should all be proud of Erdoğan, he’s a son of Kasımpaşa!’ he told me. ‘He’s still one of us. I know him well and I don’t feel he’s changed at all.’

He paused, thought a little, and then added a brutally honest and very Turkish appendix:

‘Well, OK – he’s tired and old, so he’s getting bags under his eyes. But otherwise, I have only positive things to say!’

How does he do it, this grumpy old man in an ill-fitting suit? It is a question I have often asked myself as I travel around Turkey talking to his faithful. Usually I get the sense of a demographic who feel their time, and their man, has come. For decades Turkey’s poor, conservative voters found they could participate in democracy, as long as they did not threaten the order. When the politicians they elected looked as though they might actually change things in the way their supporters had been yearning for, the army – self-appointed guardians of Atatürk’s secularity – stepped in to overrule them.

Yet that is only half the story. Alongside the women banned from universities and the public sector because they wear the headscarf, and the men who long yearned for a politician who prays and abstains from booze just as they do, there are others who you would never expect to support Erdoğan – yet they do. Over lunch on a waterside terrace one afternoon, a blonde, wine-drinking academic who grew up in the UK spoke openly about the things that irk her about Erdoğan. Single, secular and childless, she said she felt personally offended when the president had described women like her as incomplete, his latest in a series of bullish statements alienating anyone less pious than he is. Ultimately, though, she – like his other supporters – let him off the hook. When I asked her why the most powerful man in Turkey appeared so sensitive, so petulant and so undiplomatic, she threw back her glamorous coiffed head and laughed: ‘Because he’s a Pisces.’

What is the root of his appeal in these unexpected quarters? One secular, Western-educated journalist told me that she has two great political heroes – Erdoğan and Margaret Thatcher. She sees the same traits in both of them – a tireless work ethic, and a single-minded belief that their way of doing things is the right way, and screw all the haters. She also admires the way that both were self-made, people who had started from modest backgrounds and clawed their way to the top. Others, even if they do not admire him, can appreciate the way Erdoğan has broken the grip that the Kemalists, the devotees of Atatürk, kept on the country for decades.

It is easy, now that they are the underdogs, to romanticise Turkey’s secularists, and to imagine that all would be right with the country if only they could seize back power. But those who remember the secular glory days know they could be as despotic as any religious regime. The dogmatic banning of headscarved women from higher education and from working in the public sector after the coup of 1980 confined millions to a life of child raising and housework – ironic, given Atatürk’s outspoken feminism. Atatürk pushed his own bizarre law banning the fez, the iconic, tasselled, brimless red felt hat ubiquitous in the later Ottoman Empire. This decision sparked a ‘Hat Revolution’ on the part of stubborn fez-wearers in the conservative eastern city of Erzurum that was crushed by Atatürk’s military, thirteen of the ringleaders being executed.

Though Atatürk may not have wished for it, the self-appointed keepers of his legacy – who for decades dominated the courts, the universities and, most notably, the army – stamped down on anyone who stood in the way of their mission. And if you find yourself in eastern Turkey and talk to the Kurds, you’re unlikely to find many Atatürk fans – for it was he who ordered their cities bombed when they revolted against his Turkish national project. Even today, in the Kurdish regions, the Atatürk statues seem a little bigger, a little more brash: visual slaps to the descendants of those who died at the hands of their own government. The plaques engraved with one of his most famous sayings – ‘How happy is the one who says, I am a Turk’ – seem to be there simply to mock the Kurds. The first Turkish president to apologise for what happened in the 1930s? Erdoğan. It’s odd, now that Erdoğan is waging his own war against Kurdish radicalism.

‘You see the look the Erdoğan people have in their eyes now? That conviction that they know the ultimate truth? Well, that is exactly the same look as the Kemalists used to have,’ said one Turk who remembered very well. Half of his family, a bunch of outspoken leftist intellectuals, were imprisoned following the 1980 coup.

Here is another way of looking at Erdoğan’s success: lucky timing. Erdoğan is not the first politician with ambitions to take Turkey in a new direction, he is just the latest in a line of leaders who have professed their piety, and their opposition to the old order. The support base has always been there. Atatürk never fully, or even mostly, achieved his ambition of making Turkey a truly secular country. And Erdoğan’s demographic is growing more rapidly than Atatürk’s – put crudely, the poor and the religious tend to have more children. Meanwhile, the opposition screams foul at Erdoğan’s plans to grant citizenship to around one in ten of the three million Syrians who have settled in Turkey after fleeing their own country’s civil war. They are convinced he is only doing so to reap their votes in the future.

But what differentiates Erdoğan from his ideological predecessors is how he managed to gather support from those outside his base – social liberals, supporters of globalisation and free trade, opponents of military tutelage – before going on to crush those very same people. The irony was not lost on Amnesty International, who – as Erdoğan intensified his post-coup jailing of opposition journalists in 2016 – wrote an open letter reminding him that they had once stepped in on his behalf when, in 1999, he was imprisoned for reading a religious poem at a rally.

Since Atatürk died in 1938, Turkey has been like a round-bottomed toy that rocks precariously to one side or the other but always returns upright. The opposing pull of the country’s two major forces have always brought it back to a central position – though Erdoğan’s charisma, political skill and good timing might now have upset the balance.

Even amid a purge that has stripped tens of thousands of their freedom and livelihoods, those who are not charmed by Erdoğan can still fall prey to his powers of persuasion. Once, as I was chatting to a man who was telling me how his company had recalled 200,000 T-shirts because they feared the design might offend the president, we came on to the subject of Europe – Erdoğan’s pet hate at the time.

‘But Europe lies!’ said the man, certainly no Erdoğan fan. ‘We have three million Syrian refugees and Europe gives us nothing!’

This was one of Erdoğan’s claims – that almost none of the money promised to Turkey by the European Union under a deal to stop asylum seekers surging across the Aegean had materialised. But it was rubbish. Over a period of eighteen months the EU had signed off on projects worth almost three billion euros, exactly what it had promised, with another three billion ready to hand over. European money was pouring into the Turkish health and education systems, refugee camps, asylum detention centres – and that was just one branch of funding. Billions were also being handed over in accession grants, the money given to countries that might one day be EU members to help them bring their standards up to European level. But Erdoğan had managed to convince his people that Turkey was being screwed by Brussels. Erdoğan’s lies are not a web, they are a paste that he slathers on so thick that nothing of the truth underneath is left showing. His motivations for doing so are clear.

‘Look,’ he is telling his fellow Turks. ‘You may not like me, but I am saving our honour against those who would seek to destroy it.’

It is a well-tested method. Part of Atatürk’s appeal, after all, lies in the fact that he rescued Turkey from nefarious foreign powers almost a century ago. Maybe these two cults share more similarities than either would care to admit.