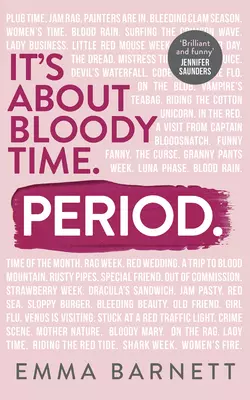

Period.

Period.

Emma Barnett

The fierce and funny manifesto from broadcaster Emma Barnett.Myth-debunking and taboo-busting, this is going to be the book that everyone is talking about. Period.At a time when women around the world are raising their voices in the fight for equality, there is still one taboo where there remains a deafening silence: periods.Period. will be an agenda-setting manifesto to remove the stigma and myths continuing to surround the female body.Bold, unapologetic and a crusade to ignite conversation, this is a book for every woman – and man – everywhere.

Copyright (#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ,

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Emma Barnett 2019

Emma Barnett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

Droplet image © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008308070

Ebook Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008308094

Version: 2019-08-23

Dedication (#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

For my two boys –

the best team I could wish for

Contents

Cover (#ub3a02245-ece2-57f8-b33a-6fb8345d3c03)

Title Page (#u146deff9-7259-5660-abe5-c4028f0d22e4)

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction:

FRESH BLOOD (#u85f2c13a-317d-5b1a-832f-576e1e6411fd)

Chapter One:

FIRST BLOOD (#u81166149-6fab-5cfd-a172-42a16101b1bb)

Chapter Two:

HOLY BLOOD (#u44b75ae0-dcbf-5115-bc20-da952b0bfef1)

Chapter Three:

BAD BLOOD (#u25c59003-897c-5086-98b3-ab1bc4c7e4b0)

Chapter Four:

MAN BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five:

OFFICE BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six:

CLASSROOM BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven:

POLITICAL BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight:

POOR BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine:

RICH BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten:

SEX BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven:

WANTED AND UNWANTED BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve:

NO BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Conclusion:

LAST BLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

PERIOD PRIDE MANIFESTO

RIDING THE COTTON UNICORN:

a handy appendix of period euphemisms (#litres_trial_promo)

A LONG OVERDUE LETTER TO MY PERIOD

Acknowledgements

Praise for Period. (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

About the Publisher

(#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

‘Women have been trained to speak softly and carry a lipstick. Those days are over.’

Bella Abzug better known as ‘Battling Bella’, lawyer, activist and a leader of the US Women’s Movement

I loathe my period. Really, I do. I cannot wait for the day it buggers off. For good. But shall I tell you what I loathe even more? Not being able to talk about it. Freely, funnily and honestly. Without women and men wrinkling their noses in disgust as if I’d just pulled my tampon out, swung it in their face and offered it as an hors d’oeuvre.

Don’t get me wrong – I am grateful to my period too. A functioning menstrual cycle is, after all, one half of the reason we are all here in the first place and able to procreate, should we wish to. I may loathe the physical experience of my period but that doesn’t mean I can’t and won’t fight for the right to converse about it without fear of embarrassed sniggers.

Periods really do lay serious claim to the label ‘final taboo’. But why, in the twenty-first century, are they still seen as disgusting and something a woman should endure peacefully, without fuss? This is despite most other ‘off-limits topics’ losing their stigmas and coming into the light, helpfully driven by Generation Overshare. But the sight or sound of blood in pants? Don’t be daft.

Most women don’t even want to talk about them with each other – because there is a deeply rooted idea they are a silent cross to bear, are vile and don’t merit anything more than a passing mention.

From their very first bleed, this occurrence in women’s pants has been treated by most people around them (female and male) as something to be quietly experienced and hidden away. Periods still have a whiff of Victorian England about them; a stiff upper lip is expected when it comes to what’s really going on down below. And women have become so adroit at sparing men’s blushes and shaming each other that they have either wittingly or unwittingly denied themselves the chance to talk about their periods, becoming weirdly active participants in the great global hush-up.

Yet, through my journalism and extremely painful personal experience over the last five years, it slowly started to dawn on me that, although on the surface there is a reticence to discuss periods, there’s actually a shy hunger to do so underneath, which, when prodded, gives way to some of the most extraordinary tales.

Periods have literally followed me around my whole life. I found myself to be one of the few schoolgirls happy to chat about the red stuff – a taboo I continued to enjoy breaking as I headed into adulthood – much to the chagrin and bemusement of those around me. Little did I know I would become the first person in the UK to announce they were menstruating on live television news; that my undiagnosed period condition – endometriosis – would nearly cost me my chance at motherhood; and that I would be secretly shooting up hormones ahead of one of the biggest political interviews of my career. I hope that on these pages I can bring these narratives together, make some sense of them, and crucially offer some hope, solace and wisdom to women about their periods – served up with a healthy dollop of humour and honesty.

The silence and public attitudes towards periods hold women back – often without us realising it.

Unlike pregnancy and childbirth, periods, the only other bodily process reserved exclusively for women, present no ostensible upside for the male species. Men get nada out of our periods (except, you know, the future of mankind secured).

Plus, if we can’t bring ourselves to think our periods merit anything more than a passing lame joke or occasional grumble, it doesn’t require a huge leap of imagination to figure out how many men feel about them, if they consider them at all. Horrified. Appalled. Almost insulted. Even the most enlightened man would probably prefer for women to deal with them without breathing a word. And can you blame them? Most of us do everything we can to hide the horror in our knickers, even struggling to talk about periods amongst ourselves.

Men are never going to be the ones leading the charge to stop periods being treated as gross, difficult events. It’s down to us women to proudly step out of the shadows and not give two hoots about what men think. It’s not going to be easy, and women have to get used to not being everyone’s cup of tea. We must ignore the men – and women – who would rather we stayed quiet and ‘ladylike’ about our periods.

Women censoring themselves from talking about their periods is the final hangover from a time which demanded that we should be seen and not heard; always happy and never complaining; pure and never sullied. It’s ludicrous that women remain slightly horrified by something so natural. These women are actively impeding their own ascent to equality with men, for whom nothing is off limits. Yes, women living in Western countries have equality enshrined in the law and yet, we still aren’t fully equal. No longer are we confined to a special biblical red tent; we’re in your boardrooms, your armoured tanks and we’re even running a few countries. But we still aren’t equal to men in terms of power, public office and, most damagingly, the way we are perceived.

By allowing periods to remain a taboo, women are imprisoning themselves. Even more worryingly, it’s contagious. Girls (and boys) already suffer with low self-esteem and that’s only getting worse in the social media era. When it comes to simple bodily functions, the least we can do is remove a stigma that has damaging consequences on half of the world’s population. Many women already judge themselves to be less than men or suffer with imposter syndrome. If we then conceal something that happens one week of every month (often longer) we are unconsciously turning our periods into a form of disability, as well as failing to confront negative myths and damaging how we view ourselves.

The bogus presumptions about menstruating women are tragically still not confined to the history books – namely that we are weak, dirty, unhinged, less than and just different. At the heart of this lingering stigma is the idea that we are unequal to our male counterparts. Women then ingest these views and appropriate them as our own, inflicting wounds on ourselves and other women around us. And by keeping periods unmentionable, women become unwitting accomplices in perpetuating these myths.

No more I tell thee, dear reader.

Period shame has been stubbornly hanging around since the beginning of womankind and it’s about bloody time for change.

Because if there’s one thing we do know, it’s that a period waits for no woman, so let’s finally allow the period pride to flow.

To be clear, I am not saying women feeling better and bolder about their periods is a secret key to unlocking the door to full equality – if only. It won’t stop at least two women a week dying at the hands of a man in the UK, or suddenly catapult a woman into the White House (as the incumbent, and not the wife who picks out new china and curtains). I’m not naive; nor do I wish to overplay one element of our lives.

But the way periods stubbornly remain taboo, along with all other things we hide with shame and fear, is highly symptomatic of how women have been indoctrinated to believe that a perfectly natural bodily function is totally abnormal. It is this attitude, which too many women, men, religious figures and tampon companies propagate, that ensures we remain ashamed of one of the fundamental signs of womanhood at all ages and stages of life.

Women fear being seen as weak in the workplace, so say nothing about menstruation and any issues they might be having, tacitly reinforcing a view that we are less capable during our time of the month.

Schoolgirls in Britain are missing out on their education because their families cannot afford to buy tampons or pads. Period shame stops them asking for help or admitting why they are skipping school. The same is true of fully grown women who can’t afford pads. They stay in their homes, imprisoned by the fear of someone noticing they are unwillingly leaking through their makeshift sanitary pad (sometimes it’s a sock, other times, loo roll). Nobody knows so nobody helps. A totally unnecessary cycle of period poverty remains unbroken and wreaks havoc. In the UK, the world’s fifth largest economy. Right now.

If we don’t start talking openly about these issues, these perceptions will go unchallenged for yet another generation. Periods should be as natural and as unremarkable as waking up with a headache or needing to pee. And until they are, women and girls will remain relegated – different and unequal within our very selves.

Simply put, periods shouldn’t be seen as a source of shame. Instead a period should be seen as a sign of health, potential fecundity, strength and general bad-assery.

Don’t be revolted, lead the revolt – preferably with a grin on your face and a tampon tucked proudly behind your ear.

There’s nothing else for it. You didn’t realise it and neither did I until recently – but we need a period crusade. For our health, our happiness, and because this bizarre taboo is holding women back.

This book, and the stories within it, is for all women, and not just for the minority who are already comfortable shouting about every part of their existence. But it’s also for men who want to understand what’s really going on in the lives of the women and girls they care about.

My aim is to normalise every aspect of periods, to mention the unmentionable and help you notice things you’ve never considered before. And crucially, to make you laugh along the way. Women, it turns out, can be extremely funny about blood. Periods can be a subject worthy of mirth. Who’d have thought it?

I spotted my personal favourite comment on menstruation upon an e-card, which read: ‘Why periods? Why can’t Mother Nature just text me and be like, “Whaddup, girl? You ain’t pregnant. Have a great week. Talk to ya next month.”’

Ultimately, I’d love to instil within you, my wise, merry readers, a sense of period pride, perspective and some flipping normalcy around menstruation. Because unless we change the way we talk about periods, this silence and shame is here to stay.

So, as my Eastern European pal used to sardonically say each month: the Red Army has arrived.

But the big question is: are you with me?

CHAPTER ONE (#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

(#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

‘Girls are superheroes. Who else could bleed for a week and not die?’

(A very true internet meme)

All women remember their first period. Where it happened; who they were with; what raced through their mind and what they did about it. Or didn’t. The sight of blood anywhere is frightening. In your pants, it’s terrifying.

I want to share the story of my first period with you for two reasons. One – quite frankly it would feel rude not to in a book about the red stuff. Two – my mum’s reaction goes some way to explaining why period pride came quite naturally to me.

But even though I have felt pretty confident about busting the period taboo at each stage of my life, to my horror I still utterly failed to achieve a diagnosis for a serious period condition ravaging my insides for more than two decades. I wish to open up to you about this particularly agonising chapter of my life to show that even if you have never spoken about periods aloud before – yours or someone else’s – you can start now. And you should.

Apart from kicking off a much needed cultural shift around the silence that engulfs periods, it was only when I admitted to a friend how much pain I was in each month, that she suggested I might have a proper illness, which prompted me to push for a GP referral to a specialist. More women need to be heard to be believed. And only by talking more about our periods, can we learn what’s normal and what isn’t – and that actually, we’re bleeding superheroes.

I started my period just shy of my eleventh birthday in a cold toilet cubicle in Manchester’s House of Fraser. As I was an only child with a devoted mother, who delighted in my every milestone, I shouted out to her from the cubicle that there was something browny-red in my knickers. She told me, breathlessly, that I had indeed ‘become a woman’ and started my period. I’d just started reading Judy Blume books and had a vague idea this was a good but major thing. And then she left. In a panic. Off she ran around the whole shop floor telling anyone and everyone her little girl was having her first bleed and asking around for a spare pad. Subtle. A few minutes later, I opened the door and watched as she gently stuck a large pad down into my stained pants. Her excitement was infectious.

I remember feeling like I’d done something positive and exceedingly grown up. And when we walked out of the loo, I recall bashfully taking in the smiling faces of the female shop floor staff, as if I’d just won gold in the Woman Olympics. I now know my lovely mum was trying to make up for how her own mother had reacted to her first period. My mother was told, in the swinging sixties no less, that she was ill and put to bed. No explanation was given, but it became clear that it was a subject that was off limits for discussion – the final irony being that her father was a doctor! It was a terribly confusing, scary and negative experience for her.

Mine couldn’t have been more different. On the day of my first period – over a celebratory steaming hot chocolate – as my mum delivered a basic explanation of what had just occurred (something along the lines of ‘this will happen every month and welcome to the woman club’), she was beaming and almost crying with pride. I was excited, but I also remember asking her not to tell my father. I’m not sure why I wanted to keep it from him but it was probably because it concerned something dirty in my pants to do with my vagina and he didn’t have one.

Without even realising it, I was already hard-wired to protect the man in my life from potential female grossness.

Either way, when we got home, she swiftly reneged on our agreement. In fact, we hadn’t even taken our coats off before she proudly told him that I had Become a Woman. Any feelings of anger I had at her big mouth were swiftly cancelled out by his understated but lovely response. Probably a touch confused as to what to say, he sweetly wished me mazel tov (like you do as a northern Jewish father who doesn’t speak that much), and swiftly went back to reading his Manchester Evening News. And that was that.

Except it wasn’t. Life had changed and my first period lasted for nearly three weeks. I don’t remember the pain with that one – that was to come later and to define my whole experience of periods. But the discomfort of large nappy style pads in those long first three weeks still looms large in the mind.

I dimly recall telling a few friends at school ‘I had started’, but I was one of the first to get my flow, so it was only a small number of girls who knew what I was talking about. It was to take one of my closest friends a further four years to get her period so she was oddly quite jealous. Consequently, it didn’t feel right to complain to her about my need to shift my heavy knickers about in a distinctly unladylike way in class, trying to get my new massive nappy into a comfy position and stop the adhesive underside from sticking to my legs. Mum hadn’t really catered for small knickers in her choice of sani pad.

My main period chat was with my mum during this first flow, as she inspected my pad and asked how I had felt before and after school every day of my biblically long bleed. And because of this regular checking in (during which my doctor grandfather was also consulted on the phone as I entered my third week, and I was breezily assured all was well), my first experience, unlike so many women’s, felt OK. Cool even. Mum and I made some daft jokes and I definitely got some extra chocolate. Periods were made to feel like a new inconvenience, but one I could totally handle. Yet so many girls suffer in ignorance and silence during their first period, establishing an embarrassment they carry for the rest of their lives.

My period was also on the conversational menu at school if I wanted it to be. My girls-only school – Manchester High School for Girls, where Emmeline Pankhurst sent her strong-willed daughters – may not have given any of us the full biological low down until we were a bit older, but the largely female staff were always receptive to chats about the red stuff. (Especially the sceptical swimming teachers who listened to our tales of gore, fake and real, as we soon learned the quickest way to dodge the icy school pool was by saying we ‘had a really heavy period’. Finally, a benefit!)

Soon, though, this was a reality for me. After my relatively pain-free maiden bleed, my period quickly became a much darker experience. Clots and crippling cramps were my new norm and I found myself wincing in pain for the first two days of every cycle. My mum, who I soon learned also suffered painful heavy bleeds and was upset that history was repeating itself, was swiftly on the case.

Interestingly, I felt I could openly confide my fears to my mum but I didn’t feel I could, or should, talk about it with most of my friends – and not just because some girls were jealous, I now realise. Whilst I was prescribed contact lenses at a similar age, it felt like something I could openly bitch and moan about, no matter how insecure I felt. My period, not so much. Even when I rushed to the school loos in crippling pain, and tried to explain why to my peers, their blushing cheeks meant that I was already being socialised to keep quiet about my period. If this is what it’s like in a girls-only environment, is it any wonder that we’ve all stayed silent for so long? And I didn’t even get teased by horny pre-pubescent boys about smelling or being frigid because I was ‘on the blob’ – unlike the experiences of so many girls I know who had brothers or went to mixed schools.

Around my twelfth birthday, when the monthly pains really set in, I spoke up again to my mum, refusing to believe my debilitating experience was normal and was swiftly taken to the GP who prescribed strong period-specific painkillers called mefenamic acid. I have vivid memories of both parents soothing me, as I writhed around in my bed and found myself with the runs, hobbling to the loo (yet another side-effect of periods that remains a taboo subject).

The point is, I had the period confidence to do this and suffer openly (at home at least).

I was made to feel proud on the day I bled for the first time, rather than dirty and ashamed.

Periods weren’t taboo with the few adults in my immediate daily life. I realise now, in my early thirties, how enlightened and important that reaction was. Another friend’s parents broke out into a congratulatory song in front of her brother and his pal, when she started. While she was mortified, just as I would be (not because of the subject but actually because I loathe spontaneous group singing) it also instilled within her a sense of happiness and achievement on her first period day.

I was always encouraged to talk about my feelings – something which has stood me in good stead for becoming a broadcaster. But that doesn’t mean my friends and I fully understood our periods, as evidenced by our rather disastrous attempt to help a girl insert her first tampon aged sixteen on a school trip. More of that to come …

However, the open attitudes both at home and in my schooling, and being encouraged from an early age to challenge boys at every opportunity – especially on the school bus when ‘banter’ was at the girls’ expense and was often regarding matters of puberty – led to me possessing something so few women and girls have: period pride.

I mentioned it in the previous chapter. But stop for a moment to consider the phrase. It consists of two words you don’t often associate with one another – let alone see written down together. And that’s what I would really like to inspire in you. I want to infect more women with period pride and, in turn, cure men of their need to retch when the topic arises.

Period pride doesn’t mean you have to enjoy your period. I certainly never do. My periods have been defined by bone-grinding pain; I have never been one of those women who breezed through their monthly bleed. It wasn’t something I felt I could or should ever ignore.

At school, I didn’t talk about my period much, though I found it odd that no one else was screaming about this strange monthly occurrence. The only place I found any more information about it was within the comforting pages of Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, in which the protagonist begs God for her period to come so she can be normal. Incidentally, this tome is one of the most challenged and banned books from US children’s libraries – make of that what you will. ‘Put up and shut up,’ was the vibe around periods.

Once our paltry sex education kicked in when I was around 13 or 14, they were only spoken of in the truest biological sense. No mention was made of our hormones, moods or other parts of our bodies and mind. The tone was also rather glum, portraying it all as a bloody cross to bear rather than something faintly ludicrous, or an experience to exalt in any way. Had just one teacher broken ranks to tell us her worst leak story, we might have at least enjoyed a giggle at our shared shedding of innards.

Unfortunately, there was not that kind of female solidarity at my school, nor really thereafter, but that didn’t dent my natural period pride. In fact, I became even less meek about occasionally busting out some of my period’s greatest hits to my appalled male and female university housemates and, later, to my closest pals and colleagues. Even now, my husband, despite often being a better feminist than me, still occasionally wrinkles his nose in squeamish disgust.

My openness about my period is why I found it uncontroversial, perhaps weirdly easy in fact, when I made a spot of broadcasting history on 19 May 2016. You see, I am the first person, certainly in the UK, to look down the barrel of a camera lens on a popular 24-hour news channel and unashamedly utter the words: ‘I’m menstruating, right now.’

The TV programme? The Pledge, a free-talking evening panel debate show I used to co-present on Sky News. The reason? I wanted to debate menstrual leave in the workplace. And the panel? Duly horrified.

The subject was in the news that week because a small Bristol-based company, aptly called Coexist, had become the first in the country to introduce a ‘period policy’ in a bid to help its large female workforce be more productive. Practically, this meant employees could take time away from the office around their menstrual cycles and work more flexibly at that time of the month, instead of – as the boss put it – being hunched over their desks in pain.

Menstrual leave is a common policy across large parts of Asia but has yet to catch on as a Western phenomenon and I had very mixed views about it. While I applauded the concept of breaking the taboo around periods, and giving women the option to work more flexibly during heavy or difficult bleeds, I also loathed the idea of periods being weaponised against women as a badge of weakness in the workplace. Or, that it could become a fashionable policy, writing off our periods like some politically-correct fad, something that is simply a ‘hot topic of the moment’ only then to be forgotten and glossed over.

I soon realised I could use my lack of squeamishness about my own periods to great effect. I had the chance to kick off a real debate and duly wrote my autocue script with a wry smile on my face, knowing it would get a reaction. My wonderful producer, always encouraging of anything that would enliven our conversations, was thrilled, almost titillated. I was happily putting myself out there, the subject was fresh, and she knew it would expose divisions in our diverse panel about a genuinely controversial issue.

Usually we rehearsed our opening statements in front of each other before recording, but for this topic, we decided I should do it on my own, to keep it fresh. The hilarious thing was that everyone apart from me – the camera crew, the producers in the gallery and the editor – were jittery and on tenterhooks about my big reveal. Especially as one of my co-hosts was my faux adversary, the masterful broadcaster Nick Ferrari. Off air, I love Nick and he is a very good pal, but on air we pretty much disagree about everything, especially gender issues. It was a subject that had the potential to generate fireworks and Nick certainly didn’t disappoint. From the minute, I began describing my painful clotting flow, he slowly lowered his head into his hands, muttering: ‘Why, oh, why did we need to talk about this, Emma?’

His cheeks were bright red and he looked like he might vomit.

He wasn’t alone. Both my female and male colleagues – including journalist Rachel Johnson and international footballer Graeme Le Saux – were howling with shock and dismay. Intelligent adults howling on national TV. They didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. But, because I’m a good humoured kinda’ gal, wanted a proper debate and loved my fellow Pledgers, I swiftly helped my colleagues through the shock of ‘Woman Admits Period on Live TV’ and attempted to move them on to the issues at hand.

The irony was of course that, by attempting to lead by example and not be ashamed of talking about my own period, we never really fleshed out the debate. I was genuinely trying to start a conversation about whether menstrual leave was an appropriate response by company bosses, or whether it was a policy ripe for enforcing the age-old idea of women as the weaker, less capable sex. Instead, the laughter-filled conversation became more about why I felt it was necessary to make a big deal of periods. Put simply, my co-panellists couldn’t make it past the fact that I’d mentioned my own pulsating uterus on TV.

But what was even more striking was that the reaction of my female panellists was just as strong as the men – they too argued that this cone of silence should continue. I ended up feeling terribly alone, as their shock – and I believe, embarrassment – drove them to giggle and sneer about the whole discussion. Trust me, this isn’t a group who shock easily, but they couldn’t get over the fact that periods were being discussed out loud, on TV. And when other women aren’t setting the tone for men to follow, it’s hardly a surprise that my male co-hosts couldn’t bring themselves to go beyond some gentle scoffing and a few end-of-the-pier jokes.

Interestingly, once we were off air, one of the lovely female panellists said to me in the make-up room: ‘Perhaps I should have been a bit more supportive of you out there on second thoughts, but there we go.’ Rachel Johnson, one of the most open and outspoken journalists I know, had turned period pink with an uncharacteristic bashfulness, over something so natural.

Several weeks after the programme aired, I was thrilled to hear that one of the women in the editing gallery (often a male-dominated space) was suffering from particularly painful cramps, and when asked if she was OK, gruffly replied, ‘I’ve got what Emma talked about’.

I was also cheered by the reaction of viewers at home, with messages of support for my efforts pouring in on social media. Men revealed that their female partners never spoke to their colleagues about their discomfort. Women thanked me for my candour, realising how rare this kind of honest conversation was – and their response has stayed with me ever since.

A few months later, a woman stopped me in my local fruit and vegetable market, clutching at my arm with fervour that was slightly alarming. She was a lawyer and told me that she’d seen The Pledge episode – it had been a lightbulb moment for her. Close to tears, she recounted how her heavy period had flooded on the bus on the way to work one time. Ashamed and panicked, she’d desperately scrubbed and dried her suit in a coffee shop loo in case her colleagues noticed. Sadly, it wasn’t an isolated incident and she was diagnosed with fibroids – her monthly downpours forced her to quit her full-time job, turning her into a part-time shift-worker so that she could manage her working life around her cycle. She’d never spoken about this to anyone and wanted to thank me for speaking out about periods without shame – it was this that had really struck her, how simply I had admitted I was menstruating and in pain on national TV.

It was like I had started to unleash something people hadn’t known needed releasing: the shy hunger to talk about periods. It dawned on me that enabling others find their voice on periods and engaging in this forbidden conversation could be an important step in helping women stop judging and shaming themselves in all walks of life. Stories of pain, shame and hilarity have followed me around ever since.

Sitting in that glamorous, shiny-floored studio, what I didn’t realise was that I was about to be diagnosed with endometriosis – a common but often poorly diagnosed menstrual condition (where tissue similar to the lining of the womb starts to grow in other places, such as the ovaries and fallopian tubes) that causes millions, yes, millions, of women colossal amounts of bone-grinding pain every month and can have serious consequences for fertility. It turns out those painful early periods I’d had weren’t normal or acceptable. Me, the one with the big mouth and period pride, actually had a proper period illness all along. One I’d never heard of, couldn’t spell nor explain.

I soon underwent the most painful forty-eight hours of my life, as a surgeon lasered my insides for nearly three hours. Although it’s estimated at least one in ten women in the UK have endo (as it’s called by those in the painful know), it takes a scandalous seven and half years on average to be diagnosed with this progressive illness. It took me nearly twenty-one years to get my diagnosis – and even that came down to pure luck.

By chance, I’d opened up about the pain I was in every month to a doctor mate over Sunday brunch, and she’d tentatively suggested that endometriosis might be a possibility. I’d had over two decades of medical appointments in which I complained repeatedly of severe menstrual pain, but I’d still failed to convince my doctors to take my period pain seriously. I’m someone who thrives on bashing down doors and demands answers for a living, yet I still hadn’t got anywhere – so what hope was there for others?

To be frank, I am fucking furious that nobody knows what causes endometriosis – mainly because it’s a ‘woman problem’ and there hasn’t been enough investment in scientific research. And people, even gobby folk like me, walk around ignorantly ill because no one takes our complaints of abnormal pain seriously, so we just stop talking, afraid of looking like we’re moaning.

As I hobbled around for three months recovering from my debilitating op, I felt as if the rug had been pulled from beneath me. But it meant that periods were back at the top of my personal news agenda, and I felt bloody foolish.

Back at work and intrigued by the silence and ignorance surrounding our periods, my team then commissioned a study for my radio show. Over 57 per cent of women who told us they had period pain (which was 91 per cent of the total number of women polled), admitted it affected their ability to work. But only 27 per cent of them told their employer the real reason they felt poorly, with most preferring to lie, often opting to say they had stomach problems. Interestingly, many British women were open to the idea of menstrual leave.

Before presenting the findings in our programme that day, I was invited onto BBC Breakfast to discuss the results – an invitation I happily accepted. Here’s how The Sun decided to write up my calm and measured conversation with my BBC colleagues: ‘Woman Sparks Furious Debate About Menstrual Leave on BBC Breakfast – BBC Radio 5 Live’s Emma Barnett Has Sparked a Sexism Row.’

Now who’s hysterical eh? And people still wonder why women lie about their periods, preferring to tell their bosses (of both genders) they have the shits. Go figure.

Periods need to come out of the darkness because of the potential benefits to women’s health around the world. But the cultural benefits of smashing the period taboo would be major and just as important.

Alisha Coleman, an American 911 phone operator, sued for alleged workplace discrimination after being sacked for leaking during two particularly heavy periods. Once, on her seat, for which she received a written warning, and then again on the office carpet. Can you imagine how mortified she felt? How you would feel? Perhaps you’ve been there too. Alisha was dismissed for failing to ‘practise high standards of personal hygiene and maintain a clean, neat appearance whilst on duty’ the lawsuit states. I am utterly dismayed that women can lose jobs over leaking on their office chairs.

‘I loved my job at the 911 call centre because I got to help people,’ Alisha, a mother of two, explained. ‘Every woman dreads getting period symptoms when they’re not expecting them, but I never thought I could be fired for it. Getting fired for an accidental period leak was humiliating. I don’t want any woman to have to go through what I did, so I’m fighting back.’

Quite.

But Alisha isn’t alone in struggling to conceal her period. One woman confessed to me, in the bespoke period confession booth built for my BBC 5 Live radio show, that she once had to call in sick because of severe period pain. She decided to the bite the bullet and be honest when she spoke to the HR director (who happened to be a man): ‘I could hear him on the phone being squeamish [when I told him the reason] and then he said, “Well let me know when you are fixed.”’ Fixed. As if she was a broken doll. I interviewed six other women that day, in their twenties, thirties, forties and fifties, and they all had their own coping mechanisms for making sure their period experiences remained as hush-hush as possible. You can understand why.

The very fact that my production team, who happened to be all women that day, had been delighted to build a beautiful confession booth (complete with a gold grill), spoke volumes about the need to have the conversation. The storytelling power of radio may be in its facelessness, which emboldens even the meekest guest, but we still felt the need to create a further physical divide to coax these successful and confident women (with the strict assurance of anonymity) into the box to talk about something as natural as their periods. Upon reflection, it was utterly ludicrous.

This censorship and secrecy that engulfs periods was highlighted by the global shock, teetering on outrage, when Kiran Gandhi decided to run the 2015 London Marathon free bleeding down her Lycra leggings. Kiran came on her period the night before and, deciding it would be uncomfortable to run 26 miles with a stick of cotton wool wedged up her genitals (you think?), chose to let it flow. Admirably, she also did it to raise awareness for poorer girls and women who don’t have access to period products. Whether it did that or not, I cannot say. But I do know many newspaper picture editors will have furrowed their brows as to whether they could run such a ‘distasteful’ image – despite it being all over the internet and the very same news outlets thinking nothing of filling their daily feeds with graphic images of bloody wars. You will hear more from Kiran a little later on.

Does that not strike you as terribly odd, now you stop to consider it? The fact that the sight of a woman’s menstrual blood, coming out of the hole it’s meant to, provokes more consternation than the image of lifeless children’s bodies being pulled out of the Mediterranean Sea in their failed fight to find a permanent home? One image can be published without question, while the other is censored, out of fear of poor taste and offence.

In China, tampons are still thought of as sexual items rather than basic sanitary goods. Caught short on holiday, when I asked a young female shop assistant in Beijing where the tampons were (whilst making unedifying finger gestures as I stood next to rows of sanitary pads), she looked at me like I was a strange slut.

There is still a fear, especially amongst younger Chinese girls, that tampons break the hymen. Recent figures show that only 2 per cent of the country’s women opt for tampons, compared to Europe’s 70 per cent. According to my friend and fellow journalist, Yuan Ren, Chinese medicine is also to blame for the cultural fear of tampons. It propagates the idea that putting a foreign object into the body is not good for you and can be harmful to girls who are still growing. Add this to the lack of education in the country as to how to insert a tampon and you have the perfect combination of factors to ensure that millions of women never experience the joy of a less cumbersome absorption method.

Instead, they have to waddle about with a cotton surfboard jammed between their legs. Lovely.

So why don’t we just say it how it really is? Periods are the blood of life and in many ways go to the very heart of being a woman. Simone de Beauvoir, when writing her seminal feminist text, The Second Sex, in 1949 wanted us to have jobs and work through them. She believed distraction from our pain was a good thing and the only way to cope. Germaine Greer, in her similarly iconic 1970 bestseller The Female Eunuch, famously wanted us to taste them as a test of our emancipation (full disclosure – I haven’t). She wrote: ‘If you think you are emancipated, you might consider the idea of tasting your own menstrual blood – if it makes you sick, you’ve a long way to go, baby.’

Periods, whether you are into tasting yours or ignoring it as best you can, are part of the essence of being female.

And yet we vilify them, disproportionately.

We know that men, particularly recent American presidents, have difficulty with them. But women also hush up other women on the topic, mainly out of fear that they will be seen as weak. Just because periods come out of our nether regions and, by their nature, are messy things, women worry this renders them worthy of censorship. But why? Is there just a horror and shame linked to blood in the pants? Granted, many men wouldn’t want to talk about their bleeding haemorrhoids. But they aren’t a normal monthly part of life and a vital sign of health. Quite the opposite. Or is it something that runs deeper and proves that women have bought into the age-old myth that anything uniquely female is filthy, reductive and not quite right. That we are broken and yucky in some way.

We can’t continue as a human race without periods – and yet we still can’t acknowledge their existence. In the twenty-first century. I am not calling for women to walk down the street in short skirts with their tampon strings dangling out, armed with megaphones screaming: ‘Look at us! We’re bleeding!’ (Although if you want to do that – go for your life, sister.) But what I do want is for this juvenile shaming attitude towards women and a vital part of our anatomy and health to stop being such an embarrassing mysterious and dirty secret.

Most women I know wouldn’t walk to the toilet in their office – a place they go every single day – without a dainty ‘special zip-up bag’ (ladies, you know what I’m talking about here) or even their whole handbag, just to take a tiny tampon into the loo for a change. Can you imagine if men bled for a week every month? Some form of menstrual leave would have been written into HR policies around the world, period-pain-bragging would be an Olympic sport and bleeding males would dramatically stagger to the office bog with their tampon proudly gripped in their fist. There would be no need to hide sanitary products in tiny zip-up bags. But men don’t have periods. And history has meant that they were the ones who designed society and the world of work without women – or our monthly downpours – in mind.

It’s time to perfect your period patter and swagger with pride, but it’s also important to know what you are up against: generations and generations of debilitating myths and anti-women, fear mongering nonsense.

Just as I began this chapter, that’s why it’s important to remember that ‘Girls are superheroes. Who else could bleed for a week and not die?’. I’ve got this. You’ve got this. We’ve got this.

Turn this page, turn a new leaf. Our work begins now.

CHAPTER TWO (#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

(#ua872c3b5-ce15-5e84-ab07-6b789ada9fae)

‘The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.’

Alice Walker, author and poet

Before I tell you how periods unexpectedly took centre stage in the run up to my wedding, I thought it first prudent to share a list of some of the codswallop that women on their period have been blamed for and prohibited from doing while menstruating.

Menstruating women must not:

Make mayonnaise as it will curdle

Come into contact with mirrors as they will cause them to dim

Walk through fields of courgettes, pumpkins or fruit trees – all will rot and wither

Contaminate butter as it won’t churn

Touch wine as it will turn to vinegar

Venture near dogs as they go crazy in the vicinity of period blood

Go camping or wild swimming – bears and sharks are drawn to the bleeding lady

Walk in front of anyone as their teeth will instantly break

Believe it or not, some of these nonsensical outright lies are still doing the rounds today. The teeth-breaking one? Still frighteningly alive and well in modern-day Malawi. The mayo gem? Still very much in rude health in Madagascar.

While we’d like to believe many of these myths – religious or otherwise – have died a death (along with believing women aren’t capable of doing loud smelly farts or pumping out logical thought), stories have a way of burrowing invisible roots deep into society. Even if there’s no basis for the prejudice or superstition, a grain of belief can still linger for a long time afterwards, colouring people’s views. So, although no doctors in the UK today believe that menstruating women could spoil meat, as some writing in the respectable British Medical Journal in 1878 did, there’s still a hangover from that type of ‘intellectual’ discussion which saw women as being ‘dirty’ during their period.

It is clear that religions haven’t been solely responsible for all period myths – doctors, tribe chiefs and the great thinkers of the day have all contributed their own bits of gibberish. However, all of the major faiths do still have a lot to answer for, as I found out to my surprise the year I got married.

I was born into a Jewish family, and brought up culturally Jewish – so, big Friday night dinners, a decent level of Jewish education until the age of twelve at Sunday school and attending my fair share of Bar Mitzvahs. And despite not being particularly religious or observant, the ideal romantic situation envisaged by my family was that I would eventually find a Jewish guy.

I always explain to people who struggle to understand why you might prefer to marry Jewish if you are Jewish but aren’t that religious, that it’s akin to wanting to marry someone from a similar background to you. That’s all. Someone who immediately gets your weird home rituals without explanation, understands your family’s quirks and with whom you have a shared history. But I should stress I probably would have also married outside of my faith too – because I believe in falling in love which is nigh on impossible to prescribe.

On a practical level, it’s really tough to find a Jewish mate, especially in the UK where there are now fewer than 250,000 of us in total, and the only part of the community which is growing in number is the ultra-orthodox. So, finding a Jew who is similar to you in terms of religiousness and outlook (as well as the million other ingredients that go into being compatible with someone) is tricky, especially as you’re shopping in a very small store. But, somehow, I did indeed land my match and amazingly, he happened to be Jewish. A lucky bonus for me.

When I met my husband, aged 20, I was wearing a blue Nottingham uni theatre T-shirt with my name emblazoned across the back (sexy, I know), because I’d recently been elected president and, before the journalism bug hit, I harboured dreams of acting and he was wearing stripy Birkenstocks. Also très sexy. I was in a flap and attempting to deal with a severe budget cut to the theatre’s meagre pot. Except my grasp of general maths, spreadsheets and deficits weren’t the greatest.

My fun-loving mate, Gemma, from my politics class I occasionally attended, had told me that her friend could help – plus, he was single, good at maths and HOT. Boldly, I introduced myself to him, and after some sexy budget chat in front of the theatre’s noticeboard I found myself complimenting his Birkenstocks and asking for his number, sober, in the cold light of day.

Long after that first encounter, he told me how bowled over he was by this forward northern woman demanding his digits. Fast forward through many dates, holidays, jobs and postal addresses, we are about to celebrate fourteen years together. And, even though it was daunting having met each other so young, at the peak of sowing our wild oats, we have stood the test of the time (even if the Birkenstocks haven’t). But why am I telling you how I met my husband? Because seven years on from that first meeting in front of the noticeboard, we were back there and something he did inadvertently led to us getting up close and personal with my period.

I’d been invited back to Nottingham University to give a lecture to politics students about how to get into the media. My other half had merrily tagged along. It was our first weekend back in the city since we graduated, and a little tipsy on red wine after a cosy dinner, I unwittingly set up my own wedding proposal. ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to stand in front of the noticeboard on the exact spot where we met?’ I asked, excitedly half running to the very point, with him smiling and walking behind me. Five minutes later, my then boyfriend was down on one knee asking me to marry him.

We decided to get married at a synagogue we’d recently discovered in London’s Bayswater, while renting locally. We had passed this beautiful building countless times, but being rather rubbish Jews had wrongly assumed it was a church. Finally, having made it inside on a random Saturday and been proven wrong, we fell in love with this Moorish-style temple and were charmed by the friendly local community and the brilliant rabbi, who was modern and amenable to our needs and religious crapness (my words, not his).

Someone in the community mentioned there were people who would happily give us the low down on Jewish marriage if we wanted to hear more about the experience. Always a sucker for learning and the chance to ask questions, I signed us up.

Now, if you were offered the chance to hear more about your faith and marriage ahead of your pending nuptials – what would you expect to learn? Perhaps some wisdom about love, sex, the wedding ceremony, family and being a single unit. I was hoping for tales of love in the Bible and to find out any kosher kissing tips (I jest. Slightly). My fiancé was just hoping to survive the experience. What percentage of that conversation would you expect to be about periods – a topic you’d never even really discussed at length or in any serious detail with your husband? 2 per cent, if that?

Well, 75 per cent of our informal session was about periods. My period to be precise. And how ‘impure’ it made me for nearly half of every month.

And that’s how my husband’s romantic university proposal ended up leading to one of the most memorable conversations I’ve had about my menstrual flow.

We barely had a chance to sit down upon meeting our informal guides, before the foreign concept of niddah was brought up.

Before my fiancé and I could exchange quizzical looks, I was invited to speak privately with the female volunteer. Finally, I thought, this was more like it. It was time for the good stuff in my girls-only chat.

Settling into a comfy sofa, the friendly woman began what has now become known in my friendship circle as ‘the legendary period talk’. Smiling at me, she said something along the lines of: ‘Emma, when you bleed each month, you become niddah. Impure. Unclean for your husband. And this lasts until the very last drop of blood has come out of you and you have cleansed your whole self in the mikveh pool. Do you understand?’

She then told me that, during this two-week window of time,

I was wasn’t even allowed to touch my husband’s sleeve, or, in my favourite example, pass him a piece of steak I’d cooked for his dinner.

As I was still digesting her words and mulling over how he was better at cooking steak than me, she began confiding the romantic and practical benefits of niddah. She told me that, like with anything in life, restraint makes something sweeter when you have it again after a while. Not touching for nearly two weeks every month meant you couldn’t wait to touch each other again, after the mikveh. And, handily, this would also be the right time in your cycle to get pregnant. Who’da thunk it? Plus, she confided, it’s sometimes nice to have a break from sex and your husband for half a month, every month.

My softly-spoken guide sat back, pleased with her explanation of how the Orthodox Jewish way had thought of everything. And while a small part of it seemed plausible (i.e. the part about abstinence making the sexual pull stronger), I felt as if I’d fallen down Alice’s rabbit hole and was struggling to re-emerge from Wonderland.

But the truly jaw-dropping revelation was yet to come. Before entering the mikveh pool – a pool which, I should add, you cannot enter with nail varnish on or even your hair plaited (a place my mother had religiously avoided her whole life) – I had to be completely sure that my period had finished. So how can you be 100 per cent sure, beyond your own eyes telling you that your tampon is clear and your pants are pristine?

A kosher rag.

Yes, you read that right. There is a special cloth you can buy to wipe yourself with so that you can double and triple check that your period has properly ended. But oh, no, no – that’s not all you can do to ensure your purity …

If at the end of your cycle, after you’ve wiped yourself with said specially blessed rag, you are still in doubt, you can post the scrap to your local rabbi in an envelope with your mobile number enclosed. After he’s inspected it, you will simply receive a text telling you whether you are kosher or not for swim time at the mikveh. According to my smiling guide, they are ‘specially trained’.

Yes, Jewish women are wiping themselves with and then posting bits of cloth to a bearded man down the road.

My own brazenness started to falter here, and I didn’t press any further. I have often wondered since about the identity of the first dude who figured he had the expertise to pass on this knowledge to all the other men who have never menstruated in their lives. I can’t recall much more from that session other than the moment my fiancé suddenly reappeared from his part of the house and swept me out of there. We both felt a bit sick – him from too many salty and sweet snacks, and me from a very odd period chat.

‘They do WHAT?’ was his general reaction, as I explained about the rabbi rag watch.

Meanwhile, in the other room, my fiancé had been given a more pared down version of how periods affect women, with a similar emphasis on ‘no touching’ during my ‘impure’ period. But I’ll never forget what else he had been told: ‘Women are a little crazy when they are on their periods’ – with the implication that, in fact, it was good for all husbands to have a break from their wives at this point in our monthly cycle. Yes, really.

(Later, in a totally unrelated conversation with a friend, I also discovered that women who are trying to fall pregnant can post vials of their period blood to clinics in Greece, who claim they can analyse the sample to spot potential fertility problems. It makes you wonder what other bizarre packages are being sent through the post, doesn’t it? Again, another rabbit hole.)

I must stress this: the people we met were kind and only trying to educate us in the ways of ultra-Orthodox Judaism. I don’t wish to be uncharitable towards them; my criticisms aren’t personal. And, of course, other folk could have sold this purity period-obsessed side of marriage to us in a softer way. Or not focused on it as much. But I am grateful for receiving an unvarnished insight into what one of the oldest religions in the world teaches couples about women, our bodies and purpose on this earth.

I know that some modern Orthodox Jewish women have reclaimed the mikveh as an empowering space for them to feel cleansed and almost reborn each month – but why is period purity even still a thing in the first place? A step forward in the dark isn’t a step forward to me. Teaching girls and women that they are dirty and in need of rebirth after something as perfectly natural as a period isn’t right, however it is spun.

Nor am I looking to solely point the figure at Judaism. God knows (and he really does), it’s a religion with enough haters already. Judaism is certainly not unique when it comes to the major world faiths pillorying or discriminating against women for menstruating. Far from it.

Factions of Islam believe women shouldn’t touch the Qur’an, pray or have sexual intercourse with their husbands while menstruating. Muslim women are similarly deemed impure and must be limited in terms of contaminating their faith or their men.

Catholics fare no better, but seem to prefer to whitewash the whole affair. According to Elissa Stein and Susan Kim’s book, Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation, when Pope Benedict visited Poland in 2006, TV bosses banned tampon adverts from the airwaves for the duration of his stay – in case his papal Excellency was grossed out.

Certain Buddhists still have placards outside temples that bleeding women shouldn’t enter. I recently saw such a sign outside a stunning temple in the heart of modern buzzing Hong Kong, of all places.

In Uganda, particular tribes still ban menstruating women from drinking cows’ milk because they could contaminate the entire herd. And in Nepal, right now, menstruating women and girls are relegated to thatched sheds outside the home and are prevented from visiting others, in a charming practice known as ‘Chapadi’, because it’s believed that a bleeding woman in contact with people or animals will cause illness and is just wrong.

Most Hindu temples also ban women from entering when they are bleeding. Some go further by banning women of menstruating age altogether. A particularly eye-opening case made headlines in India in 2018, when activists were successful in getting the country’s Supreme Court to overrule such a ban at one of Hinduism’s holiest temples. Historically, the Sabarimala temple has not allowed women between the ages of ten and fifty to attend because they could be menstruating and therefore will be unclean. Violent protests broke out at the temple after the ban was lifted, with many extremely angry men accusing the courts and politicians of trying to ‘destroy their culture and religion’ by allowing menstruating women access to what should be a peaceful place of prayer. Crowds tried to block any plucky female worshippers, female journalists were attacked and one of the women who tried to attend the temple ended up needing a police escort.

The saddest part of the whole unnecessary debacle? The number of women who attended the protest in support of their own ban. That’s how deep these myths can run. Women can be so convinced by men of their own filth that they turn on other women.

Devastatingly, Hindu girls and women also miss out on mourning their loved ones while menstruating because of this type of temple ban. Instead, they have to stay at home while the rest of the family pay their respects. Or, in the case of BBC journalist Megha Mohan, loiter outside the temple in Rameswaram (an island off the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu) as her family observed the final ritual for her grandmother.

While waiting, she recalls in a piece for the BBC News website, texting a female cousin, who couldn’t make it to the final ritual, to tell her about her aunt stopping her from going to temple as she had asked for a sanitary towel:

She sympathised with me and then she paused, typing for a few moments. ‘You shouldn’t have told them you were on your period,’ she wrote, finally. ‘They wouldn’t have known.’

‘Have you been to the temple on your period?’ I asked.

‘Most women our age have,’ she said casually and, contradicting my aunt’s earlier statement just half an hour earlier. She added, ‘It’s not that big a deal if no one knows.’

So, she could have just lied. And probably should have done to get her way.

Looking back further, Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote in AD 60 that having sex with a woman on her period during a solar eclipse could prove deadly.

Sure, mate. But this example shows just how long we have lived with this ritualised shaming of women.

Jump forward two millennia, back to London and my wedding lessons – it was so very odd to hear such backward advice still underpinning the way women are made to feel today. In the developed world, religion may not have the control it once had, but it’s still a huge cultural force that shapes norms and makes people feel a certain way about things.

Often, as with so many other day-to-day battles that make us weary, we can zone out when a religious teacher says something we would normally question. But keeping this shaming, impure narrative around periods going within our oldest religious institutions, despite leaps in medical advancements, at the very least has the subliminal effect of making women feel dirty and wrong.

And it reinforces the idea amongst men that our periods are something to fear and be sickened by.

So, question the nonsense when you happen to hear it. By all means laugh at it. Make sure you ridicule anyone who tells you that you are impure for your body doing something so natural that the entire human race depends on it. It isn’t easy. I failed to do so out of a mixture of shock and a fear of offending the kind people trying to prepare me for my wedding. And I still regret it.

You are a warrior – who bleeds and goes to work every day. Not some dirty hermit who deserves to be quarantined and needs male approval to be reintegrated into mainstream society after your monthly bleed.

Religion has no borders. It was viral before the internet. That is why a privileged educated woman like myself can be told, while living in one of the most advanced societies on earth, not to hand my husband a piece a steak I’ve made for him while menstruating. I am about as far away as you could get from a girl in Nepal banished to menstrual huts away from her home while she bleeds. And yet, we ended up getting a similar memo. Except I have the tools, power and voice to push back.

You see, without us realising it, these myths permeate, settle and erode confidences. Keep your antennae up and tuned. And have the confidence to belly laugh and challenge the shaming beliefs in religion.

Our periods hold the key to bringing the next generation of society into being. The least we can do is make sure we have the right attitudes towards them and diagnose any lingering bullshit from the days when only men had the power to tell the stories that narrated and controlled our destinies, regardless of whether they understood us or not.

Today, women control our bodies and our narrative.

We must not lose control of that hard-won right – especially over our periods – at a time when our voices are louder than ever before.

You can choose your reaction. That’s a power which must not be forgotten. Don’t internalise any of the shame these myths propagate. And remember to actively call out nonsense when you hear it.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_f2e36b50-74e3-5f05-8077-9f38b1631d01)

(#ulink_f2e36b50-74e3-5f05-8077-9f38b1631d01)

‘What if I forget to flush the toilet and there’s a tampon in there? And not like a cute, oh, it’s a tampon, it’s the last day. I’m talking like a crime scene tampon. Like Red Wedding, Game of Thrones, like a Quentin Tarantino Django, like, a real motherfucker of a tampon.’

Amy Schumer, Trainwreck

It’s time to focus on the group of people who are nearly as good as the men at period shaming.

Women.

It definitely isn’t our fault the way society is set up to be only horrified or titillated by women’s bodies. Nor is it our fault that we are the ones tasked with physically producing the next generation (the very reason for periods in the first place) – a role which tests our bodies and minds in all sorts of unacknowledged and undervalued ways.

But when you live and breathe in the bubble which normalises such attitudes, you internalise them and make them your own. Which means women end up feeling ashamed of a perfectly natural bodily process, often ignoring their bodies’ cries for help and, in turn, shaming other women too.

Remember the confession booth we built for my radio show? I’ll never forget the softly spoken woman in her twenties who poured this truth into my ear:

‘Periods suck. We women are complicit in the silence.’

She isn’t wrong. We are complicit. And such desire to stay silent about our monthly bleeds leads to all sorts of ludicrous scenarios and some very serious ones too, which I will come onto with my own near-miss situation.

But let’s start with an absurd tale, one which perfectly sums up how women can be their own worst enemies when it comes to making periods taboo.

I only inquire because one woman nearly did time in the can, simply because she couldn’t bear to confess she was menstruating.

Let me tell you about the Canadian performer, Jillian Welsh. She poured her heart out to producer Diane Wu on the hugely popular podcast This American Life about a bloody evening scorched onto her brain and has kindly given me permission to reproduce her story in this book, aptly signing off her note to me ‘yours in blood’ (I love her already). The episode was focused on romance and how rom com scripts would play out in real life. Or not, as the case may be.

Jillian was twenty and studying theatre in New York when she met and fell for Jeffrey, whom she was starring alongside in a Shakespeare production. Fast forward to the wrap party and the cast night out. One thing led to another, they kissed and ended up back at his place. So far, so good.

Except Jillian’s Aunt Flo was in town. Due to her highly conservative background she couldn’t bring herself to even say the word period, let alone tell her new beau that she couldn’t do the dirty because she was menstruating. But, finally, she fessed up – and guess what? He didn’t care. Excellent sexy time ensued, after which Jeffrey went for his postcoital wee and shower, flicking the light on as he exited bedroom stage left.

As Jillian recounted to This American Life:

It looks like a crime scene. There is blood everywhere. This is the first time I had seen so much of my own menstrual fluid. I was afraid of it. I couldn’t even fathom what he was going to think about it … And then I don’t know how this happened, but my very own red, bloody hand print is on his white wall … He didn’t have any water or anything in his room, so I used my own saliva to wipe the bloody hand print off of the wall, like, out, out, damn spot.

OK let’s pause there. It’s grim but not that grim. However, it gets worse. Deliciously so.

Jillian then decided the best strategy to deal with Jeffrey’s desecrated bedsheets was to stuff them into her rucksack, because she couldn’t bear the idea of him having to wash them. She then covered his bed with his throw and prepared to scarper as soon as he was back from his shower. She offered a lame excuse, he looked suitably hurt and off she trotted to the subway, upset and laden with stained, stolen sheets.

Then it really hits me that I have stolen this man’s sheets. How do you come back from that? How do you – how are you not the weird girl who took his bedsheets? … So then I’m so inside myself and I hear this voice being like, ‘Ma’am, excuse me, ma’am.’ And I look up. And in New York, they have this station outside of subway entrances with this folding table and the NYPD stands behind. And it’s a random bag search.

Let’s pause again. What would you do? I know for certain I’d brick myself as soon as I was aware I looked like a murderer on the underground.

Jillian also panicked and pretended not to hear the officers, playing that, ‘I am invisible game’ you enact as a kid when there is nowhere left to run and you just hope by praying hard enough no one can see you anymore. She left the subway with a quickening pace. But to no avail. The officer soon caught up with an increasingly suspicious looking Jillian, opened her rucksack and saw the fruits of her sexual labour: crusty blood-soaked sheets.

I remember him – and the subway has such distinct lighting – like I just remember him holding up these sheets, my menstrual sheets of shame, like menstrual sheets of doom. I realise that they didn’t look like menstrual sheets of doom, they looked like murder sheets of doom. He asked me to explain it, and I just start crying. And I can barely get the words out. I’m just trying to explain to him, it’s my period on those sheets. And I stole the sheets from the guy that I was with. And I know that that’s wrong.

Now, when I asked you if you would go to prison for your period, you might have laughed, but Jillian’s shame nearly led her down that road. Because, these two cops offered her an ultimatum: either go with them to the local police station, where they would file a report and ask her more questions, or take them (and the bedsheets) back to hot Jeffrey’s house to corroborate her story.

It is what Jillian confesses to This American Life next which I find so fascinating:

And I had to think about it … I honestly gave it a really solid, good think. There was a huge part of me that would rather go to the police station than have to go back and show Jeffrey these – not only show him these sheets, but also bring the police there. But, you know, my common sense caught up with me because this looks like I’ve done something very wrong.

Fortunately, Jeffrey, like the sexy period hero he is, when confronted by the cops, a nervous Jillian and the bloodied bedsheets on his doorstep, verified her story. Without skipping a beat, he simply explained that the sheets were covered with ‘menstrual fluid’. No shame. No juvenile euphemism.

Jillian, as you would expect, is by now a sobbing mess and in a line which could have come straight out of a Richard Curtis movie script, he calls her ‘wonderfully strange’.

Spoiler alert: if you’re interested in finding out whether their love affair worked out, it didn’t. Period night didn’t kill the relationship, it was actually American visa issues. But it’s not their love story that we’re focused on here, what I care about is that a woman – in one of the best first sex stories I’ve ever heard – was so ashamed of her period that she nearly chose a night in the police station over returning to the ‘scene of the crime’.

Take that in. It’s bonkers. Fully bonkers. But you know what’s even more crazy? Women the world over will understand why the police station inquisition was a serious option for a fully innocent Jillian because it seems we all have the propensity to become liars and weird little thieves when we get our periods. Anything to simply hide the evidence.

Take another woman I know, who also robbed some bedsheets. Jane was in her final year at school when she came on her period during a night out and didn’t have any tampons with her. She deployed ye olde faithful technique of stuffing one’s knickers with tissues and hoped for the best. Crashing at male mate’s family house for the evening, she woke up the following morning to her own crime scene spread across the bedsheets. Just because her friend was a guy, she felt she couldn’t talk to him about it. So, just like Jillian, she robbed the sheet, stuffed it into her handbag and then chucked it into a public bin on the way home. To this day, her mate’s mum still asks for her sheet back, and Jane is too embarrassed to tell her the truth.

Linen is never safe around a menstruating woman, but particularly, it seems, around a woman who is ashamed of her own blood.

We also become super sleuth laundry women. Another woman I know, now an accomplished doctor in America, had to steal and sneakily return a guy’s jeans so she could wash them:

My worst period story was probably in college, I had my period and needed to change my tampon but hadn’t yet – my then boyfriend came in to my dorm room and pulled me onto his lap … I’m sure you can see where this is going. I’m pretty sure I realised that I was sort of leaking through and then decided I just had to stay there forever. But eventually (obviously) I stood up and there was a real life Superbad moment AND I WANTED TO DIE. But actually, I just stole his jeans and immediately washed them, returned them and said nothing about it.

Truly horrifying.

You get the picture. Ludicrous behaviour abounds in women from all backgrounds and of all ages. All over some spilt blood.

And yet there is a serious level of irony that most young girls crave their first period, fretting about when they can join the ‘P-Club’ but spend the rest of their lives covering it up.

For one of my friends, this happened almost immediately. She’d just turned thirteen when her first period started, and her initial reaction was ‘BEHOLD ME, NOW I AM ALL WOMAN’. However, this was somewhat tempered by the fact that she was on a five-day school trip to the countryside and had to figure out how to climb down a rope frame without anyone realising she was bleeding (whilst simultaneously giving off the laid back, mature vibe of one who has just ‘become a woman’).

Crucially, I raise this mad urge towards concealment not because I think women should be talking about their periods all time, but because this culture can harm women’s health when they fail to seek diagnosis for menstrual conditions or gynaecological problems and furthers the stigma around periods – so it’s time to shine a glaring spotlight on this silence and our bloodied sheets.

Let’s take a step back for a minute and consider: what is the point of a period?

Other than the important business of reproducing, according to most doctors there is very little point. Galling, isn’t it?

Considering that this bleeding window in our lives is a relatively short amount of time – and only for those women who want or try to have babies – we are spending a heck of a lot of time and effort bleeding, when perhaps we don’t have to. (Not to mention the energy expended hiding this natural process from colleagues, friends and other halves.)

Dr Jane Dickson, the straight-talking vice president of the UK’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare tells me:

A woman is built around her reproductive cycles. She is set up as a pregnancy machine … A period is a natural, in-built preparation system for pregnancy. But in this day and age there is no reason a woman should have periods if they don’t want them. It’s totally healthy to use contraceptives which stop bleeds altogether or create artificial periods.

Moreover, (and I hate to break it to you) artificial periods, the ones you have on many pills during the seven-day break, are also hangovers from an even more puritan age.

There is no reason for a one week break [within which to bleed] any more either. When the pill was first developed, it contained an extremely high dose of hormones – five times what the modern day pill contains now. It made many women feel sick and unwell. So, they liked the idea of a seven-day break from the heavy hormones.

But the pill was also developed in America – a heavily Catholic society – where contraception was frowned upon. If women could still have periods while on the pill, they could mask the fact they were using a contraceptive and it would be less stigmatising. And women themselves were reassured by seeing a period every month as healthy menstrual function.

As science has developed and the dosage is now greatly reduced – and contraception in many parts of the world is far less stigmatised – none of those reasons for a bleed exist any more. The pill just switches your ovaries off and keeps the womb lining suppressed. The injection dupes the body into thinking it’s pregnant; the Mirena coil suppresses the period – there is no point having a period whatsoever other than when you want to reproduce.

In fact, while writing this book, the official health guidance in the UK changed, finally revealing to women on the pill that they no longer needed to take the traditional break to have a bleed. I quote the guidance: ‘There is no health benefit from the seven-day hormone-free interval.’ And, ‘women can safely take fewer (or no) hormone-free intervals to avoid monthly bleeds, cramps and other symptoms.’

This is game-changing. And very overdue.

Pill-taking women across the world erupted in shocked and righteous anger at the news. For decades, women had been bleeding when they didn’t need to. It’s ludicrous. Why has it taken until 2019 for the official health advice to tell them their pill-periods were nonsense?

And the real red rag to the raging bull? Those fake bleeds were designed to make an old man in a white hat happy. Yup. It all comes back to the Pope. Professor John Guillebaud, a professor of reproductive health at University College London, told the Sunday Telegraph that gynaecologist John Rock suggested the break in the 1950s ‘because he hoped that the Pope would accept the pill and make it acceptable for Catholics to use’. Rock thought if it did imitate the natural cycle then the Pope would accept it.’

For more than six decades most women have unknowingly been taking the pill in a way that inconveniences them in order to keep the Pope happy. Digest that. Sticks in the throat a little eh?

Women felt and feel rightly duped. Another sodding period lie told for more than half a century to benefit someone other than the bleeding woman suffering unnecessarily.

Of course, some women don’t want hormones in their body. They like being natural. They want to bleed – regardless of ovarian intention. Some argue the time of the month is a source of strength for them, or perhaps they can’t find a pill or contraceptive which doesn’t make them feel ropey. Others argue that ovulating naturally is good for one’s health, as is the natural production of the progesterone and oestrogen.