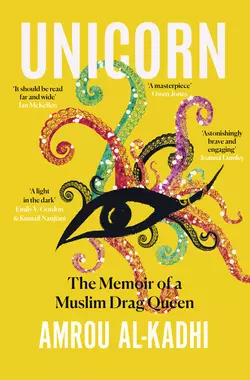

Unicorn

Amrou Al-Kadhi

My name is Amrou Al-Kadhi – by day. By night, I am Glamrou, an empowered, confident and acerbic drag queen who wears seven-inch heels and says the things that nobody else dares to. Growing up in a strict Iraqi-British Muslim household, it didn’t take long for me to realise I was different. When I was ten years old, I announced to my family that I was in love with Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone. The resultant fallout might best be described as something like the Iraqi version of Jeremy Kyle. And that was just the beginning. This is the story of how I got from there to here. You’ll read about my stint at Eton college, during which I wondered if I could forge a new identity as a British aristocrat (spoiler alert: it didn’t work). You’ll read about my teenage obsession with marine biology, and how fluid aquatic life helped me understand my non-binary gender identity. You’ll read about how I discovered the transformative powers of drag while at Cambridge university; about how I suffered a massive breakdown after I left, and very nearly lost my mind; and about how, after years of rage towards it, I finally began to understand Islam in a new, queer way. Most of all, this is a book about my mother, my first love, the most beautiful and glamorous woman I’ve ever known, the unknowing inspiration for my career as a drag queen – and a fierce, vociferous critic of anything that transgresses normal gender boundaries. It’s about how we lost and found each other, about forgiveness, understanding, hope – and the life-long search for belonging.

(#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

Copyright (#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

Dedication (#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

For Queer People

of Colour everywhere

&

Chet & Lois,

my favourite unicorns

Contents

1 Cover (#u5643c6f5-06ef-5564-b9c8-13d0055977b8)

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents (#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

6 INTRODUCTION

7 FEAR AND LOVING IN THE MIDDLE EAST

8 THE IRAQI COMES TO LONDON: A STRANGE CASE OF JEKYLL AND HYDE

9 I DON’T WANT TO BE WHERE THE PEOPLE ARE

10 A SEAT AT THE WRONG TABLE: MY TWO-YEAR STINT AS A BRITISH ARISTOCRAT

11 ME, MYSELF, AND LIES: THE MANY FACES OF BEING A DRAG QUEEN

12 THE QUEER QURAN, AND OTHER QUANTUM CONTRADICTIONS

13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

14 About the Author

15 About the Publisher

LandmarksCover (#u5643c6f5-06ef-5564-b9c8-13d0055977b8)FrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiii (#ulink_c799907f-5e44-54d0-bb9b-1b173291ed91)iv (#litres_trial_promo)v (#ulink_a34b5172-0776-54bb-b93f-a813d9c2d253)1 (#ulink_f024240e-445c-5472-b2cb-767f5f41bbe7)2 (#ulink_59b5c298-9648-5eaa-b68c-1cfc7b81ec68)4 (#ulink_5d855453-494b-5c07-9eeb-64641ba943b1)6 (#ulink_427be6fa-658e-5e9a-881d-fcd72f66fd98)8 (#ulink_f2de8555-0418-5eac-8759-a06d4e1caf46)10 (#ulink_5cac9187-f707-5928-99a9-f8294dd58f03)11 (#ulink_8772fa9f-35dd-543a-adad-bb19f26552d4)13 (#ulink_0267801d-234e-59c4-861c-15a563158561)14 (#ulink_38e3599d-633d-5ca7-a716-064141030e3e)15 (#ulink_95ab6ad6-f845-5044-adcb-649c02c83df0)16 (#ulink_6e05e7f8-b3b3-5616-bcc0-1c8c1182790b)17 (#ulink_d9dfdf1f-6bcd-5ac5-b0cc-1e21fcc822fd)18 (#ulink_8af499d3-beb6-5b5a-acda-351a77032db4)19 (#ulink_dc18bd02-522f-563d-b756-99c2dfafd586)20 (#ulink_f25f1b6e-9010-549e-bb65-d04abb678eb4)21 (#ulink_7ba6924f-994d-5754-a70a-099054ebfa55)22 (#ulink_f5fe4764-fa9a-581b-be09-2f70acd12d5d)23 (#ulink_6c7bab48-56d5-561b-96e7-dcdad68da6c0)24 (#ulink_bf2cdf39-a45f-566b-9880-fcd7c26d543b)25 (#ulink_2a881c20-39ac-55e3-a230-f1e5ca63962c)26 (#ulink_e1832782-08c9-5cf2-9ef5-bc4e777b85e9)27 (#ulink_df43ca25-7b0a-5c23-acda-f528ebf1c76b)28 (#ulink_6c743ac8-5e3f-5e1a-8ea1-7e45ae6e5daf)29 (#ulink_ff6ea848-5a98-55df-b787-a082be40a189)30 (#ulink_005fb425-8346-5df0-9799-06a0c18ed128)31 (#ulink_99a9440a-66b8-5b9a-a31a-32bc498447e0)32 (#ulink_97309fe0-5013-5954-b5ef-745c6b2fa8ab)33 (#ulink_6f277382-17d1-53b7-9bae-5489a572b5da)34 (#ulink_0e9f4062-47a2-50e3-b14d-6e778cb10778)35 (#ulink_b8192dbd-d1e0-513a-86d2-6265c32baecd)36 (#ulink_d8dae066-f93e-5cf8-9ee3-e6fee0c43002)37 (#ulink_c2533afd-811e-5340-bb5e-c8a676bc091e)38 (#ulink_fa07ca5e-c918-53f3-8db4-bd11bfe5fc3b)39 (#ulink_d9fa3f38-0a77-52ca-837f-58d77d5c350a)40 (#ulink_919b06de-964d-510b-aff1-9046c41f2c34)41 (#ulink_12d9e167-29c8-537e-ad09-30eaf5b2bf3b)42 (#ulink_35bac8bf-b24e-57fc-97cb-6d7bae6ab795)43 (#ulink_cb1c117d-e5cc-56b1-9b8d-c6eede8d9fbe)44 (#ulink_351f610c-679f-5ec5-b742-6d2e4daf5c81)45 (#ulink_39ba5d42-fb11-527d-9e83-4cec4bd6b90c)46 (#ulink_3e1ba9bd-26c4-5244-8d4d-5a9baac1cba4)47 (#ulink_5145ea97-9ca5-5a3a-86c3-8b06df1fb009)48 (#ulink_05c4b101-705b-5218-aef1-aac7536a394f)49 (#ulink_d6e3e3b3-da59-5d27-aabc-b5d6278fc367)50 (#ulink_f335516f-7d9c-5e17-9eb8-de49e8607013)51 (#ulink_338e52a6-e116-5e6b-bf20-9cafbdb727ee)52 (#ulink_5f853586-5657-52ce-b0e2-79dc72023708)53 (#ulink_aa80ff1a-00e7-55a8-a176-7ff38e78d3d8)54 (#ulink_ba812ce4-24bf-5dd9-8c6c-b0d319d96e1f)55 (#ulink_67ae2157-0cb4-57ed-9fce-834832acc4cb)57 (#ulink_31996717-e482-5da7-b95f-417534a74092)58 (#ulink_d37a9c1e-7631-5a46-8e5d-01f231c4d6f3)59 (#ulink_03481f6d-57d9-5e27-ac61-d624701db4f3)60 (#ulink_147c47ed-19d9-5889-b7f7-0d77bfe3f71f)61 (#ulink_be8c4659-804d-5525-a0a4-1359b4a1db98)62 (#ulink_affb9c39-5e84-5b21-ba15-9f9f07cd8451)63 (#ulink_47db0ae8-a2e9-5e4a-8ea7-f1270ddd1ecc)64 (#ulink_f7310846-302d-52df-813d-b786ed1825fa)65 (#ulink_f7310846-302d-52df-813d-b786ed1825fa)66 (#ulink_ae12265c-ee6a-570b-9b4e-db72a04c3dc1)67 (#ulink_17d7cbaa-2707-570b-ad41-54770a0a065b)68 (#ulink_d595a119-5ba4-59f1-b320-a797c0b0d9df)69 (#ulink_9ef6fdc8-2b5a-5671-afa1-ddac3c16eead)70 (#ulink_aa51188d-22bb-565a-a0f6-5f25653aa5ce)71 (#ulink_89d2fcf7-1fcd-509f-8cbf-a23ca23a8bfe)72 (#litres_trial_promo)73 (#litres_trial_promo)74 (#litres_trial_promo)75 (#litres_trial_promo)76 (#litres_trial_promo)77 (#litres_trial_promo)78 (#litres_trial_promo)79 (#litres_trial_promo)80 (#litres_trial_promo)81 (#litres_trial_promo)82 (#litres_trial_promo)83 (#litres_trial_promo)84 (#litres_trial_promo)85 (#litres_trial_promo)86 (#litres_trial_promo)87 (#litres_trial_promo)88 (#litres_trial_promo)89 (#litres_trial_promo)90 (#litres_trial_promo)91 (#litres_trial_promo)92 (#litres_trial_promo)93 (#litres_trial_promo)94 (#litres_trial_promo)95 (#litres_trial_promo)96 (#litres_trial_promo)97 (#litres_trial_promo)99 (#litres_trial_promo)100 (#litres_trial_promo)101 (#litres_trial_promo)102 (#litres_trial_promo)103 (#litres_trial_promo)104 (#litres_trial_promo)105 (#litres_trial_promo)106 (#litres_trial_promo)107 (#litres_trial_promo)108 (#litres_trial_promo)109 (#litres_trial_promo)110 (#litres_trial_promo)111 (#litres_trial_promo)112 (#litres_trial_promo)113 (#litres_trial_promo)114 (#litres_trial_promo)115 (#litres_trial_promo)116 (#litres_trial_promo)117 (#litres_trial_promo)118 (#litres_trial_promo)119 (#litres_trial_promo)121 (#litres_trial_promo)123 (#litres_trial_promo)124 (#litres_trial_promo)125 (#litres_trial_promo)126 (#litres_trial_promo)127 (#litres_trial_promo)128 (#litres_trial_promo)129 (#litres_trial_promo)130 (#litres_trial_promo)131 (#litres_trial_promo)132 (#litres_trial_promo)133 (#litres_trial_promo)134 (#litres_trial_promo)135 (#litres_trial_promo)136 (#litres_trial_promo)137 (#litres_trial_promo)138 (#litres_trial_promo)139 (#litres_trial_promo)140 (#litres_trial_promo)141 (#litres_trial_promo)142 (#litres_trial_promo)143 (#litres_trial_promo)144 (#litres_trial_promo)145 (#litres_trial_promo)146 (#litres_trial_promo)147 (#litres_trial_promo)148 (#litres_trial_promo)149 (#litres_trial_promo)150 (#litres_trial_promo)151 (#litres_trial_promo)152 (#litres_trial_promo)153 (#litres_trial_promo)154 (#litres_trial_promo)155 (#litres_trial_promo)156 (#litres_trial_promo)157 (#litres_trial_promo)158 (#litres_trial_promo)159 (#litres_trial_promo)160 (#litres_trial_promo)161 (#litres_trial_promo)162 (#litres_trial_promo)163 (#litres_trial_promo)164 (#litres_trial_promo)165 (#litres_trial_promo)166 (#litres_trial_promo)167 (#litres_trial_promo)168 (#litres_trial_promo)169 (#litres_trial_promo)170 (#litres_trial_promo)171 (#litres_trial_promo)173 (#litres_trial_promo)175 (#litres_trial_promo)176 (#litres_trial_promo)177 (#litres_trial_promo)178 (#litres_trial_promo)179 (#litres_trial_promo)180 (#litres_trial_promo)181 (#litres_trial_promo)182 (#litres_trial_promo)183 (#litres_trial_promo)184 (#litres_trial_promo)185 (#litres_trial_promo)186 (#litres_trial_promo)187 (#litres_trial_promo)188 (#litres_trial_promo)189 (#litres_trial_promo)190 (#litres_trial_promo)191 (#litres_trial_promo)192 (#litres_trial_promo)193 (#litres_trial_promo)194 (#litres_trial_promo)195 (#litres_trial_promo)196 (#litres_trial_promo)197 (#litres_trial_promo)198 (#litres_trial_promo)199 (#litres_trial_promo)200 (#litres_trial_promo)201 (#litres_trial_promo)202 (#litres_trial_promo)203 (#litres_trial_promo)204 (#litres_trial_promo)205 (#litres_trial_promo)206 (#litres_trial_promo)207 (#litres_trial_promo)208 (#litres_trial_promo)209 (#litres_trial_promo)210 (#litres_trial_promo)211 (#litres_trial_promo)212 (#litres_trial_promo)213 (#litres_trial_promo)214 (#litres_trial_promo)215 (#litres_trial_promo)216 (#litres_trial_promo)217 (#litres_trial_promo)219 (#litres_trial_promo)221 (#litres_trial_promo)222 (#litres_trial_promo)223 (#litres_trial_promo)224 (#litres_trial_promo)225 (#litres_trial_promo)226 (#litres_trial_promo)227 (#litres_trial_promo)228 (#litres_trial_promo)229 (#litres_trial_promo)230 (#litres_trial_promo)231 (#litres_trial_promo)232 (#litres_trial_promo)233 (#litres_trial_promo)234 (#litres_trial_promo)235 (#litres_trial_promo)236 (#litres_trial_promo)237 (#litres_trial_promo)238 (#litres_trial_promo)239 (#litres_trial_promo)240 (#litres_trial_promo)241 (#litres_trial_promo)242 (#litres_trial_promo)243 (#litres_trial_promo)244 (#litres_trial_promo)245 (#litres_trial_promo)246 (#litres_trial_promo)247 (#litres_trial_promo)248 (#litres_trial_promo)249 (#litres_trial_promo)250 (#litres_trial_promo)251 (#litres_trial_promo)252 (#litres_trial_promo)253 (#litres_trial_promo)254 (#litres_trial_promo)255 (#litres_trial_promo)256 (#litres_trial_promo)257 (#litres_trial_promo)258 (#litres_trial_promo)259 (#litres_trial_promo)260 (#litres_trial_promo)261 (#litres_trial_promo)262 (#litres_trial_promo)263 (#litres_trial_promo)264 (#litres_trial_promo)265 (#litres_trial_promo)266 (#litres_trial_promo)267 (#litres_trial_promo)268 (#litres_trial_promo)269 (#litres_trial_promo)270 (#litres_trial_promo)271 (#litres_trial_promo)272 (#litres_trial_promo)273 (#litres_trial_promo)274 (#litres_trial_promo)275 (#litres_trial_promo)276 (#litres_trial_promo)277 (#litres_trial_promo)278 (#litres_trial_promo)279 (#litres_trial_promo)280 (#litres_trial_promo)281 (#litres_trial_promo)282 (#litres_trial_promo)283 (#litres_trial_promo)284 (#litres_trial_promo)285 (#litres_trial_promo)286 (#litres_trial_promo)287 (#litres_trial_promo)289 (#litres_trial_promo)290 (#litres_trial_promo)291 (#litres_trial_promo)292 (#litres_trial_promo)293 (#litres_trial_promo)294 (#litres_trial_promo)295 (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

For the twenty-fourth night that August, I found myself crossed-legged on the floor of a damp, pungent dressing room. As the rumblings of an Edinburgh crowd reverberated from the venue next door – I say venue, it was more like a cave – I used my little finger to apply gold pigment to my emerald-painted lips. Denim, the drag troupe that I set up seven years earlier, had survived the gruelling Fringe Festival, and we were one show away from crossing our scratched heels over the finish line.

A month of performances, often two a day, had taken its toll. My skin was at war with the industrial quantity of make-up it was being suffocated in (a two-hour procedure each time); I had obliterated my left kneecap because of a wannabe-rockstar ‘jump-and-slam-onto-the-ground’ move I felt impelled to perform each show; and a boy I was seeing had suddenly disappeared on me (I secretly hoped that death, instead of rejection, would be the explanation, but it turned out he was a ghost of a different sort: he had indeed stopped fancying me).

Despite feeling so weathered, I was itching to get onstage again. I always feel empowered when I’m in drag and entertaining a crowd – it’s my sanctuary, a space where I invite the audience into my own reality, where I don’t need to adhere to the rules of anybody else’s. No matter how low I’m feeling, the transformative power of make-up and costume is galvanising; for most of my life I’ve felt like a failure by male standards, and drag allows me to convert my exterior into an image of defiant femininity. This particular show was always exhilarating to perform, because it was the first time I honestly articulated my tumultuous relationship with Islam onstage, trying to mine humour in the unexpected parallels between being queer and being Muslim. How I haven’t been hit with a fatwa yet, I do not know.

A student volunteer usher told us we were moments away from the start of the show, and I did my pre-show ritual where I box with the air and shout ‘IT’S GLAMROU, MOTHERFUCKERS’. It comforts me to imagine my haters as the punch bag ‘motherfuckers’. Then I formed a circle with my other queens, our hands all joined at the centre in a moment of communion. The synth chords burst through the speakers, and the audience whooped as we strutted through a blackout onto the stage, our backs facing the crowd, pretending that the actual sight of our faces would be some sort of reward. A suspended beat, then lights pummelled the stage. I thrust my arms above me as if it were Wembley (I won’t lie; it usually is in my mind), and eyed the dripping condensation coating the cave ceiling, one drop a moment away from plopping on my face. After a prolonged and hyperbolic musical introduction – allow a queen her fifteen minutes – the show began with each of us turning to face the crowd one by one, until I pivoted around last. The next part was supposed to be me proclaiming ‘I AM ISLAM’, followed by the Muslim call to prayer remixed with Lady Gaga’s ‘Bad Romance’.

But on this final night, as I opened my mouth to start the show, I felt a little bit of sick at the back of my throat, and I found I couldn’t make a sound. Six Muslim women, the majority wearing hijabs, were sitting in the front row. There, looking directly up at me, were multiple avatars of my disapproving mother, about to remind me how shameful I was.

The ensuing performance was about as fun as your parents walking in on you having sex, and then staying to watch until you come. For a section in the show I sang a parodic ‘Why-Do-You-Hate-Me’ type number to my ex-boyfriend – but the boyfriend I was singing to was Allah. Throughout the routine, the women in front of me were using Allah’s name in a more God-fearing way – ‘Allah have mercy’ (in Arabic) seemed to be the most common refrain. Another highlight included a sketch in which I compare men praying in mosques to gay chemsex orgies. When I dared glance out in front of me, the mother of the group seemed to be repenting in prayer on my behalf. I started to ricochet around a mental labyrinth of paranoia, the censorious voices from my childhood chattering loudly in my mind. As my past enveloped me, the empowering armour of my drag began to dissolve rapidly. I stumbled over my lines, tripped on my heels – more than once – and even welled up onstage (which caused the eyelash glue to incinerate my cornea). The rest of the drag queens – as well as the audience – were white, so it felt as if the Muslim women and I were operating on a different plane of reality from everyone else, one where only we knew the laws.

Once the show finished, I sprinted backstage and threw up in a bin. My agent knew something was up and ran to the dressing room. I trembled as she hugged me, distressed at the offence I knew I’d caused. I felt like I was fourteen again, when my parents would tell me on a daily basis that my flamboyance was the root of their unhappiness. I’d worked so hard to create my drag utopia, and until that night, it had been my haven.

And then came the news I was dreading. The women, waiting outside the stage door, passed on a message to the usher: they wanted to see me.

Like a reincarnation of my teen-self, I shuffled off outside, with all the strength of a young seahorse adrift on an ocean current. Seven years after drag had liberated me, I was about to relearn that my liberated new identity required disciplinary action.

There they were, all lined up. The mother of the group, who was dressed head to toe in Islamic robes, stared down at the floor, refusing even to look at me. Great, I thought, she thinks I’m Satan. She whispered something in Arabic to her daughter that I couldn’t make out. As her daughter began speaking, I twitched with terror, like a defendant in court about to learn the jury’s verdict.

‘My mom’s super Muslim, yeah, so she’s a bit uneasy, but she wanted me to tell you that she thought you were amazing, and that you should be really proud.’ Not guilty. In my dumbfounded jubilation, I went to hug her mother, who quickly shifted, like a pigeon does when you suddenly kick the pavement.

‘Easy, my mom’s from Saudi Arabia and really Muslim, so she can’t hug you, but she thought it was so cool seeing a gay Muslim on a stage like that. She said she feels really proud to have been here.’

I explained how I believed they were cursing me throughout the show. It turns out their expressions were akin to a colloquial ‘Oh my God!’ uttered out of enjoyment. The young woman then held my hand, stared honestly into my eyes, and said: ‘But your song to Allah …’ Fuck. Guilty on some counts. ‘… it broke my heart. I’ve been there. Trust me, I’ve been there – I’m a woman living in Saudi Arabia. But the thing is, Glamrou – Allah loves you.’

And with that, the women said their goodbyes, their Muslim drapery billowing in the Scottish wind, floating away from me like a mystical collective of apparitions, as if the entire encounter might have been a hallucination. Now, in general these days, I find it very difficult to sob – my body rarely gives in to the urge (the only exception being when I watch families in whom I have no investment celebrate their loved ones on X Factor, which always gets me). But as the women disappeared from the stage door and into the alleyway leading out to the Edinburgh night, I stepped after them and collapsed against the wall, convulsing so hard that I gave myself a splitting headache. Once the sobbing subsided and I was back out of the matrix, I felt as if I’d emerged from some combination of an exorcism and a K-hole.

I’ll forever remember that night as the precise moment when, for the first time, all the different parts of my identity collided. I’ve spent my whole life feeling like I don’t belong. As a queer boy in Islam class, the threat of going to hell because of who I was inside was a very real and perpetual anxiety. Despite being able to leave the Middle East for a liberal Western education that afforded me numerous privileges and opportunities, I faced constant discrimination and prejudice when I won a place at Eton for two years (two of the worst of my life). I’ve lived between the Middle East and London, and have felt too gay for Iraqis, and too Iraqi for gays. My non-binary gender identity has meant that I don’t feel comfortable in most gendered spaces – gay male clubs, for instance – and I regularly feel out of place in my own male body, as though it doesn’t match up to who I am internally. For a long time, I felt as if I belonged under water, in a marine world with colours to rival the outfits of any RuPaul drag queen, where things flow freely, formlessly and without judgement, where difference is revealed to be the very fabric of this universe. On land I’ve felt like a suffocating beached whale, unable to swim to anyone or anywhere.

But that Edinburgh night, as the beautiful girl in the hijab held my hand and reassured me of Allah’s unconditional love and I stood in front of her in a sequin leotard and a melting face of sapphire glitter, I finally felt as if I belonged.

The December before that Edinburgh summer, I decided to get a unicorn tattooed across my chest. Christmas is one of the hardest periods for me every year; the months leading up to it are saturated with pictures of united families in green paper crowns beaming around the dinner table, and the dominant cultural narrative tells us that it’s the time to be with the real people who know and love us the most. Most friends of mine retreat to the houses they were raised in for cosy, Hallmark-worthy reunions, acquaintances post gifts from partners on Instagram, and it is the time I feel most divorced from Britain, the Middle East, my family, and, well, the world. So to keep me company for the holiday season, I invited a permanent-ink unicorn to live above my sternum.

I feel a great affinity with unicorns. They are the ultimate outsiders, destined to gallop alone. They share the body of a horse and are similar in form, but are of a different nature, almost able to belong in an equine herd, but utterly conspicuous and irrefutably other. For, no matter what, their fantastical horn cannot be concealed, signifying that they are of a different order entirely. In some medieval renderings of unicorns, the horns bring with them the sense of the pathetic; they are a deformity that invites the outside world to taunt the special being, almost like a dunce. As someone who has felt displaced for so long, I’ve harboured resentment for my own obtrusive horn, which has made it impossible for me to assimilate anywhere.

But as much as the horn is an unwelcome protrusion, perhaps even a social inconvenience, it is also a symbol of pride, of a creature flaunting its difference without shame. For the horn also tells us that the unicorn is a survivor, a rare and tenacious creature, ready to fight should its difference bring it in the way of violence. For me, the multiple meanings of unicorns encapsulate the very essence of being queer. Their identity challenges the status quo and is violated by the normative. They long to gallop in a herd, but struggle to ride to the rhythm of others. They can almost hide in plain sight, and yet are also unquestionably unique.

Like a unicorn, I’ve never been able to escape my difference from others. As someone who’s always existed between cultures, classes, genders, and racial groups, I have what society deems an ‘intersectional’ identity. The concept of ‘intersectionality’ refers to the fact that we cannot study the issues surrounding one oppressed social group without understanding its intersections with many others; for instance, it is superficial to have a feminism that dismantles systems of misogyny without also understanding how this intersects with structures of racism (when examining the wage gap for instance, it’s critical to consider not only the disparity between men and women, but the one between white women and women of colour). And, though mine is an extreme example of this, every person’s identity contains multiple facets that intersect with each other internally, and which are represented by intersecting political and social arguments in the outside world. Sometimes these intersections coexist peacefully; sometimes they are in conflict, and tear us into pieces.

My intersectional identity has never felt stable. The best way I can describe it is to say that it’s like playing a really exhausting game of Twister with yourself all day every day, a key part of your identity choke-holding you on one end of the flimsy plastic sheet, while you wrap your legs around its opponent on the other. All the various facets of my identity have pulled each other in polarising directions, leading at times to absurd contradictions, episodes of severe disorientation, and deep internal fractures.

The tattoo artist who gave me my unicorn is a wonderful queer practitioner called Jose Vigers. With an empathetic ear and unreserved generosity of spirit, Jose listened as I explained over Skype what unicorns meant to me. After some wonderfully collaborative discussions, we settled on the design that now armours my heart: a unicorn, being attacked with arrows, on the cusp of collapsing, but strengthened by a BDSM harness and its enduring fighting horn. I wanted a picture that relayed both fragility and strength: an image of a being whose very power and ability to survive derive from the pain they have suffered.

I hope that the story I am about to tell will paint a similar picture.

FEAR AND LOVING IN THE MIDDLE EAST (#uc90c208d-9db9-5741-8063-af6deaffa9dd)

‘Mama, should I get us a condom?’ I was eight years old when I asked her this. We were taking our regular joint evening nap. I lay entangled in her embrace – my father, as usual, was travelling with work – and my fingers swam through her silky golden locks, as if their depths were infinite. At that age, my mother had convinced me that eating roast chicken would result in jewel-tinted hair, but I know now that she had what we call ‘highlights’.

I had heard the word condom a few times by the age of eight – not in my school’s daily Islam lessons, nor at Iftar, the nightly family meal we shared to break our fast during Ramadan, but from the American sitcoms that occasionally sneaked their way through to Bahraini TV networks. I had ascertained that condoms were used between husbands and wives, or boyfriends and girlfriends. Not understanding what sex was, I presumed a condom was a gift shared between people who love each other, only to be bestowed in a bed (it was as a gay adult that I learnt what an apotropaic gift a condom truly was). And so, after a process of logical deduction, I was confident that I fully understood the true definition of condoms.

And here was the perfect opportunity: I was tightly wrapped in the person I loved most on this earth, and in the designated location for this American gifting ritual. I detached myself partially from her maternal clutch, and looked up at her with the earnest expression of a dog expecting a treat for not shitting inside. ‘Mama, should I get us a condom?’

My mother’s eyes, which I had only ever known to be a source of unending nourishment and affection, changed from their comforting almond shape to a severe angular squint, as if a demon possessed her, an enraged serpent imprisoned behind her glassy pupils. We were gridlocked in this glare of purgatory for what felt like the length of my entire childhood thus far.

‘WHERE DID YOU HEAR THAT, AMROU?’ The severity of her interrogation caused an unsettling warble in her voice. ‘WHY ARE YOU SAYING THIS?’ This horrified woman was not one I had ever encountered before, and I felt, for the first time in my life, genuinely scared of her. My strategy was to revert to our tried-and-tested form of interaction, and so I responded with: ‘But Mama, it’s because I love you.’

My mother leapt up off the bed, my fingers ripped from her halo of golden hair, and she chanted in Arabic, praying to Allah for guidance. If I had known what drag was at the time, I’d probably have enjoyed the melodrama; my mother’s white silk dressing gown floated around her as if she were a deity carried by clouds (albeit ones crackling with lightning), and she had all the fiery passion of an Almodóvar heroine. Her thunderous roar eventually subsided as she came to realise that I had no clue what the true function of a condom was, and she sat on the bed in a funerary pose, huddling away from me like someone who had just suffered a Dementor’s kiss. I tried to nuzzle my way back into the nest, but as I lay my head on her lap, she brushed me off, and told me to go to my room.

It was at this moment that I had the tragic realisation that the bond between us was not sacred. I became aware of my capacity to transgress; until this point, the idea of anything restricting our love was utterly alien. Something I said had revealed boundaries to what I believed was a boundless love. As I lay in my bed that evening – my twin brother Ramy sleeping soundly on the bed next to me – the weight of this overwhelmed me, and I wept so hard that I was eventually exhausted.

How could anything I do upset Mama? Are there things happening in my brain and body that might cause her to reject me? It felt like the purity of our bond was stained for ever. My mother was the light and love of my life, so the idea that there could be something other than love between us filled me with a terror that has endured till this day. In all honesty, I think it governs pretty much everything I do.

Following ‘Mama-condom-gate’, I made it my immediate mission to repair any fissures between us. My strategies ranged from the sweet and charming to the dangerous and really quite alarming.

The first tactic was to remind my mother how cherubic I was, to eradicate any notion of me as at all transgressive. Mama always lay my and Ramy’s pyjamas on our beds following our evening showers – here was the perfect opportunity to intervene. And so, every night for the week that followed, I beat her to this, as a way to dazzle her with the sanctity of my little heart. And I was victorious. When Mama witnessed my act of complete ‘selflessness’, she was so moved that she cried with joy, and rewarded me with one of my favourite activities – the aeroplane game. This involved Mama lying on the floor and putting her feet up in the air so my tummy could rest on them, allowing me to fly above her while gazing into her mahogany eyes. RESULT. But as the week dragged on, the novelty wore off (on her side, anyway), and Mama grew frustrated with the number of creases caused by my unfolding techniques. Mama, you see, was an aesthetic perfectionist – you might even say an aesthetic dictator. My parents’ finances were precarious during my early childhood, and so the need to maintain an external image of aesthetic perfection was paramount. Mama has an odd sense of priority; she was more upset when I once wore socks that had holes in them to school than the time I got attacked by a neighbour’s very toothy dog. And so, when Mama realised that our expensive pyjamas had developed wrinkles, she told me to stop putting out the clothes because I kept getting it wrong. POOP. Wrong. I’m wrong. Will she ever see me as right again?

Playing Mama at her own game was a poor tactic – why attempt to do something that she could always do better than me? If ‘Mama-condom-gate’ had robbed me of my childhood innocence, then I needed to remind her that I was still only a child.

Early one night, I was playing in the pool that we shared with all the houses in our compound. It was a characteristically unremarkable evening. My brother and I were sinking toy ships in the water – probably inspired by the same early-millennium morbidity that led to the murder of millions of Sims on PCs – and our new nanny was supervising us nearby, so relaxed in the autumn Bahrani heat that she was snoring. Knowing that my mother would be arriving home at any second, I decided to scream for her. I can’t with clarity remember my precise thought process, but something about the embryonic feeling of being submerged in water stimulated my idea. I knew what I had to do. And so I screamed ‘Mama!’ at the top of my lungs, over and over and over again. My brother watched me, totally bemused, and soon enough, behind the corrugated-iron fence surrounding the pool, I saw the legs of my mother, restricted by the mauve pencil skirt she wore to the hospital where she worked as a translator, sprinting towards the gate, until she burst through, panting in front of me with the frail regality of a Hitchcock victim. When my mother saw me treading water, smiling widely because she was home from work, she slumped onto a deckchair and bundled me up, kissing me all over my face, even though I was soaking wet.

Later that evening, I went to find Mama in her bedroom, hoping to rekindle the lost innocence of our evening nap, but she was in a deep sleep. The mascara stains down her face told me she had been crying. When our nanny saw that I had sneaked myself in, she escorted me out, explaining that my mother needed to rest. ‘You made her think you were drowning earlier, Amrou. She was terrified. You need to let her rest now.’

And so for the second time that week, I stayed up all night and cried in a frenzy of self-loathing. I was certain I hadn’t intended my mother to think I was on the edge of death – or did I? Am I that cruel? No, I’m just a kid! But I had engineered a scenario that would result in her running to me. I was just excited to see her, that’s all. I miss Mama all the time.

In the weeks that followed, I interpreted any evasiveness from my mother as her thinking I was fucked-up for my poolside act of emotional manipulation. She felt further away from me than ever, and I yearned for a time before my purity was called into question. One evening after school, a day during which I ached to be reunited with her, Mama spent hours gossiping with friends on the phone. I watched her as she glided around the kitchen, delicately holding out a Marlboro Red cigarette. I was so envious of her friends on the end of the line, who had the privilege of being audience to Mama’s hilarious anecdotes. A few times during the evening, I wrapped my arms around her torso as she stayed glued to the phone. With that anthropologically curious way you can let someone know to stop touching you by squeezing them with a firm, conclusive gesture, Mama fetched a baklava from the counter, put it in my mouth, and definitively detached me. In the living room next door, my brother and father were watching football together – an activity so profoundly unenticing to me that the sheer boredom of it could lead me into an existential ‘what is the point of life?’ spiral, even as a toddler – and so my desire for maternal communion only intensified.

As I went back into the kitchen, where Mama now sipped a Turkish coffee as she laughed infectiously on the phone, I asked her when she would be done – at which she shooed me off, loath to interrupt the flow of what was clearly a banging anecdote. Those lucky women on the other line! The situation was desperate. Mama was slipping away from me, and she urgently needed to remember what we had. My eyes darted around the kitchen, searching for a remedy. Maybe I could spill water on the floor and pretend to slip? My not being a stuntman threw this one off the drawing board. Maybe I could pretend to break a vase? My mother had a passion for expensive tropical flowers – or maybe just things that were expensive, period – so I decided this would do more damage than good. And then I spotted the steaming bronze Turkish coffee pot on the cooker, the shimmer of its Arabesque metallic belly beckoning me towards it. Like a cunning magpie, I made a beeline, and picked it up with my bare hands, incinerating my right palm until I screamed in agony. When Mama saw what had happened, she dropped the phone, grabbed my hand and put it under cold running water as I sobbed into her arms. She was mine again.

She was mine for the rest of the night. Because my hand was so badly blistered from the ‘accident’, she stayed with me as I slept. I lay on the couch, with her on the floor next to me, holding up my hand so that I didn’t hurt it during my sleep. And she sat like this until I woke up the next morning – my beautiful, generous mother. Now I realise these were extreme measures to take for a moment of maternal comfort. But believe me when I tell you: there was no other option besides Mama.

Dubai was my home until the age of seven, Bahrain till I was eleven. Where I was raised, there was a marked distinction between the masculine and the feminine. I grew accustomed to binaries from a very early age, even though I had no awareness of the concept of them. The earliest recollection I have of a strict division between the sexes was when my mother drove to the border of Saudi Arabia (my brother and I were curious to see it). My mother edged to the border and drove away again. ‘But Mama, we want to go in,’ I implored, confused about what was stopping her. ‘Women aren’t allowed to drive in Saudi,’ my mother said with a remarkable calm, as if the patriarchy lived harmoniously inside her, at one with her brain and mouth. ‘Oh, OK,’ I said, mirroring my mother’s breezy tone. But this was only one incident among many that erected a strict scaffolding of gender rules inside me. Gender segregation was so embedded into the fabric of life that it was impossible not to internalise it and believe it was utterly normal. In mosques, men and women prayed in separate areas; in many Muslim countries, even the form and methods of prayer change depending on your gender. And when it comes to secular activities, the Middle East can be remarkably homosocial (you could say ironically so).

Like schoolchildren separated into queues of girls and boys before PE, my parents always split up when entertaining guests at home. My mother drank tea and smoked with the other wives in one room – all of them trampling over each other to show off the most recent designer pieces, as though it was some label-obsessed Lord of the Flies – while my dad and the husbands claimed the larger room, where they puffed on cigars and gambled. When my brother and I were ‘lucky’, we were invited to the pews of masculinity, giving us an insight into the cunning rules of poker – ‘lying to make money’ I called it – and tuning our ears to conversations about business (also lying to make money). Ramy clearly felt privileged to have access to this space, and wherever possible would initiate poker games with his own friends in a classic case of social reproduction, all of them future Arab homeboys in the making.

One night, when the whisky-scented card game was drawing to a close, I excused myself to go to bed. As I made my way, I hovered by the corner of the women’s quarter, peering in to get a glimpse of a world with which my heart felt more aligned. This was a room to which I needed the key; each guest was decked in enough jewellery to make the collective room feel like a vault at Gringotts (yes, I like Harry Potter), and textured fabrics of the richest emerald, sapphire, and ruby hues. The conversational mannerisms were dynamic and poetic. I watched with wonder as my mother entertained her guests, how she conducted their laughter as if the room were an orchestral pit, channelling an energy diametrically opposed to the square masculinity next door.

My mother’s Middle East was the one I felt safe in; this was especially the case the more Islam dominated my life. As a child, I was taught to be extremely God-fearing, and Allah, in my head, was a paternalistic punisher. He could have been another man at the poker table, but one much mightier, more severe than the ones I knew, one who might put his cigar out on my little head.

From as early as I can remember, I was forced to attend Islam class every week at school. When I got to Bahrain, the lessons went from warm and fuzzy – where Allah was a source of unending generosity and love – to terrifying, forcing open a Pandora’s box I’ll never be able to close completely.

At each lesson, the other children and I sat jittery at our desks and looked up at the Islam teacher. Her ethereal Arab robes cloaked stern arthritic hands and the billowing black fabric affirmed her piety. Her warnings about Allah’s punishments were grave. We were taught that throughout our lives, any sin committed would invite a disappointed angel to place bad points on our left shoulder, while any good deeds would allow an angel to place rewarding points on our right. Sins were remarkably easy to incur, and could stem from the most natural of thoughts – I’m jealous of that girl’s fuchsia pencil case – while good deeds were nearly impossible to achieve at such a young age, and only counted when you made an active, positive change in the world, like significantly helping a homeless person (a hard task for any seven-year-old). Sins, Islamic class taught us, hovered everywhere around us, and we had to do whatever possible to avoid them. Any time a slipper or a shoe faced its bottom up to the sky – an unimaginable insult to Allah – we’d be hit with a wad of negative points (it’s important to note that many things we know to be sins were inherited from cultural traditions rather than the Quran). And so, once I moved to Bahrain, I developed a compulsive habit of scanning any room I entered for upside-down footwear; I’d sprint around houses like a crazed plate-spinner, burdening myself with endless bad points for having got to each piece of footwear too late. These upside-down shoes would cost me up to fifty sins a day, each one a hit of fiery ash from the cigar above my head. Till this day, in fact, I still turn over any upside-down slipper or shoe that I find. And as a young child, I felt so desperate for these elusive positive points on my right shoulder, that at one point I decided I would be a policeman when I grew up, so as to make a career out of acquiring good deeds (little did I know of institutional police corruption).

The consequences of a heavier left shoulder were gravely impressed upon us. In short – as a sinner, you were fucked. Each week in class, we were made to close our eyes and imagine ourselves in the following situation: an earthquake tearing open the earth on its final day, forcing all corpses to crawl out of their graves and travel to purgatory for Judgement Day. Here, Allah would weigh our points in front of everyone we knew, who would come to learn all our sinful thoughts about them. And of course, if one incurred more sins than good deeds during one’s life, the only result was an eternity of damnation in Satan’s lair. As in any gay fetish club worth your money, the activities on offer include: lashing, being bound in rope, and humiliation – except none of it is consensual, it never stops, and you’re also being scalded with fire the whole time. Twenty years since being taught these torturous visual exercises, I am still subject to a recurring nightmare where Allah himself has pinned me to a metal torture bed surrounded by fire, and incinerates my body as he interrogates me for all my transgressions. Around twice a week, this nightmare wakes me up to a bed pooled in sweat (and, weirdly, once in a while, cum).

My left shoulder quickly outweighed my right in points. Of course there were the everyday misdeeds – my brother is annoying me, this food is dry, I think my cousin smells – that occupied my sin-charting angel, like a passive–aggressive driving instructor totting up minor faults. But there were also the major indictments. For instance, at the age of nine, as I was daydreaming in a lesson, I unthinkingly drew the outline of a bum on the Quran – thereby committing the ultimate defacement and simultaneously betraying an unconscious association between anal sex and religion that’s probably straight out of the psychoanalysis textbook. This blasphemy was a crime of such gravity that there was an entire school inquisition, with all the kids in my year group forced to produce writing samples. There I was, sitting on the sizzling hot concrete outside the headmaster’s office, trying to figure out how many good deeds I’d need to settle the insurmountable difference, yet also plotting to botch the test to get another child in trouble.

I got off the hook. After my writing sample was checked, I was told I could go home. On the bus back from school, I remember staring at the sandy pavements, and being struck by how many heavy rocks and boulders there were lying around all over the streets. I counted each one I could see, feeling the weight of every stone in my conscience, all colliding together to create an avalanche of heavy guilt, knowing that some poor Muslim child was getting the punishment of their life for defacing the Quran with an arse.

This obsessive sin collecting had developed into a pretty debilitating OCD by the time I was ten. Here’s how it manifested. Since doctors were highly respected by my family and community – particularly male doctors – I told my parents I wanted to be one, and asked them to enrol me in an after-school first-aid club (and you thought Glee Club was as lame as it gets?). It was here that I learnt of an acronym that ensnared my brain – DR. ABC. It’s short for Danger, Response, Airway, Breathing, Circulation, and it’s the order of things to assess when you see someone in peril. You look around to evaluate the threat of surrounding Danger. You make noise and prod to see if the victim in question Responds. You ascertain whether their Airway is clear. You check to see if they’re Breathing. And you search for a pulse to feel for any Circulation. DR. ABC. It was the key to saving life. DR. ABC. It was the key to doing good. While the exhausted angel on my left shoulder forever beavered away, turning every single moment in time into a concoction of misdemeanours, I had DR. ABC at the forefront of my consciousness, driving me towards the light. Let me explain.

In the first stages, I muttered DR. ABC under my breath at any chance I could. Obsessively repeating DR. ABC meant I wouldn’t have the mental capacity to commit a sin. While my left shoulder was sinking under its wealth of sin, DR. ABC was like a lifeguard, rescuing me from a tarry ocean of transgressions. Let’s say I was sitting at home, with my brother and father yelping while the football played on TV; my DR. ABC incantation would stop any sinful, negative thoughts from forming, such as hoping the TV exploded. During Islamic Ramadan, a month during which we fasted all day as a demonstration of our piety, any internal dubiousness I had over Allah’s rationale to starve his people was diverted by DR. ABC. When my subconscious felt like I was plummeting down a sharp steep cliff edge, DR. ABC was a bit of rope to hang on to, slowing down the inevitable descent. DR. ABC became my form of control. But then, like all systems implementing order, it started to control me. And eventually, it enslaved me.

In periods where I felt especially rotten inside, it would come out with a vengeance. For instance, if I was having a bad day and someone spoke to me, I would count the number of syllables they used through the acronym DR. ABC. So let’s say a classmate at school said, ‘Amrou, do you have a spare rubber?’ That’s nine syllables. And so, in my head I would mutter DR. ABC until I reached nine syllables – D. R. A. B. C. D. R. A. B. Ending on B, my eraser-depleted classmate would now be characterised as a B in my mind. Then imagine the teacher chimed in: ‘Amrou, hand in your homework.’ Seven syllables, D. R. A. B. C. D. R. – R. So they became an R. And on and on this would go, exhaustingly charting the letter-position of everyone who spoke, balancing the syllable counts of the room like a juggler on crack, all to uphold the fascistic order of DR. ABC.

DR. ABC, my new male oppressor, was always buzzing about, calmed only by being with Mama.

As Allah and DR. ABC enacted a mental tug of war with a masculine brutishness, Mama offered a mystical feminine grace of a different order entirely. While public expectation called for a strict separation of the genders, the rules seemed to fall apart for us in private.

I think this was particularly due to the peculiar set-up of our family unit; for the most part, my brother was raised by my father, and I was raised by my mother. (This is why Ramy doesn’t play much of a part in this book – well, until right at the end, when he steps in and has a very significant role.) Weekends were centred around what Ramy and I wanted to do. Ramy enjoyed playing football and going to the arcade; my father was passionate about football, and enjoyed the camaraderie this gave him with Ramy. Baba was also usually drained from his long weeks at work, and enjoyed any activity that required no emotional commitment. My favourite pastime was going to the mall with Mama, and I spent most weekends watching her try on clothes and get her hair blow-dried at the salon (how I loved observing her gossip with the hairdressers, marvelling at the waves of her rich Arab hair and hearing the chorus of laughter that greeted her anecdotes). Whenever Mama was driving, I always seemed to be in the front seat of her car; Ramy was Baba’s passenger. Among relatives, it became a family mythology that Amrou was Mama’s and Ramy Baba’s; in all honesty, it sometimes feels like we had separate childhoods with little overlap.

‘Amoura,’ Mama sang from her bedroom one evening, a tune that I was more than happy to follow. For I knew what this musical tone meant. ‘Yes, Mama?’ I said with a performed coyness, knowing full well the treat that awaited me. Mama was going out to dinner with friends, and she needed help deciding which pair of shoes to wear. Her left foot flaunted a short-heeled, patent silver, open-toe number – divine – while her right foot donned a more sensible boot, though not without its embellishments, which included studs, and gold eyelets for the laces. Like a runway model posing for a designer, Mama switched from profile to profile so I could assess the full picture before giving my vote. I went for the silver (a total no-brainer). My mother winked at me, then fetched a baklava sweet from her make-up table, which she fed me as she stroked my hair, chanting, ‘My clever boy. My clever, darling boy.’ Mama and I knew that she was going to choose the silver shoe all along, but this performance was all part of our secret language. She knew I was illiterate in football, but the grammar of glamorous footwear – in this I was fluent.

There were other iterations of our secret club. When my brother and father went to play in the park, I would stay in to ‘finish my homework’. Once the echoes of football studs against the marble floor were no more, I emerged from my bedroom to be with Mama. This usually entailed me sitting with her on the couch as she painted her nails, smoked her cigarettes, and gossiped on the phone to a background of whatever the Egyptian networks were airing on our TV. It was during one of these sensory sofa experiences that I witnessed the magic of Umm Kulthum.

As Mama was flicking through the channels, a powerful voice flowed out of the TV screen. The moment this happened, Mama put down the phone, and both our heads turned simultaneously. This sonorous voice had the depth and gravitas of a gargantuan black hole that nothing would escape. The vibrato of her chords felt more like a tremor, as if each note was sending the room into a seismic shock that grabbed your insides until you were crying without realising. And not only was her voice able to take up – even alter – space, but her presence was of a might that I’d only ever associated before with the force of Allah. A large woman, she stood rooted to the spot onstage, her hair towering above her in a perfectly constructed up-do, her ears enveloped by enormous oval diamonds, and as she sang each heartbreaking note, she wrung her hands together with all the intensity of a grieving mother.

‘Mama … who is that?’ I said. My voice came out whispering and faint, as though Umm Kulthum had sucked in its power to strengthen her own.

‘Hayatti (‘my life’), that’s Umm Kulthum: she was the most famous singer in the world.’

Mama explained how Umm Kulthum (1898–1975) – oddly, her name translates as ‘mother of the male elephant’ – was an Egyptian singer who had taken the Arab world by storm. She was the most notorious singer of her time, known for a voice so powerful that it would break microphones if she stood too close to them. ‘You see how far away the microphone is on the stage? That’s so it doesn’t break.’ Her performance on TV was transcendentally majestic, and the response of her audience would make a Gaga concert look like an episode of Countdown. I watched with fascination as grown Arab men, dressed in traditional Islamic gear, broke their patriarchal stoicism and wept in front of their wives, who themselves stood up and ululated at Umm Kulthum. This feminine deity had the power to crumble the strict gendered behavioural rules that governed our communities. A fuzzy, comforting feeling started to circulate in my bloodstream. Hope.

And so I lay my head on Mama’s silky lap, as her indigo-manicured hands brushed my hair with the delicacy of a feather. But as I closed my eyes, the velvety bass timbre of Umm Kulthum’s voice gradually became the shadowy echo of an Islamic call to prayer. The shift in mood woke me from my hypnagogic dozing, and I realised that it was the male voice of an Imam interrupting the TV broadcast, as happened five times a day on Muslim networks. I fell asleep with ease that night, thinking that even though I had missed my prayer that evening, my sofa time with both the elephant’s mother and my own was its own kind of religious experience.

Umm Kulthum was a matriarchal version of the Middle East I wished I knew more of. During Islam lessons, as our teachers reminded us of our inevitable damnation, I would close my eyes and think of Umm Kulthum, the true ruler of Arabia.

Part of Islam class involved learning verses in the Quran – surahs – off by heart, so that we could recite them during prayer. The importance of our knowing these by memory was impressed upon us with severity; we could be called at random to recite a surah in front of the class, and detention awaited us if we weren’t able to. I’ve had the fortune of a photographic memory my whole life, so was always able to have these surahs down. And learning an Umm Kulthum song was not dissimilar to learning an Islamic surah. Umm Kulthum’s songs were similar in form to Islamic prayer – they felt more like incantations with no fixed melody, were often thirty minutes long, and the concerts they resulted in were practically spaces of worship.

I asked my mother to buy me some Umm Kulthum CDs to play in my Discman – remember how even the slightest movement would jolt the music in those? – and her voice would hypnotise me until I fell asleep. Umm Kulthum chanting in my ear was an anaesthetic against DR. ABC, as if all the water in the River Nile ran through me, calming every one of my demons with its soporific embrace. And after my week with Umm Kulthum (the coming-of-age Arab sequel to Simon Curtis’s My Week with Marilyn?) I had learnt one of her fifteen-minute songs off by heart. When my father was away with work one week, I woke my mother up in the middle of the night and sang it to her note by note. With a smile that could thaw even Putin’s cold, dead heart, she watched my solo performance, and invited me back into bed with her once I had finished the song. This time, I was sure not to suggest we find ourselves a condom.

Holding onto Mama was the only way I could feel safe in a culture and faith that was really starting to scare me. The idea that we might ever be separated was a thought too horrifying to entertain, and I had to do whatever possible to keep her close. This took quite a literal turn when I became obsessed with grabbing my mother’s thighs. Whenever Mama and I were separated for longer than I was used to – if, say, it was my father whose car I was in for the weekend, or if she was late from work, and Islam class had been particularly terrifying that day – one of the first things I would do was beg to play with her thighs; more specifically, the bit that jiggled on the inside of her legs. This might sound slightly sordid, but I assure you it was completely innocent and utterly calming. When Mama emerged from her bedroom in one of her airy silk dressing gowns, she would sit on the couch to watch TV and smoke, allowing me, if no one else was there, to shake the loose bit of muscle on the inside of her thigh. I found its soft, buoyant texture deeply calming, as if her flesh were like a stress ball that could assuage any anxieties about my status as a sinner. Enveloping myself in her flesh was like burying my face in a silk pillow, a site of utter relaxation and peace from the terrors of the world outside. This activity was such a habitual remedy that when Mama could sense I was having a particularly bad day, she would open up her dressing gown and present her leg to me, the calming cushion to all my fears.

My father was clearly insecure about the unashamed preference I had for Mama, so one evening he took Ramy and me out to dinner for ‘a boys’ night’. I dreaded the evening to my core. Not because I didn’t want to be with them, but because I didn’t want to be apart from Mama. To be honest, I can’t remember much of the evening, except one quite alarming moment. As I excused myself to go to the toilet for the eighth time during the main course, I glimpsed the back of Mama’s head at a table in the smoking section of the restaurant (a smoking section – how vintage!). I felt suddenly elated that my time in the boys’ corner might be over sooner than I expected. I sprinted over to her and wrapped my arms around her neck as if we were two conjoined swans, burrowing myself into her hair. She jumped up in shock and turned around, severing me from her embrace as she did so. When I looked up at her … she was not my mother. She was just another Arab woman of my mother’s age (who potentially used the same hairdresser). I apologised, and drooped back to Baba and Ramy, embarrassed and upset. All I wanted was to be with Mama. I was all about my mother.

When it was just me and Mama, we created a pocket of ‘camp’ that only we were privy too. And it was in this special fortress that my love of performance was born. Now, Dubai and Bahrain had no culture of theatre – literally, none – and so my only access was a VHS tape of CATS on the West End that I received as a gift from some cousins in London. Until I was a teenager, I thought CATS was the pinnacle of Britain’s rich theatrical history. In truth, I believed that it was the only real bit of theatre that mattered. The first time I watched it, I was struck by the way male bodies were celebrated for their balletic curves, how they flaunted chic feline poses with utter pride, sitting side by side with the female performers without any shame. Now, my homosexual desires hadn’t quite taken shape when I was nine, and sexual desire was not a concept anyone articulated (in fact, one of my Muslim cousins only learnt that pregnancy was the result of sex, rather than marriage, at the age of sixteen); but the way that the musculature of the male performers was embellished by their spandex costumes sparked a feeling in me that had been lying dormant until that moment. All I have to do is get to London, and then I’ll be able to roll around with the spandex male cats. This became a definitive, serious ambition of mine, and I told my mother that I wanted to be a performer so that I could be in CATS in the West End one day.

Because Bahrain was so bereft of theatre, Mama turned into Miss Marple in her quest to find me a stage – no doubt my midnight impersonation of Umm Kulthum had convinced her of my chops. Her investigative efforts led her to discover that the British Council often held a Christmas pantomime as a way to preserve the cultural tradition. She called them up and explained that her young son was desperate for a part – but they said this was more a production for British citizens living in the Middle East. My brother and I had British passports; when we were yet unborn in our mother’s tummy, she and my dad had left Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq and we were born in Camden, thus granting us immediate British citizenship (Theresa May wasn’t in the Home Office yet). But then they told Mama that there were no roles for children in the pantomime. Undeterred, with the might of Umm Kulthum, and the tenacity of Erin Brockovich, Mama marched me into the British Council building the next day, and demanded they give me a part. But in this amateur production of Cinderella, there just wasn’t a part for a child. And so we were forced to drive home, tears running down my face, in a melodramatic tableau I wish had been filmed for posterity.

The next evening, as I mourned my non-existent pantomime career on the sofa in front of the TV, Mama came running from the kitchen, excitement all over her face as if she’d just won the lottery. ‘Amoura! Pick up the house phone – there’s someone on the line.’ Was it Baba, wanting to know if I’d join him and Ramy at the kebab shop for the umpteenth time? I had an excuse pursed on my lips, but I was caught completely by surprise – it was the director of the pantomime! He said he was so impressed with my determination to have a role in his production, that he had written one into the script for me – yes, you heard me: a role created specially for me.

To my knowledge, this character existed in no version of Cinderella throughout history, but I was ecstatic nonetheless. For I was going to be premiering the never-before-seen role of … the Fairy Godmother’s gecko. You heard it. A gecko. In Cinderella. My first foray into show business was to play a GECKO in a story that had nothing to do with geckos. Who knows, maybe the casting of a brown boy as an exotic reptile was rooted in systemic colonial structures – this was the British Council after all – but at the time, I felt nothing but victorious.

Rehearsals were after school every evening. I was the only child in the production, and because the gecko was – surprise! – not exactly integral to the plot, I really wasn’t needed much. However, I told Mama that I needed to be at every single rehearsal if I was going to do the part any justice. What is the world this gecko is inhabiting? Is this gecko scared of the Ugly Sisters too? Has the gecko been watching Cinderella’s abuse their whole life? – there were many urgent things to interrogate. In reality, all I had to do was stand in front of Cinderella as she got changed from rags to riches in the ball sequence. Effectively, I was a shield – a role so perfunctory that at the last minute they roped in my twin brother so that he could provide extra blockage. Despite my role as a wall divide, Mama sat with me in every single rehearsal as I soaked up the colourful world of pantomime and its diverse cast of performers.

Remember how, as a kid, a lot of your time was spent looking up at adults with a fiery curiosity? Remember how BIG every grown-up seemed? How each grown-up was like a speculative mirror to your future self, and you imagined yourself living the incredible lives you presumed they had? And there were some grown-ups who seemed different to any other grown-up you’d seen before – who took on a prophetic status, as if your paths crossing was an act of divine intervention? There were two such adults in the pantomime – and they were the grown men playing the Ugly Sisters. Both were from England, in their late thirties/early forties, and with hindsight I think they were a couple, but at the time I believed them to be best friends. From my minuscule height they seemed to have imposing, manly frames, yet they gestured with their hands as if they were flicking wands, oozing wit and comic flare – what we might term ‘camp’. ‘Were you in CATS?’ I asked them one evening with complete sincerity, at which they laughed from the belly, one of them commenting: ‘Darling, I wish.’ Yes, I wish too. We get each other.

During one dress rehearsal, I was completely blown away when both men came onto the stage in women’s clothing. I remember their costumes vividly; one of them had bright orange pigtails, radio-active fuchsia lips, and freckles dotted all over his face, while the other had a plum-toned up-do of a shape not dissimilar to Umm Kulthum’s. The former had what looked like a pink chequered apron flowing down his body, while the other was strapped into a purple corset and black thigh-high boots. With little conception of my gender or sexuality at this point, I can’t remember processing my own dysphoria or sexual orientation within what I was seeing – the overarching feeling I had was, ‘is this allowed?’ I looked around the room, seeing the rest of the cast laugh and celebrate both men in their feminine get-ups. The pair were melding the masculine and the feminine, transgressing both, relishing both, and there was nothing dangerous about it – all it brought into the room was a feeling of collective joy. Just as Umm Kulthum’s voice could apparently overcome audience gender divides, again I was witnessing the potential of femininity to alter social space. Rules and codes of behavioural conduct formed a major part of Islamic teachings, so the idea of a man transgressing his gender codes was not something I thought I’d ever see publicly in the Middle East. But here, in front of me, were men wearing women’s clothing, and the only reactions they provoked were ones of enjoyment. I was smiling goofily, and, as I turned to my mother, I could see that she too was enjoying the performance of the two infectious, loveable queens. Mama’s enjoying this too! Maybe not being a manly boy will be OK with Mama! It seemed that in our secret club, these other ways of being were tolerated – celebrated, even. Perhaps I had nothing to worry about.

But, as I would shortly learn, Mama’s and my bubble was going to burst. And in the next phase of my life, nothing could have prepared me for how sharp a turn Mama would take to stop me being different.

The first proper realisation I had of being gay was at the age of ten. I was at home watching TV when the cartoon of Robin Hood aired. And let me tell you: I crushed hard on Mr Hood (the cartoon fox, not the actual historical figure). Now I promise you I’m not into bestiality, but the arousal I experienced was an extension of the titillation I had felt for the men wearing spandex in CATS, only this time it was tangibly sexual. The cartoon character wore a remarkably progressive gender-queer T-shirt, which was long enough to cover his groin, but he wore it with no bottoms, and cinched at the waist with a River-Island type belt. The way the garment billowed around the character’s pelvis had me fixated, and I was desperate to know what lay underneath – to be frank, I was hungry for a bite of it (minus the fur, but definitely with the balls). His stud status was accentuated by muscular thighs and an ability to penetrate enemies with his bow and arrow, and, as I watched, I imagined myself by his side, a little damsel in distress who he would make it his mission to protect.

I knew that it wouldn’t be the best idea to verbalise my crush to anyone – but I needed to investigate my desires more closely. So when the whole house was asleep one night, I locked myself in the bathroom, got naked, and lay on the marble floor, imagining Robin Hood – yes, the cartoon fox – next to me. The texture of the cold floor against my sweaty torso created a tingling sensation, and the pitch-black midnight of the room made for a psycho-sensory experience. Pretty quickly, it felt like Mr Hood was next to me, and I started writhing around the floor, my aroused body fusing with the galactic space around me, as if the desire in my body poured through my skin and into Mr. Hood’s soul, which was totally consuming me. As the experience intensified, the more out-of-body it became, and I lost all sense of my physicality, floating in a foamy limbo of ecstasy, as if every atom of my being were being engulfed. The next thing I knew it was 7 a.m., and someone was knocking on the door. It was time for school.

It wasn’t long before we were warned about the perils of homosexuality at school. As a Muslim, you were already in a committed, non-negotiable relationship with Allah; the rules, according to our teacher, were that you could open this relationship if it was with a devout Muslim of the opposite gender. A Muslim man dating a non-Muslim woman? Eternal damnation. A Muslim man dating a man, period? Eternal damnation ad infinitum. The closer we got to puberty, the more insight we were given into what actually went down in hell. And it was in these lessons that feelings of terror and shame attached themselves like a bloodthirsty parasite to my sexuality.

It is worth noting that it’s not entirely clear whether the Quran actually condemns homosexuality. The only passages in which it seems to, in The Story of Lot, are ambiguous. In the story, Allah punishes the men of a city for their indecent sexual activities with male visitors. Yet it is not the homosexual act that is being denounced, but rather that the visitors were being raped. It is the way such Quranic passages have been interpreted by conservative Islamic scholars and lawmakers that has partly led to such institutional homophobia among Muslims.

So as I’ve explained, whether we ended up in hell depended on the points between our left and right shoulders – if those on the left exceeded those on the right, then hell it was:

But he whose balance [of good deeds] is found to be light, will have his home in a [bottomless] Pit. And what will explain to you what this is? A Fire blazing fiercely! (101:8–11)

Cute, right? The snag for me was that I was taught that homosexuality resulted in an automatic infinite number of sins, and no kind of good deed – not even curing cancer or solving climate change – could help compensate. But I only have a crush on Robin Hood THE FOX – the Quran doesn’t say anything about fancying foxes? I clutched onto this minuscule loophole of hope – I had to. For the punishments of hell were described to us with intimate detail. While water in heaven was a redemptive, cleansing element, in hell we’d be forced to drink and bathe in boiling water. ‘Close your eyes and imagine the heat on your skin and in your stomach,’ our teacher would tell us. With my eyes shut, I clung onto the lifebuoy that was DR. ABC – but it was no longer enough to stop my whole body from boiling. Another fabulous little treat in store for us was The Tree of Zaqqum, a deceptive piece of foliage whose fruit we’d be forced to eat. When I say ‘fruit’, I mean little devil heads disguised as fruit, which would mutilate our insides once ingested. And what to drink to wash off the horrific taste? Boiling water, of course. DR. ABC – what’s your cure for a shredded, incinerated gut? Nothing.

The intensity of hell’s punishments had a domino effect that debilitated DR. ABC’s capacity to hold off the terror, spreading around my brain like a wildfire that just couldn’t be controlled. And then came the final blow in our classroom tour of Satan’s lair: the overarching punishment of hell would be our regret that we hadn’t changed our behaviour on earth – that we lost Allah – coupled with the knowledge that nothing would placate Allah’s rage. We were stuck here for eternity, and it was entirely our fault. Eternal self-blame was Allah’s ultimate punishment, and it’s a feeling that has seeped into absolutely everything I experience.

To this day, every single time a traffic light goes red, I experience a pang of anxiety because I fear I’ve incited its fury. I’ve tried and tried to shirk this, but it is so engrained into my neurological make-up that I just can’t. Another road phenomenon that overwhelms me with guilt is when I press the ‘wait’ button before crossing a road; if there are no cars coming, I might decide to cross, but sometimes the traffic light then goes red, forcing a car to stop even though I’ve already crossed the road. I usually feel so bad when this happens that I have to mouth an ‘I’m sorry’ to the delayed driver every time. And, throughout my life, whenever I’ve had major doubts about Islam, one of the key thoughts that dissuades me from my scepticism is this: but just in case Allah is real, I should probably stay Muslim to avoid the not-so-glam time in Lucifer’s dungeon. This shadowy doubt, which I managed to stave off through times with my mother as a kid, became an all-consuming plague when I went from fancying cartoon foxes to actual boys.

The first boy I crushed on was none other than Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone – can you honestly tell me you didn’t when you were a kid? I was ten years old. I knew I was gay by this point. I wanted to cuddle Macaulay Culkin in bed, and had the intense urge to help him through his lonely sorrow in the film. I wanted to support him, to be his partner, to lie naked with him and to feel supported by him. Perhaps it was also because I was starting to feel lonely in the Middle East, and I thought that he and I had a lot in common. When I realised the intensity of my desire, I was terrified by the religious implications of it. What I really wanted to do was cuddle up to Mama and have her and Umm Kulthum sing me to sleep, telling me it was going to be OK; but the fear was all-consuming, and it had to come out of me, for the thought was munching at my insides like a flesh-eating virus. And so I came out with it when we were on a family vacation in London.

Let me set the scene: we were visiting my dad’s old childhood friend who worked in the UK (let’s call him Majid); unlike most Arab men his age I’d met, he had never been married, and was dating a raucous and infectiously free-spirited English woman (let’s call her Lily). They were the first ‘interracial’ couple I’d ever seen, and much like the panto dames fusing genders, this relationship seemed to bridge cultures, a further sign that there were other models of behaviour outside of what I’d grown up with. Lily had a gay friend (let’s call him Billy) who was a fleeting but powerful presence. With bright red hair and toned arms, Billy wore tank tops and denim hot pants, and spoke with a melodic Liverpudlian accent that made every room he was in feel like a scene in an uplifting musical. My interactions with him were slight; when he came over to Majid’s house in Islington, I stayed quiet and read my Jacqueline Wilson ‘teenage-girl’ books in the corner (they were my favourite), attempting a surreptitious peep over the pages every now and then. I’d never seen a man so effeminate owning space like he did, and as he and the adults – my parents included – chatted over dinner and drinks, he splayed his lean legs over a spare chair, recalibrating the entire rhythm of the room to his own pace. Billy was the mistress of ceremonies in this house now. Lily referred to Billy with a ‘she’ pronoun throughout the night, and this flexible attitude towards gender seemed entirely accepted, just as it had been with the dames in pantomime. Perhaps this is only OK in London (or the British Council)? When I looked at my mother, she also seemed to hang on Billy’s every word, and she laughed from the belly in a way that told me she was genuinely delighted by his company. The next day, they even went clothes shopping together, for crying out loud.

The way in which Billy was accepted by everyone – particularly Mama – gave me the confidence that confessing my love for Macaulay Culkin might even be celebrated, despite what I knew about homosexuality from Islam. So as I was having lunch with Majid at a restaurant one afternoon, I said ‘I’m in love with Macaulay Culkin.’ Majid, who was sipping a whisky and Coca Cola, slowly put down the tumbler.

‘Oh yeah,’ he said nonchalantly. ‘You love him in the film? Because he’s a good actor?’

‘No! I’m in love with him. I want to marry him.’

Majid picked up his drink and took a big gulp, then he told me to finish my food. His thick eyebrows furrowed as he watched me slurp my spaghetti. The silence was a bit unnerving, but I interpreted his gaze as somewhat benevolent – maybe he feels the same because he also fancies a white person? As I found out later that evening, that was definitely not what he was feeling.

As I thumbed a new Jacqueline Wilson book in the guest room that evening, Majid called my name from the living room downstairs. I presumed dinner was ready. But after descending the staircase, I entered a room that was eerily quiet. The TV was off, no food was laid out on the tables, and Majid, my father, and mother were sitting neatly on the living-room couch, like Olympic gymnastics judges, ordered and unreadable. On the sofa next to them sat my brother, Majid’s fifteen-year-old son and marijuana-enthusiast, and Lily, who had her eyes glued to the floor. Majid then spoke: ‘Is everyone OK if we go out for dinner tonight? There’s a tasty Lebanese place near us.’ Phew. This is just a menu meeting. General mutters of agreement spread around the room. ‘But before we go … Amrou, do you want to tell everyone what you told me today?’ Mama sat up straight, the fact that I might have confided something to Majid without telling her first clearly upsetting to her. Mama and I didn’t keep secrets from each other. But on a cultural level, the fact that I said something to a family friend without first checking it with my parents was also very taboo; where we’re from, family units are more like clans. You are less an individual, and more one puzzle-piece of the collective familial-self, where everything that you say or do reflects the entirety of the family tribe. If any member of the family unit displays individual ways of thinking and behaving, the entire clan must come together to control, exile or destroy the offender.

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ I said. My mother’s eyes were giving out a hot glare, as if thin infrared lasers were beaming out and trying to penetrate my subconscious.

‘About Macaulay Culkin?’ Holy Shitting Fucking Christ on his Fucking Crucifix.

I looked around the room and assessed the perilous situation. Maybe I should just tell everyone I’m in love with Macaulay Culkin? I mean, we are in London – the home of spandex male cats, the place where pantomime was born – and look at Lily! She parties in St Tropez and wears revealing clothes – and she’s white and dating an Arab! – and WAIT A SECOND, what about Billy, the gay superhero who my mother LOVES?! Maybe it won’t be so bad? What if Islam doesn’t exist in this part of North London? OK – I’m going to go for it. What could possibly go wrong?!

‘I told Majid that I’m in love with Macaulay Culkin. One day, I want to marry him.’ My dad, who avoids emotion like it’s a skunk’s fart, looked almost fatigued by the news, as if it being raised was an utter imposition to his dinner schedule. Ramy started playing on his Game Boy – I would have done the same to be honest – while my mother looked stunned, tears brimming in her eyes, as if this was the most shocking, dangerous thing she had ever heard.

Majid looked to his son (let’s call him Hassan), who had clearly been briefed on this Iraqi episode of Jeremy Kyle. ‘Listen dude,’ Hassan chimed in, ‘just ’coz you think a guy is cool and you want to hang out with him, doesn’t mean you’re in love with him. Dudes can’t be in love with other dudes, it’s haram.’

‘Exactly,’ said Majid, with a self-satisfied grimace that even today makes me want to go back in time and whack his face with a slab of raw tuna. ‘You just want Macaulay Culkin to be your best friend. You didn’t know what you were saying – you were being stupid.’