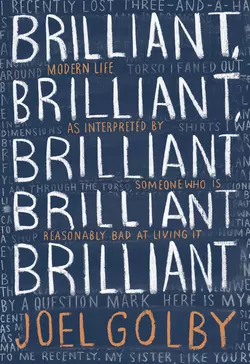

Brilliant, Brilliant, Brilliant Brilliant Brilliant

Joel Golby

A collection of full-throated appreciations, withering assessments, and hard-won lessons by the popular journalist.There are a few things you need to know about Joel Golby. Both his parents are dead. His dad was an alcoholic. He himself has a complicated relationship with alcohol. He once went to karaoke three times in five days. He will always beat you at Monopoly, and he will always cheat.Joel makes a name for himself as a journalist who brings us distinguished articles such as ‘A Man Shits On A Plane So Hard It Has To Turn Around And Come Back Again’, but that says more about us than him. In his first book, Brilliant, Brilliant, Brilliant Brilliant Brilliant Joel writes about important stuff (death, alcohol, loss, friendship) and unimportant stuff (Saudi Arabian Camel Pageants, a watertight ranking of the Rocky films, Monopoly), always with the soft punch of a lesson tucked within.Golby’s sharp, evocative prose thrives on reality and honesty that is gut-wrenchingly close to the bone, and laced with a copious dose of dark humour. Who is this book for? It is for everyone, but mainly people who are as lost and confused as Joel and just want to have a good laugh about it.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_8e24657e-4474-50bb-ac3e-05bf8c22ed9a)

Mudlark

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by Mudlark 2019

FIRST EDITION

Text © Joel Golby 2019

Cover and chapter illustrations © Bill Bragg 2019

Cover layout design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Joel Golby asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008265403

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008265434

Version 2019-01-31

DEDICATION (#ulink_b85670c2-7129-5285-b4ba-69e615162f3e)

This book is dedicated to Sacha Fernando,

who gave me an iPad once. This is the deal.

We are even now.

CONTENTS

COVER (#ud62ab188-3ddb-5322-b924-a21a2dc9c745)

TITLE PAGE (#u467a46b0-c0cc-5f3f-93d1-77c6bade7d02)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_1b5f8823-47d5-5371-b789-63abe97a0541)

DEDICATION (#ulink_c03ad366-c4c0-5e25-8977-c2828a1bcf64)

THINGS YOU ONLY KNOW IF BOTH YOUR PARENTS ARE DEAD (#ulink_b580642a-e092-5a26-8c5c-de8593c14fec)

THE MURDERER WHO CAME TO TEA (#ulink_56785e52-da96-5436-a7a0-23cf61d400fe)

TWITCH.TV (#ulink_2576c37d-cd45-525a-99ad-8b1f6708c310)

RIBS (#ulink_ab5bac72-5fc3-5c90-8b12-aaf65ac77f0a)

LIST OF FEARS: A LIST (#ulink_efbe1c49-29ac-5fe8-a1fb-226553ead914)

ADULT SIZE LARGE (#ulink_b5936965-27c1-575c-a002-9b62d713d06c)

24 STORIES FROM THE MIDDLE OF THE DESERT (#ulink_e0b0e8b9-0a23-50bb-823c-9a8e5b1937f1)

SWOOSH (#litres_trial_promo)

PCM (PER CALENDAR MONTH) (#litres_trial_promo)

HOT SAUCE CAPITALISM (#litres_trial_promo)

WAYNE ROONEY IS THE MAIN ANTAGONIST OF MY LIFE (#litres_trial_promo)

THAT TIME I INVENTED SITTING DOWN (#litres_trial_promo)

I HAVE THE MONOPOLY (#litres_trial_promo)

HALLOWE’EN ’96 (#litres_trial_promo)

I WILL NEVER BE AS TOUGH AS PITBULL (#litres_trial_promo)

THE TAO OF DOG PISS (#litres_trial_promo)

WHY ROCKY IV IS THE GREATEST EVER ROCKY FILM AND THEREFORE BY EXTENSION THE GREATEST FILM IN HISTORY: AN IMAGINARY TED TALK (#litres_trial_promo)

EYEMASK: A REVIEW (#litres_trial_promo)

I WENT TO BARCELONA AND ALL I GOT WAS THIS HANDJOB FROM A SEX ROBOT (#litres_trial_promo)

HEY: AM I A LEATHER JACKET GUY? (#litres_trial_promo)

ALL THE FIGHTS I’VE LOST (#litres_trial_promo)

AT HOME, IN THE RAIN (#litres_trial_promo)

MOUSTACHE RIDER (#litres_trial_promo)

RUNNING ALONGSIDE THE WAGON (#litres_trial_promo)

FOOTNOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_16c96bd6-3407-58ce-a00c-50d79dad3877)

My parents are dead and all I can think about is how to sell this house that they left behind. It’s me and my sister in a room without curtains – we had to take down the curtains to decorate, so the sunlight is pooling in, and nothing looks more naked than a house stripped and moved around when the person who lived in it died, and no more is that so than in the cold, white light of the day – and we are painting every wall in this fucking place white, because my mother went decoratively insane before she died and discovered the Dulux colour-match service and went absolutely ham on that thing. And we’ve had three separate estate agents come in, with blazers that bunch around the buttons and a clipboard or iPad, and a special laser tool to measure the size of every room, surveying the corpse with cool detachment and weighing each pound of flesh for gold, and they say – all of them, in turn – they say:

‘It’s going to be very hard,’ they say, ‘to sell a house with a pink kitchen.’ Which I admit is true.

My parents are dead and the kitchen is pink and the dining room, where she always used to sit, each morning, with a pale cup of tea and some cigarettes, is a sort of terracotta orange, with a gold line of paint stencilled around it at approximately head height. The front room is a looming maroon, a deep dark red the kind you haven’t seen since a Twin Peaks hell scene, and upstairs the spare room is brown with bronze swirls crawling up the wall in the vague approximation of a plant. The house was always her project: whenever I would go home, she would explain with extravagant hand gestures, not moving from that dining room chair, smoke spiralling through the air, what the hallway would look like when she was done, and what she’d really like to do with my room – now a spare room – and what to do with the spare room that wasn’t my room, if she had the money, and then ideally the garden, and then of course the kitchen, but—

And then she was dead and we had to paint over it all white to sell it.

My parents are dead and now I don’t know where to spend Christmas. Like, can I go to Dad’s? No. Dad’s is out because Dad now resides on a golf course in Wolverhampton, a golf course that has no official idea about this because when we sprinkled him – a grey, dreary day in February, the first of his birthdays without him – the family neglected entirely to go through any legitimate ash-sprinkling channels, which is why we had to take two cars and kind of sneak down this side road and park nearby, hop through thick grass on a hill, then crouch among thin, leafless trees, passing around the big ice cream tub that had Dad in it, sprinkling that, and so of course he went everywhere, big billowing clouds of Dad all around us, sticking to boots and trousers, clots of grey Dad on the ground. So: can’t go there.

Mum’s is out, because Mum is a slick of grey dust long since lost to the waves who was last seen poured into a shallow hole on a beach in Filey. This is another thing they never tell you about death: how, logistically, getting rid of two-and-a-half kilos of ground Mum is a nightmare. Firstly it is never in an urn: the crematorium always presents it to you in a practical-looking if grey-around-the-edges plastic tub, with a plastic bag inside it as a rudimentary spill insurance. Then you have to get the old band together again, i.e. get all of the family to one chosen place to reverently pour dust on the ground. My sister did the hard work of organising this one, getting my two cousins, aunt, my cousin’s two children and his dog, my cousin’s son’s girlfriend who I don’t think ever met my mum so why she’d want to come to a beach in Filey to dispose of her I don’t know but by then we really needed to up the numbers, a couple of Mum’s old friends and also me to a beach in eastern England, the sky so white it was grey, not a scrap of sun, not a scrap of it, and we spent two hours in Filey slowly walking down to the beach, digging a small hole, dumping the ashes, finding a bin for the ashes urn (someone had to carry that thing for half a mile, swear to god), then fish and chips and home. Trying to think if I had an emotion that day. Don’t think I had an emotion.

So anyway yeah: Christmas is tricky.

My parents are dead and my dad died when I was 15 and my mum followed suit ten years later. I had ‘completed the set’ by the age of 25, and they managed to split up somewhere in the midst of it, too: they never married but they argued like they had, separating when I was 13. ‘I am an orphan!’ I would say to people, as a joke, and they would go, ‘you’re not an orphan, don’t be sil—’ then realise that yes, actually, I am, and just because I’m not some grubby-faced Oliver-style orphan, flat cap and itchy tweed asking a man for oats, doesn’t mean I’m not an orphan. I’m an orphan. Look it up. I am the dictionary definition of an orphan.

My parents are dead and my dad, especially, has fucked me over because he died before he could teach me how to shave. This is what dads are supposed to do, but he has been dust for four years before puberty kicks in enough to sprinkle me with whispers of neck hair, a formative moustache, general testosterone, so I had to teach myself to do it when I was in my first year at uni. This, for whatever reason, causes me enough shame for me to entirely lose my mind about it: I go to an out-of-town pharmacy to buy a razor and shave gel in secret (for some reason I am obsessed with the idea that someone will see me perusing the shaving gel aisle and go ‘HA!’ and point – there is a whole group of people I half-know with them, in this fantasy, and they all come round the corner to point and laugh at me, ‘HA!’ they are saying, ‘HE DOESN’T KNOW HOW TO SHAVE!’), and I decide to discreetly do a practice shave – on my thigh, where, even in shorts, nobody will know I have done it – in my room.

So here I am with a wad of printed out ‘how to shave’ instructions from wikiHow, and a jug of warm water for rinsing, and a towel, and the door is double-locked, and I have shaved my left thigh entirely, entirely nude. It’s horrible: eerie, actually, too smooth, weak and fragile to the touch, and so immediately after I am done have that sort of dark, grim, post-orgasm feeling of dirty regret: I had a pink, nude thigh and a jug of lukewarm hair water and a hollow feeling inside my body. The warm hair water is a problem – I cannot sprint to the shared bathroom to dispose of it in case the same crowd is there, pointing and laughing, calling me ‘Jug Boy’ or ‘Baby Thigh’ – and so, in what is easily my third or fourth moment of sheer madness in this entire episode, throw the water jug out of the window. The person in the flat below – a pathological smoker, who I think actually was probably smoking out of the window at the exact moment I threw a load of hair water out of it – starts immediately thumping on the ceiling, so I cower on the floor near my bed and stay there, still and silent, for 15 minutes in case anyone comes to my room. It’s there – trouserless, afraid, silent, and with one perfectly shaved pink thigh – that I thought: this is probably a low point, in my life. I entirely blame my father for this happening.

I don’t know: a small part of me feels cheated, I suppose. My parents were old when they had me – Dad, who already had my sister from another marriage, was 42; Mum, a first-timer at 38 – but still, when you sign up to push a baby out of your body and nurture it to adulthood, you are in my opinion signing an invisible contract: I am going to live long enough to see this one through so it can learn to live without me before it has to. It would have been nice for someone to teach me how to shave, or what an ISA is, or how many carbohydrates I should be eating (as close to zero as possible!) before they died.

My parents are dead and the cats are going crazy about it, lost in what’s left of the house. The cats are brothers, Boz and Jez, big beefy thickset tabbies with loud mouths and who lean into tickles ear-first, great cats, wonderful boys, starting to creak a little as we’ve had them since I was 11 but otherwise great, good boys. They are staying with some friends of my mum’s since the death thing happened to her and the friends – a couple – are sending us mixed messages about them, about how happy the animals are and the humans too. The husband is deeply in love with Boz and Jez: they sit on him, he tells us, they are very settled, they can stay with us as long as you need, if you are thinking of putting them up for adoption, he says, he is interested. The wife is calling us at odd times in the afternoon to tell us that actually the cats are deeply unhappy and we need to come get them, stat. Listen, I like being courtside on a slow-moving divorce just as much as anyone but right now, while I’m trying to pick funeral flowers out, it’s less than ideal, so my sister decides to take the cats home to London to live the most luxe life a cat can possibly live in the two or so years they have left. When we take Jez, in a cat box, to the train station, it’s the most he’s ever travelled in his life. Do you know when a cat is really distressed – like, really, really freaked out – they pant? Honestly, it’s fucking crazy. It sounds like a werewolf transformation scene in an especially bogus eighties movie. This cat is panting and panting and panting. The noises coming out of this box, my god. Anyway, long story short: we get on the train, sit at a four-seater table, and then Jez just immediately panic-shits everywhere. Just everywhere. Jemma has to take him into a train bathroom and clean him up with wet wipes like a baby. Boz is chill throughout.

My parents are dead and my sister has gone back to London for the weekend because ‘this fucking shitheap fucking town is driving me deranged’ (my words, not hers) (my sister did NOT say this) and so I am left, alone here, with the echoing floors and the still bristling ashtrays and my mum’s phonebook, carefully handwritten and overwritten and rewritten, years of house moves and name changes and marriages and divorce, with the names and numbers of all her families and friends. And it’s me, my turn – my sister did this when my dad died, it is my turn to do this now – it is my turn to call everyone and tell them she is dead. The first person I call is my mum’s best friend, Teresa, the best woman in the world, the woman who still even now sends me Christmas cards with ‘NOT 2B OPENED B4 24/12/2017’ written on them, mum’s one best friend throughout her life, the one friend she loved throughout it all, decades she has known her, Teresa, decades she has known me, she has seen my dick as a baby and seen me have tantrums as a teenager and seen me grow, sort of, into an adult, and she is driving when she picks up, it sounds like, on the hands-free, and briefly she is pleased to hear from me because I’ve literally never phoned her in my life, she says it so surprised, so genuine, ‘oh hi’ she says, and ‘how are you?’ and then I have to tell her, and the words feel dry in my mouth because I haven’t ever said them yet, ‘Terri,’ I say. ‘It’s mum. She’s dead.’ And Terri goes no, no.

That’s all I remember: no, no.

Sometimes when I try and sleep I close my eyes and I can still hear it exactly how she said it: no, no.

With her voice kind of breaking halfway through. And there’s a pause, and she says, ‘I’ll have to call you back’ and I say yes, and then I just sort of sit there, holding the phone, just sat in the armchair, looking.

And that is definitely the worst thing I’ve ever had to do in my entire life.

And for the rest of the friends we just announce it via a Facebook status, because who can do that, really. Who can do that to themselves.

* * *

My parents are dead and I am drunk, so much drunker than everyone else around me, so drunk for a Wednesday, and it’s so obvious, being that drunk, such an obvious way of coping, but here I am. My sister is in London still and the cats are at the friends’ house and all my mates are at work and so it’s just me, in the house, going crazy at the way this place seems to have deformed and changed in the time I’ve been here, the very shape of the rooms seem different, too quiet, and I try and start the day normally – I have opened my laptop and started a game of Football Manager and I am convinced I can pull Queen’s Park Rangers up out of the Championship and into the path of glory, and a lot of that glory depends on the form of a misfiring Bobby Zamora – and but it’s 1 p.m. now and I’m bored and still not dressed yet and, long story short, lunch is one ham and coleslaw bap, one small bag of Mini Cheddars, and a fantastic amount of beer and bourbon drunk alone. I have just discovered the boilermaker – a bottle of American beer chased with a greasy shot of bourbon – and have decided it is fantastic. By 5 p.m. QPR have been relegated because I’m trying to play five men up front, and I am roaring.

So we’re out tonight, everyone out tonight, even though it’s a Wednesday and not typically an out-tonight kind of night, but because I have requested it and because my mum is dead everyone is going along with it so whatever, and when I arrive at the same pub we all go to –Wetherspoons; shout out to! – everyone is there slowly sipping their first pints and someone turns to me with a note of surprise in their voice and says Joel, they say, you’re so drunk.

And I say: hell fuck shit fuck yeah I’m drunk! And I order another two boilermakers (two.). And I would say this activity continues for roughly three more years.

My parents are dead and the fridge is, too. I cannot believe this: the day my mother died the fridge in her house also decided to expire, so it’s just this lifeless white box and we have to keep milk for tea in this foil-lined freezer bag on the side, and let’s be honest about this system: it does not actually work. Already, my health has deteriorated drastically as a result of my mother’s death – two weeks alone in a house with no fridge and no store cupboard reserves has left me stringing meals together from whatever I can buy that day from the nearest decent supermarket a mile away, microwave friendly a plus, or whatever I can muster in desperation at whatever time I wake up from the local corner shop (one dreary grey Sunday, with no other shops open and nowhere to turn, I end up going to the Spar and my dietary intake for the day was 1 x entire thing of fromage frais, 1 x entire packet of Cheesestrings, 1 x apple, 1 x pack of popular prawn-and-maize snack Skips, no other vitamins or minerals). I am eating in pubs, a lot. I am eating a lot of sugared cereals. I feel like hell. I feel like garbage. I would pay up to £1,000 for someone else’s mum to cook me a meal and tell me it’s okay.

My parents are dead and I don’t know what my dad’s face looks like any more. I know what my mum’s face looks like: I can look directly in a mirror for that, imagine myself with a grey chin-length bob and a fag on the go, yelling at the tennis, by which I mean to say I have my mother’s exact face (my sister, too, has her mother’s exact face: our shared dad had weak genes, clearly). But his face … not so much. Every early January I am vaguely reminded of his death – he died on the fourth, early in the year, which obviously made it double-sad because that was so close to Christmas (see ibid., re: already being very marred), which marred the occasion somewhat. The last Christmas present he ever got me, since you ask, was a Dreamcast console, which I discovered ten years later when we were clearing out Mum’s house, and when I found it I just squatted on the floor and held it and looked into the middle distance and Thought A Lot About Stuff, which you do a fair amount of when both your parents are dead – and I realised with a jolt this year that this January marks 15 Januaries without him, equal in number to the 15 Januaries I had with, meaning I have now spent more of my life without a father than with. And those memories are becoming blurry now – the things he did, the way his voice sounded, gentle but melodic, sort of, the way he smelled so bad because he was a smoker, and the way the car smelled so, so bad because he was a smoker, and all the smoke – but his face. His face. I just can’t picture it. Sometimes I go to my sister’s house and idly flick my eyes over at a bookshelf and there, buried among knick-knacks and shells and Asian-looking scrolls from her time in Malaysia and in amongst all that crap, boom: there’s a perfect sharp photo portrait of my dad, the one I took when I was about eight, when, after school, I went with him to the local college nearby, where he knew the photography lecturer who let him use the dark room there; and there, in the empty hours of the evening, he’d sit and make a shallow pool of chemicals slowly splash, and, alchemy-like, black-and-white photos would emerge; and I would spend most of these times bored out of my mind, or playing with something – a Gameboy, an off-brand single-note Thunderbirds-themed electronic game, a Tazo – until, once, he set the camera up for me – steadied it on the tripod, gauged the aperture and ISO, stood me on a box and trailed a shutter release wire down to me, then sat in front of the camera, click. And then he went to the back and developed it – out of the canister, into the pool, slick paper pushed into the bath with tongs – and then, what seemed like hours later, there: the last photo of him ever taken. I had just eaten a Kinder Egg and had chocolatey fingers, and there, in my excitement, I grabbed the photo, smudging the back – my tiny fingerprints still mark the back of it – and I remember the photo. I remember the chemical smell. I remember the Kinder Egg and the slow, short walk home, pink sun setting in a red sky. I remember the Hoover repair shop we always had to walk past on the way there, and the name of the photography lecturer who gave Dad a key to his studio, and I remember the winding cast-iron staircase I used to sit on and play with. But I do not remember his face.

My parents are dead and all I can think back to is the Christmas I figured Santa wasn’t real. Because I kind of knew – you always know, before you know; children are obsessed with Santa, entirely, and strive to solve the puzzle of him even though they don’t truly want the answer, and as a result are constantly searching for clues as to his existence or non-existence; and plus also a bigger boy two years above me in school called Daniel told me, and I mostly believed him – but it is cold and the night is sharp and jet-black, and I’m sat huddled on a bench at the train station with my dad, hands both in our pockets, waiting on Christmas Eve for my sister. She’d been off living in London, nineties London, which I can only assume meant taking acid before cutting your own hair a lot and literally nothing else, and the train is delayed or we are early or whatever and my dad is making small talk asking me what I wanted for Christmas. He was always very clear-eyed, when my sister was coming to stay: rare, half-yearly trips, just a weekend here or there, and he would always be on his A-game for it, make sure he was sober and sparkling, and he nestled in near and said, And So What Do You Want Santa To Bring You For Christmas.

And I don’t really know, I say.

What If He Bought You A Camera?, my dad asks. And I say—

—and this haunts me, every time i think of it, in the many years since; if i could take back one moment and swallow it away, push it all in my mouth like a piece of paper and chomp it down and swallow it, take it all back, i would, but i am stuck with the scar instead; and it will come to me, in dark blue-grey nights when i can’t sleep and when i’m walking thru supermarkets and when i’m on my commute and when i’m just minding my own business on the sofa, and it will come to me in the high moments as well as the low, and it will knock all the air out of me all over again, and i go—

—‘Ugh. No.’ And my dad turns to look away and says, Okay.

And so of course the next day I open a carefully wrapped shoebox with, inside it, a small, pristine, second-hand camera. And the note from Santa is in my dad’s handwriting. And he says he hopes I like my present. And that is how I learned that Santa wasn’t real.

(I just wanted a Megadrive, that’s all. I just wanted a Megadrive.)

My parents are dead and do you ever think about the moment of death? The actual moment of death? Not your physical body collapsing beneath you, or your liver finally failing in its liver hole, or anything biological, physical, like that: do you ever think, of that last second of life, as the air eases out of your lungs? Do you ever think what it is like to be in that moment, and know it is the end? There is no peace there. That is a moment of sheer horror. You know that your body has failed you and you are trapped, for the rest of your life, in the prison of it. And then the edges grow blurry, and the words begin to fade, and the light grows pale and the darkness comes to replace it. And then— just as you never knew you were born. You die.

My dad is dead and we are at his flat, clearing out his things. It’s a small flat, a stubby hallway that opens out into a sort of double room and, behind it, an equally sized living area; off that, a box-shaped kitchen, and from the hallway, a small bathroom. I am telling you this because I know the flat inside-out, as I did then and I do now, because I used to stay here every other Friday until I didn’t, and since I’ve been here last it has filled with another layer of accoutrements. In the last couple of years since my parents split and he moved here, my dad has mainly preoccupied himself with drinking, and with stumbling into town a couple miles to do a loop of all the charity shops, on the search for geegaws and trinkets on a rhyme and reason known only to himself. You look at this flat, and any interior designer will tell you there’s no overarching theme here, no throughline to the knick-knacks – here, for some reason, is a brass bugle; here a small tin car; some wooden owls; a tiny pot statue of an elephant; here is a deck of cards inside a decorative box; here is a toby jug with a monstrous face. We pick through the crap (an awful lot thereof) and chuck it; the few items worth keeping are distributed amongst us, for memory’s sake. All I have to remember my dad by is a cowboy coffee pot, a fist-sized wooden ball studded with faux ivory, a pair of binoculars with an honest-to-god swastika on it, and a cast-iron skillet.

And then a curious thing happens, which is: Dad’s best friend turns up. Only none of us have ever met this best friend, ever. And he says it – ‘I was your dad’s best friend’ – and he explains, through the tears, this old wizened toothless man in a flat cap and a wrinkled face contorting with emotion, that he used to come over, with the dog – the dog, he gestures to, straining on its leash – and they would talk about things, about the wind and the day and the lay of the land, and then he – and this man is gulping, crying, with an emotion none of us, dead at the nerves, have felt for days – and he just wanted to say – I— found— him— – gesturing to the hallway he was found back-down and grey in, and – he— was— a— good— man— – and all I am thinking here is:

Who the fuck is this dude?

My parents are dead, or at least my dad is, and my mum and I don’t really talk much anymore but whenever I see her she demands I play Scrabble with her, because she is very good at Scrabble and enjoys beating me at it a lot. I do not have the exact statistics to hand but her unbeaten run at Scrabble goes back at least 15 years, because my mum is the kind of Scrabble dickhead who plays ‘XI’ in the corner on a triple word score like three moves from the end, conjuring 48 points out of thin air, and also a lot of the times we played I was a literal child, but whatever. The point is I am 21 now and have a degree and I have won by 12 points and this information has shocked her to the core. ‘No,’ she says, touching each tile, counting and recounting, the entire board, top to bottom. ‘No, it’s not possible.’ And she looks up at me across the table—

—and i remember that the only other board game we have ever played together was the night my dad died, when we just stayed up in silence on silence playing cards, until the cold part of the night turned something blue then grey then red as the sun came up in the morning, and she said ‘well’, and ‘I guess we best get on with it’, and she rang work to tell them she wouldn’t be in today, and rang school to say i wouldn’t be coming in today and didn’t know when i would be in ever again (it would be six weeks until i went back there)—

—she looks up at me and goes, ‘You cheated. You must have cheated.’ And the torch is passed between the generations. And I am the family champion of Scrabble now.

* * *

My parents are dead and I am trying to buy a beer basket online. A beer basket is a beautifully packaged wicker basket with beer in it. Ribbons, that sort of thing. An outer cellophane shell. Inside, to cushion the beers, is that sort of cardboard shred that hamsters have in their cages sometimes. It is a nice gift. I am buying it for my neighbour because he found my mum’s lifeless body on the floor of her bedroom and had to call an ambulance about it.

Mum had cancer, so we sort of knew this was coming, just not when. There are two kinds of death of your parents: ones you know about, and ones you don’t. I have to tell you some information about this that is going to make me extremely sound like I believe in horoscopes, now. Makes me sound like I have some Real Opinions About Chi. Like I have written a letter to the government before about the medicinal power of weed. This is what I am going to sound like right now:

Both times, when I got the call that my parents were dead, I already knew.

When we got the call about my dad, I was 15 and asleep, and the phone rang about midnight, 1 a.m., and a phone ringing at 1 a.m. is literally never good news, so I sort of swum awake and watched the yellow light of the hallway hum and blur, and heard distantly the sort of wobbling sound of my mum’s voice through many walls and a stairwell, and even though he wasn’t sick or anything I just knew, clunk of dread in the ol’ bottom of the stomach, and then my mum came and sat on the edge of my bed and said ‘It’s your dad, Joe—’ my family call me Joe and I hate it ‘— it’s your dad, Joe, he’s gone,’ and I just. I dunno. I cried so much I yelled.

And then when my mum died ten years later, again I remember such clear weird little details of it: I was out drinking the night before and woke up in the most drunk sleep pose ever (entirely face down, face entirely enveloped by the pillow, and surrounded by a tacky pool of your own saliva, and honestly sleeping for six hours in that position I don’t know how I’m not the dead one) and the first thing I did was look at my phone because I am a millennial and I remember it being early, even for me – in the 6 a.m. hour, still, an hour I am incredibly unfamiliar with – and I had three missed calls from my sister and so I knew already what that means, and I called her quickly – still face down, somehow, I did not turn over for this phone call – and she said ‘Yeah it’s your mum she’s—’ – and a little pause – ‘—she’s gone, mate’, and I remember saying ‘okay’ and crying exactly one tear – such a pathological number of tears, it was out of my left eye and I remember it dropping with a soft thump onto the pillow beneath me – and I said ‘okay,’ and then, ‘what can I do?’

And it turns out one of the major things I can do is buy a ‘sorry you had to find my mum dead!’ beer basket for the neighbour. I am searching online for somewhere that delivers next day, and I cannot decide which beer basket seems more appropriate – the £35 version, eight craft beers and one tube of salted snacks, or the £55 version, all that and more? I am torn because obviously finding an actual corpse is probably quite a bad shock but also I am poor and 25 and my parents are dead and now I’m the only one left to provide for me and also I have a funeral to pay for and £55 for some beer and some ribbon is a lot. I spend like 15 minutes hovering the mouse between the £35 option and the £55 one. What, truly, is the price we put on the act of finding our mother dead in her bedroom on a mild June morning? I sigh and I click. It turns out it is £55.

My parents are dead and so I can tell you from experience that literally nobody alive knows what songs you want playing at your funeral, so if this is important to you then put some sort of system in place now, because here’s what happened with my dad—

‘What … does anyone know what music Dad liked?’

‘What CDs does he have in his house?’

‘He literally has one CD and it’s Eric Clapton’s Greatest Hits.’

[Extremely tedious half-hour while everyone tries to remember out loud a single instance of them seeing my dad enjoy a song]

‘I think he liked jazz so let’s bang some Miles Davis while we lower him into the pit.’

‘Cool.’

And with my mum—

‘This again. What’s in the CD pile?’

‘Tom Jones and Cerys Matthews from Catatonia, Baby It’s Cold Outside CD single.’

‘Inappropriate.’

‘Jiggerypipery, the self-titled album by Jiggerypipery, who are a local tour band who make what the back of the CD describes as “fun bagpipe music”.’

‘A hard no.’

‘And U2, The Joshua Tree, on tape cassette.’

‘I do not understand how someone can live sixty plus years and this is all they have to show for it.’

We ended up playing the soundtrack from the musical Sarafina! for reasons I cannot recall now. For the record, I see my funeral as the only time I can force my friends to sit and endure my music tastes – the AUX chord is always snatched away from me at parties because obscure lyric-less drone music does not exactly get the vibe popping, so I literally have to wait until I die to take it – and so I want Ratatat’s Germany to Germany/Spanish Armada/Cherry movement from the first album, Rome from their fifth album, then whichever 14-minute-long Fuck Buttons song is in my Spotify most played library when I die. Follow these instructions to the letter or I shall haunt you all forever.

My parents are dead and suddenly the home I grew up in has shifted, imperceptibly enough to feel alien, to feel like a house, now, rather than a home, to feel like four cold walls and a roof. The fridge doesn’t work. There’s no food in. The cats are not pattering about. My sister, deranged with the repetition of administration and grief, has gone back to London to work. It’s just me, alone here, padding around this place I own now, feeling as if I’m a ghost.

I got trapped in a wardrobe, here, once. This was when my parents were alive: I remember, actually, it was a rare moment of peace for them, a searingly white-hot day and I watched them, out of their bedroom window, my face and nose pressed tight against the net curtain, and they were chatting and repotting plants and seemingly both in a good mood, so I left them to it – I was, like, six at this point, maybe five – and so I turned around and went to play imagination games in the spare room at the back of the house, and ended up clambering into this old wardrobe – my mother, a sort of amateur seamstress, had stuffed it with old plastic bags of rags and fabric ends and half-done pieces of knitting, which were sort of slippery and fun to climb – and then the whole thing started to creak and tip and long story short it collapsed on me, vacuuming me entirely to the floor.

Now: a normal child, in this situation, I imagine, would scream. Yell or something. Thump on the wardrobe panels. Beg for a fraction of help. But I think I just accepted that hey, I guess this is how I die, swaddled in dozens of clothes bags, trapped in pitch blackness beneath a wardrobe. It was about 20 minutes before they came inside and found me, muffled steps up the stairs turning to quick sharp noises of alarm before my dad heaved the wardrobe off me, and I remember both their faces staring down at me, and the light pouring in, a combination of extreme did-my-child-die and just bafflement, and my mum just said: ‘Why didn’t you say anything?’ and I replied: ‘I just didn’t want to be any bother.’

I just remember that story a lot because whenever I try and recall my parents being together in the same room and not mad at each other that’s all I can ever think of. Me politely resigning myself to living the rest of my life out as a wardrobe boy, RIP, 1987–1992.

My parents are dead and I’m shopping at Tesco for vol-au-vents. Planning a wake is like planning the most vibeless party in actual existence: all the same motions as planning an actual party (invites, finger foods, the chilling of drinks) but none of the buzz or excitement, extremely low chance of anyone getting laid. In my trolley is: a tray cake, feeds 15; a number of 3 for 2 party foods, including cocktail sausages; a light and refreshing mix of own-brand lemonades and colas, as well as a respectful two (two.) boxes of beer. My sister is off in the far reaches of the shop buying lasagne supplies – my mother had this tradition where she would throw a party every Christmas and invite everyone round (and she was the exact type of woman to call such a party a soirée, to give you a bead on my mother), and for whatever reason her showstopper party food was ‘a lasagne’, she would make like four or five of these great, heaving lasagnes for people to eat great huge cubes off from slowly oily-going paper plates – and my sister intends to honour that tradition, God Bless Her Soul, by making her own lasagne, which everyone will tell her at the party in a quiet voice – it’s a very good lasagne, thank you – but with all the unsaid context being but it’s not Hazel’s lasagne, and I think my sister knows this, deep down. Anyway we are politicising the lasagne.

The point is that I am tired, so tired, it has been two weeks of admin and grief and sorting and nothingness and it’s still not over, yet, and I am taking a brief moment of respite while my sister weighs up beef vs lamb mince to lean on the trolley and stare at the freezer aisle and sigh, and someone says Joel, they say Hello, they say, How Are You.

It’s the mum of a girl I did not really know at school (she, the girl, was a good five or six rungs up the attractiveness ladder than me – I was an extremely obese smooth-faced 40-year-old mum-of-four looking kid for most of my adolescence, with a voice that seemingly took five years to break, and school hierarchy is defined by exactly two axes – who is hot, or at least if not hot then who get tits or a beard first; and who is hard, and the hard boys get with the tit girls and form these sort of royal allegiances, and kids like me get Really Into Videogames And Robot Wars And Metal Music – and so despite sharing a classroom with me for five consecutive school grades did not, in fact, know who I was) and also a former colleague of my mother’s, which is why she half recognises me more than I do her. ‘It’s Jackie,’ she says, ‘I used to work with your mum.’

And her face crumples and she goes: ‘I heard about the cancer.’ And I nod. And then she goes: ‘How is she doing?’ And I realise she does not know that my mother is dead.

And so now I am stranded here with a trolley full of wake food and a dilemma. Do I, really, want to do this in the middle of a supermarket freezer aisle section? Do I really want to have to explain what all the food is for, and how and why? We can pretend that I went through this – that I, like a lightning flash, rapidly weighed up the pros and the cons and decided logically on an outcome. We can pretend that happened when it did not. Instead, instinct kicked in and

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Not so great.’ Technically this was not a lie. And Jackie said: ‘Oh, well,’ and said, ‘give her my best.’ And I walked away thinking: that was a very strange thing that I just did. That was a very unusual thing to do.

My parents are dead and there is always cake at the funeral. It’s weird eating cake and being sad: at my dad’s, his ex-wife, Annie, had made one of the most astonishing cakes I’d ever eaten, a dense low chocolate cake with a mirror-finish ganache that shone like glass, and I was two slices, maybe three slices in – I was, as aforementioned, an especially large shapeless teenage boy with a sweat problem – when one of my mum’s cousins who I had never met ushered me over to his armchair. And he said, do you not think you need to lay off the cake? And I thought: today of all days, dickhead. Today of all days you come and tell me this.

Funeral guest lists are unusual affairs: you are as surprised by the attendees as the non-attendees. A throng of my sister’s closest uni mates – all in the first great flush of their early twenties and ostensibly with better shit to be doing than this – were at my dad’s; his lifelong best friend, Don, left the voicemail we left him telling him the news unanswered. At my mum’s funeral, none of her side of the family attended, including her closest cousin, Josie – but clearly she was popular at work because an entire office’s worth of people lined up to shake my hand and tell me what a good laugh she was. Only after death do you see facets of the living you once knew through the eyes of those who knew them away from you: you learn who thinks them kind, who considers them wise, who considers them a best friend. They, all of them, line up to tell you how they were capital-G Good: we are, all of us, washed of sin when we die. When we live we are jagged and complex and fucked up and we oscillate between joy and despair, and all of that is flattened out in death, all of those wrinkles uncrumpled. We go into the ground as saints.

My parents are dead and forms; forms, forms; forms, forms, forms. There is a form to declare death and you have to pay for each printout, which means you have to predict exactly how many corporations and banks and agencies are going to ask for certified proof of death and then pre-emptively pay £12 for them to have it, and we umm and ahh and ask for four (you need two, at most: if you take anything from this, just know that everywhere takes photocopies, and save yourself £24). Then you have to, as in our case where there is no will (while I am here handing out advice: if someone draws you up a will and you go through the hurdle jumping of defining exactly who gets what in a will and how the will should break up, and where everything goes after you die, and all you have to do to verify that will is sign it, exactly once, please sign it exactly once, and do not leave it, unsigned, for two years, on the table next to you among a big pile of post, Mum), jump through the various hoops to invoke probate, a sort of de facto all-of-this-dead-person’s-shit-now-belongs-by-blood-to-you ritual where I had to go to a local family court, get knife searched on the way in, then swear godlessly on a sign of the cross to say that I am the one true heir to a £90,000 terrace near Sheffield, nobody else may make claim on my land. The bank wants to know she’s dead, the electricity company. I stop chasing the £800 left in her building society account because the constant administration of it was too exhausting. The government sends me a letter to tell them they overpaid her pension, i.e. made payment into her account exactly once post-death, and now they would like that money back, now: I tear the paper up and scatter it into the bin. I am warned that people might wheedle out like cockroaches from beneath the family fridge: someone, somewhere, some distant cousin, might try to make a claim on what thin gruel there is left, and to be prepared for it. They mean legally, but I want it in blood: I am angry, so angry, I am ready to meet anyone head on, if anyone even steps to me and tells me they want a penny of what’s mine I will tear at them until they are just a mashed pile of red, I will punch and punch and punch, I need this, I need them to come out, I want so bad somebody to take this out on, I need it.

My parents are dead and one day, three years later, I go back there, to the house, after we’ve sold it. This is a mistake: I’m watching from sort of afar, in case an old neighbour sees and recognises me and we have to do a whole awkward thing, and everything feels juddery, at once familiar and not. The house looks more or less the same – steam rises from the exhaust vent on the boiler we had put in a few years ago; the smoke bush my dad planted 20 years ago still looks somehow both fragile and overgrown in the front garden – but it’s not. It’s late October, cold but not freezing, and, on the doorstep, there’s a pumpkin, carved for Hallowe’en. We never left a pumpkin out, even once. And then suddenly I am overcome with the realisation that this isn’t mine, now; that another family exists in this space, fills every corner of it with their own existence, their own sofa positioning, their laughs echoing on the walls they now own, their voices shouting upstairs for dinnertime, their crap filling the basement. I feel like a ship on the sea with endless deep blue beneath me and nothing holding me up. No anchor, no home. Someone else’s pumpkin makes me lose my entire mind.

My parents are dead and my friends are trying their best. My friend takes an afternoon off work and drives me out to the countryside, out far away from the grey jagged misery of the town, and I wind the windows down and let the warm June air rustle my hair, and I inhale bugs and lungfuls of green, wholesome air, and I put my hand out of the window and wave it through the wind, and then we stop at a pub overlooking green rolling hills, starched yellow almost in the sunlight, and we both sit down with amber ales and he tells me he thinks he has cancer.

‘What?’ I say. ‘What?’

And he sits stiff-backed in double denim and says: ‘In my bowels. They did a test. I’m waiting on the scans.’

And I say Jesus, I say Jesus Fucking Christ. What is with everyone getting cancer?

And he says I know.

And we drive in silence back to the town and we line up more beers in another pub and meet some friends and he tells them he thinks he has cancer (‘In my bowels,’ he says. ‘Blood. Bad blood, that black blood. They did a test. I’m waiting on the scans.’) and he starts crying so much the landlord very quietly asks us to leave the pub, because quote, unquote we are really bringing the vibe down, and then the next pub we go into we are also asked to leave because of the crying thing, too. And at the funeral a week later I ask him if he’s coping okay and he says a cheerful ‘Yep!’ and then proceeds to not ever mention cancer or die over cancer at any point over the next three years, and I figure there is something, about death, there is something that brings out the weird little crevices in all of us.

My parents are dead and it’s a year or so later and everyone thinks that I’m fine including me. I’m cat-sitting for my sister, my boys, my big beautiful boys, but there’s something wrong with Boz: he’s thin when he used to be plush, he’s quiet when he used to be loud, he keeps coming up to me, shaking and feeble, just leaning on me with all the little weight that he has. One morning, before I leave for work, I find him after calling him for breakfast, and there he is, shaking under a shelf: I coax him half out, bring him a small plate of biscuits, swaddle him with a towel. Boz has been my best little mate since I was eleven and he was six months old, and now I look into his huge orange eyes and I know that he is dying. Moww, he says, and I say moww back, and I cry, and cry and cry and cry, and kiss his little head, and cry and cry and cry, and I’m crying now, and I cry and cry and cry and cry, and I suppose that’s when it all hits me – me, on the floor, cat biscuits on my fingers – that’s when it hits me most of all.

* * *

My parents are dead and I’m starting to get to the age where my friends’ parents are dying, too, and I feel I should know what to say to them. And I never really do: instances of grief, I have found, are unique, two never coming in the same shape, and they can be piercing and hard-edged and they can be like passing through deep dark treacle or they can be like a long, slow-passing cloud, it can make everything grey or everything sharp, it can hit you like a truck or it can hit you like cholesterol. There is no one single catch-all solution to dealing with the worst life has to throw at you because life has such a habit of swinging you curveballs.

But what I do always say is: oh man, this is going to suck.

And I always say: you need two fewer death certificates than you think you need.

And I say: snakes will come up from the grass and you will want to hurt them.

And: at one point you are going to become keenly aware that everyone is judging you for the exact way you outwardly behave when someone close to you dies, and I need to tell you that that is a nonsense. You are going to feel a dirty little feeling of guilt. If there’s a long illness involved, there might be this horrible, metallic-tasting feeling of relief, one too hard and real for you to admit to yourself is there. You will do weird things and behave weirdly and not even know it is happening. You will offer up a portion of your psyche to the grief gods and say to them in the rain: take this and do what you want with it. Suddenly your body is not your own, your mind, your home. There’s no right way of dealing with it but there are a thousand differently angled wrong ways. You’ll cycle through all of them.

I’m on my fourth Christmas without parental guidance now, and I suppose I am okay. There are still times when I feel unutterably alone – times when all I need is my mum’s roast, or a voice that knows me on the other end of a phone to tell me things will be alright again, or what I need to do to make things alright; times when I’d give anything to go for one pint with my dad, or drive around in his smoky old Volvo listening to Fleetwood Mac. It’s weird what you miss: every holiday we had, when I was a kid, was foreshadowed on the morning of travel by my dad getting the shits – every single time, without fail – and our journey to Cleethorpes or Scarborough or Whitby or Filey would be delayed by Dad, in the bathroom, making the air sharp and sour, groaning through the door, and Mum, on her tenth or eleventh furious cigarette, hissing, ‘Every. Bloody. Time. Tony! Every. Fucking. Time.’ through her teeth, and I don’t know. Holidays don’t seem the same without this consistent element of intestinal chaos beforehand.

I picked up his camera, recently. I think a lot of people my age and of my generation get this delayed obsession with film – that gauzy, blurry, physical quality of it, haunted eyes reflected back from a flash bang, a fraction of a second of light that could have exploded – just for a moment – a day ago, or a week, a year, one hundred, more a frozen moment in time, somehow, than anything digital – and I asked my sister to dig out his old Nikon. I turn 30 this year, a moment that will be marked with me living more of my life without him than I ever did with, and it was curious, looking into that bag, reminding myself of a time left behind me: an old emergency pack of Rizlas, the gnarled old piece of tights material he used as a lens cleaner; the ephemera of a life left behind. The bag smelled of him. I held the camera up to my face, put the eye where his eye had been, nestled my nose where, years before, he would have squashed his. Click. You wonder what they would make of you, now. Click. How they might be proud of what you’ve become. Click.

(#ulink_5c5e6a60-f8b2-52e1-95d6-c931683b299a)

Dad taught me how to make a prison bomb once. I do not think my mum ever knew about this. This was not on the family curriculum. But we were playing cards one day when I was ten, and, ‘Oh,’ Dad said, as if recalling some vital lesson all fathers teach to their children that he had somehow neglected, ‘right: you know you can make a bomb out of this?’ And I said: I’m listening.

You can make a prison bomb out of a pack of cards, Dad explained, if you cut all the little red pieces out – the hearts and the diamonds, and any red ink-like paste that might be smeared on the back – and mush them into a wet paste, which you cram down a radiator pipe or some such. When the pipe heats up – it’s an inelegant art, and results vary, so don’t, like, sleep close to it, especially not head-first – some chemical reaction will happen, which causes it to explode, dismantling the wall behind it and through which you – he motioned me in a very confident way, as if to say, ‘You, my sweet large son, are destined for prison’ – through which you escape. And that’s a prison bomb. And that’s rummy.

I didn’t really question this at the time because dad was always talking about war stuff and cannons and stuff, and also because he went to prison once. This, again, was one of those strange things that was never explained to me as being abnormal – Dad got stopped for drink-driving once and given a warning, and then he was stopped again and given a fine, and seeing as we were poor and couldn’t pay the fine he did three weeks in prison, one week maximum security and then another fortnight – after they realised how truly meek and unthreatening he was – in an open prison somewhere near Leicester. ‘How was prison, Dad?’ I asked, when he came back again. He said: ‘Not bad.’ He genuinely looked quite healthy. Prison wore well on my father.

We didn’t talk about prison much after that, mainly because it was such a pathetic stretch he did – I mean I never even had to draw a heartbreaking crayon-coloured picture of our family, labelled ‘MUMMY’, ‘DADDY?’, ‘ME’ about it – and also because Mum very strictly forbid us talking about it (she was really mad about that time he had to go to prison). But one day I answered the phone – one of my pathological childhood obsessions, for a while, was snatching the phone up and answering it in my politest sing-song – and a strange voice on the other end growled: ‘Is that Joel?’

Yes, I said.

‘Hello Joel,’ he said (imagine the voice is more prison-y than that. You are not reading it prison-y enough, and I can tell). ‘Hello, Joel,’ the prison voice said. ‘I’ve heard a lot about you. Is your dad there?’

And I said sure, who is it.

And he said, John.

And so I yelled up the stairs, D–AAAA–D, JOHN’S ON THE PHONE.

And my dad appeared before me like death had learned to shit his pants in fear.

‘Yeah,’ my Dad said, shakingly, as I watched. ‘Yeah. Yeah. Yep. No I’ll— yeah. No I’ll come to you. Yeah. Yep. See you there.’ And then he hung up and turned and swivelled into a crouch down next to me and said, Don’t Tell Your Mother.

I’m not saying who told her but she found out.

It turns out Dad had made friends, in prison, as he was wont to do as he was a very mellow and agreeable man, especially friends with his bunkmate, John, who murdered someone. ‘Yeah come over,’ Dad said into the bunk above him, confident this man would never be released from prison ever in his life. ‘We’ll get a drink. Kip on the sofa until you sort yourself out.’ And then John fucking got parole, and instantly called the only phone number he had on his person, which was my Dad’s, and asked if he could stay with us, promising not to do a murder again. The row between my parents that night – the Red Corner fighting ‘can a murderer stay on our sofa’ and the Blue Corner fighting out of ‘absolutely fucking not’ – went on so long our neighbours kept flicking their bedroom lights on and off in a really passive–aggressive way, slamming their flat fists against the shared wall that ran over our alleyway.

John never stayed, in the end – ‘Because of the murder,’ I imagine my dad saying, over the pint they eventually shared, at a pub far, far away from our house, and I like to think John was a gentlemanly murderer who waved his hand and said ‘I understand’ – but I always like that my dad even tried it: that he thought a murderer could stay with us, for anywhere between one day and six months, really says a lot about him, his gentle trusting nature and his inability to operate anywhere within the sensible laws of society.

I often imagine how I would do, in prison. Quietly, I think I’d thrive. The Boys there would at first be suspicious of my smart mouth and bookish ways, and look to teach me a violent lesson, but I think after the first two or three beatings they would take a begrudging shine to me – ‘He does reading,’ they will say, proudly, to their bunkmates, ‘He’s helping me write a letter to my lawyer’ – and that, over time, would evolve into a quiet sort of respect. One day a young upstart would try and beat me with a metal pipe on his first day to prove some sort of point, and the more seasoned inmates would jump to my defence – ‘Leave him alone!’ they’d say, ‘He’s just a harmless little soft cunt!’ – and I would say Thank You, Lads, dusting my prison uniform off, going back to my eccentric little hobby of cutting all the red bits out of cards. And then one day, just like Daddy taught me, I’d blow every one of those fuckers up to kingdom come, and sprint off into the night, hooting and hollering with delirium, until the police shot me to death with Tasers. But I still wouldn’t fucking invite a murderer to dinner, would I? Because I’m not mad.

(#ulink_e88cf4e8-edb9-51b7-9ea5-86caf4188204)

#.

I got to tell you that there is something singularly amusing about watching a Dutch teenager swear in a flurry of American slang. Fucking shit bro, fuck man. Jord is swearing. Fucking shit man, my mom. Jord just got down to the last five of the game – 100 players whittled down to a handful over a grinding 35 minutes – and the circle draws ever tighter, pushing those last few remaining players in, and they are all concentrated on this one small patch of bushgrass, and Jord is just lining up his shot, he’ll go through the back of the head of this guy then hop over and loot his ammo then use it to take out the final two players a little over the ridge, this is a very high tension thing – and then his mum stumbles in and the mic is abruptly muted and we watch, thousands of us, in silent horror, as Jord’s entire head is shot to pieces while he pliantly talks to his mum. He turns back to the screen and sees himself as a mess of blood and ammo. Fuck man, my mom, he explains. Fuck. He rubs his eyes and regains composure. No man, she— I don’t mean that. She means well. Exit to Lobby, new game, the tide washes in with the moon.

OR: JASONR needs to piss. It is midgame – that gauzy time when the initial flurry of desperate gun-hunting and easy-pickings inner-city kills have quietened down, and so now it is a case of picking your way through the expanse, picking up improved helmets and gun sights and vehicles, taking tactical positions up on hills and the roofs of houses – and he is swimming across a small river to get to the other side of the island. But he isn’t: Jason has left his character automatically swimming – ‘I gotta pee, man’ – and everyone in the chat is deliriously tense in his absence. I seen Jason die like this, one chatter says. Another: it’s a long shot but he can take him out. Jason’s teammate, some guy a thousand miles across the country, pings to no one on the audio chat. Jason? Jase. Jase. He’s gone a really, really long time. He bobs in the water. When he returns from his piss I am once again allowed to breathe.

OR: Shroud is falling apart. ‘My eye is twitching guys, I don’t know why.’ The chat moves so fast you can hardly see it: it’s caffeine, the chat says, or you need special blue-lens glasses to play in. Shroud is hardly watching because he is focussing on just ruining the brains of the schoolyard of players who have landed around him, so his fans take it into their own hands: donations of $10 or more get read out over the screen by a robotic voice, and they use it to communicate with their god. ‘I’m not buying those blue glasses,’ he tells one donor. Another message flashes up on screen: you have a magnesium deficiency, it says. You need to buy supplements. Shroud mulls this over while he kills two guys, perfect headshots, boom. ‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘Maybe you’re right.’ He stares at the screen without blinking for five more hours. What sustains him also kills him.

OR: Shroud, again, mid-game, again, and he’s talking about his living arrangement. How he couldn’t rent this place – he gestures around him, the immaculate unfurnished flat wall behind him – because he had no credit history. But it turns out the landlord’s daughter knew who he was, how he made money, how much of it he banked, so they agreed to let the apartment to him, figuring he wouldn’t make much noise anyway. Boom, pshht, headshot out of nowhere. ‘Well, didn’t see that,’ he says, reloading the game all over again. Piss, eyes, moms, rent. Heads exploding without warning. Periodic reminders that our gods are still mortal.

#1.

I have to tell you that I am really into watching people play videogames now. I want to be clear about this: I own the means with which to play videogames myself. I have a console and a controller and a TV and games. I can, if I want to, play the videogames. But that is like saying I have a football in my garden, so why do I have to bother watching Messi. Yes, I can play videogames. I can take back the means of control. But also I am very bad at them, in a way I cannot communicate to you. I can play videogames, but it is actually far better to watch people who are good.

Twitch is a website where you watch other people play games, and I did not understand it until I got Really Into Watching Other People Play Games. The game I am obsessed with watching is Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds, which Jord and Shroud and JASONR are fantastic at, and I am appallingly bad. Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds, in short: a 100-man battle royale set across a digital island, where you parachute in and loot empty buildings until you find enough guns and lickspittle armour to mount an attack on your fellow players. The game’s active area slowly shrinks – this adds a vital layer of urgency to proceedings, to stop people camping out and games lasting eight to nine hours each – until, after about 35 minutes, the once island-sized game map is crushed into the size of a single field, and it becomes a kill-or-be-killed hellscape. The first time I played it I died within one minute and proclaimed the game to be ‘bad’ or ‘shit’ (I forget which). Second time I made it until about three minutes in, before I was cleanly dispatched by an uzi for an overall ranking of around #89. My friend Max then took over, and came #2 overall, after a 40-minute stand-off, a Jeep chase, an exquisite sniper takeout and this one time where he threw a grenade into a room. The final battle saw him and one other fight for supremacy around the edge of a hill, and he was taken out by a single bullet to the side of the head. Here is an impression of me, sat on a computer chair at Max’s shoulder, trying not to breathe too loudly and so put him off his aim: ‘[Hands held over mouth, breath held, voice coming out strangled and high pitched] Fuck! Shit shit shit! Fuck!’ It was the most exhilarating gaming moment I had ever seen. I mean, Christ man. I live a relatively empty life. It was possibly the most exhilarating anything moment I had ever seen. So you see now how instantly I was hooked.

But as we have discussed I am terrible at the game (my simple mind cannot, however way I try, get my head around the W–A–S–D keyboard movement system, and for now PUBG is PC-only), so instead I watch Jord play it on Twitch. Or: I watch Shroud on Twitch, because his American time zone means it’s easier to watch in the evenings (at weekends, when I want to wake up and watch someone playing videogames who isn’t me, I watch American streamers who stay up deliberately late in their time zone to catch the European early morning audience, and they all wear caps and have obnoxious catchphrases, and I universally hate all of them). I watch some guy called JASONR sometimes, and though I don’t like him as a human, I respect him as a player: all three of them have this preternatural reaction time, a kind of hardwired cold-bloodedness and resistance to panic, unerring accuracy with digital rifles even over long distances, and also this relentlessness: they wear their rare losses lightly, so when their heads explode in the middle of a grey-brown field they, instead of wail and gnash with the sting of loss, boot up the game and go again. Essentially: the mindset of highly tuned professional athletes, but in the bodies of slightly awkward nerd teens. Twitch is a curious beast: a YouTube-shaped streaming platform that technically can be used to broadcast anything but is almost exclusively used for showing people playing games, Twitch was bought for $970 million by Amazon in August 2014 and is now worth an estimated $20 billion, with its own sub-currency tipping system – the ‘Cheer’ – slushing around its network. Fans of streamers can pay $1.40 to buy 100 ‘Cheers’ which they then donate to their favourite gamers through various in-chat messages (the gamer themselves will get around $1 for every 100 cheers – Twitch needs to take its vig) and emoticons: for a sneak peek at the future of capitalism, there is a single emoji that costs $140 to enact. Alternatively, fans can donate directly to streamers – tipping the odd $5, $10 here and there, or subscribing for a fee every month, thank you bro, thanks for the sub, thank you guys for the donnoe – with more money going directly to the gamer’s coffers. So to reiterate: Twitch is a website where you can watch someone else play a game and, if you really want to, you can pay the person you are watching to let them let you watch them play a game. At no point in this interaction do you, personally, get to purchase and play the game. You only watch. Some Twitch streamers are multi-millionaires. It has previously been impossible to tap into why.

#2.

I know why, and I and I alone have figured out why. In the adolescence years 13 thru 17 – a four-year long feeling of emptiness and antsiness and crushing, overpowering horniness I am going to nominally refer to as Wanke’s Inferno – I would go to my friend Matt’s house and watch him play videogames. It wouldn’t matter what time I would go over there – 2 p.m., 10 p.m., 2 a.m. – Matt would be awake, and playing videogames. This is because Matt was a goth, and goths are always up playing videogames. Also his mum was a nurse who worked nightshifts so his house was always best to scratch at the window if an existential crisis hit at 1 a.m. and you just needed to be out of your house and in the vague presence of some company, which very often happens when your body is pulsating with the dual needs to i. grow, constantly, in every direction and ii. be so horny your head might explode. Everything seems happy and sad at the same time when you are a teen. Psychically it’s like putting your head in a washing machine, for eight years.

Here’s what the back of Matt’s head looks like: an at-home dye job is growing out, so at the crown of his head is a digestive biscuit-sized circle of his natural hair colour, somewhere between blond and brown, while the rest of his hair was dyed black (see: goth) with a stripe at the front that was electric blue (also see: goth). The stripe didn’t last long, actually – it is hard to maintain an electric blue stripe of hair at the best of times because it requires bleaching the hair and then dyeing over the top of that bleached hair in the colour of your choice, and bright colours wash out quickly, and being a goth on pocket money is the exact polar opposite of the best of times, so after a while the blue fell out and there was just a sort of pale blonde streak remaining. I remember all of this vividly because for an entire summer of my teens I looked fixatedly at the back of Matt’s big goth head while he played Quake 4, Unreal Tournament, and, for some reason, this extended six-week period where we linked a SNES up to an old CRT TV and compulsively played Dr. Mario until the sun came up through the trees.

I mention all this because going to a friend’s house and watching them play videogames is exceptionally nourishing to teen boys. I mention all this because all those half-conversations I would have with the back of Matt’s head while he coldly racked up headshots were some of the best and also least consequential of my life. I would lay on his black bedsheets (goth), play with a skull candle of his (goth), flap at the blackout curtains (goth goth goth), occasionally disassemble an old Warhammer model of his (nerd) or read a comic (nerd) by Jhonen Vasquez (goth), and Matt would still be that, spine curled, hand on the mouse, headshot after headshot, while I unloaded. It was as close to therapy as two teen boys can get: chatting, and chatting, and chatting, every worry and every gripe, every girl we liked and every hope for the future, who we wanted to be, what we feared, how scared we were to grow up: all without a scrap of eye contact, conversation occasionally just falling into a lull, of grunts and occasional laughs, as heads exploded and arms came off in geysers of blood. Occasionally I would fall asleep on a Sonic beanbag on his floor, and have to be wearily stirred awake again at 4, 5 a.m., when I would wander home in my shirtsleeves through the chill. As I grow older, I am more deeply aware than ever that, essentially, a very large part of me has always wanted to retreat back into the nerve-jangling terror womb of adolescence, whether in search of a hard reset, or a time when life was consequence free, or just to be 17 again and actually learn to drive this time. I feel most men, given the option to go back and revisit their teen years with an adult mind, would for some reason jump at the chance. It was a time when your body is lithe and willowy and full of potential, and way less hairy. The most exciting thing that can happen to you is you can distantly see a girl you are in love with – and who is unaware you are alive – at the mall. It is a horrible, terrifying, high adrenaline time to be alive and I miss it with every atom of my body. Watching my friends play videogames emulates that feeling of distorted comfort all over again. Doing so with some Dutch guy called Jord over Twitch allows me to wallow in a black bedsheeted pit of nostalgia from the comfort of my desk at work.

#3.

Twitch taps into a new media landscape that makes absolutely no sense to fucking anyone, but that seems to be the way things are going, and Twitch is only one strange facet of that. Example: I recently had lunch with a friend and he told me about his obsession with Dr. Sandra Lee, or ‘Dr. Pimple Popper’, a woman with an immaculate bedside manner and a preternatural gift for lancing cysts, who lives both in her doctor’s office and also on YouTube. Every video she has ever done goes like this: a floating, eerie mid-zoom of the boil or zit or massive tumour-esque mass she is about to explode, which she prods at with rubber-coated fingers, purring and describing it in a cheerfully clinical tone. Then: then a jump-cut to the boil or whatever swabbed in surgical cloth. And then, using either her fingers or precise metal tools, she slices it open and squeezes out all the yellow gunk inside. It is horrible and fascinating: watching poison ooze out of humans, thick custardy torrents of it, then stitched neatly up and dabbed over with surgical spirit. My friend, a neat freak with OCD, says it taps into his compulsive need for things to be clean, tidied, free of chaos. ‘I watch them while I’m eating my breakfast,’ he says, the maniac. ‘Muesli, yoghurt, zits.’

OR: I found myself in a cab recently having one of those conversations you only seem to have when you’re shouting from one end of the car to another, and in it I was explaining the concept of ASMR. ASMR, or ‘autonomous sensory meridian response’, is this tingling effect some people get in their ears when they hear certain sounds – paper crinkling, soft finger clicking, whispering – something close to synaesthesia. YouTube has thousands of hours of videos dedicated to ASMR triggers, and a small-but-dedicated audience hungry for more, but obviously it’s very hard to just whisper for 30 minutes straight, so you find these performances quickly veer into something very weird – they are all recorded at 4am, when outside static noise is at its lowest, and the performers all do these weird drama class ad-libs, talking to themselves through various whispered scenarios. So like: one guy does this bit where he is an extremely rude waiter, talking down to you about a reservation you didn’t make uninterrupted for 40 fucking minutes. Or: there is this one guy, Toni Bomboni, who looks sort of like a LazyTown villain come to life, and I once watched a video of him in the scenario of ‘a gum store’, where he would chew and taste various bubblegums on your behalf to help advise a very serious gum purchase you (the viewer) were going to make, again something that went on, whispered, for like three-quarters of an hour. So I mean go to TV and say, ‘Hey: I’ve got a half-hour video of a lad chewing gum to himself and urgently whispering. You uh … you want that?’ and TV will say: no thank you. But the Internet has carved out its own weird niche of anti-media. Some people just like watching people do mad and boring shit. Some people like to watch skin erupt, or maniacs whispering. I, for example, I can only relax to headshots.

#4.

As best I can tell there are four or five species of Twitchers (I do not know if ‘Twitchers’ is a word or the accepted term: we are just going to have to assume that it is), which can be categorised as thus:

— Extremely Hyperactive Kid Who You Just Know Got Put Bodily Into Some Lockers At School: these are of course my least favourite Twitchers, because they are boys who fundamentally did not fit in to the intended hierarchy of the world of school or work – they were down at the bottom, punching fodder for jocks and so on, not smart enough to be genuine nerds, not physically dextrous enough to fight anyone off, doomed forever to be henpecked and unhappy – but then who found their niche (streaming videogames to an audience of millions) and so jumped up through their expected social stratas and became as obnoxious as possible in as short a period of time, so they have adopted the sort of bro-y discourse of actual bros, and say things like ‘fam’ and ‘you guys’ and ‘wuh–POW!’ and ‘[every single irritating sound effect a human being can make with their mouth]’, and gurn to the camera, and develop their own little catchphrases and routines, and behind them is a plethora of sort of wide-tyre nerd culture ephemera – anime posters, figurines from popular adult cartoons, Monster-branded green neon-lit mini-fridges, extremely complicated gaming chair/gaming headset set-up – and then they act in front of it, and they are extremely annoying, these people, on the surface, but also very much you can see not even very deep within them to see the vulnerabilities and frailties within, and I just know that every single one of them I could make cry with an accurately timed ‘your momma’ joke, and that’s no way to respect another adult, is it—

— Quiet PhD Student Type Who Just Loves Exploding Digital Heads: these ones are my favourite, because they transcend the idea of performative streaming – i.e. the idea that streaming videogames is about anything other than the videogame and the skill they possess at the videogame – that being a personality is secondary, tertiary, to having quick mouse response times and unerring accuracy with a sniper rifle, and these are the guys who take it closest to a sport. There is a narrative, in sport, of showboaters and not: the lads who have hot new hairstyles, and tattoos, and take selfies on Instagram, and still ascend to the very top of the game (in football: Neymar, Beckham, C. Ronaldo), and they infuriate your dad because of it, and then you have those who don’t, head-down-and-score-a-lot-of-goals lads (again football: Messi, Shearer, Xavi), who your dad adores. That’s the split in sports: that being good at sport – at being one of the five very best people on the planet at kicking a football – but also having ego around that, at being happy to be nearly supernaturally good at something, is somehow profane. In sports, I love these showboaters: when it comes to watching them play shoot-em-ups, they tire me out. Give me a quiet Dutch lad who is killing 40 minutes before he does his homework any day of the week.

— ‘The Character’. Some streamers dress in wigs and wraparound shades and eighties-style leather jackets and the like and maintain all these catchphrases and go-to sayings and stuff like that and in one way I very much admire them for developing a character and sticking to it, unbreakably, like a mid-eighties American shock jock, and in another far deeper way I cannot watch even one minute of them playing videogames, holy jesus, I am never in a thousand timelines going to be wired-out on Red Bull enough to find that funny—

— Girl Streamers, who unfortunately have this horribly uphill battle to Prove Themselves To Be Sincere, the gamer boys who are so primed to watch girls in like calf-high socks and pigtails and full-face anime-inspired make-up kill dudes in battle royale settings and do kawaii peace signs to the camera being sort of bait as well as red rags to these dudes, dudes both wanting very much to sexually conquer them – the chat that runs alongside Girl Gamers being, essentially, pornographically explicit – as well as mad at them for liking their safe little male thing, intruding into their world, so Girl Gamers are seen as a sort of strange curiosity in a male-dominated sport (even for male-dominated sports e-sports is a male-dominated sports), but also I find the associated energy that goes after them fundamentally fatiguing, so I cannot watch them for very long, and that is my cross to bear, sorry ladies—

#5, OR: THE AUDIENCE WILL EAT ITSELF EVENTUALLY