Collins Chillers

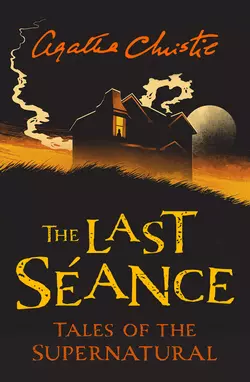

Agatha Christie

From the Queen of Crime, the first time all of her spookiest and most macabre stories have been collected in one volume.“Reading a perfectly plotted Agatha Christie is like crunching into a perfect apple: that pure, crisp, absolute satisfaction.”—Tana FrenchFor lovers of the supernatural and the macabre comes this collection of ghostly and chilling tales from legendary mystery writer Agatha Christie. Fantastic psychic visions, spectres looming in the shadows, encounters with deities, a man who switches bodies with a cat—be sure to keep the light on whilst reading these stories.The Last Séance gathers twenty tales, some featuring Christie’s beloved detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, in one haunting compendium that explores all things occult and paranormal, and is an essential omnibus for Christie fans.

THE LAST SÉANCE

TALES OF THE SUPERNATURAL BY

Agatha Christie

Copyright (#u72d0c14f-6048-54d2-bc79-9d8c3b113e8a)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Collins Chillers edition published 2019

The AC Monogram Logo is a trade mark and AGATHA CHRISTIE, POIROT, MARPLE and the Agatha Christie Signature are registered trademarks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere.

Copyright © Agatha Christie Limited 2019. All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com (http://www.agathachristie.com)

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover illustration © Matt Griffin

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008336738

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008336745

Version: 2019-08-20

CONTENTS

Cover (#u18aa3b0e-5ab0-59de-8014-992f342ea719)

Title Page (#u0da778f8-7137-55d8-bc98-99695d07147f)

Copyright

The Last Séance

In a Glass Darkly

S.O.S.

The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb

The Fourth Man

The Idol House of Astarte

The Gipsy

Philomel Cottage

The Lamp

The Dream

Wireless

The Wife of the Kenite

The Mystery of the Blue Jar

The Strange Case of Sir Arthur Carmichael

The Blue Geranium

The Call of Wings

The Flock of Geryon

The Red Signal

The Dressmaker’s Doll

The Hound of Death

Bibliography

Also in this series

About the Publisher

THE LAST SÉANCE (#u72d0c14f-6048-54d2-bc79-9d8c3b113e8a)

Raoul Daubreuil crossed the Seine humming a little tune to himself. He was a good-looking young Frenchman of about thirty-two, with a fresh-coloured face and a little black moustache. By profession he was an engineer. In due course he reached the Cardonet and turned in at the door of No. 17. The concierge looked out from her lair and gave him a grudging ‘Good morning,’ to which he replied cheerfully. Then he mounted the stairs to the apartment on the third floor. As he stood there waiting for his ring at the bell to be answered he hummed once more his little tune. Raoul Daubreuil was feeling particularly cheerful this morning. The door was opened by an elderly Frenchwoman whose wrinkled face broke into smiles when she saw who the visitor was.

‘Good morning, Monsieur.’

‘Good morning, Elise,’ said Raoul.

He passed into the vestibule, pulling off his gloves as he did so.

‘Madame expects me, does she not?’ he asked over his shoulder.

‘Ah, yes, indeed, Monsieur.’

Elise shut the front door and turned towards him.

‘If Monsieur will pass into the little salon Madame will be with him in a few minutes. At the moment she reposes herself.’

Raoul looked up sharply.

‘Is she not well?’

‘Well!’

Elise gave a snort. She passed in front of Raoul and opened the door of the little salon for him. He went in and she followed him.

‘Well!’ she continued. ‘How could she be well, poor lamb? Séances, séances, and always séances! It is not right—not natural, not what the good God intended for us. For me, I say straight out, it is trafficking with the devil.’

Raoul patted her on the shoulder reassuringly.

‘There, there, Elise,’ he said soothingly, ‘do not excite yourself, and do not be too ready to see the devil in everything you do not understand.’

Elise shook her head doubtingly.

‘Ah, well,’ she grumbled under her breath, ‘Monsieur may say what he pleases, I don’t like it. Look at Madame, every day she gets whiter and thinner, and the headaches!’

She held up her hands.

‘Ah, no, it is not good, all this spirit business. Spirits indeed! All the good spirits are in Paradise, and the others are in Purgatory.’

‘Your view of the life after death is refreshingly simple, Elise,’ said Raoul as he dropped into the chair.

The old woman drew herself up.

‘I am a good Catholic, Monsieur.’

She crossed herself, went towards the door, then paused, her hand on the handle.

‘Afterwards when you are married, Monsieur,’ she said pleadingly, ‘it will not continue—all this?’

Raoul smiled at her affectionately.

‘You are a good faithful creature, Elise,’ he said, ‘and devoted to your mistress. Have no fear, once she is my wife, all this “spirit business” as you call it, will cease. For Madame Daubreuil there will be no more séances.’

Elise’s face broke into smiles.

‘Is it true what you say?’ she asked eagerly.

The other nodded gravely.

‘Yes,’ he said, speaking almost more to himself than to her. ‘Yes, all this must end. Simone has a wonderful gift and she has used it freely, but now she has done her part. As you have justly observed, Elise, day by day she gets whiter and thinner. The life of a medium is a particularly trying and arduous one, involving a terrible nervous strain. All the same, Elise, your mistress is the most wonderful medium in Paris—more, in France. People from all over the world come to her because they know that with her there is no trickery, no deceit.’

Elise gave a snort of contempt.

‘Deceit! Ah, no, indeed. Madame could not deceive a new-born babe if she tried.’

‘She is an angel,’ said the young Frenchman with fervour. ‘And I—I shall do everything a man can to make her happy. You believe that?’

Elise drew herself up, and spoke with a certain simple dignity.

‘I have served Madame for many years, Monsieur. With all respect I may say that I love her. If I did not believe that you adored her as she deserves to be adored—eh bien, Monsieur! I should be willing to tear you limb from limb.’

Raoul laughed.

‘Bravo, Elise! you are a faithful friend, and you must approve of me now that I have told you Madame is going to give up the spirits.’

He expected the old woman to receive this pleasantry with a laugh, but somewhat to his surprise she remained grave.

‘Supposing, Monsieur,’ she said hesitatingly, ‘the spirits will not give her up?’

Raoul stared at her.

‘Eh! What do you mean?’

‘I said,’ repeated Elise, ‘supposing the spirits will not give her up?’

‘I thought you didn’t believe in the spirits, Elise?’

‘No more I do,’ said Elise stubbornly. ‘It is foolish to believe in them. All the same—’

‘Well?’

‘It is difficult for me to explain, Monsieur. You see, me, I always thought that these mediums, as they call themselves, were just clever cheats who imposed on the poor souls who had lost their dear ones. But Madame is not like that. Madame is good. Madame is honest and—’

She lowered her voice and spoke in a tone of awe.

‘Things happen. It is not trickery, things happen, and that is why I am afraid. For I am sure of this, Monsieur, it is not right. It is against nature and le bon Dieu, and somebody will have to pay.’

Raoul got up from his chair and came and patted her on the shoulder.

‘Calm yourself, my good Elise,’ he said, smiling. ‘See, I will give you some good news. Today is the last of these séances; after today there will be no more.’

‘There is one today then?’ asked the old woman suspiciously.

‘The last, Elise, the last.’

Elise shook her head disconsolately.

‘Madame is not fit—’ she began.

But her words were interrupted, the door opened and a tall, fair woman came in. She was slender and graceful, with the face of a Botticelli Madonna. Raoul’s face lighted up, and Elise withdrew quickly and discreetly.

‘Simone!’

He took both her long, white hands in his and kissed each in turn. She murmured his name very softly.

‘Raoul, my dear one.’

Again he kissed her hands and then looked intently into her face.

‘Simone, how pale you are! Elise told me you were resting; you are not ill, my well-beloved?’

‘No, not ill—’ she hesitated.

He led her over to the sofa and sat down on it beside her.

‘But tell me then.’

The medium smiled faintly.

‘You will think me foolish,’ she murmured.

‘I? Think you foolish? Never.’

Simone withdrew her hand from his grasp. She sat perfectly still for a moment or two gazing down at the carpet. Then she spoke in a low, hurried voice.

‘I am afraid, Raoul.’

He waited for a minute or two expecting her to go on, but as she did not he said encouragingly:

‘Yes, afraid of what?’

‘Just afraid—that is all.’

‘But—’

He looked at her in perplexity, and she answered the look quickly.

‘Yes, it is absurd, isn’t it, and yet I feel just that. Afraid, nothing more. I don’t know what of, or why, but all the time I am possessed with the idea that something terrible—terrible, is going to happen to me …’

She stared out in front of her. Raoul put an arm gently round her.

‘My dearest,’ he said, ‘come, you must not give way. I know what it is, the strain, Simone, the strain of a medium’s life. All you need is rest—rest and quiet.’

She looked at him gratefully.

‘Yes, Raoul, you are right. That is what I need, rest and quiet.’

She closed her eyes and leant back a little against his arm.

‘And happiness,’ murmured Raoul in her ear.

His arm drew her closer. Simone, her eyes still closed, drew a deep breath.

‘Yes,’ she murmured, ‘yes. When your arms are round me I feel safe. I forget my life—the terrible life—of a medium. You know much, Raoul, but even you do not know all it means.’

He felt her body grow rigid in his embrace. Her eyes opened again, staring in front of her.

‘One sits in the cabinet in the darkness, waiting, and the darkness is terrible, Raoul, for it is the darkness of emptiness, of nothingness. Deliberately one gives oneself up to be lost in it. After that one knows nothing, one feels nothing, but at last there comes the slow, painful return, the awakening out of sleep, but so tired—so terribly tired.’

‘I know,’ murmured Raoul, ‘I know.’

‘So tired,’ murmured Simone again.

Her whole body seemed to droop as she repeated the words.

‘But you are wonderful, Simone.’

He took her hands in his, trying to rouse her to share his enthusiasm.

‘You are unique—the greatest medium the world has ever known.’

She shook her head, smiling a little at that.

‘Yes, yes,’ Raoul insisted.

He drew two letters from his pocket.

‘See here, from Professor Roche of the Salpêtrière, and this one from Dr Genir at Nancy, both imploring that you will continue to sit for them occasionally.’

‘Ah, no!’

Simone sprang suddenly to her feet.

‘I will not, I will not. It is to be all finished—all done with. You promised me, Raoul.’

Raoul stared at her in astonishment as she stood wavering, facing him almost like a creature at bay. He got up and took her hand.

‘Yes, yes,’ he said. ‘Certainly it is finished, that is understood. But I am so proud of you, Simone, that is why I mentioned those letters.’

She threw him a swift sideways glance of suspicion.

‘It is not that you will ever want me to sit again?’

‘No, no,’ said Raoul, ‘unless perhaps you yourself would care to, just occasionally for these old friends—’

But she interrupted him, speaking excitedly.

‘No, no, never again. There is danger. I tell you. I can feel it, great danger.’

She clasped her hands on her forehead a minute, then walked across to the window.

‘Promise me never again,’ she said in a quieter voice over her shoulder.

Raoul followed her and put his arms round her shoulders.

‘My dear one,’ he said tenderly, ‘I promise you after today you shall never sit again.’

He felt the sudden start she gave.

‘Today,’ she murmured. ‘Ah, yes—I had forgotten Madame Exe.’

Raoul looked at his watch.

‘She is due any minute now; but perhaps, Simone, if you do not feel well—’

Simone hardly seemed to be listening to him; she was following out her own train of thought.

‘She is—a strange woman, Raoul, a very strange woman. Do you know I—I have almost a horror of her.’

‘Simone!’

There was reproach in his voice, and she was quick to feel it.

‘Yes, yes, I know, you are like all Frenchmen, Raoul. To you a mother is sacred and it is unkind of me to feel like that about her when she grieves so for her lost child. But—I cannot explain it, she is so big and black, and her hands—have you ever noticed her hands, Raoul? Great big strong hands, as strong as a man’s. Ah!’

She gave a little shiver and closed her eyes. Raoul withdrew his arm and spoke almost coldly.

‘I really cannot understand you, Simone. Surely you, a woman, should have nothing but sympathy for another woman, a mother bereft of her only child.’

Simone made a gesture of impatience.

‘Ah, it is you who do not understand, my friend! One cannot help these things. The first moment I saw her I felt—’

She flung her hands out.

‘Fear! You remember, it was a long time before I would consent to sit for her? I felt sure in some way she would bring me misfortune.’

Raoul shrugged his shoulders.

‘Whereas, in actual fact, she brought you the exact opposite,’ he said drily. ‘All the sittings have been attended with marked success. The spirit of the little Amelie was able to control you at once, and the materializations have really been striking. Professor Roche ought really to have been present at the last one.’

‘Materializations,’ said Simone in a low voice. ‘Tell me, Raoul (you know that I know nothing of what takes place while I am in the trance), are the materializations really so wonderful?’

He nodded enthusiastically.

‘At the first few sittings the figure of the child was visible in a kind of nebulous haze,’ he explained, ‘but at the last séance—’

‘Yes?’

He spoke very softly.

‘Simone, the child that stood there was an actual living child of flesh and blood. I even touched her—but seeing that the touch was acutely painful to you, I would not permit Madame Exe to do the same. I was afraid that her self-control might break down, and that some harm to you might result.’

Simone turned away again towards the window.

‘I was terribly exhausted when I woke,’ she murmured. ‘Raoul, are you sure—are you really sure that all this is right? You know what dear old Elise thinks, that I am trafficking with the devil?’

She laughed rather uncertainly.

‘You know what I believe,’ said Raoul gravely. ‘In the handling of the unknown there must always be danger, but the cause is a noble one, for it is the cause of Science. All over the world there have been martyrs to Science, pioneers who have paid the price so that others may follow safely in their footsteps. For ten years now you have worked for Science at the cost of a terrific nervous strain. Now your part is done, from today onward you are free to be happy.’

She smiled at him affectionately, her calm restored. Then she glanced quickly up at the clock.

‘Madame Exe is late,’ she murmured. ‘She may not come.’

‘I think she will,’ said Raoul. ‘Your clock is a little fast, Simone.’

Simone moved about the room, rearranging an ornament here and there.

‘I wonder who she is, this Madame Exe?’ she observed. ‘Where she comes from, who her people are? It is strange that we know nothing about her.’

Raoul shrugged his shoulders.

‘Most people remain incognito if possible when they come to a medium,’ he observed. ‘It is an elementary precaution.’

‘I suppose so,’ agreed Simone listlessly.

A little china vase she was holding slipped from her fingers and broke to pieces on the tiles of the fireplace. She turned sharply on Raoul.

‘You see,’ she murmured, ‘I am not myself. Raoul, would you think me very—very cowardly if I told Madame Exe I could not sit today?’

His look of pained astonishment made her redden.

‘You promised, Simone—’ he began gently.

She backed against the wall.

‘I won’t do it, Raoul. I won’t do it.’

And again that glance of his, tenderly reproachful, made her wince.

‘It is not of the money I am thinking, Simone, though you must realize that the money this woman has offered you for the last sitting is enormous—simply enormous.’

She interrupted him defiantly.

‘There are things that matter more than money.’

‘Certainly there are,’ he agreed warmly. ‘That is just what I am saying. Consider—this woman is a mother, a mother who has lost her only child. If you are not really ill, if it is only a whim on your part—you can deny a rich woman a caprice, can you deny a mother one last sight of her child?’

The medium flung her hands out despairingly in front of her.

‘Oh, you torture me,’ she murmured. ‘All the same you are right. I will do as you wish, but I know now what I am afraid of—it is the word “mother”.’

‘Simone!’

‘There are certain primitive elementary forces, Raoul. Most of them have been destroyed by civilization, but motherhood stands where it stood at the beginning. Animals—human beings, they are all the same. A mother’s love for her child is like nothing else in the world. It knows no law, no pity, it dares all things and crushes down remorselessly all that stands in its path.’

She stopped, panting a little, then turned to him with a quick, disarming smile.

‘I am foolish today, Raoul. I know it.’

He took her hand in his.

‘Lie down for a minute or two,’ he urged. ‘Rest till she comes.’

‘Very well.’ She smiled at him and left the room.

Raoul remained for a minute or two lost in thought, then he strode to the door, opened it, and crossed the little hall. He went into a room the other side of it, a sitting room very much like the one he had left, but at one end was an alcove with a big armchair set in it. Heavy black velvet curtains were arranged so as to pull across the alcove. Elise was busy arranging the room. Close to the alcove she had set two chairs and a small round table. On the table was a tambourine, a horn, and some paper and pencils.

‘The last time,’ murmured Elise with grim satisfaction. ‘Ah, Monsieur, I wish it were over and done with.’

The sharp ting of an electric bell sounded.

‘There she is, that great gendarme of a woman,’ continued the old servant. ‘Why can’t she go and pray decently for her little one’s soul in a church, and burn a candle to Our Blessed Lady? Does not the good God know what is best for us?’

‘Answer the bell, Elise,’ said Raoul peremptorily.

She threw him a look, but obeyed. In a minute or two she returned ushering in the visitor.

‘I will tell my mistress you are here, Madame.’

Raoul came forward to shake hands with Madame Exe. Simone’s words floated back to his memory.

‘So big and so black.’

She was a big woman, and the heavy black of French mourning seemed almost exaggerated in her case. Her voice when she spoke was very deep.

‘I fear I am a little late, Monsieur.’

‘A few moments only,’ said Raoul, smiling. ‘Madame Simone is lying down. I am sorry to say she is far from well, very nervous and overwrought.’

Her hand, which she was just withdrawing, closed on his suddenly like a vice.

‘But she will sit?’ she demanded sharply.

‘Oh, yes, Madame.’

Madame Exe gave a sigh of relief, and sank into a chair, loosening one of the heavy black veils that floated round her.

‘Ah, Monsieur!’ she murmured, ‘you cannot imagine, you cannot conceive the wonder and the joy of these séances to me! My little one! My Amelie! To see her, to hear her, even—perhaps—yes, perhaps to be even able to—stretch out my hand and touch her.’

Raoul spoke quickly and peremptorily.

‘Madame Exe—how can I explain?—on no account must you do anything except under my express directions, otherwise there is the gravest danger.’

‘Danger to me?’

‘No, Madame,’ said Raoul, ‘to the medium. You must understand that the phenomena that occur are explained by Science in a certain way. I will put the matter very simply, using no technical terms. A spirit, to manifest itself, has to use the actual physical substance of the medium. You have seen the vapour of fluid issuing from the lips of the medium. This finally condenses and is built up into the physical semblance of the spirit’s dead body. But this ectoplasm we believe to be the actual substance of the medium. We hope to prove this some day by careful weighing and testing—but the great difficulty is the danger and pain which attends the medium on any handling of the phenomena. Were anyone to seize hold of the materialization roughly the death of the medium might result.’

Madame Exe had listened to him with close attention.

‘That is very interesting, Monsieur. Tell me, shall not a time come when the materialization shall advance so far that it shall be capable of detachment from its parent, the medium?’

‘That is a fantastic speculation, Madame.’

She persisted.

‘But, on the facts, not impossible?’

‘Quite impossible today.’

‘But perhaps in the future?’

He was saved from answering, for at that moment Simone entered. She looked languid and pale, but had evidently regained entire control of herself. She came forward and shook hands with Madame Exe, though Raoul noticed the faint shiver that passed through her as she did so.

‘I regret, Madame, to hear that you are indisposed,’ said Madame Exe.

‘It is nothing,’ said Simone rather brusquely. ‘Shall we begin?’

She went to the alcove and sat down in the armchair. Suddenly Raoul in his turn felt a wave of fear pass over him.

‘You are not strong enough,’ he exclaimed. ‘We had better cancel the séance. Madame Exe will understand.’

‘Monsieur!’

Madame Exe rose indignantly.

‘Yes, yes, it is better not, I am sure of it.’

‘Madame Simone promised me one last sitting.’

‘That is so,’ agreed Simone quietly, ‘and I am prepared to carry out my promise.’

‘I hold you to it, Madame,’ said the other woman.

‘I do not break my word,’ said Simone coldly. ‘Do not fear, Raoul,’ she added gently, ‘after all, it is for the last time—the last time, thank God.’

At a sign from her Raoul drew the heavy black curtains across the alcove. He also pulled the curtains of the window so that the room was in semi-obscurity. He indicated one of the chairs to Madame Exe and prepared himself to take the other. Madame Exe, however, hesitated.

‘You will pardon me, Monsieur, but—you understand I believe absolutely in your integrity and in that of Madame Simone. All the same, so that my testimony may be the more valuable, I took the liberty of bringing this with me.’

From her handbag she drew a length of fine cord.

‘Madame!’ cried Raoul. ‘This is an insult!’

‘A precaution.’

‘I repeat it is an insult.’

‘I don’t understand your objection, Monsieur,’ said Madame Exe coldly. ‘If there is no trickery you have nothing to fear.’

Raoul laughed scornfully.

‘I can assure you that I have nothing to fear, Madame. Bind me hand and foot if you will.’

His speech did not produce the effect he hoped for, for Madame Exe merely murmured unemotionally:

‘Thank you, Monsieur,’ and advanced upon him with her roll of cord.

Suddenly Simone from behind the curtain gave a cry.

‘No, no, Raoul, don’t let her do it.’

Madame Exe laughed derisively.

‘Madame is afraid,’ she observed sarcastically.

‘Yes, I am afraid.’

‘Remember what you are saying, Simone,’ cried Raoul. ‘Madame Exe is apparently under the impression that we are charlatans.’

‘I must make sure,’ said Madame Exe grimly.

She went methodically about her task, binding Raoul securely to his chair.

‘I must congratulate you on your knots, Madame,’ he observed ironically when she had finished. ‘Are you satisfied now?’

Madame Exe did not reply. She walked round the room examining the panelling of the walls closely. Then she locked the door leading into the hall, and, removing the key, returned to her chair.

‘Now,’ she said in an indescribable voice, ‘I am ready.’

The minutes passed. From behind the curtain the sound of Simone’s breathing became heavier and more stertorous. Then it died away altogether, to be succeeded by a series of moans. Then again there was silence for a little while, broken by the sudden clattering of the tambourine. The horn was caught up from the table and dashed to the ground. Ironic laughter was heard. The curtains of the alcove seemed to have been pulled back a little, the medium’s figure was just visible through the opening, her head fallen forward on her breast. Suddenly Madame Exe drew in her breath sharply. A ribbon-like stream of mist was issuing from the medium’s mouth. It condensed and began gradually to assume a shape, the shape of a little child.

‘Amelie! My little Amelie!’

The hoarse whisper came from Madame Exe. The hazy figure condensed still further. Raoul stared almost incredulously. Never had there been a more successful materialization. Now, surely it was a real child, a real flesh and blood child standing there.

‘Maman!’

The soft childish voice spoke.

‘My child!’ cried Madame Exe. ‘My child!’

She half-rose from her seat.

‘Be careful, Madame,’ cried Raoul warningly.

The materialization came hesitatingly through the curtains. It was a child. She stood there, her arms held out.

‘Maman!’

‘Ah!’ cried Madame Exe.

Again she half-rose from her seat.

‘Madame,’ cried Raoul, alarmed, ‘the medium—’

‘I must touch her,’ cried Madame Exe hoarsely.

She moved a step forward.

‘For God’s sake, Madame, control yourself,’ cried Raoul.

He was really alarmed now.

‘Sit down at once.’

‘My little one, I must touch her.’

‘Madame, I command you, sit down!’

He was writhing desperately in his bonds, but Madame Exe had done her work well; he was helpless. A terrible sense of impending disaster swept over him.

‘In the name of God, Madame, sit down!’ he shouted. ‘Remember the medium.’

Madame Exe paid no attention to him. She was like a woman transformed. Ecstasy and delight showed plainly in her face. Her outstretched hand touched the little figure that stood in the opening of the curtains. A terrible moan came from the medium.

‘My God!’ cried Raoul. ‘My God! This is terrible. The medium—’

Madame Exe turned on him with a harsh laugh.

‘What do I care for your medium?’ she cried. ‘I want my child.’

‘You are mad!’

‘My child, I tell you. Mine! My own! My own flesh and blood! My little one come back to me from the dead, alive and breathing.’

Raoul opened his lips, but no words would come. She was terrible, this woman! Remorseless, savage, absorbed by her own passion. The baby lips parted, and for the third time the same word echoed:

‘Maman!’

‘Come then, my little one,’ cried Madame Exe.

With a sharp gesture she caught up the child in her arms. From behind the curtains came a long-drawn scream of utter anguish.

‘Simone!’ cried Raoul. ‘Simone!’

He was aware vaguely of Madame Exe rushing past him, of the unlocking of the door, of the retreating footsteps down the stairs.

From behind the curtains there still sounded the terrible high long-drawn scream—such a scream as Raoul had never heard. It died away in a horrible kind of gurgle. Then there came the thud of a body falling …

Raoul was working like a maniac to free himself from his bonds. In his frenzy he accomplished the impossible, snapping the rope by sheer strength. As he struggled to his feet, Elise rushed in crying, ‘Madame!’

‘Simone!’ cried Raoul.

Together they rushed forward and pulled the curtain.

Raoul staggered back.

‘My God!’ he murmured. ‘Red—all red …’

Elise’s voice came beside him harsh and shaking.

‘So Madame is dead. It is ended. But tell me, Monsieur, what has happened. Why is Madame all shrunken away—why is she half her usual size? What has been happening here?’

‘I do not know,’ said Raoul.

His voice rose to a scream.

‘I do not know. I do not know. But I think—I am going mad … Simone! Simone!’

IN A GLASS DARKLY (#u72d0c14f-6048-54d2-bc79-9d8c3b113e8a)

I’ve no explanation of this story. I’ve no theories about the why and wherefore of it. It’s just a thing—that happened.

All the same, I sometimes wonder how things would have gone if I’d noticed at the time just that one essential detail that I never appreciated until so many years afterwards. If I had noticed it—well, I suppose the course of three lives would have been entirely altered. Somehow—that’s a very frightening thought.

For the beginning of it all, I’ve got to go back to the summer of 1914—just before the war—when I went down to Badgeworthy with Neil Carslake. Neil was, I suppose, about my best friend. I’d known his brother Alan too, but not so well. Sylvia, their sister, I’d never met. She was two years younger than Alan and three years younger than Neil. Twice, while we were at school together, I’d been going to spend part of the holidays with Neil at Badgeworthy and twice something had intervened. So it came about that I was twenty-three when I first saw Neil and Alan’s home.

We were to be quite a big party there. Neil’s sister Sylvia had just got engaged to a fellow called Charles Crawley. He was, so Neil said, a good deal older than she was, but a thoroughly decent chap and quite reasonably well-off.

We arrived, I remember, about seven o’clock in the evening. Everyone had gone to his room to dress for dinner. Neil took me to mine. Badgeworthy was an attractive, rambling old house. It had been added to freely in the last three centuries and was full of little steps up and down, and unexpected staircases. It was the sort of house in which it’s not easy to find your way about. I remember Neil promised to come and fetch me on his way down to dinner. I was feeling a little shy at the prospect of meeting his people for the first time. I remember saying with a laugh that it was the kind of house one expected to meet ghosts in the passages, and he said carelessly that he believed the place was said to be haunted but that none of them had ever seen anything, and he didn’t even know what form the ghost was supposed to take.

Then he hurried away and I set to work to dive into my suitcases for my evening clothes. The Carslakes weren’t well-off; they clung on to their old home, but there were no menservants to unpack for you or valet you.

Well, I’d just got to the stage of tying my tie. I was standing in front of the glass. I could see my own face and shoulders and behind them the wall of the room—a plain stretch of wall just broken in the middle by a door—and just as I finally settled my tie I noticed that the door was opening.

I don’t know why I didn’t turn around—I think that would have been the natural thing to do; anyway, I didn’t. I just watched the door swing slowly open—and as it swung I saw into the room beyond.

It was a bedroom—a larger room than mine—with two bedsteads in it, and suddenly I caught my breath.

For at the foot of one of those beds was a girl and round her neck were a pair of man’s hands and the man was slowly forcing her backwards and squeezing her throat as he did so, so that the girl was being slowly suffocated.

There wasn’t the least possibility of a mistake. What I saw was perfectly clear. What was being done was murder.

I could see the girl’s face clearly, her vivid golden hair, the agonized terror of her beautiful face, slowly suffusing with blood. Of the man I could see his back, his hands, and a scar that ran down the left side of his face towards his neck.

It’s taken some time to tell, but in reality only a moment or two passed while I stared dumbfounded. Then I wheeled round to the rescue …

And on the wall behind me, the wall reflected in the glass, there was only a Victorian mahogany wardrobe. No door open—no scene of violence. I swung back to the mirror. The mirror reflected only the wardrobe …

I passed my hands across my eyes. Then I sprang across the room and tried to pull forward the wardrobe and at that moment Neil entered by the other door from the passage and asked me what the hell I was trying to do.

He must have thought me slightly barmy as I turned on him and demanded whether there was a door behind the wardrobe. He said, yes, there was a door, it led into the next room. I asked him who was occupying the next room and he said people called Oldam—a Major Oldam and his wife. I asked him then if Mrs Oldam had very fair hair and when he replied drily that she was dark I began to realize that I was probably making a fool of myself. I pulled myself together, made some lame explanation and we went downstairs together. I told myself that I must have had some kind of hallucination—and felt generally rather ashamed and a bit of an ass.

And then—and then—Neil said, ‘My sister Sylvia,’ and I was looking into the lovely face of the girl I had just seen being suffocated to death … and I was introduced to her fiancé, a tall dark man with a scar down the left side of his face.

Well—that’s that. I’d like you to think and say what you’d have done in my place. Here was the girl—the identical girl—and here was the man I’d seen throttling her—and they were to be married in about a month’s time …

Had I—or had I not—had a prophetic vision of the future? Would Sylvia and her husband come down here to stay some time in the future, and be given that room (the best spare room) and would that scene I’d witnessed take place in grim reality?

What was I to do about it? Could I do anything? Would anyone—Neil—or the girl herself—would they believe me?

I turned the whole business over and over in my mind the week I was down there. To speak or not to speak? And almost at once another complication set in. You see, I fell in love with Sylvia Carslake the first moment I saw here … I wanted her more than anything on earth … And in a way that tied my hands.

And yet, if I didn’t say anything, Sylvia would marry Charles Crawley and Crawley would kill her …

And so, the day before I left, I blurted it all out to her. I said I expect she’d think me touched in the intellect or something, but I swore solemnly that I’d seen the thing just as I told it to her and that I felt if she was determined to marry Crawley, I ought to tell her my strange experience.

She listened very quietly. There was something in her eyes I didn’t understand. She wasn’t angry at all. When I’d finished, she just thanked me gravely. I kept repeating like an idiot, ‘I did see it. I really did see it,’ and she said, ‘I’m sure you did if you say so. I believe you.’

Well, the upshot was that I went off not knowing whether I’d done right or been a fool, and a week later Sylvia broke off her engagement to Charles Crawley.

After that the war happened, and there wasn’t much leisure for thinking of anything else. Once or twice when I was on leave, I came across Sylvia, but as far as possible I avoided her.

I loved her and wanted her just as badly as ever, but I felt somehow that it wouldn’t be playing the game. It was owing to me that she’d broken off her engagement to Crawley, and I kept saying to myself that I could only justify the action I had taken by making my attitude a purely disinterested one.

Then, in 1916, Neil was killed and it fell to me to tell Sylvia about his last moments. We couldn’t remain on formal footing after that. Sylvia had adored Neil and he had been my best friend. She was sweet—adorably sweet in her grief. I just managed to hold my tongue and went out again praying that a bullet might end the whole miserable business. Life without Sylvia wasn’t worth living.

But there was no bullet with my name on it. One nearly got me below the right ear and one was deflected by a cigarette case in my pocket, but I came through unscathed. Charles Crawley was killed in action at the beginning of 1918.

Somehow that made a difference. I came home in the autumn of 1918 just before the Armistice and I went straight to Sylvia and told her that I loved her. I hadn’t much hope that she’d care for me straight away, and you could have knocked me down with a feather when she asked me why I hadn’t told her sooner. I stammered out something about Crawley and she said, ‘But why did you think I broke it off with him?’ and then she told me that she’d fallen in love with me just as I’d done with her—from the very first minute.

I said I thought she’d broken off her engagement because of the story I told her and she laughed scornfully and said that if you loved a man you wouldn’t be as cowardly as that, and we went over that old vision of mine again and agreed that it was queer, but nothing more.

Well, there’s nothing much to tell for some time after that. Sylvia and I were married and we were very happy. But I realized, as soon as she was really mine, that I wasn’t cut out for the best kind of husband. I loved Sylvia devotedly, but I was jealous, absurdly jealous of anyone she so much as smiled at. It amused her at first, I think she even rather liked it. It proved, at least, how devoted I was.

As for me, I realized quite fully and unmistakably that I was not only making a fool of myself, but that I was endangering all the peace and happiness of our life together. I knew, I say, but I couldn’t change. Every time Sylvia got a letter she didn’t show to me I wondered who it was from. If she laughed and talked with any man, I found myself getting sulky and watchful.

At first, as I say, Sylvia laughed at me. She thought it a huge joke. Then she didn’t think the joke so funny. Finally she didn’t think it a joke at all—

And slowly, she began to draw away from me. Not in any physical sense, but she withdrew her secret mind from me. I no longer knew what her thoughts were. She was kind—but sadly, as thought from a long distance.

Little by little I realized that she no longer loved me. Her love had died and it was I who had killed it …

The next step was inevitable, I found myself waiting for it—dreading it …

Then Derek Wainwright came into our lives. He had everything that I hadn’t. He had brains and a witty tongue. He was good-looking, too, and—I’m forced to admit it—a thoroughly good chap. As soon as I saw him I said to myself, ‘This is just the man for Sylvia …’

She fought against it. I know she struggled … but I gave her no help. I couldn’t. I was entrenched in my gloomy, sullen reserve. I was suffering like hell—and I couldn’t stretch out a finger to save myself. I didn’t help her. I made things worse. I let loose at her one day—a string of savage, unwarranted abuse. I was nearly mad with jealousy and misery. The things I said were cruel and untrue and I knew while I was saying them how cruel and how untrue they were. And yet I took a savage pleasure in saying them …

I remember how Sylvia flushed and shrank …

I drove her to the edge of endurance.

I remember she said, ‘This can’t go on …’

When I came home that night the house was empty—empty. There was a note—quite in the traditional fashion.

In it she said that she was leaving me—for good. She was going down to Badgeworthy for a day or two. After that she was going to the one person who loved her and needed her. I was to take that as final.

I suppose that up to then I hadn’t really believed my own suspicions. This confirmation in black and white of my worst fears sent me raving mad. I went down to Badgeworthy after her as fast as the car would take me.

She had just changed her frock for dinner, I remember, when I burst into the room. I can see her face—startled—beautiful—afraid.

I said, ‘No one but me shall ever have you. No one.’

And I caught her throat in my hands and gripped it and bent her backwards.

And suddenly I saw our reflection in the mirror. Sylvia choking and myself strangling her, and the scar on my cheek where the bullet grazed it under the right ear.

No—I didn’t kill her. That sudden revelation paralysed me and I loosened my grasp and let her slip on to the floor …

And then I broke down—and she comforted me … Yes, she comforted me.

I told her everything and she told me that by the phrase ‘the one person who loved and needed her’ she had meant her brother Alan … We saw into each other’s hearts that night, and I don’t think, from that moment, that we ever drifted away from each other again …

It’s a sobering thought to go through life with—that, but for the grace of God and a mirror, one might be a murderer …

One thing did die that night—the devil of jealousy that had possessed me so long …

But I wonder sometimes—suppose I hadn’t made that initial mistake—the scar on the left cheek—when really it was the right—reversed by the mirror … Should I have been so sure the man was Charles Crawley? Would I have warned Sylvia? Would she be married to me—or to him?

Or are the past and the future all one?

I’m a simple fellow—and I can’t pretend to understand these things—but I saw what I saw—and because of what I saw, Sylvia and I are together in the old-fashioned words—till death do us part. And perhaps beyond …

S.O.S. (#u72d0c14f-6048-54d2-bc79-9d8c3b113e8a)

‘Ah!’ said Mr Dinsmead appreciatively.

He stepped back and surveyed the round table with approval. The firelight gleamed on the coarse white tablecloth, the knives and forks, and the other table appointments.

‘Is—is everything ready?’ asked Mrs Dinsmead hesitatingly. She was a little faded woman, with colourless face, meagre hair scraped back from her forehead, and a perpetually nervous manner.

‘Everything’s ready,’ said her husband with a kind of ferocious geniality.

He was a big man, with stooping shoulders, and a broad red face. He had little pig’s eyes that twinkled under his bushy brows, and a big jowl devoid of hair.

‘Lemonade?’ suggested Mrs Dinsmead, almost in a whisper.

Her husband shook his head.

‘Tea. Much better in every way. Look at the weather, streaming and blowing. A nice cup of hot tea is what’s needed for supper on an evening like this.’

He winked facetiously, then fell to surveying the table again.

‘A good dish of eggs, cold corned beef, and bread and cheese. That’s my order for supper. So come along and get it ready, Mother. Charlotte’s in the kitchen waiting to give you a hand.’

Mrs Dinsmead rose, carefully winding up the ball of her knitting.

‘She’s grown a very good-looking girl,’ she murmured. ‘Sweetly pretty, I say.’

‘Ah!’ said Mr Dinsmead. ‘The mortal image of her Ma! So go along with you, and don’t let’s waste any more time.’

He strolled about the room humming to himself for a minute or two. Once he approached the window and looked out.

‘Wild weather,’ he murmured to himself. ‘Not much likelihood of our having visitors tonight.’

Then he too left the room.

About ten minutes later Mrs Dinsmead entered bearing a dish of fried eggs. Her two daughters followed, bringing in the rest of the provisions. Mr Dinsmead and his son Johnnie brought up the rear. The former seated himself at the head of the table.

‘And for what we are to receive, etcetera,’ he remarked humorously. ‘And blessings on the man who first thought of tinned foods. What would we do, I should like to know, miles from anywhere, if we hadn’t a tin now and then to fall back upon when the butcher forgets his weekly call?’

He proceeded to carve corned beef dexterously.

‘I wonder who ever thought of building a house like this, miles from anywhere,’ said his daughter Magdalen pettishly. ‘We never see a soul.’

‘No,’ said her father. ‘Never a soul.’

‘I can’t think what made you take it, Father,’ said Charlotte.

‘Can’t you, my girl? Well, I had my reasons—I had my reasons.’

His eyes sought his wife’s furtively, but she frowned.

‘And haunted too,’ said Charlotte. ‘I wouldn’t sleep alone here for anything.’

‘Pack of nonsense,’ said her father. ‘Never seen anything, have you? Come now.’

‘Not seen anything perhaps, but—’

‘But what?’

Charlotte did not reply, but she shivered a little. A great surge of rain came driving against the window-pane, and Mrs Dinsmead dropped a spoon with a tinkle on the tray.

‘Not nervous are you, Mother?’ said Mr Dinsmead. ‘It’s a wild night, that’s all. Don’t you worry, we’re safe here by our fireside, and not a soul from outside likely to disturb us. Why, it would be a miracle if anyone did. And miracles don’t happen. No,’ he added as though to himself, with a kind of peculiar satisfaction. ‘Miracles don’t happen.’

As the words left his lips there came a sudden knocking at the door. Mr Dinsmead stayed as though petrified.

‘Whatever’s that?’ he muttered. His jaw fell.

Mrs Dinsmead gave a little whimpering cry and pulled her shawl up round her. The colour came into Magdalen’s face and she leant forward and spoke to her father.

‘The miracle has happened,’ she said. ‘You’d better go and let whoever it is in.’

Twenty minutes earlier Mortimer Cleveland had stood in the driving rain and mist surveying his car. It was really cursed bad luck. Two punctures within ten minutes of each other, and here he was, stranded miles from anywhere, in the midst of these bare Wiltshire downs with night coming on, and no prospect of shelter. Serve him right for trying to take a shortcut. If only he had stuck to the main road! Now he was lost on what seemed a mere cart-track, and no idea if there were even a village anywhere near.

He looked round him perplexedly, and his eye was caught by a gleam of light on the hillside above him. A second later the mist obscured it once more, but, waiting patiently, he presently got a second glimpse of it. After a moment’s cogitation, he left the car and struck up the side of the hill.

Soon he was out of the mist, and he recognized the light as shining from the lighted window of a small cottage. Here, at any rate, was shelter. Mortimer Cleveland quickened his pace, bending his head to meet the furious onslaught of wind and rain which seemed to be trying its best to drive him back.

Cleveland was in his own way something of a celebrity though doubtless the majority of folks would have displayed complete ignorance of his name and achievements. He was an authority on mental science and had written two excellent text books on the subconscious. He was also a member of the Psychical Research Society and a student of the occult in so far as it affected his own conclusions and line of research.

He was by nature peculiarly susceptible to atmosphere, and by deliberate training he had increased his own natural gift. When he had at last reached the cottage and rapped at the door, he was conscious of an excitement, a quickening of interest, as though all his faculties had suddenly been sharpened.

The murmur of voices within had been plainly audible to him. Upon his knock there came a sudden silence, then the sound of a chair being pushed back along the floor. In another minute the door was flung open by a boy of about fifteen. Cleveland could look straight over his shoulder upon the scene within.

It reminded him of an interior by some Dutch Master. A round table spread for a meal, a family party sitting round it, one or two flickering candles and the firelight’s glow over all. The father, a big man, sat one side of the table, a little grey woman with a frightened face sat opposite him. Facing the door, looking straight at Cleveland, was a girl. Her startled eyes looked straight into his, her hand with a cup in it was arrested halfway to her lips.

She was, Cleveland saw at once, a beautiful girl of an extremely uncommon type. Her hair, red gold, stood out round her face like a mist, her eyes, very far apart, were a pure grey. She had the mouth and chin of an early Italian Madonna.

There was a moment’s dead silence. Then Cleveland stepped into the room and explained his predicament. He brought his trite story to a close, and there was another pause harder to understand. At last, as though with an effort, the father rose.

‘Come in, sir—Mr Cleveland, did you say?’

‘That is my name,’ said Mortimer, smiling.

‘Ah! yes. Come in, Mr Cleveland. Not weather for a dog outside, is it? Come in by the fire. Shut the door, can’t you, Johnnie? Don’t stand there half the night.’

Cleveland came forward and sat on a wooden stool by the fire. The boy Johnnie shut the door.

‘Dinsmead, that’s my name,’ said the other man. He was all geniality now. ‘This is the Missus, and these are my two daughters, Charlotte and Magdalen.’

For the first time, Cleveland saw the face of the girl who had been sitting with her back to him, and saw that, in a totally different way, she was quite as beautiful as her sister. Very dark, with a face of marble pallor, a delicate aquiline nose, and a grave mouth. It was a kind of frozen beauty, austere and almost forbidding. She acknowledged her father’s introduction by bending her head, and she looked at him with an intent gaze that was searching in character. It was as though she were summing him up, weighing him in the balance of her young judgement.

‘A drop of something to drink, eh, Mr Cleveland?’

‘Thank you,’ said Mortimer. ‘A cup of tea will meet the case admirably.’

Mr Dinsmead hesitated a minute, then he picked up the five cups, one after another, from the table and emptied them into the slop bowl.

‘This tea’s cold,’ he said brusquely. ‘Make us some more, will you, Mother?’

Mrs Dinsmead got up quickly and hurried off with the teapot. Mortimer had an idea that she was glad to get out of the room.

The fresh tea soon came, and the unexpected guest was plied with viands.

Mr Dinsmead talked and talked. He was expansive, genial, loquacious. He told the stranger all about himself. He’d lately retired from the building trade—yes, made quite a good thing of it. He and the Missus thought they’d like a bit of country air—never lived in the country before. Wrong time of year to choose, of course, October and November, but they didn’t want to wait. ‘Life’s uncertain, you know, sir.’ So they had taken this cottage. Eight miles from anywhere, and nineteen miles from anything you could call a town. No, they didn’t complain. The girls found it a bit dull, but he and mother enjoyed the quiet.

So he talked on, leaving Mortimer almost hypnotized by the easy flow. Nothing here, surely, but rather commonplace domesticity. And yet, at that first glimpse of the interior, he had diagnosed something else, some tension, some strain, emanating from one of those five people—he didn’t know which. Mere foolishness, his nerves were all awry! They were all startled by his sudden appearance—that was all.

He broached the question of a night’s lodging, and was met with a ready response.

‘You’ll have to stop with us, Mr Cleveland. Nothing else for miles around. We can give you a bedroom, and though my pyjamas may be a bit roomy, why, they’re better than nothing, and your own clothes will be dry by morning.’

‘It’s very good of you.’

‘Not at all,’ said the other genially. ‘As I said just now, one couldn’t turn away a dog on a night like this. Magdalen, Charlotte, go up and see to the room.’

The two girls left the room. Presently Mortimer heard them moving about overhead.

‘I can quite understand that two attractive young ladies like your daughters might find it dull here,’ said Cleveland.

‘Good lookers, aren’t they?’ said Mr Dinsmead with fatherly pride. ‘Not much like their mother or myself. We’re a homely pair, but much attached to each other. I’ll tell you that, Mr Cleveland. Eh, Maggie, isn’t that so?’

Mrs Dinsmead smiled primly. She had started knitting again. The needles clicked busily. She was a fast knitter.

Presently the room was announced ready, and Mortimer, expressing thanks once more, declared his intention of turning in.

‘Did you put a hot-water bottle in the bed?’ demanded Mrs Dinsmead, suddenly mindful of her house pride.

‘Yes, Mother, two.’

‘That’s right,’ said Dinsmead. ‘Go up with him, girls, and see that there’s nothing else he wants.’

Magdalen preceded him up the staircase, her candle held aloft. Charlotte came behind.

The room was quite a pleasant one, small and with a sloping roof, but the bed looked comfortable, and the few pieces of somewhat dusty furniture were of old mahogany. A large can of hot water stood in the basin, a pair of pink pyjamas of ample proportions were laid over a chair, and the bed was made and turned down.

Magdalen went over to the window and saw that the fastenings were secure. Charlotte cast a final eye over the washstand appointments. Then they both lingered by the door.

‘Good night, Mr Cleveland. You are sure there is everything?’

‘Yes, thank you, Miss Magdalen. I am ashamed to have given you both so much trouble. Good night.’

‘Good night.’

They went out, shutting the door behind them. Mortimer Cleveland was alone. He undressed slowly and thoughtfully. When he had donned Mr Dinsmead’s pink pyjamas he gathered up his own wet clothes and put them outside the door as his host had bade him. From downstairs he could hear the rumble of Dinsmead’s voice.

What a talker the man was! Altogether an odd personality—but indeed there was something odd about the whole family, or was it his imagination?

He went slowly back into his room and shut the door. He stood by the bed lost in thought. And then he started—

The mahogany table by the bed was smothered in dust. Written in the dust were three letters, clearly visible, S.O.S.

Mortimer stared as if he could hardly believe his eyes. It was confirmation of all his vague surmises and forebodings. He was right, then. Something was wrong in this house.

S.O.S. A call for help. But whose finger had written it in the dust? Magdalen’s or Charlotte’s? They had both stood there, he remembered, for a moment or two, before going out of the room. Whose hand had secretly dropped to the table and traced out those three letters?

The faces of the two girls came up before him. Magdalen’s, dark and aloof, and Charlotte’s, as he had seen it first, wide-eyed, startled, with an unfathomable something in her glance …

He went again to the door and opened it. The boom of Mr Dinsmead’s voice was no longer to be heard. The house was silent.

He thought to himself.

‘I can do nothing tonight. Tomorrow—well. We shall see.’

Cleveland woke early. He went down through the living-room, and out into the garden. The morning was fresh and beautiful after the rain. Someone else was up early, too. At the bottom of the garden, Charlotte was leaning on the fence staring out over the Downs. His pulse quickened a little as he went down to join her. All along he had been secretly convinced that it was Charlotte who had written the message. As he came up to her, she turned and wished him ‘Good morning’. Her eyes were direct and childlike, with no hint of a secret understanding in them.

‘A very good morning,’ said Mortimer, smiling. ‘The weather this morning is a contrast to last night.’

‘It is indeed.’

Mortimer broke off a twig from a tree near by. With it he began idly to draw on the smooth, sandy patch at his feet. He traced an S, then an O, then an S, watching the girl narrowly as he did so. But again he could detect no gleam of comprehension.

‘Do you know what these letters represent?’ he said abruptly.

Charlotte frowned a little. ‘Aren’t they what boats—liners—send out when they are in distress?’ she asked.

Mortimer nodded. ‘Someone wrote that on the table by my bed last night,’ he said quietly. ‘I thought perhaps you might have done so.’

She looked at him in wide-eyed astonishment.

‘I? Oh, no.’

He was wrong then. A sharp pang of disappointment shot through him. He had been so sure—so sure. It was not often that his intuitions led him astray.

‘You are quite certain?’ he persisted.

‘Oh, yes.’

They turned and went slowly together toward the house. Charlotte seemed preoccupied about something. She replied at random to the few observations he made. Suddenly she burst out in a low, hurried voice:

‘It—it’s odd your asking about those letters, S.O.S.; I didn’t write them, of course, but—I so easily might have done.’

He stopped and looked at her, and she went on quickly:

‘It sounds silly, I know, but I have been so frightened, so dreadfully frightened, and when you came in last night, it seemed like an—an answer to something.’

‘What are you frightened of?’ he asked quickly.

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know.’

‘I think—it’s the house. Ever since we came here it has been growing and growing. Everyone seems different somehow. Father, Mother, and Magdalen, they all seem different.’

Mortimer did not speak at once, and before he could do so, Charlotte went on again.

‘You know this house is supposed to be haunted?’

‘What?’ All his interest was quickened.

‘Yes, a man murdered his wife in it, oh, some years ago now. We only found out about it after we got here. Father says ghosts are all nonsense, but I—don’t know.’

Mortimer was thinking rapidly.

‘Tell me,’ he said in a businesslike tone, ‘was this murder committed in the room I had last night?’

‘I don’t know anything about that,’ said Charlotte.

‘I wonder now,’ said Mortimer half to himself, ‘yes, that may be it.’

Charlotte looked at him uncomprehendingly.

‘Miss Dinsmead,’ said Mortimer, gently, ‘have you ever had any reason to believe that you are mediumistic?’

She stared at him.

‘I think you know that you did write S.O.S. last night,’ he said quietly. ‘Oh! quite unconsciously, of course. A crime stains the atmosphere, so to speak. A sensitive mind such as yours might be acted upon in such a manner. You have been reproducing the sensations and impressions of the victim. Many years ago she may have written S.O.S. on that table, and you unconsciously reproduced her act last night.’

Charlotte’s face brightened.

‘I see,’ she said. ‘You think that is the explanation?’

A voice called her from the house, and she went in, leaving Mortimer to pace up and down the garden path. Was he satisfied with his own explanation? Did it cover the facts as he knew them? Did it account for the tension he had felt on entering the house last night?

Perhaps, and yet he still had the odd feeling that his sudden appearance had produced something very like consternation, he thought to himself:

‘I must not be carried away by the psychic explanation, it might account for Charlotte—but not for the others. My coming has upset them horribly, all except Johnnie. Whatever it is that’s the matter, Johnnie is out of it.’

He was quite sure of that, strange that he should be so positive, but there it was.

At that minute, Johnnie himself came out of the cottage and approached the guest.

‘Breakfast’s ready,’ he said awkwardly. ‘Will you come in?’

Mortimer noticed that the lad’s fingers were much stained. Johnnie felt his glance and laughed ruefully.

‘I’m always messing about with chemicals, you know,’ he said. ‘It makes Dad awfully wild sometimes. He wants me to go into building, but I want to do chemistry and research work.’

Mr Dinsmead appeared at the window ahead of them, broad, jovial, smiling, and at the sight of him all Mortimer’s distrust and antagonism re-awakened. Mrs Dinsmead was already seated at the table. She wished him ‘Good morning’ in her colourless voice, and he had again the impression that for some reason or other, she was afraid of him.

Magdalen came in last. She gave him a brief nod and took her seat opposite him.

‘Did you sleep well?’ she asked abruptly. ‘Was your bed comfortable?’

She looked at him very earnestly, and when he replied courteously in the affirmative he noticed something very like a flicker of disappointment pass over her face. What had she expected him to say, he wondered?

He turned to his host.

‘This lad of yours is interested in chemistry, it seems!’ he said pleasantly.

There was a crash. Mrs Dinsmead had dropped her tea cup.

‘Now then, Maggie, now then,’ said her husband.

It seemed to Mortimer that there was admonition, warning, in his voice. He turned to his guest and spoke fluently of the advantages of the building trade, and of not letting young boys get above themselves.

After breakfast, he went out in the garden by himself, and smoked. The time was clearly at hand when he must leave the cottage. A night’s shelter was one thing, to prolong it was difficult without an excuse, and what possible excuse could he offer? And yet he was singularly loath to depart.

Turning the thing over and over in his mind, he took a path that led round the other side of the house. His shoes were soled with crepe rubber, and made little or no noise. He was passing the kitchen window, when he heard Dinsmead’s words from within, and the words attracted his attention immediately.

‘It’s a fair lump of money, it is.’

Mrs Dinsmead’s voice answered. It was too faint in tone for Mortimer to hear the words, but Dinsmead replied:

‘Nigh on £60,000, the lawyer said.’

Mortimer had no intention of eavesdropping, but he retraced his steps very thoughtfully. The mention of money seemed to crystallize the situation. Somewhere or other there was a question of £60,000—it made the thing clearer—and uglier.

Magdalen came out of the house, but her father’s voice called her almost immediately, and she went in again. Presently Dinsmead himself joined his guest.

‘Rare good morning,’ he said genially. ‘I hope your car will be none the worse.’

‘Wants to find out when I’m going,’ thought Mortimer to himself.

Aloud he thanked Mr Dinsmead once more for his timely hospitality.

‘Not at all, not at all,’ said the other.

Magdalen and Charlotte came together out of the house, and strolled arm in arm to a rustic seat some little distance away. The dark head and the golden one made a pleasant contrast together, and on an impulse Mortimer said:

‘Your daughters are very unalike, Mr Dinsmead.’

The other who was just lighting his pipe gave a sharp jerk of the wrist, and dropped the match.

‘Do you think so?’ he asked. ‘Yes, well, I suppose they are.’

Mortimer had a flash of intuition.

‘But of course they are not both your daughters,’ he said smoothly.

He saw Dinsmead look at him, hesitate for a moment, and then make up his mind.

‘That’s very clever of you, sir,’ he said. ‘No, one of them is a foundling, we took her in as a baby and we have brought her up as our own. She herself has not the least idea of the truth, but she’ll have to know soon.’ He sighed.

‘A question of inheritance?’ suggested Mortimer quietly.

The other flashed a suspicious look at him.

Then he seemed to decide that frankness was best; his manner became almost aggressively frank and open.

‘It’s odd that you should say that, sir.’

‘A case of telepathy, eh?’ said Mortimer, and smiled.

‘It is like this, sir. We took her in to oblige the mother—for a consideration, as at the time I was just starting in the building trade. A few months ago I noticed an advertisement in the papers, and it seemed to me that the child in question must be our Magdalen. I went to see the lawyers, and there has been a lot of talk one way and another. They were suspicious—naturally, as you might say, but everything is cleared up now. I am taking the girl herself to London next week, she doesn’t know anything about it so far. Her father, it seems, was one of these rich Jewish gentlemen. He only learnt of the child’s existence a few months before his death. He set agents on to try and trace her, and left all his money to her when she should be found.’

Mortimer listened with close attention. He had no reason to doubt Mr Dinsmead’s story. It explained Magdalen’s dark beauty; explained too, perhaps, her aloof manner. Nevertheless, though the story itself might be true, something lay behind it undivulged.

But Mortimer had no intention of rousing the other’s suspicions. Instead, he must go out of his way to allay them.

‘A very interesting story, Mr Dinsmead,’ he said. ‘I congratulate Miss Magdalen. An heiress and a beauty, she has a great time ahead of her.’

‘She has that,’ agreed her father warmly, ‘and she’s a rare good girl too, Mr Cleveland.’

There was every evidence of hearty warmth in his manner.

‘Well,’ said Mortimer, ‘I must be pushing along now, I suppose. I have got to thank you once more, Mr Dinsmead, for your singularly well-timed hospitality.’

Accompanied by his host, he went into the house to bid farewell to Mrs Dinsmead. She was standing by the window with her back to them, and did not hear them enter. At her husband’s jovial: ‘Here’s Mr Cleveland come to say goodbye,’ she started nervously and swung round, dropping something which she held in her hand. Mortimer picked it up for her. It was a miniature of Charlotte done in the style of some twenty-five years ago. Mortimer repeated to her the thanks he had already proffered to her husband. He noticed again her look of fear and the furtive glances that she shot at him from beneath her eyelids.

The two girls were not in evidence, but it was not part of Mortimer’s policy to seem anxious to see them; also he had his own idea, which was shortly to prove correct.

He had gone about half a mile from the house on his way down to where he had left the car the night before, when the bushes on the side of the path were thrust aside, and Magdalen came out on the track ahead of him.

‘I had to see you,’ she said.

‘I expected you,’ said Mortimer. ‘It was you who wrote S.O.S. on the table in my room last night, wasn’t it?’

Magdalen nodded.

‘Why?’ asked Mortimer gently.

The girl turned aside and began pulling off leaves from a bush.

‘I don’t know,’ she said, ‘honestly, I don’t know.’

‘Tell me,’ said Mortimer.

Magdalen drew a deep breath.

‘I am a practical person,’ she said, ‘not the kind of person who imagines things or fancies them. You, I know, believe in ghosts and spirits. I don’t, and when I tell you that there is something very wrong in that house,’ she pointed up the hill, ‘I mean that there is something tangibly wrong; it’s not just an echo of the past. It has been coming on ever since we’ve been there. Every day it grows worse, Father is different, Mother is different, Charlotte is different.’

Mortimer interposed. ‘Is Johnnie different?’ he asked.

Magdalen looked at him, a dawning appreciation in her eyes. ‘No,’ she said, ‘now I come to think of it, Johnnie is not different. He is the only one who’s—who’s untouched by it all. He was untouched last night at tea.’

‘And you?’ asked Mortimer.

‘I was afraid—horribly afraid, just like a child—without knowing what it was I was afraid of. And father was—queer, there’s no other word for it, queer. He talked about miracles and then I prayed—actually prayed for a miracle, and you knocked on the door.’

She stopped abruptly, staring at him.

‘I seem mad to you, I suppose,’ she said defiantly.

‘No,’ said Mortimer, ‘on the contrary you seem extremely sane. All sane people have a premonition of danger if it is near them.’

‘You don’t understand,’ said Magdalen. ‘I was not afraid—for myself.’

‘For whom, then?’

But again Magdalen shook her head in a puzzled fashion. ‘I don’t know.’

She went on:

‘I wrote S.O.S. on an impulse. I had an idea—absurd, no doubt, that they would not let me speak to you—the rest of them, I mean. I don’t know what it was I meant to ask you to do. I don’t know now.’

‘Never mind,’ said Mortimer. ‘I shall do it.’

‘What can you do?’

Mortimer smiled a little.

‘I can think.’

She looked at him doubtfully.

‘Yes,’ said Mortimer, ‘a lot can be done that way, more than you would ever believe. Tell me, was there any chance word or phrase that attracted your attention just before the meal last evening?’

Magdalen frowned. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said. ‘At least I heard Father say something to Mother about Charlotte being the living image of her, and he laughed in a very queer way, but—there’s nothing odd in that, is there?’

‘No,’ said Mortimer slowly, ‘except that Charlotte is not like your mother.’

He remained lost in thought for a minute or two, then looked up to find Magdalen watching him uncertainly.

‘Go home, child,’ he said, ‘and don’t worry; leave it in my hands.’

She went obediently up the path towards the cottage. Mortimer strolled on a little further, then threw himself down on the green turf. He closed his eyes, detached himself from conscious thought or effort, and let a series of pictures flit at will across his mind.

Johnnie! He always came back to Johnnie. Johnnie, completely innocent, utterly free from all the network of suspicion and intrigue, but nevertheless the pivot round which everything turned. He remembered the crash of Mrs Dinsmead’s cup on her saucer at breakfast that morning. What had caused her agitation? A chance reference on his part to the lad’s fondness for chemicals? At the moment he had not been conscious of Mr Dinsmead, but he saw him now clearly, as he sat, his teacup poised halfway to his lips.

That took him back to Charlotte, as he had seen her when the door opened last night. She had sat staring at him over the rim of her teacup. And swiftly on that followed another memory. Mr Dinsmead emptying teacups one after the other, and saying ‘this tea is cold’.

He remembered the steam that went up. Surely the tea had not been so very cold after all?

Something began to stir in his brain. A memory of something read not so very long ago, within a month perhaps. Some account of a whole family poisoned by a lad’s carelessness. A packet of arsenic left in the larder had all dripped through on the bread below. He had read it in the paper. Probably Mr Dinsmead had read it too.

Things began to grow clearer …

Half an hour later, Mortimer Cleveland rose briskly to his feet.

It was evening once more in the cottage. The eggs were poached tonight and there was a tin of brawn. Presently Mrs Dinsmead came in from the kitchen bearing the big teapot. The family took their places round the table.

‘A contrast to last night’s weather,’ said Mrs Dinsmead, glancing towards the window.

‘Yes,’ said Mr Dinsmead, ‘it’s so still tonight that you could hear a pin drop. Now then, Mother, pour out, will you?’

Mrs Dinsmead filled the cups and handed them round the table. Then, as she put the teapot down, she gave a sudden little cry and pressed her hand to her heart. Mr Dinsmead swung round his chair, following the direction of her terrified eyes. Mortimer Cleveland was standing in the doorway.

He came forward. His manner was pleasant and apologetic.

‘I’m afraid I startled you,’ he said. ‘I had to come back for something.’

‘Back for something,’ cried Mr Dinsmead. His face was purple, his veins swelling. ‘Back for what, I should like to know?’

‘Some tea,’ said Mortimer.

With a swift gesture he took something from his pocket, and, taking up one of the teacups from the table, emptied some of its contents into a little test-tube he held in his left hand.

‘What—what are you doing?’ gasped Mr Dinsmead. His face had gone chalky-white, the purple dying out as if by magic. Mrs Dinsmead gave a thin, high, frightened cry.

‘You read the papers, I think, Mr Dinsmead? I am sure you do. Sometimes one reads accounts of a whole family being poisoned, some of them recover, some do not. In this case, one would not. The first explanation would be the tinned brawn you were eating, but supposing the doctor to be a suspicious man, not easily taken in by the tinned food theory? There is a packet of arsenic in your larder. On the shelf below it is a packet of tea. There is a convenient hole in the top shelf, what more natural to suppose then that the arsenic found its way into the tea by accident? Your son Johnnie might be blamed for carelessness, nothing more.’

‘I—I don’t know what you mean,’ gasped Dinsmead.

‘I think you do,’ Mortimer took up a second teacup and filled a second test-tube. He fixed a red label to one and a blue label to the other.

‘The red-labelled one,’ he said, ‘contains tea from your daughter Charlotte’s cup, the other from your daughter Magdalen’s. I am prepared to swear that in the first I shall find four or five times the amount of arsenic than in the latter.’

‘You are mad,’ said Dinsmead.

‘Oh! dear me, no. I am nothing of the kind. You told me today, Mr Dinsmead, that Magdalen is your daughter. Charlotte was the child you adopted, the child who was so like her mother that when I held a miniature of that mother in my hand today I mistook it for one of Charlotte herself. Your own daughter was to inherit the fortune, and since it might be impossible to keep your supposed daughter Charlotte out of sight, and someone who knew the mother might have realized the truth of the resemblance, you decided on, well—a pinch of white arsenic at the bottom of a teacup.’

Mrs Dinsmead gave a sudden high cackle, rocking herself to and fro in violent hysterics.

‘Tea,’ she squeaked, ‘that’s what he said, tea, not lemonade.’

‘Hold your tongue, can’t you?’ roared her husband wrathfully.

Mortimer saw Charlotte looking at him, wide-eyed, wondering, across the table. Then he felt a hand on his arm, and Magdalen dragged him out of earshot.

‘Those,’ she pointed at the phials—‘Daddy. You won’t—’

Mortimer laid his hand on her shoulder. ‘My child,’ he said, ‘you don’t believe in the past. I do. I believe in the atmosphere of this house. If he had not come to it, perhaps—I say perhaps—your father might not have conceived the plan he did. I keep these two test-tubes to safeguard Charlotte now and in the future. Apart from that, I shall do nothing, in gratitude, if you will, to that hand that wrote S.O.S.’

THE ADVENTURE OF THE EGYPTIAN TOMB (#u72d0c14f-6048-54d2-bc79-9d8c3b113e8a)

I have always considered that one of the most thrilling and dramatic of the many adventures I have shared with Poirot was that of our investigation into the strange series of deaths which followed upon the discovery and opening of the Tomb of King Men-her-Ra.

Hard upon the discovery of the Tomb of Tutankh-Amen by Lord Carnarvon, Sir John Willard and Mr Bleibner of New York, pursuing their excavations not far from Cairo, in the vicinity of the Pyramids of Gizeh, came unexpectedly on a series of funeral chambers. The greatest interest was aroused by their discovery. The Tomb appeared to be that of King Men-her-Ra, one of those shadowy kings of the Eighth Dynasty, when the Old Kingdom was falling to decay. Little was known about this period, and the discoveries were fully reported in the newspapers.

An event soon occurred which took a profound hold on the public mind. Sir John Willard died quite suddenly of heart failure.

The more sensational newspapers immediately took the opportunity of reviving all the old superstitious stories connected with the ill luck of certain Egyptian treasures. The unlucky Mummy at the British Museum, that hoary old chestnut, was dragged out with fresh zest, was quietly denied by the Museum, but nevertheless enjoyed all its usual vogue.

A fortnight later Mr Bleibner died of acute blood poisoning, and a few days afterwards a nephew of his shot himself in New York. The ‘Curse of Men-her-Ra’ was the talk of the day, and the magic power of dead-and-gone Egypt was exalted to a fetish point.

It was then that Poirot received a brief note from Lady Willard, widow of the dead archaeologist, asking him to go and see her at her house in Kensington Square. I accompanied him.

Lady Willard was a tall, thin woman, dressed in deep mourning. Her haggard face bore eloquent testimony to her recent grief.

‘It is kind of you to have come so promptly, Monsieur Poirot.’

‘I am at your service, Lady Willard. You wished to consult me?’

‘You are, I am aware, a detective, but it is not only as a detective that I wish to consult you. You are a man of original views, I know, you have imagination, experience of the world, tell me, Monsieur Poirot, what are your views on the supernatural?’

Poirot hesitated for a moment before he replied. He seemed to be considering. Finally he said:

‘Let us not misunderstand each other, Lady Willard. It is not a general question that you are asking me there. It has a personal application, has it not? You are referring obliquely to the death of your late husband?’

‘That is so,’ she admitted.

‘You want me to investigate the circumstances of his death?’