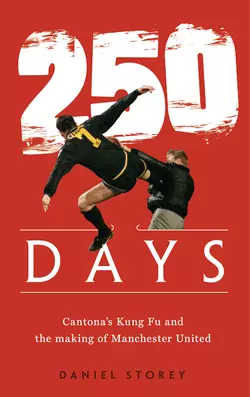

250 Days

Daniel Storey

An incredibly entertaining and perceptive look at the most controversial moment in Premier League history.25th January 1995 A cold winter’s evening. Manchester United away against Crystal Palace at a packed-out Selhurst Park. Eric Cantona, United's mercurial talisman, has been man-marked closely all game by Richard Shaw and become increasingly frustrated. In the 48th minute, Cantona’s temper boils over and he kicks out at Shaw. The ref shows him a red card. On his way off the pitch, a Palace fan rushes towards the hoardings to hurl abuse. The Frenchman loses it. He launches into the crowd, aiming a kung-fu kick at the fan’s chest. He is forcibly restrained and then taken off down the tunnel. The football world is stunned. Nothing like this has ever happened before.What followed has entered football folklore: the media furore, the seagulls following the trawler, and the longest domestic ban ever handed to a player; it would end up lasting 250 days. As Manchester United’s campaign stuttered towards a trophy-less conclusion, surrendering the league on the last day of the season and losing the FA Cup final, Cantona withdrew from the public eye. But, behind closed doors, Ferguson was planning the most remarkable of fresh starts for his star player and for a new-look United.250 Days tells the story in brilliant detail of one of the most turbulent times in United’s recent history. Showing Cantona in a new light, and the genius of Ferguson’s man management and vision in close relief, it is an incredibly entertaining and insightful look at the most controversial episode of the Premier League era.

(#u6c16cec0-3026-5836-828e-466d2f51abf6)

COPYRIGHT (#u6c16cec0-3026-5836-828e-466d2f51abf6)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Daniel Storey 2019

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photographs © Action Images/Reuters

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Daniel Storey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008320492

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008320508

Version: 2018-12-10

CONTENTS

Cover (#ub6daa8c8-1d10-5667-862b-b2c262e19727)

Title Page (#ua444bf51-2b8a-5e62-a04a-1e218ca3e9da)

Copyright (#udeaed576-ddfd-5d63-90f7-f4526ae6a8de)

PRELUDE (#uaf8bfdeb-b792-53a7-8a41-24475775d966)

‘Are you big enough for me?’ (#uaf8bfdeb-b792-53a7-8a41-24475775d966)

DAY 1 (#ue0d2ec66-9a8f-5481-964d-8b3eb2d22f60)

‘Go on, Cantona, have an early shower’ (#ue0d2ec66-9a8f-5481-964d-8b3eb2d22f60)

DAY 3 (#u27b6e213-0243-5cd8-8737-add32731bc12)

‘Good on you Eric’ (#u27b6e213-0243-5cd8-8737-add32731bc12)

DAY 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘When someone is doing well we have to knock them down’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘When seagulls follow the trawler’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 109 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Only a fool would say it didn’t cost us the league’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 157 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘You have not let yourself be affected by all this bloody nonsense’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 196 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Obviously we don’t want to lose him’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 207 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘You can’t win anything with kids’ (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 250 (#litres_trial_promo)

‘A Mancunian version of Bastille Day’ (#litres_trial_promo)

POSTSCRIPT (#litres_trial_promo)

‘He opened my eyes to the indispensability of practice’ (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PRELUDE (#u6c16cec0-3026-5836-828e-466d2f51abf6)

‘Are you big enough for me?’

Eric Cantona was not the first foreign footballer in England, but he might well have been the most influential. No single player better represents English football’s rapid transformation from the working-class, kick-and-rush game of Division One – a sport that had largely remained the same for half a century – to the glamour and exoticism of the current Premier League.

Before the mid-1990s foreign players were a luxury item, mysterious circus animals tasked with performing for our entertainment. At that time, ‘foreign’ had a pejorative connotation: fancy, flash, weak-willed. Foreign imports could temporarily call England home, but it would never be their natural habitat. They would hate our weather, hate our food, hate the physicality of the game that we invented and then gave to the world. And they would soon leave for whence they had come.

That was odd, given the success of some memorable foreign imports in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa at Tottenham, Arnold Mühren and Frans Thijssen at Ipswich, Johnny Metgod at Nottingham Forest; all became fan favourites due to their natural talent and willingness to embrace the culture of their clubs. But their success did not provoke an immediate wave of immigration.

The first weekend of the inaugural Premier League in August 1992 demonstrated English football’s insular nature. The 22 clubs handed appearances to only 13 non-British players. Four of those were goalkeepers and another four (John Jensen, Michel Vonk, Gunnar Halle and Roland Nilsson) were defensively minded players.

A high percentage of foreign players in the Premier League’s early years were from northern European countries – Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands. They were preferred not only on account of their assumed comfort in dealing with the British climate, but also because they came from countries where English football was already a staple. One of the first questions asked by a club owner or manager when signing a foreign player was ‘Can he fit into the English game?’

‘Having supported and followed English football all my life, like every other Norwegian, it was a dream to play in England,’ former Swindon, Middlesbrough, Sheffield United and Bradford striker Jan Åge Fjørtoft says. ‘We had grown up with Match of the Day every Saturday night, you see.’

Of the others, Andrei Kanchelskis and Anders Limpar were two who had skill as their primary characteristic, but the pair started only 26 league games between them for Manchester United and Arsenal in 1992/93. Ronny Rosenthal was a workmanlike Israeli striker for Liverpool who had become the most expensive non-British player to join an English club in 1990. Polish winger Robert Warzycha was the first player from mainland Europe to score a Premier League goal – for Everton – but managed only 18 starts in the competition before being sold to Hungarian side Pécsi MFC.

The Premier League was therefore desperate for a poster boy. Clubs had the means to pay higher wages thanks to a broadcasting deal with Sky Sports worth an initial £304 million. Many of the top-flight stadia had been improved following the recommendations of the Taylor Report. The stage had changed; the actors had not. In late 1992 the Premier League was nothing more than the old First Division rolled in glitter and studded with rhinestones.

Enter Eric Cantona and Manchester United. In November 1992, in strolled a Marseillais enigma whose confidence was only matched by the size of his reputation. With Leeds United keen to get rid of their tempestuous Gallic star, Alex Ferguson believed he had found the player around whom he could build the first age of his dynasty.

‘If ever there was one player, anywhere in the world, that was made for Manchester United, it was Cantona,’ as Ferguson would subsequently say. ‘He swaggered in, stuck his chest out, raised his head and surveyed everything as though he were asking: “I’m Cantona. How big are you? Are you big enough for me?”’

More than any other player, it was Cantona who unlocked the door for the Premier League’s foreign revolution. He proved that the skill European and South American players stereotypically possessed need not exclude the passion and will to win of the old English First Division. Just as Glenn Hoddle and Terry Butcher – two fixtures of the England national team in the 1980s – were as disparate in style as it is possible to conceive, so too could foreign players come from any part of the footballing spectrum. If that now sounds like an unnecessary truism, it was far from obvious in 1992.

But Cantona became more than a trailblazer; he was a cultural and sporting icon. No single player was more responsible for the boom in replica shirt sales and merchandising (official or otherwise), while the ubiquity of Cantona’s face thanks to a sponsorship deal with Nike was new ground for English football. In a thousand playgrounds across the country, collars on school-uniform shirts were turned up as children mimicked the hallmark of their hero. For a few years every kid was Eric Cantona. If those children have now turned 30, many still harbour the same adoration.

Cantona’s personality could never have been so influential without talent. He scored 82 times in 185 games for Manchester United, but it was his style of play that was so unusual. Before the Premier League era there was very little tactical fluidity in English football. Defenders defended and attackers attacked, and players typically stayed in formation.

Cantona preferred a different method. He started as a nominal strike partner – usually to Mark Hughes or Andy Cole – but dropped deep in between the lines of defence and midfield, dragging immobile central defenders out of their position and comfort zone. Cantona’s technical expertise allowed him to link play effectively, and he became as renowned for his chance-creation as his finishing. Cantona is credited with 56 assists in 156 Premier League games. The only other strikers of his era to register more – Cole, Alan Shearer and Teddy Sheringham – all played at least 250 more matches.

Conversely, Cantona’s talent could never have been so influential without personality. Cantona was a leader of Manchester United not just because of his talent, but through sheer strength of character. As Roy Keane so eloquently put it: ‘Collar up, back straight, chest stuck out, he glided into the arena as if he owned the f***ing place. Any arena, but nowhere more effectively than Old Trafford. This was his stage. He loved it, the crowd loved him.’

Cantona’s unwavering self-belief – it bordered on swaggering arrogance – was not a natural trait, but a deliberate tool of his success. ‘I’ve said in the past that I could play single-handedly against eleven players and win,’ he wrote in Cantona on Cantona. ‘Give me a bicycle and I believe I can beat Chris Boardman’s one-hour record.’ In Cantona’s psyche there was no room for doubt. Doubt is what leads to fear, and if fear cannot be controlled it eventually defeats you.

The Cantona effect at Manchester United became extraordinarily influential, but he was doubted when he joined. In hindsight, Leeds and their manager Howard Wilkinson are mocked for letting Cantona go, but they made a profit on the transfer fee they had paid to Nîmes less than 12 months earlier and had endured a rocky relationship with the Frenchman. Cantona failed to click with striker Lee Chapman, and later revealed his unhappiness at Elland Road. Wilkinson did the same: ‘Eric is not prepared to abide by the rules and conditions which operate for everybody else here.’

‘I had a bad relationship with the manager, Wilkinson,’ Cantona told FourFourTwo in 2008. ‘We didn’t have the same views on football. I am more like a Manchester footballer. At Leeds, football was played the old way – I think you say kick then rush. If I don’t feel the environment is good, I don’t want to be there.’ Cantona is right to some extent, but underplays his own role in United’s ‘new way’.

Senior Manchester United players Gary Pallister, Steve Bruce and Bryan Robson all raised significant concerns among each other and to the club about Cantona’s reputation for upsetting team morale, but Lee Sharpe was the most candid. ‘This bloke’s a total nutter, what are we doing?’ he is quoted as saying. The national media were hardly warm in their congratulations to Ferguson for his signing.

But Ferguson realised that his club needed a shot in the arm. They had finished second to Leeds the previous season, but sat eighth in the table with summer signing Dion Dublin out injured. Ferguson’s team had won two of their previous 13 matches, and there were lingering doubts over the Scotsman’s job security. United had not won the league title for 25 years.

Ferguson spoke to then-France national team manager Gérard Houllier for advice on Cantona, but also leant on Michel Platini and journalist Erik Bielderman for their input. The conclusion from all three was that Cantona needed a father figure, while Ferguson needed a new leader. Both men fitted the other’s need perfectly. Cantona only had problems with authority when he did not respect it.

His impact was instantaneous. Manchester United won eight and drew two of his first ten league games, and the split across the whole of 1992/93 is striking: 1.5 points per league game before his arrival and 2.3 points per league game afterwards; 1.06 goals per league game before his arrival and 1.92 goals per league game afterwards. From being eighth in the league and nine points from the top, United finished the season as league champions, with a ten-point cushion to second place.

Alongside the results, Cantona changed the mood too. By New Year’s Day 1993 Ferguson was publicly enthusing about Cantona’s effect on every element of Manchester United. ‘More than at any time since I was playing, the club is alive,’ he said. ‘It’s as if the good old days are back and the major factor, as far as I’m concerned, is the Frenchman.’

Manchester United’s former greats lined up to pour on praise. ‘I can’t think of anyone who I would rather wear my crown,’ said Denis Law. George Best was even more effusive: ‘I would pay to watch Cantona play. There are not many players over the years I would say that about. He is a genius.’ Old Trafford had its new king.

But the appeal of Cantona lay not just in his achievement, but also the controversy. Like another famous No. 7 at Manchester United who courted headlines off the pitch as much as on it, Cantona’s misdemeanours did not detract from his legacy; they cemented it. Cantona’s popularity with supporters is explained very simply: he was one of them. Here was a superstar, but with the flaws of Everyman laid proudly bare for all to see.

Never were those flaws more exposed than at Selhurst Park on 25 January 1995. Cantona’s acrobatic assault on Matthew Simmons provoked one of the longest bans for an on-pitch offence in the history of English football, and created a media circus the like of which the sport had never witnessed. Moreover, it threatened to force Cantona’s departure from England in the same manner in which he had left France, ignominy trumping all else. Had this happened, Cantona’s reputation at Old Trafford would have been very different.

Ferguson risked his own reputation over Cantona, but also acceded to him. This is captured in one memorable Steve Bruce anecdote. The squad were invited to Manchester Town Hall for a civic reception, and required to wear club suits. Cantona turned up wearing flip-flops, ripped jeans and a long, multi-coloured coat. As captain, Bruce was instructed to tell the manager that several players weren’t happy with Cantona’s appearance, believing it to be disrespectful.

‘Fergie’s on the red wine,’ Bruce recalls. ‘He puts down his glass, looks over at Eric. “Tell them from me, Steve,” he says, “that if they can play like him next year, they can all come as fucking Joseph too.”’

So when Cantona did step out of line so spectacularly in January 1995, Ferguson inevitably felt let down and wrestled with his own moral compass as well as what was best for Manchester United. In sticking by his man, Ferguson doubled down his trust in an enigma when others in his position would have taken an alternative – and easier – route. It proved to be a masterstroke.

For all the focus on Cantona during the 250 days between kung-fu kick and return to the pitch, Manchester United changed too. Ferguson started an evolution that began with a mini-revolution: senior players were sold but not replaced, while extraordinary faith was placed in a crop of prodigious young talent. During that summer, with Manchester United neither the reigning Premier League nor FA Cup champions, Ferguson would have his judgement called into question. The great manager even admitted to doubting himself. That didn’t happen often.

The ‘Class of 92’, as they would be nicknamed in hindsight, were already on the fringes of United’s first team when Cantona assaulted Simmons, but Ferguson brought them to the front and centre of his vision in the Frenchman’s absence.

Cantona’s role in that process has been too easily overlooked. His ban enabled him to play tutor and mentor to a wonderful generation of academy graduates. In turn it helped establish Ferguson’s first dynasty as Manchester United manager.

‘He changed the mentality and changed the way of everything,’ Peter Schmeichel said. ‘All the kids we’ve seen grow up with Manchester United from that period, they’ve really benefited from that and you could go and speak to David Beckham, Gary Neville and Paul Scholes about him. They will always point to him, as he was the guy.’

It is wonderfully fitting that Cantona’s first game back, against Liverpool at Anfield, was the first match in which all six of the ‘Class of 92’ appeared in a Manchester United shirt: Gary Neville, Phil Neville, Nicky Butt and Ryan Giggs as starters, David Beckham and Paul Scholes as substitutes.

This is the story of Cantona’s lasting impact on Manchester United, told through the 250 days between assault and comeback. A man whose temperament was questioned when he signed ultimately failed to escape his imperfections. But rather than erode his and Ferguson’s legacy, it only helped to define both.

DAY 1 (#u6c16cec0-3026-5836-828e-466d2f51abf6)

‘Go on, Cantona, have an early shower’

At 8.57 pm, Steve Lindsell got the shot.

Lindsell had gone to Selhurst Park on a Wednesday evening to watch Manchester United try to move to the top of the Premier League and witness the third anniversary of Eric Cantona’s arrival in English football through the lens of his camera. He was positioned on the touchline, primed. He would hope to sell a few choice photos – a goal celebration, frustration etched onto a contorted face, a manager thrusting his hands in pockets to protect against the cold January night – to several media outlets.

Right place, right time. Midway through the second half, Lindsell hurriedly clicked his shutter and took the photos that captured the most outrageous moment of the Premier League’s first decade. The most famous footballer in the land had both feet off the ground. One was planted into the chest of a supporter. Around him, fans who had rushed to the ground after work, or paced the same walk from their homes as they had done a hundred times before, watched on. Just another home game had become a match they would never forget.

‘I snapped, and snapped again,’ Lindsell said. ‘I thought I had a good picture but couldn’t imagine the impact it would have. I went to my van outside Selhurst Park, printed the roll, which must have taken me 15 to 20 minutes, then sent the pictures. It was only the day afterwards that all hell broke loose.’

Before the 48th minute Cantona had been a passenger in an uneventful game. Palace, just outside the relegation zone on goal difference, had broken up play effectively and limited Manchester United to a series of half chances. This was largely due to the man-marking job done on Cantona by Palace central defender Richard Shaw, who had been instructed by manager Alan Smith to stay touch-tight to the Frenchman.

Smith and Shaw would later insist that the defender was merely doing his job, but Cantona spent the first half complaining about the physical treatment that referee Alan Wilkie had either failed to spot or chosen to ignore. The reality is that Shaw left his foot in on more than one occasion to both put Cantona off his game and try to rile the Frenchman. It was common practice at the time; the hallmarks of the old First Division hadn’t quite been erased.

Wilkie remembers Cantona chastising him as the players left the field at half-time – ‘No yellow cards!’ – and the Frenchman repeating the message as the players waited in the tunnel to come back out for the second half. But, as ever, it was Ferguson’s message that most stuck in Wilkie’s mind. ‘Why don’t you do your fucking job?’ was the Manchester United manager’s presumably rhetorical question. This was par for Ferguson’s course.

What is certainly true is that Ferguson had spoken to Cantona in the dressing room at half-time to warn him not to get involved in Shaw’s games. ‘Don’t get involved,’ he quotes himself as saying in his autobiography. ‘That is exactly what he wants. Keep the ball away from him. He thinks he is having a good game if he is tackling.’

As an experienced – and very capable – central defender, seeing Cantona’s frustration was only likely to make Shaw step up his strategy. You could hardly blame him. Palace could not hope to contend with United on ability.

‘It was all Shawsy’s fault as well,’ Shaw’s teammate John Salako later said with his tongue inserted in cheek. ‘Richard was the best man-marker ever. He had a job to do on Eric and he did it so well Eric got so frustrated he literally booted Shawsy up the arse. Eric lost the plot.’

Three minutes into the second half, Peter Schmeichel launched a goal kick forward and Shaw and Cantona clashed again. Shaw was certainly the first to commit an offence – the linesman flagged to indicate as such – but it was Cantona’s kick-out at Shaw that earned the wrath of the officials. It clearly constituted violent conduct, and Wilkie was left with no choice but to show Cantona a red card. On the touchline, Ferguson was incandescent with anger.

Later, in court, Cantona would accept Wilkie’s decision to send him off but complained at his treatment by Shaw. ‘In my opinion, his decision was correct,’ he said in a statement read out by his barrister David Poole, ‘although I had been repeatedly and painfully fouled in the course of the match.’

One of the direct results of the Cantona incident was that the rule was changed regarding post-red card events. Until the end of the 1994/95 season a player in English football would leave the field at the nearest point following their dismissal. Then followed what was a potentially long walk around the perimeter of the pitch to the tunnel, often passing large swathes of opposition supporters who had free rein to offer their own personalised farewell messages. From August 1995 onwards, players left the field in a direct line towards the tunnel. In hindsight, it is extraordinary that it was ever different.

It does not condone Cantona’s subsequent actions, but the atmosphere at Selhurst Park was notoriously raucous and there is no doubt that any opposition player making the walk in front of the Main Stand would have faced many hundreds of taunts and foul-mouthed tirades.

But for Cantona, that abuse was worse than usual because of who he was, where he came from and which team he played for. Twice Cantona can be seen looking up to the stands in response to particular fans, but after a momentary pause he walks on.

‘It wasn’t just the tackles and shirt pulling he had to deal with that night that pushed him over the edge,’ said then-teammate Gary Pallister in 2015. ‘It was the culmination of a lot of abuse Eric had to put up with at every ground he went to.

‘You wouldn’t believe the kind of vile verbal abuse that was directed at him when we arrived at opposition grounds and got off the bus. Even when we went to the horse races, Eric couldn’t escape it. I remember at one race meeting he was being spat on from a balcony in the enclosure above where we were standing. He was a target, there was no doubt about it.’

One of those supporters delighting in Cantona’s ignominious and premature departure from the pitch was 20-year-old Matthew Simmons. Eye-witnesses said that Simmons had rushed down 11 rows of the Main Stand in order to get as close as possible to the Frenchman to abuse him, though Simmons would later claim that he was merely leaving his seat to visit the toilet.

The language Simmons used is also open to interpretation. Rather comically, he claimed to police in a follow-up interview that he had used the words ‘Off, off, off. Go on, Cantona, have an early shower.’ A slightly different account was heard in court by a witness attending the game as a neutral, and who quoted Simmons as shouting, ‘You fucking cheating French cunt. Fuck off back to France, you motherfucker. French bastard. Wanker.’

It is worth noting that the court sided with the witness and that Simmons’s evidence was clearly unsound, to the extent that even Cantona’s prosecutor Jeffrey McCann fully agreed on that point. It later transpired that Simmons had a conviction for assault with intent to rob and was a British National Party and National Front sympathiser. There is also a theory that Simmons was not even a Crystal Palace supporter, but a Fulham fan who for some reason had chosen to attend the game. On that point, the truth will surely never be known.

Cantona had been subjected to a series of racist taunts and the strongest verbal abuse from someone intent on provoking a reaction. If Shaw was the star in Act 1 of The Temptation of Cantona, Simmons took over the role in Act 2.

Simmons would cause greater controversy having been found guilty of using threatening words and behaviour during the Cantona incident, earning him a £500 fine and a 12-month football banning order. When he appeared for sentencing, Simmons leapt over the bench and kicked and punched the counsel for the prosecution. It earned him a seven-day prison sentence for contempt of court. As he was led away, Simmons shouted a final parting message: ‘I am innocent. I swear on the Bible. You press. You are scum.’

Whatever was said, Cantona’s reaction was shocking. Pausing for a second to identify his target, the forward launched a flying kick at Simmons’s chest and connected emphatically. Falling awkwardly to the floor – as is inevitable when you have propelled yourself near horizontally in such a manner – Cantona then waded in with multiple punches as Simmons fought back. Around them, Palace supporters watched on in astonishment and fear.

Cantona’s teammate Paul Ince also got involved; scalded with hot tea thrown from someone in the crowd, he responded with punches of his own. It was Manchester United’s kit man Norman Davies, tasked with escorting Cantona to the tunnel, who eventually dragged the Frenchman away with the help of a steward. Schmeichel raced over to try to calm Cantona down. It is interesting to see the goalkeeper pointing at the Palace support in an accusatory manner even in the midst of what had just occurred.

Back at the scene of the fight, Manchester United players gathered near the home supporters to vent their displeasure at the abuse that they believed had been responsible for sparking the furore. In front of them, a row of stewards wearing hi-vis jackets provided a human barrier between fans and players. The entire incident lasted seven seconds. Its ramifications would last for years.

‘I just stood there transfixed,’ Pallister told the Manchester Evening News. ‘I was in total disbelief at what I’d seen. I just couldn’t believe it. I can remember seeing Norman Davies attempting to stop Eric beating the living daylights out of the fan. Thank goodness he managed to pull him away.’

Kitman Davies deserves great credit for his pacifying role. Having eventually frogmarched – weak pun unintended – Cantona down the touchline without further incident and got him into the safety and sanctity of the away dressing room, Davies’s job was not finished. He guarded the door from the inside, blocking a still irate Cantona from breaking out and continuing the altercation.

‘He was furious,’ Davies recalled. ‘He wanted to go back out again. I locked the door and told him, “If you want to go back out on the pitch, you’ll have to go over my body and break the door down.”’

Having finally relented, Cantona drank a cup of tea that Davies had made for him and went for a shower. United’s kitman had prevented a dire situation getting even further out of hand. He would thereafter be known as ‘Vaseline’ among the players, having seen Cantona slip out of his grasp to kick Simmons.

The first official reaction to the incident came from Chief Superintendent Terry Collins, who said that Cantona and Ince would be allowed to travel home but should expect to be called to police interview within the next 48 hours. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it in my life,’ Collins said. ‘There could have been a riot.’ On that point, it was hard to disagree.

That same evening, the Football Association issued its own statement: ‘The FA are appalled by the incident that took place by the side of the pitch at Selhurst Park tonight. Such an incident brings shame on those involved as well as, more importantly, on the game itself.

‘The FA is aware that the police are urgently considering what action they should take. We will as always cooperate in every way with them. And as far as the FA itself is concerned, charges of improper conduct and of bringing the game into disrepute will inevitably and swiftly follow tonight’s events. It is our responsibility to ensure that actions that damage the game are punished severely. The FA will live up to that responsibility.’

Ferguson’s reaction was altogether more interesting, not least because he had not seen the full extent of the incident from his vantage point and had been given mixed messages about what had taken place. A number of Manchester United players have recalled their surprise at Ferguson’s composure in the dressing room after the match, barely focusing on the incident but instead castigating his defenders for allowing Gareth Southgate to score a late equaliser. That gives some credence to the theory that United’s manager was not fully aware what had happened. It would have been a brave player to have spoken up to explain.

Ferguson’s initial anger was at Cantona’s stupidity in ignoring his half-time advice. ‘Not for the first time, his explosive temperament had embarrassed him and the club and tarnished his brilliance as a footballer,’ Ferguson wrote in Managing My Life. ‘This was his fifth dismissal in United colours and, in spite of all the provocation directed at him, it was a lamentable act of folly.’ That description became mistakenly attributed to the kung-fu kick at Simmons; it was actually in reference to the kick on Shaw.

Initially – and, his critics might say, typically – Ferguson blamed the referee. Alan Wilkie had also not seen the incident, although he was informed post-match of the precise details and stayed late at the ground to assist with the initial inquiries. He was met by a furious Ferguson, who told him, ‘It’s all your fucking fault. If you’d done your fucking job this wouldn’t have happened.’ It is unclear whether Ferguson was again referring to the red card or the post-sending-off events, but a police officer eventually had to force Ferguson out of Wilkie’s dressing room.

Having flown back to Manchester late that night, Ferguson rejected the advice of his son Jason to watch what he described as a ‘karate kick’ and instead endured some broken sleep. By 4 am he had risen, and by 5 am was ready to watch the footage. ‘Pretty appalling,’ is the only description that Ferguson offered.

Ferguson’s anger with Cantona reflected his disappointment that he had been so let down by a player in whom he had bestowed considerable faith. Manchester United had been widely derided for taking a chance on the enfant terrible. If Cantona’s performances in his first two seasons had proved Ferguson right, here was the sting in the tail.

Manchester United’s manager couldn’t say that there had been no warning signs. When playing for Auxerre, Cantona punched teammate Bruno Martini after a disagreement. During a charity match in Sedan for victims of an earthquake in Armenia, he kicked the ball into the crowd, threw his shirt at the referee and stormed off the pitch. In September 1988 he called France national team coach Henri Michel ‘a bag of shit’ in a post-match interview and was banned from playing for the national team until after Michel’s eventual sacking.

In 1991, when playing for Nîmes against St-Étienne, Cantona threw the ball at the referee and was given a four-game ban. When hauled in front of a disciplinary commission to explain himself and be told that other clubs had complained about his behaviour, Cantona approached the face of each member of the panel and called each of them an idiot in turn. The ban was promptly extended to two months.

That ban led to Cantona retiring from football at the age of 25, but he was talked round by Michel Platini, who believed that such a talent was too big a loss for the national team. It was Platini who persuaded Cantona to consider a move to England, having burned his bridges in Ligue 1.

If Ferguson’s aim was to smooth the roughest edges of Cantona’s ill-discipline, he barely managed it. Six months after joining United, Cantona was found guilty of misconduct and fined £1,000 after Leeds United fans accused him of spitting at them. Cantona claimed that he had spat at a wall. The disciplinary commission certainly agreed that there were mitigating circumstances, Cantona having been subjected to constant abuse from Leeds supporters.

In 1993/94, his first full season at Old Trafford, Cantona was sent off twice in the space of four days against Arsenal and Swindon. The first dismissal was for a stamp on the chest of John Moncur, the second for two yellow cards. The accusation against Ferguson’s United was that they were becoming undermined by their own indiscipline. For better and worse, the players were following Cantona’s lead.

Matters deteriorated even further in September 1994 in Galatasaray’s Ali Sami Yen Stadium, a daunting atmosphere for any player. Cantona was again sent off, right on the full-time whistle, and was reportedly struck by a police officer’s baton as he headed down the tunnel. Incensed by the assault, Cantona attempted to force his way through stewards and officials to confront the police officer, and had to be dragged to the dressing room and guarded by teammates.

‘Pally [Pallister], Robbo [Bryan Robson] and Brucey [Steve Bruce] had to drag Eric in and hold him there,’ Gary Neville remembers in his autobiography. ‘The experienced lads were going to the shower two by two so that Eric was never left alone in the dressing room. They ended up walking him to the coach to stop him going back after the police.’

This suggests two things: that Cantona’s combustibility was hardly a secret to Manchester United’s coaches and players, and that his anger took a considerable time to dissipate.

The uncomfortable truth for Ferguson is that Cantona was an accident waiting to happen and that the incident at Selhurst Park – while initially shocking – was not at all surprising. Manchester United’s manager backed himself to curb such ‘over-enthusiasm’ but was not successful, even if he rightly considered that Cantona’s quality outweighed the pitfalls.

In an interview with the Observer in 2004, Cantona – perhaps unwittingly – alluded to the inevitability of such incidents and his own lack of control. ‘If I’d met that guy on another day, things may have happened differently even if he had said the same things. Life is weird like that. You’re on a tightrope every day.’

Further evidence arrives in another Cantona quote, this time on the subject of being challenged. ‘I want to be like a gambler in a casino who can feel that rush of adrenaline not just when he’s on a roll, but all of the time,’ he said. ‘He gambles because he needs that buzz, he wants to experience it every moment of his life. That’s the way I want to play.’

This is the definition of playing on the edge, with every extreme element of the psyche bubbling just beneath the surface. It is a style that is rarely admitted to by sportspeople, for whom the typical strategy to achieve excellence is to rely upon an inner calm that enables composure in the crunch moments.

Cantona was a team player and very rarely selfish in possession of the ball, and yet he says that penalties – football’s most individual moment – were his ultimate buzz because they offered him a few seconds during which all eyes were on him to perform. He was driven to achieve, not necessarily to help the team or for personal glory, but through an addiction to the feeling of displaying immense skill and entertaining spectators in doing so.

That might sound peculiar, but it’s actually a persuasive argument. Becoming a professional footballer and maintaining your fitness and level of performance is incredibly hard. Dragging yourself through such physical and mental exhaustion for neither money nor love but to satisfy an addiction makes some sense. After all, many retired players speak of their propensity to succumb to other addictions because of their need to recreate football’s adrenaline rush.

Cantona sat at the extreme end of that spectrum. Anything that stopped him playing or curtailed his enjoyment of the game became the enemy: referees with their red cards, defenders with their physical treatment, coaches with their stymied tactics, supporters with their abuse. All this explains his fury in Istanbul and south London.

Cantona’s desire to ‘feel that rush’ blended with an anarchistic edge to his personality that lay not in a mistrust of authority per se, but a need to enjoy freedom of expression. ‘Above all I need to be free,’ he writes in Cantona on Cantona. ‘I don’t like to feel constrained by rules or conventions. There’s a limit to how far this idea can go, and there’s a fine line between freedom and chaos. But to some extent I espouse the idea of anarchy.’

Rather than rules, Cantona preferred to administer justice according to an ethical code; one that his critics might argue lacked calibration. So when Simmons screamed xenophobic abuse in his face, Cantona’s temper and determination to dispense moral retribution led to a spectacular assault. The accusation from Simmons that Cantona was a ‘lunatic’ was spectacularly misplaced.

Amid the myriad explanations for the attack, one thing remains certain: Cantona stayed true to his principles and never regretted his actions. ‘I’ve said before I should have kicked him harder but maybe tomorrow I’ll say something else,’ he said in 2017. ‘I cannot regret it. It was a great feeling. I learned from it – I think he [Simmons] learned too.’

Had you spoken to Ferguson on the morning of 26 January 1995, he might have had a slightly different view. Manchester United had travelled south to Selhurst Park with the chance to go top of the Premier League. They travelled back north without a victory, with potential criminal charges hanging over two key players and with their most talented attacker once again thrust into disciplinary controversy. Lock the doors and windows and batten down the hatches at Old Trafford. A storm was brewing.

DAY 3 (#ulink_ee5fc5df-b5e1-5d33-8232-1933975f8c52)

‘Good on you Eric’

Ferguson had always been predisposed to defend Cantona, because of both his extraordinary talent and his tempestuous reputation. Manchester United’s manager was aware when signing Cantona that he would require a particular strand of his man-management, but he rejected the notion that the Frenchman’s disciplinary problems before arriving at Old Trafford should define how he was treated.

‘He had been a bit of a wayward character at his other clubs and had gained a reputation for being unruly and difficult,’ Ferguson wrote in Leading. ‘It was almost as if he was considered some sort of demon. That made no sense to me. When you are dealing with individuals with unusual talent, it makes sense to treat them differently. I just made it a point to ignore what had happened in the past and treat Eric as a new man when he joined United.’

Ferguson makes that sound simple, but the strategy went against the grain. Ignoring Cantona’s rap sheet inevitably became a defence of it. During the period immediately after Cantona moved to United, the media regularly questioned Ferguson’s decision to take on a player with such an explosive personality. After finishing only four points behind champions Leeds United in 1991/92 – up from sixth the previous season – United only needed a slight improvement to win the league. The accusation was that Cantona risked rocking the boat so much that it might sink.

In 1994 Sky Sports produced a video montage of Cantona’s fouls and aggression set to music. It made Ferguson furious at the alleged victimisation of his player, although the reality is that United’s manager needed no excuse to rail against the conduct of journalists who he felt regularly threw rocks around a large glass house.

Ferguson did not just give Cantona a clean slate; he treated him differently to the other players in United’s squad. Ferguson usually maintained an air of authority on the training ground or on matchday, but would go out of his way to talk to Cantona one-on-one every day. Recognising that the Frenchman was a sensitive personality, he would talk to him about different aspects of football relating to United and beyond in order to ensure the player’s well-being.

One interesting theory – proposed by Ferguson himself – is that the Manchester United manager saw plenty of his own personality in Cantona, thus giving him added personal motivation to get the best out of him. Both had reputations for explosive anger and both saw themselves as outsiders, non-Englishmen attempting to lead an English sporting institution.

The true explanation might well have been more simple than that. Ferguson, renowned as a pragmatist, understood that having bought a unique talent and personality, there was very little to be gained in trying to mould Cantona and risk diluting him. Do that, and Manchester United might as well not have bothered at all.

If Cantona’s special treatment could easily have caused resentment within United’s dressing room, Ferguson’s dismissal of that suggestion is gloriously pithy: ‘I did things for Eric … that I did not do for them, but I don’t think this was resented, because the players understood the exceptional talents had qualities they did not possess.’

Whether or not Ferguson’s assessment was accurate is open to interpretation. In his autobiography, Mark Hughes writes that ‘the manager had to stretch a few principles to accommodate a Frenchman who is his own man and obviously has had his problems conforming’, and that while ‘Ferguson didn’t exactly rewrite the rulebook he treated him differently’. But the overwhelming sense is that the Manchester United players understood Ferguson’s reasoning. That is a tribute to both the manager’s man-management and their own maturity.

It was Ferguson’s special treatment of Cantona that made him so angry about the Frenchman’s actions at Selhurst Park. Having done so much to accommodate him, Ferguson expected to at least be met halfway. Cantona had made his manager look foolish, and Ferguson certainly knew that this was not an incident that could simply be brushed away through clever manipulation of the media.

Ferguson’s initial reaction was that Manchester United should sack Cantona. He describes the atmosphere around the club’s bigwigs as ‘filled with an overriding sense of doom’, but also meeting Sir Roland Smith and Maurice Watkins in the Edge hotel in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, the evening after the night before. Smith and Watkins were the chairmen of the club and plc. United’s share price had dropped by over 3 per cent in 24 hours.

Smith agreed with Ferguson that Cantona should be dismissed immediately, not least because neither could envisage a situation in which it was palatable for the Frenchman to play for the club again. In A Year in the Life, Ferguson’s diary of that season, the manager detailed his frustration at Cantona’s conduct:

I have supported Eric solidly through thick and thin, but I felt that this time the good name of Manchester United demanded strong action. The club is bigger than any individual. I related that to the board and they agreed.

Ferguson had the support of his wife Cathy, forever the manager’s rock, who assisted Ferguson’s decision-making far more than supporters might realise. She agreed with her husband that Cantona might have to leave or risk Ferguson being seen to prioritise on-pitch success above moral decency.

Ferguson’s worries were twofold. He believed that sticking by Cantona through this incident would arm United’s critics with the valid argument that a sporting institution had ceded to the temper of one majestically talented player. But he also foresaw the incident being repeated, given the media storm that had raged in the hours since the assault on Simmons. Provocation would only get worse. This was Ferguson admitting defeat in his attempt to control Cantona.

Ferguson would later recall a phone conversation with Sir Richard Greenbury – a friend and Manchester United supporter who was the chief executive and chairman of Marks & Spencer – in which Greenbury insisted that Cantona should stay. But it was Watkins who effectively guaranteed Cantona’s United future. He detailed the legal difficulties in sacking the player, and pointed out Cantona’s financial and sporting assets. On these points, neither Ferguson nor Smith needed convincing.

Eventually Ferguson, Smith and Watkins decided on a disaster-recovery plan. They would suspend Cantona until the end of the season and fine him two weeks’ wages, the maximum available to them. They communicated the punishment to both Cantona – who acquiesced – and Gordon Taylor, the chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association.

By lunchtime on the following day – Friday 27 January – Watkins released a statement detailing the ban: ‘In reaching this decision, which the player fully accepts, Manchester United has had regard to its responsibilities both to the club itself and the game as a whole.’

The statement left open the possibility of Cantona continuing to play reserve team football, but that was quickly rejected by Taylor. ‘I don’t think there’s any real prospect that he’ll be playing for Manchester United reserves, A team or whatever, between now and the date of his commission hearing,’ the PFA chief said. The Football Association quickly applied to FIFA for the ban to apply globally, and got their wish.

The speed with which Manchester United announced Cantona’s punishment was deliberately designed to curtail any further investigation by the Football Association. Having been charged by the FA and subjected to a criminal investigation, United could not hope that the storm in which Cantona had been swept up would pass quickly. But by taking him immediately out of the spotlight with his suspension, the club did at least hope to limit the damage.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/daniel-storey/250-days/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Daniel Storey

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Хобби, увлечения

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1514.17 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An incredibly entertaining and perceptive look at the most controversial moment in Premier League history.25th January 1995 A cold winter’s evening. Manchester United away against Crystal Palace at a packed-out Selhurst Park. Eric Cantona, United′s mercurial talisman, has been man-marked closely all game by Richard Shaw and become increasingly frustrated. In the 48th minute, Cantona’s temper boils over and he kicks out at Shaw. The ref shows him a red card. On his way off the pitch, a Palace fan rushes towards the hoardings to hurl abuse. The Frenchman loses it. He launches into the crowd, aiming a kung-fu kick at the fan’s chest. He is forcibly restrained and then taken off down the tunnel. The football world is stunned. Nothing like this has ever happened before.What followed has entered football folklore: the media furore, the seagulls following the trawler, and the longest domestic ban ever handed to a player; it would end up lasting 250 days. As Manchester United’s campaign stuttered towards a trophy-less conclusion, surrendering the league on the last day of the season and losing the FA Cup final, Cantona withdrew from the public eye. But, behind closed doors, Ferguson was planning the most remarkable of fresh starts for his star player and for a new-look United.250 Days tells the story in brilliant detail of one of the most turbulent times in United’s recent history. Showing Cantona in a new light, and the genius of Ferguson’s man management and vision in close relief, it is an incredibly entertaining and insightful look at the most controversial episode of the Premier League era.