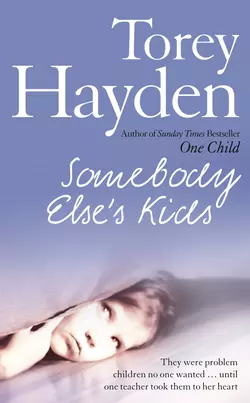

Somebody Else’s Kids

Torey Hayden

From the author of Sunday Times bestsellers One Child and Ghost Girl comes a heartbreaking story of one teacher's determination to turn a chaotic group of damaged children into a family.They were all just "somebody else's kids" – four problem children placed in Torey Hayden's class because nobody knew what else to do with them. They were a motley group of kids in great pain: a small boy who echoed other people's words and repeated weather forecast; a beautiful seven-year-old girl brain damaged by savage parental beatings; an angry ten-year-old who had watched his stepmother murder his father; a shy twelve-year-old who had been cast out of Catholic school when she became pregnant. But they shared one thing in common: a remarkable teacher who would never stop caring – and who would share with them the love and understanding they had never known to help them become a family.

Torey Hayden

Somebody Else’s Kids

Dedication (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

This book is for Adam, Jack and Lucio, but especially for Cliffie, whom I could not help, and whom I have lost to a lifetime of walls without windows. A book is such an impotent gesture, but, Cliffie, I have not forgotten you. And perhaps someone else, some other place, some other day, will know what I do not know.

Contents

Cover (#uc18460d2-a053-579b-b066-b55386f56df7)

Title Page (#u0bd4f894-ed2c-5ba2-95bd-0940e5eae809)

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Epilogue

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Torey Hayden (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

It was the class that created itself.

There is some old law of physics that speaks of Nature abhorring a vacuum. Nature must have been at work that fall. There must have been a vacuum we had not noticed because all at once there was a class where no class was ever planned. It did not happen suddenly, as the filling of some vacuums does, but rather slowly, as Nature does all her greatest things.

When the school year began in August I was working as a resource teacher. The slowest children from each of the elementary classes in the school would come to me in ones and twos and threes for half an hour or so a day. My job was to do the best I could to keep them up with the rest of their classes, primarily in reading or math, but sometimes in other areas as well. However, I was without a class of my own.

I had been with the school district for six years. Four of those years had been spent teaching in what educators termed a “self-contained classroom,” a class which took place entirely within one room; the children did not interact with other children in the school. I had taught severely emotionally disturbed children during this time. Then had come Public Law 94–142, known as the mainstreaming act. It was designed to normalize special education students by placing them in the least restrictive environment possible and minimizing their deficits with additional instruction, called resource help. There were to be no more closeted classrooms where the exceptional children would be left to sink or swim a safe distance from normal people. No more pigeonholes. No more garbage dumps. That beautiful, idealistic law. And my kids and me, caught in reality.

When the law passed, my self-contained room was closed. My eleven children were absorbed into the mainstream of education, as were forty other severely handicapped children in the district. Only one full-time special education class remained open, the program for the profoundly retarded, children who did not walk or talk or use the toilet. I was sent to work as a resource teacher – in a school across town from where my special education classroom had been. That had been two years before. I suppose I should have seen the vacuum forming. I suppose it should have been no surprise to see it fill.

I was unwrapping my lunch, a Big Mac from McDonald’s – a real treat for me because on my half-hour lunch break I could not get into my car and speed across town in time to get one as I had been able to do at the old school. Bethany, one of the school psychologists, had brought me this one. She understood my Big Mac addiction.

I was just easing the hamburger out of the Styrofoam container, mindful not to let the lettuce avalanche off, which it always did for me, trying for the millionth time to remember that idiotic jingle: Two-all-beef-patties-blah, blah, blah. My mind was not on teaching.

“Torey?”

I looked up. Birk Jones, the director of special education in the district, towered over me, an unlit pipe dangling from his lips. I had been so absorbed in the hamburger that I had not even heard him come into the lounge. “Oh, hi, Birk.”

“Do you have a moment?”

“Yeah, sure,” I said, although in truth I didn’t. There were only fifteen minutes left to gobble down the hamburger and french fries, drink the Dr Pepper and still get back to a whole stack of uncorrected work I had left in the classroom. The lettuce slipped off the Big Mac onto my fingers.

Bethany moved her chair over and Birk sat down between us. “I have a little problem I was hoping you might help me out with,” he said to me.

“Oh? What kind of problem?”

Birk took the pipe out of his mouth and peered into the bowl of it. “About seven years old.” He grinned at me. “Over in Marcy Cowen’s kindergarten. A little boy, I think he’s autistic, myself. You know. Does all sorts of spinning and twirling. Talks to himself. Stuff like your kids used to do. Marcy’s at the end of her rope with him. She had him part of last year too and even with a management aide in the room, he hasn’t changed a bit. We have to do something different with him.”

I chewed thoughtfully on my hamburger. “And what can I do to help you?”

“Well …” A long pause. Birk watched me eat with such intensity that I thought perhaps I ought to offer him some. “Well, I was thinking, Tor … well, perhaps we could bus him over here.”

“What do you mean?”

“And you could have him.”

“I could have him?” A french fry caught halfway down my throat. “I’m not equipped in my present situation to handle any autistic kids, Birk.”

He wrinkled his nose and leaned close in a confidential manner. “You could do it. Don’t you think?” A pause while he waited to see if I would reply or simply choke to death quietly on my french fry. “He only comes half days. Regular kindergarten schedule. And he’s rotting in Marcy’s class. I was thinking maybe you could work with him special. Like you did with those other kids you used to have.”

“But Birk? … I don’t have that kind of room anymore. I’m set up to teach academics. What about my resource children?”

Birk shrugged affably. “We’ll arrange something.”

The boy was to arrive every day at 12:40. I still had my other children coming in until two, but after that, he and I had only one another for the remaining hour and a half of the school day. In Birk’s mind it was no worse if the child destroyed my room for that period of time when I had to work with the resource students than if he tore up Marcy Cowen’s kindergarten. Because of my years in the self-contained room, I had that mysterious thing Birk called “experience.” Translated, it simply meant I did not have the option to get upset, that I should know better.

I cleared the room for this boy. I put all the breakables out of reach, placed all the games with small, swallowable pieces in a closet, moved desks and tables around to leave a running space where he and I could tackle one another on more intimate terms than I ever needed to do with the resource students. As I finished and stood back to assess my job, pleasure surged up. I had not found resource teaching particularly fulfilling. I missed the contained-classroom setting. I missed not having my own group of children. But by far the most, I missed the eerie joy I always felt working with the emotionally disturbed.

On Monday, the third week in September, I met Boothe Birney Franklin. His mother called him Boothe Birney to his face. His three-year-old sister could only manage Boo. That seemed good enough to me.

Boo was seven years old. He was a magic-looking child as so many of my children seemed to be. There was an illusory realness about his expression: the sort one sees in a dream. Of mixed parentage, he had skin the color of English tea with real cream in it. His hair was not quite black, a veritable mass of huge, loose curls. His eyes were green, mystery green, not clear but cloudy – a sea green, soft and ever changing. He looked like an illustration from a Tasha Tudor picture book come to life. But not a big child, this boy. Not for seven. I would have guessed him barely five.

His mother shoved him through the open door, spoke a few words to me and left. Boo now belonged to me.

“Good afternoon, Boo,” I said.

He stood motionless, just inside the door where his mother had left him.

I knelt to his level. “Boo, hello.”

He averted his face.

“Boo?” I touched his arm.

“Boo?” he echoed softly, still looking away from me.

“Hello, Boo. My name is Torey. I’m your new teacher. You’ll come to this room from now on. This will be your class.”

“This will be your class,” he repeated in my exact intonation.

“Come here, I will show you where to hang your sweater.”

“I will show you where to hang your sweater.” His voice was very soft, hardly more than a whisper, and oddly pitched. It was high with an undulating inflection, as a mother’s voice to an infant.

“Come with me.” I rose and held out a hand. He remained motionless. His face was still turned far to the left. At his side his fingers began to flutter against his legs. Then he started to beat the material of his pants with open palms. The muted sound they made was all the noise there was in the room.

Two other children were there, two fourth-grade boys with their reading workbooks. They both sat paralyzed in their chairs, watching. I had told them Boo was coming. In fact I had given them special work to do for Boo’s first day, so that they could work much of the thirty-minute session independently while Boo and I checked one another out. Yet the boys could not take their eyes from us. They watched with mouths slightly agape, bodies bent forward over their desks, brows furrowed in fascination.

Boo patted his hands against his trousers.

I did not want to rush him. We were in no hurry. I backed up and gave him room. “Will you take off your sweater?”

No movement, no sound other than his hands, beating frantically now. He still would not turn his face toward me; it remained averted far to the side.

“What’s wrong with him?” one fourth grader asked.

“We talked about it yesterday, Tim. Remember?” I replied, not turning around.

“Can’t you make him stop that?”

“He isn’t hurting anyone. Nothing’s wrong. Just do your work, please. All right?”

Behind me I heard Tim groan in compliance and riffle through his book. Boo stood absolutely rigid. Arms tight to sides, except, of course, for the hands. Legs stiff. Head screwed on sideways, or so it looked. Not a muscle moved beyond the fluttering.

Then with no warning Boo screamed. Not a little scream. A scream heard clear to next Christmas. “AHHHHHH! AHHH AHHHH! AWWWWR-RRRRKK!” He sounded like a rabbit strangling. Hands over eyes he fell writhing to the floor. Then up before I could get nearer. Around the room. “ARRRRRRRRR!” A human siren. Arms flew out from his sides and he flapped them wildly above his head like a frenzied native dancer. He fell again to the floor. Boo turned and twisted as if in agony. Hands over his face, he beat his head against the linoleum. All the while he screamed. “AAAAAAH-HHHHHHHHHH! EEEEE-EEEEEE-E-AHHHH-AWWWWWWWWK!”

“He’s having a fit! Oh my gosh, he’s having a fit! Quick, Torey, do something!” Tim was crying. He had leaped up on his chair, his own hands fluttering in panic. Brad, the other fourth grader, sat spellbound at his desk.

“He’s not having a fit, Tim,” I hollered over Boo’s screams as I tried to lift him from the floor. “He’s okay. Don’t worry.” But before I could say more, Boo broke my grasp. One frenetic whirl around the room. Over a chair, around a bookcase, across the wide middle area I had cleared. To the door. And out.

Chapter Two (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

“Boo? Boo?” I was in the hallway. “Boo?” I whispered loudly into the silence and felt like a misplaced ghost.

I had made it to the classroom door in time to see him career squawking around the far corner of the corridor, but by the time I had gotten down there Boo was gone. He had disappeared entirely and left me booing to myself.

I went into the primary wing of the building. Wherever he had gone, he had ceased to scream. The classrooms were empty, the children had gone out for recess. All was quiet. Eight rooms in all to check. I stuck my head first in one room and then in another. That miserable rushed feeling overcame me. I knew I had to capture Boo and get him back, check Tim’s and Brad’s work, calm them down a bit about this odd boy before they went back to their class, and finally prepare for Lori, my next resource student. And all that time I needed to be with Boo.

“Boo?” I looked in the third-grade rooms. In the second-grade rooms. “Boo, time to go back now. Are you here?” Through the first-grade rooms.

I opened the door to the kindergarten. There across the classroom under a table was Boo. He had a rug pulled over his head as he lay on the floor. Only his little green corduroy-covered rear stuck out. Had he known that this was a kindergarten room? Was he trying to get back to Marcy’s? Or was it no more than coincidence that put him here, head under a rug on the floor?

Talking all the while in low tones, I approached him cautiously. The kindergarten children were returning from recess. Curiosity was vivid on their faces. What was this strange teacher doing in their room under their table? What about this boy in the green corduroy pants?

“Boo?” I was saying softly, barely more than a whisper. “Time to go to our room now. The other children need this room.”

The kindergarteners watched us intently but would not come closer. I touched Boo gently, ran my hand along the outside of the rug, then inside along his body to accustom him to my touch. Carefully, carefully I pulled the rug from around his head and extracted him. Holding him in my arms, I slid from under the table. Boo was soundless now and rigid as a mannequin. His arms and legs were straight and stiff. I might as well have been carrying a cardboard figure of a boy. However, this time he did not avert his face. Rather, he stared through me as if I were not there, round eyed and unblinking, as a dead man stares.

A small freckle-faced boy ventured closer as I prepared to take Boo from the classroom. He gazed up with blue, searching eyes, his face puckered in that intense manner only young children seem to have. “What was he doing in our room?” he asked.

I smiled. “Looking at the things under your rug.”

Lori stood outside the door of my room when I returned carrying a stiff Boo in my arms. Tim and Brad had already gone and had closed the door and turned off the light when they left. Lori, workbook in hand, looked uncertain about entering the darkened room.

“I didn’t know where you were!” she said emphatically. Then she noticed Boo. “Is that the little kid you told me about? Is he going to be in with me?”

“Yes. This is Boo.” I opened the door clumsily and turned on the light. I set Boo down. Again he remained motionless, while Lori and I went to the worktable at the far side of the room. When it became apparent Boo was not going to budge, I went back to the doorway, picked him up and transported him over to us. He stood between the table and the wall, still rigid as death. No life glimmered in those cloudy eyes.

“Hello, little boy,” Lori said and sat down in a chair near him. She leaned forward, an elbow on the table, eyes bright with interest. “What’s your name? My name’s Lori. Lori Ann Sjokheim. I’m seven. How old are you?”

Boo took no notice of her.

“His name is Boo,” I said. “He’s also seven.”

“That’s a funny name. Boo. But you know what? I know a kid with a funnier name than that. Her name’s Maggie Smellie. I think that’s funny.”

When Boo still did not respond, Lori’s forehead wrinkled. “You’re not mad, are you, ’cause I said that? It’s okay if you got a funny name. I wouldn’t tease you or nothing. I don’t tease Maggie Smellie either.” Lori paused, studied him. “You’re kind of small for seven, huh? I think I’m taller than you. Maybe. But I’m kind of small too. That’s ’cause I’m a twin and sometimes twins are small. Are you a twin too?”

Lori. What a kid Lori was. I could sit and listen to her all day long. In all my years of teaching, Lori was unique. In appearance she was for me an archetypal child, looking the way children in my fantasies always looked. She had long, long hair, almost to her waist. Parted on one side and caught up in a metal clip, it was thick and straight and glossy brown, the exact color of my grandmother’s mahogany sideboard. Her mouth was wide and supple and always quick to smile.

Lori had come to me through evil circumstances. She and her twin sister had been adopted when they were five. The other twin had no school problems whatsoever. But from the very beginning Lori could not manage. She was hyperactive. She did not learn. She could not even copy things written for her. The shattering realization came during her second year in kindergarten, a grade-retention born out of frustration for this child who could not cope.

Lori had been a severely abused child in her natural home. One beating had fractured her skull and pushed a bone fragment into her brain. X-rays revealed lesions. Although the fragment had been removed, the lesions remained. How severe the lasting effects of the brain damage would be no one knew. One result had been epilepsy. Another had been apparent interference with the area of the brain that processes written symbols. She also had many of the problems commonly associated with more minimal types of damage, such as difficulty in concentration, an inability to sit still and distractibility. The bittersweet issue in my mind, however, was the fact that Lori came away from the injury as intact as she did. She lost very little, if any, of her intelligence or her perception or her understanding, and she was a bright child. Nor did she look damaged: For all intents and purposes, Lori was normal. Because of this, I noticed that people, myself included, tended to forget she was not. And sometimes we became angry with her for things over which she had no control.

The prognosis for her recovery was guarded. Brain cells, unlike other cells in the body, do not regenerate. The only hope the doctors had given was that in time her brain might learn other pathways around the injured area and tasks such as reading and writing would become more feasible things for her to accomplish. In the meantime Lori struggled on as best she could.

But there was no kid quite like Lori. Her brain did not always function well, yet there was nothing wrong with Lori’s heart. She was full of an innate belief in the goodness of people. Despite her own experiences, evil did not exist for Lori. She embraced all of us, good and bad alike, with a sort of droll acceptance. And she cared. The welfare of all the world mattered to her. I found it both her most endearing and annoying trait. Nothing was safe from her: she cared about how you felt, what you thought, what your dreams were. She involved herself so intimately in a world so hard on those who care that I often caught my breath with fear for her. Yet Lori remained undaunted. Her love was a little raw at seven, and not yet cloaked by social graces, but the point was, she cared.

Boo was of great concern to Lori.

“Doesn’t he talk?” she asked me in a stage whisper after all her attempts at conversation had been ignored.

I shook my head. “Not too well. That’s one of the things that Boo came here to learn.”

“Ohhh, poor Boo.” She stood up and reached out to pat his arm. “Don’t worry, you’ll learn. I don’t learn so good myself so I know how you feel. But don’t worry. You’re probably a nice boy anyways.”

Boo’s fingers fluttered and the vacant eyes showed just the smallest signs of life. A quick flicker to Lori’s face, then he turned and faced the wall.

I decided to work with Lori and leave Boo to stand. There was no need to hurry. “I’ll be right here, Boo,” I said. He stood motionless, staring at the wall. I turned my chair around to the table.

Lori flipped open her workbook. “It’s dumb old spelling again today. I don’t know.” She scratched her head thoughtfully. “Me and that teacher, we just aren’t doing so good on this. She thinks you oughta teach me better.”

I grinned and pulled the book over to view it. “Did she tell you that?”

“No. But I can tell she thinks it.”

Boo began to move. Hesitantly at first. A step. Two steps. Mincingly, like a geisha girl. Another step. I watched him out of the corner of one eye as I leaned over Lori’s spelling. Boo walked as if someone had starched his underwear. His head never turned; his arms remained tight against his sides. The muscles in his neck stood out. Every once in a while his hands would flap. Was all this tension just to keep control? What was he trying so desperately to hold in?

“Look at him,” Lori whispered. She smiled up at me. “He’s getting himself to home.”

I nodded.

“He’s a little weird, Torey, but that’s okay, isn’t it?” she said. “I act a little weird myself sometimes. People do, you know.”

“Yes, I know. Now concentrate on your spelling, please.”

Boo explored the environs of the classroom. It was a large room, square and sunny from a west wall of windows. The teacher’s desk was shoved into one corner, a repository for all kinds of things I did not know what to do with. The worktable stretched along below the windows where I could have the most light on my work. The few student desks in the room were back against one wall. Another wall housed my coat closet, the sink, the cupboards and two huge storage cabinets. Low bookshelves came out into the room to partition off a reading corner and the animals: Sam, the hermit crab; two green finches in a huge home-made cage; and Benny the boa constrictor, who had taught school as long as I had.

Boo inched his way around the room until he came upon the animals. He stopped before the birds. At first he did nothing. Then very slowly he raised one hand to the cage. Flutter, flutter, flutter went his fingers. He began to rock back and forth on his heels. “Hrooop!” he said in a small, high-pitched voice. He said it so quietly the first time that I thought it was the finches. “Hrooooop! Hrrrroo-ooop!” Both hands were now at ear level and flapping at the birds.

“Ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah,” he began, still softly. “Ee-ee-ee-ee. Ah-ee. Hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo. Hee-hee-hee-hee-hee.” He sounded like a resident of the ape house at the zoo.

Lori looked up from her work, first at Boo and then at me. She had a very expressive glance. Then with a shake of her head she went back to work.

Boo was smiling in an inward translucent sort of way. He turned around. The stiffness in his body melted away. “Heeheeheeheeheeheeheehee!” he said gaily. His eyes focused right on my face.

“Those are our birds, Boo.”

“Heeheeheeheeheeheehee! Haahaahaahaahaahaa! Ah-ah-ah-ah!” Great excitement. Boo was jumping up and down in front of the cage. His hands waved gleefully. Every few moments he would turn to look at Lori and me. I smiled back.

Abruptly Boo took off at a run around the classroom. High-pitched squeally laughter lanced the schoolroom quiet. His arms flopped widely like a small child playing at being an airplane, but there was a graceful consistency to the motion that made it unlike any game.

“Torey!” Lori leaped up from her chair. “Look at him! He’s taking off all his clothes!”

Sure enough Boo was. A shoe. A sock. A shirt. They all fell behind him as he ran. He was a clothes Houdini. His green corduroy pants came down and off with hardly a break in his rhythm. Boo darted back and forth, laughing deliriously, clothing dropping in his wake. Lori watched with horrified fascination. At one point she put her hands over her eyes but I saw her peeking through her fingers. A goofy grin was glued to her face. Boo made quite a sight.

I did not want to chase him. Whatever little bit of lunacy this was, I did not want to be a party to it. My greatest concern was the door. Within minutes Boo had completely stripped and now capered around in naked glee. I had not enjoyed chasing him the first time when he had been fully clothed. I could just imagine doing it now. This was a nice, middle-class, sedate and slightly boring elementary school without any classes of crazy kids in it. Dan Marshall, the principal, swell guy that he was, would have an apoplectic fit if some kid streaked down one of his corridors. I would hate to be the cause of that.

Boo laughed. He laughed and danced from one side of the room to the other while I guarded the door. I longed for a latch on that door. That had been one of the small things my classrooms had always had. Locks, like all other things, are neither good nor bad in themselves. There are times for them. And this was one. It would have been better if I could simply have latched the door and gone back to my work. As it was now. Boo had me playing warden, trapped into participating in his game. It gave him no end of pleasure.

For almost fifteen minutes the delirium went on. He would stop occasionally, usually not far from me, and face me, his little bare body defiant. I tried to assess what I could see in those sea-green eyes. I could see something but I did not know what it was.

Then during one of his pauses he lifted a hand up before his face and began to twiddle his fingers in front of his eyes. A shade went down; something closed. Like the transparent membrane over a reptile’s eye, something pulled across him and he went shut again. The small body stiffened, the arms came close to his sides, protectively. No life flickered in his eyes.

Boo stood a moment, once more a cardboard figure. Then a wild flap of his arms and he minced off across the room and dived under a piece of carpet in the reading center. Wiggling, he slipped nearly entirely under until all that was visible was a lumpy carpet and two bare feet.

Lori gave me a defeated look as I returned to the worktable. “It’s gonna take a lot of work to fix him. Tor. He’s pretty weird. Boy, and I mean not just a little weird either.”

“He has his problems.”

“Yeah. He don’t got no clothes on for one thing.”

“Well, that’s okay for now. We’ll take care of that later on.”

“It’s not okay, Torey. I don’t think you’re supposed to be naked in school. My daddy, I think he told me that once.”

“Some things are different from others. Lor.”

“It isn’t right. I know. You can see his thing. Girls aren’t supposed to look at those. It means you’re nasty. But I could hardly help it, could I? And my dad would spank me if he knew I was doing that.”

I smiled at her. “You mean his penis?”

Lori nodded. She had to suck her lips between her teeth to keep from smiling too.

“I have a feeling you didn’t mind it too much.”

“Well, it was pretty interesting.”

We made it through the first day. Boo and I. Boo spent the entire hour and a half we had alone under the carpet. I let him remain there. When 3:15 approached I pulled him out and dressed him. Boo lay perfectly inert, his limbs slightly stiff but still compliant, his head back so that he was looking above him. I talked to him as I put back all the clothing he had so skillfully removed. I told him about the room, about the birds and the snake and the crab, about what he and I would do together, about other children he would meet, about Tim and Brad and Lori. About anything that came to mind. I watched his eyes. Nothing. There was nothing there. A body without a soul in it.

He began talking while I was, but when I stopped, he stopped. He still stared above him, although there was no focus to the gaze.

“What did you say, Boo?”

No response.

“Did you want to talk about something?”

Still looking blankly into space. “The high today will be about 65, the low tonight in the middle forties. In the mountain valleys there is a chance of frost. The high at the airport yesterday was 56. In Falls City it was 61.”

“Boo? Boo?” I softly touched his face. Loose black curls flopped back onto the carpet where he lay. The picture-book beauty lay over his features like a separate entity. His fingers waggled against the rug. I was touching him, buttoning his shirt, moving slowly but certainly up his chest. I might as well have been dressing a doll. All the while he continued talking, parroting back the morning weather report exactly, word for word. Delayed echolalia, if one wanted the technical term for it. If that mattered.

“Chance of precipitation in the Greenwood area, 20 percent today, 10 percent tonight and then rising to 50 percent by morning. It looks like it is going to be a beautiful autumn day here in the Midland Empire. And now for Ron Neilsen with the sports. Stay tuned. Don’t go away.”

Don’t worry. I won’t.

Chapter Three (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

We were piloting a reading series program in the primary grades that year. For me it was not a new program. The school I had previously taught in had also piloted the program. I got to live through the disaster twice.

The program itself was aesthetically outstanding. The publishers had obviously engaged true artistic talent to do the layouts and illustrations. Many of the stories were of literary quality. They were fun stories to read.

Unless, of course, you could not read.

It was a reading series designed for adults, for the adults who bought it, for the adults who had to read it, for the adults who had forgotten what it was like to be six and not know how to read. This series was a response to the community agitators who as forty-year-olds were not fascinated by the controlled vocabulary of a basal reader. They had demanded something more and now they had gotten it. As children’s books for adults, those in the series were peerless. In fact, the first time I had encountered the books, I had covertly dragged home every single reader at one time or another because I wanted to read them. Of course, I was twenty-six. We bought the books, the children did not, and in this case we bought the books for ourselves.

For the kids it was all a different matter. Or at least for my kids. I had always taught beginners or failures. For these two groups the reading program was an unmitigated disaster.

The major difficulty was that, in order to appeal to adults from the first pre-primer on, the series had dispensed with the usual small words, short sentences and controlled vocabulary. Even the pictures accompanying the text, though artistic, were rarely illustrative of the story at hand. The first sentence in the very first book intended for nonreading six-year-olds had eight words including one with three syllables. For some of the children this was all right. They managed the first sentence and all the others after it. For the majority of children, including mine, well … in the three years I had used the series, I had memorized the three pre-primers because never in all that time did any of my children advance to another book. Normally, the first three pre-primers were mastered in the first grade, before Christmas.

I was not the only person having problems. In the first year of piloting, word soon got around in the teachers’ lounge: None of the first- or second-grade teachers was having much success. Traditionally, publishers of reading series send a chart outlining the approximate place a teacher and her class should be at any given time in the term. We all gauged our reading programs around that chart so that we could have our children properly prepared for the next grade by the end of school. This publisher’s chart hung in the lounge that first year, and the five of us, two first-grade teachers, two second-grade teachers, and I with my primary special education class, would moan to see ourselves slip further and further behind where the publisher predicted we should be. No one was going to get through the program on time.

After a few months of struggling we became so incensed over this impossible series that we demanded some sort of explanation from the school district for this insanity. The outcome of the protest had been the arrival from the publishing company of a sales representative to answer our questions. When I brought up the fact that less than half of all the children in the program were functioning where the chart said they should be, I expected I had set myself up to be told my colleagues and I just were not good teachers. But no. The salesman was delighted. He smiled and reassured us that we were doing very well indeed. The truth was, he said, only 15 percent of all first graders were expected to complete the entire first-grade program during the first grade. The other 85 percent were not.

I was horrified beyond reply. We were using a program that by its very construction set children up to fail. All except the very brightest were destined to be “slow readers.” Many, many teachers not hearing this man’s words were going to assume that the chart was correct and put their children through an entire year’s program under the mistaken belief that all the first-grade material was meant to be done in the first grade, none in second. That was not too extravagant an assumption, in my opinion. Worst of all, however, was that as the years went on, perfectly ordinary children who were learning and developing at normal rates would fall further and further behind, so that by fifth or sixth grade they could conceivably be considered remedial readers because they were two or more books behind their grade placement, when in fact they were right where the publisher expected them to be. And of course nothing could ever be said to these children who were reading fourth-grade books in sixth that would convince them that they were anything other than stupid. It was nothing more than statistics to the publishing company. For the kids it was life. That was such a bitterly high price to pay for an aesthetically pleasing book.

Lori was one of the reading series’ unwilling victims. Already a handicapped student who undoubtedly would always have trouble with symbolic language, Lori was trapped with an impossible set of books and a teacher who despised both the books and special students.

Edna Thorsen, Lori’s teacher, was an older woman with many, many years of experience behind her. Due for retirement the next year, Edna had been in the field since before I was born. In many areas of teaching Edna was superb. Unfortunately, special children was not one of them. She firmly believed that no exceptional or handicapped child should be in a regular classroom, with perhaps the exception of the gifted, and even of that she was unsure. Not only did these children put an unfair burden on the teacher, she maintained, but they disallowed a good education for the rest of the class because of the teacher time they absorbed. Besides, Edna believed, six-year-olds were just too young to be exposed to the rawness of life that the exceptional children represented. There was plenty of time when they were older to learn about blindness and retardation and mental illness.

Edna kept to many of the more traditional methods of teaching. Her class sat in rows, always stood when addressing her, moved in lines and did not speak until spoken to. They also progressed through the reading program exactly according to the chart sent out by the publishing company. If in the second week of November the children were to be, according to the charts, up to Book #2, page 14, all three of Edna’s little reading groups were within a few pages one way or the other of Book #2, page 14, the second week in November. She had no concept of the notion that only 15 percent of the children were actually expected to be there and all the rest behind. Her sole responsibility, she said, was to see that all twenty-seven children in her room had gone through the three pre-primers, the primer and the first-grade reader by that last day of school in June and were ready for second grade. That all her children could not read those books had no bearing in Edna’s mind on anything. Her job was to present the material and she did. It was theirs to learn it. That some did not was their fault, not hers.

Lori was not doing well. The hoped-for maturation in her brain had not yet occurred. In addition to her inability to pick up written symbols, she continued to display other common behaviors of brain-damaged children such as hyperactivity and a shortened attention span. Although Lori had not been on my original roster of resource students when school convened, she appeared at my door during the first week with Edna close behind. We had here what Edna called a “slowie”; Lori was so dense, Edna told me, you couldn’t get letters through her head with a gun.

So for a half hour every afternoon, Lori and I tried to conquer the written alphabet. I had to admit we were not doing stunningly. In the three weeks since we had started, Lori could not even recognize the letters in her first name. She could write L-O-R-I without prompting now; we had accomplished that much. Sort of. It came out in slow, meticulously made letters. Sometimes the O and the R were reversed or something was upside down or occasionally she would start on the right and print the whole works completely backwards. For the most part, though, I could trust her to come close. I had scrapped the pre-reading workbook from the reading series because with two years of kindergarten she had been through it three times and still did not know it. Instead I started with the letters of her name and hoped their relevancy would help.

Her difficulty lay solely with symbolic language: letters, numbers, anything written that represented something, other than a concrete picture. She had long since memorized all the letters of the alphabet orally and she knew their sounds. But she just could not match that knowledge to print.

Teaching her was frustrating. Edna certainly was right on that account. Three weeks and I had already run through all my years of experience in teaching reading. I had tried everything I could think of to teach Lori those letters. I used things I believed in, things I was skeptical about, things I already knew were a lot of nonsense. At that point I wasn’t being picky about philosophies. I just wanted her to learn.

We began with just one letter, the L. I made flash cards to drill her, had her cut out sandpaper versions to give her the tactile sensation of the letter, made her trace it half a million times in a pan of salt to feel it, drew the letter on her palm, her arm, her back. Together we made a gigantic L on the floor, taped tiny construction paper L’s all over it and then hopped around it, walked over it, crawled on it, all the time yelling L-L-L-L-L-L-L-L! until the hallway outside the classroom rang with our voices. Then I introduced O and we went through the same gyrations. Three long weeks and still we were only on L and O.

Most of our days went like this:

“Okay, what letter is this?” I hold up a flash card with an O on it.

“M!” Lori shouts gleefully, as if she knows she is correct.

“See the shape? Around and around. Which letter goes around, Lor?” I demonstrate with my finger on the card.

“Oh, I remember now. Q.”

“Whoops. Remember we’re just working with L and O, Lor. No Q’s.”

“Oh, yeah.” She hits her head with one hand. “Dumb me, I forgot. Let’s see now. Hmmmm. Hmmmm. A six? No, no, don’t count that; that’s wrong. Lemme see now. Uh … uh … A?”

I lean across the table. “Look at it. See, it’s round. Which letter is round like your mouth when you say it? Like this?” I make my mouth O-shaped.

“Seven?”

“Seven is a number. I’m not looking for a number. I’m looking for either an O,” and here I make my mouth very obvious, “or an L. Which one makes your mouth look like this?” I push out my lips. “And that’s just about the only letter your lips can say when they’re like that. What letter is it?”

Lori sticks her lips out like mine and we are leaning so intently toward one another that we look like lovers straining to bridge the width of the table. Her lips form a perfect O and she gargles out “Lllllllll.”

I go “Ohhhhhhh” in a whisper, my lips still stuck out like a fish’s.

“O!” Lori finally shouts. “That’s an O!”

“Hey, yeah! There you go, girl. Look at that, you got it.” Then I pick up the next card, another O but written in red Magic Marker instead of blue like the last. “What letter is this?”

“Eight?”

So went lesson after lesson after lesson. Lori was not stupid. She had a validated IQ in the nearly superior range. Yet in no way could she make sense of those letters. They just must have looked different to her than to the rest of us. Only her buoyant, irrepressible spirit kept us going. Never once did I see her give up. She would tire or become frustrated but never would she completely resign herself to believing that L and O would not someday come straight.

The day after Boo arrived, Lori came to my room tearful. She was not crying but her eyes were full and her head down. Without acknowledging me, she hauled herself across the room to the table and tiredly threw the workbook down on it.

“What’s wrong, babe?” I asked.

Shrugging, she yanked a chair out and fell on it. With both fists she braced her cheeks.

“Shall we talk a bit before we start?”

She shook her head and swabbed roughly at the unfallen tears with a shirt sleeve.

Sitting down on the edge of the table next to her, I watched her. The dark hair had been caught back in two long braids. Red plaid ribbons were tied rakishly on the ends. Her skinny shoulders were pulled up protectively. Taking deep breaths, she struggled to keep her composure. A funny kid, she was. For all her spirit, for all her outspokenness, for all her insight into other people’s feelings, she was a remarkably closed person herself. I did not know her well even though she usually allowed me to believe I did.

We sat in silence a moment or two. I then rose to check on Boo. He was over by the animals again, watching the snake. Back and forth he rocked on his heels as he and Benny stared at one another. Benny was curled up on his tall hunk of driftwood under the heat lamp with his head hanging off the branch. It was a loony position for a snake, and if one did not know him, one could easily have mistaken him for dead. However, for those who did know, he was requesting a scratch along the neck. Boo just stared and rocked. Benny stared back. I returned to Lori and stood behind her. Gently, I massaged her shoulders.

“Hard day?”

She nodded.

Again I sat. Boo looked in our direction. Lori interested him. He watched with great, seeking eyes.

“I didn’t get no recess,” Lori mumbled.

“How come?”

“I didn’t do my workbook right.” She was tracing around one of the illustrations on the cover of the pre-primer on the table. Over and over it her finger slid.

“You usually do your workbooks in here with me. Lor. When we get time from our reading.”

“Mrs. Thorsen changed it. Everybody does their workbooks before recess now. If you do it fast you get to go out to recess early. Except me.” Lori looked up. “I have to do mine fast and right.”

“Oh, I see.”

The tears were there again, still unfallen but gleaming like captive stars. “I tried! I did. But it wasn’t right. I had to stay and work all recess and didn’t even get to go out at all. It was my turn at kickball captain even. And, see, I was going to choose Mary Ann Marks to be on my team. We were going to win ’cause she kicks better than anybody else in the whole room. In the whole first grade even. She said if I picked her then I could come over to her house after school and play with her Barbie dolls and we were gonna be best friends. But I didn’t even get to go out. Jerry Munsen got to be captain instead and Mary Ann Marks is going to go home with Becky Smith. And they’re going to be best friends. I didn’t even get a chance!” She caught an escaped tear. “It’s not fair. It was my turn to be captain and I had to stay in. Nobody else has to do their stuff all right first. Just me. And it isn’t fair.”

After school I went to talk to Edna Thorsen. For the most part Edna and I got along well. I did disagree with many of her methods and philosophies, but on the other hand she had a great deal more experience than I and had seen so many more children that I respected her overall knowledge.

“I’m taking your advice,” she told me as we walked into the teacher’s lounge.

“My advice?”

“Yes. Remember how I was complaining earlier about how I never could get the children to finish up their work on time?”

I nodded.

“And you suggested that I make the ones who did finish glad they did?” Edna was smiling. “I did that with the reading workbooks. I told the children they could go out to recess as soon as they finished their pages. And you sure taught this old dog a new trick. We get the work done in just fifteen minutes.”

“Do you check the work when they’re done?” I asked. “Before they go out?”

She made an obtuse gesture. “Nah. They do all right.”

“What about Lori Sjokheim?”

Edna rolled her eyeballs far back into her head. “Hers I have to check. Why, that Lori has no more intention of doing her work carefully than anything. The first few days I let her go with the other children, but then I got to looking at her workbook and you know what I found? Wrong. Every single answer wrong. She’ll take advantage of you every chance she gets.”

I had to look away. Look at the wall or the coffeepot or anything. Poor Lori who could not read, who could not write and who got all her answers wrong. “But I thought she was to bring in her workbooks to do with me,” I said.

“Oh, Torey.” Edna’s voice was heavy with great patience. “This is one thing you have yet to learn. You can’t mollycoddle the uncooperative ones, especially in the first grade – that’s when you have to show them who’s boss. Lori just needs disciplining. She’s a bright enough little girl. Don’t let her fool you in that regard. The only way Lori’s kind will shape up is if you set strict limits. It’s modern society. No one teaches their children self-restraint anymore.” Edna smiled.

“And with all due respect and credit to what you’re trying to do, Torey, I can’t see it myself. Giving her all that extra help when nobody else gets it. It’s a waste of time on some kids. I’ve been in the business a long time now, and believe me, you get so you can tell who’s going to make it and who isn’t. I just cannot understand spending all the extra time and money on these little slowies who’ll never amount to anything. So many other children would profit from it more.”

I rose to wrestle a can of Dr Pepper out of the machine. The right thing to do would have been to correct Edna, because to my way of thinking at least, she was dead wrong. The cowardly thing was to get up and go fight the pop machine. Yet that was what I did. I was, admittedly, a little afraid of Edna. She could speak her mind so easily; she seemed so confident about her beliefs. And she possessed so much of the only thing I had found valuable as an educator: experience. In the face of that, I was left uncertain and questioned my own perceptions. So I took the coward’s way out.

Unfortunately, the situation did not mend itself. The next day, too, Lori was kept in during recess and still she lugged her reading workbook in to me all full of errors. She was more resigned. No tears. The day after that was no different either. Or the day after that. If we did not get through the book during our time together, if mistakes still existed at the end of the day, Edna kept Lori after school also. Edna continued to perceive Lori’s mistakes as carelessness. That Lori maintained a sort of gritted-teeth composure throughout Edna’s disciplinary campaign and still did not get her work right convinced Edna it was a battle of wills.

The tension began to show on both sides. In with me, Lori could not concentrate at all. Everything would distract her. As the number of days lengthened, a distressful restlessness overtook her. As soon as she came into the room and sat down, she would have to get up again. Down, up, down, up. While working, she would lean back in her chair every few minutes, close her eyes and shake her hands at her sides to relieve the pressure. Edna was not escaping unharmed either. She redeveloped migraines.

The next Monday things came to a head. At Lori’s appointed time with me she did not arrive. I waited. Over by the animal cages with Boo, I talked to him about Sam in his shell. Yet my eyes were on the clock and my mind on Lori.

I knew Lori was not absent; I had seen her in the halls earlier. Finally when fifteen minutes had passed and she still did not show up, I took Boo by the hand and we went to investigate.

“I sent her to the office,” Edna replied at the door of her first-grade classroom. She shook her head. “That child has had it in this room, let me tell you. She took her reading workbook and threw it clear across the room. Nearly whacked poor Sandy Latham in the head. Could have put an eye out, the way she threw it. And then when I told her to pick it up, she turns around as pretty as you please, just like she was some little queen and says … well, let me tell you, it was a tainted word. Can you imagine? Seven years old and she uses words like that? I have the other children to think of. I’m not going to have them hearing words like that. Not in here. And I told her so. And sent her right down to Mr. Marshall. She earned that paddling.”

I too went right down to Mr. Marshall’s office, dragging Boo behind me because there was nothing else to do with him. There, sitting on a chair in the secretary’s office, was Lori, tears over her cheeks, a mangled tissue in her hands. She would not look up as Boo and I entered.

“May Lori come down to class with me?” I asked the secretary. “It’s her time in the resource room.”

The secretary looked up from her typing. First at me and then, craning her neck to see over the counter, at Lori. “Well, I suppose. She was supposed to sit there until she finished crying. You done crying?” she asked across the formica barrier.

Lori nodded.

“You going to behave yourself for once? No more trouble this afternoon?” the secretary asked.

Another nod.

“You’re too little to be getting in all this trouble.”

Lori rose from the chair.

“Did you hear me?” the secretary asked.

Lori nodded.

Back to me, the secretary shrugged. “I guess you can have her.”

We walked down the hallway hand in hand, the three of us. My head was down as we were walking and I looked at our clasped hands. Lori’s nails were bitten down to where blood caked around the little finger.

Inside our room I let go of both of them. Boo minced off to see Benny. Lori went directly to the worktable while I shut the door and fastened the small hook-and-eye latch I had purchased at the discount store.

On top of the worktable was one of the pre-primers I had been using with another student earlier in the day. Lori walked over to it and regarded it for a long moment in a serious but detached manner, as one views an exhibit in the museum. She looked back at me, then back at the door. Her face clouded with an emotion I could not decipher.

Abruptly Lori knocked the book off the table with a fierce shove. Around the table she went and kicked the book against the radiator. She grabbed it and ripped at the brightly colored illustrations. “I hate this place! I hate it, I hate it, I hate it!” she screamed at me. “I don’t want to read. I don’t ever want to read. I hate reading!” Then her words were swallowed up in sobs as the pages of the pre-primer flew.

Tears everywhere and Lori was lost in her frenzy. She clawed the book, her nails squeaking across the paper. Her entire body was involved, bouncing up and down in a tense, concentrated rage. When the last pages of the pre-primer lay crumpled, she pitched the covers of the book hard at the window behind the table. Then she turned and ran for the door. Not expecting it to be locked, she fell hard against it with a resounding thunk. Giving up a wail of defeat, she collapsed, her body slithering down along the wood of the door like melting butter.

Boo and I stood frozen. The entire drama was probably measurable in seconds. There had been no time to respond. Now in the deafening silence, I could hear only the muted frantic fluttering of Boo’s hands against his pants. And Lori’s low, heavy weeping.

Chapter Four (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

The class was formed.

Following the incident in Edna’s room, Lori was assigned to me all afternoon, along with Boo. Tim and Brad, my two other afternoon resource students, were transferred to the morning, and now I had Lori and Boo alone for almost three hours. Although officially I was still listed as a resource teacher and these two as simply resource students, all of us knew I had a class.

According to the records, Lori was assigned the extra resource time for “more intensive academic help.” However, Dan Marshall, Edna and I – and probably Lori herself – knew the change had come about because we had come too close to disaster. Perhaps in a different situation Lori could have managed full time in a regular classroom, but here she couldn’t. In Edna’s conservatively structured program, Lori did not have adequate skills to function. To relieve the pressure on both sides, she spent the mornings in her regular class where she would still receive reading and math instruction along with lighter subjects, but in the afternoons when Edna concentrated on the difficult, workbook-oriented reading skills, Lori would be with me.

So there we were, the three of us.

Boo remained such a dream child. As so many autistic-like children I had known, he possessed uncanny physical beauty; he seemed too beautiful to belong to this everyday world. Perhaps he did not. Sometimes I thought that he and others like him were the changelings spoken of in old stories. It was never inconceivable to me that he might truly be a fairy child spirited from the cold, bright beauty of his world, trapped in mine and never quite able to reconcile the two. And I always noticed that when we finally reached through to an autistic or schizophrenic child, if we ever did, that they lost some of that beauty as they took on ordinary interactions, as if we had in some way sullied them. But as for Boo, thus far I had failed to touch him, and his beauty lay upon him with the shining stillness of a dream.

Our days did not vary much. Each afternoon Boo’s mother would bring him. She would open the door and shove Boo through, wave good-bye to him, holler hello to me and leave. Not once could I entice her through that door to talk.

Once inside Boo would stand rigid and mute until he was helped off with his outer clothes. If I did aid him, he would come to life again. If I did not, he would continue standing, staring straight ahead, not moving. One day I left him there in his sweater to see what would happen since I knew from his disrobing episodes that he was capable of getting out of his clothes when inspired. That day he stood motionless until 2:15, nearly two hours, finally, I gave in and took off his sweater for him.

The only definite interest Boo had was for the animals. Benny particularly fascinated him. Once he thawed from his arrival, he would head for the animal corner. The only time Boo gave any concrete sign of attending to his environment or attempting any communication was when he stood in front of Benny’s driftwood and flicked his fingers before the snake’s face and hrooped softly. Otherwise, Boo’s time was spent rocking, flapping, spinning or smelling things. Each day he would move along the walls of the classroom inhaling the scent of the paint and plaster. Then he would lie down and sniff the rug and the floor. Any object he encountered would first be smelled, sometimes tasted, then tested for its ability to spin. To Boo there seemed to be no other way of evaluating his environment.

Working with him was difficult. Smelling me was as entertaining to him as smelling the walls. While I held him he would whiff along my arms and shirt, lick at the cloth, suck at my skin. Yet the only way I could focus his attention even for a moment was to capture him physically and hold him, arms pinned to his sides, while I attempted to manipulate learning materials. Even then Boo would rock, pushing his body back and forth against mine. The simplest solution I found was to rock with him. And every night after school I washed the sticky saliva off my arms and neck and wherever else he had reached.

Boo’s locomotion around the room was generally in an odd, rigid gait. Up on his toes he moved like the mimes I had seen in Central Park. However, on rare occasions, usually in response to some secret conversation with Benny or the finches. Boo would come startlingly to life. He would begin with ape laughter, his eyes would light up and he would look directly at me, the only time that ever occurred. Then off around the room he would run, the stiffness gone, an eerie grace replacing it. Stripping down until he was completely nude, he would run and giggle like a toddler escaped from his bath. Then as suddenly as it started, that moment of freedom would pass.

Aside from the occasional hroops and whirrs, Boo initiated no communication. He echoed incessantly. Sometimes he would echo directly what I had just said. More frequently he echoed commercials, radio and TV shows, weather and news broadcasts and even his parents’ arguments – all things heard long in the past. He was capable of repeating tremendous quantities of material word for word in the exact intonation of the original speaker. A supernatural aura often settled down among us as we worked to the drone of long-forgotten news events or other people’s private conversations.

The first days and even weeks after Lori arrived full time in the afternoons, I was perplexed as to how to handle these two very different children together effectively. I could sometimes give Lori something to do and go work with Boo. However, there was no reverse of that. To accomplish anything at all with Boo, one had to be constantly reorienting his hands, mouth, body and mind. Still there was a certain magic with us. Lori interested Boo. He would steal furtive glances at her while all the rest of him was robot stiff. Occasionally he would turn his head when she mentioned his name in conversation. He would give very, very soft hroops every once in a while when he was sitting near Lori and not near Benny at all. As I watched them that first week that Lori had joined us full time in the afternoon, I was pleased. This would never be an easy way to spend an afternoon, but likewise, it would never be dull. I was glad we had become a class.

One result of Lori’s entrance into my room half-days was meeting her father. We first came face to face in the meeting with Edna and Dan over Lori’s placement. I liked Mr. Sjokheim immediately. He was a big man, perhaps not as tall as wide, although it was a congenial plumpness mostly around the belt area, as if he had enjoyed all his Sunday dinners. He had a deep, soft voice and a ringing laugh that carried far out into the hallway. Even in that early meeting as I listened to him, it became apparent where Lori had acquired much of her caring attitude.

After the first week passed with Lori in my room, I invited Mr. Sjokheim in after school to get acquainted. By profession he was an experimental engineer. He worked in the laboratory of an airplane company and dealt with aspects of environmental impact of airplanes. He derived great pleasure from talking about various programs he had implemented locally to cut down on both air and noise pollution by the company.

Tragedy, however, had marked Sjokheim’s personal life. He and his wife had had an only child, a daughter, several years before. When the girl was four years old, she fell through a plate-glass window. The glass had penetrated her throat and she had nearly bled to death. Quick action by paramedics saved her life, however, she suffered severe brain damage from loss of oxygen and became comatose. Yet the child did not die. For three years after the accident she remained hospitalized and on life-support equipment before finally succumbing. She never regained consciousness in all that time.

With their finances drained and their lives left empty, the Sjokheims had moved to our community a few years later to try to start over. Soon after, Lori and her twin sister Libby were placed in the Sjokheim home as foster children. They were four years old. Very early, Mr. Sjokheim said, he and his wife realized that they wanted to adopt the twins. Yes, they knew of the brutal amount of abuse the girls had suffered and of the possibilities of complications from it, both physically and emotionally. That did not matter. After all, he said to me with a smile, they needed us and we needed them. What more did it take?

Apparently not much more. The twins were cleared for adoption soon after their fifth birthday and the Sjokheims started proceedings. Then suddenly Mrs. Sjokheim became seriously ill. The diagnosis was simple. Too simple and too swift for its impact. Cancer. She died before Lori and Libby turned six.

There had been no question in Sjokheim’s mind that he would keep the girls. If they had needed one another before, they surely did now. However, the proceedings became complicated. He was over the usual adoptive-parent age limit. Allowances had been made before because his wife was younger and because the twins themselves were old for adoption, and because there were two children. Now the agency balked. The twins were in a single-parent home and that parent was the father while they were female. Much legal rigmarole followed. In the end because of the twins’ generally unfavorable prospects for other adoptions and because the Sjokheims had nearly completed the procedure at the time of Mrs. Sjokheim’s death, the state allowed Mr. Sjokheim to go ahead.

The last year and a half had not been easy. At forty-five he was unused to being the only parent of two young children. The twins were coping with the second loss of a mother in two years. He had had to move to be nearer their regular baby-sitter; he had had to make some career decisions he had never anticipated. He was no longer head engineer in his lab. It had simply taken too much time. Now he was living in a smaller house and making a smaller salary, and his main job was raising Lori and Libby. Some days, he said with a weary smile, he seriously questioned the wisdom of his choice to be a single father. For the most part, however, there could have been no other life for him.

The problems with Lori showed up early. Even before the twins had started school, Mrs. Sjokheim had tried to teach them to write their names. Libby learned immediately. Lori never did. The first year of school had been chaotic. Between her inability to recognize or write any written symbols and her mother’s increasing illness, Lori did not cope well. She was hyperactive and inattentive. At home she developed enuresis and nightmares. Because both Libby and Lori were marked by that traumatic year and because they had September birthdays, making them younger than most other children in their class, the school personnel and Mr. Sjokheim had decided to retain both girls in kindergarten for an additional year. Libby profited from the retention. The more introverted, less expressive of the twins, she grew. The next year she became an excellent student, more confident and outgoing. Lori had no such luck. The second year in kindergarten was no less disastrous than the first. About midyear everyone began to realize that there must be more wrong with Lori than simple immaturity or poor adjustment to family crisis. Some things she could do with great ease, such as count aloud or even add verbally, a skill Libby had not acquired. Other things such as writing her name or identifying letters seemed impossible. The final blow came when she suffered a grand mal seizure in class one day.

Mr. Sjokheim took his daughter to the doctor. From there they were referred to university facilities on the far side of the state. Lori was admitted to the university hospital and given a complete neurological workup. When X-rays revealed the fracture line and later the brain lesions, a search was instigated through the adoption agency for old medical records. The abuse incident and the surgery to remove bone fragments and repair the skull came to light.

The doctors were hesitant to give pat answers. The epilepsy, which had probably been going on in the form of petit mal seizure for years, was undoubtedly a result of the abuse damage. The small unnoticed seizures alone could have accounted for much of Lori’s school failure. But as to her other problems, in the areas of symbolic language, there was no way of knowing. Too little about the operations of the brain was understood, and there were too many other possibilities. She was the younger twin, had been born prematurely; perhaps there might have been a birth injury or a congenital defect. Who could tell? Yet that evil crack running so squarely over the lesions on an otherwise normal-appearing brain gave mute testimony to what even the leading neurologist on Lori’s team admitted believing the answer to be.

Following the hospitalization and testing, Lori was placed on anti-convulsant medication and sent home. The seizures were controlled but back in kindergarten the struggle with learning continued. Lori left in June to go on to first grade, able to jabber off the alphabet and count up to 1000 but not even recognizing the letters of her name.

Still there remained a little encouragement from the doctors that she might improve. She was so young when the injury occurred that her brain might be capable of learning new pathways to circumvent the damaged area. If it was going to occur, it would most likely happen before she entered adolescence.

Mr. Sjokheim expressed relief that Lori had been moved half-days from the first grade. She needed more specialized support and he had seen the pressure building when she could not meet Edna’s demands.

He spoke to me about Lori’s actions and reactions over the past weeks. Then he paused, pinched the bridge of his nose and wearily shook his head. “I worry so much about her,” he said. “Not about the reading really. I figure if that’s meant to happen, it will. But …” He stared at the tabletop. “But sometimes I wake up at night … and before I can get back to sleep, well, she creeps into my head. I think about her. I think about all the little things she does to convince herself that this much failure does not matter to her. And I think how it does matter.” He looked up at me. His eyes were a soft, nondescript hazel color. “It’s worst at night for me. When I’m alone and I get to thinking about her. There’s no way to distract myself then. And you know … you know, it sounds stupid to say, but sometimes it makes me cry. I actually get tears in my eyes.”

I watched him as he spoke and thought about what it must be like to be Lori. That was difficult. I had always been a good student who had never had to try. I could not imagine what it must be like to be seven and to have known failure half my life, to get up every morning and come spend six hours in a place where try as I might, I could never really succeed. And by law Lori had at least seven more years ahead of her of this torture, as many years left as she had lived. Men murdered and received shorter prison terms than that. All Lori had done was to be born into the wrong family.

Chapter Five (#uf64aa853-cb30-58cf-aa1b-880700df8891)

Once long ago when I was a very little girl I told my mother that when I grew up I was going to be a witch and marry a dinosaur. At four that seemed a marvelous plan. I adored playing witch in the backyard with my friends and I was passionately interested in dinosaurs. There could be no better life than one in which I could do what I loved doing and live with one I found immensely fascinating.

I haven’t changed a lot in that respect. Somewhere deep inside there is still a small four-year-old looking for her dinosaur. And there was no denying that the single hardest task as my career progressed had become synchronizing life with the kids with the remainder of my life outside school.

The task did not seem to be getting any easier. I know I did not help things much. I loved my work profoundly. It stretched me to the very limits of my being. The time spent within the walls of my classroom had formed fully my views of life and death, of love and hate, of justice, reality and the unrestrained brutal beauty of the human spirit. It had given me my understanding of the meaning of existence. And in the end it had put me at ease with myself. I had become the sort of person who got home Fridays and waited anxiously for Mondays. The kids were my fix, the experience a spiritual orgasm.

That kind of intensity was hard to compete with. I tried to step back from it and appreciate the slower, less rabid hours I spent outside school but I knew my appetite for the extreme, both mentally and emotionally, made me a complicated companion.

Joe and I had been seeing each other for almost a year. The old adage had been true in our case: opposites attract. He was a research chemist at the hospital. He worked only with things. Indeed, he loved things: cars that handled well, old rifles, good wine and clothes. Joe was the only man I had ever dated who actually owned a tuxedo. And perhaps because things so seldom needed talking to, Joe was never a talker. He was not a quiet type; he just never wasted words beyond the concrete. He could not comprehend their practicality in some areas. Why talk about things if one could not change them? Why discuss things that have no answers?

Fun for Joe was getting dressed up and going out to eat, going to a party, going dancing. Just plain going out.

And there I was with my wardrobe of three pairs of Levi’s and a military jacket left over from student protest days. When I came home from work I wanted to stay home, to cook a good meal, to talk. I sorted my life out with words. I built my dreams with them.

We made an unlikely pair. But whatever our differences, we seemed to get around them. We fought incessantly. And we made up incessantly, too, which made most of the fighting worthwhile. I loved Joe. He was French, which I found exotic. He was handsome: tall, rugged-looking with wind-blown hair, like those men in perfume advertisements. I don’t think I had ever dated such a handsome man and I knew that fed my vanity some. Yet there were better reasons too. He had a good sense of humor. He was romantic, remembering all the little things I was just as likely to dispense with. And perhaps most of all he stretched me in a way different from my work; he kept me oriented toward normalcy and adulthood. He could usually keep my Peter Pan tendencies under control. It was a good, if not always easy, relationship.

As September rolled into October and an Indian summer stretched out warm and lazy across the farmlands, Joe and I were seeing more of each other, but increasingly he began to complain about my work. I was not leaving it at school, he said, which was true enough, I suppose. I had Boo and Lori to think about now and I wanted to share it. I wanted Joe to see Boo’s eerie otherworldliness and Lori’s tenderness because they were so beautiful to me. On more practical levels, I wanted to bounce ideas off someone. I needed to explore those regions of the children’s behavior that I could not comprehend. My best thinking was always done aloud.

All this talk of crazy people depressed him, Joe replied. I ought to put it away at night. Why did I always insist on bringing it home? I sat by quietly when he said that to me and I was filled with sadness. It was then I knew that Joe would never be my dinosaur.

I had meant to fix supper. Joe was coming over. We had not made plans because the night before when we had discussed it, Joe had wanted to see the newest Coppola movie and I had wanted to fix something on the barbecue. Like so many other times when we ended up unable to agree on anything, Joe just said he would be over.

When I came home from school in the evening there was a letter in the mailbox from an old friend who was teaching disturbed children in another state. She related how her kids had made ice-cream one day in class. Instead of using the big, cumbersome ice-cream maker with all its messy rock salt and ice and impossible turning, she had used empty frozen-juice cans inside coffee cans. The children each had their own individual ice-cream makers. The ice-cream set up in less than ten minutes.

My mind ignited as I read the letter, ideas were coming so fast I could not catch them in order. This was just the thing for Boo and Lori and me to do. The class had been disjointed while I tried vainly to juggle them into some sort of academic program. This would make us as class. Lori would be thrilled about doing something of this nature, and what a good experience for Boo. I could make it into a reading experience, a math lesson.

When Joe found me I had my head in the deep-freeze trying to locate a second can of frozen orange juice. I already had the first can thawing on the counter.

“What are you doing?” he asked as he came into the kitchen.

“Hey, listen, would you do me a great big favor, please? Would you run over to the store and buy me another can of orange juice?” I said from the freezer.

“You have one here.”

I straightened up and shut the lid. “I need three and I only have two. Be an angel, would you please? There’s money on top of the dresser. And I’ll get dinner started.”

Joe looked at me and his brow furrowed in a way I could not interpret. He stroked the lapel of his sports coat. “I thought we might go out. I made reservations for us at Adam’s Rib for supper.”

I let out a long, slow breath while I considered things. Glancing sideways, I saw Candy’s letter lying open on the kitchen table. Back to Joe. He looked so handsome in his tweed coat. I noticed he was carrying an eight-track tape in one hand, undoubtedly a new one he had bought for his car stereo and brought in to show me.

Candy’s letter called to me like a Siren. I knew there was no way I could explain that to Joe. The scant six feet between us was measurable in light-years. Joe was not going to understand.

“Not tonight, okay?” My voice was more tentative-sounding than I had meant it to be. “I’ll fix something for us. Okay?”

His brow furrowed further giving him an inscrutable look.

I glanced at the letter again. It sang to me so loudly. “I wanted to make ice-cream. My girlfriend just sent me a new way …”

“We can buy ice-cream, Torey.”

A pause. A pause that grew to be a silence. I was watching him.

“This is different, Joe. It’s for … Well, it’s to do tomorrow with … You see, my girlfriend Candy in New York, she teaches kids like I do.”

Briefly he put a hand up to his eyes as if he were very, very tired. Pressing his fingers tightly against his eyes, he gave a slight shake of his head before dropping his hand. “Not this again.”

“Candy was telling me about doing this with her kids.” There were still big pauses between my sentences as I spoke. Mostly because I had to stop to judge his reaction after each one. Yet I kept hoping that if I explained enough he would understand why I just could not go to Adam’s Rib tonight. Some other night perhaps, but not tonight. Please. Please?

I kept watching his eyes. He had green eyes, but not like Boo’s eyes at all; kaleidoscopic eyes were what Joe had, like looking at the pebbles on the bottom of a stream. His eyes always said a great deal. But I kept trying anyway. “I was thinking maybe we could try out the ice-cream tonight. I need to try it out before I can use it with my kids, and I thought … well, I was hoping … well …” Cripes, not saying a word, and he was still cutting me short. I felt like a little girl. “Well, I was thinking that if it worked and … I could try it at school tomorrow, if it worked for us.” Another pause. “My kids would like that.”

“Your kids would like that?” His voice was painfully soft.

“It wouldn’t take much time.”

“And what about me?”

I looked down at my hands.

“Where the hell do I come in, Torey?”

“Come on, Joe, let’s not fight.”

“We’re not fighting. We’re having an adult discussion, if you can understand that. And I just want to know what it is those children have that no one else in the world seems to have for you. Why can’t you put them away? Just once? Why can’t something else matter to you besides a bunch of fucked-up kids?”

“Lots else matters.”

Another pause. Why, I wonder, are all the important things so easily strangled by small silences?

“No, not really. You never give your heart to anything else. The rest of you is here but you left your heart back at the school. And you’re perfectly glad you did.”