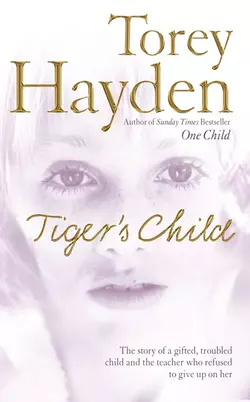

The Tiger’s Child: The story of a gifted, troubled child and the teacher who refused to give up on her

Torey Hayden

Torey Hayden returns with this deeply-moving sequel to her first book, One Child (the Sunday Times bestseller). After seven years, Torey is reunited with Sheila, the disturbed 6-year-old she tried to rescue.Sheila was a deeply disturbed six-year-old when she came into Torey Hayden's life – a story poignantly chronicled One Child. The Tiger's Child picks up the story seven years later. Hayden has lost touch with the child she helped to free from a hellish inner prison of rage and silence. But now Sheila is back, now a gangly teenager with bright orange hair – no longer broken and lost, but still troubled and searching for answers.This story of dedication and caring that began in childhood moves into a new and extraordinary chapter that tests the strength and heart of both Sheila and her one-time teacher. In The Tiger's Child the skilled and loving educator answers the call once again to help a child in need through her difficult yet glorious transition into young womanhood.

Torey Hayden

The Tiger’s Child

Contents

Cover (#ud396f45c-495f-56e1-95dc-7bd631889053)

Title Page (#u063f9cf8-afe5-5624-b408-310f95cdecbd)

Introduction (#u697e9146-526c-5dda-ac22-001aacd3ed6c)

Prologue (#u2f2b0740-7483-5ff9-bcf1-36e9d748e3c7)

Part 1 (#u52ca4c48-e141-590d-86af-e4f19ea74284)

Chapter 1 (#u00ee3639-3059-54ff-91aa-921a4d75d264)

Chapter 2 (#u2968667f-8bd7-5dc0-9f68-8efaa46910fe)

Chapter 3 (#ub1d8dbf1-7955-5408-be96-a798cc521bb8)

Chapter 4 (#ud8590cb6-1f64-5583-9af3-4d7da45b63e0)

Chapter 5 (#uff9f5b54-b2f6-58f1-96b4-ff8677d7a2cf)

Part 2 (#ua1af5b3b-fb31-5675-bd95-62fa8a77493b)

Chapter 6 (#u8de66888-2012-502b-bb2c-a311e06908c6)

Chapter 7 (#ue80d7c3a-3708-55b0-bdd2-2a6b22f6342f)

Chapter 8 (#ub0f0d88b-871b-5286-b9ef-3259abd647be)

Chapter 9 (#ua9de5fc9-e207-586a-85c9-209c20648235)

Chapter 10 (#u60689876-a1ed-553a-a8ef-eadec1cb6941)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Torey Hayden (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise for Torey Hayden and the Tiger’s Child (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_34f05828-4425-56ef-bc1e-0e1c696711a1)

This book is based on the author’s experience as a special education teacher, but names, some identifying characteristics, dialogue, and details have been changed or reconstructed.

Prologue (#ulink_3f0e9226-1f6a-5bb9-8222-6faaf08f9e85)

It was a moment of déjà vu.

Home in Montana visiting my mother, I had nipped out alone on a Sunday morning while she and my young daughter went swimming. It was just after eleven and I was walking through the shopping mall. Most of the stores weren’t open yet, and as a consequence, the broad concourse was shadowy, illuminated only by security lighting.

Suddenly I saw her. Some distance ahead of me down the mall, she was standing in the shadows of a large planter. Long, unkempt hair tumbled down over her shoulders; bangs hung into her eyes; thick, sensual lips were pushed out in a dramatic pout. She stood with arms crossed tightly over her chest, her shoulders pulled up, her face set in an expression of fierce defiance; and yet there was a poignancy about all that fierceness. I suspect she already knew she wasn’t going to win. I was well down the mall when I first saw her, but I recognized her so instantly that adrenaline shot through my veins. Sheila.

A second or two later my intellect caught up. It wasn’t Sheila, of course. More than twenty years have passed since I watched Sheila depart from my classroom on that warm June afternoon. I am no longer the angry young teacher I was. My teaching days are, at least for the time being, behind me and I have exchanged youth—with some reluctance—for middle age. Yet, for those brief few minutes in the shopping mall, the years disappeared. I was pulled back into the seventies, into my workaholic twenties, to feel once again, however fleetingly, the person I had been and the world as it was then.

Then reality began to impose, layering itself down over the incident rather the way one lays a transparency down over a page. I approached the girl with curiosity, drew up even with her and paused, feigning interest in a nearby shop window so that I could unobtrusively study her. She was older than Sheila had been. She was perhaps seven or even eight. Her hair was darker, more mouse-brown than blond.

My nearness didn’t put off her anger any. I was a stranger, so she ignored me and concentrated all her attention on the open doorway of the huge department store behind me. I couldn’t discern who had upset her so. They had disappeared into the store, but she stood on, her small fists clenched, her tousled hair falling forward, her hopeless, helpless anger emanating from her. Anonymous and silent, I remained where I was, half a dozen feet away, and marveled at how such a small encounter could wipe away so many years, how Sheila could still set my heart beating fast.

Sheila and I, as student and teacher, were only together for five months. Our relationship over that short time evoked dramatic changes in Sheila’s behavior and vastly altered the course of her life. Although less obvious at the time, our relationship also dramatically changed me and vastly altered the course of my life too. This little girl had a profound effect on me. Her courage, her resilience and her inadvertent ability to express that great, gaping need to be loved that we all feel—in short, her humanness—brought me into contact with my own.

The five months Sheila was in my class I chronicled in One Child. It was a private book, never initially written with the intention of publication, but only as my own effort to understand more fully this deeply felt relationship. I was teaching a university graduate class in special education at the time and it is to a student in that class that I owe my thanks. The last day of class she gave me a copy of Ron Jones’s The Acorn People, and inscribed it in the front: To Torey, in hopes that someday you might write about Sheila, Leslie and all the others.

One Child now spans the world in twenty-two languages and has brought me into contact with individuals from Sweden to South Africa, from New York to Singapore. One reader wrote from a base in Antarctica; a handful of letters came from behind the Iron Curtain before it fell; and I have just recently received my first correspondence over One Child from mainland China. The universal appeal of watching Sheila grow and change has only been matched by one thing, a question: What happened next?

One Child is a true story, based on real people and real people’s experiences. I hesitated to write a sequel simply because six-year-old Sheila was so appealing and the period we spent together was so positive. Indeed, my One Child editor went so far as to suggest I not include in the epilogue of the book what had actually been happening to Sheila in the time since we had parted. Real lives are seldom as satisfying as fiction, or even as satisfying as judiciously edited nonfiction, and it was felt the interim period between my class and the time I wrote One Child would make too grim an ending for such an upbeat story. Thus, the book concluded with Sheila’s beautiful poem, but no details.

I’ve now changed my mind, not only in response to the countless queries from my readers, but also in response to Sheila, who, against remarkable odds, has grown into an engaging, articulate young woman. Those five months we spent together did have a profound effect on her, but One Child, although I hadn’t meant it to, tells my story. The experience for Sheila was quite a different one and here, to quote Paul Harvey, is the rest of the story.

Part 1 (#ulink_2e0fa699-9ee6-56bb-b0c5-303adddf8ca8)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_173091b4-434c-55de-959e-fc3346059ddd)

The article in the newspaper was tiny, considering the crime. It told of a six-year-old girl who had lured a local toddler from his yard, taken him to a nearby woodland, tied him to a tree and set fire to him. The boy, badly burned, was in hospital. All that was said in what amounted to no more than a space filler below the comic strips on page six. I read it and, repulsed, I turned the page and went on.

Six weeks later, Ed, the special education director, phoned me. It was early January, the day we were returning from our Christmas break. “There’s going to be a new girl in your class. Remember that little girl who set fire to the kid in November …?”

I taught what was affectionately referred to in our district as the “garbage class.” It was the last year before congressional law would introduce “mainstreaming,” the requirement that all special needs children be educated in the least restrictive environment; and thus, our district still had the myriad of small special education classrooms, each catering to a different disability. There were classes for physically handicapped, for mentally handicapped, for behaviorally disordered, for visually impaired … you name it, we had it. My eight were the kids left over, the ones who defied classification. All of them suffered emotional disorders, but most also had mental or physical disabilities as well. Out of the three girls and five boys in the group, three could not talk, one could but refused and another spoke only in echoes of other people’s words. Three of them were still in diapers and two more had regular accidents. As I had the full number of children allowed by state law for a class of severely handicapped children, I was given an aide at the start of the year; but mine hadn’t turned out to be one of the bright, hardworking aides already employed by the school, as I had expected. Mine was a Mexican-American migrant worker named Anton, who had been trawled from the local welfare list. He’d never graduated from high school, never even stayed north all winter before, and certainly had never changed diapers on a seven-year-old. My only other help came from Whitney, a fourteen-year-old junior high student, who gave up her study halls to volunteer in our class.

By all accounts we didn’t appear a very promising group, and in the beginning, chaos was the byword; however, as the months passed, we metamorphosed. Anton proved to be sensitive and hardworking, his dedication to the children becoming apparent within the first weeks. The kids, in return, responded well to having a man in the classroom and they built on one another’s strengths. Whitney’s youth occasionally made her more like one of the children than one of the staff, but her enthusiasm was contagious, making it easier for all of us to view events as adventures rather than the disasters they often were. The kids grew and changed, and by Christmas we had become a cohesive little group. Now Ed was sending me a six-year-old stick of dynamite.

Her name was Sheila. The next Monday she arrived, being dragged into my classroom by Ed, as my principal worriedly brought up the rear, his hands flapping behind her as if to fan her into the classroom. She was absolutely tiny, with fierce eyes, long, matted blond hair and a very bad smell. I was shocked to find she was so small. Given her notoriety, I had expected something considerably more Herculean. As it was, she couldn’t have been much bigger than the three-year-old she had abducted.

Abducted? I regarded her carefully.

Bureaucracy being what it is in school districts, Sheila’s school files didn’t arrive before she did; so when she went off to lunch on that first day, Anton and I took the opportunity to go down to the office for a quick look. The file made bleak reading, even by the standards of my class.

Our town, Marysville, was in proximity to a large mental hospital and a state penitentiary, and this, in addition to the migrants, had created a disproportionate underclass, many of whom lived in appalling poverty. The buildings in the migrant camp had been built as temporary summer housing and many were literally nothing but wood and tar paper that lacked even the most basic amenities, but they became crowded in the winter by those who could afford nothing better. It was here that Sheila lived with her father.

A drug addict with alcohol problems, her father had spent most of Sheila’s early years in and out of prison. He had no job. Currently on parole, he was attending an alcohol abuse program, but doing little else.

Sheila’s mother had been only fourteen when, as a runaway, she took up with Sheila’s father and became pregnant. Sheila was born two days before her mother’s fifteenth birthday. A second child, a son, was born nineteen months later. There wasn’t much else relating to the mother in the file, although it was not hard to read drugs, alcohol and domestic violence between the lines. Whatever, she must have finally had enough, because when Sheila was four, she left the family. From the brief notes, it appeared that she had intended to take both children with her, but Sheila was later found abandoned on an open stretch of freeway about thirty miles south of town. Sheila’s mother and her brother, Jimmie, were never heard from again.

The bulk of the file detailed Sheila’s behavior. At home the father appeared to have no control over her at all. She had been repeatedly found wandering around the migrant camp late at night. She had a history of fire setting and had been cited for criminal damage three times by the local police, quite an accomplishment for a six-year-old. At school, Sheila often refused to speak, and as a consequence, virtually nothing was contained in the file to tell me what or how much she might have learned. She had been in kindergarten and then first grade in an elementary school near the migrant camp until the incident with the little boy had occurred, but there were no assessment notes. In place of the usual test results and learning summaries was a catalog of horror stories detailing Sheila’s destructive, often violent, behavior.

At the end of the file was a brief summary of the incident with the toddler. The judge concluded that Sheila was out of parental control and would be best placed in a secure unit, where her needs could be better met. In this instance, he meant the children’s unit at the state mental hospital. Unfortunately, the unit was at capacity at the time of the hearing, and thus, Sheila would need to await an opening. A recently dated memo was appended detailing the need to provide some form of education, given her age and the law, but no one bothered to mince words. Her placement was custodial. This meant she had to be kept in school for the time being, because of the specifics of the law, but I need not feel under any obligation to teach her. With Sheila’s arrival, my room had become a holding pen.

Youth was my greatest asset at that point in my career. Still fired with idealism, I felt strongly that there were no problem kids, only a problem society. Although initially reluctant to take Sheila, it had been because my room was crowded and my resources overstretched already, not because of the child herself. Thus, once I had her, I regarded her as mine and my class was no holding pen! My belief in human integrity and the inalienable right of each and every one of my children to possess it was trenchant.

Well, almost. Before she was done, Sheila had given all my beliefs a good shaking and she started that very first day. As Anton and I were sitting in the front office that lunch hour, reading Sheila’s file, Sheila was in our classroom scooping the goldfish out of the aquarium and, one by one, poking their eyes out.

Sheila proved to be chaos dressed in outgrown overalls and a faded T-shirt. Everything she said was shrieked. Everything she touched was broken, hit, squashed or mangled. And everyone, myself included, was The Enemy. She operated in what Anton christened her “animal mode.” There was not much “child mode” present in the early days. The slightest unexpected movement she always interpreted as attack. Her eyes would go dark, her face would flush, her body would take on alert rigidity, and from that point it was a finely balanced matter as to whether she would fight, or panic and run away. When she was in her animal mode, our methods were a whole lot more akin to taming than teaching.

Yet …

Sheila was different. There was something electric about her, about her eyes, about the sharpness of her movements that superimposed itself over even her most feral moments. I couldn’t articulate what it was, but I could sense it.

I loved my children dearly, but the truth was, they were not a very bright lot. Most children with emotional difficulties use so much mental energy coping that there simply isn’t much left for learning. Additionally, other syndromes often occur in conjunction with psychological problems, either contributing to them or resulting from them. For example, two of my children suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome and another had a neurological condition that was causing a slow deterioration of his central nervous system. As a consequence, none of the children was functioning at an average level for his or her age, although undoubtedly several were of normal intelligence. Thus, it came as a surprise to me to discover during Sheila’s early days with us that she could add and subtract well, because she had managed only three months of first grade.

A bigger surprise came days later, when I discovered she could give the meanings of unusual words. One such word was “chattel.”

“Wherever did you learn a word like this?” I asked when my curiosity finally overwhelmed me.

Sheila, little and dirty and very smelly, sat hunched up on her chair across the table from me. She peered up through matted hair to regard me. “Chattel of Love,” she replied and added in her peculiar dialect, “it be the name of a book I find.”

“Book? Where? What book?”

“I don’t steal it,” she retorted defensively. “It be in the garbage can. I find it.”

“Where?”

“I do find it,” she repeated, obviously believing this was the issue I was trying to explore.

“Yes, okay,” I replied, “but where?”

“In the ladies’ toilets at the bus station. But I don’t steal it.”

I smiled. “No, I’m sure you didn’t. I’m just interested in hearing about it.”

She regarded me suspiciously.

“What did you do with the book?” I asked.

Sheila clearly couldn’t puzzle out why I wanted to know these things. “Well, I read it,” she said, her voice full of disbelief, as if I’d asked a very silly question. There was a worried edge to it, however. She still sensed it was an accusation.

“You read it? It sounds like a rather grown-up book.”

“Well, I don’t read all of it. But on the cover it say Chattel of Love and so I do be curious about it, ’cause of the picture,’ cause of what the man be doing to the lady on the cover.”

“I see,” I replied uncertainly.

She shrugged. “But I couldn’t find nothing good in it, so I throw it away again.”

With an IQ we soon discovered to be in excess of 180, Sheila was electric all right. Indeed, she was more like nuclear.

Discovering Sheila was a highly gifted child intellectually did nothing to change the facts of her grinding poverty, her abusive background or her continuing and continually outrageous behavior. Uncertain where to start when there was so much that needed improving, I began with the very smallest things, those I knew were within my power to change.

Sheila’s hygiene was appalling. She literally had only one set of clothes: a faded brown-striped T-shirt and a pair of worn denim overalls, a size too small. With these went a pair of red-and-white canvas sneakers with holes in the toes. She had underwear, but no socks. If any of these were ever washed, there was little evidence of it.

Certainly Sheila wasn’t washed. The dirt was worn in on her hands and her elbows and around her ankles, so that dark lines had formed over the skin in these areas. Worse, she was a bed wetter. The smell of stale urine permeated whatever part of the classroom Sheila occupied. When I quizzed Sheila about washing facilities, I discovered they had no running water.

This seemed the best place to start. She was so unpleasant to be near that it distracted all of us from the child herself; so I came armed with towels, soap and shampoo and began to bathe Sheila in the large sink at the back of the classroom.

I was washing her when I first noticed the scars. They were small, round and numerous, especially along her upper arms and the insides of her lower arms. The scars were old and had long since healed, but I recognized them for what they were—the marks left when a lit cigarette is pressed against the skin.

“Does your dad do things that cause these?” I asked, trying to keep my voice as casual and conversational as possible.

“My pa, he wouldn’t do that! He wouldn’t hurt me bad,” she replied, her tone prickly. “He loves me.” I realized she knew what I was asking.

I nodded and lifted her out of the water to dry her. For several moments Sheila said nothing, but then she twisted around to look me in the eye. “You know what my mama done, though?”

“No, what?”

She lifted up one leg and turned it for me to see. There, on the outer side just above the ankle, was a wide white scar about two inches long. “My mama, she push me out of the car and I fall down so’s a rock cutted up my leg right here. See?”

I bent forward and examined it.

“My pa, he loves me. He don’t go leaving me on no roads. You ain’t supposed to do that with little kids.”

“No, you’re not.”

There was a moment’s silence while I finished drying her and began to comb out her newly washed hair. Sheila grew pensive. “My mama, she don’t love me so good,” she said. Her voice was thoughtful, but calm and matter-of-fact. She could have been discussing one of the other children in the class or a piece of schoolwork or, for that matter, the weather. “My mama, she take Jimmie and go to California. Jimmie, he be my brother and he be four, ’cept he only be two when my mama, she leave.” A moment or two elapsed and Sheila examined her scar again. “In the beginning, my mama taked Jimmie and me, ’cept she got sick of me. So, she open up the door and push me out and a rock cutted up my leg right here.”

Those early weeks with Sheila were a roller-coaster ride. Some days were up. Delighted awe at this new world she found herself in made Sheila a sunny little character. She was eager to be accepted into the group and in her own odd way tried desperately to please Anton and me. Other days, however, we went down, sometimes precipitously. Despite her brilliant progress right from the beginning, Sheila remained capable of truly hair-raising behavior.

The world was a vicious place in Sheila’s mind. She lived by the creed of doing unto others before they do unto you. Revenge, in particular, was trenchant. If someone wronged Sheila or even simply treated her a bit arbitrarily, Sheila exacted precise, painful retribution. On one occasion, she caused hundreds of dollars’ worth of damage in another teacher’s room in retaliation for that teacher’s having reprimanded her in the lunchroom.

What saved us was a complicated bus schedule. In the months prior to coming into my room, Sheila’s behavior had gotten her removed from two previous school buses and the only one available to her now was the high school bus. Unfortunately, this did not leave for the migrant camp until two hours after our class got out. Thus Sheila had to remain after school with Anton and me until that time.

I was horrified when I first found out, because those two hours after school were my planning and preparation time and I couldn’t imagine how I would get on with things while simultaneously having to baby-sit as unpredictable a child as Sheila. There was, however, no choice in the matter.

Initially, I let her play with the classroom toys while I sat at the table and tried to get on with my work, but after fifteen minutes or so on her own, she’d inevitably pull away and come to stand over me while I worked. She was always full of questions. What’s that? What’s this for? Why are you doing that? How come this is like this? What do you do with that thing? Constantly. Until I realized we were talking much of the time. Until I realized how much I enjoyed it.

She liked to read and she could, I think, read virtually anything I placed in her hands. What stopped her was not her ability to turn the letters on the page into words, but rather to turn them into something meaningful. Sheila’s life was so deprived that much of what she read simply made no sense to her. As a consequence, I began reading with her.

There was something compelling about sharing a book with Sheila. We would snuggle up together in the reading corner as I prepared to read aloud to her and Sheila would be so ravenous for the experiences the book held that her entire body’d grow taut with excitement. Winnie the Pooh, Long John Silver and Peter Pan proved sturdier magic than Chattel of Love. However, of all the books, it was Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince that won Sheila’s heart. She adored this bemused, perplexing little character. His otherness she understood perfectly. Mature one moment, immature the next, profound, then petty, and always, always the outsider, the little prince spoke deeply to Sheila. We read the book so many times that she could quote long passages by heart.

When not reading, we simply talked. Sheila would lean on the table and watch me work, or we would pause at some point in a book for me to explain a concept and the conversation would go from there, never quite returning to the story at hand.

Progressively, I learned more about Sheila’s life in the migrant camp, about her father and his lady friends who often came back to the house with him late at night. Sheila told me how she hid his bottles of beer behind the sofa to keep him from drinking too much, and how she got up to put out his cigarettes after he had fallen asleep. I came to hear more about her mother, her brother and the abandonment. And I heard about Sheila’s other school and her other teachers, about what she did to fill her days and her nights, when she wasn’t with us. In return, I gave her my world and the hope that it could be hers as well.

Those two hours were a godsend. All her short life Sheila had been ignored, neglected and often openly rejected. She had little experience with mature, loving adults and stable environments, and now, discovering their existence, she was greedy for them. The busy atmosphere of the classroom during the day, supportive as it was, did not allow for the amount of undivided attention Sheila required to make up for all she had lacked. It was in the gentle silence of the afternoon when we were alone, that she dared to leave behind her old behaviors and try some of mine.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_1f8df8b0-0590-5c7e-bccb-fc78bf7b9e5d)

The real issue for Sheila was what had happened between her and her mother on that dark highway two years earlier. Given her extraordinary giftedness, the matter did not remain inarticulate. With exquisite clarity, she gave a voice to her agony.

The relationship between the abandonment and Sheila’s difficult behavior became most obvious over schoolwork. Despite her brilliance, Sheila simply refused to do any written papers. I hadn’t made the connection initially. I saw the aggressive misbehavior as waywardness and only afterward realized it was a ploy to keep her from having to sit down at the table and take a pencil in hand. Coercing her to the table proved a major battle and even then she held out, refusing to work. When she did eventually start accepting paperwork, she would still crumple two or three imperfect efforts before finally finishing one.

On one occasion, she wasn’t even in class but alone after school with me. She had found a ditto master of a fifth-grade math test in the office trash can, when she had come down with me while I ran off some papers. Sheila loved math. It was her best subject and she fell upon this with great glee. It was on the multiplication and division of fractions, subjects I had never taught Sheila, but as she scanned the paper, she felt certain she could do them. Back in the classroom, she settled across the table from me and began to write the answers on the paper—a very unusual response for Sheila. When she finished, she proudly showed it to me and asked if she had done them right. The multiplication problems were done correctly, but unfortunately she had not inverted the fractions for the division, so those were all wrong. Turning the paper over, I drew a circle and divided it into parts to illustrate why it was necessary to invert. Before I had even spoken, Sheila perceived that her answers weren’t right. She whipped up the paper from under my pencil, smashed it into a tiny ball and pounded on the table before flopping down, head in her arms.

“You didn’t know, sweetheart. No one’s taught you this.”

“I wanted to show you I could do them without help.”

“Sheil, it’s nothing to get upset about. You did nicely. You tried. That’s the important part. Next time you’ll get them right.”

Nothing I said comforted her and she sat for a few moments with her hands over her face. Then slowly her hands slid away and she uncrumpled the paper, pressing it smooth on the tabletop. “I bet if I could have done math problems good, my mama, she wouldn’t leave me on no highway, like she done. If I could have done fifth-grade math problems, she’d be proud of me.”

“I don’t think math problems have anything to do with it, Sheila.”

“She left because she don’t love me no more. You don’t go leaving kids you love on the highway, like she done me. And I cut my leg, see?” For the hundredth time the small white scar was displayed. “If I’d been a gooder girl, she wouldn’t have done that.”

“Sheil, we just don’t know what happened, but I suspect your mama had her own problems to straighten out.”

“But she copeded with Jimmie. How come she copeded with Jimmie and left me?”

“I don’t know, love.”

Sheila looked across the table to me, that haunted, hurt expression in her eyes. “Why did it happen, Torey? Why did she tooked him and leaved me behind? What made me such a bad girl?” Her eyes filled with tears, but as always, they never fell.

“Oh, lovey, it wasn’t you. Believe me. It wasn’t your fault. She didn’t leave you because you were bad. She just had too many of her own problems. It wasn’t your fault.”

“My pa, he says so. He says if I be a gooder girl she’d a never done that.”

My heart sank. There was so much to fight, so little to fight with.

The issue colored everything: her work, her behavior, her attitude toward other children and toward adults. As the weeks passed and particularly as we spent so much of the after-school hours in close contact, I knew very well what was being encouraged to happen. I was the first stable, nurturing adult female Sheila had occasion to spend much time with and she grasped at the relationship with greedy desperation.

Was it right to let her? This question was never far from my mind. My training, both in education and in psychology, cautioned rigorously against getting too personally involved with children, and I strove to keep the proper balance. On the other hand, I had always rebelled against the idea of not becoming involved at all. The cornerstone of my personal philosophy was commitment. I felt it was the unequivocal commitment of one individual to another, of me to the child I was working with, that evoked positive change. How could there be genuine commitment without involvement? That was a contradiction in terms.

On a gut level I felt Sheila had to have this relationship and without it she could never go forward. She needed the esteem that comes only from knowing others care for you, others value you sufficiently to commit themselves to you. She needed to know that while her mother might not have been able to provide this kind of commitment, this did not mean that Sheila was unworthy of it. Yet on an intellectual level I knew I was treading a dangerous path.

Just how dangerous came home to me in February, after Sheila had been with us about seven weeks. I had to attend an out-of-state conference, which meant I would be gone from class for two days. Having ample warning, I endeavored to prepare my class for my absence and the anticipated substitute teacher. Sheila reacted with rage.

“I ain’t never, never gonna like you again! I ain’t never gonna do anything you ask. It ain’t fair you go leave me! You ain’t supposed to do that, don’t you know? That be what my mama done and that ain’t a good thing to do to little kids. They put you in jail for leaving little kids. My pa, he says.”

Tirade after tirade and nothing I said, no effort I made to explain I would be gone only for two days abated Sheila’s anger. In my absence she reverted to all the worst of her old behaviors. She fought with the other children, bloodying noses and cracking shins. The record player was destroyed and the small window in the door was cracked. Despite Anton’s efforts to keep her in check, Sheila devastated the classroom and the substitute ended her days in tears.

I had expected better from Sheila and my anger, when she proved so uncooperative, was not a whole lot less than hers. She was a bright girl. She knew how long two days were. And I had gone to strenuous efforts to explain where I’d be, what I’d be doing and when precisely I would be back. She knew. Why could I not trust her to keep herself together for two lousy days?

To be more exact about the matter, I felt betrayed. Having known I was following such a dangerous course in allowing her growing dependence on me, I had wanted straightforward evidence that I was doing the right thing, that her dependence was natural and healthy and not too serious. I was, after all, going to have to walk out of her life in, at most, three and a half months’ time, when the school year ended, and in even less time, if the opening in the children’s unit at the state hospital occurred. For my own peace of mind, I needed reassurance I was helping more than hurting and—I suppose if I’m honest—I expected it from her. I had given her so much that, in my heart of hearts, I had trusted her to give this bit back to me. When she hadn’t, I reacted with an anger I didn’t control at all well.

We had, to put it mildly, a bad day, and even after school, when we were alone, the strained silence remained between us. I offered to do the things we’d come to enjoy so much: to read aloud to her, to let her help me correct my papers, to come down with me to the teachers’ lounge and share a soft drink, but she simply shook her head and busied herself in the far corner of the room with some toy cars. The first after-school hour passed. She rose and went to look out the window. When I next glanced up, she was still there but had turned to watch me.

“How come you come back?” she asked softly.

“I just went away to give a speech. I never intended to stay away. This is my job, here with you kids.”

“But how come you come back?”

“Because I said I would. I like it here. I belong here.”

Slowly, she approached the table where I was working. Her guard had dropped. The hurt was so clear in her eyes.

“You didn’t believe I was coming back, did you?”

She shook her head. “No.”

Chapter 3 (#ulink_b3654abe-31e7-5d7a-a6de-c78098c74a87)

Our falling-out over my absence did not appear to have any lasting effects. Indeed, just the opposite. Sheila developed an intense desire to discuss the incident: I had left her; I had come back. She had gotten angry and destructive; I had gotten angry and, in my own way, destructive. Each small segment she wanted to discuss again and again until it slowly slotted into place for her. The fact that I had come back was, of course, very important to her, but so too was the degree of my anger. Perhaps she felt that now that she had seen me at my worst, she could more fully trust me. I don’t know. Intriguingly, Sheila’s destructiveness virtually disappeared after this incident. She still became angry with great regularity, but never again did she fly into one of her rampaging rages.

Sheila bloomed, like the daffodils, in spite of the harsh winter. Within the limits of her situation, she was now quite clean and, better, she recognized what clean was and endeavored to correct unacceptable levels of dirtiness herself. Increasingly, she interacted with the other children in the class in a friendly and appropriate manner. She had gone home to play with one of the other little girls in the class on a few occasions and they indulged in the usual rituals of little girls’ friendships at school. Academically, Sheila sailed ahead, excited by almost anything I put in front of her. We were still coping with her fear of committing her work to paper, but that too improved through March. It seldom took more than two or three tries before she felt secure enough with what she had written down to let me look at it. She was still extremely sensitive to correction, going off into great sulks, no matter how gently I pointed out a mistake; and on moody days, she could spend much of the time with her head buried in her arms in dismal despair, but we were coping.

It was after school and Sheila and I had returned to The Little Prince yet again. Snuggled down in the pillows of the reading corner together, we had just begun the book. I had come to the part where the little prince demands that the author draw him a sheep.

“A sheep—if it eats bushes, does it eat flowers too?”

“A sheep,” I answered, “eats anything in its reach.”

“Even flowers that have thorns?”

“Yes, even flowers that have thorns.”

“The thorns—what use are they …?”

The prince never let go of a question, once he had asked it. As for me, I was upset over the bolt. And I answered with the first thing that came into my head:

“The thorns are of no use at all. Flowers have thorns just for spite!”

“Oh!”

There was a moment of complete silence. Then the little prince flashed back at me with a kind of resentfulness:

“I don’t believe you! Flowers are weak creatures. They are naive—”

Sheila laid her hand across the page. “I want to ask you something. What’s ‘naive’ mean?”

“It means someone whose ways are simple. They haven’t much experience with the world,” I replied.

“Do I be naive?” she asked, looking up.

“No, I wouldn’t say so. Not for your age.”

She looked back down at the book. “The flower thinks she has experience.”

I nodded.

“But the prince knows she doesn’t.” She smiled. “I do love this part. I love the flower.”

We read on:

So, too, she began very quickly to torment him with her vanity—which was, if truth be known, a little difficult to deal with. One day, for instance, when she was speaking of her four thorns, she said to the little prince:

“Let the tigers come with their claws!”

“There are no tigers on my planet,” the little prince objected. “And anyway, tigers do not eat weeds.”

“I am not a weed,” the flower replied sweetly.

“Please excuse me …”

“I am not at all afraid of tigers—”

The door to the classroom opened and the secretary stuck her head around the door. “Sorry to interrupt, Torey, but there’s a telephone call for you in the office.”

Handing Sheila the book, I rose and went down to take it.

It was the call I was dreading. The director of special education was on the other end of the line: a vacancy had come up in the children’s unit at the state hospital. Sheila’s time in my classroom was over.

To say I was devastated diminishes the enormity of the emotions I felt at that news. Whatever her difficulties, Sheila in no way belonged in a mental hospital. Intelligent, creative, sensitive, perceptive, she belonged here with us and, eventually, back in a normal class in a regular school.

I moaned, I pleaded, eventually I raged. The director listened. We got on well, he and I. I had always counted him among my allies in the district, the sort of man I relied on as a mentor, and this, if anything, made his call harder to take.

“It was settled long before any of us got into it, Torey,” he said. “You know that. There’s nothing we can do.”

Pathetic little flower, I thought, so proud of her fierce thorns, and when the tigers really came, the thorns gave no protection at all.

I simply couldn’t let it happen without a fight. When she had arrived in January, she had presented as bleak a case as I had ever encountered, and if they’d come for her then, I might have accepted it. But now …? The very thought of a child of Sheila’s caliber ending up institutionalized at six froze me to my soul.

That evening when I was home, ostensibly watching television with my boyfriend, Chad, a plan formed in my mind. I had so much evidence of both Sheila’s intelligence and her progress that I wondered if there might be a chance of changing things. It would have to be approached in a formal, unequivocal manner to be taken seriously and it would have to be undertaken rapidly. I glanced over at Chad. He was a very new junior partner in a law firm downtown and was spending much of his time as a court-appointed lawyer to those who couldn’t afford their own legal advice. So he knew the ropes.

“Is there a legal way to contest what they want to do with Sheila?” I asked cautiously.

“You fight it?” he replied, sensing the meaning under my words.

“Someone has to. I’m quite sure the school district would support me. The school psychologist has been in to administer IQ tests. He had evidence of her giftedness. And Ed knows.”

A pause. A few mutterings. I was the sort of person inclined, as Chad described it, “to get the bit between my teeth and run,” so I think he could guess the obsessive nature of what was going to happen.

“Would you take it on for me?” I asked.

“Me?”

Yeah, him.

And so it was. With admirable solidarity, the school district did back me fully. They even paid for Chad’s services. I marshaled together the videotapes I’d made of Sheila in class, her schoolwork, the psychologist’s evaluations and whatever other examples I could find to support Sheila’s steady improvement. The weakest link in the chain was Sheila’s father, who had been in and out of so many institutions himself that he didn’t seem to believe there was any point to pursuing a different life for his daughter. He was deeply suspicious of us because we did. Beneath his boorish behavior, I felt he did genuinely love Sheila, but it took several rather beery evenings between us to convince him we were right.

The hearing was held on the very last day of March, a dark, windy day that promised to bend the daffodils down yet again with snow. Sheila had had to come along, still dressed in her T-shirt and now badly outgrown overalls. They were clean and I had managed to get her father to accept socks and mittens for her from our church donation box, but that was the best I could do. She sat outside the courtroom with an attendant, in case we needed to call her in.

Inside, I saw the parents of the little boy whom Sheila had abducted and set alight. It was the first time I’d encountered them. Up to that moment, the incident that had placed her in my class had seemed distant to me. In truth, I suppose I had kept it distant in my mind in an effort to make such an act of calculated cruelty unreal. Sheila certainly had done some outrageous things and she had done plenty of them in my presence, so I’d always felt I had a realistic picture of her, but for the first time I had to confront the veracity of another point of view. This upset me, if for no other reason than that I had so desperately wanted to feel a hundred percent right in what I was doing just then. In a way I still did. Revenge would not undo the harm done to their son and it would cripple Sheila for life. This was the only right route for this girl. Yet the hearing brought home to me the enormity of what she had done.

The judge ruled in Sheila’s favor. She was to remain under Social Services supervision, but the order for detainment in the children’s unit was rescinded. Joy broke out in the halls of the courthouse, and afterward, Chad and I took Sheila out to celebrate.

It was a magical evening, one of those times when the experience is greater than the sum of its parts. Still high from our success, we went for pizza in a place Chad and I haunted frequently, full of smoke and jazz music and people speaking Italian. Sheila had never had pizza and took to the new experience with animated delight. Indeed, she took to Chad, and he, likewise, to her. He was soon as much under her spell as I was.

They got into a silly contest, the two of them. What would you like best? To eat a worm sundae or brush your teeth with a spider toothbrush? That sort of thing. Until Chad went serious and asked what was the thing she would like best in all the world—for real. A dress, as it turned out. Something pretty to wear. Unable to resist this opportunity to play Santa Claus, Chad soon had us out to the shopping center. Despite all Sheila’s fears that her father wouldn’t let her accept a dress, Chad reassured her and helped her find the one she liked best.

Sheila fell asleep on the way back to her house in the migrant camp.

“Well, Cinderella,” Chad said, coming around to my side of the car and opening the door. He reached down and lifted her up. “The ball’s over.”

She smiled sleepily at him.

“Come on. I’ll carry you in and tell your daddy what we’ve been up to.”

She buried her face in my hair. “I don’t wanna go,” she whispered.

“It’s been a nice night, hasn’t it?” I said.

She nodded and she pressed tighter against me. “Can I kiss you?”

“Yes, I think so,” I said and enveloped her in a tight hug and kissed her first.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_7a1d5213-13fd-5535-bb03-92d49dc457f6)

My class would cease to exist at the end of that school year. The mainstreaming law with its edict that every handicapped child should be placed in the least restrictive alternative was the primary cause. Most of the special education classes were being closed and teachers like myself were being redeployed as “resource people” to provide support to the regular classroom teachers, who would now have special education children among their students.

I wasn’t terribly comfortable with this change. While I would have liked to accept the law on the ideological grounds it was being put forth on—that it would promote greater equality and opportunity for handicapped children—I was too much of a natural cynic. The far more obvious factor to me was that it was a cheaper way to educate handicapped children.

On a personal level, my style of teaching was best suited to the closed environment of a self-contained classroom. It was in this setting I was at my best. I could create the tight-knit, supportive milieu that became my trademark and it was under these circumstances I could encourage the most positive growth among my students. Consequently, I was loath to become a floating resource person with my children reduced to a catalog of educational problems I was given twenty minutes a week to sort out. Most difficult, however, was being boxed in theoretically. I was an eclectic, picking and choosing my methods of operation from a wide variety of sources, some of them entirely outside education. This seemed the only sensible approach when dealing with such varied difficulties as one comes across in human behavior. However, with the new law we were going to be restricted, generally to some form of behavior modification. I was competent enough with this approach but felt it vastly overrated as a method and rather dangerous as a theory. Thus, not feeling that I was ready to commit myself to all of this, I applied and was accepted at an out-of-state university to do further graduate work.

It was May and school would end the first week in June. In the four and a half months Sheila had been with us, she had metamorphosed into a lively, sunny-natured girl. We had had no serious breaches of behavior since that week in February when I had gone to the conference, and while she was still capable of a hearty tantrum when provoked, normal methods of discipline brought her back into line. She could now express anger without destructiveness; she could be reasoned with; and she could even accept a small amount of gentle criticism without falling to pieces. In short, I didn’t feel Sheila would need a special class any longer. She was still fragile and the placement would need to be well thought out, but I was convinced she had the capacity to get on in a normal classroom.

I had a good friend, Sandy McGuire, a third-grade teacher in another school who I felt would be an ideal next teacher for Sheila. She was young, innovative and had a reputation for sensitivity toward her students, many of whom came from minority backgrounds or extreme poverty. And while we had quite different styles of teaching, we shared similar philosophies. I felt confident that if Sheila went with her, she would receive the support and encouragement she would need to make the transition back into the mainstream.

In the beginning, Ed, the director of special education, was not in favor of this, as it would mean not only releasing Sheila back into regular education, but also advancing her a grade, a practice he frowned upon; however, after much discussion we mutually concluded this was the best choice. Academically, Sheila was at least two grades above her chronological peers and she had no current peer friendships to disrupt anyway. Moreover, I feared that if Sheila did not receive a certain amount of academic challenge, she would get herself into trouble just to stay occupied. The most important factor, however, remained the teacher. Sheila had to have a flexible, supportive teacher to cope with the transition from me and my room to a new setting and I held tight to my belief that Sandy best fulfilled this capacity. In the end, Ed and the placement team agreed.

Sheila didn’t.

I approached the whole issue cautiously, although not tentatively, as Sheila would home in on anything done with uncertainty. Moreover, there was nothing to be tentative about. June was coming and that was the end.

Tears, anger and great silences met my early efforts to broach the subject. We spent the better half of a week dancing nervously around the matter, once it had been raised.

“This here be my class,” Sheila muttered to me after school. Her peculiar usage of the word “be” had almost disappeared over the months since she had been in our room, but now it came back. “I ain’t going in no other class. This here be mine.”

“Yes, it is, but the school year will be over in a few weeks’ time. We need to think about next year.”

“I’m gonna be in here next year.”

My heart sank. “No, sweetie.”

“I am too!” she shouted. “I’ll be the baddest kid in the whole world. Then they won’t let you make me go away!”

“Oh, Sheil. Oh, sweetheart, that’s not what’s happening. I’m not kicking you out. I’d love to have you with me.”

She remained angry, her face flushed, her eyes hurt. She pressed her hands over her ears.

“This class isn’t going to be here next year,” I said softly.

She heard me, even through her hands. The color drained from her face. “What d’you mean? Where’s it going?”

“It’s a grown-up decision. The school district decided they don’t need it and everyone can go into other classes.”

Tears filled her eyes. Taking out the chair across the table from me, she slumped into it, folded her arms on the table and lay her head on it. The tears just fell. Her pain was palpable. I’m sure I could have touched it, had I reached out, and when I didn’t, it pressed in against me.

All I could think of at just that moment was how much we expected from her in terms of tolerance, acceptance and understanding, and here she was, only six. Six, for God’s sake, not even seven until July.

What had I gotten her into? There I was with all my ideologies on commitment and how it was better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. But did she think that? Had I ever given her a choice?

On the other hand, what choice was there? To have done what I did, or to have left her as she was and simply counted off the days until they would come for her? There hadn’t been many alternatives. Watching her as she wept, I did not know if even with so few alternatives I had chosen the right one.

Sheila rose from the table and went to bury herself among the pillows in the reading corner. I remained at the table, listening to her as she cried. At last, I rose and went over.

“How come you ain’t staying to make me good?” she asked me, her voice confused.

“Because it isn’t me who makes you good. It’s you. I’m here to let you know that someone cares if you’re good or not. And in that way, I’ll never leave you, because I’ll always care.”

“You’re just like my mama,” she said.

“No, I’m not, Sheil.”

“You’re gonna leave me, just like her.”

“No, Sheila, this is different.”

“She never loved me really,” she said softly, matter-of-factly. “She loved my brother better than me. She left me on the highway like some dog, like I didn’t even belong to her.”

“I’m not her. I don’t know what her reasons were for what she did, but this is different, Sheila. I’m a teacher. My ending comes in June. But I’ll still love you. I won’t be your teacher any longer, but I’ll still be your friend.”

“I don’t wanna be friends. I wanna be in this class.”

I reached over to her. “I know you do, sweetheart. I do too. I wish it could go on forever.”

She pulled away. “You’re bad as my mama.”

“This is different.”

“It don’t feel any different to me.”

They were an emotional few weeks, those last ones. Sheila was in tears as often as not. Not angry tears, though, just tears, popping up at the most unexpected moments: while we were baking cookies on Wednesday afternoon, while giving water to our cantankerous rabbit, while reading on her own in the book corner. I felt they were a natural part of the separation process, so I accepted them, giving her what comfort she sought and otherwise letting her come to terms at her own pace. And tears were by no means her only expression. There were plenty of boisterous, happy moments too.

I took her over to visit Sandy and her classroom and then we arranged for Sheila to go spend a trial day there. As I suspected would happen, Sheila was seduced by Sandy’s warm, cheerful personality and by the more stimulating environment of the third-grade classroom. These children were actively learning, busy with intriguing projects and undertakings, many of them self-generated. All in all, quite a different atmosphere from our classroom, where going to the toilet was considered an achievement. Sheila came back vibrant from her visit, her conversation full of “Next year, when I’m in Miss McGuire’s class …” I knew then I had been outgrown.

Then the last day.

We had a picnic in the park to celebrate our year together. All the parents were invited and we brought packed lunches and ice cream and all the trappings for a good day out. Ours was an extraordinarily beautiful municipal park with a long, winding lane lined with locust trees, a babbling brook that tumbled down through natural rock cascades to empty into a large duck pond ringed with weeping willows. In all directions there were large expanses of grass stretching out beneath ancient sycamores and oaks.

Sheila loved the park. She had never been there before coming to our room, as it was a long way from the migrant camp; but it was only a few blocks from the school, so I had taken my class over on several occasions. Her father did not come that day, but it was obvious he was making more of an effort with Sheila. She came dressed in a bright-orange cotton sunsuit and excitedly told us how her father had taken her down to the discount store the night before and bought it, especially for her to wear to the picnic. She was so ebullient that day, skipping, dancing, pirouetting in the sunshine, that I still call to mind that bobbing form of sunlit orange every time I smell locust blossoms or see duck ponds.

And then, finally, the end—the last good-bye at the door of the classroom to Anton, the last walk together over to the high school to meet her bus. I had given her the now dog-eared copy of The Little Prince to take with her, a tangible reminder of these last five months, and she clutched it to her as we walked.

Running up the bus steps, she went straight to the back and clambered up on the bench seat to wave to me from the back window. The bus rumbled to life and diesel fumes overpowered the scent of locust blossoms. “Bye,” she was saying, although I couldn’t hear her because of the glass and the noise of the engine. The bus began to pull away and she waved frantically.

“Bye-bye,” I said and lifted my hand to wave too, as the bus turned the corner and disappeared from sight. Then I turned to walk back to my classroom.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_720fca6c-3acc-5c75-bfeb-be23fd4a92e3)

When autumn came, I was a thousand miles away from the school, the migrant camp and the locust trees. Settled into graduate school, I was devoting most of my spare time to research. Some years earlier I had become intrigued by psychologically based language problems, elective mutism in particular, where an individual can speak but does not do so for emotional reasons; however, I had had to put this on the back burner while teaching full-time, because there just hadn’t been time to pursue it. Now I was able to devote the kind of attention to the work I wanted. As a consequence, I was still in daily contact with children, but it was of a different kind and quality to what the classroom had given me. This was okay. I had been ready for the change, and thus was finding this new work rewarding.

Chad and I had parted ways over the summer. We’d been together for much of the previous three years and the last year, in particular, we’d grown close. Sheila, in her own way, had brought us closer still. Previously, Chad had only been part of my personal life, a world I tended to keep strictly separate from my life in the classroom, but with Sheila’s hearing in March, he had been drawn into that too. The magic of that night when Chad had taken Sheila and me out for pizza had been powerful and all three of us, I think, got caught up in a dreamy moment of believing we were a family. It’d seemed so right just then—Chad, Sheila and I; however, in the cold, hard light of day, I knew it wasn’t right. Chad was older than I was and had sown his wild oats, but I was still very young. I knew I was not yet ready for the commitments that a closer relationship with Chad would entail. Because commitments were so important to me, I wouldn’t make them lightly. So, seductive as the vision of family life was at that point, I knew I would fail at it if I tried it now. So this, too, lay behind my decision to change tracks and move away from the area. I loved Chad and I didn’t want to break up our relationship, but I didn’t want to intensify it either. Putting distance between us seemed a reasonable solution.

Chad, of course, figured out what I was doing and he wasn’t particularly happy about it. For him the time was right to settle down and get married. If anything, those last eight weeks with Sheila had verified for him that this was what he wanted and he chafed at my uncertainty, angry with me one moment for my immaturity, poignantly vulnerable the next, when he bemoaned the unfairness of the fact that no matter how much a man might be ready to be a father, he couldn’t be one without a woman. I felt awful, as one always does when relationships crumble, but I went ahead with my plans regardless, knowing in my heart even more certainly that this was the right thing to do.

Sheila went into Sandy McGuire’s third-grade class, and for all intents and purposes, she did extremely well. Sandy kept me well informed with letters each month or so. I was gratified to hear that Sheila was settling in, making friends and achieving good academic results, and even more so to hear that she was coming to school cleaner and better fed, which made me hope the home situation was improving.

My only other source of information was Anton, who still lived in the migrant camp himself and occasionally saw Sheila there. Despite my misgivings when Anton had first come to my classroom the previous autumn, he had turned out to be a natural teacher. He had tremendous rapport, particularly with the slower children and with the Spanish-speakers, of whom there were many in our migrant population. As a consequence, he had decided to work on his teacher qualifications at the nearby community college while still continuing as an aide in the school district. He was well informed on how all my former students were doing, and thus, a letter from Anton was a real treat.

I wrote to Sheila, as I had promised her I would do, and Sheila occasionally wrote back. She was, however, only seven, and as with all seven-year-olds, no matter how gifted, letters were clearly a chore. They came erratically and if I had not had Sandy’s letters in the interim, I really wouldn’t have had any idea of what was going on. Indeed, the contents of Sheila’s letters were even more erratic than their number. She was given to sending me her homework for some reason and that was all I sometimes received for months on end.

All went smoothly. Sheila finished her year with Sandy an enthusiastic, if somewhat quirky, student, and was promoted to the fourth grade. I received a school picture of her from Sandy, showing her in a bright-yellow dress, her smile sweet and toothless. She looked well, if not too clean.

Autumn came but Sheila didn’t. I received a puzzled note from Sandy saying that Sheila had been withdrawn from the register. It was Anton who investigated the matter and wrote back to tell me that Sheila and her father had moved to a small city on the far side of the state, some two hundred miles away. They had left in June, just after school had let out, apparently because her father thought he had found a job.

I wrote to the only address I had, her old one, and received no answer. Distressed at the thought that I had actually lost contact with Sheila, I made a few phone calls in an effort to trace her. During the course of these, I discovered that she had apparently gone into foster care at the end of the summer, but it was only a rumor and I couldn’t confirm it. I knew no one in this new city to which she and her father had moved and I was twelve hundred miles away. It proved impossible to find out where she was and how she was doing.

This upset me profoundly. Confiding in an older colleague one afternoon after an abortive effort to trace Sheila, I was reassured that this was better, that I shouldn’t try to hold on to old students. She smiled gently and patted my shoulder. “Never look back. You’ve got to love them and leave them.”

It was three years before I managed to go back to Marysville to visit my old friends. By then Anton was gone. He had completed his two-year course at the community college and won a scholarship to the state university to finish his bachelor’s degree. I visited with Sandy, however, and Whitney, who was now a senior in high school; and I went back to walk through my old classroom, now converted into a resource center.

Chad and I had separated amicably and we’d stayed in touch. He was married now to a fellow lawyer named Lisa and she was expecting their first child in a month’s time.

We decided to lunch together and I came up to his law office to meet him. He had been held up in a meeting, so I paced languidly about the reception desk waiting for him. It was then I noticed a paper lying in the outgoing basket. I just caught it with the corner of my eye, but the name pulled me back. It was Sheila’s father’s name. Glancing at the receptionist, I realized I couldn’t really look, but I was desperate to hear what Chad had to say.

“Didn’t you know he’s back in prison?” Chad replied to my query.

“No. When did this happen? You never told me.”

“Well, I couldn’t really, could I?” he said apologetically. “I mean, confidentiality and all. Besides, I assumed you did know.” What he didn’t mention was that we had never exchanged much more than Christmas cards anyway since we’d parted. But still, I felt somehow cheated.

Chad smiled gently. “I’m not handling many legal aid cases these days, so I didn’t know myself until I saw the folder.”

“What’s happened?”

“I can’t really discuss it, Torey.”

“I’m not just anybody, Chad. I was the one who brought him to you in the first place.” I was feeling hurt and heartsick. I knew it was hardly Chad’s fault and I fully understood his need to keep confidence with clients, but the shock made me irritable.

“Well, suffice it to say he’s been wholly predictable. He’s up for the same tricks as always.”

“Where’s Sheila then?”

“Don’t know. He’s been living over in Broadview for a couple of years now and he was arrested and booked over there. They sent over here just looking for files. I’ve never seen him or anything.”

“But where’s Sheila?” I murmured, lowering my head.

Heartbroken at this discovery, I endeavored to find out about Sheila’s fate, but I had few resources at my fingertips. Broadview was still two hundred miles off and was a much bigger city. Finding one small girl was no easy matter. The most I could confirm was that she had been taken into foster care as a direct result of her father’s arrest and imprisonment and was, apparently, still placed. Where, with whom and for how long I could not determine. Rumor had it that she had been repeatedly in and out of foster care from the time they had moved.

Foster care. Practically the whole time Sheila was in my class, all of us had viewed foster care as a panacea to her problems. If only Sheila were away from the poverty, if only she were in a stable home with loving parents, if only … We hadn’t been able to get her into foster care then simply because the Social Services were so overstretched in Marysville and she did have her natural father. Now she was in foster care and I should have felt glad. The fact was, I didn’t.

Back home, I sat down and wrote a very long letter to Sheila. I told her about my visit to our old school and our old friends. I mentioned that I knew her life had been disrupted in the last eighteen months and that I knew she was now with foster parents. I said that I hoped all was well and that if there was any way I could help, I would be happy to try. Including my phone number, I said she could call me collect any time, if she wanted. Then I added a photograph from the visit of Sandy and me and an old one I had taken of Sheila on our last-day picnic. Folding everything together, I put them in a large envelope. But where would I send it? In the end, I sent it to her father, in care of the prison, and asked him to forward it to her.

I never heard whether Sheila received my letter or not, whether she ever knew that I was trying to find her again. There was no answer, and as the months went by, I began to accept there wasn’t going to be one.

This was difficult for me to come to terms with. It seemed inconceivable to me that she had disappeared from my life. Yet the words of my colleague kept returning to me: you’ve got to love ’em and leave ’em.

Two years later, a small envelope arrived on my desk. It was addressed not to my home, but rather to the university where I now taught. I recognized Sheila’s loose, scrawly handwriting immediately and tore the envelope open. There was only one sheet of paper inside, a crumpled piece of lined notebook paper. The writing was done in blue felt-tip marker with many of the words watermarked, as if the paper had gotten splattered by rain. Or was it tears?

To Torey with much Love

All the rest came

They tried to make me laugh

They played their games with me

Some games for fun and some for keeps

And then they went away

Leaving me in the ruins of games

Not knowing which were for keeps and

Which were for fun and

Leaving me alone with the echoes of

Laughter that was not mine.

Then you came

With your funny way of being

Not quite human

And you made me cry

And you didn’t seem to care if I did

You just said the games are over

And waited

Until all my tears turned into

Joy.

There was nothing else, no letter, not even a note. As with the days when she had sent me only her homework, Sheila seemed to feel no need for explanations. It was my turn to cry then and so I wept.

Part 2 (#ulink_5399879b-309a-557f-aa9c-7bad456bb41b)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_cf32ace3-2d19-5157-9aa6-20564ba9c94d)

I can remember the moment precisely when the magic began. I was eight, a not-very-outstanding third grader in Mrs. Webb’s class. I didn’t care much for school. I never had. My world in those days was the broad, swampy creek that ran below our house; that and my beloved pets. School was something that got in the way of my enjoyment of these things.

On one particular morning, my reading group had been sent back to our desks to do our seatwork, while Mrs. Webb listened to the next group read. On my desk, under my workbook, I had hidden a piece of paper, and instead of doing what I should have been doing, I sneaked the opportunity to write. At home I had a dachshund, which had been a present to me from my mother on my seventh birthday, and I made him the hero of a rather lurid tale involving our old mother cat and a band of marauding, eye-plucking crows. So absorbed did I become in spinning this tale that I failed to notice Mrs. Webb on the move, and what inevitably happens to eight-year-old girls who do not do their reading workbooks happened. Mrs. Webb snatched the story away from me and I had to stay in from recess to do my work.

The incident itself was minor, the sort of thing to which I was unfortunately rather prone, and as a consequence, I forgot all about it. Then, a couple of weeks later, I was ill and kept out of school for a few days. When I returned, I had to stay after school that afternoon to make up some of the work I had missed. Mrs. Webb apparently took this opportunity to clean out the drawers of her desk. Anyway, when I had finished, she handed over a piece of paper to me. “Here, I think this is yours,” she said. It was the story about my dog and the crows.

Collecting my coat and belongings to go home, I began to read it as I walked down the school corridor, dark and silent because all the other children had left so long before me. Once at the end of the hall, I pushed open the heavy double doors of the school and then sat down on the concrete steps at the entrance to finish reading.

That precise moment I remember with such exquisite clarity—the feel of the cold concrete through my skirt, the late-autumn sunshine transposed against the darkness of the school entranceway, the uncanny silence of the empty playground, even the faint anxiety of knowing that I should be on my way home because my grandmother would worry if I was too late. The paper, however, held me spellbound.

It was all there: my dog, his adventure, the excitement such melodramatic experiences always created in me. I felt just as excited by the story reading it as I had been writing it. Astonished when I realized this, I lowered the paper. I remember lowering the paper, looking over the top of it, seeing someone’s hopscotch game chalked onto the playground asphalt, and being overwhelmed by a sense of insight. Wow! I had always written because I found writing like pretending: an opportunity to turn myself into someone else for the moment I was doing it and be that individual, feeling his or her feelings and experiencing his or her adventures; but once the act of creation was over, I had never really gone back to what I had written. Now here it was, two weeks later, and I was feeling exactly what I had experienced earlier when I was writing it. Exactly. Again. As if the two weeks hadn’t happened. I had stopped time. There, on the school steps, I knew I had stumbled onto magic of the first order. Real magic!

For the rest of my childhood, through my adolescence and into adulthood, writing compelled me. It was an internal, almost autonomic, activity, like circulation or digestion, that happened simply as a natural part of me. I wrote in all forms: diaries, anecdotes, stories. I wrote to understand other people, to give myself the opportunity to be inside them a while and see what it felt like to see the world from another point of view. I wrote to understand emotions and experiences I had not yet encountered. And I wrote to understand myself.

It proved a powerful, if somewhat unusual, education. In particular, it fostered my abilities to be objective and to empathize, which in turn allowed me a greater general acceptance of differences; and, of course, it made me a keen observer.

I was in the final year of a doctorate I hadn’t meant to find myself doing. I had weathered the mainstreaming law that had so disconcerted me the year I’d had Sheila. Although still not happy with all aspects of its implementation, I’d returned to the classroom a couple of years later and taken up teaching again as a “centered” resource teacher, which meant I stayed in the same room but the children came and went. It wasn’t quite as fulfilling as having my own class, but at least I saw the same boys and girls on a regular basis.

Then the administration in Washington changed and with it, the general attitude of the country. Issues I’d fought heart and soul to see achieved a decade earlier were swept away with a single signature. Lower taxes and cuts in public spending became the bywords of the day. Because treating handicapped children in the public schools is labor intensive, and thus expensive, ours were among the first programs to be targeted. Further emphasis was put on placing special education children in the regular classroom as the cheaper alternative. We were being forced to respond to children in ways that were not necessarily the most beneficial to the child—or the teacher, either, for that matter, as many regular education teachers had little grounding in dealing with handicapped children. These philosophies, however, were the only ones that allowed us to process children through the system at the cost demanded of us by the government. The market economy was now being applied to education.

Angry at this change and all too aware that if I continued in the classroom, I too would soon find myself unemployed, I’d decided to work on a doctorate in special education. This was a stupid decision. The degree would overqualify me for the only part of the special education hierarchy I genuinely loved: teaching. Worse, it threw me into the hotbed of those creating the theories that I was trying to escape. Consequently, my heart was never in it.

I coped by finding other outlets. In this case, it was the continuation of my long-standing research into psychological language problems. This work was of little interest to my colleagues in special education; however, I soon found a niche across campus in the university hospital complex. There, in the department of child and adolescent psychiatry, among others, I discovered willing partners among the psychiatrists and other professionals. Despite my hybrid credentials, my ideas were accepted and encouraged and my research flourished.

As always, I continued to fill my spare time with writing. Indeed, I was writing more then than at any previous time; in part, I suspect, because I wasn’t fully engaged in my work.

The desire to write about my experiences with Sheila had been with me for some time. I had saved a lot of material from that class, not with the intention of using it to back up writing at a later date, but just because I was a bit of a hoarder and a sentimental one at that. Although I hadn’t kept a daily diary while working in the class, I had kept copious anecdotal records; moreover, I had had liberal use of a video camera, and as a consequence, had quite a lot of Sheila on tape. I went through these things periodically, and all the while I could hear Sheila in my head: the inflections in her voice, the strange lilting grammatical constructions. I had to write it down. I had to liberate those five months from the onward rush of time.

Then, driving home on the freeway from work one dark January evening, the beginning came to me: I should have known. I went home and started writing. Eight days and 225 pages later, I was finished.

It was only in the aftermath that I realized what had happened. At 225 pages, this wasn’t a little something done for my own amusement, it was a book. I knew then that I had to find Sheila and let her read it before the matter went any further.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_f6095246-3818-5ef9-badf-ac324006755c)

The job advertisement that caught my eye was for a small private psychiatric clinic in a major city about four hours’ drive west of Marysville. In all my years back east, I had missed the Midwest. Admittedly, Sheila also crossed my mind. Broadview, where she had last been living, was a satellite community of the city. Six months had elapsed since I had written the book and I was no closer to finding Sheila. The idea of living near her, of perhaps reestablishing contact and renewing our relationship was appealing.