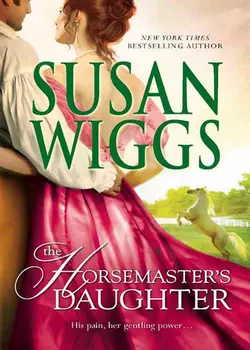

The Horsemaster′s Daughter

Сьюзен Виггс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 305.03 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An unbroken horse, a broken man, an estate that needed herOnce a privileged son of the South, Hunter Calhoun now stands a widower shadowed by the scandal of his wife′s death. Burying himself in his success with breeding Thoroughbred racehorses, he′s left his family to crumble and forgotten how to comfort his grieving children.When a prized stallion arrives from Ireland crazed and unridable, Hunter is forced to seek help for the beast. Removed from the world of wealth and social privilege, Eliza Fylte has inherited her father′s famed gift for gentling horses. And when Hunter arrives with his wild steed, her healing spirit reaches further yet, drawing her to his shattered family and to the intense, bitter man who needs her, just as she needs him.Eliza understands what Hunter refuses to see–that love is the greatest healer of all. But can her kind, humble being manage to teach such an untethered man what truly matters in life?