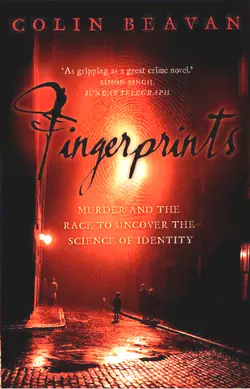

Fingerprints: Murder and the Race to Uncover the Science of Identity

Colin Beavan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежная образовательная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: This edition does not include illustrations.A fascinating exploration into the history of science and crime. In the tradition of ‘Fermat’s Last Theorem’, FINGERPRINTS is the story of the race to discover the secrets trapped in the whorls and arches found on the palm of one’s hand.In 1905 an elderly couple were found murdered in their shop in Deptford, London. The only evidence at the scene of the crime was a sweaty fingerprint on a cashbox. Was it possible that a single fingerprint could be enough to lead to a conviction? Could the pattern of these tracks hold the secrets of the science of identification?Through the story of three brilliant men: William Herschel, a colonial administrator in Indian, Henry Faulds, a missionary in Japan and Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, the extraordinary story of the history of fingerprinting is revealed.It is a story of intellectual skulduggery and scientific brilliance. Packed with an extraordinary cast of individuals whose scientific breakthroughs helped solve one of the most brutal murders in English history and shape our understanding of identity forever.