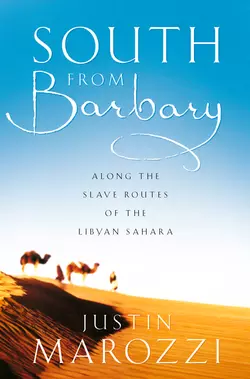

South from Barbary: Along the Slave Routes of the Libyan Sahara

Justin Marozzi

The stunning debut of a talented young travel writer.‘South from Barbary’ – as 19th-century Europeans knew North Africa – is the compelling account of Justin Marozzi’s 1,500-mile journey by camel along the slave-trade routes of the Libyan Sahara.Marozzi and his travelling companion Ned had never travelled in the desert, nor had they ridden camels before embarking on this expedition. Encouraged by a series of idiosyncratic Tuareg and Tubbu guides, they learnt the full range of desert survival skills, including how to master their five faithful camels.The caravan of two explorers, five camels with distinctive personalities and their guides undertook a gruelling journey across some of the most inhospitable territory on earth. Despite threats from Libyan officialdom and the ancient, natural hardships of the desert, Marozzi and Ned found themselves growing ever closer to the land and its people.More than a travelogue, ‘South from Barbary’ is a fascinating history of Saharan exploration and efforts by early British explorers to suppress the African slave trade. It evokes the poetry and solitude of the desert, the companionship of man and beast, the plight of a benighted nation, and the humour and generosity of its resilient people.Written with infectious wit and insight, and a terrific historical grasp, this is a superbly readable travel book about a rarely visited but enthralling and immensely beautiful region of the world.

SOUTH FROM BARBARY

Along the Slave Routes ofthe Libyan Sahara

JUSTIN MAROZZI

Dedication (#ulink_74b4c07a-af7c-528b-b391-1b5dcb33ad16)

To Julia

Epigraph (#ulink_d630bcaa-4d51-5542-b211-556423b581e1)

The hour is nigh; the waning queen walks forth to rule the later night,Crowned with the sparkle of a star, and throned on orb of ashen light:The wolf-tail sweeps the paling East to leave a deeper gloom behind.And dawn uprears her shining head, sighing with semblance of a wind:

The highlands catch yon Orient gleam, while purpling still the lowlands lie;And pearly mists, the morning-pride, soar incense-like to greet the sky.The horses neigh, the camels groan, the torches gleam, the cressets flare;The town of canvas falls, and man with din and dint invadeth air …

Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but self expect applause,He noblest lives and noblest dies who makes and keeps his self-made laws.All other life is living death, a world where none but phantoms dwell,A breath, a wind, a sound, a voice, a tinkling of the camel-bell …

Wend not thy way with brow serene, fear not thy humble tale to tell:–The whispers of the Desert-wind, the tinkling of the camel’s bell.

THE KASÎDAH OF HÂJÎ ABDÛ AL-YAZDI

SIR RICHARD BURTON

Contents

COVER (#ucfd755ea-8e60-575b-847a-73988a3c4795)

TITLE PAGE (#ua14b657e-a992-5d27-8219-cbce666f4cb4)

DEDICATION (#u33564800-9dce-5017-bd56-7f7359af3ba8)

EPIGRAPH (#uf5a5f6b3-2d10-50e5-b449-0c1485e2ed23)

CHAPTER I: Desert Fever (#u78deef9f-79ae-50fe-83f4-65b8e3abdb59)

CHAPTER II: Bride of the Sea (#u99f80be1-7ddb-5961-832d-75f2c8ecb855)

CHAPTER III: ‘Really We Are in Bad Condition’ (#u60ef6826-37fe-51da-b47c-5ddd12db17fc)

CHAPTER IV: The Journey Begins (#u94a8f297-330b-5c29-978a-037b4073be40)

CHAPTER V: Onwards with Salek (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER VI: Christmas in Germa (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER VII: Murzuk (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER VIII: The Hunt for Mohammed Othman (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER IX: Tuna Joins the Caravan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER X: Wau an Namus (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XI: Hamlet in Tizirbu (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XII: Drama in the Dunes (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XIII: Buzeima (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XIV: Hotel Arrest in Kufra (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER XV: ‘Now You Are in Good Condition’ (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER I (#ulink_8c5f151d-b86f-50a4-91b6-11b2faa5e01e)

Desert Fever (#ulink_8c5f151d-b86f-50a4-91b6-11b2faa5e01e)

‘Basically, you’re going to be bloody cold.’

ANTHONY CAZALET

‘Help me with this camel,’ said Abd al Wahab, while Ned and I were busily applying Elizabeth Arden Visible Difference Eight Hour Cream to our faces. Abd al Wahab, our guide, understood camels. They were part of his world. Moisturizer was not. Hastily we packed it away, put the finishing touches to the last camel load, and marched off into the desert. We were under way.

For six years I had longed to make the journey we were now beginning. In a way I owed it to my father, for it was he who had taken me to Libya for the first time. Together, in the warmth of February, we had walked through Tripoli as the wind streamed in from the sea; past the forbidding castle, which had seen 1,000 years of wars and intrigues between marauding corsairs, pirates, Spaniards, Italians, Englishmen, Arabs and Turks, and still stared out impassively towards the southern shores of Sicily; through the ancient Suq al Mushir and into an exotic medley of sights, sounds and smells that roused the senses and stirred the imagination. Throngs of prodigiously built matrons haggled ferociously with softly spoken gold- and silversmiths for jewellery they could not afford. Some were still dressed in the same white, sheet-like farrashiyas their forebears had worn hundreds of years before. Others hid behind their gaudy hijabs (Islamic veils) as they sailed through the narrow alleys hunting for perfume. Deeper into the market, beneath a minaret from which the muaddin was calling the faithful to prayer in haunting, ululating cadences, we had found a dilapidated café, its courtyard open to the sky, and taken our places alongside men playing cards and drinking mint tea, hunched protectively over their bubbling shisha pipes stuffed with apple-flavoured tobacco.

My father’s old friend Othman had taken us for a drive around the city in his Peugeot 504, a brave wreck of a car that had somehow survived several decades of neglect. In the squalid port area, men pored over slabs of tuna and disputed prices with the fishermen. One of these, a great hulk of a man, was tenderizing an octopus, throwing it to the ground, picking it up by its tentacles and then hurling it down again and again.

‘We call Tripoli ar Roz al Bahr, the Bride of the Sea,’ Othman told me as we drove past whitewashed houses along the old corniche, watched over by the palm trees that swayed in the coastal breeze. There was something unmistakably forlorn and beautiful about this city, a sense of wistfulness and a largely unspoken resentment. For centuries it had been a thriving commercial metropolis – cosmopolitan, elegant and refined. Now there was nostalgia and regret in the peeling paint of the colonial Turkish and Italian mansions that, one by one, were being targeted for demolition as vainglorious symbols of the white intruders onto African soil. Thirty years of the revolutionary regime had almost brought the city to its knees – cars fell apart, homes crumbled away, roads rotted – and now sanctions held the city in a tight and unforgiving embrace. My father knew Tripoli well. He had got caught up in the 1969 revolution and had met the young Muammar al Gaddafi just as the old order of King Idris was being consigned to oblivion, but for me it was all new and instantly, wildly, romantic.

Before we left, my father took me to one of Tripoli’s few English-language bookshops, where I picked up the book that for the first time thrust the desert before me in all its guises. Here was silence and loneliness, the glory of wide African skies, unbroken plains of sand and rock, loyalty and companionship, adventure, treachery and betrayal. It was an account of the 1818–20 expedition into the Libyan Sahara led by Joseph Ritchie, ‘a gentleman of great science and ability’ – a diplomat, surgeon and friend of Keats – tasked by the British government to reach and chart the River Niger from the north, one of the last remaining puzzles of African exploration. The enormity of his mission was not matched by corresponding resources and eight months after leaving Tripoli disguised as a Muslim convert, the penniless Ritchie had perished from fever in the insalubrious town of Murzuk, leaving his ebullient companion Lt George Francis Lyon to record their adventures for posterity. Back in London, reading his high-spirited tale, I felt the pull of the desert and started to dream of a similar journey by camel.

Like many ideas, it eventually faded away into a distant fantasy. Six years later, I was working in Manila for the Financial Times, when Ned, an old friend from school days, arrived unexpectedly. During lightning trips south to visit the jungle headquarters of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels, and north to go duck shooting with a gun-toting provincial governor, we started discussing a longer expedition. I had spent almost two years in the Philippines and felt it was time to move on. Ned, a Dorset farmer, was feeling equally restless. We had travelled together several times over the years, from Hong Kong to Costa Rica, and knew and got on well enough with each other to attempt a more serious journey. Deep in the tropical jungle of Maguindanao I revived the long-dormant idea of crossing the Libyan Sahara by camel.

Ned would be the ideal companion. Solid and unflappable, with a keen sense of the absurd, he had travelled widely, was always ready for an adventure, and was practical in a way that I was not. Several years before, he had travelled across the Andes on horseback, and so was probably good with knots and would know what to do if a camel fell sick. At least, that was how I saw him. The truth was that neither of us knew the first thing about desert travel, but with some research in London and a reconnaissance trip to Libya much of our ignorance could be put right. The idea appealed to Ned at once. So much so that he wanted to know whether I was really serious about the expedition. I told him I was going with or without him. He said he was coming. Perhaps he felt the same lure of the desert. His great-uncle David Stirling, founder of the SAS, had fought in the Libyan Sahara during the Second World War, taking men like Wilfred Thesiger, the great desert explorer, on daring raids behind enemy lines.

From the jungle we returned to Manila where Joseph Estrada, the flamboyant former movie star, hard-drinking womanizer and self-confessed philanderer, had just been elected president in a landslide vote. The country looked as though it was heading back to the extravagant corruption of the Marcos era. Foreign investors cringed nervously on the sidelines, wondering if the currency would fall through the floor again. One by one, the Marcos cronies were welcomed back into the fold. The stock market was plummeting. Watching the rot set in again was depressing. ‘See you in Libya,’ said Ned at the airport. My boss thought otherwise, but it was time to leave.

Six weeks later I was back in England planning the journey with Ned. Poring over maps of Libya in the Royal Geographical Society, we decided we would retrace the old slave-trade routes into Africa, making our way across the desert in a south-easterly direction by way of Ghadames and Murzuk, two of the three principal slave-trade centres in Libya, to the third, the fabled and inaccessible oasis of Kufra. A brief trip to Libya in September confirmed it would be wisest to start the expedition from Ghadames, an ancient and once prosperous Saharan town 300 miles south-west of Tripoli. Although camels were not as plentiful as they had been 150 years ago, when Ghadames was still a major centre of the slave trade, they would be more easily procured there than in the capital. More importantly, so would a guide who understood, as we did not, the practicalities of desert travel.

From Ghadames we would head south-east, for the most part skirting the wastes of the Awbari Sand Sea, to the small outpost of Idri. Then it would be several days’ hard going across the mountainous dunes to Germa, which several thousand years ago had been the capital of the fearsome Garamantes. This desert warrior race had once held sway over vast swathes of the Sahara between the Nile and the Atlantic and had, until its final defeat, refused to be cowed by the mighty Roman armies sent to subdue it. Next on our route was the central town of Murzuk, where in 1819 the gallant Ritchie, betrayed by avaricious tribesmen, floundering in delirium and beset by agonizing kidney pains, had succumbed to fever. After Murzuk it would be a week’s march or so to the remote settlement of Tmissah, the last town for 350 miles, and from there a bleak journey to Kufra via a handful of tiny oases – Wau al Kabir, Wau an Namus, Tizirbu and Buzeima – that would test our camels’ endurance to its limits. Kufra, the far-flung oasis town that lay on the most easterly, and least old, of the country’s three slave-trade routes, formerly home of the fiercely ascetic Sanusi confraternity, would be our endpoint. One of the most romantic and elusive Saharan oases, it had remained unseen by Western eyes until the late nineteenth century when the pioneering German explorer Gerhard Rohlfs arrived, only to find a hostile reception from xenophobic tribesmen, from whom he narrowly escaped with his life.

The best time to start our journey would be in December, to allow us enough time to cross the desert in the cooler temperatures of winter. If we left much later than that, the weather would make travel unrealistically difficult and dangerous. The next thing to arrange was some language training. The Arabic I had picked up over the years from trips to the Middle East and North Africa would not be sufficient for a long journey in the Libyan desert with guides who do not speak English. I duly enlisted for a course in colloquial Arabic at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Several days later, a small bespectacled man in a thick woollen three-piece suit (tailored in Cairo) greeted me warmly in the SOAS language centre and introduced himself as Mohammed al Mahdi. I had told the school I would be spending several months in Libya and would prefer to learn colloquial Libyan Arabic rather than the more customary and widely spoken Egyptian. Mohammed was my man. An Egyptian who had spent five years in Tripoli in the early seventies teaching Libyan fighter pilots English, he was the only teacher in the school familiar with the dialect. His opening announcement was inauspicious. ‘I felt a complete stranger in Libya for the first ten days,’ he told me. ‘I just couldn’t decipher their dialect. It was like a completely foreign language. I didn’t know what to do.’ This was particularly galling because the little Arabic I knew was Egyptian.

For the next six weeks before our departure for Tripoli I put myself in Mohammed’s hands. I asked him to keep the lessons as relevant as possible. In practice this meant conjuring up hypothetical desert situations and finding the appropriate expression in Arabic. Lessons alternated between translating phrases such as ‘Please help me unload this camel,’ and ‘I am thirsty because I have been in the sun too much today,’ to spontaneous asides from Mohammed on a bewildering range of subjects, some connected with Libya, others concerning the various women he had been chatting up in the coffee room. Sitting across the table from me as I waited for him to conjugate a verb, he would suddenly remove his glasses and look at me with an expression of avuncular sympathy.

‘Do you know how to ride a camel?’ he would ask solemnly. ‘It’s absolutely awful. Be very, very careful.’ He might then return briefly to the verb in hand before interrupting himself again to deliver another piece of advice. For an effete urban Cairene who had hardly set foot in the desert, he was not afraid to venture strong opinions on the Sahara and its people. ‘I am positive you will never have any problems in the desert,’ he declared. ‘It is true the people may lack polish, yes they do, but that does not mean they are dangerous or have evil intentions, so don’t worry at all. You will be 100 per cent protected by the people.’

For those occasions during our travels when things were not proceeding well, Mohammed advised a particular expression. By its direct appeal to the Almighty, the judicious use of ‘Itaq Illeh’ (Fear God) should ensure we were not ripped off or misled by an unscrupulous merchant or guide. We would use it several times on the journey to amusing, if not entirely profitable, effect. One afternoon he suggested the stronger term ‘Enta gazma’ (You are a pair of shoes) to deter any troublemakers, before deciding against it. ‘No, no, no, on second thoughts you must not say this because the response will be fatal. This is considered a very big insult. Please don’t use it. If anyone said that to me I would spring at his throat and kill him.’

While the Arabic lessons proceeded at this relaxed pace, we sought advice from various quarters. First we consulted Anthony Cazalet, an old friend of Ned’s and the rotund veteran of several trans-Saharan expeditions by car. Apart from an apparently inexhaustible supply of smooth Scottish malts, this yielded very little. The sum of his guidance was distilled into the frequently repeated observation: ‘Basically, you’re going to be bloody cold.’ Unfortunately, this did not lead to any practical suggestions about how we might combat such extreme temperatures. Might it be a good idea, we asked, to take down sleeping bags, or wear special fleece jackets? To which the answer was that it really didn’t matter. Whatever we did, whatever equipment we took, we were going to be ‘bloody cold’. This amused him greatly and he appeared to take a perverse delight in telling us how freezing we were going to be. Not knowing at this stage how accurate his forecast was, we thought little more of it, consoling ourselves with the thought that perhaps he felt the cold more than most, although his generous padding suggested otherwise. Besides, he had a certain reputation for travelling in great comfort, if not splendour. On one desert expedition he had shocked his companions by turning up with a deluxe camp-bed and, more eccentrically still, a ‘thunder-box’ – a portable commode. Travelling by camel, such luxuries would be beyond us.

Through the Royal Geographical Society I was put in touch with Brigadier Rupert Harding-Newman, who had been one of the first men to travel in the Libyan desert in the twenties and thirties in heavily modified Model T and Model A Fords. Well into his eighties, he was still straight-backed and sprightly and he and his wife welcomed me into their home outside Inverness with great hospitality. Over a fine chicken pie and claret, he talked with relish about those ground-breaking days of Saharan exploration and showed me an old film of improbably built Fords sliding down mountainous sand dunes before grinding to a halt and having to be dug out and started up again. As the youthful cook, quartermaster and mechanic on those expeditions from Cairo led by the desert explorer Major Ralph Bagnold, he had always taken a supply of ‘fancy biscuits’ to help keep up morale. He and his companions would invariably stop for elevenses and afternoon tea. We might like to do the same, he suggested. It was only later that we learnt such stops were impossible when travelling by camel. Whereas Harding-Newman and team had been racing across sand flats at speeds of up to sixty miles an hour, we would have to be content with the camel’s more leisurely pace of three miles an hour. Making such ponderous progress through the desert, more often than not we could not even afford to stop for lunch. That did not stop us thinking wistfully of the Harding-Newman tea and biscuit breaks.

Our last port of call was to Britain’s greatest living explorer. At eighty-eight, Sir Wilfred Thesiger, the man who had twice crossed the Empty Quarter of Arabia by camel in the late 1940s, was now marooned in a genteel retirement home in the suburbs of Surrey. He was waiting for us by the entrance, impeccably clad in a thirty-year-old three-piece suit. As we walked across to the neighbouring golf club where we were to lunch, he leant heavily on my arm, quietly reminiscing about his times in the desert.

I had been advised not to be too discouraged by this interview with Thesiger. He would almost certainly pooh-pooh the whole idea and dismiss our proposed journey as a meaningless stunt. Fortunately this was quite untrue. He was obviously cheered by our visit and honest about the difficulties we would face in trying to get an expedition like this off the ground. ‘Your trouble will be that people will say why on earth go by camel,’ he said. ‘They’ll say you can do the journey perfectly well in a car. Arab life and tradition has all changed. It used to consist of loyalty to one’s travelling companion, undergoing hardship together and so on. When you had that you could count on them. They wouldn’t know how to do it now. They would think it absurd.’ He stopped himself for an instant. ‘Oh dear, I’m being very depressing I’m afraid.’

He recommended the Royal Geographical Society for maps of Libya, in particular those that had been used by the SAS and Long Range Desert Group in the Second World War. His cold azure blue eyes glowed as he recalled the campaigns in Libya, when he had approached David Stirling to volunteer for action, saying he spoke Arabic and knew how to travel in the desert. He was taken on and subsequently fought with the SAS behind enemy lines where he ‘shot up’ tentfuls of soldiers in enemy camps.

As far as riding camels was concerned, he said it took some time to get used to their strange loping gait. ‘The first day I rode one I found it very hard to get up the next day,’ he said. ‘You swing around a lot when they walk.’ He had once ridden 115 miles in twenty-four hours in what is now the northern Sudanese province of Darfur, and did not know of anyone who had ridden farther in one day. Travelling long distances with a small caravan, however, it would be inadvisable for us to go faster than walking pace. The camels would not be able to sustain it. Besides, with heavy loads, trotting would be a perilous affair that risked throwing off and smashing valuable bidouns of water.

After lunch, we returned to his modest room decorated with a few tokens culled from a long, nomadic life: a walking stick made from a giraffe’s shinbone, a tattered Oriental rug, a black-and-white photograph of Marrakech. Burton, Conrad, Kipling, Sassoon, Buchan and Thesiger on the bookshelves.

On equipment, he was a ruthless minimalist: ‘I wanted to meet the Bedouin on their own terms with no concessions,’ he insisted. For an Old Etonian from Edwardian England, this meant foregoing such staples of travel as tables and chairs. He had travelled barefoot in the desert, armed always with a dagger and a gun. This might be problematic in Gaddafi’s Libya. Radios, as used by Harry St John Philby, the second man ever to cross the Empty Quarter in 1932, were out. ‘When Philby travelled with the Bedouin he liked having a radio to listen to the Lord’s Test Match,’ he growled into his strawberry and vanilla ice cream. ‘To me that would have wrecked the whole thing.’

Back in London we were not having much joy with maps. We needed to get our hands on the Russian Survey maps, the most detailed and accurate maps of the Sahara, which were proving difficult to locate. Stanfords said it might take two months. We needed them in two weeks. Eventually, I tracked down a supplier on the Internet and ordered a set by email. Nothing happened. I telephoned Munich. The German voice on the other end of the telephone said the maps might arrive before we left for Libya but appeared unconcerned about whether they did. In the meantime we had to make do with the US Tactical Pilotage Charts from Stanfords, no doubt helpful if you were flying over the Libyan desert, but curiously short of detail for an expedition travelling by land.

With several days to go before our departure we paid a swift visit to Field & Trek on Baker Street to buy sleeping bags and other equipment. Sleeping bags proved easy. We lay inside threeseason down bags while an assistant enthused about their many features which would make life so comfortable. Choosing walking boots involved a lengthy discourse from him on the merits of Gore-tex versus leather. Ned, easily bored by detail, started to look distracted, as though he wished he were somewhere else. His patience, always finite, was running out.

On to socks, which surely would be straightforward. Before we could pick up a pair, the assistant launched into a glowing recommendation of Coolmax, some sort of high-tech material. Coolmax socks, designed for walking in summer, apparently boasted five special features, such as reinforced heels, ability to wick away moisture from the feet, and so it went on. I wondered what Thesiger would have made of all this. When it came to discussing the best way to filter water, mutiny broke out between the assistant and his more senior colleague. The latter, spotting the chance to talk gadgetry in front of gadget neophytes, had emerged from the farthest recesses of the shop. A peevish argument broke out between them over whether we were better off using iodine treatment or taking a more expensive water filter. Ned had even less interest in this conversation than I had and headed fast upstairs for the exit, past a Field & Trek nylon washing line with four special features.

The next problem was that neither of us knew how to navigate. A Royal Geographical Society publication on desert navigation was explicit on this point. It was imperative that every expedition should include ‘a meticulous, even perfectionist, navigator who worships at the altar of Truth rather than the altar of convenient results’. I had used a compass a long time ago while in the school cadet force. It was not much to go on. Ned was probably more proficient but did not appear to take much interest in the sort of equipment we would need. Sometimes he would telephone and in a curiously detached way make noises about buying a theodolite so we could navigate by the stars, but eventually nothing more was said of it. Perhaps he was waiting for me to find one.

Harding-Newman had shown me the famous Bagnold sun compass, a cleverly designed navigational device that made use of the shadows cast by the sun and was designed to be mounted on the front of a vehicle, but said it would not be of much use to us travelling by camel. Thesiger had surprised us by confessing he had never been able to navigate by the stars and nor did he know how to use a sun compass. My uncle, a retired naval officer, warned us off sextants. The Royal Navy used to run two-week courses teaching men how to use them, he said, and after two weeks they still had only the most basic knowledge of the instruments. We decided on the less romantic, small and inexpensive, battery-powered Global Positioning System devices to back up our compasses. These would pinpoint our location on the globe to within 10 metres or so.

Shortly before we left, the Royal Geographical Society sent me a recent guide on travelling with camels written by Michael Asher, the British desert explorer. It contained plenty of useful advice on how to choose camels, saddles and guides. Asher, a former SAS man, was insistent on fitness. ‘Whatever country you are trekking in, travelling by camel is inevitably going to involve a great deal of walking. Cardio-vascular fitness is therefore the main area to concentrate on in preparing yourself physically for a camel-trek; jogging, long-distance walking, cycling, swimming. Loading camels usually requires a certain amount of lifting so weight training is also appropriate.’

Neither Ned nor I had ever been great fitness aficionados or taken exercise for as long as we could remember. At Ned’s house in Dorset, we were quizzed closely on our preparations by a friend of his. Julian Freeman-Attwood was a mountaineer who announced rather grandly that he only climbed unclimbed peaks. We told him how we planned to get across the desert and he looked at us in amused disbelief. A veteran of many expeditions around the world, he concluded we were thoroughly unprepared.

‘It’s worse than an expedition planned on the back of an envelope,’ he said with authority. ‘You haven’t even got an envelope.’

Two days later we flew to Tunis.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_8a748aa9-c97f-5562-8044-089006fbcc4f)

Bride of the Sea (#ulink_8a748aa9-c97f-5562-8044-089006fbcc4f)

Properly to write the wonderful story of Tripoli, daughter of sea and desert, one must be not only an accomplished historian, a cultivated archaeologist and an expert in ethnology, but profoundly versed in Arabic and the fundamental beliefs and general practices of Mohammedanism, as well as the local customs of that great religion, coloured as it is by differing environment. If one aims to give a clear exposition of this enthralling though tragic coast of northern Africa, he must be a thorough student of political economy, too, with a world outlook on cause and effect in government.

MABEL LOOMIS TODD, TRIPOLI THE MYSTERIOUS

Happy for poor forlorn, dusky, naked Africa, had she never seen the pale visage or met the Satanic brow of the European Christian. Does any man in his senses, who believes in God and Providence, think that the wrongs of Africa will go forever unavenged? … And the time of us Englishmen will come next – our day of infamy! unless we show ourselves worthy of that transcendant position in which Providence has placed us, at the pinnacle of the empires of Earth, as the leaders and champions of universal freedom.

JAMES RICHARDSON, TRAVELS IN THE GREAT DESERT OF SAHARA IN THE YEARS OF 1845 AND 1846

We hired a car in Tunis airport and drove to Jerba, en route to the Libyan border. In 1992, the United Nations imposed sanctions on Libya to bring to heel the alleged culprits of the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, in which 270 people were killed. Since that date, all flights into and out of the country had been prohibited, leaving overland travel from Tunisia or a boat from Malta as the main alternatives to reach Tripoli.

For as long as I was behind the wheel Ned was a difficult passenger. Repeatedly, he told me what a poor driver I was and how unsafe he felt. Coming from a man whose entire driving career seemed to have consisted of writing off one car after another, this was especially irritating. I took exception to his comments and drove even faster. As night fell on us and the road became progressively harder to navigate, Ned’s warnings became ever more insistent. I told him to shut up. Moments later, to my horror, I found I was driving straight towards a head-on collision with an enormous lorry. Ned shouted something furiously, I jerked the wheel to the right, swerved across the road and only narrowly managed to keep the car on four wheels. We skidded violently to a halt and one of the tyres burst. ‘Justin, you’re a complete idiot,’ he said, fuming. I let him drive for the rest of the night.

We slept on Jerba, an island that was, according to the Greek geographer Strabo, ‘regarded as the land of the Lotus-eaters mentioned by Homer; and certain tokens of this are pointed out – both an altar of Odysseus and the fruit itself; for the tree which is called the lotus abounds in the island and its fruit is delightful’. Herodotus also mentions the islanders, ‘who live entirely on the fruit of the lotus-tree. The lotus fruit is about the size of the lentisk berry, and in sweetness resembles the date. The Lotophagi even succeeded in obtaining from it a sort of wine.’

Two hours into our taxi ride to Tripoli the next morning, we joined the languid snake of cars wriggling across the Libyan border. Our bags were searched and I was asked whether I had a camera. I was then led into a cavernous warehouse, derelict save for a rickety table that stood in an inch of dirty water, behind which sat a Libyan customs official. All around him piles of rotting debris emerged from their bed of slime and wafted up a disgusting stench. His temper appeared as foul as his surroundings. He looked me up and down, almost incredulous, as I was, that I should be referred to him for possessing a camera. Other customs officers were inspecting the boots of Mercedes saloons for contraband. I was small beer. Gruffly, he condescended to stamp my passport with the information that I was carrying photographic equipment and waved our car through. Outside, the first of many propaganda portraits of Muammar al Gaddafi welcomed us to the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, or GSPLAJ for short. Sporting a hard hat and shades, he was presiding benignly over a scene of oil wells in the Sahara. The border area was an ugly scattering of buildings and warehouses and the heat was intense, but none of this mattered. We were a step nearer the desert.

Before preparing for the camel journey in Tripoli, we first had to visit the Roman ruins of Sabratha, forty miles west of the capital. With its more august sister city of Leptis Magna, 120 miles to the east, Sabratha is one of the Mediterranean’s great Roman sites. If it had been in Tunisia, the city would have been clogged with tourists. Thanks to Libya’s status as one of the world’s last remaining pariah states, we had the place to ourselves.

Sabratha dates back to Phoenician times, probably between the late fourth and seventh centuries BC, when it was established as an emporium or trading post, but is an essentially Roman creation. Sabratha, Leptis Magna and Oea (as Romans knew Tripoli) together formed the provincia Tripolitania – province of the three cities – created by the Emperor Diocletian in AD 284. All three both grew through commerce with the Garamantes, the great warrior-traders of southern Libya, and through commercial exchange with Rome. Before the Romans set foot in North Africa, the Phoenicians had introduced agriculture to the coastline, encouraging the cultivation of olives, vines and figs. Tripolitania was, above all, a great exporter of olive oil for use in Rome’s baths and oil lamps, if not its kitchens. The Romans considered African olive oil too coarse for their palates.

After olive oil came wild animals, exported in staggering numbers to feed the bloodlust of Rome’s circusgoers. Tens of thousands of elephants, flamingoes, ostriches, lions, and wild boar were shipped to their destruction. Titus marked the inauguration of the Colosseum by dispatching 9,000 animals into the arena to fight the gladiators. Augustus recorded that 3,500 African animals were killed in the twenty-six games he gave to the people, while Trajan had 2,246 large animals slaughtered in one day. On one occasion, Caesar sent 400 lions into the arena to kill or be killed by gladiators, outdone by Pompey, who sent in 600. North Africa’s ‘nursery of wild beasts’, as noted by Strabo, could not take such wholesale decimation and its animal population never recovered.

By contrast with this northern-bound traffic, the desert trade, whose staple products would later include gold, ivory and ostrich feathers, was not yet advanced. ‘Our only intercourse is the trade in the precious stone imported from Ethiopia which we call the carbuncle,’ remarked Pliny in the first century AD. With abundant sources of slaves in both Asia and Europe, the Romans felt little need to tap the Sahara. Negro slaves, besides, could be procured from the North African coast without having to venture farther south.

We walked slowly through the Forum Basilica, where Claudius Maximus, Proconsul of Africa, had acquitted the Latin writer Apuleius of Madura of a fabricated charge of witchcraft in AD 157. Behind us the magnificent theatre, a warm terracotta in the fading afternoon sun, dominated the eastern part of the city. It was built in the late second century at the outset of the Severan dynasty, a time that would prove to be Roman Africa’s finest hour. It is hard to imagine a more romantic or dramatic spot for a theatre: the cool blue sea is visible only yards behind the three-storey scaenae frons that towers 25 metres above the stage. Gracious marble reliefs on the stage front depict the three Muses, the goddess Fortuna, Mercury with the infant Dionysus, the Judgement of Paris, Hercules, and personifications of Rome and Sabratha joining hands alongside soldiers. Intoxicated by his plans to recreate the Roman Empire, Mussolini reinaugurated the theatre in 1937, almost 1,800 years after its birth. Inside, we came across a small family of Libyans from Tripoli, the only other visitors in Sabratha that afternoon. Passing the crumbling mosaics of the seaward baths, unprotected from the elements, we headed to the easternmost part of Sabratha, to the serene Temple of Isis, smoked cigarettes and stared across at the elegant ruins of the city as a lilac sunset flooded across the sea.

Anxious to press on the next morning, we commandeered a taxi to take us the last few miles to Tripoli. Gleaming white, it rose before us, staring out across the Mediterranean as it had done for three millennia since the bold seafaring Phoenicians established a trading post here. For centuries it had been the principal terminus of the slave-trade routes of Tripolitania that penetrated across the Sahara deep into Black Africa. Today, the city steamed under a shocking noon sun, its fierce glare an unforgettable feature of arrival for as long as anyone can remember. ‘When we approached, we were blinded by the brilliant whiteness of the city from which the burning rays of the sun were reflected. I was convinced that rightly is Tripoli called the “White City”,’ wrote the Arab traveller At Tigiani during his visit of 1307–8.

Arriving by boat from Jerba on 17 May 1845 James Richardson, the opinionated British explorer and anti-slave-trade campaigner, part of whose travels in Libya we would be following, thought it massive and imposing. He admired the slender limewashed towers and minarets that rose towards the heavens, dazzling in the shimmering sunlight. But, he went on deflatingly, ‘such is the delusion of all these sea-coast Barbary towns; at a distance and without, beauty and brilliancy, but near and within, filth and wretchedness’.

We checked in at a small hotel in Gargarsh, formerly the American part of town in the more cosmopolitan, pre-revolution times of King Idris. In those days, the streets were lined with foreign restaurants and eating out in Tripoli was a joy. If you were looking for Greek food, you could choose between Zorba, the Akropol in front of the Italian Cathedral, and the Parthenon in the Shooting and Fishing Club. If it was Italian you were after, there was Delfino, Romagna and the Riviera, while Chicken on Wheels, Black Cat and Hollywood Grill catered for the thousands of Americans in town, together with a long list of French, Tunisian and Lebanese restaurants. Now they had all gone, replaced by the occasional hamburger bar and second-rate Libyan pizza outlet. Here in Gargarsh, a rusting miniature Eiffel Tower, which once had marked the hottest nightspot in town and was now home to the local post office, was all that remained of those livelier days.

On the ground floor of the hotel were the offices of a small tourism company owned by a man called Taher Aboulgassim, whom I had met during my visit to Libya the previous September. He was a smooth, straight-talking businessman in his mid-thirties, one of the new generation of Libyan entrepreneurs, who had been intrigued by the plans I had put to him. No-one had attempted anything like this in recent years, he had informed me, but he would do everything in his power to assist us with the purchase of camels, selection of guides and so on. He had another office in his home town of Ghadames, from where we would probably set off into the desert. During the three months that I would be back in England, he would begin preparations on my behalf and would be waiting for us when we got to Tripoli. The initial encounter inspired confidence. Taher looked like a man we could do business with.

The first hint that arranging a camel trek in Libya might be more difficult than anticipated was that there was no sign of him in his office the next morning.

‘Taher no come,’ said Hajer, his Sudanese office assistant. He said it with some satisfaction. In a country where little was certain here was an incontrovertible fact, and he relished it.

‘Where is he?’ I asked.

‘No problem. He will come,’ he replied with the confident air of one who had inside information.

‘What time will he come?’

‘Maybe 12 o’clock. Maybe 5 o’clock,’ came the vague reply.

‘Which one?’

‘He will come.’

Hajer’s hairstyle, an exuberant greying Afro, suggested a man still caught in the giddiness of the seventies. On times and appointments he was consistently casual. He had heard of our plans and, like his boss Taher, heartily approved of them.

‘No-one do anything like this since Second World War,’ he declared. Excitable and warm by nature, he launched into a passionate recommendation that we extend our desert crossing into Sudan. ‘If you are British and you have money, you can do anything in Sudan,’ he promised. ‘We like the British too much.’

I told him Ned was a farmer in England.

‘Then you must invest in Sudan agriculture,’ was the unhesitating reply. ‘You will have a letter from the government and then you can do anything. ANYTHING.’ His eyes grew large with enthusiasm. ‘You want farm? You can buy farm. You want camels? You buy camels. No problem in Sudan. You do ANYTHING you like.’ He spoke in an excited, breathless staccato, a patriotic investment adviser in overdrive. There was no stopping him. ‘Sudan is VERY, VERY rich country. We have EVERYTHING in Sudan.’

For years Sudan had been one of the poorest countries in the world, crushed by civil war, famine and corrupt, xenophobic governments. None of this had dented Hajer’s boundless optimism.

‘You must see it. Not for one month or two months. No,’ he went on emphatically, ‘you must go for nine months.’

‘First we must talk to Taher,’ I said, trying to steer the conversation around to the present.

‘The government will help you too much if you like Sudan agriculture,’ he went on, looking meaningfully at Ned.

‘Perhaps we can discuss this a little later,’ I suggested. ‘But could you tell us where Taher is. He should be expecting us.’

Hajer looked upset. He had not expected to be diverted from his talk on Sudanese agriculture. ‘He will come,’ he said stubbornly.

Taher did not come. We waited several hours and still there was no sign of him.

‘Do you think he’s reliable?’ asked Ned over lunch in a semi-derelict hotel opposite our own. Like most swimming pools in Tripoli, this one was empty and looked as though it had been for years. Ned looked bored. I was, too, but was used to waiting for appointments in Libya.

‘As reliable as you can expect in Libya.’

‘Well, it doesn’t look like he’ll come today. Shall we go to Leptis Magna?’ he went on. We waited another couple of hours and returned to the office.

‘Taher come tomorrow,’ said Hajer, as though he had known this all along.

‘Come on, let’s go,’ said Ned, who had waited long enough.

We called a taxi and drove to the stately ruins of Leptis Magna, Libya’s most imposing Roman city.

Leptis owes its greatness to its most famous son Septimius Severus, the first African Roman emperor. He seized power in AD 193, after the murders of the emperors Commodus and Pertinax in quick succession. Elevated to greatness in Rome, Septimius never lost sight of his African origins and Leptis rose to the height of imperial grandeur, becoming one of the foremost cities of the empire. Architects and sculptors descended in droves from Rome and Asia Minor to create monuments such as the two-storey basilica, overwhelming in its sheer scale, gorgeous in its design, paved with marble and ruthlessly decadent, with soaring colonnades of Corinthian columns embellished with shafts of red Egyptian granite. Up went the Arch of Septimius Severus, built in AD 203 for the emperor’s visit to his birthplace, an immense testimony to Rome’s mighty sway, with marble reliefs detailing triumphal processions, naked winged Victories, captive barbarians and a united imperial family. A new forum was erected, the circus was enlarged and the port rebuilt to accommodate 1,000-ton ships guided into the harbour by a 100-foot lighthouse. Leptis had never known such glory and would never again. When Septimius died campaigning in York in AD 211, the city embarked upon a long decline from which it did not recover. Fifteen centuries later, Louis XIV had many of the city’s treasures exported to Paris.

For the art historian Bernard Berenson, Leptis was unforgettable. ‘We went on to the Baths, the Palestra, and the Nymphaeum,’ he wrote to his wife in 1935. ‘Truly imperial, even in their ruins, for one suspects that ruins suggest sublimities that the completed building may not have attained. In their present state they are evocative and romantic to a degree that it would be hard to exaggerate.’ Today, we wandered along the shore and clambered undisturbed over these neglected buildings, past piles of fallen columns and discarded pedestals lying strewn under the wide African sky. The hot silence of the place was overpowering. Deep in drifts of sand and choked by spreading trees and plants, Septimius’s city slept.

Through his encouragement of camel breeding on the North African littoral, the African emperor had provided a huge fillip to Saharan trade. The merchants of Leptis are thought to have been the first to benefit from the introduction of this animal. The days of the horse, used for centuries to great effect by the formidable Garamantes, were numbered. The camel offered improved performance in the desert, was economical to run, and comfortable to ride. The Romans wasted little time in increasing the numbers of this versatile beast. By AD 363, when Leptis was invaded by the Austurians, a group of tribes from the central region of Sirtica, Count Romanus, commander of Roman troops in Africa, demanded 4,000 camels from the townsmen as his price for intervening on their behalf.

We met Taher in his office the following morning. He appeared taken aback by our arrival, like a burglar caught in the act. Sheepishly he confessed that nothing had been arranged.

‘I thought maybe you would not come to Libya,’ he said feebly.

‘But Taher, I told you exactly when we were going to arrive,’ I replied, exasperated. My previous trip to Libya seemed to have been for nothing.

‘We have too many problems in Libya,’ he said, as though this explained everything.

‘Well, it’s a great start,’ I said, turning to Ned. He was phlegmatic about this first upset to our plans. I should have been, too. Planning anything in advance in Libya was a lost cause. The country didn’t work like that. You had to be there on the ground to get anything done.

‘Now you are here I will go to talk to my friend,’ Taher said more hopefully. ‘Maybe you can buy your camels in Tripoli.’ It seemed unlikely.

We headed into Tripoli’s Old City and threaded our way through Suq al Mushir, the gateway into the medina, to drink tea, smoke apple-flavoured tobacco in shisha pipes, and mull over our situation, which did not seem particularly promising. On the outside of the old British Consulate on Shar’a al Kuwash (Baker Street) was a plaque put up by the Gaddafi regime describing the building’s history. Reflecting the leader’s distrust of western imperialism, it referred to the pioneering nineteenth-century missions into the Sahara that left from here as ‘the so-called European geographical and explorative scientific expeditions to Africa, which were in essence and as a matter of fact intended to be colonial ones to occupy and colonize vital strategic parts of Africa’.

Built in 1744, it served first as a residence for Ahmed Pasha, founder of the great Karamanli dynasty. Turkey had administered Tripoli since 1551, when Simon Pasha overcame a small force of the Knights of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, who until then had been maintaining the city as ‘a Christian oasis in a barbaric desert’. The Karamanlis themselves hailed from the racial mix of Turkish soldiers and administrators who had married native women.

From the second half of the eighteenth century, the building became the British Consulate, from where successive consuls kept London up to date on the Saharan slave trade, various measures to suppress it, and the continued obstruction of such measures by the Turkish authorities. Local officials tended to disregard with impunity Constantinople’s imperial firmans (decrees) and vizirial orders outlawing the trade for the simple reason that they benefited enormously from it. Typical of the correspondence between London and Tripoli was the instruction in 1778 to the British Consul Richard Tully to provide

an account of the Trade in Slaves carried on in the Dominions of the Bey of Tripoli, stating the numbers annually brought into them and sold, distinguishing those that are natives of Asia from those that are natives of Africa, and specifying as far as possible, from what parts of Asia and Africa the slaves so sold in the Dominions of the Bey are brought, and stating whether the male slaves are usually castrated.

Such correspondence makes grim reading. For all the British determination to stamp out this ‘miserable trade’, it continued apace and for more than a century after Tully’s time, consuls would write to London of the Turkish authorities’ ‘apathy and utter indifference’ to the slave trade, their ‘palpable’ neglect and ‘flagrant infraction’ of orders from Constantinople. In 1848, the sultan prohibited the Turkish governor of Tripoli and his civil servants from trading in slaves and in 1856 slave dealing itself was outlawed throughout the Ottoman empire. But in practice, the trade continued, albeit in reduced volume. In 1878, 100 years after the letter to Tully, Frank Drummond-Hay, the British Consul, was telling the Foreign Office that ‘the vigilance required in watching the Slave Trade, in thwarting the devices resorted to by the local authorities in order to evade the execution of the orders for its suppression, in obtaining information on the arrival of slaves by the caravans from the Interior, of intended shipments and other numerous matters in connection with this traffic’ justified a substantial increase in his salary.

On the other side of a massive wooden door was the cool marble floor of an elegant courtyard, decorated with plants, on one side of which a worn flight of steps led up to the ‘general scientific library’ to which the building was now devoted. This was the house in which Miss Tully, sister of the British Consul, composed her fascinating Narrative of a Ten Years’ Residence at Tripoli in Africa between 1783–93. This doughty lady lived through the great plague of 1785 that carried off a quarter of Tripoli’s inhabitants and regularly witnessed slave caravans arriving from the Sahara. One limped into town in the dreadful heat of summer in 1790. ‘We were shocked at the horrible state it arrived in,’ she wrote. ‘For want of water many had died, and others were in so languishing a state, as to expire before any could be administered to save them from the parching thirst occasioned by the heat. The state of the animals was truly shocking; gasping and faint, they could hardly be made to crawl to their several destinations, many dying on their way.’

An intimate of the Pasha of Tripoli’s family, Miss Tully heard eyewitness accounts of the assassination in 1790 of Hassan Bey, his eldest son and heir. Sidi Yousef, the Pasha’s youngest son and pretender to the throne, had been feuding with his elder brother for some time before announcing he was ready for the sake of the family to effect a reconciliation in front of their mother Lilla Halluma.

The Bey replied, ‘with all his heart’ that ‘he was ready’ upon which Sidy Useph rose quickly from his seat, and called loudly for the Koran – the word he had given to his eunuchs for his pistols, two of which were brought and put into his hands; when he instantly discharged one of them at his brother, seated by his mother’s side. The pistol burst, and Lilla Halluma extending her hand to save the Bey, had her fingers shattered by the splinters of it. The ball entered the Bey in the side: he arose, however, and seizing his sabre from the window made a stroke at his brother, but only wounded him slightly in the face; upon which Sidy Useph discharged the second pistol and shot the Bey through the body.

Hassan’s gruesome murder – Miss Tully informs us he was stabbed repeatedly by Sidi Yousef’s black slaves as he lay dying and had eleven balls in him when he perished – plunged Tripoli into chaos. Further assassinations of leading figures followed and the Karamanli dynasty, which had ruled Tripoli since 1711, found itself under siege. Fighting broke out against the neighbouring Misratans and the rapacious Sidi Yousef prepared to attack Tripoli Castle. From its ‘situation and strength’, the British Consulate was regarded as the only safe asylum among the consular houses. Miss Tully braced herself for an invasion: ‘The Greeks, Maltese, Moors and Jews brought all their property to the English house. The French and Venetian consuls also brought their families; every room was filled with beds; and the galleries were used for dining-rooms. The lower part of the building contained the Jewesses and the Moorish women with all their jewels and treasures.’

While the family’s internecine conflict raged, on 29 July 1793 a Turkish adventurer named Ali Burghul – well acquainted with the turmoil – sailed into Tripoli harbour with a fleet of Turkish vessels claiming to have a firman from the Grand Signior to depose the Pasha and assume the throne. The crimson flag with the gold crescent was raised over Tripoli, Turkish guards rampaged through the city and the Tullys fled. After the failure of their initial attempt to repel the usurper, the princes Sidi Yousef and his second brother Sidi Hamet escaped to join their father who had taken refuge with the Bey of Tunis.

By 1795, the father and his two sons had made up their differences and a reunited Karamanli family expelled the Turkish impostor from Tripoli, installing Yousef as the new Pasha. His rule dovetailed neatly with growing British interest in unexplored Africa, born of the desire both to extend commercial relations with the continent and to investigate and suppress the Saharan slave trade. In 1788, in recognition of the fact that ‘the map of the interior of Africa is still but a wide extended blank’, the Society Instituted for the Purpose of Exploring the Interior of Africa (African Society for short) was founded in London. European knowledge of the continent and its peoples had hardly developed since the times of Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny and Ptolemy. Arab writers and travellers of the Middle Ages such as Abu Obeid al Bekri, Ibn Khaldun and Ibn Battuta, the fabled fourteenth-century adventurer who blazed a swathe through the lands of Islam, had forged ahead. In the sixteenth century the Arabs pressed home their advantage, most notably through the travels of Ali Hassan Ibn Mohammed, or Leo Africanus (the African Lion), who crossed the Sahara to Timbuctoo in 1513. It fell to Jonathan Swift to lampoon this lamentable European ignorance.

So Geographers in Afric-Maps

with Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps:

And o’er unhabitable Downs

Place Elephants for want of Towns.

As Pasha of Tripoli, Yousef later gave assurances to the British government that he would, for a princely fee, guarantee safe conduct to any expedition to the River Niger. He held sway over parts of Fezzan, south of Tripoli – the central province to the south of Tripolitania that extended as far west as the borders with modern Algeria and, to the south, as far as the borders with present-day Niger and Chad – and claimed to be on friendly terms with the Sultans of Bornu and Sokoto in the heart of what Britons knew as ‘Negroland’ or ‘Soudan’, from where the caravans dragged their wretched human cargo across the Sahara to the Mediterranean coast. London duly dispatched the adventure-seeking surgeon Joseph Ritchie to Tripoli in 1818. His brief, as ambitious as it was unlikely, was to attempt an exploration from the north across the Sahara, install himself as British Vice-consul in Fezzan and chart the Niger. Like many of his assurances, Yousef’s promise of safe conduct proved worthless – the lands he controlled extended no further south than Ghadames, not, as the British believed, as far as Timbuctoo and Bornu. But what tempted London to launch the Ritchie expedition was the fact that it offered a considerably less expensive alternative to penetrating towards the Niger from the west coast of Africa. An expedition from Sierra Leone had already been devastated by disease and would end up costing Britain £40,000. Ritchie was given £2,000.

Once landed at Tripoli, he and Lyon met the redoubtable British Consul Colonel Hanmer Warrington, who took them to an interview with the Pasha to discuss their journey into the Sahara. Warrington, a brilliant servant of the Empire and a leading figure at the Pasha’s court, would watch British expeditions into the interior come and go during his residency from 1814 to 1846. Such was his influence that to many of his contemporaries, including the French Consul, it appeared that it was he, rather than the Pasha, who was running the country.

It was to the British Consulate once more that a sunburnt and bearded James Richardson headed on arriving in Tripoli in 1845. Sponsored by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, Richardson had volunteered to investigate the Saharan slave trade, which he regarded as ‘the most gigantic system of wickedness the world ever saw’. His initial reception by Warrington was inauspicious. ‘Ah!’ said the British Consul, ‘I don’t believe our government cares one straw about the suppression of the slave-trade, but, Richardson, I believe in you, so let’s be off to my garden.’ Warrington, by now approaching the end of his marathon posting, was as superior as ever in his observations. ‘Whether the extraordinary indolence of the people proceeds from the climate, or want of occupation, I know not,’ the British Consul told the new arrival, ‘but they are in an horizontal position twenty hours out of the twenty-four, sleeping in the open air.’ Richardson and Warrington did not hit it off. With typical acuity, the supremely pragmatic British diplomat recognized Richardson as a loose cannon. ‘I wish again to say your conduct and proceedings require the greatest prudence or you may lose your life or be made a slave of yourself and carried against your will into the Interior,’ Warrington advised him in a letter. ‘Over zeal often defeats the object but I pray for your health and success.’ After waiting interminably and in vain for letters of recommendation, Richardson departed Tripoli for Ghadames ‘without a single regret, having suffered much from several sources of annoyance, including both the Consulate and the Bashaw’.

Fifty years later, it was the turn of Mabel Loomis Todd, an American writer who adored Tripoli, to descend on the British Consulate, this time to observe the eclipses of 1900 and 1905. Around her, excited Tripolitans watched the heavens in awe.

The fine Gurgeh minaret with its two balconies towering above the mosque was filled with white-robed Moslems gazing skyward. As the light failed and grew lifeless and all the visible world seemed drifting into the deathly trance which eclipses always produce, an old muezzin emerged from the topmost vantage point of the minaret, calling, calling the faithful to remember Allah and faint not. Without cessation, for over fifteen minutes he continued his exhortation, in a voice to match the engulfing somberness, weird, insistent, breathless, expectant.

Todd was also one of the few travellers to witness the final moments of the great caravan trade. The large expeditions that for centuries had carried off European arms, textiles and glassware into the desert, were no more, replaced now by much smaller and more infrequent missions into the interior. One morning, after ten months in the desert, a caravan of more than 250 camels was sighted approaching the city. Todd hurried over to watch its entrance:

The camels stepped slowly, heavily laden with huge bales securely tied up – ivory and gold dust, skins and feathers. Wrapped in dingy drapery and carrying guns ten feet long, swarthy Bedouins led the weary camels across the sun-baked square. In the singular and silent company marched a few genuine Tuaregs, black veils strapped lightly over their faces and enshrouded in black or dark brown wraps … In their opinion even the veils were hardly protection against the impious glances of hated Christians, and with attitudes expressive of the utmost repulsion and ferocity they turned aside, lest a glance might be met in passing. All were ragged beyond belief and incredibly dirty.

We left the Consulate and descended a gloomy street to Tripoli’s only Roman ruin, the four-sided triumphal arch dedicated to the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus in AD 163. With innocent disregard for the city’s glorious past, a young boy was urinating on its base. We exited the medina and walked around the fish market next to the port, where mountainous men were hacking tuna into pieces. Behind them rose the ghostly water pipes commemorating Gaddafi’s Great Man Made River, at one time the largest engineering project in the world, designed to bring fresh water up from the desert to the coast via 5,000 kilometres of pipelines. The last time I had been here, this bizarre urban sculpture had been a working fountain. Today, there is no sign of water. It is probably still too early to know whether the project is an act of genius or an ecological catastrophe waiting to happen. Certainly, it had an inauspicious start. When, with great fanfare, Gaddafi turned on the taps in September 1996, as part of the 27th anniversary celebrations of the revolution, half the city’s streets promptly exploded. After decades of corrosion by salty water, the antiquated pipes could not take the pressure. Many of the streets across the capital still lay in rubble, monuments to the leader’s madness.

Looping back into the Old City, we passed through throngs of African immigrants selling fake Nike and Adidas T-shirts, tracksuits and trainers, and drank more tea in a café belting out mournful love songs from Oum Koulthoum, the late queen of Arab music. Opposite us was the elegant Turkish Clock Tower (all of its timepieces stuck at different times, its windowpanes dusty and broken), given to the city in the mid-nineteenth century by its governor Ali Riza Pasha. In Green Square, renamed by Gaddafi as another reminder of his revolution, we went into the Castle Museum. After the open-air glories of Leptis and Sabratha, it was of less interest, except for the top floor, which was given over entirely to Gaddafi propaganda. Photos traced the leader’s development as international statesman from the meeting with his then hero Nasser shortly after the 1969 revolution to later encounters with revolutionaries like Syria’s President Assad and Fidel Castro (the latter being the winner of the 1998 Gaddafi Prize for Human Rights). On the walls were reality-defying slogans from Gaddafi’s Green Book.

‘Representation is a falsification of democracy’

‘Committees everywhere’

‘Arab unity’

‘Forming parties splits societies’

We picked up a copy in a hotel. It was marked 1.5 dinars but the man behind the counter (who thought we were lunatics) let us have it for nothing. Libyans have to live with the grinding follies of their leader on a daily basis. ‘The thinker Muammar Gaddafi does not present his thought for simple amusement or pleasure,’ the dustcover proclaimed. ‘Nor is it for those who regard ideas as puzzles for the entertainment of empty-minded people standing on the margin of life. Gaddafi’s ideas interpret life as it erupts from the heart of the tormented, the oppressed, the deprived and the grief-stricken. It flows from the ever-developing and conflicting reality in search of whatever is best and most beautiful.’ The Green Book rejects both atheistic communism and materialistic capitalism in favour of the Third Universal Theory. Libyans have yet to work out what it all means.

There is an unmistakable whiff, then, of Orwell’s 1984 about Tripoli, an Oceania on the shores of the Mediterranean, a city whose people just about get by. The wonderful climate is deceptive. The first-time visitor sees a handsome, whitewashed city basking in the sun. A refreshing breeze blows along the boulevards lined with palm trees and grand stuccoed buildings from the Turkish and Italian era. In the square to the south of the castle, water dances in the Italian fountain. Here and there are cafés, filled with men smoking shisha pipes, playing chess and backgammon. Women bustle along, window-shopping in the brightly lit gold boutiques. Bride of the Sea and gateway to the desert, Tripoli is an elegant place.

But these are only first impressions. When he looks more closely, the visitor finds that much of this handsome city is falling apart. Even the charm of the medina, with its colonial-era architecture, shaded streets and small, labyrinthine suq is one of decay. Its graceful Turkish and Italian buildings, once the finest homes in the city, are crumbling away. The visitor finds, too, that the men are smoking pipes and playing chess in the cafés because they have no jobs to go to. And the women waddling through the suq are window-shopping because they can only afford the bare necessities.

Nonetheless, children of senior government officials, chic in designer clothes, chat into mobile phones and congregate in the new fast-food outlets springing up around the town. Together with high-ranking military personnel, they hurtle along the roads in black Mercedes and BMW saloons with tinted windows, past less favoured government employees rattling along in ancient Peugeot 404s held together with string, while African immigrants from Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Sudan sit by the roadside, waiting for construction and painting jobs that may never come.

Back at the hotel there was no sign of Taher in his office.

‘It might be a good sign,’ I said to Ned. ‘Perhaps he’s still talking to his friend about buying camels.’ I didn’t really believe a word of it. Ned looked equally unconvinced. Fearing the worst, I checked in with Hajer to see if he could shed some light on Taher’s prolonged disappearance.

‘Taher go to Tunisia,’ he said matter-of-factly. ‘He go to meet new tourists.’

This was testing our patience excessively. It was all very well waiting in the hope of something happening, but Taher was obviously over-stretched and doing nothing on our behalf. There was no point delaying any further in Tripoli. We had to get on with looking for camels ourselves. Hajer looked uncomfortable, as though he feared the worst from his boss should he let us leave during Taher’s absence. He implored us to stay. We shook our heads. He changed tactics.

‘Taher very angry you go Ghadames.’

‘Well, we’re very angry he went off to Tunisia without even telling us,’ I replied.

‘No, you stay in Tripoli,’ said Hajer. ‘Taher go to Tunisia.’

‘We go to Ghadames,’ we responded firmly.

CHAPTER III (#ulink_a456bfd7-d71d-5cdf-afa6-0705e3131e9a)

‘Really We Are in Bad Condition’ (#ulink_a456bfd7-d71d-5cdf-afa6-0705e3131e9a)

Libya is – as the others show, and indeed as Cnaeus Piso, who was once the prefect of that country, told me – like a leopard’s skin; for it is spotted with inhabited places that are surrounded by waterless and desert land. The Egyptians call such inhabited places ‘auases’.

STRABO, THE GEOGRAPHY

The details of the [slave] traffic are really curious. A slave is heard of one day, talked about the next, reflections next day, price fixed next, goods offered next, squabblings next, bargain upset next, new disputes next, goods assorted next, final arrangement next, goods delivered and exchanged next, etc., etc., and the whole of this melancholy exhibition of a wrangling cupidity over the sale of human beings is wound up by the present of a few parched peas, a few Barbary almonds, and a little tobacco being given to the Soudanese merchants, the parties separating with as much self-complacency, as if they had arranged the mercantile affairs of all Africa.

JAMES RICHARDSON, TRAVELS IN THE GREAT DESERT OF SAHARA IN THE YEARS OF 1845 AND 1846

Outside Tripoli, we got out of our taxi and stopped in a roadside restaurant for a hasty supper. The news bulletin was just beginning. Until recently, the opening sequence had showed Libya and the Arab world as a solitary block of green in a black world. In the heavens hung a copy of The Green Book, growing steadily brighter as a ray of light beamed up towards it from Tripoli. Then, like a satellite sending out signals, the book started zapping countries one by one until the whole world had succumbed to Gaddafi’s malevolent genius and turned green itself. All this was until 1998, when invitations were sent to Arab leaders to join the celebrations in Tripoli for the 29th anniversary of the revolution. Not one turned up. Several premiers, including Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, had arrived several days earlier and made a discreet exit before the ceremonies began. Foreign heads of state were limited to a handful of African leaders. Stung by this snub from his Arab brethren, the man who had spent three decades in power campaigning for a single Arab nation, declared that henceforth Libya was an African, not an Arab, nation. The news no longer showed the outline of the Arab nations. Libya beamed out green light to the black continent of Africa instead.

The main item tonight was the meeting in Libya between the All African Students Union, an African president and Gaddafi. The African leader sat in impressively colourful costume, nodding off periodically during a long ranting speech from his host. Flanking the Libyan head of state was Louis Farrakhan, the American Muslim firebrand, who had probably been given a handsome stipend to lend revolutionary Islamic chic to an otherwise tedious function. Dutifully, he praised his Libyan host. ‘We admire your great moral stature in international affairs and your fight against the imperialist policies of colonialism,’ he droned on sycophantically. ‘You are one of Islam’s great revolutionary leaders. We salute you for your work around the world in support of our Muslim brothers.’ The next item reported claims made by the renegade MI5 officer David Shayler that Britain had plotted to assassinate Gaddafi. ‘It was a pity they didn’t kill him,’ muttered a driver on the neighbouring table.

We sank into the seats of our Peugeot taxi and sped through flat, barren country, listening to French rap, soft Arab rock and All Saints. All that broke the emptiness of the evening landscape were occasional car scrapyards, unsightly heaps of abandoned Peugeot hulks next to squat Portakabins, and thick bands of rubbish on the roadside, mostly car tyres, food packets, and empty tins and bottles. And then darkness fell. At three in the morning, we nosed into the black mass of Ghadames and drove to the house of Othman al Hashashe, where I had stayed the last time I was here. Othman, a gangling twenty-six-year-old accountant and devoted Manchester United fan resplendent in Nike leisure suit, rubbed the sleep from his eyes wonderingly, recognized me and let us in. It was a bitterly cold night inside the house, a harbinger of things to come.

Richardson reached this oasis on 24 August 1845, after an uncomfortable two weeks on camel. He had been preceded by a letter announcing him somewhat disingenuously as the ‘English Consul of Ghadames’. Initially, he was ecstatic. By his own account he was only the second European ever to set foot in this holy trading city. Another Briton, Major Alexander Gordon Laing, had passed through twenty years before en route to becoming the first European to reach Timbuctoo, but had been murdered shortly afterwards. Back in 1818, Ritchie and Lyon had intended to travel to this far-flung town but had been discouraged by Yousef Karamanli ‘on account of the alledged dangers of the road’.

‘I now fancied I had discovered a new world, or had seen Timbuctoo, or followed the whole course of the Niger, or had done something very extraordinary,’ Richardson gushed. ‘But the illusion soon vanished, as vanish all the vain hopes and foolish aspirations of man. I found afterwards that I had only made one step, or laid one stone, in raising for myself a monument of fame in the annals of African discovery!’ For the time being, the great mission to investigate and help eradicate the slave trade had been forgotten. Richardson’s personal ambitions as an African explorer were proving more immediately compelling.

I awoke next morning to a familiar booming voice. Mohammed Ali, who had acted as guide and interpreter for me during my last visit, was breakfasting with Othman. I joined them and was instantly bombarded with a barrage of greetings from Mohammed.

‘Mr Justin, kaif halek (how are you)? Fine? Really, I have missed you, believe me. I thought maybe you were not coming to Libya. How are you? Fine? How is your family? Now I am happy to see you, alhamdulillah (praise God). Believe me, I am too shocked now you come to Ghadames. Alleye berrik feik (God bless you). How is your father? How are you? Fine?’ The exchange of greetings lasted some time. Libyans are an exceedingly courteous people. It reminded me of Lyon’s first impressions of Tripolines in 1818, when he observed:

Very intimate acquaintances mutually lift their joined right hand, repeating with the greatest rapidity, ‘How are you? Well, how are you? Thank God, how are you? God bless you, how are you?’ which compliments in a well bred man never last less than ten minutes; and whatever may be the occasion afterwards, it is a mark of great good breeding occasionally to interrupt it, bowing solemnly and asking, ‘How are you?’ though an answer to the question is by no means considered necessary, as he who asks it is perhaps looking another way, and thinking of something else.

Mohammed was small and stodgily built, bordering on the portly, with a hurrying ramshackle gait and a baritone laugh. A man of constant good humour, he had a lazy right eye, so it was often difficult to know if he was addressing you or someone else. On the basis of my brief time in Ghadames the previous September I was now considered an old friend. Throughout our stay in Libya, Mohammed would behave like an old friend too – unstintingly helpful and loyal. Without our asking for assistance, he had taken today off from his job as one of Ghadames’s three air traffic controllers to show us the Old City and help us look for camels. With an average of one incoming flight every month or so, it was not a demanding job. Before the 1992 embargo, there had been three flights a week to Tripoli and two to Sebha, the capital of Fezzan. Mohammed owed his staccato command of English to a nine-month course at the Anglo-Continental Educational Group of Bournemouth. This was our first experience of the Libyan Dorset connection that would resurface bizarrely during our time in the Sahara. Trained at Herne airport in Dorset in 1978, Mohammed was an ardent Anglophile, though this probably owed more to his extracurricular activities than to any great love of air charts. He spoke fondly of his time in Badger’s and Tiffany’s nightclubs, where he had spent many happy hours slow dancing (‘Oh, my God, really very slowly, believe me’) with the belles of Bournemouth and a girlfriend called Anne.

‘Now we go to Taher’s office,’ he said reassuringly. ‘Believe me, soon you will have camels and then you will leave Ghadames.’ Ned and I exchanged glances – would it be so easy? – and followed Mohammed to the office, a whitewashed hole in the wall run by Taher’s younger brother Ibrahim. He could hardly have looked less like his brother in Tripoli. Where Taher was slim, well-dressed, alert and enjoyed handsome, aquiline features, Ibrahim was a dozy mountain of a man, shambolically clad in a voluminous jalabiya which hung off him like a tent. Overweight and unhurried, he contemplated his surroundings with a lazy air of equanimity. Everything about him took place in slow motion. He was as laid-back as you needed to be in the sleepy town of Ghadames, where nothing much happened these days. If it had been a mistake to count on Taher to get things done, the prospect of definite assistance from Ibrahim seemed infinitely remote.

We discussed the first leg of our journey from Ghadames with him and asked if he could find a guide to take us to Idri, a little less than 300 miles south-east of Ghadames. Ned and I had already agreed that it would be better to look for the camels ourselves, rather than go through a middleman who would doubtless receive some sort of commission and force up the price. Ibrahim considered our request for a couple of minutes, talking intermittently to Mohammed Ali as he did so, and then turned back to us.

‘I find you good guide,’ he said slowly. He knew someone suitable to escort us to Idri and would talk to him later that afternoon. ‘No problem,’ he continued, ‘I arrange everything for you.’

Perhaps we looked unconvinced. Mohammed, as unswerving in his optimism as Hajer in Tripoli, was quick to reassure us all would be well.

‘Believe me,’ he confided sotto voce, ‘Ibrahim is very good man. My God, he will help you. Really, he will do everything for you. Don’t worry about a thing. Mohammed is also praying for you.’