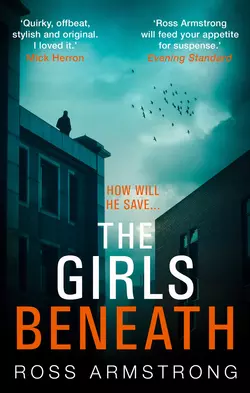

The Girls Beneath

Ross Armstrong

‘Quirky, offbeat, stylish and original. I loved it.’ Mick HerronTom Mondrian is the last person you want on your case. And the only one who can solve it, in this quirky psychological thriller.Tom Mondrian is watching his life ebb away directing traffic as a PCSO, until a bullet to the brain changes everything. With a new unusual perspective, including an inability to recognise faces and absolutely no filter between what he thinks and what he says, Tom’s career is suddenly shifting gear.Tom’s new condition gives him an advantage over other police officers, allowing him to notice details that they can’t see. Now, with his new insight and unwavering determination, Tom is intent on saving three missing girls, before more start to disappear…PRAISE FOR THE GIRLS BENEATH‘Absolutely lovedHead Case. Couldn’t put it down. Tragic, funny and frightening. Ross Armstrong has written another cracker’ Chris Whitaker, CWA New Blood Dagger winning author of Tall Oaks‘Ross Armstrong has created a brilliant hero in Tom, and this novel is an enjoyable addition to the psychological thriller genre. Five Stars’ HeatThe Girls Beneath was originally published as Head Case.

PRAISE FOR ROSS ARMSTRONG (#ulink_c3a045fd-f1e9-5e29-bda4-e6e6cfcd7644)

‘Addictive and eerie, you’ll finish the book wanting to chat about it’ – Closer Magazine, Must Read

‘A twisted homage to Hitchcock set in a recognisably post-Brexit broken Britain. Tense, fast-moving and with an increasingly unreliable narrator, The Watcher has all the hallmarks of a winner.’ – Martyn Waites

‘Ross Armstrong will feed your appetite for suspense’ – Evening Standard

‘Unreliable narrator + Rear Window-esque plot = sure-fire hit’ – The Sun

‘Brilliantly written… this psychological thriller is definitely one that will keep you up to the early hours. Five Stars.’ – Heat, Book of the Week

‘A dark, unsettling page turner’ – Claire Douglas, author of Local Girl Missing.

‘Creepy and compelling’ – Debbie Howells author of The Bones of You

‘The Watcher is an intense, unsettling read… one that had me feeling like I needed to keep checking over my shoulder as I read.; – Lisa Hall, author of Between You and Me

ROSS ARMSTRONG is an actor and writer based in North London. He studied English Literature at Warwick University and acting at RADA. As a stage and screen actor he has performed in the West End, Broadway and in theatres across the UK, where he has worked opposite actors such as Jude Law, Joseph Fiennes, Kim Cattrall and Maxine Peake. Ross’ debut title The Watcher was a top twenty bestseller and has been longlisted for the CWA John Creasey New Blood Dagger.

The Girls Beneath

Copyright (#u4a583913-dc1f-509d-b3f4-4bad9de5bebd)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Ross Armstrong 2018

Ross Armstrong asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

First edition published with the title Head Case in Great Britain in 2018

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9780008182267

Version: 2018-10-29

For all those who

think differently

‘Hush little baby

Hush quite a lot

Bad babies get rabies

And have to be shot’

CONTENTS

Cover (#u28abf1a0-eff2-563b-94f2-41b4ae013df5)

Praise (#ulink_e72ed24b-22a5-53fa-bf45-7ed9ee2e210a)

About the Author (#u57b49263-d95e-5cb9-9a33-8d8dd21ce506)

Title Page (#u39fbbfd6-baf2-58dd-bcf0-f526321340c0)

Copyright (#ulink_c7600f71-113f-542f-b665-79d28e987505)

Dedication (#u1f56bcc9-683b-59c2-a80e-9d9eb6df5f6a)

Epigraph (#u5881f70e-cf5e-517f-9c53-3f9daa5bd425)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_3cf2f4de-d5de-5f69-8a81-e3471a6e6724)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_50e4a10e-fec6-5de8-afc3-7cc4bf9463a0)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_9f716d39-a97b-59a0-8a8f-683e5306827b)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_ab6e3a24-e97f-534f-9c75-2b545bc3e864)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_78e7753b-97d7-5e0f-96b5-50f036cd1267)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_dde4576a-6ffa-54ec-94e3-f558c76acc0f)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_da07a303-0b2d-5c02-a3b6-0987b8776a83)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_126f1d66-a5eb-56c6-b29c-dc500b647813)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_fd1ea10a-8bc9-56eb-b2f5-861ebfb3fe99)

Documented Telephone Conversation #1 (#ulink_74b156bd-ca16-536a-be3e-98ba7e506d72)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_75acfdc1-2c75-50e1-951f-d7d4b703c14a)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Documented Telephone Conversation #2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Documented Memory Project #1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Documented Memory Project #2: Tape (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Documented Memory Project #3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Documented Telephone Conversation #3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

I remember, a note, she passed… Documented Memory Project #4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Afters (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

7 days till it comes. (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_8fe3e3cc-47ba-5e0c-abba-a8ddb11fb751)

‘Dee. Dah dah dah dee dah, dah dah, dee dah…’

It was a year of miracles. The year I learned how to walk and talk again, the year I met Emre Bartu and the year the girls went missing.

But first came December.

The weekend before my first week as a Police Community Support Officer began. The last week in which my brain’s valleys, ridges, streets and avenues remained in perfect working order.

Back when I thought a lot differently. Before I became ‘Better Than Normal’ as Ryans says. He says that because in some ways I definitely am. Better than you, I mean. No offence.

It’s a Christmas gift that will lie under my brain stem, wrapped in the folds of my cerebellum, romantically lit by my angular and supramarginal gyrus, for the rest of my grateful life.

So let’s go back to the last week when the inside of my skull was anatomically ‘correct’ and aesthetically as it had been since the day I was born.

When my brain functioned as it does for the ‘normals’. The others. The ones devoid of irregularity or uniqueness. No offence.

Before the fractures. Before the accident.

If it was an accident.

2 (#ulink_10cc8dc1-251e-50f5-a20e-3a94b32f3368)

‘So it’s you

The one I thought I knew, I knew,

No matter what we put the other through

It’s always you’

The truth about Gary Canning is revealed to me by Anita herself. Like most things, I don’t see it coming.

I imagine Gary as a P.E. teacher, displaying his sporting prowess and gym-earned physique to the kids of Tower Hamlets as he coaxes the unwilling into exertions like rugby, basketball or maybe even worse. But in actuality, Gary is a Geography teacher with a fair to middling beard. It has pretty good coverage but is patchy in a way that suggests inconstancy of character, a fatal lack of conviction in his genes, or a rather flawed grooming technique. I know this because I find his picture on social media. That’s when I first see the face of Gary Canning.

Gary Canning blogs about food and travel and seems to have ambition beyond the school system. Photos find him caught candidly by the camera lens in clearly orchestrated scenarios, curated to paint him as a soulful character; playing a banjo with his eyes closed, or blowing bubbles with some sort of child, or larking in a European villa while holding a float to his head like it’s an antenna, in a move that will soon be lauded by his fawning friends as ‘classic Gary bants’.

He lists his favourite world cities as Tangier, Iquitos and Bobo-Dioulasso. Only half of one of which I’ve ever heard of. But I guess it isn’t surprising Gary Canning has been to places I’ve never even heard spoken aloud. Given that I’ve never even been to Paris. I thought about taking Anita once but then I forgot to book the tickets and my life moved on. But I’m sure Gary Canning’s been to Paris. Paris is child’s play for Gary Canning. Gary Canning probably went to Paris without even realising it. Because that’s just Gary Canning. Good old Gary Canning.

Anita’s hours have always seemed wildly inconsistent for a job I’d always thought was fairly strict in terms of time frame. Which I’ve never wanted to bring up for fear that it will seem like I’m misunderstanding her life, or being sexist, or teacherist, or some kind of combination of everything that shows me for the true chauvinist idiot I didn’t know I was.

When her late-homes stretched to late nights, I stopped asking questions, as I disappeared into my world. One dominated by online gaming and films I’d seen when I was younger but wanted to watch again to check if they’re still good. Or the lure of sports results on my phone, or direr still, merely staring blankly at the screen glow waiting for that appetising hit of something. Not even current affairs; I can’t handle that, everything is a killing or a manhunt and it gets me down. No, I prefer the safer land of sports news. Where the only tragedies are poor tactics. Where the only manhunt is inane ‘gossip’ about a Portuguese manager ‘tracking’ some sixteen-year-old French-African midfield wunderkind.

The Thursday night before the Monday I’m due to start my latest career experiment begins typically. Anita arrives home and I detach myself from the smart phone umbilical cord to greet her with my best conversation and the second half of a bottle of wine that I’ve started before her arrival. Already one in, having apparently ‘decompressed’ with a single glass on the way home ‘with her colleagues’, she tells me about her day and I listen loyally, retroactively defending her where appropriate from the passive-aggressive comments made by the head of the History department, my mind only occasionally drifting to how much a truly world class defender costs these days and what exactly I’m going to do with the rest of my life.

I’m always a good listener because it’s easier when the other person talks. After all, I know all my stories and listening is more relaxing than talking.

She suggests we go into the bedroom so she can tell me something. This is nothing particularly new as we both like lying down and the light is more relaxing in there. She’s never loved the feel of my parents’ old house but it suits our situation and I like it just fine. But then, I’m easy going, genial to a fault perhaps. I’ve always wanted a simple life, which is the subject our conversation turns to as we both stare at the childish glow-in-the-dark stars we’d put up on ‘the night of the moving in’, which had somehow stuck around to bother the ceiling with their pretty and naive shimmer.

It feels like we’re on the cusp of so many new things tonight. I don’t know why I’ve chosen tonight, in particular. But I have. Call it instinct.

I go to kiss her but she instinctively lifts a limb to flick me away like a holiday fly. It’s a feeling I’ve become used to of late. Her eyes flicker with uncertainty before she speaks.

‘What do you do in your training anyway? Is it all rolling over cars and firing at moving targets?’

‘Yes, it’s a bit like that but without the guns. Or the car, or the excitement,’ I reply, adjusting my head on the pillow.

‘Ha. I think you’re going to be really good,’ she says, turning her head to me, her cheek gaining a green sheen from the plastic stars that barely light the room at all.

‘I did do a personality test the other day though,’ I say.

‘Did they find anything?’

‘Ho ho. Yes actually. They said I was very empathetic.’

‘Good,’ she says, pushing her hair behind her ear.

‘Compassionate.’ ‘Good. Well. You are.’

‘And they thought compassion might be my main strength, as they said I’d scored very badly on observation.’

This does make her laugh, like hot tea, warming and over-stimulating me. But she soon cools. She seems to pull away, sensing a renewed push for intimacy in the air. Not that she fears my close proximity; we’ve remained very intimate, in all ways but one. And I’m told that’s a bit of a thing with relationships after a while.

‘They said that if I’d scored any lower they’d have had to declare me legally blind.’

She laughs, somewhat nervously, I think.

‘Although he said that some blind people have scored very well on these tests, so that’s probably unfair on them.’

As she laughs, I realise I don’t have to tell her anything about my personality. She’s the person who knows me better than any other. Who has been witness to my best and worst emotions. This is the being that I had picked above any other to eat with and sleep next to, the one person whose hair it is vaguely permissible to randomly stroke and smell, who has looked at my face over the past six years a good deal more than I’ve had to myself. She knows me from the tiniest colour in my eyes to the softest things I’ve ever said. I reach down into my pocket.

‘You’re just… I’d say your personality is… doughy.’

‘Sorry what?’ I say.

‘Doughy. Just a lovely, happy, doughy man.’

‘Kind of sounds like you’re saying my personality is fat.’

‘No, you’re not fat,’ she says.

‘No, I know I’m not,’ I say, vocally straining.

‘I mean, soft. Lovely. Like bread.’

Our eyes lock and she withdraws her hands, as if thinking four moves ahead and wanting no part of what comes next.

We turn and look up at the fake stars in a silence that turns over many times. It has endless pockets where it feels like one of us may speak. It runs on and on until at one point it has a little hate in it and at another a delicacy so fragile that it would shatter if you were to reach out and touch it.

Then I feel something. One of the tiny stars has fallen and is resting on my thigh. Then Anita looks down at it and finds a look somewhere between care worker and executioner. As she tells me that she’s been doing it with Gary Canning in the staff room after school for a term and a half. Her back against the pigeonholes. Her pencil skirt hitched up.

She doesn’t say all of that of course, but that’s what I hear. I want to be angry and after she leaves I do a lot of pacing and fist clenching as I examine Gary Canning’s social media output. I’m not really the sort of guy who raises his voice. I’m naturally better with compassion than passion, I suppose, and it’s not good to force these things. And she’s my best friend. It’s hard to be angry with your best friend with tears in her eyes.

The fact that she’s already arranged to stay with a friend leaves me logistically as well as emotionally lonely. But I’m always good with my own company and nothing if not resilient. Although resilient isn’t the word she used in the only moments of our conversation that bordered on unkind. Something about ‘ambition’, I don’t know. I log onto a gaming community as my heart pounds away further back in the mix.

The last time my heart pumped so hard, was during a training session with a self-defence specialist. I made myself a dead-weight to prove the demonstrator couldn’t lift me and the next thing I knew we were both on the matted ground, him with his knee poised over my chest, having dug it into me as we fell together. I gasped for breath as I looked up at the crowd of faces who leant over me. I hadn’t been so vulnerable since I was a child. And here I am again.

I met Anita at the party of a university friend I was already making plans to see less. I was pretending to be a smoker, and doing it pretty badly, as an excuse to not be inside with some awful people. Passable on their own, the flat was small and the men in particular were drunk and brash, which was a potion that ensured we were both having a terrible time. She spotted me coughing on a light cigarette, like a child taking it as a punishment, and we quickly decided that as we both hated smoking we should persevere together, mostly to stay away from the noise and fury of fellow twenty-two year olds newly arrived in London and convincing themselves they were ‘cool bro’, and having a ‘wicked time’. Batting away my cynicism on a cluster of topics, she made me laugh more than anyone had in my three years as an undergraduate and when it rained we sheltered under a tree and stayed until the last drops from the fern tumbled into the mud below our huddled bodies.

I want the days after she leaves to be the kind of textbook break up weekend I’ve always heard about, comprised of time spent in my pants and regular doses of alcohol, but that’s a little too close to the norm for comfort. So instead, I run, racking up 15k the day after she leaves and double that on the day after. Getting fit again has been one of the pleasures of the training process, but today I am running just to run. A picture show clicks on through my head with every thud that my feet beat on the tarmac. Each sting observed and recognised. I look out on the streets and streets that pass and see little of interest, which is at least in perfect keeping with the training officer’s perception of my observation skills, and Anita’s of my consistency. Somewhere in the distance, Gary Canning rests his back against the pigeonholes and doesn’t even laugh. He breathes deep and leans, blissfully unaware of me, and thinks of India.

I reflect on this as I reach into the pocket of the jeans I was wearing the night she left. I may never be praised for my instinct, I think to myself, as I look at the tiny box in front of me. The one my father had pulled out in front of my mother in far more romantic surroundings many years earlier, under real stars, under the lights of Paris.

I think about my sense of timing, as I examine the little diamond before me. And as I wipe my eyes with my index finger and thumb, I laugh.

3 (#ulink_eedaa10f-1c59-5e1d-bc5b-0a302862c643)

‘You’re my little one

Say I didn’t love in vain

Please quit crying honey

Cos it sounds like a hurricane’

It’s one degree below freezing on Seven Sisters Road but I’m not complaining. The first thing officers have to combat is the weather. Christmas is three weeks away and snow has settled, shrouding Tottenham in a crisp white blanket. Towelling it up like a baby after a bath. Hugging it close and singing it a lullaby.

I breathe into my gloved hands and watch the cloud stream onto them and then up into the slate coloured sky. If you don’t like being out on the street, then try another profession. It’s our job to know our neighbourhood, which means mostly being out on foot or on your bike. Fortunately for me I’ve got one advantage. I know these roads like the back of my arse. I’ve lived here most of my life.

I’ve watched corner-shop keepers get older and kids I went to school with become upstanding members of the community or, more frequently, go the other way. I’ve seen their little brothers, once new born babies who held on tightly to my finger in their mother’s arms, grow up to get their very own ASBOs. I’ve given them out myself.

Or rather ABCs, the ASBO is the last resort before criminal charges are brought. An ABC comes before that.

That’s my first act on my first day, Monday at 10.10 a.m. Drawing up an Acceptable Behaviour Contract for my schoolmate Dom Minton’s half-brother, Eli. He’ll probably be the last kid around here to get one, as they’re soon to become defunct, so I suppose you could say this is a bit of a Kodak moment.

Eli has a birthmark that wine-stains the top left hand side of his face and I feel sorry for the kid. School is hard enough without the kind of stares it must bring.

I take advice from my sergeant on it all. I look at Eli’s case notes and write down a few of his greatest hits. Then I ask if he would agree to the reasonable suggestion that he should’ve thought better of them.

The severity of his list of misdemeanours escalates sharply. Something dark in me struggles not to laugh when I glance at them over his shoulder as he reads:

CONTRACT

I will get to school on time.

I will not graffiti my school toilet wall.

I will not climb into any lift shafts.

I will not throw rocks and debris at passers-by.

I will not attempt to set fire to people.

‘Does that sound fair, Eli?’ I say.

He looks up and recognises me. It helps that I know his brother. But he’s saying nothing.

‘Think you can manage not to set fire to anyone? For a while? Maybe try not to ignite anyone just for this week and see how it feels. Sound like a plan?’

I’ll probably learn not to take the piss at some point but I’m new at this. He looks at me, stone-faced, then signs.

‘And you understand the consequences of not sticking to the contract, don’t you? Eli?’

All I hear is the sound of engines and tyres on the road.

‘Eli? I need to hear you say it, mate.’

He looks up again, having been fascinated by the pavement for a few seconds.

‘Yes I do, PCSO Mondrian.’

He leans quite heavily on the ‘SO’ and not so much the ‘PC’ as if to make a point, but I still pat him on the shoulder and attempt a smile that aims for reassuring, while steering clear of any local-bobby-earnestness that might engage his gag reflex.

He barely looks half of his fourteen years to me. But then he did throw a brick at a pram and try to set fire to an old man so perhaps I shouldn’t feel too sorry for him.

I wish I didn’t feel this way. But living around here, experience tends to toughen your opinions.

His dad grabs him by the shoulder I patted and leads him back to their car, clearly not delighted at having to take an hour off work for that. I hope he isn’t too hard on him, I hope he isn’t one of those dads, but then it’s difficult to tell. Eli pulls away as if the shoulder already holds a fresh bruise that’s more than a little tender.

On Tuesday I see my first dead body. I’m early on the scene at a gruesome traffic accident, a head-on collision that’s killed the driver of Vehicle 1 instantly. His chest and the steering wheel are an item. His jaw is locked wide open. His passenger and the driver of Vehicle 2 are taken away and are in critical condition. I meditate on the nature of suffering, the end of things and déjà vu. Then I sack it all off, take an early lunch and have a steak and kidney pie.

On Wednesday I check out a break-in where the intruder has done nothing but broken a window, nicked one laptop and shat on the bed. People are very strange. Some watch videos of executions. Some change names on gravestones so they become rude words. Some are purely vindictive with their poo.

On Thursday the highlight is standing out in the cold for five hours, making sure the peaceful demo about closing the local library doesn’t erupt into a volcano of bloodshed. There’s no chance of that. It was more the sort of event where someone erects a cake stall, but on this occasion no one even did that.

Thursday’s lowlight is getting a call telling me that Eli has neglected to turn up for school. His dad, out of town for a few days, was contacted immediately and ominously asked in a mutter over the phone if he could ‘deal with it’ himself. None of this seems very good for Eli, so seeking some other option I trudge over to his brother Dom’s house.

‘What can I say, the kid’s an evil little fucker at times,’ Dom says, hands tucked into his jogging bottoms. ‘But he’s my brother.’ This much I have already gleaned.

‘Do you think your dad’s… a little hard on him?’ I say, searching for the most delicate way to put it.

‘Dad’s no soft touch. Never thumped me. But then Eli is… Eli.’

‘Eli? Eli!’ I call, seeing his face peeking out unsubtly behind the kitchen door.

Before Eli drags his bones towards me, Dom hangs his head and then whispers to me, ‘Sorry, Tom. He’s having trouble at school, they’re pulling him into some gang. It’s nasty. He asked if he could hide out here.’

As he enters, I see the picture of a kid stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea. Shitty dad at home. Shittier kids at school.

Eli clearly isn’t ill and I have a choice to make. He’s breached his contract and I’ve stumbled in on him doing it. Let him have it and dad will come down hard on him. But at least a full blown ASBO would give him a legitimate reason to stay away from his new friends in the evening.

One thing’s for sure, Eli is getting fucked from every side whatever I do. He’s contributed pretty amply himself, yet I know I could save him some hassle if I just look the other way on this occasion.

But this is my first week, so I keep it simple and I call it in.

Later, he’ll say I was ‘victimising him’.

And what’s true is, I could’ve been kinder. I think they call it tough love. I hope, in that tiny moment of decision, that everyone else isn’t too tough on him as a result.

*

It’s been a week. I can’t quite tell what sort yet. But it’s certainly been a week. Friday has come shaped like mercy.

*

‘Dee. Dah dah dah dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I get these tunes in my head sometimes, I think everyone does it.

Earworms. People say you choose the tune because the lyrics associated hold the key to something you’re mulling over in your subconscious.

But I don’t know about that.

I barely even remember the words. I try to keep it down as I zone out, muttering under my breath as I walk.

‘Dee. Dah dah da, dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I get a call on my radio about a minor accident at the other end of the main road. I need to go and direct traffic. I’m not sure this is what I was birthed for.

At least you can pick your hours, within reason. You have to cover thirty-seven in a week and they like you to take one evening. So I went for a five-hour evening shift on Thursdays, seven till midnight. Then took eight hours on all the other weekdays, leaving my weekend free. I consider the merits of this time format. Even my thoughts start to bore me.

I count them as they as they plod through me. Dry and empty.

This is a thought.

This is a thought.

This is a thought.

Then one comes along covered in this morning’s regrets:

I was called to a house after a neighbour had complained about frequent raised voices and commotion, as well as the sound of skin on skin contact and not the friendly kind. I didn’t bother the neighbour on the right side of the house before calling on the home in question. They had been brave enough to make the call and I didn’t want to give them away by paying them a needless visit first.

As I approached, the neighbour on the left side came out, and when she saw me she hustled back inside quickly. She had a look of intense fear about her. I wondered if that came from the build-up of what she was probably also hearing through the walls, night after night. A man, taking out his stresses on his wife. Or whoever else.

The neighbour looked spooked so I didn’t say a word. She didn’t want any trouble, and to her maybe I meant trouble, so she shot back inside to avoid whatever was about to happen. She gave me a funny feeling, her presence sparking a strange sensation close to déjà vu.

When he answered the door, the man, bald, moustached and laying on the innocent look as thick as it comes, led me inside, where a woman, presumably his wife, sat in the kitchen giving little away.

An extraordinary sense of creeping unease came over me, a tingling on my skin, which had started when I saw that neighbour’s face.

I asked the woman if she was okay. I asked him the same. They both replied with a nod. It felt like something hung in the air between us that I wasn’t allowed to touch. There seemed to be a palpable prompt the scene itself was giving me, other than the possible violence between them. Another cue that I wasn’t picking up on.

The silent couple… The noises through the wall… That neighbour’s face.

‘There’ve been reports of a disturbance coming from this residence. I’m duty bound to follow that up. So… anything I need to know?’

Nothing but the shaking of heads.

‘Anything at all?’

In the next deafening silence, I tried to communicate to her wordlessly that she didn’t have to take any shit. And to him that if he was doing something to her then I’d be back with uniformed friends and trouble. But all I said was:

‘Well, we’re a phone call away.’

I shook off the tingle and reluctantly got out of there, resolving to do the only things I could: make peace with my limitations, and with the sour fact that she would probably never make that call, and record the encounter in my pocket notebook.

I can feel my mind listlessly erasing the encounter, as I make my trudge through grey reality towards traffic duty.

But then, they’ve recently found you can’t erase memories. They’re physical things. They make visible changes to the brain. Some are hard to access if you haven’t exercised them recently, but they never disappear. If you took my brain out of its case, you could see it all.

• There’s the crease that holds my parents’ smiles at my fifth birthday party.

• There’s the blot that is my first crush’s face.

• There’s that neighbour’s face, just next to it.

• There’s the dot of possible heroism. Watch me be disheartened, watch it degrade and fade.

This is not the electrode up my arse my life needed. This isn’t even a power trip. Perhaps I should have stuck with charity fundraising on the phones, say my thoughts. But I guess mum and dad would be prouder of me doing this.

The radio kicks in.

‘PCSO Mondrian? This is Duty Officer Levine, over.’

‘Yeah. Yes, this is me.’

‘… You’re supposed to say over.’

‘Over,’ I monotone.

‘So when someone calls for you, say go ahead, over. Over.’

‘Go ahead, over.’

‘Understood? Over.’

‘Yep.’

A pause. I wait.

‘Don’t say yes, say affirmative. And you didn’t say over. Over.’

I sigh, away from the walkie-talkie. Then steel myself.

‘This is PCSO Tom Mondrian. Affirmative. Go ahead. Over.’

‘Understood. Hearing you loud and clear. I’m over by the loos, over.’

‘Understood… over.’

‘What a wanker,’ I mutter to myself.

Cccchhhhhh...

‘And after you’ve finished speaking, take your finger off the PTT button. We all heard that.’

Crackles of laughter from someone else on the line.

‘You forgot to say over, over,’ I say.

I remember to take my finger off the button this time as I walk along.

‘Not funny, over,’ he says.

But it was a bit.

Levine is clearly the pedant of the bunch. I keep walking, my feet crunching in the snow.

Here we are. Broken glass on the tarmac. Red faced fella at the side of the road. A light blue Astra with one door open, diagonally up the kerb. Levine sees me and holds up a hand. His posture says, ‘I’ve got this thing locked down, you just stand way over there.’

La-di-dah. The beat goes on.

The ABC. The body. The beat. All firsts.

I wonder if anyone has ever fallen asleep while directing traffic. Could be another first for me this week.

I check my watch and see there’s an hour until my week ends. Nearly time to head back to the station locker room, change, clock off. Maybe a drink with the team if I’m unlucky.

Levine signals me to allow traffic around the car from my side, while he holds vehicles at a stand at his end for a while.

I signal. I smile courteously at the drivers as I do so. La-di-da.

I see many faces I recognise.

Amit from the paper shop down the road. Zoe Hughes from Maths drives past, averting her eyes to ignore my existence. She didn’t always.

I glance to the cluster of shifty kids on the other side of the road to make sure they see traffic is being held and let through at intervals. I’m only looking out for them, but they take one covert glance at me, put up their hoods and scarper off, one holding something weighty in a black plastic bag that’s got them pretty excited.

I probably should be curious about what it is, but that’s not really very me.

‘Dee. Dah dah dah dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I stop the flow. I can barely see the driver in front of me through his tinted windscreen. But I squint to get a look at him in there and see his outline change. He taps the wheel, jittery, maybe coked up, which would account for the nerves. But I’m not going to create any extra trouble for myself. He glares at me, stiller now, as I hold my ground, letting him know I know there’s something up.

Then I wave him through. He shoots away hastily, as I snigger, enjoying my power to intimidate. Then I move to the side of the road, making sure I’m still visible to passing traffic.

Blue car. Red car. White car. Mini. Bus… Bus…

Oh!

I feel tired. Not just tired, faint. I shake my head. Somewhere I hear the bus stop but I don’t see anything. It’s darker now, all around me. I feel sick. I’m fighting to keep my eyes open. I try to go to ground, layer by layer, as a tower block might be detonated or dismantled.

I feel like I’m going to vomit but I don’t want to in front of all these people. It’s a shame-based reflex. I try to hold it in. I try to hold it together. There are shouts behind me.

The sound of footsteps. Running. I just need to reach the floor and everything will be okay. But my ears are going crazy horse. A high-pitched squeamish noise. A fresh white blah blah blah. Like TV failure.

Nearly at the ground now. It all flashes. I swallow ocean breaths. I wonder whether I’m causing scenes. My hands reach for the tarmac black. That high pitched squeal blazes on.

The world looks like it’s under a slow strobe.

Then my back is against the kerb. Clouds forming, crowd forming. I know something is wrong for sure.

I pull out my phone and try and call the… or should I use my… what’s the number for the 999…

I stare at the phone. Not fainting yet. Holding on.

Its numbers are strange. Just lines. Like Greek, or Latin. Symbols I don’t understand. I comprehend nothing.

My head is wet with something. But I don’t know what. I see Levine running up to me. I’m not sure whose blood this is.

I shout to him to check everything is all right.

‘Take the hard road up.’

I don’t know why that comes out. It’s not what I intended.

I try again. As I crawl towards him, off the pavement and onto the road.

‘Perhaps the hard road’s impossible!’ I shout as I crawl and my hand drags past more wet.

‘Take the hard road up. Anything is possible!’ I shout.

It doesn’t feel like my voice. He’s nearly with me. I see the bus has emptied and its passengers are looking at it. And me.

It’s slow motion. It’s hard tarmac broken glass music video inner city incident news commercial heartache.

That high-pitched squeal sings on and on.

A song from a passing car radio strikes up.

‘We lived in this crooked old house

some cops came over to check it out

left on the step was a little baby boy

In a soft red quilt, with a rattle and a toy.’

My hands shake beneath me like an engine does before it stalls. A guy with a busted tooth shouts something.

Before my head falls, I notice the bus has two broken windows. One on each side.

They’re all on their phones. It’s a picture that blurs.

My ears still work though. Listening to the radio song.

‘You’re my little one

Say I didn’t love in vain

Please quit crying honey

Cos it sounds like a hurricane’

I wonder how those windows got broken.

That’s my last thought for now. Before I go.

It’s just one of those things.

Some days you meet the person you were always meant to be with.

Some days you get shot in the head.

4 (#ulink_899656b8-f506-5255-b112-7cd824aa0b4f)

‘‘Can’t get that, dah dee dah, dah dah, my head…’

‘Good. You’re awake. Looking good,’ says the voice.

Male. Warm. My thoughts run slowly like traffic jammed cars. His face comes into view.

I’m cold. I guess I should do something. Say something maybe. Missed it. The chance has come and gone.

We sit in silence for a while. Everything has changed.

‘Cold,’ I say, trying to get things moving, in my head.

‘Oh yes. It is a little chilly.’ He turns and nods to someone. He smiles. I lift my head to see who he’s looking at, but by the time I do they’re gone.

Where am I? A hospital. I guess.

‘How’s it all feeling?’ says the man.

‘Unsure,’ I say.

‘You’re unsure how you feel? Or you feel unsure?’

‘The second one.’

‘That’s understandable. Any pain?’

‘A little in the head.’

‘Also understandable, that’s just swelling in the cranium.’

‘What’s the… chrysanthemum?’

‘It’s a flower that blooms in Autumn, but that’s not important right now. Your mental lexicon is still recovering, which I’d expect. Say after me, cranium.’

‘Cramiun.’

‘Good. Your skull. Your head. We had to get in there a little.’

‘In there?’

‘Yes, we had to remove the bone flap. But we replaced it. Everything went reasonably well.’

‘Re… Re… Re… Re… Reasonably?’

‘Well… your sort of accident isn’t the sort of thing one always recovers from. But things are looking up.’

I’m putting it all together again. The bus. The shattered glass. The man running towards me. A man I know?

… Doreen? … Liam … Loreen?

‘I assume you haven’t been told what’s happened to you then?’

I assume I haven’t as well.

I drifted in and out. Of the light and the grey. I don’t know what was a dream and what was… whatever this is. I’ve seen many faces hover over me. I remember being moved, I think. One second I would be one place. The next, the ceiling would tell me something else.

I realise I have no concept of how long I’ve been here. It could be weeks. Months. Longer.

‘How long?’ I say.

‘How long what?’

I struggle with the structure of the question. I feel my eyes rolling around in my head. With each tiny movement, there’s a crack of pain somewhere deep inside my thinking organ.

My eyes begin to water as I strain to process the question, to hold onto my thoughts. I make some sounds from deep within me. I breathe deep, trying to speak, but I can’t. Instead. I cry.

My nose runs. Hot tears roll down my cheeks. Big old-fashioned sobs, despite myself. I don’t feel like crying. And yet, I am crying. Every breath shudders with effort between my lungs and my mouth. I feel like a puppet controlled by an inebriate puppeteer.

My hands scramble around for a tissue. There is one next to me but it takes me an age to drag it out from its cell.

He waits, watching. Patient.

‘Tom? You asked me… how long?’

‘How long… from then… till now?’

‘Today is Sunday, you sustained the injury on Friday.’

It seems impossible. If he’d said I’d been here a year, or two, I’d have believed him. My muscles feel brown and dappled. I grapple with the controls like a madman, a blind pilot. I must be older. Two days? They have to be lying. But to what end?

It’s then that I notice there is someone else in the room, to my left. My neck turns so my head can look at him. He looks back. His face is difficult to read. He looks apprehensive. I look away and he does the same. Then I look back at him and he looks me in the eye. He says nothing. Just analyses me. He must be some underling. He’s younger than the other man. Although I couldn’t say how old the man in front of me is. My brain isn’t giving me all the answers I need yet. His voice interrupts us as I go to look at the silent man for a third time.

‘Yes, it may seem longer. That can happen. Would you say it seems longer?’

‘Yes. Yes.’

‘That’s interesting.’

He writes that down. Out of my periphery I analyse the silent man. He faces the doctor, too, not moving a muscle.

‘Do you know what happened to you, Tom?’

The question lingers in the air…

The bus. The shattered glass. The blood. The shouts. People with their phones out. I crawl across the road. I feel sick. No pain. But I feel faint. I hear a song from a nearby car radio. The man runs towards me.

‘I… I… had… a stroke?’

‘Hmm. Interesting.’

He writes that down. Then scratches his nose. He turns as a nurse comes into the room and hands me a glass of water and a pill.

I take it off her. Steadily. I look at my hand and try to will it to do my bidding. I put the pill in my mouth and force the water down the dry passage of my throat. I stare back at my hand and order it to give the nurse back the glass. When I turn back to the doctor he is checking his watch. His eyes meet mine and he smiles, sunnily, full beam.

‘Now, how long would you say that took? That little sequence of taking your pill and drinking your water.’

Is this a trick question? What is their game?

‘Ten… twenty… ten… seconds?’

He glances to the nurse.

‘That took six and half minutes. But don’t worry. I’m confident things will get easier.’

He comes a bit closer now. The man next to me does, too. It’s become intimate.

‘Tom. You were shot. In your head. Do you understand?’

I want to laugh. So I do. Ha ha ha ha ha.

There’s no gap between think and do. Ha ha ha ha ha.

The tears roll down my face again. The others stay stock still. As I laugh and cry. I don’t know why I do either of these things. My feelings fire off in all directions like stray sparks. I laugh, I wail.

Then I stop. I look at the nurse. Then at him.

‘No. I wasn’t shot. I can’t have been. It didn’t hurt. I’m alive.’

He breathes in, cautious, unsure how to put this.

‘The brain has no pain receptors. The nerves in your skin can’t react fast enough to register impact. A little bullet, at that speed… It just went in.’

‘And out…’

‘Err… no. It just went in.’

‘And you got it out?’

‘No. My God, no. Much too dangerous to move it, I’m afraid. It’s still in there, in three pieces. But don’t worry, it doesn’t pose you any danger. Think of it as a souvenir.’

He pops out a one-breath laugh and turns to the nurse for support but she doesn’t join in. When I straighten up, so does the silent man. Copying my body language is supposed to make me feel comfortable, I suppose. But he is eerie.

‘So,’ says the doctor, ‘all your vital signs are remarkably good. Another twenty-four hours of monitoring and tests, then, all being well, you’ll move from intensive care to a general ward for recovery. Then you’ll spend some time in the rehab unit, and that’ll give us an idea of what outpatient care you’ll need after we discharge you. Sound good?’

My breath rattles. I want to say things but thoughts rush at me. I grasp at consonants. I try a ‘p’, an ‘m’, an ‘n’. Then back to a ‘p’. He comes closer and puts a hand on me. I am calmed.

‘But I was shot… in the head?’ I murmur. I hear myself. I sound like a malnourished tracing.

‘Yes. But I’m confident you won’t be here too long. I think you’ll walk with a limp for a good long while and certainly a lot slower than before, for now. And so will your speech be. Slower, I mean. But you should be… next to normal, in no time. Better than normal perhaps. I look forward to seeing how it all pans out.’

He looks at me, smiling indulgently. I take a note of his features. Ogling them for what is probably five or so minutes.

He has a beard. He has small brown eyes. He is half bald. He is lightly tanned. He has soft grey hair. He has a striped blue shirt. It has a purple ink stain on it.

‘Somebody… shot me?’

‘It would appear so, yes. Now, all I’d ask of you is to take it slow. I will be with you throughout this process. You certainly don’t have to go back to work for a good long while yet. And they’ll absolutely look after you well, financially speaking, so you don’t need to worry about any of that. You were injured on duty, you’re getting the best treatment money can buy. In my opinion, ha! You shouldn’t want for anything while you recuperate. If there are abnormalities – and considering the places the bullet debris has come to rest in, there may be abnormalities – I’ll be with you every step of the way. We’re going to handle those… differences… together.’

‘Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Why am I not dead again? Why is my head still on my shoulders? What was I shot with?’

‘Well. A gun. A sub machine gun, I’d say. But just once, so that’s good.’

‘In… in… war… in films… in war… the head means… dead.’

He’s excited by this, standing and taking his pen in his hand to gesticulate with.

‘Good question. Good cognitive reasoning. Now, I can only tell you that when you’ve seen people shot in World War whatever, or Kill whoever, or The Murder of Whichshit, the science is somewhat… bollocks. Sorry! Poppy cock, I mean to say. You do often die with a shot to the head. Very, very often. But a bullet wouldn’t really have the momentum to knock your head much to the side let alone blow it off its shoulders. Think of it this way, if a gunshot were powerful enough to throw your head back significantly, the momentum of firing it would throw the gunman back violently, too. And that’s not the sort of device that would be very viable on the mass market. What a gun is, is a compact handheld product made to eject sleek aerodynamic discharges that glide smoothly into flesh. So along with the shock and speed of the event and the way the device is engineered, of course you wouldn’t feel a thing. Which is a bit of a result in a way, isn’t it?’

I’m not sure how to feel about this statement at this point.

‘Ask us one more question for today, please. It’s very good for you to ask questions. It’s a useful process. You’re doing very well, Mr Mondrian.’

‘Will… I… get… back to normal? Normal normal? Absolute normal?’

The nurse averts her gaze. The cold room seems to get colder. He clicks his pen a couple of times and then comes further towards me, his face so calming. His rich voice echoing as if it falls all around me. He has me. I am his captive audience.

‘The brain is an incredible thing. It has helped us to achieve amazing feats. Like building aeroplanes. Performing complicated long division in our heads. Constructing the internet. So on, so forth. But do we really know how it works? Not really. I certainly don’t and I’m one of Britain’s top neurologists. Ha.’

He looks at the nurse. No laughs again. But I like him. I’m usually good for a pity laugh, but humour is difficult to muster at the moment. The cues are difficult to pick up.

I laugh, a good minute too late. The room nods patronisingly. Then the Doctor steps in again to save me.

‘So, in short, to say “I don’t know what’s going to happen” is an understatement. I mean it’s an understatement to say it’s an understatement. I mean I don’t have a single clue. I don’t even know if I don’t know! But I’ll tell you what. Whatever your brain throws at us, we’ll just work it out. Sound like a plan? It’s fair to say it’s already making adjustments.’

‘Adjustments?’

‘Yes. Adjustments. It’s an incredible machine. It will adapt. It has plasticity. It will learn to work in a different way. That’s what it does. That’s the one thing we do know. So… will you get back to normal?… No, I shouldn’t think so, no. Is normal something to be desired? To some people, yes. Is normal changing monthly and are you going to think in a completely, wonderfully, excitingly, unique way? Yes. I think so, yes. And. Whatever. Happens. We’re going to tackle it together.’

He claps his hands lightly.

‘Does that sound good, Tom?’

‘Yes. You are. You are. You are?’

‘Jeffrey Ryans. We have met before but don’t worry. You’ve been in and out of consciousness. No need to feel gauche. Any more questions?’

‘One.’

‘Fire away.’

I collect myself. Trying not to turn to the man. But I have to ask.

‘Who… who… who is… this man sitting next to me?’

‘Sorry, who?’ Jeffrey says.

‘Him,’ I say, pointing to the reserved gentleman on my left.

‘Ah. Now that is interesting.’

‘What?’ I say.

‘You don’t recognise him?’

My eyebrows furrow. I squint. I try to conjure something.

‘No. Should I?’

Dead air. The nurse’s face has collapsed.

Ryans smiles, a mixture of amusement and compassion.

‘Well. Tom. That’s you.’

I don’t understand this concept. I look at him pleadingly. He speaks again.

‘That’s a mirror, Tom. You see its edges? There?’

I look back at the face in the frame. No memories of this man. Nothing. Not a flicker. I shake my head. The silent man shakes his head, too. I don’t trust him. I turn away, then back quickly, trying to catch him out.

I turn back to the Doctor. I shake my head again.

He folds his arms. He understands.

I open my mouth.

‘Blossom,’ I say. ‘Fruits. Fucking fuck! Blossom. Bollocks. I mean… blossom. Argh!’

5 (#ulink_43aa5940-4490-5d34-a92e-a3be849d60f5)

‘Because it’s bigger than you,

But you’re lighting a fuse

And you’re playing to lose

Because it’s bigger than you’

‘Tom? Tom? Sorry. Tom? Tom?’

‘Yes,’ I respond straight away.

‘You’ll be stationed with PCSO Bartu?’ says the man dressed as a policeman.

I turn to him and nod. He smiles back. Nicely. Nice guy.

‘Great. That’s great. Do I… Do I…’

The room waits for me to find my thought. Giving me supportive eyes.

‘Do I… have to have… a partner? I’ll… be okay. On my own, you know.’

The others look to the main man. He sucks in his bottom lip and wets it. His eyes flicker to the left. Then to the right. To the other six people seated either side of us in the locker room. Some men. Some women.

‘We’re going to put you with Bartu. Just for now. It’s standard procedure for anyone who’s had extended time off. Even if it’s only three months.’

No, it’s not. I’ve had time on my hands. I’ve been filling in any gaps of knowledge on all sorts of areas but particularly police procedure and neurology. I want to understand what’s happening to me and what I’m getting myself into. Above all, I want to be aware of those two things. So I’ve been researching. Voraciously. Every day, with a fire and will I’ve never had before. I use a program that reads to me. But I always read the first three words myself, I’m rigorous about that, even if it takes an hour. Then I let the voice take over and we learn together.

‘You don’t need to go on your bike either, until you’re ready. So Bartu will be keeping fit with you on foot or if you need it you also have access to a vehicle.’

‘I’ll drive. Let me drive!’ I shout.

They recoil a bit. No sudden movements. I remind myself. It makes the ‘normals’ tense.

‘I can drive,’ I say. Softly. Watering myself down for the room.

I’m now what’s called Preternaturally Sensitive. It means my inhibitions have receded due to injury to my frontal lobe. So if I want to say or do something, I usually do it.

You won’t find me shouting out swear words as with Verbal Tourette’s, which is a turning off of inhibitions as well as an enlarged tic-like propensity to say what shouldn’t be said. It’s just a new facet of my character. Not that I am psychiatrically different, as such. No, like Tourette’s, it’s not a psychiatric issue, but rather a neurobiological one of a hyperphysiological sort. Which is quite different. With me? Good.

This replacement of inhibition with drive arrived as if by magic. Soon after my first couple of meetings with Dr Ryans, I wanted out of there. Away from the hospital’s warm arms and succour. Not in a fearful way, I just had things to do. I felt charged. Like someone had put a new kind of battery in me.

After I eventually made it out, when they were satisfied that I could do things like document distinct memories and walk (not perfectly, I tend to drag my left foot more than I pick it up and good lord I’m not ready to ride a bike yet) I started devouring knowledge in a way I’d never even considered before the bullet. Doctor Ryans says I merely wanted to make up for lost time, to test my consciousness and attention span to see how much more it could do for me. To see whether, if I tried hard enough each day, if I laboured then slept and then woke and then laboured again, each sleep could take me closer to home. To the mind I used to have. That’s how Ryans put it, but I wouldn’t say it was that. I didn’t want to be the same as I was before. I wanted to be better. I felt somehow I already was.

‘Pre-bullet’ I was directionless. ‘Post-bullet’ I had a lust for the world. I started to feel sorry for the ‘pre-bullet’ me. Listless. An apathetic approach to the possibilities of the day. I was motivationally shambolic. ‘Post-bullet’ me could have him for breakfast.

The physio would come each morning. We would work. Then I would sit in front of my computer and use the programme to find gaps in my knowledge. Once my shopping was delivered I would make myself a new recipe I had found online that’d intrigued me.

I would learn more.

I would do my exercises.

I would defecate perfectly.

I would write a poem, or lullaby, or do a pencil drawing.

I would get headaches and cramps and fears.

I would ignore them.

I would learn more. Then I’d sleep.

I sleep less. I found I didn’t need as many revitalising hours as I had previously indulged in. Getting up before sunrise was now a regular thing. I like waking in the dark. It meant I could engender a routine. I could warm up before physio and make myself something with perfect nutritional value for breakfast.

I learnt about health and the body obsessively.

Did you know that a stitch when you run is caused by your diaphragm? It gets pulled around when you jog, so if it hurts take a slower, more even pace and longer smoother breaths.

Did you know that if your food wasn’t mixed with your saliva then you wouldn’t be able to taste it?

Did you know the average person falls asleep in 7 minutes?

Did you know that stewardesses is the longest word you can type using only your left hand when utilising a standard keyboard in the correct manner?

Did you know 8% of people have an extra rib?

I used to be an eight hours a night man or I was useless. I need only five and half now and they serve me better than my sleep ever did before. In my waking hours I feel more awake than I ever have.

I couldn’t read, my brain wasn’t letting me yet. But I could focus on the little things and block out the distracting thoughts. In short, I could listen like a motherfucker. Pardon my French. Lack of inhibitive reflex plus mild aphasia there: ‘impaired ability to speak the appropriate word for the scenario, or the one your brain is searching for.’ In other words, I send for a good formal noun, in this case ‘genius’, but by the time it comes down the chute some joker has switched it for ‘motherfucker.’ Apologies again.

I longed for things passionately, like I never had before.

I wanted to run.

I wanted to watch movies and fully understand them.

I wanted to climb remote exotic mountains.

I wanted mystery and love and mysterious love.

I wanted to be able to drive.

‘For the moment, it’s best if you don’t drive. Order from on high. Probably an insurance thing, something like that.’

I know he’s lying but I appreciate his tact. He has an upright stance. He has initiative. Gumption. I like him. I give him a thumbs-up.

A crease in his face tells me he’s not sure whether this gesture is an ironic manoeuvre. Little does he know I don’t have anywhere near the outward mental processing speed required for irony yet.

He moves on and says some more things with his mouth. I take my cheat pad out of my pocket and write. You see, I can still write, as the part of my brain that turns thoughts into symbols works fine, but curiously the bit that interprets those symbols back into words? Different matter. Pun intended.

So I know I won’t be able to read this back but the act of writing it down helps me commit it to memory. I observe. The others peer at me but I block them out with ease, with my genius focus. I write:

Upright stance. Gumption. Fair and balding. Wire frame circular glasses. Highly Caucasian.

On the upper left of his jacket, where his breast would be, are some symbols. A word I think. It starts with an L.

L. E. Then one I can’t make out, then an I, and it ends with another E. The process takes a while and my straining to establish the word at this point has become a spectacle, which everyone is pretending manfully not to notice.

LE_I_E. Lee? Can I call him Lee? Leon. Lean? Levine? Levine! I’ve heard that somewhere before. Ah. Of course. Levine. So that’s Levine. I remember him. I think he’s recently been promoted.

Levine. Or Upright-Gumption-Bald-Glasses-White-Face. As I will call him. In my mind.

I turn and see another man to my right, close to my head. He holds out his hand, luckily, because that means he might whisper his name. I may have seen him before, it’s quite possible. I’ll probably remember him. Because, you see, it’s not the remembering exactly I struggle with. No, it’s not that, it’s another thing.

‘Hey. I’m Emre Bartu. Good to meet you,’ he says with a wink.

Yes. He’ll do. I keep out my cheat sheet and start to write.

Bouncy. Kind. Black hair. Deep voice. Brown face.

I realise I haven’t said anything back to him. As is certainly customary. I think I just locked eyes with him and started writing.

Multi-tasking is hard so I have to stop for a second to mutter something pleasant-sounding to him.

‘I’m Tom Mondrian. Can you stay still please? I’m looking at your head.’

He smiles and does so. He nods, his eyes flicker to the side, which indicates he’s a bit confused by all this. Then he holds his pose like he’s having his school photo taken.

A thought hits me from nowhere that someone once said he was Turkish. I don’t know where I got that from but my mind has offered it to me as useful information so it’s best to follow it up.

‘You’re a Turkey,’ I say.

‘What mate?’ he says.

‘Sorry. I mean. You’re a Turkey.’

‘What?’

‘Sorry. Shit. I mean. You’re a Turkey. Ahhh,’ I shout, frustrated. Damn aphasia.

The room looks up for a second and I hold up my hand to apologise. They go back to talking about their beat, what they have to do that day, that kind of thing.

‘Sorry. You’re a Turkey. Shit! You’re… Turkish?’ I bend my voice at the last minute, it had taken so long to splutter it into the world I’d forgotten that it was supposed to be a question.

‘Yes, mate. That’s right.’ We nod. Agreeing with each other.

I’m pleased with this. I run the words over in my head.

This word pattern forms what is called a Feature by Feature Recognition Strategy. I slip the note back in my pocket.

*

The physio came to me every day but I had to go and see Dr Ryans twice a week. The journey itself was a good test and I’m sure he was aware of that. We went through a series of facial recognition exercises as that was his biggest area of interest. It was discovered I had prosopagnosia – an inability to recognise faces. Which is a particularly cruel word if you also have trouble reading.

We talked through strategies and the face cheat sheet was certainly the best. By far the most disquieting side effect of my accident is the inability to recognise my own face. Typically, Ryans also had a few methods to deal with this frightening daily occurrence – the part where I wake and scream because I don’t know who the man in my mirror is.

‘It’s suggested that success can be achieved by making your own image as distinct and memorable as possible. Prosopagnosiacs often choose to grow characteristic facial hair. But what works best, in fact, is when this is coupled with headwear, perhaps a bandanna or…’ He pauses, catching me mulling this over.

‘No offence, Jeff, but as well as having all my brain disorders I’d rather not dress like Hulk Hogan.’

Amazing that despite not being able to pick out my parents faces from a line up in Dr Ryans’ tests, I can picture Hulk Hogan clear as day. But then, he does have that characteristic beard and bandanna combo we prosopagnosiacs seem to really respond to.

‘Get a cat,’ he says as I leave.

‘Sorry?’

‘I’d advise you to get a cat. For a few reasons.’

‘I don’t like cats.’

‘It will like you. But you won’t come to rely on it. Soft companionship. That’s reason one. Understood?’

‘Er…’

‘You really hate them?’

‘I’m indifferent to them.’

‘Oh, that’s different. That’s fine. Here’s reason two: It’ll anchor you, by which I mean you’ll judge time better by its presence, it will remind you how you’re progressing in relation to it and therefore will stop you getting depressed.’

‘I don’t feel depressed.’

‘Well, you could well get depressed. Reason three: The stroking is nice. You’ll just fucking like it. Trust me. Get a cat!’

I sometimes think the sudden outbursts of swearing are in my imagination, but I think he’s just like that. He’s come direct from the wayward 1960s. His hair is kind of shaggy, his formal jacket sits awkwardly on his shoulders above his loose fitting slacks, like he was dressed by his mother this morning, but even the jacket itself is finding its place on his torso pretty inappropriate and is mounting a slow escape.

I’ve often seen him hurriedly extinguishing something in a drawer as I enter the room, his desk gently smoking as our conversation begins. His pupils a little dilated and the room smelling leaf green.

‘Okay. I’ll get a cat,’ I say.

‘And you can have it as what people call an emotional support animal. There are perks of this. For example, if you go on a fucking plane you can take it with you and have it on your lap. You’re allowed almost anything if it’s for emotional support. Big dogs for instance. One chap even got a small horse on a long haul.’

‘What? In the cabin?’

‘Yes. A tiny one, but it was still a horse. Listen, trust me, in my line of work I’ve seen far fucking stranger things than that.’

I leave. I get a cat. Now I have a cat.

*

Draw a line between the middle of your forehead and the top of your left ear. Make a mark directly in the middle of that line. Then make another mark one centimetre above it. That’s where the bullet went in.

Right there.

6 (#ulink_bae139af-4e96-541b-93f4-7bb2689aa1c5)

‘Dee. Dah dah girl dee dah, dah dah, my head…’

‘So… Stevens and Anderson are to follow up with the girl’s family. Bartu and Mondrian, you’re giving a talk at the school.’

‘What? I want to follow up the missing girl,’ I exclaim.

A hush. ‘I want’ isn’t a word combination that often gets an outing in the debrief room.

It’s been a big deal, me coming back so early. They wanted it for me. And for my part, I needed it; I couldn’t stay at home any longer.

Brains need other brains to develop. If I’m kept out in the cold, in exile, mine will start to recede before it’s even rehabilitated. People go mad when left in rooms with nothing but their own thoughts to haunt them. Inmates in solitary confinement, deprived of sensory stimulation, have been known to forge their own deluded realities, even see things that aren’t there and hear voices. Try not speaking to anyone for a full day when home alone on sick leave, and you’ll feel the chill the icy hand of madness leaves on your shoulder.

That’s a microcosm of where I am. That’s the narrow end of it, a fleeting taste of the mouthful.

But they need to know I can be trusted. They’ve shown a lot of faith in a man still trying to get a grip on the newly coloured world spread out in front of him, because in truth, I’m not sure whether I can be trusted or not. Sure, I’ll give it a crack, but I’m certainly not making any promises.

‘Me and Bartu will check up on the missing girl. Sounds interesting. Anderson and Stevens, you do the talk at the school. That okay?’ I blurt out.

If you don’t ask, you don’t get.

‘Err… sorry, Tom. That’s not really part of your remit. You get to do… other things. Community work, which in some ways… is the most… important work of all.’

My face seems to tell Levine everything he needs to know about the validity of that statement.

‘Look, a couple of months on the straight and narrow and they want to bust you up a bit. Get you on the force maybe. Fast track. You’ve been told this, right?’ Levine says.

‘Yes.’

‘There’s so much… good feeling around you, Tom. Good press. Good public err… you know. You’re well thought of, Tom. You. And your story. It’s… uplifting. So, you know…’

I’m not sure I do. I mean, I think he’s telling me to behave or I won’t get what I want. It’s been a long time since someone’s had to tell me to behave. I used to stay out of trouble, stay in the corners, under the radar. Not anymore it seems.

‘So the school for you today please, Tom. The school,’ Levine says.

‘Yep. Course. Yep, yep,’ I say, folding my arms and smiling at the rest of the team. Faces and faces staring back at me. Stubbly ones. Pink ones. Pale ones. Happy ones. Sad ones. I’ve no chance of keeping them all in my head. So I just smile.

We get up to go. I think about the missing girl. It interests me.

*

Emre is somewhere between twenty and thirty. I can’t do any better than that for you, perception is difficult.

But his physical energy, his spirit, if you can imagine such a thing, is by turns fifteen and forty-five.

He’s springy but with a coolness that belies his youth. He could have a high IQ. Or perhaps it’s a centred temperament that’s learnt. Maybe it’s a religion thing, but I don’t know what religion he is so it’s difficult for me to comment on that, but he’s definitely smarter than he looks. I decide to tell him that as we walk toward the school.

‘Hey, I think you’re definitely smarter than you look.’

‘Thanks. You’re pretty blunt. Do you know that?’ he says, observationally, no side to it at all.

‘Yes, I know that. Thanks,’ I say, politely.

‘Is that you? Or your brain?’

‘Is there a difference?’

‘Were you like this before the accident?’

‘Does it matter?’

‘No. But I’m interested.’

‘What was the question again?’

‘Were you like this before the accident?’

‘Ah yes.’

‘Well… ? Were you?’

‘Do you know what, Emre Bartu? I have absolutely no idea.’

I don’t like it when people call it an accident. We don’t know if it was an accident. Not yet anyway.

I prefer The Incident. Or The Happening. Or The Bullet.

I listen to our footsteps and think about people. People like to think their personality is separate from their brain, as if their personality is in the mind.

The mind, that thing that is the actual self, is presumably located somewhere above the skull, floating free of the brain’s complicated mush of blood, cells, flesh, neuroglia and wires. This ‘mind’ is unbound, simpler, and yet capable of far more complexity than the biology and flaws that pervade within the strait-jacket restraints of the human brain.

The brain holds people back: from finding the perfect words over dinner that will make our friends revere us as debonair and articulate. If only the brain could take some lessons from the mind, that reliable thing that is uniquely us and always right. The centre of our genius that no one understands.

All that is utter cocking fantasy, of course. But we can easily fall back into the idiotic grasp of these thoughts if not careful. If we don’t remind ourselves that we have nothing else to think with, but this miraculous lump that contains who we are completely and is all our best idiosyncratic parts.

When patients wake from strokes, and sometimes during them, they often describe not being able to distinguish themselves from the world that surrounds them.

Their arm is the wall.

Their head, a computer.

Their genitals are the trees and landscape outside the window.

This is reportedly often a euphoric feeling rather than a scary one. It appears to me that this is getting closer to a truthful condition than the general way of thinking. Not misled by the structures we have learnt to see, that define us as the protagonists and everything else as the scenery, these patients accept their place in the world in those moments, on a par with everyone and everything, comfortable with the fact that they are no more than their anatomy.

‘Normals’ think of themselves as beautiful hand-crafted originals that always know best, who will prevail even as their bodies fail them. They think their brain contains only facile learnt sequences that make it easier to put your trousers on or cut a cucumber. If only they knew better.

One day I’ll fill Bartu in on all this. But for the moment I keep this enlightenment as an advantage over them all. Everyone is on a need to know basis, and I’m the only one who really needs to know.

My inner thoughts work so much faster than my mouth. I can think it all exactly as I want it. But it doesn’t come out quite that way yet. I speak in imperatives, everything slow, but with exclamation marks. I can virtually see them hang in the air after every sentence.

‘This is the school here, right? Really doing this are we?’ I say.

These words pierce the silence we’ve been in for a good five minutes. Bartu would probably have preferred this trip to be filled with witty repartee, rather than the dead air of one man thinking and the other waiting. He’ll have to forgive me. I don’t do patter easily yet. I don’t do off the cuff. Sometimes I forget to get out of my head.

A car with blacked out windows passes and my eyes follow it away.

He considers my question. Luckily, I’m pretty comfortable with silence as it’s the condition in which I’ve lived the majority of my life up until this point. Even pre-bullet.

‘Look, don’t worry. You don’t have to speak, if it’s uncomfortable or difficult. To the kids I mean,’ he says in an almost whisper.

‘It’s not uncomfortable. It’s just boring.’

‘Fair enough. I’ll do the talking.’

‘We’re not teachers. We’re officers of the law.’

‘We’re not really officers of the law.’

‘We’re community support officers of the law.’

‘We’re part of the uniformed civilian support staff.’

‘Same diff.’

He laughs. A genuine one, I think, not for show. People are sometimes afraid to laugh at me, or with me, but not Emre Bartu.

We look at the school, it’s a tidy set of red bricks with a pair of pointy roofs. It also contains a playing field full of my past sporting failures and the scene of many rejections and one good kiss.

Her name, Sarah, flashes into my head and I pat my brain on the basal ganglia for the remembrance. Without the ability to show me Sarah’s face, it merely reminds me that she was pretty, freckled and mysterious, and that I hung around to wear her down. And that sometimes people told stories of the strange things she did. But I can’t recall any of them.

Old sights, sounds and smells allow you to go down neural pathways you don’t frequently use. The resultant sudden rush of seemingly lost memories is what causes strong emotions in such places.

I observe this feeling and let it pass through me. None of my teachers will be here, the turnover is pretty fast. Things change swiftly in cities. They change double swift around here. This is a foreign land.

I won’t announce that I am alumni. I’m not sure they’d care anyway. Some bloke whose biggest claim to fame is getting shot in the skull. I’ll wait till I’ve done something more auspicious with my broken head before I bring it back here and try to hold it high around the corridors.

He brings out ‘the bag’. I’ve had to handle ‘the bag’ once before, in a training session, but today he has ‘the bag’.

‘I’m going to do the talking. You be a presence,’ he says.

‘I can do that.’

‘Good. Any questions? Anything you need?’

‘Yes.’

‘Go on.’

‘Right. The girl that went missing, did she go to this school?’

‘Forget about that,’ he says, scolding me just enough.

‘Okay. But did she?’

‘Err… yes. I think so,’ he says in a sigh.

‘You think so? Or know so?’

‘I know so,’ says Emre Bartu.

He wants us to go but I can’t walk and think smoothly yet. My stillness means he can’t move. It’d be rude.

He waits. I pause. I think. Then speak.

‘Okay. I’m going to ask about her.’

‘Who?’

‘The missing girl.’

‘No. Please don’t.’

‘Why is that?’

‘It’s being handled elsewhere. It’d seem… odd.’

‘I don’t mind that.’

‘Yes. But others would. Others are assigned to it.’

I shrug and nod at the same time, committal and non-committal all at once. We both stare at the school, he grips the bag, I blink hard.

‘It would be interesting. Quite interesting. I’m interested,’ I say.

‘Please, don’t. Just trust me, no one wants you to do that.’

‘Okay. I won’t,’ I say.

He touches me on the shoulder.

‘Good man.’

He turns as he bites his bottom lip, a tense mannerism that intrigues me already. It’s always the little things that intrigue me.

‘Ready?’

‘Yes,’ I say, my movements getting smoother all the time. I can feel myself growing already, spreading out to encompass the space the world outside my room has provided for me.

‘Good. Come on then,’ he says as he walks.

You just have to say you won’t do something. That’s what they want. Little compromises. Promises. Words.

It’s as easy as that.

We sign our names and put on those badges with the safety pins attached that ruin jumpers and would do unfathomable things to a face.

Then we’re in.

7 (#ulink_3f774101-94c6-51f5-9f7b-aea680397abd)

‘Dreams, keep rolling, through me

Dreams of you and I,

Dreams that drift far out to sea

Why does my baby lie?’

Being back here is sinister. The hallways hum with spectres. Dr Ryans said he didn’t think I’d suffer any amnesia or losses, as the bullet didn’t seem to rupture anything where my memories lie, but then the brain is unpredictable. I hear the song of distant thoughts as we walk under halogen strip-lights to the school hall. Traces of said things in half remembered classrooms pass by.

It’s like a dream and not the good kind. Forced into your old school hall, dressed as a policeman, with a bullet in your brain. I look down and expect to see my penis but only my trouser crotch stares back at me.

Bartu sees me staring at my own crotch and when I raise my head again our eyes meet and I smile. He does, too, trying not to let on how much I concern him.

He makes conversation with the head of year. She is called Miss Nixon. She is all brown and grey hair and clothes she’s had a while. I write down a brief description on my face cheat sheet.

She is Caucasian. Has church-going hair. Wears dangly earrings.

The last one is her most distinguishing feature, in fact. If she took them off, she’d disappear.

I start to hum a song I made up called ‘Dreams’. When my senses were kicking back in and my brain was repairing itself I found I had the overwhelming urge to make up little lullabies. Conjuring a tune and putting words to it was one of many exercises I set myself. I didn’t write them down but I won’t forget them, there must have been hundreds.

‘Dreams are rolling through me…’

The cleaning fluid smells the same. Even the cold crisp door handle’s touch against my skin sings deep-held memories back to me. Along with fears that I might stumble through the wrong door and end up in a classroom some miles away, where Gary Canning pushes my would-be fiancé up against the blackboard and her back slowly rubs off what was once written on it.

A group of kids pass us on our left, keeping their heads low, as if the sight of everything above shin level depresses the hell out of them. One of them has an unmistakeable birthmark, so distinctive that even I can’t forget it. He pretends he doesn’t see us, but he can’t fool me. Eli cold shoulders us like we’ve never met. That’s life in your home town. These instances that come and go. As fate blows us into each other’s paths like debris in the updraught.

That childhood kiss with Sarah drifts into my mind, then blows away, escaping through my ear.

When we get to the hall, its unmistakeable chafed parquet flooring under my feet, the kids are waiting and Emre Bartu wastes no time.

He claps his hands, a surprisingly effective attention drawing tactic that turns their chattering heads towards him.

‘Hello Year Eleven! My name is PCSO Emre Bartu and it’s a real pleasure to speak to you today. We’re usually out on the street, you may have seen us about, so at this time of year it’s just nice to come in and get warm.’