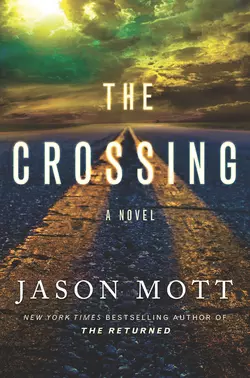

The Crossing

Jason Mott

New York Times bestselling author of The ReturnedStay and die, or run and survive.Twins Virginia and Tommy Matthews have been on their own since they were orphaned at the age of five, surviving a merciless foster care system by relying on each other. Twelve years later, the world begins to collapse around them as a deadly contagion steadily wipes out entire populations and a devastating world war rages on. When Tommy is drafted for the war, the twins are faced with a choice: accept their fate of almost certain death, or dodge the draft. Virginia and Tommy flee into the dark night.Armed with only a pistol and their fierce will to survive, the twins set forth in search of a new beginning. Encountering a colorful cast of characters along the way, Tommy and Virginia must navigate the dangers and wonders of this changed world as they try to outrun the demons of their past.With deft imagination and breathless prose, The Crossing is a riveting tale of loyalty, sacrifice and the burdens we carry with us into the darkness of the unknown.Readers love Jason Mott:“This is a deserving read and a solid addition to this genre”“A well written book.”“This was an intriguing novel, with a premise unique in the dystopian books I’ve read.”“an engrossing read.”“It's adventuresome, but also intellectually complex”“highly recommended”

Stay and die, or run and survive.

Twins Virginia and Tommy Matthews have been on their own since they were orphaned at the age of five, surviving a merciless foster care system by relying on each other. Twelve years later, the world begins to collapse around them as a deadly contagion steadily wipes out entire populations and a devastating world war rages on. When Tommy is drafted for the war, the twins are faced with a choice: accept their fate of almost certain death, or dodge the draft. Virginia and Tommy flee into the dark night.

Armed with only a pistol and their fierce will to survive, the twins set forth in search of a new beginning. Encountering a colorful cast of characters along the way, Tommy and Virginia must navigate the dangers and wonders of this changed world as they try to outrun the demons of their past.

With deft imagination and breathless prose, The Crossing is a riveting tale of loyalty, sacrifice and the burdens we carry with us into the darkness of the unknown.

JASON MOTT is the critically acclaimed and New York Times bestselling author of The Returned, which was adapted for a network television drama series. A Pushcart Prize nominee, Jason holds a BA in fiction and an MFA in poetry. He currently lives in North Carolina.

JasonMottAuthor.com (http://www.JasonMottAuthor.com)

Also By Jason Mott (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

The Returned

The Wonder of All Things

The Crossing

Jason Mott

Copyright (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Jason Mott 2018

Jason Mott asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9781474083669

Praise for Jason Mott (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

“Spellbinding.”—People

“[A] poignant story of loss and love.”—Bookpage

“Lovely… A revelation.”—Bookreporter.com

“White-hot.”—Entertainment Weekly

“Exceptional…Riveting.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Compulsively readable.”—The Washington Post

“Extraordinary.”—Douglas Preston

“Beautifully written…Breathtaking.”—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“A deft meditation on loss.”—Aimee Bender

“Ambitious and heartfelt.”—The Dallas Morning News

“A beautiful meditation on what it means to be human.”—Booklist, starred review

“An impressive debut.”—USA TODAY

Contents

Cover (#ucfb6bb9b-b8a2-5128-b077-5fd447df87b2)

Back Cover Text (#u7afec1d0-934d-5d4f-9cf3-ca9465cf3791)

Booklist (#ub89e3bcd-f526-553d-9cb7-859e7753fdbd)

Title Page (#u579969fe-f321-5af3-a8b5-1e93efb949eb)

Copyright (#ue0b65b85-e7cc-58a4-83f2-9d626746cba2)

Praise for Jason Mott (#u776700da-83d2-5088-938d-9086a5bffd60)

LAUNCH (#u3bb0bc01-1def-5302-acaf-f1c8c95063f3)

PROLOGUE (#u3042fee2-a3a6-5b82-a5d7-9580036f5dff)

ESCAPE VELOCITIES (#u82196ef6-2ab3-5963-91b3-e867a81c48b0)

ONE (#ufe2babea-70e3-5345-9769-6b5cccbc40b6)

ELSEWHERE (#u6439c7b6-f211-51ad-a8c6-4e0b374ba96f)

TWO (#ucc1ad625-2597-5e3b-b2c9-122bc1853f90)

To My Children (#u8a89aa0f-ec02-518c-a4b4-126560a26e8b)

THREE (#ud938cfa6-e309-579f-adaf-cffc69865baa)

ELSEWHERE (#u8751fe61-8441-5750-b2d4-c2ec4b0a224d)

FOUR (#uc7832bc2-b75e-5d89-8337-cfed48c8756a)

To My Children (#u8e9e8c60-ba10-5b38-ac92-aae0505e903b)

FIVE (#ub36864db-ff97-54ef-8314-63669fd38470)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

To My Children (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

SEPARATION (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

To My Children (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

To My Children (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

To My Children (#litres_trial_promo)

CELESTIAL ENCOUNTERS (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Virginia (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELSEWHERE (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Tommy (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

EUROPA (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUNCH (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

(#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

The whole world was dying but still everyone made time for one last war. The Disease had entered its tenth year and the war had entered its fifth and there didn’t seem to be any cure in sight for either of them. Some people said that because of the nature of The Disease, the older generation, seeing that their end was finally near, decided to settle all the old scores. One final global bar fight before last call.

The world had already lost twenty percent of its population by the time Tommy and I began our trip. The Disease took the old—killing some, simply putting others into a long, soft slumber—and the war took the young and everyone else tried to lose themselves in whatever they could: drugs, alcohol, sex, science, art, poetry. Everyone had impetus and direction now that everything was falling apart.

When it all first began, Tommy and I were too young for the war and far too young for The Disease, so we only walked in the shadow of it all, watching and waiting for our turn. Our parents were already dead and we didn’t have any other family. We’d never live long enough to catch The Disease, so we viewed it with a detached interest and sympathy.

The Disease started in Russia, but because Russia tends to be tight-lipped about what happens within its borders, it’s been difficult for anyone to say just how long it had been happening before the rest of the world found out about it. The UK was the first country beyond Russia to notice the outbreak. It began in a retirement home in London where one morning the staff went to their patients’ rooms to find all of them asleep and unable to be awakened. Within hours there were reports coming in from other countries about the extremely elderly falling asleep and never waking.

The Disease garnered a lot of different names in those first frightening weeks: The Lullaby, The Long Goodnight, Sundowners Disease. The last one was meant to make fun of the elderly. After all, those at the end of life were expected to pass away eventually. So for a while, the world was concerned, but not alarmed. It wasn’t until The Disease had been quietly shutting the doors on the oldest of the population that someone at the CDC noticed a decline in the average age of The Disease’s victims. Something that began affecting only those in their midnineties and above had progressed to affect those about five years younger. Then the world watched as, over the next couple of years, the average age was reduced even further.

The Disease was coming for everyone. It would begin by emptying out the nursing homes, then progress to the retirement villages, then on and on until, eventually, it would hollow out the office buildings, the nightclubs the youth had once filled with reverie until, one day, there would be no one alive old enough to reproduce. Not long after that, whatever children left would turn out the lights on humanity by drifting off into one long, peaceful slumber.

The world would not end with a bang or a whimper, but in a restful sigh.

Staring down the barrel of that future was what sparked the war. As people panicked they began to blame others. And that blaming donned a coat of nationalism. Russia was the primary target in the beginning since that was where The Disease had begun. Before long, the war spilled over from its borders and into the rest of the world.

Now, five years later, America was the last uninvaded country on the planet. But that wouldn’t last. The average age of victims of The Disease had reached sixty—the age of most politicians and military officials. The war was losing its direction and ambling on the shaky legs of enlisted men and women who didn’t see any point in fighting when there was a disease coming for them. So the government turned back to the draft.

The Disease was too far away for seventeen-year-olds to really understand or fear. Youth has always been a haven for invincibility, and this was no different. The papers from the draft board went out, scooping up boys and girls in its bloody hands. And one after another they went, they died, and the world grew a little lonelier.

Though it all felt far away from me and Tommy, I knew, of course, that it couldn’t last.

Our parents had been dreamers. Our mother was a teacher and believer in things magical, like newspaper horoscopes and the ability of whispered fears to manifest in a person’s life. Our father believed in magic of a different kind. He was a writer and, sometimes, amateur astronomer. His magic was a distant moon named Europa.

He fell in love with it at an early age and then passed that love on to my brother and me. He could never know where his obsession with a small ice rock located over three hundred million miles away would lead his children. Like the stars led our father, the memory of our father led my brother and me.

For me, our journey started before I was even born, in letters my father wrote to me and my brother. For Tommy, it all started with a letter from the Draft Board.

For three hard days my brother failed to find the words to explain his impending death to me. With furrowed brow and taut jaw he tried to find a way that, when he laid the news out in front of me, its hardness would be sanded off like a pebble rubbed smooth and glossy over the life of an old river. We were all each other had. Brother and sister. Twins, seventeen years from the womb. How I’d get on without him once he was dead, he didn’t know.

In the end, because he had never been any good with words, my brother never did find out the right way to say it. After failing to come up with an alternative he only handed me the brown envelope, with his head hung like a penitent child—even shuffling his feet a little, suddenly making himself smaller than he had been in years—and he said in a low voice, “I won the lottery, Virginia.” Then he smiled, as though a smile meant a person was actually happy.

I took the envelope, knowing immediately what it was. Everyone knew what the draft notices looked like. They were a spreading plague, a dark shadow that came for friends and loved ones, took them away and never brought them back. The war was going from bad to worse. As if war had ever done anything else.

I only looked at the letter that would eventually take my brother to his death. I pointed to the awkward font that printed his name in that excited, prize-winner’s way, clucked a stiff laugh and said, with no small amount of derision: “Terrible. Just terrible.”

ESCAPE VELOCITIES (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

ONE (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

In the middle of a pockmarked crossroads someone had painted the word PEACE in six-foot-tall white letters on the edge of a crater. The night was late and the road black, but the word—what was left of it—caught the starlight and glowed. The lettering was sharp and formal, placed by a steady hand. Someone had cared. About the letters. Maybe even about the word. So I couldn’t quite understand how PEACE had met such a bad end out here in the middle of nowhere.

And it truly was nowhere.

If you’ve never been to Oklahoma, you should go. It’s a beautiful place, a place where everything seems to stand alone. Lone trees strike out of the distant horizon, so far away from anything it makes you wonder how a lone seed could ever have gotten there in the first place. In Oklahoma, far houses stand and watch over grassland oceans that shimmer in the dim moonlight. In Oklahoma, the wind has long legs that carry rain clouds on stalks of gray. In Oklahoma, the sun rises far, reigns high, and then comes close in the evening and sits beside you until you doze off on the front porch.

Oklahoma is a place where loners have formed a community. It’s a place where people are both alone and together at the same time, like Tommy and I always were. It’s a special thing: always having someone with you. It gives you legs to stand on.

I was seventeen when Tommy and I ran away from the war and started on what would come to be our last trip together. Seventeen’s an odd age. Too old for dreams, too young for reality.

It was a hard January when this all happened. Any promise of spring was far off as I walked the frozen highway. The ground was still locked from cold and every particle of snow had been swept away so that there was only brown, barren earth. The cold swelled up around me like static on an old television. Now and again the starlight seemed to exhale and the wind raced over the empty winter fields and passed through me hard enough and frigid enough that it frightened me.

To keep my hands from trembling, I turned them to fists buried inside my pockets. To keep my teeth from chattering, my jaw was locked. The muscles ached from holding station. I stomped my feet to keep my toes connected to my body. Now and again they drifted off on their own accord. I was never quite sure if they would return.

But even with all of this, there was beauty. Several hours before, I watched as the failing light went dark and a fistful of bare winter trees jutting up from the sides of the road swung from being thick gray arteries to thin purple veins to black silhouettes that might have been calligraphy of some exotic language, punctuating the black cursive of the small highway scrawling through the countryside. Then the last of the light went away and all the ways the trees had looked became just another memory I would always carry in me.

I was alone that night...sort of. I hadn’t seen a house since passing through a small, sleepy town before sunset, where the one stoplight on Main Street flashed off and on. Yellow in one direction, red in the other. Even though lights sometimes burned inside the bowels of the homes—a mixture of trailers and two-story farmhouses with clapboard siding and old paint peeling like psoriasis—the town looked left behind, a city desiccated by plague. Everything was weathered and empty, ready to be filled by story and myth. I could imagine dragon eggs hidden in storm shelters, elder gods tucked away in attics. I’ve always had a tendency to drift off into imagination.

In the window of a darkened diner a sign—lit garish red by the town’s single stoplight—declared God Blesses the War. Directly across the street, almost like a bookend, another sign hung in the window of a home and alleged God Left. So The Disease Came. I still don’t know exactly who was right.

At one point I almost knocked on the door of one of the houses. A large gray-and-white affair with a tire swing dangling from an evergreen in the backyard and a late-model car parked in the front. I thought I saw someone in one of the upstairs windows. I stared up at them and they stared back down at me. It wasn’t until my eyes adjusted that I realized it was only a teddy bear placed in the window, looking out, keeping diligent watch the way only loyal stuffed animals can.

For a moment the feeling of being watched caused me to think it was him. He was coming for me and he wouldn’t stop. That’s just who he was.

My palms were sweating and my heart was a frightened bird beating against my rib cage. All because of a teddy bear standing watch.

I waved at the guardian, laughed at myself and walked on until the houses stopped appearing and the town sank into the earth behind me. The moment was relegated to history and memory, which, for me, have always been one and the same.

Tommy and I called it “The Memory Gospel.”

The Memory Gospel was simple, really: I remember everything. Truly and honestly everything. Every second of every day. Every conversation. Every place I’ve ever been. Every person I’ve ever met. Every word I’ve ever said. Every news report I’ve ever seen. Every letter of every sentence of every page of every book I’ve ever read. Every shaggy tree that slanted at an odd angle and was dappled by the dying sunlight in a way that might never again repeat and made a person say to themselves “I hope I never forget this. Never ever.”

I don’t forget any of it. Not a single moment. I carry all of it inside me.

Every laugh. Every schoolyard bully. Every foster parent who tried. Every social worker who failed. Every time I’ve stood outside and looked up into the sky and counted the stars until there were tears at the corners of my eyes because I remembered—as if I could ever forget—that my parents were still dead and would never be able to come and stand beside me and take my hand and point up to the night sky and say to me, the way people did in movies, “It makes you feel so small, doesn’t it?”

My memory was, is, and always will be, immutable.

The Memory Gospel is the one thing in my life that I can believe in. It’s always with me, filling me up and hollowing me out all at the same time, like the way a person can stand before a mountain in the winter and see the light spilling over its craggy shoulders and understand, in that brief instant, that life comes and goes and one day we all will. Like you’re part of something and a part of nothing all at once. The Memory Gospel is all-encompassing and inescapable. A forest I can neither get lost in nor find my way out of.

And so I’ve come to consider myself the chronicler of the last days of the world.

I kept walking with my head down and my shoulders up and the past swirling above my head. I wished for a peaceful, silent cold—the way it sometimes happened in the nights when the snow fell like dust and you woke in the morning to a world you knew but didn’t recognize, like a childhood friend you haven’t seen in decades. But the wind stayed hard and unreasonable. It swept down off the mountains in a roar that shoved me forward and almost put me on my face a few times. I always managed to catch myself just before I fell. Eventually I decided to let the wind help. It was heading in the same direction I was, after all. Why not let it push me along? Why not let it carry me off into The Memory Gospel...

...I’m five years old and hanging upside down in a crashed car. The seat belt holds me tight across the waist and my ears are ringing and there is the sound of water falling outside and Tommy is on the ceiling of the overturned car crying and looking around. “It’s going to be okay,” my mother says, and suddenly I’m standing in the middle of the road staring down at the word PEACE and I’m terrified and hanging upside down again and I’m in a foster home and I’m attending the funeral of my parents and the social worker is saying, “It’s going to be okay,” and I’m squeezing Tommy’s hand and staring up at a black, starry sky and staring up at the ceiling of the overturned car and Tommy is still crying and there is blood trickling from his head and our father is dead and our mother is saying, over and over again, “It’s going to be okay... It’s going to be okay...” and her voice is softening with each recitation and I’m standing alone in the world and the wind is cold and I am seventeen and still trapped in my five-year-old self watching my parents die and I don’t want to see it so I close my eyes...

...like fists and pushed the memories away.

It’s like I told you: I have a tendency to drift.

I stopped walking. When I had finally clawed my way out of what was and into what is, I opened my eyes and looked up at the stars.

Andromeda was brighter than usual that night. One trillion stars burning, raging. Reduced by time and distance to little more than a pinprick of noiseless light. That’s how memory was supposed to work. A narrowing down. A softening that made it possible to let go of unwanted or painful memories. Maybe that was why I liked astronomy as much as I did—and still do. It proved that with enough time, even the brightest stars burned out. Everything faded away eventually.

But I understood that, because of distance and time, when you saw a star you only ever saw the way it used to be. Even the sun was eight minutes in the past by the time you saw it.

“Andromeda,” I began, smothering the memory of the car crash with bare, calm facts. “Officially designated as NGC 224. Coordinates: RA 0° 42m 44s | Dec 41° 16.152' 9". 2.537 million light-years away. Two hundred twenty thousand light-years across. 1.5 × 1012 solar masses—estimated. Apparent magnitude of 3.4.” On and on I continued. Definitions of mass, luminosity. It was a spiral galaxy and I quoted the composition of each of the spiral’s arms. Fact after fact after fact, pulled perfect and undiminished from memory.

I built a levee with each fact, and the recollected dead receded back into their holding places.

“Ten more miles,” I said, looking off down the cold, empty, dark road ahead. “Seventeen thousand six hundred yards. Fifty-two thousand eight hundred feet. Six hundred thirty-three thousand six hundred inches...and a partridge in a pear tree.” I sang the last part. Badly. But the starlight didn’t seem to mind.

I took one final look up at the sky. I found Jupiter. I found its moon Europa—nothing more than a whisper of light so difficult to see it made my eyes hurt and I wondered if what I saw was real. But whether I actually saw Europa or only imagined seeing it didn’t seem to matter. To some extent, we are all solipsists. I started walking again, heading toward Florida and the last shuttle launch of human history.

* * *

I had just passed the crossroads where PEACE was written when the headlights rose out of the far darkness behind me. It had only ever been a matter of time. So I stopped and waited for what was coming.

The headlights approached in cold silence, then the silence shifted into what was almost the sound of applause as tires sizzled over the cold pavement. A chill raced down my spine as the blue lights atop the car flashed into existence.

The police car stopped in front of me. The headlights glared bright enough that I had to shield my eyes. The car shifted into Park and sat idling for a moment. A small plume of steam rose from the exhaust, effervescing into the darkness. The door opened. Booted feet thumped onto the pavement like punctuation at the end of a grim declaration about life. The lights still shone too brightly for me to see who had stepped out of the car, but I didn’t need to see in order to know that it was him.

“Got pretty far,” he said finally. “I’ll give you that much.” His voice was as hard as steel, like always. Because of the headlights, he was only a deep shadow and a deeper voice, like thunder come to visit in the late hours of the night. His breath steamed from his lips and expanded into a small anvil head cloud above him.

“I could explain to you why it’s important, but you wouldn’t understand.” There was arrogance in my voice and I knew it, but I didn’t try to curb it. At this point, there was no turning back, nothing to be said that would undo what was already done. I knew, better than most, that time’s arrow only moves forward. “I’m going to be there to see it,” I said. “And I’m never coming back.”

He stepped away from the car door and walked out in front of the headlights. I counted each one of my heartbeats, if only to keep myself calm. He was tall and broad as he had always been. His hair cropped close as a harvested field. The backlight of the car’s high beams turned him into a monolith, eternal and omnipotent. Something to be worshipped, if only for its cruel disinterest.

He looked around, scanning the open field of darkness surrounding us. Then he sighed. “You Embers are something else,” he said. Then he spat. “You’ve had your fun. Now, where is he?”

No sooner had the words left his mouth than the blow landed against the back of his head. A tremble went through his body and he slumped to his knees with a pained groan. Then Tommy was there, standing behind him, his fist trembling.

“Run,” Tommy said, as our foster father fell unconscious at his feet.

ELSEWHERE (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

The hardest thing was convincing herself not to be afraid of falling asleep. Each and every evening she watched the news and watched talk of The Disease. Her friend over in Alamance County had come down with it. Fell asleep on the sofa one night and then, when morning came, nobody heard from her until her children found her. And this was back near the beginning. Her friend was eighty-seven years old, but spry for her age. Still, spryness doesn’t do anything to repel the unexpected. But wasn’t that the way it had always been?

And now nearly ten years had passed and The Disease was creeping ever closer to people her age. So, like many people of a certain age in this world, she figured that the best thing she could do was to get herself away from everybody. She went down to the store and bought herself as much food as her dead husband’s pickup truck could carry and she came home and loaded up the house and then went back and filled the truck up again and, this time, she also picked up as many sheets of plastic as she could. And duct tape and disinfectant and even a gas mask—which were slowly becoming all the rage even though nobody knew whether or not they would do any good.

When all was said and done she had everything she needed to live for at least a year. Yeah, it might be a year of eating potted meat and crackers until she was blue in the face, but Lord knows there were worse things in this world.

She lived far enough outside of town that she could live the type of life she wanted. The farm was big and old and her dead husband’s pride right up until the day he dropped dead, still sitting atop the same tractor he’d bought when they first got the farm. He’d been dead for nearly twenty years and she was glad that he didn’t live to see the world get to where it was: the killing, the dying, the slow fading away of everything that the whole damn species had spent thousands of years building.

No. He was always too softhearted to be able to stand for such a thing. If that heart attack hadn’t done him the pitiful kindness of taking him when it did, he would have turned on the news in the world today and died from a plain old broken heart.

She thought about her husband a lot in those first few months of living alone, isolated from the rest of the world. Mostly she thought about him as a way to keep from thinking about everything else that was going on around her. She stopped turning on the news in the mornings because it did nothing but let in the worst parts of the world. Nobody said anything good anymore.

And so she would get up at the crack of dawn—always thankful and amazed and terrified to have woken up at all—and piddle about the house before time came to go out and tend to the garden and she would think about her husband and maybe she would hum some song that he used to love—he’d always been partial to Frank Sinatra—and, as the weeks stretched out into months, maybe she would even talk to her dead husband even though she knew good and hell well that he was dead and she wasn’t the type to believe that the dead could hear the breath of the living. But she did it anyway.

Some mornings she talked to him about the past. She told him about the children they’d never had and how she, finally, after all these years, could say that she was glad that they’d never come along. “I just couldn’t live with myself if I had to watch those pretty blue eyes worry over this world,” she said. The only answer the house gave back to her was the gentle clunk-clunk-clunk of the grandfather clock in the living room that never kept the right time but that she wound up anyway because, even if it wasn’t doing a good job, it was important for everything in this world to have a purpose.

That old clock made her think about her own purpose. What was it? Her purpose?

What was a woman without purpose?

What was anyone without purpose?

She asked her dead husband that one night when she woke up from a bad dream—a dream that she’d fallen asleep and been unable to wake up from it. Her palms were sweaty and her long hair matted to her brow and her cheeks were slick with tears, and the words trembled out of her lips like a newborn foal. “What’s my purpose?” she asked.

And her dead husband did not answer her back, even though she sat and waited to hear his heavy, soft voice for over an hour with the darkness and the clunking of that clock down below counting off its irregular and inconstant seconds.

That was the night that she made a promise never to go to sleep again. She’d stay up for as long as she had to, until The Disease came and went and burned away the rest of humanity and all that was left was her and then, by God, she’d know what her purpose was. She’d have the answer she’d been waiting for and she wouldn’t wake up at night sweating and calling out for her husband because, in the end, she couldn’t go on like this: afraid of sleep and afraid of life both at the same time.

She didn’t make it a full two days before falling asleep again.

She tried everything to stop it from happening. She drank coffee until it made her head hurt and her chest tight. She went back to watching the news, hoping that the fear the news gave would make her more able to sit up in the late hours and not fall asleep. The news told her about seventeen new cases of The Disease that had been found around the county and that did give her just the right amount of terror that she needed to stay awake for a little while longer.

But she was an old woman and, try as she might, she could feel the sleep walking her down, as steady as that old clock in the living room and, just before she finally fell asleep—a sleep that she would never wake from, something she knew in the pit of her stomach—she thought she heard her husband’s voice one more time. He said a single word: “Love.”

And her final thought before she fell into the deep, timeless slumber of The Disease was that her question had finally been answered.

TWO (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

For what felt like an eternity, I was unable to breathe. Seeing Jim Gannon at Tommy’s feet, I realized I hadn’t really expected for it to work. Gannon was six-foot-two and built like a bad dream. All angles and muscle. More animal than man. And that was before you took into account the police uniform that filled him out with cold authority and made you nervous about crimes you hadn’t committed.

When I finally did breathe again the air rushed into my lungs, air so thick you could drink it, choke on it if you weren’t careful. I felt light-headed and gritted my teeth until the feeling went away.

Standing there in the cold darkness with our foster father lying at Tommy’s feet, I thought of all the ways it could have gone wrong:

Tommy could have stumbled on the uneven earth as he climbed up out of the darkness along the edge of the road, stumbled just loud enough for Gannon to hear him and turn and draw his pistol and squeeze the trigger and put an end to everything. It wouldn’t have been anything other than a reflex action for Gannon. Law enforcement training taking over. But it still would have ended Tommy’s life. Just a sudden flash like a lightbulb bursting, then the long darkness.

Or he could have gotten caught in the headlights of Gannon’s car long before he noticed them. It had been my idea that Tommy follow along at a distance, away from the road, buried in the outer dark, orbiting like some phantom planet. “It won’t be long before he catches up,” I had said. “Do what I tell you and we’ll be okay.” And so he did.

Only now that Gannon was unconscious on the cold, deserted road did Tommy and I laugh.

The laughter was fleeting, but wonderful, like a meteor slashing across the night sky.

“We’ve got to get him out of the road,” I said.

Tommy flinched. He looked up to see me still standing there in front of the car. “I told you to run,” Tommy said, his voice steady and even.

“We’ve got to get him off the road,” I repeated. I was already jogging around and opening the rear door of the police car.

Tommy reached down and took the pistol from Gannon’s holster.

“Take the bullets out of it and throw that away,” I said.

He placed the gun on the highway. He fumbled through the pockets on Gannon’s belt. “Hold these,” he said, handing me the man’s handcuffs. “Hurry up,” he barked.

I took the cuffs. “You don’t need these,” I said.

Tommy rolled Gannon over and, after a few awkward moments, managed to pull him up off the ground and lift him over his back in a fireman’s carry. He’d wrestled off and on growing up. Most of the schools in most of the foster homes he and I had been shuffled through over the years had wrestling programs in some form or other. He’d actually managed to get pretty good at it. The physical side of it—all of the strength and muscles required—were just a matter of deciding to do it. The mental aspect required a lot of thought and Tommy wasn’t much of a thinker, but he had gotten pretty good at that too. He could always tell what his opponent was planning. He always knew, milliseconds before it happened, when someone was going to shoot their hips forward or try to spin out or go for an underhook. And his mind reacted to it all on its own. He didn’t have to think about it. It was one of the few things in his life, maybe even the only thing, that had come naturally to him. If he’d ever stayed in a single school for more than a season, maybe he would have gotten recruited by some college. Maybe in one of those places where wrestling was a pastime and boys like him could be someone people admired.

But he never did stay anywhere longer than a season and so he never had gotten really good and there were no college recruiters looking for him. The only person looking for him was the unconscious foster father he carried on his back.

Just as Tommy got Gannon to the car, I opened the door and there, sitting in the back seat and as quiet as a corpse, was the Old Man, Jim Gannon’s father himself. He’d had a stroke years ago and been confined to his body ever since. The doctors said that he was aware, but paralyzed and unable to speak. The most he ever did was blink, and even that came only on rare occasions.

Gannon had dressed him in khaki work pants and a flannel shirt and a pair of soft-soled nurse’s shoes. The Old Man didn’t seem to register me as I opened the door and took a moment to stare at him.

“What is it?” Tommy asked.

“It’s the Old Man.”

“What?” Tommy looked past me. “Is he sick?” Tommy asked. “The Disease?”

“No,” I said.

Gannon groaned a little, in the early stages of coming around.

“Give me the handcuffs,” Tommy said.

“You don’t need to handcuff him,” I replied. “Just shut the door. It can only be opened from the outside. He won’t be able to get out.”

“Give me the handcuffs, Virginia!”

“You. Don’t. Need. Them,” I said, laying each word out like a brick. Then I turned and tossed the handcuffs out into the darkness. “Don’t be so simple.”

Tommy was deciding whether or not to run out after them when Gannon, suddenly back to his senses, grabbed his arm. “Tommy...” Gannon said, groggy and slow.

Tommy snatched Gannon’s hand away and shoved him to the far side of the back seat. Then he bolted back just in time for me to slam the door closed, locking the man inside. “Tommy!” Gannon called. He looked out at the boy through the window, a firm calmness in his eyes. “Tommy...open this door.”

Without a word Tommy walked around to the front of the car and picked up the pistol that still lay in the middle of the street.

“I told you to throw that away,” I said.

He tucked the gun into the pocket of his coat. “If you want it, come over here and take it.” His voice was a hard, low warning, something that would let his sister know that for all of my intelligence, despite that flawless, unbreakable memory of mine, he was powerful in his own right. He’d saved me. Not for the first time, and not for the last.

“You’re welcome,” Tommy said.

“It was my idea,” I replied.

“You’re still welcome.”

Then we stood there in the dark and the cold, looking at the man trapped in the back seat of the car. It would be up to me to figure out what to do next. And it would be up to Tommy to do whatever needed to be done. Just like always. I would get us both to Florida in time to watch the launch and then, after that, I wouldn’t need him anymore. And, at the same time, he wouldn’t need me anymore. He’d go off to the war. Do his duty the way his draft notice demanded. He would die.

It was the only way things could turn out for us, no matter how much we wanted it to be different. We couldn’t know that at the time, but years later, the past would be immutable, and I would have to live with it, perfectly preserved in the halls of memory. And, years later, I would be able to speak for my lost brother, to see this trip the way he had seen it. The last great gift he gave to me.

* * *

Tommy hadn’t been a smart boy and he would never become a smart man. But that wasn’t what really bothered my brother. Neither was it that The Disease or the war would one day find him. The latter, in fact, I’d almost say Tommy always saw as something inevitable. Maybe even welcomed.

Tommy told me once that he could never be like me. Not even if he tried at it every single day for five hundred years, cloistered away like a monk. He’d only ever come up short. He said he’d known that for about as far back as he could remember—which wasn’t very far. To be sure, he had memories. As many as most other people did, he figured. He remembered important stuff: the first girl he’d kissed, the first time he got in trouble in grade school, a smattering of song lyrics, a handful of lines from movies. If he was supposed to show up somewhere at a certain time on a certain day he could, for the most part, hold that much in his head. Maybe he’d have to check the calendar again and again in the days before and tell himself, “Now, don’t forget!” But that’s how it went. That’s how it was with everybody.

Everybody except me.

In the last few years before our final trip together, perhaps sensing his growing unease, his body no longer looked like a copy of mine. He had shot up four inches above me and filled out wide and strong. He was all muscle and intention. In spite of the changes to his body, he and I still shared much of the same face. Sometimes when we were together I could look at Tommy and find myself overcome with a feeling of both loneliness and togetherness all at once. Being a twin was cruel in its own way. From the moment you were born you were let in on the dark secret of humanity, the thing that no one wants to know about themselves: that a person is both unique and, at the same time, mass produced. And therefore no better than anyone else.

Hell of a thing for a child to have to grow up knowing.

By the age of twelve Tommy was already being told that he was handsome. Not cute, the way people told it to the other boys his age, but handsome, the way people spoke of grown men. He was athletic. Strong. Everyone knew he would grow up to do something physical. Maybe he’d be a boxer or a wrestler, but never a bully. And then, assuming he lived long enough, the architecture of his physique promised that he could be the type of man that made people feel safe when they had every reason to be afraid. Maybe after he’d been wrestling for a few years he would become a firefighter. Policeman, perhaps. He had a good smile. “A soft smile,” people told him, girls especially. Maybe he’d become a doctor with a stern voice but a soft smile, the kind you trusted to save you no matter what harm you had brought upon yourself.

But that was before things started falling apart. Back when young people like us still thought they could grow up to be something other than what they would come to call us: “Embers.” It was our job, or so the joke went, to be the last remnants of the flame that had burned so long. And, like all Embers, to eventually burn out.

From the time we were five Tommy and I had been shifted from foster home to foster home. Nothing to do with The Disease—that was still years away. But simply because our parents had already died and left us and we became “difficult” children. Maybe it was just the way we were. Or maybe it was because, after their deaths, the only thing we had to remember our parents by was a stack of letters that I’d read once and burned the next day.

After the letters were gone there were only Tommy and me, and we were always together. Only twice had anyone tried to separate us. Tommy had been the one they wanted.

The first time, no less than a day after Tommy had gone, I ran away from the group home in which he had left me behind and found his new home. It wasn’t difficult. Just a matter of getting the records from the social worker’s paperwork when she wasn’t looking. I snuck into Tommy’s room at night, took his hand and left. We made it a day and a half on our own before we were found. The couple who had taken him in gave him up after that and the two of us returned to the same foster home we had been in before. We were together again.

The second time it happened—again, he had been the one the adoptive family wanted—we were thirteen. We ran away again and made it alone together for almost a week. During that week, Tommy thought of a dozen good reasons why we should keep going. He had this idea of picking a direction—any direction—and simply going until that direction ran out. The world was big and we could get lost in it. And even though we would be lost, we would be together the way we had always been.

“We’re too young to keep running,” I said. “Nobody searches for anyone as hard as they search for lost kids.”

“We’re not kids,” Tommy said, and in just saying so I realized how young he sounded. “They’ll break us up again if we go back, Ginny.”

“Don’t call me Ginny,” I answered. “It’s what you called me when we were babies. And I’m not a baby anymore.”

We were standing beneath an overpass just after sunset, listening to the sound of the cars racing by in light rain, their tires sizzling like bacon. When the big trucks went by overhead there was the calump-calump-calump of the expansion gaps in the concrete.

“We’ll go back and I’ll tell them what they need to hear to make sure they keep us together,” I said. I tucked my hands in my pockets and stared off into the distance. The entire conversation was only a formality to be endured before it led to its obvious conclusion.

Tommy’s face tightened into a knot. “Dammit, Virginia!” he said, leaning hard on my name after planting the flag of “dammit.” Curse words were still new to him and still had power. “We can find somewhere to live.” We could both feel the momentum of words building inside him, like a shopping cart just beginning to rattle down a steep hill. “We can go off and make a home. We’re each other’s home when you really stop to think about it!” He belted the words out. He opened his arms, proudly, like a carnival barker making his greatest pitch.

He searched for words that would undo me, but found only the empty breath inside his lungs. If he tried to press me he knew I could always bring up facts and figures, numbers and math enough to break down anything he said. I could recite articles verbatim about the survival rates of runaways if I wanted. True stories of children found dead. Statistics about how badly everything could go for us if the world so decided. I could crunch the math in my head and rattle off the probabilities: such and such a chance of getting kidnapped, such and such a percentage of turning to drugs or prostitution or anything else. On and on, I always knew how to break down any resistance he ever had to anything.

Tommy looked at me, his face soft and afraid and frustrated all at the same time. His mind reached for something to say but his lips knew the fact of futility. Only I could change it. Only I could let him win the argument that he so desperately needed to win.

And he knew—we both knew, and hated—that I wouldn’t let him win.

Rather than fight it, rather than try to make the case for the things he thought we should do, he conceded. Tommy’s life was always easier when he just did what I wanted.

“So be it,” he said.

“Tommy?”

“What?” he answered, sighing the word as his body slumped upon its frame, resigned to defeat.

“They’re never going to break us apart,” I said.

“Then why do they keep trying?”

I walked over and wrapped my arms around him. He was outgrowing me already and my arms had to work to surround him, but the work was rewarded by the feeling of my brother captured, like some splendid and frail animal, in my arms. I had to protect him. It was my job.

“We won’t ever be separated,” I said.

“But—”

“I promise, Tommy.”

“You can’t know that, Ginny. Mom and Dad said they’d always be here too.”

Tommy’s body shuddered and I knew that he was crying. He wrapped his arms around me, if only to keep me from seeing his tears the way boys and men are known to do.

“Mom and Dad haven’t left,” I said. “They’re in me. In The Memory Gospel. And they’re in you too.”

“I can’t remember like you can,” Tommy said, almost as an apology.

“It doesn’t matter. They’re in you. We’re together. A family. And we’ll always be that.”

“You promise?”

“Just as sure as my name’s Ginny.”

We stood for a long time, holding one another, and the world passed us by.

...calump-calump-calump...

Like a beating heart fading into nothingness. And when the sound went away, when the world had drifted off into silence, we were still there, together. The way it would always be for my brother and me.

After that we went back to the foster family who had taken him in and, just as before, the family didn’t want Tommy unless it was without me. So we found ourselves lost in the system. But at least we were lost together.

Four years later, we were seventeen and running away again, but this time, we wouldn’t go back. The launch in Florida wouldn’t wait for me the way the war and death would wait for Tommy.

In three days, when this would all be over.

So be it.

(#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

To My Children (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496),

We could do nothing to stop the towers from falling. We could do nothing to stop the workplaces from being shot up. And when the shootings spilled out of the office buildings and into the schools, we could do nothing to stop that either. The government began watching everyone because we had given them permission. Climate change. Bankers. On and on and on. All day every day the news outlets came into our homes—slipping in through the waves and cables, screens and surfaces that bound us all together. The television became a hole in the ice through which horror shambled each night, the way it used to in old black-and-white movies. But in those movies dying was all corn syrup. Back then, the world only pretended to be after us and, inevitably, the thing we feared went away, born into darkness on a tide of end credits.

But now the dying we saw on TV was real. The world grew more thorns with each sunrise, tightened in a little closer with each sunset. And all the while we watched. We stared at the news and shook our heads in dismay. We wept. We sat up at night, sleepless and fretting. Asking ourselves, over and over again: What right did we have to bring children into this world?

Your mother and I went back and forth for years. We felt we had a duty to wait for things to get better. A duty not only to you, but to everyone else. This world, in whatever form it takes, is a product of us all. We forge hope or sow terror. We dole them out in measurements of our own choosing.

But still, it’s a big world. I was just a small-town newspaper writer. She a science teacher. How much could we really do about anything?

At some point in your life, you’ll want to know where we were when everything changed. It’s a hard question to answer, like trying to find the moment when a little hill of rocks became a mountain. It happens suddenly and all at once, like a lightning strike, and after the flash fades, you turn to see that your home has burned to the ground.

While there are a dozen days in which the world changed, and some of them I will tell you about, I’ll answer your inevitable question about the moment when things went from the way they were to the way they would become:

We were in North Carolina visiting your mother’s parents on the day the towers fell. Your mother, your grandparents and I all spent the morning huddled together in front of the television, watching it happen, just like everyone else. Your grandfather, a stoic man by nature, sat unmoving in his chair for hours, letting what was happening wash over him like floodwaters sweeping over a headstone. When he did finally speak, all he said was, “I’m sorry.”

By sunset we were all wrung out. Raw and frayed at the edges. We wanted to sleep, but it was early yet and, even beyond that, we knew that it would be a sleepless night. So your mother and I went for a walk. Her parents lived in a small community on the Intracoastal Waterway where large houses smelled of seawater. Small cars steered gingerly over the earth, guided by retired hands. The ocean thinned out into tendrils of tributaries only a stone’s throw from the bedrooms of children.

The streets were empty because the television was still full of tragedy. Your mother and I walked the vacant roads alone. Sometimes the wind carried the sound of sobbing from nearby houses. We pretended it was the sound of laughter. A lie, but one we felt it was okay to tell ourselves.

Eventually we found a sandy road leading off into the woods. It led to a collection of abandoned buildings. Once upon a time, it had been a summer camp of some sort. Square, concrete buildings held empty wiry bunks, rusting and half-reclaimed by underbrush. A large, high-ceilinged classroom stood at the center of the complex, covered in graffiti and shaggy with kudzu that trembled like grasshoppers when the wind blew.

We moved through the empty, forgotten buildings, stepping slowly, detached from everything, even ourselves, like ghosts. When we had seen enough we followed the edge of the property and found that it led to the ocean. The sun was setting behind a wall of clouds. Just before it disappeared, it flared, shifting colors, from beautiful to ominous, the way a goldfish swimming in a bowl can, with the proper play of lighting, suddenly become an apostrophe of blood.

Then the sun was gone and the moon rose above the water.

As we stood and watched, the light from the moon poured down onto the ocean water. The water swung from black to gray to silver. And then it continued to change. From silver to turquoise to, finally, a glowing, electric blue. I can’t remember ever seeing that particular shade of blue. And I have never seen it since. The water looked like lightning, lightning that coiled itself into waves, only to flatten and bubble against the shore, still glowing. Just then, your mother and I could believe we had stumbled upon another planet. Some near-dimension mirror-image earth. A horror-beauty of a world where planes leveled buildings and lightning became water at moonrise.

Wordlessly, your mother stripped off her clothes and, without testing the depths or the dangers, dove in. She disappeared and reemerged, glowing like a glacier. “We don’t know what this is,” I said.

“It’ll be okay,” she said.

I wasn’t sure I believed her, but I followed anyway. There was never any choice. Not really.

We swam into this new world.

Later that night we told your grandfather what had happened. “Heaven’s Tide,” he said. “You don’t know how lucky you are to see such a thing.”

After a bit of research, I learned that it was just a strain of bioluminescent algae. A completely natural occurrence that had happened before and would happen again. The only thing different about this time was that your mother and I had been there to bear witness to it. It was our old, familiar world all the while. It had only chosen to show us something rare and wondrous.

“It’s not all horrible,” your mother said to me later that night. It was her way of saying, “Let’s try a family, even in this world.”

It would be years before we succeeded. In the interim the world continued to change. I responded by writing these notes, letters, whatever they are. I write them for you, in case it all falls apart. I write them for myself, to say that it doesn’t have to. I write them to prove that the world has always been this hard. I write them to prove that the future was always meant to be a promise, not a threat.

THREE (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

“There are bad ideas, and then there are bad ideas,” Gannon grumbled from the back seat. The sick Old Man beside him said nothing, because that was the way it always was with him.

Behind the wheel Tommy clunked the car into gear and steered it gently off the highway. I sat in the passenger seat, pointing ahead through the window at the path we should take. “Head toward that tree line,” I said.

“Those trees won’t hide a car,” Gannon said. He chuckled a little, then hardened his grin, as though he hadn’t meant to find anything funny just now. He looked over at his father, checking to be sure that he was okay, then turned back to Tommy. “Hell of a right hook you’ve got there.” He pressed his hand to the back of his head and checked his palm for blood. “But you always were strong as an ox, weren’t you?”

“Can you just stop talking?” Tommy asked.

“It doesn’t matter if he talks,” I said. “Don’t listen. Just get us over behind those trees.”

“It’s a hell of a world we live in, I suppose,” Gannon said with a sigh, as though resigning himself to something. Then he leaned back and closed his eyes and hummed so quietly that the sound was only there for a moment before being swallowed up by the lope of the engine as the car bobbled up and down over the rough-hewn field.

“I’m not the one who sent you that draft notice, Tommy,” Gannon said. “You’ve already let her get you into more trouble than you had to, son.”

“He’s not your son,” I said.

“You’re just a strong back to her, Tommy,” Gannon said, as though I hadn’t spoken. “She’ll never make it without you and she knows it. That’s the reason she’s dragging you along on this. Don’t you dare think it’s anything different than that. I’m the only person that can make this right with the draft, son. I’m trying to help you. They don’t treat dodgers too good.”

“Yeah,” I replied, “they send them off to war.”

Tommy let out a stiff laugh.

Though the ground was frozen and hard now, the winter had come with fits of warmth that had unlocked the earth into a bog only for it to refreeze days later, misshapen and awkward, like a heart riding the highs and lows of love and hate over the course of a long marriage. Here and there the ground dipped, long and deep as a starving belly, and the car was thrown down into a depression and all Tommy could do was hold tight to the steering wheel and keep his foot on the accelerator, uncertain whether or not we would be able to climb out of the hole in which we found ourselves. But Tommy was good behind the wheel and he got the car over to the trees that jutted out, dense and bare, on the far edge of the field.

“Right there,” I said, pointing ahead.

“I see it,” Tommy said, aiming for where the trees were thickest. There was a scrub of green pines and bare oaks. Not much, but enough to make the car difficult to see from the road when the sun finally came up.

“You kids really should think this over,” Gannon said. I thought I heard genuine concern in his voice, but whether it was for us or for himself was hard to say. As the car plunged into one final dip that sent us all bouncing, Gannon grabbed his father to steady the man. “It’s okay, Pop,” he cooed. “I got you.”

Tommy pulled the car to a stop and put it in Park. “Now what?”

“Leave it running,” I replied.

“What about poison?” Tommy asked.

“What poison?”

“Carbon dioxide.”

“Carbon monoxide,” Gannon corrected him, turning and looking at me through the thick Plexiglas divider. “He’s afraid we’ll suffocate while we’re sitting here waiting to be found,” he continued. “He’s got a right to be scared. It’s bad enough that you’re locking a sick man like my father in here, but if something happens to me while I’m waiting—anything at all, even if I have a damn heart attack from boredom—that’s manslaughter for the both of you. If you’re lucky. But they won’t let you have luck. Not with a dead cop on their hands. So they’ll swing for the fences. Try you both as adults. Murder. First-degree. ‘With foresight and malice.’ That’s what they’ll say.”

“Is that true?” Tommy asked.

Even I wasn’t immune to what Gannon had said. He’d managed to paint a picture in my mind—Tommy and me in a courtroom, on trial; Tommy would get the harder sentence because that had always been his lot in life; they’d send him to the electric chair and put me in prison; but they wouldn’t keep me there on account of how smart I was; they’d figure some way out for me on account of how I was special; that had always been my lot in life.

I walked on water. Tommy only choked on it.

“Just do what I told you, Tommy,” I replied. “We’ll leave the heat on medium and crack the windows. He’ll be fine. I promise.”

Tommy nodded in assent. He switched off the headlights and set the heater temperature as he had been told.

“Good,” I said. “Now get out.”

“Why?” Tommy asked.

“Just go, Tommy. I’ll be right behind you.”

Tommy stared at me. “I’m not going to do anything,” I said. I rapped my knuckles against the Plexiglas dividing the front and back of the squad car. “Couldn’t even if I wanted to. And you’ve got the gun, after all.”

“That’s right,” Tommy said, his voice full of sudden authority. “...that’s right.” Finally he opened the driver’s door and stepped out into the cold.

I turned in my seat, looking back on Jim Gannon. “Once the sun comes up it won’t take them long to find you. It’ll be a little embarrassing, so you’re welcome to tell them whatever story you want about how you wound up here. If I were you, I would say it was a prank.”

Gannon barked a sharp laugh. “A prank?”

“Yep,” I replied. “Just the local cops having a little bit of fun with you. You can say that you and them go way back. You just happened to run into them as you were passing through, on your way home from a law enforcement training seminar. That’ll explain why you were three states outside of your jurisdiction in your squad car and uniform.”

“Jurisdiction doesn’t apply with runaway children,” Gannon said. “But you already know that, don’t you, Virginia? You’re the smart one.” He slumped in the seat and checked the back of his head once more to be sure it wasn’t bleeding.

“Just say that they were some friends of yours and this was their way of being funny. They put you in the back seat of your own car and left you out here. It’s believable.”

“You got one hell of a mind on you,” Gannon replied. “But you already know that.”

“And he’ll be okay,” I said, looking at Gannon’s father.

“Are you asking me or telling me?” Gannon replied.

I looked out the car window at Tommy. He was standing just beside the car, watching our conversation.

Gannon’s eyes followed mine.

“Just let us go, Jim,” I said. My voice was softer than I had planned. There was a levee inside me that was on the verge of breaking all of a sudden. I didn’t know when it had begun swelling—I’ve never been particularly good with emotions. The energy it takes to keep all of the memories at bay tends to push down the feelings connected with those memories. It’s the only way that someone like me, who lives as much in the past as they do in the present, can exist without reliving everything again and again. So I learned to keep my feelings at arm’s length, but the problem with that is that they always eventually push in, suddenly and without warning. “Just go back home and let Tommy and me have this trip. And once it’s over...” I hesitated, then pushed on. “Once it’s over I’ll talk Tommy into coming back. It’ll be like nothing ever happened.”

“You just don’t get it, do you?” Gannon said. “He showed me his papers. He’s already overdue. That means they’ve already put him on the dodge list. That means jail first and then the war. But if I bring him back, I can help soften that. I come from three generations of lawmen. My name counts for something. I can smooth all of this out for him. Make it so that, when he goes off to fight, he does it with honor. The way he’s supposed to. There’s a principle at work here.” Gannon clucked his tongue. “The thing that amazes me the most is how proud Tommy was when he showed me that letter. Never seen him so proud. Like getting drafted was the best thing that ever happened to him.”

“Living was the best thing that ever happened to him,” I said. “I’m just trying to keep that going for as long as I can.” Then I opened the door before any more could be said and stepped out into the cold, leaving Gannon alone with his father and, perhaps for the first time in his life, powerless, in spite of all the instruments and ornaments of the Law.

* * *

Go back far enough and you’ll find that Jim Gannon came from a long line of policemen. He called them “lawmen” on the night when he sat me down and recounted to me the names and stories of the three generations that had come before him. He had never called them lawmen before. But once he was finally convinced that I truly did remember everything I ever saw or heard, he brought me into the living room and sat down in front of me with an old scrapbook filled with photos and news clippings and recounted to me all the stories he could remember having to deal with his father, William Gannon Jr.; his grandfather, William Gannon Sr.; and his great-grandfather, Thomas Gannon. “All good lawmen. Each one of them,” he said.

It took him a full hour and a half to talk about what was important. There was the story of how his great-grandfather had come over from Europe and immediately gone out West, back before the West was settled, back when the Indians hadn’t yet been treatied into submission. And Tom Gannon, seeing the way things needed to be if this country was going to work out, took up the badge as a United States marshal. Years later, when his own son shunned being a marshal but took a fancy to the art of sheriffing, Tom was only slightly upset about it. And when William Sr. passed on his badge to William Jr., it was already decided that, when Jim Gannon was born, he would take up the mantle. But then Gannon’s father had a stroke when he was young and never recovered and a new sheriff won the election. Gannon hadn’t been old enough to run and now, fifteen years later, he still hadn’t managed to get beyond being a deputy.

Something in Gannon’s voice told me that maybe he actually hated his job.

“At least I’m still a part of the way things used to be,” Gannon said proudly. “There’s honor in that.” He took a deep breath and stared at me. He sat with his back erect and his chin thrust forward, as though he were posing for a picture. “You make sure you remember that part,” he said.

And, of course, I did remember that part. And all the other parts as well. I remembered the way he looked a little afraid when he talked about his not yet being made sheriff. I remembered the way his voice quickened when he talked about the sudden decline of his father—the way a child speeds up their pace as they pass an old abandoned house whose walls and gables have become nothing more than an empty husk. I remembered everything, with unrelenting clarity. To hear Jim tell it, his father had been a smiling, confident man. The type of man that other men wanted to be. The type of man Jim Gannon wanted to be.

And then, one day, that man was gone and all that was left behind was an invalid.

No matter how much he took care of the man, I’m not sure Jim Gannon ever forgave his father for that.

When Gannon had finished speaking, his wife and Tommy were pulling up in the yard. Gannon got up in a hurry and returned his scrapbook to his bedroom and came back out. “No need to talk to them about this,” he said to me in the solid, familiar voice I hadn’t heard in an hour and a half.

“I hadn’t planned to,” I replied.

And then, in a whisper, just before the front door opened and his wife and foster son came in, Gannon said, “Thank you.”

He had been like every other foster parent in the beginning, back when Jennifer was still with him. Back when The Disease was becoming more aggressive and the war seemed like something that might come to an end just like every other that had come before it. The two of them couldn’t have any children on their own—his fault—and so they decided to adopt and with him being well-off in the police force, it wasn’t too hard to make happen.

Everyone was trying to have children back then. The population of people over eighty had dwindled and those in their seventies were beginning to go. Back then there were still theories about being able to stop it. And some people say that’s what really started the war: the hope that some other country knew something about The Disease and was keeping it to themselves, hoping to outlive the rest of the world. Pregnancy rates tripled in those first years. Everyone hoping to fix the end of people by simply making more people.

And for those who couldn’t have their own, adoption became the fix. That’s how Tommy and I found Gannon and Jennifer. They came to our group home that day wearing their best Sunday outfits and smiling with the pleased euphoria of people in magazine ads. They’d both been told about how special I was and Jennifer had made it a point to say that “All kids are special.” At which point Tommy looked over at her with something akin to pity in his eyes and said, matter-of-factly, “That’s bullshit.”

Jennifer laughed a nervous laugh, and eventually Jim joined in and it wasn’t long before the laughter wasn’t nervous anymore. It was as good of an introduction to foster parents as we had ever had. Not that it really mattered. We were fifteen by then. Jennifer and Jim would be the last stop before we were too old for the system.

Over the next two years I watched Jim Gannon harden for reasons no one in the household seemed to be able to understand. He came home after work and talked a little less each day. Mostly he settled in front of the television and heard what it had to say. When the news wasn’t talking about The Disease it was talking about the war. And Gannon seemed interested only in the war.

Night after night he watched the reporters wearing bulletproof vests atop polo shirts as they hunkered down inside bombed-out buildings. They yelled about “total destruction” or “total resistance” while gunfire clattered like microwave popcorn somewhere off screen. Now and again they covered their ears and pressed their heads against the ruined floors of faraway war zones and they waited, mumbling to themselves, trying to look both brave and terrified all at once. Then there would be an explosion big enough to make the camera shudder. Maybe followed by a cloud of dust. Then the reporters would lift their head from the sand and look around with bewilderment and say, “Thank God. That was a close one.”

Every day Gannon was there watching. Sometimes he gripped the arms of the chair beneath him until his knuckles went white and his face reddened because he didn’t know he was holding his breath. Then he would realize and the air would rush into his lungs and he’d have to go outside for a smoke to calm down.

Jennifer would go out to him sometimes. I listened from the upstairs window as Jennifer begged Gannon to tell her what was wrong. Begged him to seek help for whatever it was. Begged him to “come back to me.” She even took time to blame herself for their inability to have a child and fix the world like everyone else was trying to do.

None of it worked, though.

He grew harder.

He drank more.

They drifted apart.

Sometimes when he was drunk he would fly into a fit of rage. Thundering voice. High-flying hands that threw dishes and put holes in drywall. And when the rage was over he would retreat to his wife’s bedroom door and knock, gently, like a child, and whisper, “I’m sorry, Jen. I’m sorry, okay? Just open the door. Please.”

And Jennifer, because she was a soft woman capable of forgiving anything, always opened the door and let him in. Then I would sit in my bedroom, usually with Tommy not far away, and I would listen while Gannon slumped to his knees like a sack of potatoes, sobbing apologies into the late hours of the night. All the while his wife would whisper—the soft sound of her voice drifting through the walls like an incantation—and her whispers would be full of forgiveness and something more. Absolution maybe.

I had once asked Jennifer why she forgave Gannon the way she did. “Because,” Jennifer said, “the heart can break and break and break again, but then turn around and love like it’s never known how.”

Jennifer held out hope for her and Gannon’s emotional resurrection. But I knew better.

If this had all happened when I was younger, I might have been inclined to lie awake at night worrying about the fate of my latest set of foster parents. But The Memory Gospel was full of foster parents whose relationships didn’t last. Foster parents who had taken in foster children in the hopes that by filling the empty places in their home they would fill the empty places in their hearts. That’s all children really were when you got right down to it, I figured: just a person’s attempt to create someone who loved them wholly and completely, from birth. Someone who would carry that love forever.

Children, in the end, were gods of our own design. And when you couldn’t build your own god, you called social services and had one delivered. But I was tired of being someone else’s therapy.

It was during one of Gannon’s outbursts a few months ago that I made the decision that Tommy and I should run away.

“To Florida?” Tommy asked. It was late and Gannon was in the living room screaming and Jennifer was in her bedroom refusing to let him come in. The house trembled and shook, but continued standing.

“To the launch,” I replied.

“This is that whole Jupiter thing again, right?” Tommy asked.

I sighed a long, slow, damning sigh. I would have to explain it all yet again to my brother. “Not Jupiter,” I began. “Europa. One of Jupiter’s moons.”

“Still don’t care,” Tommy said.

“They’re sending a probe up there that might find life.”

“They won’t,” Tommy replied. He was lying on the floor, staring up at the ceiling as we talked. Whether he genuinely didn’t believe in what I was telling him or whether he just wanted to frustrate me, I couldn’t decide, but the latter was the one that was working the most. “And no,” Tommy said, “I don’t need you to explain the math to me about how they actually might find something there. That whole Frank’s equation of whatever.”

“The Drake equation,” I corrected him.

“The Bobby equation. The Joe equation. The Captain America equation. I don’t care what it is,” Tommy said. “It’s not going to happen.”

“I don’t know why I bother,” I said.

“Because I make frustration fun,” Tommy said. Then he smiled a self-satisfied smile.

“Do you remember Dad’s letter?”

“Nope,” Tommy replied, almost before the question could be asked.

“He said, ‘Even back then I knew that Europa was important.’ Do you know when people first had the idea that there might be life on Europa?”

“Nope, but I’m sure you’re going to tell me.”

“As far back as 1989,” I said. “That’s when the Galileo mission was launched and sent back all that data in 1995 that showed there might be an ocean under the surface. Dad was just a kid back then, younger than us, but I bet he heard about it and fell in love with Europa immediately. He knew it was special. He knew we’d have to send a probe there one day to find out. He always knew.”

“Good for him,” Tommy said. He rolled over onto his side, tucked his forearm beneath his head and closed his eyes. In the living room the sound of Gannon’s yelling was starting to subside. He’d be asleep soon, and then Tommy would fall asleep, but never before.

“Let’s do it for Dad,” I said.

“Dad’s dead,” Tommy replied. “He’ll never know whether we do it or not.”

“We’ll know,” I replied.

“I’m not going,” Tommy said. There was finality in his voice, like a door being closed. “And if I don’t go you won’t go.”

He was right, of course. And I knew it.

So that night, while Gannon descended from shouting to slurred mumbling to that final, incomprehensible bit of soft gibbering that always swept over him in the moments before sleep, while Tommy was on his side, falling asleep, I began being buried in The Gospel:

...Tommy is twelve years old and wants to be a magician and I know that he won’t be any good at it but I sit patiently as Tommy stands in front of me with a cape made out of a foster father’s jacket and a top hat that is nothing more than a baseball cap and Tommy clumsily holds a deck of cards and shuffles them back and forth in his hand and he has forgotten to say the magic words and he has forgotten everything else so that when he holds up the seven of hearts and asks, “Is this your card?” I say to him, “Yes!” even though it isn’t my card and Tommy, because of his knowledge of his own weakness with memory and planning, doesn’t trust that he has chosen the correct card and so he turns it around and looks at it and then looks back at me and his eyes ask me to confirm whether or not he has chosen the right card—because he knows that I will remember what he doesn’t and he has come to trust The Memory Gospel and trust what I tell him to be true—and he stands waiting, never looking more like a child than right now, and he asks a second time, “Are you sure this was your card?” and without hesitation I say to him, “Yes, that’s it,” and Tommy smiles stiffly and doubts himself and his lack of memory even more and I know that, because of this one moment, he always will and so I decide, right then and there, to always be the keeper of not only the past, but also the future...

ELSEWHERE (#u1a514c9e-e573-5827-9d52-3a19530cf496)

He was checking on his father every single day and, when he was honest with himself, he didn’t know how much longer he could keep doing it. They had never gotten along. He’d always been a burden to the Old Man—as least, that’s how it felt to him—but now with things going the way they were in the world, the good thing for him to do was to make amends before the end came in that soft, quiet way it was coming these days.

It had been his girlfriend’s idea. “Make up with your father,” she said. And she said it in that gentle, movie-of-the-week way of saying it. The way a person says it when they have no idea what they’re asking of someone.