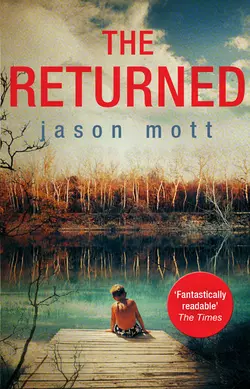

The Returned

Jason Mott

A world where nothing – not even death – is certainA family given a second chance at life.Lucille Hargrave’s son Jacob has been dead for over forty years. Now he’s standing on her doorstep, still eight years old. Still looking for her to welcome him with open arms.This is the beginning of the Returned.Praise for Jason Mott‘With fine craftsmanship and a deep understanding of the human condition, Jason Mott has woven a tale that is in turns tragic and humorous and terrifying’ - Eowyn Ivey, Author of The Snow Child ‘Could be the next Lovely Bones’ - Entertainment Weekly‘Fantastically readable’ - The Times‘Gripping’ - Shortlist'Mott tackles some big themes here, especially the vagaries of spirituality, and scores with one of the most emotionally resonant works in many seasons' - Essence Magazine'It will…make you question what it means to be human and what you'd do in a similar situation'-The Sun'Get in early before the hype begins' - Star Magazine'The Returned transforms a brilliant premise into an extraordinary and beautifully realized novel. My spine is still shivering from the memory of this haunting story. Wow.' -Douglas Preston, #1 bestselling author of The Monster of Florence'A deft meditation on loss that plays out levels of consequence on both personal and international stages. Mott allows the magic of his story to unearth a full range of feelings about grief and connection.' - Aimee Bender, New York Times bestselling author of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake'Mott brings a singularly eloquent voice to this elegiac novel, which not only fearlessly tackles larger questions about mortality but also insightfully captures life's simpler moments… A beautiful meditation on what it means to be human.' -Booklist

“Jacob was time out of sync, time more perfect than it had been. He was life the way it was supposed to be all those years ago. That’s what all the Returned were.”

Harold and Lucille Hargrave’s lives have been both joyful and sorrowful in the decades since their only son, Jacob, died tragically at his eighth birthday party in 1966. In their old age they’ve settled comfortably into life without him, their wounds tempered through the grace of time.... Until one day Jacob mysteriously appears on their doorstep—flesh and blood, their sweet, precocious child, still eight years old.

All over the world people’s loved ones are returning from beyond. No one knows how or why this is happening, whether it’s a miracle or a sign of the end. Not even Harold and Lucille can agree on whether the boy is real or a wondrous imitation, but one thing they know for sure: he’s their son. As chaos erupts around the globe, the newly reunited Hargrave family finds itself at the center of a community on the brink of collapse, forced to navigate a mysterious new reality and a conflict that threatens to unravel the very meaning of what it is to be human.

With spare, elegant prose and searing emotional depth, award-winning poet Jason Mott explores timeless questions of faith and morality, love and responsibility. A spellbinding and stunning debut, The Returned is an unforgettable story that marks the arrival of an important new voice in contemporary fiction.

The Returned

Jason Mott

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For my mother and father

Contents

Chapter One (#u47b0133b-8e06-5ee4-9ae6-92410b15f769)

Kamui Yamamoto (#u15e98bff-c273-502e-8d95-3c88ab142300)

Chapter Two (#u0ee9b1d4-07ab-56e7-9edd-dbbc165cc66f)

Lewis and Suzanne Holt (#ua88b52ff-4b04-54d6-bac5-8b207128ffd5)

Chapter Three (#ue1de4b52-a1e0-5a44-9d1e-845106c25e24)

Angela Johnson (#u5fcf199b-ced2-514a-9dda-b1bb29e5eff5)

Chapter Four (#udc72391c-135e-589c-be4b-f63a9e2c4434)

Jean Rideau (#u726417fe-992e-594f-9b21-974af9d64650)

Chapter Five (#u51f85ec3-81f2-559a-b542-497e4d9df25e)

Elizabeth Pinch (#ue580a506-c81f-5a76-a03e-21bdc21b9b6c)

Chapter Six (#uff7dc57d-6e53-5b09-a009-fd1b06e08336)

Gou Jun Pei (#ub7e73ca1-7974-58dc-ab6d-3e566638dfc6)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Nico Sutil. Erik Bellof. Timo Heidfeld. (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Jeff Edgeson (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Tatiana Rusesa (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Alicia Hulme (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Bobby Wiles (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Samuel Daniels (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

John Hamilton (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Jim Wilson (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nathaniel Schumacher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Connie Wilson (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chris Davis (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Patricia Bellamy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Jacob Hargrave (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpage (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

One

HAROLD OPENED THE door that day to find a dark-skinned man in a well-cut suit smiling at him. At first he thought of reaching for his shotgun, but then he remembered that Lucille had made him sell it years ago on account of an incident involving a traveling preacher and an argument having to do with hunting dogs.

“Can I help you?” Harold said, squinting in the sunlight—light which only made the dark-skinned man in the suit look darker.

“Mr. Hargrave?” the man said.

“I suppose,” Harold replied.

“Who is it, Harold?” Lucille called. She was in the living room being vexed by the television. The news announcer was talking about Edmund Blithe, the first of the Returned, and how his life had changed now that he was alive again.

“Better the second time around?” the announcer on the television asked, speaking directly into the camera, laying the burden of answering squarely on the shoulders of his viewers.

The wind rustled through the oak tree in the yard near the house, but the sun was low enough that it drove horizontally beneath the branches and into Harold’s eyes. He held a hand over his eyes like a visor, but still, the dark-skinned man and the boy were little more than silhouettes plastered against a green-and-blue backdrop of pine trees beyond the open yard and cloudless sky out past the trees. The man was thin, but square-framed in his manicured suit. The boy was small for what Harold estimated to be about the age of eight or nine.

Harold blinked. His eyes adjusted more.

“Who is it, Harold?” Lucille called a second time, after realizing that no reply had come to her first inquiry.

Harold only stood in the doorway, blinking like a hazard light, looking down at the boy, who consumed more and more of his attention. Synapses kicked on in the recesses of his brain. They crackled to life and told him who the boy was standing next to the dark-skinned stranger. But Harold was sure his brain was wrong. He made his mind to do the math again, but it still came up with the same answer.

In the living room the television camera cut away to a cluster of waving fists and yelling mouths, people holding signs and shouting, then soldiers with guns standing statuesque as only men laden with authority and ammunition can. In the center was the small semidetached house of Edmund Blithe, the curtains drawn. That he was somewhere inside was all that was known.

Lucille shook her head. “Can you imagine it?” she said. Then: “Who is it at the door, Harold?”

Harold stood in the doorway taking in the sight of the boy: short, pale, freckled, with a shaggy mop of brown hair. He wore an old-style T-shirt, a pair of jeans and a great look of relief in his eyes—eyes that were not still and frozen, but trembling with life and rimmed with tears.

“What has four legs and goes ‘Boooo’?” the boy asked in a shaky voice.

Harold cleared his throat—not certain just then of even that. “I don’t know,” he said.

“A cow with a cold!”

Then the child had the old man by the waist, sobbing, “Daddy! Daddy!” before Harold could confirm or deny. Harold fell against the door frame—very nearly bowled over—and patted the child’s head out of some long-dormant paternal instinct. “Shush,” he whispered. “Shush.”

“Harold?” Lucille called, finally looking away from the television, certain that some terror had darkened her door. “Harold, what’s going on? Who is it?”

Harold licked his lips. “It’s...it’s...”

He wanted to say “Joseph.”

“It’s Jacob,” he said, finally.

Thankfully for Lucille, the couch was there to catch her when she fainted.

* * *

Jacob William Hargrave died on August 15, 1966. On his eighth birthday, in fact. In the years that followed, townsfolk would talk about his death in the late hours of the night when they could not sleep. They would roll over to wake their spouses and begin whispered conversations about the uncertainty of the world and how blessings needed to be counted. Sometimes they would rise together from the bed to stand in the doorway of their children’s bedroom to watch them sleep and to ponder silently on the nature of a God that would take a child so soon from this world. They were Southerners in a small town, after all: How could such a tragedy not lead them to God?

After Jacob’s death, his mother, Lucille, would say that she’d known something terrible was going to happen that day on account of what had happened just the night before.

That night Lucille dreamed of her teeth falling out. Something her mother had told her long ago was an omen of death.

All throughout Jacob’s birthday party Lucille had made a point to keep an eye on not only her son and the other children, but on all the other guests, as well. She flitted about like a nervous sparrow, asking how everyone was doing and if they’d had enough to eat and commenting on how much they’d slimmed down since last time she’d seen them or on how tall their children had gotten and, now and again, how beautiful the weather was. The sun was everywhere and everything was green that day.

Her unease made her a wonderful hostess. No child went unfed. No guest found themselves lacking conversation. She’d even managed to talk Mary Green into singing for them later in the evening. The woman had a voice silkier than sugar, and Jacob, if he was old enough to have a crush on someone, had a thing for her, something that Mary’s husband, Fred, often ribbed the boy about. It was a good day, that day. A good day, until Jacob disappeared.

He slipped away unnoticed the way only children and other small mysteries can. It was sometime between three and three-thirty—as Harold and Lucille would later tell the police—when, for reasons only the boy and the earth itself knew, Jacob made his way over the south side of the yard, down past the pines, through the forest and on down to the river, where, without permission or apology, he drowned.

* * *

Just days before the man from the Bureau showed up at their door Harold and Lucille had been discussing what they might do if Jacob “turned up Returned.”

“They’re not people,” Lucille said, wringing her hands. They were on the porch. All important happenings occurred on the porch.

“We couldn’t just turn him away,” Harold told his wife. He stamped his foot. The argument had turned very loud very quickly.

“They’re just not people,” she repeated.

“Well, if they’re not people, then what are they? Vegetable? Mineral?” Harold’s lips itched for a cigarette. Smoking always helped him get the upper hand in an argument with his wife which, he suspected, was the real reason she made such a fuss about the habit.

“Don’t be flippant with me, Harold Nathaniel Hargrave. This is serious.”

“Flippant?”

“Yes, flippant! You’re always flippant! Always prone to flippancy!”

“I swear. Yesterday it was, what, ‘loquacious’? So today it’s ‘flippant,’ huh?”

“Don’t mock me for trying to better myself. My mind is still as sharp as it always was, maybe even sharper. And don’t you go trying to get off subject.”

“Flippant.” Harold smacked the word, hammering the final t at the end so hard a glistening bead of spittle cleared the porch railing. “Hmph.”

Lucille let it pass. “I don’t know what they are,” she continued. She stood. Then sat again. “All I know is they’re not like you and me. They’re...they’re...” She paused. She prepared the word in her mouth, putting it together carefully, brick by brick. “They’re devils,” she finally said. Then she recoiled, as if the word might turn and bite her. “They’ve just come here to kill us. Or tempt us! These are the end days. ‘When the dead shall walk the earth.’ It’s in the Bible!”

Harold snorted, still hung up on “flippant.” His hand went to his pocket. “Devils?” he said, his mind finding its train of thought as his hand found his cigarette lighter. “Devils are superstitions. Products of small minds and even smaller imaginations. There’s one word that should be banned from the dictionary— devils. Ha! Now there’s a flippant word. It’s got nothing to do with the way things really are, nothing to do with these ‘Returned’ folks—and make no mistake about it, Lucille Abigail Daniels Hargrave, they are people. They can walk over and kiss you. I ain’t never met a devil that could do that...although, before we were married, there was this one blonde girl over in Tulsa one Saturday night. Yeah, now she might have been the devil, or a devil at least.”

“Hush up!” Lucille barked, so loudly she seemed to surprise herself. “I won’t sit here and listen to you talk that way.”

“Talk what way?”

“It wouldn’t be our boy,” she said, her words slowing as the seriousness of things came drifting back to her, like the memory of a lost son, perhaps. “Jacob’s gone on to God,” she said. Her hands had become thin, white fists in her lap.

A silence came.

Then it passed.

“Where is it?” Harold asked.

“What?”

“In the Bible, where is it?”

“Where’s what?”

“Where does it say ‘the dead will walk the earth’?”

“Revelations!” Lucille opened her arms as she said the word, as if the question could not be any more addle-brained, as if she’d been asked about the flight patterns of pine trees. “It’s right there in Revelations! ‘The dead shall walk the earth’!” She was glad to see that her hands were still fists. She waved them at no one, the way people in movies sometimes did.

Harold laughed. “What part of Revelations? What chapter? What verse?”

“You hush up,” she said. “That it’s in there is all that matters. Now hush!”

“Yes, ma’am,” Harold said. “Wouldn’t want to be flippant.”

* * *

But when the devil actually showed up at the front door—their own particular devil—small and wondrous as he had been all those years ago, his brown eyes slick with tears, joy and the sudden relief of a child who has been too long away from his parents, too long of a time spent in the company of strangers...well...Lucille, after she recovered from her fainting episode, melted like candle wax right there in front of the clean-cut, well-suited man from the Bureau. For his part, the Bureau man took it well enough. He smiled a practiced smile, no doubt having witnessed this exact scene more than a few times in recent weeks.

“There are support groups,” the Bureau man said. “Support groups for the Returned. And support groups for the families of the Returned.” He smiled.

“He was found,” the man continued—he’d given them his name but both Harold and Lucille were already terrible at remembering people’s names and having been reunited with their dead son didn’t do much to help now, so they thought of him simply as the Man from the Bureau “—in a small fishing village outside Beijing, China. He was kneeling at the edge of a river, trying to catch fish or some such from what I’ve been told. The local people, none of whom spoke English well enough for him to understand, asked him his name in Mandarin, how he’d gotten there, where he was from, all those questions you ask when coming upon a lost child.

“When it was clear that language was something of a barrier, a group of women were able to calm him. He’d started crying—and why wouldn’t he?” The man smiled again. “After all, he wasn’t in Kansas anymore. But they settled him down. Then they found an English-speaking official and, well...” He shrugged his shoulders beneath his dark suit, indicating the insignificance of the rest of the story. Then he added, “It’s happening like this all over.”

He paused again. He watched with a smile that was not disingenuous as Lucille fawned over the son who was suddenly no longer dead. She clutched him to her chest and kissed the crown of his head, then cupped his face in her hands and showered it with kisses and laughter and tears.

Jacob replied in kind, giggling and laughing, but not wiping away his mother’s kisses even though he was at that particular point in youth when wiping away a mother’s kisses was what seemed most appropriate to him.

“It’s a unique time for everyone,” the man from the Bureau said.

Kamui Yamamoto

The brass bell chimed lightly as he entered the convenience store. Outside someone was just pulling away from the gas pump and did not see him. Behind the counter a plump, red-faced man halted his conversation with a tall, lanky man and the two of them stared. The only sound was the low hum of the freezers. Kamui bowed low, the brass bell chiming a second time as the door closed behind him.

The men behind the counter still did not speak.

He bowed a second time, smiling. “Forgive me,” he said, and the men jumped. “I surrender.” He held his hands in the air.

The red-faced man said something that Kamui could not understand. He looked at the lanky man and the two of them spoke at length, glancing sideways as they did. Then the red-faced man pointed at the door. Kamui turned, but saw only the empty street and the rising sun behind him. “I surrender,” he said a second time.

He’d left his pistol buried next to a tree at the edge of the woods in which he’d found himself only a few hours ago, just as the other men had. He had even removed the jacket of his uniform and his hat and left them, as well, so that, now, he stood in the small gas station at the break of day in his undershirt, pants and well-shined boots. All this to avoid being killed by the Americans. “Yamamoto desu,” he said. Then: “I surrender.”

The red-faced man spoke again, louder this time. Then the second man joined him, both of them yelling and motioning in the direction of the door. “I surrender,” Kamui said yet again, fearing the way their voices were rising. The lanky man grabbed a soda can from the counter and threw it at him. It missed, and the man yelled again and pointed toward the door again and began searching for something else to throw.

“Thank you,” Kamui managed, though he knew it was not what he wanted to say. His English vocabulary was limited to very few words. He backed toward the door. The red-faced man reached beneath the counter and found a can of something. He threw it with a grunt. The can struck Kamui above the left temple. He fell back against the door. The brass bell rang.

The red-faced man threw more cans while the lanky man yelled and searched for objects of his own to throw until, stumbling, Kamui fled the gas station, his hands above him, proving that he was not armed and meant to do nothing other than turn himself in. His heart beat in his ears.

Outside, the sun had risen and the city was cast a soft orange. It looked peaceful.

With a trickle of blood running down the side of his head, he raised his hands into the air and walked down the street. “I surrender!” he yelled, waking the town, hoping the people he found would let him live.

Two

OF COURSE, EVEN for people returning from the dead, there was paperwork. The International Bureau of the Returned was receiving funding faster than it could spend it. And there wasn’t a single country on the planet that wasn’t willing to dig into treasury reserves or go into debt to try and secure whatever “in” they could with the Bureau due to the fact that it was the only organization on the planet that was able to coordinate everything and everyone.

The irony was that no one within the Bureau knew more than anyone else. All they were really doing were counting people and giving them directions home. That was it.

* * *

When the emotion had died down and the hugging and all stopped in the doorway of the Hargraves’ little house—nearly a half hour later—Jacob was moved into the kitchen where he could sit at the table and catch up on all the eating he’d missed in his absence. The Bureau man sat in the living room with Harold and Lucille, took his stacks of paperwork from a brown, leather briefcase and got down to business.

“When did the returning individual originally die?” asked the Bureau man, who—for a second time—revealed his name as Agent Martin Bellamy.

“Do we have to say that?” Lucille asked. She inhaled and sat straighter in her seat, suddenly looking very regal and discriminating, having finally straightened her long, silver hair that had come undone while fawning over her son.

“Say what?” Harold replied.

“She means ‘die,’” Agent Bellamy said.

Lucille nodded.

“What’s wrong with saying he died?” Harold asked, his voice louder than he’d planned. Jacob was still within eyesight, if mostly out of earshot.

“Shush!”

“He died,” Harold said. “No sense in pretending he didn’t.” He didn’t notice, but his voice was lower now.

“Martin Bellamy knows what I mean,” Lucille said. She wrung her hands in her lap, looking for Jacob every few seconds, as if he were a candle in a house of drafts.

Agent Bellamy smiled. “It’s okay,” he said. “This is pretty common, actually. I should have been more considerate. Let’s start again, shall we?” He looked down at his questionnaire. “When did the returning individual—”

“Where are you from?”

“Sir?”

“Where are you from?” Harold was standing by the window looking out at the blue sky.

“You sound like a New Yorker,” Harold said.

“Is that good or bad?” Agent Bellamy asked, pretending he had not been asked about his accent a dozen times since being assigned to the Returned of southern North Carolina.

“It’s horrible,” Harold said. “But I’m a forgiving man.”

“Jacob,” Lucille interrupted. “Call him Jacob, please. His name is Jacob.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Agent Bellamy said. “I’m sorry. I should know better by now.”

“Thank you, Martin Bellamy,” Lucille said. Again, somehow, her hands were fists in her lap. She breathed deeply and, with concentration, unfolded them. “Thank you, Martin Bellamy,” she said again.

“When did Jacob leave?” Agent Bellamy asked again softly.

“August 15, 1966,” Harold said. He moved into the doorway, looking unsettled. He licked his lips. His hands took turns moving from the pockets of his worn, old pants up to his worn, old lips, finding no peace—or cigarette—on either side of the journey.

Agent Bellamy made notes.

“How did it happen?”

* * *

The word Jacob became an incantation that day as the searchers looked for the boy. At regular intervals the call went up. “Jacob! Jacob Hargrave!” And then another voice lifted the name and passed it down the line. “Jacob! Jacob!”

In the beginning their voices trampled upon one another in a cacophony of fear and desperation. But then the boy was not quickly found and, to save their throats, the men and women of the search party took turns shouting out as the sun turned gold and dripped down the horizon and was swallowed first by the tall trees and then by the low brush.

Then they were all trudging drunkenly—exhausted from high-stepping through the dense bramble, wrung out from worry. Fred Green was there with Harold. “We’ll find him,” Fred said again and again. “Did you see that look in his eyes when he unwrapped that BB gun I gave him? You ever seen a boy so excited?” Fred huffed, his legs burning from fatigue. “We’ll find him.” He nodded. “We’ll find him.”

Then it was full-on night and the bushy, pine-laden landscape of Arcadia sparkled with the glow of flashlights.

When they neared the river Harold was glad he’d talked Lucille into staying back at the house—“He might come back,” he had said, “and he’ll want his mama”—because he knew, by whatever means such things are known, that he would find his son in the river.

Harold sloshed knee-deep in the shallows—slowly, taking a step, calling the boy’s name, pausing to listen out in case he should be somewhere nearby, calling back, taking another step, calling the boy’s name again, and on and on.

When he finally came upon the body, the moonlight and the water had shone the boy to a haunting and beautiful silver, the same color as the glimmering water.

“Dear God,” Harold said. And that was the last time he would ever say it.

* * *

Harold told the story, hearing suddenly all the years in his voice. He sounded like an old man, hardened and rough. Now and again as he spoke, he would reach a thick, wrinkled hand to run over the few thin, gray strands still clinging to his scalp. His hands were decorated with liver spots and his knuckles were swollen from the arthritis that sometimes bothered him. It didn’t bother him as badly as it did some other people his age, but it did just enough to remind him of the wealth of youth that was not his anymore. Even as he spoke, his lower back jolted with a small twinge of pain.

Hardly any hair. Mottled skin. His large, round head. His wrinkled, wide ears. Clothes that seemed to swallow him up no matter how hard Lucille tried to find something that fit him better. No doubt about it: he was an old man now.

Something about having Jacob back—still young and vibrant—made Harold Hargrave realize his age.

Lucille, just as old and gray as her husband, only looked away as he spoke, only watched her eight-year-old son sit at the kitchen table eating a slice of pecan pie as if, just now, it were 1966 again and nothing was wrong and nothing would ever be wrong again. Sometimes she would clear a silver strand of hair from her face, but if she caught sight of her thin, liver-spotted hands, they did not seem to bother her.

They were a pair of thin, wiry birds, Harold and Lucille. She outgrew him in these later years. Or, rather, he shrank faster than she so that, now, he had to look up at her when they argued. And Lucille also had the benefit of not wasting away quite as much as he had—something she blamed upon his years of cigarette smoking. Her dresses still fit her. Her thin, long arms were nimble and articulate where his, hidden beneath the puffiness of shirts that fit him too loosely, made him look a bit more vulnerable than he used to. Which was giving her an edge these days.

Lucille took pride in that, and did not feel quite so guilty about it, even though she sometimes thought she should.

Agent Bellamy wrote until his hand cramped and then he wrote more. He’d had the forethought to record the interview, but he still found it good policy to write things down, as well. People seemed offended if they met with a government man and nothing was written down. This worked for Agent Bellamy. His brain was the type that preferred to see things rather than hear them. If he didn’t write it all down now he’d just be stuck doing it later.

Bellamy wrote from the time the birthday party began that day in 1966. He wrote through the recounting of Lucille’s weeping and guilt—she’d been the last one to see Jacob alive; she only remembered a brief image of one of his pale arms as he darted around a corner, chasing one of the other children. Bellamy wrote that there were almost more people at the funeral than the church could hold.

But there were parts of the interview that he did not write. Details that, out of respect, he committed only to memory rather than to bureaucratic documentation.

Harold and Lucille had survived the boy’s death, but only just. The next fifty-odd years became infected with a peculiar type of loneliness, a tactless loneliness that showed up unbidden and began inappropriate conversations over Sunday dinner. It was a loneliness they never named and seldom talked about. They only shuffled around it with their breaths held, day in and day out, as if it were an atom smasher—reduced in scale but not in complexity or splendor—suddenly shown up in the center of the living room and dead set on affirming all the most ominous and far-fetched speculations of the harsh way the universe genuinely worked.

In its own way, that was a truth of sorts.

Over the years they not only became accustomed to hiding from their loneliness, they became skilled at it. It was a game, almost: don’t talk about the Strawberry Festival, because he had loved it; don’t stare too long at buildings you admire because they will remind you of the time you said he would grow into an architect one day; ignore the children in whose face you see him.

When Jacob’s birthday came around each year they would spend the day being somber and having difficulty making conversation. Lucille might take to weeping with no explanation, or Harold might smoke a little more that day than he had the day before.

But that was only in the beginning. Only in those first, sad years.

They grew older.

Doors closed.

Harold and Lucille had become so far removed from the tragedy of Jacob’s death that when the boy reappeared at their front door—smiling, still perfectly assembled and unaged, still their blessed son, still only eight years old—all of it was so far away that Harold had forgotten the boy’s name.

* * *

Then Harold and Lucille were done talking and there was silence. But despite its solemnity, it was short-lived. Because there was the sound of Jacob sitting at the kitchen table raking his fork across his plate, gulping down his lemonade and burping with great satisfaction. “Excuse me,” the boy yelled to his parents.

Lucille smiled.

“Forgive me for asking this,” Agent Bellamy began. “And please, don’t take this as any type of accusation. It’s simply something we have to ask in order to better understand these...unique circumstances.”

“Here it comes,” Harold said. His hands had finally stopped foraging for phantom cigarettes and settled into his pockets. Lucille waved her hand dismissively.

“What were things like between you and Jacob before?” Agent Bellamy asked.

Harold snorted. His body finally decided his right leg would better hold his weight than his left. He looked at Lucille. “This is the part where we’re supposed to say we drove him off or something. Like they do on TV. We’re supposed to say that we’d had a fight with him, denied him supper, or some kind of abuse like you see on TV. Something like that.” Harold walked over to a small table that stood in the hallway facing the front door. In the top drawer was a fresh pack of cigarettes.

Before he’d even made his way back to the living room Lucille opened fire. “You will not!”

Harold opened the wrapper with mechanical precision, as if his hands were not his own. He placed a cigarette, unlit, between his lips and scratched his wrinkled face and exhaled, long and slow. “That’s all I needed,” he said. “That’s all.”

Agent Bellamy spoke softly. “I’m not trying to say that you or anyone else caused your son’s...well, I’m running out of euphemisms.” He smiled. “I’m only asking. The Bureau is trying hard to make heads or tails of this, just like everyone else. We might be in charge of helping to connect people up with one another, but that doesn’t mean we have any inside knowledge into how any of this is working. Or why it’s happening.” He shrugged his shoulders. “The big questions are still big, still untouchable. But our hope is that by finding out everything we can, by asking the questions that everyone might not necessarily be comfortable answering, we can touch some of these big questions. Get a handle on them, before they get out of hand.”

Lucille leaned forward on the old couch. “And how might they get out of hand? Are things getting out of hand?”

“They will,” Harold said. “Bet your Bible on that.”

Agent Bellamy only shook his head in an even, professional manner and returned to his original question. “What were things like between you and Jacob before he left?”

Lucille could feel Harold coming up with an answer, so she answered to keep him silent. “Things were fine,” she said. “Just fine. Nothing strange whatsoever. He was our boy and we loved him just like any parent should. And he loved us back. And that’s all that it was. That’s all it still is. We love him and he loves us and now, by the grace of God, we’re back together again.” She rubbed her neck and lifted her hands. “It’s a miracle,” she said.

Martin Bellamy took notes.

“And you?” he asked Harold.

Harold only took his unlit cigarette from his mouth and rubbed his head and nodded. “She said it all.”

More note-taking.

“I’m going to ask a silly question now, but are either of you very religious?”

“Yes!” Lucille said, sitting suddenly erect. “Fan and friend of Jesus! And proud of it. Amen.” She nodded in Harold’s direction. “That one there, he’s the heathen. Dependent wholly on the grace of God. I keep telling him to repent, but he’s stubborn as a mule.”

Harold chuckled like an old lawn mower. “We take religion in turns,” he said. “Fifty-some years later, it’s still not my turn, thankfully.”

Lucille waved her hands.

“Denomination?” Agent Bellamy asked, writing.

“Baptist,” Lucille answered.

“For how long?”

“All my life.”

Notes.

“Well, that ain’t exactly right,” Lucille added.

Agent Bellamy paused.

“For a while there I was a Methodist. But me and the pastor couldn’t see eye to eye on certain points in the Word. I tried one of them Holiness churches, too, but I just couldn’t keep up with them. Too much hollering and singing and dancing. Felt like I was at a party first and in the house of the Lord second. And that ain’t no way for a Christian to be.” Lucille leaned to see that Jacob was still where he was supposed to be—he was half nodding at the table, just as he had always been apt to—then she continued. “And then there was a while when I tried being—”

“The man doesn’t need all of this,” Harold interrupted.

“You hush up! He asked me! Ain’t that right, Martin Bellamy?”

The agent nodded. “Yes, ma’am, you’re right. All of this may prove very important. In my experience, it’s the little details that matter. Especially with something this big.”

“Just how big is it?” Lucille asked quickly, as if she had been waiting for the opening.

“Do you mean how many?” Bellamy asked.

Lucille nodded.

“Not terribly many,” Bellamy said in a measured voice. “I’m not allowed to give any specific numbers, but it’s only a small phenomenon, a modest number.”

“Hundreds?” Lucille pressed. “Thousands? What’s ‘modest’?”

“Not enough to be concerned about, Mrs. Hargrave,” Bellamy replied, shaking his head. “Only enough to remain miraculous.”

Harold chuckled. “He’s got your number,” he said.

Lucille only smiled.

* * *

By the time the details were all handed over to Agent Bellamy the sun had sighed into the darkness of the earth and there were crickets singing outside the window and Jacob lay quietly in the middle of Harold and Lucille’s bed. Lucille had taken great pleasure in lifting the boy from the kitchen table and carrying him up to the bedroom. She never would have believed that, at her age, with her hip the way it was, that she had the strength to carry him by herself.

But when the time came, when she bent quietly at the table and placed her arms beneath the boy and called her body into action, Jacob rose, almost weightlessly, to meet her. It was as if she were in her twenties again. Young and nimble. It was as if time and pain were but rumors.

She carried him uneventfully up the stairs and, when she had tucked him beneath the covers, she settled onto the bed beside him and hummed gently the way she used to. He did not fall asleep just then, but that was okay, she felt.

He had slept long enough.

Lucille sat for a while only watching him, watching his chest rise and fall, afraid to take her eyes away, afraid that the magic—or the miracle—might suddenly end. But it did not, and she thanked the Lord.

When she came back into the living room Harold and Agent Bellamy were entangled in an awkward silence. Harold stood in the doorway, taking sharp puffs of a lit cigarette and throwing the smoke through the screen door into the night. Agent Bellamy stood next to the chair where he’d been sitting. He looked thirsty and tired all of a sudden. Lucille realized then that she hadn’t offered him a drink since he’d arrived, and that made her hurt in an unusual way. But, from Harold and Agent Bellamy’s behavior, she knew, somehow, that they were about to hurt her in a different way.

“He’s got something to ask you, Lucille,” Harold said. His hand trembled as he put the cigarette to his mouth. Because of this she made the decision to let him smoke unharassed.

“What is it?”

“Maybe you’ll want to sit down,” Agent Bellamy said, making a motion to come and help her sit.

Lucille took a step back. “What is it?”

“It’s a sensitive question.”

“I can tell. But it can’t be as bad as all that, now can it?”

Harold gave her his back and puffed silently on his cigarette with his head hung.

“For everyone,” Agent Bellamy began, “this is a question that can seem simple at first but, believe me, it is a very complex and serious matter. And I hope that you would take a moment to consider it thoroughly before you answer. Which isn’t to say that you only have one chance to answer. But only to say that I just want you to be sure that you’ve given the question its proper consideration before you make a decision. It’ll be difficult but, if possible, try not to let your emotions get the better of you.”

Lucille went red. “Why, Mr. Martin Bellamy! I never would have figured you for one of those sexist types. Just because I’m a woman doesn’t mean I’m going to go all to pieces.”

“Dammit, Lucille,” Harold barked, though his voice seemed to have trouble finding its legs. “Just listen to the man.” He coughed then. Or perhaps he sobbed.

Lucille sat.

Martin Bellamy sat, as well. He brushed some invisible something from the front of his pants and examined his hands for a moment.

“Well,” Lucille said, “get on with it. All this buildup is killing me.”

“This is the last question I’ll be asking you this evening. And it’s not necessarily a question you have to answer just now, but the sooner you answer it, the better. It just makes things less complicated when the answer comes quickly.”

“What is it?” Lucille pleaded.

Martin Bellamy inhaled. “Do you want to keep Jacob?”

* * *

That was two weeks ago.

Jacob was home now. Irrevocably. The spare room had been converted back into his bedroom and the boy had settled into his life as if it had never ended to begin with. He was young. He had a mother. He had a father. His universe ended there.

* * *

Harold, for reasons he could not quite put together in his head, had been painfully unsettled since the boy’s return. He’d taken to smoking like a chimney. So much so that he spent most of his time outside on the porch, hiding from Lucille’s lectures about his dirty habit.

Everything had changed so quickly. How could he not take up a bad habit or two?

“They’re devils!” Harold heard Lucille’s voice repeat inside his head.

The rain was spilling down. The day was old. Just behind the trees, darkness was coming on. The house had quieted. Just above the sound of the rain was the light huffing of an old woman who’d spent too much time chasing a child. She came through the screen door, dabbing sweat from her brow, and crumpled into her rocking chair.

“Lord!” Lucille said. “That child’s gonna run me to death.”

Harold put out his cigarette and cleared his throat—which he always did before trying to get Lucille’s goat. “You mean that devil?”

She waved her hand at him. “Shush!” she said. “Don’t you call him that!”

“You called him that. You said that’s what they all were, remember?”

She was still short of breath from chasing the boy. Her words came staggered. “That was before,” she huffed. “I was wrong. I see that now.” She smiled and leaned back in exhaustion. “They’re a blessing. A blessing from the Lord. That’s what they are. A second chance!”

They sat for a while in silence, listening to Lucille’s breath find itself. She was an old woman now, in spite of being a mother of an eight-year-old. She tired easily.

“And you should spend more time with him,” Lucille said. “He knows you’re keeping your distance. He can tell it. He knows you’re treating him differently than you used to. When he was here before.” She smiled, liking that description.

Harold shook his head. “And what will you do when he leaves?”

Lucille’s face tightened. “Hush up!” she said. “‘Keep your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking lies.’ Psalm 34:13.”

“Don’t you Psalm at me. You know what they’ve been saying, Lucille. You know just as well as I do. How sometimes they just up and leave and nobody ever hears from them again, like the other side finally called them back.”

Lucille shook her head. “I don’t have time for such nonsense,” she said, standing in spite of the heaviness of fatigue that hung in her limbs like sacks of flour. “Just rumors and nonsense. I’m going to start dinner. Don’t you sit out here and catch pneumonia. This rain will kill you.”

“I’ll just come back,” Harold said.

“Psalm 34:13!”

She closed and locked the screen door behind her.

* * *

From the kitchen came the clattering of pots and pans. Cabinet doors opening, closing. The scent of meat, flour, spices, all of it drenched in the perfume of May and rain. Harold was almost asleep when he heard the boy’s voice. “Can I come outside, Daddy?” Harold shook off the drowsiness. “What?” He had heard the question perfectly well.

“Can I come outside? Please?”

For all the gaps in Harold’s old memory, he remembered how defenseless he’d always been when “Please” was laid out just so before him.

“Your mama’ll have a fit,” he said.

“Just a little one, though.”

Harold swallowed to keep from laughing.

He fumbled for a cigarette and failed—he’d sworn he’d had at least one more. He groped his pockets. In his pocket, where there was no cigarette, he found a small, silver cross—a gift from someone, though the place in his mind where the details of that particular memory should have been stored was empty. He hardly even remembered carrying it, but couldn’t help looking down at it as if it were a murder weapon.

The words God Loves You, once, had been etched in the place where Christ belonged. But now the words were all but gone. Only an O and half a Y remained. He stared at the cross, then, as if his hand belonged to someone else, his thumb began rubbing back and forth at the crux.

Jacob stood in the kitchen behind the screen door. He leaned against the door frame with his hands behind his back and his legs crossed, looking contemplative. His eyes scanned back and forth over the horizon, watching the rain and the wind and, then, his father. He exhaled heavily. Then he cleared his throat. “Sure would be nice to come outside,” he said with flourish and drama.

Harold chuckled.

In the kitchen something was frying. Lucille was humming.

“Come on out,” Harold said.

Jacob came and sat at Harold’s feet and, as if in reply, the rain became angry. Rather than falling from the sky, it leaped to the earth. It whipped over the porch railing, splashing them both, not that they paid it any heed. For a very long time the old man and the once-dead boy sat looking at each other. The boy was sandy-haired and freckled, his face as round and smooth as it always had been. His arms were unusually long, just as they had been, as his body was beginning its shift into an adolescence denied him fifty years ago. He looked healthy, Harold suddenly thought.

Harold licked his lips compulsively, his thumb working the center of the cross. The boy did not move at all. If he hadn’t blinked now and again, he might as well have been dead.

* * *

“Do you want to keep him?”

It was Agent Bellamy’s voice inside Harold’s head this time.

“It’s not my decision,” Harold said. “It’s Lucille’s. You’ll have to ask her. Whatever she says, I’ll abide by.”

Agent Bellamy nodded. “I can understand that, Mr. Hargrave. But I still have to ask you. I have to know your answer. It will stay between us, just you and me. I can even turn off the recorder if you want. But I have to have your answer. I have to know what you want. I have to know if you want to keep him.”

“No,” Harold said. “Not for all the world. But what choice do I have?”

Lewis and Suzanne Holt

He awoke in Ontario; she outside Phoenix. He had been an accountant. She taught piano.

The world was different, but still the same. Cars were quieter. Buildings were taller and seemed to glimmer in the night more than they used to. Everyone seemed busier. But that was all. And it did not matter.

He went south, hopping trains in a way that had not been done in years. He kept clear of the Bureau only by fortune or fate. She had started northeast—nothing more than a notion she felt possessed to follow—but it was not long before she was picked up and moved to just outside Salt Lake City, to what was quickly becoming a major processing facility for the region. Not long after that he was picked up somewhere along the border of Nebraska and Wyoming.

Ninety years after their deaths, they were together again.

She had not changed at all. He had grown a shade thinner than he had been, but only on account of his long journey. Behind fencing and uncertainty, they were not as afraid as others.

There is a music that forms sometimes, from the pairing of two people. An inescapable cadence that continues on.

Three

THE TOWN OF Arcadia was situated along the countryside in that way that many small, Southern towns were. It began with small, one-story wooden houses asleep in the middle of wide, flat yards along the sides of a two-lane blacktop that winded among dense pines, cedars and white oaks. Here and there, fields of corn or soybeans were found in the spring and summer. Only bare earth in the winter.

After a couple of miles the fields became smaller, the houses more frequent. Once one entered the town proper they found only two streetlights, a clunky organization of roads and streets and dead ends cluttered with old, exhausted homes. The only new houses in Arcadia were those that had been rebuilt after hurricanes. They glimmered in fresh paint and new wood and made a person imagine that, perhaps, something new could actually happen in this old town.

But new things did not come to this town. Not until the Returned.

The streets were not many and neither were the houses. In the center of town stood the school: an old, brick affair with small windows and small doors and retrofitted air-conditioning that did not work.

Off to the north, atop a small hill just beyond the limits of town, stood the church. It was built from wood and clapboard and sat like a lighthouse, reminding the people of Arcadia that there was always someone above them.

Not since ’72 when the Sainted Soul Stirrers of Solomon—that traveling gospel band with the Jewish bassist from Arkansas—came to town had the church been so full. Just people atop people. Cars and trucks scattered about the church lawn. Someone’s rust-covered pickup loaded down with lumber was parked against the crucifix in the center of the lawn, as if Jesus had gotten down off the cross and decided to make a run to the hardware store. A cluster of taillights covered up the small sign on the church lawn that read Jesus Loves You—Fish Fry May 31. Cars were stacked along the shoulder of the highway the way they had been that time back in ’63—or was it ’64?—at the funeral of those three Benson boys who’d all died in one horrible car crash and were mourned over the course of one long, dark day of lamentation.

“You need to come with us,” Lucille said as Harold parked the old truck on the shoulder of the road and pawed his shirt pocket for his cigarettes. “What are folks going to think when you’re not there?” She unfastened Jacob’s seat belt and straightened his hair.

“They’ll think, ‘Harold Hargrave won’t come in the church? Glory be! In these times of madness at least something is as it always has been!’”

“It’s not like there’s a service going on, you heathen. It’s just a town meeting. No reason why you shouldn’t come in.”

Lucille stepped out of the truck and straightened her dress. It was her favorite dress, the one she wore to important things, the one that picked up dirt from every surface imaginable—a cotton/polyester blend colored in a pastel shade of green with small flowers stitched along the collar and patterned around the end of the thin sleeves. “I don’t know why I bother sometimes. I hate this truck,” she said, wiping the back of her dress.

“You’ve hated every truck I’ve ever owned.”

“But still you keep buying them.”

“Can I stay here?” Jacob asked, fiddling with a button on the collar of his shirt. Buttons exercised a mysterious hold over the boy. “Daddy and me could—”

“Daddy and I could,” Lucille corrected.

“No,” Harold said, almost laughing. “You go with your mama.” He put a cigarette to his lips and stroked his chin. “Smoke’s bad for you. Gives you wrinkles and bad breath and makes you hairy.”

“Makes you stubborn, too,” Lucille added, helping Jacob from the cab.

“I don’t think they want me in there,” Jacob said.

“Go with your mama,” Harold said in a hard voice. Then he lit his cigarette and took in as much nicotine as his tired old lungs could manage.

* * *

When his wife and the thing that might or might not be his son—he was still not sure of his stance on that exactly—were gone, Harold took one more pull on his cigarette and blew the smoke out through the open window. Then he sat with the cigarette burning down between his fingers. He stroked his chin and watched the church.

The church needed to be painted. It was peeling here and there and it was hard to put a finger on exactly what color the building was supposed to be, but a person could tell that it had once been much grander than it was now. He tried to think back to what color the church had been when the paint was fresh—he’d most certainly been around to see it painted. He even could almost remember who had done the job—some outfit from up around Southport—the name escaped him, as did the original paint color. All he could see in his mind was the current faded exterior.

But isn’t that the way it is with memory? Give it enough time and it will become worn down and covered in a patina of self-serving omissions.

But what else could we trust?

Jacob had been a firecracker. A live wire. Harold remembered all the times the boy had gotten in trouble for not coming home before sunset or for running in church. One time he’d even come close to having Lucille in hysterics because he’d climbed to the top of Henrietta Williams’s pear tree. Everybody was calling after him and the boy just sat there up in the shaded branches of the tree among ripe pears and dappled sunlight. Probably having himself a good old laugh about things.

In the glow of the streetlights Harold caught sight of a small creature darting from the steeple of the church—a flash of movement and wings. It rose for a second and glowed like snow in the dark night as car headlights flashed upon it.

And then it was gone and, Harold knew, not to return.

“It’s not him,” Harold said. He flicked his cigarette on the ground and leaned back against the musty old seat. He lolled his head and asked only of his body that it should go to sleep and be plagued by neither dream nor memory. “It’s not.”

* * *

Lucille held tightly to Jacob’s hand as she made her way through the crowd cluttered around the front of the church as best as her bad hip would let her.

“Excuse me. Hi, there, Macon, how are you tonight? Pardon us. You doing okay tonight, Lute? That’s good. Excuse me. Excuse us. Well, hello, Vaniece! Ain’t seen you in ages. How you been? Good! That’s good to hear! Amen. You take care now. Excuse me. Excuse us. Hey, there. Excuse us.”

The crowd parted as she hoped they would, leaving Lucille unsure as to whether it was a sign that there was still decency and manners in the world, or a sign that she had, finally, become an old woman.

Or, perhaps they moved aside on account of the boy who walked beside her. There weren’t supposed to be any Returned here tonight. But Jacob was her son, first and foremost, and nothing or no one—not even death or its sudden lack thereof—was going to cause her to treat him as anything other than that.

The mother and son found room in a front pew next to Helen Hayes. Lucille seated Jacob beside her and proceeded to join the cloud of murmuring that was like a morning fog clinging to everything. “So many people,” she said, folding her hands across her chest and shaking her head.

“Ain’t seen most of them in a month of Sundays,” Helen Hayes said. Mostly everyone in and around Arcadia had some degree of relation; Helen and Lucille were cousins. Lucille had the long, angular look of the Daniels family: she was tall with thin wrists and small hands, a nose that made a sharp, straight line below her brown eyes. Helen, on the other hand, was all roundness and circles, thick wrists and a wide, round face. Only their hair, silver and straight now where it had once been as dark as creosote, showed that the two women were indeed related.

Helen was frighteningly pale, and she spoke through pursed lips, which gave her a very serious and upset appearance. “And you’d think that when this many people finally came to church, they’d come for the Lord. Jesus was the first one to come back from the dead, but do any of these heathens care?”

“Mama?” Jacob said, still fascinated by the loose button on his shirt.

“Do they come here for Jesus?” Helen continued. “Do they come to pray? When’s the last time they paid their tithes? When’s the last revival they came to? Tell me that. That Thompson boy there...” She pointed a plump finger at a clump of teenagers huddled near the back corner of the church. “When’s the last time you seen that boy in church?” She grunted. “Been so long, I thought he was dead.”

“He was,” Lucille said in a low voice. “You know that as well as anyone else that sets eyes on him.”

“I thought this meeting was supposed to be just for, well, you know?”

“Anybody with common sense knows that wasn’t going to happen,” Lucille said. “And, frankly, it shouldn’t happen. This meeting is all about them. Why shouldn’t they be here?”

“I hear Jim and Connie are living here,” Helen said. “Can you believe it?”

“Really?” Lucille replied. “I hadn’t heard. But why shouldn’t they? They’re a part of this town.”

“They were,” Helen corrected, offering no sympathy in her tone.

“Mama?” Jacob interrupted.

“Yes?” Lucille replied. “What is it?”

“I’m hungry.”

Lucille laughed. The notion that she had a son who was alive and who wanted food still made her very happy. “But you just ate!”

Jacob finally succeeded in popping the loose button from his shirt. He held it in his small, white hands, turned it over and studied it the way one studies a proposal of theoretical math. “But I’m hungry.”

“Amen,” Lucille said. She patted his leg and kissed his forehead. “We’ll get you something when we get back home.”

“Peaches?”

“If you want.”

“Glazed?”

“If you want.”

“I want,” Jacob said, smiling. “Daddy and me—”

“Daddy and I,” Lucille corrected again.

* * *

It was only May, but the old church was already boiling. It had never had decent air-conditioning, and with so many people crowded in one atop the other, like sediment, the air would not move and there was the feeling that, at any moment, something very dramatic might occur.

The feeling made Lucille uneasy. She remembered reading newspapers or seeing things on the television about some terrible tragedy that began with too many people crowded together in too small of a space. Nobody would have anywhere to run, Lucille thought. She looked around the room—as best she could on account of all the people cluttering up her eye line—and counted the exits, just in case. There was the main doorway at the back of the church, but that was full up with people. Seemed like almost everybody in Arcadia was there, all six hundred of them. A wall of bodies.

Now and again she would notice the mass of people ripple forward as someone else forced entry into the church and into the body of the crowd. There came a low grumbling of “Hello” and “I’m sorry” and “Excuse me.” If this were all a prelude to some tragic stampede death, at least it was cordial, Lucille thought.

Lucille licked her lips and shook her head. The air grew stiffer. There was no room for a body to move but, still, people were coming into the church. She could feel it. Probably, they were coming from Buckhead or Waccamaw or Riegelwood. The Bureau was trying to hold these town hall meetings in every town they could and there were some folks who’d become something akin to groupies—the kind you hear about that go around following famous musicians from one show to another. These people would follow the agents from the Bureau from one town hall meeting to another, looking for inconsistencies and a chance to start a fight.

Lucille even noticed a man and a woman that looked like they might have been a reporter and a photographer. The man looked like the kind she saw in magazines or read about in books: with his disheveled hair and five-o-clock shadow. Lucille imagined him smelling of split wood and the ocean.

The woman was sharply dressed, with her hair pulled back in a ponytail and her makeup flawlessly applied. “I wonder if there’s a news van out there,” Lucille said, but her words were lost in the clamor of the crowd.

As if cued by a stage director, Pastor Peters appeared from the cloistered door at the corner of the pulpit. His wife came after, looking as small and frail as she always did. She wore a plain black dress that made her look all the smaller. Already she was sweating, dabbing her brow in a delicate way. Lucille had trouble remembering the woman’s first name. It was a small, frail thing, her name, something that people tended to overlook, just like the woman to whom it belonged.

In a type of biblical contradiction to his wife, Pastor Robert Peters was a tall, wide-bodied man with dark hair and a perpetually tanned-looking complexion. He was solid as stone. The kind of man who looked born, bred, propagated and cultivated for a way of life that hinged upon violence. Though, for as long as Lucille had known the young preacher, she’d never known him to so much as raise his voice—not counting the voice raising that came at the climax of certain sermons, but that was no more a sign of a violent soul than thunder was the sign of an angry god. Thunder in the voice of pastors was just the way God got your attention, Lucille knew.

“It’s a taste of hell, Reverend,” Lucille said with a grin when the pastor and his wife had come near enough.

“Yes, ma’am, Mrs. Lucille,” Pastor Peters replied. His large, square head swung on his large, square neck. “We might have to see about getting a few people to exit quietly out the back. Don’t think I’ve ever seen it this full. Maybe we ought to pass the plate around before we get rid of them, though. I need new tires.”

“Oh, hush!”

“How are you tonight, Mrs. Hargrave?” The pastor’s wife put her small hand to her small mouth, covering a small cough. “You look good,” she said in a small voice.

“Poor thing,” Lucille said, stroking Jacob’s hair, “are you all right? You look like you’re falling apart.”

“I’m fine,” the woman said. “Just a little under the weather. It’s awfully hot in here.”

“We may need to see about asking some of these people to stand outside,” the pastor said again. He raised a thick, square hand, as if the sun were in his eyes. “Never have been enough exits in here.”

“Won’t be no exits in hell!” Helen added.

Pastor Peters only smiled and reached over the pew to shake her hand. “And how’s this young fellow?” he said, aiming a bright smile at Jacob.

“I’m fine.”

Lucille tapped him on the leg.

“I’m fine, sir,” he corrected.

“What do you make of all this?” the pastor asked, chuckling. Beads of sweat glistened on his brow. “What are we going to do with all these people, Jacob?”

The boy shrugged and received another tap on the thigh.

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Maybe we could send them all home? Or maybe we could just get a water hose and hose them all down.”

Jacob smiled. “A preacher can’t do stuff like that.”

“Says who?”

“The Bible.”

“The Bible? Are you sure?”

Jacob nodded. “Want to hear a joke? Daddy teaches me the best jokes.”

“Does he?”

“Mmm-hmm.”

Pastor Peters kneeled, much to Lucille’s embarrassment. She hated the notion of the pastor dirtying his suit on account of some two-bit joke that Harold had taught Jacob. Lord knows Harold knew some jokes that weren’t meant for the light of holiness.

She held her breath.

“What did the math book tell the pencil?”

“Hmm.” Pastor Peters rubbed his hairless chin, looking very deep in thought. “I don’t know,” he said finally. “What did the math book tell the pencil?”

“I’ve got a lot of problems,” Jacob said. Then he laughed. To some, it was only the sound of a child laughing. Others, knowing that this boy had been dead only a few weeks prior, did not know how to feel.

The pastor laughed with the boy. Lucille, too—thanking God that the joke hadn’t been the one about the pencil and the beaver.

Pastor Peters reached into the breast pocket of his coat and, with considerable flourish, conjured a small piece of foil-wrapped candy. “You like cinnamon?”

“Yes, sir! Thank you!”

“He’s so well mannered,” Helen Hayes added. She shifted in her seat, her eyes following the pastor’s frail wife, whose name Helen could not remember for the life of her.

“Anyone as well mannered as him deserves some candy,” the pastor’s wife said. She stood behind her husband, gently patting the center of his back—even that seemed a great feat for her, with him being so large and her being so small. “It’s hard to find well-behaved children these days, what with things being the way they are.” She paused to dab her brow. She folded her handkerchief and covered her mouth and coughed into it mouselike. “Oh, my.”

“You’re just about the sickest thing I’ve ever seen,” Helen said.

The pastor’s wife smiled and politely said, “Yes, ma’am.”

Pastor Peters patted Jacob’s head. Then he whispered to Lucille, “Whatever they say, don’t let it bother him...or you. Okay?”

“Yes, Pastor,” Lucille said.

“Yes, sir,” Jacob said.

“Remember,” the pastor said to the boy, “you’re a miracle. All life is a miracle.”

Angela Johnson

The floors of the guest bedroom in which she had been locked for the past three days were hardwood and beautiful. When they brought her meals, she tried not to spill anything, not wanting to ruin the floor and compound her punishment for whatever she had done wrong. Sometimes, just to be safe, she would eat her meals in the bathtub of the adjoining bathroom, listening to her parents speaking in the bedroom on the other side of the wall.

“Why haven’t they come to take it back yet?” her father said.

“We never should have let them bring her...it to begin with,” her mother replied. “That was your idea. What if the neighbors find out?”

“I think Tim already knows.”

“How could he? It was so late when they brought it. He couldn’t have been awake at that time of night, could he?”

A moment of silence came between them.

“Imagine what will happen if the firm finds out. This is your fault.”

“I just had to know,” he said, his voice softening. “It looks so much like h—”

“No. Don’t start that again, Mitchell. Not again! I’m calling them again. They need to come and take it away tonight!”

She sat in the corner with her knees pulled to her chest, crying just a little, sorry for whatever she had done, not understanding any of this.

She wondered where they had taken her dresser, her clothes, the posters she had plastered around the room over the years. The walls were painted a soft pastel—something all at once red and pink. The holes left by pushpins, the marks left by tape, the pencil marks on the door frame indicating each year of growth...all of them were gone. Simply painted over.

Four

WHEN THERE WERE so many people and so little air in the room that everyone began to consider the likelihood of tragedy, the noise of the crowd began to grow silent. The silence began at the front doors of the church and marched through the crowd like a virus.

Pastor Peters stood erect—looking as tall and wide as Mount Sinai, Lucille thought—and folded both hands meekly at his waist and waited, with his wife huddled in the shelter of his shadow. Lucille craned her neck to see what was happening. Maybe the devil had finally grown tired of waiting.

“Hello. Hello. Pardon me. Excuse me. Hello. How are you? Excuse me. Pardon me.”

It came like an incantation through the crowd, each word driving back the masses.

“Excuse me. Hello. How are you? Excuse me. Hello...” It was a smooth, dark voice, full of manners and implication. The voice grew louder—or perhaps the silence grew—until there was only the rhythm of the words moving over everything, like a mantra. “Excuse me. Hi, how are you? Pardon me. Hello...”

Without a doubt, it was the well-practiced voice of a government man.

“Good evening, Pastor,” Agent Bellamy said gently, finally breaching the ocean of people.

Lucille sighed, letting go of a breath she did not know she had been holding.

“Ma’am?”

He wore a dark, well-cut gray suit very similar to the one he was wearing on the day he came with Jacob. It wasn’t the kind of suit you see many government men wearing. It was a suit worthy of Hollywood and talk shows and other glamorous things, Lucille mused. “And how’s our boy?” he asked, nodding at Jacob, his smile still as even and square as fresh-cut marble.

“I’m fine, sir,” Jacob said, candy clicking against his teeth.

“That’s good to hear.” He straightened his tie, though it had not been crooked. “That’s very good to hear.”

The soldiers were there then. A pair of boys so young they seemed to be only playing at soldiering. At any moment Lucille expected them to start chasing each other around the pulpit, the way Jacob and the Thompson boy had once done. But the guns asleep at their hips were not toys.

“Thank you for coming,” Pastor Peters said, shaking Agent Bellamy’s hand.

“Wouldn’t have missed it. Thank you for waiting for me. Quite the crowd you’ve got here.”

“They’re just curious,” Pastor Peters said. “We all are. Do you...or, rather, does the Bureau or the government as a whole have anything to say?”

“The government as a whole?” Agent Bellamy asked, not breaking his smile. “You overestimate me. I’m just a poor civil servant. A little black boy from—” he lowered his voice “—New York,” he said, as if everyone in the church, everyone in the town, hadn’t already heard it all in his accent. Still, there was no sense in him wearing it on his sleeve any more than he had to. The South was a strange place.

* * *

The meeting began.

“As you all know,” Pastor Peters began from the front of the church, “we are living in what can only be called interesting times. We are so blessed, to be able to...to witness such miracles and wonders. And make no mistake, that’s what they are—miracles and wonders.” He paced as he spoke, which he always did when he was uncertain about what he was saying. “This is a time worthy of the Old Testament. Not only has Lazarus risen from the grave, but it looks like he’s brought everyone with him!” Pastor Peters stopped and wiped the sweat from the back of his neck.

His wife coughed.

“Something has happened,” he belted out, startling the church. “Something—the cause of which we have not yet been made privy—has happened.” He spread his arms. “And what are we to do? How are we to react? Should we be afraid? These are uncertain times, and it’s only natural to be frightened of uncertain things. But what do we do with that fear?” He walked to the front pew where Lucille and Jacob were sitting, his hard-soled shoes sliding silently over the old burgundy carpet. He took the handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his brow, smiling down at Jacob.

“We temper our fear with patience,” he said. “That is what we do.”

It was very important to mention patience, the pastor reminded himself. He took Jacob’s hand, being sure that even those in the back of the church, those who could not see, had time enough to be told what he was doing, how he was speaking of patience as he held the hand of the boy who had been dead for half a century and who was now, suddenly, peacefully sucking candy in the front of the church, in the very shadow of the cross. The pastor’s eyes moved around the room and the crowd followed him. One by one he looked at the other Returned who were there, so that everyone might see how large the situation already was. In spite of the fact that, initially, they were not supposed to be there. They were real, not imagined. Undeniable. Even that was important for people to understand.

Patience was one of the hardest things for anyone to understand, Pastor Peters knew. And it was even harder to practice. He felt that he himself was the least patient of all. Not one word he said seemed to matter or make sense, but he had his flock to tend to, he had his part to play. And he needed to keep her off his mind.

He finally planted his feet and pushed the image of her face from his mind. “There is a lot of potential and, worse yet, there is a lot of opportunity for rash thoughts and rash behavior in these times of uncertainty. You only need to turn on the television to see how frightened everyone is, to see how some people are behaving, the things they’re doing out of fear.

“I hate to say that we are afraid, but we are. I hate to say that we can be rash, but we can. I hate to say that we want to do things we know we should not do, but it’s the truth.”

* * *

In his mind, she was sprawled out on the thick, low-hung bough of an oak tree like a predatory cat. He stood on the ground, just a boy then, looking up at her as she dangled one arm down toward him. He was so very afraid. Afraid of heights. Afraid of her and the way she made him feel. Afraid of himself, as all children are. Afraid of...

* * *

“Pastor?”

It was Lucille.

The great oak tree, the sun bubbling through the canopy, the wet, green grass, the young girl—all of them disappeared. Pastor Peters sighed, holding his empty hands in front of him.

“What are we gonna do with ’em?” Fred Green barked from the center of the church. Everyone turned to face him. He removed his tattered cap and straightened his khaki-colored work shirt. “They ain’t right!” he continued, his mouth pulled tight as a rusty letterbox. His hair had long since abandoned him, and his nose was large, his eyes small—all of which conspired together over the years to give him sharp, cruel features. “What are we gonna do with ’em?”

“We’re going to be patient,” Pastor Peters said. He thought of mentioning the Wilson family in back of the church. But that family had a special meaning for the town of Arcadia and, for now, it was best to keep them out of sight.

“Be patient?” Fred’s eyes went wide. A tremble ran over him. “When the Devil himself shows up at our front door you want us to be patient? You want us to be patient, here and now, in the End Times!” Fred looked not at Pastor Peters as he spoke, but at the audience. He turned in a small circle, pulling the crowd into himself, making sure that each of them could see what was in his eyes. “He wants patience at a time like this!”

“Now, now,” Pastor Peters said. “Let’s not start up about the ‘End Times.’ And let’s not go into calling these poor people devils. They’re mysteries, that’s for certain. They may even be miracles. But right now, it’s too soon for anyone to get a handle on anything. There’s too much we don’t know and the last thing we need is to start a panic here. You heard about what happened in Dallas, all those people hurt—Returned and regular people, as well. All of them gone. We can’t have something like that happen here. Not in Arcadia.”

“If you ask me, them folks in Dallas did what needed to be done.”

The church was alive. In the pews, along the walls, at the back of the church, everyone was grumbling in agreement with Fred or, at the very least, in agreement with his passion.

Pastor Peters lifted his hands and motioned for the crowd to calm. It dulled for a moment, only to rise again.

Lucille wrapped an arm around Jacob and pulled him closer, shuddering at the sudden recollection of the image of Returned—grown folks and children alike—laid out, bloodied and bruised, on the sun-warmed streets of Dallas.

She stroked Jacob’s head and hummed some tune she could not name. She felt the eyes of the townspeople on Jacob. The longer they looked, the harder their faces became. Lips sneered and brows fell into outright scowls. All the while the boy only went about the business of resting in the curve of his mother’s arm, where he pondered nothing more important than glazed peaches.

Things wouldn’t be so complex, Lucille thought, if she could hide the fact of him being one of the Returned. If only he could pass for just another child. But even if the entirety of the town didn’t know her personal history, didn’t know about the tragedy that befell her and Harold on August 15, 1966, there was no way to hide what Jacob was. The living always knew the Returned.

Fred Green went on about the temptation of the Returned, about how they weren’t to be trusted.

In Pastor Peters’s mind were all manner of scripture and proverb and canonical anecdote to serve as counterargument, but this wasn’t the church congregation. This wasn’t Sunday morning service. This was a town meeting for a town that had become disoriented in the midst of a global epidemic. An epidemic that, if there were any justice in the world, would have passed this town by, would have swept through the civilized world, through the larger cities, through New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, London, Paris. All the places where large, important things were supposed to happen.

“I say we round them all up somewhere,” Fred said, shaking a square, wrinkled fist at the air as a crowd of younger men huddled around him, nodding and grunting in agreement. “Maybe in the schoolhouse. Or maybe in this church here since, to hear the pastor tell it, God ain’t got no gripe with them.”

Pastor Peters did something then which was rare for him. He yelled. He yelled so loud the church shrank into silence and his small, frail wife took several small steps back.

“And then what?” he asked. “And then what happens to them? We lock them up in a building somewhere, and then what? What’s next?

“How long do we hold them? A couple of days? A week? Two weeks? A month? Until this ends? And when will that be? When will the dead stop returning? And when will Arcadia be full up? When will everyone who has ever lived here come back? This little community of ours is, what, a hundred and fifty? A hundred and seventy years old? How many people is that? How many can we hold? How many can we feed and for how long?

“And what happens when the Returned aren’t just our own anymore? You all know what’s happening. When they come back, it’s hardly ever to the place that they lived in life. So not only will we find ourselves opening our doors to those for whom this event is a homecoming, but also for those who are simply lost and in need of direction. The lonely. The ones untethered, even among the Returned. Remember the Japanese fellow over in Bladen County? Where is he now? Not in Japan, but still in Bladen County. Living with a family that was kind enough to take him in. And why? Simply because he didn’t want to go home. Whatever his life was when he died, he wanted something else. And, by the graces of good people willing to show kindness, he’s got a chance to get it back.

“I’d pay you good money, Fred Green, to explain that one! And don’t you dare start going on about how ‘a Chinaman’s mind ain’t like ours,’ you racist old fool!”

He could see the spark of reason and consideration—the possibility for patience—in their eyes. “So what happens when there isn’t anywhere else for them to go? What happens when the dead outnumber the living?”

“That’s exactly what I’m talking about,” Fred Green said. “What happens when the dead outnumber the living? What’ll they do with us? What happens when we’re at their mercy?”

“If that happens, and there’s no promise that it will, but if it does, we’ll hope that they’ll have been shown a good example of what mercy is...by us.”

“That’s a goddamn fool answer! And Lord forgive me for saying that right here in the church. But it’s the truth. It’s a goddamn fool answer!”

The volume in the church rose again. Yammering and grumbling and blind presupposing. Pastor Peters looked over at Agent Bellamy. Where God was failing, the government should pick up the slack.