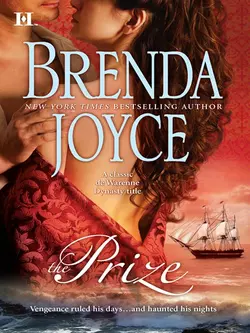

The Prize

Бренда Джойс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 305.03 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An infamous sea captain of the British Royal Navy, Devlin O′Neill is consumed with the need to destroy the man who brutally murdered his father.Having nearly ruined the Earl of Eastleigh financially, he is waiting to strike the final blow. And his opportunity comes in the form of a spirited young American woman, the earl′s niece, who is about to set his cold, calculating world on fire….Born and raised on a tobacco plantation, orphan Virginia Hughes is determined to rebuild her beloved Sweet Briar. Daringly, she sails to England alone, hoping to convince her uncle to lend her the funds. Instead, she finds herself ruthlessly kidnapped by the notorious Devlin O′Neill, and will soon find her best-laid plans thwarted by a passion that could seal their fates forever….