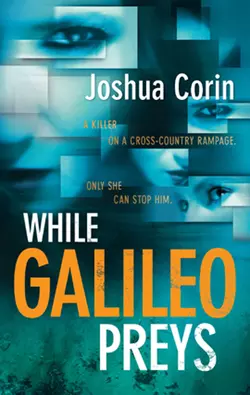

While Galileo Preys

Joshua Corin

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: If there were a God, he would have stopped me.That′s the message discovered atop an elementary school in downtown Atlanta. Across the street are the bodies of fourteen people, each quickly and cleanly murdered. The sniper Galileo is on the loose. He can end a life from hundreds of yards away. And he is just getting started.Where others see puzzles, Esme Stuart sees patterns. These outside-the-box inductive skills made her one of the FBI′s top field operatives. But she turned her back on all that eight years ago to start a family and live a normal life. She now has a husband, a daughter and a Long Island home to call her own, far removed from the bloody streets of Atlanta.But Galileo′s murders escalate and her old boss needs the help of his former protege. But how can she turn her back on her well-earned quiet life? How would she be able to justify such a choice to her husband? To her daughter?And what will happen when Galileo turns his scope on them?