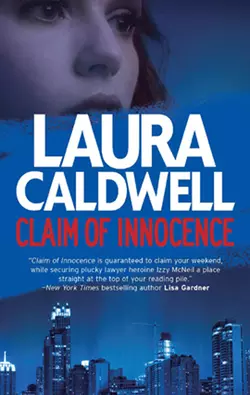

Claim of Innocence

Laura Caldwell

Forbidden relationships are the most tempting. And the most dangerous.It was a crime of passion–or so the police say. Valerie Solara has been charged with poisoning her best friend. The prosecution claims she's always been secretly attracted to Amanda's husband…and with Amanda gone, she planned to make her move.Attorney Izzy McNeil left the legal world a year ago, but a friend's request pulls her into the murder trial. Izzy knows how passion can turn your life upside down. She thought she had it once with her ex-fiancé, Sam. Now she wonders if that's all she has in common with her criminally gorgeous younger boyfriend, Theo.It's Izzy's job to present the facts that will exonerate her client–whether or not she's innocent. But when she suspects Valerie is hiding something, she begins investigating–and uncovers a web of secret passions and dark motives, where seemingly innocent relationships can prove poisonous…

Praise for Laura Caldwell’s IZZY MCNEIL novels

Red, White & Dead

“A sizzling roller coaster ride through the streets of Chicago, filled with murder, mystery, sex and heartbreak. These page-turners will have you breathless and panting for more.”

—Shore Magazine

“Chock full of suspense, Red, White & Dead is a riveting mystery of crime, love, and adventure at its best.”

—New York Times bestselling author Gayle Lynds

Red Blooded Murder

“Smart dialogue, captivating images, realistic settings and sexy characters… The pieces of the puzzle come together to reveal the secrets between the sheets that lead Izzy to realize who the killer is.”

—BookReporter.com

“Red Blooded Murder aims for the sweet spot between tough and tender, between thrills and thought—and hits the bull’s-eye. A terrific novel.”

—#1 New York Times bestselling author Lee Child

“Izzy is the whole package: feminine and sexy, but also smart, tough and resourceful. She’s no damsel-in-distress from a tawdry bodice ripper; she’s more than a fitting match for any bad guys foolish enough to take her on.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

Red Hot Lies

“Caldwell’s stylish, fast-paced writing grips you and won’t let you go.”

—Edgar Award–winning author David Ellis

“Told mainly from the heroine’s first-person point of view, this beautifully crafted and tightly written story is a fabulous read. It’s very difficult to put down—and the ending is terrific.”

—RT Book Reviews

“Former trial lawyer Caldwell launches a mystery series that weaves the emotional appeal of her chick-lit titles with the blinding speed of her thrillers… Readers will be left looking forward to another heart-pounding ride on Izzy’s silver Vespa.”

—Publishers Weekly

Claim Of Innocence

Laura Caldwell

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Acknowledgments

1

“I zzy,” my friend Maggie said, “I need you to try this murder case with me. Now.”

“What?” I shifted my cell phone to my other ear, not sure I’d heard her right. I had never tried a criminal case before—not even a parking ticket, much less a murder trial.

“Yeah,” she said. “Right now.”

It was a hot August Thursday in Chicago, and I had just left the civil courthouse. I had taken three steps into the Daley Center Plaza, looked up at the massive Picasso sculpture—an odd copper thing that looked half bird, half dog—and I actually said to it, “I’m back.”

I’d argued against a Motion to Dismiss for Maggie. She normally wouldn’t have filed a civil case, but she’d done so as a favor to a relative. I lost the motion, something that would have burned me in days of yore, but instead I was triumphant. Having been out of the law for nearly a year, I’d wondered if I had lost it—lost the ability to argue, to analyze information second-to-second, to change course and make it look like you’d planned it all along. I had worried that perhaps not going to court was like not having sex for a while. At first, you missed it deeply but then it became more difficult to remember what it was like with each passing day. Not that I was having that particular problem.

But really, when I’d seen the burning sun glinting off the Picasso and I stated boldly that I was back in action, I meant it figuratively. I was riding off the fact that although Maggie’s opponent had won the motion, and the complaint temporarily dismissed, Judge Maddux had said, “Nice argument, counsel” to me, his wise, blue eyes sparkling.

Judge Maddux had seen every kind of case in his decades of practice and every kind of lawyer. His job involved watching people duke it out, day after day after day. For him to say “Nice argument” was a victory. It meant I still had it.

As I walked through the plaza, the heat curling my red hair into coils, I had called Maggie. She was about to pick a jury at 26th and Cal on a murder case, so her voice was rushed. “Jesus, I’m glad you called,” she said.

Normally, Maggie Bristol would not have answered her phone right before the start of a criminal trial, even if she was curious about the motion I’d handled for her. But she knew I was nervous to appear in court—something I used to do with such regularity the experience would have barely registered. She was answering, I thought, to see how I was doing.

“It went great!” I said.

I told her then that I was a “lawyer for hire.” Civil or criminal, I said, it didn’t matter. And though I’d only practiced civil before, I was willing to learn anything.

Since leaving the legal world a year ago, I’d tried many things—part-time assignments from a private investigator named John Mayburn and being a reporter for Trial TV, a legal network. I liked the TV gig until the lead newscaster, my friend Jane Augustine, was killed and I was suspected in her murder. By the time my name was cleared, I wasn’t interested in the spotlight anymore.

So the reporter thing hadn’t worked out, and the work with Mayburn was streaky. Plus, lately it was all surveillance, which was a complete snooze. “I miss the law,” I told Maggie from the plaza. “I want back in.”

Which was when she spoke those words—I need you to try this murder case with me. Now.

I glanced up at the Picasso once more, and I knew my world was about to change. Again.

2

O ver the years, it became disquieting—how easy the killing was, how clean.

He had always lived and worked in an antiseptic environment, distanced from the actual act of ending a life. They were usually killed in the middle of the night. But he never slept on those nights anyway, even though he wasn’t there. He twisted in his bed. The only way he knew when they were dead was when he got the phone call. The person on the line would state simply, “He’s gone.”

He would thank them, hang up and then he would go on, as if he hadn’t just killed someone.

But then he’d reached a point when he wanted to make it real. He wanted to see it.

And so he went to watch. He remembered that he had walked across the yard, toward the house. In the eerie, moonless night it seemed as if he heard a chorus of voices—formless cries, no words, just shouts and calls, echoes that sounded like pain itself.

He had stopped walking then. He listened. Was he really hearing that? Something rose up inside him, choked him. But he gulped it down. And then he kept moving toward the house.

3

A h, 26th and Cal. You could almost smell the place as you neared it—a scent of desperation, of seediness, of excitement.

Other parts of the city now boasted an end-of-the-summer lushness—bushes full and vividly green, flowers bright and bursting from boxes, tree branches draping languidly over the streets. But out here at 26th and Cal, cigarette butts, old newspapers and crushed cans littered the sidewalks, all of them leading to one place.

Chicago’s Criminal Courts Building was actually two buildings mashed together—one old, stately and slightly decrepit, the other a boxy, unimaginative, brownish structure better suited to an office park in the burbs.

The last time I’d been here was as a reporter for Trial TV, covering my first story. Now I flashed my attorney ID to the sheriff and headed toward the elevators, thinking that I liked this feeling better—that of being a lawyer, a participant, not just an observer.

I passed through the utilitarian part of the building into the old section with its black marble columns and brass lamps, the ceiling frescoed in sky-blue and orange. As I neared the elevator banks, my phone vibrated in my bag, and I pulled it out, thinking it was Maggie.

But it was Sam. Sam, who I nearly married a year ago. Sam, the guy I’d happily thought I’d spend the rest of my life with. Sam, who had disappeared when we were engaged. Although I eventually understood his reasons, I hadn’t been able to catch up in the aftermath of it all. I wanted more time. He wanted things to be the way they’d been before. We’d finally realized that the pieces of Sam and Izzy, Izzy and Sam no longer fit together.

I looked at the display of the phone, announcing his name. I knew I had to get upstairs. I knew I was involved with someone else now. But I hadn’t talked to Sam in a while. And the fact was, his pull was hard to avoid.

I took a step toward a marble wall and leaned my back on it, answering the phone. “Hey. How are you?”

“Hi, Red Hot.” His nickname for me twinged something inside, some mix of fond longing and gently nagging regrets. We had a minute or two of light, meaningless banter—How are you? Great. Yeah, me, too. Good. Good. Then Sam said, “Can I talk to you about something?”

“Sure, but I’m in the courthouse. About to try a case with Maggie.” I told him quickly about Maggie’s phone call. I told him that Maggie’s grandfather, who was also her law partner, had been working extra hard on the murder case. Martin Bristol, a prosecutor-turned-criminal-lawyer, was in his seventies, but he’d always been the picture of vigor, his white hair full, his skin healthy, still wearing his expensive suits with a confident posture. But that day, Maggie said he’d not only seemed weak but he’d almost fainted. He’d denied anything was wrong, but Maggie sensed differently. And now here I was at 26th and Cal.

“You’re kidding?” Sam had always been excited for me when I was doing anything interesting in the legal realm. It was Sam who had reminded me on more than one occasion over the last year that I was a lawyer—that I should make my way back to the law. “This is incredible, Iz,” Sam said. “How do you feel?”

And then, right then, we were back to Sam and Izzy, Izzy and Sam. I told him the thought of being back in a courtroom was making my skin prickle with nerves but how that anxiety was also battling something that felt like pure adrenaline. I told him that adrenaline was something I had feared a little, back in the days when I was representing Pickett Enterprises, a Midwest media conglomeration.

“You’ve always been a thrill seeker,” Sam said. “You jumped in with both feet when Forester starting giving you cases to handle.”

We were silent for a second, and I knew we were remembering Forester Pickett, whom we had both worked for, whom we had both loved and who had been dead almost a year now.

“You didn’t even know what you were doing,” Sam continued, “yet you just charged in there and took on everything.”

“But when I was on trial or negotiating some big contract and the adrenaline would start surging, sometimes it felt like too much. And now…” I thought about trying a case again and I let the adrenaline wash over me. “I like it.”

“You’re using it to fuel you.”

“Exactly.”

This was not a conversation I would have had with Theo, my boyfriend. It was not a conversation I would have had even with Maggie. It felt damned good.

I looked at my watch. “I need to go.”

A pause. “Call me later? I kind of…well, I have some news.”

I felt a sinking in my stomach, for which I didn’t know the reason. “What is it?”

“You’ve got to go. I’ll tell you later.”

“No, now.”

Another pause.

“Seriously,” I said. “You know I hate when people say they want to talk and then don’t tell you what they want to talk about.”

He exhaled loud. I’d heard that exhale many times. I could imagine him closing his green, green eyes as he breathed, maybe running his hands through his blond hair, which would be white-gold now from the summer sun.

“Okay, Iz,” he said. “I know this isn’t the right time for this, but…I’m probably moving out of Chicago.”

“Where? And why?”

But then I knew.

“It’s for Alyssa,” I said, no question mark at the end of that statement. I suddenly knew for certain that this news of his had everything to do with Alyssa, his tiny, blonde, high-school sweetheart. His girlfriend since we’d called off our engagement.

And with that thought, I knew something else, too. “You’re engaged.”

His silence told me I was right.

“Well, congratulations,” I said, as though it didn’t matter, but my stomach felt crimped with pain. “So when is the big date?”

He didn’t say anything for second. Then, “That’s why I had to call you. There’s not going to be a date.”

I felt my forehead crease with confusion. Across the foyer, I saw a sheriff walking toward me with a stern expression. I knew he would tell me to move along. They didn’t like people standing in one place for too long at 26th and Cal.

“There’s not going to be a date,” Sam repeated. “Not if you don’t want there to be.”

4

I got in the elevator with two sullen-looking teenagers. I needed to focus on Maggie’s case and put my game face on. I couldn’t think about my conversation with Sam right now, so I tuned in to the teenagers’ conversation.

“What you got?” one said.

The other shrugged. “Armed robbery. My PD says take the plea.”

“Why you got a public defender if you out on bail?” The first kid sounded indignant. “If you can get bail, you can get a real lawyer.”

The other shook his head. “Nah. My auntie says she won’t pay no more.”

“Damn.” He shook his head.

“Yeah.”

They both looked at me then. I tried to give a hey-there, howdy kind of look, but they weren’t really hey-there, howdy kind of guys. One of the teenagers stared at my hair, the other my breasts. I was wearing a crisp, white suit that I’d thought perfect for a summer day in court, but when I looked down, I realized that one of the buttons of my navy blue blouse had popped open and I was showing cleavage. I grasped the sides of the blouse together with my hand, and when the elevator reached my floor, I dodged out.

Although I was still in the old section of the courthouse, that floor must have been remodeled a few decades ago, and its hallways now bore a staid, uninspired, almost hospitalish look with yellow walls and tan linoleum floors. I searched for Maggie’s courtroom. When I found it and stepped inside, I felt a little deflated. Last year, when I’d been here for Trial TV, the case was on the sixth floor in one of the huge, two-story, oak-clad courtrooms with soaring windows. This courtroom was beige—from the spectators’ benches, which were separated from the rest of the courtroom by a curved wall of beige Plexiglas, to the beige-gray industrial carpet to the beige-ish fabric on the walls to the beige-yellow glow emanating with a faint high pitch from the fluorescent lights. A few small windows at the far side of the benches let in the only other light, which bounced off the Plexiglas, causing the few people sitting there to have to shift around to avoid it.

Maggie was in the front of the courtroom on the other side of the Plexiglas at one of the counsel’s tables. She was tiny, barely five feet tall, and with her curly, chin-length hair, she almost looked like a kid swimming in her too-loose, pin-striped suit. But Maggie certainly didn’t act like a kid in the courtroom. Anyone who thought she did or underestimated her in any way ended up on the losing end of that scuffle.

No one was behind the high, elongated judge’s bench. At another counsel’s table were two women who must have been assistant state’s attorneys—you could tell by the carts next to their tables, which were laden with accordion folders marked First Degree Murder, as if the verdict had already been rendered. The state’s attorneys were talking, but I couldn’t hear them. The room, I realized, was soundproof. The judge probably had to turn on the audio in order for anything to be heard by the viewers.

I walked past the spectator pews and pushed one of the glass double-doors to greet Maggie. The door screeched opened half an inch, then stopped abruptly.

Maggie looked up, then pointed at the other door. I suddenly remembered a law professor Maggie and I had at Loyola Chicago. The professor had stood in front of an Advanced Litigation class and said the most important thing she could teach us, if we planned to practice in Cook County, was Always push the door with the lock. I’d found she was right. At the Daley Center, where most of the larger civil cases were held, there were always double doors. One of them always had a lock on it, and that one was always unlocked. If you pushed the other, you inevitably banged into it and looked like an ass, and in the world of litigation, where confidence was not only prized but required, you didn’t want that.

From what I had learned through Maggie, though, Chicago’s criminal courts didn’t run like anyone else’s, so I hadn’t thought about the door thing. More than anything, though, I was probably just out of practice. I gave Maggie a curt nod to say, I got it, then pushed the correct door and stepped into the courtroom.

The state’s attorneys turned and eyed me. One, I guessed, was in her forties, but her stern expression and steely glare made her seem older. She wore a brown pant-suit and low heels. The woman with her was younger, a brunette with long hair, who was probably a few years out of law school—enough time to give her the assurance to appraise me in the same frank way as her colleague, but with a lot less glare.

Maggie stepped toward me, gesturing toward the woman in brown who had short, frosted hair cut in a no-nonsense fashion and whose only makeup was a slash of maroonish lipstick. “Ellie Whelan,” she said, “and Tania Castle.” She gestured toward the brunette. “This is Izzie McNeil. She’ll be trying the case with us.”

Both the women looked surprised.

“With you and Marty?” Ellie said, referring to Maggie’s grandfather.

Maggie grunted in sort of a half agreement.

“Haven’t I met you?” the brunette said to me, her eyes trailing over my hair, my face.

“Yeah…” Ellie said, doing the same.

I used to have to make occasional TV statements in my former role as an entertainment lawyer for Pickett Enterprises. But after Jane Augustine’s murder last spring, my face had been splashed across the news more than once. Sometimes I still drew glances of recognition from people on the street. The good thing was most couldn’t exactly place me.

I was about to explain, but Maggie said, “Oh, definitely. She’s been on a ton of high-profile cases.” She threw me a glance as if to say, Leave it at that.

I drew Maggie to her table—our counsel’s table, I should say. “Where’s your grandfather?”

Maggie’s face grew serious. She glanced over her shoulder at a closed door to the right of the judge’s bench. “He’s in the order room. Said he wanted a little time to himself.” She looked at her watch. “The judge gave us a break. Let’s go see how Marty’s doing.” Maggie called her grandfather by his first name during work hours. Maggie and her grandfather had successfully defended alleged murderers, drug lords and Mafioso. They were both staunch believers in the constitutional tenets that gave every defendant the right to a fair arrest and a fair trial. Those staunch beliefs had made them a hell of a lot of money.

I put my hand on her arm to stop her. “Wait, Mags,” I said, my voice low. “Tell me what’s been going on.”

She blew out a big breath of air, puffing her wheat-blond curly bangs away from her face. “I really don’t know. He’s been working around the clock on this case. Harder than I’ve ever seen him work.”

“That’s saying something. Your grandfather is one of the hardest-working lawyers in town.”

“I know!” She bit her bottom lip. “This case just seemed to grab him from the beginning. He heard about it on the news and told me we had to represent Valerie even though she already had a lawyer.” Maggie named an attorney who was considered excellent. “My grandfather went to the other lawyer and talked her out of the case. And he’s been working on it constantly for the last ten months. I’m talking weekends and nights, even coming into the office in the middle of the night sometimes.” Maggie shook her head. “I think he pushed himself too much, and he’s finally feeling his age.”

“That’s hard.”

Maggie nodded, then shrugged. “So that’s basically it. I was ready to handle the opening arguments today after we picked the jury. And we had all the witnesses divided. But we got here and he started talking to our client, and his knees just buckled. He almost went down. I had to catch him.” More chewing her bottom lip, this time on the corner of it. “It was so sad, Iz. He gave me this look… I can’t describe it, but he looked scared.”

I think we were both scared then. Maggie’s grandfather had always held a tinge of the immortal. He was the patriarch of the family, the patriarch of the firm. No one ever gave thought to him not being around. It was impossible to imagine.

“Shouldn’t he see a doctor?” I asked.

“That’s what I said, but he seemed to recover quickly, and he said he wouldn’t go to the hospital or anything. You know how he is.”

“Yeah. It would be tough to force him.”

“Real tough.”

“Okay,” I said, putting on a brusque voice and standing taller. “Well, before we talk to your grandfather, update me on the case. Who is your client?”

Another exhale from Maggie sent her bangs away from her forehead. She looked over her shoulder to see if anyone was near us. The state’s attorneys were on the far side of their table now, one talking on a cell phone, the other paging though a transcript.

“Her name is Valerie Solara,” Maggie said. “She’s charged with killing her friend, Amanda Miller.”

“How did the friend die?”

“Poisoned.”

“Wow.”

“Yeah. It was put in her food. The state’s theory is that Valerie wanted Amanda out of the way because she was in love with Amanda’s husband, Zavy.”

“Zavy?”

“Short for Xavier.”

“Any proof Valerie did it?”

“The husband will testify Valerie made overtures toward him prior to the murder, which he turned down. A friend of Amanda and Valerie’s will testify that Valerie asked her about poisons. Valerie was the one cooking the food that day with Amanda. It was her recipe, and she was teaching it to Amanda. Toxicology shows the food was deliberately contaminated and that caused Amanda’s death.”

“What does your client say?”

“Not much. Just that she didn’t do it.”

“What do you mean not much? How are we going to mount a defense if she won’t say much?”

“We handle this case the same as any other,” Maggie said. “First, we ask the client what happened. Then the client chooses what to tell us. Usually we don’t even ask the ultimate question about guilt or innocence because we don’t need to know. Our defense is almost always that the state didn’t meet their burden of proof.”

“So you never asked her if she did it or not?”

“She says she didn’t. Told us that first thing.”

“If she didn’t, who did?”

“She hasn’t given us a theory.”

Just then, a sheriff stepped into the courtroom. “All rise!”

The judge—a beefy, gray-haired guy in his early fifties—zipped up his robe over a white shirt and light blue tie as he stepped up to the bench.

“The Circuit Court of Cook County is now in session,” the sheriff bellowed, “the Honorable—”

The judge held his hand out to the sheriff and shook his head dismissively. The sheriff looked wounded but clapped his mouth shut.

“Judge Bates,” Maggie whispered. “He hates pomp and circumstance. New sheriff.”

I nodded and turned toward the judge, hands behind my back.

“Counsel, where are we?” the judge said.

Maggie stepped toward the bench and introduced me as another lawyer who would be filing an appearance on behalf of Valerie Solara. That drew a grouchy look from the judge.

“Hold on,” he said. “Let’s get this on the record.” He directed the sheriff to call the court reporter. A few seconds later, she scurried into the room with her machine, and Maggie went through the whole introduction again on the record.

“Fine,” the judge said when she was done, “now you’ve got three lawyers. More than enough to voie dire our jury panels.” The judge looked at the sheriff. “Call ’em in.”

“Excuse me, Judge,” Maggie said, taking a step toward the bench. “If we could have just five more minutes, we’ll be ready.”

Judge Bates sat back in his chair, regarding Maggie with a frown. He looked at the state’s attorneys for their response.

Ellie Whelan stepped forward. “Judge, this has taken too long already. The state is prepared, and we’d like to pick the jury immediately.”

The judge frowned again. I could tell he wanted to deny Maggie’s request, but Martin Bristol carried a lot of weight in Chicago courtrooms, even if he wasn’t present at the moment. “Five minutes,” the judge barked. He looked pointedly at Maggie. “And that’s it.” When the judge had left the bench, Maggie nodded at the door of the order room. “C’mon. Let’s go see how Marty’s doing. It will help that you’re going to try this case. You’re one of his favorites.”

We walked to the door, and Maggie swung it open. Martin Bristol sat at a table, a blank notepad in front of him. He was hunched over in a way I’d never seen before, his skin grayish. When he saw us, he straightened and blinked fast, as if trying to wake himself up.

“Izzy,” he said with a smile that showed still-white teeth. “What are you doing here?”

“Izzy’s looking for work, so I’m going to toss her some scraps.” Maggie shot me a glance. She wanted it to seem as if she was hiring me as a favor, not as a way to save her grandfather.

“I’d really appreciate it,” I said.

“Of course,” Martin said. “Anything for you, Izzy.” His posture slumped again, the weight of his shoulders appearing too much to hold.

“Mr. Bristol, are you all right?”

Maggie took a seat on one side of him. After a moment, I sat on the other side, a respectful distance away.

A moment later, when he’d still said nothing, Maggie put her hand on his arm. “Marty?”

Again, he didn’t respond, just stared at the empty legal pad, his mouth curling into a shell of sadness.

There was a rap on the door and the sheriff stuck his face into the room. “He’s had it,” he said, referring to the judge. “We’re bringing in the prospective jurors now.”

Maggie’s eyes were still on her grandfather. “Izzy and I can handle the voie dire. We may not open until tomorrow, so why don’t you go home?”

He sat up a little. “What have I always told you about jury selection?”

“That it’s the most important part of the trial,” Maggie said, as if by rote.

“Exactly.” He straightened more but didn’t stand.

“I think you should go home. Get some rest.”

His gaze moved to Maggie’s. I thought he would immediately reject the notion, but he only said simply, “Maybe.”

“Let us handle it.” Maggie nodded toward the courtroom. “I’ve already told the judge that Izzy was filing an appearance.”

Again, I waited for swift rejection, but Martin Bristol nodded. “Just this one time.”

“Just this once,” Maggie said softly.

Martin pushed down on the table with his hands, shoving himself to his feet. “I’ll explain to Judge Bates.” He slowly left the room.

Maggie’s round eyes, fringed with long brown lashes, watched him. Then she met my gaze across the table. “You ready for this?”

My pulse quickened. “No.”

“Good,” she said, standing. “Let’s get out there.”

5

“H ow’s Theo?” Maggie asked as the sheriff led a panel of about fourteen potential jurors through the Plexiglas doors and into the courtroom. Theo was the twenty-two-year-old guy I’d been dating since spring.

“Um…” I said, eyeing the potential jurors. “He’s fine. So what’s your strategy here? Did you do a mock trial for this? Do you know what kind of juror you want?”

As was typical, the possible jurors being led in were a completely mixed bag—people of every color and age. I remembered a story my friend, Grady, once told me about defending a doctor who had been sued. As they were about to start opening arguments, the doctor had looked at the jury and then looked at Grady. “Well, that’s exactly a jury of my peers,” the doc had said sarcastically.

When Grady told me the story, we both thought the doctor arrogant, but we understood what he meant. Chicago was a metropolis that was home to every type of person imaginable. As a result, you never knew what you were going to get when you picked a jury in Cook County. “Unpredictable” was the only way to describe a jury in this city.

“We talked to a jury consultant,” Maggie said, answering my question, “but tell me, what’s going on with Theo?”

I turned to her. “Why are you asking this now?”

“My grandfather always taught me to have two seconds of normal chitchat right before a trial starts.”

“Why?”

“Because for the rest of the trial you become incapable of it and because it calms you down.” She peered into my eyes. “And I think you could use some of that.”

“Why? I’m fine.” But I could feel my pulse continue its fast pace.

She peered even more closely. “You’re not going to have one of those sweat attacks, are you?”

I glared at her. But she had a right to ask. I had this very occasional but acute nervousness problem that caused me to, essentially, sweat my ass off. It usually happened at the start of a trial, and it was mortifying. I’d always said it was as if the devil had taken a coal straight from the furnace of hell and plopped it onto my belly.

I paused a moment and searched my body for any internal boiling. “No, I think I’m fine.”

The sheriff barked orders at the jurors about where to sit.

“If it’s a tradition,” I said, “the chitchat thing, then we should do it.”

Maggie nodded.

“So Theo is good,” I said. I got a flash of him—young, tall, muscled Theo, with tattoos on his arms—a gold-and-black serpent on one, twisting ribbons of red on the other. I could see his light brown hair that he wore to his chin now, his gorgeous, gorgeous, gorgeous face, those lips…

I shook my head to halt my thinking. If I didn’t stop, my internal heat would definitely rise. “Actually, I have more to talk about in terms of Sam.”

“Really? I thought you hadn’t seen him much.”

“I haven’t. He called this morning.”

“Hmm,” Maggie said noncommittally, her hands tidying stacks of documents. “How is he?”

“Engaged.”

Maggie’s chin darted forward, the muscles in her neck standing out. Her eyes went wide and shot from one of mine to the other and back again, looking for signs, I supposed, of impending sobbing. Finding none—I think I was still too shocked—she asked, “Alyssa?”

I nodded.

“Oh, my gosh. I’m so sorry, Iz.”

Maggie’s gaze was worried. She knew the ins and outs of Sam and me from start to finish. After Sam and I broke up, she was one of the few friends who understood that I still adored him, even as I felt I couldn’t continue our relationship. Eventually, I put that relationship away, in my past, likely never to be seen in my future. But here it was in my present.

“Where are they getting married?” Maggie asked. “And when?”

“Well, that’s the thing. He says he won’t set a date. Not if I don’t want there to be a date.”

And then I saw something remarkable, something I’d seen only once or twice before—Maggie Bristol, who was never at a loss for words, stared at me, her mouth open. Not a sound emanated from within. Not even when the judge shouted at her.

“Counsel,” the judge called to Maggie again, this time very loud. “Is. Your. Client. Here?” he said, enunciating.

Maggie finally dropped her eyes from me, picked up a cell phone and glanced at it. “Yes, Your Honor. One moment please.” Maggie gestured at me to walk with her.

“Where is your client?” I whispered.

“Our client,” Maggie whispered back. “She gets emotional when she’s in the courtroom so we try to keep her out until it’s absolutely necessary. I have someone from our office sit with her in an empty courtroom, then I text them to get her down here.” She put her hand on my arm. “We’ll have to table this discussion of Sam.”

“Of course. Forget I said anything.”

She scoffed as she led us past the gallery pews, all filled with more prospective jurors. I knew what she meant—it was hard for me to think of anything but Sam. Sam’s voice. Sam, saying he still wanted to be with me after everything.

I forced myself to focus instead on all those people in the pews, watching us like actors on a stage. And in a way litigation was a performance. I knew exactly what production Maggie wanted us to act in right now. She wanted us to make a show of solidarity—the two women lawyers about to greet their female client.

I threw my shoulders back, banned Sam Hollings from my mind again and smiled pleasantly at a few of the potential jurors as I followed Maggie to the courtroom door. I spied a couple of reporters scribbling in notepads. “I’m surprised there isn’t more media,” I whispered to Maggie.

“We’ve been trying to keep it low-key. We haven’t made a statement to the press, and Valerie hasn’t, either.”

As we stepped into the hallway, Maggie was stopped by a man with bright eyes who must have been at least eighty. I recognized him as a famous judge who had stepped down over a decade ago but was always being profiled in the bar magazines as someone who spent his retirement watching over the criminal courthouse where he had presided for so long.

“Hey, Judge!” Maggie said casually, shaking his hand and patting him on the arm. “How’s the golf game?”

“Terrible this summer!”

“It’s always been terrible, sir.”

The judge laughed. Maggie was like this at work—irreverent in a respectful kind of way. But she had an immediacy to her and a clear-cut way of speaking to people like judges, other attorneys and politicos, as if she had been intimately involved on their level for decades.

The judge moved on. A few steps later, I saw Maggie’s receptionist, whom I knew from my frequent visits to Martin Bristol & Associates. “Hi,” I said to her, but stopped short in my greeting when I saw the woman next to her.

Valerie Solara was a beautiful woman. She had golden-brown skin and eyes that were so dark they were almost black. Her gleaming ebony hair was pulled away from her face, showing her high cheekbones, her elegantly curved jaw. She wore a brown dress with tiny, ivory polka dots and a wide leather belt. But it wasn’t so much her beauty that struck me. It was the feel of her—some kind of powerful emotion that hung around her like a cloak.

And suddenly I knew what that emotion was. I’d felt it for a large part of my last year, after my fiancé disappeared, after my friend died, after I was followed, after I was a suspect in a murder investigation. The emotion was fear.

6

B ack in the courtroom, Maggie explained to Valerie that I would be helping on the case. Valerie looked confused, but nodded. Maggie then took the middle of the three chairs at our table so she could speak to both Valerie and me during jury questioning.

The state had the right to question potential jurors first. Tania Castle flipped her long brown hair over her shoulder as she looked at the jury questionnaires. She began calling on potential jurors, asking them whether they or their family members had been victims of a violent crime, whether they were members of law enforcement, whether they could be fair. When she was done, she consulted with Ellie, the other state’s attorney, and they booted two of the jurors, who were replaced by two others from the gallery.

Maggie held out our copies of the questionnaires. “You’re up,” she said.

“You’re letting me go first?”

She nodded, then leaned in and whispered instructions to me.

When she was done, I took the questionnaires from her hand. “Got it.”

I glanced at Valerie, whose face seemed to war between calm and dread. I gave her my best it will be fine expression.

Wishing desperately for that expression to be true, I strode toward the jury box, exuding what I hoped was a composed, authoritative air, even though my skin felt tingly, as if my nerves were scratching against it.

We wanted to present Valerie Solara, Maggie had said, as a mom, a Chicagoan and a friend. Valerie had lost her husband some years back and in order to be able to afford her daughter’s private school, they’d moved from their upscale Gold Coast neighborhood to the west side of the city, into a cheaper apartment. We wanted jurors who were devoted parents, or jurors who lived either north or west as Valerie had, or even widowers. Basically, we wanted people who seemed as much like our client as possible.

I looked at one potential juror and smiled. “Ms. Marshall. You mentioned on earlier questioning that your husband is a police officer, is that right?”

She nodded. She was a heavy woman with faded blond hair and splotched skin. She looked annoyed about having to be here, but her previous answers had shown she had some interest in being on the jury. She was also obviously in support of anything law enforcement; one of those people who believed the police could do no wrong.

I want her out, Maggie had said fiercely. In Illinois, an attorney can ask that a potential juror be dismissed for “cause”—meaning a situation where it was evident that a potential juror could not be impartial—as many times as they wanted. But what if it wasn’t evident that person was unfair? What if the lawyer just had a feeling? Then you had to use a “challenge.” But each side only got a certain number of challenges. My role was to try and get the juror to say something that would rise to the level of “cause.”

“Given your husband’s job,” I said, “do you believe you would be able to stay fair and impartial throughout the trial?”

“Of course,” she said, clearly annoyed. Exactly what I wanted.

“It could be days, even weeks, until Valerie Solara will be able to present her own evidence. Will you be able to wait until you hear all the evidence before you decide whether the state has proven their case beyond a reasonable doubt?”

“Yeah.” She crossed her arms and glared. She struck me as someone who wanted to be on the jury for the sake of being able to say so to her friends.

“Do you have children, Ms. Marshall?”

She shook her head.

“You’ll have to answer out loud for the court reporter, ma’am.”

“No,” she said loudly.

“Have you ever seen your husband testify in any cases?”

Now her face lightened. “Yes.”

“And have you ever encountered a situation where your husband testified in a case where the defendant was not guilty of the crime of which they were accused?”

“Oh, no,” she said immediately. “He wouldn’t.”

“Why is that?”

“Because he’s a policeman.”

“And police officers know who is guilty.”

“Right.”

“Is there a situation you could imagine where a police officer might testify and that person might end up being innocent?”

“No.”

I had her. I didn’t want to look triumphant in front of the whole jury, so I asked a few more questions, all benign, before I turned to Judge Bates. “Your Honor, I’d request that Ms. Marshall be excused from the jury for cause.”

He nodded. “So granted.”

Judge Bates looked at the jury. “Ms. Marshall, we thank you for being here today. You may leave.” He nodded at the sheriff to show her the way out. “Continue, Ms. McNeil.”

I picked out a thirtyish guy with hair flattened to his head in a way that was technically stylish but not on him, and who had been staring at my legs since I’d been in front of him. “Mr. Heaton.”

He raised his eyebrows in a suggestive kind of way.

I asked a couple of questions, enough to see that this guy would say yes to whatever I wanted. I thanked him and wrote W on the questionnaire, my shorthand for I-want-this-one-on-my-jury.

I turned to the woman next to him and questioned her, then another.

During the process of voie dire, you needed to not only pick out the jurors you wanted dismissed, but also win over the jurors you wanted to keep. You had to chat and crack a couple of jokes and respond to the judge and read one juror’s face while you read another’s body language out of the corner of your eye and keep your ears open for a C’mere a sec from your cocounsel—and you had to do this all at the same time and make it look smooth. I loved voie dire.

By the time I was done with the panel of jurors, I felt great. I walked toward the table and saw Maggie give me a pleased nod.

I glanced at Ellie Whelan, who regarded me for a second before she returned her gaze to the questionnaires in front of her. If I was correct, her eyes had held grudging respect.

I sat next to Maggie. “I want to do it again.”

7

M aggie let me handle two more panels of jurors before she took over, but the judge kept the jury questioning surprisingly quick compared to civil court. Once the jury was sworn in, the judge gave them directions about reporting for duty the next day. Then they were dismissed.

Maggie, Valerie and I went into the order room where Martin Bristol had been that morning. We sat at the same table. Valerie looked more shaken than earlier. “It’s really happening,” she said.

Maggie nodded but didn’t appear worried. I was sure she’d heard such sentiments from other clients before.

Just then, Maggie’s phone buzzed. She grabbed it from her pocket and looked at it. “It’s my mom. She never calls when I’m on trial. It must be about my grandfather.”

Valerie’s eyes closed at the mention of Martin Bristol.

Maggie left the room and shot me a look over her shoulder. Take charge.

I turned to Valerie and put on my best lawyer face. “So Valerie, let’s talk a little bit and let me explain why I’m here.”

She nodded fast and looked into my eyes, clearly wanting to be reassured.

“As you apparently saw this morning, Marty is feeling ill. He’s never really shown his age, but he is in his seventies.”

Valerie gave a short shake of her head. “But he doesn’t seem old.”

“You’re right.”

“He came to me so certain we would win. He believed me, and I found myself trusting him, which is unlike me.” Her small, dark-skinned hands flew to her face again, and she looked as if she might cry. “He promised to win my case.”

I sensed she wanted to say something else, so I remained silent.

“And now…” She looked at me, then her eyes darted to the door, and I could almost hear her words. Now, I have you two.

I leaned forward, my hands on the table, wide apart. “Valerie, I’ll ask you to do something right now. Please don’t underestimate either Maggie or myself. Maggie is one of the best criminal defense lawyers in the city, and in large part that’s because she was trained by her grandfather. I’ve also done a lot of trial work. We are both much more experienced than we look. And—well, I was thinking about this during jury selection—frankly, I think it gives a good impression for two women to represent you on this particular case.”

“What do you mean?”

“You’re accused of killing your friend.” I sat there and let the words sink into the room, as much for Valerie as myself. I was sure that Maggie and Martin had engaged in numerous conversations with Valerie before, but now that I was one of her attorneys, we needed to have an honest discussion ourselves. “Anyone would want Martin Bristol on their case. But I have to tell you, it’s not bad that you now have two young women whom the jury may see as the friends we are, representing you when you are accused of killing your friend.”

She said nothing, a look of concentration settling into her face.

“Our presence tells the jury we believe you.” I didn’t mention that Maggie had told me many times that she didn’t always believe her clients; she didn’t need to.

Valerie took in a large breath, seeming to gather strength from somewhere inside her. Her eyes softened. “I’m glad you are here. I thank you for it. And yes, I understand what you are saying. By the way…” She paused. “I did not kill Amanda.”

I nodded. “Maggie told me you’ve said that.”

Her mouth pursed. “I want you to believe me.”

I nodded. I wanted that, too. “Look, I don’t try criminal cases often, but the fact that I’m not usually a criminal lawyer is a benefit to you because I bring other things to the table.” I thought about it. “Maybe when we’re outside the courthouse, you and I could talk about what happened. Maybe if I hear everything from you, I could see other avenues for this case.”

I would have to see if Maggie was all right with that. Maggie had always said she didn’t need to have that kind of discussion with the clients, and maybe there was a little bit of protecting herself from hearing too much. But now that I was back in the law, I didn’t want protection from it. I wanted to be hit with it.

“Okay.” Valerie’s eyes looked deeply into mine, and I thought I could read a message there. Thank you.

Suddenly, I remembered something that pleased me about being a being a lawyer. It wasn’t just the excitement of a trial. I liked helping someone who truly needed it. I liked finding solutions that a person wouldn’t be able to reach themselves.

“Do you have any restriction for your bail?” I asked Valerie.

“No. The state’s attorneys asked that I be required to stay at home and wear an ankle monitoring bracelet, but Martin put up a fight.”

We both smiled. Marty Bristol was fairly unstoppable once he put on the gloves.

“But essentially,” Valerie said, “I’ve just been going home every day. It’s been very hard. Amanda was my best friend, along with Bridget.” She saw me raise my eyebrows in question. “Bridget is—was, I guess—a friend of Amanda’s and mine.”

“The woman who is going to testify against you.”

Her face twisted as if seized by something. “Yes. So now I don’t have Amanda or Bridget. My daughter, Layla, has been living with me. She just started her sophomore year at DePaul University, but she’s moved back with me because of this…” She raised a hand and waved it around the room. She looked down and smoothed her dotted dress, crossing her lean legs demurely. “Sometimes I wonder if it will be the last time we ever get to spend any time alone together.”

The pain of her statement hit me. “I don’t want that to happen to you,” I said. “Let’s make some time to meet outside the courthouse. Either at night or this weekend.”

She met my eyes, nodded and gave me a small smile. In that, I could see a tiny sign of life—the life Valerie Solara used to have.

“Tell me,” I said, turning to Maggie when she returned and Valerie had left, “what do you want me to do tonight?” On a big trial like this, there was always so much to do—contact witnesses, draft motions, prepare direct exams and crosses, research issues that had arisen that day.

“Do whatever you had planned,” Maggie said, lifting her trial bag, a big, old-fashioned, leather affair handed down from her grandfather. “I’ll give you transcripts to read to get you up to speed. But you could do that this weekend. We’ve got openings tomorrow, and I’m ready to handle that.” She furrowed her brow. “My grandfather was going to cross the detectives next week. I’ll get his notes.”

“How did your mom say he’s doing?”

“Same.” She slid some grand jury transcripts across the table to me and snapped the trial bag closed, a frown on her face. “I may have you handle one of the detectives on Monday.”

“Really? Do you think I can? I’ve never crossed a detective before.”

“Yeah, well, I think this detective in particular might be the best place for you to start.”

“Why?”

A pause. “It’s Vaughn.”

It took a moment for the name to register, then my voice rang out. “Damon Vaughn?”

The bailiff walked into the room, apparently to retrieve something from the judge’s desk. He stopped at the sound of my indignant voice, lifting an eyebrow.

I turned back to Maggie and dropped my voice. “I can’t believe you didn’t tell me that the detective who made my life a living hell is testifying in your case.”

“Well, before today I was going to let Martin massacre him on the stand, then tell you all the gory details. I didn’t think you would be trying this case with me.”

I thought about Vaughn, a lean guy in his mid-forties. The first time I’d met him was at the office of my old firm after Sam disappeared. The next time was at the Belmont police station after my friend died and I realized that Vaughn suspected me of killing her. Usually, I hated no one. But I hated Vaughn.

“That mother trucker,” I muttered.

Maggie rolled her eyes. “You’re still on your not-swearing campaign?”

I nodded. I was trying to quit swearing. I didn’t like it when other people swore. The problem was it sounded so good when I did it. Still, I replaced goddamn it with God bless you and Jesus Christ with Jiminy Christmas and motherfucker with mother hen in a basket. Maggie was forever mocking me about it. “But I think this requires the real thing,” I said. “That mother fucker.”

“So you want a shot at crossing him?”

I thought about it, then smiled a cold smile. “Let me at him.”

8

W hen Maggie and I left the courthouse, the city was hot and humid, and the air crackled with a Thursday-night near-weekend buzz.

“I wish I had my Vespa here,” I said. I had driven a silver Vespa since law school. I found it cathartic and freeing.

Maggie nodded at a sad-looking parking garage across the street. “I’ll drive you home.”

I glanced up and down the street. “Can’t I get a cab?”

“Not in this hood.”

“Just drop me off somewhere I can get one.” Maggie lived on the south side, while I was Near North in Old Town. “You have too much to do tonight to be schlepping me around.”

As we crossed the street, Maggie said, “Don’t you think it’s time to get rid of the Vespa?”

My head snapped toward her. “Get rid of the Vespa?” My voice was incredulous.

She looked at me with sort of an amused air. “Yes. Honey, I think it’s time.”

“What do you mean, it’s time? Gas is expensive, and it’s an easy way to get around.”

She gave me a look that was more withering than amused now. “How did you get to court this morning?”

“The El.”

“Then how did you get to 26th and Cal?”

“Cab.”

“And now I’m driving you home.”

“You’re driving me to get a cab.”

We entered the parking garage and took a stairway—one that smelled like urine—to the second floor. “Whatever,” Maggie said. “My real point is you are too old for a scooter.”

“Too old?” The indignation in my voice was strong. I huffed. “And it’s not a scooter, it’s a Vespa.”

We found Maggie’s black Honda and got in it. It was blazing hot, and we both rolled down the windows.

“You’re thirty now,” Maggie said.

“So? You’re thirty, too, and you’re driving this crappy Honda.”

“But I have a reason. I don’t want to go into this crappy neighborhood with a nice car. What’s your excuse?”

“Why do I need an excuse?”

Maggie backed out and headed for the exit. “Well, there’s more than just you being thirty. There’s also the fact that you have been followed by thugs and investigators and such more than once over the past year.”

I fell silent as Maggie turned from the garage onto the street. When Sam disappeared last year, I had been tailed by the feds—and by other people, as well. We were back to Sam.

“So, what did he—” Maggie said before I cut her off.

“I don’t know anything more than I told you. Literally, he said he was engaged, but he wouldn’t set a date if I didn’t want him to.”

Maggie whistled then added, “Holy shit. Or as you would say, ‘Blessed poo.’”

“Oh, shut up.”

“So do you want Sam to cancel the engagement?” she asked.

Confusion seemed to swirl around me, seemed to make the heat thicker. “Doesn’t your air-conditioning work?” I fiddled with the knobs on Maggie’s dashboard. “I don’t want to talk about it. Not until I talk to him.”

“Why?”

Good question. I talked to Maggie about most everything. “Because I don’t want you to shoot it down. Because I don’t want you to be pragmatic or to remind me what happened before. Because I want to hear what he has to say.”

We were both quiet for a second.

“Fair enough,” Maggie said. “Getting back to the Vespa…”

I shook my head. “I’m just not willing to give up something I love so much like the Vespa.”

Maggie nodded. “Well, if you won’t get rid of it, maybe you can borrow Theo’s car sometimes. What does he drive?”

I paused. I blinked.

“You don’t know?” Maggie asked, laughing.

I felt myself blushing a little. I looked at her. “I don’t. I really don’t. When we go out, he gets a cab and picks me up, or we meet somewhere.”

“I can’t believe you don’t know what kind of car your boyfriend drives.”

I looked out the front window, mystified. I used to know everything about Sam. “I don’t even know if Theo owns a car. He has a plane. He must have a car, right?”

“Ah, the plane,” Maggie said with a wistful tone. Theo and his partner had a share in a corporate plane, and Maggie and I had been lucky enough to use it earlier that summer.

“You know what’s nuts?” I said. “I haven’t even seen his apartment.”

Maggie braked hard, making the car screech. “Are you kidding me? You’ve been dating him for five months.”

“I know.” I shrugged. “He always stays at my condo.”

Maggie shook her head and kept driving. We passed a bar where an old motorcycle hung from the sign out front.

“He never wants me to come over,” I continued, “because he says his place is awful, and he’s been there since he was nineteen. I think the word he used was hellhole, which didn’t make me want to see it very badly.”

Although he was only twenty-two now, Theo was mature in many ways, having run his own business for a while, but in other ways he was still in the throes of those postteen years where you could live in a hovel and have just as much fun as if it were a mansion.

Maggie started driving again. “Jesus, your life is fucked up.”

“I know.” I couldn’t even take it personally. “But in an interesting way, right?”

When she didn’t respond, I pulled out my phone and I texted Sam three words. Meet me tonight?

9

T he restaurant was called Fred’s. It sat atop the Barney’s department store like a little sun patio hidden amidst the city’s high-rises. The roof had a geometric shape cut into it so diners could gaze up at the sky-scraping towers blocks away, their lights twinkling against the blue-black sky arising from Lake Michigan behind them.

Fred’s was more formal than Sam usually liked. I wondered what this meant. He had decided the rendezvous point.

I watched Sam across the table from me as he searched the room for the waiter. It was as if he could hardly look at me. Was that because being together was overwhelming, emotionally speaking? Because he was nervous? What? I used to be able to read him so well. I understood him in ways he didn’t even see himself. Like the fact that he had been wounded by his family, even though his mother and siblings were all very nice people. When an abusive dad finally moves out, and you’re the oldest and only son, some male instinct kicks in and you become the dad. You take over. And that will wound. Nobody’s fault.

Finally, the waiter arrived, and Sam ordered a Blue Moon beer.

“Sorry, sir,” the waiter said congenially. They didn’t have any.

“A different Belgian white?” Sam requested.

The waiter apologized and helpfully offered other options, but Sam stalled, seeming a little off-kilter somehow. I jumped in and placed my order to give him time.

“I’ll have vodka and soda,” I said. “With two limes.”

Sam’s eyebrows hunched forward on his face. “When did you start drinking that?”

I thought about it. “A few months ago? My friend introduced me to it.”

Sam searched my eyes. “Your boyfriend.”

I nodded.

He laughed shortly, gruffly.

The waiter still stood at attention. “Sir…?” he asked Sam.

Sam looked up at him. “Patrón tequila. On the rocks.”

“When did you start drinking that?”

“Just now.” He smiled a sardonic grin. “You inspired me to change.”

A few moments of silence followed. They felt like a settling of sorts, a shifting into us with a recognition that us wasn’t the same. But somehow, it felt okay. It felt normal.

“I don’t want to screw things up with you and your boyfriend,” Sam said. I could tell by the way he pronounced boyfriend, in sort of a lighthearted, almost dismissive way, that he didn’t think much of my new relationship.

“Very little could disturb our relationship,” I said, giving a little more weight to Theo and me than might be accurate.

Sam looked at me, blinking a few times.

When I said nothing, he spoke. “I’m just gonna put it out there. Alyssa and I decided to move out of the city. And that was okay with me, because…” He drifted off. Then he slowly nodded. “It was okay because sometimes it’s hard to be here without you. Because Chicago is you. And me.”

He looked at me, and this time I didn’t hesitate to save him. I nodded back. I knew exactly what he meant. Sometimes Chicago without him was not exactly the city I knew before. It was a little more exciting. A little more dangerous. Less consoling than it used to be.

“So anyway,” Sam continued, “we decided to move. Then somehow we started looking for engagement rings. But we couldn’t figure out what we wanted. Everything she sort-of liked, I didn’t. Everything I kinda liked, she didn’t.”

I nodded at him to continue.

“I just kept thinking about our engagement ring,” he said, swiftly unloosening the bolts of my heart with the words. Our engagement ring.

“Remember?” he said.

“Yeah, of course. You saw it in that jeweler’s window.”

“I couldn’t find anything better. Not even close.” He stared at me with a heaviness in his eyes, which momentarily made me sad for him. For me. For us both.

But then I thought of something. “You found a ring eventually, right? Because you’re engaged.”

“Yeah. Sapphire cut.” Sam rattled off a few more specifics that made it clear that a hell of a lot more money was spent on Alyssa’s ring than mine. But the truth was, I couldn’t have cared less.

Sam spoke up. Just one raw sentence that filled me with warmth. “It doesn’t feel the same with her.”

We nodded in silence. Kept nodding. And nodding.

Finally, I spoke. “A minute ago, you said I inspired you.”

Sam nodded.

“Meaning?”

“I want to take a page out of your book. I want to be able to start all over like you did, with grace.”

The emotional warmth I’d felt at his statement—It doesn’t feel the same with her—turned into an angry heat. I could feel my face turning pink, then ruddy, then redder still. Instead of being embarrassed, I let it lift my anger up until I could really feel it. “You think I started over with grace? Do you think I could possibly handle you disappearing two months before our wedding gracefully? I know by taking off you did what you felt you had to. You were fulfilling the dying wishes of a man you thought of as a father. You made a promise. But don’t forget that you’d also made me a promise when we got engaged, and do not assume I handled it well. Do not assume that, Sam.”

I took a gulp of the cocktail, the taste reminding me vaguely of kissing Theo after he’d been out with friends. I wanted that right now. I did not want to be assumed— assumedly fine, assumedly good-natured, assumedly graceful, assumedly a roll-with-the-punches kind of girl. I wanted to be consumed. And so I stood from the table, tossed back another gulp and I left.

10

S am walked up the flight of steps to his apartment. His legs felt heavy, the way they did when he’d been playing a lot of rugby. Izzy’s anger and her abrupt exit had shocked him. And yet it had made him love her more, respect her more.

When he reached his apartment and opened the door, Alyssa was there. He knew she would be, and yet he felt surprised. He always did when he saw her, as if he couldn’t force himself to remember on a regular basis that they were together.

He kissed the top of her blonde head. Felt a wave of guilt. But it wasn’t just Izzy that was causing the guilt. There was more. More that he hadn’t told either of them. Hadn’t told anyone.

The decision he had to make was technically easy. It could be communicated quickly, by phone or email. But the ramifications were bigger. Much, much bigger. Life-changing bigger. He couldn’t believe he was considering it. Would never have believed this of himself.

Which scared him. And thrilled him. He hated himself a little. But he couldn’t deny the thrill.

11

W hen I got to my condo—the third floor of an old three flat in Old Town—I stomped up the stairs and slammed the door. Silence answered. A minute later, when Theo buzzed and I hit the intercom, I heard him make a growling sound, telling me he was in the same mood as I was. Or at least the same ballpark. I hit the buzzer, felt lighter already.

I heard his heavy footfalls on the stairs. With each one—thump, thump, thump—my stomach clenched and unclenched in anticipation. And then there he was, opening the door, standing there for a second, his six-foot-two body taking up most of the frame. He grinned, looking at me, and still he just stood there. He wore a powder-blue T-shirt that had some kind of white lettering writhing across it. The shirt had been washed so many times that it looked incredibly soft. It also couldn’t hide his body underneath—the chest, the rippling stomach muscles. He took a step toward me and I flushed, every cell of my body alive and dancing with a desire that ramped up every time I saw him.

My reaction to Theo was so intense each time I saw him that I had begun to wonder if I was… God, I could hardly think it. Well, here was the thing—I had been starting to wonder if I was falling in love with him. Because it seemed nothing else could explain the constant ratcheting up of longing and emotions.

Yet it was hard to judge whether Theo was in the same place. And now there was something else. Now there was Sam.

Looking up at Theo, imagining lifting up that blue T-shirt, I reminded myself that whether Theo and I had perfect timing or not, it didn’t matter. Because here he was. Now. And where was Sam? With his fiancée. I felt rage again. My face flushed as an ever-so-slight tremor ran through my body. Was the tremor caused by the thought of Sam with Alyssa or the sight of Theo? No idea.

“Girl,” Theo said simply, what he always said. “What time do we have to be at your mom’s?”

His large body moved toward me, his chin-length hair, shiny and brown, swinging with the movement.

I banished Sam from my thoughts. I grabbed Theo’s T-shirt and used it to pull him around, shoving him into a seated position on the couch. I climbed on top of him, my legs on either side of his. “We’ve got time.”

12

T he first time he had gone to see the killing, the first time he had walked in that house, there was no emotion. That was what he noticed. The people there nodded at him. As if it were simple.

Everyone knew who he was. They seemed to expect him to know where to go, too. When he stood and looked around, feeling helpless—an unfamiliar emotion—someone pointed. He walked the hallway, trying not to think, trying not to blame himself. Other people were as responsible for the imminent destruction of this human being. The killing didn’t rest on his shoulders.

But he dropped the rationalizations quickly. He had been telling himself these things for years, especially about this killing, planned meticulously. And still he had done nothing to change it.

He kept walking. In his mind, his feet sounded like drums on the hard floor—bang, bang, bang—heralding something momentous, something terrible.

He had wanted people killed before this, had told others to kill. But he had never been there for the act.

Now, back in the present, that house a mere memory, he shook his head, tried to shake away the memories. It did no good for him to remember, no good at all. He told himself this all the time, and yet he kept slipping into these thoughts of the past. They sucked him in whole, so that he was entirely removed from today.

He sat up straighter in his chair now and shook his head again. In the back of his brain he heard a low bang, bang, bang—the drums still in the distance.

“Go away,” he said softly.

He had been trying to make retributions. But it hadn’t made a difference. He kept hearing the sounds, kept trying to wrench himself from that memory. But there was one thing in particular that wouldn’t leave him—the words the man had said in the minutes before he died. The feel of those words hitting his ear as he bent over him.

He sat even straighter now. Once again, he shook his head, trying to jar loose the recollection, wondering if the man had known his utterances would stick with him all these years. Was that what he intended? Or were they just more lies falling from the lips of someone who had already caused so much pain?

He tried to believe the latter. He had gone about his business after that day, although he became curious as to whether people saw it in him, whether they saw what he had done. All those years, he walked the streets of Chicago, a city as human as those living inside its borders, and he had wondered.

13

W hen my mother opened her front door, I saw again the change in her.

To say our family had gone through a lot in the past year was an understatement. My mom’s first husband—my father, long-presumed dead—had returned to this world and to our city. I had expected this to flatten my mother, as it surely would have in the past. But instead, she was stronger, more self-assured, her eyes more vivid than I had seen since I was eight years old.

But as I stood on her stoop with Theo, I was struck by a void—an empty space of words. I didn’t know what to say to her these days. This woman, so alive, didn’t seem to be the mom I had always known. So I stepped up and hugged her, wordless. Then I waved a hand behind me and introduced Theo, reminding her she’d met him briefly a few months ago, and she led us through the big front door and into the cool of her home.

The living room was a large space with ivory couches, ivory walls and gentle golden lighting. Soft Oriental rugs guarded over wide-planked, honey-colored wood floors, glossed to a high sheen. By this time of the night, my mother and anyone with her would usually be at the back of the house. The living room faced east and when it got dark in the afternoons, it increased my mother’s “melancholy,” as I usually called it in my head. But today, the room’s lighting blazed brighter. Charlie, my younger brother by a few years, and Spence, my mother’s husband, sat at a grouping of couches and chairs around a fireplace tiled in white marble. Inside the fireplace, my mother had placed a flickering candelabra.

I blinked a few times, unused to the sight. I glanced at Charlie, with his brown curly hair that had tinges of red. He gave me a shrug, as if to say, Don’t ask me.

Spence was a pleasant-looking man with brown hair now streaked with white. It fell longer on the sides to compensate for the balding top. He had on a blue button-down shirt rolled up at the sleeves and sharply pressed khakis.

“Hello, darling girl,” he said, standing and giving me a firm embrace. He pulled back and looked at me with his powder-blue eyes, his most striking feature. He appraised my face, and then moved to Theo. “Spencer Calloway,” he said, shaking Theo’s hand. “What can I find you to drink, son?”

Theo glanced at the coffee table where there was a plethora of food—artisanal cheeses surrounded by grapes and water crackers, prosciutto and paper-thin slices of melon, little croquettes that I knew likely held chicken and sun-dried tomatoes. Next to the food was my mom’s glass of white wine, my brother’s glass of red wine and a cocktail glass with clear liquid and a large chunk of lime in it.

“What are you having?” Theo asked Spence.

“Helmsley gin with a splash of tonic.”

“I’ll join you in that.”

I smiled, pleased. The truth was, I’d never known Theo to drink gin, but I loved that he was making an effort with my family. I squeezed his hand. When I had dated Sam he’d never joined Spence in a cocktail, and this fact, although meaningless, made me beam at Theo more.

“Good man!” Spence pounded Theo on the back and went toward the kitchen, calling over his shoulder, “Isabel, I’ll get you a glass of wine.”

Theo looked at my brother, who had stepped up to us. “Good to see you,” Theo said.

“Yeah, hey,” Charlie said pleasantly. They shook hands and started chatting about Poi Dog Pondering, a local band we’d seen a few months ago when Charlie and Theo first met. Charlie saw live music frequently, and he started rattling off other band names, then Theo told him about a bunch of British bands he followed.

Soon, Spence was back with our drinks, and we were all seated around the fireplace without even one second of that awkward, So, Theo, tell us what you do for a living kind of conversation. Instead, it flowed from one thing to another, from Theo’s company to Charlie’s job as a radio producer—after years of living happily off a worker’s comp settlement—to the trial with Maggie. At some point, my mom asked Theo where he was from.

“We moved around a lot for my dad’s work,” he answered. “California, Oklahoma, New York. Then we moved to Chicago when I was in high school.”

“Brothers and sister?” my mom asked.

“Just me.”

“And if I could ask, Theo, how old are you?”

I shot my mom a glance. She already knew the answer to that question.

“Twenty-two,” Theo said unapologetically.

I’d wondered if my mother would think Theo too young for my thirty years. Sam had been a perfect age, she’d told me once while we were engaged. But now she only said, “So young to own a business.”

“Yeah, I went to Stanford for a year,” Theo said. “I met my partner, Eric, who was a senior, and we started working on this software. By the end of that year, we were selling it. My dad helped us form the company, and we’ve been growing strong ever since.”

“Where exactly is your office, son?” Spence asked, loving anything that had to do with commercial real estate. That drew Theo and Spence into a new conversation.

We listened for a while, then my mother stood and gestured at me to follow her to the kitchen.

When we were there, she pulled me toward a counter and put her hand on my shoulder. Her blue eyes, more fair than Spence’s, were clear and striking. “I like him,” she said.

“You do? I’m glad.”

She nodded. “For many reasons. And my God, he is gorgeous.”

My mother rarely, if ever, commented on men’s looks, but I wasn’t surprised because nearly everyone mentioned Theo’s. When I’d introduced Theo to my former assistant, Q, short for Quentin, he’d commented—crudely, yes, but accurately—that every person in the room, male or female, gay or straight, young or old, wanted to fuck him. Everyone lit up for Theo, got a little red in the face, a little flustered. And the adoration only grew when people realized that he didn’t notice those reactions. Theo knew he was good-looking, sure, but he really didn’t know how good-looking. Or maybe he just didn’t like to identify with his hotness. Theo was a working guy, someone who ran his own web-design software company, and I think he liked to be connected to that more than anything.

Now, in my mom’s kitchen, I sighed a bit. “Yes, Theo is gorgeous.”

“Has your father met him yet?”

“I don’t think they need to meet.”

My mother’s eyes narrowed a little. “He is your father. And he lives in Chicago now.”

“When did you start advocating for Dad?”

My mom looked pensive, but her thoughtfulness appeared to have some curiosity about it, as if she were looking inside herself and interested in what she found there. This was different from how she usually did things; usually she shut down, became depressed and we all tiptoed around her.

In the living room we heard Charlie guffaw and Theo saying, “Exactly, dude,” laughing with him. A good sound.

“Your father deserves your respect,” she said.

“Does he?”

She looked at me, her blue eyes slicing into mine. “Yes.” A slight bob of her head. “And you should make some attempt to give him that.”

I’d seen my dad occasionally, but it was always awkward. More than awkward. For most of my life, he wasn’t around. We had believed him dead, when in truth he’d been working undercover for years. When I’d first seen him again, it was shocking. I was hunted by a faction of the Italian mob that my father had worked most of his life to shut down. As far as I knew, those particular dangers were gone now. But then again I knew that only because my father had told me so. The truth was, I didn’t entirely trust my father. Mostly, we made small talk, as if we weren’t ready to go into the big things yet. Lately, I’d avoided him. I didn’t know where to place him in my life, in my emotions. Avoidance was unlike me, but it had seemed the only workable option as of late.

“I’ll ask again,” I said to my mom, “when did you start being his advocate?”

The air was prickly as we stared at each other. We were in a minor spar, new territory.

A rueful smile came to my mother’s face, accompanied by—what was it?—a look of contentment, it seemed. It was that contentment, more than her smile or our spat that shook me somewhat. So unlike her, I thought.

“Do you know what it’s like to lose your sense of intuition?” my mom asked. Without waiting for my answer, she shook her head. “No, you have always been so good at following your gut instincts.”

“That’s not true. Last year, when Sam disappeared, I had no idea if my gut instincts were right or wrong. I was confused all the time.” I let myself feel the grief of that situation again, the whallop of confusion that had hit me over and over.

“But ultimately you followed your intuition,” my mom said. “Your intuition told you Sam was a good man and he had a reason for doing what he did. And you were right.”

“I still lost him.” But now he might be back.…

“I know how hard it’s been.” She gave me a sad face. “Really, Isabel, I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have brought this up. This isn’t the time for that conversation.”

In the other room, Charlie said something about preseason football, followed by the sound of a TV being turned on. My mother shook her head a little. Spence had insisted that they put a TV in the living room. It was hidden behind a painting that would slide away, but my mother still firmly believed TVs had no place in a formal living room. Spence had won.

“What conversation are you talking about?” I asked.

An exhale. “Well, I was just going to say that what I’ve learned lately, or maybe what I’ve decided—” she paused, seemed to be regrouping her thoughts “—is that someone can have a gut instinct and struggle with it, just as you did when Sam disappeared. That wasn’t easy, but you were smart enough to think of all the options, to play them out, and ultimately you stuck with your intuition.”

I thought about it. “Okay.” I searched for my intuition about Sam now and found my head empty.

“When your father died so many years ago, I lost that ability. I knew he was alive. I knew it in my soul. But every thing told me I was wrong. And so I had to shut down that instinct. Because he was dead. Because I buried him. Or so I thought.”

Her blue eyes shone bright against the white backdrop of her skin, more animated than I’d seen in years. Maybe ever.

“Over the years I would see him occasionally,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“Here and there, in a crowded street or a busy restaurant, I’d see him like a ghost. And I convinced myself that that’s what it was—a ghost. I really came to believe in those things—spirits and such—because there was no other explanation.” She gave a brittle laugh. “And because I kept doing that—closing down my instinct—I ended up shutting it down in other areas of my life, too.”

I said nothing. I was mesmerized by getting behind the curtain of my mother’s mind.

“I drifted wherever life took me,” she said, “rarely making decisions, rarely thinking I had any control or any part in this.” She waved her hand around her kitchen.