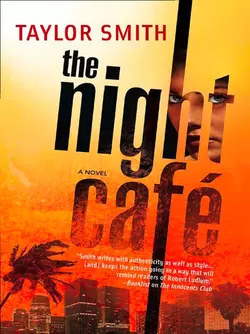

The Night Café

Taylor Smith

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Between jobs and feeling financially strapped, gun-for-hire Hannah Nicks takes on an assignment that promises easy money and an all-expenses-paid vacation on the Mexican Riviera. Hired by her sister′s friend, a gallery owner, Hannah sets out to transport a minor artist′s painting to its buyer in Puerto Vallarta. But when Hannah arrives at the delivery point, she finds the tail end of a massacre and is nearly killed herself. She hides the painting, fearing it is not a meal ticket but a death warrant, and flees back to the States. But it only gets worse for her in L.A.The gallery owner has been killed, and Hannah is named as the murder suspect. In order to prove her innocence, she must hunt down the person who framed her…and uncover the secret of a deadly work of art.