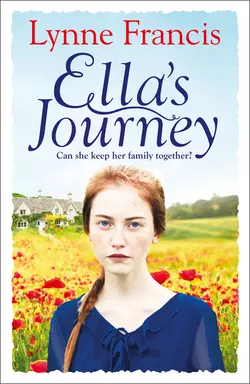

Ella’s Journey: The perfect wartime romance to fall in love with this summer

Lynne Francis

A family in need. A country on the brink of war.Ella is trying to put the past behind her… but the past won’t always stay hidden.The truth is, Ella is hiding from a scandal. A scandal that drove her family out of their beloved Lane End Cottage in the tiny Yorkshire village they had lived in all their lives. A scandal that her sister Alice was blamed for.But Alice is no longer here. So it’s up to Ella to pick up the pieces and do the best she can for the family she loves so dearly.Ella’s luck finally changes when she gains work at Grange House, a gentleman’s residence on the outskirts of York. But can she keep her position there? Or will she follow in her elder sister’s footsteps?A gripping new saga series that fans of Dilly Court and Valerie Wood will adore.

ELLA’S JOURNEY

LYNNE FRANCIS

Avon an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain in ebook format by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Lynne Francis 2017

Cover design © Alison Groom 2017

Cover image © Shutterstock

Lynne Francis asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008244279

Version: 2018-05-10

Dedicated to the memory of Freda Pegden 1924–2017 and Lucy Westmore 1958–2017

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub0ade720-57b6-5a1b-bad2-da52c7125c1b)

Title Page (#u3a27ca5a-0378-5681-845b-c6a95f44e396)

Copyright (#u13b81e71-a65c-5a76-bc9c-a4b19eb5bb6c)

Dedication (#uff01190f-e469-51df-9722-3a04abca87e0)

Part One: 1896–1902 (#uf7b3f602-0932-5c18-af8d-f94977d71735)

Chapter One (#ua394f10f-4af1-5523-ade1-90e133e84ea7)

Chapter Two (#u61181c71-61e9-5730-9fa4-50e79d2ccf54)

Chapter Three (#u014d77a9-915f-507c-9f4f-0e8b8f3aefbb)

Chapter Four (#u16d8f671-4e71-59f3-8dc4-d3aac498a4e6)

Chapter Five (#u8d986271-96c2-58b5-8b77-ca84317755b1)

Chapter Six (#u51de035c-2d08-5c28-bcb6-45faa7ddaadb)

Chapter Seven (#udca465c6-1e79-5e76-98b6-ae6921fe645a)

Chapter Eight (#ub1d71df0-5fe4-5c4e-9cfd-ad9c8e70e831)

Chapter Nine (#u6b07c9e7-a7a3-5043-bb57-4e7c5e890661)

Chapter Ten (#u8b1827ef-7513-5be1-9435-2b97c87f250c)

Chapter Eleven (#ua880c9e7-a09c-5431-8016-941dab95b89f)

Chapter Twelve (#u744dd184-c52e-56e7-8b0e-5a2e2300552c)

Chapter Thirteen (#uf6ceaed0-f6e5-5d49-8cfb-3521c6c1013f)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: 1903–1904 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: 1904–1913 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: 1914–1918 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Part V: 1918–23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#u9504ddb0-2f5d-5dcf-bb24-451e33ab1045)

CHAPTER ONE (#u9504ddb0-2f5d-5dcf-bb24-451e33ab1045)

‘Ella?’

She thought she heard someone calling her name, but it was hesitant, and the bustle and hubbub of the crowd whipped the words away. She paused and turned but, unable to spot anyone she knew, she continued on her way, shopping list in hand. Parliament Street market was busy so close to Christmas, although at least the crush provided a bit of warmth on such a raw, bitter day. Ella’s brown wool coat, on permanent loan from Mrs Sugden, the housekeeper, fitted well enough but it was thin and barely held the cold at bay. She was glad of her red knitted scarf – a bright flash of colour – and another loan, this time from Doris, from one of the maids. When Ella Bancroft had first arrived at Grange House, the two women had been puzzled by what they perceived as her lack of appropriate clothing.

‘A shawl will never do!’ Mrs Sugden had exclaimed the previous November when Ella, wrapped in the shawls that had seen her through the Yorkshire winters back in Northwaite, was set to leave the house with her shopping list and basket. ‘You’ll be nithered. And you’re in the town now. You need to wear something that’s a credit to the household. You’d best borrow this.’

She’d pulled the brown coat from the cupboard in the passageway. ‘I won’t miss it. I’ve another I prefer.’

Ella had slipped it on: it fitted her quite well. She thought it was probably some time since Mrs Sugden had worn it as it was putting it kindly to say that the housekeeper was a good deal broader than Ella, who was slender and taller than average. She’d judged it best not to comment, however, and instead expressed her gratitude, although privately she felt that the thin wool wouldn’t do the same job of keeping out the cold as her thick woollen shawls. And so it proved but, nevertheless, she felt almost elegant when she ventured out in the coat, which was a feeling quite new to her. Stevens, the butler, had said admiringly, ‘That red scarf of Doris’s puts the roses in your cheeks,’ making Ella blush and thus further increasing her rosiness.

She wished she had a pair of gloves. The wind was biting and her numb fingers struggled to grasp the coins as she made her purchases. Tucking the last paper bag into her basket, she smiled at the stallholder who was stamping his feet and blowing on his fingers in an effort to keep the chill at bay. With her errands completed, it wouldn’t be long until she was out of the cold and back in the kitchen at Grange House. Groceries arrived there in a regular weekly delivery, one of the many things that Ella had marvelled at in the York household. The grocery boys carried great boxes of meat and vegetables into the scullery and, if more supplies were needed during the week, one of the delivery boys would be sent round on a bicycle, with his front basket loaded up and his apron flapping as he pedalled. But sometimes Mrs Sugden took it into her head that they needed a nice bit of samphire to go with the fish for that night’s dinner, and old Mr Grimshaw’s stall in the market was bound to have some, or she’d heard that there were some particularly fine quail’s eggs to be had that day. Ella was both entranced and unnerved by her errands, puzzled that a bright-green weed would be deemed suitable to serve at the table, or that such a creature as a quail existed.

‘Ella!’ This time the call was louder, more forceful, stopping her in her tracks. She turned again, scanning the crowd. As her eyes skimmed over the good citizens of York, intent on last-minute Christmas purchases, they were arrested by an almost-familiar figure.

‘Albert?’ she said uncertainly. ‘Albert Spencer?’ He stood before her: out of breath, wiry, dark-haired and little changed in appearance from the young man she’d last seen several years before.

‘You know your way around!’ he exclaimed. ‘I’ve had a hard job keeping up with you in this crowd. Is it always like this?’

Ella glanced about her and smiled. ‘Yes. Always busy with those in search of a bargain or two, particularly so at Christmas. You’re not familiar with the market then?’ She looked enquiringly at Albert, trying to get over her astonishment at seeing him after so long.

‘No, no, I was here by chance.’ Albert sounded hurried. ‘But I’m glad I was. I wasn’t sure it was you at first, but then when I followed you I knew I was right. You move just like Alice!’

Hearing her sister’s name gave Ella a jolt and she glanced quickly at Albert.

Oblivious to the effect he’d had on her, he carried on. ‘What are you doing here? It’s so long since I’ve seen anyone from home! I’m aching for news. It’s too cold to stand around here though. Is there somewhere we can talk?’

Ella hesitated. Mrs Sugden would scold her if she was late back, but she wanted to hear Albert’s news, even if she wasn’t keen to share hers with him. He had a confident air, which was that of a grown man now, far removed from the mill boy she had walked to work with seven or more years ago. The cut of his clothes marked him out as prosperous; not like her employer Mr Ward, of course, but not dissimilar to some of the tradesmen who came to the house to discuss plans for the houses that her employer was building on the edge of the city. Ella was becoming practised at pinpointing who belonged to which level of society, even though such things had been a complete mystery to her when she first arrived in York. Back in Northwaite where she had grown up there had been those that worked at the mill, those that owned the mill, and the overlookers in between. A few other figures, such as the parson and the doctor, occupied a level above the overlooker and below the mill owner, Mr Weatherall, and his family, but there was little to consider beyond that.

Here in York there were landed gentry right up at the top of the ladder, those who didn’t seem to work on a daily basis but whose affairs regularly called them away from home, to Leeds or to London. Then there were those who had a standing and an education, such as doctors and clergy; after that came business people, tradespeople, shopkeepers and a whole layer of workers below who kept the wheels in motion.

The hierarchy ‘below stairs’ in the grand residences such as Grange House was a little world in itself, from the butler right down to the scullery maid. It had taken Ella a while to sort all this out for herself. She’d only managed it by careful observation and listening to the nuances of conversations: the way in which Mrs Sugden referred to those under her jurisdiction, and those above stairs. Although Ella worked as both a house parlourmaid and a lady’s maid these days, her role was relatively clearly defined compared to her previous role in Mr Ottershaw’s house back in Nortonstall, just two miles from where she had been born and brought up. Ella shuddered at the memory. As the only maid that he could afford, she had been expected to cover all the household duties of cooking and cleaning, as well as minding the children. The length and hardship of her days had almost made her nostalgic for her time working at the mill.

Albert had noticed her shudder. ‘You’re cold,’ he said and, taking her arm, he guided her through the grand, gilded doors of the tearoom that stood a little way from the edge of the market. Ella hesitated, trying to pull back, but it was too late; they were inside in the warmth and being ushered to a table. She’d passed this place many times whilst on her errands and had gazed through the huge plate-glass windows, wondering what it must feel like to sit at one of the round tables draped with a starched white cloth, having time to sit and chat over coffee served in monogrammed china cups.

Her cheeks flamed, partly from the sudden warmth but more out of embarrassment. Her coat, which she had thought so smart, felt distinctly dowdy and unfashionable in here. She could see some of the ladies at adjacent tables eyeing her up and down, noting her attire, her basket, her lack of a proper hat and gloves, the way her unruly reddish-blonde hair was escaping from the pins holding it in place. They commented to each other, turning away then glancing back, laughing behind their hands.

Albert was oblivious to this. He ordered coffee for both of them before turning his attention to Ella. ‘You’ve barely said a word,’ he said.

Ella tried to overcome her discomfort, and her worry about being scolded by Mrs Sugden over her tardiness. ‘I’m sorry. I’m just a bit overwhelmed. I’ve never been in here before.’

She chanced a look around, trying to imprint her surroundings on her memory. High ceilings, the grey light of winter filtering through the stained glass which edged the windows, the inside lit by gas lamps and filled with the buzz of chatter and laughter, the clink of china and wonderful aromas of coffee, sugar and chocolate. Ella felt her stomach rumble. Breakfast had been a long while ago.

Albert must have read her mind. As the coffee pot was delivered to the table, he murmured something to the waiter, and a plate of tiny pastries swiftly followed. Ella relaxed a little and unwound the scarf from around her neck, trying to sip her coffee and eat her pastry as though she was used to it, although even a cursory glance at her reddened, worn hands would have suggested otherwise.

‘So,’ Albert said, giving her a probing look. ‘How long have you been in York? Do you have news from home?’

Ella started to fill him in on her last few years, her time at Mr Ottershaw’s in Nortonstall and the hardships of life there, her chance meeting with Mr Ward and her good fortune in being taken on at Mr Ward’s house in York. She managed to intersperse a few questions for Albert, and very soon realised that his apprenticeship and almost immediate employment as a qualified stonemason had kept him fully occupied here in York, and in other cathedral cities. It appeared that he had not returned to Northwaite in all that time. He had sent word home, and frequent amounts of money, but had heard little in return, neither his father nor his mother being ‘much of ones for writing’ as he said ruefully. Ella knew this to mean that they had never learnt how.

The furrow in Albert’s brow had deepened as Ella told her tale, and she feared his next question. Her coffee was drunk and she was very conscious of the passage of time. Mrs Sugden would not be impressed at the idea of a servant meeting up with an old friend and passing the time of day with him in a tearoom. Ella knew she was going to be in trouble.

‘I really must go. It was lovely to see you, Albert, but I will be late back.’ Ella wound her scarf around her neck as she spoke, and pushed her chair back. Perhaps she could make her escape while he settled the bill? She felt a pang of regret. It had been so lovely to see a familiar face from home, but what use could they be to each other now?

‘Wait,’ Albert rose at the same time as Ella and handed her basket to her. Ella tried to ignore the contemptuous stares of their neighbours. ‘Alice. You haven’t mentioned Alice. How is she?’

Ella took a deep breath. She had dreaded this very question. ‘She’s dead, Albert. I’m really sorry. It happened within three months of you leaving. Alice is dead.’

And with that she hurried to the door, almost pushing the doorman out of her way in her haste to be gone. As she passed the window, she glanced in quickly. Albert still stood by the table, as if rooted to the spot, leaning forward slightly and supported by his rigid arms, fingers splayed and tense on the cloth, all colour drained from his face.

CHAPTER TWO (#u9504ddb0-2f5d-5dcf-bb24-451e33ab1045)

By the time Ella had reached the Tadcaster Road, a good mile and a half from the tearoom, she was regretting the manner of her departure. It was cruel to Albert, who didn’t deserve it. Her own grief over her sister’s death seemed to veer between a cold, hard nugget locked away deep inside, to an overwhelming, boiling rage that made her want to run and run, screaming aloud at the injustice of it all. It was partly the latter sensation that had made her want to leave the tearoom so suddenly. Whatever would Albert think? She knew he had been sweet on Alice, but too shy to ever express this to her. Only a little older than him in years, Alice had seemed vastly older than him in wisdom and had always treated Albert more like a younger brother. Ella sensed some sort of unspoken bond between them, which she put down to them having been playmates from a very young age in Northwaite.

Northwaite. It hurt her to think of it even now, high up above Nortonstall on the Yorkshire hills, with views for miles on a clear day, exposed to vicious winds, snow, sleet and hail in the winter. As a child, Ella had believed that the skies went on for ever, something that had only struck her once she was here in a city, where the sky seemed limited by the buildings all around her. Even if she climbed to one of the highest points in the centre, Clifford’s Tower, her view was restricted to the silvery stones of the ancient city walls and the trees that shaded the river path. York, sprawling along the river, was set deep within a vale and at times Ella’s spirit longed for the soaring open spaces of her childhood home.

The bustle of the city streets, the rattle of the hansom cabs and the calls of the street urchins, the constant passage of people going about their business from dawn until dusk and on into the night, had been both a shock and a source of delight to Ella when she first arrived here. Now she barely noticed it, except when on a hurried errand and she found her way impeded by the sheer number of people out and about. What would her mother make of it all? Ella smiled to herself.

She could hear Sarah’s voice as clearly as if she was standing beside her. ‘What is so important that they have to be going at such speed?’

Ella’s mother’s journeys through Northwaite had always involved stopping to talk to everyone she met and enquiring after their family’s welfare (even if she had only seen them the day before). It could take her the best part of an hour to travel a few hundred yards. More than anything, her mother would struggle to comprehend that the majority of people passing along these streets were strangers to each other, their houses spread over a wide area of the city or its surrounds, their acquaintance more likely to be a result of their business or family connections rather than neighbourliness.

She would be astonished by the traffic on the streets, too. Ella had seen the occasional motorcar as it passed through Nortonstall; indeed, that was how she had first met Mr Ward, her current employer. But Sarah would probably have fainted at the sight of a double-decker horse-drawn bus. Ella began to wish that she had thought to ride one of these from the centre of York; although she had walked fast it was so cold that her face felt as though it had been chipped from a block of marble.

The low wall around Grange House – topped with imposing iron railings, spike-pointed and painted black – came into view. Ella paused to catch her breath, puffed out after keeping up a fast pace on her route out of York. More than once she’d had reason to wish that the family still lived in their previous residence in Micklegate, so convenient for the centre of the city, rather than out here on the edge of the city. They’d moved before Ella had arrived in the household just over a year previously, joining the exodus of the newly wealthy who were building themselves the grand houses surrounded with fine gardens that they could never have within the confines of the city walls.

It occurred to Ella that she had no notion of how to contact Albert again, if for no other reason than at least to apologise for her abrupt departure. Seeing someone from her past like that had thrown her completely off balance and it reminded her that the security she was beginning to feel in her new life was easily challenged. Quite apart from that, Albert had been such a dear friend of Alice and indeed of the whole family. Ella had an inkling that his own home life was less than happy and that the Bancroft household, while often chaotic, was very appealing to him. She had a sudden flashback to his visit to the house not long after her niece Elisabeth, known to the family as Beth, had been born, his mixture of shyness and happiness at being included in their happy family gathering. He wasn’t to know that the celebration, inspired by his presence, wasn’t a regular occurrence, but it had lifted the spirits of the family, mired in bleakness by the chill of the winter and the desperation of their situation. In fact Sarah Bancroft, alone after the death of her husband, with five of her own children to bring up and now a grandchild too, often wondered how food was to be put on the table that night.

Albert had been deeply uncomfortable around Beth that day, being an only child and having no prior experience of babies, but Ella remembered that they had all taken a lot of joy from the evening. She felt sure, though, that his visit had more to do with a wish to see Alice, who was no longer his daily companion at the mill.

He’d changed such a lot in the intervening years, and it gave Ella pain to think of how Alice, too, would have matured if she had only survived her wrongful incarceration in jail. Although Albert had mentioned his work as a stonemason at York Minster, nothing had been said about where he was living now. She had no idea how to go about finding him.

Taking a deep breath, Ella skirted the wall to the servants’ gate set into the side, and pushed it open, only too aware of how late she was. As she hurried towards the heavy door that led into the servants’ domain she remembered how fearful she had been when she passed this way last year, clutching her worldly possessions in a worn cloth bag. Mrs Sugden, or Mrs S as Ella soon discovered she was known to all the servants, had been kind, almost motherly to her that day, accurately assessing her fright and state of mind. Ella, having seen the sterner side of Mrs S’s nature many times since then, feared her reception wouldn’t be so welcoming today. She must have spent an hour or so in Albert’s company: she really was very late.

And so it proved. Mrs S bore down the corridor towards her as Ella attempted to hang up her coat and slip unnoticed into the kitchen with her purchases.

‘Wherever have you been?’ Mrs S demanded, her gaze direct and angry. Scarcely waiting for a response, she continued, ‘You’d better smarten yourself up at once. Mr Ward wants a word with you. He’s in the library. With Mrs Ward.’

Ella was vaguely aware of pale, worried faces peeping around the kitchen door behind Mrs S’s back. There was a hush over the whole area, the usual noise and bustle subdued. Ella sensed that the other servants were frightened, but of what she couldn’t begin to imagine. She hastened to wash her hands and to tuck stray strands of her reddish-blonde hair under her cap, hurriedly pinned in place so that she looked like a proper parlourmaid as she pushed through the green baize door into the house itself, and into the chill of the hallway.

Her mind was in a whirl. Could she really be in this much trouble just for being late? Or had something happened at home? Surely, if this had been the case, Mrs S would have been the one to break the news? This had a much more serious air altogether. For the second time in less than a quarter of an hour, Ella took a deep breath and steeled herself. Then she knocked on the heavy door of the oak-panelled library, pushing it open when the murmur of voices within stilled and Mr Ward called ‘Enter’.

CHAPTER THREE (#u9504ddb0-2f5d-5dcf-bb24-451e33ab1045)

Mrs S was summoned to conduct Ella from the library to her room. Very little was said as they crossed the threshold through the green baize door and climbed the steep and narrow back stairs to the servants’ quarters, tucked away in the attics. Ella looked out of the windows as they crossed the half-landing on each floor to mount the next flight. The sky outside was darkening and, over the fields beyond the garden wall, lights were beginning to twinkle through a greying dusk. The rush to get everything ready for Christmas had resumed down below, but up here it was cold and quiet.

Mrs S broke the silence. ‘I’ve moved Doris out of the room. She can share with Rosa until it is decided what’s to be done.’

She pushed open the door to the room and Ella passed through, automatically heading for the window to gaze out.

‘You’d be as well to put your things together. I don’t think the master will be wanting to keep you after this.’ Mrs S sighed and closed the door. Ella, staring unseeing out of the window, heard the key click in the lock.

Her cheeks were hot with shame and indignation, her mind a jumble of words unsaid. The thought that floated to the top of this seething mass was the likelihood of the loss of her job. How would her mother manage without the money that Ella sent home to her? How could she begin to tell her what had happened?

Ella turned away from the window and sank onto the bed. Scenes from just a few minutes earlier began to play out in her head.

Mr Ward had been sitting at his desk, Mrs Ward silhouetted in the window, her back to the light so that Ella had found it difficult to read her expression. There was no mistaking Mr Ward’s mood, however. His brows were drawn together in a frown and his mouth pursed into a thin line.

‘Ella, we have reason to believe that you may have been involved in an act that has proved injurious to the health of one of our guests.’

Ella was puzzled, her mind racing to make sense of this turn of events. So it was nothing to do with her late return from town, or her family? This was something quite unexpected.

Mr Ward continued, ‘I see you do not deny it. You must have been aware of the potentially fatal consequences of your actions when you entered into this ridiculous pact with Grace. I would like you to go away and think very hard about your behaviour. I have already consulted Mrs Sugden about your character and, whilst she assures me that you have conducted yourself in an exemplary fashion whilst in our employment, I am not minded to be lenient in my view of this. You have run the risk of bringing my good name, and that of my family, into disrepute by your actions. You will go to your room, Ella, and think long and hard on this.’

He turned his attention back to papers on his desk, to signify the interview was at an end. Mrs Ward had not moved throughout Mr Ward’s speech but, as Ella turned to leave – stunned by what she had heard and unsure of how she might defend herself – she saw that Mrs Ward was gazing on her husband with an expression that was very hard to read.

On the silent walk to her room, Ella had struggled to piece the jigsaw together. Something had clearly happened that involved Grace, the youngest daughter of the household, and somehow Ella was taking the blame for it. With a sinking heart, she pictured the small bottle she had handed over to Grace earlier in the week. Stoppered by a cork and without benefit of a label, the pearly glass held a dark, mysterious liquid.

‘Shake it well,’ she’d whispered. ‘And mind, no more than two or three drops in his drink. Be sure to keep the bottle well hidden.’

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_19ac1593-e8b5-5be1-9600-efbbf6c650a0)

Over on the other side of town, Albert could barely remember how he had found his way home from the tearoom after Ella had delivered the terrible news. After she’d gone, he’d been vaguely aware of curious glances, of conversations briefly stilled, of whispering behind hands. Within a minute or two, though, the large room was filled with its previous level of chatter and he had paid quickly and left, the atmosphere deeply at odds with his shocked frame of mind.

Alice was dead. Ella had given him no further details of what had happened to her sister, of how or exactly when it had happened. He couldn’t comprehend it. Throughout his apprenticeship, spent living alone in York, he had been sustained by the thought of the woods and valleys that surrounded Northwaite, his true home, and of Alice going about her day-to-day routine there. At first, he had thought more often of Alice than of his family, reliving her companionship on walks to the mill in the morning, his visit to see her at home when her baby Beth was born, the warmth and welcome of her family in such contrast to his own. He’d longed daily to be back in Northwaite, but as time passed in York and the opportunity to return home hadn’t arisen, the longing had faded into something held at a distance, in the back of his mind. Alice and Beth, he realised now, had become frozen in time, exactly as he had left them, seven years ago. Seven years! Albert was startled to realise just how much time had passed. No wonder seeing Ella had given him such a shock; she must be almost the same age as Alice had been when he had left Northwaite.

Albert had arrived home without being conscious of how he had done so, his feet treading an automatic path while his thoughts were engaged elsewhere. He needed to find Ella again, to discover exactly what had happened to Alice, and he knew he would have no rest until he had. And if he couldn’t find her, then he would return to Northwaite as soon as possible and seek the truth there. It wouldn’t be the return he had imagined, the return he had subconsciously been putting off until the moment was right. He had wanted to go back as a success, to show his family what he had made of himself, but above all to impress Alice. For well over a year now, his skills had been sought after both in York and elsewhere as word had spread within the close community of stonemasons. So why hadn’t he gone back? Had he feared that the vision he had held in his mind for so long, a fantasy of the part he could play in Alice’s life, could never be realised?

Albert thought back over the events of seven years ago. He tried hard to put the shocking news that he had just heard in context to see how it impacted on everything he knew. His career as a stonemason was a direct result of the fire at the mill, which had employed the majority of the working-age population in his home village of Northwaite. Alice had once worked there, Ella worked there and he himself was a nightwatchman there. On that fateful night, he had tried to put out the fire but it was beyond him, and the mill owner’s son had died in the blaze, attempting to save books and papers from the office. Williams, the overlooker, who had been the only other person present during the fire, had appeared at Albert’s house the very next morning. He had news of a reward given by Mr Weatherall, the mill owner, in recognition of Albert’s heroic efforts to stop the spread of the fire. And, seeing that the mill would be closed for the foreseeable future, there was also the offer of an apprenticeship as a stonemason in York, to be taken up immediately.

Albert had been grateful to Williams and had never thought to question his role in all this and the haste with which he had been despatched. He was only too delighted to get the longed-for opportunity. Now that very same opportunity, which he had hoped would raise his standing in the world and make him a suitable prospect as a husband, was cast in quite a new light. Alice had died, seemingly very soon after he had left, but he didn’t yet know why. A piece of the jigsaw was missing; he needed to talk to Ella again.

Albert sat at the table, still muffled in his overcoat, and looked around, taking in the sparsely furnished room, his neatly made bed in one corner, the desk positioned by the window to make best use of the light, the one easy chair set by the unlit fire. He buried his head in his hands. What had he done?

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_980e47ce-8ee8-5be1-b3ee-c73cd887ea98)

While the family celebrated the festive season, Ella remained confined to her room. She’d spent the night tossing and turning in her narrow bed, dozing fitfully and waking to discover how little time had passed; how the window was still filled with darkness, the sky dotted with twinkling stars. As the stars faded, to be replaced by the grey light of dawn, she felt a sense of relief. Soon she would be able to hear the sounds of the household coming to life; of Doris and Rosa dragging themselves, yawning, down the stairs to start the day. Ella felt a terrible pang of guilt. They would have to take over her duties as well as their own, and all this at Christmastime with so much extra work needing to be done.

Today was Christmas Eve, when the tree would go up in the entrance hall. Last year, Ella had helped to decorate it, her first ever Christmas tree. She’d been entranced by the delicate glass baubles, each one wrapped in tissue paper and carefully boxed. She had never seen anything like it; the tree so tall that the butler, Mr Stevens, had needed to climb a stepladder to hang the decorations from the top branches. He had only managed to place the star on the top by going up to the landing and leaning precariously over, Rosa and Doris hanging on to his coat-tails and squealing while Mrs S stood at the base, alternately telling the maids to shush and gasping in fright herself. When the decorating was finished, and the candles placed in each holder all around the branches, the Wards’ youngest son John was called to see the candles lit for the first time.

Ella had felt sure that his saucer-eyed amazement had only been a reflection of her own expression. She could have stared at the tree for hours, drinking in each and every detail, how the flames of the candles sparkled and reflected in the glass baubles as they spun and shifted in the draughts of the hall.

John’s governess had gone home for the holidays and although Mr and Mrs Ward were there for the lighting ceremony, it was Ella that John sought out, reaching for her hand and gripping it hard, wordlessly. She had bent towards him.

‘It’s beautiful, John. Have you ever seen anything like it?’ She so wished that her niece Beth were here. Ella would have taken her around the tree, pointing out the sparkling colours of the spinning baubles, and the little toys and striped sugar canes hanging from the branches.

John found his voice. ‘Yes, I have. Last year.’

Ella smiled. ‘You can remember it?’

‘Of course I can.’ John was scornful. ‘I’m not a baby. I’m six.’ He paused. ‘It was in our other house and it wasn’t as tall as this one. I think this year’s tree is the best of all.’

Mr Stevens, handing out candied fruits, a Christmas treat for the family and staff, heard John’s words and bent to offer him a fruit jelly.

‘Well, Master John, it’s lucky we had enough decorations to cover such a tall tree. Now, you’ll have to let go of Ella. She has work to do and it’s time for your bed. Christmas Day is nearly here.’

Ella wasn’t sure whether it was she or John who had been the most reluctant to be parted from the spectacle, but the family were moving through to have their drinks and, with extra guests expected, her help would be needed in serving the Christmas Eve dinner. She had bent down to whisper to John, who was exhibiting a mulish expression, bottom lip stuck out and jaw set in preparation for a battle over bedtime.

‘John, Father Christmas can’t visit unless he knows you are asleep. So off you go to bed now and in the morning you can come downstairs to check. If you are lucky, and if you have been a good boy, perhaps he will have left some presents for you under the tree.’

That had been a year ago. She had been so looking forward to a repetition of the ceremony this year, to experiencing the same magical feel and all the wonderful scents of the house at Christmas. She remembered lingering in the hallway every time she had cause to pass through it, to drink in the scent of the pine needles. Instead, she was locked up here alone in the chill of her room, a world away from the lights, warmth and bustle of the household on Christmas Eve. She heard Doris and Rosa go down the stairs, and huddled back under the covers. There seemed little point in getting up, only to sit fully dressed in the cold, with nothing to do except strain her ears for sounds from below that might give her some sense of belonging to the celebrations.

She must have dozed again, waking with a guilty start to the sound of the key turning in the lock. It was Doris, bringing a tray with breakfast for her: tea, and a hunk of bread and butter. It was poorer fare than Ella could have expected had she been at the breakfast table with the other servants, but she was grateful for it all the same, even though the tea was stewed and all but cold after being carried up the chilly staircase.

‘You’re to stay up here until Christmas has passed,’ Doris said in solemn tones. ‘Whatever have you done, Ella? And all the extra work you’ve given us at this time of year, too. What can you have been thinking of?’

Her words sounded harsh but Ella could see that Doris was torn between scolding and concern. She knew only too well how much Ella needed her job.

‘Mr Ward will talk to you again on Boxing Day evening, after the guests have gone, Mrs S said to tell you. She’s too busy to come up here herself.’

Doris cast a quick glance around the room and sighed. ‘It’s little better than a cell, what with all the brightness down below for Christmastime. I must go, I have so many things to do, but I’ll try to be back.’ And with that she was gone, the key turned firmly in the lock.

Sitting up in bed, covers drawn up under her chin, Ella took a few bites of the bread and butter. She’d thought herself hungry but, although she had gulped down the cold tea, the bread tasted like ashes in her mouth and she struggled to swallow it. Doris’s words rang in her ears. ‘Little better than a cell.’ A cell was where her sister Alice had died, locked up all alone, denied any contact with her mother and with her baby. She couldn’t begin to imagine what that must have felt like. Then her thoughts turned to her mother, now living in Nortonstall with Thomas, Annie, Beattie and Beth. She hoped that the money she had been able to send them meant that they could have some sort of proper celebration for Christmas.

Ella wasn’t sure how long she had been sitting there, gazing sightlessly at the opposite wall, sighing occasionally and shedding a few tears, before cries from the garden below roused her. Aware of a change in the light, she looked at the window; large fluffy flakes were falling silently against a yellow-grey sky. It was snowing, and snowing hard. Ella swung her legs out of bed, shivering as her feet struck the cold floorboards, and wrapped the shawl from the end of her bed around her shoulders. From the window, she could see that the snow must have been falling for a while. The garden was thick with it and the dark, bare winter branches of the trees were tipped with white frosting. Across the pristine whiteness of the snowy lawn, John was racing up and down, spreading his boot tracks far and wide and uttering little yelps of excitement. He stopped suddenly, spread out his arms and flung his head back, mouth open. It looked to Ella as though he was trying to eat the snow as it fell and she smiled, wanting to bang on the glass and wave. Then she thought better of it and hastily drew back. She didn’t want John to spot her and to ask questions, the answers to which might upset him. It pained her to see him out in the snow on his own, with no one to share the fun. If she had been downstairs, she would have begged for a few minutes to spend outside with him. Mrs S would have grumbled but granted it: like all the servants she felt sorry for John, neglected in a household where his older siblings and parents were always preoccupied with their own concerns.

There would be no festivities for Ella this year. She tried to tell herself it was no different to previous years with the Ottershaws, but it was still a cruel blow. She couldn’t bear to think about what the future might hold if she were to be sent home. It would mean employment somewhere like the Ottershaws’ once again. A life of drudgery for very little reward, slaving for ignorant, boorish people who treated her like the dirt they employed her to clean up.

Ella clenched her fists, driving her nails into her palms. What had actually happened? She couldn’t imagine what had gone so wrong, but as the Christmas celebrations rolled inexorably on without her, she had plenty of time to reflect on the events of the past fifteen months, and what had put her in this awful position.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_b55a6531-fbcd-593e-a1ae-02e4c5f51d22)

Ella had first met Mr Ward on a Sunday in August the previous year back in Nortonstall, where she was a live-in servant and where the rest of the family now lived, forced to move away from their Northwaite home after the mill tragedy. On that particular day the sun was beating down with a ferocity the like of which Ella had never experienced before. She’d found it hard to tear herself away from six-year-old Beth, made fractious by the heat but cooled by a game involving a pail of water, set in the shade of the one tree that overhung their tiny yard. Ella, with her niece settled on her lap, had floated leaves as boats on the water’s surface, and then splashed her fingers to make waves to rock them, increasing her efforts to whip up a storm.

‘Watch out Beth, the waves are going to capsize the boats!’ Ella had tilted the pail slightly so that the water sloshed over Beth’s toes. Beth had screamed, her shock at the chill swiftly followed by delight.

‘Don’t get her over-excited, mind,’ Sarah, Ella’s mother, had warned, folding laundry that had dried almost as soon as it had been spread out to dry in the sun. ‘I’ll never get her settled after you’ve gone.’

Of course, when Ella’s home-time came, Beth had wailed and tried to tear herself out of Sarah’s arms, holding her hands out beseechingly to Ella.

‘Don’t cry,’ Ella begged. ‘I’ll come back as soon as I can. Be good until I do.’

Now, as she hurried towards the Ottershaws’ house, the cries were still ringing in her ears. She’d doubtless be in trouble for being late, even though she rarely had any time off at all. She worked for them all the hours she was awake, and she had the feeling that they would have had her work for them in her sleep too, if it were only possible.

Hurrying down the road, conscious of the sweat trickling down her back and darkening the fabric of her dress under her armpits, she began to wish she had left on time. It really was too hot to be out in this heat, let alone in a hurry.

She rounded the corner then halted, startled at the sight before her. At first, she couldn’t quite take it in. It was a motorcar, a rare enough sight in Nortonstall, where horse and trap or horse and cart were still the normal way of getting around, other than on foot. A motorcar was generally viewed with fear, and Ella understood this, being nervous of them herself. On the odd occasion that one had appeared in Nortonstall, it had travelled through at what seemed to Ella to be a terrifying speed and with a great deal of noise, scattering men, women, children, dogs, cats and horses in alarm.

This motorcar, its gleaming paint made dusty by the roads it had traversed was, however, stationary. Moreover, it seemed to be in some sort of trouble. At any rate, a man was standing at the front end of it from which a cloud of steam issued, along with a loud hiss. The man was wafting his hat somewhat ineffectually over the steam. He looked red in the face, whether from the steam or the heat of the sun, or because of the bother, Ella couldn’t be sure.

She put her head down, glancing out of the corner of her eye as she passed, but she didn’t speak. As a car owner, he was likely to be a gentleman and not someone she would expect to speak to her, either.

She had only gone a few paces before she heard, ‘Excuse me!’

She didn’t like to look back, but nobody else was around. Was he addressing her?

‘Excuse me! Miss?’

This time, she faltered in her step. It looked as though she was, indeed, the object of his attention. Feeling even hotter, with embarrassment this time, she turned to look back.

The man was facing her. ‘I wonder, do you know of anywhere I could get water around here?’

Ella took in his appearance. He was short, in early middle age with dark wavy hair and a prosperous air about him. He also looked as hot as Ella herself felt. She wasn’t sure if he required the water for himself, or for the car. She looked along the street. Normally it would have been busy, being the high road through town, with the shops open and bustling. But today was Sunday, and the road, shimmering a little in the heat haze, was deserted. The heat had taken everyone away, either to the cool of the river bank or indoors.

She hesitated. ‘I live’ – she caught herself – ‘rather, work, just around the corner from here. I’d be glad to fetch you water, sir, if you can wait?’

The man laughed. ‘I can certainly wait. I won’t be going anywhere for some time.’

Ella turned to head for the Ottershaws’, before turning back again.

‘Ah, how much water do you require, sir?’ She was still unsure whether he needed it for the car or himself.

‘A good question. If you were able to bring a jugful, that should suffice.’

He was either very thirsty or it was, indeed, for his car, Ella thought.

Even more conscious of her tardiness now, she hurried along the street, turning left to climb the steep slope of West Hill towards the Ottershaws’ house. It commanded a striking view over the town and appeared to be an imposing house from the outside. That impression was forgotten the minute you stepped through the door. A warren of small rooms led off a dark hallway and from each one, today as on any other day, there came the sound of a child crying.

‘So, you’ve deigned to come back. Do you realise what a burden you have placed on Mrs Ottershaw? How can you expect us to trust you the next time you say you want leave to visit your family?’

Mr Ottershaw had planted himself firmly in the hallway while Mrs Ottershaw, very red in the face and with her hair quite dishevelled, seemed to be grappling with several children at once in the parlour.

‘I’m very sorry, sir. I was detained on the way back. I’m afraid I will need to go out again but I promise I will return at once.’ Ella attempted to slip past Mr Ottershaw, who was having none of it.

‘Go out again! What can you be thinking of? With children to be fed and dinner to be prepared, and you already late? I will not have it!’

Mr Ottershaw stretched a beefy arm across the hallway to block Ella’s path. She dodged it with ease, and although he grabbed at her, he caught only air. As Ella headed for the scullery, she called back, ‘There’s a gentleman in the road. His motorcar has broken down. I promised to fetch water to help him get back on his way.’

When she returned, bearing a large china jug and a glass, Mr Ottershaw was in a more conciliatory mood. ‘A gentleman, you say. With a motorcar? Well, I shall accompany you to see whether I can be of assistance.’

Ella doubted whether there was anything Mr Ottershaw could offer that would be of use, his experience of motor vehicles being non-existent, but she said nothing to her employer. She hastened down the steps, Mr Ottershaw pausing only to seize his jacket and a hat as protection against the sun before closing the door firmly on Mrs Ottershaw’s protestations. Ella was already at the corner before he caught up with her, puffing and red-faced but determined not to be left behind. The car and the gentleman were as she had left them, although the gentleman had retreated into the small amount of shade cast by the wall of Taylor’s carriage works.

‘You came back.’ There was a hint of surprise in his statement and Ella was stung.

‘Why, yes sir, I gave you my word.’ She handed him the jug and the glass. ‘I thought that you might be thirsty, sir, standing out in this heat all the time.’

There was no ignoring Mr Ottershaw, who was bobbing impatiently at Ella’s elbow.

‘And this is my employer, sir, Mr Ottershaw.’ Ella tried to sound enthusiastic in her introduction.

‘Ottershaw at your service,’ he said, holding out his hand to the gentleman who, having no free hand to take it, had to pass the jug and glass back to Ella.

‘Mr Ward,’ the gentleman replied. ‘From York. I was returning there after conducting some business in the area but it seems my car didn’t appreciate the hills round here on a day like today. The engine appears to have overheated.’

Mr Ward took the glass of water that Ella had poured for him and gulped it down gratefully.

‘Thank you. That was most thoughtful. I hadn’t realised quite how thirsty I had become.’

Ella refilled his glass and held it while he turned his attention once more to the car.

‘Now, if you will forgive me, I will take up no more of your time. I will top up the radiator and be on my way. Would you mind holding the jug a moment?’ He spoke to Ella, as he needed both hands to loosen the radiator cap.

‘Oh, but you must come and take some refreshment with us, Mr Ward.’ Mr Ottershaw was clearly put out that Ella was getting more than her share of this gentleman’s attention.

‘I thank you kindly,’ said Mr Ward, ‘but my family will be concerned at my lateness. And I have been well provided with refreshment thanks to –’ Mr Ward hesitated. ‘I’m afraid I didn’t ask your name?’

‘Ella, sir.’

‘– thanks to Ella.’ Mr Ward took the refilled glass and drained it in one. ‘Now my car is suitably refreshed and so am I.’

Mr Ottershaw could feel the situation slipping away from him. ‘Mr Ward, my dear wife would never forgive me if I didn’t press you to join us. Just to step inside out of the heat, and rest yourself before your journey. We were just about to take tea. Pray, do join us.’

Ella watched the scene unfold with some amusement. Mr Ottershaw may have considered himself a man of some importance in Nortonstall, but he was out of his depth with the likes of Mr Ward. The thought of such a gentleman stepping into the Ottershaws’ parlour for tea was in danger of making her break into unseemly laughter and she had to turn away, setting down the empty jug and glass to hide her expression.

Meanwhile, Mr Ward had climbed back into the driver’s seat and already had the engine running. Ella stepped back in awe – the vehicle was transformed from a broken beast into a growling, noisy monster. It suddenly seemed much larger and more dangerous than it had before. Mr Ward beckoned her to come closer, so that he didn’t have to shout over the noise of the engine.

‘Ella, I am most grateful for your help. I feared that I would be stuck in this god-forsaken place for the night. It seems to me that you work for a fool…’

Ella started and glanced nervously at Mr Ottershaw to see if he had heard, but he was too busy mopping his red, perspiring face with a handkerchief to be paying any heed.

‘Should you ever wish for a change of employment, I know Mrs Ward would be delighted to have a maid with even a modicum of intelligence in our house in York. Take this, and write to her.’

Mr Ward pressed a pasteboard card into Ella’s hand. She glanced at it before secreting it swiftly in her pocket, hoping that Mr Ottershaw hadn’t witnessed the action. Ella stepped back again, Mr Ward put the car into gear, nodded to them both and with a roar and a not-inconsiderable amount of dust, the car and the driver went on their way. The road seemed suddenly very quiet and still.

‘Well,’ said Mr Ottershaw, very put out that he had been side-lined. ‘I must say, he was rather a rude man. Why did he wish a private word with you, Ella? Quite improper, I felt.’

‘Oh no, Mr Ottershaw, he just wished to thank me again.’ Ella was relieved that no mention had been made of the card. She felt very conscious of it, hidden deep in her pocket. Employment in York – could such a thing be possible? Could she go, leaving her mother and Beth behind?

Ella sighed. She didn’t have to ask herself the same question about the Ottershaws. She knew they would make her life doubly hard for the rest of the day: Mr Ottershaw resentful of the attention she had received and Mrs Ottershaw furious with both of them for leaving her alone so long with the children. It would be a hard end to a hot day. But an exciting day, nonetheless. Ella had a secret but, she reflected as she trudged back up the hot and dusty road, it was one that she could do little about. She could neither read, nor write. And she certainly wasn’t going to be able to ask the Ottershaws to help her with either of those things.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_197d6ac0-a716-556e-8620-bff549d65dd0)

Ella hugged her secret to herself. The memory of what Mr Ward had said, and the possession of his card, sustained her through several trying weeks in the Ottershaw household. When the children fell ill one after the other, so that the kitchen was awash with bedclothes hanging to dry and the house filled with the crying or moaning of infants, day and night, Ella stoically carried on. She had some sympathy for the children, even when faced with a succession of permanently running or crusted noses, their seemingly endless capacity for being sick and the often-rude manner, learnt from their parents, in which they summoned and treated her.

Mr and Mrs Ottershaw were another matter. They liked to let it be known that Ella was there on sufferance, out of the goodness of their hearts in employing someone whose sister had, in their view and, it would seem, everyone else’s view, committed a hideous crime. It seemed to Ella that their apparent Christian charity was an excuse to misuse her, to pay her even less than the pittance considered a fair wage (‘as no one else will have you’), to work her all hours (‘you will understand the risk we have borne in taking you in’), and to refuse her the right to visit her family (‘the afternoon off? How could you ask this of us after all we have done for you?’).

It was only when they refused Ella a visit home after she had had word that Sarah, too, was struggling with a house full of sick children – Ella’s siblings Thomas, Annie and Beattie having taken it in turn to succumb, with niece Beth now gravely ill – that she finally snapped. Mr Ottershaw, in his usual pompous manner, had denied the request, citing a concern that she would return bearing yet more illness into the bosom of his family, then buried his head back in the newspaper. Ella had retired quietly to the kitchen. Two pink spots of rage burnt in her cheeks. She stood in the centre of the room, fists clenched, and thought but for a moment or two. Then she undid her apron, folded it and laid it over the kitchen chair, and went into the small room off the kitchen that served as her sleeping quarters. She took her few possessions off the shelf along with the dress that hung behind the door, and wrapped them in a woollen shawl. Then she drew her good shawl around her shoulders and stepped back into the kitchen. After a moment’s indecision, she went to the china pot at the back of the dresser shelf, where she knew that Mrs Ottershaw kept coins to pay the small bills of tradesmen, and took what little lay in there. It would have to do in lieu of the money she was owed for the month just worked, for which she reasoned she was unlikely to be paid. She slipped the coins into her pocket, where Mr Ward’s card still nestled reassuringly, and set off for the front door. In the hallway, she hesitated before knocking on the parlour door, and entering. Mr Ottershaw, irritated, looked over the top of his newspaper.

‘I’ll bid you and Mrs Ottershaw a good day, sir. And I hope you will be more fortunate in the future in finding a servant that suits,’ and with a nod Ella left the room, and the house, before Mr Ottershaw could reply.

She was trembling, whether with anger, shock or terror at what she had just done, she could not say.

Sarah listened without comment to her tale when she reached home, then hugged her and sent her to fetch ink and paper. While Ella set to, mopping fevered brows, singing calming songs and bringing cooling drinks of water for the sickly family, Sarah wrote a note to Mrs Ward and took it herself to the post office. When Mr Ottershaw came to the door that evening to demand that Ella should return, having broken the terms of her employment, Sarah informed him that he was putting himself at risk of the fever in coming to their house. Furthermore, she had reason to believe that the Ottershaws themselves had broken the terms of their contract with Ella on many occasions and they should make it their business to look elsewhere for a servant. And with that she shut the door firmly in his face.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_20c9f766-7d3a-5106-9214-967943133f57)

When word came back that Ella was to present herself as soon as possible at the Ward household in York, she was thrown into a panic. Once she had escaped the drudgery of the Ottershaws’ house, the planning of her further escape from Nortonstall had been all consuming. Now that it was going to happen, Ella was seized with doubt. She had never left the confines of her immediate locality before. Although in her younger years she had roamed far and wide across the fields and moors, she had barely travelled a distance greater than five miles from home. Now she was to travel nearer sixty, and the greater part of that journey was to be via the railway, from Nortonstall to Leeds and then on to York. Although the railway had run through the town for a while now, there were still those who viewed it with deep distrust and wouldn’t dream of setting foot inside a carriage, let alone allowing it to transport them anywhere. Ella had seen and heard the trains as they passed through the town, but she had never had reason, nor the money, to take one. Nor, if she was honest with herself, did she wish to. The Wards had enclosed her fare for the trip and, although Ella had favoured the idea of begging a ride with a carter leaving Nortonstall for Leeds, Sarah wouldn’t hear of it.

‘When have you ever been to Leeds?’ she demanded. ‘You won’t have the first idea of how to go about finding yourself a ride from there to York.’

‘Yes, I will.’ Ella was defiant. ‘The carter can help when I alight. He’s bound to stop at an inn and it will be easy to ask around there to find someone who’s travelling on to York.’

‘Well, I won’t have it,’ Sarah said. ‘You’ll be lucky to accomplish the journey in a day, so you’d have to find lodgings or journey through the night. All manner of things could go wrong.’

She was working herself into a state and even Ella began to be daunted by the possibilities of unforeseen disaster.

‘In any case,’ Sarah continued, determined to put a stop to the debate. ‘Mrs Ward has sent you the fare and will expect you to arrive in good time, and fresh to start work. The train it must be.’

So Ella found herself standing on the platform at Nortonstall station, watching anxiously down the tracks as the engine approached, a plume of steam trailing through the chill morning air behind it and hanging there, like mist. A great flourish of squealing brakes and belching steam heralded the train’s arrival at the platform, quickly followed by a rush of activity as doors swung open, porters were hailed, and the passengers who had been waiting quietly on the platform were now galvanised into action. Ella stood for a moment, bewildered and made nervous by the noises of the train at rest, the creaks and groans of the metal and the chug of the engine.

‘Are you taking this train? You’d best make haste, miss.’

One of the porters, wheeling a trolley of mail sacks, paused momentarily beside her. Ella shook herself free of her reverie in time to realise that the doors were closing and the only people left on the platform were passengers leaving the station.

‘Third, is it?’ the porter said. ‘There, the last carriage. Hurry now.’

Tightly clutching her bundle of belongings and pasteboard ticket, Ella all but ran along the short platform to the last carriage. A whistle blew as she put her foot on the carriage running board and hands reached out to take her arms and pull her in as the train started to move, with a squeal of protest and yet another belch of steam. The door was slammed behind her and Ella, suddenly breathless, stood embarrassed among the men pressed up by the door.

They passed her between themselves like a parcel until she found herself at the end of the rows of hard bench seats, which faced each other and were mainly occupied by women clutching baskets and small children.

‘Any room for a little ’un?’ one of her rescuers asked cheerfully, and a woman at the end of the bench obligingly scooped up a young child and made room for Ella to sit down.

‘Nearly miss it, did you?’ she asked, looking Ella up and down.

‘I… why, yes, I suppose I did,’ said Ella. She sat in silence for a minute or two, aware of her fast-beating heart and the high colour on her cheeks.

‘I’ve never travelled on a train before,’ she suddenly blurted out to her neighbour.

The woman laughed, while a couple of near neighbours smiled.

‘Well, you’ve discovered the joys of them now, love. No going back. They’re the quickest way to get around. Where are you headed?’

‘York,’ said Ella. ‘Well, Leeds first.’

‘Best watch yourself at the station,’ her neighbour advised. ‘Plenty of people there looking to take advantage of a young girl like you travelling alone. Keep to yourself and keep a tight hold on your things.’ She glanced at the bundle, bound up in a shawl, on Ella’s lap. ‘There’s plenty there whose job it is to part you from your possessions.’

Ella spent the rest of the journey taking in her surroundings and getting used to the novelty of seeing the countryside moving fast past the window as she tried to settle herself on the hard, slippery seat. After a while, fields gave way to rows of back-to-back houses and, an hour after she had climbed on board, Ella stepped down from the carriage and onto the platform. She stopped, transfixed. The other alighting passengers bumped and jostled her but she was oblivious. She’d never seen a building quite like it: great metal arches soaring skywards and everywhere noise echoing and the smell of coal fumes hanging in the air.

Light streamed in through the huge curved glass roof as well as from the end of the great building. Here, where the station opened out onto the tracks, Ella could see the comings and goings of even more trains. There weren’t just two platforms, as at Nortonstall, she quickly realised as she let herself be carried along with the remaining passengers heading for the gate, but many platforms.

‘The train for York?’ she enquired tentatively of the man at the gate, who was checking and taking their tickets.

‘Not here, love,’ he said. ‘You need New Station.’ Ella was dumbfounded. She hadn’t realised she would need to change stations, as well as trains. The ticket collector looked her up and down, taking in her bundle and lost expression, and took pity on her. ‘It’s just around the corner. Follow Wellington Street, then turn into Bishopgate Street. You can’t miss it. Follow the crowd.’

Ella did as he said, tagging along behind a group of people who were striding purposefully along as they left the station. Nonetheless, her heart was beating fast and she was worried that she might get lost. She barely had time to register how big and busy the streets were, and how tall and grimy the buildings, before she found herself turning away from a grand square straight into bustling crowds of people who were coming and going from a vast and forbidding brick-built building, much larger than anything she had ever seen before. Once inside, Ella was quickly overawed by the size of the space and the confident manner in which the other travellers seemed to be going about their business. Enquiring somewhat timidly about the next train to York, she was directed to the ticket office where she joined a queue, feeling anxious as to whether she would have enough money left over to cover the fare then thankful that she did, and that procuring it hadn’t been as difficult as she had feared.

With the new ticket safely in her possession, she decided to find the platform straight away. Mindful of the words of her companion on the earlier train, she kept her head down and her bundle clutched tightly to her.

It was only when she reached Platform Two and ascertained that she still had a half hour’s wait before the York train that she felt able to relax a little and take a proper look around. It seemed as though trains were arriving every few minutes, the doors flying open to disgorge a rush of passengers from the second- and third-class carriages, all intent on going about their business, while the first-class passengers descended at a more leisurely pace, looking about them for porters to take their luggage, or strolling away, the ladies elegant in long skirts and tailored coats with glossy fur collars, fashionable feathered hats on their heads, arm in arm with gentlemen in smartly cut suits. Ella stared in awe, saved by the distance from appearing rude. She had never seen such fashionable, well-dressed people before. In Nortonstall, people dressed for practicality and hard work, with their best clothes saved for Sundays and funerals. Such an array of colours and fabrics as was now passing before her was unimaginable. Cream wool coats trimmed with dark brown fur, rich russet jackets bound with black, hats in red or maroon velvet, decorated with great swoops of feathers.

Ella shivered in the cold wind that swept through the station concourse and pulled her shawl tighter around herself, suddenly very conscious of her dowdy appearance. She’d peered into the Ladies’ Waiting Room as she had passed it, but had been too daunted by the smartness of the occupants to consider entering it. The warmly lit interior of the station café was appealing; she would dearly have loved a cup of tea to warm herself, but was worried both about the expense and feeling out of place.

With a great deal of self-important puffing the train for York finally pulled in, sending clouds of steam billowing up to the roof. Ella hung back as the door opened and the wave of passengers swept by. Those in a hurry were already hovering on the running board with the carriage doors open as the train slowed to a halt; others descended at a more leisurely pace, the ladies pulling on gloves and straightening hats, checking on their travelling companions before heading off to – Ella couldn’t imagine what. Shopping? Visiting friends or relatives? A life of leisure activities wasn’t something she had ever thought about, nor did she have time now. Instead, it was time to take her seat in the third-class carriage, mercifully less crowded than before, and to contemplate what might await her at the other end.

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_bc6a8aca-b25f-528c-aa76-e3de60a28414)

Ella followed the other passengers out of York station then hesitated, unsure of which way to turn. She ignored the line of hansom cabs waiting for fares, looking instead to her left and right for someone who might help her with directions. Tucked away at the far corner of the station façade she spotted a vendor selling flowers and made her way towards him. His face brightened at her approach.

‘I wonder, could you help me? I need to get to Knavesmire.’

The man sighed. ‘It’s always directions. Hardly ever a sale. If I had a farthing… Ah well, never mind, I’m happy to help a pretty lass like you, with manners to match.’

He pointed out the route that Ella would need to take, advising her that it was not much over a mile, before he offered her some anemones. Waving away her protests that she couldn’t pay, he pinned a couple of flower heads to her shawl.

‘They’re out of season and I’ve barely enough to sell. It will help brighten up a grey day for you. I wish you luck.’

Ella thanked him for his kindness and set out. Before she turned away from the city, out towards Knavesmire and the countryside beyond, she took a moment to gaze at the high grey-stone walls, set atop great green-carpeted mounds of earth, which surrounded the city. Within, she could make out an imposing church tower and a jumble of roofs while up ahead of her a turreted stone arch, the like of which she had never seen before, linked two sections of the wall over a road that led into the city. Lingering, she wondered whether she had time to step through that arch and discover what lay beyond it. Instead, promising herself that she would return to explore further at the first opportunity, she turned her back on the city and set out, facing into the wind. Before long, the streets of small terraced houses that led off from each side of the road gave way to grander houses set in large plots ranging along one side of the road, facing onto a great swathe of green on the other.

As a chill mist drifted across from Knavesmire, Ella found herself standing before Grange House, a house quite unlike anything she had ever seen. Set back behind a low wall, with a sweep of gravel in front, it had an oddly top-heavy appearance. Two storeys high, with additional windows in the attic, it had a prominent gable at one end, half-timbered at the top only, with this feature repeated around some of the windows and the front door. Perhaps most startling to Ella was the redness of the brick. The houses in Northwaite and Nortonstall were all built of grey stone with grey-slate roofs. This one was set beneath a red-tiled roof, and although the windows had pale sandstone surrounds, the predominant effect, Ella felt, was of a house shouting ‘look at me!’ to anyone who passed by. Her momentary doubt that she had come to the wrong place was quelled by the sight of Mr Ward’s motorcar parked on the immaculately raked gravel in front of a separate brick-built building. Ella, sensing instinctively that she would not be expected to approach the grand front door, looked anxiously around for another way in. She spotted a discreet gate tucked into the side of the wall and, biting her lip in a sudden surge of anxiety and shivering hard in the chill mist that rolled in ever more thickly from across the road, she opened the gate and followed the path round the house.

Her first timid knock at the dark-painted solid door remained unanswered. Steeling herself, she seized the knocker and let it fall once, twice against the wood. Ella was filled with a sense of panic – why had she ever thought it a good idea to leave behind the safety of the hills and valleys where she had spent all her life, where she knew every person, every path, bird and flower, for a place as foreign as this? The thickness of the door blotted out any sounds from within and so Ella, poised to flee, was startled when it opened suddenly, revealing a girl little older than herself in a maid’s uniform. A warmly lit interior was visible behind her.

‘Mrs Sugden, it’s the new girl,’ the maid called over her shoulder, before seizing Ella’s arm and pulling her into the hallway.

‘You’re frozen,’ the girl remarked before an older, larger lady appeared, her dark dress rustling as she moved, grey curls pinned back from a face that appeared stern, but broke into a welcoming smile at the sight of Ella.

‘Thank you, Doris. Please go and attend to the bell, then when you come back you can show – Ella, isn’t it – to her room. Ella, come this way.’

Ella found herself propelled into a small room off the hallway. Set up as a mixture of office and parlour with heavy ledgers piled on a big desk, it had a welcoming fire burning in the grate.

Mrs Sugden pushed Ella gently towards a chair by the hearth.

‘Sit yourself here and get warm. You look done in.’

Ella, gratefully taking the suggested seat, registered the note of concern in the housekeeper’s voice.

‘Have you eaten? You’ve missed lunch but I will ask Cook for a cup of tea, then we can discuss your duties here.’ And with that Mrs Sugden, bustling in the purposeful manner to which Ella would soon become accustomed, left the room. She returned shortly after, bearing a cup of tea in a plain china cup and saucer, setting it on a table beside Ella who, overwhelmed by the strangeness of this long-anticipated situation and the unexpected kindness of the housekeeper, found herself close to tears.

‘Now, when Doris comes back she’ll show you to the room that you’re to share with her so you can freshen up and put your belongings away.’ Mrs Sugden glanced briefly at the bundle Ella clutched on her lap. ‘Then you can meet the rest of the staff at tea. We’ll need to fit you for your uniform.’ Mrs Sugden paused to scrutinise Ella. ‘You’re taller than I expected and a good deal more slender but I daresay we will find something that will do for now. I know little about your experience other than what was in your mother’s letter so I think it best to keep you in the kitchen for the first few days until I’ve seen what you are capable of, and where you’ll best fit. Now, drink up that tea before it goes stone cold.’

The remainder of the day passed in a whirl that left Ella’s head spinning by the time she fell thankfully into bed. Doris, who was in possession of a head of auburn curls and a tidy, well-formed figure, had brought her up to their shared room after her interview with Mrs S, as she had called her, and had sat on the bed watching as Ella unwrapped her belongings.

Horribly conscious of how few things she had, and how shabby they might look to someone else, Ella turned her back on Doris as she shook out a couple of dresses and quickly hung them up. She laid her hairbrush on the top of the chest of drawers, folded a few undergarments into one of the drawers and then turned.

‘There, done,’ she said.

Doris had been watching her without comment. ‘You didn’t bring much with you,’ she remarked.

Ella felt her colour rise. ‘No,’ she replied, and then hesitated, unsure of what to say.

Doris regarded her shrewdly. ‘No matter. You’ll be in uniform most of the day. We’d best go and see what we can find to fit.’

In bed later that night, Ella had relived the embarrassment she had felt in front of Doris and, later, Mrs Sugden. It was already late and she had to be up at five, but her head was buzzing with the effort of taking in so much new information. The room was dark but she could make out the shape of Doris in the next bed, already peacefully asleep. She ran through what she could remember of the other staff: apart from Doris, she had met Rosa who was lady’s maid to Mrs Ward, Mrs Dawson the cook and Mr Stevens the butler. At the tea table, she had learnt of the Wards’ three children: three well-grown daughters, Edith, Ailsa and Grace and a son John, who was only six. She had listened to the gossip as the servants gathered to eat before heading off to fulfil their evening duties. Mrs S had then shepherded Ella to a tall cupboard in the servants’ hallway, unlocking it with one of the keys on a chain kept at her waist. She’d pulled out several dresses and held them up against Ella, narrowing her eyes and pursing her lips as she assessed the fit.

‘I think these will do. Try them on in my room for size. This one is for the kitchen, but if you make progress and go above stairs, you’ll need this,’ she said, indicating the darker of the two dresses. ‘Mrs Ward will be pleased if we can make do with what we have here rather than having to order up something new. You are tall, which means you could do very well above stairs, but we must be sure that does not cause your dresses to be too short. Too much ankle will never do.’