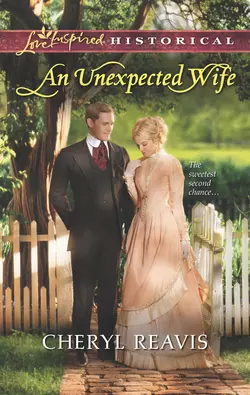

An Unexpected Wife

Cheryl Reavis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Giving up her out-of-wedlock son was the only right choice. Still, Kate Woodward aches that she isn’t part of his life. She can’t heal herself, but she can help ex-Confederate soldier Robert Markham rebuild his war-shattered life. But helping Robert is drawing them irresistibly close—even as Kate fears she can never be the one he deserves …Battlefield loss and guilt rekindled Robert’s faith and brought him home to Atlanta. And Kate’s past only makes him more determined to show this steadfast, caring woman that she deserves happiness.Now with her secrets revealed and her child in danger, Robert has only one chance to win her trust—and embark on the sweetest of new beginnings …