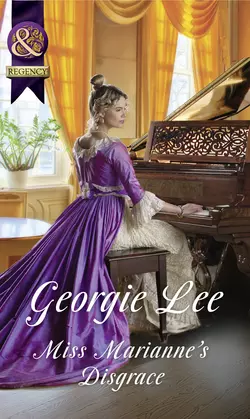

Miss Marianne′s Disgrace

Georgie Lee

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Rejected by the tonTrapped in the shadow of her mother’s notoriety, Miss Marianne Domville feels excluded from London society. Her sole comfort is composing at her pianoforte, until author Sir Warren Stevens brings a forbidden thrill of excitement into her solitary existence…Through his writing, ex-Navy surgeon Warren escapes the memories of cruel days at sea. So when he finds Miss Domville’s music and strength an inspiration, he’s certain the benefits of a partnership with this disgraced beauty will outweigh the risks of scandal…if she’ll agree to his proposal!