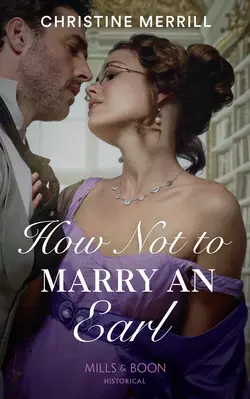

How Not To Marry An Earl

Christine Merrill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 465.10 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The plainest Strickland sisterIn the Earl’s arms!Part of Those Scandalous Stricklands: To escape marriage to the new Earl of Comstock, bookish Charity must find her family’s missing diamonds. She meets her match in an intellectual stranger auditing the estate…little knowing he is Lord Comstock himself! With him, Charity feels different—even desirable! But will seizing one night of passion bind her to the very man she’s determined to avoid?