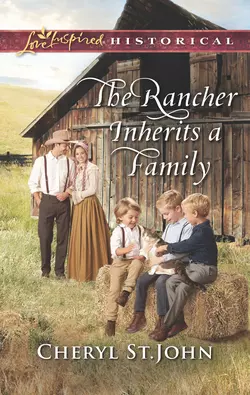

The Rancher Inherits A Family

Cheryl St.John

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Unexpected FatherThe pretty redhead Seth Halloway pulls from a derailed train has surprising news for him. The children she’s accompanied to Cowboy Creek aren’t hers—they’re his, thanks to the last wishes of a late friend. Busy rancher Seth must suddenly cope with three rambunctious boys…and try to ignore his growing feelings for independent Marigold Brewster.Marigold hopes to start over as the town′s new schoolteacher. She’ll choose her own path, and stay aloof from the adorable Radner boys—and their guardian. But the man who rescued her from a wrecked railcar might just be the one to save her from loneliness…if she dares to let him in.Return to Cowboy Creek: A bride train delivers the promise of new love and family to a Kansas boom town.