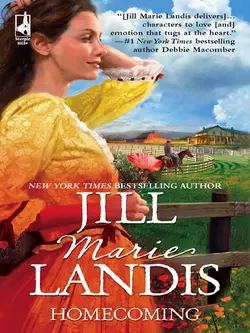

Homecoming

Jill Marie Landis

Tell me who I am. Tell me where I belong.I am a woman without a name, without a home….For the first time, Eyes-of-the-Sky prayed to the white man's God. One look in the mirror told her she was not a Comanche…yet she remembered no other life. She watched the whites who had taken her in after her "rescue," the mother, Hattie, and her handsome son, Joe, and wondered what her life had been like before her childhood abduction. She looked at Joe, who had suffered much and forgave little, and knew longing in her heart. But questions remained: What am I? Who am I?

Critical praise for

JILL

Marie

LANDIS

and her novels

“Jill Marie Landis’s emotional stories will stay with you long after you’ve finished reading.”

— New York Times bestselling author Kristin Hannah

“Jill Marie Landis creates characters you want to spend time with and a story that will keep you turning the pages.”

— New York Times bestselling author Susan Elizabeth Phillips

“Jill Marie Landis can really touch the heart.”

— New York Times bestselling author Jayne Ann Krentz

“Ms. Landis gifts readers with a remarkable multi-layered love story that touches the heart.”

— Romantic Times BOOKreviews on The Orchid Hunter

“Readers will weep with sorrow and joy over Landis’s smart and romantic tale.”

— Booklist on Magnolia Creek

“In this gripping and emotionally charged tale, Landis delivers another unusual, beautifully crafted romance.”

— Booklist on Blue Moon

Homecoming

Jill Marie Landis

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For my grandmothers, Maria and Ruby.

For Margaret, my mother.

And for Joan and Melissa.

Thank you for helping me find

the joy in writing again.

I have been a stranger in a strange land.

— Exodus 2:22

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

Chapter One

Texas, 1873

G unshots echoed in the distance. The acrid smell of smoke and blood and burning flesh poisoned the evening air. In the sparse, brittle grass growing on the bank of a dry creek bed, a young woman lay facedown, clinging to handfuls of dirt, anhoring herself to the land.

Pebbles cut into her cheek as she pressed closer to the earth. Barely breathing, she feared the attackers would find and kill her, just as they’d killed the others—her mother and father, the old ones. White Painted Shield had just brought her father fifty fine horses as a bride price. Tonight he would have become her husband—and now he was dead.

Moments ago, when the first shots rang out, confusion and panic sent everyone grabbing weapons and children, scattering for cover. Her husband-to-be was one of the first to realize what was happening. He’d grabbed her little brother, Strong Teeth, and shoved the boy into her arms. Then he pressed the hilt of his own knife into her hand and commanded her to run.

She hesitated, confused and reluctant to leave. It was the way of the women to fight. They had been trained to battle as ferociously as the men. Then the Blue Coats were bearing down on them all and suddenly her instinct to save the child sent her running for cover. White Painted Shield lifted his carbine and fired.

He was cut down before her eyes.

Heart pounding, her head filled with the cries of the dead and dying, she clung to her little brother’s hand and sprinted away from the echo of gunshots, the thunder of hooves, the destruction.

She thought her heart would burst before she reached the open plain. Gasping for every breath, she expected the white-hot pain of a bullet to rip through her flesh.

As they ran toward the creek bed funneling through a shallow ravine, Strong Teeth suddenly crumpled, his little legs bending like broken twigs as they folded beneath him. She pulled his lifeless body into her arms.

His blood smeared the front of her beaded clothing, ruined the garment it had taken her mother, Gentle Rain, weeks to bead. She stared down into the six-year-old’s unseeing eyes, knew there was no hope yet clung to him a moment longer.

Chaos erupted around her, but she took precious time to gently lower him to the ground before she ran on. She gathered speed, fueled by fear so intense it became all consuming. As she ran, she found herself thinking not again and was haunted by the notion that she’d somehow lived through this all before.

With each footstep she heard Gentle Rain’s voice in her mind.

Keep your head down. Never let them see your eyes.

So the young woman kept her head lowered when she slid down the dry, sandy bank. She hit the ground hard, bumped her cheek against the dirt with such force that her lip split. She tasted blood. Flinging her left arm up, she covered the back of her head with the crook of her elbow and tucked her right arm beneath her, hiding the knife she still clutched in her hand.

Tonight I was to become White Painted Shield’s wife.

The dream she’d cherished for so long had become a nightmare.

As the onslaught wound down, single gunshots rang out here and there in the distance. Except for fires crackling as dwellings burned, the world became deathly silent. The sky was filled with billowing spirals of smoke drifting like flocks of black vultures, obscuring the late-afternoon sun.

She thought she was safe until the ground began to shake as mounted riders thundered near. Their shouts drifted to her, strange words in a language rough and foreign and yet the words haunted her, conjuring flashes of nightmarish memories. Images that confused and frightened—flames and smoke and blood—much like everything she’d seen today, but different somehow.

Hide your eyes.

A few of the riders passed by, but then there came a shout. Nearby, a horse whinnied. She recognized the creak of a leather saddle before she heard heavy footfalls above her. When the sandy soil gave way beneath a man’s tread and a rain of pebbles and dirt sifted down on her, she didn’t dare look up.

More shouts as the man called out to the others. Though she couldn’t understand him, he sounded excited. She bit her swollen lip, swallowed a scream when he roughly jerked her to her feet.

Refusing to look up, she trembled as she stared at the bloodstains on her beaded moccasins and was ashamed of her cowardice. The front of her long doeskin shirt was stained with blood, the blood of her little brother.

He died bravely today.

So would she.

My marriage day.

A good day to die.

The man in front of her stank of sweat and fear and hatred. He grabbed her chin. Forced her to raise her head.

Never let them see your eyes.

She tried to keep her eyes closed, but what did it matter now? What did anything matter? Her family, her betrothed, were dead. Everyone she loved was gone.

Filled with anger and defiance, she raised the hidden knife, intent on plunging it into his heart. But he was bigger, stronger. He grabbed her wrist and twisted. She cried out at the shock of pain. Her fingers uncurled and the hunting knife fell to the ground at her feet.

She raised her head at last and stared into his cold, hate-filled eyes and willed the bearded white man to take her life. There was fury in his gaze, along with an anger that left no doubt that he wanted to kill her.

Do it now, she thought. Kill me, Blue Coat, so that I can join the others.

Suddenly, the hatred in his eyes turned to shock and he began shouting to the others. This new excitement in him frightened her more than his hairy, sun-burned face, his foreign scent, his rough hands.

Three men on horseback watched as he struggled to drag her up the shallow ravine. His fingers bruised her upper arms and his grip twisted her shoulder, but she refused to cry out.

The smell of death tainted the air. The Blue Coats had killed her family—her mother, her father, her husband-to-be, her little brother. Her many friends, the wise elders, Bends Straight Bow, her grandfather.

The Nermernuh, her people, were scattered, dead, dying.

The Blue Coats had captured her.

It was a good day to die.

Chapter Two

S pring was Hattie Ellenberg’s favorite time of year. A time of beginnings when the snow and ice turned to warm rain, trees swelled with the buds of new life and God’s promise of a bountiful fall harvest was evident everywhere. The coming of spring tempered the bleak, desolate bite of winter with its dark memories and images of bloodstained snow.

Hattie took joy in the small gifts of spring, the way the birds sang with riotous pleasure at the break of day, the early morning sunlight that flooded her bedroom. Somehow the puddles of sun, warm as pools of melted butter, made her feel more alive and less isolated.

Each year, as the first spring wildflowers bloomed, she asked her son, Joe, to move the old kitchen table out of the barn and onto the shade of their wide covered porch. There, they would take their meals beneath the roof of the low, wide overhang, even through the dog days of summer.

When she woke this fine morning, she had no idea Jesse Dye would be paying them a visit. Now here she was, sitting on the porch at that very table with the former Confederate soldier and seasoned war veteran.

She smoothed her work-worn hands across the faded gingham tablecloth, absently wished she’d mixed up a sage-scented salve to smear into the reddened cracks around her knuckles. She’d never been a showy woman and her looks certainly didn’t matter anymore. Certainly not to Jesse, a man in his late thirties who had been raised on a ranch a few miles south of their own Rocking e Ranch. They’d known Jesse forever. Now he was a U.S. Army captain fighting the fierce Comanche, a plague on the Texas frontier for nearly a century.

The sight of her chapped hands embarrassed her almost as much as the wide scar above her forehead. The minute she’d seen Jesse riding into the yard, she’d grabbed her poke bonnet off a hook by the back door and wore it to hide the puckered swath of baldness.

“Will you do it, Hattie?” Jesse leaned back in his chair, casually resting one booted foot over his knee and propping his wide-brimmed hat atop it. A wisp of warm breeze barely ruffled the hem of the tablecloth as he added, “Will you take her in?”

“You know what you’re asking, don’t you?” She couldn’t believe one of the few friends they had left was laying this challenge at her feet.

“If I didn’t think you were exactly what she needs—if I didn’t think you could do this, I wouldn’t be here.”

Her pulse accelerated and a wave of dizziness assailed her. Hattie closed her eyes for a heartbeat and waited. As always, her panic eventually abated.

“It’s been eight years, Hattie.”

“Joe will never agree.”

“Why not ask him?”

Her own emotional concerns aside, she knew how deep Joe’s bitterness ran. He not only blamed himself for not being there when she’d needed him most, but he’d lost his faith in himself and, worse yet, in God.

Hattie clung to her faith now more than ever. Faith filled the hollow places, banished the darkness that might have otherwise taken her down. Faith gave her the strength to forgive, the will to get up and face each new day knowing the Lord was always with her.

But now, Jesse was asking her to do more. He was asking her to take action, to prove forgiveness was not just a word or a thought, but a deed.

She struggled for a way out.

“I’m sure there must be someone else, some other family willing to care for her, Jesse.”

She surveyed the land that had once held so much promise, remembered how thrilled her husband, Orson, had been the day they’d staked their claim. So long ago. So many memories were buried here. Memories and pieces of her tattered heart.

She studied Jesse, amazed he’d ridden all the way out from Glory on a fool’s errand.

“She’ll only be here until we locate her family, Hattie.”

Hattie reached up, smoothed back a strand of hair that had escaped the back of her bonnet and trailed down her neck. She let her imagination run loose, tried to picture a young woman sleeping in the empty room upstairs, the room that hadn’t been used since Melody died.

She had no doubt this was God’s hand working through Jesse. In the beginning she’d struggled to forgive the harm done to her, the injuries inflicted upon her, the taking of her loved ones. Eventually, she’d succeeded, or so she thought. Setting aside the past was the Christian thing to do.

Nine years ago she would not have hesitated to say yes if asked to help, nor would Orson. They would have opened their door and arms to anyone in need. But Orson was gone and so was little Melody, and now Hattie didn’t know if she had the courage to say yes. She was scarred inside and out. She wasn’t the woman she’d been then.

Besides, even if she agreed, Joe would never stand for it.

Oh, how she wished Orson was here. But then, if Orson was still alive, things would be different. Joe might be different.

But he’d been a rebellious youth before Orson and Mellie were killed and now he was a bitter young man.

“Is she…dangerous?” Hattie met Jesse’s gaze, hoping to measure the truth of his answer.

“She hasn’t shown any violence. Hasn’t tried to escape. She may not even be right in the head anymore, but she looks to be sane. Only God knows what those savages did to her.”

“How old is she?”

“Hard to tell. Maybe eighteen. Maybe younger. Maybe a year or two older. No way to know how long she’s been a captive, either. She doesn’t speak English anymore. That’s how long.”

“I just don’t know what to tell you, Jesse.”

Her Melody would have been sixteen in August; Mellie with her cherub’s curls and bright green eyes. Mellie was the light of all their lives before the Lord saw fit to take her. Both Melody and Orson at once.

Only by her faith in the goodness and workings of the Lord had Hattie made it through her darkest days, her bleakest hours. She slowly convinced herself that her work here was not finished or He’d surely have taken her, too, and spared her the pain.

The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.

Was this opportunity His way of giving her back something she’d lost? Was this challenge another test of her faith?

Even if she agreed to take the girl in, Joe would still have to consent. But she doubted he’d ever shelter a former Comanche captive, someone who’d been with the Indians for so long she no longer spoke English, someone who had taken on their savage ways.

Try as she might, Hattie could not stop thinking of the damaged young woman in need of a place to recover from unspeakable hardships. A young woman who needed her —

Only another survivor could understand.

Hattie noticed her hands were shaking as she lifted the China chocolate pot covered in dainty yellow roses. It seemed a century ago that she’d carefully wrapped it in yards of calico along with the rest of her mother’s dishes before moving them across the country.

“More coffee, Jesse?” In his eyes she saw glimpses of the same bleakness that was ever present in Joe’s nowadays. Both men had witnessed too much bloodshed and far more violence than they deserved. But Jesse Dye was a good ten years older than Joe. And Jesse had chosen his lot in life. He’d been a soldier since the first Confederate regiment was formed in Texas.

It wasn’t right that Joe, at twenty-five, was already burdened with guilt over a past he couldn’t change.

Unlike her, Joe had lost his faith in everything good and true and right. He’d completely given up on God the night his father and sister had been murdered by Comanche raiders, the night he found her, his mother, ravaged and left for dead.

Since then, his guilt and the hardships of life on the Texas plains had beaten the joy out of him, made him too soon a man.

Jesse declined her offer of more chocolate and, a moment later, Hattie nearly jumped out of her skin when she suddenly heard Joe’s footsteps behind her.

She turned as her son came walking across the porch, rolling down his shirtsleeves as his long-legged stride brought him to the table. The collar of the brown-and-white-striped shirt she’d made him was damp. So, too, was his dark curly hair. It was his habit to wash up in the barn before coming into the house.

Their brown hound, Worthless, trailed along in Joe’s wake. The dog sniffed at Jesse’s boots and then stretched out on the ground near her feet.

Joe’s glance shot between her and Jesse. His mouth hardened into a taut line. Visitors were a rarity, even former old friends.

“Hey, Jesse,” he said. His expression remained guarded as he turned to Hattie. “What’s going on? Why are you here?”

“Jesse’s an old friend, Joe. He has every right to drop by.”

“We haven’t seen you in what? Eight months? A year maybe?”

Hattie was grateful that Jesse ignored the insult.

“Yesterday we had a skirmish with a renegade band of Comanche. We rescued a handful of white captives. There’s a young woman among them who looks to be in better shape than the rest, but like most of them, she’s still unidentified. I’ve come to ask if you folks will take her in—just until her family’s located.”

Hattie watched her son’s expression darken. Without comment, he reached for the chocolate pot and filled an empty cup before he sat down at the end of the table opposite her.

“You actually expect us to take her in?” Joe’s anger was barely controlled. “Are you out of your mind?”

Jesse ignored Joe’s intent stare. “You’ve certainly got the room. Your ma could use some help around the house, I reckon.”

“Help?” Joe didn’t try to hide his disgust. “You think somebody who’s gone Comanch’ is really gonna be of help to my mother? Are you forgetting what she’s been through on account of the Comanche? You forget what she’s suffered?” Joe paused, stared at Jesse as he added, “We haven’t.”

“Please, Joe,” Hattie whispered. His undisguised bitterness and anger worried her more than the thought of inviting the Comanche captive into her home.

Joe leaned forward, rested his forearm on the table. “How long has she been a captive?”

Jesse shrugged. “No idea.”

“Did she come in of her own accord? Did she ask to be rescued?”

“I wasn’t the one who found her,” the seasoned soldier admitted. “She’s made no attempt to run.”

Joe stared down into his cup. Hattie watched the muscle in his jaw tighten before he slowly looked up again.

“Maybe you’d like us to take her in because you’re thinking of keeping all the outcasts in one place? Is that it?”

“Joe!” Hattie flushed with embarrassment.

Jesse’s expression soured. Pushed too far, he didn’t bother to hide his anger.

“You know I’m not thinking anything of the sort. Your father was one of my pa’s closest friends. I have the greatest respect for your mother.”

Hattie’s thoughts strayed to the young woman in need. A white girl who had lived among the Comanche. A girl who had been ripped from her family, taken captive and had managed to survive. Some other mother’s daughter.

Her heart again began to pound with the old fear that still terrorized her in the middle of a moonless night. She took a deep breath and refused to feed that fear, forced herself to think of the possibilities instead.

Theirs was a small spread, one that barely broke even most years. Except for spring and summer when Joe hired on extra hands, there were just the two of them. There was never time to catch up.

If nothing else, she could surely use another pair of hands. But a Comanche captive?

The Lord giveth…

“With kindness and nurturing, she’ll come around.” Hattie didn’t realize she’d voiced her thoughts aloud, but figured Joe and Jesse weren’t paying her any mind anyway.

She was a born nurturer, with nothing but cattle and crops to tend for the last eight years.

She looked up and found them both staring at her.

“I can teach her,” she decided. “And I could use a hand around the house.” She bit her lip and took a deep breath before she appealed directly to Joe.

“Jesse says no one else will take her in, son.”

“Of course they won’t. What else would you expect?” He was watching her closely, undisguised disbelief in his eyes. “Very few folks ever did anything to help you, Ma. Or have you forgotten how the good people of Glory turned their backs on you, as if daring to survive was your great sin.”

“Joe—”

“Maybe no one else has taken her in because they’re afraid she’ll murder them in their sleep.” As if a thought had just struck him, Joe looked to Jesse again. “Is she dangerous?”

“She hasn’t shown any signs.”

“Can she speak English?” Joe asked.

“She hasn’t said anything yet,” Jesse admitted.

Joe’s lip curled in disgust. “Even if she did, you don’t know what she’s thinking.”

“It’s just ’til they find her folks,” Hattie reminded him.

“Do you even know her name?” Joe pressed.

Jesse cleared his throat and shoved his empty cup aside. “The governor’s office is going through records of Indian raids and letters from folks searching for missing and abducted relations. We’ve got boxes of army files dating back to the first Texas settlers. It’s just a matter of time until we find out who she is.”

Hattie watched her son stare across the open range and studied his strong, handsome profile. Now that he was older, he reminded her so much of a young Orson that at times she almost called him by his father’s name. His black curly hair and midnight eyes came from the Ellenberg side of the family, but he’d inherited his stubborn determination from her.

Since they’d lost Orson and Mellie, Joe’s heart had hardened, even as her own had opened to forgiveness.

Now a young woman needed a home and someone to guide her out of the darkness, someone to lead her back to the light. Perhaps if the girl and Joe took the journey together, one or, hopefully, both would succeed. Would it ever be possible for Joe to forgive and move on? Would it ever be possible for him to believe again?

Hattie welcomed the chance to have another female in the house, even one that presented a great challenge. She hardly remembered what it was like to have a woman friend to confide in, to laugh with.

The laughter had gone out of their lives one bleak winter night long ago.

Jesse was waiting for an answer. She met his gaze and began to understand why he’d turned to her.

Who better to help the girl than me? Who else can even begin to understand all she’s been through?

Hattie said a small, silent prayer and looked at her son.

“I’ll abide by whatever you say, Joe, but I’d like to do this.”

Then she rose and began to busy herself with the cups and saucers. She collected the empty plate she’d filled with half a dozen almond macaroons. Jesse had eaten them all.

She had made her position clear to Joe. Now she put her trust in the Lord.

Jesse’s wooden chair squeaked under his weight and then silence settled over them all. She knew Joe was devoted to her. If he wasn’t, he’d have ridden off and left her and this place behind long ago. Spurred by sorrow, emptiness and guilt, he’d have surely chosen to follow a crooked path.

But he loved her enough to devote his life to the Rocking e. She was convinced that deep down inside, he was still a good man. He’d lost his way, that was all. She wasn’t about to lose hope of his finding it again.

She looked up and caught him watching her intently, almost as if he were trying to see into her heart. As he studied her face, she was tempted to reach up and tug on the brim of her bonnet, to try and cover the white, puckered scar that ran parallel to her forehead—the result of an attempted scalping.

Instead, she gathered her hope and courage and smiled back.

“Is this what you really want, Ma? Are you sure you can do this?” He spoke so softly she barely heard him.

Hattie was never more certain. “The Lord never gives us a burden we can’t carry, Joe.”

“Yeah? Well, He’s given you more than your fair share of hurt, Ma. You don’t have to do this.”

Oh, son, she thought. Perhaps I don’t have to, but I think you do.

When she didn’t respond, he fell into thoughtful silence. A few seconds later she saw his shoulders slowly rise and fall and heard his deep sigh of resignation. She nearly bowed her head in thanksgiving.

“If you want, I guess it won’t hurt for me to go have a look at her,” Joe said.

She knew what this was costing him. Joe avoided the town of Glory like the plague, only going in when they were in dire need of supplies. She never went at all. Not anymore.

But today she insisted, “I’m going with you, son.”

The minute the words were out, she started trembling.

“You don’t have to do that, Ma. I’ll go.”

“I don’t have to.” She nodded, wanting to be certain he knew she meant it. “I want to.”

Joe stood and put on his hat without looking at Hattie.

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you.” He turned to Jesse. “If this upsets my mother in the least, then the deal’s off.”

Chapter Three

F olks stared at Joe and Hattie, seated on their buckboard wagon as they followed Jesse down the dusty main street of Glory, Texas. The Ellenbergs stared straight ahead, ignoring the whitewashed one- and two-story houses on the edge of town.

Emmert Harroway, founder of Glory, came to Texas in 1850, determined to settle a town in the center of what would become cattle country. Along with his wife and children, his two brothers and their elderly father, Emmert had emigrated from Louisiana. He had no idea what to name the town until he reached the tracts of land he’d bought sight unseen, lifted his eyes to heaven and shouted, “Glory hallelujah! This is it!”

The name Glory took. His dream of bringing faith and commerce to the frontier was hard-won, but over the past few years, though Emmert had not survived to see Glory become a success, the small town thrived.

Joe made the mistake of glancing over at the row of shops and stores and saw Harrison Barker, owner of the Mercantile and Dry Goods, pause in the midst of sweeping off the boardwalk out front. The man didn’t even bother to close his jaw as the Ellenbergs passed by.

Joe didn’t have to see them to feel other similar stares. The shame that ate away at him morning, noon and night intensified whenever he came to town. No one had ever thrown what had happened to his family in his face, but it was easy to discern their silent condemnation. With his mother riding beside him, their curiosity was just as palpable.

They passed the train depot, the clapboard-sided buildings that housed a butcher shop, a brand-new two-story boardinghouse. An empty law office now housed a U.S. Army annex under Jesse’s command.

The whitewashed church flanked by the church hall fronted a dusty town square and park at the far end of Main Street. Joe pulled the wagon up in the open yard in front of the hall where a crowd had gathered. Seeing so many of the “good” folk of Glory standing together made him break out in a cold sweat.

As was the way of small towns, news traveled fast. Word of the captives’ recovery had spread from household to household and now the curious waited like scavengers, hoping to get a glimpse of the forsaken souls who’d been abducted by their fearsome enemies and forced into unspeakable degradation and servitude.

Joe hated adding to the circus.

Beside him, his mother smoothed her hands along the folds of her brown serge skirt. He saw her grasp the cord on her paisley reticule, twist and hold on so tight that her knuckles whitened. He rarely saw her rattled and knew it was the unknown, as much as the knot of townsfolk, that provoked her nerves.

They would soon be face-to-face with what the others so desperately wanted to see.

He reminded himself that he was here for his mother, not to worry about what folks thought about him. He’d done little enough to make his ma’s life easier these past few years. Her courage and faith both astounded and confused him. She had every reason to hate God and yet she didn’t.

His mother continuously gave and never asked for anything.

If taking in a captive was something she wanted, if trying to help the girl might help his mother in any way at all, then far be it from him to deny her. He’d give his right arm to make up for what had happened, but she wanted more from him than he was able to give.

She wanted him to forgive and forget and move on—but theirs was a hard life before the raid and it had been near impossible after.

He couldn’t bring himself to believe or trust in a God that dealt such a heavy hand to the innocent.

Seeing his mother clutch her purse strings, it took all the will he could muster not to turn the team in the direction of the ranch and take her home.

Jaw clenched tight, Joe climbed down off the wagon seat and reached up to help her to the ground.

“You all right, Ma?” He stared up into her eyes. Most of her face and all of her hair was conveniently hidden from the crowd by the wide brim of her poke bonnet.

“I’m fine, son.” She shook the folds out of her skirt and smiled tremulously. Her eyes were hazel, clear and shining. All the color had drained from her face except where her cheeks were stained by two bright red spots of embarrassment.

He thought of the way she used to smile, the way she’d flush with excitement over the smallest things—going into town for Sunday service, chatting with friends at a social, baking something special for the Quilters Society Meeting.

Despite her scar, at forty-five she was still a handsome woman. Just now he was proud as she held her head high and started toward the double doors of the church hall.

Joe looped the lines over a hitching post and hurried to catch up. Ignoring the stares and murmurs of the assembly, he caught up to Hattie and offered her his arm, not only a sign of the good manners she’d instilled in him, but as a way to ignore the crowd.

No one spoke a word in greeting. When Jesse joined them and they crossed the porch, those gathered near the doors parted to let them pass. He kept his eyes on the double doors to the hall. The window shades were pulled down tight, obscuring the view inside. Two uniformed soldiers stood on each side of the doors like bookends. They saluted as Jesse approached.

Without hesitation, Jesse opened the door just wide enough for the three of them to enter before he quickly drew it closed behind them.

Joe felt his mother’s fingers tighten around his elbow the moment the door clicked shut. She seemed to sway and leaned into him, startling him. He’d never seen her swoon before and her reaction frightened him.

“We’re leaving,” he told Jesse, his focus centered on Hattie, on her welfare. The close air in the room smelled of charred wood and fear. Dirt and sweat and blood. He tasted his own fear when a low, mournful wail permeated with hopelessness issued from the far corner.

Beside him, his mother drew herself up, straightened her spine and let go of his arm.

“I’m perfectly fine. We are not leaving,” she said.

“You sure you’re all right?” He saw only the gathered edge of her poke bonnet.

“I’m fine, ” she whispered, turning to face him full on.

His mother had never lied in her life—before now. Her skin was the color of her Sunday-best white linen tablecloth. Her eyes were wide and terrified—of either the past or what she was afraid she’d see before her. He couldn’t tell. But he did know she was far from fine.

“Over here.” Jesse stewarded them across the room toward the opposite corner, moving swiftly, as if worried Joe would make good on his threat to leave.

They stopped before four filthy women huddled together on the floor, their backs against the wall. It wasn’t until they were nearly upon them that Joe realized the women were bound together, hand to hand, foot to foot.

Except that the oldest had muddy blond hair, they bore no resemblance to white women at all. Dressed in fringed deerskin gowns, their hair parted and plaited into long braids, there was nothing about them that indicated they were anything but Comanche.

Who had they been?

Who were they now?

“So many,” Hattie whispered.

Joe knew she believed no one was ever beyond redemption, but this? These women had been carried off into another world, a savage, brutal world. Was there anything left of their former selves to be saved?

Jesse stared down at the unfortunate women. “If female captives aren’t made slaves or adopted into the clan, they’re sold and traded many times over.”

None of the former captives made eye contact with Joe, Hattie or the captain, nor did they look at one another as they sat shoulder to shoulder, each imprisoned in her own misery.

The oldest, the blonde, rocked back and forth with her eyes closed, a strange, demented smile on her face. Her fingers picked endlessly at her skirt.

Ceaseless moaning came from a heavyset woman beside her with sun-damaged, puffy cheeks and matted, reddish-brown hair. The tip of her nose was missing. She stared across the room with unseeing eyes, her face slack and devoid of expression. Whatever haunted her now was trapped in her mind and not this room.

A girl of around twelve years slowly looked up at them. Joe’s breath caught when he noticed all the fingers of her left hand were missing and had been for some time. The stumps were healed over, her skin tanned to a golden brown. He tried not to stare and failed miserably.

When their gazes met, the child’s lips curled. She bared her teeth like a feral animal.

“She’s from outside Burnet. Taken two years ago. Her parents are on the way to get her,” Jesse explained.

“What if they don’t want her?” Joe wondered aloud.

“She’s someone’s girl, Joe,” Hattie said with assurance. “Their baby. If you were a father you’d know. They’ll still want her.”

He doubted he’d ever be a father. Doubted he had the strength it would take to confront what this battered child’s parents would be facing. Doubted he could accept such a burden. Hattie was speaking with a mother’s heart. For years now he’d been certain he didn’t even have a heart anymore.

“The girl we intend for you to take is over here.” Jesse’s words reminded Joe of why they’d come. Staring at the maimed, feral child, he knew giving in to his mother’s request had been a big mistake.

Jesse led them over to a boy tied beside yet another young woman. About ten years old, with a head full of white-blond hair, the male child cried without making a sound. Tears streaked his face and dripped down his chin. He was near naked, wearing only a rawhide breechcloth and well-worn moccasins.

Beside him, a trim young woman in a fringed and beaded tanned deerskin skirt and shirt matted with dried blood sat with her head hanging down, her hands clenched in her lap. Intricately beaded moccasins covered her feet.

“That’s her,” Jesse said.

“The slender one?” Hattie asked. “Why, she’s no bigger than a minute.”

Joe glanced away from her bare, shapely ankles and calves and focused on her bound wrists and clenched hands. She appeared to be anywhere from her late teens to early twenties and from where he stood, she could pass for full Comanche. Her skin was a golden, nut-brown. Her arms looked strong and firm, as if she was used to heavy work. Her hair was dark brown, but upon closer inspection, he saw it was shot through with reddish-gold highlights.

He tried to imagine taking her back to the ranch, settling her into his sister’s room.

Turning his back on her.

What is my mother thinking?

“How do you know she’s not a half-breed?” he wondered aloud.

Jesse hunkered down into a squat, gently put his hand beneath the girl’s chin. She didn’t resist or try to pull away as he forced her head up.

When she stubbornly kept her eyelids shuttered, Jesse commanded, “Look up.”

Slowly, the young woman raised her thick, silky lashes and insolently stared back at Jesse. Her focus drifted away from him and locked on Hattie. She sat there in silence, staring at Joe’s mother for a few long, curious heartbeats. Finally, she turned her gaze on Joe.

It struck him that her eyes were the purest, most radiant blue he’d ever seen—the color of a mountain lake in the morning sun, the sky on a crystal-clear day. And those unusual, incredible eyes were filled with both the deepest of sorrows and more than a hint of unspoken hatred.

A chill rippled down his spine and in that instant he felt he was looking into the cracked mirror he used for shaving.

The girl’s eyes were not the same color as his own, but they certainly reflected all the hurt and misery he’d seen and suffered since the night the Comanche raided the ranch.

The night he hadn’t been there to fight and die beside his father and his sister. The night he hadn’t been there to save his mother.

The night he’d never forgive himself for.

Chapter Four

T he whites towered over Eyes-of-the-Sky where she sat on the floor, her head down, her eyes dry, her body nothing more than a hollow shell. Her body might be here, in this dim, vast lodge of wood that echoed with the voices and heavy footsteps of the whites, but her spirit had flown.

Above her, they spoke in hushed tones. Straining to shut out the garbled foreign sounds without covering her ears, she willed herself to sit completely still, to become as invisible as the breeze that threaded itself through the tall prairie grasses.

One of the men squatted before her, took her by the chin and forced her to look up.

The dreaded soldiers had been doing that all day. One after another. Making her look them in the eyes, each time stealing more of her spirit, more of her will.

Each reacted differently. Some frowned and shook their heads, clearly disapproving. Others showed surprise, their own eyes growing wide with shock when they met hers.

Without trying, she’d learned one cursed white word over the past few hours.

B’loo.

Whenever they looked into her eyes, they said, “B’loo.”

Now three new ones stood over her. An older woman whose pale face remarkably turned even whiter beneath the red splotches on her cheeks when Eyes-of-the-Sky looked at her. The white woman wore a headpiece that almost hid a long, jagged line of shining, puckered skin—a scalping scar.

Eyes-of-the-Sky forced herself not to study the woman’s head covering, for the sight of it disturbed her almost as much as the scar. She looked straight into the woman’s eyes until she saw the one thing in them that reignited her anger.

Pity.

The woman was sorry for her, for Eyes-of-the-Sky.

She didn’t want the scarred woman’s sorrow or her pity. She didn’t need these people to pity her. She was Eyes-of-the-Sky, daughter of Gentle Rain and Roaming Wolf. A daughter of the Nermernuh. Beloved of White Painted Shield.

She turned away from the woman’s pity to look up at the young white man beside the woman. The only likeness they shared was the determined cut of their jaws. Eyes-of-the-Sky knew that these two would be fierce enemies or loyal friends. She could tell by the set of the younger man’s shoulders, the way he stared back, challenging her, daring her to look away, that he possessed the heart of a warrior.

He was not a man to anger or to betray.

She tried to drop her gaze and failed. There was something in his eyes that compelled her to stare back. It wasn’t long before she realized what force attracted her to him.

His spirit, too, had flown. Inside, he was as empty as she.

As if locked in a silent battle of wills with the dark-eyed young man, Eyes-of-the-Sky knew a moment of panic. For the first time in two days, the emptiness, the numbness she’d suffered abated.

She shivered, wondered what this man wanted from her. Why would this scarred woman walk into a room of captives and soldiers?

What had these two to do with her?

Joe’s gut tightened until it hardened into an aching knot as he stared into the eyes of the white woman turned Comanche.

He couldn’t seem to break the spell until he heard his mother say, “Untie her, Jesse, please. No one deserves this kind of treatment. No one.”

Beside her, Joe shifted uncomfortably. If not for his mother, he’d be hightailing it out of here, leaving the girl behind, fighting to shut out the memory of the penetrating blue-eyed stare that would haunt him for a long time to come.

“Ma, they’re bound for a reason. Leave it alone.”

“Look at her, Joe. Look at all of them. These are God’s creatures. These poor souls deserve better.” Hattie turned her ire on Jesse. “I can’t believe you keep them fettered like this, sitting in their own filth, after all they’ve been through. We treat our stock better.”

“The women can be as fierce as the men, Hattie. There’s still no telling what they might do to us or themselves,” Jesse grudgingly admitted.

Joe shoved his hand through his dark hair. “Yet you want us to take her into our home.”

“Untie her,” Hattie demanded. Before Joe knew what she was doing, his mother knelt down before the girl and laid her hand over the young woman’s chaffed, bound wrists.

“We’re taking you out of here, honey. We’re taking you home with us. It’s not a grand place, but we make do.” She spoke softly, kept her voice evenly modulated, the way she did when calming an injured animal. “We’re going to get you cleaned up and feeling fine in no time.”

“Fine? You really think so, Ma?” Joe didn’t try to hide his bitterness or his skepticism.

Hattie slowly rose and faced him. She lowered her voice so that only he, and perhaps Jesse, could hear.

“I know you blame yourself for what happened to me and the others, Joe, but there’s a time to mourn, a time to weep, and then there is a time to give your trials over to God and let them go. ”

No one knew that better than she did.

“I believe with our help and God’s love, she’ll be fine.” She squared her shoulders, ready for a fight. “She needs time and care. She may never be the same person she was before she was taken, but eventually, she’ll be better. God willing, I’m going to try to help her get there. You can either help me or not, that’s up to you, but if you can’t help, then the least you can do is try not to hinder. I insist that you be civil toward her.”

Joe glanced around, noticed all of Jesse’s men were trying to listen. Except for the low, pitiful moan from the demented captive woman, there wasn’t another sound in the room.

Jesse cleared his throat and slipped a deadly-looking hunting knife out of a sheath hooked to his belt. He bent down, cut the cord binding the girl’s feet and, taking hold of her elbow, pulled her up. She wavered and staggered slightly. Joe reacted without thought and grabbed her upper arm to steady her.

At nearly the same time, both of them realized what had happened. The girl shook off his hand just as he let go and took a step back.

“Keep her hands bound until you get to the ranch,” Jesse suggested to Joe, ignoring Hattie.

Being ignored by both men only raised her ire.

“Free her hands, too,” she ordered.

The two men exchanged a look. Hattie gently put her own hand around the girl’s upper arm. This time the girl didn’t shy away.

“Please, Jesse,” Hattie added. “Cut her loose. There’s no way she can outrun Joe.”

Joe held his breath as Jesse slipped his bowie knife beneath the thick rope binding the girl’s wrists. As the rough hemp fell away, he saw her skin beneath was raw, broken and bleeding.

His mother was right. They would never have treated their own stock this badly.

But then he reminded himself that rescued captives weren’t valuable stock. They may have been white at one time, but they’d been taken by the Texans’ worst enemies. They’d gone Comanch’.

And now, thanks to his mother, he was taking one of them home.

Hattie led the way, guiding the silent young woman along beside her. Joe hurried to catch up with them. He held the hall door open for them to pass, steeled himself to face the folks gathered outside. He didn’t notice just how close he was to the girl until the fringe on her sleeves brushed against his pant leg.

As he expected, a hush fell over the crowd as soon as his mother and the captive girl stepped outside. He shut the door a little too hard behind them, and the young woman visibly started. Her huge eyes went wide, but she recovered quickly, shooting a cold glare in his direction.

“Sorry,” he mumbled.

If she understood, she gave no sign.

She stared at her toes as they headed across the wide covered porch outside the hall and stepped out into the sunlight. The day was heating up. As Joe shoved his hat on his head, he was tempted to run his finger around the neck of his shirt, to pull the fabric away from his overly warm skin.

As before, no one in the crowd made any attempt to speak to them, but when they reached the buckboard, he noticed a tall, cultured-looking man approaching from the direction of the church. There was a calm, assured confidence about the stranger as his long, even stride ate up the distance between them.

Joe motioned to the girl that she should step onto the wheel and into the wagon. She did so gracefully and without hesitation. He wondered at her easy acquiescence, then figured that she relished being unbound and removed from the hideous scene and stench inside the hall and didn’t want to risk being returned because of rebellion.

The fringed hem of her doeskin dress hiked up to reveal her calves and ankles as she climbed aboard the wagon. When Joe caught himself staring at her bare legs, he quickly looked away.

His mother waited patiently beside him, ready to climb onto the seat next to the girl. But as Joe took Hattie’s hand, the newcomer walked up and introduced himself.

“I’m Reverend Brand McCormick, the new minister here in Glory. Captain Dye told me that you’ve offered to take one of the rescued captives into your home.” He glanced up at the girl seated in the wagon. Unmoving, she stared straight ahead, her fingers knotted together in her lap. If her injured wrists hurt at all, she gave no sign.

Joe reckoned the fact that the minister was new to Glory explained why he was so cordial. Jesse obviously hadn’t told the man everything about Hattie Ellenberg.

When the preacher offered his hand in greeting, Joe stared at it before finally accepting.

“I’m Joe Ellenberg. And this is my mother, Hattie.”

Hattie turned to face the new preacher squarely. Reverend McCormick didn’t react. He merely nodded and smiled.

“Mrs. Ellenberg. It’s good to finally meet you. I hope you’ll join us for Sunday services soon.”

Hattie didn’t immediately respond, and Joe realized she was shocked speechless by the minister’s invitation.

“The last minister made it clear my mother wasn’t welcome among the good folks of Glory anymore,” Joe informed him coolly.

Hattie lightly touched Joe’s arm. “Not today, Joe,” she whispered. “Let it go.”

Reverend McCormick’s smile dimmed but quickly returned. He slowly nodded in understanding.

“I’m not the old minister, Mrs. Ellenberg. Everyone is welcome to attend services. We hope you’ll join us.”

As the man talked softly to Hattie, assuring her that the doors of his church were always open to her, Joe glanced up at the girl on the high-sprung buckboard seat. She remained stiff as a poker, her back ramrod straight as she stared off into the distance. Her profile was elegantly cut, her features delicate, her lips full.

He couldn’t help but wonder what she was thinking. She certainly showed no elation at having been rescued. She showed no emotion whatsoever.

There was an aloofness, an intense pride in the way she continued to ignore them all and stare out at the gently rolling plain beyond the edge of town. Something stubborn and determined and silent that convinced Joe she was not to be trusted.

Chapter Five

J oe no more knew what the girl was thinking when they reached the ranch than when she’d stepped into the wagon, but he’d been aware of her presence all the way home.

How could he not? What with her sitting there all stiff and silent beside him, her shoulder occasionally bumping against his, his shirtsleeve brushing her bare arm with every sway and bounce of the buckboard.

Having her wedged between him and Hattie, the miles along the rough, dry road seemed endless. His mind was so burdened with worry over what might happen while she was living beneath their roof that it was all he could do to keep the wagon wheels in the well-worn ruts.

Relieved when he finally guided the horses through the main gate of the Rocking e, he pulled up near the front of the house, set the brake and tied the reins.

Though the girl never reacted, his mother had prattled on and on throughout the entire trip home. She’d commented on the budding spring wildflowers, the roads that cut across the open plain toward other ranches and homesteads, the need for rain. She chatted without encouragement or response.

His mother’s enthusiasm was unsettling. Joe couldn’t remember the last time he’s seen her so pleased. For her sake, he hoped she hadn’t just brought another round of endless heartache home.

He nudged the girl to draw her attention. She jumped when his elbow connected with her arm and turned wide, startled eyes his way.

Their gazes locked. Wariness and suspicion crackled between them, nearly as visible as lightning.

“Help her down, Joe.” Hattie seemed anxious to get the girl inside.

He climbed down and offered his hand. When the girl ignored him and climbed down unaided, he felt a tug of relief deep in his gut. Without knowing why, he was thankful for not having to touch her.

Hattie came around the wagon, gently took the girl by the arm. The hound, asleep on the porch, must have sensed movement, for he roused himself and got up to greet them. He was a few yards away when he got a whiff of the newcomer, whimpered and ran around to the back of the house.

The mutt had been worthless before the raid—which was how he got his name—but since then, he’d been deaf as a post and blind in one eye.

Hattie looked to Joe. “What’s got into him, I wonder?”

“Caught the scent of Comanche.” He purposely avoided looking at the girl.

“After you unhitch the wagon, would you set some water on to boil for me, Joe? I want to get her cleaned up first thing.”

Her words brought him up short. Practical and efficient, his mother would naturally want to jump right in and scrub the girl down. That meant extra work for her. Not to mention extra work for him that he didn’t need.

“What if she doesn’t want to bathe?” He looked the girl over from head to toe, taking in her matted hair, her bloody clothes.

Hattie gave him a look he knew all too well. She wasn’t going to budge or argue. She lowered her voice but lifted her chin. Her eyes were shadowed with remembrance.

“She’ll be willing to shed these bloody things. She won’t want to be reminded of what happened to her yesterday. And she will bathe.”

Joe noted the girl’s rigid stance and squared shoulders. Her posture would do a queen proud. Perhaps his mother was wrong. Maybe the girl wore her bloodstained clothes proudly, like a badge of honor.

“The horses and water can wait,” he said. “I’m going inside with you.” He wasn’t ready to walk away and leave his mother alone with her charge yet.

The girl had her back to him and was staring at the house. He tried to see it through her eyes—the two low structures connected by a single roof that covered the dogtrot between the kitchen building and the main house. Constructed of hand-hewn logs, the cracks chinked with sticks and clay, the buildings hugged the earth and blended into the landscape.

Stick-and-clay chimneys extended from the roofline in both the kitchen and main buildings. The clapboard roof still showed signs of smoke damage in one or two places where it had started to catch fire during the Comanche raid. Spots that were low enough for Joe to have been able to extinguish the fire before it took hold.

Hattie held on to the girl’s elbow, leaning closer until their heads were nearly together.

“Come on, honey,” she said. “I’m going to have you cleaned up in no time.”

“She’s not a child, Ma.”

“I know that, but I want her to understand that I don’t intend to hurt her.”

He followed them inside, but Hattie paused just inside the door and sighed.

“You can’t set aside your work to watch her every minute, son. You’ve already lost a good half a day. I can hold my own against one skinny little gal.”

He ignored her comment and lingered until Hattie handed the girl a glass of water and encouraged her to drink. His mother bustled out onto the back porch where she kept the tin bathtub and dragged it to the back door. When he saw what she was doing, Joe carried it the rest of the way into the kitchen while the girl ignored them both and stared out the open door as if she were there alone.

Hattie left for a moment and came back with an armload of folded towels.

“It’s gonna be impossible to get this child bathed without that hot water,” she told him. “Look at her, Joe. She’s dead tired. She’s too exhausted to try anything. Go on now. Fetch me some hot water.”

He shot a glance in the girl’s direction. She was, indeed, practically weaving on her feet.

“’Sides,” Hattie started in again, “we’re miles from anywhere. You’ll track her down in no time if she takes off. She knows that as sure as you do.”

He got himself some water, drank it and hesitated by the door. What if the girl was feigning exhaustion? Waiting for just the right minute to overpower his mother and run?

But Hattie was right. There was nowhere to run and nowhere to hide.

Hattie planted her hands on her hips. “Either you go get the water or I’ll do it…and leave you to get her undressed.”

Without another word, he turned on his heel and stalked out.

They argue over me.

Eyes-of-the-Sky knew it not only by the hardness in the man’s voice, but the coldness in his eyes that gave his anger away.

Whatever the woman just said had shamed him in some way. Shamed him so that he walked away without looking at either of them again.

After he left, the older woman laughed softly and shook her head. The words that followed her laughter were as unintelligible as all white man’s words were to Eyes-of-the-Sky.

She was led into a smaller room lined with wooden boards filled with stored food. Through gestures and gibberish, the woman soon convinced her to take off her garments.

Eyes-of-the-Sky fought to keep her hands from trembling as she touched the front of the once soft doeskin now stiff with the blood of little Strong Teeth.

The woman knelt before her, touched her knee and then her ankle, urging her to lift her foot, then she gently slipped each of her beaded moccasins off for her.

The simple gesture was so gentle and unexpected that it inspired tears—tears that Eyes-of-the-Sky refused to let fall.

Though the woman seemed kind enough, Eyes-of-the-Sky dared not show weakness. The white woman’s tenderness was surely some kind of trick meant to lull her into complacency.

Though Eyes-of-the-Sky refused to remove her garments, the woman soon made it clear she was to undress or they would stand there facing each other in the close confines of the little room forever. Wary and wondering where the man had gone to, Eyes-of-the-Sky looked around.

With words and more gestures, the woman let her know the man was gone. Then the woman covered her eyes with her hands and said something that sounded like “Hewonlook.”

Finally, as Eyes-of-the-Sky slipped off her clothing, the woman quickly drew a huge striped blanket around her, covering her from shoulders to knees.

Eyes-of-the-Sky heard the sound of the man’s heavy footsteps coming and going outside the door. Suddenly, the woman stopped talking, gathered the soiled doeskin dress and moccasins, and stepped out, quickly shutting her inside the small room full of supplies.

With her ear pressed to the door, she heard the man and woman whispering together and wondered what they were planning. Her heart raced with fear for she had no idea what to expect. She knew nothing of their ways.

When they brought her here, trapped between them on the high seat of the rolling wagon, they’d bounced along in a way that made her already warring stomach even more upset.

She was shamed because she wasn’t strong enough to fight them. She no longer had the will or the stamina. But her strength would recover. She was determined to escape, to go back to her people. To return.

To what?

The question came to her from the darkness in her heart. Go back to what? When the Blue Coats had led her away from the encampment, she’d seen only death and destruction. She’d heard the cries of the wounded and the ensuing gunshots that stilled their cries. The silence was more deafening than the screams.

Suddenly he was walking around in the room beyond the door again. She heard heavy footfalls, heard the splash of water. Then the sound of his heavy boots against the wooden floor ebbed away.

When the door opened again, Eyes-of-the-Sky jumped back, clutching the blanket to her. Only the woman remained on the other side of the door.

“Comeoutnow,” she said, gesturing for Eyes-of-the-Sky to follow her into the larger room.

Clutching the cloth around herself, she crept forward, let her gaze sweep the room. The man was nowhere.

The large metal container was full of water that was so hot steam rose from its surface.

I am to be boiled alive.

Clutching the blanket, she backed away, bumped into something wooden and she winced.

The woman took her forearm and, gently patting her, spoke in the kind of lilting tone Eyes-of-the-Sky had once used to cajole her little brother into doing things he was afraid of doing.

The woman left her side long enough to walk over to the huge container of water, to scoop warm water to her face and neck and wash herself.

“Comeon.” The woman encouraged. She gestured to the water again. “ Come. Here.

“Come.” She wants me to walk to her.

The clear, steaming water was so tempting. Eyes-of-the-Sky moved closer, watched the woman with every step that brought them together. She clung to the blanket with one hand, slowly touched the surface of the water with the other.

She looked into the woman’s scarred face, saw her nod her head. Then the woman turned her back.

Eyes-of-the-Sky quickly glanced around the room. There was no way out, no weapon within reach. She knew the man was waiting somewhere outside, waiting for her to try to escape.

She looked down into the warm, inviting water, saw her reflection there. Her hair was matted with dirt and ash. Her skin was streaked with sweat and blood. The smell of death and destruction filled her head.

She glanced over at the woman again, dropped the blanket, then slipped into the warm water.

After Joe left them alone, he headed for the barn, nearly running until he reached the watering trough. Without hesitation, he dunked his head under the surface of the cold water.

Standing there with his wet hair dripping down around his ears and soaking the front of his shirt, he knew that if he was still a praying man, he’d ask the Lord to let Jesse find the girl’s family. And find them fast.

In an attempt to settle back into his routine, he unhitched the horses, turned them into the corral and had just picked up a shovel to muck out the stalls when he heard Hattie call to him from the porch.

He dropped the shovel and hurried outside, slowed his rush when he saw her with the girl’s discarded clothing in her arms.

He went back to the house and when he got there, Hattie explained.

“She fell sound asleep in the warm water. Thought we might as well get rid of these,” she said, looking askance at the pile of stained hide clothing, the beaded moccasins.

He held out his arms and she dumped the Comanche clothes into them. Lice ridden, no doubt. Reminders of exactly who the girl was now and where she’d come from that were every bit as sobering as his dunk in cold water.

“I’ll take care of them,” he promised. Gladly.

“I’d better get inside and make sure she hasn’t drowned in there.” Hattie glanced back at the kitchen door.

He headed for the barn again, concentrating on the buckskins in his arms instead of the young woman asleep in the tub.

The hides were soft where they weren’t bloodstained, the beadwork intricate and colorful. Small shells and fringe also decorated the long shirt. Collectors back East paid a pretty penny for Indian gewgaws like this, but bloodstains had no doubt ruined any value they once possessed. The best thing to do would be to burn them.

He carried the clothes to the downwind side of the barn where he burned rubbish and stoked the fire he’d built to heat the water.

He went back into the barn and mucked out another stall while the fire took hold. When it was hot enough, he picked up the girl’s things and tossed them on the open flames.

A second later, a heart-stopping cry rang out behind him, one that sent a chill down his spine. The back door banged. He spun around, ready to sprint toward the house.

That’s when he saw the girl, a blur in yellow taffeta, flying across the open yard.

Barefoot, her long hair damp and streaming free, she sprinted toward him, shouting words he couldn’t understand. He tried to grab her as she barreled past but she lithely sidestepped him. Without pause, she stood perilously close to the fire and reached into the flames.

He gave a shout, lunged and caught her around the waist, then pulled her back.

She’d managed to tug the hem of the doeskin shirt out of the fire. The piece was still smoldering in her hands.

He let go of her and slapped the Comanche garb to the ground, then pushed her back, away from the smoldering garment that threatened to catch the hem of her gown on fire.

Stomping on the burning doeskin, he managed to extinguish the flames, but the shirt, as well as the pieces still burning on the fire, was ruined.

“Are you crazy?” He turned on the girl. The thin tether that had held his emotion in check since they’d walked into the church hall finally snapped. Now, though she was but a foot away, he shouted at her.

“You could have burned yourself up just now!”

She yelled right back. He might not be able to understand what she said, but the way she spit out the words was clear enough—she was swearing at him in Comanche.

He grabbed her hand, anxious to drag her back to the house and turn her over to Hattie, but when his palm connected with hers, she cried out. Not in anger, but in pain.

Instantly, he shifted his hold to her wrist.

She turned her hands palms up, staring at them in silent shock. Her skin was marred by red, angry burns.

Joe’s anger fizzled away on a sigh. He let go of her wrists.

She stood before him, head bowed. Her long damp hair hid her expression like a chestnut veil. Her bare toes, coated with dust, peeked from beneath the hem of the taffeta gown.

No longer were her shoulders stiff with pride. No longer did her ice-blue eyes blaze up at him full of stubborn determination.

The ruination of her things had left her defeated, limp and lifeless as the scorched and smoldering garment at their feet.

Hattie ran out to join them, her eyes full of worry, her hair limp from the steaming warmth of the kitchen. She’d taken off her bonnet and, as she did when they were home alone, tried to comb some of her hair over her scar.

“What happened?” Her focus dropped to the girl’s reddened palms. “What have you done?”

“Are you accusing me or asking her? If you’re asking her, you might as well be talking to a fence post, Ma.”

“I’m not accusing you.”

“She grabbed her Comanch’ dress out of the fire, is what happened. Grabbed it after it started to burn and scorched her hands.”

Hattie cupped her hands beneath the girl’s and inspected the wounds. “Thank heaven, these burns aren’t very deep. They surely must hurt something fierce.”

She reached up and tucked a lock of the girl’s hair behind her ear.

“She ran out the back door fast as lightning.”

Joe heard admiration in his mother’s voice, noted the gentle, caring way Hattie dealt with her. She’d dressed the girl in the yellow taffeta, a gown he’d never seen her in, but one he knew Hattie wore when she was young and wealthy and living back East.

A dress she’d owned long before she’d married his father.

She’d been saving it for Mellie to wear when she was grown. But now Mellie was gone.

His already hardened heart hated seeing this stranger wearing it.

“She looks ridiculous, Ma. We can’t have her running around the place in a ball gown.”

“She’ll have to wear it until I can make over one of mine for her. As it is, my clothes are way too big for her. I think she looks just fine.”

“It’s a party dress, Ma, and this is no party.”

“She doesn’t know the difference, Joe. Might as well use it.” Hattie fluffed a ruffle on the sleeve of the gown. “She looks real pretty.”

She looked, Joe was forced to admit grudgingly, almost beautiful.

“Don’t forget she’s not staying, Ma.” For a minute he wondered if he wasn’t reminding himself.

“What are you saying, Joe?”

“I’m just saying don’t get attached. She burned herself trying to save those Comanche things. No matter what you’d like to believe, she’s not one of us. I’m telling you she’ll turn on us as soon as she gets half a chance.”

The girl was watching him very closely, as if straining to understand.

He flicked his gaze away, willing himself to look anywhere but into her eyes. There was no way he’d let himself grow soft toward her. No way he’d drop his guard. He wasn’t about to start thinking of her as anything but what she was—the enemy.

“Where’ve you gone, Joe? Where has your faith and the love in your heart gone?”

Hattie’s whispered words were barely discernible, and yet he’d heard them, just as he heard the sorrow laced through them. His mother was looking at him as if she didn’t really know him at all.

She already knew the answer as well as he did.

Where was his faith? What had happened to the love in his heart?

“The Comanches took them,” he told her.

Hattie surprised him by giving a slight shake of her head.

“No, son. You and I both know your faith faltered long before the Comanche attack. What I’ll never understand is why. ”

Without waiting for an explanation, she turned to lead the girl back to the house and left him standing alone with his guilt, his doubt and his suspicions.

He knew that no matter how much he wanted to blame the Comanche, his mother was right.

He’d lost his faith long before that dark and terrible night.

Somehow they got through supper.

Before she pulled a meal together, Hattie treated the girl’s burns with a poultice of raw potato scraped fine and mixed with sweet oil. Then she bound them with clean strips of cotton from the scrap basket she kept for quilting.

The former captive sat in silence with her burned hands resting in her lap. She watched Hattie work, either out of curiosity or sullenness, Hattie couldn’t tell which.

Though the girl never once reacted, Hattie explained what she was doing every step of the way and kept up her stream of chatter, hoping that something she said or did might trigger the girl’s memory.

She rang the dinner bell and called Joe in from the corral where he was working with a new foal. He walked into the kitchen and ignored the girl, but Hattie felt undeniable tension in the room from the minute he crossed the threshold.

As she drained boiled potatoes, she offered up a silent prayer, asking the good Lord for guidance in dealing with the girl and patience toward her headstrong son.

When supper was laid out, she sat the girl opposite Joe even though it was easy to see the two young people were determined not to look at each other.

The girl stared down at the layered beef and mashed potato bake on her plate.

“Join hands and we’ll give thanks for God’s blessing.” Hattie reached for Joe’s hand and for the girl’s bandaged hand, careful to touch only her fingertips.

“Take her other hand, Joe, and close the circle.”

“She’s a heathen, Ma. She’s got no idea what you’re doing.”

“By some accounts you’re a heathen, too, son, but you still bow your head as I pray over our meals. So can she.” Hattie waited.

Grudgingly, Joe reached across the table. When the girl hid her free hand under the table out of his reach, Joe shrugged.

“Guess she’s doesn’t want to touch me any more than I want to touch her.”

“Bow your head, then.” Hattie motioned to the girl, who watched Joe bow his head. Though the girl didn’t oblige, Hattie began anyway.

“Lord, thank you for this food. For this day. For bringing this child into our lives. Let her grow in understanding. Let her come to know You and Your mercy and wonder. Reunite her with the family that surely loves and misses her. Amen.”

Joe waited until Hattie took her first bite before he dug in. The girl watched them for a few seconds more, then, ignoring the flatware beside her plate, she grabbed a piece of beef with both hands, wiped off the potatoes and shoved it in her mouth.

Hattie was shocked into silence. Joe almost laughed.

“Ma, I believe this is the first time I’ve ever seen you speechless.”

The girl was quickly shoveling pieces of meat into her mouth with both hands, her bandages hopelessly soiled.

Hattie rolled her eyes heavenward and finally admitted, “This may be more of a challenge than I’d bargained for.”

You got yourself into this.

Joe was tempted to say I told you so as they watched the girl shove food into her mouth. By some miracle, she didn’t spill any on the front of her dress. Much to Joe’s amazement, his mother allowed the girl to eat without trying to cajole her into using utensils.

“She’s been through enough for one day. Morning will be soon enough to work on using silverware,” Hattie explained.

Darkness fell before supper was cleared and the dishes were done. When Joe came in from bedding down the stock and making the rounds, securing the gate and checking the boundaries of the yard, he found his mother and the girl seated in the front room of the main house. Hattie formally called it the parlor.

A mellow glow from the oil lamps cast halos of light around the room. The walls appeared to close around them as shadows wavered on the flickering lamplight.

Hattie was seated in her rocker with her Bible open on her lap. It was her habit to read from the Good Book at the beginning and end of every day, always starting where she’d left off. He had no idea how many times she must have read the entire Bible straight through.

She never missed a day, not even when times were at their lowest ebb and things seemed hopeless.

The girl was seated across the room on the upholstered settee, one of the only pieces of furniture that the Ellenbergs had brought with them when they immigrated to Texas. Elegant and finely crafted, it was as foreign to the rough interior walls of the log home as the girl seated on it.

Hattie had braided the girl’s long hair in two thick skeins that draped over her shoulders. The creamy yellow of the shiny taffeta gown complemented the tawny glow of her skin. Every so often, her eyes would close and Joe couldn’t help but notice how long and full her eyelashes were when they brushed her cheeks.

Hattie had taken time to change the bandages that hadn’t survived supper. Barefoot for lack of any shoes that fit, the girl sat pressed against the arm of the settee, cradling her wounded hands in her lap. Dozing off and on, she was the picture of peace and contentment.

If Joe hadn’t known who she was and where she’d been found, he might have taken her for a rancher’s daughter, a shopkeeper’s wife, a Texas plainswoman.

But he knew who she was and he knew better than to take her at face value. Though she looked innocent enough, until she proved herself, which he was convinced would be never, she was not to be trusted.

Not even when the sight of her or the thought of her plight threatened to soften his heart.

Suddenly dog tired and sick of worry, Joe settled into a comfortable side chair and soon began to doze, slipping in and out of consciousness as Hattie read—

“‘On that day Deborah and Barak son of Abinoam sang this song:’”

Joe shifted, fought sleep until he glanced over at the girl. Her eyes were closed. She hadn’t moved.

“‘Village life in Israel ceased, ceased until I, Deborah, arose, arose a mother in Israel.’”

His mother’s voice lulled and soothed him. He remembered her reading to them all evening, to his father, Mellie, him.

“‘When they chose new gods, war came to the city gates…Thus let all Your enemies perish, Oh Lord! But let those who love him be like the sun when it comes out in full strength. So the land had rest for forty years.’”

He had no idea how long he had slept before he woke and realized his mother was beside him, shaking him awake.

“It’s time we all got some sleep,” she suggested.

His attention shot across the room. The girl was sound asleep on the settee, her head lolling on her shoulder.

“I’m going to put her in Mellie’s room,” Hattie whispered.

He knew it would come to this, that this strange girl gone Comanch’ would be settled in his little sister’s room.

If there is a God in heaven, He’s surely mocking me now. He’s brought the enemy to our very door, Joe thought.

Hattie’s tone was hushed, almost reverent.

“For the time being, I’ve decided to call her Deborah. We can’t just go on referring to her as ‘the girl’ until Jesse discovers who she is.”

“Why Deborah?”

“It came to me tonight, as I read from the Book of Judges. Deborah’s song is a song of victory over the enemies of Israel. God’s enemies.” She paused, touched Joe lightly on the arm.

“This girl was taken by our enemy and nearly lost forever. Now she’s been found.”

Shadows filled his mother’s eyes. She sighed. “You know God’s enemies are always destroyed, don’t you, Joe?”

He heard the worry in her voice, saw the sorrow in her eyes and knew he had put it there. He wished there was some way he could explain why he could no longer bring himself to believe at all. He couldn’t imagine believing as deeply and unquestioningly in God’s presence and power as she did. He wished he could tell her when and where he’d lost his way, but he knew then that she would blame herself and he wasn’t willing to lay that burden of guilt at her door.

There was simply no way he could put his thoughts and doubts—not to mention his anger—into words that wouldn’t hurt her and so they remained unspoken between them.

His attention fell upon the girl again. Their voices had awakened her and once more she sat poised and regal as a queen, watching them. The barriers of language and customs made her appear aloof and proud, strong as the woman Deborah, the prophetess and warrior woman of the Bible.

He wondered if the girl had fought against the regiment that raided her encampment. Was the dried blood on the front of her Comanche garb that of one of the soldiers? Or that of her Comanche captors?

The answer, he decided, might always be a mystery.

A thought came to him as he rose to his feet.

“I’m going to nail the windows shut.”

“You’re going to what?” Hattie frowned.

“Nail the windows shut in Mellie’s room.” He nodded at the girl. “She might try to get out.”

“Joe, I don’t think—”

“Don’t talk me out of it, Ma. We can’t be too careful.”

“Are you planning to lock her inside the room, too?”

Slowly he nodded. “I hadn’t thought of it, but that’s not a bad idea.”

“Look at her. Her hands are burned and bandaged. She’s dead on her feet. Who knows what all she’s endured over the last few days.”

He didn’t plan on changing his mind no matter how much Hattie protested.

“I can see there’s no talking you out of it,” she mumbled.

“Not in the least.”

“Then you’d best be getting a hammer and nails. I’m putting that child to bed.”

Since Mellie’s death, the door to the small room once filled with her things had remained closed. Hammer and nails in hand, Joe opened the door and paused just over the threshold. His mother had been in earlier, gotten it ready for their “guest.”

He took a deep breath, pictured his little sister with her legs folded beneath her, seated in the middle of her bed on a blue and white quilt handed down from their grandmother Ellenberg.

Mellie loved to make up stories for the origin of each and every piece of fabric. She’d drag him into her room with her white-blond ringlets bouncing and a dimpled smile that lit up a room. More often than not, that smile shone just for him. She’d beg him to pull up a chair and listen as she spun her tales.

Tonight, a single lamp burned on the dresser and beyond the lamplight, the room was cast in darkness. Mellie’s smile was forever extinguished and she’d taken the light with her.

The windows were open to the cool night air until he closed and nailed them shut. Then he went back to the front room where Hattie waited on the settee beside the girl.

His mother pointed to herself and repeated her own name over and over. “Hattie. I’m Hattie. Hattie.”

When she noticed Joe in the doorway, she waved him over.

“Joe.” She pointed to him and repeated his name.

Then she pointed to the girl and waited for her to tell them her name.

Hattie waited. The girl remained silent.

“Hattie. Hattie.” His mother tried again.

“She’s not going to say anything, Ma.” Joe sighed and ran his fingers through his hair. “I’m turning in.”