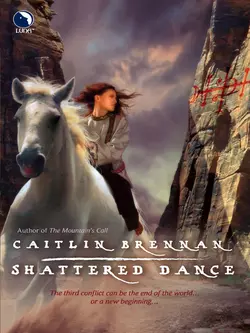

Shattered Dance

Caitlin Brennan

Once again the Aurelian Empire is in danger, and once again Valeria must risk more than her life to save it. With threats from without, including sorcerous attacks against the soon-to-be empress, and pressures from within–the need to continue the dynasty and Kerrec, the father of Valeria's child, the first choice to do so–Valeria must overcome plots and perils as she struggles to find a place in this world she's helped to heal.But her greatest foes have not been vanquished. And they won't be forgotten or ignored. Nor will the restless roil of magic within Valeria herself. Soon the threat of Unmaking, a danger to all the empire, begins to arise in Valeria's soul once more. It is subtle, it is powerful, and this time it might win out!

Selected Praise for Caitlin Brennan’s White Magic series

“Definitely a don’t-put-this-down page-turner!”

—New York Times bestselling author Mercedes Lackey on The Mountain’s Call

“Animal lovers and romantic fantasy aficionados alike will appreciate this…coming-of-age story and an exhilarating romantic adventure.”

—Romantic Times BOOKclub on The Mountain’s Call

“A riveting plot, complex characters, beautiful descriptions, and heaps of magic.”

—Romance Reviews Today on The Mountain’s Call

“Caitlin Brennan has created a masterpiece of legend and lore with her first novel. Hauntingly beautiful and extremely powerful…. Take Tolkien and Lackey and mix them together and you get this new magic that is Caitlin’s own. You will stay enthralled with each page turned.”

—The Best Reviews on The Mountain’s Call

“This is the second book in this magnificent romantic fantasy series…is full of more action, romance and drama than its prequel…. The battle scenes are magnificent, the characters are realistic and the storyline is pure magic; readers will eagerly await the next book in this tantalizing series.”

—The Best Reviews on Song of Unmaking

CAITLIN BRENNAN

SHATTERED DANCE

For Moon, Mickey and the rest of

the inmates of Riders’ Hall—

with laughter, song and the Great Debate:

Euan or Kerrec? Should a woman have to choose?

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter One

The ninth challenger was the strongest. He came out of the setting sun, bulking as broad as the flank of Dun Mor that loomed behind the killing ground. The potent animal reek of him washed over Euan Rohe, sharp as a bear’s den in the spring.

Euan swallowed bile. For three long days he had been fighting, at sunrise, noon and sunset. Eight warrior princes of the people lay dead at his hand.

Now this ninth and last came to contest Euan’s claim to the high kingship. He was the champion of the Mordantes, blessed by the One God with a madness of battle. Fear never touched him. Pain never slowed him.

Euan’s many bruises and countless small wounds ached and stung. His arm was bound and throbbing where the third challenger’s blade had slashed it open. He looked into those too-wide, too-eager eyes and saw death.

His lips drew back from his teeth. He laughed, though his throat was raw. The seventh challenger had come close to throttling him.

One more battle and he was high king—or dead. He shifted his feet, gliding out of the direct glare of the sun. The Mordante hunched his heavy shoulders and rocked from foot to foot. His hands clenched and unclenched.

One of those hands could have torn Euan’s head from his shoulders. Euan was not a small man, but he was built long and rangy, like a wolf of the steppe. This challenger was a bear with a man’s eyes.

There were stories, tales told on dark nights of men who walked in beast form and supped on human blood. Time was when Euan would have called them children’s tales. Then he had walked on the other side of the river and seen what imperial mages could do.

His mind was wandering dangerously close to the edge. He wrenched it back into focus.

The Mordante was still rocking, growling softly. The crowd of tribesmen blurred behind him, a wide circle of faces, winter-gaunt and hungry, thirsting for blood.

Euan’s adversary had no weapon but his massive body. Euan had a knife and a hunting spear and his roving wits. He lifted the spear in his hand, weighing it, aiming for the heart beneath the bearskin.

The Mordante lunged, blindingly fast. Euan’s spearpoint glanced off the heavy pelt. The haft twisted out of his hand.

A grip like a vise closed on his wrist, pulling him up against that hot and reeking body. He groped for his knife, but it was caught between them. The hilt dug into his belly, a small but vivid pain.

He went limp as if in surrender. The Mordante grunted laughter and locked arms around him, crushing the breath out of him.

Euan let his knees buckle and his body go boneless. He began to slide down. The Mordante clutched at him. His free hand snapped upward.

Blood sprayed from the broken nose—but Euan had not struck high or fast enough. It had not pierced through to the brain.

Still, it was a bitter blow. The Mordante dropped, blind and choking.

Euan was nearly as far gone, his ribs creaking and his sight going dark and then light. He staggered and almost went down.

Already the Mordante was stirring, drawing his legs under him, struggling to rise. His heavy hands clenched and unclenched. Euan’s death was in them, blood-red like the last light of the sun.

Euan’s knife was in his hand. He had one chance—one stroke. He was dizzy and reeling and his body was close to failing.

The Mordante lurched up. Euan dived toward him.

All his focus had narrowed to one spot on that wide and bristling chest. The bearskin had fallen away from it. He could hear the heart beating, hammering within its cage of blood and bone.

The whole world throbbed to that relentless rhythm. Euan’s blade thrust up through the wide-sprung ribs, twisting as the Mordante tried to fling himself away from it. But it was already lodged inside him.

Again it was not enough. The man was too big, his body too heavily padded with muscle. His long arms dragged Euan in once more, his hands groping for Euan’s throat, to crush the windpipe and break the neck.

Euan had no defenses left. All he could do was keep his waning grip on the knife’s hilt and let the Mordante’s own weight thrust it deeper.

The pounding went on and on. It was coming from outside now. The tribes were stamping their feet, beating on drums and shields, roaring the death chant.

It was very dim and far away. With the last of his consciousness, Euan felt the knife’s blade pass through something that resisted, then gave way. The hilt throbbed in his hand, leaped out of it and then went still.

Euan spun down through endless space. Pain was a distant memory. Fear, desperation—only words. Sweet darkness surrounded him. Lovely death embraced him.

It was warm. He had not expected that. He could almost believe it had a face—a woman’s face, a smooth oval carved in ivory, with eyes neither brown nor green, flecked with gold.

He knew that face, those eyes, as if they had been his own. He reached for them, but they slipped away.

The thunder of his pulse had shaped itself into human sense. Voices were chanting over and over.

Ard Ri! Ard Ri Mor! Ard Ri! Ard Ri Mor!

They were acclaiming the high king.

The Mordante was dead. Euan had felt his heart stop. He was dead, too. Then how—or who—

A sharp and all too familiar voice filled the world. “Up now. Wake. I’m done carrying you.”

Purest white-hot hatred flung Euan back into the light. More hands than he could count lifted him up. He rode on the shoulders of his warband, his most loyal companions.

The sun had died in blood, pouring its death across the sky. The royal fires sprang up around the killing ground and along the hilltops. They would be lit from end to end of the people’s lands, leaping across the high places, declaring to all the tribes that there was a king again in Dun Mor.

Euan looked for the man who had dragged him back from the edge of death. All the faces around him were familiar and beloved, his blood brothers and his kin. He had to look far into the shadows to find the slight dark figure with its terrible weight of magic.

By the One God, he hated the man—but there was no denying that Euan owed him a debt. He had brought Euan out of the dark. Euan was awake again, alive and aware.

Euan straightened painfully. The strongest men of his warband lifted a shield and held it high. The rest reached to lift him up, but he had a little strength left.

He snatched a spear from the hand of a man who was shouting and brandishing it. All his aches and wounds cried protest. He ignored them.

A path opened before him. He sprinted along it, grounded the spear and launched himself toward the shield.

He hung in air, briefly certain that he had failed. He would fall. If he was lucky he would break his neck rather than suffer such an omen against his kingship.

His feet struck the shield with blessed solidity. It rocked under his weight but steadied. He stood high above the people, dizzy and breathless, grinning like a mad thing.

He spread his arms wide as if to embrace the world. He had done it. He had won. He was the Ard Ri, high king of all the tribes.

“Now you have what you wanted,” Gothard said. “Only remember. Glory always has a price.”

“I could not possibly forget,” Euan said.

He had danced and drunk and feasted from night into morning, then slept a little and woke to Gothard’s face staring down at him. It was not the sight he would have liked to see on his first day as Ard Ri. He would have given much never to see it at all.

But there the man was, squatting in this still unfamiliar tent. Neither the warband nor the royal guard had managed to keep him out.

Nothing in this world could, maybe. Gothard was a dead man, a sorcerer who had been destroyed and his body unmade—but he had come back through the power of his magic to walk among the living. The peculiar horror of his existence was not that he was terrible to look at or speak to, but that he seemed so mortally ordinary.

Euan sat up carefully. While he slept, he had been bathed and salved and his arm newly bandaged.

Except for Gothard’s presence, Euan felt remarkably well. His head barely ached and his wounds were no trouble. Even his badly abused throat was less raw than he might have expected.

He would have been smiling if anyone but Gothard had been watching. As it was, his frown was not quite as black as it could have been. “What do you want?” he demanded—rude, yes, but the two of them were long past any pretense of civility.

“It’s tradition, you know,” Gothard said. “When the new king first wakes, his most loyal servant admonishes him against excessive pride and bids him remember the price of glory. It’s usually a priest who does it. Aren’t you glad I came instead?”

“No,” Euan said. It was hard not to growl, the state his voice was in, but this was intentional.

“I do smell better,” Gothard pointed out. For him, that was rollicking humor. “You’re given three days to enjoy your elevation. Then the reality of it comes crashing in. I’m to remind you that these aren’t the tribes your predecessor ruled. They’ve suffered a monstrous defeat and great loss of life and strength. The winter has been brutal and the weak or wounded who did not die in battle are dead of starvation and sickness. It’s a raw, bleak spring with a grim summer ahead, while the empire strips us of what little we have left and crushes us under the heels of its legions.

“You are high king of the people, and that’s a great thing—but it’s also a heavy burden. Even if they were victorious, you would still bear all their ills as well as their triumphs. Now in defeat, it’s all on your shoulders. You bear the brunt and you carry the blame.”

Euan’s shoulders sagged as if they were indeed loaded down with all the horrors of a disastrous war and its even grimmer aftermath. But he was no mage’s toy, whatever Gothard might hope to make of him. He shook off the spell with a snap of contempt. “You don’t think I know all that? This is mine and always has been. I was meant for it.”

“Surely,” said Gothard, “but are you prepared for the bad as well as the good?”

“I’ve ridden out two great defeats,” Euan said. “There will be no third. You are going to help me make sure of that.”

Gothard’s brows arched. “A new plan, my lord?”

“Maybe.” Euan rose carefully from his blankets. “Maybe the same one, with refinements. We don’t need to destroy the imperial armies if we destroy its leaders. We’ve known that from the beginning.”

“But war is so much more glorious than conspiracy and assassination.” Gothard’s tone was mocking but his eyes were deadly earnest. “Will the tribes understand, do you think?”

“The people won’t be going to war again for a long time,” Euan said. “It’s not a choice between glory and practicality. There’s no glory left.”

“You want revenge.”

“Don’t you?”

Gothard’s smile showed an edge of fang. “What do you have in mind?”

“Come to me after the kingmaking is over,” Euan said. “It’s time to strike the deathblow against the empire. We’ve failed twice. Third time will end it—one way or the other.”

The gleam of Gothard’s eyes told Euan his words had struck home. Gothard was half an imperial. The late emperor had sired him on a concubine, and by that accident of birth denied him the right to claim the throne—a fact for which Gothard hated his father with intensity that had nothing sane about it.

Gothard had raised the powers that destroyed the emperor and almost taken the rest of the world with him. If he had his way, his sister who was soon to be crowned empress and his brother who was something else altogether would be worse than dead—Unmade, so that nothing was left of them, not even a memory.

Gothard said no word of that, nor had Euan expected him to. He turned on Euan instead and said, “You’d die and abandon the people?”

“I’ll go down with them,” Euan said, “if that’s how it has to be.”

“Maybe you are meant to be king,” Gothard said.

“If I had been king sooner, we would not have lost the war.” Euan could feel the anger rising, old now and deep but as strong as ever. He throttled it down. There was no profit in wasting it on Gothard, who was his ally—however unwelcome.

He forced a smile. It was more of a rictus grin, but it would have to do. “Still. Now I am the Ard Ri. Maybe I’ll do better than the one who went before me. Maybe I’ll do worse. But I’ll do the best I can for my people. That, I’m sworn to.”

It was not so far off from the oath he had taken while the last challenger’s body was still warm, when he was lifted up in front of the people and invested with the mantle and the spear and the heavy golden torque. But now, in front of his most hated ally, he spoke from the heart. He felt the earth shift under his feet, rocking and then going still, as it was said to do when a man of power swore a great oath.

He meant every word. He would live and die by it. Life and soul were bound to it.

That was as it should be. He left the tent that he had won and the ally the One God had imposed upon him, and stepped out into the cold bright morning, the first morning of his high kingship.

Chapter Two

The Mountain slept, locked deep in winter’s snow. Far beneath the ice and cold and the cracking of frozen stone, the fire of its magic burned low.

It would wake soon and send forth the Call, and young men—and maybe women—would come from the whole of Aurelia to answer it. But tonight it was asleep. One might almost imagine that it was a mortal place and its powers mortal powers, and gods who wore the shape of white horses did not graze its high pastures.

Valeria leaned on the window frame. The moon was high, casting cold light on the Mountain’s summit. It glowed blue-white against the luminous sky.

“Has anyone ever been up there?” she asked. “All the way past the Ladies’ pastures to the top?”

Kerrec wrapped her in a warm blanket, with his arms around that, cradling the expanding curve of her belly. He kissed the place where her neck and shoulder joined and rested his chin lightly on her shoulder. His voice was soft and deep in her ear. “There’s a legend of a rider who tried it, but he either came back mad or never came back at all.”

“Why? What’s up there?”

“Ice and snow and pitiless stone, and air too thin to breathe,” he said, “and, they say, a gate of time and the gods. The Great Ones come through it into this world, and the Ladies come and go, or so it’s said. It’s beyond human understanding.”

“You believe that?”

“I can’t disprove it,” he said.

“Someday maybe someone will.”

“Not you,” he said firmly, “and not now.”

She turned in his arms. He looked like an emperor on an old coin, with his clean-carved face and narrow arched nose—not at all surprising, since those bygone emperors had been his ancestors—but lately he had learned to unbend a little. In spite of his stern words, he was almost smiling.

“Not before spring,” she conceded. She kissed him, taking her time about it.

The baby stirred between them, kicking so hard she gasped. He clutched at her. She pushed him away, half laughing and half glaring. “Stop that! I’m not dying. Neither is she.”

“Are you sure?” he said. “You looked so—”

“Shocked? She kicks like a mule.” Valeria rubbed her side where the pain was slowly fading. “Go on, go to sleep. I’ll be there in a while.”

He eyed her narrowly. “You promise? No wandering out to the stable again?”

“Not tonight,” she said. “It’s too cold.”

He snorted softly, sounding exactly like one of the stallions. Then he yawned. It was late and dawn came early, even at the end of winter. He stole one last kiss before he retreated to the warmth of their bed.

After a few moments she heard his breathing slow and deepen. She wrapped the blanket tighter.

Inside her where the stallions always were, standing in a ring of long white faces and quiet eyes, the moon was shining even more brightly than on the Mountain. Power was waking, subtle but clear, welling up like a spring from the deep heart of the earth. The world was changing again—for good or ill. She was not prophet enough to know which.

She turned away quickly from the window and the moon and dived into bed. Kerrec’s warmth was a blessing. His voice murmured sleepily and his arms closed around her, warding her against the cold.

Kerrec was gone when she woke. Breakfast waited on the table by the fire, with a Word on it to keep the porridge hot and the cream cold. Valeria would rather have gone to the dining hall, but she had to smile at the gift.

She was ravenously hungry—no more sickness in the mornings, thank the gods. She scraped the bowl clean and drank all of the tea. Then she dressed, scowling as she struggled to fasten the breeches. She was fast growing out of them.

Her stallions were waiting for her in their stable. She was not to clean stalls now by the Healer’s order—fool of a man, he persisted in thinking she was delicate. But she was still riding, and be damned to anyone who tried to stop her.

Sabata pawed the door of his stall as she walked down the aisle. The noise was deafening. Oda, ancient and wise, nibbled the remains of his breakfast. The third, Marina, whickered beneath Sabata’s thunderous pounding.

She paused to stroke Marina’s soft nose and murmur in his ear. He was older than Sabata though still rather young, taller and lighter-boned, with a quiet disposition and a gentle eye. He had been the last stallion that old Rugier trained, a Third Rider who never rose higher or wanted to—but he had had the best hands in the school.

Rugier had died after Midwinter Dance, peacefully in his sleep. The next morning Marina moved himself into the stall next to Oda’s and made it clear that Valeria was to continue his training.

That was also the morning when Valeria confessed to Master Nikos that she was expecting a child. She had planned it carefully, rehearsing the words over and over until she could recite them in her sleep. But when she went to say them, there was a great to-do over Rugier’s passing, and then there was Marina declaring his choice of a rider-candidate over all the riders in the school.

“I suppose,” Master Nikos said after they had retreated from the stable to his study, “we should be thinking of testing you for Fourth Rider. You’re young for it, but we’ve had others as young. That’s less of a scandal than a rider-candidate with three Great Ones to train and be trained by.”

“Are you sure I’m ready?” Valeria asked. “I don’t want to—”

“The stallions say you are,” Nikos said. “I would prefer to wait until after Midsummer—if you can be so patient.”

“Patience is a rider’s discipline,” Valeria said. “Besides, I suppose it’s better to wait until after the baby is born.”

For a long moment she was sure he had not heard her. His mind was ranging far ahead, planning the testing and no doubt passing on to other matters of more immediate consequence.

Then he said, “That’s what I’ve been thinking.”

Valeria had been standing at attention. Her knees almost gave way. “You—how—”

“We’re not always blind,” Nikos said.

She scraped her wits together. “How long have you known?”

“Long enough to see past scandal to the inevitability of it all,” he said. “The stallions are fierce in your defense.”

“They’re stallions,” she said. “That’s what they’re for.”

Master Nikos sighed gustily. “You, madam, are more trouble than this school has seen in all its years. You are also more beloved of the stallions than any rider in memory. Sooner or later, even the most recalcitrant of us has to face the truth. You are not ours to judge. You belong to the gods.”

Valeria’s mouth was hanging open. She shut it carefully. “Do the other riders agree with you?”

“Probably not,” he said, “but sooner or later they’ll have to. We all profess to serve the gods. That service is not always as easy or simple as we might like.”

“I’m going to keep and raise this child,” she said. She made no effort to keep the defiance out of her voice. “I won’t give her up or send her out for fostering.”

Master Nikos neither laughed nor scowled. He simply said, “I would expect no less.”

He had caught Valeria completely off balance. It was a lesson, like everything else in this place. People could change. Minds could shift if they had to. Even a senior rider could accept the unacceptable, because there was no other choice.

In this early morning at the end of winter, three months after Master Nikos had proved that not everything a rider did was predictable, the stallions were fresh and eager. So were the riders who came to join Valeria in the riding hall. The patterns they transcribed in the raked sand were both deliberate and random—deliberate in that they were training exercises, random in that they were not meant to open the doors of time or fate.

Valeria could see those patterns more clearly the longer she studied in the school. She had to be careful not to lose herself in them. The baby changed her body’s balance, but it was doing something to her mind as well. Some things she could see more clearly. Others barely made sense at all.

Today she rode Sabata, then Marina, then Oda—each set of figures more complex than the last. Her knees were weak when she finished with Oda, but she made sure no one saw. The last thing she needed was a flock of clucking riders. They fussed enough as it was, as if no other woman in the history of the world had ever been in her condition.

It was only a moment’s weakness. By the time she had run up the stirrups and taken the reins, she was steady again. She could even smile at the riders who were coming in, and face the rest of the morning’s duties without thinking longingly of her bed.

This would end soon enough—though she suspected the last of it would seem interminable. She unsaddled Oda and rubbed him down, then turned him out in one of the paddocks. He broke away from her like a young thing, bucking and snorting, dancing his delight in the bright spring sun.

Chapter Three

Morag left the caravan in one of the wide stone courts of the citadel. “Be sure you take your medicine for three more days,” she warned the caravan master by way of farewell, “or the fever will be back, no better than before.”

“Yes, my lady,” the man said. “I won’t miss a dose, my lady.”

“See that you don’t,” she said. She considered reminding him that she was not a noblewoman and had no slightest desire to be one, but that battle was long lost. She fixed him with a last stern glare, at which he duly and properly flinched, then judged it best to let him be.

She found a groom to look after her mule and cart and paid him a silver penny to guard the belongings in the cart. Not that that was strictly necessary—there was a Word of guard and binding on them—but the boy had the lean and hungry look of a young thing growing too fast for himself.

He seemed glad enough to take the penny. He told her in careful detail where to find the one she was looking for, although he said, “You won’t get that far. They keep to themselves, that kind do.”

“I’m sure they do,” Morag said and thanked him. He seemed a little startled by that. Manners here on the Mountain were not what they might be.

Too many nobles, not enough common sense. She shook her head as she made her way through this unexpected place.

She had expected a castle with a village of farmers nearby to keep it fed. This had the fields and farms all around it, but it was much more than a fortress. It was a city of no mean size, built on the knees of the Mountain.

Ordinary people lived in it, servants and artisans and tradesmen. There were markets and shops, taverns and inns, and once she passed a theatre hung with banners proclaiming some grand entertainment direct from the empire’s capital.

The groom had warned her not to wander to the west side—that, he said, was the School of War. The greater school lay to the north and east, toward the towering, snow-crowned bulk of the Mountain. She could see it everywhere she walked, down alleys and over the roofs of houses.

The power of its presence made her head ache. It must be sending out the Call. She was not meant to hear it, but her magic was strong. She could feel it thrumming in her bones.

She refused to let it cow her. Magic was magic, whatever form it took. She advanced with a firm stride toward the gate with its carven arch.

There were no guards standing there. She had seen riders walking in the city, men and boys—never women or girls—dressed like servants in brown or grey. But no servant ever walked as they walked, with a casual arrogance that put princes to shame.

None of them guarded the gate to their school. There was no magic, either, no wards as Morag would have known them. And yet she paused.

The carving of the arch was worn with age and almost indistinguishable, but she could make out the shapes of men on horseback. The men rode light and erect. The horses were blocky, cobby things, thickset and sturdy—there was nothing delicate or ethereal about them. They were born of earth and stone, though their hearts might be celestial fire.

Morag shook her head to clear it. The gate blurred in front of her. It was trying to disappear.

“Clever,” she said. It was a subtle spell, masterfully cast. She might not have detected it at all if she had not been looking for it.

Once she recognized it, she saw the way through it. She only had to walk straight under the arch and refuse to see any illusion that the gate might weave for her.

It did its best. The wall was thick, but it tried to convince her that the passage through the gate was a furlong and more. Then it tried to twist and fling visions at her, armed guards and galloping horsemen.

The visions melted as she walked into them. The turns grew suddenly straight. She stood in the sunlight of a sandy courtyard surrounded by tall grey walls.

Windows were open above, catching the warmth of the day. She heard voices reciting and a lone sweet tenor singing, and at greater distance, the high fierce call of a stallion.

Beneath it all ran a steady pulse. It had the rhythm of a slow heartbeat, but there was a ringing depth to it that marked it as something else.

Hoofbeats. The gods were dancing in their courts and halls.

She followed the beats that seemed most in tune with her own heart. They led her down passages and along the edges of courtyards. Some had riders in them, mounted on white stallions, or men on foot plying long lines while the stallions danced in circles or twining patterns around and across the sandy spaces.

None of the riders took any notice of her. They were in a trance of sorts, intensely focused on their work. The horses flicked an ear now and then, and once or twice a big dark eye rolled in her direction, but they made no move to stop her.

They knew her. She could not say they offered her welcome, but the air seemed a little less thin and the place a little less strange.

She granted them a flicker of respect. Their awareness guided her to the northern wall of the citadel, a long expanse of grassy paddocks in clear view of the Mountain. Blocky white shapes grazed and gamboled there, and at the western end was another court where yet more riders danced.

She turned away from the court toward the colonnade that ran along its edge, ascending a stone stair into a tower that, as she went up, overlooked the citadel and the fields and forest that surrounded it and the Mountain that reared above them all.

Just short of the top was a room surrounded by windows, a place of light. It was empty but for a man who sat on one of the window ledges. He was an old man, his faced lined and his hair gone grey, but he was still supple enough to fold himself into the embrasure with a book on his knees.

Morag waited for him to finish reading his page. She made no effort to intrude on his awareness, but he was a mage. He could sense the shift of patterns in the room. After a while the awareness grew strong enough that he looked up.

His expression was bland and his tone was mild, but annoyance was sharp beneath. “Madam. All the servants should know I’m not to be disturbed.”

Morag folded her arms and tilted her head. “That’s refreshing. Everyone else persists in taking me for a noblewoman.”

His brow arched. “Should I recognize you?”

“Not at all,” she said. “My daughter takes after her father’s side of the family. How is she? Still here, I hope. I’d be a bit put out if she turned out to be in Aurelia after all.”

He blinked, clearly considered several responses, then stopped as the patterns fell into place around her. It was fascinating to watch. Morag had a bit of that kind of magic—it was useful for a wisewoman to be able to see where everything fit together, the better to repair what was broken—but this was a master of the art. The Master, to be exact.

At length he said, “Ah. Madam. My apologies.” He unfolded himself from the window ledge and bowed with courtly grace. “Not a noblewoman, no, but a great lady. I see it’s no accident your daughter is what she is.”

Morag studied both the face he showed her and the one, much younger and brighter, that she could see behind it. “You respect her,” she said. “Good. Even after…?”

“The white gods and the Ladies have made it clear,” the Master of the riders said, “that she is their beloved. Whatever she does, whatever becomes of her, she has their blessing. Riders are stubborn and mired in tradition, but even we can learn to accept what we can’t change.”

“I’m not sure I believe you,” said Morag.

His smile was wry. “Do you know, she said the same. It’s no less true for that.”

“I hope so,” Morag said, “for your sake. So she’s well? Not locked in a dungeon?”

“Well, loved, pampered—the child when it comes will have a hundred uncles.”

Morag allowed herself to soften just a fraction. “Good, then. I’m spared the trouble of setting this place to rights. Now if you’ll excuse me, you have an hour left of your escape from duty and tedium, and I have a daughter to find.”

“She’s down below,” the Master said.

“I know,” said Morag, gently enough when all was considered. She nodded briskly. He nodded back with more than the hint of a bow.

Good man, she thought, and no more of a fool than any man was inclined to be. He had reassured her more than he knew. Her opinion of the riders and their school had risen somewhat, though she was still reserving judgment.

Chapter Four

“Straighten your shoulders,” Valeria said. “Good. Now lift him with your tailbone—yes, so.”

The stallion who circled Valeria sat for an instant, then floated from a cadenced trot into a slow and rhythmic canter. The young rider on his back flashed a grin before he remembered to be properly serious.

She bit her lip to keep from grinning back. She had to be proper, too, if she was going to pass muster to become a Fourth Rider. Riders might have changed enough to accept a woman among them, but they still had certain expectations as to manners and deportment.

She shifted on the stool the Healers had insisted she resort to when she instructed her handful of rider-candidates, and rubbed her back where the baby’s weight was taking its toll. She had had to stop riding a few days ago, out of pity for her poor stallions who had to carry her burgeoning bulk. She missed it less than she had expected. Now all she wanted was to be done with this labor of growing a child.

Rider-candidate Lucius was losing that lovely canter. “Hold and release,” she said quickly. “Shoulders straight, remember. Now, sit back and hold.”

Lucius held just a fraction too long. Sabata’s ear flicked. With no more warning than that, he stopped short. Lucius lurched onto his neck.

Valeria held her breath. But Sabata had decided to be merciful. He let Lucius recover his balance and his breath, and did not tip him unceremoniously into the sand.

For that the stallion had earned an extra lump of sugar and a pat on the neck. Even a season ago, he would have yielded to temptation. He was growing up.

The baby woke abruptly and kicked so hard Valeria wheezed. Fortunately Lucius was too busy dismounting to notice. She eased from the stool and eyed the distance from it to the colonnade, then from there to the schoolroom where she was to assist First Rider Gunnar with a particularly obstreperous roomful of second-year rider-candidates.

The day’s lesson was clear in her head. History and philosophy, dry but essential for understanding the patterns that made the empire what it was. But first she had to get there.

Sabata’s whiskers tickled her ear. She ducked before he snorted wetly in it. He presented his shoulder.

“You don’t want to carry me,” she said. “I’m like a sack of barley.”

His ears flattened. She was being ridiculous and they both knew it. He folded his forelegs and lay down, saddle and all—to Lucius’ vocal dismay.

She sighed, but she yielded to superior logic. She stepped astride.

He rose as carefully as he could. She could not deny that his back was a warm and welcoming place, even as badly balanced as she was. He professed not to mind.

He carried her all the way to the outer court, attracting glances and occasional expostulations, but no one was fool enough to risk Sabata’s teeth and heels. At the door to the schoolrooms, he deposited her with exquisite care.

She had a fair escort by then, rider-candidates of various years and a rider or two. Not all of them were on their way to the afternoon’s lesson.

They would have carried her up the stair if she had let them, but she was humiliated enough as it was. “Damn it!” she snapped at the lot of them. “I’m not a cripple. I can walk.”

“So you can,” said a voice she had not expected to hear at all—not for another month.

She whirled and nearly fell over. Her mother measured her with a hard, clear eye. “Walking’s good for you. Riding, not so much.”

“He insisted,” Valeria said, jabbing her chin at Sabata. The stallion stared blandly back, as if anyone here could believe that he was an ordinary animal.

“He must have had his reasons,” Morag said. “Whatever you were planning to do up there, unplan it. You’re coming with me.”

“I am not—” Valeria began.

“Go on,” said Gunnar, looming above the pack of boys. He was half again as big as the biggest of them, a golden giant of a man. “I’ll manage with this lot.”

“But—” said Valeria.

“Go,” the First Rider said.

That was an order. Valeria snarled at it, but there was no good reason to disobey it. She was tired—she had to admit that. She wanted to lie down.

That made her angry, but she had enough discipline, just, not to lash out. She caught Sabata’s eye. There was an ironic glint in it. She was growing up, too.

Morag’s examination was swift, deft and completely without sentiment. When she was done, she washed her hands in the basin that she had ordered one of the servants to have ready, then sat beside the bed in which Valeria was lying. “You’re certain when you conceived?” she asked.

“Why?” Valeria demanded. She tried to throttle down the leap of alarm, but it was hard. “Is the baby too small? Is there something wrong?”

“Nothing wrong at all,” said Morag, “but she’s nearer being born than I’d expect. Are you sure you’re not a month off in your calculations?”

“Positive,” Valeria said. “She’s really all right? She’s not—”

“All’s well as far as I can see,” Morag said, “but you’ll be pampering yourself a bit more after this. If you’re tired, you rest. And no more riding—no matter how much the horse may insist.”

“I was tired,” Valeria said. “That was why—”

“It was considerate of him,” her mother said, “but you won’t be doing it again until this baby is born. Which may be sooner than any of us expects. Have you had any cramping?”

“Nothing to fret over,” Valeria said.

“Ah,” said her mother as if she had confessed to a great deal more than she intended. “You rest. I’ll let you be. Are you hungry?”

“Not really,” said Valeria. “Where are you going? What—”

“I’ll fetch you a posset,” Morag said. “Rest. Sleep if you can. You’ll be getting little enough of that soon enough.”

Valeria let the storm of protest rise up in her and die unspoken. Morag was already gone. She was almost sinfully glad to be lying in her bed, bolstered with pillows, with the curtains drawn and the room dim and cool.

It was decadent. She should not allow it. But she had no will to get up. The baby stopped battering her with fists and heels and drifted back into a dream. She was as comfortable as she could be, this late in pregnancy.

She let herself give way to the inevitable. Sleep when it came was deep and sweet, with an air about it of her mother’s magic.

Kerrec was putting a stallion through his paces in yet another of the many riding courts that made up the school. Morag watched him with an eye that was, if not expert, then at least interested.

He had changed since she last saw him, back in the autumn. The gaunt and haunted look was gone. He was as relaxed as she suspected he could be. He would always have a hint of the ramrod about him, but he looked elegant and disciplined rather than stiffly haughty.

He was a beautiful rider. He flowed with his horse’s movements. There was no jerkiness, no disruption in the harmony.

His face was naturally stern, with its long arched nose and somber mouth, but there was a hint of lightness in it. He was smiling ever so slightly, and his odd light eyes were remarkably warm.

This was a happy man—in spite of everything he had suffered, or maybe because of it. Morag did not like to cloud that happiness, but there were things she had to say.

He was aware of her—she felt the brush of his thoughts—but he did not alter the rhythm of his horse’s dance. Morag waited patiently. This was a subtle working but a great one, a minor Dance of time and the world’s patterns. The sun was a little warmer for it, and the day a little brighter.

The Dance ended with a flourish that might be for the watcher, a dance in place that stilled into a deep gathering of the hindquarters and a raising of the forehand. The white stallion poised for a long moment like a statue in an imperial square. Then, with strength that made Morag’s breath catch, he lowered himself to stand immobile.

She remembered to breathe again. Kerrec sprang lightly from the saddle and bowed to the stallion. The beast bent his head as if he had been an emperor granting the gift of his favor, then lipped a bit of sugar from his rider’s palm.

A boy led the stallion away. Kerrec turned to Morag at last. “Madam! Welcome. I’ve been waiting for you.”

“Have you?” said Morag.

He stripped off gloves and leather coat and began to walk toward the edge of the courtyard. She fell in beside him. He was only a little taller than she—not a tall man, but graceful and compact and very strong.

He did not respond until they had entered the shade of the colonnade. There was a bench there, though he did not sit on it. He stopped and faced her. “You’ve seen her. What do you think?”

“I think the baby will come within the week, if not sooner,” Morag answered. “She seems to be in a hurry to be born.”

“It’s not terribly early,” he said. “Is it? She’ll be safe. They both will.”

“Gods willing,” Morag said. “Why? Is something troubling you?”

He shrugged. He looked very young then, almost painfully uncomfortable with the emotions that tangled in him. “It’s just fretting, I’m sure. The Healers say all is going as it should. She’s managing well. There’s nothing to fear.”

“Healers aren’t midwives,” Morag said, “or wisewomen, either. Yes, you’re fretting, but sometimes there’s a reason for it. I don’t suppose you’ve taken any time to find a wetnurse?”

He frowned. “A nurse? Are you afraid she won’t be able to—” He stopped. His whole body went still. “You think she’s going to die.”

Morag glared. “I do not. I’m being practical, that’s all. How long do you think she’ll let herself be tied down to a baby? She’ll be wanting to ride and teach and work magic as soon as she can get up.”

“Yes, but—”

She cut him off. Men were all fools, even men who were mages and imperial princes. “Never mind. I’ll see if there’s someone suitable here. If not, we’ll send to the nearest city.”

“I’m sure there’s someone here,” he said a little stiffly. “I’ll see to it today.”

“I’ll do it for you,” Morag said. “You go, do what First Riders do on spring afternoons. Valeria isn’t going to die, and she’s not likely to drop the baby tonight. We’ll both watch her. Then when it happens, we’ll be ready.”

He nodded. Some of the tension left him, but his shoulders were tight. She had alarmed him more than she meant.

Maybe it was to the good. Kerrec had certain gifts that made him a remarkable assistant during a birthing. If he was on guard, those gifts would be all the stronger.

She patted his arm, putting a flicker of magic into it. He relaxed in spite of himself. “Stop fussing,” she said. “I’m here. If I have to go to the gates of death and pull her back with my own hands, I will keep my daughter safe. You have my word on it.”

“And your granddaughter?”

She almost laughed. Trust that quick mind to miss nothing. “Safer still. She’ll have a long and prosperous life, if I have any say in it.”

“And I,” he said with an undertone that made her hackles rise. She should not forget that he was a mage and a powerful one. Even the gods would yield to his will if he saw fit to command them. In this, for the woman he loved and the child of his body, he most certainly would.

Chapter Five

Valeria woke to morning light, a noble hunger, and a plump and placid girl sitting by the window, nursing an equally plump child.

She scowled. It was her window, she was sure of that, in the room she shared with Kerrec. And here was this stranger, who might be a servant, but what was she doing with a suckling child?

Morag’s tall and robust figure interposed itself between Valeria and the girl. “Good morning,” she said. “Breakfast is coming. Come and have a bath.”

Valeria sat up. She had been dreaming that the baby was born and she was her slender self again, riding Sabata through a fragment of the Dance. The dream had been sweet, but her mood was strange.

She felt heavier and more ungainly than ever. The bath soothed a little of that. Breakfast was more than welcome, but her appetite faded as fast as it had risen. She ate a few mouthfuls and pushed the rest away.

In all that time, Morag had not explained the girl by the window. The child finished nursing, clambered down from the girl’s lap and came to stand with his thumb in his mouth, staring at Valeria with wide brown eyes.

“This is a rider’s son,” Valeria said. “Is that his mother?”

“That is Portia,” Morag said. “Portia is deaf and mute, but she’s quite intelligent. She’ll nurse your daughter when you go back to being a rider.”

“She will not!” Valeria said fiercely. “I’ll raise my child myself. I don’t need—”

“Of course you do,” said Morag. She dipped a spoonful of lukewarm porridge and cream. “Here, eat. You’re feeding the baby, too, don’t forget.”

“Are you trying to make me sorry you ever came?”

“You’ll be glad enough of me before the day is out,” Morag said. “Finish this and then we’ll walk. You want to visit your horses, don’t you?”

Valeria glowered, but there was no resisting her mother. “This argument isn’t over,” she said. “When I come back, I want that girl gone.”

“I’m sure you do,” Morag said, unperturbed. “Eat. Then walk.”

Morag was relentless. Valeria did not like to admit it, but she was glad to be up and out. She was not so glad to be marched through the whole school and half the city, then back again. She was a rider, not a foot soldier.

At least the long march included the stable and her stallions. Sabata and Oda were in the paddocks behind the stallions’ stable. Marina was instructing a rider-candidate under Kerrec’s stern eye.

Orontius was a competent rider, but he was profoundly in awe of Kerrec. That awe distracted him and made him clumsy. He almost wept at the sight of Valeria.

She forgot her strange mood and her body’s sluggishness. “There now,” she said. “Remember what we practiced yesterday? Show us how it went.”

Orontius breathed so deep his body shuddered. Then, to Valeria’s relief, he remembered how to focus.

Marina’s own relief was palpable. A stiff and distracted rider was no pleasure for any horse to carry, even one as patient as the stallion. As Orontius relaxed, his balance grew steadier and his body softer. He began to flow with the movement as a rider should.

Kerrec would hardly unbend so far as to laugh in front of a student, but his glance at Valeria had a flicker of mirth in it. He knew how he seemed to these raw boys. Sometimes it distressed him, but mostly he was indulgent.

Valeria could remember when he had been truly terrifying. He was merely alarming now. He was even known, on rare occasions, to smile.

She slipped her hand into his. His fingers laced with hers, enfolding her in warmth. She knew better than to lean on him in front of half a dozen rider-candidates and their instructors, but his presence bolstered her wonderfully.

Orontius finished his lesson without falling into further disgrace. Lucius was waiting his turn, holding the rein of Kerrec’s stallion Petra. Valeria caught his eye and smiled.

“I’ll teach this one,” she said.

“Are you sure?” Kerrec asked.

He was not asking her. His eyes were on Morag.

Valeria’s temper flared. She opened her mouth to upbraid them both, but the words never came. She felt…strange. Very. Something had let go. Something warm and wet. Something…

Kerrec swept her off her feet. She struggled purely instinctively, but his single sharp word put an end to that. She clutched at his neck as he began to run—biting back the question that logic bade her ask. “Why carry me? Can’t I ride?”

She knew what his answer would be. Not now.

The baby was coming. Not this instant—Valeria was not a mare, to race from water breaking to foal on the ground in half a turn of the glass. Human women were notably less blessed. But the birth had begun. There was no stopping it.

She had thought she would be afraid. Fear was there, but it was distant, like a voice yammering almost out of earshot. The pains were much more immediate.

They were sharper than she had expected, and cut deeper. They wrenched her from the inside out.

Kerrec was with her. He would not let her go.

A very remote part of her was comforted. The rest was in stark terror.

The pains were too strong. They should not be like this. They set hooks in the deepest part of her, the part that she had buried and bound and prayed never to see again.

The Unmaking had roused. Absolute nothingness opened at the core of everything she was.

All because she had read a spell in an old and justly forgotten book, not so long ago. It had been quiescent since she came back to the Mountain from the war and the great victory. She thought she had overcome it.

She had been an idiot. It had been waiting, that was all, biding its time until she was as vulnerable as a human creature could be.

She should be riding out the pains, guiding her child into the light. Instead, all the power she had went into holding back the Unmaking.

She did not have to panic. Her mother was there. So was Kerrec. They would keep the baby safe. She had to believe that.

She could feel Kerrec around her, holding her. His quiet strength brought comfort even through the terror that was trying to swallow her. It was always there, always with her, no matter where she was or what she did. It was as much a part of them both as the color of their eyes or the shape of their hands.

She leaned back against him. It was a strange sensation, as if she moved her body from without with a third hand while the rest kept a death grip on the Unmaking. His lips brushed her hair, a gesture so casual and yet so tender that she nearly wept.

She had no choice but to hold on and be strong. No one could help her with this. No one here even knew.

They could not know. If they did, they would try to help—and the Unmaking would lair in them, too. She would rather give herself up to it than destroy them.

That hardened her heart. Her grip had been slipping, but now it firmed. She walled the Unmaking in magic, calling on the strength of the Mountain and the stallions who were always within her.

She would never have dared to do that if it had not been for the three whom she protected—not only her lover and her mother but the child who struggled to be born. The Unmaking must never touch them. That was a great vow, as deep as the Unmaking itself.

Valeria lay barely conscious against Kerrec’s body. Pains racked her, but her spirit was elsewhere. She had gone far inside herself behind walls and wards so strong he dared not break them for fear of breaking her.

“Is it always this way with mages?” he asked her mother.

Morag’s frown was etched deep between her brows. “I’ve never midwived a horse mage before. No one has. Her body is doing well enough. The baby is coming as it should. But—”

“But?”

“I don’t know,” Morag said, and that clearly angered her. “Is there something about horse magic that makes this unduly difficult?”

“Not unless the old riders are right and it matters that she’s a woman.” Kerrec shook his head as soon as he said it. “No. That’s not what it is. It’s not our magic at all.”

“Then what—”

“I can’t tell,” Kerrec said with tight-strained patience. “She won’t let me in. And no, I can’t force it. She’s woven the wards too well.”

“We’ll do our best without her, then,” Morag said. “Damn the girl! She’s never in her life made anything simple.”

Kerrec bit his lip. He would be the first to admit that the two of them were all too well matched.

The body in his arms went stiff with a new and stronger contraction. The life inside sparked with fear. He smoothed the world’s patterns around it—not so much that the birthing stopped, but enough to take away the worst of the pain.

He walled his own fears inside. That much of Valeria’s example he could follow. He had to be steady and strong to bring his daughter into the world.

There was a deep rightness in that. The patterns opened to accept her. She was a strong spirit, brimming with magic. She yearned toward the light.

He showed her the way. It seemed terribly long and slow, but as human births went, it was remarkably fast.

Valeria woke in the middle of it. Her consciousness flared like a beacon. The child veered away from Kerrec and toward that much brighter light.

He caught them both. Valeria was reeling with pain and confusion. All her patterns were scattered, her magic trying to shake itself to pieces.

The child’s own confusion and the shock of birthing drove her toward her mother—like calling to like. Kerrec throttled down panic. Now of all times, he must be what he was bred and trained to be.

He breathed deep and slow, as he willed Valeria to do, and quieted his mind and heart and the rushing of blood through his veins. As he grew calmer, the patterns around them lost their jagged edges and smoothed into the curves and planes of a world restored to order. For strength he drew from the earth, from the Mountain itself that was the source of every rider’s magic.

The stallions were there, and their great Ladies behind them, watching and waiting. Kerrec was bound in body and soul to the stallion Petra, whose awareness was always with him. But this was a greater thing.

He had never sensed them all before. Sometimes he had seen them through Valeria’s eyes and known for an instant how powerful her magic was. She could see and feel them all, always.

This was not a shadow seen through another’s eyes. It was stronger, deeper.

The white gods had drawn aside the veil that divided them from mortal minds and magic. None of them moved, and yet this was a Dance—a Dance of new life and new magic coming into the world.

Kerrec dared not pause for awe. The gods might be present and they might be watching, but they laid on him the burden of keeping his lover and his child alive. They would do nothing to help him.

It did no good to be bitter. The gods were the gods. They did as they saw fit.

Under that incalculable scrutiny, he held the patterns steady. The pains were close together now. Valeria gasped in rhythm with them. She spoke no word, nor did she scream. She took the pain inside herself.

Morag moved into Kerrec’s vision. He had all but forgotten her, lost in a mist of magic and fear.

“I need you to hold her tightly,” Morag said, “but don’t choke the breath out of her.” She placed his hands as she would have them, palms flat below the breasts, pressed to the first curve of the swollen belly. “When I give the word, push.”

Kerrec drew a breath and nodded. His legs were stiff and his back ached with sitting immobile, cradling Valeria. He let the discomfort sharpen his focus.

Morag’s voice brought him to attention. “Now,” she said. “Push.”

Valeria began to struggle. She was naked and slicked with sweat, impossibly slippery in Kerrec’s hands. He locked his arms around her and prayed they would hold.

Morag slapped Valeria, hard. The struggling stopped. Valeria was conscious, if confused.

“Now push,” Morag said to them both.

Valeria braced against Kerrec’s hands. He held on for all their lives and pushed as Morag had instructed.

For the first time in the whole of that ordeal, Valeria let out a sound, a long, breathless cry. Kerrec felt the pain rising to a crescendo, then the sudden, powerful release. Valeria’s cry faded into another altogether, a full-throated wail.

“Her name is Grania,” Valeria said.

She was exhausted almost beyond sense, but she was alive, conscious and far from unmade. The Unmaking had subsided once more, sinking out of sight but not ever again out of mind.

Morag and two servants of the school had bathed Valeria and dressed her in a soft, light robe. Two more servants had spread clean bedding, cool and sweet-scented. Valeria lay almost in comfort and held out her hands.

Kerrec cradled their daughter, looking down into that tiny, red, pinched face, as rapt as if there had never been anything more beautiful in the world. He gave her up with visible reluctance.

“Grania,” Valeria said as the swaddled bundle settled into her arms. Maybe the child would be beautiful someday, but it was a singularly unprepossessing thing just now. She folded back the blankets, freeing arms that moved aimlessly and legs that kicked without purpose except to learn the ways of this new and enormous world.

Valeria brushed her lips across the damp black curls, breathing the warm and strange-familiar scent. “Grania,” she said again. And a third time, to complete the binding. “Grania.”

She looked up. Morag was smiling—so rare as to be unheard of. Grania had been her mother’s name. It was an honor and a tribute.

Valeria was too tired to smile back. Kerrec sat on the bed beside her. She leaned against him as she had for so many long hours. As he had then, he bolstered her with his warm strength.

She sighed and closed her eyes. Sleep eluded her, but it was good to rest in her lover’s arms with their child safe and alive and replete with the first milk.

Her body felt as if it had been in a battle. Everything from breasts to belly ached. That would pass. The Unmaking…

Despair tried to rise and swallow her. She refused to let it. She should be happy. She would be happy. That old mistake would not crush her—not now and not, gods willing, ever after.

Chapter Six

The room was full of shadows and whispers. All the windows were shrouded and the walls closed in with heavy dark hangings. But the floor was bare stone, and a stone altar stood in the center, its grey bulk stained with glistening darkness.

Maurus struggled not to sneeze. He was crowded into a niche with his cousin Vincentius. They each had a slit to peer through, which so far had shown them nothing but the altar and the lamp that flickered above it.

Nothing was going to happen tonight. Vincentius had heard wrong—there was no gathering. They had come here for nothing.

Just as Maurus opened his mouth to say so, he heard what he had been waiting for.

Footsteps, advancing deliberately, like the march of a processional. Maurus’ heart pounded in his throat.

The door opened behind the heavy sway of curtains. Maurus stopped breathing. Vincentius’s face was just visible beside him, pale and stiff. His eyes were open as wide as they would go.

This was the gathering they had come to see. When the full number had come through the door and drawn up in a circle around the altar, there were nineteen of them.

They were wrapped in dark mantles. Some hunched over as if trying to be furtive. Others stood straight but kept their cloaks wound tight.

Vincentius thrust an elbow into Maurus’ ribs. Maurus had already seen what his chin was pointing at. One of the figures nearest them had a familiar hitch in his gait.

Maurus’ brother Bellinus had been born with one leg shorter than the other. It made no apparent difference on a horse and he had not been judged unfit to inherit their father’s dukedom, but lately he had been acting odd—bitter, angry, as if he had a grievance against the world.

Maurus bit his lip to keep from making a sound and tried to breathe silently. Vincentius’ breath was loud in his ears. Any moment he expected one of the people in the circle to come looking for either or both of them.

The circle turned inward on itself. The air began to feel inexplicably heavy. Maurus’ head ached and his ears felt ready to burst.

Out of that heaviness grew a deep sound, deeper than the lowest note of an organ, like the grinding of vast stones under the earth. The floor was steady underfoot, but far down below it, Maurus thought something was stirring, something he never wanted to see in the daylight.

The circle moved, drawing together. Blades flashed in unison. Each shrouded figure bared an arm and cut swiftly across it. Blood flowed onto the already glistening stone.

Those arms were scarred with knife cuts healed and half-healed and barely scabbed over. It was true, then, what Maurus had heard. These worshippers of the unspeakable had been meeting nearly every night to make sacrifice in blood.

No one had been able to say what that sacrifice was for. Something dark was all Maurus could be sure of.

He had imagined that he could do something to save his brother from whatever it was. But hiding behind the curtain, huddled with his friend whose elder brother was also somewhere in the circle, Maurus felt the weight of despair. He was a half-grown boy with a small gift of magic. He should never have come to this place or seen what he was seeing.

The sound from within the earth grew deeper still, setting in his bones. Blood congealed on the altar. The circle began to chant.

It was all men’s voices, but they sang a descant to the earth’s rumbling. The words were not in a language Maurus knew. They sounded very old and very dark and very powerful.

They tried to creep into his mind. He pressed his hands to his ears. That barely muffled the sound, but the words blurred just enough that he could, more or less, block them out.

His skin crawled. His head felt as if he had been breathing poison. He was dizzy and sick, trying desperately not to gag or choke.

It all burst at once with a soundless roar. The earth stopped throbbing. The chant fell silent.

Above the altar with its thick shell of clotted blood, the air turned itself inside out. Maurus’ eyes tried to do the same. He squeezed them shut.

He could still see the flash of everything that was the opposite of light, of nothingness opening on oblivion. As terrified as he was, he needed to see it clearly—to know what it was. He opened his eyes, shuddering so hard he could barely stand up.

Oblivion spawned a shape. Arms and legs, broad shoulders, a head—it was a man, naked and blue as if with cold. He fell to hands and knees on the altar.

Lank fair hair straggled over his shoulders and down his back. He was so gaunt Maurus could see every bone, but there was a terrible strength in him. He raised his head.

His eyes were like a blind man’s, so pale they were nearly white. But as he turned his head, thin nostrils flaring, he made it clear that he could see. He took in the circle and the room and, oh gods, the curtains that shrouded the walls.

He must be able to see the boys hiding there. Maurus tried to melt into the wall. If there had been a way to become nonexistent, he would have done it.

The strange eyes passed on by. The pale man stepped down from the altar. He was tall, and seemed taller because he was so thin. One of the men who had summoned him held out a dark bundle that unfolded into a hooded robe.

That face and that lank hair were all the paler once the body was wrapped in black wool. The voice was surprisingly light, as if the edges had been smoothed from it. “Where is it?” he asked. “It’s in none of you here. Where are you hiding it?”

“Hiding what, my lord?” asked one of the men from the circle.

The pale man turned slowly. “Don’t play the fool. Your little ritual didn’t bring me here. Where is the maw of the One?”

The man who had spoken spread his hands. “My lord, all we are is what you see. We summoned you by the rites that were given us by—”

“Empty flummery,” the pale man said. “Great power called me. Your blood showed me the way. Now feed me, because I hunger. Then tell me what you think you can do to bring the One into this place of gods and magic.”

“We trust in you, my lord,” said the other. “The message said—”

“I was promised allies with intelligence and influence,” the pale man said. “I see a pack of trembling fools. That’s comforting in its way, I do grant you. If you’re such idiots, those we want to destroy might even be worse.”

“My lord—” said the spokesman.

The pale man bared long pale-yellow teeth. “This game we play to the end—ours or theirs. We’ve failed in the Dance and we’ve lost in battle. This time we strike for the heart.”

A growl ran around the circle, a low rumble of affirmation. Obviously they took no offense at anything this creature might say.

The creature swayed. “I must eat,” he said. “Then rest. Then plan.”

“Of course, my lord,” the spokesman said hastily. He beckoned. The circle closed around the pale man. It lifted him and carried him away.

Maurus swallowed bile. The stink of blood and twisted magic made him ill. He was afraid he knew what they had been talking about—and it brought him close to panic when he thought of his brother caught up in such a thing.

There had been other plots against the empire. The emperor had been poisoned and the Dance of his jubilee broken, with riders killed and the school on the Mountain irreparably damaged. Then in the next year the emperor had gone to war against the barbarian tribes whose princes had conspired to break his Dance. With help from two of the riders and the gods they served, he had destroyed them—but their magic had destroyed him.

Now his daughter was shortly to take the throne as empress. There would be a coronation Dance. Surely the riders who came for that, along with every mage and loyal noble in the city of Aurelia, would be on guard against attack.

Which meant—

Maurus did not know what it meant. Not really. He did know that his brother was caught up in it, and that was terrible enough.

Vincentius slid down the wall beside him. His face was the color of cheese.

He always had been a sensitive soul. Maurus pulled him upright and shook him until he stood on his own feet again.

The worshippers of the One had gone. The corridor was silent. The lamp guttered over the altar.

Maurus dragged Vincentius with him around the edge of the room—as if it made any difference now how furtive they were—and peered around the door. The passage was deserted as he had thought.

It was almost pitch-black. The lamps that had been lit along it had all gone out. Only the one at the farthest end still burned, shedding just enough light to catch anything that might have stirred in the darkness.

Maurus eyed the light over the altar, which was burning dangerously low. He was not about to climb on that blood-slicked stone to retrieve the lamp. He would have to brave the dark, and hope no one came back while he did it.

Vincentius had his feet under him now. He could walk, though he had to stop once and then again to empty his stomach.

That might betray them, but there was nothing Maurus could do about it. He dragged his cousin forward with as much speed as he could. His mind was a babble of prayer to any god that would hear.

Halfway down the corridor, something scraped at the door. Maurus froze. Vincentius dropped to his knees, heaving yet again, but this time nothing came up.

There was nowhere to hide. Maurus pressed against the wall—as if that would help—and bit his lip to keep from making a sound.

The scraping stopped. Maurus waited for what seemed an age, but the door stayed shut.

There was no one on the other side. The stairway leading steeply upward was better lit but equally deserted.

Maurus stopped at the bottom and took a breath. There was no escape on that ascent. If he was caught, he could be killed.

The men who kept this secret would not care that he was noble born, only that he had spied on their hidden rite. He set his foot on the first step and began the ascent. Vincentius was already on the stair.

Maurus followed as quickly as he could. His heart was beating so hard he could not hear anything else.

He had not been nearly as afraid in the dungeon below. That had been plain insanity. This was the edge of escape. If he failed, the disappointment would be deadly.

Vincentius reached the door first. His hands tugged at the bolt. The door stayed firmly shut.

Maurus’ terror came out in a rush of breath. He pushed Vincentius aside and heaved as hard as he could.

The door flew open. Maurus nearly fell backward down the stair.

Vincentius caught him. The eyes that stared into his were blessedly aware. They dragged one another through the doorway and into a perfectly ordinary alleyway in the city of Aurelia.

The sun was up. They had been all night in the dark below. People would be looking for them.

“Let’s go to Riders’ Hall,” Vincentius said, putting in words what Maurus was thinking. “We’ll say we thought one of the mares was foaling. Maybe she did. If we’re lucky.”

Maurus nodded. “I wish Valeria was there. Or even—you know—him. They’d know what to do.”

“Riders will be there soon—a whole pack of them. Coronation’s in less than a month. They must be on their way from the Mountain by now.”

“But,” said Maurus, “what if that’s the plot—to stop the Dance again? Or if it’s supposed to come off before they get here? Or—”

Vincentius looked as desperate as Maurus felt. “I don’t know. This wasn’t even my idea. Didn’t you make any plans for after?”

“I just wanted to see what Bellinus was doing,” Maurus said. “I thought I’d corner him later and make him stop. Even though I knew, from what I’d heard, that nobody can do that. The only way out is to die.”

“What about us, then? Do we even dare to tell? We don’t know what they’ll try to do. Mages must be spying, too. Someone must know—someone who can do something about it. They’ll stop it before it goes any further.”

“Are you sure of that?” Maurus said. “Maybe we should go to the empress.”

“Nobody gets near her,” Vincentius said. “Even if we could, what would we say? I thought I recognized some of the voices. That’s all well and good, but if I give any of them up, how do we know they won’t lead the hunters to your brother?”

Maurus’ head hurt. The only clear path he could see still led toward Valeria. She had taught him to ride last year before she ran off to save the world, she and the First Rider who had been born an imperial prince.

Valeria was the strongest mage he knew, and one of the few he trusted. She would know what to do.

What if she did not come with the riders to the Dance? Would they even let her off the Mountain after all she had done?

He would have to reach her somehow. A letter would be too slow. He did not have the rank or station, let alone the coin, to send a courier all the way to the Mountain.

He would find a way. Then she would tell him what to do. Valeria always knew what to do—or else her stallion did. He was a god, after all.

Maurus set off down the street as if he had every right to be there. Vincentius, who was much taller, still had to stretch to keep up. By the time they reached the turning onto the wider street, where people were up and about in the bright summer morning, Maurus felt almost like himself again.

Chapter Seven

The school on the Mountain was in a flurry. For the second time since Valeria came to it, the best of its riders and the most powerful of its stallions were leaving its sanctuary and riding to the imperial city.

That was a rare occurrence. Considering how badly the last such riding had ended, it was no wonder the mood in the school was complicated to say the least. Nor did it help that by ancient tradition the coronation must take place on the day of Midsummer—and therefore the strongest riders and the most powerful stallions would not be on the Mountain when this year’s Called were gathered and tested.

They had to go. One of their most sacred duties was to Dance the fate of a new emperor or empress. They could no more refuse than they could abandon the stallions on whom their magic depended.

And yet what passed for wisdom would have kept them walled up on the Mountain, protected against any assault. Nothing could touch them here. The gods themselves would see to that.

The Master had settled on a compromise. Half of the First Riders and most of the Second and all of the Third and Fourth Riders would stay in the school. Sixteen First and Second Riders and sixteen stallions would go to Aurelia.

Valeria went as servant and student for the journey. Then in Aurelia she would stay after the Dance was done, under Kerrec’s command.

They were going to try something new and possibly dangerous. But Kerrec had convinced the Master that it might save them all.

He was going to extend the school to Aurelia and bring a part of it away from the fabled isolation of the Mountain into the heart of the empire. If their magic could stand the glare of day and the tumult of crowds, it might have a chance to continue, maybe even to grow.

It needed to do that. It was stiffening into immobility where it was.

In the world outside its sanctuary, all too many people had decided the horse magic had no purpose. Augurs could read omens without the need to study the patterns of a troupe of horsemen riding on sand. Soothsayers could foretell the future, and who knew? Maybe one or more orders of mages could try to shape that future, once the riders let go their stranglehold on that branch of magic.

Valeria happened to be studying the patterns of sun and shadow on the floor of her room as she reflected on time, fate and the future of the school she had fought so hard to join. The only sound was the baby’s sucking and an occasional soft gurgle.

The nurse sat by the window. Her smooth dark head bent over the small black-curled one. Her expression was soft, her eyelids lowered.

Valeria’s own breasts had finally stopped aching. After the first day there had never been enough milk for the baby, but what feeble trickle there was had persistently refused to dry up.

However much she loathed to do it, she had had to admit that her mother was right. She needed the nurse.

The woman was quiet at least. She never hinted with face or movement that she thought Valeria was a failure. She did not offer sympathy, either, or any sign of pity.

“It’s nature’s way,” Morag had said by the third day after Grania was born. The baby would not stop crying. When she tried to suck, she only screamed the louder. Yet again, the nurse had had to take her and feed her, because Valeria’s milk was not enough.

“Sometimes it happens,” Morag said. “You see it with mares, too, in the first foaling, and heifers and young ewes. They deliver the young well enough, but their bodies don’t stretch to feeding it. You’d put a foal or a calf with a nurse. What’s so terrible about doing it with a baby?”

“I should be able to,” Valeria said, all but spitting the words. “There’s nothing wrong with me. You said. The Healers said. I shouldn’t be this way!”

“But you are,” her mother said bluntly. “Stop fighting it, girl, and live with it. There’s plenty of mothering to do outside of keeping her belly filled.”

“Not at the moment there isn’t,” Valeria said through clenched teeth.

“Certainly there is,” said Morag. “Now give yourself a rest while she eats. You’re still weak, though you think you can hide it.”

Valeria had snarled at her, but there was never any use in resisting Morag. The one time she had succeeded, she had had the Mountain’s Call to strengthen her.

The call of mother to child was not as strong as that—however hard it was to accept. She had bound her aching breasts and taken the medicines her mother fed her, and day by day she had got her strength back.

Now, almost a month after Grania was born, Valeria was nearly herself again. She had even been allowed to ride, though Morag had ordered her to keep it slow and not try any leaps. She might have done it regardless, just to spite her mother, but none of the stallions would hear of it.

They were worse than Morag. They carried her as if she were made of glass, and smoothed their paces so flawlessly that she was ready to scream.

“I like the big, booming gaits!” she had shouted at Sabata one thoroughly exasperating morning. “Stop creeping about. It’s making me crazy. I keep wanting to get behind you and push.”

Time was when Sabata would have bucked her off for saying such things. But he barely hunched his back. He did, mercifully, stretch his stride a little.

It was better than nothing. After a while even he grew tired of that and relaxed into something much closer to his normal paces. Valeria was distressed by how hard she had to work to manage those. Childbearing wrought havoc with a woman’s riding muscles.

On this clear summer morning, several days after her outburst to Sabata, she was done picking at her breakfast. Grania was still engrossed in hers.

It was hard to rouse herself to leave them, but each day it grew a little easier. The stallions were waiting. There were belongings to pack and affairs to settle. Tomorrow they would leave for Aurelia.