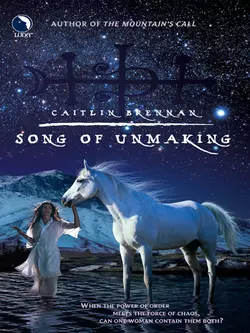

Song Of Unmaking

Caitlin Brennan

Striving to save the Aurelian Empire, Valeria reached for too much power too quickly and a darkness rooted inside her.Unable to confess the truth, Valeria turns to Kerrec, her former mentor, one of the elite Riders from the Mountain, home of the gods. But Kerrec, too, is deeply wounded and his darkness may be even deeper than hers–and he is refusing to face it. Until his weakness nearly destroys the Riders and their immortal white stallions…As Kerrec is sent from the Mountain on a desperate quest for healing, Valeria is forbidden to follow. But compelled by a power she cannot understand and encouraged by her own stallion, she shadows Kerrec on a perilous mission.The patterns of deception and secrets have been woven, the threats of war and unrest spread throughout the land, the barbarian hordes return and once more it is Valeria–and Kerrec–who must gather their strength and wounded magic to protect all that they believe in…. But who will believe in them?

SELECTED PRAISE FOR

THE MOUNTAIN’S CALL

“Definitely a don’t-put-this-down page-turner!”

—New York Times bestselling author Mercedes Lackey

“A riveting plot, complex characters, beautiful descriptions, and heaps of magic.”

—Romance Reviews Today

“Caitlin Brennan has created a masterpiece of legend and lore with her first novel. Hauntingly beautiful and extremely powerful…Take Tolkien and Lackey and mix them together and you get this new magic that is Caitlin’s own. You will stay enthralled with each page turned.”

—The Best Reviews

“Caitlin Brennan is a fantastic world builder who creates a world where magic is an everyday occurrence…. There is plenty of action and romance in this spellbinding romantic fantasy.”

—Paranormal Romance Reviews

CAITLIN BRENNAN

SONG OF UNMAKING

For Shenny

Maybe now your friends will believe

that your aunt writes books!

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

One

The sky was raining stars.

Euan Rohe lay in the frozen sedge. The river gleamed below, solid with ice from bank to bank. The brighter stars reflected in it as they fell, streaks of gold and white and pallid green.

He was dizzy with cold and hunger and long running—and there were the damned imperials, yet again, between him and his hope of escape. Though winter had set in early and hard, the border was crawling with them. Every ford, every possible crossing was guarded.

For days Euan had been struggling along the river, while the hunting grew more and more scant, and the cold set in deep and hard. He was ready to swear that the emperor’s patrols were waiting for him, even herding him, driving him farther and farther downriver. His own country seemed to mock him, rising in steep slopes black with pine and white with snow, so near he could almost reach out and touch, but impossibly far.

He could appreciate irony. He had come out of the heart of the empire, a big redheaded man in a world of little dark people, with a price on his head and a cry of treason that echoed still, months after his stroke against the emperor had failed—and none of the emperor’s hounds had been able to find him. But then, why would they trouble themselves? All they had to do was close the border.

He was trapped like a bear in a pit. They would herd him all the way down to the sea, then corner him on the sand—or they would catch him much sooner, when cold and starvation and sheer snarling frustration made him drop his guard.

Maybe he would die and cheat them of their revenge. They could do what they liked with his corpse—he would not be using it any longer. Even soft imperials might turn savage toward the man who had reduced their emperor to impotence, disrupted their holy Dance, and come near to destroying their herd of horse mages.

His lips drew back from his teeth when he thought of those stiff-necked fools with their overweening arrogance and their worship of fat white horses. At least six of them were dead, and good riddance, too.

One of them was still alive, and that might be good, or it might be very, very bad. If he closed his eyes, he could see her face. Its lines were burned in his memory, just as he had seen her in that last, desperate meeting. Black hair in tousled curls, smooth rounded cheeks and firm chin, and eyes neither brown nor green, flecked with gold. She was bruised, filthy, staggering, with one arm hanging limp—but she held his life in her one good hand.

She could have killed him. He would have bared his throat for the knife. He could have killed her—and by the One God, truly he should have, because she had betrayed him and broken her word and brought down his plot against her empire.

She had let him go. And he had let her live. Because of her he had failed, but also because of her, he had escaped.

That might have been no mercy. He had won through to the border, but the border was closed. The emperor’s legionaries would do her killing for her.

Twenty of them camped now between him and the river. He was not getting across tonight.

His belly griped with hunger. He did his best to ignore it. There were no villages or farmsteads within a day’s hard slog—more than that for a man as worn down as he was. The last rabbit he had managed to snare was long since eaten, down to the hide and sinew. He would be starting in on his boots next, unless he went mad and tried to raid the patrol’s stores.

Maybe that was not so mad. Most of the patrol were asleep. Their sentries were vigilant—and well hidden—but he knew where each of them was.

There was a light in the captain’s tent, but no movement. Probably the man had fallen asleep over his dispatches.

Euan gathered what strength he had. He had to do it soon or he would freeze where he lay. Slip in, snatch what he could, slip out and across the river. He could do that.

He could die, too, but he would die if he stayed where he was. Die doing something or die doing nothing—that was not a choice he found difficult.

He flexed his stiffened fingers and rose to a crouch. He had to stop then until the world stopped spinning. He drew deep breaths, though the air burned his lungs with cold.

When he was as steady as he was going to get, he crept forward through the sedge. The moonlight was very bright and its color was strange—as if the moon had turned to fire.

The hairs of his nape stood on end. He flung himself flat, just as the fire came down.

It struck with a roar that consumed everything there was. The earth heaved under him. A blast of heat shocked him, then a squall of scalding rain. He gagged on the reek of hot metal.

He lay blinded, deafened, and soaked through all his layers of rags and leather and furs. His skin stung with burns. For a long while he simply lay, clinging to the earth that had gone mercifully still again.

He suspected that he might be dead. Every account of the One God’s hell told of fire and darkness, heat and cold together, and the screams of the damned rising to such a pitch that the ears were pummeled into silence.

If he was dead, then the dead could feel bodily pain. Shakily he lifted himself to his elbows.

The sky was still raining stars. The river’s gleam was dulled—spattered with earth and mud and fragments that must be ash. The camp was a smoldering ruin.

All the horses were dead or dying, and the men were down in the ashes of their tents, writhing in agony or else terribly still. Even Euan’s dulled ears could hear the screams of the wounded—and from the sound, those wounds were mortal. The tents were shredded or, on the upriver side, completely gone. The earth gaped where they had been.

Euan’s clothes had been a mass of tatters even before the fire came down. What was fabric was scorched and what was fur was singed, but most of it was intact. Snow and sedge between them had protected him.

He bowed to the strength of the One God who had hurled a star out of the sky to defend His worshipper. He only had to hope that there was enough of him left to make it across the river—and enough provisions left in the camp to feed him before he went.

If nothing else, he could feast on horse meat. There would be a certain pleasure in that, considering how the imperials worshipped the beasts. He staggered erect and made his wobbling way down the hill to the remains of the camp.

None of the legionaries had escaped. Those few who had not died outright, Euan put out of their misery.

The stink of roasted meat made his stomach churn. When he sliced off a bit from a horse’s haunch, he found he could not eat it. He put it away thriftily in his traveling bag, then tried to forget he had it.

There was bread in the ashes of one of the fires on the camp’s edge. It was well baked and savory—a miracle of sorts. He disciplined himself to eat it in small bites, well spaced apart to spare his too long deprived stomach, as he prowled the ruins.

The blasted pit was still smoldering. Every grain of sense shouted at him to stay far away, but he could not make himself listen. It was as if a spell drew him to the place where the star had fallen.

Amid the embers and ash in the heart of the pit, something gleamed. It was absolute stupidity, but he found a way down the crumbling sides into the new-made and intoxicatingly warm bowl.

The star lay in the center in a bed of ash. In spite of the light he had seen, it was dark, lumpen and unlovely, an irregular black stone half the size of his clenched fist.

The heat of its fall was still in it. He had a firepot, stolen from a trader outside a town whose name he had never troubled to learn, and it was just large enough to hold the starstone.

The thing was shockingly heavy. He almost dropped the pot, but he caught it just in time. The weight of the heavens was in it.

It was much harder to climb out of the pit than it had been to go down into it. The sides were steep and slippery with mud and melting ice. Euan came dangerously close to surrendering—to sliding back to the bottom and lying there until death or daylight took him.

In the end it was not courage that got him out. It was pride. However he wanted to be remembered, it was not as the prince of the Calletani who gave up and died in a hole.

He lay on the edge, plastered with mud and gasping for breath. He had no memory of the climb, but his arms and legs were aching and his fingers stung.

Gingerly he rolled onto his back. The stars had stopped falling.

The one in his bag weighed him down as he rose. Wisdom might have persuaded him to drop it, but he had paid too dearly for it already. He stood as straight as he could under it.

There was still food to find and a river to cross. He scavenged a bag of flour that had been shielded by a legionary’s body, a wheel of cheese that was only half melted, two more loaves of bread that had been baking under stones and so were preserved from destruction, and a jar of thick, sweet imperial wine. There was more, but all the horses were dead and that was as much as he could carry.

He stopped to eat a little bread and nibble a bit of cheese. Near where he was sitting, the captain’s tent still stood, scorched but upright. The captain had come out when the fire fell—his body lay sprawled in front of the flap, crisped and charred, with the marks of rank still gleaming on his coat.

Inside the tent, something moved.

Euan sat perfectly still. It was only the wind. But if that was so, then the wind blew nowhere else. The night was calm. Even the moon seemed to be holding its breath.

A shape rose up out of the ashes. It was clothed in a glimmering garment, like something spun out of moonlight. When it stood upright, it stretched long arms and groaned, shaking off a scattering of ash and cooling embers.

The shimmer tore and slid away like the caul from a newborn calf. A man stood in the ashes, whole and unharmed, fixing glittering eyes on Euan. “You’re late,” he said.

Two

Euan was not often speechless. He did not often find himself face to face with a man he had never expected to meet in this of all places, either—still less a man who should have been dead a dozen times over.

“Gothard,” he said. His tone was as cold as the air. “There was a meeting? I must have missed the messenger.”

His sometime ally and cordial enemy looked him up and down with that particular flavor of arrogance which marked an imperial noble. By blood and looks he was only half of one, but his spirit did nothing by halves. “One of the patrols should have captured you days ago. How did you manage to escape?”

“Apologies,” said Euan, dry as dust. “Clearly I failed to do my duty—whatever that was.”

Gothard was barely listening, which did not surprise Euan in the least. “Every stone I scried showed the same thing—you in the legions’ hands, ready to be taken back to Aurelia for trial and inevitable execution. And yet you eluded them all. That’s interesting. Very.”

“I’m sure,” said Euan. He rose carefully, and not only because he was still weak. He did not trust this man at all. “I take it you weren’t a captive, either? Don’t tell me you’ve got the legions in your pay. That’s a fair trick, considering what you tried to do to their emperor.”

Who, he did not add, happened to be Gothard’s father. That particular family quarrel served Euan well. He was not about to take issue with it.

Gothard’s lip twisted. “Clearly you don’t understand how easy it is to get possession of legionaries’ gear if you happen to have allies in the ranks. Those were my men. I don’t suppose you’ve found any of them alive?”

“None who would want to stay that way,” Euan said. “Was that your star? Did you call it down?”

“Would I had such power,” Gothard said with an edge of honest envy. “This is a stroke of the gods. It cost me twenty men—but it gained me you. Maybe you’ll prove to be worth the exchange.”

Euan’s lips drew back from his teeth. “What makes you think I want anything to do with you?”

Gothard’s grin was just as feral and just as empty of humor. “Of course you do. I’m your kinsman—and I know the empire well. You can use me, just as I can use you.”

“I’m not taking you across the river,” Euan said. “You’re a traitor to your kin already. I doubt you’ll be any different on the other side of the border.”

“You know what I want,” Gothard said.

“You wanted to be emperor,” said Euan. “Now that’s failed. What’s next? A plot against the high king?”

“I don’t want to be king of the tribes,” Gothard said. “I’ll leave that for you. I want the throne of Aurelia, just as I always have. We haven’t failed, cousin. We’ve merely suffered a setback.”

Euan threw back his head and laughed until he choked. “A setback? All our men dead, the emperor not only alive but well, and the two of us hunted with every resource the empire can command—I call that a crashing defeat.”

“Do you?” said Gothard. “The emperor’s alive but not entirely well, the hunt has not succeeded in finding, let alone capturing either of us, and the empire’s magic is wounded to the heart. Do you know what it means that half a dozen horse mages are dead? They still have their Master, but only one other of the highest rank still lives, and I broke him before the Dance began.”

“Then he took your magic stone and drove you out,” Euan said. “That’s not as broken as I might like.”

Gothard’s face flushed dark in the moonlight, but he did not give way to his fit of temper. “Yes, I underestimated him, and that was a mistake. But that won’t give back what I took away. His powers are in shards. Maybe he’ll be of some use as a riding master, but as a master of the white gods’ art, he’s done for. And so, for all useful purposes, are the horse mages. They’ll be years gaining back even a portion of what they lost.”

“I do hope you’re right,” Euan said, “because there’s a war coming, and now we have an enemy who’s not just defending his lands against invasion. He’s out for vengeance.”

“All the better for us,” said Gothard. “Anger blinds a man—as I know better than any.”

“So you do,” said Euan sweetly. He turned on his heel. It was a somewhat longer way to the river than if he walked by Gothard, but he was not eager to risk a blade in the belly.

Unfortunately for his hopes of escape, he was much weaker than he wanted to be—and Gothard was well fed and armed with magic. His hand gripped Euan’s arm and spun him back. Euan struck it aside with force enough to make Gothard hiss with pain, but the moment for escape had passed. He was not going anywhere until this was over.

“Suppose I take you with me,” he said. “What’s our bargain? You help me become high king and I help you become emperor? What guarantee does either of us have that we’ll get what we wish for?”

“There are few certainties in life,” Gothard said. “Don’t you love a good gamble? There’s a crown for you and a throne for me, and power enough for the two of us. Or we’re both dead and probably damned.”

“I can’t say I dislike those odds,” Euan said. “Come on, then. Take what you need and follow. I want to be well away from the river by sunup.”

“In a moment,” Gothard said. “Wait here.”

Euan considered telling him what he could do with his damned arrogance, or better yet, walking away while Gothard did whatever he had taken it into his head to do. But curiosity held Euan where he was—and weakness, if he was honest with himself. The heat of the star’s fall was nearly gone. The cold was sinking into his bones.

Gothard strode directly toward the pit where the star had fallen. Euan knew what he was looking for. He was a mage of stones, after all, and the star was a stone.

It weighed heavier than ever in Euan’s traveling bag. A hunted renegade, stripped of his warband, needed every scrap of hope or glory that he could get his hands on if he wanted to stand up before all the tribes and declare himself fit to be high king. This was a gift from the One, a piece of heaven. It carried tremendous power.

How much more power might it carry if a stone mage wielded it—and if that stone mage was sworn to Euan?

Gothard was a wrathful man and a born traitor, and he was probably mad. But he had powers that Euan could use—if Euan could keep him firmly in hand.

This was a night for taking risks. Euan stood on the edge of the pit and looked down. Gothard was crawling on hands and knees, muttering what might be spells, or more likely curses.

The firepot was cold. The starstone felt as if it had turned to ice. It was so cold it burned Euan’s hand as he held it up. “Is this what you’re looking for?”

Gothard’s back straightened. The pale oval of his face turned toward the moon. His eyes glowed like an animal’s.

His voice echoed faintly against the sides of the pit. “Where did you find that?”

“Not far from where you’re standing,” Euan said. “It was hotter than fire then. Now it’s bloody cold.”

“What were you thinking to do with it?”

“Make myself high king,” Euan said.

“Are you a stone mage, then?”

Euan refrained from bridling at his mockery. “No, but you are. What will you give in return for this?”

“What do you want?” Gothard asked. “We’ve already bargained for the high kingship.”

“Now I’m assured of it,” said Euan. “Wield your powers for me. Help me win the war that’s coming. Then we’ll talk about the empire we’re going to take.”

“All with a single stone,” Gothard said, but Euan could hear the yearning in him.

Euan could feel the power in the stone, too, though thank the One, he had no magic to work with it. His soul was clean of that.

“This is a star,” he said. “There’s nothing stronger for your kind, is there? I see it in your eyes. You’ve never lusted for a woman the way you lust for this. This is every bit of magic you lost when your brother took your master stone—and as much again, and more that I’m no doubt too feebleminded to comprehend. I want my share of it, cousin. Swear by it—swear you’ll wield it in my cause.”

“I swear,” Gothard said. His eyes were on the stone.

It was growing warmer in Euan’s hand, or else his fingers were too numb to tell the difference. It seemed both heavier and lighter.

Its power was changing. Gothard was changing it—without even laying a hand on it.

Euan refused to give way to awe. He would use a mage for his purposes, but this was still a half-blood imperial with the taint of treason on him. Gothard would keep his oath exactly as long as it served his purpose, and not a moment longer.

Euan would have to make sure that that was a very long time. He was aching, frozen, dizzy with hunger and exhaustion, but he laughed. He was on his way home, and he was going to be high king.

Three

Euan Rohe walked into his father’s dun a handful of days before the dark of the year. A bitter rain was falling, but the west was clear, a thin line of pale blue beneath the lowering cloud.

The dun was older than the Calletani, a walled fort of rammed earth and weatherworn stone. The wall enclosed a half-ruined tower and a clutter of round houses built like the traveling tents of the people. The king’s house was built around the tower, with his hall in the center. All of it sat on a low hill that rose abruptly out of a long roll of downs.

In milder seasons it was a vast expanse of grass and heather shot through with the silver lines of rivers. Now it was a wilderness of ice and drifted snow, whipped with wind and sleet.

Gothard could have brought them there on the backs of dragons, or conjured chariots out of the air around the starstone. It was Euan who had insisted on taking the hard way on foot over the mountains and through the forests into the heartlands of the Calletani. It was a long road and grueling, but it was honest.

It had also given Gothard ample time to learn the ways and powers of the stone. Euan had no objection to the provender it brought, either the game that walked into his snares or the wine that appeared in his cup. It kept them both alive and walking. It protected them against either discovery or attack, and smoothed their way as much as Euan’s scruples would allow.

“You’re as stubborn as the damned horse-gods,” Gothard had muttered one evening, while a blizzard howled outside the sphere of light and warmth that he had conjured from the stone. “They won’t fly, either. The harder their worshippers struggle, the happier they are.”

“That’s the way of gods,” Euan said.

Gothard had snarled at that, but Euan refused to change his mind. Magic was a dangerous temptation. He would use it if he had to, but he refused to become dependent on it.

They walked, therefore, and Gothard played with the stone, working petty magics and small evils that made him titter to himself when he thought Euan was asleep. Gothard had never been what Euan would call sane, but since he had gotten hold of the starstone, he had been growing steadily worse. He was not quite howling mad, but he was on his way there.

He had been talking to himself for two days when they passed the gates of the dun—a long ramble that Euan had stopped paying attention to within the first hour. Part of him listened for signs of immediate threat, but it all seemed to be focused on the riders and their fat white horse-gods, Gothard’s dearly loathed brother, his even more dearly loathed father, and occasionally the sister whom he direly underestimated. Gothard, in true imperial style, had convinced himself that the females of his kind had neither strength nor intelligence.

At last, under the low and heavy lintel of Dun Eidyn’s gate, he stopped his babbling. There were no guards at the gate, and only a single sentry snoring on the wall above. The two wanderers went not only unchallenged but unnoticed.

Euan resolved to do something about that at his earliest opportunity. Winter it might be, but armies could still march and raiding parties rampage through unprotected camps and ill-guarded duns.

There was no one abroad within the walls. Smoke curled from the roofs of the round houses, and lights glimmered beneath doors and through cracks in shuttered windows. Even the dogs had taken shelter against the storm, which with the coming of dark had changed to sleet.

The door to the king’s house was unbarred, and also unguarded. The guard who should have been there was inside with the rest, in the warmth and the smoky firelight of the hall, finishing the last of the day’s meal and passing jars of wine and skins of ale and mead. The songs had begun, the vaunting that would bring each warrior to his feet with the tale of his own exploits and those of his ancestors for as far back as the rest would let him go.

Euan stood in the shadow of the doorway, letting it sweep over him. Five years he had been away, fighting his father’s war and living as a hostage among the Aurelians. He needed time to believe that he was back at last—and to see what had become of his people in the time since he was gone.

He recognized many of the faces, though some had gone grey and not a few had gained new scars or lost an eye or a limb. Too many were missing, and a surprising number were new—young, most of those. They had been in the children’s house when Euan left, or had come to the tribe as hostages or in marriage alliances.

There were more than he remembered. They filled the circle of the hall, overflowing to the edges. There were more shields and weapons hung on the walls, and a good number of those were bright and new, not yet darkened with smoke or age.

He had feared to find a weakened clan and a faltering people, but these were strong. They were eating well for the dead of winter—the remains of an ox turned on the spit in the center, and the head of a wild boar stood on a spear beside the high seat. The king was wearing its hide for a mantle over a profusion of plaids and a clashing array of golden ornaments.

The old man was gaunt and the heavy plaits of his hair and mustaches had gone snow-white, but his back was still straight and his hand was steady as he drank from a skull-cup. The pale bone was bound with gold and set with chunks of river amber, and the wine inside was as red as blood. It was imperial wine—drinking defiance, the king liked to call it.

He was arrogant enough to leave his dun unguarded and his doors unbarred. Some downy-cheeked stranger was chanting, badly, the lay of a battle Euan himself had fought in. People were already hooting and pounding the tables to make him stop.

Euan raised his voice above the din, drawling the words as if he had all the time in the world. “Now, now, that’s not such a bad vaunt for a stripling. He’s even got his father killing three generals, and there were only two that I remember—and I killed them both. Look, that’s old Aegidius’s skull my father’s drinking from, and there’s the nick where I split it, too.”

While he spoke, he moved out into the light. He knew what he looked like, wrapped in rags and filthy tatters, with ice melting and dripping from his matted beard. He allowed a grin to split it, flashing it over them all, until it came to rest on his father’s face.

It was expressionless, a schooled and royal mask, but the yellow wolf-eyes were glittering. Euan met them steadily. “Good evening, Father,” he said.

The hall had gone silent except for the crackling of flames on the hearth. No one even breathed. Out of the corner of his eye Euan caught the flick of fingers. Someone was trying to expel him as if he were a ghost or a night spirit.

That made him want to laugh, but he held the laughter inside. He had played his hand. The next move was his father’s.

Niall the king studied him for a long while. Euan knew better than to think that slowness was the wine fuddling the old man’s brain. Niall was clearer-headed with a bellyful of wine than most men were cold sober.

At last he said, “So. You made it back. Took you long enough.” He filled the late General Aegidius’s skull to the brim and held it out. “This will warm your bones.”

That was a great honor. Euan bent his head to acknowledge it, but he did not leave the door quite yet. “I brought you a gift,” he said.

He held his breath. Gothard might choose to be difficult—it would be like him. But he came forward at Euan’s gesture.

He was even more rough and wild a figure than Euan, with his mad eyes and his pale, set face. He stank of magic, so strong it caught at the back of Euan’s throat.

“Uncle,” Gothard said in his mincing imperial accent. “I’m pleased to see you well.”

The king did not look pleased, but neither would Euan have said he was displeased. The bastard son of the Aurelian emperor and a Calletani princess was a potent hostage—even without the starstone.

Niall would have to know about that, but not in front of the whole royal clan.

Maybe he caught a whiff of it. Anyone with a nose could. His eyebrows rose, but he asked no questions.

“Nephew,” he said. He beckoned to the servant who stood closest. “Take him, feed him. Give him what he wants to drink.”

Gothard had been disposed of, and he could not fail to know it. Euan did not find it reassuring that he bowed to the king and let the servant take him to a lower table—not terribly low, but not the king’s table, either. A flare of temper would have been more honest, and a blast of magic would have been almost comforting.

Now Euan would have to watch him as well as the rest of them. But then, that had been true from the moment Gothard shed the skin of his magical protection and stood up in the camp he had failed to save. Gothard was no more or less untrustworthy than he had ever been.

For Euan there was a place beside his father and the best cut of the ox that remained. Tomorrow he would be looking out for daggers in the back, but tonight he was the prince again, the king’s heir. He was home.

Four

Euan woke in bed with no memory of having been brought there. He had lasted through four cups of the strong, sweet wine and uncounted rounds of bragging from the king’s warband. They were courting him—eyeing the king’s age and his youth, and reckoning the odds.

The wine was still in him, making his head pound, but he grinned at the heavy beams of the ceiling. He was in the tower, in one of the rooms above the hall—he recognized the carving. Rough shapes of men and beasts ran in a skein along the beam. Like the tower, they were older than his people. He had known them since he was a child.

His face felt different. His hand found a cleanly shaven chin and tidily trimmed mustaches. The rest of him was clean, too, and the knots and mats were out of his hair.

He sat up. He was still bone-thin—no miracles there—but months of crusted dirt were blessedly gone. He was dressed in finely woven breeks, green checked with blue in a weave and a pattern that he knew. The same pattern in rougher and heavier wool marked the blanket that covered him. There was a heavy torque around his neck, and rings swung in his ears and clasped his arms and wrists. He was right royally attired, and every ornament was soft and heavy gold.

He hardly needed to look toward the door to know who stood there, waiting for him to notice her. She was nearly as old as his father, but where age lay on Niall like hoarfrost, on Murna his first wife and queen, it was hardly more than a kiss of autumn chill. Her hair had darkened a bit with the years, but it was still as much gold as red. Her skin was milk-white, her features carved clean, almost too strong for beauty. They were all the more beautiful for that.

She looked like a certain imperial woman—not the coloring, the One God knew, but the shape and cast of her face and the keenness of her moss-green eyes as they studied him. It startled him to realize how like Valeria she was.

Well, he thought, at least his taste was consistent. He let the smile escape. “Mother! You haven’t changed a bit.”

“I would hope not,” she said. “Whereas you—what have you been living on? Grass and rainwater?”

“Near enough,” he said. “I’m home now. You can feed me up to your heart’s content.”

She frowned slightly. “Are you? Are you really home?”

“For good and all,” he said. “I’ll tell you stories when there’s time. I’ve seen the white gods’ Dance, Mother. I’ve brought an empire to its knees. It got up again, staggering and stumbling, but it was a good beginning.”

“All men love to brag,” she said.

“Ah,” said Euan, “but my brags are all true.”

“I’m sure,” she said as if to dismiss his foolishness, but her eyes were smiling. “There’s breakfast when you’re ready. After that, your father will see you. Something about a gift, he said.”

Euan nodded. “You’ll be there for that?”

“Should I be?”

He shrugged. “If it amuses you.”

“It might.”

She left him with a smile to keep him warm, and a parcel that proved to be a shirt and a plaid and a pair of new boots, soft doeskin cut to fit his feet exactly. Someone must have been stitching all night long.

It was bliss to dress in clean clothes, warm and well made and without a rip or a tear to let the wind in. There were weapons, too, the bone-handled dagger that every man of the Calletani carried, the long bow and the heavy boar-spear and the lighter throwing spear and the double-headed axe, and the great sword that was as long as a well-grown child was tall.

He left all but the dagger in their places. The day was dark as he went out, but the sun was well up—somewhere on the other side of the clouds. Last night’s glimmer of clear sky had been a taunt. Snow was falling thick and hard, and wind howled around the tower.

It could howl all it liked. Euan was safe out of its reach.

There was food in the hall, barley bread and the remains of last night’s roast, with a barrel of ale to wash it down. Euan ate and drank just enough to settle his stomach. If he had been playing the game properly, he would have lingered for an hour, bantering with the clansmen who were up and about, but he was still half in the long dream of flight. His feet carried him to the room where the king slept and rested and held private audiences.

It was the same room he remembered. Just before he went away, the trophies of two legions had been brought there. They were still standing against the wall. The armor of the generals, their shields and the standards with their golden wreaths and remembrances of old battles, gleamed as if they had been taken only yesterday.

They struck Euan strangely. For most of five years he had lived in the empire, surrounded by guards in armor very like that. Seeing them, he understood, at last, that he had escaped. He was free.

Maybe it was only a different kind of bondage. His father was sitting in the general’s chair that he had taken with the rest of the trophies. Away from the clan and its eyes and whispers, Niall allowed himself to feel his age. He slumped as if with exhaustion, and his face was drawn and haggard.

He straightened somewhat as Euan came through the door. The gladness in his eyes was quickly hooded.

That might have been simply because other guests had arrived before Euan. Two priests of the One stood in front of the king. Gothard perched on a stool, more or less between them.

Euan tried to breathe shallowly. No matter their age or rank, priests always stank of clotted blood and old graves. These were an old one and a young one, as far as he could tell. They stripped themselves of every scrap of hair, even to the eyelashes—or their rites did it for them—and they were as gaunt as the king and far less clean. Bathing for them was a sin.

The one who might have been older also might have been of high rank. He wore a necklace of infants’ skulls, and armlets pieced together of tiny finger bones. The other’s face and body were ridged with scars, so many and so close together that there was no telling what he had looked like before. Only his hands and feet were untouched, and those were smooth and seemed young. He was very holy, to have offered himself up for so much pain.

Euan’s mother was not in evidence, but there was a curtain behind his father, with a whisper of movement in it. She was there, watching and listening.

He breathed out slowly. Gothard grinned. He had been washed and shaved and made presentable, just as Euan had. Oddly, in breeks and plaid and with his chin shaven but his mustaches left to grow, he looked more like an imperial rather than less. In that country he was taller and fairer and blunter-featured than the rest of his kin. Here, he was a smallish dark man with a sharp, long-nosed face, playing at being one of the Calletani.

He seemed to be enjoying the game. “Don’t worry, cousin,” he said. “I’ve told them all about it. You don’t have to say a thing.”

“Really?” said Euan. “About what?”

“Why,” said Gothard, opening his hand to reveal the starstone, “this.” He flipped it into the air, then caught it, laughing as the priests flinched. “I know you thought we should bring it on gradually, but I think it’s better to have it out in the open. All the better—and sooner—to get where we want to go.”

“And where is that?” Euan inquired.

Gothard’s eyes narrowed. “So you’re going to play stupid? I told them who found it, too. You’re a great giver of gifts, cousin. The stone to me, and me—with the stone—to your father. Your people will love you for it.”

“They’ll love me more when I help them conquer Aurelia,” Euan said. “You are going to do that, yes? You won’t renege?”

“I’ll keep my word,” said Gothard, “as long as you keep yours.”

“We are all men of our word,” the king said. “Tell us again, nephew, what a starstone can do for us besides be an omen for the war.”

“It’s a very good omen,” Gothard said. “So is the fact that it came into the hands of a stone mage. The One is looking after you, uncle. This is going to win your war for you.”

“I hope we can believe that,” said Niall.

“Look,” said Gothard. He held the stone in his cupped hands. It never seemed heavy when he held it, but it was getting darker—Euan did not think he was imagining it. It looked like a piece of sky behind the stars, or a lump of nothingness.

Things were moving in it. They were not shapes—if anything they were shapeless—but they had volition. There was intelligence in them. They groped toward anything that had light or form, and devoured it.

The priests had gone perfectly still. Euan had seen fear before. He was a fighting man. He had caused it more times than he could count. But to see fear in the eyes of priests, who by their nature feared nothing, even death itself—that gave him pause.

Gothard smiled. The movements of the dark things were reflected in his face. His eyelids were lowered. His eyes were almost sleepy. He had an oddly sated look. “Yes,” he said softly. “Oh, yes.”

The stone stirred in his hands. Euan’s eye was not quite fast enough to follow what it did. It did not move, exactly. It reached.

The younger priest had no time to recoil. Formlessness coiled around him. When he opened his mouth to scream, it poured down his throat.

It ate him from the inside out. There was pain—Euan could have no doubt of that. The eyes were the last to go, and the horror in them would haunt him until he died.

When the last of the priest was gone, the thing that had consumed him flowed back into the stone. Gothard’s hands that held it were unharmed. His smile was as bright as ever. “Well?” he said. “Do you like it? We can do it to a whole army if we like, or the whole world. Or just the generals. You only have to choose.”

“The greatest gift of the One is oblivion,” Niall said. “Would you give such a gift to our enemies?”

“Would you give such a gift to your people?”

“It’s a strong thing,” the king said, “and it’s victory. It’s also magic. We don’t traffic with magic here.”

“Even if it will win the war?”

“Some victories are not worth winning.” Niall bent his head slightly. The remaining priest stiffened, but he laid a hand on Gothard’s shoulder.

Euan watched Gothard consider blasting them both. Then evidently he decided to humor them. He let the priest raise him to his feet and lead him away.

For a long while after he was gone, Euan had nothing to say. Niall seemed even more stooped and haggard than he had when Euan came in.

At last the king said, “That’s a troublesome gift you’ve given me.”

“You’re refusing it?”

Niall drew a deep breath. It rasped in ways that Euan did not like. “I’d be a fool to do that. But I don’t have to let it turn on me, either.”

“You know we’re going to have to use him,” Euan said. “Every time the Aurelians have raised armies against us, we’ve won a few skirmishes, even taken out a legion or two—then they’ve won the war. We can out-fight and out-maneuver them, but when they bring in their mages, we have no defense.”

“We have the One,” Niall said. “He exacts a price, but he protects us.”

“The price is damnably high,” said Euan.

“He takes blood and pain and leaves our souls to find their own oblivion. This thing will take them all—down to the last glimmer of existence.”

“Isn’t that what we want?” Euan demanded. “Isn’t the Unmaking our dearest prayer?”

“Not if magic brings it,” his father said. “I thank you for the gift of our kinsman. As a hostage he has considerable worth. For the rest…the One will decide. It’s beyond the likes of me.”

“You are the king of the people,” Euan said. “Nothing should be beyond you.”

“You think so?” said Niall. He seemed amused rather than angry. “You’re young. You have strong dreams. When I’m gone, you’ll take the people where they need to go. Until then, this is my place and this is my decision—however cowardly it may seem to you.”

“Never cowardly,” Euan said. “Whatever else you are, you could never be that.”

Niall shrugged. “I’m what I am. Go now, amuse yourself. It’s a long time until spring.”

Not so long, Euan thought, to get ready for a war that had been brewing since long before either them was born—the war that would bring Aurelia down. But he kept his thoughts to himself. The winter was long enough and he had a great deal of strength to recover. He could forget his worries for a while, and simply let himself be.

But first he had a thing he must do. The women’s rooms were away behind the men’s, well apart from the hall. They were much smaller and darker and more crowded, and they opened on either the kitchens or the long room where the looms stood, threaded with the plaids and war cloaks of the clan.

His mother’s room lay on the other side of the weavers’ hall. He had to walk through the rows of weavers at their looms, aware of their stares and whispers. He was a man in women’s country. He had to pay the toll accordingly.

She was not in the room, but he had not expected her to be. The bed was narrow and a little short, but it was warm and soft. He lay on it and drew up his knees. The smell of her wrapped around him, the clean scent of herbs with an undertone of musk and smoke.

He did not exactly fall asleep. He was aware of the room around him and the voices of women outside, rising over the clacking of the looms.

Still, he was not exactly awake, either. The bed had grown much wider. Someone else was lying with her back to him. Her breathing was deep and regular as if she slept, but her shoulders were tight.

Her skin was smooth, like cream, and more golden than white. Her hair was blue-black, cropped into curls. He ran his hand from her nape down the track of her spine to the sweet curve of her buttocks. She never moved, but her breathing caught.

He followed his hand with kisses. She was breathing more rapidly now. He willed her to turn and look into his face. Her name was on his lips, shaped without sound. Valeria.

Five

“You’re not Amma.”

The voice most definitely was not Valeria’s, nor was it Murna’s. It was a child’s, sharp and imperious.

The golden-skinned lover was gone. Euan’s mother’s bed was as narrow as ever. A child was standing over him, glowering.

It was a young child but long-legged, with a mane of coppery hair imperfectly contained in a plait, and fierce yellow eyes. By the single plait and the half-outgrown breeks, it was male—too young yet for the warriors’ house, but old enough to be well weaned.

Euan shook off the fog of the dream. “I’m not your amma,” he agreed. “I’m waiting for my mother.”

“Wait somewhere else,” the child said. “This is Amma’s room.”

“Not unless she shares it with my mother,” Euan said. His eyes narrowed. “My name is Euan. What is yours?”

“No one’s named me yet,” the child said.

Euan’s brows rose. A child without a name was a child without a father—because it was the father who raised the child before the clan, gave him his name and bound him to the people. This one seemed not to find any shame in it.

“Who is your mother?” Euan asked him.

“Mother’s dead,” the child said. “Where’s the other one?”

“What—”

“The lady. Where did she go?”

Euan’s nape prickled. “You saw her?”

“She’s pretty,” the child said.

“Very pretty,” Euan said a little faintly.

He was beginning to think this was a dream, too. A child of the people who saw the unseen was either fed to the wolves or handed over to the priesthood. Somehow he could not see this bright child as a priest.

He seemed very solid, but then, so had Valeria. Maybe this was all a delusion, some sleight of Gothard’s to trap Euan in the starstone.

If he let his mind run that way, he would turn as mad as Gothard. He sat up and breathed deep. The air smelled and tasted real. The child in front of him did not go away.

He was real, then. So was Euan’s mother, coming up behind him. “Ah, wolfling,” she said, “there you are. Brigid’s looking for you.”

The child shrugged that off. “There’s a man in your bed, Amma.”

“So I see,” Murna said. “Go on now. I’ll find you later and we’ll visit the hound puppies.”

This child was not easily bribed. His jaw set and his eyes narrowed. But Murna had raised many a child. Her own eyes narrowed even more formidably than his.

He was headstrong but he was no fool. He sulked and dragged, but he went where he was told.

The fog was leaving Euan’s wits—and none too soon, either. “I don’t suppose that’s mine,” he said.

“So his mother said.” Murna sat on the stool that stood at the end of the bed.

“Who was she?”

“Her name was Deira from Dun Gralloch,” Murna said. “Her father was—”

“I remember,” Euan said.

That had been another winter before another war. There was a gathering of the clans around Dun Eidyn, to celebrate the dark of the year and plan the spring’s battles. It would be far from Euan’s first battle, but it would be his first war against the empire.

He was full of himself that night, and full of honey mead, too. He looked up from his newly emptied cup to meet a pair of eyes the color of dark amber. Gradually he took in the rest of her, smooth oval face, neatly braided hair the precise color of her eyes, and tall body, well rounded, with deep breasts and broad hips.

When he smiled at her, she did not smile back. She lowered her eyes as a modest woman should do, but she watched him sidelong.

He found her in his bed that night, curled up, asleep. When he touched her, she woke completely. She was older than he was but still a maiden—though he did not know that until after it was done. He did not know her name, either, not for the nine nights she spent in his bed.

They spoke of everything but that—the world and the people in it, the One, the empire, the dreams they had and the life they hoped for. She was the first mortal creature he told of his dearest dream, not only to be high king but to sit in the throne of the emperor in Aurelia. She did not laugh at him, either. She said, “I’ll make you a son to give you strength, and to stand beside you when you take that throne.”

“I’m going to do it,” he said.

“I know you are,” she said. Her eyes were dark in the lamplight, drinking in his face. There was something odd about her expression—not sad, exactly, but somehow wistful.

Then she kissed him and he forgot everything else. Five years after, he remembered little of that night but warmth and laughter and such pleasure as a man could never forget.

Toward dawn, she kissed him one last time, letting it linger, then drew away as she had done at the end of each night. But she paused, bending down again. Her voice was soft in his ear. “Deira,” she said. “My name is Deira.”

He reached for her to keep her with him. He opened his mouth to ask her the rest of it—her father’s name, her clan, everything—but she slipped away. That day the people of Dun Gralloch left the gathering. That night, his bed was empty. Deira was gone.

He meant to find her. But first there was the war, then they lost it, then he was sent as a hostage into Aurelia. He had not forgotten her, but five years was a long time. He would have expected that she had married and borne another man sons—that was what any sensible woman would do.

Now that he knew what had become of her, he surprised himself with grief. Out of it, he said to his mother, “She really is dead? Was it the child?”

Murna shook her head. “There was plague the year after he was born. He lived. She died. Her father sent him to me as her last gift, with a message. Keep him until his father comes for him.”

“Was she dishonored? Was she mistreated? Did—”

“She was treated as well as she had a right to expect,” his mother said. “The child was allowed to live. He was sent to the king’s house for fostering. That’s more than most fathers would do for a daughter who despoiled herself.”

“I would have asked for her as a wife,” Euan said.

“I’m sure you would,” said Murna without expression. “Will you give the child a name, then?”

“Of course I will,” he said. “I’ll do it today.”

That surprised her. He did not see why, but there was no denying it. “Are you sure?”

He frowned. “Why? Is there a reason why I shouldn’t?”

“No,” said Murna. “No reason.”

That was not the truth, but something kept him from challenging her. There would be time later, he told himself. He had come here to ask her advice, not to find a son—and those other matters were pressing.

It was odd how, after all that had happened, even to the unmaking of a priest, Euan remembered little of what he said to his mother or she to him. But he remembered every moment of the exchange with his son.

That was his son—the child of his body. He was as sure of that as he was of his own name and ancestry. He would give the boy a name of his own and the life that went with it, firstborn son of a prince of the Calletani.

Murna brought the boy into the hall after the men had gathered there but before the day’s meal had been spread on the tables. That was the time for petitions and disputes, for men to come to the king with things that needed doing or settling.

Euan had been listening carefully to each one. Some needed his father’s decision, others the warleaders’ or the priests’. As he had when he was young, he committed each to memory.

He did not hold his breath waiting for his mother to bring the child. She might make him send for the boy—and he was prepared to do that.

Late in the proceedings, as two men of the warband argued heatedly over the ownership of a crooked-horned cow, Euan saw his mother standing among the rest of the petitioners. There was a plaid over her head as if she had been a common woman. The child was too small to see among so many grown folk, but Murna looked down once and said something.

Euan did not need that kind of proof. The boy was here. He knew it in his gut.

His heart was racing. For a man to claim a son was a great thing. For a man to do it the day after he had come home from a long exile was greater still. It was like an omen, a promise that his dream would come true.

The petitions that had fascinated him now seemed terribly tedious. There were so many and they were so trivial. If they stretched out much longer, there would be no time.

Just as he was about to rise up and roar his mother’s name, the last petitioner finished his rambling tale and received quick justice from the king. Euan paid no attention. His eyes were on the child, whom at last he could see.

His child. His son. No one could mistake it. There was no sign of his mother in him except for a certain air, a deep and inborn calm. He was long-limbed and rangy like a young wolf, and his eyes were wolf eyes, amber-gold and slanting in the long planes of his face.

He was royal-clan Calletani, like his father and grandfather and all their fathers before them. The One himself had marked him for what he was.

He stood straight beside his grandmother. There was no fear in him, only curiosity. His eyes were wide, taking in everything.

When those eyes fell on Euan, they brightened. He pulled free from his grandmother, who was just beginning to bow in front of the king, and sprang into Euan’s arms.

Euan was as startled as everyone else. The child was heavier than he looked, and strong.

“No need to guess whose litter that cub came from,” someone said.

Euan readied a glare to sweep across the hall, but the child laughed. His mirth was rang out in the silence. Euan swung him onto his shoulder and said so they all could hear, “You guessed right. I’m claiming him. He’s my blood and bone, the wolf-cub of the Calletani. I name him Conor, and bid you all name him likewise.”

The name ran around the room in a low roll of sound. Conor…Conor…Conor.

Euan looked up into the boy’s face. His head was tilted. He was listening hard. When the sound of his name had died down, he nodded. “That’s my name,” he said. “My name is Conor.”

“That was well done,” Gothard said.

Conor was back among the women again. The night’s meal had turned into a celebration, welcoming a new man-child to the clan. Euan staggered out of it, aswim with the last of the wine, to find Gothard squatting in front of the jakes.

He or someone had made a cage of gold wire for the starstone and hung it around his neck. It swung as he rocked, drinking darkness out of the air. “Well done,” he repeated. “Oh, so well done. Show the people you’ve got what a king needs—balls and gall and enough sense to get yourself an heir before it’s too late.”

“I’m glad you approve,” Euan said. He made no effort to sound as if he meant it.

“I only wonder,” Gothard said, rocking and smiling, with the starstone swinging and swinging, “seeing how strongly all the people resist the very idea of magic, how you managed to beget a child who fairly crackles with it.”

Euan had no memory of movement. One moment he was standing on one leg, wondering if he should piss in the bastard’s face to relieve himself and shut him up. The next, his hand was locked around Gothard’s throat.

The stone did not blast him. He found that interesting.

He spoke very carefully, enunciating each word. “My son is not a mage.”

“You know he is,” Gothard said.

Euan’s fingers tightened. Gothard turned a gratifying shade of crimson. “Whatever you think he is,” Euan said, “or think you may turn him into, you will keep your claws off him. If I find even the slightest hint that you have touched him or burdened him with so much as a word, I will flay you alive and bathe you in salt.”

He saw how Gothard’s eyes flickered. His own stayed fixed on that purpling face. “Don’t think your stone will save you. It was mine first. It remembers. And so should you. Hands and magic off my son. Do you understand?”

Gothard’s eyes had begun to bulge. It was a pity, Euan thought, that he needed a stone mage to exploit the full power of the stone. This was the only one he was likely to get. Gothard had to go on breathing—as much as Euan might wish otherwise.

He let Gothard go. Gothard fell over, gagging and choking, wheezing for breath. Euan left him to it.

He could feel Gothard’s eyes on his back as he went into the jakes. The hate in them was strong enough to make his skin twitch.

He shrugged it off. As long as they needed each other, there would be no killing on either side, and no Unmaking, either. After that, the One would provide. It would give Euan great pleasure to finish what he had begun.

Six

The Mountain was singing. It was a deep song, far below the edge of hearing, but it thrummed in Valeria’s bones. When she looked up from the shelter of the citadel toward that jagged peak, gleaming white against the piercing blue of the sky, and heard the great sound that came out of it, she knew a profound and almost unbearable joy.

The Mountain was locked in snow. Winter, like the claws of grief and irretrievable loss, gripped the school as if it would never let go. Yet the sun was just a fraction stronger and the air just a whisper warmer. And the Mountain sent out the Call.

It was strange to hear it and know what it was and feel the power of it, but to be no part of it. She had been Called a year before, and now the Mountain had her. This new compulsion, renewed every spring for a thousand years, was meant for someone else. Many someones, she hoped. The school needed as many new riders as the gods would deign to send.

When the first of the Called came in, she was schooling Sabata in the riding court nearest the southward gate. It was the first day in months that anyone had been able to ride under the sky. The grass around the edges of the court was just beginning to show a glimmer of green.

The raked sand of the arena was a little damp from the winter’s rains, but Sabata moved lightly on it. He liked its softness and its slight springiness.

In fact he was moving a little too lightly. He was fresh and not particularly obedient, and there was a twitch in his back that warned her to be alert.

Sabata was a god and a Great One, but he was also a stallion, and spring was in his blood. He could smell the mares on the other side of the school, in the School of War. If he had had his way, he would have gone courting and won himself a band of them.

“You have a high opinion of yourself,” she said as he tried for the dozenth time to veer off toward the gate. He had not succeeded yet, but he was determined to keep trying. Discipline was the last thing he wanted to think about just then.

“Discipline is the first virtue of a rider,” Valeria said.

Sabata shook his head and snorted. There was a distinct hump in his back under the saddle. He was not a rider, and very glad he was of it, too.

Just as he left the ground, a stranger’s startled face blurred past her. It was only an instant’s distraction, but that was enough for Sabata. He exploded in more directions than she could count.

It was a long way to the ground. She had ample time to tuck and roll. She also had time to contemplate the virtue of discipline, and to be struck by the humor of it all.

She tumbled to a halt with a mouthful of sand and a collection of entirely new bruises, and no breath for the laughter that was trying to bubble out of her.

Two faces stared down at her. One was long and silver-white and gratifyingly embarrassed. The other was oval and brown and incontestably human.

“Rider?” the boy said. “Are you dying?”

She did not want to sit up. She wanted to lie in the sand and count her bones and try not to think about how it would feel when she moved. Still, there was Sabata, belatedly appalled at what he had done to his rider, and this child whom she had never seen before, whose eyes looked ready to pop out of his head.

She sat up very carefully. Her head stayed on her shoulders. All the parts of her moved more or less as they should. Nothing was broken, even the arm that still ached when she moved it just so. There was a ringing in her ears, but that was the Mountain.

It was also the boy who had startled her into falling off her stallion. He was so full of the Call that she was amazed he could walk and talk.

He was otherwise perfectly ordinary, with a smooth, olive-skinned face and big dark eyes and curly black hair. His clothes were plain and had seen a great deal of use. He looked as if he had been traveling for days without enough to eat.

“You’re not dying,” he said. He sounded relieved. He held out a grubby hand.

She let him pull her to her feet. He was stronger than he looked. “How did you get here?” she asked him.

“I walked through the gate,” he said.

“Nobody met you?”

He shook his head. “There were people, but nobody said anything. I kept walking until I came here.” His eyes turned to Sabata and melted—there was no other word for it. “Is he—is that—”

“That is Sabata,” Valeria said.

The boy’s hand stretched out as if he could not help himself. Valeria made no effort to stop him. Sabata did not move away, either, which was interesting. No one could lay a hand on Sabata unless he wanted it—and mostly he did not.

He suffered this child to stroke his neck and find the particular spot in the middle and rub it until his lip stretched and began to quiver. The boy was enthralled. “Beautiful,” he said dreamily. “So beautiful.”

“He certainly thinks so,” Valeria said. “We have exercises to finish. If you can wait, I’ll show you where to go.”

“Oh, yes,” the boy said. “I can wait. You’ll let me watch?”

“I won’t be falling off again,” Valeria said firmly. She lowered a glare at Sabata. “Here, sir.”

Sabata had had his fill of defiance for the day. He came to her hand and stood perfectly still for her to mount. That was not as graceful as usual—some of her bruises were in difficult places—but she managed.

All the while she rode, the boy watched, rapt. He was not only full of the Call. He was full of magic. He had control over it—not like one of last year’s Called, whom she still remembered with pain. This one would not give way to temper and lash out with killing force.

It was not the best ride she had ever had. She was stiff and sore, and Sabata was trying a little too hard. She finished on as good a note as she could, then with the boy trailing blissfully behind, took Sabata to his stable.

Some of the stallions were in their stalls, sleeping or chewing drowsily on bits of hay. Most were out with their riders in various of the halls and riding courts, or enjoying an hour’s liberty in one of the paddocks. By that time Valeria had learned that the boy’s name was Lucius, that he came from a town not far from the Mountain, and that he was a journeyman of the order of Oneiromancers.

He was helping Valeria take off Sabata’s saddle and bridle and brush out the stallion’s moon-colored coat. She paused as he told her what he was, staring at him over the broad pale back. “You’re a dream-mage? What are you doing here?”

“I dreamed that I was Called,” he said.

“Obviously,” said Valeria. “Mages have been Called from other orders before. But just Beastmasters, I thought, and the occasional Augur. I didn’t think—”

“I didn’t, either,” he said, “but here I am. Like you. Is a woman supposed to be a rider?”

“No,” said Valeria.

“Well,” said Lucius, “there you are.”

He seemed to think that her existence explained his. She did not see what that had to do with it, but she was disinclined just then to argue. She went on with what she had been doing, frowning slightly.

When Sabata was clean and brushed and content with a manger full of hay, and the saddle and bridle were cleaned and put away, Valeria took the visibly reluctant Lucius to the rider-candidates’ dormitory.

He was not the only one there after all. Two more had come in while he was basking in Sabata’s presence. They both wore the uniform of the legions, and they were older than Valeria would have thought a rider-candidate could be. One must have been well up in his twenties.

First Rider Andres, who had taken charge of the rider-candidates in her year, as well, had them in hand. He raised a brow at Lucius’s escort, but he did not say anything in front of the candidates except, “Three on the first day. That’s a good number.”

“Let’s hope it’s an omen,” Valeria said. The legionaries were staring at her as if they not only knew who and what she was, they were in awe of her.

That was not comfortable. She could call it a strategic retreat, or she could regard it as a rout. Either way, she escaped those wide eyes and worshipful faces.

Valeria came to bed late. There had been lessons in history and politics and various facets of the horse magic, and a session in the library that had run through dinner. Then she had gone with a handful of riders to raid the kitchens. By the time she left the last of them at his door, the hour was well on its way toward midnight.

The lamp by the bed was lit, its flame trimmed low. The fire was banked in the hearth, but it shed just enough heat to take the edge off the chill.

Kerrec was in bed and apparently asleep. All she could see of him was a heap of blankets.

She dropped her clothes, shuddering as cold air touched her skin, and slid in beside him. His back was turned to her, his face to the wall. She pressed herself softly against him and kissed his nape where the black curls were clipped short.

He lay perfectly still. Her hand ran down his side, tracing the familiar gaps and ridges of scars. They were all healed now, the deep pain gone, and some had begun to fade.

She let her touch bring a little more healing, a little more warmth. He should have roused then and turned, but he never moved.

She sighed inaudibly. She had been full of things to tell him, but he was obviously determined not to wake.

Well, she thought, he worked hard these days—harder than she. He was the only First Rider left from the time before—that was what everyone called it now. Before the Great Dance that had ended with six riders dead and the empire’s fate so nearly turned toward destruction. It was only six months ago, just half a year, but it divided the world.

He had been the youngest. Now he was the chief of the First Riders. The others were all new to their office, and none too ready for it, either. They were doing well enough now, all things considered, but it had been a bitter winter. The school still mourned its dead, and would mourn them for a long while yet.

Much more than lives had been lost in that Dance. Strong magic and great art were gone, the province of masters who had devoted decades to the mastery of the stallion magic. Nothing but time could bring that back—if it could be brought back. Some of what was gone might never be recovered.

Valeria laid her cheek on Kerrec’s shoulder and closed her eyes. She wanted to hold him tight, but she knew better than to try that. He had paid a high price to be here, alive and safe. The scars on his body were the least of it. His heart and soul had been taken apart and were still healing slowly. His magic…

It was mending. He was strong. He worked harder than anyone and tested himself more sternly. He was thriving.

She had to believe that. They had done no more than sleep in each other’s arms—or he in hers, if she was going to be exact—for weeks. Months? She did not remember, probably because she did not want to.

She was still here. That was enough. He was first among the First. He could order her out and she would have to go, because she had sworn herself to a rider’s discipline, and obedience was part of it.

He had done no such thing. He wanted her here, even if he did not want her the way he had in the autumn and through the early winter, night after night. The memory of those nights could still warm her.

They would come back. He was tired, that was all.

So was she. She should sleep. She had another long day tomorrow, and long days after that.

A rider’s discipline could accomplish this as well as anything else. She closed her eyes and willed herself to sleep. After a while, she succeeded.

Seven

Kerrec lay motionless. Valeria was at last and mercifully asleep.

Her dream brushed the edges of his awareness. It was a dim thing, tinged with unease, but the white power of the stallions surrounded it. They guarded her even in dreams.

She could never know how much he wanted to turn and take her in his arms and kiss her until she was dizzy. But if he did that, he would have to open himself to her, and she would know.

She could not know. No one could. They had to believe that he was whole. He had to be. He could not afford to be broken.

During the day he could hold himself together. Much of what he did required no magic, or could be done with what little he had. He could still ride—that much had not left him. He could teach others to ride, and through the movements see the patterns that shaped the world.

The nights were another matter. He had to sleep, but in sleep were dreams.

At first he had been able to keep them at bay, even change them. His stallion had helped him. As winter went on, the dreams had grown worse.

Now he did not even need to sleep to hear that voice whispering and whispering, or to see the featureless mask of a Brother of Pain. Sometimes there was a stranger’s face behind it. More often there was one he knew all too well.

He never dreamed, awake or asleep, of the body’s pain. That had been terrible enough when it happened, and the scars would be with him until he died, but it was not his body that the Brother of Pain had set out to break. He had been commanded to break Kerrec’s mind and destroy his soul.

He had had to leave the task unfinished, but by then it was too far along to stop. What had been carried out of that place which Kerrec still could barely remember, had been the shattered remnants of a man.

The shards had begun to mend themselves. Kerrec’s magic had grown again, slowly but surely. He had dared to hope that he would get his old self back.

Then the healing had stopped and the edges of his spirit had begun to unravel. It was as if the Brother of Pain had reached out from the other side of the dream world and set his hooks in Kerrec’s soul again, even deeper than before.

Every night now, the whisper was louder, echoing inside his skull. What use is a dead prince in a living world? What purpose is there in this magic that you pride yourself in? What is order, discipline, art and mastery, but empty show? The world is no better for it. Too often it is worse. Give it up. Let it go. Set yourself free.

Every night he struggled to remember what he had been before. He had been a master of his art, endowed with magic of great power and beauty. His discipline had been impeccable. He had mastered the world’s patterns and could bend them to his will.

That was gone. The whole glorious edifice had fallen into ruin. All that was left was a confusion of shards, grinding on one another like shattered bone.

Very carefully he eased out of Valeria’s arms. It hurt to leave her—but it hurt more to stay. She was everything that he had been and more.

It was not envy that he felt. It was grief. He should have been her match, not a broken thing that she could only pity.

He was unprepared for the wave of sheer, raw rage that surged through him. The rage had a source—a name.

Gothard.

He could name the red blackness that laired in the pit of his stomach, too. It was hate. Gothard had done this to him. Gothard had given the Brother of Pain his orders. Gothard’s malice and spite had broken Kerrec’s mind and shattered his magic.

Gothard his brother, Gothard the half-blood, had nothing but loathing for his brother and sister who were legitimate as he was not, and for his father who had sired him on a hostage. He wanted them all dead—and he had come damnably close to succeeding.

He had escaped defeat and fled from the reckoning. No one, even mages, had been able to find him. But Kerrec knew where he was. He was in Kerrec’s mind, taking it apart fragment by fragment.

Somewhere, in the flesh, he was waiting. Kerrec had no doubt that he was preparing a new assault on everything and every person who had ever dealt him a slight, real or imagined. Gothard would not give up until they were all destroyed.

With shaking hands, Kerrec pulled on breeches and coat and boots. It was halfway between midnight and dawn. The school was asleep. Even the cooks had not yet awakened to begin the day’s baking.

In the stillness of the deep night, the Call grated on his raw edges. He had enough power, just, to shut it out.

He went to the one place where he could find something resembling peace. The stallions slept in their stable, each of them shining faintly, so that the stone-vaulted hall with its rows of stalls glowed as if with moonlight.

Petra’s stall was midway down the eastern aisle, between the young Great One Sabata and the Master’s gentle, ram-nosed Icarra. Kerrec’s friend and teacher cocked an ear as he slipped into the stall, but did not otherwise interrupt his dream.

Kerrec lay on the straw in the shelter of those heavy-boned white legs. Petra lowered his head. His breath ruffled Kerrec’s hair. He sighed and sank deeper into sleep.

Even here, Kerrec could not sleep, but it did not matter. He was safe. He drew into a knot and closed his eyes, letting pain and self-pity drain away. All that was left behind was quiet, and blessed emptiness.

Valeria knew that she was dreaming. Even so, it was strikingly real.

She was sitting at dinner in her mother’s house. They were all there, all her family, her three sisters and her brothers Niall and Garin, and even Rodry and Lucius who had gone off to join the legions. The younger ones looked exactly as they had the last time she saw them, almost a year ago to the day.

She was wearing rider’s clothes. Her sister Caia curled her lip at the grey wool tunic and close-cut leather breeches. Caia was dressed for a wedding in a dress so stiff with embroidery that it could have stood up on its own. There were flowers in her hair, autumn flowers, purple and gold and white.

She glowered at Valeria. “How could you run away like that? Don’t you realize how it looked? You ruined my wedding!”

“There now,” their mother said in her most quelling tone. “That will be enough of that. You had a perfectly acceptable wedding.”

Caia’s sense of injury was too great even to yield to Morag’s displeasure. “It was a solid month late, and half the cousins couldn’t come because they had to get in the harvest. And all anyone could talk about was her.” Her finger stabbed toward Valeria. “It should have been my day. Why did she have to go and spoil it?”

“I didn’t mean—” Valeria began.

“You never do,” said Caia, “but you always do.”

That made sense in Caia’s view of the world. Valeria found that her eyes were stinging with tears.

Rodry cuffed Valeria lightly, but still hard enough to make her ears ring. “Don’t mind her,” he said. “She’s just jealous because her lover is a live smith instead of a dead imperial heir. That’s how girls are, you know. Princes, even dead, are better than anything else.”

“Kerrec is not dead,” Valeria said.

“Prince Ambrosius lies in his tomb,” said Rodry. “It’s empty, of course. But who notices that?”

“That was his father,” Valeria tried to explain, “being furious that his heir was Called to the Mountain instead of the throne. He declared him dead and stopped acknowledging his existence until there was no other choice. Isn’t that what Mother has done to me? I’ll be amazed if she’s done anything else.”

“Mother knows you’re alive,” Rodry said. “She’s not happy about it, but you can hardly expect her to be. She had a life all planned for you, too.”

“So did the gods,” said Valeria. “Even Mother isn’t strong enough to stand in their way.”

“Don’t tell her that,” her brother said, not quite laughing. He bent toward her and kissed her on the forehead. “I’ll see you soon.”

She frowned. “What—”

The dream was whirling away. The end of it went briefly strange. It was dark, a swirl of nothingness. She dared not look into it. If she did, she would drown—all of her, heart and soul and living consciousness. Every part of her would be Unmade.

The Unmaking blurred into the bell that summoned the riders to their morning duties. Valeria sat up fuzzily. The dream faded into a faint, dull miasma overlaid with her family’s faces.

Kerrec was gone. He had got up before her, as all too usual lately.

She would be late if she dallied much longer. She stumbled out of bed, wincing at the bruises that had set hard in the night, and washed in the basin. The cold water roused her somewhat, though her mind was still full of fog. She pulled on the first clean clothes that came to hand and set off for the stables.

Half a dozen more of the Called came in that morning, and another handful by evening. There had never been that many so soon after the Mountain began its singing. Some of the younger riders had a wager that the candidates’ dormitory would be full by testing day.