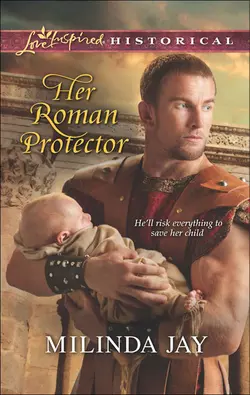

Her Roman Protector

Milinda Jay

A MOTHER’S MISSIONWhen her baby is stolen out of her arms, noblewoman Annia will do anything to find her—even brave the treacherous back alleys of Rome to search for her. Desperate to be reunited with her daughter, Annia finds herself up against a fierce Roman soldier who insists her baby is safe. Dare she trust him?Rugged war hero Marcus Sergius rescues abandoned babies for his mother’s villa orphanage. When he witnesses Annia’s courageous fight for her child, he remembers that some things are worth fighting for. Helping Annia means giving up his future . . . unless love is truly possible for a battle-hardened Roman legionary.

A Mother’s Mission

When her baby is stolen out of her arms, noblewoman Annia will do anything to find her—even brave the treacherous back alleys of Rome to search for her. Desperate to be reunited with her daughter, Annia finds herself up against a fierce Roman soldier who insists her baby is safe. Dare she trust him?

Rugged war hero Marcus Sergius rescues abandoned babies for his mother’s villa orphanage. When he witnesses Annia’s courageous fight for her child, he remembers that some things are worth fighting for. Helping Annia means giving up his future…unless love is truly possible for a battle-hardened Roman legionary.

She would have to be very clever with Marcus Sergius Peregrinus.

“So tell me,” Annia said, sheathing her dagger, “where is this place you have my baby?”

He looked into her eyes, gauging them for sincerity, she suspected. “If you will come with me, I will show you. I don’t have much time. I have to get back to my men soon.”

“Aah,” she said. “Well, don’t let me keep you.”

He cocked his head, a question. “You are coming with me?” he said.

“Certainly,” she said, trying to keep the sarcasm out of her voice. “How else could I get to my baby? Only you know where she is.”

They walked civilly, side by side down the dark street. The only light came from the uncertain moon.

She didn’t trust this man. She knew better than he where her baby was. He had taken her daughter to the place of exposure, where the slave traders circled like hawks. Annia meant to get there.

She had to get away from him first.

When he turned, she took her chance. She ran.

MILINDA JAY

When she’s not writing—or reading—books, Milinda Jay designs fun sewing projects for www.janome.com (http://www.janome.com), and Sew News and Creative Machine Embroidery magazines. She also teaches college students how to write. She lives with her husband, five wonderful children and two dogs near the beautiful beaches of Panama City, Florida.

Her Roman Protector

Milinda Jay

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast.

—Psalms 139:8–10

To my husband, Hal, my real-life hero, who made this book possible.

Acknowledgments

It takes a community to write a book, and I am so grateful for my writing community, without whom this book would have never made it to print. Thank you to Jill Berquist, Tanya Brooks, Mark Boss and Janice Lucas for reading this book in draft form and giving me wise suggestions for editing.

Thank you, Stephanie Newton and Kathy Holzapfel, for teaching me how to write romance. I’m still learning. Thank you, Michael Morris, for sharing your writing wisdom.

Thank you to Dr. Sarah Clemmons and her amazing assistant, Jan Cummings, for allowing me to teach humanities at Chipola College, where my students helped me learn all about the Roman Empire.

Thank you to the Cheshires, a group of fabulous writers who gave me courage during the harrowing process of getting a first book published: Carole Lapensohn, Ruth Corley, Marty Sirmons and Mark Boss.

And thank you to my brilliant editor, Emily Rodmell, who believes in me enough to help make me a better writer.

Contents

Chapter One (#u2e3290a8-47a7-57ce-849f-24a576e9be51)

Chapter Two (#u247045a2-a70b-5cea-9c7c-20ade8ebb0e9)

Chapter Three (#u2aae234b-95ec-5769-87d6-0242a16bac17)

Chapter Four (#u26f7681b-9f4c-5c63-ae71-0574191a79e9)

Chapter Five (#u5f197db6-135b-57cd-b6bf-f49236504bf2)

Chapter Six (#ub174d1ea-e469-5b03-9432-66b21fb5860a)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt (#litres_trial_promo)

Rome, 49 AD

Chapter One

Moonlight shone through the tiny window, casting a gentle glow on the face of Annia’s beautiful newborn baby girl. The tiny gold bear charm on the baby’s necklace sparkled for just a moment before the moon took refuge behind the clouds.

“If I could only tell you how much you are loved, and have you understand,” Annia murmured.

She laid the baby down on the prickly straw-filled mattress and pulled the urine-soaked cloth from beneath the swaddling, deftly replacing it with a clean one. She picked up the newborn and kissed her tiny head, then cradled her in her arms.

“My sweet baby girl,” she murmured into the soft newborn hair, “I will love you as much as a mother and a father.”

Annia herself was not feeling particularly loved. Nine days ago, she had given birth alone except for the midwife and Annia’s slave, Virginia.

Annia’s husband, Galerius Janius, had divorced her on false charges of adultery. He had separated her from her two small sons and exiled her to this small villa at the outermost edge of Rome.

But he didn’t take her baby. Not even he could be that cruel.

Or perhaps he had forgotten the baby in his rush to marry the wealthy cousin of the emperor.

Annia placed the baby in her wooden cradle, and the scent of rosemary filled the air. The mattress, stuffed with carefully chosen herbs, kept the infant safe from the chills brought by the heavy Roman mists.

The baby slept, and Annia considered calling Virginia for a taper. Perhaps if she read for a while, her heart would stop hurting so badly. She looked at the scrolls stowed neatly in the racks she had built on her wall. Maybe a Psalm would remind her she was not alone in her pain.

“Lord, keep my children safe,” she whispered.

The ache of losing her boys hurt far worse than having her husband discard her.

Annia could only hope that Janius’s new wife would find the boys tiresome and send them away. And then Annia could have them back.

Janius had made it clear for many years that he did not love her. Shortly before he accused her of adultery, he revealed that he had never loved her.

Perhaps her boys would remind Janius of Annia. Or he would want them out of his sight. Possibly she would get them back even sooner than she expected.

She lay down and covered herself with a light wool blanket. She might be able to sleep on this happy thought.

Before she could drift into blissful forgetfulness, the rhythmic crunch of hobnailed sandals echoed on the basalt-paved streets below.

It was the footsteps of soldiers. She sat up in her bed. Their torches lit the street below, reflections casting ghastly shadows on the frescoes covering her tiny bedroom walls.

The banging of bronze against wood told her they had come to her villa.

Why? What could they possibly want with her?

She heard Virginia shuffle down the stairs in her soft house sandals.

“Who’s there?” Virginia asked.

“Marcus Sergius Peregrinus, commander of the Vigiles,” a gravelly voice answered. “By order of the emperor Claudius, we are here to retrieve the stolen property of Galerius Janius.”

“What stolen property?” Virginia asked pertly. “The only thing here is the wife he divorced, and she is no longer his property.”

“It is not the woman we are here for,” the gravelly voice continued. “It is the baby.”

“The baby?” Virginia asked. “What does he want with her?”

“She is to be exposed before sunrise,” the man said. “To die or be taken by the slave traders as the gods decree.”

Exposed? The barbaric custom of leaving an infant out at the specifically designated place of exposure to die or be picked up by slave traders was something Annia had never expected to have happen to one of her own children. Dear heavenly Father, she prayed, please, not that. But the Roman father—the paterfamilia—had the power of life or death over any of his children. And he was not required to be merciful like her heavenly father.

Annia had always considered the ceremony shortly after birth whereby the midwife placed the newborn at the father’s feet to be picked up and named or left on the floor, indicating it was to be exposed, merely a formality.

Surely, no father in his right mind would order his own healthy child exposed.

Annia tried to remember what her midwife had said when she brought the baby back to Annia. But the memory was a blur.

“Leave us alone,” Virginia said to the gravelly voiced commander. “What possible harm can a baby do such a gallant as Galerius Janius? Does he fear a child?”

“That is not for me to determine,” Marcus Sergius replied. “Now open the door, or we will be forced to open it for you.”

The door opened. “Wait here,” Virginia said. “I will get the child.”

“Annia,” Virginia called, running up the stairs, “Annia. The Vigiles are here.”

“Is there a fire?” Annia asked, her humor masking the raw panic in her heart.

“No,” Virginia said. “They’ve come to take Maelia. Galerius Janius wants her exposed. Do something, Annia.”

Annia loosely belted her stola, the tunic-like dress—allowing it to fall easily over the coarse slave’s tunic she wore beneath. She donned a blue silk palla. Rather than pinning the long oblong covering with the traditional bronze pin, she threw it casually over her shoulder and wrapped the baby in a matching blue silk blanket. She walked down the stairs, her footsteps certain, though her heart quaked.

“How can you be so calm?” Virginia asked. “They want to take her away.”

“Be quiet,” Annia hissed. “I will make certain they do not.”

She walked beside the small pool that formed the center of her modest villa and into the atrium where her guests waited.

“You wish to see me?” Annia said to the commander, demanding an accounting of his presence with her question. She handed Maelia to Virginia.

Marcus Sergius transfixed her with dark eyes under a leather helmet. His build was strong and hard, his chiseled features matched his gravelly voice. He was younger than he sounded, perhaps midthirties. And even in the uneven light cast by the lantern he held, she could see he was a handsome man.

She felt certain she had seen him before. Had she walked by him on the street as he led his men? That wasn’t it. A dinner? That was it. He had been invited to one of Galerius Janius’s dinners. It seemed a lifetime ago.

“May I see the emperor’s order?” Annia asked.

He took a scroll from beneath his leather breastplate and handed it to her.

Annia examined the purple wax seal. She read the scroll. It was genuine. She looked up at the man. Marcus Sergius avoided her eyes.

“If you must go through with this barbaric practice on my child,” Annia said, her voice steely, “then I will go with you. I will carry her to that place of death and lay her on a pile of rubbish myself.” She handed Virginia the scroll and took Maelia from her arms.

The fierce commander raised his chin. “That is unheard of,” he said.

“Just because it is unheard of does not make it impossible,” Annia returned. She stood tall, but her height was nothing compared to his.

“Hand me the baby, domina,” Marcus Sergius said, holding out his arms.

“I said I will take my baby to that place of horror.” Annia pushed her way through the eight soldiers and out the large wooden door. She stepped out onto the sidewalk in front of her villa and began walking down the street, her silk stola swishing behind her.

The Vigiles stared, their mouths agape.

“What are you waiting for?” Marcus Sergius demanded. “Follow her.”

She was soon forced off the street by a merchant’s wagon, the metallic clamor of iron wagon wheels turning on stone pavement filling the air.

But she feinted to the opposite side of the street from the surprised soldiers. She looked behind her to make certain she had lost them.

She had.

The night police—Vigiles—were heading in the opposite direction.

The moon was her friend and ducked behind a cloud just as she melted into a narrow alleyway.

Sheltered by the darkness, she shed her silk palla and stola and dropped the baby’s blanket. Beneath all of it she wore the rough homespun of a slave, and her baby was wrapped in slave’s swaddling. Annia wore soft leather calcei, as well. The moccasins were comfortable and perfect for running.

She had no time to take off the baby’s golden crepundia necklace, its tiny toys jingling on their string, nor her own gold necklace with its matching bear charm. She prayed no one would notice the expensive jewelry marking her as anything but a slave. She wrapped the baby tightly in the rough wool blanket she’d hidden beneath the silk and fashioned a sling from her long wool belt.

She secured the sling around her and tucked the baby beneath her breasts.

And then she ran.

The streets of Rome at night were dark and noisy, filled with merchants carrying their wares in the carts that were forbidden on the Roman streets by day. As long as she stayed close to the swiftly moving traffic, she was safe.

She looked like a slave, as her former husband had often reminded her. She was small and dark like her mother’s people in Britain. Her eyes were large and brown, and her hair was dark and so curly that she had to keep it cut short like a boy’s. Otherwise, it grew in a wild tangle around her face that even the patient Virginia was hard-pressed to comb out.

In the darkness she could not see to avoid the street trash and nearly slid on a pile of smelly kitchen offal, scattering a group of howling street cats dining on their supper.

Fueled by anger and fear, Annia ran. She was quick and she was strong. She listened for the telltale sign of hobnailed sandals following her, but heard none.

Had she escaped so easily?

She had never been so grateful for her athletic training in Britain as she was now. She had been the laughingstock of other Roman matrons when she was married to Janius because she insisted on training like a man. She ran. She exercised. She even sparred with anyone willing to take her on.

In Britain it had been necessary. Even after Claudius had come and secured the island for Rome, you never knew who or what might jump the stone fence of your outpost farm and try to seize your cattle and rob your stores.

In Rome, the exercise allowed her to live within the stifling social order with a measure of contentment.

She paused, hiding behind an erect wooden board inserted into the pavement. The board and weighted bronze bolt safeguarded the jewelry shop behind it. Maelia slept, tied snugly against her.

It was completely dark. She heard movement at the end of the street. When the moon peeped from behind the cloud, she could see a human figure stop, walk forward a little, then stagger against a wall.

She breathed a sigh of relief. It was only a drunk.

She crept from behind the sheltering board, looked right and left and dashed down the now dangerously moonlit street. She prayed the moon would hide itself again, but it did not.

Annia felt she was running in glaring daylight, so bright did the moon shine. She could see the cracks in the basalt squares of the road. She could almost make out the lettering on the walls above the closed shops.

She grasped the baby nestled safely in the makeshift sling. Fear propelled her forward once again. But when she turned down the next alley, she ran directly into a hard-chested Roman soldier who grasped her tight.

* * *

Marcus Sergius hadn’t expected to find her so quickly, but he thanked the one God that he did.

Only Marcus could keep this baby safe, but he hadn’t the time to explain that to her.

The woman struggled like a bear. He held her tightly against him, careful not to crush the infant. He felt Annia’s warmth through his thin leather chest-plate. The baby nestled beneath Annia’s protective arm, her other arm pinned safely beneath his.

She kicked his shins, her legs surprisingly strong, though her moccasins were too soft to cause any real damage. She tried to bite through his leather breastplate.

She was nearly successful.

“Give me the baby,” he said to her. “I won’t hurt her.” He tried to keep his voice level and calm, but he found himself jumping with each vicious little kick.

“You won’t hurt her?” she said, jeering. “No, you probably won’t. She wouldn’t be worth much on the slave market if you damaged her.”

This was not going as he intended.

He had managed to successfully separate himself from the eight new recruits, but at any moment one could appear. They were young and stupid. None had seen battle. Each thought soldiering glamorous.

Young fools. He hoped they would never see the horrors he had seen in Britain against Caratacus and his guerrilla warriors.

Could she understand if he tried to explain that he had a safe place for her baby? The fury in her voice and the steely anger in her eyes told him what he needed to know.

Perhaps he could take her with him. No, that would be too dangerous. She was beautiful.

And that very beauty would be noticed. Someone would see him accompanied by such a lovely slave carrying a baby.

No, he had to take the baby and leave her here. He would come back for her later.

It should have been easy. He thought back over his plan. It usually worked. It had worked many times before. He went into the house in the dark of night. He took the baby. He sent his young recruits to rest at the local eating place under the auspices of needing to be alone while he exposed the baby at the vegetable market.

But what really happened, that is, what really happened on every night except for tonight, was that instead of taking the baby to the vegetable market to be picked up by slave traders, he took the baby to his mother.

His mother took the teachings of the Master very seriously when He said to care for widows and orphans. She left the widows up to someone else, but she set it as her life’s mission to care for orphans, specifically the babies that would most certainly become slaves or die if left on the rubbish pile.

And her strong, handsome son, home from the war and conveniently placed as the commander in charge of the Vigiles, was the perfect accomplice.

But Annia was different. He had never come in contact with a mother who fought so immediately for her baby. Usually, the husband ordered the wife drugged with poppy juice so that she was unaware of exactly what was taking place.

Of course, this was the first baby he had taken from a divorced woman. It was also the first he had taken so long after birth. Usually, the marriage was intact, and the husband simply did not want to divide his wealth with another child. The child was taken at birth, and the wife complied because she feared losing her marriage.

A stomp on his toe brought him back to the very real woman in front of him. He was going to have to render her unconscious. He knew this, but he did not want to follow through. It was the only way he was going to be able to get her baby to a safe place without attracting any further notice.

He would have to act quickly. He placed his fingers on her jugular and pressed. He held her other arm down, and kept the arm on the baby.

He caught her when she fell, untied the baby and left the woman there. He knew she would awaken very quickly, and he had to be gone when she did.

The baby slept, but Marcus took no chances. He sprinted through the dark back streets of Rome as if he were going to the market. But, instead of turning at the road leading to the forum, he doubled back around the baths and ran as quickly as he could to his mother’s house.

He had no time to explain why he was dumping the baby unceremoniously in the ostiarius’s arms. The elderly man who watched the door was accustomed to such wriggling bundles.

Marcus couldn’t let the woman stay on these streets alone at night. She could be captured or worse. Anger filled him at the thought of the things that could happen to her.

He had to reunite her with her baby.

He turned as quickly as he could and sprinted back to where he had left her.

She was gone.

Dear God, he prayed, please let her be safe.

He passed street after street with no sign of her. He tripped over a family sleeping outside in one alley and scattered a group of young street urchins in another.

Where could she have gone?

He retraced his steps, this time more slowly. Had someone taken her? Had he gone past her? Did she know a different way to the place where babies were exposed? Was she thinking of another place of exposure?

And then he realized that she had probably already reached the forum and was searching in the offal for her child.

How could he be so stupid? He had seen how quickly she ran. Why hadn’t he gone there first?

Now it was he who was sprinting as if his life depended on it. What made this woman so important? He tried to convince himself he would have done the same for anyone, but he knew differently. Something about her haunted eyes, her quick-thinking ruse. Here was a woman who gave it all, held nothing back.

When he heard a group of men laughing and heard her scream, he moved swiftly in.

The men were circled, one holding her by the hair, another holding a lantern up to her face.

“What have we here?” the man holding her asked. He was large, probably a blacksmith or shipbuilder, someone accustomed to using his body for hard work. His muscles glinted in the firelight, and the group of men surrounding him waited.

But they waited like hyenas who watch prey caught by a lion. They would take their turn only after he had his fill.

Marcus knew he would have to be very careful.

“So there you are, you little minx,” Marcus said, striding into the center of the circle, his voice as deep and loud as he could make it.

It had the intended effect, startling the men with its volume.

Even the blacksmith, or whatever he was, jumped a little, but he maintained his grasp on her hair.

“Running from me once again. You thought you could get away this time, did you?” Marcus strode into the group of men breaking through them as if he were the emperor himself.

“Thank you, sir,” he said to the blacksmith.

Marcus grabbed Annia roughly and jerked her away. Fortunately, in his surprise, the blacksmith let go of her.

Marcus pulled her away, berating her all the way, “You curly-haired vixen, what did you think? Were you thinking I wouldn’t catch you? You wait until I get you home....”

Annia let out a small yelp when he pretended to slap her face, and the men circled around them and laughed.

“Thank you, sirs,” Marcus said, putting a hand over Annia’s mouth. “This little one has run away one too many times. I may have to sell her at market.”

“I’ll buy her,” the blacksmith said. “How much will you take?”

“Well,” Marcus said, “she actually belongs to my father. But give me your name and where you conduct your business, and you will be the first one to know when we put her up for sale.” Marcus shot the man a charming smile. “I would shake your hand, but as you can see, mine are quite full.”

The men parted to let him through.

“Suetonius Rufus,” the blacksmith called. “My shop is three streets over near the baths. I’m a blacksmith,” he continued.

“Thank you, sir,” Marcus said. “I will remember you by your red hair.”

The man touched his hair, and Marcus pulled Annia safely away around the corner, out of the man’s line of vision.

When they reached the safety of the baths, Marcus took his hand off her mouth.

“You did me no favors,” she spat. “I would have escaped on my own.” And she unsheathed a tiny dagger to prove it.

“Really?” he said, pulling her into the dark recess of the inner fountain. “Well, domina, next time, I will let you defend yourself.”

She was shaking and held the dagger to his stomach. “Where is she?” she hissed. “Where did you take my baby?”

“Put the dagger down, and I will tell you,” he said.

Chapter Two

He must take her for a fool. How many other women had this handsome man lured into believing he was saving their babies, when in truth, he was selling them into slavery?

She had to be very careful with this one. He was strong, he was smart and he seemed determined.

Well, she had fought fierce warriors in Britain, hadn’t she? Surprising them with her strength?

He would not be surprised. He had already gauged her strength. She would have to be very clever with Marcus Sergius Peregrinus. Very clever indeed.

“So tell me,” she said, sheathing her dagger, “where is this place you have my baby?”

He looked into her eyes, gauging them for sincerity, she suspected. “If you will come with me, I will show you. I don’t have much time. I have to get back to my men soon.”

“Ah,” she said. “Well, don’t let me keep you.”

He cocked his head, a question. “You are coming with me, yes?” he said.

“Certainly,” she said, trying to keep the sarcasm out of her voice. “How else could I get to my baby? Only you know where she is.”

They walked civilly, side by side, down the dark street. It was a few hours before dawn, and the streets were now quiet. Even the merchants’ carts had stopped, having already delivered their wares.

The only light came from the uncertain moon and the pitch-smeared torches illuminating sacred images at a few street corners and crossroads.

She didn’t trust this man. She knew better than he where her baby was. He had taken her to the place of exposure where the slave traders circled like hawks. Annia meant to get there.

She had to get away from him first.

The silence was broken by the cascading water of a neighborhood fountain. When they reached the fountain, the statue of a small boy—his arms reaching out in supplication, a stream of water flowing from his mouth—was illuminated by a single flame placed strategically at the water’s edge.

During the day, this same fountain was busy with women, children and slaves taking turns filling their wash buckets and water jars to carry back to their homes.

But tonight, it was eerily silent, the only sound the soft rush and gurgling of the water.

“Are you thirsty?” Marcus Sergius asked.

Annia was thirsty, incredibly thirsty. She ignored his offer of help and reached up to the trickling water, cupping her hands and drinking deeply.

Marcus waited for her to drink her fill and then reached up to drink.

When he did, she took her chance. She ran.

Apparently, he had expected her to run and he caught her before she even reached the pavement at the edge of the fountain.

They both went down on the hard stone, he on his back and she atop.

He grasped her arms, and she kneed him in the stomach. She pulled away and unsheathed her knife.

Both on their feet, they circled each other. His breathing was heavy, as was hers.

She jabbed, but he pulled back and then reached for her knife.

But she was quicker.

His eyes widened. She was used to it. He hadn’t expected her to be this good with a weapon. What proper Roman matron could wield a knife with such dexterity?

The look on his face now was one of respect. What had he recognized? Before she could move again, he had countered. He seemed to know exactly what she was going to do before she did it, and now he was holding her wrist, tightening his grip until she was forced to drop the knife.

“Trained in the wilds of Britain, as well?” he said, his voice ragged.

Now it was her turn to stare wide-eyed at him.

Fury strengthened her. She poised to run as soon as she had the chance.

“I would rather not do this,” he said, “but you leave me no choice.”

With the dexterity of a battle-trained legionary, he caught her wrists in a leather thong and pulled it securely. Her wrists bound, she was forced to walk humbly behind him.

“Where are you taking me?” she asked. “I know your type,” she said. “Ready to make a gold coin off anything possible.”

She could tell from the set of his shoulders that she had angered him. He said nothing.

“I have money,” she said. “I can buy my child from you. I can get you all you need.”

“I don’t want your money,” he said.

“I’ve yet to meet a soldier who didn’t want money, who wasn’t willing to buy his way to the top so that he could stop fighting and send other men in to do the bloody work.”

At this, he turned on her, yanked the leather cord down, savagely squeezing her wrists so tightly that tears smarted in her eyes. He pulled her close.

“You, domina, have no knowledge of what you speak. Close your mouth, and let me take you to your baby before I change my mind.”

The struggle in his face was palpable. She had struck a chord in this man. A deep one. The pain in his face spoke of unspeakable horrors. She was embarrassed and ashamed, but she was not certain why.

He was her enemy. He had her tied with a leather thong. Why did she feel such compassion for a man who had sold her baby and was now leading her to be sold?

She almost apologized but held her tongue.

She had no choice but to allow him to lead her to the place of enslavement. Perhaps, if she was blessed, she would at least be enslaved with her baby.

They stopped in front of a row of shops separated by a high wooden double door replete with bronze doorknobs.

Annia recognized the front door of a grand villa.

In the center of each door was a giant bear’s head holding a large ring in its mouth to be used as a knocker.

A bear’s head on a Roman door? Odd. Usually, the door carried a wolf, or even a lion, but rarely a bear.

Was it a sign? In Britain, bears meant strength and survival.

Characteristic of very wealthy Romans, this villa rented its street-front rooms to various shop owners, their signs barely visible in the darkness. There were four shops on either side of the door. Annia leaned back to see how many floors this villa held.

Three stories high. She guessed that the shop owners lived directly above the shop, and perhaps the floor above that was rented out to other tenants.

She had been the mistress of just such a villa.

Marcus lifted and dropped the knocker.

It sounded her doom.

Immediately, the door opened.

Annia felt her fate closing in on her. Why? Why had Janius been so determined to get rid of her baby girl? Did he fear having to provide a dowry for her? Did he fear he would have to divide all his new wealth with his youngest daughter?

And if he was so quick to get rid of this newborn, what would keep him from getting rid of their two young sons?

Surely Janius would not harm his own flesh and blood.

And yet he knew this newborn child to be his, and he had no qualms about exposing her.

Annia closed her eyes and whispered a prayer. Protect me, Lord. Protect my child.

“Mother,” Marcus said, his voice registering warm surprise. “Why are you up?”

“I had a bad feeling about this one,” a woman’s voice responded, “but you have brought her home safely?”

Home? Annia wondered. Home for whom? But she had no more time to ponder this question.

“Annia,” Marcus said, “I would like for you to meet my mother, Scribonia.”

Annia felt slightly off-kilter. Such a formal greeting for a would-be slave?

And Scribonia? Wasn’t that the name of her midwife? Surely not the same woman.

When Marcus moved out of her way, the lanterns lighting the atrium were directly behind the woman, blinding Annia and reducing the woman before her to dark, shadowy outlines. Annia could not make out the woman’s face or even the color of her clothing. She seemed tall, taller than Annia, and very thin.

Annia couldn’t tell if this woman was her midwife or not.

The woman seemed to be reaching for her.

Annia was frightened. What did the woman want of her? She wished that she could see better. She glanced at Marcus, but he had already moved forward, into the atrium behind his mother. He brushed past her.

“I must go now, Mother,” he said, and kissed her on the cheek. “Already, I fear the men may have left their duty and gone home.”

“Be careful, son,” his mother said, and then turned her attention to Annia.

Annia recognized the voice now. It was the midwife. She held something in her arms, and she was reaching to hand it to Annia.

When Annia held her hands out in response, the soft bundle placed there was none other than her baby girl.

Marcus gave a satisfied nod before closing the door behind him.

* * *

The night was black, the black that happened just before dawn. Marcus knew he’d better hurry if he was going to catch his men at the eating place before it closed.

Why had she been so stubborn? Why hadn’t she believed him? In spite of himself, Marcus was confused. He liked to be trusted. She hadn’t trusted him.

But then again, why should she have trusted him? He came into her house in the dead of night demanding to take her baby to be exposed.

How was she to know that he really didn’t mean to do it?

Could she learn to trust him?

Why did he care? What did it matter? His brain felt twisted in knots.

He couldn’t stop thinking of her.

He was back in Rome and looking for a wife, not the divorced mother of three children.

But there was something about the woman, something fierce, something beautiful, something that made him yearn to protect her.

It was late, and he was tired. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be thinking such thoughts.

When he arrived, his men were waiting as instructed. They were the last customers.

Trained to be as faithful as Roman soldiers in the field, the Vigiles sat around a long table, their mead cups before them. When one nodded, his neighbor clouted him awake.

The penalty for sleeping on guard in the field was death by stoning. The men were loyal to one another as well as to their sergeant.

“Sir,” one of his men said, “we feared for you.”

“We thought to come after you,” another broke in.

“But the order,” a third said, “was to stay here until you returned.”

They looked up at him hopeful, fearful.

The Roman army was built on fear, and these young men longed to be a part of the army.

Marcus felt for them. He remembered the same longing for adventure, the taste for discipline, the desire to be a part of something that would allow him to prove himself.

And get away from his family.

Wasn’t that the dream of all sixteen-year-old boys?

“You’ve done well, men,” Marcus said. They tried not to smile, but the boy in each of them couldn’t help being pleased. “Let’s go.”

They gathered their leather coin purses and strapped them to their belts.

Marcus paid Gamus the merchant, and his close friend. “Thank you, Gamus. I apologize for the long night.”

“Ah, Marcus. I am happy to help you. But before you go, step back here. There is something I’d like to show you.” The merchant waved him into a back room, and Marcus sent the men outside, where they lined up in close formation.

Marcus nodded and waited for him to speak. He knew Gamus had something important to say.

“What I’ve heard is not good for us, Marcus,” Gamus said, his voice hushed so that Marcus had to lean close to hear. “There is talk that the emperor wants the Jews out of Rome.”

“We are not Jews,” Marcus replied. “We are followers of the Christ.”

“Ah, but Claudius doesn’t know that. He sees us all as one big group of rabble-rousers. When the Jews go, I fear, so must we.”

Gamus straightened another amphora, pulling his cleaning cloth from beneath his belt.

“But where? Where is it safe? The empire stretches past knowing,” Marcus said. He had heard this rumor himself, but had thought it just that.

Gamus’s words frightened him. What about his mother? What about her villa full of rescued babies? How could they possibly be moved?

“It seems he merely wants us out of Rome,” Gamus replied.

“I see,” Marcus said, somewhat relieved. At least they would not be banned from the empire. “Do you have a place to go?”

“Yes, I have a country estate in Britain,” Gamus said, “a gift granted by Claudius for my long years of service in the army. My wife and I would like to retire there one day. Perhaps sooner rather than later. And you? Where would you go?”

The thought of leaving Rome was something he did not want to consider. He had just returned to the city of his birth after having been gone for twenty long years of service. He had a dream to stay here, to gain enough power to bring peace to his city.

“I don’t know,” Marcus said. “My father would love to move back to Britain, as well. He was happiest there, I believe. I would rather stay here. I believe I can be of the most use right here.”

“That may be so. Well, lad, perhaps the emperor will leave us alone. We are a peaceable people.”

Marcus agreed. It was the very peace of his faith that made him long to become a prefect.

“Well, my friend, thank you for entertaining my men.”

“Is the baby safe?” a female voice boomed, startling both men.

Gamus’s wife appeared in the stairwell next to the storage room. She was wrapped in a white linen robe, her hair mussed from sleep. Her warm smile, round, rosy cheeks and jolly disposition seemed at odds with her booming voice.

“Yes, Nona, the baby is safe.” Marcus smiled up at the kind woman.

“Good, good, then,” she said, clapping her hands together. “Now see your men home and come back here. I have dough rising, and by the time you get back the bread will be baked.” Her eyes sparkled and Marcus had to say yes, and pray that her voice didn’t wake everyone on the street.

“Thank you, Nona. You always take care of my stomach.”

“Well, child, you need your strength to traverse this wicked city. You must walk many miles each night.”

“Not so many,” Marcus said.

Nona smiled and retreated up the stairs. “See you in the morning light,” she said.

“How are the rescues going?” Gamus asked. “I worry about you, lad.”

“My mother’s villa is full to bursting,” Marcus said. “I’m not sure she can take any more babies. Tonight might have been my last rescue.”

“Good,” Gamus said. “I don’t like the danger for you. Too easy to be seen. Your mother has done a good thing all these years rescuing those poor, abandoned infants and trying to reunite them with those mothers who did not want them exposed. But she is only one woman, and Rome is a large city with many abandoned babies every day.”

“She only rescues the ones she delivers and knows the mother’s heart to be broken when the father orders exposure for lack of dowry money or some perceived weakness,” Marcus said.

“I know, lad, but it is becoming dangerous for you.”

“I do worry that my men are growing suspicious,” Marcus said.

“Not to worry. I give them as much mead as they want.”

Marcus laughed. “Thank you, my friend.”

“Good night, then,” Gamus said.

The night was spent and the gray dawn of morning rose around them as Marcus led the men down the street and back to their garrison.

The hobbed nails of their boots pinged against the stone as they marched into the early light.

The men were good, but what was he doing here leading a group of eight firefighters on a mission to keep the city safe, night after night?

He had a plan. He just prayed it worked. He had distinguished himself in Claudius’s wars in Britain. Serving under General Vespasian in the II Augusta Legion, he had fought to secure the southern and midland territories, but the north and west were yet to be subdued. He had been offered land in Camulodunum, which he accepted, but chose to continue his service in Rome rather than retiring after the requisite twenty years of service in Britain. Aside from despising the cold, damp climate of Britain, he had ambitions. Ambitions that could only be fulfilled in Rome. Ambitions that he hoped this Galerius Janius could help him fulfill.

“Sir,” one of the young men said, snapping Marcus out of his deep rumination.

They had reached the wealthier section of the city. Here the doorways were wider and the walls marble. The shops hid grand villas behind their walls whose owners rented the street front of their villas to merchants. This served a dual purpose. Besides bringing in a tidy sum in rents, the shops buffered the noise of the streets away from the living quarters. The villas were veritable oases in the heart of the city.

The sun’s rays dappled pink upon the neatly swept street and sidewalks, quiet but for the sound of iron bolts being opened and boards being stowed away, marking a new day for the shopkeepers.

As it was too late for shop carts and too early for chariot traffic, the street itself was deserted.

Except for Galerius Janius, who stood in the middle of the street before his massive villa, waiting.

“Marcus Sergius?” Janius said, stopping the Vigiles with an upraised hand. “My friend,” he said. “And how goes it with you this fine morning?”

His well-fed belly hung over the edge of his tightly belted tunic, and he balanced his carefully wrapped toga imperiously over his arm.

“Well, sir, and you?” A prickle of doubt ran through Marcus. Perhaps he should not have trusted this man. Had he been followed? Had someone seen that the baby was safe in her mother’s arms rather than in the place of exposure?

Marcus couldn’t imagine what had made Annia marry the man standing before him. Perhaps she had little choice. Perhaps it was a marriage arranged by her father.

Perhaps she had reason for the adultery of which she was accused.

“Yes, yes,” Janius said, measuring Marcus and then his men. “A fine crew you’ve assembled here.”

Marcus nodded. “Yes,” he said, “the emperor has very clear guidelines for the Vigiles. They must be able to fight fires as well as keep order in the streets. For this reason, the requirements of service are the same as for a legionary.” Why did he feel the need to defend his men against Galerius Janius?

“Really? How quaint,” Janius said. “Well, if you would like to come inside, I can pay you for your troubles.”

Janius headed into his house, confident that Marcus would follow.

When Marcus didn’t move, Janius turned. “You did follow my orders, did you not, soldier?” His eyes narrowed, and he looked more carefully at Marcus.

“I did,” Marcus said. Something in the window above caught his attention. But whatever it was moved away as soon as Marcus looked up.

“And was your little mission successful?” Janius asked.

“It was,” Marcus said, though the words were bitter in his mouth. To give this man satisfaction was more difficult than he imagined. He wanted to paint the true picture in painful detail for this man.

The baby Janius had ordered exposed, the baby Janius wished dead or enslaved, was safely ensconced in a villa even more lovely than this, being nursed, no doubt at this very moment by Annia herself.

What he had done was dangerous. If Janius discovered the truth, Marcus’s hopes of becoming prefect, or even an important member of the Praetorian Guard, would be destroyed.

“And was the little beauty snatched up by slave traders or eaten by dogs?” Janius snorted and laughed.

“I didn’t stay to see,” Marcus said affably, clutching his sword.

“Well, good, then,” Janius said. “The less offal on the streets of Rome, the better. I have no intentions of supporting an unfaithful woman’s spawn.”

Marcus’s hold on the gladius tightened. Janius noticed.

“Armed for warfare, are we?” he asked.

“Just habit, sir,” Marcus said, his voice affable still. “As you said, the less offal on the streets of Rome, the better.”

Janius’s eyes narrowed.

“Well then,” Janius said. “Good day.”

“Good day to you, sir,” Marcus said.

“Oh,” Janius said, turning around. “Here is a coin for your troubles.”

“No, thank you, sir. It was my duty. The baby had been ordered exposed at birth and was not. The law was broken. My men and I went in to correct a wrong. It is my job to be sure that the law is upheld.”

Janius looked at him, his head cocked to one side, as if he was gauging the truth of his answer.

“What a fine man of the law you are, then,” Janius said, the words dripping with sarcasm. “I will still keep my end of the bargain and recommend you for a promotion in rank.” His smile was wide, his eyes narrow.

Marcus’s expression was impassive.

The men waited as Janius turned again and walked into his house. As soon as the door closed, however, Marcus looked up and caught sight of two little brown eyes peering at him from the open window above the shops.

Clearly, this was Annia’s son. He had the same small features, the dark eyes, curly hair. He looked nothing like his father.

And based on the look of horror on his face, the little boy, who could be no more than ten years old, had heard the entire conversation.

Marcus wanted to tell the boy his baby sister was fine and his mother, too. But he had no way of doing so.

And the boy had clearly marked him as the enemy. The one responsible for taking his baby sister to her death.

Chapter Three

The woman, Scribonia, led Annia to her room. They climbed two flights of narrow wooden stairs, above the shops, above the shopkeepers’ quarters, into the very top floor of the villa.

Both Annia and Scribonia wore soft leather indoor sandals. So silent were their footsteps that Annia could hear the gentle breathing of babies as she walked by the rooms leading to hers.

Scribonia held her lantern high, parting the curtain that formed the door of the small room so that Annia could see her way in.

The room was bare but for a cradle, a small bed and a table.

Scribonia lit the candles in the bronze wall sconces and one on the small table beside the narrow wooden bed. Candlelight flickered on the mother-of-pearl shells inlaid in the wood, and played on the rich red damask bedcover.

It smelled pleasantly of rosemary, and brightly painted murals covered the walls. Annia would have to wait for the morning light to make out the images.

“We’ll talk in the morning,” Scribonia said. “You and your little one have been through quite the ordeal. I hope you find peace and rest here.”

She kissed Annia on the forehead, and Annia felt the tears well in her eyes. Scribonia kissed her as her mother might have.

The midwife disappeared down the hall, the curtain door fluttering behind her before Annia could think to express her gratitude.

And thank her son, Marcus.

How terribly embarrassing for her that she had not done so.

When Annia allowed herself to relax on the bed, she could not stop thinking of the look on Marcus’s face as he left the villa.

It was the look of a job well done. It satisfied him that she was here safe and sound with her baby.

Annia longed for someone who made her feel safe and protected. But she was afraid to hope for such a thing. To hope meant letting her guard down, and then who would protect her?

Her life for the past few months had been anything but safe and protected. Nothing was as it seemed. Could she really trust these seemingly kind people?

What did they want from her? Was it money? Power? Position? Annia was hardened by the excesses of those who had surrounded her since she came to Rome as a young bride.

Rome was vile. She had learned early to trust no one. Here, status and power ruled supreme. She would leave it as soon as she possibly could. She longed for friends and family that she could trust, those she had left behind in Britain. Here, Virginia had been her only true friend. Yet Virginia was also her slave.

As soon as she was able to do so, she would draw up papers for Virginia’s freedom.

Her baby girl nuzzled her breast, reminding her what was important.

She slept only a few hours before Maelia woke her with tiny snuffling sounds. The early morning sun shone a pale orange through the tiny window.

Scribonia knocked lightly, and Annia called her in.

“Good morning,” Annia said. “What would you like for me to do?”

Scribonia smiled wryly. “What can you do?”

“I can grow flax, I can take it from flax to linen, or I can harvest it for linseed oil or flaxseed. I can spin the yarn and weave it into cloth, and embellish it with embroidery.” The words tumbled from Annia’s mouth, and Scribonia’s smiling and nodding kept her talking.

“I can raise sheep and shear them. I can card wool and spin it, I can weave it and sew it. But the best thing I can do with wool is to make it repel water and to sew a birrus.”

“Do you mean you know how to make the hooded capes that soldiers treasure for their ability to insulate against the cold and rain?” Scribonia’s smile was joyous.

“Yes,” Annia said, “I can.”

“You are a child of many talents,” Scribonia said.

Annia blushed with pleasure at being called thus.

“I can also grow herbs, herbs that cure and herbs that make food taste good,” Annia said.

“But you are only one person,” Scribonia said. “You can’t do all of this here. Which is your favorite? Which do you prefer doing?”

Annia thought long and hard. “It’s a very difficult choice,” she said.

Scribonia laughed again. “Yes,” she said, “I’m guessing it must be. Most of the women here I must teach how to do the simplest things, but you, you could teach us all how to do many things.”

Annia smiled, and the warmth in her heart grew. It had been a very long time since she had been praised by someone who wasn’t her servant or her slave. It felt good.

She looked up at Scribonia and thought about how much she had smiled when she mentioned the birrus. “I think my favorite thing must be working with wool,” she said.

Her comment was met with a wide grin from Scribonia. “I was hoping you would say that. I would love for us to be able to make water-shedding capes for our people and maybe even sell some in the market. Why, that would give us enough money to add on to the villa and save more babies.”

“How did Janius discover Maelia lived?” Annia asked.

Scribonia was silent.

Annia filled in the silence. “I suspect it is because Rome is small, and the tongues of the gossips busy,” she said bitterly. “Someone told someone who then told Janius that my baby girl was alive. He couldn’t stand it, could he? His great fear was that his fortune would be divided among too many children. Once he ran through all of my money, he had to get rid of me and find another woman, one whose money and family connections could buy him the position he wanted.”

“Ah, yes, but don’t be bitter,” Scribonia said. “Because those very gossips who revealed the secret of your baby also revealed the secret of Janius ordering the baby to be exposed. And because of those gossips, I was able to make certain that Marcus was the man sent to do the deed.”

Annia blushed at the thought of Marcus and the trouble she had caused him.

Scribonia looked at her as if she read her mind. “Don’t worry. I knew you would fight for your baby. But I didn’t know you were trained as a fighter. I didn’t realize I was sending my son on a mission that might endanger his life—not from the slave traders, but from the baby’s mother.”

Her blue eyes danced, and Annia knew Scribonia liked her spirit.

“I am so sorry,” Annia said. “I had no idea.”

“Of course you didn’t, you poor child. You simply wanted to protect your baby. Now, let’s get started with your morning work.”

Scribonia called to a woman old in years, but the woman’s movement made her seem much younger than she was. “Basso, could you take Annia out back? She knows something about sheep.”

They walked through the villa past the lararium, the family altar that, in most Roman homes, was dedicated to the household gods. But in this home, Annia now knew, the altar was dedicated to the one God. They reached the inner garden surrounded by the marble-columned peristyle. The porch formed a shady area around the inner garden, protecting the rooms surrounding the garden from the harsh July sun.

In the outer garden, past the living quarters of the villa, was a second pool, this one much deeper and clearly meant for bathing or swimming.

She loved swimming. There was a river close to her home in Britain fed by a warm spring. She and her mother had loved bathing and swimming along its banks when the weather warmed. She hadn’t been swimming outside since she was a young girl. The possibility filled her with joy.

They walked through to the rear entrance of the villa. It opened out onto a large field.

Basso pointed to her right. There was a small pasture with a nice-size herd of sheep. Just below it was a round pen with three sad-looking sheep.

“We aren’t very good with sheep, it seems,” Basso said wryly, pointing to the three penned sheep. “I’m pretty sure these are badly in need of shearing.”

Annia laughed. “I’ll see what I can do.”

Beyond the sheep pen was a stream, fairly swiftly running. It eddied and swirled, and there were places where it grew large and then narrowed again.

“The stream is perfect for washing the wool,” Annia said.

“Really?” Basso said. “So far, it has been good for nothing but overflowing its banks during storms and giving us all a lot of extra backbreaking work.”

Annia could hardly wait to get started.

A young woman trailing a toddler walked up to her as she headed for the sheep pen. Annia stopped to greet her.

“I was hoping I would get to meet you soon,” the young woman said, her green eyes sparkling, her hands out to welcome Annia. She was a little taller than Annia, with bright red hair and a sprinkling of freckles. “You’re new. I’m so glad you are here. My name is Lucia. And yours?” Her words tumbled one on top of the other.

“Annia,” she said. “And this is Maelia.” Annia opened the sling, revealing the sleeping infant.

“Oh, she is lovely. I know you must be so proud.”

“I am,” Annia said. She looked around, surveying the walled garden, the vast fields, the stone fence.

“You are worried you were followed?” Lucia asked.

“Yes,” Annia said, “aren’t you?”

Lucia laughed. “No, not really,” she said. “This is Julius.”

Julius was a sturdy tot, well into his second year. He darted away from Lucia and ran as fast as his chubby legs would carry him to the sheep.

“You can’t imagine the trouble he’s gotten into,” Lucia confessed. “He’ll make a great soldier, though. He fears nothing. I named him Julius after the great conqueror and emperor.”

“He is wonderful,” Annia said, and meant it. Julius reminded Annia of her own two boys, and her heart pulled so hard that tears rose to her eyes.

Lucia didn’t notice. She had a watchful eye on Julius.

“Are you going to help with the sheep?” Lucia asked.

Annia nodded and smiled. “Yes, I’m eager to see them.” She arranged a soft bed for Maelia beneath the shade of an olive tree, using the baby sling for both cushion and cover.

Lucia led Annia to the pen. She opened the rickety gate and waited while Annia inspected their coats. They were well past shearing time.

“I wasn’t sure when to shear them,” Lucia said apologetically.

“Do not worry,” Annia said. “We will just need to take our time combing the wool.”

Lucia nodded solemnly.

The sound of dogs barking sent shivers down Annia’s spine. The sound continued. She looked at Lucia.

“They bark every time there is a visitor,” Lucia said. “You would be surprised at how good their hearing is. Why, I’ve been way back out in the olive grove, surrounded by the dogs, and the next thing I know, their ears are pricked up and they are bolting to the front entrance, barking the entire way.”

It hadn’t taken Janius long to find her, was all Annia could think. Maybe not. Maybe it was just a street vendor. Why would Janius want to find her anyway? Hadn’t he ordered her away and the baby disposed? Annia looked over at Maelia and then looked around for a safe hiding place.

But just then Annia heard a splash, then a plop. She recognized the sound, and then she heard thrashing. “Where’s Julius?” Annia yelled, torn between saving her own child from Janius and Julius from drowning.

Annia ran for the stream, looking for Julius. She thought she saw a tiny hand and ran for it. She yanked off her stola and stripped down to her linen shift.

She ran into the water and swam for the child, who had now disappeared under the water and was only visible by his thrashing.

The current had dragged him to the center.

Annia swam hard, then dove underwater where she thought he might be. The spring was clear, and the baby was struggling, his eyes open. He was paddling like a tiny dog trying to make his way to the top.

Annia snagged him and pulled him up, laughing with relief at the surprised look on his face.

He coughed a little, then tried to head back into the water. The little fish.

“You saved him,” Lucia said, snatching him up and hugging his sopping body to her chest, soaking her stola and nearly suffocating the child in the process. “I can’t swim,” she said to Annia. “He would have drowned if you hadn’t been here.” She began sobbing, and the little boy cried with her.

Even through the cacophony of the wailing sobs, Annia could hear the dogs barking. It was Galerius Janius after her. She was sure. She snatched up her clothes, wrapped Maelia in her sling and ran.

Chapter Four

The dogs signaled his arrival at his home. He heard them start their clamor when he was at the front of the villa.

His mother cleverly drugged the dogs on the nights he planned to bring home an exposed baby.

But at all other times, the dogs were loud and seemingly aggressive, though not really. They barked but then almost broke their backs wagging their tails and licking whoever walked through the front entrance.

Marcus looked over the tiled rectangular pool with its myriad fountains straight through to the tablinium, his father’s formal office and reception room. Framed on either side by marble columns, the peristyle garden formed its background. The impressive office was built by his grandfather during the reign of Augustus and was the place where clients came to speak with his father each morning.

Some came to borrow money, others came to lend, and some simply came to socialize. They sat in the long marble benches on either side of the impluvium, often lulled to sleep by the tinkling of the water as it trickled from the roof and flowed through the many fountains.

Marcus strode over the blue-and-white floor mosaic tiles and straight in to see his father.

“Ah, Marcus,” his father said, beaming when he saw him, rising from his massive ebony desk with its mother-of-pearl inlays and coming forward to embrace his son. “I will be glad when you can allow yourself to fully retire from the service,” he said.

“I would hardly consider being the head guard of the night watchmen service,” Marcus said.

“But you chose this profession,” his father responded.

“If there is ever anything I can help you with here...” Marcus started to say.

But his father held his hand up to stop his words. “No, no, my son. All of this I have under control. You choose your own life. Do not feel burdened by the obligations here. As of yet, there are none. I am hale and hearty and easily manage.”

And it was true. His father, Petronius Sergius, at fifty-seven years, managed very well on his own. His hair was white, but his body was in perfect shape. He exercised daily at the baths and was proud of his physique.

“Here,” his father said, “sit.” He pointed to one of the folding stools, and Marcus unfolded it and placed it in front of his father’s massive desk.

He sat and enjoyed the view of the brightly colored painting on the wall beside his father. The painting reached across the entire wall and featured a woman playing a lyre with her little boy looking over her shoulder.

“Your mother would like to have you home more, but I say build your own life. Any word of the new position?”

“I’ve heard nothing yet,” Marcus answered. “I’m starting to ask for favors from a few men who I think might be able to put in a good word with the emperor.”

“Be wary of those from whom you ask help,” his father said. “Remember, you will be in their debt.”

Marcus studied his father. Had word traveled back so quickly, then?

“I’ve enlisted the help of one Galerius Janius.”

“I’ve heard of the man,” his father said. “Cousin to the emperor through his new wife. Divorced his first wife on charges of adultery. What did he ask of you in return?”

Marcus looked down. How could he tell his father the truth? What had sounded like an easy deal at the time now seemed somehow corrupt.

“He asked that I take the baby born to his first wife to be exposed.”

His father tried to mask his shock. “And you agreed?” he asked, gripping the sides of his desk.

“I brought her here. It seemed harmless,” Marcus said. “If I exposed the baby, I knew the baby would live. If someone else did it, the baby would die.” He felt the blood rise to his face.

“And indeed, in a sense, it was harmless. But do you understand that your harmless idea may have endangered every woman and child in this house? Do you understand that a man like Galerius Janius trusts no one, as he himself is not trustworthy?”

“I’m sorry, Father. I had not considered the risk,” Marcus said. How could he have been so thoughtless?

“Were you followed?”

“No, not home,” he said. Had he been followed? He was certain he had not. Possibly to Gamus’s shop, but nowhere else.

“You are an experienced soldier. I trust that you know when you are being followed. I trust you to protect this house.”

“Yes, Father. I am sorry,” Marcus said.

“We will hope that there will be no repercussions on this particular escapade,” his father said. “We will speak of it no more.”

“Thank you, Father.” His father was the paterfamilias and was owed respect. Marcus had no trouble showing that respect. He felt it deeply.

“Eventually, this place will be yours,” his father said, his tone no longer chastising.

Marcus was relieved. “Yes, I know that, Father, but you and Mother have many, many good years left.”

His father laughed at this. “Your mother would like nothing more than to spend the rest of her days here saving babies. I can’t say that I blame her. Her work is good.”

Marcus raised his eyebrows at this. His father noticed.

“Father, I don’t mean any disrespect, but I’m not sure that saving a few babies is going to make a dent in the thousands of babies that are taken into slavery.” The words that had been swirling around in his brain had finally found a voice. Marcus felt uncertain about his thoughts.

“You may be right,” his father said, without judgment. “But we are called to help those within our reach. If everyone could just help those that are put in front of them, think of what a wonderful world we would live in.”

Marcus considered his father’s words. Was he right?

“When I was a young man,” his father continued, “I felt the same way you do, son.”

Marcus’s eyes widened in surprise. It made him feel better that even his father had doubted.

“But as I get older,” his father said, “I understand God’s call on our lives to be less grand and, instead, very personal. We are called to minister to the ones God puts right in front of us. And we are wrong to give up because we can’t save the entire world. We may not end infant exposure in the Roman Empire, but each life we save is precious.”

“I hadn’t thought about it like that,” Marcus said.

His father nodded. “I hope one day to retire to the estate in Britain. I wouldn’t mind going home to finish out my days.”

His father had been born in Britain, where his father’s grandfather had arrived with Julius Caesar and decided to stay. His grandfather had established a thriving trade between Rome and Britain, and maintained a villa in both places. Marcus’s father brought his mother to Britain to help manage the estate built on land that had been bought with olive oil. He liked the simplicity of life in Britain.

“How was our villa in Britain when you saw it last?” his father asked.

“Prospering,” Marcus said. “The crops were thriving, the sheep reproducing and making enough wool to make an army of capes.”

“If only we had someone who knew the secret of making those capes,” his father said. “We could make a fortune.”

They strode out the back garden and into the field beyond. Marcus wanted no listening ears around when he spoke with his father about Annia.

But his father was called back by a client and was forced to return to his office.

Marcus would have to wait.

He looked out over the fields, hoping to catch a glimpse of Annia. He wasn’t certain, but he had a feeling she would be drawn to the fields, and not to the work inside the house.

“Are you looking for something, master?” It was Basso. Her wise old eyes missed nothing.

“The young woman I brought in last night. Is she well?”

“Yes, your mother set her to work with the sheep.” Basso smiled.

“The sheep?” Marcus asked. It seemed an odd assignment.

“Yes, at her request. It seems she was raised in Britain and knows something about sheep.”

Marcus remembered the street skirmish. She had fought like one of the blue-skinned warriors, though minus the poisoned darts. He scanned the field but didn’t see her.

“Thank you, Basso,” he said. “Your flowers are, as usual, the pride of the family garden.”

She smiled appreciatively. “It’s a tricky business,” she said, “tending medicinal herbs. Some must flower to unleash their healing powers, and some must not. I have to be aware of each individual plant, and watch them as if they were a yard of two-year-olds.”

Marcus laughed, and Basso turned back to tend the flowering medicinal herbs in the inner garden.

He was glad she turned. Marcus didn’t want Basso to see his fast gait and guess how much he wanted to see the girl again.

But nothing escaped the notice of Basso. “Why so eager?” she called out to him.

Marcus had to smile.

“I like sheep,” he said, laughing.

“Is that it?” she said, and chuckled. “Go along with you, then.”

He walked to the sheep pen, but the only one there was young Lucia and her waterlogged toddler, Julius.

“Well, little Julius,” Marcus said, bending down to talk to the little boy who seemed not the least bit disturbed by his sodden state. “What happened?”

The boy stuck his thumb in his mouth and gazed solemnly back at Marcus.

“He fell in our spring-fed stream, and thank God, Annia can swim. She saved him.”

Julius sucked his thumb and nodded, waving his fingers for emphasis.

Marcus laughed, but was immediately sober. “How frightening that must have been for you,” he said to Lucia.

“Not really,” Lucia said. “The truth is, I didn’t even realize what had happened until Annia fished him out.”

“Where is Annia?” Marcus asked as casually as he could muster.

“I don’t know. She gave Julius back to me, said something about dogs barking and then snatched up her baby and sprinted for the olive groves. The woman is like no one I’ve ever met. She swims like a fish and runs like the wind. Who is she, really, and where is she from?”

“That, my friend, is a very good question,” Marcus said. The less the women knew about one another, the safer they all were.

“Well, when you find her, let me know,” Lucia said. “I need her to teach me how to take care of the sheep.”

“It looks as though you’ve got your hands full looking after your own little lamb,” Marcus said, indicating Julius. “Are you sure you don’t want to find something inside the inner garden to do? Might it be safer there for your little one?”

”Perhaps I should consider harvesting the flax. That field is the farthest away from the water,” Lucia said, shaking her head.

Marcus laughed and headed toward the olive grove. The silvery-green leaves and gnarled trunks comforted Marcus. He had spent many happy boyhood days in the shady grove, imagining himself a soldier.

“Annia?” he called, but there was no answer. He walked among the trees. Where could she be, and why would she be hiding?

The olives would not be ready to harvest for another two months. What could she be doing out here?

He thought again about what Lucia had said about Annia hearing dogs barking and understood her fear.

Just then he heard the baby cry, a tiny mew, followed immediately by Annia. “Shh,” she whispered, “it’s all right.”

She was very close.

“Annia,” he said, and heard her sharp intake of breath. “I am alone. No one else is here. The dogs bark at everyone who comes to the front gate for my father. No one knows who you are but my mother and me. Please don’t be afraid.”

Annia crept out from behind an olive tree, her infant in her arms. He wanted to comfort her.

“And how do I know I can trust you?” she asked, her eyes dark and serious.

“I don’t know how to prove myself to you,” he said, calmly, evenly, looking deeply into her soft brown eyes. “All I can say is you must try to trust me.”

His encounter with Janius gave him some insight into her fear. Most of the women felt safe and secure behind the thick concrete-covered stone walls of the villa. He wondered if Annia would ever feel safe.

She looked at him warily. Then glanced beyond him—it seemed she needed to verify the truth of his words.

Her gaze returned to study him. Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, she nodded. “All right,” she said. “I think I can do that.”

He relaxed a bit and was suddenly overcome with a very uncharacteristic lack of assurance as to what he should say next.

But she spoke for him. “Now,” she said, “why don’t you come help me shear some sheep?”

Just like that, she shifted from a frightened deer to a cheerful companion. He admired her verve.

He laughed, and tired though he was, he followed her to the sheep. There would be plenty of time for sleeping in the afternoon. For now, he was going to enjoy her company and maybe learn something about shearing sheep.

And he was going to think of a way to put Janius off the trail of this woman and her baby. Permanently.

Chapter Five

The presence of Marcus calmed her, and she was able to focus on the task at hand. Shearing sheep.

The shears were dull. Annia sent Lucia to the kitchen with them and a request to have the cook sharpen the shears with her stone.

Lucia was happy to get Julius as far away from the stream as possible.

Meanwhile, Annia directed Marcus in the fine art of sheep bathing.

“We have to bathe them before we shear them,” she said. “We need to get rid of all the excess matter in their coats that might dull the shears.”

Apparently, whoever had been in charge of the sheep had not paid attention to this nicety.

“That sounds reasonable,” Marcus said, nodding agreeably and awaiting further instructions. She liked that he was willing to learn from her. Most men resisted instruction from a female.

“Where is your sheepdog?” Annia asked.

Marcus seemed surprised by the question. “I think all the dogs are in the atrium,” he said.

“Not those dogs,” Annia said, “your sheepdog. The one that is trained to herd sheep.”

“I don’t think we have an actual sheepdog,” Marcus said. “Our coin comes from olive oil, not sheep. I think all of our sheepdogs are in Britain.”

She raised a quizzical eyebrow but didn’t have time to question him further about her homeland. Instead, she had a challenge in front of her. One that was proving to be more difficult than she expected. She tried to remember if she had ever bathed sheep in a stream without a sheepdog helping her.

She hadn’t.

“Well, it looks as though you’re chosen,” she said to Marcus.

“Chosen for what?” he asked.

“To be the sheepdog,” she said.

She hoped he was as affable as he pretended to be. If not, this was going to get very interesting very quickly.

“You are going to run behind those bedraggled creatures you call sheep and drive them, one at a time, into the stream.”

He looked at her for a moment and then burst out laughing. “You want me to play the sheepdog?”

“Yes,” she said, smiling.

Marcus shook his head. “I’ve done many things for women. But never this. Pretending to be a sheepdog to these bedraggled sheep?” he said, cocking his head to one side and grinning.

”Yes,” she said, then continued her instructions. “When I finish giving the beast a quick dunk in the spring, you are going to need to drive her right back into the pen.”

Marcus grinned. “Are you trying to make a fool out of me, or is this what must happen?”

Annia smiled. He really had never worked with sheep.

“Well, you may look a little foolish,” she said, “but the sheep will be washed and ready for shearing.”

Annia was quick to fashion a hanging cradle for baby Maelia.

First, she removed the bronze pin that secured the long, blanketlike palla to the shoulder of her short-sleeved shift, her stola.

Scribonia’s gift, the palla, was long and octagonal, made of a finely woven lightweight wool. It was perfect for fashioning into a makeshift cradle on the lowest branch of an ancient olive tree that grew alone a few yards from the stream.

She felt Marcus’s admiring eyes on her makeshift cradle, and had to laugh.

“Is there anything you can’t do?” he asked.

“You are very easily impressed,” she said, “that or you haven’t been around many mothers with babies. Though when I think about it that seems odd since your mother has a house full of them.”

“I haven’t been here long,” Marcus said.

“Really?” Annia said. “I thought you were born and raised here.”

“Off and on,” Marcus said. “But I joined the service as soon as I could, a bit before my seventeenth year. I finished my twentieth year in the service this year and came home to plan what I will do next.”

“And what will that be?” Annia asked, hoping in spite of herself that it would be something close by.

Ironically, this man—who had come to her private abode with an armed guard to take her baby—made her feel safe.

“I don’t know yet,” he said. “Now, tell me which sheep you want to start with.”

Annia turned her attention back to the sheep. It was clear he did not want to talk about his future plans.

Was it because there was a woman involved? Was he promised in marriage to someone?

It made sense. He was young and handsome enough to land any woman he wanted. His parents probably had the perfect young woman picked out for him.

Why should she care? She shouldn’t. But she did. She would like to know that this man, whose company she was beginning to enjoy, was not thinking about another woman.

Stop this foolishness. You will never remarry. You don’t want to. You aren’t interested in men. Marriage was the most miserable state you’ve ever experienced. You were forced to be with a man who didn’t love you, who said you looked like an elf, not a woman, who kept you only for your dowry.

She shook off that downhill spiral of thoughts, shed her stola and marched down to the stream clothed only in her tunic.

She found a sandbar and positioned herself on it.

“All right,” she said, “send in the first victim.”

Marcus walked into the pen and chose the closest sheep.

He positioned himself behind the dirty sheep and pushed her forward.

She circled back around behind him.

He tried it again.

The sheep circled around behind him.

He looked up to see Annia laughing at him.

“You think this amusing?” he yelled, positioning himself behind the sheep once again.

His yelling had an unintended effect. The startled sheep surged forward. He bolted with her, and all the other sheep followed.

The sheep lopped along wildly in the opposite direction from the stream.

“You make a poor sheepdog,” Annia said, laughing until tears streamed down her cheeks.

He ran to catch up with the sheep and tried herding them as if he were a sheepdog, barking orders behind them, “Move, go, go.” Finally steering them all back into the pen so he could start all over again and perhaps get it right.

Once inside the pen, he looked over at Annia, who was still laughing. “I think I can do it now,” he said, laughing with her.

This time, he was careful to position himself behind one sheep and slam the gate quickly behind himself before the other two escaped.