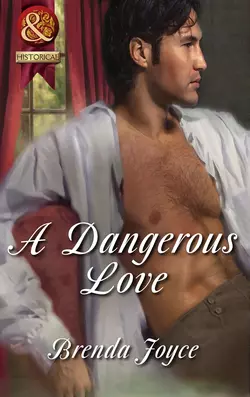

A Dangerous Love

Brenda Joyce

A Dangerous ObsessionWealthy and powerful, Viscount Emilian St Xavier is haunted by whispers of his Romany past. When his comfortable world implodes with the news of his mother’s murder, he is determined to avenge her death – and Ariella de Warenne is the perfect object for his lust and revenge…A Dangerous Passion Ariella’s heritage guarantees her place in proper society, though she scorns the frivolous pursuits of the ton. Then she finds herself drawn to Emilian, the charismatic leader of the gypsy camp at Rose Hill.Though he warns her away, threatening to seduce and destroy her, she stubbornly refuses – just as determined to fight for their dangerous love…

Ariella now heard him speakingto the Gypsies in their strange,Slavic-sounding tongue. His tonewas one of command. InstantlyAriella knew he was their leader.

And then the Gypsy leader looked at them. Cold grey eyes met hers and her breath caught. He wasso beautiful. His piercing eyes were impossibly long lashed, and set over strikingly high, exotic cheekbones. His nose was straight, his jaw hard and strong. She had never seen such masculine perfection in her entire life.

Of course he wasn’t English. He was too dark, too immodestly dressed and his hair was far too long, brushing his shoulders. Tendrils were caught inside his open collar, as if sticking to his wet skin.

She flushed but couldn’t stop staring. Her gaze drifted to a full but tense mouth. She glimpsed a gold cross he wore, against the dark, bronzed skin of his chest. In the fine silk shirt, she could even see his chest rising and falling, slow and rhythmic. Her glance went lower. The doeskin breeches clung to his thick, muscular thighs and narrow hips, delineating far too much male anatomy.

She felt his eyes on her; she looked up and met his gaze a second time.

Ariella flamed. Knowing she had been caught, she looked quickly away. What was wrong with her?

“I am Emilian. You will speak to me,” he said, a slight accent hanging on his every word.

Brenda Joyce is the bestselling author of more than thirty novels and novellas. She wrote her first novella when she was sixteen years old and her first novel when she was twenty-five – and was published shortly thereafter. She has won many awards and her first novel, Innocent Fire, won the Best Western Romance Award. She has also won the highly coveted Best Historical Romance award for Splendor and the Lifetime Achievement Award from Romantic Times. She is the author of the critically acclaimed DEADLY series, which is set in turn-of-the- century New York and features amateur sleuth Francesca Cahill. There are over eleven million copies of her novels in print and she is published in more than a dozen countries. A native New Yorker, she now lives in southern Arizona with her husband, son, dogs, cat and numerous Arabian and half- Arabian reining horses. For more information about Brenda and her forthcoming novels, please visit her website at www.brendajoyce.com.

A Dangerous Love

Brenda Joyce

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

PROLOGUE

Derbyshire, 1820

HIS AGITATION KNEW no bounds. What the hell was taking the runner so long? He’d received Smith’s letter the day before, but it had been brief, stating only that the runner would arrive on the morrow. Damn it! Had Smith succeeded in finding his son?

Edmund St Xavier paced the length of his great hall. It was a large room, centuries old like the house itself, but sparsely furnished and in need of a great deal of repair. The damask on the single sofa was badly faded and torn, a scarred trestle table demanded far more than wax and a shine, and the gold and ivory brocade that covered the chairs had long since turned that unpleasant shade of yellow that indicated aging and a serious lack of economy. Once, Woodland had been a great estate, compromising ten thousand acres, when Edmund’s ancestors had proudly borne the title of viscount and had kept another splendid home in London. Now a thousand acres remained, and of the fifteen tenant farms scattered about, half were vacant. His stable consisted of four carriage horses and two hacks. His staff had dwindled to two manservants and a single housemaid. His wife had died in childbirth five years ago, and last winter, a terrible flu had taken their only child. There was only an impoverished estate, an empty house and the prestigious title, which was now in jeopardy.

Edmund’s younger brother stared at him from across the hall, as smug and cocksure as always. John was certain the title would soon pass to him and his son, but Edmund was as determined that it would not. For there was another child, a bastard. Surely Smith had found him.

Edmund turned stiffly away. They’d been rivals growing up and they remained rivals now. His damned brother had made a small fortune in trade and owned a fine estate in Kent. He regularly appeared at Woodland in his six-in-hand, his wife awash in jewels. Every visit was the same. He would walk around the house, inspecting each crack in the wooden floors, each peeling patch of paint, every musty drapery and dusty portrait, his disgust clear. And then he would offer to pay his debts—with a sizable interest rate. Edmund could not wait until John departed—leaving behind his high-interest note, which he’d signed, having no other choice.

He’d die before seeing John’s young son, Robert, inherit Woodland. But dear God, it wasn’t going to come to that.

“Are you certain Mr. Smith found the boy?” John inquired, his words dripping condescension. “I cannot imagine how a Bow Street runner could locate a particular Gypsy tribe, much less the particular woman.”

He bristled. John was enjoying himself. He scorned Edmund’s affair with a Gypsy and believed the boy would be a savage. “They winter by the Glasgow shipyards,” Edmund said. “In the spring they journey into the Borders to work in the fields. I doubt it was all that hard to find this caravan.”

John walked to his wife, who sat sewing by the fire, and put his hand on her arm, as if to say, I know this is a distressfultopic for you. No lady should have to comprehend thatmy brother had a Gypsy lover.

His perfect, pretty wife smiled at him and continued to sew.

Edmund couldn’t help thinking of Raiza now. Ten years ago she’d appeared at Woodland with their son, her eyes ablaze with the pride and passion he still vividly remembered. He had been shocked to look at the child and see his own gray eyes reflected in that darkly complexioned face. The boy’s hair had been a dark gold, while Raiza was as dark as the night. Edmund himself was fair. His wife, Catherine, was in the house, pregnant with their child. He’d insisted the bastard was not his—hating himself for doing so. But his affair with Raiza had been brief and he loved his wife. He could not ever let her know about the boy. He had offered Raiza what little coin he could, but she had cursed him and left.

As if reading his mind, John said, “How can you be certain the boy is even yours, no matter what the wench claimed?”

Edmund ignored him. He’d been at a house party in the Borders, hunting with a group of bachelor friends, when the Gypsies had first appeared, camping not far from the local village. He’d walked past Raiza in the town and when their eyes had met, he’d been so stricken that he had reversed direction, following her as if she were the Pied Piper. She had laughed at him, flirting. Smitten, he had eagerly pursued her. Their affair had begun that night. He’d stayed in the Borders for two weeks, spending most of that time in her bed.

He’d wanted to stay with her even longer, but he had a floundering estate to run. With tears of regret in her eyes, Raiza had whispered, “Gadje gadjense.” He didn’t understand her, but he thought she was in love with him, and he wasn’t sure that he didn’t love her, too. Not that it mattered, for they were from two completely different worlds. He hadn’t expected to ever see her again.

A year later he had met Catherine, a woman as different from Raiza as night and day. The niece of his rector, she was proper, demure and impossibly sweet. She would never dance wildly to Gypsy music beneath a full moon, but he didn’t care. He had fallen in love with her, married her and become her dearest friend. He missed her even now.

He intended to remarry, of course, because he hoped for more heirs. He could not risk the estate. But he had learned firsthand how capricious life was, how uncertain. And that was why he had decided to find his bastard son.

Edmund heard the sound of horses arriving outside in the rutted dirt drive.

He rushed to the front door, aware of John following him, and flung it open. The heavyset runner was alighting from the carriage, a single-horse curricle. The damned shades were pulled down. “Have you found him?” Edmund cried, aware of his desperation. “Have you found my son?”

Smith was a big man who clearly did not like to shave on a daily basis. He spit tobacco at him and grinned. “Aye, me lord, but ye might not want to thank me yet.”

He had found the boy.

John came to stand beside him. He murmured, “I don’t trust the Gypsy wench at all.”

His gaze glued to the carriage, Edmund retorted, “I don’t care what you think.”

Smith strode to the carriage, pulling open the door. He reached inside and Edmund saw a lean boy in patched brown trousers and a loose, dirty shirt. Smith jerked him out and to the ground. “Come meet yer father, boy.”

Horrified, Edmund saw that the boy’s wrists were tightly bound with rope. “Untie him,” he began, when he saw the chain and shackle on his ankle.

The boy jerked free of Smith, hatred on his pinched face. He spat at him.

Smith wiped the spittle from his cheek and glanced at Edmund. “He needs a whipping—but then, he’s a Gypsy, ain’t he? Flogging’s what they understand, just like a rotten horse.”

Edmund began to shake with outrage. “Why is he bound and shackled like a felon?”

“’Cause he’s treacherous, he is. He’s tried to escape a dozen times since I found him in the north, an’ I don’t feel like being stabbed to death in me sleep,” Smith said. He seized the boy by the shoulder and shook him. “Yer father,” he said, gesturing at Edmund.

There was murderous rage in the boy’s eyes, but he remained silent.

“He speaks English, just as good as you an’ me.” Smith spit more tobacco, this time on the boy’s dirty bare feet. “Understands every word.”

“Untie him, damn it,” Edmund said, feeling helpless. He wanted to hold his son and tell him he was sorry, but this boy looked as dangerous as Smith claimed. He looked as if he hated Smith—and Edmund. “Son, welcome to Woodland. I am your father.”

Cool gray eyes held his, filled with condescension. They belonged to an older man, a worldly man, not a young boy.

Smith said, “She gave him up without too much of a fuss.”

Edmund could not look away from his son. “Did you give her my letter?”

Smith said, “Gypsies can’t read, but I gave her the letter.”

Had Raiza agreed that his raising their son was for the best? As an Englishman, a world of opportunity was open to him. And he was entitled to this estate, his title and all the privilege that came with it.

“But she wept like a woman dying,” Smith said, unlocking the shackle on the boy’s ankle. “I couldn’t understand their Gypsy speech, but I didn’t have to. She wanted him to go—and he didn’t want to leave. He’ll run off.” Smith looked at Edmund in warning. “Ye’d better lock him up at night an’ keep a guard on him by day.” He seized his arm. “Boy, show respect to yer father—a great lord. If he speaks, ye answer.”

“It’s all right. This is a shock.” Edmund smiled at his son. God, he was a beautiful boy—except for his eyes and coloring, he looked exactly like Raiza. So much warmth began, flooding his chest. He should have never turned Raiza away so many years ago, he thought. But surely they could get past what he had done. Surely they could get past this terrible beginning and their differences. “Emilian,” he smiled. “Long ago, your mother brought you here and introduced us. I am Lord Edmund St Xavier.”

The boy’s expression did not change. He reminded Edmund of a deadly, darkly golden tiger, waiting for the precise moment to leap and maim.

Taken aback, Edmund reached for the ropes on his wrists. “Give me a knife,” he said to Smith.

“Ye’ll be sorry,” Smith said, handing him a huge blade.

John murmured, “The boy is as feral as I expected.”

Edmund ignored both comments, cutting the ties. “That must feel better.” But the boy’s wrists were lacerated. He was furious with the runner now.

The boy stared coldly. If his wrists hurt, he gave no sign— and Edmund knew he wouldn’t.

“Better guard your horses,” John murmured from behind them, a snicker in his tone.

Edmund did not need his smug brother’s presence now. Getting past his son’s hostility was going to be difficult enough. He couldn’t begin to imagine how he’d turn him into an Englishman, much less become a real father to him.

The boy had become still, staring closely, his expression wary. Edmund almost felt as if he were looking at a wild animal, but John was wrong, because Gypsies weren’t beasts and thieves—he knew that firsthand. “Can you speak English? Your mother could.”

If the boy understood, he gave no sign.

“This is your life now,” Edmund tried with a smile. “Long ago, your mother brought you here. I was a fool. I was afraid of what my wife would say, do. I turned you away—and for that, I will always be sorry. But Catherine is gone, God bless her. My son Edmund—your brother—is gone. Emilian, this is your home now. I am your father. I intend to give you the life you deserve. You are an Englishman, too. And one day, Woodland will be yours.”

The boy made a harsh sound. He looked Edmund up and down with scorn and shook his head. “No. I have no father— and this is not my home.”

His English was accented, but he could speak. “I know you need some time,” Edmund cried, thrilled they were finally speaking. “But I am your father. I loved your mother, once.”

Emilian stared at him, his face twisted as if with hatred.

“This has to be a difficult moment, meeting your father and accepting that you are my son. But Emilian, you are as much an Englishman as I am.”

“No!” Emilian snarled. And he said proudly, head high, “No. I am Rom.”

CHAPTER ONE

Derbyshire, the spring of 1838

SHE WAS SO ENGROSSED in the book she was reading that she didn’t really hear the knocking on her door until it became pounding. Ariella started, curled up in a canopied four-poster bed, a book about Genghis Khan in her hands. For one more moment, visions of a thirteenth-century city danced in her mind, and she saw well-dressed upper-class men and women fleeing in panic amidst artisans and slaves, as the Mongol hordes galloped through the dusty streets on their warhorses.

“Ariella de Warenne!”

Ariella sighed. She had been able to smell the battle, as well as see it. She shook the last of her imaginings away. She was at Rose Hill, her parent’s English country home; she had arrived last night. “Come in, Dianna,” she called, setting the history aside.

Her half sister, Dianna, her junior by eight years, hurried in and stopped short. “You’re not even dressed!” she exclaimed.

“I can’t wear this gown to supper?” Ariella said with mock innocence. She didn’t care about fashion, but she did know her family, and at supper the women wore evening dresses and jewels, the men dinner jackets.

Dianna’s eyes popped. “You wore that dress to breakfast!”

Ariella slid to her feet, smiling. She still couldn’t get over how much her little sister had matured. A year ago, Dianna had been more child than woman. Now it was hard to believe she was only sixteen, especially clad in the gown she was wearing. “Is it that late?” Vaguely, she glanced toward the windows of her bedroom and was surprised to see the sun hanging low in the sky. She had settled down with her tome hours ago.

“It is almost four and I know you know we are having company tonight.”

Ariella did recall that Amanda, her stepmother, had mentioned something about supper guests. “Did you know that Genghis Khan never initiated an attack without warning? He always sent word to the countries’ leaders and kings asking for their surrender first, instead of simply attacking and slaying everyone, as so many historians claim.”

Dianna stared, bewildered. “Who is Genghis Khan? What are you talking about?”

Ariella beamed. “I am reading about the Mongols, Dianna. Their history is incredible. Under Genghis Khan, they formed an empire almost as large as that of Great Britain. Did you know that?”

“No, I did not. Ariella, Mother has invited Lord Montgomery and his brother—in your honor.”

“Of course, today they inhabit a far smaller area,” Ariella said, not having heard this last bit. “I want to go to the Central Steppes of Asia. The Mongols remain there today, Dianna. Their culture and way of life is almost unchanged since the days of Genghis Khan. Can you imagine?”

Dianna grimaced and walked to a closet, pushing through the hanging gowns there. “Lord Montgomery is your age and he came into his title last year. His brother is a bit younger. The title is an old one, the estates well run. I heard Mother and Aunt Lizzie talking about it.” She pulled out a pale blue gown. “This is stunning! And it doesn’t look as if you have worn it.”

Ariella didn’t want to give up on her sister yet. “If I give you this history to read, I am certain you will enjoy it. Maybe we can all go to the steppes together! We could even see the Great Wall of China!”

Dianna turned and stared.

Ariella saw that her little sister was losing patience. It was always hard to remember that no one, not even her father, shared her passion for learning. “No, I haven’t worn the blue. The supper parties I attend in town are filled with academics and Whig reformers, and there are few gentry there. No one cares about fashion.”

Holding the gown to her chest, Dianna shook her head. “That is a shame! I am not interested in Mongols, Ariella, and I cannot truly understand why you are. I am not going to the steppes with you—or to some Chinese wall. I love my life right here! The last time we spoke, you were in a tizzy about the Bedouins.”

“I had just returned from Jerusalem and a guided tour of a Bedouin camp. Did you know that our army uses Bedouins as scouts and guides in Palestine and Egypt?”

Dianna marched to the bed and laid the gown there. “It’s time you wore this lovely dress. With your golden complexion and hair and your infamous de Warenne blue eyes, you will turn heads in it.”

Ariella stared, instantly wary. “Who did you say was coming?”

Dianna beamed. “Lord Montgomery—a great catch! They say he is also handsome.”

Confused, Ariella folded her arms across her chest. “You’re too young to be looking for a husband.”

“But you’re not,” Dianna cried. “You didn’t hear me, did you? Lord Montgomery has just come into his title, and he is very good-looking and well educated. I have heard all kinds of gossip that he is in a rush to wed.”

Ariella turned away. She was twenty-four now, but marriage was not on her mind. Ever since she was a small child, she had been consumed with a passion for knowledge. Books—and the information contained within them—had been her life for as long as she could remember. Given a choice between spending time in a library or at a ball, she would always choose the former.

Luckily, her father doted on her and encouraged her intellectual pursuits—and that was truly unheard of. Since turning twenty-one, she had resided mostly in London, where she could haunt the libraries and museums, and attend public debates on burning social issues by radicals like Francis Place and William Covett. But despite the freedoms, she wished for far more independence—she wanted to travel unchaperoned and see the places and people she had read about.

Ariella had been born in Barbary, her mother a Jewess enslaved by a Barbary prince. She had been executed shortly after Ariella’s birth for having a fair-skinned child with blue eyes. Her father had managed to have Ariella smuggled out of the harem and she had been raised by him since infancy. Cliff de Warenne was now one of the greatest shipping magnates of the current era, but in those days, he had been more privateer than anything else. She had spent the first few years of her life in the West Indies, where her father had a home. When he met and married Amanda, they had moved to London. But her stepmother loved the sea as much as Cliff did, and by the time Ariella came of age, she had traveled from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, up and down the coast of the United States, and through the major cities of Europe. She had even been to Palestine, Hong Kong and the East Indies.

Last year there had been the three-month tour to Vienna, Budapest and then Athens. Her father had allowed her this trip, with the condition her half brother escort her. Alexi was following in their father’s footsteps as a merchant adventurer, and he had been happy to chaperone her and briefly detour to Constantinople, upon her request.

Her favorite land was Palestine, her favorite city Jerusalem; her least favorite, Algiers—where her mother had been executed for her affair with Ariella’s father.

Ariella knew she was fortunate to have traveled a good portion of the world. She knew she was fortunate to have lenient parents, who trusted her implicitly and were proud of her intellect. It was not the norm. Dianna was not educated; she only read the occasional romance novel. She spent the Season in London, the rest of the year in their country home in Ireland, living a life of leisure. Except for charity, her days were spent changing attire, attending lavish meals and teas, and calling on neighbors. It was usual for a well-bred young woman.

Soon, Dianna would be put on the marriage market, and she would hunt for the perfect husband. Ariella knew her beautiful sister, an heiress in her own right, would have no problem becoming wed. But Ariella wished for a far different life. She preferred independence, books and travel to marriage. Only a very unusual man would allow her the freedom she was accustomed to and she couldn’t quite imagine answering to anyone, not when she had such independence now. Marriage had never seemed important to her, although she had grown up surrounded by great love, devotion and equality, exemplified in the marriages of her aunts, uncles and parents. If she ever did marry, she knew it would only be because she had found that great and unusual love, the kind for which the de Warenne men and women were renowned. Yet at twenty-four, it seemed to have escaped her—and she didn’t feel lacking. How could she? She had thousands of books to read and places to see. She doubted she could accomplish all she wished to in a lifetime.

She slowly faced her sister.

Dianna smiled, but with anxiety. “I am so glad you are home! I have missed you, Ariella.” Her tone was now coaxing.

“I have missed you, too,” Ariella said, not quite truthfully. A foreign land, where she was surrounded by exotic smells, sights and sounds, facing people she couldn’t wait to understand, was far too exciting for nostalgia or any homesick emotion. Even in London, she could spend days and days in a museum and not notice the passage of time.

“I am so glad you have met us at Rose Hill,” Dianna said. “Tonight will be so amusing. I met the younger Montgomery, and if his older brother is as charming, you might very well forget about Genghis Khan.” She added, “I don’t think you should mention the Mongols at supper, Ariella. No one will understand.”

Ariella hesitated. “In truth, I wish it were just a family affair. I cannot bear an evening spent discussing the weather, Amanda’s roses, the last hunt or the upcoming horse races.”

“Why not?” Dianna asked. “Those are suitable topics for discussion. Will you promise not to speak of the Mongols and the steppes, or supper parties with academics and reformers?” She smiled, but uncertainly. “Everyone will think you’re a radical—and far too independent.”

Ariella balked. “Then I must be allowed absolute, ungracious silence.”

“That is childish.”

“A woman should be able to speak her mind. I speak my mind in town. And I am somewhat radical. There are terrible social conditions in the land. The penal code has hardly been changed, never mind the hoopla, and as for parliamentary reform—”

Dianna cut her off. “Of course you speak your mind in town—you aren’t in polite company. You said so yourself!” Dianna stood, agitated. “I love you dearly. I am asking you as a beloved sister to attempt a proper discourse.”

Ariella groused, “You have become so conservative. Fine. I won’t discuss any subject without your approval. I will look at you and wait for a wink. No, wait. Tug your left earlobe and I will know I am allowed to speak.”

“Are you making a mockery of my sincere attempts to see you successfully wed?”

Ariella sat down, hard. Her little sister wished to see her wed so badly? It was simply stunning.

Dianna smiled coaxingly. “I also think you should not mention that Papa allows you to live alone in London.”

“I’m rarely alone. There is a house full of servants, the earl and Aunt Lizzie are often in town, and Uncle Rex and Blanche are just a half hour away at Harrington Hall.”

“No matter who comes and goes at Harmon House, you live like an independent woman. Our guests would be shocked—Lord Montgomery would be shocked!” She was firm. “Father really needs to come to his senses where you are concerned.”

“I am not entirely independent. I receive moneys from my estates, but Father is the trustee.” Ariella bit her lip. When had Dianna become so proper? When had she become exactly like everyone else her age and gender? Why couldn’t she see that free thinking and independence were states to be coveted, not condemned?

Dianna smoothed the gown on the bed. “Father is so smitten with you, he can’t see straight. There is some gossip, you know, about your residing in London without family.” She looked up. “I love you. You are twenty-four. Father isn’t inclined to rush a match, but you are of age. It is time, Ariella. I am looking out for your best interests.”

Ariella was dismayed. It was time to set her sister straight about Lord Montgomery. “Dianna, please don’t think to match me with Montgomery. I don’t mind being unwed.”

“If you don’t marry, what will you do? What about children? If Father gives you your inheritance, will you travel the world? For how long? Will you travel at forty? At eighty?”

“I hope so,” Ariella cried, excited by the notion.

Dianna shook her head. “That’s madness!”

They were as different as night and day. “I don’t want to get married,” Ariella said firmly. “I will only marry if it is a true meeting of the minds. But I will be polite to Lord Montgomery. I promised you I won’t speak of the matters I care about, and I won’t—but dear God, cease and desist. I can think of nothing worse than a life of submission to some closed-minded, proper gentleman. I like my life just as it is.”

Dianna was incredulous. “You’re a woman, Ariella, and God intended for you to take a husband and bear his children—and yes, be submissive to him. What do you mean by a meeting of the minds? Who marries for such a union?”

Ariella was shocked that her sister would espouse such traditional views—even if almost all of society held them. “I do not know what God decreed for women—or for me,” she managed. “Men have decreed that women must marry and bear children! Dianna, please try to understand. Most men would not let me roam Oxford, in the guise of a man, eavesdropping on the lectures of my favorite professors.” Dianna gasped. “Most men would not allow me to spend entire days in the archives of the British Museum,” Ariella continued firmly. “I refuse to succumb to a traditional marriage—if I ever succumb at all.”

Dianna moaned. “I can see the future now—you will marry some radical socialist lawyer!”

“Perhaps I will. Can you truly see me as some proper gent’s wife, staying at home, changing gowns throughout the day, a pretty, useless ornament? Except, of course, for the five, six or seven children I will have to bear, like a broodmare!”

“That is a terrible way to look at marriage and family,” Dianna said, appearing stunned. “Is that what you think of me? Am I a pretty, useless ornament? Is my mother, is Aunt Lizzie, is our cousin Margery? And bearing children is a wonderful thing. You like children!”

How had this happened? Ariella wondered. “No, Dianna, I beg your pardon. I do not think of you in such terms. I adore you—you are my sister, and I am so proud of you. None of the women in our family are pretty, useless ornaments.”

“I am not stupid,” Dianna finally said. “I know you are brilliant. Everyone in this family says so. I know you are better read than just about every gentleman of our acquaintance. I know you think me foolish. But it isn’t foolish to want a good marriage and children. To the contrary, it is admirable to want a home, a husband and children.”

Ariella backed off. “Of course it is—because you genuinely want those things.”

“And you don’t. You want to be left alone to read book after book about strange people like the Mongols. It is very foolish to think of spending an entire lifetime consumed with the lives of foreigners and the dead! Unless, of course, you marry a gentleman for his mind! Has it ever occurred to you that one day you might regret such a choice?”

Ariella was surprised. “No, it hasn’t.” She realized her little sister had grown up. She sighed. “I am not ruling out marriage, Dianna. But I am not in a rush, and I cannot ever marry if it will compromise my happiness.” She added, mostly to please her sister, “Perhaps one day I will find that once-in-a-lifetime love our family is so notorious for.”

Dianna grumbled, “Well, if so, I hope you are the single de Warenne who will escape the scandal so often associated with our family.”

Ariella smiled. “Please try to understand. I am very satisfied with my unfashionable status as an aging spinster.”

Dianna stared grimly. “No one is calling you an old spinster yet. Thank God you have a fortune, and the prospects that come with it. I am afraid you will have a great many regrets if you continue on this way.”

Ariella hugged her. “I won’t. I swear it.” She laughed a little. “You feel like the older sister now!”

“I am sending Roselyn to help you dress. We are having an early supper—I cannot recall why. I will lend you my aquamarines. And I know you will be more than pleasant with Montgomery.” Her parting smile was firm, indicating that she had not changed her matrimonial schemes.

Ariella smiled back, her face plastered into a pleasant expression. She intended it to be the look she would wear for the entire evening, just to make Dianna happy.

EMILIAN ST XAVIER sat at his father’s large, gilded desk in the library, unable to focus on the ledgers at hand. It was a rare moment, as his life was the estate. But an odd gnawing had begun earlier that day, a familiar restlessness. He hated such feelings, and was always determined to ignore them. But on days like this one, the house felt larger than ever, and even empty, although he kept a full staff.

He leaned back in his chair, objectively looking around the luxurious, high-ceilinged library. The room bore almost no resemblance to the room in which he had so often been chastised as a sullen boy, when he had been determined to cling to his differences with his father, pretending absolute indifference to Edmund’s wishes and Woodland’s affairs. But even when he had first arrived at the estate, his curiosity had been as strong as his wariness. He had never been inside an Englishman’s home before, and Woodland had seemed palatial. Raiza had insisted he learn to read English, and he had stared at the books in the bookcase behind his father’s head, wondering if he dared steal one so he could read it. Soon he had stolen book after book. In retrospect, he knew Edmund had known he was secretly reading philosophy, poetry and love stories in his bedroom.

Even though his mother had wanted him to leave the kumpa’nia and go to live with his father, he would never forget her tears and her grief. Edmund had broken her heart by taking him away from her, and he had hated Edmund for hurting Raiza. He had known that he would not be at Woodland if Edmund’s firstborn, pure-blooded son had lived. His Rom pride, which was considerable, had demanded that he remain detached and indifferent to the life his father offered him.

His Rom blood had dictated suspicion and hostility. He had lived with gadjo hatred and prejudices his entire life. He knew his father had to be like all the other gadjos. But in truth, Edmund had been firm, but fair and compassionate, too. The adjustment to the English way of life had been so difficult that he couldn’t see it. He’d run away several times, but Edmund had always found him. The last time he’d stolen a neighbor’s horse, and he had been physically branded so that the world would see him as a horse thief before Edmund had appeared to take him home. He was hardly the first Rom to have a scarred right ear, and it was one of the reasons he wore his hair so long. Edmund had finally asked him to stay, telling him he would willingly let him leave when he turned sixteen, if that was what he still wished to do.

He had agreed—and in the end, decided on his own terms to stay. In the following years he had gone to Eton and then Oxford, excelling at both institutions. Yet their relationship had remained somewhat adversarial, as if Edmund never quite trusted his transformation into an Englishman. Emilian never quite trusted his father, either. Being Edmund’s son and heir did not change the fact that his mother was Romany, and all of society knew it—including Edmund.

The condescension and scorn from his youth remained, but it was disguised now. To the gadjos, even those warming his bed, no amount of manners, education or wealth would ever change the “fact” that his inclination was to steal horses and cheat his neighbors. Every supper party and ball, every business affair, every paramour, had proven that—and proved it, still.

Edmund’s death had been a tragic accident. Emilian had just graduated Oxford with the highest honors, and he had been traveling with the Roma. It had been his first visit to his mother, whom he hadn’t seen since his father had taken him from her ten years before. Edmund’s estate manager had written him. Upon learning of Edmund’s sudden death in a hunting accident, Emilian had instantly rushed home.

Shocked that his father had died without his having had the chance to say goodbye, he had gone from his grave directly to his desk. All he could think of was the opportunities of the past—and that he hadn’t ever thanked Edmund for a single one. He recalled his father teaching him how to ride, explaining every aspect of the estate to him, insisting that he receive the best possible education, and how Edmund had proudly taken him to every country affair, whether a tea, a supper party or a country ball, as if he was as English as anyone. He had sat down at his father’s desk and begun poring over every account and ledger until his tears had made it impossible to read the pages. And in the end, a very English sense of duty had triumphed. He had been aware of his father’s failures as the viscount; he had always known he could do far better. Now, he intended to set Woodland straight. Now, he intended to make Edmund proud of him.

And he had. In three years, he had managed to erase all debt from Woodland’s accounts. The estate was currently making a handsome profit. There were new tenants, and their produce was being exported abroad, as well as sold at local markets. He was a partner in a freight company. There were profitable investments in a Birmingham mill and a national railway, but the coup de grâce was the St Xavier coal mine. The export of British coal grew in tonnage annually and he was cashing in on it. He was the wealthiest nobleman in Derbyshire, with one exception—the shipping magnate, Cliff de Warenne.

Emilian pushed the ledgers aside.

He did not know de Warenne personally—how could he? He had scorned society ever since coming into the title and the estate. From his first advent into society as a boy at Edmund’s side, they had whispered about him behind his back, and nothing had changed except that he now expected it. He preferred avoiding all social intercourse, as it was nothing but a dull pretense for everyone involved. When he did sit down to a meal with Englishmen and their wives, it was with men who were important to him—the managers of his mine, his partners in the freight company, those who wished for him to invest in other ventures.

“My lord, sir?” His butler, Hoode, paused on the library’s threshold. “You have callers.” Hoode handed him a small tray containing several cards.

Emilian was surprised. Callers were rare. His last visitor had been a widow with four sons whose family had blatantly informed him she was a good “breeder.” Now, as he took the cards, he fought to avoid cringing. As wealthy as he was, it was inevitable that marriage prospects were pressed upon him from time to time. The candidates were all excessively unmarriageable daughters. The crème de la crème were sent elsewhere to look for blue-blooded English husbands. He didn’t give a damn. He didn’t want children. Childhood was synonymous with misery and fear—and therefore he had no need of a wife, English or not.

He glanced at the cards and became still. These cards were not from families seeking marriage. One card belonged to his cousin, Robert, the others from Robert’s friends.

“This is rich,” he murmured. There was only one reason why his cousin would call, as they could not stand each other. “Send Robert in, Hoode.” He stood, stretching his tall, muscular frame. He intended to enjoy the ensuing encounter, very much the way a basset would enjoy being locked in a small room with a mouse.

Robert St Xavier appeared instantly, smiling obsequiously, hand outstretched. Blond and plump, he boomed, “Emil, my God, it is good to see you, eh?”

Emilian folded his arms across his chest, refusing any handshake. “Shall we cut to the chase, Rob?”

Robert’s smile faltered and he dropped his hand. “We are passing through,” Robert said in a jovial tone, “and I had hoped we could share a good bottle of wine. It has certainly been some time. And we are cousins!” He laughed, perhaps nervously or perhaps at the absurdity that any familial affection lay behind the claim. “We’ve taken rooms at the Buxton Inn. Will you join us?”

“How much do you want?” Emilian said coolly.

Robert’s smile vanished. “This time I vow I will pay you back.”

“Really?” He lifted a brow. Robert had inherited a fortune from his father. He had spent every penny within two years. His life was dissolute and irresponsible, to say the least. “Then it would be a first. How much, Rob, do you need this time?”

Robert hesitated. “Five hundred, perhaps?”

“And that will last for how long? Most gentlemen can live off that sum for a year.”

“It will last a year, Emil, I swear it!”

“Don’t bother swearing to me.” Emilian bent and reached for his checking book. He should let him starve. Too well, he recalled how Robert and his father had scorned him as “that Gypsy boy.” They had called him a dirty savage. But it was only gadjo money—and it was his gadjo money. He ripped the note from its pad and handed it to Robert.

“I can’t thank you enough, Emil.”

He looked at him with disdain. “Have no fear—I will never collect anything from you.”

Robert’s smile, plastered in place, never wavered. “Thank you,” he said again. “And would you mind if we spent the night here? It will save us a few pounds—”

Emilian waved at him dismissively. He didn’t care if the trio stayed, for there was plenty of room at Woodland, enough that their paths would hardly cross. He moved toward the French doors and stared past his gardens at the rolling wooded hills that etched into the gray, fading horizon. He had a terrible sense that something was about to happen…. But it must be his imagination, he thought. Still, he looked at the sky again. Not even a thunderstorm was rolling in.

He turned at the sound of new voices. Two of Robert’s equally disreputable friends had joined him, and Robert was showing them the draft. His friends were laughing and slapping him on the back, as if he had just managed some terrific feat.

“It pays to have a rich cousin, eh? Even if he is half Gypsy.” The man laughed.

“God only knows how he does it.” Robert grinned. “It’s his English blood, of course, that makes him so wealthy.”

The third man leaned close. “Have you ever had a Gypsy wench?” He leered. “They’re at Rose Hill—I heard it from a houseman.”

Emilian stiffened in surprise. There were Roma nearby. Had he sensed them all this time?

And suddenly a young Rom, no more than fifteen or sixteen years old, stepped onto his flagstone terrace, staring at him through the French doors.

Emilian moved forward. “Wait!”

The young Rom whirled and started to run.

Emilian ran after him. “Don’t go!” he cried. Then, in Roma, “Na za!”

The boy froze at the sharp command. Emilian hurried forward. Continuing to speak in the Romany language, he said, “I am Rom. I am Emilian St Xavier, son of Raiza Kadraiche.”

The boy appeared relieved. “Emilian, Stevan sent me. He must speak with you. We are not far—an hour by horse or wagon.”

Emilian was stunned. Stevan Kadraiche was his uncle, whom he had not seen in eight years. Raiza traveled with him, as did his half sister, Jaelle. But they never traveled farther south than the Borders. He could not imagine what this meant.

And then he knew. There was news—and it could not be good.

“Will you come?” the boy asked.

“I’ll come,” he said, lapsing into English. He steeled himself, but for what he did not know.

CHAPTER TWO

ARIELLA STOOD BY the fireplace, wishing she could leave the supper party and return to her room. She would much prefer curling up with her book for the evening. Pleasant greetings had been exchanged and the weather had been discussed, as had Amanda’s famous rose gardens. Dianna, who was very pretty in her evening gown, was now mentioning her mother’s upcoming ball, the first at Rose Hill in years. “I do hope you will attend, my lords,” she said sweetly.

Ariella fixed a smile on her face and glanced at her father. Tall and handsome, in his midforties, he was still a man who caught the ladies’ eyes. But he did not notice; he remained smitten with his wife, who was as passionate as her husband about the sea, and eccentric enough to stand on the quarterdeck with him even now. Yet Amanda also loved balls and dancing, which made no sense as far as Ariella was concerned. After supper, she decided she would approach her father and see if he might allow a very bold adventure into the heart of central Asia.

Lord Montgomery turned to her. “You do not seem to anticipate the Rose Hill ball.” He spoke quietly, seriously.

She could not help herself. “I do not care for balls. I avoid them whenever I can.”

Dianna rushed to her side. “Oh, that is so untrue,” she scolded.

“I prefer travel,” she added. She saw her father smile.

“I enjoy travel, too. Where have you been recently?”

“My last voyage was to Athens and Constantinople. I now wish to visit the steppes of central Asia.”

Dianna paled.

Ariella sighed. She had promised her sister to avoid any discussion of the Mongols. She debated several topics and gave in to one that interested her. “What do you think about Owen’s great experiments to help labor improve its position and place in the economy?”

Montgomery blinked. Then his gaze narrowed, as if with interest.

But the younger Montgomery stared at her in shock. Then he turned to her father and said, “An absolute disaster, of course, to consolidate labor like that. But what do you expect from a man like Robert Owens? He’s a merchant’s son.”

Ariella bristled and said to his back. “He is brilliant!”

Cliff de Warenne came to stand beside her, putting his hand on her shoulder. He said pleasantly, “I have been impressed with Owen’s experiments. I support the theory of consolidated labor interests.”

The younger Montgomery had to face Ariella with Cliff now. “Good God, and what will be next? The Ten Hours Bill? Labor will certainly argue for that!” He gave Ariella a dark look that she had received many times. It said, Ladies’opinions are not welcome.

Ariella planted her hands on her hip, but she smiled sweetly. “It was a social and political travesty to allow the Ten Hours Bill to be trampled under industrial and trade interests. It is immoral! No woman or child should have to work more than ten hours a day!”

Paul Montgomery raised both pale brows, then turned aside dismissively. “As I was saying,” he said to Cliff, “the business interests in this country will go under if unions are encouraged and allowed. No one will be foolish enough to so limit the hours of labor or to support consolidated labor.”

“I disagree. It is only a matter of time before a more humane labor law is enacted,” Cliff said calmly.

“This country will go under,” the younger Montgomery warned, flushing. “We cannot afford higher wages and better work conditions!”

Amanda smiled and said, “On that note, perhaps we should all go in to dine? We can continue the fervent debate over supper.”

A debate over supper, Ariella thought with excitement. She would hardly mind!

But then she caught her sister’s eye. Dianna looked at her with an obvious plea. Why are you doing this? She mouthed, You promised.

“I am too much of a gentleman to debate a lady,” the young Montgomery said stiffly, but he looked terribly put out.

His older brother chuckled, and so did Cliff. “Let’s go in, as my wife has suggested.”

Suddenly a terrific round of shouting could be heard, coming from the front hall of the house, as if a mob had invaded Rose Hill.

“What is that?” Cliff exclaimed, already leaving the salon. “Wait here,” he ordered them all.

Ariella didn’t even think about it—she followed him.

The front door was open. Rose Hill’s butler was flushed, facing a good dozen men who seemed to wish to throng inside. When Cliff was seen, shouts began. “Captain de Warenne! Sir, we must have a word!”

“What is going on, Peterson?” Cliff demanded of the butler. “For God’s sake, it’s the mayor! Let him in.”

Peterson rushed to open the door and the four foremost gentlemen rushed in. “Sir, Mayor Oswald, Mr. Hawks, Mr. Leeds, and your tenant, Squire Jones. We must speak with you. I am afraid there are Gypsies on the road.”

Ariella started. Gypsies? She hadn’t seen a Gypsy caravan since she was a small girl. Maybe her time at Rose Hill would not be so uneventful after all. She knew nothing about the Gypsy people except for folklore. She vaguely recalled hearing their exotic music as a child and being intrigued by it.

“Not on the road, Captain. They are making camp on Rose Hill land—just down the hill from your house,” the rotund mayor cried.

Everyone began to speak at once. Cliff held up both hands. “One at a time. Mayor Oswald, you have my undivided attention.”

Oswald nodded, jowls shaking. “Must be fifty of them! They appeared this morning. We were hoping they wouldn’t stop, but they have done just that, sir. And they are on your land.”

“If one of my cows is stolen, just one, I’ll hang the Gypsy thief myself,” Squire Jones shouted.

The others started talking at once. Ariella flinched, as they began describing children vanishing, horses being stolen and traded back to the owners so disguised as to be recognizable, and dogs running wild. “No trinket in your home— or mine—will be safe,” a man from outside the house cried.

“The young women were begging in the streets this afternoon!” a man said. “It is a disgrace.”

“My sons are sixteen and eighteen,” someone said as fiercely. “I won’t have him being tempted by Gypsy trollops! They already had one girl read their hands!”

Ariella looked at her father, stunned by such bigotry and fear. But before she could tell the throng that their accusations were immensely unfair, Cliff held up both hands.

“I will take care of this,” he said firmly. “But let me first say that no one will be murdered in their sleep, and no family will suffer the theft of children, horses, cows or sheep. I have encountered Gypsies from time to time, over the years. The reports of such crime and theft are grossly exaggerated.”

Ariella almost relaxed. She knew nothing about Gypsies, but surely her father was right.

“Captain, sir. The best thing is to send them on, out of the parish. We don’t need them here. They’re Scot Gypsies, sir, from the Borders, up north.”

Cliff called for silence again. “I will speak to their chief and make certain they mind their business and continue on their way. I doubt that they intend to linger. They never do. There is nothing to worry about.” He turned and looked at Ariella, an invitation in his eyes.

She grinned. “Of course I am coming with you!”

“Do not tell your sister,” he warned as they stepped past the crowd and out of the house.

Ariella fell into step with him, happy to have left the supper party behind. “Dianna has grown up. She is so proper.”

Cliff chuckled. “She did not get that from me—or her mother,” he said. Then he gave her a closer look as they strode down the driveway. “She adores you, Ariella. She has been chatting incessantly about your visit to Rose Hill. Try to be patient with her. I realize no two sisters could be more different.”

Ariella felt terrible then. “I suppose I am a neglectful sister.”

“I understand the lure of your passions,” he said. “At your age, better the lure of passion than no lure at all.”

Her father so understood her nature. Then her smile faded. The shell drive curved away from the house before sloping down to the public road. Below her, she saw an amazing sight. The sun was setting. Perhaps two dozen wagons, painted in bold jewel tones, sparkled in the fading daylight. Their horses were wandering about, children running and playing, and the Gypsies added to the kaleidoscope of color, colorfully dressed in hues of scarlet, gold and purple. The mayor had been right. There were at least two dozen wagons present, and the Gypsies may well have numbered closer to sixty or seventy.

“Did you mean what you said about the Gypsies?” she asked in an awed whisper as they paused. She felt as if she had been swept away into a foreign land. She heard their strange, guttural language and she smelled exotic scents, perhaps from incense. Someone was playing a lively, almost occidental melody on a guitar. But there was nothing foreign or strange about the children’s happy laughter and the women’s chatter.

Cliff’s smile was gone. “I have met many Romany tribes over the years, mostly in Spain and Hungary. Many are honest, Ariella, but unfortunately, they are not open to outsiders. They distrust us with good cause, and it is rather common for them all to take great pride in swindling the gadjo.”

She was intrigued. “The gadjo?”

“We are gadjos—non-Gypsies.”

“But you told the mayor and his cronies not to worry.”

“Is there ever a reason to worry about the worst case? We do not know that they will linger, nor do we know that they will steal. On the other hand, the last time I encountered the Romany people, it was in Ireland. They stole my prized stud—and I never saw the animal again.”

Ariella looked at Cliff carefully. He was reasonable now, but she saw the quiet resolve in his eyes. If any incident occurred, he would not hesitate to take action. “Are you certain a Gypsy stole the stallion?”

“It is the conclusion I drew. But if you are asking if I am one hundred percent positive, the answer is no.” He laid his hand on her shoulder with a brief smile and they started forward.

They had reached the outermost line of wagons, which encircled a large clearing where several pits were being dug for fires. Ariella’s smile faded. The children ran about barefoot with barking dogs, and their pets were thin and scrawny. Women were hauling buckets of water from the creek. The pails were clearly very heavy, but the men were busy pounding stakes and laying out the canvas for tents, hurrying to get the camp made before dark. She looked more closely at the women. Their faces were tanned, lined and weather-beaten. Their colorful skirts were carefully patched and mended. They wore their long, dark hair loose or in braids. The woman closest to them had an infant in a pouch on her back. She removed items from a wagon.

This was a hard life, Ariella thought, and now, she realized that all the laughter and conversation had ceased. Even the guitar player had stopped strumming.

The women paused and straightened to stare. Men turned, also staring. The children ran to the wagons and hid there, peeking out. An absolute silence fell, broken only by a yapping dog.

Ariella shivered, uneasy. These people did not seem pleased to see them.

A huge bear of a man, his hair dark and unkempt, stepped out from the center of the camp in front of the wagons, as if to bar their way. His red shirt was embroidered, and he wore a black-and-gold vest over it. Four younger men, as dark and as tall, came to stand with him. Their eyes were hostile and wary.

Hoofbeats sounded. Ariella turned as a rider on a fine gray stallion galloped up to the outermost wagons, another rider trailing farther behind. He leaped off the mount, striding toward the Gypsy men.

She felt the evening become still. He wore a plain white lawn shirt, fine doeskins breeches, and Hessians that were muddy. He did not wear a coat of any kind and his shirt was unbuttoned, almost to the navel. Clad as he was, he may as well have been naked. No Englishman would travel publicly in such a way. He was tall, broad-shouldered, powerfully built. He wasn’t as dark as the other Gypsies, and his hair was brown, not black, glinting with red and gold in the setting sun. She couldn’t see him more clearly from this distance, but oddly, her heart began to wildly race.

Cliff took her elbow and started forward. Ariella now heard the newcomer speaking to the Gypsies in their strange, Slavic-sounding tongue. His tone was one of command. Instantly Ariella knew he was their leader.

And then the Gypsy leader looked at them.

Cold gray eyes met hers and her breath caught. He wasso beautiful. His piercing eyes were impossibly long lashed, and set over strikingly high, exotic cheekbones. His nose was straight, his jaw hard and strong. She had never seen such masculine perfection in her entire life.

Her father stepped forward. “I am Cliff de Warenne. Who is vaida here?”

There was a moment of silence, filled with hostility and tension. It gave her the opportunity to really look at the Gypsy chief. Of course he wasn’t English. He was too dark, too immodestly dressed and his hair was far too long, brushing his shoulders. Tendrils were caught inside his open collar, as if sticking to his wet skin.

She flushed but couldn’t stop staring. Her gaze drifted to a full but tense mouth. She glimpsed a gold cross he wore, against the dark, bronzed skin of his chest. Her color increased just as her heart sped more fully. She knew she should look away, but she simply couldn’t manage to do so. In the fine silk shirt, she could even see his chest rising and falling, slow and rhythmic. Her glance went lower. The doeskin breeches clung to his thick, muscular thighs and narrow hips, delineating far too much male anatomy.

She felt his eyes on her; she looked up and met his gaze a second time.

Ariella flamed. Knowing she had been caught, she looked quickly away. What was wrong with her?

“I am Emilian. You will speak to me,” he said, a slight accent hanging on his every word.

“I see you are already making camp. You are on my land,” Cliff said, his tone hard.

Ariella looked up, but the gray-eyed Gypsy was intent on her father now. She didn’t know why she was so flustered. She had never been as aware of anyone. Maybe it was because he was an enigma. He was dressed like an Englishman might in his boudoir—but he was not in the privacy of his home. His English seemed flawless, but he spoke the Gypsy tongue.

Emilian smiled unpleasantly. “Long ago,” he said softly, “God gave the Rom the right to wander freely and to sleep where they wish.”

Ariella flinched. She knew a gauntlet when it was thrown, and she also knew that while her father wished to discuss the situation, he had a dangerous side. There was a hint of ruthless savagery in Emilian’s cold gray eyes.

Cliff’s smile was equally unpleasant. “I am sure you think so. But recently, the government of England passed laws limiting the places vagabonds and Gypsies can stay.”

Emilian’s gray eyes flickered. “Ah, yes, the laws of your people—the laws that allow a man to hang simply because he travels in a wagon.”

“This is the nineteenth century. We do not hang travelers.”

A cold smile began. “But to be a Gypsy is to be a felon, and for such an unlawful life, the punishment is death. Those are your laws.”

“I doubt you understand the law correctly. We do not hang men because they are Gypsies. None of that changes the fact that you are on my private land.”

Emilian said softly, “Do not patronize me, de Warenne. I know the law. As for this camp, there are women and children here who are too tired to go on tonight. I am afraid we will stay.”

Ariella tensed. Why did their leader have to be so belligerent? She knew her father had not intended to send them away, not that night. But she now saw Cliff’s eyes flicker with real annoyance, and she sensed an impending battle.

“I did not ask you to leave,” Cliff said flatly. “But you must give me your word that there will be no mischief tonight.”

The gray-eyed Gypsy stared. “We will try not to steal the lady’s necklace while she sleeps,” he said scornfully.

Her father tensed, his blue eyes flaring with anger. “The lady is my daughter, vaida, and you will refer to her with respect or not at all.”

Ariella quickly stepped forward, uncertain if the men might not come to blows. The air was drenched with their male fury. She smiled at the Gypsy leader; his gaze narrowed. “We are more than pleased to accommodate you, sir, for the night. There is plenty of room to spare, as you can see. My father is only concerned because the townspeople are in a tizzy. That, of course, is due to their ignorance.” She spoke in a rush and was terribly aware of her nervousness.

He stared at her. Her smile wavered and vanished.

Cliff flushed. “Ariella, go back to the house.”

She started. Her father hadn’t ordered her about in years. How had a simple reconnaissance mission turn into such hostility? She stepped closer to Cliff and lowered her voice. “You will let the Gypsies stay the night, won’t you?” It had become terribly important to her. “I am sure their leader doesn’t mean to be so abrasive. Father, you know that their ways are different from ours. He probably doesn’t realize how impolitic he is being. Please give him the benefit of the doubt.”

Cliff’s expression eased ever so slightly. “You are too kind for your own good. You may be assured he intends to be rude. But I will give him the benefit of the doubt.”

Relieved, she glanced at the Gypsy, about to smile at him, but his expression was so intense and so speculative that her intention vanished. It made him seem savage and even predatory— as if he was thinking about her in very inappropriate ways. Ariella swallowed. It was impossible to look away.

“We are Rom,” Emilian said to her and her alone. “And I do not need you defending me and mine.”

He had overheard her. In that moment, she forgot that her father stood beside her and that four Gypsies crowded behind Emilian. Suddenly it was as if they were alone. She became acutely aware of his pull, as if a charge of some kind sizzled and throbbed between them. Her heart beat thickly and swiftly, almost hurtfully, in her chest; she thought she heard his heavy, thudding heartbeat, as well, although they stood at least three yards apart. “I’m sorry,” she whispered hoarsely. “Yes, you are Romany, I know that.”

His lashes lowered slowly. She was certain he looked at her still, but it was almost impossible to tell. A frisson went through her, giving her the oddest feeling in her stomach. Her body ached with a new, terrible tension.

Cliff stepped forward. “Go back to the house, Ariella.” He was sharp.

He was angry, and she knew it was because the Gypsy had looked at her so boldly. She said, “Why don’t we both go back? It is late, and Amanda is delaying supper for us,” she tried.

Cliff stared coldly at the Gypsy, ignoring her. “I have been kind enough to allow you a night’s respite here. You may keep your eyes where they belong—on your own women.”

The Gypsy shrugged. “Yes, you are so very kind,” he mocked. “Do not expect gratitude from me.”

Why did he have to seek a battle? Did he have to be so hostile?

“I expect you to be gone in the morning,” Cliff said, his face set. “Let’s go.”

She didn’t want to leave, but there was no reason to stay. As Cliff turned away, she looked back helplessly. He stared at her, his silver gaze smoldering. No man had ever looked at her in such a way before. A terrible awareness of what it meant began.

That man was different. She wanted to pull free of her father and go back to him.

He almost smiled, as if he knew the effect he had on her.

Her father pulled on her arm and she turned to keep up with Cliff. As she did, a woman cried out loudly in pain.

Ariella turned back, alarmed. Their gazes locked again. She whispered, “What is that? Is someone hurt?”

He grasped her arm and murmured, “She does not need you, gadji.”

Ariella forgot to breathe. His hand was large, strong and burning hot. His breath feathered her cheek, and his knee bumped her thigh. Then he released her.

It had happened so quickly that Ariella was stunned. Emilian said harshly, “We take care of our own.” He looked at Cliff, his face hard and set. “Take your princess daughter away. Tell her we do not like gadjos. We will leave in the morning.”

Ariella trembled. “I can send for a doctor,” she tried, but her father cut her off.

“My daughter is just that to you, Rom—a princess. Never lay a hand on her again,” Cliff exploded.

“Father, stop!” Ariella cried, shaken and breathless, still feeling the Rom’s touch. “He didn’t want me intruding—that is all! The mistake was mine.”

But Cliff ignored her, too upset to hear. “Make sure nothing and no one vanishes in the middle of the night. If one horse is stolen, one cow or a single sheep, I am holding you responsible, vaida.”

Emilian smiled tightly and did not speak.

Ariella could not believe her father would make such a threat. As she stumbled to keep up with Cliff, she looked back.

As still as a statue, the vaida was staring after her. Even from the distance separating them, she felt so much strength and disdain—and an intention she did not understand. He swept her a bow, as elegant as any courtier’s, but his eyes were blazing, ruining the effect. Ariella inhaled and turned away.

What kind of man was that?

EMILIAN STARED after the gadjo and his beautiful daughter. His insides burned with dislike for de Warenne. The daughter’s defense of his disrespectful behavior echoed in his mind. His body rippled with anger and tension. He didn’t need her or any gadjo to defend him. She thought to be kind? He didn’t care that she was kind.

His loins were full. To a man like him, she was so far above him she was a princess—the kind of beautiful, perfect, blue-blooded woman that no English matron would ever present to him. But in spite of the differences of class and blood between them, she had looked at him the way all the Englishwomen who wished to use him did—as if she couldn’t wait to tear off his clothes and put her hands and mouth all over him.

He almost laughed, mirthlessly. He exchanged gadji lovers with almost the same frequency that he did his clothes. Those wives and widows used him strictly for carnal passion, and he used them for far more. There was a satisfaction to be had in sleeping with his neighbor’s wife, when his neighbor looked down on him with so much condescension and scorn. He may have been raised English, but he was still didikoi—half blood—and budjo was ingrained in his soul. A man who mowed his neighbor’s hay and sold it back to his neighbor was considered great. To take what belonged to someone else and reap a profit from it before returning it to its owner, perhaps for even more profit, was a great swindle. Every Rom was born with the need for budjo in his or her blood. Budjo was a Rom’s last laugh—and it was his revenge for the injustice every Rom had ever faced in the world.

He could have de Warenne’s daughter, if he wanted to bother. More blood filled him, hot and thick. She would be wet clay in his hands. He was well aware of his powers of persuasion. But he had little doubt that Cliff de Warenne would murder him if he ever found out.

The temptation was vast, because she was so beautiful. He knew she’d whisper about him behind his back after leaving his bed, like they all did. His paramours couldn’t wait to discuss the sexual prowess of their Gypsy lover with their friends—as if he was a stud for hire. She was unmarried, but the way she’d looked at him told him she was experienced. It would be interesting, he decided, to take that one to bed.

Something niggled at him, bothering him—a sixth sense, warning him, but of what he could not decide.

“Emilian.”

He whirled, relieved at the distraction. Then the relief vanished as he stared at his uncle’s sober face. “The woman?”

Stevan made a sound. “The woman is my wife, and she is having your cousin.”

A warmth began, unfurling within his chest. Stevan had several children, whom he had met eight years ago, but he didn’t even know precisely how many cousins he had, nor could he recall their names. And another was on the way.

Suddenly he was overwhelmed. He felt moisture gather in his eyes. The warmth felt like joy. It had been so long since he had been with family. Robert did not count; Robert despised and scorned him. Stevan, his children, Raiza, Jaelle—they were his family. And although he was didikoi, these people accepted him in spite of his tainted blood, unlike the English, who had never really accepted him at all. Even Edmund had had his doubts. In that moment, he did not feel isolated or alone. He did not feel different. He was not an outsider.

Stevan clasped his shoulder. “You are a grown man now. Djordi tells me your home is rich.”

“I have made it rich,” Emilian said truthfully. He wiped his eyes. He could not remember Stevan’s wife’s name and that was truly shameful.

Stevan smiled. “A lot of budjo, eh?”

Emilian hesitated. He had made Woodland profitable through English work, not Gypsy budjo. He did not want to tell his uncle he had labored honestly and industriously, instead of using cunning for his gain. “A lot of budjo,” he lied.

Stevan nodded, but his smile faltered.

Emilian tensed. Knives seemed to have pierced his guts. He asked slowly, “Why have you come to find me?”

Stevan hesitated, but as he did so, a young Romni ran out from the wagons, her bright red skirts swirling. She paused, barefoot, not far from them. “Emilian,” she whispered, flushing.

It took him a moment to see Raiza’s beauty in her young, striking features. He gasped, realizing he was staring at his little half sister, except she wasn’t twelve years old anymore —she was twenty.

She smiled beatifically and rushed into his arms.

He felt himself smile widely, the kind of smile he hadn’t felt in years, one that began in his heart. He held her, hard, just for a moment, relishing the rare embrace—it was entirely different from holding a lover he did not care for. When he released her, he was still smiling. “Jaelle! You are a beautiful woman now. I am in shock!”

“Did you think I’d grow up ugly?” She laughed, tossing her dark mane of hair. He now realized it was tinged with deep red tones and her eyes were golden amber.

“Never!” he exclaimed. “Are you married?” He was almost afraid of her response.

She shook her head. “There is no one here that I want.”

He wasn’t sure if that answer pleased him or not.

Stevan said gruffly, “There have been good men who have asked for her. She has refused them all.”

“I will know when I wish to marry, and I haven’t wished to yet.” She touched his face. “Look at you—a gadjo now! With so much wealth—Djordi said so. But can pounds replace the wide road and the shining stars?”

His smile faded. Although he had tried to run away many times when he had first been brought to Woodland, he had finally chosen to stay. And he hadn’t thought twice about taking over the estate upon Edmund’s death. What could he say? Just then, surrounded by true family, he was uncertain his choices had been the right ones. “I am half blood,” he said, hoping to sound light. “Woodland is a good place, but I miss the open road and the night sky.” And in that moment it was achingly true. He missed Jaelle, Raiza and his uncle. He hadn’t realized it until then.

Jaelle tugged on his hand. “Then come with us, just for a while.”

He hesitated. There was so much temptation.

Stevan seemed doubtful. “Jaelle, you have heard it before— half blood, half heart. I don’t think our way will please your brother for long.” Stevan looked at him. “He has been raised a gadjo. Our life is better—but he cannot know that.”

His uncle’s words filled him with tension. The lure of the open road was suddenly immense. But he had duties, responsibilities. He saw himself hunched over his desk, attending to papers until well into the next morning, or standing in a great hall, apart from the ladies and gentlemen present, there only to discuss a business affair. He recalled the previous evening, when he had been in bed with a neighbor’s wife, giving them both rapture. How easily he could sum up his life—it consisted of Woodland’s affairs and his sexual encounters and nothing more.

“Maybe your life is the better way,” Emilian said slowly. That did not mean he could leave, however.

Jaelle seemed ready to hop up and down. But she teased, “Your accent is so strange! You don’t sound Romany, Emilian!”

He flushed. He hadn’t spoken the tongue in eight years.

Stevan took his arm. “Do you wish to speak with your sister now?”

Emilian glanced at Jaelle, who was bubbling with enthusiasm and happiness. He did not want to disappoint her. He hoped her good nature was always with her. It crossed his mind that he wished to show her Woodland at some point in time, before the kumpa’nia went north again. There was so much he could offer her now—except she preferred the Roma way.

He could see her in his gadjo home, in a gadji’s dress, and he stiffened because that was completely wrong. He faced Stevan. “Jaelle and I have all night—and many nights to talk to one another.” He sent her a smile. “Maybe I can find you your husband, jel’enedra.”

She made a face. “Thank you, but no. I will hunt on my own—and choose on my own.”

“So independent!” he teased. “And is it a manhunt?”

She gave him a look that was far too arch; she was no naive, virginal, pampered English rose. “When he comes, I will hunt him.” She stood on tiptoe to kiss his cheek and darted off.

Emilian stared after her.

“Do not worry,” Stevan said. “She is far more innocent than she appears. She is playing the woman, that is all. I sometimes think of her as being fifteen.”

“She isn’t fifteen,” he said tersely. Romany mores and ethics were entirely different from gadjo ones. It would be unusual if Jaelle was entirely innocent when it came to passion. “She should be married,” he said abruptly. He did not wish for her to be used and tossed aside like their mother.

Stevan laughed. “Spoken like a true brother—a full-blood brother!”

Emilian didn’t smile. He waited.

Stevan’s smile faded. “Walk with me.”

He did, with a terrible sense of dread. The night had settled with a thousand stars over them. The trees sighed as they walked by. “She’s not here.”

“No, she is not.”

“Is she dead?”

Stevan paused, placing both of his hands on his shoulders. “Raiza is dead. I am sorry.”

He wasn’t a boy of twelve and he had no right to tears, but they filled his eyes. His mother was dead. Raiza was dead—and he hadn’t been there with her. She was dead— and he’d last seen her eight long years ago. “Damn it,” he cursed. “What happened?”

“What always happens, in the end, to the Romany?” Stevan asked simply.

“She was telling fortunes at a fair in Edinburgh. A lady was very displeased with her fortune, and when she came back, she did so with her nobleman. She accused Raiza of deceit and demanded the shilling back. Raiza refused. A crowd had gathered, and soon everyone was shouting at Raiza, accusing her of cheating, of begging, of stealing their coin. By the time I learned of this and had gone to her stall, the mob was stoning her. Raiza was hiding behind her table, using it like a shield, otherwise, she would have died then.”

His world went still. He saw his mother, cowering behind a flimsy wood table, the kind used to play cards.

“I ran through the crowd and they began to stone me. I grabbed Raiza—she was hurt, Emilian, and bleeding from her head. I tried to protect her with my body and we started to run away. She tripped so hard I lost hold of her. I almost caught her—instead, she fell. She hit her head. She never woke up.”

He wanted to nod, but he couldn’t move. He saw her lying on a cobbled street, her eyes wide and sightless, her head bleeding.

Stevan embraced him. “She was a good woman and she loved you greatly. She was so proud of you! It was unjust, but God gave us cunning to make up for the gadjo ways. One day, the gadjo will pay. They always pay. We always make them pay. Fools.” He spit suddenly. “I am glad you used budjo to cheat the gadjos and make yourself rich!” He spit again, for emphasis.

Emilian realized he was crying. He hadn’t cried since that long-ago night when he’d first been torn from his Romany life. He’d been locked up by the Englishman who was sworn to take him south to his gadjo father. He’d been in chains like men he’d seen on their way to the gallows—some of them Rom. He’d cried in fear. He’d cried in loneliness. Ashamed, he’d managed to stop the tears before the ugly Englishman had returned. Now, his tears came from his broken heart. The grief felt as if it would rip him apart.

He hadn’t been there to protect her, save her. He wiped his eyes. “When?”

“A month ago.”

The grief made it impossible to breathe. She was gone. Guilt began.

A month ago he had been immersed in his gadjo affairs. A month ago he had been redesigning his gadjo gazebo. A month ago, he had been fucking his gadjo mistress night and day.

Because he had chosen to stay with Edmund, when he could have left him.

He had chosen his father over his mother—and now Raiza was dead.

“They always pay,” Stevan said savagely.

He wanted the murderers to pay. He hated them all. Every single last one of them. More tears streamed. But there was no single murderer to hunt. Why hadn’t he been there to save her? The guilt sickened him, the rage inflamed him. Damn the gadjos, he thought savagely. Damn them all.

And he thought of de Warenne and his daughter.

CHAPTER THREE

HE WANDERED along the perimeter of the encampment, head down, allowing the rage to build. He preferred the anger to the grief. Raiza’s fear must have known no bounds. But the rage did not erase the guilt. His mother had been murdered by gadjos while he lived like one, and he would never forgive himself for having visited her just once in the past eighteen years.

“Emilian.”

At the sound of Jaelle’s voice, he halted, realizing how selfish his grief was. Stevan cared for his sister, but that was no substitute for her mother. Jaelle’s father was a Scot who hadn’t cared about his bastard Gypsy daughter, for he had a Scottish wife and a Scottish family. “Come here, edra,” he said, forcing a smile.

Her expression was uncertain as she approached. She touched his arm. “I am sad, too. I am sad every day. But it is done.” She shrugged. “One day, I will make the gadjos pay.”

He stiffened. “You will do no such thing. You may leave vengeance to me. It is my right.”

“It is my right, as well, even more!” She flared. “You hardly knew Raiza!”

“She was my mother. I did not ask to be taken from her.”

She softened. “I am sorry, Emilian. Of course you didn’t.” She hesitated, her amber gaze searching. “When I was small, you came to us. Do you remember? It was a happy time.”

“I remember,” he said, aware of what she wished him to recall.

But she simply stared and he knew she was thinking about how he had come for a month—and abruptly left.

“What is it that you wish to know?”

“You are as rich as a king. You have no master. Why? Why haven’t you come to us since that time? Why haven’t you come to me? Do you prefer the gadjo to the Romany people? Do you prefer the gadjo life to our own? You came when I was a small child. But you did not stay!”

She was intense, and tears shimmered in her eyes. He understood how important this was to her—he understood that he had this small woman’s loyalty and love. He took her hand. It was awkward to do so, but he did not release her palm. A few days ago, his answer would have been different, he realized. But their mother’s death hovered over them, a dark, terrible shroud. The grief remained, bursting in his heart, overshadowed by guilt. The anger threatened to explode. “I left because I received word of my father’s death,” he said truthfully. “But I didn’t join the kumpa’nia intending to stay. I had dreamed of traveling with the Rom, and I was young, so I came. It was an adventure, jel’enedra.”