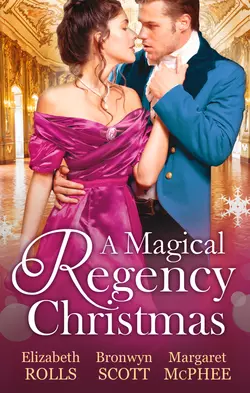

A Magical Regency Christmas: Christmas Cinderella / Finding Forever at Christmas / The Captain′s Christmas Angel

Margaret McPhee и Elizabeth Rolls

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Three Sparkling Festive Regency TalesCHRISTMAS CINDERELLAHandsome country rector Alex Martindale dreams of kissing the spirited schoolmistress and never having to stop… With the aid of some Christmas mistletoe, he may just get his wish!FINDING FOREVER AT CHRISTMASAt the yule ball, Catherine Emerson receives a proposal from the man she thinks she wants – but an interlude with his mysterious, darkly handsome brother unleashes a deeper desire…THE CAPTAIN′S CHRISTMAS ANGELReturning to England for Christmas, Sarah Ellison discovers gorgeous Captain Daniel Alexander adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. But nothing could have prepared her for the secrets he’s keeping!