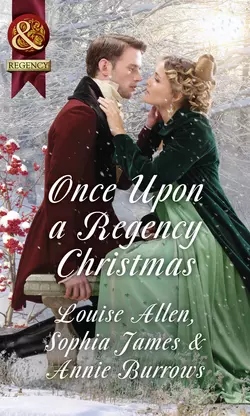

Once Upon A Regency Christmas: On a Winter′s Eve / Marriage Made at Christmas / Cinderella′s Perfect Christmas

Louise Allen

ANNIE BURROWS

Sophia James

THREE REGENCY HEROES IN DISGUISE.THREE CHRISTMAS NOVELLAS TO WARM YOUR HEART!ON A WINTER’S EVE by Louise AllenSnowbound together, Lady Julia Chalcott and Captain Giles Markham try to fight temptation. But as Christmas draws closer their attraction proves too strong to resist!MARRIAGE MADE AT CHRISTMAS by Sophia JamesChristine Howard's frozen heart melts as she gets to know her new bodyguard. How can a man so scarred and mysterious make her feel so safe…?CINDERELLA’S PERFECT CHRISTMAS by Annie BurrowsShy Alice Waverly’s kiss with Captain Jack Grayling makes her wonder if he—and his little children—could be the Christmas miracle she’s always dreamed of…

Praise for the authors ofOnce Upon a Regency Christmas (#ulink_4ecc9df1-70d2-5b51-806b-461ca3d436c1)

LOUISE ALLEN

‘Allen deftly pulls fans into the glittering, dangerous world of England’s elite.’

—RT Book Reviews on His Christmas Countess

‘Allen has written another spellbinding and adventurous Regency romance.’

—RT Book Reviews on Beguiled by Her Betrayer

SOPHIA JAMES

‘Readers will be thrilled with this triumphant tale.’

—RT Book Reviews on Marriage Made in Hope

‘Delightful and seductive…’

—RT Book Reviews on Marriage Made in Shame

ANNIE BURROWS

‘Burrows is a master at Regency romance.’

—RT Book Reviews on In Bed with the Duke

‘The poignancy and humour will make any reader a Burrows fan.’

—RT Book Reviews on The Captain’s Christmas Bride

LOUISE ALLEN loves immersing herself in history. She finds landscapes and places evoke the past powerfully. Venice, Burgundy and the Greek islands are favourite destinations. Louise lives on the Norfolk coast and spends her spare time gardening, researching family history or travelling in search of inspiration. Visit her at louiseallenregency.co.uk (http://www.louiseallenregency.co.uk), @LouiseRegency and janeaustenslondon.com (http://www.janeaustenslondon.com).

SOPHIA JAMES lives in Chelsea Bay, on Auckland’s North Shore, in New Zealand, with her husband who is an artist. She has a degree in English and History from Auckland University and believes her love of writing was formed by reading Georgette Heyer in the holidays at her grandmother’s house. Sophia enjoys getting feedback at sophiajames.co (http://www.sophiajames.co).

ANNIE BURROWS has been writing Regency romances for Mills & Boon since 2007. Her books have charmed readers worldwide, having been translated into nineteen different languages, and some have gone on to win the coveted Reviewers’ Choice award from Cataromance. For more information, or to contact the author, please visit annie-burrows.co.uk (http://www.annie-burrows.co.uk), or you can find her on Facebook at Facebook.com/AnnieBurrowsUK (http://www.Facebook.com/AnnieBurrowsUK).

Once Upon a Regency Christmas

On a Winter’s Eve

Louise Allen

Marriage Made at Christmas

Sophia James

Cinderella’s Perfect Christmas

Annie Burrows

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

CONTENTS

Cover (#u22b4db80-6b54-5120-8d74-a22a24a422ea)

Praise (#ulink_9e0ad439-c62b-57c2-beeb-5d81ee11a185)

About the Author (#ue22b9c31-f3ca-5723-b3a8-2cfb8163e444)

Title (#uc7b03aba-d6a7-5a34-8c26-4a47d4ec4938)

ON A WINTER’S EVE

Dear Reader (#ulink_9e31cb7a-6b2b-5bfb-93c9-d8d22de2ff57)

Dedication (#u252658d9-38b1-56e8-8ebe-ccbaa340f6b0)

Chapter One (#ulink_61202a31-5762-5f8c-9622-0bdab02481fa)

Chapter Two (#ulink_6bc1a40c-1340-5e11-bb53-9d3386798b8e)

Chapter Three (#ulink_cb401542-6c5e-56f0-90d6-92ab2efe38e1)

Chapter Four (#ulink_dd9ca338-1a84-57b6-8cb9-65bc07096472)

Chapter Five (#ulink_3300fd35-d379-529d-92db-b07c8a525676)

Chapter Six (#ulink_413ccc46-3658-50de-9763-e1ca6198acd6)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

MARRIAGE MADE AT CHRISTMAS

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

CINDERELLA’S PERFECT CHRISTMAS

Chapter One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ON A WINTER’S EVE (#ulink_3a39560e-ab37-59aa-bb5b-36f9c439c468)

Dear Reader (#ulink_9df812c8-cc0e-52fb-adfc-52193a1f6000)

The idea for this story began with a Regency cartoon showing a frantic Norfolk turkey escaping from its Christmas doom in Leadenhall Market. I wondered what became of it, and found the answer when my hero rescued the ungrateful bird from a snowdrift. From there the story just grew, set in a snowy Norfolk landscape not far from where I live.

We don’t often get heavy snow, let alone a white Christmas, in this part of the world, so the idea of my lovers snowed in together was a Christmas fantasy for me, as well as for them.

I hope Giles and Julia’s story gives you a warm glow this winter, wherever you are.

Happy Christmas!

Louise Allen

For the Quayistas Mark 2—

Linda, Jenny, Janet and the Significant Others.

You know why.

Chapter One

When had she last seen snow? It must have been at least nine years ago, before she had left England. Remembered in the heat of a Bengal summer, it had been pretty and fluffy. Not like this, heavy with a subtle, beautiful threat. The great billowing drifts, like ocean waves, were poised to swallow the coach whole. Oh, this was such a bad idea.

There was a convulsive movement beside her, a blurred reflection in the breath-misted glass, but when Julia turned her stepdaughter was smiling, even as she shivered.

‘Miri, darling, I am sorry it is so cold. I didn’t think, I just wanted to be away from that dreadful woman.’

‘Aunt is strange, isn’t she? I suppose she was angry that Father didn’t leave her anything in his will.’ Miri shrugged, slender shoulders struggling to lift the layers of rugs. ‘And I didn’t expect her to like me, but she did offer us a home while you arranged your affairs in England.’

Of course Grace—parental optimism in the naming of her had been severely misplaced—Watson did not like her niece. Miriam was illegitimate, half-Indian and beautiful. What was there not to hate for a bigoted woman with a plain daughter of her own to launch?

‘Did you not realise? My sainted sister-in-law was selling introductions to me, the indecently rich nabob’s widow who must, of course, be in need of a man to relieve her of her wealth.’

‘No! You mean those parties and receptions were to set you out like goods on a stall? No wonder you are so angry.’

‘Too angry to explain properly to you. I am sorry, you must have thought I had lost my mind, dragging you out of there at five o’clock yesterday morning.’ Julia did not often lose her temper, it was not a profitable thing to do, but when she did she was well aware that it was like wildfire over the grass plains of the Deccan, sweeping everything before it.

Miri had meekly held her tongue and left Julia to a fuming silence broken only by curt orders to servants, coachmen and innkeepers. ‘I must have been a perfectly horrid companion yesterday, I should have explained. I overheard your aunt agreeing terms with Sir James Walcott on what he would pay her if I were to wed him.’ She took a steadying breath. ‘I lay awake all night brooding and the thought of seeing her sour face over breakfast was too much.’

‘I rather liked Sir James.’

‘So did I,’ Julia agreed grimly.

‘You are very rich.’ Miri sounded as though her teeth were clenched to stop them chattering. There was only so much that fur rugs and pewter hot water bottles could do against the Norfolk weather on a late December day.

‘Oh, indecently so.’ Julia’s own teeth were gritted, but not because of the cold. ‘And it is a well-known fact of life that indecently rich widows are fair game for any impoverished gentleman who fancies lining his pockets. After all, marrying money is not the same as lowering oneself to engage in trade and actually earn it.’

There was silence as the coach lurched through another drift. It gave Julia ample time to rue allowing her temper to land them here.

‘So what will you do now?’

‘See what this house your father left me is like. I have no hopes of it, but, if it at least has a roof, then we shall stay there for Christmas and by the New Year I will have a plan.’ She always had a plan and usually they were rather more successful than her bright idea of leaving India and returning to England with her stepdaughter and a fortune, expecting to find it easy to make a new life.

She had wanted to give Miri everything a restricted upbringing had denied her stepdaughter, find her a husband to love her. Now she suspected that Miri would have been much happier in India with a dowry, making her own choices. Had she dragged her along because of her own desire for companionship? She had been so lonely throughout her marriage that if it had not been for Miri’s warm affection when her father brought home his young bride she would have gone mad, she thought.

Nothing is easy. Nothing. In England money seems to be a curse for an independent woman. Or perhaps expecting to be independent is the curse in itself.

‘It will be very pleasant to have a real English country Christmas.’ There was that at least to look forward to. ‘Plum pudding, mulled wine, decorating the house with evergreens, sitting around roaring log fires. We will give the staff Christmas Day off and listen to them singing carols. You’ll love it, Miri. I remember it all so well from my childhood. Christmas is wonderful for children.’ She trod firmly on that image and imagined instead a fatherly old butler, a rosy-cheeked cook, cheerful, willing maids and footmen… ‘But whatever else we do, remember that we are two ladies of modest means.’

‘Very well.’ Miri gave a determined nod. ‘We will dress simply and warmly and leave our jewels in their cases. After all, I am not looking for a husband and you do not want one who desires you only for your money.’

That ruled out all the gentlemen of England. Who would want a sallow-faced widow of twenty-five with no connections for any reason other than her money? It was a good thing that seven years of marriage had removed any romantic delusions she might ever have nurtured about the institution. As for Miri, if and when she found a man she wanted, Julia would do everything in her power to make her dreams come true. If this mythical lover deserved such a pearl. And if that meant losing her, seeing her go back to India, then of course she must go. She could not be selfish and hold on to her.

But meanwhile they were shivering in a wasteland. ‘How much longer is this going to take?’ Julia jerked on the check string and dropped the window glass, letting in a blast of dry, frigid air and a dusting of snowflakes. ‘Thomas?’

‘My lady?’ The coachman leaned round and down to face her, his face red with cold.

‘How much further?’

‘A mile or so, I reckon. The snow makes it difficult to judge distance at this pace.’

‘We will stop at the next inn. Miss Chalcott is becoming very cold.’

‘There’s nothing ahead of us now but Chalcott Manor, my lady. It’s a dead end.’

‘It most certainly is.’ She sighed as he straightened up on to his seat, then leaned back down before she could raise the glass again.

‘My lady, there’s someone on the road in front of us. A man on foot.’

‘In this weather? We had best take him up.’

The man turned as they approached, seeming larger and more monstrous the closer they got. Squinting against the snow, Julia could see that the thick white crust covering his head and shoulders added to his bulk, but he was also holding some large black object to his chest.

‘You there!’ Thomas hailed him. ‘Are you in difficulties?’

‘Difficulties? Not at all.’ The response was sarcastic, the voice deep and confident. Julia felt her lips twitch. ‘I am unhorsed and lost and have no feeling in my extremities, but otherwise I am enjoying a country stroll.’

‘My lady bids me say that you had best get into the carriage, sir.’

She opened the door, then gasped as the man turned to face her. ‘What on earth is that?’

‘A turkey, ma’am.’ He hitched his burden up further in his arms and a hideous red and blue head on a wrinkled, naked neck poked out from the front of his greatcoat and produced a raucous gobbling cry.

‘It is alive!’

‘Yes, ma’am. I had noticed. Might I enter? The snow is blowing over your rugs and my boots may freeze to the road if I stand still much longer.’

‘If we wrap it in this, you can lift it in.’ Miri, ever practical, held out a rug.

The man looked up from under his snow-laden hat and his jaw dropped, just a fraction.

Most males were rendered dumb for minutes at a time by their first sight of her stepdaughter. It was wearily predictable, but she supposed she could not blame them. ‘Get on with it, please, before we are buried in snow.’

The turkey succumbed to the rug after a few seconds of frantic flapping and gobbling, the man heaved it on to the seat and climbed in, slamming the door behind him.

‘Drive on, Thomas.’ Julia yanked up the glass and flapped the snow off her skirts. ‘There is no village ahead, sir.’

‘I was coming to that conclusion. My horse went lame some way back. There was a byre with a herd of cows and fodder, so I left it there, hid the saddle in the rafters and walked in the hope of better shelter.’

‘There is nothing along this road but my house, Chalcott Manor. You are welcome to shelter there until the weather lifts. I am Lady Julia Chalcott. My stepdaughter, Miss Chalcott.’

‘Thank you, Lady Julia. Miss Chalcott.’ He managed to look at Miri without actually panting, which raised him a notch in Julia’s estimation. ‘I am Giles Markham, late Captain in the Twelfth Light Dragoons. Is Lord Chalcott at home? He must be anxious with you travelling in this weather.’

‘Sir Humphrey Chalcott is deceased, Captain Markham.’ She saw the question he was too polite to ask. ‘He was a baronet. I am the daughter of an earl and chose to retain my title.’ It was the only thing she had managed to keep from her early life. ‘Why do you have a live turkey, Captain?’

‘I found it in a snowdrift. It’s a very fine Norfolk Bronze, with a label on its leg reading “Bulstrode, Leadenhall Market”. I assume it escaped from captivity on top of a stagecoach bound for the City of London. Christmas is, after all, only six days away.’ He took off hat and gloves and pushed his hand through his hair, which was brown, straight and in dire need of a crop.

Without his hat he should have looked smaller. He did not. Nor any less male and sure of himself. That would be the army, she supposed. A serving officer was unlikely to be a shrinking violet. Although one of those would certainly take up less room. Her skin felt…strange. Julia wanted to shiver even though, quite suddenly, she was not chilled. Odd. Perhaps she was sickening for a cold, which would just about put the crown on this disaster of a journey.

What were we talking about? Oh, yes. ‘And the entire point of turkeys at Christmas, Captain, is to be dead. Dead, plucked and roasted. Not shedding feathers all over the interior of my coach.’

‘I have some sympathy with his daring escape, Lady Julia. I have dodged the French often enough to have fellow feeling.’ Judging by the thin scar on his left cheek he had not always dodged successfully. Captain Markham’s voice was deep, amused and as smooth as warm honey.

Oh, pull yourself together, Julia. It is a man. A large, handsome, masculine creature who is cluttering up your carriage. They are two a penny and all equally mercenary.

‘This is a fine coach, if I may say so.’ Even in the gloom the interior with its mahogany, plush upholstery, brass fittings and heaped fur rugs murmured of luxury and the wealth to support it.

It was almost big enough for him, Julia thought, covertly watching his efforts to keep his long legs under control and his sodden boots away from their skirts and rugs. Men did fill the space up so. This one was a gentleman, the educated voice attested to that. But he was a rangy specimen with a straight nose, a stubborn chin and an excess of stubble. After the smooth, groomed males inhabiting the drawing rooms of Mayfair he was something of a shock to the system. That was all this flustered feeling was, reaction to such a virile creature at close quarters.

‘We were lent it,’ Miri said demurely, lying without a flicker of her long lashes. ‘It is very different from the carriages we are used to in India.’ At least she was keeping up with the conversation and not allowing a pair of long legs to turn her brain into mush. This was what came of indulging immodest and improbable fantasies: they climbed into your carriage at the least convenient moment.

‘India?’

‘We arrived in England three weeks ago, Captain.’ That was better, cool and polite.

‘And are returning to your family for Christmas.’

‘No. We have no family in England, except for the most distant cousins.’ To describe her sister-in-law as family stretched Julia’s willingness to mangle the English language. ‘And you, Captain? Are you on your way home?’

‘Home.’ He said the word as though it tasted of something entirely new and he was not certain that he liked the flavour. ‘I suppose I am. It is a very long time since I set foot in England.’

‘You have been in the Peninsula, sir?’

‘For several years. I have just sold out.’

Why? The war is still going on and he doesn’t appear to be suffering from some disabling wound. The coach turned sharply to the left and Julia caught a glimpse of gateposts. ‘We have finally arrived, it seems.’

‘You are not familiar with the house?’

‘No. It is the only thing my husband left to me. As I met him in India I have never seen it.’ From what Mr Filbert, her solicitor, could tell her, the possession of Chalcott Manor was not going to give anyone the impression that she was rolling in money.

They stopped and all looked out at the redbrick house that loomed through the snow. As a piece of architecture it appeared to be without merit, except for the possession of a roof with no visible holes in it and a number of chimney stacks, both features that were at the top of Julia’s desiderata for a house, just at the moment. A light showed in one of the semi-basement windows, so at least some of the promised staff were present, but there was no rush to open the door. Perhaps the snow had muffled the sound of the carriage.

Paul, the groom, opened the door and let down the step. ‘The snow’s deep, my lady.’

‘Let me.’ Captain Markham jumped down beside him. ‘We’ll trample a path through. Put an arm around my shoulders.’ The two of them moved forward, stamping in unison.

‘What a good thing we found the Captain,’ Miri observed, watching their progress.

‘Thomas and Paul would have managed between them.’ At least the man did not have expensive clothing to ruin. She had noticed the worn boots and the roughly mended cuff of his greatcoat. If he had sold his commission then he ought to have bought himself some respectable civilian clothes with the proceeds and not be traipsing around the countryside in that state.

He came back to them, leaving Paul pounding on the front door. ‘It’s as cold as Satan’s ar—as cold as the devil, ma’am. I would wait there until someone answers.’

‘I am not shivering in a coach on my own doorstep, Captain.’ Or being managed by a man. She climbed down, ignored his outstretched hand and started up the trampled path. Behind her she heard him offering his arm to Miri, who murmured her gratitude. Then her right foot shot up, her left foot skidded to the side and she was falling backwards.

‘Oh—’ The very naughty word in Urdu clashed with a small scream from Miri, then an arm lashed round her waist and she was lifted off her feet and into Captain Markham’s arms. Really, the man’s reflexes were astonishing. So was the strength of his arm—Julia knew she was no lightweight, not with all five feet six inches of her bundled in layers of winter clothing. ‘Thank you, Captain, you may put me down now.’

‘Best not.’ He adjusted his grip, raising her higher against his chest and getting one arm under the crook of her knees.

‘Captain!’

‘No call for alarm, I have you safe.’

That was an entirely new definition of safe. Certainly her heart rate had kicked up in alarm. ‘I am not a turkey to be lugged about.’

‘No,’ he agreed, striding up to the door. ‘You are much easier to get a grip on and you aren’t shedding feathers.’

The door creaked open before she could think of a retort. The light etched a thin ribbon of gold on to the snow.

‘Yes?’ The voice wavered eerily.

She shivered and the arms holding her tightened in response. Oh, for heaven’s sake, this is not some Gothic novel! ‘I am Lady Julia Chalcott. This is my house. My solicitor wrote to say that I was coming to stay. Now kindly open this door properly and show us to the drawing room.’

‘Maa…’ It was a bleat. Which, as it issued from the mouth of a man who looked more like a sheep than anyone decently should, was appropriate. ‘Ma’am? We never heard from no solicitor.’

She felt decidedly at a disadvantage and gave a wriggle. An amused huff of breath warmed her temple. ‘You address me as my lady, and who are you?’

The man retreated into the depths of the dark hall as the Captain strode forward. ‘Light some candles immediately, please.’

‘Yes, maa… Sir. My lady. Smithers, my lady. The drawing room is there, but the fire isn’t lit.’

Nor were the covers off the furniture or the curtains drawn. Captain Markham set her on her feet and waited while she released her grip on his sleeve before he removed the candle from Smithers’s unsteady hand and walked round setting the flame to every candle in sight, then dropped to one knee and thrust a hand into the kindling laid in the hearth. ‘Dry, although I’d not take a wager that the chimney will not smoke.’

‘Er…’

That was an improvement on bleating, but there went her daydream about a cosy house and equally cosy staff. Efficient, cheerful, staff. ‘Tell Cook that we need tea, Smithers. And sandwiches and cake. Then send the footmen to bring in the luggage. I require bedchambers for myself and Miss Chalcott, a maid to attend on us, a chamber for Captain Markham and accommodation for my coachman and groom. Hot water. We will dine at seven.’

‘But there’s only me and Mrs Smithers, my lady. And the Girl.’ He somehow managed to give the word a capital letter. ‘And I don’t rightly know as how we’ve got any cake, nor anything much for dinner, my lady. Just the rabbit pie and the barley broth.’ Smithers’s face was a mixture of bafflement and deep apprehension.

The butterflies that had been flapping around ever since Captain Markham picked her up turned into a lead weight and sank in her very empty stomach. ‘Oh. The beds are aired, are they not?’ It was foolish optimism, she knew as soon as she spoke.

‘Er…’

No, that was not, after all, an improvement on bleating. ‘I had best speak to Mrs Smithers.’ She waited until he shuffled out of the door and turned to the others. ‘Captain, please will you light the fire? We must risk the smoke.’

‘Me lady?’ Julia turned, praying not to be confronted by another sheep, and was rewarded by the sight of Mrs Smithers, a birdlike woman in a vast apron, a ladle clutched in one hand. Over her shoulder could be glimpsed a freckle-faced child of about twelve. The Girl, presumably.

At least the ladle promised food of some kind. ‘Mrs Smithers. Good afternoon. As I explained to your husband, we require beds—aired beds—made up in three chambers. Fires lit. Hot water. Dinner for seven o’clock and accommodation for the coachman and groom.’

The other woman stared, her mouth working, then she plumped herself down in the nearest chair, threw her apron over her head and burst into tears.

Julia took a deep breath and turned to Captain Markham, the shredded remains of her Christmas fantasy fluttering around her like so many falling leaves. ‘Are you skilled at bed-making, Captain?’ she enquired sweetly.

Chapter Two

‘Bed-making?’ Giles drawled. ‘I have more experience unmaking them, I fear.’

He hadn’t thought the remark that risqué, but Miss Chalcott smothered a giggle with her hand and a wash of colour came up over Lady Julia’s cheekbones. She was tired and upset and he admired the fact that she hadn’t followed the example of the cook and given way to tears.

‘I will see that your coachman and groom have what they need, then I will return and light fires, fold dust sheets, chase spiders…whatever you require, ma’am.’

She regarded him, lips tight as she controlled her emotions, a tall woman with skin still glowing unfashionably from years in the sun. Her nose was straight, her eyes were blue and her hair, what he could see of it, was blonde. It was difficult under the brim of that bonnet and with the poor light in the room, but he assumed she was in her early thirties. Certainly her air of command and authority was striking.

‘Thank you, Captain.’ Her voice was still sweet, just as lemonade, imperfectly sugared, was sweet. Then she turned to the servants with a string of clear instructions that had Mrs Smithers mopping her eyes and hurrying from the room and Smithers tugging at the dustsheets as though his life depended on it.

Perhaps it did, Giles mused as he let himself out and walked round the house to find the stables. Perhaps she would produce some exotic Indian weapon and behead the lot of them if they disobeyed her orders.

He was becoming whimsical with weariness, but it had been a long day and his life was so upside down these past weeks that it was no wonder he found himself oddly stirred by this woman. Most likely it was the memory of the weight of her rounded body in his arms, the womanly scent of her.

The coachman and groom were manhandling the carriage into a barn and he lent his weight to the shafts until it was fully under cover. ‘Have you all you need?’

‘Aye, we’ll do, thank you, sir.’ The coachman straightened himself, recognising authority when he heard it. ‘There’s stabling aplenty with bedding and fodder, although it’s a mite dusty and past its best. Shall we take that turkey to the kitchens?’

‘No.’ Giles looked into the stable block. Four brown rumps were all that could be seen of the carriage horses. ‘There’s an empty loose box, he can go in that. This is one turkey that is going to live though Christmas.’ Ignoring their carefully bland expressions, Giles lugged the heaving bundle out of the carriage and into the stall. He scattered some straw, filled a bowl with water and dumped a few handfuls of grain in a corner. ‘There you are, catch a few spiders while you are at it.’

The bird shook its wattles and emitted a furious gobbling, then proceeded to strut up and down, feathers puffed up.

‘Stop carrying on and eat your dinner. There are no stag turkeys for you to scare off and no hens to impress.’ There was a muffled snort behind him, but when Giles turned the two men were industriously hanging up harness. ‘Have you found anywhere to sleep?’

‘There’s a room overhead here with beds and a stove with kindling. We’ll be snug enough, sir.’

‘Go over to the kitchen when you’re ready to eat. There’ll be something. This is not what Lady Julia is used to, I imagine.’

‘Wouldn’t know about that, sir. We’ve only been in her employ a few days.’

Nothing to be gleaned there. Giles retrieved his saddlebag and went into the house through the kitchen door to find Mrs Smithers scurrying between larder, table and range.

‘What are the supplies of food like?’ he asked, stopping the harassed cook by the simple expedient of standing in front of her. The first thing you learned in the army—after the discovery that it was no use ducking in the face of artillery—was to secure the provisions. ‘The roads are deep in snow and more is falling. There’ll be no marketing done this side of Christmas unless we get a sudden thaw, and there’s eight mouths to feed for however long it takes.’

‘Hadn’t thought of that, sir.’ The cook sat down in the nearest chair and managed to compose herself. ‘I’d best take stock. There’s the mutton stew for tonight. We can eke that out with potatoes—we’ve sacks of them in store. Root vegetables in the garden clamp. Then there’s two full wheels of cheese. Dried apples and lots of flour. The butter will last a few days, then there’s lard. I’ve eggs in isinglass and the cow in the byre will stay in milk awhile longer. And game outside for the shooting. It’ll be plain fare, sir, but we won’t starve for a month. Her ladyship won’t like it, though. We never got no letter from the lawyer.’ She sniffed, on the verge of tears again.

‘Her ladyship can lump it,’ Giles said, making her gasp with laughter. ‘Do your best, Mrs Smithers, I’ll see what’s going on upstairs.’

He followed the sound of voices, or rather the series of thumps and flaps and one very clear voice issuing from a bedchamber. The hapless Smithers struggled to turn over a mattress while the Girl gathered up dustsheets and Lady Julia and her stepdaughter sorted linens.

‘Captain.’ She turned as he entered, still brisk, but he could hear the weariness under it and perhaps the relief that there was someone else to help cope. ‘The fire, if you please.’

He set a taper to it, then she had him tucking in sheets on one side of the bed before he could make his escape. ‘Tighter, Captain. Get some tension in it.’

She was certainly making him tense, most inappropriately. Giles wrestled the coverlet straight, then gathered up pillows in a strategic attempt to disguise just how tense.

He was handed a pile of pillowcases. ‘When you’ve done those we will be next door.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’ It was tempting to tease her with a salute. Instead he admired the way her hips swayed as she strode out of the door. Giles stuffed pillows and told himself this was not some bivouac in the Spanish mountains and Lady Julia was not a camp follower.

The next chamber was smaller. He lit the fire, then went to help Miss Chalcott drag a heavy curtain across a window, but even with that in place the draught still stirred the bedraggled bed-hangings. The fire smoked foully. Giles kicked it out with a muttered oath. ‘I’ll take this chamber, I’m used to the cold. I’ll see if there’s another room with a clear chimney, otherwise you ladies will be better together in the first chamber.’

The army had certainly been good training for this house. He’d been in more comfortable tents in the snow before now, he mused as he followed Miss Chalcott into the next room along. The chimney there obliged by drawing steadily. It was a small room, but that made it easier to heat, he pointed out as he helped her make the bed.

‘Thank you, Captain.’ Her smile was enchanting, he thought, discovering that he was admiring her as he might an exquisite artwork, not a living woman.

On the other hand there was certainly one of those next door, judging by the sounds penetrating the wall. ‘Smithers, is there another mattress? Captain Markham cannot sleep on that—the mice have been in it.’

‘Lady Julia is obviously used to dealing with servants,’ he remarked as Miss Chalcott draped blankets over a chair in front of the fire.

She laughed. ‘She has had a great deal of practice.’

‘You had many servants?’ he asked, puzzled. A borrowed carriage, plain, sensible gowns, this frightful house her only legacy from her husband… Something did not add up.

‘Seventy, perhaps. Look at this fabric! Moths, I suppose, though by the size of the holes I would not like to meet one.’

‘Seventy?’

‘Oh, everyone in India has servants if they have any kind of a household at all. Inside servants, outside servants, the grooms, the gardeners, the sewing women and the laundry, my father’s business… It all adds up and it costs a fraction of what it does in England.’

‘Your father was a man of business, then?’

‘My husband was a merchant, a trader in many things.’ He had not heard Lady Julia’s approach. ‘But, despite the common misapprehension here, not every man who trades in India is a nabob, wealthy beyond compare. Or even wealthy at all.’

‘I beg your pardon, ma’am. I allowed the informality of our circumstances to lead me into curiosity.’ He really had been in the army, and in the wilds, too long if he had forgotten not to discuss money or trade. As an earl’s daughter Lady Julia’s marriage might have been deemed acceptable if sweetened by vast wealth, but a mere merchant would put her firmly on the wrong side of the social dividing line. Why had her family allowed it?

‘No matter. India makes everyone curious, I find.’ Lady Julia came further into the room and he saw how weary she was, for all the firm voice and straight back. Then she smiled and he realised something else. He had been quite out in placing her in her thirties. Surely she could not be more than twenty-five or six, at the most. And Miss Chalcott was, what? Twenty, twenty-one? Which meant her husband, unless he had been sowing his wild oats in India at a precocious age, must have been in his late forties at the very least when he married her.

An earl’s daughter marrying a not very successful India merchant twice her age. How had that come about? He felt the curiosity stir like the flick of a cat’s tail at the back of his mind and bit down on the question he had nearly allowed to escape.

She ran one hand over the draped blankets and wrinkled her nose. ‘This house had been in my husband’s family for years. I had no idea it had been so neglected.’

Considering that she had travelled thousands of miles to discover her expected security was a ramshackle house miles from anywhere, Lady Julia was showing remarkable resilience. Perhaps she was planning to go back to her family.

‘Mrs Smithers should have water heating, although I doubt it will run to a bath. I will have some sent up to your chamber, Captain. Until seven o’clock and dinner.’

‘I’ll see to the water myself.’ Giles almost told her to go and rest, then decided that telling any female that she looked weary was not tactful. ‘Until dinner time, ladies.’

* * *

Captain Markham had shaved, donned a clean, if rumpled, shirt and neckcloth, and made some improvement to the state of his breeches and boots. He also looked as though he had managed to snatch some sleep, which was more than Julia had, she thought resentfully as she regarded him across a dinner table much in need of polishing.

She had lain on the bed in her dusty, draughty chamber and willed herself to sleep, but oblivion would not come. What had kept her awake was the sickening realisation that she had allowed a sentimental memory of childhood Christmases to blind her to reality. She had set out on this journey in a temper, clinging to the belief that at the end of it would be a charming country house, complete with its charming staff. It would all be modest but comfortable, warm and safe.

Instead she and Miri were stranded in a cold, neglected house, miles from anywhere, with three nervous servants. Plus a turkey they couldn’t even eat. Plus one down-at-heel army captain who looked at her in a way she could not decipher, but which made her both irritated and… aroused, damn him. She had rescued him from a snowstorm. He should be as exhausted as she was and yet he just looked tough and competent and ready to lead a cavalry charge if necessary. Just as soon as he had finished reducing her to idiocy with one glance.

He didn’t look at Miri that way. He treated her with perfect respect, as though she were no more than the average unmarried girl and, after the first shock, appeared utterly unmoved by her beauty.

‘More potatoes, Lady Julia?’ Not that he didn’t treat her with respect also. His manner was perfectly correct, so correct that she kept telling herself that she was imagining the warmth in his regard, the occasional double meaning in what he said. It must be her imagination. She had felt an immediate attraction to him in the carriage so perhaps now she was reading an answering interest where there was none at all. How lowering.

‘Thank you.’ The food was adequate. Plain but hot, dull but filling. Miri ate with a delicacy that concealed any distaste for what was unfamiliar for both of them.

‘After shipboard fare for months this has to be an improvement.’ She reached for the pepper. ‘But if we stay I must order some spices. I cannot endure such bland seasoning much longer.’

‘You are in two minds about remaining?’ Captain Markham twirled the stem of his wine glass slowly between fingers and thumb. The cellar had revealed a number of dusty bottles of dubious vintage and they were cautiously sampling one.

‘This house is a disappointment,’ Julia admitted. More than the house, if she was honest. After six years of brutal realism and clear thinking she had allowed freedom to go to her head. She had let herself dream and had followed that dream. She looked at Miri and acknowledged that she had been selfish as well. All for the very best of motives. ‘I will sell it.’

‘You will achieve a better price if you wait until the spring,’ Markham suggested. ‘Once it has been cleaned and had a lick of paint and the sun shines on it, it might be transformed.’

‘And a maharaja on a white elephant might come down the driveway and offer me chests of gold for it,’ she retorted and was rewarded with a laugh from Miri.

They ate the apple pie, the desire for cream politely unspoken. ‘There was no port in the cellar, I gather,’ Julia said as she and Miri stood up. ‘We will leave you to your wine. If you will excuse us, we will retire now.’

‘Of course.’ The Captain got to his feet. ‘Goodnight, ladies. And my thanks for rescuing me from the snow.’

Julia saw Miri to her door, then turned, restless, and walked back to the head of the stairs, back to her own door. Dithered. What was the matter with her? She never dithered. Perhaps fresh air would steady her. If nothing else it might drive her to her bed and then, surely, she would sleep.

She jammed her feet into her half-boots and swung her cloak around her shoulders. The front door opened with its sepulchral groan and then she was picking her way cautiously towards the stables, the only destination for a stroll in the freezing darkness.

It had stopped snowing and she could see the glow from candles in the room above the stables and the drift of smoke from the stove chimney. Below, the light of one lantern shone out across the trodden snow and she followed it to the door and went in.

The air was warmer here and smelt of dusty hay and horse. Four heads appeared over the half-doors of the boxes, but Julia did not approach them. She missed her mare, Moonstone, and these handsome beasts were no substitute for a brave little horse who was afraid of nothing, not even elephants. Another mistake, to have sold her, but Julia had thought she was being strong and decisive.

An irritable sound drew her to the door without a horse behind it. Scratching about in the straw was the turkey, his pompous dignity returned now he was free of the rug. He thrust out his chest and spread his tail at the sight of her.

‘Ridiculous creature. You’ve no doubts, have you? You make an idiotic dash into a snowstorm and certain death, but of course you are rescued and looked after and now you will escape your proper fate.’

Whereas she had made an idiotic escape and ended up here. And if she wasn’t careful and didn’t make the right decisions she would find herself trapped, or lured, or simply cornered into marriage—the proper fate for a rich widow. ‘Oh, what have I done?’ She bent to rest her forehead on her arms, crossed on the top of the loose-box door.

‘Well, what have you done?’ a voice behind her asked. Captain Markham.

‘Let my heart rule my head,’ she said wearily without moving. ‘I left India full of nostalgia for England, dragging Miri behind me. I hate it here.’

‘What will you do?’ He was so close she felt her skirts brush against the backs of her legs. For a moment she thought he would touch her, but he stayed still. It must be she who was shivering with reaction. Not with cold. Not with his heat at her back.

‘Go back to India. I know where I am there.’ Who I am.

‘Do you love it so much?’ Giles Markham asked softly, the deep voice intimate, as though he asked her about her feelings for a man.

Julia straightened, but she kept her gaze on the turkey cock. Was it her imagination or could she feel Markham’s breath, warm on her neck?

‘Most of the time I fought it as though it was a person, an enemy. But sometimes it was an exotic fairy tale. It can take your breath with beauty and magic so deep and rich it cannot be true. The people. The colours. Oh, and the mornings…just at sunrise, when it was cool and clear and the whole impossible place was coming to life and I would ride my mare and the world was mine.’

‘That sounds like love to me. An attraction that goes soul-deep, but which you fought against even as it seduced you.’

‘You are a romantic, Captain.’

She shivered and he moved closer, put his hands on the stable door either side of her, caging her against his heat, the muscled wall of his body. There were responses she should make to that. A sharp elbow in his ribs, the heel of her boot on his toes, a jerk backwards with her head into his face. She knew all the moves, had used them before now.

Julia turned within the tight space and stared at the top button of his waistcoat. Hitting this man was not what she wanted. ‘A romantic,’ she murmured.

He made no move to touch her, to crowd closer. ‘Only a man who has ridden at dawn over wide plains before the battle started, who has seen the mist rise and heard the birds begin to sing and who has tried to hold the moment, hoping against hope that the sun will not burn away the mist and the guns will not begin to fire and that the earth will not be reddened with blood.’

‘That seems strange for a soldier to say.’

‘Soldiers are not immune to beauty. Only a few of us want to fight and kill for the sake of it. But when the mist vanishes and the guns begin, then we forget those moments of peace and plunge into hell.’

‘Who do you fight for, Captain?’

Chapter Three

She had surprised him. ‘It is my duty,’ Giles said after a moment.

‘Is that always what soldiers fight for? King and country? Or did you become a soldier to impress your lady-love?’ She had meant to tease and he smiled when he shook his head. ‘So you have been fancy-free while you break hearts across the Continent.’

Darkness swept through his gaze, his jaw hardened. Julia glanced away, shocked and guilty. In her own awkwardness she had stumbled into something private, something that hurt.

After a moment she felt the big body caging hers relax and she dared to look up and meet his eyes. Grey eyes with gold tracing out from the pupil like tiny flames in the lantern light. The moment was a fragile bubble—one wrong move and it would be gone again like that morning mist. She reached up her hands and pulled down his head, lifted her lips to his and the iridescent shimmer of the bubble enclosed them both.

There was a momentary pause, the faintest hitch in his breath, then the Captain’s lips moved over hers, firm, slightly cold. His tongue touched the seam of her lips, shockingly hot against her own chilled mouth as she opened to him.

Could he tell that she had hardly ever been kissed? Julia made herself hold back, forced down her need to simply drown in his embrace, drag him to the heaped straw, discover, finally, what it was like to know a virile man in his prime.

Over-eagerness would betray her inexperience. She let him lead, followed the strokes of his tongue with her own daring movements, allowing him to angle her head for his taking. Giles Markham knew what he was doing, she thought hazily, striving to focus, to learn and not to lose herself in this assault on her senses. On the few occasions Humphrey had actually kissed her she had been frightened by his forcefulness, repelled by the taste of him—cheroots, heavily spiced meat, strong spirits.

The taste of this man was enticing, which was puzzling as it seemed to be made up of faint traces of tooth powder, wine and…masculinity, she supposed. There was the heat of his mouth and the cold of his skin, the scent of plain soap and the dusty hay of the stables, the comforting smell of horses. And there was his body under her hands. Muscled shoulders, short hairs on his nape, the strength of his arms as he held her.

When he released her she swayed back against the stable door, dizzy and enchanted, her hands still on his shoulders. So this is what it is like. After all these years. At last.

‘Julia?’

Just her name. She found she liked it on his lips.

‘Giles.’ She liked that, too. A good, straightforward name. She let her fingertips stray to the bare skin of his neck above his collar and even in the dim light saw his gaze darken. You want me. Tell me you want me.

‘You are upset, cold, tired,’ Giles said as he stepped back a pace, leaving her cold and alone, her hands still raised. ‘This is not a good time to begin—’

‘Begin what?’ Cold, tired and upset was sweeping back to smother dizzy and enchanted.

‘A dalliance, I was going to say.’

So that was what she desired. Julia realised that she did not have the words for this. Giles probably knew all about dalliances and he was tactfully making it clear that he did not want one. And he was not exactly tearing himself from her arms with deep reluctance. How humiliating.

Julia found the cool smile, the mask she wore when bargaining, whether it was with Rajput gem dealers or desert camel breeders. ‘Goodness, how serious you are. Dalliances indeed! I had merely the impulse to kiss when I found us almost nose to nose.’ She laughed, aiming for sophisticated amusement, fearing pathetic bravery. Share the jest. Please.

He smiled crookedly, almost as though he did not find any humour, but his eyes were warm, the gold flames intense. ‘Of course. Forgive me. If you give me a moment to check on the livestock, I will walk you back to the house. It is treacherous underfoot.’

‘Certainly.’ How cool she sounded. Not at all like a woman who was quivering with desire, lapped by heat, almost speechless with embarrassment at her own recklessness. When Giles came back from checking water buckets and feed she was ready to slip her hand under his proffered arm, curl her fingers around his sleeve.

He was rock-steady as they negotiated the yard, lit by starlight reflecting off the snow. ‘My goodness, I am chilly.’ An exaggerated shudder would hide her shaking, surely?

Once inside she went directly to the stairs—walking, not breaking into a run, not fleeing to her room to bury her head under a pillow. ‘Would you check the doors and windows are secure and the fire safely banked? I do not yet know how much reliance to place on Smithers.’

‘Of course. Goodnight, Lady Julia.’

‘Goodnight, Captain. Sleep well.’ He would make sure all was safe, she was certain of that. Giles Markham made her feel protected, sheltered. Rejected.

Sleep well. Lady Julia, Julia, had a sense of humour hidden under that baffling exterior because she surely couldn’t have been serious with that blessing. Giles hauled the blankets up over his ears and wondered why the arousal was not keeping him warm. Or why the cold was not killing the arousal, come to that. This was the worst of both. He was stone cold and hard as a hot icicle.

You shouldn’t have kissed her, common sense pointed out. She kissed me first, came the answer from considerably south of his brain. Yes, but you were going to kiss her, weren’t you? Telling yourself she needed comforting, pretending that all you wanted was to offer a shoulder to cry on. Haven’t you learned your lesson? You start out in a fit of gallantry, or of lust, then you get yourself tangled deep in whatever webs they are spinning and you end up as damaged as you would after a bayonet in the chest.

He was a soldier—that was what he was, what he did. What he had been, he reminded himself, giving the pillow a thump. No more.

Yes, but… That was what was keeping him awake, almost more than his frozen feet and the throb of desire. She kissed me and she had no idea what she was doing.

Not that it had been any less delightful for that. Julia had tasted delicious, her lips under his had been sweet and generous, her body curving into his had promised an abundance of the femininity that her practical manner struggled to deny. Yet she was a widow and, from what had been said, had been married and in India for several years. So what was the truth? A marriage in name—or was the husband a complete fiction? In which case, was she even Lady Julia Chalcott and the daughter of an earl?

A blast of wind hit the window panes, sending a draught swirling around the room. Giles swore and got out of bed, still fully dressed save for his neckcloth and boots. He had slept like a log in far worse conditions than this, but not if there was an alternative. He bundled up the bedding and let himself out of the room, then went down to the drawing room, where at least there was a fire.

He made himself a nest in front of the hearth on top of the sofa cushions and set to work on the sullen coals. By the time he had a cheerful blaze going he felt warmer and his brain was beginning to focus. He climbed the stairs again, dug in his bag for the thick red book he had bought to study, that had cost too much to throw away as he’d ploughed through the snow.

Giles settled back into his makeshift bed before he began to investigate the Peerage and Baronetage.

Sir Humphrey Chalcott, second baronet, born London 12th May 1752.

He would be sixty now, if he had lived.

Only son…

Married 1804, in Calcutta to Julia Clarissa Anne, daughter of Frederick Falmore, Fourth Earl of Gresham.

No first wife, so Miss Chalcott must be the daughter of a mistress.

Giles looked for the Falmores. Julia had been born in 1787, the only child of the Fourth Earl, who had died in early 1803, five years after his wife. The title passed to the son of his youngest uncle. Giles did the calculation. She had married a man thirty-five years her senior when she had been barely seventeen years old.

Who would put a grieving, orphaned girl of sixteen on a ship to India? The ‘fishing fleet’ was for the desperate and the poor, the plain or the otherwise ineligible women seeking a husband eager to take any British wife of gentility as they struggled to make their way in India.

If Julia really was who she said she was, then perhaps her husband had been unable through illness or infirmity to consummate the marriage to his young bride. He had obviously once been virile, Miss Chalcott was proof of that.

Giles threw another log on the fire, blew out the candle and settled down to sleep, his curiosity now thoroughly aroused. Which was, he concluded as he finally began to drift off, rather more comfortable than what he had been suffering from earlier.

There were doubtless more embarrassing social situations than meeting over the breakfast cups the man you had inexpertly kissed the night before and who had then firmly but kindly rebuffed you. Just at the moment Julia couldn’t think of any and she was applying her mind to it when Giles opened the dining room door.

Having all one’s clothing drop off in the middle of a dinner party? Walking in on the Governor General in his Calcutta mansion while he was pleasuring his mistress on the billiards table?

‘Good morning.’

She dropped the sugar bowl, sending lumps of sugar scattering across the table.

‘Julia!’ Miri was laughing at her. ‘Whatever are you thinking about? Good morning, Captain Markham.’

‘Billiards,’ she managed.

‘And what is there about billiards to make you blush?’ Miri was intent on teasing.

‘If you must know, I was thinking about the Marquess of Hastings. His billiard table. Government House.’ She cast a harassed glance at Giles, who had seated himself at the end of the table. ‘Good morning, Captain. There is bacon, eggs, bread and butter. You could ring for cheese. There are also some preserves. Damson, I think. Tea? There is no coffee or chocolate.’

And if I keep on talking long enough the floor may simply open up and swallow me.

‘Thank you.’ Giles accepted the tea cup. ‘What is there about the Marquess of Hastings and billiards to bring the colour to your cheeks? Is he such a bad player?’

‘No, I am.’ The floor remained disappointingly intact and Giles’s—Captain Markham’s—faint smile remained provoking. ‘It has stopped snowing. Perhaps the roads will be open soon.’ And you can leave. Please. Before I make more of a fool of myself than I have already.

‘I’ll go out and see, although I doubt it. The temperature is as low as ever, so nothing will have thawed.’ He buttered a slice of bread and addressed himself to his food while Julia sought for innocuous topics of conversation.

‘I’ll come with you,’ Miri announced. ‘Mrs Smithers has some stout boots that she said she would lend me.’

‘Have you ever seen snow before?’ Giles asked.

‘No, not before yesterday. It is very beautiful, but rather frightening.’

‘There is no danger if we stay near the house, which I suspect is all we will be able to do. It is best not to take liberties with snow, although I’ve moved troops in worse in an emergency. But it is a sneaky killer and it is best not to provoke it.’

He sounded utterly matter-of-fact and professional about what must have been a nightmare. Julia cast a covert glance at the firm jaw and the broad shoulders and found she could easily picture Giles leading men through any kind of danger and doing it well. He was still talking to Miri when she pulled herself out of her imagination.

‘We can build a snowman if you like. Won’t you join us, Lady Julia?’

‘Thank you, no. Please do not let Miss Chalcott get cold. She is not used to low temperatures, let alone these conditions.’

Those unusual grey eyes were quizzical. ‘Neither of you are, which is why it would be unwise to wander about outside alone at any time.’

‘That all depends what one encounters, doesn’t it?’

Giles’s eyes narrowed and, to her confusion, he smiled, not at all embarrassed. Miri, apparently blissfully unaware of any cross-currents, beamed at her. ‘Please come, too, Julia. It will be fun. There are sure to be more boots.’

Of course it will be fun. Miri would love the novelty of the snow and she was a miserable friend to grudge joining in, just because she had made a fool of herself last night. ‘Very well. Let us have fun.’

* * *

The sun was shining when they emerged, swaddled in layers of coats and scarves. Giles followed the partly-filled wheel ruts to the gates. ‘Not as bad as I feared,’ he reported back.

‘Thank heavens for that.’ Julia stamped her feet in their layers of woollen stockings inside the clumsy boots. ‘Is the road clear?’

‘The hedges have stopped the snow drifting off the fields for as far as I can see, although it may be bad further on. It is still too thick for the carriage and too soon to try on horseback. We may get out by Christmas if this weather holds. Now, snowmen.’

He showed Miri how roll a snowball across the lawn so that it grew. ‘We need a big one for the body and a smaller one for the head.’

‘Let me.’ She pounced on the ball and began to push it, laughing with delight, her breath making white puffs in the air.

Giles left her to stand beside Julia. ‘Shall we walk along the edge of the shrubbery, see if there are any evergreens for your Christmas garlands?’

‘Is it worthwhile, decorating this place?’ A nice safe topic.

‘Walk, before your toes freeze.’ He possessed himself of her hand and tucked it under his elbow before she could object, studying her from his superior height. She was not used to having to tip her head back to meet a man’s eyes. ‘You are determined to be miserable, aren’t you?’ he enquired.

‘No!’ She glared up at him, indignant. ‘I am determined to get out of here, that is all. Poor Miri, dragged all this way from home. I was mad to even contemplate it.’

‘Poor Miri?’ He tipped his head towards the lawn where her stepdaughter was already working on a second snowman’s body, every line of her bundled-up body radiating enjoyment.

‘Snow is a novelty. So is being cold, being snubbed, feeling homesick. I wanted to do the right thing for her, I told myself. Now I wonder if I wasn’t being selfish in demanding her company.’

‘What was it like for you, arriving in India, being hot, being homesick? Not snubbed, I imagine. Not an earl’s daughter.’

He was curious, but she was not surprised. She would have found it strange if he was not. ‘No, not snubbed.’ The temptation to pour it all out into a sympathetic ear was almost overwhelming. Instead she said what she had been avoiding all morning. ‘I must apologise for last night.’

‘Whatever for?’

‘If you had pounced on me in the stables, forced a kiss on me, you would be apologising.’ She risked a sideways glance when he remained silent.

‘You are very refreshing, Julia.’ When she frowned up at him the corner of his mouth kicked up, emphasising the scar on his cheek. ‘If I had done that then, yes, an apology would be in order unless it was obvious that a kiss was welcome. But I could have stepped away at any point, which might give you a clue that I enjoyed it. I assure you, I would have fled screaming if I had been unwilling—the door was right behind me.’

‘How very gallant you are, Captain. You kiss the poor, needy widow, you refrain from taking advantage of her and then you protest that you enjoyed the experience.’ She must stop talking now before she made any more of a pathetic spectacle of herself.

‘If you are suffering from a lack of male attention, Julia, then I can only assume that the passengers on the ship and every man in London between the ages of sixteen and sixty had something seriously wrong with them.’ There it was again, that narrow-eyed, very masculine assessment that had her pulse pounding.

Oh, yes, the men on the ship had looked. They had seen either a rich widow ripe for the plucking or her beautiful stepdaughter to be seduced. Or, in one or two cases, both. What none of them saw was a woman yearning for experience, for passion and for a virile man in his prime to deliver them.

Well, she had a virile, attractive man by her side at this moment. One who appeared to be discreet and considerate. She could be a coward or she could risk a monumental snub and tell him what she wanted. Julia took a steadying breath, but Giles was before her.

‘Tell me how you came to be in India, married so young to a man who must have been much older than yourself.’

Why not? None of it was a secret and she had already abandoned any pretext of pride with this man. ‘I was poor and unlucky in my relatives,’ Julia began. ‘My father died five years after my mother, when I was sixteen. He had married below him, his family said, and it was good that he had no son by such an unsuitable woman, a merchant’s daughter. The title went to his cousin, who was horrified to discover the state of the family coffers. Papa was not the most provident of men and there was no money, not enough to maintain the estate as it should be.’

‘One can understand the heir’s feelings,’ Giles observed.

‘Cousin Richard said I was a further drain on his pocket and that he had no intention of funding a Season for me the following year. An acquaintance was going out to India, so I could make myself useful by accompanying her as a companion and then I was sure to pick up a husband for myself. The problem was solved.’

She glanced up at his face when he said something sharp under his breath. He looked appalled. ‘You were sixteen, bereaved.’

‘I was also exceedingly pretty and his daughters are rather plain. I can say it now because my looks did not survive long. I was blonde and curvaceous and I had a beautiful roses-and-cream English complexion. Enchanting, though I say it myself. I arrived in Calcutta just as the cholera did. It killed thousands, amongst them many of the eligible young men who had come down to meet the Fishing Fleet. I caught it, too. They shaved my head because of the fever and when I recovered I was as thin as a rake, the roses had fled and my hair grew back straight and much darker. My travelling companion was dead, my looks gone, my pockets empty. I was desperate.

‘And so Sir Humphrey Chalcott won himself the daughter of an earl.’

Chapter Four

Giles tried to imagine what it would have been like for a girl scarcely out of the schoolroom to find herself in an alien land, weak, abandoned. Where had she found the strength to carry on?

Julia’s voice was quite steady as she told her tale, almost as though she spoke of someone else entirely. ‘Sir Humphrey thought he was acquiring status and influence. What he did not realise until too late was that the new earl had no intention of giving him anything, let alone the allowance he was hoping for.’

‘He was much older than you were.’

Julia nodded. ‘I suppose I hoped for a substitute father. I soon learned that he couldn’t even be a decent parent to his own daughter, let alone comprehend the fears and needs of a young bride.’

They came to a gap in the planting. Julia waved at Miri, who now had a line of five snow bodies in descending order of size. ‘I think Miri is building a snow family. She was the one bright spark at first. Her mother died when she was fifteen so she was shut away in the women’s quarters. She is four years younger than me, the sister I never had.’

‘And your husband was not a successful man?’

‘He was self-indulgent, indolent and had made himself ill by surrendering to all the temptations of the east. The food, the drugs, the women. He did not have to lift a finger to live a comfortable life, so he did not. He never saw it was his fault that he did not achieve the wealth of other merchants, who did apply themselves.’

They reached the corner of the shrubbery and Giles ducked under a snow-laden branch and into the shelter of the plantings. With the evergreens arching overhead the winding path was almost clear of snow.

‘It was not as bad as it might sound.’ His silence had left a space that she seemed compelled to fill. Giles wondered whether she had bottled all this up for so long that she was confiding things that she never had to anyone else. ‘You can live much better in India on little money than you can over here. I rapidly learned to be a housekeeper.’

‘It must have been hard, even so. A strange and alien land, marriage to a man like that.’ He felt caught up in her story. Here, for the first time in a long time, was a woman who told the truth without artifice, just as she had asked for his kiss with total simplicity.

‘I learned to fill my time.’ Julia made a business of adjusting her shawl. ‘So that is my story. Now you must tell me yours, Captain Markham.’

‘Is it not to be Giles, this morning?’ He snapped off a sprig of holly, laden with berries, and tucked it in her bonnet.

‘No. You know why not. I made an error of judgement last night.’ She put up her free hand, touched the holly as though to pluck it out again, then left it where it was.

‘The timing, perhaps, with us both tired, was not ideal.’ She had kissed like a virgin and he had reacted instinctively to distance himself, he realised. Giles tried a little cautious fishing. ‘You miss some aspects of marriage, no doubt.’

That provoked a sudden burst of laughter. He had never heard her laugh before and he grinned back, enjoying the way those blue eyes sparkled, the curve of that lush mouth. All the severity in her face vanished, just for a second. Then the laughter was gone.

‘By the time he married me my husband’s amorous days were long past. His health would not allow him to make a great deal of effort, especially as I think he found the whole exercise humiliating. I had none of the training of the Indian courtesans he was used to. They can pretend passion, feign an amorous attraction that it was completely beyond me to attempt.’ She shrugged. ‘These past four years I might as well have been a widow.’

‘There were no children?’ He regretted asking the moment he saw the way her face tightened and her shoulders braced.

‘No.’ Julia released his arm, reached out to pluck an ivy tendril and began to fashion it into a circle. ‘I cannot think how I can speak so frankly to a man about this.’

‘I am a stranger. You’ll never see me again.’ And we are met by chance on this snow-covered island of ours, bound together for a few days. He felt his body stir and harden as the temptation began to form into intention. If she is willing…

Giles picked more ivy and held the strands out one by one for her to add to her wreath, enjoying the concentration on her face as she wove the whippy lengths, struggling with the thickness of her gloves. Her brows were drawn together, her teeth were closed on the fullness of her lower lip and she looked sensual, intelligent and flustered, a heady combination. ‘I imagine you found no shortage of gentlemen willing to offer you diversion.’

He surprised a short, bitter laugh from her. ‘I had married the man and, whatever his faults, he gave me shelter when I was desperate. Besides, I made myself too busy to be tempted. There was a business to run.’

‘You managed your husband’s affairs?’ That he could well imagine.

‘Hardly. Humphrey would never have allowed a woman to make decisions. But I acted as his representative, travelled on his behalf, carried out his instructions. That gave me freedom, the chance to see more of India.’

Her face was vivid with remembered pleasure, the colour up in her cheeks. He had no idea how she could denigrate her appearance, mourn her lost beauty. Didn’t the woman have a looking glass? ‘You could travel safely?’

‘I had two huge wrestlers as bodyguards. No one would have dared rob or attack me when they were there, I assure you!’

Julia held up the wreath, head on one side as she studied it. ‘Not bad. It will make a base for some holly and fir cones and I will hang it on the door to greet our numerous callers.’ She looped it over her wrist, then took his arm again. ‘Now you tell me your story, Captain Giles Markham.’

What to tell her? The truth, he supposed. To a point. ‘Only son of a country clergyman, destined for the church and determined on the army. I don’t know where that came from, but I rode almost as soon as I could walk. I learned to shoot, enjoyed swordplay. Led my friends into trouble and, I suppose more helpfully, out of it. I knew I hadn’t the faith to be a clergyman, but the army seemed to offer excitement with honour.

‘My godfather bought me my first commission, saying I might as well have his legacy to me while he was alive and I needed it. Then last year I received a field commission to captain. Two months ago it became clear I needed to come home for family reasons.’ Home to an inheritance of debts. He had more than a little in common with her cousin.

‘You must have done something outstanding to merit a field commission, I know that. A Forlorn Hope? Is that what they call those appallingly dangerous attacks where everyone is a volunteer and if it succeeds against all the odds the survivors are almost guaranteed promotion?’

Giles shrugged. He was never comfortable talking about fighting. The battle was against fear and against bad luck and it sounded like cant to prate about courage and honour. Those were private things. ‘I wasn’t going to get promotion any other way, there was no more money to buy one and I had no intention of spending my career as the oldest lieutenant in the British army.’

That day he had felt that nothing else mattered beyond winning promotion because nothing else in his life was true. The softer things—a woman, love, a family—they were not for him because he could not trust his own heart, his own judgement. From then on, if he survived, the army would be his life. For life.

He had fought until he arrived filthy, tattered and bloody, on top of the breach, the standard in one hand, his sabre in the other, his feet on rubble and dead bodies and a French officer surrendering to him. Afterwards they had praised his courage, his leadership, his gallantry. He told himself that was all that mattered.

He had been silent too long, lost in his thoughts. ‘An appalling experience, I imagine,’ Julia murmured.

His face must have been betraying him as much as his still tongue. ‘After a few days I realised I had lost whatever naïve ideas I still had about war. I’d been down into hell and survived. It made me a better officer.’

‘And yet when we first met you said you were late of the dragoons. After going through hell to gain your promotion, you left it.’

The unasked questions struck at his pride. Did she think he had lost his nerve, couldn’t face fighting any more? He had led a forlorn hope to secure his career as an officer and within months another kind of duty had made all that meaningless.

‘My family needs me,’ he said. ‘Things have changed. People depend on me.’ He did not understand that duty yet. It had never been intended that he should. But now it was on his shoulders and he would have to learn to carry it.

‘That is good to hear.’ The hand tucked under his arm tightened for a moment. ‘A man who will make a sacrifice for his family, put his own ambition aside for them. You must love them very much.’

I don’t know them, he wanted to say. They are strangers who will resent me. He could tell her what he had inherited, tell her anything, he sensed. But then he would not be Captain Giles Markham any longer, he would be the stranger he must become, and he wanted to hold on to the man he was now, just for a few more days. That isn’t too much to ask, is it?

They had reached the glade at the centre of the shrubbery. Giles turned and positioned Julia in front of him, toe to toe. He could forget the army, forget what lay ahead, in a brief affaire with this woman, if that was what she wanted, too.

‘What do you think you are doing?’ she demanded, the sharp question enchantingly at odds with the uncertainty in her eyes.

‘Remember I told you I could have fled screaming when you kissed me?’

‘Yes.’ She looked at him warily, but she did not move. Yes, she wants me at this moment just as much as I want her.

‘If you look behind you will see the path out of the clearing. A perfect escape route if this provokes the urge to scream.’ He took off his hat, then, hands at his sides, he leant in, brushed his lips over hers, closed his eyes.

Julia gasped. The pressure of warm lips on hers increased, but his hands stayed still. Her decision then. Flee screaming as the provoking man suggested, or…not. She jerked at her bonnet ribbons, tipped the thing off her head and into the snow, flung her arms around his neck and returned the pressure. Giles took one staggering step backwards, then his arms were around her.

‘Steady,’ he murmured. ‘There’s all the time in the world.’

Oh, yes. Julia made herself relax, eased the stranglehold, as all her senses flooded back to her. She knew how to assess the quality of silks and cottons by touch, the variety of wood by its weight and strength. Under her hands his hair was silk, a rough, wild variety turning into velvet where it was cropped closer at the nape. His neck was teak, so were his shoulders, his chest. She did not dare think about his thighs, pressed against hers.

She had learned to grade perfumes, spices and essential oils by their scent, by the subtleties of taste. Her tongue stroked over his and discovered tea and that spicy, tantalising man-taste again. He smelt of man, too. Clean linen, slightly musky skin warming under her hands, an overtone of leather, a hint of pepper.

Giles held her, his hands unmoving, only his mouth caressing her, creating an infinite variety of subtle touches and provocations. She had thought a kiss would be an exchange of heat and desire, straightforward, blatant even. But this… She sighed into his mouth and he caught her lower lip between his teeth, gently worrying it as he sucked at the fullness.

She sighed again and he groaned, deep in his chest and finally, wonderfully, his hands moved, slid down. Cupped her behind through the layers of clothes and lifted her against him. Warmth and steady strength and something very like trust. And excitement. She needed to tear his clothes off. She wanted him to tear hers off.

‘The weather is an excellent chaperon.’ Giles released her. ‘There is no danger of things getting out of control when every flat surface is under snow.’

He was making light of this, treating that kiss as though it had been a fleeting moment of flirtation. Nothing to be embarrassed about, simply something that two adults might exchange when they found a mutual attraction. Julia found she could smile. ‘We would sink without trace.’

‘Or start a thaw.’ There was more heat in his regard than she had expected. Perhaps she was being naïve to imagine that this was mere flirtation. Did he want the dalliance he had spoken of last night? Did she?

‘Julia! Do come and help!’

‘Miri is calling. I expect she needs instructions on snowmen.’

Giles picked up her bonnet, shook the snow off and handed it to her. ‘Soggy ribbons, I’m afraid.’

She left them dangling as she took his arm and they retraced their steps through the shrubbery and on to the lawn. Miri had the parts for her family of five snow people and Giles helped her lift the heads into place.

What had happened just then was what she had wanted, surely? The experience of an attractive man’s kiss. She should treat it as a test, to establish whether her secret yearning for a lover was a foolish daydream or something that she truly desired. Because a lover would be so much better than a husband. You could dismiss a lover when you tired of him or he proved not to be the man you had hoped. A lover would not control her money, have no claim on her beyond what she granted him in her bed. A lover would give her pleasure, but would not take her power.

‘We are just going to get some things,’ Miri called. ‘We won’t be long.’

But have I power? How does a woman wield it in this cold country? In India she bought and sold, bargained, traded. Humphrey had believed that all she was doing was carrying out his orders, and, as far as his business was concerned, that was just what she did. No more, no less.

But she had learned how to run a business, had created her own and it had flourished. She had absorbed everything a seventeen-year-old youth might be sent to India to learn in order to return home to England a nabob, rich enough to buy a county. Once she had saved enough money from her housekeeping allowance it had been easy to trade on her own account, to invest in gemstones and gold for herself until she had believed that having such wealth was all she needed to be free, to control her own life. But in London it seemed that she must be a man to play by their rules, to wield the power that money gave.

Perhaps, she mused, as she gathered twigs to make the snow family’s arms, a woman could make her own rules. But I never learned to be a woman. Julia looked down at what she was holding and found her cold lips were curving into a smile. But I can play again, just for a while.

Giles and Miri returned, his arms full of straw and battered old hats, her hands heaped with small lumps of coal and a bunch of wizened carrots. They laughed and joked as they began to dress the snow figures, Miri measuring carrots against Giles’s nose to get the length right for the male figure, him teasing her by sticking handfuls of straw for hair under the female’s hat just when she had adjusted it to her satisfaction.

How long had it been since she had been able to play with as little inhibition, with almost childlike joy? Julia began to break off lengths of fir needles, just long enough to make bristly eyebrows for the snowman, then used more pieces to create ludicrous eyelashes for the snowwoman, stepped back to admire the effect and found she was laughing, too.

Giles came to her side. ‘We have done a fine job with our snow family. Just one more adjustment.’ He took hold of the twiggy arms, tipped some up, some down and there they stood, Mama and Papa Snow holding hands and, on either side, their arms sloped down to take the little twigs the snow children held up. ‘There. A happy family.’

A robin flew down, perched for a moment on the snowman’s old beaver hat, then flew off, its breast a flash of fire in the air. Julia scrubbed at her eyes with the back of her gloved hand. That had been the last time she had played and laughed uninhibitedly, as a child. That Christmas when she had been eleven. The December before Mama died. Papa had never been the same after that.

I want children. I want to share this with them. Simple pleasures, joy that money cannot buy, pleasure without calculation.