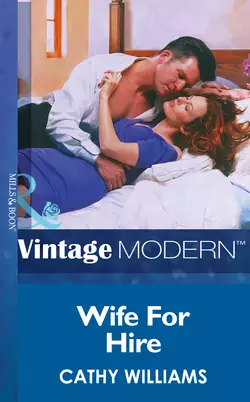

Wife For Hire

Кэтти Уильямс

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Nicholas Knight was a formidably powerful and attractive man, and he had a very tempting proposal for Rebecca Ryan: he wanted to move her into his luxury home, to share his life… and his bed?Rebecca had known and fantasized about Nicholas as a teenager– so did he recognize her, or was he playing games? All Rebecca knew was that she′d never forget the hot passion he′d once aroused in her. Now she just had to find out if it was really her Nicholas wanted, or just a convenient wife!