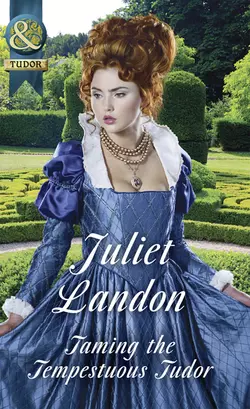

Taming The Tempestuous Tudor

Juliet Landon

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Passion and peril in the court of Elizabeth I…Henrietta Raemon, illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII, longs to go to court to be closer to her half-sister, the Queen. Fiercely independent, the last thing on Etta’s mind is marriage – until newly ennobled merchant Baron Somerville leaves her no choice!But the attractions of court turn perilous when Etta’s resemblance to Elizabeth makes her some powerful enemies. Her husband is there to protect her, if only Etta can conquer her pride…and surrender!