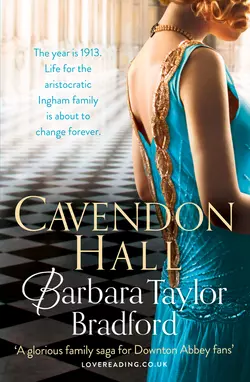

Cavendon Hall

Barbara Taylor Bradford

A sweeping saga set around the aristocratic Ingham family of Cavendon Hall and the Swanns who serve them, set on the eve of World War 1.Two entwined families: the aristocratic Inghams and the Swanns who serve themOne stately home: Cavendon Hall, a grand imposing house nestled in the beautiful Yorkshire DalesA society beauty: Lady Daphne Ingham is the most beautiful of the Earl’s daugthers. Being presented at Court and then a glittering marriage is her destiny.But in the summer of 1913, a devastating event changes her future forever, and puts the House of Ingham at risk. Life as the families of Cavendon Hall know it – Royal Ascot, supper dances, grouse season feasts – is about to alter beyond recognition as the storm clouds of war gather.

Copyright (#ulink_7308568b-14ef-5ab9-9660-436beb6f6777)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Barbara Taylor Bradford 2014

Cover photographs © Ilena Simeonova/Trevillion Images (woman); Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (interior)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Barbara Taylor Bradford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007503209

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780007503193

Version: 2017-10-25

Dedication (#ulink_0a1f30e5-3264-572d-851b-96a6a4574d0c)

For Bob, with all my love always

CONTENTS

Cover (#u0dff62b7-9ea6-5021-9412-fe9177ce2a8f)

Title Page (#ufed80d9b-051a-59b5-929c-c7128497f74c)

Copyright (#ud1abadc6-6b6b-5cef-ad07-6a5010f67b76)

Dedication (#ue1b9c7a0-9118-586a-9503-0074ee9bb312)

Characters (#u941f499f-ba92-5e9e-adf9-6d7960d96510)

Part One: The Beautiful Girls of Cavendon May 1913 (#u834c54ac-c255-5f04-8d9a-ddd11a6dbe42)

Chapter One (#u9ddf1373-536f-522d-a378-148fb3072c10)

Chapter Two (#ub47893b8-44d2-5e90-9bf2-5a75bf6df63b)

Chapter Three (#u469da4e0-4ce6-58cc-8e17-61f0a77fbc1d)

Chapter Four (#u56c2ce00-76a3-56df-8bb7-a8d64de435c1)

Chapter Five (#u16344cf3-e381-50c0-90ca-ee5f9d1e841e)

Chapter Six (#u7a3ea310-efec-5729-891b-e80b92a08f09)

Chapter Seven (#ua53cdaed-efbe-5a7b-a5e9-d7d01f726e9e)

Chapter Eight (#u29968edc-0121-5b49-aec3-284c64f7680f)

Chapter Nine (#u0356c42a-475d-5f97-8c6a-75e01070d2da)

Chapter Ten (#u1be98356-f127-52c0-b9c7-2d2e5389efff)

Chapter Eleven (#ude0c8006-a989-5c06-8758-e3414ae132cb)

Chapter Twelve (#uba61e471-7351-5058-8835-6c847ac93895)

Chapter Thirteen (#u70b1a97d-291e-57d5-966d-01e1a348a231)

Chapter Fourteen (#ub40bc7e7-5cdd-50a4-835b-81eef3b345d3)

Part Two: The Last Summer July–September 1913 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: Frost on Glass January 1914–January 1915 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: River of Blood May 1916–November 1918 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Five: A Matter of Choice September 1920 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Barbara Taylor Bradford (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHARACTERS (#ulink_701c5391-9e19-5232-bbdb-2871437690b9)

ABOVE THE STAIRS

THE INGHAMS IN 1913

Charles Ingham, 6th Earl of Mowbray, aged 44. Owner and custodian of Cavendon Hall. Referred to as Lord Mowbray.

Felicity Ingham, his wife, the Countess of Mowbray, aged 43. An heiress in her own right through her late father, an industrialist. Addressed as Lady Mowbray.

THEIR CHILDREN

Guy Ingham, the heir to the earldom, aged 22. Attending Oxford University. He has the title of the Honourable Guy Ingham.

Miles Ingham, the second son, aged 14, attending Eton College. He is known as the Honourable Miles Ingham.

Lady Diedre Ingham, eldest daughter, aged 20, living at home.

Lady Daphne Ingham, second daughter, aged 17, living at home.

Lady DeLacy Ingham, third daughter, aged 12, living at home.

Lady Dulcie Ingham, fourth daughter, aged 5, the baby of the family, in care of the nanny.

The four girls are referred to affectionately as the four Dees by the staff.

OTHER INGHAMS

Lady Lavinia Ingham Lawson, married sister of the Earl, aged 40. She lives at Skelldale House, on the estate, when in Yorkshire. She is mostly in London. She is married to John Edward Lawson, known as Jack. He is a business tycoon.

Lady Vanessa Ingham, the spinster sister of the Earl, aged 34, who has her own private suite of rooms at Cavendon, which she uses when in Yorkshire. She spends most of her time in London.

Lady Gwendolyn Ingham Baildon, the widowed aunt of the Earl, aged 72, who resides at Little Skell Manor on the estate. She was married to the late Paul Baildon.

The Honourable Hugo Ingham Stanton, first cousin of the Earl, aged 32. He is the nephew of Lady Gwendolyn, the sister of his late mother, Lady Evelyne Ingham Stanton. He has been living abroad for years. His father was the late Ian Stanton, a racehorse breeder and owner.

BETWEEN STAIRS

THE SECOND FAMILY: THE SWANNS

The Swann family has been in service to the Ingham family for over one hundred and sixty years. Consequently, their lives have been intertwined in many different ways. Generations of Swanns have lived in Little Skell village, adjoining Cavendon Park, and still do. The present-day Swanns are as devoted and loyal to the Inghams as their forebears were, and would defend any member of the family with their lives. The Inghams trust them implicitly, and vice versa.

THE SWANNS IN 1913

Walter Swann, valet to the Earl, aged 35. Head of the Swann family.

Alice Swann, his wife, aged 32. A clever seamstress who takes care of the Countess’s clothes and makes outfits and frocks for the daughters.

Harry, son, aged 15. An apprentice landscape gardener at Cavendon Hall.

Cecily, daughter, aged 12, who is allowed to attend lessons at Cavendon Hall with DeLacy.

OTHER SWANNS

Percy, younger brother of Walter, aged 32. Head gamekeeper at Cavendon.

Edna, wife of Percy, aged 33. Does occasional work at Cavendon.

Joe, their son, aged 12. Works at Cavendon as a junior woodsman.

Bill, first cousin of Walter, aged 27. Head landscape gardener at Cavendon. He is unmarried.

Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 38. Head of interior maintenance and carpentry at Cavendon. Widowed.

Paul, son of Ted, aged 14, apprenticed to his father as a designer.

Eric, brother of Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 33. Butler at the London house of Lord Mowbray. Single.

Laura, sister of Ted, first cousin of Walter, aged 26. Housekeeper at the London house of Lord Mowbray. Single.

Charlotte, aunt of Walter and Percy, aged 45. Retired from service at Cavendon. Charlotte is the matriarch of the Swann family. She is treated with great respect by everyone, and with a certain deference by the Inghams. Charlotte was the secretary and personal assistant to David Ingham, the 5th Earl, until his death. There was some speculation about the true nature of their relationship.

Dorothy Pinkerton, née Swann, cousin of Charlotte and the Swanns. She lives in London and is married to Howard Pinkerton, a Scotland Yard detective.

CHARACTERS BELOW STAIRS

Mr Henry Hanson, Butler

Mrs Agnes Thwaites, Housekeeper

Mrs Nell Jackson, Cook

Miss Olive Wilson, Lady’s maid to the Countess

Mr Malcolm Smith, Head footman

Mr Gordon Lane, Second footman

Miss Elsie Roland, Head housemaid

Miss Mary Ince, Second housemaid

Miss Peggy Swift, Third housemaid

Miss Polly Wren, Kitchen maid

Mr Stanley Gregg, Chauffeur

OTHER EMPLOYEES

Miss Maureen Carlton, the nanny, usually addressed as Nanny or Nan.

Miss Audrey Payne, the governess, usually addressed as Miss Payne. The governess is not at Cavendon in the summer. The children are not in school.

THE OUTDOOR WORKERS

A great stately home such as Cavendon Hall, with thousands of acres of land, and a huge grouse moor, employs many local people. This is its purpose for being, as well as providing a private home for a great family. It offers employment to the local villagers, and also land for local tenant farmers. The villages surrounding Cavendon were built by various earls of Mowbray to provide housing for their workers; churches and schools were also built, as well as post offices and small shops at later dates. The villages around Cavendon are Little Skell, Mowbray and High Clough.

There are a great number of outside workers: a head gamekeeper and five additional gamekeepers; beaters and flankers who work when the grouse season starts. Other outdoor workers include woodsmen, who take care of the surrounding woods for shooting in the lowlands at certain times of the year. The gardens are cared for by a head landscape gardener, and five other gardeners working under him.

The grouse season starts in August, on the Glorious Twelfth, as it is called. It finishes in December. The partridge season begins in September. Duck and wild fowl are shot at this time. Pheasant shooting starts on 1 November and goes on until December. The men who come to shoot at Cavendon are usually aristocrats, and always referred to as the Guns, i.e., the men using the gun.

PART ONE (#ulink_ee1f84c1-4cc0-586c-bba8-66bc3c22ffe4)

The Beautiful Girls of Cavendon May 1913 (#ulink_ee1f84c1-4cc0-586c-bba8-66bc3c22ffe4)

She is beautiful and therefore to be woo’d;

She is a woman, therefore to be won.

William Shakespeare

Honor women: They wreathe and weave

Heavenly roses into earthly life.

Johann von Schiller

Man is the hunter; woman is his game.

Alfred Tennyson

ONE (#ulink_6a780ea7-d324-53b8-9e75-d0c8a53ce4d5)

Cecily Swann was excited. She had been given a special task to do by her mother, and she couldn’t wait to start. She hurried along the dirt path, walking towards Cavendon Hall, all sorts of ideas running through her active young mind. She was going to examine some beautiful dresses, looking for flaws; it was an important task, her mother had explained, and only she could do it.

She did not want to be late, and increased her pace. She had been told to be there at ten o’clock sharp, and ten o’clock it would be.

Her mother, Alice Swann, often pointed out that punctuality might easily be her middle name, and this was always said with a degree of admiration. Alice took great pride in her daughter, and was aware of certain unique talents she possessed.

Although Cecily was only twelve, she seemed much older in some ways, and capable, with an unusual sense of responsibility. Everyone considered her to be rather grown up, more so than most girls of her age, and reliable.

Lifting her eyes, Cecily looked up the slope ahead of her. Towering on top of the hill was Cavendon, one of the greatest stately homes in England and something of a masterpiece.

After Humphrey Ingham, the 1st Earl of Mowbray, had purchased thousands of acres in the Yorkshire Dales, he had commissioned two extraordinary architects to design the house: John Carr of York, and the famous Robert Adam.

It was finished in 1761. Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown then created the landscaped gardens, which were ornate and beautiful, and had remained intact to this day. Close to the house was a manmade ornamental lake, and there were water gardens at the back of the house.

Cecily had been going to the hall since she was a small child, and to her it was the most beautiful place in the world. She knew every inch of it, as did her father, Walter Swann. Her father was valet to the Earl, just as his father had been before him, and his great-uncle Henry before that.

The Swanns of Little Skell village had been working at the big house for over one hundred and sixty years, generations of them, ever since the days of the 1st Earl in the eighteenth century. The two families were closely intertwined and bound together; the Swanns had many privileges, and were exceedingly loyal to the Inghams. Walter always said he’d take a bullet for the Earl, and meant it sincerely.

Hurrying along, preoccupied with her thoughts, Cecily was suddenly startled and stopped abruptly. A figure had jumped out onto the path in front of her, giving her a shock. Then she saw at once that it was the young gypsy woman called Genevra, who often lurked around these parts.

The Romany stood in the middle of the path, grinning hugely, her hands on her hips, her dark eyes sparkling.

‘You shouldn’t have done that!’ Cecily exclaimed, stepping sideways swiftly. ‘You startled me. Where did you spring from, Genevra?’

‘Yonder,’ the gypsy answered, waving her arm towards the long meadow. ‘I see yer coming, liddle Cecily. I wus behind t’wall.’

‘I have to get on. I don’t want to be late,’ Cecily said in a cool, dismissive voice. She tried to step around the young woman without success.

The gypsy dodged about, blocked her way, muttering, ‘Aye. Yer bound for that owld ’ouse up yonder. Gimme yer ’and and I’ll tell yer fortune.’

‘I can’t cross your palm with silver, I don’t even have a ha’penny,’ Cecily said.

‘I doan want yer money, and I’ve no need to see yer ’and, I knows all about yer.’

Cecily frowned. ‘I don’t understand …’ She let her voice drift off, impatient to be on her way, not wanting to waste any more time with the gypsy.

Genevra was silent, but she threw Cecily a curious look, then turned, stared up at Cavendon. Its many windows were glittering and the pale stone walls shone like polished marble in the clear northern light on this bright May morning. In fact, the entire house appeared to have a sheen.

The Romany knew this was an illusion created by the sunlight. Still, Cavendon did have a special aura about it. She had always been aware of that. For a moment she remained standing perfectly still, lost in thought, gazing at Cavendon … she had the gift, the gift of sight. And she saw the future. Not wanting to be burdened with this sudden knowledge, she closed her eyes, shutting it all out.

Eventually the gypsy swung back to face Cecily, blinking in the light. She stared at the twelve-year-old for the longest moment, her eyes narrowing, her expression serious.

Cecily was acutely aware of the gypsy’s fixed scrutiny, and said, ‘Why are you looking at me like that? What’s the matter?’

‘Nowt,’ the gypsy muttered. ‘Nowt’s wrong, liddle Cecily.’ Genevra bent down, picked up a long twig, began to scratch in the dirt. She drew a square, and then above the square she made the shape of a bird, then glanced at Cecily pointedly.

‘What do they mean?’ the child asked.

‘Nowt.’ Genevra threw the twig down, her black eyes soulful. And in a flash, her strange, enigmatic mood vanished. She began to laugh, and danced across towards the dry-stone wall.

Placing both hands on the wall, she threw her legs up in the air, cartwheeled over it and landed on her feet in the field beyond.

After she had adjusted the red bandana tied around her dark curls, she skipped down the long meadow and disappeared behind a copse of trees. Her laughter echoed across the stillness of the fields, even though she was no longer in sight.

Cecily shook her head, baffled by the gypsy’s odd behaviour, and bit her lip. Then she quickly scuffled her feet in the dirt, obliterating the gypsy’s symbols, and continued up the slope.

She’s always been strange, Cecily muttered under her breath, as she walked on. She knew that Genevra lived with her family in one of the two painted Romany wagons, which stood on the far side of the bluebell woods, way beyond the long meadow. She also knew that the Romany tribe was not trespassing.

It was the Earl of Mowbray’s land where they were camped, and he had given them permission to stay there in the warm weather. They always vanished in the winter months; where they went, nobody knew.

The Romany family had been coming to Cavendon for a long time. It was Miles who had told her that. He was the Earl’s second son, had confided that he didn’t know why his father was so nice to the gypsies. Miles was fourteen; he and his sister DeLacy were her best friends.

The dirt path through the fields led directly from Little Skell village to the back yard of Cavendon Hall. Cecily was running across the cobblestones of the yard when the clock in the stable-block tower began to strike the hour. It was exactly ten o’clock and she was not late.

Cook’s cheerful Yorkshire voice was echoing through the back door as Cecily stood for a moment, catching her breath, and listening.

‘Don’t stand there gawping like a sucking duck, Polly,’ Cook was exclaiming to the kitchen maid. ‘And for goodness’ sake, push the metal spoon into the flour jar before you add the lid. Otherwise we’re bound to get weevils in the flour!’

‘Yes, Cook,’ Polly muttered.

Cecily smiled to herself. She knew the reprimand didn’t mean much. Her father said Cook’s bark was worse than her bite, and this was true. Cook was a good soul, motherly at heart.

Turning the door-knob, Cecily went into the kitchen, to be greeted by great wafts of steam, warm air, and the most delicious smells emanating from the bubbling pans. Cook was already preparing lunch for the family.

Swinging around at the sound of the door opening, Cook smiled broadly when she saw Cecily entering her domain. ‘Hello, luv,’ she said in a welcoming way. Everyone knew that Cecily was her favourite; she made no bones about that.

‘Good morning, Mrs Jackson,’ Cecily answered and glanced at the kitchen maid. ‘Hello, Polly.’

Polly nodded, and retreated into a corner, as usual shy and awkward when addressed by Cecily.

‘Mam sent me to help with the frocks for Lady Daphne,’ Cecily explained.

‘Aye, I knows that. So go on then, luv, get along with yer. Lady DeLacy is waiting upstairs for yer. I understand she’s going to be yer assistant.’ As she spoke, Cook chuckled and winked at Cecily conspiratorially.

Cecily laughed. ‘Mam will be here about eleven.’

The cook nodded. ‘Yer’ll both be having lunch down here with us. And yer father. A special treat.’

‘That’ll be nice, Mrs Jackson.’ Cecily continued across the kitchen, heading for the back stairs that led to the upper floors of the great house.

Nell Jackson watched her go, her eyes narrowing slightly. The twelve-year-old girl was lovely. Suddenly, she saw in that innocent young face the woman she would become. A real beauty. And a true Swann. No mistaking where she came from, with those high cheekbones, ivory complexion and the lavender eyes … Pale, smoky, bluish-grey eyes. The Swann trademark. And then there was that abundant hair. Thick, luxuriant, russet-brown, shot through with reddish lights. She’ll be the spitting image of Charlotte when she grows up, Cook thought, and sighed to herself. What a wasted life she’d had, Charlotte Swann. She could have gone far, no two ways about that. I hope the girl doesn’t stay here, like her aunt did, Nell now thought, turning around, stirring one of her pots. Run, Cecily, run. Run for your life. And don’t look back. Save yourself.

TWO (#ulink_e5cbee10-0c76-5574-a1fa-088c293e6316)

The library at Cavendon was a beautifully proportioned room. It had two walls of high-soaring mahogany bookshelves, reaching up to meet a gilded coffered ceiling painted with flora and fauna in brilliant colours. A series of tall windows faced the long terrace that stretched the length of the house. At each end of the window wall were French doors.

Even though it was May, and a sunny day, there was a fire burning in the grate, as there usually was all year round. Charles Ingham, the 6th Earl of Mowbray, was merely following the custom set by his grandfather and father before him. Both men had insisted on a fire in the room, whatever the weather. Charles fully understood why. The library was the coldest room at Cavendon, even in the summer months, and this was a peculiarity no one had ever been able to fathom.

This morning, as he came into the library and walked directly towards the fireplace, he noticed that a George Stubbs painting of a horse was slightly lopsided. He went over to straighten it. Then he picked up the poker and jabbed at the logs in the grate. Sparks flew upwards, the logs crackled, and after jabbing hard at them once more, he returned the poker to the stand.

Charles stood for a moment in front of the fire, his hand resting on the mantelpiece, caught up in his thoughts. His wife Felicity had just left to visit her sister in Harrogate, and he wondered again why he had not insisted on accompanying her. Because she didn’t want you to go, an internal voice reminded him. Accept that.

Felicity had taken their eldest daughter Diedre with her. ‘Anne will be more at ease, Charles. If you come, she will feel obliged to entertain you properly, and that will be an effort for her,’ Felicity had explained at breakfast.

He had given in to her, as he so often did these days. But then his wife always made sense. He sighed to himself, his thoughts focused on his sister-in-law. She had been ill for some time, and they had been worried about her; seemingly she had good news to impart today, and had invited her sister to lunch to share it.

Turning away from the fireplace, Charles walked across the Persian carpet, making for the antique Georgian partners’ desk, and sat down in the chair behind it.

Thoughts of Anne’s illness lingered, and then he reminded himself how practical and down-to-earth Diedre was. This was reassuring. It struck him that at twenty Diedre was probably the most sensible of his children. Guy, his heir, was twenty-two, and a relatively reliable young man, but unfortunately he had a wild streak that sometimes reared up. It worried Charles.

Miles, of course, was the brains in the family; he had something of an intellectual bent, even though he was only fourteen, and artistic. He never worried about Miles. He was utterly loyal: true blue.

And then there were his other three daughters. Daphne, at seventeen, the great beauty of the family. A pure English rose, with looks to break any man’s heart. He had grand ambitions for his Daphne. He would arrange a great marriage for her. A duke’s son, nothing less.

Her sister DeLacy was the most fun, if he was truthful; quite a mischievous twelve-year-old. Charles was aware she had to grow up a bit, and unexpectedly a warm smile touched his mouth. DeLacy always managed to make him laugh, and entertained him with her comical antics. His last child, five-year-old Dulcie, was adorable; much to his astonishment, she was already a person in her own right, with a mind of her own.

Lucky, I’ve been lucky, he thought, reaching for the morning’s post. Six lovely children, all of them quite extraordinary in their own way. I have been blessed, he reminded himself. Truly blessed with my wife and this admirable family we’ve created. I am the most fortunate of men.

As he shuffled through the post, one envelope in particular caught his eye. It was postmarked Zurich, Switzerland. Puzzled, he slit the envelope with a silver opener, and took out the letter.

When he glanced at the signature, Charles was taken aback. The letter had been written by his first cousin, Hugo Ingham Stanton. He hadn’t heard from Hugo since he had left Cavendon at sixteen, although Hugo’s father had told Charles his son had fared well in the world. He had often wondered about what had become of Hugo. No doubt he was about to find out now.

April 26th, 1913

Zurich

My dear Charles,

I am sure that you will be surprised to receive this letter from me after all these years. However, because I left Cavendon in the most peculiar circumstances, and at such odds with my mother, I decided it would be better if I cut all contact with the family at that time. Hence my long silence.

I continued to see my father until the day he died. No one else wrote to me in New York, and I therefore did not have the heart to put pen to paper. And so years have passed without contact.

I will not bore you with a long résumé of my life for the past sixteen years. Suffice it to say that I did well, and I was particularly lucky that Father sent me to his friend, Benjamin Silver. I became an apprentice in Mr Silver’s real-estate company in New York. He was a good man, and brilliant. He taught me everything there was to learn about the real-estate business, and, I might add, he taught me well.

I acquired invaluable knowledge, and, much to my own surprise, I was a success. When I was twenty-two I married Mr Silver’s daughter, Loretta. We had a very happy union for nine years, but sadly there were no children. Always fragile in health, Loretta died here in Zurich a year ago, much to my sorrow and distress. For the past year, since her passing, I have continued to live in Zurich. However, loneliness has finally overtaken me, and I have a longing to come back to the country of my birth. And so I have now made the decision to return to England.

I wish to reside in Yorkshire on a permanent basis. For this reason I would like to pay you a visit, and sincerely hope that you will receive me cordially at Cavendon. There are many things I wish to discuss with you, and most especially the property I own in Yorkshire.

I am planning to travel to London in June, where I shall take up residence at Claridge’s Hotel. Hopefully I can visit you in July, on a date that is convenient to you.

I look forward to hearing from you in the not-too-distant future. With all good wishes to you and Felicity.

Sincerely, your Cousin,

Hugo

Charles leaned back in the chair, still holding the letter in his hand. Finally, he placed it on the desk, and closed his eyes for a moment, thinking of Little Skell Manor, the house which had belonged to Hugo’s mother, and which he now owned. No doubt Hugo wanted to take possession of it, which was his legal right.

A small groan escaped him, and Charles opened his eyes and sat up in the chair. No use turning away from the worries flooding through him. The house was Hugo’s property. The problem was that their aunt, Lady Gwendolyn Ingham Baildon, resided there, and at seventy-two years old she would dig her feet in if Hugo endeavoured to turf her out.

The mere thought of his aunt and Hugo doing battle sent an icy chill running through Charles, and his mind began to race as he sought a solution to this difficult situation.

Finally he rose, walked over to the French doors opposite his desk, and stood looking out at the terrace, wishing Felicity were here. He needed somebody to talk to about this problem. Right away.

Then he saw her, hurrying down the steps, making for the wide gravel path that led to Skelldale House. Charlotte Swann. The very person who could help him. Of course she could.

Without giving it another thought, Charles stepped out onto the terrace. ‘Charlotte!’ he called. ‘Charlotte! Come back!’

On hearing her name, Charlotte instantly turned around, her face filling with a smile when she saw him. ‘Hello,’ she responded, lifting her hand in a wave. As she did this she began to walk back up the terrace steps. ‘Whatever is it?’ she asked when she came to a stop in front of him. Staring up into his face, she said, ‘You look very upset … is something wrong?’

‘Probably,’ he replied. ‘Could you spare me a few minutes? I need to show you something, and to discuss a family matter. If you have time, if it’s not inconvenient now. I could—’

‘Oh Charlie, come on, don’t be silly. Of course it’s not inconvenient. I was only going to Skelldale House to get a frock for Lavinia. She wants me to send it to London for her.’

‘That’s a relief. I’m afraid I have a bit of a dilemma.’ Taking her arm, he led her into the library, continuing, ‘What I mean is, something has happened that might become a dilemma. Or even a battle royal.’

THREE (#ulink_d396fbba-90f3-5b10-89c7-ae4b0071d187)

When they were alone together, there was an easy familiarity between Charles Ingham and Charlotte Swann.

This unselfconscious acceptance of each other sprang from their childhood friendship, and a deeply ingrained loyalty that had remained intact over the years.

Charlotte had grown up with Charles and his two younger sisters, Lavinia and Vanessa, and had been educated with them by the governess who was in charge of the schoolroom at Cavendon Hall at that time.

This was one of the privileges bestowed on the Swanns over a hundred years earlier, by the 3rd Earl of Mowbray: A Swann girl was invited to join the Ingham children for daily lessons. The 3rd Earl, a kind and charitable man, respected the Swanns, appreciated their dedication and loyalty to the Inghams through the generations, and it was his way of rewarding them. The custom had continued up to this very day, and it was now Cecily Swann who went to the schoolroom with DeLacy Ingham for their lessons with Miss Audrey Payne, the governess.

When they were little, Charlotte and Charles had enjoyed irking his sisters by calling each other Charlie, chortling at the confusion this created. They had been inseparable until he had gone off to Eton. Nevertheless, their loyalty and concern for each other had lasted over the years, albeit in a slightly different way. They didn’t mingle or socialize once Charles had gone to Oxford, and, in fact, they lived in entirely different worlds. When they were with his family, or other people, they addressed each other formally, and were respectful.

But it existed still, that childhood bond, and they were both aware of their closeness, although it was never referred to. He had never forgotten how she had mothered him, looked out for him when they were small. She was only one year older than he was, but it was Charlotte who took charge of them all.

She had comforted him and his sisters when their mother had suddenly and unexpectedly died of a heart attack; commiserated with them when, two years later, their father had remarried. The new Countess was the Honourable Harriette Storm, and they all detested her. The woman was snobbish, brash and bossy, and had a mean streak. She had trapped the grief-stricken Earl, who was lonely and lost, with her unique beauty, which Charlotte loved to point out was only skin deep, after all.

They had enjoyed playing tricks on her, the worse the better, and it was Charlotte who had come up with a variety of names for her: Bad Weather, Hurricane Harriette and Rainy Day, to name just three of them. The names made them laugh, had helped them to move on from the rather childish pranks they played. Eventually they simply poked fun at her behind her back.

The marriage had been abysmal for the Earl, who had retreated behind a carapace of his own making. And it had not lasted long. Hateful Harriette soon returned to London. It was there that she died, not long after her departure from Cavendon. Her liver failed because it had been totally destroyed by the huge quantities of alcohol she had consumed since her debutante days.

Charles suddenly thought of the recent past as he stood watching Charlotte straightening the horse painting by George Stubbs, remembering how often she had done this when she had worked for his father.

With a laugh, he said, ‘I just did the same thing a short while ago. That painting’s constantly slipping, but then I don’t need to tell you that.’

Charlotte swung around. ‘It’s been re-hung numerous times, as you well know. I’ll ask Mr Hanson for an old wine cork again, and fix it properly.’

‘How can a wine cork do that?’ he asked, puzzled.

Walking over to join him, she explained, ‘I cut a slice of the cork off and wedge it between the wall and the bottom of the frame. A bit of cork always holds the painting steady. I’ve been doing it for years.’

Charles merely nodded, thinking of all the bits of cork he had been picking up and throwing away for years. Now he knew what they had been for.

Motioning to the chair on the other side of the desk, he said, ‘Please sit down, Charlotte, I need your advice.’

She did as he asked, and glanced at him as he sat down himself, thinking that he was looking well. He was forty-four, but he didn’t look it. Charles was athletic, as his father had been, and kept himself in shape. Like most of the Ingham men, he was tall, attractive, had their clear blue eyes, a fair complexion and light brown hair. Wherever he went in the world, she was certain nobody would mistake him for being anything but an Englishman. And an English gentleman at that. He was refined looking, had a classy air about him, and handled himself with a certain decorum.

Leaning across the desk, Charles handed Charlotte the letter from Hugo. ‘I received this in the morning post and, I have to admit, it genuinely startled me.’

She took the letter from him, wondering who had sent it. Charlotte had a quick mind, was intelligent and astute. And having worked as the 5th Earl’s personal assistant for years, there wasn’t much she didn’t know about Cavendon, and everybody associated with it. She was not at all surprised when she saw Hugo’s signature; she had long harboured the thought that this particular young man would show up at Cavendon one day.

After reading the letter quickly, she said, ‘You think he’s coming back to claim Little Skell Manor, don’t you?’

‘Of course. What else?’

Charlotte nodded in agreement, and then frowned, and pursed her lips. ‘But surely Cavendon is full of unhappy memories for him?’

‘I would think that’s so; on the other hand, as you’ve seen, Hugo says in his letter that he wishes to discuss the property he owns here, and also informs me that he plans to live in Yorkshire permanently.’

‘At Little Skell Manor. And perhaps he doesn’t care that he will have to turn an old lady out of the house she has lived in for donkey’s years, long before his parents died, in fact.’

‘Quite frankly, I don’t know. I haven’t laid eyes on him for sixteen years. Since he was sixteen, actually. However, he must be fully aware that our aunt still lives there.’ Charles threw her a questioning look, raising a brow.

‘It’s quite easy to check on this well-known family, even long-distance,’ Charlotte asserted. Sitting back in the chair, she was thoughtful for a moment. ‘I remember Hugo. He was a nice boy. But he might well have changed, in view of what happened to him here. He was treated badly. You must recall how angry your father was when his sister sent Hugo off to America.’

‘I do,’ Charles replied. ‘My father thought it was ridiculous. He didn’t believe Hugo caused Peter’s death. Peter had always been a risk-taker, foolhardy. To go out on the lake here, in a little boat, late at night when he was drunk, was totally irresponsible. My father always said Hugo tried to rescue his brother, to save him, and then got blamed for his death.’

‘We mustn’t forget that Peter was Lady Evelyne’s favourite. Your aunt never paid much attention to Hugo. It was sad. A tragic affair, really.’

Charles leaned forward, resting his elbows on the desk. ‘You know how much I trust your judgement. So tell me this – what am I going to do? There will be an unholy row, a scandal, if Hugo does take back the manor. Which of course he can, legally. What happens to Aunt Gwendolyn? Where would she live? With us here in the East Wing? That’s the only solution I can come up with.’

Charlotte shook her head vehemently. ‘No, no, that’s not a solution! It would be very crowded with you and Felicity, and six children, and your sister Vanessa. Then there’s the nanny, the governess, and all the staff. It would be like … well … a hotel. At least to Lady Gwendolyn it would. She’s an old lady, set in her ways, independent, used to running everything. By that I mean her own household, with her own staff. And she’s fond of her privacy.’

‘Possibly you’re right,’ Charles muttered. ‘She’d be aghast.’

Charlotte went on, ‘Your aunt would feel like … a guest here, an intrusion. And I believe she would resent being bundled in here with you, with all due respect, Charles. In fact, she’ll put up a real fight, I fear, because she’ll be most unhappy to leave her house.’

‘It isn’t hers,’ Charles said softly. ‘Pity her sister Evelyne never changed her will. My aunt will have to move. There’s no way around that.’ He sat back in the chair, a gloomy expression settling on his face. ‘I do wish Cousin Hugo wasn’t planning to come back and live here. What a blasted nuisance this is.’

‘I don’t want to make matters worse,’ Charlotte began, ‘but there’s another thing. Don’t—’

‘What are you getting at?’ he interrupted swiftly, alarm surfacing. He sat up straighter in the chair.

‘We know Lady Gwendolyn will be put out, but don’t you think Hugo’s presence on the estate is going to upset some other people as well? There are still those who think Hugo was responsible for Peter’s death, and—’

‘That’s because they don’t know the facts,’ he cut in sharply. ‘Or they won’t accept them.’

Charlotte remained silent, her mind racing.

Getting up from the chair, Charles walked over to the fireplace, stood with his back to it, imagining worrying scenarios. He still thought the only way to deal with this matter easily and in a kindly way was to invite his aunt to live with them. Perhaps Felicity could talk to her. His wife had a rather persuasive manner and much charm.

Charlotte stood up, and joined him near the fireplace. As she approached him she couldn’t help thinking how much he resembled his father in certain ways. He had inherited some of his father’s mannerisms, often sounded like him.

Instantly her mind turned to David Ingham, the 5th Earl of Mowbray. She had worked for him for twenty years, until he had died. Eight years ago now. As those happy days, still so vivid, came into her mind, she thought of the South Wing at Cavendon. It was there they had worked, alongside Mr Harris, the accountant, Mr Nelson, the estate manager, and Maude Greene, the secretary.

‘The South Wing, that’s where Lady Gwendolyn could live!’ Charlotte blurted out as she came to a stop next to Charles.

‘Those rooms Father used as offices? Where you worked?’ he asked, and then a wide smile spread across his face. ‘Charlotte, you’re a genius. Of course she could live there. And very comfortably.’

Charlotte nodded, and hurried on, her enthusiasm growing. ‘Your father put in several bathrooms and a small kitchen, if you remember. When you built the office annexe in the stable block, all of the office furniture was moved over there. The sofas, chairs and drawing-room furniture came down from the attics and into the South Wing.’

‘Exactly. And I know the South Wing is constantly well maintained by Hanson and Mrs Thwaites. Every wing of Cavendon is kept in perfect condition, as you’re aware.’

‘If Lady Gwendolyn agreed, she would have a self-contained flat, in a sense, and total privacy,’ Charlotte pointed out.

‘That’s true, and I would be happy to make as many changes as she wished.’ Taking hold of her arm, he continued, ‘Let’s go and look at those rooms in the South Wing, shall we? You do have time, don’t you?’

‘I do, and that’s a good idea, Charles,’ she responded. ‘Because you have no alternative but to invite Hugo Stanton to visit Cavendon. And I think you must be prepared for the worst. He might well want to take possession of Little Skell Manor immediately.’

His chest tightened at her words, but he knew she was right.

As they moved through the various rooms in the South Wing, and especially those that his father had used as offices, Charles thought of the relationship between his father and Charlotte.

Had there been one?

She had come to work for him when she was a young girl, seventeen, and she had been at the 5th Earl’s side at all times, had travelled with him, and been his close companion as well as his personal assistant. It was Charlotte who had been with his father when he died.

Charles was aware there had been speculation about their relationship, but never any real gossip. No one knew anything. Perhaps this was due to total discretion on his father’s part and Charlotte’s … that there was not a whiff of a scandal about them.

He glanced across at Charlotte. They were in the lavender room, and she was explaining to him that his aunt might like to have it as her bedroom. He was only half listening.

A raft of brilliant spring sunshine was slanting into the room, was turning her russet hair into a burnished helmet around her face. As always, she was pale, and her light greyish-blue eyes appeared enormous. For the first time in years, Charles saw her objectively. And he realized what a beautiful woman she was; she looked half her true age.

Thrown into her company every day for twenty years, how could his father have ever resisted her? Charles Ingham was now positive they had been involved with each other. And on every level.

It was an assumption on his part. There was no evidence. Yet at this moment it had suddenly become patently obvious to him. Charles had grown up with his father and Charlotte, and knew them better than anyone, even better than his wife Felicity, and he certainly knew her very well indeed. And he had had insight into them, had been aware of their flaws and their attributes, dreams and desires; and so he believed, deep in his soul, that it was more than likely they had been lovers.

Charles turned away, realizing he had been staring so hard she had become aware of his penetrating scrutiny. Moving quickly, saying something about the small kitchen, he hurried out of the lavender room into the corridor.

And why does all this matter now? he asked himself. His father was dead. And if Charlotte had made him happy, and eased his burdens, then he was glad. Charles hoped they had loved each other.

But what about Charlotte? How did she feel these days? Did she miss his father? Surely she must. All of a sudden he was filled with concern for her. He wanted to ask her how she felt. But he didn’t dare. It would be an unforgivable intrusion on her privacy, and he had no desire to embarrass her.

FOUR (#ulink_3aaa17c5-5ada-5faf-bff1-6292e6b2049e)

The evening gown lay on a white sheet, on the floor of Lady DeLacy Ingham’s bedroom. DeLacy was the twelve-year-old daughter of the Earl and Countess, and Cecily’s best friend. This morning she was excited, because she had been allowed to help Cecily with the dresses. These had been brought down from the large cedar storage closet in the attics. Some were hanging in the sewing room, awaiting Alice’s inspection; two others were here.

The gown that held their attention was a shimmering column of green, blue and turquoise crystal beads, and to the two young girls kneeling next to it, the dress was the most beautiful thing they had ever seen.

‘Daphne’s going to look lovely in it,’ DeLacy said, staring across at Cecily. ‘Don’t you think so?’

Cecily nodded. ‘My mother wants me to seek out flaws in the dress, such as broken beads, broken threads, any little problems. She needs to know how many repairs it needs.’

‘So that’s what we’ll do,’ DeLacy asserted. ‘Shall I start here? On the neckline and the sleeves?’

‘Yes, that’s a good idea,’ Cecily answered. ‘I’ll examine the hem, which my mother says usually gets damaged by men. By their shoes, I mean. They all step on the hem when they’re dancing.’

DeLacy nodded. ‘Clumsy. That’s what they are,’ she shot back, always quick to speak her mind. She was staring down at the dress, and exclaimed, ‘Look, Ceci, how it shimmers when I touch it.’ She shook the gown lightly. ‘It’s like the sea, like waves, the way it moves. It will match Daphne’s eyes, won’t it? Oh, I do hope she meets a duke’s son when she’s wearing it.’

‘Yes,’ Cecily muttered absently, her head bent as she concentrated on the hemline of the beaded gown. It had been designed and made in Paris by a famous designer, and the Countess had only worn it a few times. Then it had been carefully stored, wrapped in white cotton and placed in a large box. The gown was to be given to Daphne, to wear at one of the special summer parties, once it had been fitted to suit her figure.

‘There’s hardly any damage,’ Cecily announced a few minutes later. ‘How are the sleeves and the neckline?’

‘Almost perfect,’ DeLacy replied. ‘There aren’t many beads missing.’

‘Mam will be pleased.’ Cecily stood up. ‘Let’s put the gown back on the bed.’

She and DeLacy took the beaded evening dress, each of them holding one end, and lifted it carefully onto DeLacy’s bed. ‘Gosh, it’s really heavy,’ she said as they put it back in place.

‘That’s the reason beaded dresses are kept in boxes or drawers,’ Cecily explained. ‘If a beaded gown is put on a hanger, the beads will eventually weigh it down, and that makes the dress longer. It gets out of shape.’

DeLacy nodded, always interested in the things Cecily told her, especially about frocks. She knew a lot about clothes, and DeLacy learned from her all the time.

Cecily straightened the beaded dress and covered it with a long piece of cotton, then walked across the room to look out of the window. She was hoping to see her mother coming from the village. There was no sign of her yet.

DeLacy remained near the bed, now staring down at the other summer evening gown, a froth of white tulle, taffeta and handmade lace. ‘I think I like this one the most,’ she said to Cecily without turning around. ‘This is a real ball gown.’

‘I know. Mam told me your mother wore it only once, and it’s been kept in a cotton bag in the cedar closet for ages. That’s why the white is still white. It hasn’t turned.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘White turns colour. It can become creamy, yellowed, or faded. But the ball gown has been well protected, and it’s as good as new.’

On an impulse, DeLacy reached down, picked up the gown and moved away from the bed. Holding the gown close to her body, she began to dance around the room, whirling and twirling, humming to herself, imagining herself waltzing in a ballroom. The skirt of the gown flared out as she moved.

Cecily couldn’t believe what she was seeing. She was totally speechless, gaping at DeLacy as she continued to swirl and jump with the delicate ball gown in her arms. Cecily was in shock, unable to do anything. She was afraid to grab DeLacy in case the gown was damaged in the process, and so she just stood there cringing, worried about the lace and the tulle. It truly was a ball gown, full-skirted like a crinoline, and it would easily rip if it caught on the furniture.

Finding her voice at last, Cecily exclaimed, ‘Please stop, DeLacy! The fabric could get damaged. It’s so delicate. Please, please put the dress back on the bed!’

Now Cecily took a step forward, moving closer to her friend, who immediately danced away, putting herself out of reach. She continued to clutch the dress to her body. ‘I won’t hurt it, Ceci,’ DeLacy said, still whirling around the room. ‘I promise I won’t.’

‘Stop! You must stop!’ Cecily cried desperately, her voice rising. She was on the verge of tears.

DeLacy Ingham paid no attention to Cecily Swann.

She was enjoying herself too much, dancing around the bedroom, lost in a world of her own for a moment or two. And then it happened. The accident.

Cecily saw it start as if in slow motion, and there was nothing she could do to stop it.

DeLacy’s foot got caught in the hemline of the gown. She wobbled. Then lost her balance. And reached out to steady herself. She grabbed the edge of the desk, still holding the gown. But as she did so, she knocked over the inkpot. It rolled across the desk towards her. She stepped back but she was not fast enough. The bright blue ink splashed onto the front of the skirt of the white lace ball gown.

Cecily gasped out loud, her eyes widening. Horrified at what had just happened, and frightened at the thought of the consequences, she was unable to move.

DeLacy looked down at the ink, her face stricken. When she glanced across at Cecily her eyes filled with tears.

‘Look what you’ve done!’ Cecily said, her voice trembling. ‘Why didn’t you listen to me? Why didn’t you pay attention?’

DeLacy had no answer for her. She stood there holding the dress, tears rolling down her face.

FIVE (#ulink_9e9b68a3-95de-530d-80ad-1bb3ea6b82f5)

‘DeLacy! What on earth’s happened?’ Daphne exclaimed from the threshold of the room, and hurried forward, making straight for her sister.

DeLacy did not answer, quaking inside, knowing how upset Daphne would be when she saw the ruined ball gown. It had been chosen for her to wear at the summer ball their parents gave at Cavendon every year. Tears brimmed, and she swallowed hard, pushing back her fear. She knew she was in trouble. How stupid she had been to play around with this fragile gown.

‘Why are you clutching the ball gown like that? My goodness, is that ink? How did ink get on the lace?’ Daphne’s normally soft voice had risen an octave or two, and she was startled, her face suddenly turning pale.

When DeLacy remained silent, looking more frightened than ever, Daphne turned, her gaze resting on Cecily. ‘What on earth were you doing? How did this happen?’

Cecily, fiercely loyal to her best friend, cleared her throat nervously, not knowing how to answer Daphne without lying. That she could not do; nor did she wish to explain the series of events that had taken place.

Her mind raced as she wondered what to say. Unexpectedly, she did not have to do that, since her mother was now entering the room.

Cecily began to shake inside. She was well aware how angry her mother would be, and she would be blamed. She had been in charge.

Alice walked over to join Daphne and DeLacy. When she spotted the ball gown in DeLacy’s arms she came to an abrupt halt, a dismayed expression crossing her face. Nonetheless, Alice was self-contained, and she said in a steady voice, ‘That’s ruined! It’s of no use to anyone now.’ Glancing at her daughter, she raised a brow. ‘Well, what do you have to say? Can you please explain how this unique ball gown got so damaged?’

Unable to speak, her mouth dry, Cecily shook her head; she retreated, moving away, backing up against the window.

Alice was not to be deterred, and went on, ‘I gave you a task, Cecily. You were instructed to inspect the frocks and the ball gown, which had been taken out of the cedar closet in the attic. I asked you to look after them. They were in your care. However, it is obvious you didn’t look after this one, did you?’

Cecily blinked back the incipient tears. She shook her head, and in a whisper, she said, ‘It was an accident, Mam.’ She was still protecting DeLacy when she added, ‘I’m sorry I let you down.’

Alice simply nodded, holding her annoyance in check. She was usually polite, particularly when she was in the presence of the Inghams. Then it struck her that it was DeLacy who was responsible for this disaster. Before she could direct a question at her, DeLacy stepped forward, drew closer to Alice.

Taking a deep breath, she said in a quavering voice, ‘Don’t blame Ceci, Mrs Alice! Please don’t do that. She’s innocent. It’s my fault, I’m to blame. I picked up the dress, waltzed around the room with it. Then I tripped, lost my balance and knocked over the inkpot …’ She paused, shook her head, and began to weep, adding through her tears, ‘I was silly.’

Alice went over to her. ‘Thank you for telling me, Lady DeLacy, and please, let me take the gown from you. You’re crushing it. Please give it to me, m’lady.’

DeLacy did so, releasing it from her clutches at last. ‘I’m sorry, Mrs Alice. Very sorry,’ she said again.

Alice carried the ball gown over to the bed and laid it down, examining the stains, fully aware how difficult it was to remove ink – virtually impossible, in fact.

At seventeen, Daphne Ingham was a rather unusual girl. She was not only staggeringly beautiful but a kind, thoughtful and compassionate young woman with a tender heart. She stepped over to her sister and put an arm around her. Gently, she said, ‘I understand what happened, Lacy darling, it was an accident, as Ceci said. Mama will understand. These things do happen sometimes, and we all know you didn’t intend to do any harm.’

On hearing these words, and aware of Daphne’s sweet nature, DeLacy clung to her and began to sob. Daphne held her closer, soothing her, not wishing her little sister to be so upset – and over a dress, of all things.

Surprisingly, Lady Daphne Ingham was not particularly vain. She only paid attention to clothes because it had been drilled into her to do so because of her station in life. Also, she knew that her father could easily afford to buy a new dress for her.

After a moment, Daphne drew away. ‘Come on, stop crying, DeLacy. Tears won’t do any good.’ Looking over at Alice, she then said, ‘Can the lace and the underskirts be cleaned, Mrs Swann?’

Alice shook her head vigorously. ‘I don’t believe so, m’lady. Well, not successfully. I suppose I could try using lemon juice, salt, white vinegar …’ She broke off. ‘No, no, they won’t do any good. Ink is awful, you know, it’s like a dye. And talking of ink, it’s all over the desk, m’lady, and on the carpet. Shall I go and find Mrs Thwaites? Ask her to send up one of the maids?’

‘That’s all right. I’ll ring for Peggy, Mrs Swann. She’ll clean up the ink. None of us should go near it. We don’t want it on our hands, not when there are other frocks around.’

‘You’re right, Lady Daphne. I was—’

‘Mam,’ Cecily interrupted. ‘I can make the ball gown right. I can, Mam.’ Cecily turned around, stared intently at her mother, suddenly feeling confident. Her face was flushed with excitement, her eyes sparkling. ‘I’m sure I can save it. And Lady Daphne can wear it to the summer ball after all.’

‘You’ll never get that ink off, Ceci,’ Alice answered, her tone softer, now that she knew her daughter had, in fact, not been responsible for the ruination of the gown.

‘Mam, please, come here, and you too, DeLacy. And you as well, please, Lady Daphne. I want to explain what I can do.’

The three of them immediately joined her, stood looking down at the white lace ball gown stretched across the bottom of the bed.

Cecily said, ‘I’m going to cut away the front part of the white lace skirt from the waist to the hemline. I’ll shape it. Make it a panel that starts out narrow at the waist and widens as it goes down to the floor. I’ll do the same with the white taffeta underskirt, and the tulle. If the second layer of tulle has ink on it, I’ll cut that off too.’

‘And then what?’ Alice asked, gazing at her in bafflement.

‘I’ll replace the panels of lace, taffeta and tulle. It’ll be hard to find white lace to match the ball gown. You might have to go to London.’

In spite of her initial scepticism, Alice suddenly understood exactly what Cecily meant to do. She also realized that her daughter might have the solution. ‘It sounds like a good plan, Cecily, very clever. Unfortunately, you’re right about the lace, it will be difficult to match. I probably will have to go up to London. To Harrods.’

Alice now paused, shook her head. ‘There are several other things we must consider. First, a panel of lace that’s different from the rest of the overskirt would be extremely noticeable. Secondly, there would be seams down the front. They’d be obvious.’

‘I’ve thought of that,’ Cecily answered swiftly. ‘I can hide the seams with narrow ribbon lace, and sew the ribbon lace around the waist as a finishing touch.’ She bit her lip, before adding, ‘Or we can make a new skirt out of new lace.’

‘I understand,’ Alice said. ‘But the new lace wouldn’t match the bodice. And don’t even think of trying to remake the bodice, Cecily, that would be far too difficult for both of us.’

‘We don’t have to touch the bodice, Mam.’

‘I think Cecily is right, Mrs Swann,’ Daphne said. ‘Her ideas are brilliant.’ She gave Cecily a huge smile. ‘I believe you will be a dress designer yourself one day, like Lucile of Hanover Square.’

‘Perhaps,’ Alice said quietly. ‘I’ve always known Cecily had talent, a flair with clothes. And such a good eye.’ Alice suddenly smiled for the first time since entering the room.

Pragmatic by nature, and wishing to continue talking about the ball gown, Cecily now said, ‘The lace will cost a lot, won’t it?’

She had addressed Alice, but before her mother could answer, Daphne said, ‘Oh you mustn’t worry about that, Ceci. I am quite certain you will be able to rescue the gown, and I know Papa will be happy to pay for the lace, and the other fabrics you require.’

Alice carried the ball gown over to Cecily, and gave it to her. She said, ‘We’ll go up to the sewing room now and put this on the mannequin, so that we can examine the stains properly. I’ll bring the beaded gown. It’s heavy.’ Glancing across at Daphne, she said, ‘Will you join us, Your Ladyship? I think you should try on both of the dresses, so we can see how they fit.’

‘I’ll be happy to, I’ll just go to my room and change into a dressing gown.’ Turning to her sister, Daphne added, ‘I shall ring for Peggy, and once she arrives to clean up the ink, you can join us in the sewing room. She can, can’t she, Mrs Alice?’

‘Of course she can, m’lady,’ Alice replied with a friendly smile, and then she and her daughter left DeLacy’s bedroom.

Cecily was relieved her mother was no longer angry with her. How foolish she had been, not trying harder to stop DeLacy, and DeLacy had been irresponsible, dancing around with the gown, the way she had. They should both have known better. After all, they were grown up.

‘I think I’d better get the platform out,’ Alice announced, walking over to the huge storage cupboard in the sewing room, opening the door. ‘It’ll make it easier for me to see the hemline when Lady Daphne stands on it.’

‘I’ll help, Mam.’

Alice shook her head. ‘I have it, love, don’t worry.’ She now upended the square white box she had pulled out, and pushed it across the room to the cheval mirror. Several years ago, Walter Swann had attached two small wheels on one side of the platform so that it would be easy for his wife to move around.

At this moment, the door flew open and Lady Daphne came in wearing a blue silk dressing gown; DeLacy was immediately behind her older sister, creeping in, stealthily, almost as if she did not want to be noticed.

Cecily’s eyes flew to her friend, and she nodded.

DeLacy offered a smile in return, but it was a wan smile at that. The girl looked shamefaced, subdued, and even a little cowed.

Cecily said encouragingly, ‘Let’s go and sit over there, Lacy, on the chairs near the wall.’

DeLacy inclined her head, followed her friend, but remained silent.

‘Here I am, Mrs Swann,’ Daphne said. ‘I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting.’

‘No problem, my lady. If you’ll just slip behind the screen, I’ll bring the beaded gown, help you get into it.’

Cecily felt sorry for DeLacy, and she reached out, took hold of her hand, squeezed it. ‘Mam’s not angry any more,’ she whispered. ‘Cheer up.’

DeLacy swivelled her head, looked at Cecily, and blinked back sudden tears. ‘Are you sure?’ she whispered. ‘She was furious with me. I could tell.’

‘It’s fine, everything’s settled down.’

Within seconds Daphne was standing on the wooden platform in front of the cheval mirror; even she, who so lacked an interest in clothes, was impressed with the way she looked.

The blue, green and turquoise crystal beads, covering the entire dress, shimmered if she made the slightest movement. It was eye-catching, and Daphne knew how well it suited her. Smiling at Alice, her bright blue eyes sparkling, she exclaimed, ‘It undulates; it’s unique.’ She turned slowly on the platform, viewing herself from every angle, obviously taken with the long, slender column of beads and the magical effect they produced.

Alice was happy. The gown fitted this slender beauty as if it had been specially made for her, and also Daphne was finally showing an interest in clothes. Alice also realized how right the Countess had been to choose this particular dress from the collection of her evening gowns and other apparel stored in the cedar closets. It was … wonderful on Daphne. No other word to describe it, but then it was a piece of haute couture from Paris. It had been made for the Countess at Maison Callot, the famous fashion house run by the three talented Callot sisters, who designed stylish clothes for society women.

‘The dress is most becoming on you, Lady Daphne,’ Alice smiled, and went to stand in front of her. Very slowly, she walked around the platform, studying the dress, nodding to herself at times.

‘The hemline dips in a few places; nothing to worry about, m’lady. That often happens with beaded gowns, it’s the weight of the beads. I’ll just put in a few pins where I need to adjust it. It’s a perfect fit, Lady Daphne.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Alice.’

Cecily said, ‘There aren’t many beads missing, Mam.’

Alice swung her head, smiled at her daughter and went on with her work.

Cecily sat back in the chair, watching her mother, always learning from her. Alice was now kneeling on the floor with a small pincushion attached to her left wrist. Every so often she put a pin or two in the hem, marking the exact spot for attention later.

Pins had a language of their own, Cecily was aware of that. It was a language her mother was going to teach her soon. She had made a promise, and her mam always kept her promises.

When Daphne finally got off the platform and walked towards the screen in a corner of the room, Alice beckoned to Cecily, and the two of them took the bouffant white ball gown off the mannequin. Alice followed Daphne, carrying the gown. She was certain this would fit her too. It had been made at the same time as the beaded column.

Daphne emerged a few seconds later, looking so beautiful, so ethereal, in the froth of white lace and tulle, that Cecily caught her breath in surprise. Then she exclaimed, ‘You look like a fairy-tale princess!’

Daphne walked forward, smiling. She swirled around, the skirts billowing out, and then swirled again, and nobody even noticed the ink stains, so entrancing was she.

‘The perfect bride for the son of a duke,’ DeLacy blurted out, and then shrank back in the chair when they all stared at her.

The phantom duke not yet found, Alice thought, and therefore no son to marry. But there will be one soon enough, I’ve no doubt. After all, she’s only seventeen and not quite ready for marriage yet. Still a child in so many ways. And such a beauty. But all of the four Dees are lovely, and so is my Cecily. Yes, they’re the beautiful girls of Cavendon, none to match them anywhere.

Alice stood there smiling, admiring them, and thinking what a lovely summer it was going to be for everyone – the suppers, the dances, the big ball, and the weekend house parties … a happy, festive time.

Although she did not know it, Alice was wrong. The summer would be a season of the most devastating trouble, which would shake the House of Ingham to its core.

SIX (#ulink_de6a5eb3-26fc-51ce-80c8-6ebb002c8633)

‘It’s extremely quiet in here, Mrs Jackson,’ the butler remarked from the doorway of the kitchen, surveying Cook’s domain.

‘Did yer think we’d all died and gone ter heaven then?’ Nell Jackson asked with a laugh. ‘I just sat down ter catch me breath before I start on the main course. Can’t cook it yet, though, not till the last minute. Dover sole is a delicate fish, doesn’t need much time in the pan.’

Mr Hanson nodded and went on. ‘I’ve no doubt the hustle and bustle will start up again very shortly.’

‘It will. Right now everyone’s off doing their duties upstairs, but they’ll soon be scurrying back down here, bringing their bustle with them. As for Polly, I sent her ter bed, Mr Hanson. She’s got a sore throat and a headache. It’s better she’s confined ter her room until she feels better. I don’t want her spreading germs, if she does have a cold.’

‘Good thinking on your part, Mrs Jackson. Lord Mowbray is a stickler about illness. He doesn’t like the staff working if they’re under the weather. For their sakes as well as ours. You’ll be able to manage all right. It’s only three for lunch, with the Countess and Lady Diedre in Harrogate today.’

‘It’s not a problem, Mr Hanson,’ Mrs Jackson reassured him. ‘Elsie and Mary will help me ter put the food on the serving platters, and Malcolm and Gordon will handle lunch upstairs with ease.’

‘And I shall be serving the wine, and supervising them as usual,’ he reminded her with a kindly smile. Then he nodded and walked on down the corridor, heading for his office. The room was one of his favourites in this great house, which he loved for its beauty, heritage and spirit of the past; he looked after it as if it were his own. Nothing was ever too much trouble.

Hanson had occupied the office for some years now, and it had acquired a degree of comfort over time, resembling a gentleman’s study in its overall style. Henry had arrived at Cavendon Hall in 1888, twenty-five years ago now, when he had been twenty-six. From the first day, Geoffrey Swann, the butler at that time, had favoured him; he had spotted something special in him. Geoffrey Swann had called it ‘a potential for excellence’.

The renowned butler had propelled Hanson up through the hierarchy with ease, teaching him the ropes all the way. Starting as a junior footman in the pecking order, he rose to footman, eventually became the senior footman, and was finally named assistant butler under the direction of Geoffrey Swann. He had been an essential part of the household for ten years when, to everyone’s shock, Geoffrey Swann suddenly dropped dead of a heart attack in 1898.

The 5th Earl had immediately asked Hanson if he would take over as butler. He had agreed at once, and never looked back. He ran Cavendon Hall with enormous efficiency, care, skill and a huge sense of responsibility. Geoffrey Swann had been an extraordinary mentor, had turned Hanson into a well-trained major-domo who had become as renowned as Swann before him in aristocratic circles.

Sitting down at his desk, Hanson picked up the menus for lunch and dinner, which Mrs Jackson had given him earlier, and glanced at them. In a short while, he must go to the wine cellar and choose the wines. Perhaps a Pouilly Fuissé for the fish and a Pomerol for the spring lamb that had been selected for dinner.

Leaning back in the chair, Hanson let his thoughts meander to other matters for a moment or two, and then he made a decision and got up. Leaving his office, he walked in the direction of the housekeeper’s sitting room.

Her door was ajar and, after knocking on it, he pushed it open and looked inside. ‘It’s Hanson, Mrs Thwaites. Do you have a moment?’

‘Of course!’ she exclaimed. ‘Come in, come in.’

Closing the door behind him, Hanson said, ‘I wanted a word with you … about Peggy Swift. I was wondering how she was working out? Is she satisfactory?’ he asked, getting straight to the point as he usually did. ‘Is she going to fit in here?’

Agnes Thwaites did not reply immediately, and he couldn’t help wondering why. He was about to ask her if she was unhappy with the new maid, when she finally spoke.

‘I can’t fault her work, Mr Hanson. I really can’t. She’s quick and she’s efficient. Still, there’s something I can’t quite put my finger on … something about her doesn’t sit well with me.’ Mrs Thwaites shook her head.

‘So I’ve noticed,’ Hanson replied pithily. ‘She did work at Ellsford Manor, and you did get an excellent reference, but then the manor is hardly Cavendon. It’s not a stately home.’

‘Oh, yes, I understand that,’ she answered, suppressing a smile. It was well known that Hanson believed Cavendon was better than any other house in the land, including Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle and Sandringham, all royal residences. ‘I have noticed there is a certain coolness between Peggy and the other maids. I’m not clear why,’ Mrs Thwaites added.

‘Has Mrs Jackson told you what she thinks of Peggy?’ he asked, a brow lifting.

‘Well, naturally Mrs Jackson is pleased with her efficiency, her quickness. It might be that Peggy is just not suitable for this house.’

‘You’d better keep a sharp eye on her, since the maids are in your care, as the footmen are in mine. And I will as well, as I think two pairs of eyes see much more than one.’

Hanson left the sitting room and walked back to his office. He sat at the desk for a moment or two, thinking about the situation in general. They were still missing a third footman, and if they had to let Peggy Swift go, they would be short of a maid. This problem would have to be rectified by the summer, since His Lordship and the Countess had planned a number of events, and there would be weekend guests. Sighing under his breath, Hanson reached down, unlocked the bottom drawer, took out his keys and went to the wine cellar.

A short while later, he was returning to his office, carrying two bottles of wine, when he ran into Walter Swann, husband of Alice, father of Cecily, and valet to Lord Mowbray.

‘There you are, Mr Hanson,’ Walter exclaimed in his usual cheerful voice, smiling hugely. ‘I was just coming along to tell you that His Lordship will make sure lunch finishes early today. He knows Alice and Cecily are joining us in the servants’ hall, and he doesn’t want us to be eating “in the middle of the afternoon”, was the way he put it. He wanted you to know.’

‘Very considerate, I must say,’ Hanson replied, glad to have this bit of pleasant news.

‘I’ll go and tell Cook, and then I must get back upstairs. I’ve a lot of jobs to do for Lord Mowbray today,’ Walter explained.

‘I’ll see you later, Walter. I’m looking forward to having lunch with Alice and your girl. Everyone loves Cecily.’

Walter grinned and hurried towards the kitchen, where he hovered in the entrance, obviously explaining matters to Mrs Jackson.

Once he was back in his office, Hanson placed the two bottles on the small table near the window, and went again to his desk. He dropped the bunch of keys into the bottom drawer, glancing at the clock as he sat down in the chair. It was ten minutes to twelve, and he had a moment or two before he needed to go upstairs to check on things. He looked down at the list he had made earlier, noting that the most pressing item on it was the silver vault. He must check it, tomorrow at the latest. The footmen had their work cut out for them – a lot of important silver had to be cleaned for the parties coming up in the summer.

Leaning back in his chair, his thoughts settled on Walter. How smart he always looked in his tailored black jacket and pinstriped grey trousers. He smiled inwardly, thinking of the two footmen, Malcolm and Gordon, who had such high opinions of their looks. Vain they were.

But those two couldn’t hold a candle to Walter Swann. At thirty-five he was in his prime – good looking, intelligent and hard working. And also the most trustworthy man Henry Hanson knew. Walter brought a smile to work, not his troubles, and he was well mannered and thoughtful, had a nice disposition. Few can beat him, Hanson decided, and fell down into his memories.

He had known Walter Swann since he was a boy … ten years old. And he had watched him grow into the man he was today. Hanson had only seen him upset when something truly sorrowful had happened: when his father, then his uncle Geoffrey, and then the 5th Earl had died. And on King Edward VII’s passing. That had affected Walter very much: he was a true patriot; loved his King and Country.

The day of the King’s funeral came rushing back to Henry Hanson. It might have been yesterday, so clear was it in his mind. He and Walter had accompanied the family to London in May of 1910, to open up the Mayfair house for the summer season.

The sudden death of the King had shocked everyone; when Hanson had asked the Earl if he and Walter could have the morning off to go out into the streets to watch the funeral procession leaving Westminster Hall, the Earl had been kind, had accommodated them.

Three years ago now, 20 May: that had been the day of the King’s funeral after his lying-in-state. Hanson and Walter had never seen so many people jammed together in the streets of London: hundreds of thousands of sorrowing, silent people, the everyday people of England, mourning their ‘Bertie’, the playboy Prince who had turned out to be a good King and father of the nation. There had been more mourners for him than for his mother, Queen Victoria.

Hanson knew he would never forget the sight of the cortège and he believed Walter felt the same – the gun carriage rumbling along, the King’s charger, boots and stirrups reversed, and a Scottish Highlander in a swinging kilt, leading the King’s wire-haired terrier behind his master’s coffin. He and Walter had both choked up at the sight of that little dog in the procession, heading for Paddington Station and the train to Windsor, where the King would be buried. Later they had found out that the King’s little white dog was called Caesar. They had wept for their King that day, and shared their grief and become even closer friends.

There was a knock on the door, and Hanson instantly roused himself. ‘Come in,’ he called and rose, moved across the room. He touched the bottle of white wine. It was still very cold from being in the wine cellar. He must take it upstairs to the pantry in readiness for lunch.

Mrs Thwaites was standing in the doorway, and he beckoned her to enter when she looked at him questioningly. As she closed the door and walked towards him he saw that her expression was serious.

She paused for a moment as she reached his desk and then said, ‘Instinct told me there was something about Peggy that was off, and now I know what it is that bothers me. She’s the type of young woman who’s bold, encourages men … you know what I mean.’

Hanson was startled by this statement and frowned, staring at her. ‘Whatever makes you say that?’

‘I saw her just now. Or rather them. Peggy Swift and Gordon Lane. They were sort of … wedged together in your little pantry near the dining room. She was canoodling with him. I was coming through the back hall upstairs and I made a noise so they knew someone was approaching. Then I went the other way. They didn’t see me. Instinctively, I feel that Peggy Swift spells trouble, Mr Hanson.’

Hanson didn’t speak for a moment, and then he said, ‘There’s always a bit of that going on, Mrs Thwaites. Flirting. They’re young.’

‘I know, and you’re right. But this seemed a little bit more than just flirting. Also, they were upstairs, where the Earl and Countess and the young ladies could easily have seen them.’ Mrs Thwaites shook her head, continuing to look concerned. ‘I just thought you ought to know.’

‘You did the right thing. And we can’t have any carrying-on of that sort in this house. It cannot be touched by gossip or scandal. Let us keep this to ourselves. Better in the long run, avoids needless talk that could be damaging to the family.’

‘I won’t say a word, Mr Hanson. You can trust me on that.’

SEVEN (#ulink_0f1e4701-f2b0-5713-b4ad-2adee0ff7ed4)