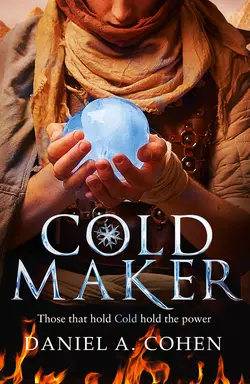

Coldmaker: Those who control Cold hold the power

Daniel A. Cohen

A warmly-written crossover fantasy adventure from Daniel A. CohenEight hundred years ago, the Jadans angered the Crier. In punishment, the Crier took their Cold away, condemning them to a life of enslavement in a world bathed in heat.Or so the tale goes.During the day, as the Sun blazes over his head, Micah leads the life of any Jadan slave, running errands through the city of Paphos at the mercy of the petty Nobles and ruthless taskmasters.But after the evening bells have tolled and all other Jadans sleep, Micah escapes into the night in search of scraps and broken objects, which once back inside his barracks he tinkers into treasures.However, when a mysterious masked Jadan publicly threatens Noble authority, a wave of rebellion ripples through the city.With Paphos plunged into turmoil, Micah’s secret is at risk of being exposed. And another, which has been waiting hundreds of years to be found, is also on the verge of discovery…The secret of Cold.

Copyright (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

HarperVoyager an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © Daniel Cohen 2017

Cover design and illustration by

Stephen Mulcahey © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Daniel Cohen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008207151

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780008207175

Version: 2018-02-23

Dedication (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

For my father

Table of Contents

Cover (#u32256cce-7ea1-5a8b-a2d4-aabd6e3b8c7f)

Title Page (#ue42cb612-7d02-5b8c-8659-ddfbc46cf993)

Copyright (#u31dbe706-ae93-52bc-9fad-4236f9f6328a)

Dedication (#u85686b2e-532a-5937-b7df-f54680a95b8a)

Part One (#u985a1977-c597-55d2-ae05-d993bcd59e0f)

Chapter One (#u50b05419-08fc-5e53-bc7a-04441fea0744)

Chapter Two (#u2db1aea5-17c2-56f5-8ef7-3783c45b42d4)

Chapter Three (#u62110fae-ea1b-5cac-921a-666c6bff89bf)

Chapter Four (#ud295b379-b515-5299-8a3c-e64521ffd2e6)

Chapter Five (#u4c677cfc-7d8e-5282-a0f0-1c4feed3810b)

Chapter Six (#uceaf0184-3dfa-56b4-b81d-ca8d1580defa)

Chapter Seven (#u690a2be1-22c3-5624-afe6-1d0231742474)

Chapter Eight (#ub9c17845-ada3-53f8-b811-be95d18720cd)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

Chapter One (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

The roasted heap of rubbish was mine to rule.

Still, I was careful to check the alleyway nooks to make sure it stayed that way. I dragged my feet across the ground, grains of sand scraping beneath my heels, and listened for the rustle of sudden movements. On nights like these, blissfully dark and cool, I was never the only Jadan lurking in the dark.

I forced out a grunt, the kind taskmasters sometimes make before unfolding their whips, but no hidden mouths sucked in worried breaths. I tossed a handful of pebbles into the heavier darkness just to be sure, but the only response was silence.

As far as I knew, I was alone.

Standing above the pile, its bitter stench biting my nose, I was left with a smile so large it accidentally split a blister on my upper lip. However, my mood was too fine to be disturbed by small pain.

Glinting in the starlight, the rubbish sizzled with possibilities. Mostly the heap would consist of inedible grey boilweed leaves, dirtied up from cleaning and scrubbing, but there were always treasures to be found within. And, thanks to my newest invention, the Claw Staff, my recent rummagings were no longer followed by angry slices on my arms, greasy smells, or nasty fluids staining my hands.

A thin sheet of sand still dusted the top layer, meaning I was the first to arrive. Other Jadans would sift through these mounds of boilweed in the hope of finding a nibble of candied fig, or a discarded fruit rind to chew into a hard pulp. Of course, food was always a welcome find, hunger being one of my longest relationships, but I had a deeper itch. Something that my kind shouldn’t have.

Or at least didn’t usually have.

Once satisfied that I was alone, I finally reached under my clothing and undid the twine keeping the Claw Staff pinned tightly against my thigh. I’d done my best to make my invention compact, but it had nonetheless chafed like a restless scorpion during the day’s errands.

‘What are we going to find tonight?’ I whispered to the metal.

The Staff gleamed in the dim starlight. There was no time to linger. Rubbish heaps, especially those behind sweet shops, were popular destinations for Jadans out past curfew, and I wouldn’t be alone for long.

I shook the Staff’s poles out. The final length got stuck, so I swiped my fingers across my forehead. I was usually a bit sweaty on missions like this, so I smeared the moisture against the carved notches, allowing the pieces to slide out easily.

Swinging the Staff upside down, I brought the sounding orb to my ear and flicked the teeth on the opposite end with my fingernail. The orb was actually just a chunk from a cracked bell, but its vibrations helped let me know what the Staff’s teeth found in the rubbish’s belly.

My heart started to flutter thinking about all the sounds waiting for me.

I thrust the invention in deep, and the orb answered with a tense ping. This was an alert I knew well, since glass was my most common find. Yanking the camel-leather strip that ran through the middle of my invention, I closed the teeth and pulled out a long chunk of broken vase.

I greedily ran my tongue over the small glob left on the glass, ignoring the gritty sand. Sweltering heat had turned the honey sour, but it was a departure from old figs at least. I polished the spot to a shine, careful not to cut my tongue on the edges.

Churning the Staff again, the orb made a dull, earthy sound and I pulled up an old box filled with scrapings of gem candy. I dabbed a finger into the tiny crystals and let them dissolve slowly in my cheek, but I kept the rest as a present for Moussa. My friend needed the sugar’s happy tingle more than I did these days.

Next came a piece of hardened sweet bread, a pinch of discoloured almonds, and half a candied fig which I chewed happily until something moved at the edge of the alleyway, catching my attention.

I figured it was another Jadan waiting their turn, so I decided to move on, considering my haul was already better than most nights.

Gathering everything up, I lined the bottom of the boilweed bag that my father had artfully stitched for these purposes. The design was perfectly unassuming. I could hide the bag anywhere I needed to during the day, even with treasures inside, appearing as just another pile of useless grey leaves.

Scrambling to the roof of the nearest shop, I crouched down immediately, the shingles below me still hot to the touch. I shifted my weight back and forth between my fingertips, my knees quickly growing warm. Sucking down the juice from the gem candy, I watched another Jadan attack the rubbish. The boy was younger than me, his knees knobbly and frail. A long piece of boilweed had been slung around his head as a makeshift patch, and I wondered how long ago he’d lost the eye.

Now that I was gone, the boy dived hungrily into the pile, desperation clear in his movements. Thankfully for him, I’d already disposed of a big glass shard near the top.

‘Pssst.’ I cupped my hands around my lips. ‘Pssst.’

He didn’t startle, but neither did he turn around. I wondered if he was half deaf too.

‘Hey,’ I called a little louder, still barely more than a whisper.

He didn’t stop his rifling, rummaging so fast he must have not cared about sharp edges, willing to trade blood for food.

‘Family,’ I called.

He turned around and bared the few teeth he still had left, giving me a feral hiss. In my barracks we all looked out for each other, but I knew it wasn’t like that in every barracks. This boy didn’t seem used to kindness. I reached into my pocket and grabbed the piece of stale sweet bread, tossing it down as a peace offering.

Not waiting for a response, I crossed the rooftops, crawling flat. The first Khat’s Pyramid stood tall on the horizon, its peak cutting deep into the night sky. The monuments of the Capitol Quarter were all impressive, with their precise stonework and decorative flags, but no buildings, not even the other pyramids, came even close to the first Pyramid’s height or splendour.

I didn’t have much time to dawdle, but looking up so high made my heart ache with wonder. Cold was falling to the land beyond the Pyramid as the World Crier let loose from the sky above. Deciding the Crying was worth a pause, I rolled onto my side and gazed into the night sky. Thousands upon thousands of pieces of Cold were shooting from the sky every hour, brushing through the dark. I knew that most of the Cold falling in the Khat’s massive Patches would be small Wisps, but there would be Drafts, Shivers and Chills in there too. I squinted, trying to look for any particularly large streaks, hoping that tonight might be one of those rare times I was lucky enough to see a Frost, the most sacred of all Cold.

I didn’t, but Frosts only fell once every few weeks, so the chances were slim anyway.

In the morning, hundreds of Patch Jadans would scramble through those brown sands, digging up all the Cold for the Nobles whilst taskmasters would watch, their whips at the ready, making sure it was all collected.

I tried to imagine the time before the Great Drought, when Cold was Cried throughout the entire world. When we were young, we were told stories of lands flushed green and alive, where you could walk a hundred feet in any direction and pick fruit as big as your fists. Where the Cold would break on mountain rocks, cooling the air and the boiling Rivers, so that you could swim, and drink straight from the current. And every city had bountiful Cry Patches, their gardens swollen and lush.

Now Cold only fell for the Nobles here in Paphos.

Everyone else was unworthy.

I sighed, knowing it wasn’t good to dwell on a past I couldn’t even remember. Eight hundred years later and the world was lucky that Cold still fell at all.

I rolled back over, the hard callouses on my palms making it easy for me to shuffle quickly and quietly without tearing my skin. Shadows flitted silently on the nearby rooftops, crawling in a similar manner. Some figures chanced moving at a crouch, their knees hugging their shoulders, but taskmasters knew to look up to the roofs. Keeping flat was my best chance of survival.

Most Jadans huddled around the Butcher’s Quarter, hoping to gnaw on the piles of old lizard bones, but I never went pilfering over in that part of town. The ones that sought to lord over the old meat had traded in mercy long ago, and rancid scrap wasn’t worth a brick lodged in the back of the head.

I made my way towards the Sculptor’s Quarter, knowing these alleyways wouldn’t be so crowded. A Sculptor’s leavings were never very satisfying for a hungry Jadan, but I needed materials for the board game Matty and I were creating, and every once in a while I’d find a little ceramic carving. My young friend had the rules just about finished, but we needed a few more pieces to round out both sides of play.

The Sculptor buildings were works of art themselves, with statues of famous Khats of the past chiselled into their stone walls. A Jadan was supposed to drop to their knees if they looked directly at an image of the Khat, but since I was already crawling, I decided there was no need.

The pile of rubbish closest to the back door of Piona’s Moulds looked most promising, so I climbed down to the alley, giving my invention a stern look. ‘Find me something good,’ I whispered.

It obliged.

A ping … a barely cracked chisel.

A harsh scraping … three sheets of sandpaper, still a bit rough.

A thrum … a small chunk of marble that I think might have once been a Khat’s nose, with powerful, flaring nostrils. The chunk was a bit big as it was, but I figured I could shape it up and let Matty decide its fate in the game.

By the time I’d reached the Ancient Quarter my knees were bruised, but my bag had a satisfying heft.

Only three Ancient Shops existed, large domes of white limestone, with curved doors locked by chain upon chain. These shops were only ever frequented by the Highest of Nobles, as the domes contained relics from before the Great Drought, sold for extraordinary sums.

Legend had it that their shelves were stocked with metal machines which moved on their own, hourglasses which told time without sand, and lanterns which needed no fire to survive. The walls were without windows, and every time I passed by I wished I could invent something which could help me hear through stone.

My scuttling was halted at the sound of laughter coming from below.

‘So I told my father,’ a young Noble slurred, popping a Wisp into his wineskin. He downed a swig, red liquid sloshing down the front of his fine silk shirt. ‘I have no idea where the Chill went! Must be one of the new Jadans. I believe you’ve purchased a bad batch of slaves at auction, dear man.’ He held up a fat bejewelled ring for his friend to see. ‘Yes. Definitely stolen by one of the slaves. Oops.’

Grinding my teeth, I moved on.

The walls of the Garden Quarter came into view, fifty feet high and smooth as glass. The place could house three of my barracks, and I could only imagine the paradise I’d see if I could somehow catapult myself over their walls. There would be more figs than we would be allowed in a lifetime, not to mention the grand things we never got to eat, like orangefruit, plump grapes, baobab fruit, and Khatmelons.

Carrying on, I passed the row of Imbiberies. Most Noble festivities were held in this Quarter, constituted of lively shops only open at night, serving mead and music. I paused to listen to the melodies escaping from the windows, but I was spurred onward by the crack of a taskmaster’s whip, followed by a high-pitched pleading.

A few more stubbed fingers later, I finally reached my favourite spot, landing softly on my feet. The Smith Quarter were situated on the far west side of the city, removed so the loud bangs didn’t bother anyone. The back alleys were studded with anvils, as the kiln fires made the buildings too hot to work in all day. The waste ditches were always plentiful, filled with oily mounds of boilweed waiting to bestow gifts.

I manoeuvred the Staff into the heart of the biggest heap, my chest tingling with anticipation. After some heavy sifting, the sounding orb made a series of happy pings.

An old hammerhead, bent and rusty.

A chunk of bendy tin.

Half a dagger hilt.

Five links of chain, still attached.

A rusty hinge.

My bag expanded and my chest filled with the one good warmth this world can offer. I wanted to kiss my invention, but fearing what my cracked lips might taste, I said a silent prayer of thanks to the World Crier instead.

Even though the Khat’s Gospels assured us his Eyes were closed to Jadankind, I was thankful all the same. The Crier above never plagued me for being out after curfew, and for this I was always grateful.

I thrust the Staff in one last time, all the way up to my knuckles, my wrist straining to pull it through the pile. The exhausted muscles in my arm groaned until at last the orb gave a shout, long and high.

I frowned, not recognizing the sound.

It took a few pulls for the teeth to clamp around the mystery object, and with careful speed, up came a miracle.

Or a disaster.

Breath caught in my throat, and my knees went weak as I picked up the Shiver with shaky hands.

It was more Cold than I was rationed in a month.

My brow prickled with sweat. I often came into contact with Shivers, but never like this. Never one that I could keep for myself. Smuggling bits and pieces home was one thing, but if anyone found a Shiver in my possession, my body would be the first to be hurled by the dead-carts into the dunes.

I brought the beautiful round of Cold closer to my face, entranced by its lovely sheen.

A part of me knew I might get away with keeping it. I could shave off pieces and share them with the rest of the Jadans in my barracks. I could tinker with it for hours.

Maybe even use it for my Idea.

My fingers trembled as I weighed my options. This was a once in a lifetime find. Once in a hundred lifetimes. My vision went light, my body swaying beneath me as my balance faltered. Taskmasters were out there, and I had to decide quickly.

My forehead beaded with more of my namesake sweat, my heart throbbing with the terrible decision.

I tossed the Shiver back on the pile, seething with frustration.

I’d heard enough warnings throughout my life about us Jadans trying to keep any Cold for ourselves. Often these stories ended in curses that melted our eyes, and angry spirits rising up from the deepest cracks of the Great Divide to carry us back into the darkness. I had never seen anything like this happen in real life, but I didn’t want to chance it. The World Crier had taken Cold away from Jadankind for a reason, and who were we to go against eight hundred years of punishment?

I turned away from the Shiver to avoid any further temptation, when, for the second time that evening, my heart nearly stopped.

A figure was watching me from the rooftops. Her braided hair framed a Jadan face hardened by thought, and I could tell she had been watching me for some time, her focus directed on my Claw Staff rather than on the Shiver.

I froze, guilty about my temptation. But before I could say anything, she moved, darting off into the night.

I climbed back to the nearest ledge to get another glimpse of her. But what I saw next made my jaw drop even more than finding the Cold.

The girl was running, proud, high, and fast, her back completely straight for all the taskmasters in Paphos to see.

Jadans didn’t run like that, ever. We were inferior, and we were supposed to show it at all times. Her posture was an outright scandal, and my back ached just watching her move.

By the time I caught my footing she was half a dozen rooftops away, her spine as straight and rigid as a plank of wood. Surely she’d be spotted. Surely this would be her last night racing along the rooftops. I sighed, praying that her death might be quick.

I crouched down once again and started crawling home. I’d gathered enough materials for the night anyway.

I tiptoed around Gramble’s guardhouse, making sure the sound of crunching sand under my toes was minimal. My Barracksmaster turned a blind eye to my night runs, but that was all he could do. If he caught me in the act, the Khat’s law required punishment for both of us.

I inched towards the loose panel in the wall of my barracks. Taking one last look up at the sky, my eyes searched for Sister Gale within the flurry of stars. She was bright and shining, blowing tonight’s air cooler than most nights, and I gave Her a quick nod of thanks.

The panel into my barracks came away easily, and I slipped inside mine and my father’s private room. The cracks in the ceiling let in just enough starlight for me to make my way to bed.

Abb, my father, was already lying on top of his blanket, dreaming. I hovered over him for a moment, noting the terrible new angle in his nose. The side of his face was puffy, and in the morning, I knew his eyes would be ringed in crusty purple bruises.

Most nights when I chanced sneaking into the heart of Paphos, I’d come home to find him waiting up for me, ready to eagerly appraise each new piece of treasure and ask what I planned to use it for. I couldn’t wait for the morning, as I was dying to tell him about both Shiver and the girl.

I reached out and placed the almonds I’d found beside his bed. Then, I reached into my bag to sort through my treasure. My new metal links rattled as I filed them away, but Abb didn’t stir. He must have had a long shift over at the Pyramid.

Having tidied my treasures into their respective holes in the ground, I settled onto my blanket and closed my eyes. My remaining few hours were spent dreaming of Cold.

Chapter Two (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

I awoke with a start to my father hovering over me, smiling as he crunched the almonds.

‘You didn’t wake me,’ he said reproachfully, wincing as he chewed.

I sat up, blinking away the images of long hair and an unseemly posture. I stretched from side to side as I drank in the morning light which filtered through the slats in the roof. I could already tell the Sun wouldn’t be taking it easy on us today. The air inside the room was already stifling, thick with the sky’s hatred.

‘You were asleep,’ I said.

‘Well, that happens every night,’ replied Abb, swallowing the last almond. ‘Not a good excuse.’

I raised an eyebrow. As I’d guessed, the bruises now marked his face. ‘Looked like you needed it.’

He ignored my comment, changing the subject instead. ‘So, what did you find?’ he asked, poking me gently in the chest.

The memory of the Shiver shot back into my mind. ‘I—’

He held up a hand. ‘On second thoughts, I believe I can figure it out by myself.’

‘You’re not going to guess—’

He held a finger up to his lips, a playful look in his eyes. ‘I said I can figure it out. You certainly didn’t learn your listening skills from me, Little Builder.’

The name was one of my father’s continuous jokes, referring both to my inventing and the fact that I still had many years to go before I was assigned to become a Builder like himself. I liked it a lot better than my other nickname.

I shrugged, blinking the sleep away from my mind. My body pleaded for more, but there was nothing I could do until later. Thinking about my new finds, I assured myself the sluggishness was a worthy price.

Abb walked over to my tinker-wall, bearing down upon the stores of materials. I’d dug different ditches for each type, and his fingers swept along the space above the piles.

‘Ah, a new chisel,’ he remarked, pointing to the tool pile. ‘Good find.’

I nodded, my mouth dry and dusty. I tried to dredge up the sweet taste of candy dust, but crawling around all night had given thirst control over my cheeks. I was eager for the bells to ring so we could start our rations, as my head was throbbing from lack of water.

‘Lusty metal,’ Abb said humorously, staring down at the chains. ‘One day you’ll be old enough to understand that joke.’

‘Links,’ I corrected, rolling my eyes. ‘And I understand it just fine.’

He winked, giving me a knowing smile before bending over the pile of jars, fingers snatching something off the top. ‘Where’d you get this?’

He turned around, something foreign in his grip.

At first glance I didn’t recognize what he was holding up. The golden-hued vial was unblemished, and I didn’t remember picking up anything like it. The jars in my stash were usually empty and broken, and I turned the decent ones into medicine vials for Abb. This one, however, looked as if it belonged on the display shelves of an apothecary. The sleep was still thick in my brain and I couldn’t come up with an answer.

Abb came closer, holding it out to me. ‘So, what is it?’

‘I don’t know.’ I squinted, trying to make out the greenish material inside.

Abb’s face broke into a coy smile.

‘Well, it looks like the colour of a birthday present.’ He chuckled, smacking the vial into my palm. ‘Or part of one at least.’

My mouth gaped as I held the vial out to a sunbeam, illuminating its contents. The inside gloop was viscous and slick.

‘This is for me?’ I asked, stunned. I shook the small vial, the jelly wiggling inside. ‘Is this groan salve?’

‘It is indeed,’ he said, with a slight puff of his chest. ‘Mixed carefully with a father’s pride.’

‘How’d you get it?’

‘If you must know the truth.’ He shrugged, going quiet for a moment. ‘It fell from the sky, specifically for you.’

I shook my head, somewhat serious. ‘You can get into trouble for lies like that.’

‘I’ve lived long enough for trouble and I to have grown a mutual respect,’ Abb replied simply, scratching his fingernails across the frizz on my head. ‘But if you’re worried, better use it up quick.’

I pushed his hand away, smiling, and took the cap off the salve. It smelled like a taskmaster’s feet, but I knew it was the best remedy for an unforgiving sting. I’d only ever been lucky enough to find a nip or two before, never a full bottle.

Abb then reached into the top crate of my invention-wall, retrieving one of my crank-fans. It was still a work in progress, since Nobles never threw away good blades, but I’d managed to file down some sturdy awning as a decent substitute.

Abb held the fan in front of his face and turned the lever, spinning air across his cheeks. The little thing gave a garbled whirr, its bearings rusty, but his face lit with delight. Once he’d finished with it, he gave it an appraising nod, as if all was right in the world.

Harsh light now tunnelled through the roof, brighter and more invasive. I could feel the hungry morning heat tasting its first bites of my face. I slapped my cheek, trying to wake myself up a bit.

‘The sky had something else for you, Little Builder,’ Abb said after a few moments, putting the crank-fan back in its crate.

‘This groan salve is already too much,’ I said. Sometimes Abb’s thoughtfulness overwhelmed me, his gentle heart highlighting the brutality of the previous father to whom I’d been assigned. ‘And would you stop saying the sky had things for me?’

Abb considered the ceiling, stepping out of a strong spear of light. He reached into his pocket and retrieved some things that made me reconsider everything that had happened the night before.

With shaking hands, he offered me three small, gleaming Wisps. I didn’t miss the pleased twitch in his lips as I took them.

My heart raced looking at the three pieces of Cold. I knew Abb was okay with me breaking a few barracks’ rules like sneaking out in the night, and reclaiming rubbish, but never had he encouraged me to break a holy law.

‘We can’t have our own Cold,’ I said, stunned. ‘You’ve said so yourself.’

He nodded, bobbing his head up and down. ‘Perhaps that was true.’

Three tiny Wisps paled in comparison to the might of a Shiver, but it was illegal for a Jadan to keep even the smallest measure of Cold.

‘What do you mean?’

Abb dropped the Wisps in my lap, so I had no choice but to take them. ‘In a way, truth ages, just like we do. You aren’t the same as you were a year ago, nor will you be the same on your next birthday. I think you’re ready for some new truth. So take the Cold. Use the Wisps, or hide them.’ He put a hand on my cheek. ‘Who will know?’

I froze up at his words. How could my father, the best Jadan I’d ever known, encourage such blasphemy?

‘But what about the World Crier?’ I replied, a lump in my throat. ‘He’ll know.’

Abb gave an understanding nod. ‘He let the Cold travel this far.’

‘So?’

Abb sucked his cheek, seemingly testing a bruise from the inside. From the look on his face it was quite painful. ‘So, there are the Noble laws, and there are the Crier laws. They’re not always one and the same.’

I paused, feeling myself getting flustered. This wasn’t a subject we’d ever broached, and I was uncomfortable with his disorienting words. ‘But the Khat …’

‘They’re not always the same, Micah.’ He stretched his fingers, striped with sizzling ribbons of light. ‘But this might be a conversation for another time. Let’s leave it there for now.’

‘Thank you,’ I said in a thin voice, petrified that the Crier might punish me for having the Wisps. But then again, Abb had no signs of plague, or evidence that demons had tried to rip out his eyes, and he’d have been in possession of the Cold for at least a night.

‘Ah, but you can’t thank me yet.’ He smiled. ‘That’s not the last of your gifts.’

‘No more,’ I said, taking shallow breaths just in case. ‘I’m going to have a hard time using all of the others.’

Abb’s face suddenly turned serious. He glanced at the thick boilweed curtain that served as a door, even though I’d heard nothing from the other side.

‘This is not a gift to use, Micah,’ he said, his voice suddenly heavy with emotion. ‘But one for you to remember. Promise me.’

I nodded, a bit afraid of this serious turn in him. A small smirk or tiny laugh usually hovered somewhere about his lips, but right now his face was iron.

Abb placed his fingers on my sweat-riddled forehead. His quiet voice rose and fell in a beautiful lilt I’d never heard before, one which sucked the silence out of the room and transformed it into something more profound, beyond language. My father had a good singing voice, but this felt different from the times he’d forced out the ‘Khat’s Anthem’ or ‘Ode to the Patch’. The devastatingly beautiful sounds coming from his lips left my head reeling.

Then the words stopped almost as swiftly as they’d begun.

‘Again,’ he said in a stern voice, ‘listen.’

I nodded, trying to ready my ears this time.

He repeated the lovely melody, and I caught every last syllable, filing them away like the most precious of my findings.

—Shemma hares lahyim criyah Meshua ris yim slochim—

‘Did you get it?’ he asked, voice soft.

I nodded, concentrating so hard that my ears rang.

‘What does it mean?’ I asked.

‘However would I know a thing like that?’ he asked, removing his fingers and backing away, a bit of the trademark humour returning to his eyes. ‘I don’t speak Ancient Jadan. Now get out of here and find your friends.’ He attempted a broad smile, but winced, the sunlight claiming the bruises on his face. ‘They’re probably eager to give you their own birthday gifts.’

Matty smirked, hands gently slapping his knees in anticipation. ‘What’cha get me?’

The three of us huddled together in a corner of the common chamber, away from the shabby grey flaps that divided the family sleeping areas. Sitting on the sandy floor, our legs were crossed and knees touched so we’d take up the least amount of space.

‘What did I get you?’ I asked. ‘I never thought you would be so greedy.’

Moussa scowled for the group, but aimed a private wink my way. ‘Grit in your figs, Matty. It’s Micah’s birthday. You should just be glad that he got home safe.’

Matty’s face turned bashful. ‘Spout always gets me something when he goes out. Always.’

‘You have got to stop calling him that.’ Moussa let out a pained sigh. ‘Don’t you know that no one calls him that any more?’

I shrugged. In truth, most Jadans in our barracks – and indeed in the streets – still called me Spout, a nickname I’d come to terms with a long time ago. It wasn’t just enough that my loose forehead wasted more water than other Jadans my age, they had to remind me of the fact.

‘I don’t mind “Spout”,’ I said. ‘As long as Matty doesn’t mind me sweating on any future gifts.’

Matty lowered his head, eyes going to his lap where his hand was stroking the small feather that I’d fashioned him from metal and fabric. I don’t know why Matty kept up this fascination. Clearly the creatures were extinct, no possible way they could survive in the harsh conditions after the Great Drought.

‘Did’ja see any birds?’ Matty asked, his tone still hopeful, even after all this time.

‘Here’s the thing,’ Moussa said, giving Matty’s ear a playful flick. ‘Why would a creature live in the sky and choose to be close to the Sun? You should know it would crisp up after a few flaps.’

I rehearsed what would surely be Matty’s next words, holding back my smirk. My small yet vibrant friend said the same thing every time: You know, Cold lives up—

‘Y’know,’ Matty said right on cue, guarding the side of his head against another flick. ‘Cold lives up in the sky too. So if there was any birds left, they’d prolly come out at night.’

‘No sign of birds yet,’ I said, cutting off whatever cutting remark Moussa was preparing. ‘But I promise if I see one, I’ll lure it back for you.’

‘Y’know that they sing, don’cha, Moussa?’ Matty said, swiping the feather through a small pillar of light that was sneaking through the ceiling. ‘You could prolly lure one down, if you tried hard enough.’

I looked over at Moussa, hoping the talk of music might cheer him up a little, but he said nothing, his expression remaining sombre. Moussa’s Patch birthday was nearing, and lately he hadn’t been in the singing mood, which was too bad, as his voice was arguably the best in the barracks. On top of that, Sarra and Joon had taken to spending their free hours in one of the empty boilweed divisions, which I imagine didn’t help Moussa feel any less forlorn.

Matty tucked the metal feather behind his ear, licking his dry lips. My small friend looked almost as ready for water as me. ‘One day you’re both gonna see I’m right. I know it.’

‘Doubtful,’ Moussa said under his breath.

‘However, I do have gifts.’ I leaned forward conspiratorially, trying to brighten the mood. ‘And news.’

Matty stuck out his palm, his smile practically spanning the common area.

I produced the marble nose chunk. ‘For our game. I figured you’d know what to do with it.’

Matty wiggled his eyebrows in delight, taking the carving and holding it up to his face. ‘Howsit look?’

‘A bit big,’ Moussa said with a contemplative look. ‘But you should know, most things are big compared to you.’

Matty stuck out his tongue. ‘Just wait some years. When I’m turning fifteen like Spout I’m going to rest my elbow on your head all the time.’

Moussa craned his neck to full height. ‘We’ll see about that.’

I then pulled out the box of gem candy remains and laid it on the hard sand at Moussa’s feet, opening the lid. ‘For you.’

‘It’s not my birthday yet – thank the Crier,’ Moussa replied, shaking his head. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a handful of gears, nearly free of rust, and with most of their teeth. ‘For you.’

My eyes went wide with shock. ‘Where? How did you … Thank you. They’re perfect.’

‘They’re not much.’

I put a hand on his shoulder. ‘Once I need them, they’ll be everything. Tinkering is only fun when you have things to tinker with.’

Matty’s face dropped, guilt flooding his face, and he tried to hand the Khat nose back to me. ‘For you?’

I laughed. ‘Just figure out a place for it in the game. That’s good enough for me. It’s about time we finished that thing.’

‘I should of got’cha something,’ Matty groaned.

‘Really, I don’t need anything else.’

Keeping his head slumped, Matty reached out his arm and tilted his hand backwards, offering up his ‘calm spot’. I touched my thumb to the splotchy birthmark on his wrist, which for some reason comforted my young friend whenever he felt like he’d done something wrong.

‘Family,’ Matty said.

‘Family,’ I repeated, letting go and gesturing both of them closer. ‘So last night I was in the Smith Quarter and found—’

A foot dug into the sand near my knee, spraying up a light coating into our faces. Then a gravelly voice said: ‘They put it in the ground!’

I sat back to look into the loopy face of Old Man Gum, grinning at us through a mouth full of black gaps. As he was the oldest Jadan in our barracks, with skin dark as soot, we had to show him respect, even though he never made much sense.

‘Morning, Zeti Gum,’ Matty said, offering the youthful term of respect.

Gum bent down and patted us all on the head, then, without another word, he wandered back to his private space, tucked aside the boilweed curtain, and slumped back to his ratty blanket. There was enough space to watch him land directly on his face and tap the ground, listening for a response.

Matty picked up the metal feather Gum had accidentally knocked from his ear, and slipped it in his pocket.

‘Anyway,’ I said with a smile, ‘last night, when I was in the Smith Quarter, I found a full Shiver in the boilweed.’

Matty’s eyes went wide. ‘Did’ja touch it?’

I gave a slow nod, feeling a lump in my throat.

Matty angled his head to look at my palms. ‘Did’ja hands burn up?’

I splayed them wide, calloused yet unharmed. ‘Nothing.’

Moussa looked at me, astounded. ‘Where is it now? You didn’t try to keep it, did you?’

From the concern in his voice, I thought it best not to mention the Wisps that Abb had given me. My stomach churned at even the thought of betraying the Crier. It was probably best to bury the Wisps and never speak of them again.

‘It’s still there,’ I said, keeping my voice down. I looked around the barracks to see if anyone could overhear us. ‘I think so at least. I don’t know for sure, because when I put it back there was a girl watching me.’

Matty’s face broke into a coy smirk. ‘A girrrl …?’

I reached across and flicked him on the arm. ‘Listen. There was something different about her. She was—’

‘Spout.’ The desperate voice came from over my shoulder.

I turned around and found sweet Mother Bev hunched over, hands on her knees, panting slightly. ‘Can I use a crank-fan, darling?’

‘Of course, you never have to ask.’ I went to get up, but she put a gnarled hand on my shoulder.

‘I’m still able,’ she said with a cracked voice, shuffling off. ‘Blessings, child. May fifteen be Colder than fourteen.’

I watched her walk away. I hated it when she said things like that, as blessings were supposed to be saved for the Khat and Crier only.

When I looked back, Moussa was dabbing his finger in the gem candy dust. He gave me a sheepish look. ‘Thanks, Micah.’

‘Don’t mention it. So this girl,’ I held my palm up like a blade, trying to approximate her posture, ‘she was running on the rooftops like this.’

Matty frowned. ‘Smacking the wind?’

I shook my head with a chuckle. ‘No, her back. She ran with her back completely straight. A Jadan, running like that. Crazy, right?’

Moussa paused and then gave a long shrug. A few boilweed flaps began rustling behind us, bodies in motion, so he lowered his voice. ‘Here’s the thing. That’s weird, I suppose. But she was already out, breaking one rule. What would stop her from breaking two?’

I hadn’t thought of it like that, but something about the memory still bothered me. We weren’t supposed to move like that, so tall and proud, and it almost felt like a worse transgression than hiding Wisps.

I slipped the gears into the candy box and placed it against the wall. From the amount of light basting the roof, I knew the chimes would be ringing soon, and we needed to get ready.

‘Spout,’ a deep voice boomed.

I turned back and found Slab Hagan looming over our group, his meaty body blocking at least five beams of sunlight from reaching the floor. One of my scorpion traps dangled in his hands, the face of the box shut and sealed.

‘Morning, Hagan,’ I said.

‘I’ll eat it when you done?’ Slab Hagan asked, his eyes gleaming with hunger. I never understood how he maintained such a frame on a Jadan diet, even supplemented by the occasional insect.

‘Please,’ he added in a gruff voice.

I made sure the springs of the trap were tight so the scorpion wouldn’t escape, and put it aside for later extraction. ‘Of course. It’s yours.’

Slab Hagan gave something of a thankful bow, and hulked away to his place near the main doors. Jadanmaster Gramble offered double rations of figs and a thick slice of bread to whoever was first in their respective lines, and at this point the Builders just let Slab Hagan have the honour.

The morning chimes rang out and everyone scrambled from their boilweed divisions into the common area, donning dirty uniforms and breathing heavily. The air in the chamber was already thick with the Sun’s heat, and was only getting hotter. The four distinct lines settled together, stretching from wall to wall of the main chamber: Patch, Builder, Street, and Domestic. I landed near the end of my line, the Street Jadans, tucked between Moussa and Matty.

The chimes were all still ringing with ease, and my head swivelled upward, admiring my handiwork of pulleys and cables. Other Barracksmasters used whips and chains, and in severe cases, sprinkles of acid to wake up their Jadans, but Gramble was kind, and he deserved a kind system for rousing us. It had only taken a few days for me to tinker my bells idea into reality – Gramble had access to all the materials he wanted – and I’d received triple rations for a week. Now, to get the system to sound, all our Barracksmaster had to do was pull a lever beneath the sill of his guardhouse window.

I pressed a finger to my hard and scabby lips, ready for water. Looking around the lines, I caught many of my family looking over to me, knowing today was the day I turned fifteen. I got a deranged wave from Old Man Gum, a round of smiles from most of the Domestic line, a playful flash of ten fingers and then five from Avram, and a dozen other little gestures of love.

Gramble’s key flitted inside the lock of the main doors, the tink of metal replacing all the conversations in our rows. The doors flung open and our ruling Noble waddled in, dragging the rations cart behind him. Our tired faces cracked with excitement at the sight of the sloshing buckets. Of course, the relief would be short-lived, as the daylight behind him was already baring fangs.

Gramble unhooked the Closed Eye from the side of the rations cart, spinning the pole so the symbol would stand above us. The copper representation of the Crier’s Eye had its lid sealed shut to our kind, just as the Gospels dictated. It was a reminder of the sins of past Jadans, which the Crier could never forgive.

The Patch Jadans were first for rations, since they had the longest distance to cover and the hardest days ahead. At eighteen, life became excruciating for the young Jadan men, and many of their bodies looked frail from overuse, skin tanned black as shadow. The Sun showed no mercy to those tasked to work in the deep sands, collecting all the Khat’s new-fallen Cold. At the front of the Patch line, Joon kneeled before the Closed Eye, tucked in his chin, and said in a clear voice: ‘Unworthy.’

Gramble nodded, offering in return a cup of water with a single Wisp, and a double ration of figs. The rest of the line of Patch Jadans followed suit, kneeling and offering their regrets to the Eye before passing through the door to face the brutal light of the day.

If a Patch Jadan survived for five years in the blistering conditions, they became a Builder, repairing streets and walls and erecting monuments to the Khat. The Builders were next for rations, Slab Hagan leading the group. He kneeled, but was still almost as tall as Gramble.

‘Unworthy,’ his large mouth boomed.

The cooped-up air in the main chamber began to grow stifling, Sun making its impatience known. Soon it would be warmer inside the barracks than outside, which was saying something.

Abb successfully roused both his patients still stuck in their boilweed divisions – a silent wave of relief sweeping the lines as Dabria coughed her way to her feet – and my father filed in behind the rest of the Builders, giving me a wink before kneeling for rations himself and sweeping through the main doors.

Once the Builders had all left, the Street Jadans were next.

Ours was the largest group, Street Jadans compromised of both boys and girls aged ten to eighteen, and it took a little while before I reached the rations cart. Moussa looked back and gave me a little nod just as he passed through the doors.

I kneeled, dropping hard against the sand. I felt as if I should say the word louder than usual today considering the three Wisps hidden under my blanket. ‘Unworthy!’

Gramble nodded, beckoning me to stand.

‘Spout,’ he said, the nickname always tilting his bushy eyebrows with amusement.

‘Sir.’ I eyed the bucket of water longingly. A night of scavenging always left me famished.

Gramble scooped up a sizable portion of water and then passed it my way. But before I could take it in my shaking hands, he snatched it back, a glib smile on his face.

Then he reached into his pocket and held up a Wisp, dancing it across my eyes.

‘Sir, I—’

He dropped the extra Wisp into the cup and pressed it against my chest. ‘Congratulations on making it to fifteen, boy.’

I stood there, shocked at my good luck. I felt the Closed Eye glaring at me from behind its lid, knowing my guilty secret.

‘Come on now, Spout, drink up!’ ordered Gramble. ‘The Domestics are still waiting their turn!’

I trembled as I lifted the water to my lips, the cool liquid splashing across my blisters and cuts, lighting up my tongue with pure ecstasy. After a night of swimming the rooftops, the water tasted of pure and complete decadence. My stomach wasn’t prepared for the splash of Cold, clenching up tightly at first until it relaxed and enjoyed the gift.

Gramble gave me a large handful of figs and ushered me through the doors, the sunlight smacking me in the face like a fist. However, as hot as the sky was, no pox struck me down, and no spirits from the Great Divide came to drag me under the sands to my death. I could only assume that since I hadn’t actually asked for the three Wisps, the Crier might spare me the wrath.

I moved fast, needing to reach my corner before the morning bell tolled. Jadanmaster Geb was lenient on lateness, but plenty of taskmasters would be waiting in the shadows to make up for this tolerance, hoping to catch their own Jadan and have some fun at our expense.

Chapter Three (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

Every Jadan’s life is planned from start to finish.

We’re born and raised in the Birth Barracks, and when our minds start getting spongy we’re sent to the Khat’s Priests to learn the Crier’s doctrines and rules. Once we turn ten, the girls with the lightest skin and most comely faces are assigned to be Domestics, and the rest are given a street corner, patiently awaiting orders from a taskmaster, merchant, or Noble of any kind.

A Jadan can always be purchased outright by a Noble, but this comes at a high price, and most Nobles are happy borrowing any Jadan they see fit.

I had three more years of Street duty left, and I wanted them to last as long as possible. My corner was one of the most vibrant in Paphos, and I served under one of the finest Jadanmasters.

Moussa ran ahead of me until he took a sharp turn in the direction of the Bathing Quarter. I kept onwards towards the heart of Paphos, the Market Quarter, snaking my way across my favourite rooftops and deserted alleyways. After five years on Street duty, the pads of my feet were hardened and leathery, immune to the heat of stone. As tough as my heels had become, however, my toes were still susceptible to bites, so I made sure to keep an eye out for forked tongues rising in the gaps. It was rare to run into a Sobek lizard, as they usually didn’t stray far from the boiling water channels pulled off the River Singe, but it was important to stay vigilant. The lizard’s poison couldn’t kill, but errands were quite difficult with a splitting headache and hives.

I speeded up as I spotted two other Street Jadans from another barracks in a nearby alleyway, crouching over a pile of billowing smoke. One of them was holding a sizable shard of glass against the sunlight, focusing the ray on some smouldering boilweed. Both mouths were sucking in large breaths, wafting the fumes towards their faces with sooty fingers, stifling coughs. They’d have to smoke quickly if they were going to make it to their corners in time, but they didn’t seem too concerned.

Some Jadans claim the boilweed makes errands pass like a pleasant dream, and taskmasters’ whips feel like soft kisses. I’d tried the smoke once, but it just made me feel sick, and the residual cough had earned me more than one slap on my throat.

Sweat gathered on the lobes of my ears and I cursed myself for wasting water; every drop counted in this hotbed of a world. I was the only one of my friends who still had the problem. Spout was about as accurate a nickname as any.

Keeping the safe route into the Market Quarter took me longer than I would have liked, but fortunately the day was still early, and the warning bells hadn’t yet rung. Most of the Nobles I would serve today were still asleep, cool under their thin sheets, the richest being fanned by their personal Domestics.

I jumped from a low roof onto the edge of a shop and bounded onto Arch Road. I scrambled over to my corner and pressed myself against the wall. Placing my hand at my sides, I fell into my best slave stance: shoulders rounded, chin down, a slight bend at the hip.

The wall of my corner was slightly pronounced at the top, offering me a few fingers of luxurious shade. Keeping my chin tucked, I watched the other Street Jadans out of the corner of my eye, slipping out of the surrounding alleyways just as the morning bells rang out. I was happy to see the Jadans I knew still on their respective corners, none of them having fallen at the hands of a taskmaster yet.

The final ring was our cue to begin the ‘Khat’s Anthem’. I cleared my throat and launched into the song along with everyone else.

The Crier’s might upon his name

Worthy of the Cold

Dynasty forever

Service for your soul

Blessed be our master

Who keeps us from the sands

His holiness the Khat

Who saved life upon the lands

Holy Eyes have long forsaken

Those of Jadankind

But the Khat is made of mercy

For those blind to the Cry

He keeps us from the darkness

He gives us hope and grace

Long live the Khat and all his sons

Who saved the Jadan race

Jadanmaster Geb skipped onto Arch Road just as the song finished, a big smile on his face. As always, his robes looked new; these ones a jolly shade of green, bright enough to be seen all the way from Belisk. He wore a head wrap of matching green, meticulously tied to hold back his long hair enough to show off his dangling emerald earrings.

There was a reason Geb often had enough Cold to buy such extravagant outfits. From what I understood, Jadanmasters received bonus Cold for keeping their slaves obedient and swift. Since we all appreciated his kindness, there was something of an unspoken pact among the Arch Road Jadans to work hard to make him look good. Even though Jadanmaster Geb was from a High Noble family, and didn’t technically need to work, every Jadan on Arch Road welcomed his presence. Taskmasters didn’t appreciate his softness, or the fact that his skin was darker than most High Nobles, but Geb was confident enough not to care.

He checked us off one by one in his ledger, and stopped in front of me, bending over and slapping me lightly on the cheek. ‘Salutations, Spout.’

‘Sir,’ I said, happy to bask in his shade.

‘I appreciate your promptness, as per usual,’ he said, and I could tell that he meant it. ‘I challenge that if all Jadans were as dutiful as you, the commerce of Paphos would run smoother than silk through fingers. May this birthday be filled with swift and important errands.’

Even the fact that Geb called us ‘Jadans’ rather than ‘slaves’, or ‘Coldleeches’, or ‘The Diseased Unworthy’, spoke a lot about his character.

‘Thank you, sir. That means a lot, sir.’

He nodded, walking off with a skip in his step to check off his other Jadans. I had to work hard to keep the smile off my face.

After the first hour of morning passed, the street began to fill up with hordes of Noble shoppers. Out of my peripherals I caught them passing back and forth, chirping about the deals of the day. Merchants yelled from their doorways, waving silky dresses and big hats. Women held white umbrellas and wore sun-gowns made of thin fabric that flowed down their legs like water, whilst men wore crisp suits, so white that I almost had to shield my eyes. Sometimes when a Noblewoman got too close I’d catch the intoxicating scent of perfume, and I kept my nose ready for every whiff.

The moustached vendor at the nearest watercart passed out flavoured water to Nobles in exchange for small goods. Most traded food or make-up for the water, but I saw one Nobleman trade away a wooden doll. Fine pieces of woodwork were rare, but some Nobles liked to overpay traders to show off their wealth.

Another Noble habit I’d never understood.

The second bell of the day rang, and then the third, and still no one had chosen me for any errands. I was usually happy keeping to my corner, relaxing in the shade my little overhang offered, but today, idle time allowed my thoughts to wander to the Idea.

I began to sweat, straining towards safer topics.

I’d had the Idea for some time now, but I’d never had the Cold needed to make the particular invention work. Now that I had the three Wisps, my main excuse was gone, and I needed to come up with something else that might dissuade me.

The Crier might turn a blind eye to me having the Cold, but using it for my own benefit would surely be my downfall.

Just then something in the alley across from my corner caught my attention. Most Jadans used the alleyways to get around for errands, and I usually ignored the shadowy movements perforating the lively bustle of Arch Road, but this dark outline was different, as it was keeping completely still. Jadans on errands could get lashes for dawdling, so I tried ignoring the stationary figure at first, but something about the stance resonated with me louder than the morning bells. My curiosity grew stronger than my caution and my eyes began to rise.

A gasp nearly exploded from my chest.

It was the girl. The Upright Girl.

Her posture was like the beginning of a cautionary tale about obeying the Crier’s rules. If any taskmasters caught her standing that still and that straight they’d have the Vicaress break her back in a hundred places and string her crooked body from our road’s namesake Arch.

The girl’s face was perched out of my view, and I had to get a better look, so I chanced raising my head just a nudge.

Long hair flowed down her shoulder in a single braid, knotty yet still nicely sheened. Usually only Domestics wore their hair long, considering it would be torturous out in the streets, catching the heat and bundling it against your head. I couldn’t make out the details of her face, but the sun shed light on her feet, highlighting fresh wounds staining her ankles.

Had she followed me all night and morning? How else could she have found me?

The shout of a passing Noble startled me, and I slammed my eyes back to the ground. When I looked again the girl was retreating, her rigid back slicing into shadow.

Chapter Four (#ua9821b71-b14b-5bae-a084-0f034a16e1de)

The hand fan on the shelf was the exact shade of pink I needed.

I held up the smeared parchment the High Noblewoman had given me, just to make sure, and found the stain of lip grease to be a perfect match.

She was going to squeal with delight.

The handle of the fan was made of ornate pearl, engraved with curling song words. The blade looked to be both sturdy and wonderfully frayed. This had to be one of the nicest pieces in Paphos, and I had visions of Jadanmaster Geb earning commendations for my wonderful find.

I breathed in the air in Mama Jana’s shop, warmer than I remembered.

Most shopkeepers didn’t let us in if the room was chilled, claiming the crushed Cold was wasted on Jadan lungs, but Mama Jana was a good-natured woman who treated me as if I was more than a pair of dirty feet, and I brought her business whenever I could. She was a lowborn Noble – meaning she got the minimal Cold rations delivered from the Pyramid weekly, unlike the bounty bestowed on the Khat’s immediate relatives – and she could use all the trade I could muster.

The shop was unassuming, its entrance deep in the alleyway off Mirza Street, but this modest façade hid a feast for the eyes and the purse, and was the first stop for many Street Jadans. Its walls were concealed by stacks of goods, overlapped in disarray, jumbling together cheap headdresses, thin sandals, fine beadwork and leather waterskins. Often I imagined combing through these mounds with my Claw Staff, its orb sounding to alert me to items pre-dating the Great Drought. In this fantasy, I’d then smuggle the treasures back to my barracks, and take them apart, examining their craftsmanship for hours.

At the front of the shop was an entire area dedicated to the Closed Eye: racks of Closed Eye necklaces, Closed Eye candles, Closed Eye paintings, Closed Eye parasols, Closed Eye robes, and even a full suit of armour with the Closed Eye branded into the chest. There was a giant Closed Eye Khatclock, but its hands were broken and it was kept in the back of the shop. Most Nobles sported the holy symbol somewhere on their bodies, a reminder of the Jadan fate from which they were saved, and a symbol of their closeness to the Crier. I’d never seen Mama Jana wear one, but there was plenty of Cold to be made in religious tradition, so the shop was kept well stocked.

Mama Jana removed the pink fan from the shelf and set it on the glass counter, stretching out her aged back.

‘For this beauty? One Shiver, four Drafts, four Wisps,’ she said, tapping out the different Cold amounts with her brightly painted fingernails as was her habit. I noticed, however, that a few of them were chipped, and that her voice sounded more annoyed than usual. I checked under my feet to make sure I hadn’t dragged in too much sand.

She clucked her tongue, noticing my dismay. ‘How much did the Wisp-Pincher give you?’

‘Sadly the High Noblewoman didn’t give me enough,’ I said, knowing that I had to keep my tone fully respectful for my masters, even in the privacy of Mama Jana’s shop. I let my head sag, holding the lips of the velvet bag open for her to see.

‘One Shiver, five Wisps!’ Mama Jana exclaimed with a dismal shake of her head. ‘And some snooty clod expected a festival piece? Is your High Noblewoman wanting that I should come out and fan her myself? Has the Sun baked her head empty? Why have you brought me this nonsense, Spout? You know better.’

‘Sorry, Mama Jana,’ I said, letting myself bend forward, my heart sinking. The last time I’d found an item this perfect, Jadanmaster Geb had sneaked me a stale crust of bread at midday rations.

I stuffed the greased parchment back into my pocket, figuring I’d have to try Gertrude’s Windmakers instead, even if Gertrude made Jadans stand at her window, offering us half the quality and twice the attitude.

‘Thanks anyway,’ I said, my eyes trailing to the row of lip pipes she had displayed on the counter, making a note to myself to keep an eye out for a chipped pair as a gift for Moussa on my next nocturnal expedition.

I bowed, letting my eyes gloss over the new assortment of belts in the corner. It was always good to know your stock when the Nobles came demanding.

‘Spout,’ she halted me, as I prepared to walk out the door.

I stopped, my ears perking up. ‘Yes, Mama?’

‘What about if I had a job for you,’ she said, tapping her fingernails against the glass counter, giving the fan a wave.

‘Always, Mama Jana.’ I bowed again, stepping forward and holding out my hand for one of her Noble tokens. ‘Let me just finish this errand and I’ll come back and—’

‘I should get priority over some nitwit,’ she said, playfully swiping my hand away with the pink fan. ‘Besides, the job is here. And if you can do it, I’ll give you the fan for what you have in that purse.’

I nodded, keeping my eyebrows from rising. That was quite the deal.

She gave me a long stare and then shuffled over to the door, turning the sign to closed. The beads jangled as she drew the dense gold curtains over the window, shutting out a disappointed Jadan face that had just arrived.

With the only light coming from candles, the place took on a different look. Flickering darkness gave the objects around the shop a mysterious hue that made me believe some Ancient wonders really did live beneath the piles.

She moved to a nearby table stocked with gold-rimmed eyeglasses and ruby-studded crowns. Hunching over, she picked up something cumbersome, straining to bring it over to the counter.

Even in dim light I recognized the contraption immediately.

Cold Bellows.

One of my favourite inventions, and since Mama Jana was drawing attention to it, I had a feeling I knew why the air in the shop no longer tingled.

‘This hunk of beauty is broken,’ she said, gesturing to the space around her, her wrinkled face pinched with annoyance.

I put on a sympathetic expression, although in truth I couldn’t imagine the bliss of working inside a Cold room every day. I’d have given up some of my choicest tinkering fingers to have swapped places for even a few days.

She motioned to a table that was empty except for a thick hammer and a metal screen. ‘I’ve been having to crush Wisps by hand for days now,’ she said, wiggling her fingernails, showing off the cracks in her polish. ‘Dreadful stuff.’

I felt my stomach clench, looking at the door to make sure no taskmasters were trying to peer through the beads. I could get in a lot of trouble if anyone found out I had an affinity for tinkering. In the eyes of the Khatdom, the only thing worse than a disabled Jadan was a Jadan with too much ability.

Mama Jana patted me on the shoulder, her jagged fingernails scratching my skin. ‘Quit your worrying. No one will see you.’

I gave a nervous nod, the sweat beading on my forehead.

‘I’ve kept your secret this far, child.’ Her voice was tender. She spun the crank on top of the Bellows, which offered no resistance, meaning that the machine refused to crush whatever piece of Cold she’d stuck inside. ‘Can you fix it for me?’

‘I don’t know,’ I replied in a small voice. ‘I’ve never even held Cold Bellows before.’

She reached under the counter for her stunning wooden tinker box, which she placed before my eyes, opening its lid to reveal the fine set of iron-handled tools that gleamed in the candlelight.

‘I believe it’s time to change that,’ she said, swatting air over her face with the pink fan. ‘So, do you want to finish your errand or not?’

Back on my corner, I held my arms high and waited, my token in one hand, and the fan in the other. I kept the pink blade extended to block the harsh light of the sky, enjoying a rare moment of complete shade. If any taskmasters gave me trouble about blocking the Sun I could tell them my specific instructions. ‘All Jadans look alike to me,’ the High Noblewoman had told me with a haughty scoff. ‘So do make sure to keep the fan open so I can spot the pink.’

I was happy to oblige.

My limbs still felt shaky after my fingers danced inside the Cold Bellows, a sensation which wouldn’t be going away anytime soon. The fix had been simple enough – just a gear out of alignment – but cracking apart the shell of the machine was like having a conversation with its Inventor himself. When it came to learning from the tinkering minds I usually only got to peek through cracks, all my understanding resulting from such furtive pursuits, and even though it was Mama Jana who now got to enjoy the Bellows, I was the one brimming with gratitude.

I kept my head down and watched the parade of fancy Noble feet pass under my eyes. I spotted shoes with fine glass clasps, shoes with polished leather, shoes decorated with petrified scarabs, and even a large pair I could have sworn had a few Wisps concealed in the heel.

Wisps.

My mind shot back to the Idea. If I could have turned around and slammed my head against the wall to banish the thought, I would have. Pursuing such a thing would be like begging for the Vicaress to pierce my innards with her fiery blade.

As the day passed, Arch Road had become filled with hordes of High Nobles, all looking for ways to rid themselves of their fortunes. Purses swung low with amounts of Cold which could keep my entire barracks alive for weeks. Jadans ran about too, keeping themselves pressed against the city’s walls and alleyways, their errand tokens raised above their heads. The three taskmasters stomping along the end of Arch Road kept their heads constantly raised, looking out for any breaches of Street rules.

Bell four rang out, and right on cue my Noblewoman began approaching. I recognized her by her pudgy ankles that didn’t quite fit into her rare mahogany sandals. That extent of her girth was a sign of status so high I assumed she might be on speaking terms with the Crier himself.

I wanted to puff my chest out with pride, having earned her exactly what she wanted. And not only that, but I’d acquired the fan by doing something I would normally have begged to do.

I could already hear Jadanmaster Geb’s praise in my ears.

Until the strangled feet stopped under my nose, and the legs went stiff.

‘I said red, you little shit! Red! Red! Red!’ the Noblewoman screeched, voice shriller than nails on glass. ‘Red! Are your eyes as worthless as your people?’

I seized up, nearly dropping the fan. My stomach tightened, knowing what I was in for. This was one of those Noblewomen.

‘Taskmaster!’ the woman yelled, spinning side to side, pudge on her neck jiggling. ‘Taskmaster!’

I fumbled in my pocket for the parchment she’d stained with the lip grease, keeping it in my hand for proof. I knew better than to argue, but I could still hope that Jadanmaster Geb would get here before a taskmaster, and see the truth.

Her ankles disappeared further out onto the street, leaving my line of my vision. ‘Taskmasters! Right now! This Jadan has wronged me! Tears to my ancestors, I’ve been wronged!’

I tried to swallow away my fear, but my throat was too dry. Foot traffic in the street slowed as many of the Nobles readied themselves for the entertainment. The jangle of Closed Eye necklaces reached my ears as onlookers held the shut lids in my direction. The three taskmasters began to race down the street, excited to get to play with their whips, but they were all stopped short.

‘May I ask what the problem is, madam?’ Jadanmaster Geb’s green shoes stepped into view.

‘You don’t look like a taskmaster,’ the High Noblewoman said after a pause, a sneer in her voice.

‘Ah. This truism resonates well, as I am a Jadanmaster,’ replied Geb calmly. ‘And I am in efficiency and disciplinary charge of the slaves on Arch Road.’

‘You look more suited to be in charge of pretty sun-dresses.’ She tittered. ‘Although with skin that dark, maybe Jadans do suit you even better.’

‘I can assure you, madam, that I am High Noble. Now again, what seems to be the problem?’ he asked, ignoring both slights. There was a distinct crispness to his tone. Geb was quite adept at recognizing those who threw fits just to stave off boredom.

‘I told it to get me a red one!’ Her words were full of self-righteous pain. It was almost as if I’d stolen her child and tried to raise it as a Jadan. ‘Does that look like red to you?’

Geb’s shoes turned towards me. I couldn’t plead my case, so I made sure to hold the parchment stain-side out.

‘On first viewing of this parchment I find that the stain is clearly pink,’ Geb replied, understanding my intention. ‘And exquisitely matches the colour of the fan. A magnificent find.’

‘I know, but I said—’

‘The stain is decidedly pink,’ Geb repeated calmly. ‘Is this parchment what you gave Spout as a basis for the errand?’

‘I don’t know where it got that!’ The lie was delivered with such force that for a moment even I almost believed her. ‘Now I want punishment. Get me a real taskmaster with a whip!’

The three taskmasters inched their way forward, but Jadanmaster Geb outranked them, and when he gave them a halting raise of his palm, they stopped. He pulled out a piece of parchment that I recognized as a writ of return. ‘I’ll have Spout exchange it at once.’

‘No.’ The High Noblewoman’s feet waddled my way and the fan and token were snatched from my hands. The impatient Sunlight smashed into my face. ‘I don’t have time for that. The ball is at bell six and I need it now. This Jadan leech has wasted two of my Shivers!’ – another lie – ‘And if I have to suffer for its idiocy then so does it. Punishment.’

A pause and a sigh. ‘What is it you wish?’

‘I want him in the Procession.’

Dread flooded through me, making me go weak at the knees.

‘The Procession is only for Jadans who break one of the first three Street rules,’ Jadanmaster Geb said with calm authority. ‘This … infraction doesn’t qualify. How about a more appropriate punishment?’

‘What if I go and find the Vicaress myself?’ she asked, venom in every word.

‘Be my guest,’ Geb said, shrugging so high his shoulders tapped the dangling green earrings. ‘My guess is that she’s at the Pyramid, as per usual. But I imagine she’ll impart similar sentiments to mine, and I wager you’ll be late for your ball.’

‘Fine. Then whippings,’ the High Noblewoman said, delight coating her voice. ‘But beat the water out of it, then. I mean, look at its forehead! Obviously it has too much! Greedy little Jadan leech.’

A whipping was almost tender compared to what Jadans had to endure in the Procession. I was seething with frustration, but I couldn’t help feeling some small relief.

‘How many lashes do you request?’ Geb asked.

‘Until he faints,’ she declared to the street.

The audience seemed satisfied with the request, and I could feel dozens of eyes on me.

‘Is that all?’ Geb asked, unsheathing a punishing rod that was also somehow matching green.

‘Yes.’

‘Fine. You might want to stand back. Look up, Spout,’ Geb commanded in my direction.

I raised my head, fear stiffening the rest of my body. However, his eyes were soft, and he gave me a conspiratorial smile.

‘Arms up,’ he said.

I did as he commanded, hoping he would take it easy on me.

‘Spin.’

I turned around and felt him tugging at my shirt, making it look as if he was fixing something. I could feel the heat of his breath as he leaned in and whispered, ‘Pretend to faint after the first hit.’

He stepped back, and then I heard the rod cut through the air, to land on my shoulder. The blow was quite strong – he had to make it look real – but the pain wasn’t anything I couldn’t handle. I doubted the bruise would be bigger than my thumb, barely even playable in Matty’s shape game. I gasped loud enough for my audience to hear, and then crumpled to the ground, not daring to move.

‘Enjoy your new fan,’ Geb said to the High Noblewoman. ‘Praise be to the Khat.’

‘That’s it?’ she asked, aghast. ‘One hit? No—’

Geb cut her off. ‘You requested until he fainted. He fainted. Praise be to the Khat. I believe we are done here.’

‘But it’s faking! It—’

‘Your words, not mine. Now please, allow me to do my job or I will be submitting a writ of complaint to Lord Suth that a member of his family is interfering with one of the Khat’s Jadanmasters, and by decree six, stanza twelve of the Khat’s law, which prohibits High Nobles from—’

The woman gave a venomous huff, and I heard her heavy feet pad away.

I kept still, trying not to breathe in too much sand from the ground as the rest of the audience dispersed to a chorus of disappointed moans. Soon enough they’d be swept up in the fervour of trading precious Cold for useless goods and forget all about me.

After a few moments, hands swept under my armpits and lifted me up. ‘Thank you, sir,’ I said, as he set me on my corner.

He gave me a firm pat on the shoulder, glaring at the three taskmasters, who were still waiting nearby, just in case. ‘Liars are not beneficial for my operations. As always, you did exemplary, Spout. Perfect shade of pink. Like I imparted, more Jadans like you, smooth as silk through fingers.’

Chapter Five (#ulink_c1bf2a2a-6f38-5fa3-ad60-ef1c30b18b93)

The last of the Street Jadans trickled in, and eventually the sloping right wall of the common area was completely lined. Although most of us had some sort of painful trophy to show from the day, we’d returned in one piece, another shift having survived the Sun.

At the end of the day, Jadans’ mouths were usually too thirsty for small talk, but it never usually stopped Matty from keeping my ears occupied.

‘Hey, Spout,’ he practically shouted.

‘Yeah,’ I said, trying not to move my lips too much for fear of them cracking.

He dug a finger in his ear, shifting his jaw. I wondered if his Jadanmaster had boxed his ears again. ‘Wanna play “whatsit”?’

I nodded. My mind was still racing from tinkering on the Cold Bellows, and in truth I would have loved to ponder quietly on that, but I had sworn to myself long ago that I’d do anything I could to keep Matty happy.

My friend lifted off his shirt and pointed to a series of fresh lashes on his shoulder. I winced, knowing how much they would still sting. As soon as the curfew bells rang and we were allowed off the walls, I would give him as much of the groan salve as he wanted.

‘Whatsit?’ Matty asked.

‘Hmmm.’ I traced the lines on Matty’s back, trying to come up with something good. ‘It’s the three paths that Adam the Wise took through the sands to the Southern Cry Temple.’ I touched the first path. ‘This one is where he had the vision that the Drought was coming.’ I touched the second. ‘This is the one where he found the white fig tree.’

Matty gave a thoughtful nod. ‘Pretty good. I figured it felt like that.’

I took my shirt off next, careful not to rotate my arm too much. I pointed to the bruise on my shoulder that Geb’s rod had given me. ‘Whatsit?’

Matty’s small fingers traced the outline of the bruise. ‘Dwarf camel.’

‘A camel?’ I smirked. ‘That’s all you see?’

Matty shook his head. ‘No. Course not. It’s a camel that carries the Frosts from the Patches to the Pyramid.’

I pretended to wince. ‘That’s one strong camel.’

Matty shook his head. ‘Frosts are almost as light as air.’

I raised an eyebrow. ‘How would you know? Jadans aren’t allowed to touch them.’

‘Because they don’t fall ’smuch as the other Cold,’ Matty said, as though it were obvious. ‘They prolly don’t weigh a lot since they float in the sky so long.’

I chuckled. ‘You might be onto something.’

Matty lifted his chest off the wall so he could look across me to Moussa. ‘Hey, Moussa. Whatsit. Your turn.’

Moussa looked down at his feet, keeping his eyes decidedly off the piece of front wall reserved for the Patch Jadans. ‘I don’t really feel like playing.’

‘What? You didn’t get any marks?’ Matty asked.

Moussa gave a resigned shrug. ‘A few. I just don’t want to play.’

I gave Moussa a light nudge with my elbow. He shook his head, but I countered with a look that asked him to play along. At ten years old, Matty was still young enough to find beauty in such a world, and Moussa and I both knew that sort of innocence was something worth prolonging.

Moussa sighed, lifting off his shirt in a long pull.

Matty’s face dropped. I had to hold back my grimace.

Moussa’s chest was riddled with fresh bruises. It looked as if he’d been tossed down the Khat’s Staircase. Puffy welts wrapped around both sides of his stomach, and from my limited training with Abb, I thought Moussa would have at least one cracked rib.

Jadans weren’t allowed to get off the wall, so instead I turned to the side and placed my hand gently on the back of his neck, pulling his forehead against mine. ‘Sorry, brother.’

Matty had tucked himself back against the wall, his face mortified. Moussa leaned across me so he could give Matty a weak smile, his dry lips cracking. ‘Right, I thought we were playing whatsit? So whatsit?’

I looked over all the bruises, imagining the strength that must have been behind the blows. ‘It’s a song.’

Moussa nodded gently. ‘What song?’

‘We can call it the “Jadan’s Anthem”,’ I said, hoping he’d play into it. ‘It’s about time we had one of our own.’

Matty’s face lifted, a sly grin on his lips.