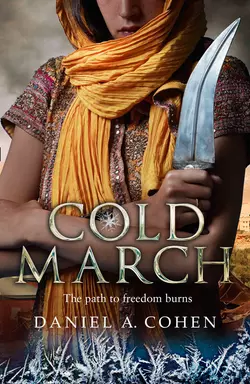

Coldmarch

Daniel A. Cohen

BOOK TWO OF THE COLDMAKER SAGAThe Great Drought began eight hundred years ago when the sins of the Jadans angered the Crier, who ripped their Cold away.Most of the land died. The Khat became nobles. Jadans all became slaves and their warriors disappeared.Until now.Return to a world of endless heat in the sequel to COLDMAKER.Under the burning sun Micah escapes the city he has always called home. His father dead, his mentor slain, his workshop burned to the ground, all he has left are his two closest friends: fellow runaway slave, the fierce Shilah and Cam, the last good noble. They are hunted by the oppressors they dared to challenge.For though they are alone, they are not empty handed. Micah wields a machine that will alter their fiery land forever: an invention of his own making that can create Cold. In a world where rivers boil in their beds and the sky glows red, this changes everything.They must take an ancient, secret path north to the Jadan promised land – to stay ahead of their enemies and to keep their secret safe.But freedom can be costly and unpredictable: once ignited, it spreads like fire.Or Ice.

Copyright (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2018

Copyright © Daniel Cohen 2018

Map © Micaela Alcaino 2018

Cover design and illustration by Stephen Mulcahey © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Daniel Cohen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008207212

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008207229

Version: 2018-09-24

Dedication (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

To my mother

Contents

Cover (#u6643a3db-9603-5e84-82a1-96a77e453781)

Title Page (#u6bdbc5da-a3db-5199-8915-238c1b5786dc)

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Two

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Part Three

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Daniel A. Cohen

About the Publisher

Map (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

PART ONE (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

Chapter One (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

‘Break in.’ Shilah stabbed the shop door with a sweaty finger. ‘I think after what we invented you should have no problem with a lock, Spout.’

I was still in shock and barely able to think, let alone tinker.

News of my father’s death had kicked my heart halfway through my chest. And watching Leroi being consumed by the Vicaress and her army had finished the job. I had a feeling if I turned around quickly enough I’d see a red lump gathering sand and dust on the street, thumping its final beat.

My cleverness was as slow as scorched honey. Despite staring right at one, I’d forgotten how locks even work. Shilah was breathing heavily, her braided hair pasted against her right shoulder with sweat. There used to be a blade hidden in those locks when she’d lived out in the sands, but she’d given that habit up after moving to the Tavor Manor. Something at the back of my mind whispered that a traditional blade would be too big for this job anyway, but I had no access to any other memories that might spur an alternative plan.

‘Spout,’ she said. ‘I know you can do this.’

The dark skin of her face was flushed, thick beads of sweat dripping down her neck and staining the waterskin slung over her chest. After getting used to the comfort of Leroi’s tinkershop, I think both of our bodies had forgotten how deeply the sky could bite.

Shilah, Cam, and I had somehow avoided the Vicaress, fleeing through the empty sands and making it to the centre of Paphos without getting caught. The hour was too early for the Street Jadans to be racing towards their corners, which meant only the eyes of the sky were upon us.

The enemy wasn’t far behind and was quickly gaining ground. Shouts and commands flooded the nearby streets and echoed down the alleyways.

‘I don’t want’ – heave – ‘to rush you, Spout.’ Cam’s words were mostly wheeze, pitched up and squeezed. ‘But I think I hear’ – heave – ‘them coming.’

If Shilah appeared overheated, then Cam was roasted and ready to serve. Unkempt yellow hair was brightly contrasted against the red of his face, making him look as if he’d been hanging upside down all night, his blood gathered in his delicate Noble cheeks. He’d somehow managed to maintain his gold-rimmed glasses, but despite his best efforts, they kept sliding down his nose, his skin as slick as Ice.

Shouting from the pursuers became more barbed as the taskmasters closed in. The Vicaress and her forces had been at our heels since our narrow escape from the Tavor gardens, where Cam’s father nearly had us cornered. If not for Leroi’s heroics, I imagine we would currently be strung up from the Manor gates, awaiting judgement.

Touching a Frost is punishable by death.

We didn’t just touch one.

We stole a Frost and used it to create an invention that could shatter the entire Khatdom. We discovered a secret that could save my people.

My mind felt gummed and cloudy, the lock impenetrable.

Our only stroke of luck so far was that my years of serving as a Street Jadan meant I still knew the best passages through the city, and I had been able to lead our group down a secret route that had been somewhat abrasive. Cam’s sunshirt was ripped in a hundred different places from the constant squeezing against tight bricks, and Shilah still had clay dust in her bristly hair from the roof of the Bathing Quarters Cry Temple. We were still in one piece, but time was running thin.

I cracked my knuckles, trying to figure out a way to pick myself out of the mental rubbish. My throat was parched and burning from the long run, most of which I didn’t recall. One moment I’d been watching Leroi battle the Vicaress with his explosive powders, the gardens of my new home consumed by fire, and then I was stumbling through the Paphos alleyways with the two most important people in the World Cried. It was Shilah’s idea to go to Mama Jana’s, as I had been in no state to form a plan. Neither had Cam. Little Langria had been burned to ash, and we couldn’t go back to my old barracks, so when Shilah suggested Mama Jana’s shop we didn’t argue. Hiding within her unkempt piles of treasures felt like the only place in Paphos that made sense.

If we could break in.

Shilah was right; besting the lock should have been a breeze. I’d been apprenticing under a master inventor for quite some time, and this should have been as easy as breaking a Khatnut with a giant hammer. But keeping focus was impossible, as my head was ringing from explosions and visions of a stolen future.

‘I don’t have any tools,’ I said calmly, patting my empty pockets for effect. ‘I don’t have anything. The supply bags. I don’t know—’

‘Spout, why aren’t you’ – heave – ‘freaking out?’ Cam asked, swallowing hard. ‘I hear them on the next street over.’

I twitched my lips back and forth, barely listening to him. The lock was baiting me, the metal blinding in the heavy light of day. I used to play with them, manipulate them, learn their secrets. Broken locks were a common find in the boilweed piles of my youth. I slowly rubbed the back of my hands, trying to remember what tricks they used to hold.

Shilah grabbed the side of my face. Her palms were slick with sweat and slipped along my cheek before taking hold. ‘We just made the greatest invention in the World Cried, dammit. You once talked with the Crier himself. You can break this stupid lock in your sleep, so don’t go losing yourself, Micah. I’m right here.’

I blinked, everything suddenly becoming more real.

Every line in her face was defined. I could see the tightness of the muscles underneath her skin, the veins in her neck standing up and strained. I could make out each individual rivulet in her braid. Her almond eyes were boring into me, drawing me home.

The shouting and sounds of whips against stone were getting closer, the taskmasters trying to flush us out of hiding. We needed to get inside now.

I took a deep breath and tried not to picture Leroi drowning in all that black smoke. I could still feel his sad eyes on us in the tunnel, presumably knowing the battle that awaited him on the other side of the door. I could still smell the crackling fire on my shirt.

A snap of Shilah’s fingers and a quick gesture reminded me that the Coldmaker was still by my side. We still had the machine.

‘This is bigger than us now,’ Shilah said. ‘And you’re not alone. I’m right here.’

Cam cleared his throat, checking over his shoulder. ‘Me too.’

I nodded. The streets themselves had once given me all the tools I needed. I used to trust that the Crier would provide.

So why did he keep taking away?

‘Keep watch,’ I said, gritting my teeth and balling my fists. I shifted myself into the shadows of the alleyway next to the shop, headed towards the boilweed piles. Almost immediately I spotted a trove of sunclocks, broken parasols, and a large pair of Cold Bellows that I’d once fixed for Mama Jana a while back. She didn’t used to have that much rubbish lying around in her alley, but I was guessing since I’d moved to the Tavor Manor, she was no longer able to salvage her broken goods.

Junked items sat piled up and dusted with morning sand, waiting to be plundered. Under any other circumstances I would have smiled at the notion that Mama Jana actually needed a Jadan like me, but right now I had no capacity for nostalgia. Emotions were only distractions. I did allow logic to surface, and almost instantly I spotted what I needed. Dropping to my knees, I snatched two skinny metal rods from a broken parasol, originally used to keep the shredded fabric splayed.

As I launched back towards the alley, something green and swirling on the wall made me stop. I couldn’t quite make out the symbol, but I already knew what the design would be.

The Opened Eye had been painted in that exact same spot once before.

I stopped just long enough to draw my fingers across the pupil.

The Open Eye was the symbol for Langria, the only place in the whole World Cried where my invention would be safe, as North as North goes. It was the land where truth rained from the heavens, and the Jadan people had all the Cold they’d ever need to remain free. The gardens there were more lush than anything the Nobles could dream of, with forests of sugar cane miles wide, and enough lush fig trees to feed everyone in Paphos. There were troupes of animals that hadn’t been seen since the Great Drought, and even such ancient things as birds. It was a haven for our lost culture, and songs and fruit were of equal abundance. I’d even heard the Langria river waters were cool enough to dive right into. Langria was hope itself, and seeing the symbol painted on the wall gave me enough to hold my tools high as I rounded the front door.

‘You think those will work?’ Cam asked, his nerves apparent. Wide eyes and a haunted look made him seem as good as Jadan at this point.

‘Yes,’ I said, shimmying the two small rods inside the hole of the lock and feeling for the pins. ‘I just have to …’

Loud orders were barked so close that I could almost smell the burning oil on the Vicaress’s blade. Either the Vicaress had a vision of our plan to go to Mama Jana’s – which seemed highly unlikely, considering she was a fraud – or she had gathered more of her army, flooding the streets.

‘Hurry,’ Cam pleaded, sucking down a swig from the waterskin slung across his chest. ‘Not that I’m rushing you.’

Shilah turned and gave him a stern look. ‘Save that water, it’s all you have.’

I closed my eyes and tried to recall how metal could serve as an extension of my fingertips. Leroi often told me a true Inventor’s reach could be measured only in imagination.

He was dead now.

My hands were shaking with fear and adrenaline. The metal rods felt like greased needles trying to stab a single grain of sand.

‘I can’t,’ I said, getting frustrated. The cloud had parted enough to let me remember that Mama Jana’s lock was a snap-pin set-up, which meant the pins needed to be lifted at once. My flailing fingers were only making things more futile. The knowledge alone of how the lock worked was not enough to steady my grip. ‘I can’t feel anything.’

Shilah reached down and placed a hand on my lower back. ‘What do you need from me?’

Cam was muttering to himself under his breath, his father’s name appearing no less than three times within the murmurs.

‘You can make it work,’ Shilah said, matching my calm. It was as if we were back on our cots, taking turns telling stories as the night waned. Back then, safe in the womb of the tinkershop, I’d never thought we’d be on the run, protecting one of the most important discoveries in the history of the Jadan people.

I tried to feel for the pins in the lock again, closing my eyes this time, but the answers wouldn’t reveal themselves. Over and over the proper technique slipped my touch, and I finally pounded my hand against the door out of frustration, a shock of pain ricocheting down my arm.

Shilah shot me a disappointed look, but the slamming noise had been drowned out by the blaring of a distinctive horn.

Three long blows.

Followed by two short.

And three more long.

I hadn’t heard that call in years, and even then it had been faint, sounded from the outskirts of the city. It was a harbinger of death. There was a reason why the noise was rare – important Jadan runaways were quite uncommon – but every once in a while a favoured Jadan Domestic would choose baking to death in the sands over what waited back at the Manor.

That’s when the beasts were sent hunting.

‘Shivers and Frosts!’ Cam exclaimed, eyes flitting around, almost as if he could see the echoes of the horn bouncing off the walls. ‘Is that what I think it is?’

Shilah’s eyes darkened, her chest rising and falling quickly. I didn’t blame her. Torture under the Vicaress would be bad enough, but getting stalked down and eaten alive would be another level of agony entirely.

‘The Khat’s hounds,’ I said, my hands shaking like loose boilweed in the wind. The needles clacked uselessly in the lock.

Cam swallowed hard. ‘Sun damn.’

‘You know about the hounds?’ Shilah asked him with a snarl. ‘You’ve seen what they can do up close?’

Cam wilted, taking his glasses off and closing his eyes. ‘He doesn’t let … I’ve only seen the ones he keeps in his chambers. But they’re small and harmless and … fuzzy. Just relics from before the Great Drought.’

‘Those runts are not his hounds,’ Shilah said, her voice breaking for what felt like the first time. She absently touched her throat, her arms flexing so fast that I wondered if she might try punching the door down. At this point that might have been more effective than my trembling hands. ‘The Khat keeps his real hounds in the basement of the Pyramid,’ she said between clenched teeth. ‘He starves them for days on end. And when he does feed them … guess what he uses for the meal?’

‘I’ve heard.’ Cam’s face went so red he might as well have smeared Khatberries on his cheeks. ‘But you have to remember. I have nothing to do with the Khat.’

‘Other than your name and blood.’

‘I’m only heir to the Tavors,’ Cam said, not meeting her eyes and changing the subject fast. ‘Keep trying, Spout. Please.’

‘Why did the Crier take us this far?’ I asked. The words came out lifeless, and I wondered who this stranger was using my voice. ‘Only to let us get caught. Why would he be so cruel?’

The taskmasters’ shouts were almost on top of us.

‘Spout,’ Shilah said, guiding my chin sideways with her finger, forcing me to meet her eyes. ‘Don’t worry about the Crier. I have faith in you.’

I followed the sweat beading off her face, which dropped quickly and flecked the stone at my feet.

Splashing up an idea.

I set the thin metal picks on the ground.

‘What are you doing?’ Cam gasped, hands pulling at his yellow hair. ‘Maybe let’s just go find a shop that’s actually open, and hide there?’

‘No one leaves their doors unlocked,’ I said, returning to the alley, not looking at the Opened Eye as I passed. Cam softly called after me, but before he could repeat my name I’d returned with a sharp slice of glass from the pile of trash.

‘Tears above, Micah. Are you going to try to fight the hounds?’ Cam asked frantically. I’d never seen him so worked up.

Grabbing an Abb from the bag, I sliced off a tiny golden sliver, small enough to fit under the pins in the lock. Shoving it deep into the hole with the help of a parasol needle, I gestured for Shilah to give over her waterskin. Her lips opened in the shape of a question, but after a moment her eyes lit up with recognition.

‘Do it,’ she said with a smirk.

‘Do what?’ Cam asked.

Shilah licked her cracked lips. ‘Ice. He’s going to open it with Ice.’

Cam paused, looking as though the two halves of his body were trying to flee in opposite directions. ‘How? What if the lock just breaks off? Or we get blocked out completely?’ I could feel the buzz of fear in his words. ‘This can’t be the best idea.’

A harsh voice shouted from the street next to ours. ‘Two of you go high and the rest of you lot go around! Check the rooftops and alleyway!’

Blood shot into Cam’s cheeks, the sunburn there appearing even more raw. ‘Do it.’

I nodded, holding up the waterskin to the lock and letting out a trickle of water.

Cam manoeuvred his hand to the bag on my shoulder, digging into the cloth and putting his palm directly on the bronze lid of the Coldmaker. He closed his eyes and muttered something under his breath.

The sound of Ice expanding rapidly crackled in my ears. I wanted to watch the beautiful crystals unfold, but mostly I just hoped the reaction would push all the spring-loaded pins up enough to trigger the lock. I had no idea how much force it gave or how fast it worked. Our lives depended on something I knew almost nothing about.

If the Crier really was watching, then this was his moment to do something.

Metal clicked, and the door opened a squeeze. A small peg of Ice jutted out of the lock, but hopefully it wasn’t enough to be noticed by any taskmasters.

Shilah grabbed both Cam and I by the shoulders and tossed us inside, just as the next round of horn blasts split the air.

Chapter Two (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

I barred the door, threw down the shades, closed the curtain of beads, and dragged the nearest cabinet in front of the entrance, sliding it flush against the door. Closed Eye necklaces jangled on the shelves, and if someone pushed their way inside, the resulting crash would at least let us know we needed to find cover.

My pulse was in a frenzy knowing the Khat’s hounds were charging into the city.

The stories said that Sun blinded the hounds to teach them pain, leaving them to stalk their prey entirely by smell. And the stories said a lot more than that too. The hounds were supposed to have breath like hot fire, and fangs as long as any rattler, and could smell a specific Jadan body even lying in the dunes.

Sometimes back in my barracks, Levi would get hold of sour ale, and would tell the Jadan children about the other things that lived in the catacombs of the Khat’s Pyramid. Things worse than hounds, that didn’t need to smell you. They already knew you. Things that saw only through Closed Eyes, slithering in silence. Without warning. Without mercy. To drag you into the black.

I stepped away from our feeble defence of an unlocked door and single cabinet, knowing it would be all but useless against such foul beasts if they caught our scent. If only I had my old Stinger, powered by the scorpion venom I used to extract. If I’d only been able to get my hands on some of that explosive power Leroi had used to demolish the Tavor gardens, we might have stood a chance.

I tried to force a real idea that might save us, but I came up empty. Mama Jana didn’t sell weapons. Nothing that we could fight an army with. I glanced around at all the Closed Eye fashion pieces displayed on the racks: reminders that Jadans deserve to be oppressed, that the Crier himself condemned us when he took away my people’s Cold. As if eight hundred years of Drought wasn’t bad enough, we were supposed to cower constantly to the fact that it was our fault.

I had recently stopped believing a word of those old stories, but my father and Leroi were now both dead. In my mind there was no worse punishment than that, except maybe also losing the two friends at my side. The enemy was coming: my mind had to make that a reality.

Shilah’s eyes narrowed and swept the edges of the shop.

Cam stood over a basket of figs on the glass counter. Already a handful deep, he groaned with relief, digging into the food with the kind of reckless hunger that I’d only ever seen in Jadans starving in the streets.

It was odd to think that all of us, Nobles included, were just a few meals away from such desperation.

‘It’s not stealing,’ Cam said sheepishly, noticing that I was watching. His cheeks were puffed with fruit pulp, leaving his words hard to discern. ‘It’s survival. I’ll pay Mama Jana back when I can. She knows I’m good for it.’

‘I don’t think your people are capable of seeing it that way,’ Shilah said after a pause, her eyes still scanning the floors. ‘Plenty of Jadans have been killed for taking less than figs.’

‘Stop saying my people,’ Cam said, a seed bursting out and sticking to his bottom lip. He gestured around him, arms waving wildly, almost knocking over a can of Closed Eye badges. ‘Am I not here with you? Did I not sacrifice everything for our cause?’

For once Shilah looked to be at a loss for words, but I could see her wheels turning even from the thick of the shadows.

I reached up and touched my forehead. There should have been sweat.

‘What exactly are you looking for?’ I asked her.

‘It’s a long shot,’ she answered, still focused.

‘We need to find a hiding place until Mama Jana gets here,’ I said. ‘The Pyramid is not that far away, and the hounds are supposed to be fast.’

‘I swear,’ Cam said, flustered. He wouldn’t look anywhere other than the figs. ‘I’ve only ever seen the little hounds. And they can fit on your lap.’

‘That reminds me,’ Shilah said, stripping down to her undergarments on the spot. She was quick and efficient in disrobing, which in no way should have been arousing, yet I could feel Cam and I both seizing up at the unexpected sight. Bare skin wasn’t taboo for Jadans – our barracks were always stifling, making clothing a burden – but Shilah’s body was toned and lean, and even her intense scarring was attractive in its own right.

She was a warrior. Straight out of the days before the Great Drought, when it was still possible to battle your oppressors. Once it was decided that the Jadans were unworthy of Cold, the warriors disappeared.

You can’t fight the Crier’s will.

Cam audibly gasped, averting his eyes – although he didn’t stop chewing the figs. The room was shadowy enough that we were all mostly silhouettes anyway, but Shilah’s figure was uncomfortably striking, more woman than girl, the curvy areas accentuated by the glistening sweat. I looked away as my lips recalled the passionate kiss Shilah and I had shared after discovering the secret of the Coldmaker. I didn’t want to complicate an already dangerous situation with stirrings that only ever made young men like me lose focus.

‘I thought you were this great lover of women, Camlish,’ Shilah said with a snort, reaching for a yellow sundress on a rack and tossing it over herself, the bottom hem getting caught on her thick hair. ‘Romancer for the ages. I wouldn’t think you’d get shy around a little skin.’

‘I— well you—’ Cam turned away further. ‘You deserve respect is all.’

Even though her skin was darkened to a fine mahogany by the Sun, the Noble dress seemed to fit Shilah in more ways than one. At first glance I wouldn’t have been able to distinguish her from the kind of girl that dress was intended for. Her back was straight and sharp, regal in bearing.

‘You two do the same,’ Shilah commanded the both of us.

‘I’m already in noblewear,’ Cam said, finally turning back, threading a finger through one of the many gashes in his sunshirt, wiggling it against his stomach. ‘Ripped and nasty noblewear, I guess.’

Shilah grabbed two handsome sets of sun-robes from a display drawer, tossing one to Cam and one to me. ‘We change for the smell. That’s how the hounds find you.’

‘Aren’t we going to smell like us either way?’ Cam asked.

He was right. New clothes probably weren’t enough to mask us from the beasts. My stomach growled watching Cam scarf down all that food, but I was also used to hunger, and my body could wait.

Shilah began to examine the perimeter of the store, and I quickly changed into the sun-robes, the silk fabric pulling against my sticky skin. Hopping around Mama Jana’s main counter, I heard another horn call sounding outside, baiting the hounds. The noise was closer this time, but at least we were safe for the moment.

‘Not sure if this will be enough, but …’ I let my fingers peruse the biggest drawer. At first all I found were slips of parchment stained with writing I couldn’t understand and small clay urns.

Finally, the object I was looking for rolled into my palm.

I shook the glass perfume vial and glared up at the roof.

I always associated rosemusk with Mama Jana. ‘Fashion for the nose,’ she always said when applying the scent from this very bottle. She usually tipped out a dose or two whenever I was fixing things in the shop, and I knew it overpowered even the most obnoxious smells. I sometimes had to come straight to Mama Jana’s after performing rather unseemly tasks for other Nobles – Street Jadans didn’t get to pick the order of our errands – like cleaning up vomit from the alleys of the Imbiberies, or struggling to carry lumps of spoiled firefish out to the dunes. On times like those Mama Jana would leave the whole bottle of rosemusk out, uncorked. I think the gesture wasn’t so much for her as it was for me, however, as she never wrinkled her nose at the foul odours clinging to my slave uniform, and she often left the open bottle next to whatever item I was tasked to fix.

‘You think she has cool water somewhere too?’ Cam asked, looking into his waterskin with complete dismay. The temperature inside the room was stifling, but I knew Mama Jana had a store of water and Wisps under her nail-colouring kit. What I didn’t know was how soon the hounds might arrive to gnaw on our bones.

‘We should probably do this first.’ I unscrewed the rosemusk cap.

Cam nodded, tossing his ruined shirt onto the ground and snatching up the garment Shilah had passed him. It was a formal green silk robe that was far too big, the embroidered bottom billowing around his knees.

I raised an eyebrow.

‘This is no time for fashion,’ Shilah said. ‘Pour.’

I sent a stream of perfume down the back of Cam’s neck. His nose scrunched with a grimace, the scent overpowering. I dabbed my fingers on the watery puddle, and spread it down over his arms. The hairs lining his wrists were so fine they were nearly invisible, yellow and thin. As I was rubbing, I noticed how sunburned the backs of his hands had become, and I tried to remember if Mama Jana had any groan salve. His jaw went tense as I smeared around the wounds, and I could tell he was trying not to wince.

Shilah marched over and gave me a nod, Cam slipping back behind the counter. My fingers trembled as I tipped a thin stream of the rosemusk down the back of her dress, trying not to think of all that creamy brown skin. The perfume fell across her skin quickly because her back was so razor straight.

‘More,’ she said, her face as serious as stone. ‘And rub my arms too, if you don’t mind.’

I swallowed hard, seeing and feeling her flesh under my hands. As I spread the bright scent on her arms I could feel her radiating heat, and I could make out the individual clusters of freckles around her elbows. Her skin was rough with scars, sending a jolt through my heart, my movements nervous and jerky. The flaws in her skin made the liquid less easy to spread, and so I had to take my time, making sure I covered everything evenly.

‘Do my back too,’ she said without any hint of embarrassment, lifting her dress and revealing her muscled stomach.

Cam looked away, occupying himself by sifting through the rest of Mama Jana’s shelves, his voice more pinched than when our lives had been in danger. ‘Surely there must be a few Wisps lying around.’

‘We don’t need Wisps,’ Shilah said with a hint of a smile, looking at my hands and then at my face. ‘We have Ice now.’

Cam gave a nod of consent, keeping his eyes on the inside of the drawers. ‘You’re right, but it probably wouldn’t hurt to have some with us. So we don’t raise suspicion all the time.’

His words trailed to a murmur as he pulled out a stack of books. A little blue tome in the middle caught my attention, looking about as old as the Khatdom itself. The writing on the spine was white and languid, and also somehow … familiar? I couldn’t quite make out the design in the dim light. I also quickly lost interest, as Shilah had just taken my hands and moved it to her naked lower back.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘Where the sweat gathers.’

I reapplied the perfume and began spreading it across her skin, trying not to linger at the dimples studding her backside. I allowed my fingers to move slowly, nearly forgetting about the hungry creatures clamouring for our blood. Shilah leaned into my touch and time slowed to a crawl – which was most welcome, as every breath had the possibility of being my last.

‘And my hair, too,’ she said.

I dabbed the rosemusk into her locks, making sure to massage her scalp. Her head rolled along with my touch. All of a sudden her eyes flicked over, boring into mine with strong passion.

‘We can change things,’ she whispered. ‘We have to change things. Look at how far we’ve come.’

I nodded. ‘But the hounds—’

She took my hand in hers, gripping tightly. ‘Are nothing. We made the Coldmaker. We’re going to get through this together.’

I saw that my fingers had dried faster than I would have liked, and so Shilah spun me around and emptied the bottle, holding me still with one hand and spreading the perfume evenly with the other. Wherever her fingers traced I felt life blossom, and I was suddenly aware that the room had filled with the potency of a hundred gardens.

Shilah’s hand lingered on my forearm as she put the empty bottle down, her voice going back to normal volume. ‘Now let’s just hope all the perfume doesn’t attract suspicion from outside, then—’

‘Not you!’ a voice groaned from the back of the shop. ‘Curse this whole Sun-damned land, not you, Spout.’

All three of us spun around to watch the figure sweeping her way out of the dark. It couldn’t have been Mama Jana, however, as the shopkeeper I knew was always meticulously maintained, not a grey hair out of place. The approaching figure was dressed as poorly as the dead-cart Jadans, with dirt smeared all over her face and more rips in her clothes than Cam. Her hair was the same shade of grey as the real Mama Jana, but it was frayed like a broomstick. Heavy shadows tugged at her eyes. She wandered through a beam of light seeping in from the space beneath the closed window, revealing the face of the kind Noblewoman I once knew. I couldn’t fathom what sort of darkness must have devoured her and left this hag in its wake.

‘Not you,’ Mama Jana said again, dropping the knife in her hand. ‘You were supposed to be safe.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, tucking my chin to my chest in shame.

Cam looked shocked. ‘Mama Jana! Were you sleeping somewhere back there?’

Mama Jana walked right up to Cam and poked him in the chest, her fingernails broken and chipped. For the first time since I’d known her, the nails weren’t painted any particular colour, which was even further cause for worry.

‘You were supposed to take the boy back to the Manor, Camlish,’ she snarled. ‘You were going to keep him safe.’

‘I did,’ Cam said, backing away, keeping his eyes off the fig basket. He nearly stumbled over a wooden chest trying to find reprieve from her gaze. ‘I tried. But you don’t understand—’

The next horn blast from outside was muffled, but distinct.

Closer.

‘What happened, Camlish?’ Mama Jana asked, tears forming in the corners of her eyes. ‘Why the hounds, and why are you wearing a girl’s Paphesian flutter-dress?’

Cam glanced down at his shirt with a hearty frown. ‘Is that what this is? They just looked like regular robes to me …’

‘We need your help,’ Shilah said, stepping in between them, standing tall.

Mama Jana gave Shilah a fleeting look and then did a double-take. Her eyes widened, the streaks of dirt making her aged face look demonic. ‘Aren’t you Veronica’s daugh—’

‘We’re in danger,’ Shilah said. ‘Can you hide us? Please. I heard you used to be a Marcheye. That’s why I brought us here.’

I cocked my head. A Marcheye?

‘Your mother told you about that?’ Mama Jana asked, mouth gaping. ‘But you’re too young for the ceremonies. And besides, it was shut down ten years ago.’

Shilah stood rod straight, her eyes flitting around the room, almost as if ignoring the Noblewoman standing in front of her.

‘And you said nothing to anyone?’ Mama Jana asked, lump visibly forming in her fleshy throat. ‘You didn’t try the March, did you?’

‘Nothing,’ Shilah said, puffing further with pride. ‘No.’

‘Mama Jana,’ I said, giving the shopkeeper a respectful bow. She seemed smaller and more hunched than I remembered. ‘I’m sorry that we came here and burdened you. But we have good reason. We—’

And then a pang in my chest, seizing my words.

‘What is it, child?’ Mama Jana asked, looking me over with concern.

I shook my head, unable to speak over the rebounding emptiness.

Shilah gave me a concerned glance and then picked up where I had left off. ‘We discovered something that’s going to change the whole World Cried.’

‘Please help us,’ Cam added, bowing, which was something the High Nobles never did for the lowborn Nobles. ‘It will pay you back for the figs a hundredfold.’

‘Oh, I don’t give a beetleskin about the figs, Camlish!’ Mama Jana was nearly snarling. ‘You were supposed to keep him safe!’

I was about to grab the Coldmaker out of my bag and show Mama Jana, but she waved me still and quiet.

‘No more talking,’ she said, navigating the dark shop as easily as a whip snapping through open air. ‘No more talking until we get down to the chamber. The hounds can hear almost as well as they can smell.’

Mama Jana’s shop only had the one level. I’d been there dozens of times and never noticed any stairs or hidden doors. There was no chamber.

Mama Jana grabbed one of her fancy canvas bags and began stuffing our soiled clothes away, staining the inside with our sweat and dirt and sand. ‘It was a smart idea to change clothes and scents, Spout. I’d expect nothing less from you, but it’s not enough. You need to be away from here.’

I went to open my mouth, but her glare could have cooked clay to brick.

‘No talking,’ she spat, her eyes flicking over to the drawer where I’d discovered the rosemusk and clay urns. ‘I mean it.’

She grabbed our clothes bag that must have stunk like a taskmaster’s armpit and gestured for us to follow her to the back of the shop. Keeping the Coldmaker tight against my side, I followed through the darkness, the pungent smell of flowers clinging to us.

Mama Jana stopped at her giant Khatclock with the Closed Eye for a face. Even though the huge timekeeper was a beautiful display of craftsmanship, I’d never paid it much mind. Besides the giant timepiece being a looming symbol of Jadan inferiority, it was also broken, its two hands forever stiff. The Khatclock only ever pointed in one direction, straight up. Mama Jana had never asked me to take a look inside the machine to see if I could get the gears and cogs working, and so I’d never offered.

‘Wait here,’ she said, eyes already planning her route back through the dark shop. She threw the bag of soiled clothes at Cam’s feet. ‘And say nothing.’

I gave my friends a confused look, which was returned by a helpless shrug from Cam, and a perplexing smile from Shilah.

Mama Jana careened around the room gathering things with the swiftness of a wraith. Darkness nor clutter were able to stop her. She gathered clothes, waterskins, velvet bags of Cold, assorted vials, and a compass. Last she grabbed the half-empty basket of figs, balancing it in the palm of her hand. Another series of horn blasts sounded outside and my stomach seized up.

I ran my fingers against the smooth bronze metal of the Coldmaker, my nails scraping along the engraved Opened Eye I’d carved with a hammer and chisel. The machine was small enough to fit in my arms, but still quite heavy, as it was made mostly of dense bronze. It also walled in a whole Frost, and was filled with salt water, two of the main components that made the invention work. Jadan tears were dropped onto the Frost inside, which caused a visceral reaction at the catch-point. I didn’t know exactly why it worked that way, but the machine’s presence bestowed me with strength and kept me from having a breakdown; so even if it weighed more than a whole caravan cart, I would have found a way to keep it by my side.

Mama Jana reappeared as fast as she had gone, shoving the basket of figs into Cam’s hands and the bags of supplies into mine. ‘Free of charge. My first flock in so long.’

‘Mama Jana, what’s—’

She put a hand to her lips, cutting me off and giving me a stern look. ‘No. Talking.’

I nodded, hearing every rapid beat of my heart in my ears. Shilah looked far too calm considering the circumstances, as if none of this surprised her. Cam at least looked as lost as I did, as he was drenched in sweat, and squirming with a hand over his stomach as if he was about to spew.

Mama Jana pulled back the glass face of the Khatclock and took hold of the spindly hands. Before doing anything else, she gave me a look, as though she’d been waiting on this moment for some time.

‘North.’ Mama Jana nodded, and then spun the hands one full rotation. ‘The March is always North.’

As the Khatclock’s hands completed their circle, the entire Closed Eye face opened with a faint click, revealing a startling display of strange writing beneath the mechanical lid. The whole clock swung forwards, revealing a hidden hole that was lit faintly by a distant flickering light. The dark corridor led to descending stairs not unlike the ones in Leroi’s study, and brought with it a frightful sense of dread, reminding me what had happened last time we took one of these secret passageways.

Mama Jana put a hand on my back and gently nudged me along, handing me the soiled clothes to take with us. ‘Go, children. I’ll seal you in and hold them off as long as I can. It’s airtight, so those foul beasts shouldn’t be able to smell you. Remember, the March is always North. Follow the signs, and when you get to the shack, ask for Split the Pedlar. He probably won’t answer to Shepherd any more. Now, hurry!’

I went to spin around, but Mama Jana’s arms were stronger than I remembered. ‘Wait, what March?’

‘The Coldmarch,’ she said, glancing over her shoulder at the front door.

Cam gasped, sucking in a breath so fast he almost choked. ‘It’s real?’

Mama Jana licked her cracked lips, her eyes feverish and crazed. ‘It used to be real. And I guess it is again. Now take these words with you if you can. Hold on. Okay, let me remember. Shemma hares lah …’ She stopped, her tongue rolling on the roof of her mouth, struggling to find the next part. ‘Shemma hares lahyim her— no, that’s not it.’ She flexed her gnarled hands with frustration. ‘It’s been a while. Let me get the Book of the March.’

I clutched the Coldmaker more tightly against my side and offered: ‘Shemma hares lahyim criyah Meshua ris yim slochim.’

From the look of shock, I thought Mama Jana was about to faint.

‘My father told them to me,’ I explained.

The sharp memories of Abb made me bite down on my tongue, and I might have drawn blood.

Mama Jana composed herself with a sigh, but her words moved quickly. ‘Fitting for such a name. Now go. There’s still a lantern burning, and candles. Take the lantern with you, you’ll need it. Move with caution as there are certain dangers down there. Eat the lizards if you must. You’ll find water eventually. What am I forgetting? Hmm. I was just down there … don’t stop, even if you hear my voice behind you …’ The circles under her eyes deepened. ‘I’ve not broken yet, but the Vicaress has certain ways.’

‘The Coldmarch is real,’ Cam said to himself, looking quite flustered. ‘I can’t believe it. My father always said “If the Khat can’t find it, it’s not real.”’

Mama Jana said nothing, just made another shooing motion, brushing us towards the dark.

I rifled through my bag until I found one of the loose Abbs, handing it over.

She took the Abb gently, holding it up against the bit of light trickling in from the passageway. ‘What it is, Spout?’

‘Put a slice of it in water and tell as many people as you can,’ I said, keeping my voice hushed so she wouldn’t yell at me.

Mama Jana gave me a curious look, but the horn calls were explosive now, even through the walls of the shop. She finally brushed us through the threshold and swung the Khatclock back in place, sealing us away.

Chapter Three (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

Grabbing the lantern from the bottom of the stairs, I lifted it high so we might get our bearings. Glancing back at the Khatclock, I found the space now to be one solid wall, not even a single crack where a horn or a shout might pass through. I knew there had to be a way to slip back into the shop, but I found no sign of a knob or release, and from Mama Jana’s tone it didn’t sound like she intended for us even to try.

Spinning around, I let the light shine down the empty corridor that stretched deep into the earth. The passageway was wide enough to accommodate us if we walked in single file, the walls so smooth they almost looked wet. The air tasted strange in my mouth, and not just because of our collective rosemusk bath. I smacked my dry lips. The air was so much cooler than back up in the shop, but I saw nothing in the way of Cold Bellows. The temperature must have been natural.

The passage took a sharp turn left after about ten paces, cutting off sight to whatever lay beyond.

Cam put his forehead against the clay wall, closing his eyes and taking a moment before speaking. ‘It’s real. I knew it.’

‘You know what this place is?’ I asked, feeling rather childish as nightmare images jumped into my mind. I knew I should be thanking the Crier for the incredibly fortunate fact that Mama Jana had a passageway out of her shop, but ever since childhood I’d been bombarded with stories of haunted holes and cracks in the land. Places where the unforgiving spirits lived, bottled up and angry.

Beneath the ground was where the foul creatures lurked, plotting how they might make it up to the surface where they could partner with Sun and do his bidding. Sobek lizards and sand-vipers would be the least of our problems down here, and a part of me wondered if it would be better to take our chances with the hounds.

Cam kept his head pressed against the wall, but looked at me with a small tear dotting the corner of his eye beneath his glasses. His face was still blood red from exhaustion, but at least he was smiling. ‘I mean, I knew it was real, and you did invent a miracle. And my father really is a monster, but this proves everything once and for all. I would go back to the library and burn all those paintings and—’

‘Cam, stop babbling and talk to me,’ I said carefully.

Lifting himself away from the wall, I thought he might start dancing. He threw his arms wide. ‘Spout, you’re going to change Sun-damned EVERYTHING! And I get to help you!’

‘Keep it down, idiot,’ Shilah snapped at him, pointing to the door.

Cam gave an embarrassed nod, his chest rising and falling with incredible speed.

‘I would have thought you were a true believer when you took us in, Camlish?’ Shilah said with an eyebrow raised, standing in the centre of the chamber with her arms crossed over her chest.

‘Why am I the only confused one?’ I asked. ‘What is the Coldmarch?’

‘I’m surprised you haven’t heard the stories,’ Cam said, standing straight and grabbing at the end of his Opened Eye necklace. ‘I would have thought it would have been pretty common lore in the barracks.’

I shook my head slowly.

‘The Coldmarch,’ Shilah said, stepping up to me and putting a hand on my shoulder. ‘There’s a reason I kept bugging you about leaving the Manor. There’s already a path to Langria.’ She paused, considering something. ‘Or there was.’

‘Hold on,’ I said, needing a moment. ‘Just stop. We don’t know what’s down there. Just … hold on. This tunnel goes all the way to Langria?’

Shilah pointed back up the stairs with an impatient look. ‘Like she said, the Vicaress has her ways of getting information, and I don’t want to be near that clock if the hounds track our scent to the shop. Now come on, I’ll fill you in as we walk.’

‘You told me dozens of stories before we went to sleep on those cots.’ I suddenly felt a tad betrayed. ‘Why wouldn’t you tell me about an existing path to Langria?’

‘Like I told Mama Jana, I’m a girl of my word.’ Shilah kissed her finger and waved it at the sealed entrance in some foreign gesture of gratitude.

Did I really know anything about this girl?

She grabbed the lantern, holding it at arm’s length as she traipsed down the passageway, forcing back shadows.

Cam wiped his single tear from his cheek and held it out towards the Coldmaker, his excitement dipping. ‘I wish you could use it to make Ice. One day the Crier will forgive me.’

I had no idea what to say to such a thing.

‘Maybe one day,’ Cam said again with a hopeful shrug. ‘Maybe I can be chosen, too. A Jadan, like you both.’

Even the finest Inventor in the World Cried couldn’t tinker with someone’s blood, but still I said: ‘I’m sure.’

Shilah kept quiet, but I could see what she burned to say.

‘Come on,’ I said. ‘We have to hurry.’

Cam took both the supply bags, the dirty clothes and the basket of figs, not seeming to mind the burden, leaving me to carry only the Coldmaker, which I clutched dearly against my hip.

Shilah led us through the tunnel and I followed last in line, my head swarming with visions and possibilities.

‘The Coldmarch,’ Shilah said, only loud enough for me to get a trace of her words, ‘is a web of stops, stretches, and people along the path North. It’s a journey, not necessarily a place. There were hidden chambers like these run by Jadans and Noble sympathizers all across the Khatdom, set up so they could usher people in secret. Obviously no one could dig out a tunnel all the way from Paphos to Langria, as that would take all the Builders in the world thousands of lifetimes.’ She looked back with a wink. ‘I thought you were smarter than that, Spout.’

The way she said it, playful and wry, didn’t seem to connect, and I had no joke in response. I wasn’t in the mood to joke anyway.

‘Some brilliant Inventor could have come up with a digging machine to do all that work,’ Cam said. ‘I’ve seen some pretty impressive things in the tinkershop.’ He looked back over his shoulder, beaming. ‘That your next invention idea, Spout? I have to say, you’ll need something rather big to follow up’ – he gestured with his elbow to my bag – ‘a miracle.’

‘Flight,’ I said without pause. I expected a pang to strike my heart like a battering ram, but nothing shook. I thought back to my time under Thoth’s wool hat. I wondered what Matty might say if he could see me now, protecting something that could change the world, walking through the dark veins of myth. ‘Flight is next.’

Cam smirked. ‘If anyone can do it, I’d bet my Cold on you.’

‘What Cold?’ Shilah whispered with a scoff. ‘You don’t have any claim to the Abbs.’

‘I brought you the Frost!’ he said.

‘You mean the one that your father stole from the hardworking Patch Jadans?’

‘Wait.’ Cam suddenly stopped short, and I nearly crashed into his back. ‘This is wrong.’

I looked from side to side for talons or teeth. A drunken Levi had once assured our barracks that hounds’ eyes glowed red before the beasts pounced.

Cam shook his head, pressing himself flat against the side of the cave wall. ‘You go in the middle of us, Spout.’

‘Why?’

‘Just do it. You deserve to be in front of me.’

‘No, it’s okay, I can—’

‘Just. Please,’ Cam insisted, pressing himself harder, his face squished against the cool rock.

‘Why?’ I asked.

Shilah sighed from up front. ‘Boys. Hounds.’

‘And maybe worse,’ I said under my breath.

Cam tried to angle his way behind me, sliding along the smooth walls, his loose shirt and bags dragging. I tried to stop him and we did an awkward dance, both of us shimmying backwards.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked.

‘You’re the most valuable of us,’ Cam said, not meeting my eyes. ‘You stay in the middle. Just in case.’

All of a sudden the Coldmaker felt very heavy.

I didn’t say anything, letting Cam filter around in front of me. He was still balancing the basket of figs in one hand, and I snatched one, shoving it in my mouth and biting down hard, hoping some food might help me feel more normal.

‘Let me at least take the bag of dirty clothes,’ I said between bites.

‘I need to carry them.’ Cam craned his neck so he could see Shilah. ‘This is also for you, you know.’

Shilah kept walking, her back straight as the edge of a knife. ‘Drop the dirty clothes, Camlish. Mama Jana just needed them out of the shop.’

I was surprised how authoritative Shilah could sound. Cam gave a conceding shrug and did as commanded, tossing the bag aside and giving it a frustrated kick as he passed it.

We followed the corridor around a bend and found that the ceiling sloped lower and the walls pinched closer. I’d never had a problem with tight spaces before, but something about being underground made the musty air – cool as it may have been – feel as if it was going to suffocate us. My chest felt tight, and I dug my thumbs into my ribs, trying to loosen the knot.

Shilah didn’t seem to mind, and she picked up the pace, guiding us deeper into the dark.

‘Anyway,’ she said, ‘the Coldmarch has been kept extremely secret for obvious reasons. No mention of it in writing, and everyone involved kept about as tight-lipped as they could. The March supposedly only let a handful of Jadans North every year, most always young girls. It was shut down a while back, apparently ten years, but I don’t know why.’

‘But why would they shut down something like this?’ I asked. ‘Every Jadan should have known. No. Every Jadan should have gone.’

I drew my fingers along the wall. Feeling the stone, the damp texture and tiny imperfections, I understood the importance of such a place as this. That didn’t mean I wasn’t detached. I was walking through a secret that could have started a revolution, a place that proved us chosen, or at the very least worthy, and I should have been struck with something powerful. Awe perhaps. Disbelief maybe. Flames of righteous indignation. Something that infused life back into my soul.

But all I could feel was the stone.

My father was gone.

Shilah shrugged, urging us onwards. ‘Maybe the Khat found out. Maybe something changed. I imagine the whole situation was delicate to begin with.’

‘If the Khat found out about it,’ Cam said, all of a sudden looking very pale. ‘That means we might be walking right into their hands.’

Shilah picked up the pace. ‘Yes. It’s possible.’

Cam stopped. ‘So …’

‘So we have no choice, Camlish,’ Shilah said, holding the lamp higher, her feet slightly splayed.

‘Why do you keep saying my name like that?’ Cam asked gently.

‘Because it’s not a Jadan name,’ Shilah said with a huff.

‘I didn’t choose to be born Noble,’ Cam said, his face strained. ‘But I’m damn sure doing everything I can to make up for it.’

‘I know,’ Shilah said softly. ‘But you still don’t know what it’s like to be Jadan. You never will.’

‘I’m going to prove it to you,’ Cam said over my shoulder. ‘I’m going to show you that—’

All of a sudden the corridor ended in a wall with a large smear of dark red cascading from edge to edge. I didn’t need to examine the colour to know that it was blood, and my stomach tightened.

The Coldmarch was over as soon as it had started.

My machine was heavy; my foolishness weighed more.

‘Mama Jana sent us into a trap,’ I said, still oddly removed from the situation at hand. I stopped short, wondering how long it would be until we were cornered by beasts. I didn’t blame Mama Jana. Life was hard enough in Paphos, even for the lowborn Nobles, and everyone had to do what was necessary to survive. I didn’t blame her. I ached. Even with all the whips and stabbings I’d suffered as a Street Jadan, I had come to find out the worst sting came from betrayal.

Cam came up next to me, his throat visibly stiffening. ‘Is that blood on the wall?’

Shilah kept pushing forwards, swinging the lantern.

‘She’s probably keeping us down here until they arrive,’ I said matter-of-factly. ‘Then the hounds can rip our throats out without any fuss. I bet we’re worth half the Khat’s fortune, and Mama Jana will be set up for life. It’s smart, really.’

I held the Coldmaker closer to my chest, wondering how I could at least save the machine. Even if I was disposable, the discovery was of the utmost importance. If I had enough time, I could have used the metal corners of the machine itself to dig a proper hole into the clay where it might hide.

Cam unshouldered all the supplies he was burdened with, shaking the basket of figs. ‘But why would she give us all of this, if it’s just a dead end?’

‘It makes sense,’ I said, sniffing my arms and enjoying the scent of life for what might be the last time. Even beneath the rosemusk I could smell ash and fire. ‘Now they can do everything in secret and not worry about rebellion. Like the mistake they made with Matty.’

‘For someone who helped crack the secret to Cold,’ Shilah said, turning to me, ‘you’re being quite glum.’ She stabbed a finger against the red on the wall. ‘Alder. Also known as Alder of Langria.’

I paused, trying to remember how I knew that word. ‘Like the plant Leroi had on his table?’

Shilah nodded.

Cam gave a blank-faced stare.

‘Look closer,’ Shilah said, beckoning us forwards. ‘This blood spells out a word.’

Tentatively I stepped forwards and saw that without the cover of shadow the smears did indeed look like letters.

‘It says hope,’ Cam read, astonished. ‘How’d you know that stuff wasn’t blood?’

‘Because all Jadans know how blood dries,’ Shilah said, pushing open the whole wall with a single thrust and revealing a much larger chamber behind, dust clouding the air.

‘Huh,’ I said, my eyes having trouble taking in everything at once.

Cam nearly dropped the basket of figs. ‘Wow.’

‘Hurry,’ Shilah said, letting the wall close behind us and rushing forwards, practically ignoring all the sights before us that demanded admiration. The vast room itself was still encased in long clay walls, but unlike the crawlspace leading up to it, this chamber had overwhelming signs of past travellers.

The Opened Eye of the Crier was painted everywhere, in all different styles, drawn on with the same red alder as on the entrance wall. Hundreds of Eyes looked over the chamber and gave the room a hopeful air. Small assortments of trinkets and keepsakes sat along the perimeter of the walls, like shrines. Jadans were never allowed to own much, and even though the dust and neglect made it clear that none of my kin had been down here in a decade, the sense of creativity felt alive and electric.

There were makeshift dolls posed to look as if they were tearing off their slave-uniforms. And little ceramic bowls with gold paste filled the cracks around the shrines. Ragged sleeping blankets of all colours were pinned to the walls, making one broken, yet beautiful tapestry, while whistles carved out of broken cane sat poised and ready to sing. Broken hourglasses were fitted sideways so the sands would never fall, and links of rusted and shattered chains were woven between all the Opened Eyes. I saw a few taskmaster whips – obviously stolen – buried up to the hilt in the floor, as well as statues of ancient animals that must have been painstakingly chipped out of barrack bricks.

And prayers.

So many prayers, all carved directly into the walls. Words of thanks and fear and hope and pleas for guidance. They weren’t all written in the common tongue of Paphos, either. There were letters I didn’t recognize, ancient designs with tails and loops and dots studding the bottom lines. I couldn’t stop looking around at the words, stunned by how many Jadans had been down here; all hopeful, preparing to make the journey to paradise.

Cam plucked a Wisp off one of the shrine tables. ‘Someone left Cold behind.’

Shilah shrugged. ‘You’d probably give anything you had too, if you knew it might help keep you safe. Sacrifice is a big thing with my people.’

‘But Cold?’ Cam asked. ‘Wouldn’t they want to use it? It’s a long way North, and the Sun is even stronger there.’

Shilah shook her head, as if Cam was missing something obvious.

‘What?’ Cam asked, putting the Wisp back down. ‘Is that offensive to touch?’

Shilah looked at me, her eyes resolute. ‘The Vicaress can read, too. And I guarantee she knows the difference between alder and blood. We need to keep moving.’

I nodded, but a part of me wanted to read every single prayer down here, and touch every gift, thinking about the Jadans who might have left them behind. They’d challenged the Khat’s Gospels to try their luck in this Coldmarch. They must have believed our people were more than dirt, that we weren’t supposed to be slaves.

Even without a Coldmaker, they had taken a leap.

If only they could see the machine in my arms.

‘You’re right,’ I said, my hand trembling as I pressed it against my machine. The metal was cool to the touch, even after all that time under Sun.

Shilah quickly led us through the decorated chamber, which at the end funnelled into another small space. Before we pushed into the mouth of the new tunnel, Shilah stopped and moved her head from side to side. If possible she drew her back even straighter, whipping her braid around so it was out of her face. The walls were closer near the exit, and two tallies of names had been etched on either side.

‘Lost,’ I read on top of the left wall.

‘Saved,’ Shilah said, pointing to the right.

The ‘saved’ side had considerably fewer names than the ‘lost’ side – which had hundreds, if not thousands, of names carved in, spanning floor to ceiling. I let my eyes scan the rows top to bottom, feeling more and more dismayed the closer to the ground I got, even spotting a few ‘Micahs’ along the way. Had all these Jadans really been killed in the name of freedom?

And then I reached the final name on the wall.

It looked entirely fresher than the rest, scraps of clay sprinkled on the floor underneath. It must have been why Mama Jana had so much earth trapped under her cracked fingernails.

She’d scratched his name in by hand.

Abb.

Cam bent over and put a hand on my shoulder. ‘I’m so sorry, Spout.’

I swallowed hard, my knees shaking as I crouched.

It’s not that I didn’t know he was gone, but here was the first physical proof. Not just a vision, or the Vicaress’s words that could have turned out to be a lie. Here was the name of my father, the best slave I’d ever known.

Emotions tried to flood in, but I had no capacity to deal with them right now, so I swallowed them back.

It wasn’t even that hard.

‘Drop the bucket,’ I said casually under my breath, opening the lips of my bag and showing him the invention. ‘All because of you.’

‘Hmm?’ Cam asked.

I put the Coldmaker on the ground, and, instead of grabbing one of the Abbs already tucked into the inside pocket, I flipped the machine on.

The air in the cave quivered as my invention went to work, a cool breath drawn from the entire tunnel. Wind whipped across the shrines, the temperature changing in the room. Why the machine worked was a mystery I intended to examine, but at least for now I had a general idea. The vials were opened as the gears turned. A few tears fell on the Frost first, which sat in its Cold Charge bath. This caused the initial reaction. Then a drop of my Jadan blood was let out at the catch-point as a starter material, where the gold gathered and bundled to form an Abb.

From a strictly inventive standpoint, the procedure was simple and straightforward, nothing other than a natural response.

Cause and effect. Simple. Emotionless.

As the new Abb came to life, I shut off the machine and plucked up the golden bead. A crisp scratching came from behind me, so I spun around and found Shilah with a long blade in her hand. It was folded steel, the silver handle ornate as they came. She was doing something to the bottom of the ‘saved’ wall. From my vantage it looked almost as if she was crossing a name out.

‘What are you doing?’ Cam asked.

Shilah finished and pressed her back to the place she’d marred, hiding the evidence. ‘Let’s keep moving.’

‘Can I borrow that?’ I asked, pointing to the blade. I was actually glad of Shilah’s thievery. Mama Jana had a decent collection of blades behind the counter, and we would need it more than the shopkeeper did.

Although perhaps not if the hounds had found her.

Shilah tossed the blade at my feet. I gently prised a nook out of the second ‘b’ in Abb’s name, big enough so as to make my own kind of shrine. I stuffed the fresh, golden Abb in the space, snug and secure, and then closed my eyes, offering a prayer I was sure was not the first of its kind to echo across these walls.

‘Let’s go,’ Shilah said, this time gently. ‘We don’t know how long this next stretch of tunnel is going to be.’

‘One more thing,’ I said.

I picked an empty spot on the wall and carved in a small feather.

Chapter Four (#udc781fce-1830-589a-a283-d3abbc288866)

We were stuck underground for much longer than expected.

Whoever had built this part of the Coldmarch had used the natural cracks in the land for a foundation, presumably to decrease the amount of actual digging that needed to be done. Since the Builders had used the existing spaces already waiting underground, the way through ended up being complex and disorientating. The compass told me we were zig-zagging back and forth beneath the city, quite often straying from North. Some of the natural cracks in the earth were huge, the size of Cry Temples, with sporadic holes that plunged downwards into a forever sort of darkness. Often in the distance we heard the sounds of rushing water, leaving me to wonder how close we were to the River Singe. We made sure to follow the red alder line painted at our feet so as not to get lost or stray off the designated path. In other sections the walls became incredibly congested, scarred with hundreds of scratches. I imagined the marks were from bodies and supplies trying to squeeze through.

We had no way to tell time in the darkness, but I imagined it was a few days. We stopped to sleep twice, both times finding sanctuary off the path in case the Vicaress had found her way down here. We only intended to rest for a few hours, just to gather our strength, although it was hard to judge how long we slept, since we had to extinguish the lamp each time to conserve fuel. Shilah and I slept with our bodies pressed together, our arms linked, belts looped together. This was both for warmth, but also for safety, in case something foul tried to snatch one of us away in the dead of night. Shilah thought I was being paranoid, but she was the one who’d suggested the knotted belts. I offered to have Cam sleep on my other side, tied to us, but he kept declining, insisting on staying awake and keeping guard. I’d told him this was unnecessary, since he wouldn’t be able to see, but he wouldn’t listen, keeping at the edges of whatever nook in which we took refuge, constantly vigilant.

By the third leg of the trip his eyes were as red as the alder line.

He also refused to eat any more of the figs. They didn’t last long anyway.

Not much was said as we made the journey. There was no reason for the silence, but I had a feeling Cam and Shilah were nervous for the same unsaid reason. None of us wanted to be the one to startle something ancient living down here in the dark. So far there had been no red eyes or grinding of unseen fangs, but anything was possible so far beneath the sands of Paphos. The world was different down here, cool and dark, and apart from the threat of Hookmen and Firegogs, it was a fitting start towards paradise. There was no Sun to bake us dry, no taskmasters waiting to scar our backs, no Nobles using our bodies for their own gain. For the Jadans who took their chances on the March, it would have been their first taste of peace.

‘Do you like being called Jadans?’ Cam asked, his quiet voice thunderous after so much silence. We were trudging through a thin clay corridor with crystal cones hanging above our heads and sometimes reaching the floor. The pointy wedges made it feel as if we were threading our way through a giant mouth. There had still been no sign of the Vicaress on our heels, no flaming dagger in the dark, so we’d been able to slow the pace down a bit. The overall mood had grown a bit lighter, since, despite the constant threat of danger, we had yet to be eaten. Even I was feeling the smallest twinges of hope. Unfortunately, every time my chest tried to kindle the sensations into happiness, all I could think about were the names carved into the ‘lost’ wall.

I examined a particularly thick crystal tooth, wondering what sort of benefit the shiny material might have offered crushed up. Leroi would have known.

‘As opposed to?’ I asked Cam, ducking low as I moved away, so as not to be speared by the tip.

‘Well,’ Cam said, lowering his voice. ‘Since the Great Drought, there’s a negative connotation involved with the word.’

Shilah glared back at us.

‘Not that I think anything is wrong with it,’ Cam said quickly. ‘It’s just that I’ve heard my brother and uncles – and obviously my father – say “Jadan” with such hate. They make it sound worse than saying slave. Is there something else you want to be called? Because I’ll call you that if you want.’

‘What brought this on?’ I asked.

‘I figure if we get out of here alive then—’ Cam got flustered, the crystal cones gently reflecting the redness of his cheeks. ‘I don’t know, I thought that maybe you’d want your people to be called something else. And I could be the one to start it now. It’s dumb, sorry. Forget it.’

‘When we bring things back to how they were supposed to be,’ Shilah said with a snort, ‘just don’t call us Nobles.’

Cam adjusted the bags of supplies on his shoulder so he could avoid a crystal pillar more easily. I imagined the bags must have grown quite cumbersome after so long, not as much as my burden, but unwieldy nonetheless.

‘Just forget it,’ he said.

‘It’s considerate of you.’ I tried to sound consoling. ‘But Jadan is something to be proud of. If anything, we’ll just have to change the connotation.’

‘Whatever you need,’ Cam said, giving an agreeable bow, as low as he could manage without spilling everything. His eyes went to Shilah. ‘Just let me know.’

I stared back at him, blinking a few times. The lantern light barely reached him, and his shiny yellow hair now looked black from all the dirt and dust it had attracted.

‘What?’ he asked.

‘Nothing.’ I nodded, noting his eyes had moved to the Coldmaker. ‘I believe you.’

I licked my finger and touched the nearest pillar, bringing it back to my mouth. My tongue recognized the delight better than my eyes.

‘Salt,’ I said.

Cam immediately reached up and cracked off the tip of the nearest pillar, stuffing it in the bag. Shilah shot him a look, as if reminding him we shouldn’t be drawing attention to ourselves.

Cam licked his dry lips. ‘When we get to Langria we’ll have to have a feast, and I can say I brought the free Jadans salt from the Coldmarch. As a gift.’

I smiled, although it didn’t climb past my lips.

‘And,’ Cam said with a glimmer of pride, ‘you need salt for the Coldmaker, right? To keep the Charge.’

‘Good thinking,’ I said with a nod. ‘Let’s get a few.’

Shilah shrugged, and we all snapped off a handful of salt each, adding it to Cam’s supply bag. I pressed my hands to my nose afterwards, but there wasn’t any scent.

‘Salt and Abbs and revolution,’ Cam said as we started moving again, following the alder. He immediately stopped and then gestured for Shilah to lead us, giving her a respectably wide berth. ‘It should be quite the feast.’

Our next stop took place beside a tiny stream, which had carved a shallow bed into smooth rock as it cascaded endlessly into the darkness. We’d heard the rushing waters from the alder path and wound our way to its shores to fill up our waterskins. Gentle currents had brushed the endless tunnel wide, making the passage seem both frightening and serene. The waters were some of the most delicious I’d ever tasted, possibly because they’d been kept away from Sun for an eternity. We only needed to add the smallest slices of Abb to get them to cool.

The journey had already begun to thin Cam out, his voice hollow and cheeks sunken. I asked him to sleep. Begged him even. It ended up taking three direct commands to get him to agree to shut his eyes for one hour. I gave him much longer. While he snored, one foot hanging limp in the waters, Shilah and I talked of fragile things. She kept dipping one finger in the water and bringing it over my hand, letting the single droplets fall on the back of my palm. She did this until the puddle at my feet trickled its way back to the source, rarely meeting my eyes as we spoke.

We talked of meeting out in the dunes behind my barracks, when I invited her to join our family, but instead she disappeared out into the sands. She told me she used the Rope Shoes that I’d traded her for the Khatmelon quite a bit, which is something I’d always wondered. We joked about the days working with Leroi back in the Tavor tinkershop, hiding under the floor grate whenever anyone unfamiliar came knocking. We discussed at length all the plants she’d cultivated for Little Langria. About where she got the soil and seeds, and vines. About the humour of the weaver beetles that lived on her persimmons. She asked about the feather I’d scratched into the wall, and I told her about Matty and the board game we were creating; how close we’d come to finishing. About how Moussa, Matty, and I lessened the harsh tinge of the day by playing ‘whatsit’, where we made up stories to go along with the shapes of our bruises. She told me of the time she visited the Hotland Delta, having stowed away on a merchant ship. About how the High Nobles there had a certain ritual that they performed each night to pay tribute to the Crier. Each Sundown they would fold little boats out of Droughtweed and sail them along the Singe, a single Wisp floating in each hull. Shilah’s smirk was stupendous as she told me how she would wait downstream with a net to collect the boats. Over the course of a week she’d made a small fortune.

I told her what it was like with such a large family.

She told me what it was like to live alone.

We didn’t mention my father or her mother once.

Some things can live delicately in memory, but shatter when put into words.

We didn’t have much fuel left for the lantern, so I had to wake up Cam sooner than I would have liked. He whimpered at my touch, but when he grew conscious his face hardened and he sprang to his feet, grabbing our supply bags and empty basket of figs, leading us back to the path.

Finally, after more endless tunnels, the single red line led us to our escape. The sleek and spindly cave once again widened into a proper chamber, funnelling us towards an actual way out. The wooden slab was slanted so much it was nearly horizontal, and no light spilled in through the cracks on the sides, but it looked like salvation nonetheless.

Wiping the layered crust of dirt from my forehead, I debated thanking the Crier for getting us here alive – but I decided that I was only ready to open one door at a time right now.

Cam pointed to the tilted door in front of us and the buckets sitting at its base, lowering his voice. ‘Where do you think it lets out?’

‘Honestly,’ I said, matching his volume. ‘I’ve been so turned around this entire time I have no clue.’

Shilah brought the lantern over to the door, where something was written in more alder. As she scanned the lines, her lips moved and I couldn’t help but notice how full and plump they were. My focus shifted to her hair, long and tattered and matted with dirt. And her eyes, spilling over with all the sad things she’d already seen in this world.

‘Imagine if we didn’t have a lantern,’ Cam said quietly. ‘And we had to do this whole thing in the dark.’

‘We almost did,’ I said, pointing to the oil reserves, which were dangerously low.

‘Right now we’re at the edge of the Drylands, just North of Paphos,’ Shilah read. ‘Two days’ walk until the next stop on the Coldmarch. The shack is in the bottom of the three-humped valley, and will be marked by a green streak over the threshold.’ She turned to us with pinched lips, pointing to the empty buckets. ‘It says please take all the water and Cold we need. And may the Crier watch over our family.’

‘Two days.’ Cam did the sums in his head, looking into the bag of supplies. ‘No food, but plenty of water. Should we wait until night-time to leave?’

Shilah peered back into the dark chamber, the shadows flickering and ominous. ‘Not sure we’ll have until night.’

Pressing my fingers against the door, I found that it didn’t have much give. There was no latch to undo, and the hinges told me that it was set up to swing outwards.

‘We need to push together,’ I said.

Gathering ourselves, we gave the door a hard, collective shove. The pressure should have made the wood budge at least, but it was immovable.

‘Is it locked?’ Cam asked. ‘Want to try the trick with Ice in the lock again, Spout?’

I ran my fingernail around the cracks at the edges of the door, noting the gritty sand. ‘I don’t think there’s a lock. Just ten years of sand pressing down on the other side.’

‘You think we’re under a dune?’ Shilah asked, crossing her arms.

‘I took a girl to see the Drylands once,’ Cam said, looking down and scratching the back of his neck. ‘And from what I remember they’re pretty barren, but it’s possible the dunes have shifted.’

Shilah put a hand on the door, as if to ask it through touch. ‘I don’t think it would let out so close to the dunes. Maybe the Khat barred it from the other side when he found out?’

Cam put both arms on the door and shoved again, the vein in his neck showing heavily through his light skin. He started pounding on the door with his shoulder to try to get more leverage, but I quickly put a hand on his arm to stop him.

‘We have to be quiet and strong,’ I said. ‘We don’t know what’s out there.’

We all tried to push at the same time again, but the door wouldn’t budge more than a hair upwards. It was then I noticed the middle of the wood distending inwards, gently caving under all the weight.

‘Wait,’ I said, remembering myself. ‘Let me see that knife.’

Shilah reached under her dress and unstrapped the knife from her thigh. She handed over the blade and I tried not to think about the heat lingering in the metal.

Cam stared at the blade, his eyes softening.

‘In case of the Vicaress?’ she asked. ‘You still think this is a trap?’

‘No,’ I said, going to work on the door’s hinges. ‘I’m just trying to think like an Inventor.’

Leroi had taught me that when it came to tinkering, sometimes the best answer was also the simplest. The door may have been intended to open upwards, but Inventors worked with their own intentions. After a flurry of careful twisting and prising, the hinges groaned, letting me know things were about to give.