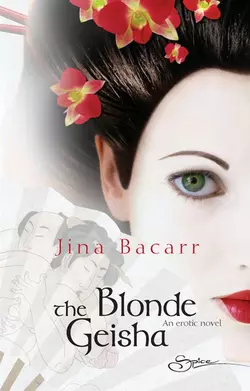

The Blonde Geisha

Jina Bacarr

The early summer of 1892 brought a heavy rainy season that year in Japan.Plum Rain, the Japanese called it, because it comes when the fruit bulges with ripeness and promise. Like a young girl reaching womanhood. A girl like me. In the ancient Japanese tradition of beauty and grace, sex and erotic fantasies are hidden secrets that only a select few may learn, and which are forbidden to foreigners.But when a threat to her father's life puts her own in jeopardy, young Kathlene Mallory is sent to live in safety at the Tea House of the Look-Back Tree, where she is allowed to glimpse inside the sensual world of the geisha. During the years of her training in the art of pleasuring men, Kathlene's desires are awakened by the promise of unending physical delights, and she eagerly prepares for the final ritual that will fulfill her dream of becoming a geisha — the selling of her virginity.The man willing to pay for such an honor, Baron Tonda, is not the man for whom Kathlene carries a secret longing, but he is the man who will bring ruin to the teahouse, and danger to Kathlene, if he is disappointed….

Jina Bacarr

The Blonde Geisha

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To my husband, Len LaBrae,

fellow adventurer and lover.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to thank my wonderful editor Susan Pezzack,

who brought out the best in my manuscript with her astute

observations, Leslie Wainger, the editor who started it all with

one phone call, and Roberta Brown, my friend and agent and

I’m sure in another lifetime, my geisha sister.

The early summer of 1892 brought a heavy rainy season that year in Japan. Plum rain, the Japanese call it, because it comes when the fruit bulges with ripeness and promise. Like a young girl reaching womanhood.

A girl like me.

The air was warm and damp, but as in all things Japanese, a uniqueness about the rain awakened my senses and stirred my desires. I was struggling with grief while a wild joy surged within me, a sensual discovery of my changing body that filled me with concupiscence. An unsettling combination of emotions for any young girl. I yearned to yield to my desires, to awaken my female soul, to love, and be loved.

I was fifteen years old.

And I wanted to be a geisha.

I so admired the spirit of these women, their daring and their beauty. They were purveyors of dreams and lived in a fairy-tale world of misty romance. Every day on my way to missionary school, I’d stare at the young apprentice geisha, scurrying along the street on their high sandals with a small bell fixed inside, their white-painted faces peeking out from under their pink paper parasols.

At night en route to the Kabuki theater with my father, I ogled the geisha riding in a jinrikisha, wearing their formal black kimono embroidered with flowers and birds. On late afternoons, I giggled when I passed by the okâsan, mama-san, sitting on her polished veranda and smoking her ivory pipe.

Filled with inspiration, shaking more with anticipation than with fear, I felt compelled, driven, to follow my desire to enter into this ever-fascinating—sexually liberated—world of geisha. I wanted to know how this world of flowers and willows coexisted in a land where girl babies were put upon the cold ground for the first three days after they were born so they may know their place in society.

Under men.

I didn’t understand why the women in this land of shoguns and samurai kept their eyes lowered, their hearts hidden, their tears to themselves. Polka-dotted tears on a hard, wooden pillow. As durable as their souls, if they were to survive.

If they were to prosper.

If they were to love.

I was so impressionable, so hungry to indulge in my erotic fantasies, if I didn’t find a way to release my pent-up emotions, I was convinced I would spend the rest of my life concealing the sensuality hidden within me. Instead, I prayed to the gods I’d find the courage to embrace my sexual desires and release my soul from this anguish.

I hadn’t yet tasted the sweetness of a man’s caress nor experienced the torment of lost love. My young breasts were budding with the ripeness of hard red cherries, my hips slim like a boy’s. I could only guess what sense of discovery awaited me in a land where pleasure was a woman’s misfortune. And duty was her only pleasure.

Or so it appeared.

It wasn’t always true.

According to Japanese folklore, the women in the geisha quarters possessed a secret, a mystique so closely guarded for more than two hundred years, they shared it with no one but their geisha sisters. Secrets to keep their skin forever young. Potions to make men fall madly in love with them. Strange toys to bring wave after wave of sexual enjoyment to them and their lovers.

Motivated by this vivid tale, I sneaked down to the geisha quarters of Shinbashi where I could hear their laughter and their restless sighs coming from inside the high walls surrounding the geisha house. I imagined what earthly delights lasted throughout the night. Could I, an outsider, penetrate their mask of civility and learn their exquisite ways to pleasure a man?

Or to pleasure myself?

Could I?

Through the strange workings of the gods that brought much grief and anguish to my young self, I had the opportunity to enter the geisha house that summer. Although I had hair long and golden like bursts of sunbeams exploding into the dawn, and eyes as green and rich as the silk brocade lining of a merchant’s coat, I became a maiko, apprentice geisha, in Kyoto. After three years of training, like the slow unfurling of the rose-pink lotus blossom, I became a geisha.

So many years later, I have reached an age when I can break my silence without violating the geisha code of secrecy. I can share with the outside world my life in the geisha house, the beauty and grace, the sexual and erotic fantasies, and the hidden secrets.

As I sit here in the garden of the teahouse with the butterflies settling on my shoulders and the chime of the wind-bells in my ears, I will write it all down as I remember it on the finest rice paper as translucent as the wings of a moth and dusted with silver and gold: the men I’ve loved, the geisha sister who risked her life for me, the mama-san who reared me as a daughter; their touch, their laughter and their most intimate moments.

And now, as I take into my hand the brush and dip it into the ink, I will tell you the extraordinary and sensual story of the blond geisha.

Kathlene Mallory

—Kyoto, Japan 1931

PART ONE

KATHLENE, 1892

I remember the first time I saw the lights in the geisha quarter of Gion, all pale and yellow, like the moon overhead. Red lanterns with black Japanese characters swayed back and forth in the evening breeze, beckoning me into the teahouse. But it was the sound of the Gion bell ringing in the distance I remember most, making me wonder if everything in life was fleeting. Even love.

—Diary of an American girl in Kioto, 1892

1

Kioto, Japan 1892

I couldn’t tell anyone, not even the gods, but I was scared…really scared. Even before I got to the nunnery, I knew I had to escape. Though I respected the nuns for their piety and servitude, I wanted to be a geisha. Had to be. Didn’t nuns shave their heads and their eyebrows, making their eyes bulge big and unnatural in their faces? I held on to my long hair, vowing never to let them cut it. Even more disturbing, nuns wore plain white kimonos. White was the color of death. Why was my father taking me to a nunnery? Why?

Was I being punished?

I didn’t do anything wrong. Stroking myself until I found pleasure wasn’t wrong, though I was often overcome with a rising desire, a hunger that threatened to explode within me. I wanted to love and be loved. Until then, I had so much sexual energy I had to do something to release it.

But not in a nunnery.

I can’t go. Please.

The world of flowers and willows is my destiny, I wanted to tell my father, no other. Didn’t the geisha possess the high qualities of heart and spirit? Didn’t they inherit a compelling destiny? Didn’t Father say I was uprooted from my homeland like a beautiful flower replanted in uncertain soil? Didn’t a geisha also leave her home to find her destiny?

But it was not to be.

“Don’t dawdle, Kathlene!” my father whispered harshly in my ear, pulling me through the railroad station, my small suitcase banging hard against my thigh. It hurt, but I didn’t complain. I’d have a bruise on my leg by morning, but it wouldn’t show through my white stockings.

Morning. Where would I be then? Why were we here now? What happened to my peaceful world? The girls’ school in Tokio run by the Women’s Foreign Missionary.

What happened?

Rain pelted me in the face. I had no time to anguish over what lay ahead of me. I noticed the lack of noise and scurrying all about me, as if everyone had disappeared in the mist. That was strange. Rain never stopped the Japanese from moving about the city as quickly as hungry little mice, seeing everything, nibbling at everything. They never thought of rainy days as bad-weather days, but rather a blessing from the gods because the rain kept their rice baskets full.

As I plodded through the empty train station with my pointy shoes pinching my toes, wishing I were wearing my favorite clogs, with the little bells, the ones my father bought for me in Osaka, my entire body throbbed with the slow, steady beat of the ceremonial drum. No, it was more like a sexual lightning that struck me at the oddest moments. Since I’d reached my fifteenth birthday, more and more often the hint of such pleasures came to me. When I bathed in the large cypress tub, I wiggled with delight when the warm water, smelling of citron and tangerine, swam in and around my vaginal area, teasing me with tiny sparks of pleasure.

And at night when I lay naked in my futon, the smooth silk lining rubbed against the opening between my legs, making me moist. I wished for a man who would fill me up inside so deeply the wave of pleasure would never end. I dreamed of the day I’d feel the strength of a man’s arms around me, his muscles bulging, his hands squeezing my breasts and rubbing my nipples with the tips of his fingers. I smiled. I had the feeling the nuns would frown upon me thinking such delicious, sexy thoughts.

I asked, “Where is this nunnery, Father?”

“At Jakkôin Temple, not far from here.”

It isn’t far enough.

“Why did we leave Tokio in such a hurry?”

“Don’t ask me so many questions, Kathlene,” Father said, popping up his large, black umbrella to keep the rain off us. “We’re not out of danger yet.”

“Danger?” I whispered in a soft voice, though I was certain my father heard me.

“Yes, my daughter. I couldn’t tell you this before, but I’ve made a powerful enemy in Japan who wishes me great harm.”

“Why would someone wish to harm you?”

I played with the torn finger on my glove, ripping it. I couldn’t help it. I was worried about my father, terribly worried. A gnawing ache told me something worse than going to a nunnery had taken place.

“If you must know, Kathlene, a great tragedy has occurred,” my father said, his voice muffled by the rain. His harsh words shot through me, making me hear the pain in his voice.

I dared to ask, “What do you mean?”

“A man has lost what is most dear to him and he believes I’ve taken it from him.” My father looked around the railroad station, his eyes darting into every corner. “That’s all I can tell you.”

“What could you have done—”

“Don’t speak about what doesn’t concern you, Kathlene. Something you’re too young to understand,” my father said, never looking at me, only at some hidden enemy I couldn’t see. He held my hand so tightly my bones felt as if they would break.

“You’re hurting me, Father. Please…” My eyes filled with tears. Not from the pain, but from the fear for my father’s safety, making my heart race.

“I’m sorry, Kathlene,” he said, loosening his grip. “I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

“I know,” I said in a quiet voice, but the pain in my heart remained.

Father continued to look everywhere, then, satisfied the platform was empty except for the old stationmaster on duty at the wicket, he kept walking. Faster now.

I forced myself to put a skip into my step as I struggled to keep up with my father’s long strides. He’d barely spoken to me on the long train trip from Tokio. His head turned right then left, checking to make certain I was at his side. Even now, he dragged me behind him, wet, hungry and tired. He continued to hold on to me tightly, so tightly, as if he feared he’d lose me. He grunted like an unhappy samurai, his head bowed low so no one would see his face.

That was so unlike my father. Edward Mallory was a giant of a man, towering over everyone. He had a booming voice that carried fast and far. Here, voices were as soft as stockinged feet scurrying across wooden floors so sensitive they creaked if a nightingale landed upon them.

My father was also pigheaded, stern, and he didn’t understand me. How could he? I didn’t see him as often as I wished. He worked for an American bank, he was proud to tell anyone who asked, investing the bank’s money in this new land. The English had built the first railway and my father had to work hard to keep up with the competition. Every day more overseas banks were opening up branches, so he told me, and investing in the railway system spreading out over the island. He was often gone for days, meeting with officials from the Japanese government and ruling families, and drinking cup after cup of foaming green tea. Sometimes, he drank the tea with me. It tickled my mouth and made me giggle. Not my father. I doubted he ever laughed at anything.

“Stay close behind me, Kathlene,” Father ordered, his voice stern. “The Prince has his devils everywhere.”

“The Prince?” My curiosity was piqued. I’d heard my father had many meetings with the foreign minister and other dignitaries, but a prince? My heart quickened, my eyes glowed, then dimmed when I felt my father’s body stiffen, his hand go rigid around the umbrella.

“Forget what I said about the Prince, Kathlene. The less you know, the better.”

I had no time to wonder what he was talking about. My stomach jumped when I saw a young man pulling a jinrikisha, racing out of the shiny blackness of a narrow street.

My father looked pleased, very pleased, to see him.

So was I.

Instead of wearing the cloak made of oiled paper the jinrikisha drivers wore in the rain, he was nearly nude, exposing his sinewy bronze flesh in the most delectable manner, as if he enjoyed showing off his muscular body to the rain goddesses. I imagined being a raindrop and landing upon his lips and tasting the sweetness of his kiss. I giggled. Kissing was very naughty to the Japanese, an intimacy they rarely exchanged, though I was eager to discover its pleasures.

I eyed the bulging muscles on the boy’s arms, naked and pleasing to my eye, as were his powerful-looking legs. He ran barefoot with only a bit of rag tied around his big toe. What intrigued me most was the swath of dark blue cotton he wore around his torso. I giggled. It wasn’t much bigger than the bit of rag.

Most days, the station was filled with jinrikisha boys waiting for passengers, Father told me, noticing my avid interest in the young man. They were well-informed runners who knew what stranger arrived when, whose house you were passing, what plays were coming out, even when the cherry blossoms would unfold. The station was empty today except for this boy, the only one brave enough to run in the rain.

He stopped in front of us and bowed low.

Dusty, bare-legged coolies, I often heard the English ladies call the jinrikisha drivers. How could that be? Not this boy. I closed my eyes, letting my mind drift through a whispering darkness. An irresistible urge rose up in me that made me yearn for something, something, but I couldn’t grab on to it. As if an invisible spirit with cool fingers dropped icy dewdrops upon my naked belly and made me squirm with delight.

I opened my eyes. I couldn’t contain my curiosity about the young man who pulled the big two-wheeled baby carriage. I craned my neck to see him better, but his face was hidden from me by a low-brim straw hat. No matter. I knew in my heart he was handsome.

A bigger surprise awaited me. Without a word my father hustled me into the black-hooded conveyance. I drew in my breath, somewhat in awe. Excitement raced through me. Only geisha were allowed to ride in jinrikishas. I swore I could smell the scent of the camellia nut oil from their hair lingering on the seats.

Closing my eyes and resting my head against the seat, I imagined I was a beautiful geisha. What would I do if I found a handsome young man when my frenzied sensations were at a peak, my face flushed, my breasts swollen, my nipples hard, my throat dry?

Would I lie down, raise my legs up as my lover kneels between my thighs,his hands on the straw mat?

Or would he lie on his back and stretch his legs straight as I straddle hisbody, my knees to his sides?

I inhaled the fresh smell of rain in the air. I found such thoughts so romantic and amusing, but I lost my smile and kept my eyes straight ahead when I saw my father staring at me.

“I’m troubled, Kathlene. Something is amiss. There’s no one here from the temple to greet us.” He rubbed his chin, thinking, then: “I have no choice but to trust this boy to take us to our destination.”

“I trust him, too, Father.” I grinned when the jinrikisha boy turned around and lifted up his head from under the flat straw plate of a hat he wore and smiled at me. I lay back on the seat, relieved. He wasn’t much older than I was. And he was handsome.

Surely my father couldn’t keep me hidden away in a nunnery forever, without a chance to see anyone? Nevertheless, these irrational fears chilled me, flowed through me, and crawled up and down my skin like tiny golden-green beetles. Cold perspiration ran down my neck.

How was I going to become a geisha if I was shut away in a nunnery? Nuns were kept out of sight from visitors and spent their time in meditation and arranging flowers, not in ogling the muscles of jinrikisha boys. As if the gods decided to remind me I had no choice, thunder rolled overhead. A downpour was on the way.

I heard my father give the boy instructions where to take us, the boy nodding his head up and down. He bowed low before raising up the adjustable hood of steaming oilcloth covering us. A canvas canopy arched over the seat to protect us from the rain.

“Hurry, hurry!” Father shouted with urgency to the driver, then he sat back in the two-seat, black-lacquered conveyance.

The boy grunted as he lifted up the shafts, got into them, gave the vehicle a good tilt backward and took off in a fast trot.

I had no time to ponder my fate as the boy snapped into action and pulled the jinrikisha down a street so narrow two persons couldn’t pass each other with raised umbrellas. I thought it unusual the boy didn’t shout at the few passersby to get out of our way as most drivers did. Instead, he ran in silence, his heavy breaths pleasing to my ears. I kept trying to see his face, but every time I peeped out of the tiny curtain, my father yanked me back inside the jinrikisha.

“Keep your mind on our mission, Kathlene.”

“I’m trying my best, Father, but you’re not telling me everything,” I dared to blurt out. Worry for his safety made me anxious.

“I can’t. All you have to know is you’re my daughter and you’ll act accordingly.”

Angry, I crossed my legs, my black button boots melting into the softness of the floor mat. I wiggled about on the red velvet-covered seat, trying to get comfortable in my wet clothes and sinking down lower into the soft cushion. I didn’t mean to be disrespectful to my father, but I was frightened. Frightened of what lay ahead.

I looked over at him and went over in my mind the events of the past day and night, trying to understand why he’d ordered me to pack my things because we were leaving Tokio at once. Next he ordered our housekeeper, Ogi-san, to pack rice, pickled radishes and tiny strips of raw fish into lunch boxes so we’d have something to eat on the day-long journey ahead of us.

He’d hardly spoken a word to me since we left. I wished he would confide in me, as he often did. This time he said nothing. Instead, he ordered me to speak to no one.

“My life depends on it, Kathlene,” he told me, putting his right hand under his jacket, as if he hid a pistol there.

My father was a handsome man, but at this moment he looked funny, strange even, bent over in the tiny jinrikisha. His clean-shaven face was wet with rain, his head hatless, his hair matted. His rich, black overcoat glistened with dewy pearls of raindrops. Even his black leather gloves shone with a rainy sparkle that played with my imagination, hypnotizing me into believing this whole escapade was a game. That nothing was wrong.

For what could go wrong in this beautiful, vibrant green land of misty plum blossoms? Lyric bells played a song on every breeze and the sweep of brilliant red maple leaves harmonized with the melody.

To me, it was a gentle land inhabited by a gentle people. And the only home I’d known since my father brought me to Japan with my mother when I was a small child. He’d known my mother was sickly and the ocean voyage from San Francisco had weakened her, but Mother wouldn’t stay behind without him.

So she came. With me. My heart ached with fresh tears, trying to remember my mother. It was difficult for me. She died that first year. I never shared my pain with anyone. Especially my father. He seemed to hold back his feelings around me, yet I knew he loved me. That was why I didn’t understand why he acted so strangely.

What have you done, Papa? I longed to ask him, but I didn’t. I never called him “Papa” to his face. It was a term he didn’t understand. He was my father. No more. No less.

I held on to the seat as the thin, rubber-treaded wheels of the jinrikisha bounced over what must be a small bridge. I couldn’t resist peeking out the curtain again, but this time my father didn’t pull me back. I sighed, delightful surprise catching on my breath. Though it was near sunset, I marveled at the western hills throwing purple-plum shadows on their own slopes, the long stretch of wheat fields turning to a lake of pure gold by the drenching rain.

A splatter of rain hit my nose and I wiped it off, muttering in half Japanese and half English. I switched easily between the two languages, since I’d learned both at the same time. Japan had been my home for most of my life and I was proud of my linguistic ability. Though with my blond hair, I often felt strange in this land of dark-haired women. My father assured me I was going to be as pretty as my mother, though he knew nothing about my desire to become a geisha. I smiled. I know Mother would have approved. Geisha were admired by everyone. They were the most beautiful women: the way they walked, their style and their spirit.

I sighed again, letting out my frustration in one big puff of air. I’d never be a geisha if I stayed in a nunnery. I’d be doomed to a life of joyless obedience, days praying and nights filled with loneliness. The beauty and brightness of the world of flowers and willows promised so much more. For now, my dream to be a geisha was only that. A dream.

We’d been riding for an hour, maybe longer, and the green shadow and gloom hung lower in the sky. I could hear the cawing of the ravens living in the old pine trees as if it were a solemn chant welcoming me to my new home.

No, wait, it wasn’t the birds I’d heard, but a loud bronze gong sounding a long note as rain pelted the oilcloth hood covering us. I held my breath as the driver continued pulling the jinrikisha along the narrowest of lanes with trees arching overhead, blocking my view of the darkening sky.

Then as if by the will of the gods, the rain stopped. I listened and I could hear the noise of running water from little conduits by the road, nearly hidden by overgrown fernlike plants as we traveled deeper into the hills.

A little farther down the lane, the road came to an end.

The driver stopped and I could feel the vehicle being lowered to the ground. I breathed out, relaxed.

“We’re here, Kathlene,” Father said, though I didn’t hear relief in his voice.

“At the nunnery?”

“Yes.”

I wanted to run away. Far away.

I was aware of the stillness surrounding me as I got out of the jinrikisha after my father, my legs stiff and my feet wet. I looked around. Where was everyone? Monks and nuns could usually be found walking the grounds with their curious, basket-shaped straw hats hiding their faces, their palms outstretched for alms, their voices low and begging.

All I saw was a dull red gate standing in front of a stairway of steep steps leading up to a small temple with vermilion pillars supporting it with a heavy, gray-tiled iron roof. Hundreds of lanterns dotted the grounds, along with several statues of heavenly guard dogs perched on stone pedestals.

I almost expected to hear them start barking as my father bounded up the steps, his feet moving at a fast pace, his mood somber. I started to follow him, when I saw the most exquisite scarlet wildflowers growing in clumps around the steps. I was drawn to the flowers, their long, soft petals reminding me of the finest silk worn by the geisha. Dazzled by their beauty, I bent down to pick a cluster of flowers when—

Whooossshhh. Something flew by my face so fast I could feel a tiny breeze fanning my cheek. I touched my skin in surprise, and before I could reach down and pick the flowers, I heard the unmistakable crrraaacck of stone hitting stone and exploding into hundreds of fragments.

I turned my head around in time to see the head of a dog statue toppling from its body and landing on the ground, shattering into big, ugly pieces. Then I heard a voice cry out, “Don’t touch the flowers!”

Startled and shaken down to my pantaloons wet from the rain, I jumped back, looked around, and was surprised to see the jinrikisha boy. He had yelled out to me, breaking the stillness around us.

“Why?” I asked, not understanding. “What’s wrong?”

“Those flowers are poisonous,” the boy said, bowing, knowing he’d spoken out of turn, but as I was about to find out, most fortuitous for us.

“Poisonous?” A commotion in the sky caught my attention. I looked up to see hundreds of pigeons flying over my head, the whirring of their wings mixing with the neighing of horses. Horses? The nuns shunned the luxury of any kind of conveyance and walked everywhere. Where did the horses come from?

“These flowers will inflame your hands,” the boy said, “and make them red.” Then he bent down low and whispered hotly in my ear, “I’d like to make your cheeks blush red with the heat of passion.”

“Oh!” I turned away, my skin tinting a dark pink. A silver-spun mist of anticipation slithered across the soft opening between my legs. Then a hot boiling steam spread across my belly, arousing my senses. I was unsettled by the boy’s crude remark, but I was more disturbed by my own reactions. A new strangeness arose within me, which didn’t seem unnatural. I experienced an overwhelming desire to surrender to the raw, sexual energy of this new discovery. Yet I was afraid of some dark emotion I couldn’t define. Afraid of losing control of myself, doing wild things I’d never thought of until now, and then wanting more.

Summoning the courage to confront the need as well as the desire stirring within me, I dared to look down at the large bulge between the boy’s legs, my heart beating faster when—

“Get back into the jinrikisha, Kathlene!” I heard my father shouting in English. His voice sounded desperate. “We’re leaving!”

I saw him running back down the stairs, taking them two, three steps at a time. Something was horribly wrong.

“What’s going on?” I asked, a fresh wind picking up and bringing the smell of sweating horseflesh with it, the pungent odor lingering under my nose. I hadn’t imagined the sound of horses after all.

My father grabbed me by the arm, then pushed me into the jinrikisha. “They were waiting for us, the devils. Get in, now!”

I did as I was told, fear making my heart beat faster, my father shouting to the boy to take off down the narrow lane. I dared to look out the oilcloth curtain, my eyes searching out the steep stairway leading to the temple before my father pulled me back into the jinrikisha. I saw dust kicking up. Someone was coming after us.

The boy was running. Running. I could hear his heavy breaths comingquickly, then quicker yet.

“Who was waiting for us in the temple, Father?”

Faster, faster, the boy ran. He must have the strength of the gods in him.

“I’m certain it was the Prince’s devils. If that boy hadn’t yelled out and startled the birds and surprised their horses, I hate to think what would have happened to us.” He put his arm around me, holding me tight, though I could feel him shaking. “How they knew we were coming here, I don’t know.”

Heavy breaths. Thumping bare feet. The boy didn’t stop running.

“Ogi-san.”

I reminded my father the old woman must have listened to us making our plans and heard him mention the name of the nunnery.

He nodded. “The woman isn’t a bad sort, but she’s weak. The Prince’s men will stop at nothing to find us, including threatening her with the sword to loosen her tongue.”

I dared to ask, “What will happen if they catch us?”

He flinched as if he couldn’t bear to think about it. “I will die protecting you, my daughter.”

“They won’t catch us,” I said. “The boy will outrun them.”

“You have much faith in this boy,” Father said, then looking out the oilcloth curtain, he finished with, “Though I don’t believe his feet will save us, but his wit.”

“What do you mean?”

“Look for yourself.”

I peeked through the oilcloth and let out a surprised sigh when I realized we had stopped under an arched bridge, the deep shadows and green twilight of the groves showering us in oncoming darkness.

“We’re under a bri—”

“Wait!” my father ordered. “Listen.”

Seconds later we heard the pounding of horses’ hooves galloping over the bridge, our pursuers rushing overhead. Their hoof-beats pounded and pounded upon the wooden bridge, sounding like a stampede.

I counted three, maybe four horses, their riders shouting and digging their heels into the flanks of their mounts. Now I understood the old Japanese proverb about why all bridges were curved: Because demons could only charge in a straight line.

Demons like the men following us.

I kept still as my father held me in his arms and the air filled with silence. I felt secure, holding on to him, certain he would get us to safety.

But the events of the last twenty-four hours weighed heavily upon me. The danger had passed, if only for a short time. I began to calm down, relax. I allowed my tired body to drift off, sleep for a minute, maybe two, but I couldn’t rest. Always in the back of my mind, I was asking, asking, why were those men following us? Why?

What wouldn’t my father tell me?

2

The soft hush of a breath lingering in the night air, the scent of forbidden love hanging still upon a wayward breeze, a stifling heat making lovers sweat under mosquito nets as they thrust and writhed in passion. All this cast a sensual spell over me as we returned to the city of Kioto.

Raindrops, big and plump, landing on gray-tiled roofs. Caterpillars humping along the road. A night filled with fear, but also with magic.

The magic of the fairy tale yet to come.

But first—

“We’re not out of danger yet, Kathlene.”

“I know, Father.”

“You’ve always trusted me, my daughter.”

“Yes, Father.”

“Do you believe whatever I do, it’s because I love you?”

“Yes.”

“Even if I take you to a place that may be unseemly for a young girl?”

“Yes.” I held my hand to my chest as if to quiet my rapidly beating heart. I sensed something wonderful and strange was about to happen to me. A mystery, but what?

“I’ve been thinking, my daughter, and questioning. I wouldn’t see you hurt for anything in the world, yet I’m faced with the most difficult decision of my life.”

“What decision?”

“Where we can hide. No place is safe from the Prince’s devils. Unless—”

I took my father’s hand in mine. It was cold. “Yes, Father?”

“Unless we hide in a place where no one would think of looking for us, a place filled with the secrets of men’s desires, a place devoted to the seeking of pleasure, a place I never dreamed I would expose my daughter to seeing. Yet what choice do I have? If the Prince’s devils find us, they will invoke the most unspeakable sin upon—”

“No! They won’t find us. They won’t.”

He held me tighter, so tight I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t understand my father’s turmoil. What was he talking about? Where was hetaking me?

“Don’t judge me, Kathlene. Understand I’ve thought long and hard about what I’m about to do, and though I know you’ll be exposed to a certain kind of life that doesn’t please me, I have no other choice.”

“Where are we going?”

“To the Teahouse of MikaeriYanagi.”

“Mikaeri Yanagi,” I repeated. “What does that mean?”

“The Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree.”

The Look-Back Tree? I questioned. Look back at what?

“Simouyé will hide us,” he continued. “I’m certain of this.”

“Simouyé?” I asked, noting with interest my father didn’t follow the tradition of adding the honorific san to this strange name. A name that had no meaning to me but sounded very pleasing to my ears the way Father said it.

With a late-night summer rain come to visit us and the thumping of the jinrikisha clattering on the wet street, my father squeezed my hand. “Simouyé is a great friend, Kathlene, and a woman I can trust—” he looked down at me and I saw tenderness in his eyes “—with my greatest possession.”

“Father…” I started to ask, wondering who was this Simouyé. A teacher? A friend? Or something more? Something mysterious?

A geisha?

“Yes, Kathlene?” Father asked.

I took a deep breath, then found the courage to ask him, “Have you ever visited a geisha house?”

Taken aback by my question, swallowing a hard lump in his throat, he hesitated, then answered me with, “A geisha is a woman of high refinement and irreproachable morals. Though she often falls in love, sometimes the man she loves is unable to care for her as he wished he could do.”

“I want to be a geisha,” I said with the confidence of my youth.

He looked shocked at my words. “You? My daughter, a geisha? That’s impossible. You’re gaijin, a foreigner. According to tradition, a gaijin can’t become a geisha,” he said, tugging on my blond hair.

I succumbed to a sadness unnoticed by my father, my shoulders slumped, my smile turned upside down. With his spirits lifted by his amusement at my admission of wanting to be a geisha, my father sat back and expelled a deep breath and fell into silence.

Just as well. My ears were stinging from his words.

Gaijin can’t be geisha, he said.

I don’t believe him. When all this trouble is over, I’ll show him I can be a geisha. When I grow up—

Wait a minute. Wait.

Something interesting was going on. Peeking out of the oilcloth curtain, I became intrigued with the elegant-looking paneled houses situated along a canal with high walls surrounding them. In this part of Kioto, the streets were small and narrow and filled with dark wooden houses. I could see each multistoried house situated along the canal had a wooden platform in back, extending out over the wide riverbank. The colorful, red paper lanterns on the square verandas, swinging back and forth in the rain, held my interest. Big, black Japanese letters danced in bold characters on the lanterns. The rain blurred the writing, but the words were names. Girls’ names. I remembered seeing similar lanterns in the Shinbashi geisha district in Tokio.

I smiled. I knew where we were from the books I’d read. Near Gion, in Ponto-chô. The geisha district near the River Kamo. A special thrill shivered through me, knowing I was here in this magical place.

I slid to the edge of my seat and stuck my head out the window. Big raindrops hit my nose, my eyelids, my lips, giving me a taste of the strangeness of this place called Ponto-chô, my eyes dancing from one house on the river to the next. So much about the world of geisha excited me. I wondered which one was the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree as the jinrikisha driver pulled us closer and closer to our destination. He hadn’t stopped running since we left the countryside, and more than once I saw him looking back at me when I poked my head out of the oilcloth curtain.

The sight of him made me take even more delight in the idea of hiding in the teahouse. If the boy could run and run and run, I imagined what pleasures he could sustain for a long time under the silkiness of a futon.

What if I were a geisha and he were my lover?

What delights awaited me, delights hidden under the tiniest bit of bluecloth barely covering his penis?

I leaned back into the jinrikisha as thunder rolled and rolled overhead. I wasn’t frightened. The sound of the rain ripping open the clouds made me imagine the thunder was the power of a samurai warrior driving his manly sword into a sighing maiden. Thrusting rain. Drenching rain.

Oooohhh, I wanted to feel these pleasures, but my heart was heavy, wondering if my father and I would be safe in the teahouse.

I closed my eyes and let the rain hit my face, wishing the danger would pass, wishing I could change the way I looked so they couldn’t find me, wishing the raindrops could sculpt my features like a geisha with high arched brows, winged cheekbones and bold carmine lips. Geisha were like the rain, I believed, with their skin so transparent and beautiful, colorless yet filled with hues of blue and red and yellow. How I wished I could be a geisha. To me, a geisha was like a fairy princess, pure and untouched, until the handsome prince sought her for a bride. Then he’d whisk her off to a castle surrounded by a moat, like the palace I’d read about in the days when Tokio was called Yeddo, a palace with so many rooms no one ever lived long enough to see them all. And I’d have kimonos woven with golden threads and dazzling rice ornaments for my hair made out of the purest white diamonds and the deepest black pearls.

And the man I loved would lie next to me under the silkiness of the futon, our bodies naked, our hands exploring each other. I’d know the ultimate joy of pleasure of feeling the thrust of a man’s penis inside me, that elusive feeling I’d begun to understand and craved deep in my soul, an ache that wouldn’t go away.

The jinrikisha boy turned down a tiny canal street into an alley and down a narrow lane, then crossed a small bridge before stopping before a teahouse hidden behind high walls. A great willow swayed in the night breeze. Rose and yellow lights burned behind the panes of paper.

I held my breath, lest the dream faded. I had the strangest feeling I’d stumbled into a fairy tale.

“The child can’t stay here, Edward-san,” the woman said in an abrupt manner in rapid Japanese, her hands f luttering around her.

“I have no choice, Simouyé-san,” my father insisted in a harsh voice. Then softer, he said, “I must ask you to do this for me.”

“I can’t. If the Prince’s men are searching for you everywhere in the city, they will find her here.”

“Not if you disguise her with a black wig and put a fancy kimono on her.”

A black wig? I tried to keep in the shadows, but the woman named Simouyé wouldn’t stop looking at me. That surprised me, since that wasn’t the Japanese way. Yet I couldn’t stop staring at her across the room almost as intensely.

I dared to inch closer to inspect the beautiful woman with the tight knot of black hair fixed high on the top of her head who spoke with such vehemence against my staying in the teahouse. She wore no makeup except for a light dusting of rice powder on her cheeks, but I swore her lips were dark red, though I couldn’t see her mouth. Simouyé pressed her lips together when she spoke and waved her arms around her. Her dark mauve kimono with sleeves reaching down to her hips fit her snugly, showing her still-girlish figure. Though she wore only white socks on her small feet, she seemed taller to me than most Japanese women.

Or was it because of the way she stood? Proud and straight. As if she knew her place, and that place was close to the gods.

She moved closer to me, startling me. Or was it an optical illusion produced by the embroidered birds on her sash, fitting tightly around her midriff, that made her seem like she was floating on air?

The intent of her words was no illusion.

“If your daughter stays here, Edward-san, you’re not thinking I would engage her as a maiko?” Simouyé asked, her hand flying to her breasts. My eyes widened with surprise. A maiko, I knew, was the localism for an apprentice geisha. I choked with joy at the thought, but the idea didn’t please the woman.

You don’t have to worry. My father would never permit me to become ageisha.

“That’s exactly what I mean, Simouyé-san,” my father answered.

My mouth dropped open, not believing my father had said the words I yearned to hear.

He continued, “As a maiko she wouldn’t be subjected to any—” he hesitated, then chose his next words with care “—unpleasant or awkward situations with your customers.”

My mind was so focused on this new turn of events, so startled by what my father had said, I hadn’t realized his hand was caressing the woman’s neck, as if this was a prelude to an intimate moment they’d previously shared. Then he moved his hand down to the V-shaped opening of her kimono, lingering there, then brushing her breasts with the tips of his fingers. The woman drew in her breath. I wanted to look away. My father was doing this?

I kept staring at the woman. Her sash was tied low, signifying her maturity, the curve of her breasts not flattened, allowing for her nipples to become taut and pointy through the kimono. She wore the thinnest silk undergarment underneath. I saw her shudder with pleasure.

“Even if I wish it, Edward-san,” Simouyé whispered, “I can’t allow the child to stay here. She doesn’t understand our ways.”

“She will learn. These high walls hide many secrets.”

“Yes, Edward-san, many secrets. Inside this world one sees only the mask of femininity. A geisha never shows her true self to her customer but bends as the willow, pleasing those who are often undeserving of such pleasure. Is that the kind of life you wish for your daughter?”

My father paused, his body stiffening, his hands clenched at his sides. I thought he was going to look at me, but he didn’t.

Say yes, Papa, please say yes.

“I’m desperate, Simouyé-san,” he said. “There’s no place else where she’ll be safe. I’ll return for her as soon as I can. Until then, you must help me.”

“What about the jinrikisha boy?”

“Hisa-don won’t speak about tonight. He knows his place.”

“That’s true, but—”

“Please, Simouyé-san, I’m begging you to help me save my daughter.”

The woman wasn’t convinced. “Our lives within these walls are very strict, Edward-san. If I say yes to your request, your daughter will have to follow all the rules of a maiko so as not to arouse suspicion. She must learn by observation by first becoming a maid and working long hours, but she’ll become a stronger woman. She must study the lute, the harp and dancing. She must learn the most polite language of geisha, where everything is hinted at and nothing is said directly, as well as respect and responsibility for her elders. She must also learn the art of wearing kimono, and be as pure as one who has not granted the pillow.”

This time I drew far back into the shadows, hiding from the woman’s scrutiny. My father’s intimate actions toward the woman had disturbed me, but this conversation disturbed me more. I could guess what granting the pillow meant. Something silky and warm and wonderful between a man and a woman snuggling up in a futon, hands groping, flesh touching. My heart pumped wildly and a warm flush pricked my skin pink. Would my education in the teahouseteach me about making love to a man?

Fueled with excitement, I pondered this new and interesting situation: If Simouyé agreed, I could stay in the teahouse and learn the ways of the geisha. It was both wonderful and frightening at the same time.

A slight noise drew my attention and my eyes darted to the other side of the room. I heard a knock, then the sound of a rice-paper door sliding open. The heavy rains must have prevented the geisha from changing their screens and doors to summer bamboo screens, a custom routinely followed to ward off the summer heat and humidity. I stifled a giggle. I had also upset their routine. No wonder Simouyé wasn’t pleased.

A young woman entered on her knees through the paper door and bowed three times, her forehead touching the floor. She wore a dark blue silk kimono with a striped white-and-pink sash tied around her waist. She was plain-looking, but a sweetness about her drew my attention. Innocent, childlike.

The girl began serving tiny cups of tea, placing them on the low black-lacquered table, alongside a tray of sweetmeats shaped like fantailed goldfish. The sugar glistened on top like golden specks and made my mouth water.

The girl handed me a cup of tea, then a napkin, then a sweetmeat.

“Thank you,” I whispered in Japanese, then I bowed to the girl.

The girl blinked her eyes in surprise, then bowed again and said, “It is my pleasure.”

I started to bow again until I looked over at my father. I couldn’t put the tea to my lips or the sweetmeat in my mouth. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. My father and Simouyé were standing in the corner in the shadows, their bodies so close they touched in a most personal manner. The woman seemed unaware of my presence nor did she push away from the intimate caress of the tall American. He stroked her face, then brushed her lips with his fingertips and held her chin in his hands. She didn’t pull away when he slid his hands down to her hips, massaging her firm thighs, her rounded buttocks. Then, slipping his hand in the fold of her kimono, he touched her breasts, playing with them. I sensed the power of her raised emotions was difficult for the woman to suppress as she was accustomed to doing. I had the feeling she couldn’t maintain her composure much longer, yet she continued to speak in a soft voice, accenting her words.

“How much have you told the girl?” Simouyé asked, pulling away from his caress, though she didn’t object when he put his hands on her shoulders, his breath close to her face, his lips brushing the nape of her neck.

I opened my mouth, ready to ask Father what he was keeping from me, but the girl sitting next to me cleared her throat. I stared at the young maid as she put her finger to her lips, warning me to keep silent.

“What’s wrong?” I asked her, somewhat confused. Had I broken the geisha rules?

“I’m most sorry and beg your pardon,” the girl whispered, bowing. “I didn’t wish to offend you.”

I bowed, saying nothing. How could I have let my excitement to become a geisha make me forget my manners? The girl saved me from losing face by speaking to my father in a situation where I was supposed to remain invisible.

My actions hadn’t escaped my father’s eyes.

His stare was fixed on me, making my heart beat wildly in my chest, fluttering like a butterfly caught in a jar. He was aware of my language skills, so I wasn’t surprised when he turned back to Simouyé and said, “She knows my life is in danger.”

“Does she know you’re returning to America?” Simouyé asked, the words catching in her throat.

This time I couldn’t suppress the fear leaping into my heart as quickly as a rabbit fleeing the arrow of the hunter. This wasn’t what I’d expected to hear. I panicked.

“It’s not true, Father, is it?” I cried out, jumping to my feet, not caring if I was breaking the rules. My father was more important to me than rules. I rushed into his arms and pressed my cheek against his chest, sobbing, “You’re not going away, are you? Youcan’t.”

“Shouldn’t you tell her the truth?” Simouyé asked. This time her voice was stern, demanding.

“No, she’d be in greater danger if she knew,” my father answered. “She must stay here with you, Simouyé-san, and learn to be a maiko. Leaving her here is the only way I can escape from the Prince’s devils.”

The woman bowed and I could see it was with great effort when she said, “As you wish, Edward-san.”

I didn’t want to believe this was happening to me. Couldn’t.

“I want to go with you, Papa,” I blurted out without thinking, pushing aside my dream to become a geisha, my heart speaking out to my father as I grabbed on to the sleeve of his coat. He noticed my use of the endearment and it startled him. I thought he was going to change his mind. Instead, he cupped my face in his hands and looked into my eyes. I couldn’t see his face through my tears, flowing as fast and sure as the rain beating down upon the wooden teahouse, but I could hear his words.

“I must return to America, Kathlene, until I can find a way to right the wrong I’ve done.”

“You’ve done no wrong, Father. You’re good and kind.”

“I wish it were true, Kathlene, but I’ve failed you this time. And for that reason, I must go.”

“Why can’t I go with you?” I cried out, my voice carrying throughout the teahouse, inviting peeping eyes through the paper doors, listening. Young, curious girls huddled together outside the half-open sliding door, staring out at me, the blond gaijin, but I paid them no attention. Yes, I wanted to be a geisha, but my father was moreimportant to me.

“The danger is too great, Kathlene. I must travel quickly and not always in the most pleasant surroundings. You must stay here with Simouyé-san. She’s a good woman and will treat you like a daughter,” he said. Then he finished with, “You must do what she tells you, Kathlene, even if you don’t understand why. My life depends on it.”

“Is this the only way, Father?”

“Yes. I’ve never asked anything of you, Kathlene,” my father said, deepening his voice with a dark color I hadn’t heard before, ordering me not to disobey him. “But you know the ways of this land, and the importance of filial duty.” He stroked my hair with his fingers, pushing it away from my face and forcing me to look him in the eye. “Don’t bring disgrace upon us.”

Although I was often too curious for my own good, listening to Father speaking to me in such a demanding voice frightened me. Yes, I knew how important duty was in this land. The whole society was built on loyalty to one’s family.

I had no choice but to do as my father asked, though this was a strange proposition fate had dealt me. To achieve my dream to become a geisha, I must give up the one person in the world I loved the most. My father. What unholy trick were the gods playing on me?

With a tiny rattling in my throat, and though my self-control was barely holding, I managed to speak.

“I understand,” I said, feeling the weight of numerous pairs of dark eyes riveted on me, especially the young maid who’d held me back when I wanted to rush forth with my wild emotions.

“Are you certain you know what’s expected of you, Kathlene?” Father demanded, lowering his gaze to meet my eyes.

“I’ll do as you wish, Father,” I said with reverence, not understanding why I did so. Maybe it was because I was painfully aware of the importance of the situation, or the number of black-haired young girls peeping at me, their eyes taking in my uniqueness, their voices whispering. Perhaps for the first time in my life, I was pitted against something I could neither fully understand nor successfully defy. I couldn’t deny I was intrigued with the idea of joining these young women who so openly showed their curiosity of me.

They don’t believe I’ll stay. Americans are like butterflies flitting fromflower to flower, a Japanese poet once wrote, and as restless as the ocean. I must pull back my own restless feelings and wait. Wait for my father to return and wait for the day when I would become a geisha.

I let go of his coat.

My eyes blurred with tears I struggled not to let fall when my father kissed me on the cheek. Then without another word, he raced out the secret entrance of the teahouse and disappeared into the rain, into the night, into another world where I couldn’t go. The voyage back to America could take as long as eighteen days, Father had told me, the weather often cold and stormy. Although icebergs didn’t float down the shallow reaches of the Bering Strait, fierce winds blew through the gaps and passes in the Aleutian Islands and many ships were lost in the rough seas. I prayed my father’s ship wouldn’t meet such a fate.

I lifted my chin and pulled up my shoulders. It wasn’t the way of this land to show emotion in front of anyone. I forced myself to show courage and make my father proud of me.

Here at this late hour on this summer night in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, I would begin my training to become a geisha. Geiko, as the geisha were called in Kioto dialect. I’d learn to be the perfect woman in an artificial world where such a woman was schooled in the erotic, her mouth sensuous, her smile winning but discreet, her eyes sparkling, ready to seduce as well as to entertain.

I’d be taught to have better manners than anyone else but to also speak my mind, to laugh inan engaging manner and to be flirtatious. Every dainty gesture—whether it be the lowering of my eyes, the tilt of my head to show the exposed back of my neck, the sway of my long fingers—would complement the meticulous stylization of my training. I’d exude the art of sexual sublimation and function as a living sculpture of the female ideal, polished to perfection.

And always, above everything else, I would make men feel good. I’d learn how to entice them with the curves of my body and bring them sexual excitement. Like a bee savoring its first taste of the nectar or a hungry bird pecking at the peach and melting the soft pulp in its mouth, so the world of pleasure would be my world, embracing me like a lost daughter.

Gathering up my curious and girlish spirit and putting it away into a secret spot in my heart until I could let it run free once more, I turned to Simouyé and bowed.

“I’m ready to begin my training to become a geisha.”

3

Snip-snip. Snip-snip.

My stomach clenched with fear. What was that noise? It sounded like scissors cutting. I tried to open my eyes to see what was going on. I couldn’t. I lay helpless, unable to move, as if I were under a spell.

Then I heard a different sound. A sigh, then another, followed by more snip-snips and a paper door sliding open. A girl’s voice asked, “What are you doing, Youki-san?”

“Cutting off her golden hair.”

My hair? Oh, no! I struggled, struggled, but I couldn’t raise my arm to protect my hair.

“Why, Youki-san? She’s so beautiful.”

“Don’t you understand, Mariko-san? She’ll ruin everything for us with her hair the color of silken gold threads.”

Ruin what? I kept trying to open my eyes, move my arms, my legs. I couldn’t. My lids weighed so heavy on my eyes while the rest of my body lay helpless like the cold, slimy fish I’d seen tossed up onto the pier when Father took me down to the wharf to meet the ships arriving from across the sea.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t move. I lay on my back on a scratchy mat digging into my skin, shielded from its prickly weave by what I perceived to be a sheer kimono underrobe, its silkiness hugging my body. A cool breeze swept over my skin when someone walked near me. I heard the swish of long robes on the tatami mat and the glide of soft feet. Salty drops of perspiration wet my lips and drizzled down my chin. I let out my breath and relaxed. The girls had gone.

Where am I? What happened?

I remembered following Simouyé down a shining corridor and upstairs to a long, low room divided into three sections by screens of dull gold paper. Before she could stop me, I ran to the open balcony of polished cedar and looked out into the night, hoping to see my father. But he had vanished.

My heart ached so, I couldn’t help but sink down to my knees in front of a wall screen and claw at the delicate branches painted on it, crying. I prayed the gods wouldn’t look unkindly on my actions, but I had the strange feeling I’d never see my father again. My loss brought up so much anger in me, so much sorrow, I pushed aside everything the missionaries taught me. In my anguish, I grabbed the flower vase out of the alcove in the wall and threw it across the room to vent my fury. Simouyé stood and watched, her face showing no emotion, as was the way of the geisha. Panting, out of breath, my emotions spent, I stood there, watching her watching me. It was the most spiritual moment of my life up to that point. Strange, but that lack of emotion calmed me down, made me dry my tears.

I shivered now as the coolness played tag over my bare breasts, bringing my nipples to hardness like the buds of a cherry tree. A pleasant feeling washed over me as I began to move my fingers, then my toes. Were the gods releasing me from the sleep of dead spirits? If so, I must escape before the two girls returned. I wiggled my hips and the silk robe fell away from my belly. My entire body quivered as if I’d been touched by a probing hand. I spread the palm of my hand between my legs to cover myself and the softness of my bare skin slid under my fingers, then—

A gasp caught in my throat, pressing into my brain a truth I didn’t want to believe.

My pantaloons were gone. I was naked down there.

Where were my clothes? Yes, I remembered. Simouyé had called her house servant, Ai, to help me remove my wet garments. Ai said little, except to criticize anything done differently from the way it was done in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, and this included my request to keep my clothes. They disappeared along with the servant when I wasn’t looking. I was so embarrassed, standing naked in the cool room.

Was this part of my geisha training?

I wrapped myself up in the futon and, racing into the corridor, bumped head-on into the old servant woman. Mumbling about “stinking foreigners,” she gave me a white silk robe and a cup of tea with a strange taste that burned my lips. With Ai watching me, I finished the green tea—laced with rice wine, I’m sure—then fell into a deep sleep. I awakened when I heard the sound of the scissors.

I tried to sit up, but my muscles stiffened. I cursed the gods who tied me to the floor with invisible bonds from the effects of the strong drink. I tried to move again. Nothing. My breathing became sharper when I heard voices. Girls’ voices.

They were coming back.

“She’s done us no harm, Youki-san. Why do you wish to make her lose face?”

“Is your brain as soft as duck feathers, Mariko-san?” the girl named Youki scolded. “Don’t you know what the emperor has decreed?”

Mariko answered in a timid voice, “No.”

“He has much august respect for the ways of the Westerners and he has expressed his wish our men marry white women.”

I could hear Youki rattling on about how everything was changing because of these Westerners, these speakers of English, who talked nothing but politics at geisha parties and ignored the geisha and her accomplishments. I wanted to tell her what I thought, but the effects of the rice wine made me sluggish and fuzzy-headed.

“What can we do if the emperor wishes these marriages?” Mariko asked. “We’re servants.”

“I will soon become a maiko. And if the gods smile upon your plain face, Mariko-san, someday you’ll also be a maiko.”

“I wish to be a maiko with all my heart.”

“Then why do you want this girl to get all the attention, Marikosan? What will happen to us?”

“Don’t worry, Youki-san,” Mariko assured her. “As long as men have sexual desire, there will be geisha.” Her voice was childlike yet silky, soft and smooth. I detected a longing for fulfillment in the young girl that matched my own. I squeezed my eyes shut harder, saying a prayer she would help me.

“Okâsan, mama-san, says this girl is also going to be a maiko. That means someday she’ll be a geisha,” Youki said, her words filled with ire and contempt for what she saw as a direct threat to her future.

“Are you certain this is true, Youki-san?”

“You wait and see, Mariko-san. She will capture the hearts of all the men who come to the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree, and you and I will have nothing.”

“Nothing?” Mariko asked, her voice not believing. I began to lose hope she would help me.

“Nothing. No benefactor to give us a teahouse of our own when we’re old. We’ll be poor and worth nothing more than a sack of bones to be tossed to the dogs for their dinner. Is that what you wish, Mariko-san?”

Mariko was silent for a long moment, then she said, “The blond gaijin won’t do this to us, Youki-san. I know so in my heart.”

“I’m warning you, Mariko-san, we must rid ourselves of this girl or we’ll all pay a price to the gods who rule our fortunes.”

“No, Youki-san, I won’t let you do this terrible thing to her.”

“You can’t stop me—”

“I will stop you!”

A great rumbling followed, making my whole body shake, as if the teahouse were being torn apart by two wild animals. With great effort, I forced my eyes open.

It was true.

Two girls.

Fighting.

In spite of my drugged stupor, I could see the hazy shapes of the girls wrestling with each other, their long hair coming unbound, flowing down their backs like capes unraveling in a tempest storm. The pale yellow silk of one girl’s underrobe swirled around the pink damask kimono of the other as they pulled on the kimonos until they came undone and flew about them like the wings of birds trying to take off into flight.

Flashes of their nude skin startled me. I’d never seen girls my own age naked. My father wouldn’t allow me to attend the public baths. Bare young breasts, slim thighs, silky dark tufts of hair between their legs, they continued grappling at each other, pulling, tugging. Nothing could stop them. I suspected every inch of their beings was involved in gaining control of the other.

I flinched when I saw one of the girls grab the small scissors out of the other girl’s hand and throw them away. I tried to grab them, but the scissors slithered across the slippery floor beyond my reach. The two girls paid them no attention, pulling and grabbing at each other for what seemed like long minutes, their buttocks shaking, me watching, feeling a fluttering along my spine, as if I were awakening from a bad dream.

I’ve got to get those scissors.

My knees shook when I tried to stand up again, then buckled beneath me. My shoulders bent under the heavy weight of the liquor dominating my will, but I forced my left hand to raise slowly. Then I crawled to the spot where the scissors lay and saw my cutoff hair spread on the floor. Forget about the scissors.

I grabbed my hair. The long, blond strands slid through my fingers, but I held on to them. I heard one of the girls gasping for air when I saw her slip on the mat in her stockinged feet, knocking the breath out of her. I looked up in time to see the other girl fleeing through the paper door and sliding it shut. Then I heard the sound of feet running away.

“I have deep sorrow and must apologize for what Youki-san has done, Kathlene-san,” the girl said, breathing hard, bowing, her forehead touching the mat. She struggled to get her breath back. I know her. She was the young maid who helped me save face with Father.

“You know my name?” I asked.

“Yes.” Silence, then the girl said, “I’m called Mariko.”

“Thank you, Mariko-san.” I also bowed, though not touching my head to the mat, my gaze fixed upon the girl instead. In the dim and fluttering light I saw the red, bruising marks of the fight on her wrists and arms.

“You speak our language most precisely, Kathlene-san.”

I smiled at her compliment. It pleased me. “I studied your language at missionary school.”

The girl sighed. “I’ve often wished I were a boy so I could attend the Tokio School of English,” Mariko said with great expression. Then believing she’d said too much, she bowed her head and said in a submissive voice, “But I’m not worthy of such an honor. I’m a girl and don’t have the brain to learn about commerce and business and other things as boys do.”

“Why do you say such things about yourself?” I admonished her. “You’re as smart as any boy.”

Mariko thought for a moment, then with her eyes still lowered she said, “It’s written in Shinto belief women are impure.”

“Are you certain of that?” I asked, not wanting to offend her, but curious.

She nodded. “Buddhist teachings proclaim if a woman is dutiful enough, she can hope to be reincarnated as a man.”

“Dutiful? What does that mean?”

“I must do as my superiors have decreed.”

“And what’s that?” I asked.

“I’m born to please men, to make them feel pleasure when they mount me like a leaping white tiger,” she said without embarrassment, “to mix my honey with their milk.”

I lowered my eyes. The girl’s overt declaration about pleasing men made me uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to say, so I said, “I’m going to attend the Women’s Higher Normal School when my father comes back.”

“Please, I don’t wish to offend, Kathlene-san, but you’re pleasing your father by staying here,” Mariko offered without the least bit of sarcasm, “so are you not also pleasing men?”

I wanted to toss back a response but I was tired. Very tired. The girl’s puzzle resisted an easy answer. A more pressing question burst from my lips. “Why did you help me, Mariko-san?”

Mariko lowered her eyes, then shifted her slender body, allowing her shoulders to slump as if this was something she did at all times. “I know what it’s like to be separated from your family. It makes you different from the others.”

“Where’s your family?”

“Life in my country isn’t easy for anyone who is…dissimilar in any way,” Mariko said, not answering my question directly, which made me more curious about her. She didn’t explain what she meant, but I guessed what she was trying to tell me. Even in my small class of girls at missionary school, anyone who was different was pushed outside the accepted circle.

“I know all about your game of what you say, Mariko-san, and what you really feel.” I twisted my hair. It wasn’t all cut off, but I was still upset by what this Youki had done.

“To understand us, you must open your mind,” Mariko said, “and your heart.”

Following my instincts, I didn’t protest when Mariko bowed and motioned for me to sit down on my knees and remain there with the rustle of silk and the scent of jasmine in the air as I continued to stare at her. I wanted to learn about this strange new world of geisha and I sensed an ally in her.

I sat back on my heels, thinking. I didn’t believe anyone in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree but this girl wanted me to stay. Was she merely being polite to me, as was the Japanese way? I wouldn’t be surprised if later I found a knot tied in my clothes or lukewarm ashes under my bedding, common hints to urge unwanted guests to leave. But if I must be separated from my father until he came back for me, then I wanted to stay in the teahouse and become a geisha. Wanted it badly.

I wiped a hand across my face, hoping to stave off my weariness. I took a few breaths, shifting my weight, but still I suffered the inevitable onset of cramping in my legs. On the contrary, Mariko seemed relaxed and poised.

“Okâsan says Mallory-san won’t return for a long time.”

“That’s not true, Mariko-san,” I protested. “My father will come back for me. I know he will.” I clasped the small bundle of my shorn hair to my chest, my eyes filling with tears. I couldn’t help it. Let the girl think what she wanted. It wasn’t my cut-off hair that made me cry. It would grow back. It was the loss of my father that frightened me. Frightened me and made me sad.

“Okâsan says Mallory-san would never have left you in the floating world unless there was great danger.”

I squirmed. There was that word danger again. Mariko sat still, without moving, unnerving me further. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I rubbed my leg.

“Why do you call it ‘the floating world’?” I asked, hoping to take the girl’s attention away from watching me squirm in an uncomfortable position. Would I ever learn to sit as relaxed as she did?

“It’s simple, Kathlene-san. Our geisha world is like the clouds at dawn, floating between the nothingness out of which they were born and the warmth of the pending day that will disperse them.”

I didn’t understand what she was trying to tell me. My mind was dark and cloudy with worry. However curious I was about the geisha world, I couldn’t forget my father was on his way to Tokio then back to America.

“Okâsan says from this night forward we mustn’t speak of Mallory-san,” Mariko continued, then drew in her breath. Slowly.

I looked at Mariko, who was waiting for me to speak. Never speak of him again? I couldn’t. Couldn’t. Never speak of him again? I wasn’t ready to act as if my father never existed. I couldn’t dismiss the emotions pulling at my insides, so I asked her instead, “How long have you been in the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree?”

“Since I was five years old.”

“How old are you now?”

“Fourteen.”

“Fourteen?” I said, surprised. “You look much younger.”

“Okâsan says I’m like a wildflower springing up on a dung heap.”

I shook my head. All these strange ways of speaking confused me. “What does that mean?”

“That I don’t have the face nor the figure to be part of the world of flowers and willows, but if I have endurance I will grow up to be a geisha in spite of everything in my way.”

Disbelieving, I studied her soft moon face, round cheeks and tiny pink mouth. This girl was going to be a geisha? She was so young and plain-looking. I believed geisha were mythical creatures of great beauty who started the fashion trends and were immortalized in songs. They were the center of the world of style and often called the “flower of civilization” by poets.

I continued staring at her, shocked by the girl’s honesty. As if embarrassed by my stare, Mariko pulled her kimono around her nude bosom in a shy manner. I looked away, but I had new respect for this young girl. She reminded me of bamboo bending in the breeze. Strong but flexible.

I was also dying to ask her more questions about life in the geisha house.

“I’m curious, Mariko-san, why do you call the woman named Simouyé okâsan?”

“Many girls who come to the Teahouse of the Look-Back Tree to become geisha lost their families when they were very young and have never known their mothers. Simouyé-san nurtures us as if she were our mother,” Mariko answered with much feeling in her heart. I could see by the wistfulness in her eyes, like a leaf filled with dew after it falls from the tree, she was such a girl.

“Simouyé-san is a difficult woman to understand,” I said, thinking, then I found myself saying, “and very beautiful.” Why did I feel I had to add that? Because my father had touched the woman’s breasts, held her in an intimate manner? As if that excused his actions?

“Yes, she’s hard on us, Kathlene-san, but it’s our way that all geisha in the teahouse give Simouyé-san much respect and follow her authority, as they would their own mothers.” With her eyes lowered, her lips quivering, she tried to keep her emotions from spilling over into her words. “It pleases me that okâsan has said I’ll become a maiko soon, then a geisha in three years.”

“You’ll be a geisha in three years?”

Mariko, in that knowing Japanese way, must have sensed my perplexity at hearing her words. She added, “I have much to learn before I can become a geisha.”

I leaned in closer to her. She didn’t back away. “Tell me, Marikosan. I want to know everything about becoming a geisha.”

She explained how an apprentice geisha was expected to be both observer and learner, that words didn’t have the same power as a telling glance or sway of the head.

“Geisha must learn how to open a door in the correct manner,” Mariko continued, “to bow, to kneel, to sing, to dance, to have undeniable charm, but it’s the main purpose of a geisha to converse with men, to tell them jokes, and be clever enough never to let them know how clever a geisha is.”

“How does she do that?” I challenged.

Without any shyness, Mariko said, “A geisha learns many ways to please a man, Kathlene-san. She presses her body against him and says something outrageous, then she allows him to slip his hand into the fold of her kimono and touch her bare breasts as she pours him sake.”

I knew my mouth was open, my eyes wide, but I couldn’t help it. I never expected to hear anything like this.

“What else does a geisha do?” I asked.

“A geisha must also master artistic skills like flower arranging and tea ceremony,” Mariko said without hesitation. “Okâsan says these skills are the most important treasure in a geisha’s life.”

“More important than falling in love?” I heard the plaintive cry in my voice, but I couldn’t help it. My image of the geisha as a fairy-tale princess was dissipating into thin air, like a wisp of smoke hanging from the end of an incense stick.

“Yes, Kathlene-san. Okâsan says geisha don’t fall in love with men. They fall in love with their art.”

An ongoing sense of apprehension settled over me, yet I couldn’t resist asking, “Do you think I can become a geisha?”

“That would be difficult, Kathlene-san. Okâsan is very strict with us.”

“She can’t be worse than the teachers at the missionary school,” I said, remembering the stodgy English women with their padded bustles widening their hips and woolen rats tucked into their hairdos.

“The stricter your teachers are, okâsan says, the more you will learn, and the better geisha you’ll become and…”

Mariko hesitated.

“And what?” I asked, hanging on to her words.

“You must follow our way of doing things…and the rules.”

“Rules?” I made a face. I found it hard to follow rules of any kind, having had no mother to guide me. “What kind of rules?”

After thinking a moment, Mariko rushed forth with a list that made my head spin. “Geisha must get up in the morning no later than ten o’clock, straighten their clothes, then clean their rooms, wash their bodies, paying special attention to their teeth and their dear little slits—”

“Their what?” I’d never heard that term before and it shocked me, but it also piqued my interest about obeying the rules of the teahouse.

“You know…down there.” She pointed to her pubic area. I nodded and she continued, “…making certain their pubic hair is properly clipped—”

I gasped, intrigued with this rule, but Mariko continued without drawing a breath.

“—fix their hair, pray to the gods, greet okâsan and their geisha sisters, then have breakfast of bamboo shoots and roots—”

“Is that all you eat for breakfast?” I dared to ask her.

Mariko hesitated, then shook her head. I smiled. So, she was teasing me. Her playful spirit surprised me. Life in the geisha house would be fun with her.

She continued with, “A geisha must also be careful not to have caked face paint under her fingernails or splotched on her earlobes. She mustn’t have smelly hair, for that is a geisha’s disgrace, and she must be sure to take her bath in the public bathhouse by three o’clock. And she can’t use familiar terms with her manservant who carries her lute, lest anyone sees them and forms a bad impression.”

“I’m afraid I’ve already made a bad impression on your okâsan, acting like I did,” I blurted out, getting to my feet. My movements were quick and not too graceful. Would I ever learn to move like a geisha? “And that girl, Youki-san, she doesn’t like me either.” I rolled my cut-off hair into a ball and tied it with my kimono ribbon. I had nothing to hold my kimono closed to hide my nudity, but I felt more naked without my hair.

“Youki-san wishes you no harm,” Mariko said, surprising me.

“How can you say that? Look what she did to my hair.” I held up my cut-off strands. Why would she protect the girl?

“She’s very frightened, Kathlene-san. If she doesn’t become a geisha, she can’t work off her debt.”

“Debt?”

“She was sold by her parents to a man who buys young girls for a great sum of money. She must earn that money back from her work as a geisha.”

“That doesn’t excuse what she did to me, Mariko-san,” I interrupted her.

Mariko bowed her head. “Yes, Kathlene-san, but if she doesn’t become a geisha and get a benefactor to help advance her career, she’ll be sent to the unlicensed quarters of Shimabara as a prostitute.”

I dared to ask, “What will happen to her there?”

“She’ll be put into a bamboo cage and made to blacken her teeth and shave the hair between her legs and pleasure the penises of many men in one night.”

“Are you certain of this?” I asked, putting my bundle of cut-off hair down to my side.

Mariko nodded. “It’s true. We can’t let this happen to her, although there are those in the teahouse who report everything to okâsan.” I had no doubt she meant Ai, the handservant. “Youki-san will be in big trouble when okâsan hears about what she’s done tonight.”

“What can I do?”

“Go to okâsan and tell her you accept Youki-san’s apology.”

I made a face. “What apology?”

Mariko smiled. “The one Youki-san will give you when she finds out you helped her.”

I shook my head. “I don’t understand, Mariko-san. You want me to accept an apology that’s not been offered yet?”

“You must try to understand us, Kathlene-san. It’s the way of the geisha to bond as sisters.” Mariko lowered her eyes. “It’s the root of our geisha society for the experienced one to become the big sister to the new geisha, no matter what their ages.”