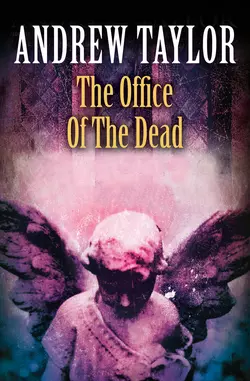

The Office of the Dead

Andrew Taylor

The final novel in Andrew Taylor’s ground-breaking Roth trilogy, which was adapted into the acclaimed drama Fallen Angel. A powerful thriller for fans of S J Watson.Janet Byfield has everything Wendy Appleyard lacks: she’s beautiful; she has a handsome husband, a clergyman on the verge of promotion; and most of all she has an adorable little daughter, Rosie. So when Wendy’s life falls apart, it’s to her oldest friend, Janet, that she turns.At first it seems as to Wendy as though nothing can touch the Byfields’s perfect existence in 1950s Cathedral Close, Rosington, but old sins gradually come back to haunt the present, and new sins are bred in their place. The shadow of death seeps through the Close, and only Wendy, the outsider looking in, is able to glimpse the truth. But can she grasp it’s twisted logic in time to prevent a tragedy whose roots lie buried deep in the past?

ANDREW TAYLOR

THE OFFICE OF THE DEAD

Dedication (#u6cfbd593-24d9-5a51-89af-a13e06a77d25)

For Vivien, with love and thanks

Contents

Cover (#ua12aac0a-8946-5794-bec3-97fbbf13653c)

Title Page (#u31432328-9451-56cb-b336-214adc7007d8)

Dedication

Part I: The Door in the Wall

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Part II: The Close

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Part III: The Blue Dahlia

44

45

46

47

48

49

About the Author

Author’s Note

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART I (#ulink_5ebfc77c-7226-50a4-ac10-314986747270)

1 (#ulink_441f76c4-9005-5763-8e89-79da8452c421)

‘I’m nobody,’ Rosie said.

It was the first thing she said to me. I’d just pushed open the door in the wall and there she was. She wore red sandals and a cotton dress, cream-coloured with tiny blue flowers embroidered on the bodice, and there were blue ribbons in her blonde hair. The ribbons and flowers matched her eyes. She was very tidy, like the garden, like everything that was Janet’s.

I knew she was Rosie because of the snapshots Janet had sent. But I asked her name because that’s what you do when you meet a child, to break the ice. Names matter. Names are hard to forget.

‘Nobody? I’m sure that’s not right.’ I put down the suitcase on the path and crouched to bring my head down to her level. ‘I bet you’re really somebody. Somebody in disguise.’

‘I’m nobody.’ Her face wasn’t impatient, just firm. ‘That’s my name.’

‘Nobody’s called nobody.’

She folded her arms across her chest, making a cross of flesh and bone. ‘I am.’

‘Why?’

‘Because nobody’s perfect.’

She turned and hopped up the path. I straightened up and watched her. Rosie was playing hopscotch but without a stone and with an invisible pattern of her own making. Hop, both legs, hop, both legs. Instead of turning to face me, though, she carried on to the half-glazed door set in the wall of the house. The soles of her sandals slapped on the flagstones like slow applause. Each time she landed, on one foot or two, the jolt ran through her body and sent ripples through her hair.

I felt the stab of envy, almost anger, sharp as John Treevor’s knife. Nobody was beautiful. Oh yes, I thought, nobody’s perfect. Nobody’s the child I always wanted, the child Henry never gave me.

I’d been trying not to think about Henry for days, for weeks. For a moment his face was more vivid than Rosie and the house. I wished I could kill him. I wished I could roll up Henry and everything else that had ever happened to me into a small, dark, hard ball and throw it into the deepest, darkest corner of the Pacific Ocean.

Later, in one of those fragmentary but intense conversations we had when Janet was ill, I tried to explain this to David.

‘Wendy, you can’t hide away from the past,’ he said. ‘You can’t pretend it isn’t there, that it doesn’t matter.’

‘Why not?’ I was a little drunk at the time and I spoke more loudly than I’d planned. ‘If you ask me, there’s something pathetic about people who live in the past. It’s over and done with.’

‘It’s never that. Not until you are. It is you.’

‘Don’t lecture me, David.’ I smiled sweetly at him and blew cigarette smoke into his face. ‘I’m not one of your bloody students.’

But of course he was right. That was one thing that really irritated me about David, that so often he was right. He was such an arrogant bastard that you wanted him to be wrong. And in the end, when he was so terribly wrong, I couldn’t even gloat. I just felt sorry for him. I suppose he wasn’t very good at being right about himself.

Nobody’s perfect.

2 (#ulink_d76fd808-b0e4-5454-a95d-e8b19754919d)

When I was young, the people around me were proud of their pasts, and proud of the places where they lived.

My parents were born and bred in Bradford. Bradford was superior to all other towns in almost every possible way, from its town hall to its department stores, from its philanthropists to its rain. Similarly, my parents were quietly confident that Yorkshire, God’s Own County, outshone all other counties. We lived in a tree-lined suburb at 93, Harewood Drive, in a semi-detached house with four bedrooms, a Tudor garage and a grandfather clock in the hall.

My father owned a jeweller’s shop in York Street. The business had been established by his father, and he carried it on without enthusiasm. He had two interests in life and both of them were at home – his vegetable garden and my brothers.

Howard and Peter were twins, ten years older than me. They were always huge, semi-divine beings who took very little notice of me, and they always will be. I find it very hard to recall what they looked like.

‘You must remember something about them,’ Janet said in one of our heart-to-hearts at school.

‘They played cricket. When I think about them, I always smell linseed oil.’

‘Didn’t they ever talk to you? Do things with you?’

‘I remember Peter laughing at me because I thought Hitler was the name of the greengrocer’s near the station. And one of them told me to shut up when I fell over on the path by the back door and started crying.’

Janet said wistfully, ‘You make it sound as if you’re better off without them.’

That’s something I’ll never know. When I was ten, they were both killed, Peter when his ship went down in the Atlantic, and Howard in North Africa. The news reached my parents in the same week. After that, in memory, the house was always dark as though the blinds were down, the curtains drawn. The big sitting room at the back of the house became a shrine to the dear departed. Everywhere you looked there were photographs of Peter and Howard. There were one or two of me as well but they were in the darkest corner of the room, standing on a bookcase containing books that nobody read and china that nobody used.

Even as a child, I noticed my father changed after their deaths. He shrank inside his skin. His stoop became more pronounced. He spent more and more time in the garden, digging furiously. I realized later that at this time he lost interest in the business. Before it had been his duty to nurse it along for Peter and Howard. Without them the shop’s importance was reduced. He still went into town every day, still earned enough to pay the bills. But the shop no longer mattered to him. He no longer had any pride in it. I don’t think he even had much pride in Bradford any more.

In my father’s world girls weren’t important. We were needed to bear sons and look after the house. We were also needed as other men’s objects of desire so the men in question would buy us jewellery at the shop in York Street. We even had our uses as sales assistants and cleaners in the shop because my father could pay us less than he paid our male equivalents. But he hadn’t any use for a daughter.

My mother was different. My birth was an accident, I think, perhaps the result of an uncharacteristically unguarded moment after a Christmas party. She was forty when I was born so she might have thought she was past it. But she wanted a daughter. The problem was, she didn’t want the sort of daughter I was. She wanted a daughter like Janet.

My mother’s daughter should have looked at knitting patterns with her and liked pretty clothes. Instead she had one who acquired rude words like cats acquire fleas and who wanted to build streams at the bottom of the garden.

It was a pity we had so little in common. She needed me, and I needed her, but the needs weren’t compatible. The older I got, the more obvious this became to us both. And that’s how I came to meet Janet.

I suspect my father wanted me out of the house because I was an unwelcome distraction. My mother wanted me to learn how to be a lady so we could talk together about dressmaking and menus, so that I would attract and marry a nice young man, so that I would present her with a second family of perfect grandchildren.

My mother cried when she said goodbye to me at the station. I can still see the tears glittering like snail trails through the powder on her cheeks and clogging the dry ravines of her wrinkles. She loved me, you see, and I loved her. But we never found out how to be comfortable with one another.

So off I went to boarding school. It was wartime, remember, and I’d never been away from my parents before, except for three months at the beginning of the war when everyone thought the Germans would bomb our cities to smithereens.

This was different. The train hissed and clanked through a darkened world for what seemed like weeks. I was nominally in the charge of an older girl, one of the monitors at Hillgard House, whose grandmother lived a few miles north of Bradford. She spent the entire journey flirting with a succession of soldiers. The first time she accepted one of their cigarettes, she bent down to me and said, ‘If you tell a soul about this, I’ll make you wish you’d never been born.’

It was January, and the cold and the darkness made everything worse. We changed trains four times. Each train seemed smaller and more crowded than its predecessor. At last the monitor went to the lavatory, and when she came back she’d washed the make-up off her face. She was a pink, shiny-faced schoolgirl now. We left the train at the next stop, a country station shrouded in the blackout and full of harsh sounds I did not understand. It was as if I’d stepped out of the steamy, smoky carriage into the darkness of a world that hadn’t been born.

Someone, a man, said, ‘There’s three more of you in the waiting room. Enough for a taxi now.’

The monitor seized her suitcase in one hand and me with the other and dragged me into the waiting room. That was where I first saw Janet Treevor. Sandwiched between two larger girls, she was crying quietly into a lace-edged handkerchief. As we came in, she looked up and for an instant our eyes met. She was the most beautiful person I’d ever seen.

‘Is that a new bug too?’ the monitor demanded.

One of the other girls nodded. ‘Hasn’t turned off the waterworks since we left London,’ she said. ‘But apart from the blubbing, she seems quite harmless.’

The monitor pushed me towards the bench. ‘Go on, Wendy,’ she said. ‘You might as well sit by her.’ She watched me as I walked across the room, dragging my suitcase after me. ‘At least this one’s not a bloody blubber.’

I have always loathed my name. ‘Wendy’ sums up everything my mother wanted and everything I’m not. My mother loved Peter Pan. When I was eight, it was that year’s Christmas pantomime. I sat hugely embarrassed through the performance while my mother wept happy tears beside me, the salty water falling into the box of chocolates open on her lap. They say that James Barrie invented the name for the daughter of a friend. First he called her ‘Friendy’. Then with gruesome inevitability this became ‘Friendy-Wendy’. Finally it mutated into ‘Wendy’, and the dreadful old man left it as part of his legacy to posterity in general and me in particular. The only character I liked in his beastly story was Captain Hook.

‘Wendy,’ Janet whispered as we huddled together in the back of the taxi on the way to school, squashed into a corner by a girl mountain smelling of sweat and peppermints. ‘Such a pretty name.’

‘What’s yours?’

‘Janet. Janet Treevor.’

‘I like Janet,’ I said, not wanting to be outdone in politeness.

‘I hate it. It’s so plain.’

‘Shame we can’t swap.’

I felt her breath on my cheek, felt her body shaking. I couldn’t hear anything, because of the noise the other girls were making and the sound of the engine. But I knew what Janet was doing. She was giggling.

So that’s how it started, Janet and me. It was January, the Lent Term, and we were the only new children in our year. All the other new children had come in September and had already made friends. It was natural that Janet and I should have been thrown together. But I don’t know why we became friends. Janet was no more like me than my mother was. But in her case – our case – the differences brought us together rather than drove us apart.

Hillgard House was a late-eighteenth-century house in the depths of the Herefordshire countryside. The nearest village was two miles away. The teaching was appalling, the food was often barely edible. When it rained heavily they put half a dozen buckets to catch the drips in the dormitories on the top floor where the servants’ bedrooms had been, and you would go to sleep hearing the gentle plop-plip-plop as the water fell.

The headmistress was called Miss Esk, and she and her brother, the Captain, lived in the south wing of the house. There were carpets there, and fires, and sometimes when the windows were open you could hear the sound of music. The Esks had their own housekeeper who kept herself apart from and superior to the school’s domestic staff. The Captain was rarely seen. We understood that he had suffered from a mysterious wound in the Great War and had never fully recovered. The senior girls used to speculate about the nature of this wound. When I was older, I gained considerable respect by suggesting he had been castrated.

We were always hungry at Hillgard House. It was wartime, as Miss Esk reminded us so often. This meant that we could not expect the luxuries of peace, though we could not help but notice that Miss Esk seemed to have most of them. I think now that the Esks made a fortune during the war: The school was considered to be in a relatively safe area, remote from the risks of both bombing raids and a possible invasion. Many of the girls’ fathers were in the services. Few parents had the time and inclination to check the pastoral and educational standards of the school. They wanted their daughters to be safe, and so in a sense we were.

Janet and I never liked the place but we grew used to it. As far as I was concerned, it had three points in its favour. No one could have a more loyal friend than Janet. Because of the war, and because of the Esks’ incompetence, we were left alone a great deal of the time. And finally there was the library.

It was a tall, thin room which overlooked a lank shrubbery at the northern end of the house. Shelves ran round all the walls. There was a marble fireplace, its grate concealed beneath a deep mound of soot. The shelves were only half full, but you never quite knew what you would find there. In that respect it was like the Cathedral Library in Rosington.

During the five years that we were there, Janet must have read, or at least looked at, every volume there. She read Ivanhoe and The Origin of Species. She picked her way through the collected works of Pope and bound copies of Punch. I had my education at second hand, through Janet.

In our final year, she found a copy of Justine by the Marquis de Sade – in French, bound in calf leather, the pages spotted with damp like an old man’s hand – concealed in a large brown envelope behind the collected sermons of Bishop Berkeley. Janet read French easily – it was the sort of accomplishment you seemed to acquire almost by osmosis in her family – and we spent a week in the summer term picking our way through the book, which was boring but sometimes made us laugh.

In our first few terms, people used to laugh at us. Janet was small and delicate like one of those china figures in the glass-fronted cabinet in Miss Esk’s sitting room. I was always clumsy. In those days I wore glasses, and my feet and hands seemed too large for me. Janet could wear the same blouse for days and it would seem white and crisp from beginning to end, from the moment she took it from her drawer to the moment she put it in the laundry basket. As for me, every time I picked up a cup of tea I seemed to spill half of it over me.

My mother thought Hillgard House would make me a lady. My father thought it would get me out of the way for most of the year. He was right and she was wrong. We didn’t learn to be young ladies at Hillgard House – we learnt to be little savages in a jungle presided over by the Esks, remote predators.

3 (#ulink_f7c359f7-c997-58d7-8c5c-ccc06a0ee250)

I had never known a family like Janet’s. Perhaps they didn’t breed people like the Treevors in Bradford.

For a long time our friendship was something that belonged to school alone. Our lives at home were something separate. I know that I was ashamed of mine. I imagined Janet’s family to be lordly, beautiful, refined. I knew they would be startlingly intelligent, just as Janet was. Her father was serving in the army, but before the war he had lectured about literature and written for newspapers. Janet’s mother had a high-powered job in a government department. I never found out exactly what she did but it must have been something to do with translating – she was fluent in French, German and Russian and had a working knowledge of several other languages.

In the summer of 1944 the Treevors rented a cottage near Stratford for a fortnight. Janet asked if I would like to join them. My mother was very excited because I was mixing with ‘nice’ people.

I was almost ill with apprehension. In fact I needn’t have worried. Mr and Mrs Treevor spent most of the holiday working in a bedroom which they appropriated as a study, or visiting friends in the area. John Treevor was a thin man with a large nose and a bulging forehead. At the time I assumed the bulge was needed to contain the extra brain cells. Occasionally he patted Janet on the head and once he asked me if I was enjoying myself but did not wait to hear my answer.

I remember Mrs Treevor better because she explained the facts of life to us. Janet and I had watched a litter of kittens being born at the farm next door. Janet asked her mother whether humans ever had four at a time. This led to a concise lecture on sex, pregnancy and childbirth. Mrs Treevor talked to us as if we were students and the subject were mathematics. I dared not look at her face while she was talking, and I felt myself blushing.

Later, in the darkness of our shared bedroom, Janet said, ‘Can you imagine how they …?’

‘No. I can’t imagine mine, either.’

‘It’s horrible.’

‘Do you think they did it with the light on?’

‘They’d need to see what they were doing, wouldn’t they?’

‘Yes, but just think what they’d have looked like.’

A moment afterwards Mrs Treevor banged on the partition wall to stop us laughing so loudly.

After Christmas that year, Janet came to stay with me at Harewood Drive for a whole week. She and my mother liked each other on sight. She thought my father was sad and kind. She even liked my dead brothers. She would stare at the photographs of Howard and Peter, one by one, lingering especially at the ones of them looking heroic in their uniforms.

‘They’re so handsome,’ she said, ‘so beautiful.’

‘And so dead,’ I pointed out.

In those days, the possibility of death was on everyone’s minds. At school, fathers and brothers died. Their sisters and daughters were sent to see matron and given cups of cocoa and scrambled eggs on toast. The deaths of Howard and Peter, even though they had happened before my arrival at Hillgard House, gave me something of a cachet because they had been twins and had died so close together.

To tell the truth, I was jealous when Janet admired my doomed brothers, but I was never jealous of the friendship between Janet and my mother. It was not something that excluded me. In a sense it got me off the hook. When Janet was staying with us, I didn’t have to feel guilty.

During that first visit, my mother made Janet a dress, using precious pre-war material she’d been hoarding since 1939. I remember the three of us in the little sewing room on the first floor. I was sitting on the floor reading a book. Every now and then I glanced up at them. I can still see my mother with pins in her mouth kneeling by Janet, and Janet stretching her arms above her head like a ballet dancer and revolving slowly. Their faces were rapt and solemn as though they were in church.

Janet and I shared dreams. In winter we sometimes slept together, huddled close to conserve every scrap of warmth. We pooled information about proscribed subjects, such as periods and male genitalia. We practised being in love. We took it in turns at being the man. We waltzed across the floor of the library, humming the Blue Danube. We exchanged lingering kisses with lips damped shut, mimicking what we had observed in the cinema. We made up conversations.

‘Has anyone ever told you what beautiful eyes you have?’

‘You’re very kind – but really you shouldn’t say such things.’

‘I’ve never felt like this with anyone else.’

‘Nor have I. Isn’t the moon lovely tonight?’

‘Not as lovely as you.’

And so on. Nowadays people would suggest there was a lesbian component to our relationship. But there wasn’t. We were playing at being grown up.

Somewhere in the background of our lives, the war dragged on and finally ended. I don’t remember being frightened, only bored by it. I suppose peace came as a relief. In memory, though, everything at Hillgard House went on much as before. The school was its own dreary little world. Rationing continued, and if anything was worse than it had been during the war. One winter the snow and ice were so bad the school was cut off for days.

Our last term was the summer of 1948. We exchanged presents – a ring I had found in a dusty box on top of my mother’s wardrobe, and a brooch Janet’s godmother had given her as a christening present. We swore we would always be friends. A few days later, term ended. Everything changed.

Janet went to a crammer in London because the Treevors had finally woken up to the fact that Hillgard House was not an ideal academic preparation for university. I went home to Harewood Drive, helped my mother about the house and worked a few hours a week in my father’s shop. There are times in my life when I have been more unhappy and more afraid than I was then, but I’ve never tasted such dreariness.

The only part I enjoyed was helping in the shop. At least I was doing something useful and met other people. Sometimes I dealt with customers but usually my father kept me in the back, working on the accounts or tidying the stock. I learned how to smoke in the yard behind the shop.

I got drunk for the first time at a tennis club dance. On the same evening a boy named Angus tried to seduce me in the groundsman’s shed. It was the sort of seduction that’s the next best thing to rape. I punched him and made his nose bleed. He dropped his hip flask, which had lured me into the shed with him. I ran back to the lights and the music. I saw him a little later. His upper lip was swollen and there was blood on his white shirtfront.

‘Went out to the gents,’ I heard him telling the club secretary. ‘Managed to walk into the door.’

The club secretary laughed and glanced in my direction. I wondered if I was meant to hear, I wondered if the secretary knew, if all this had been planned.

It was a way of life that seemed to have no end. Janet wrote to me regularly and we saw each other once or twice a year. But the old intimacy was gone. She was at university now and had other friends and other interests.

‘Why don’t you go to university?’ she asked as we were having tea at a café in the High on one of my visits to Oxford.

I shrugged and lit a cigarette. ‘I don’t want to. Anyway, my father wouldn’t let me. He thinks it’s unnatural for women to have an education.’

‘Surely he’d let you do something?’

‘Such as?’

‘Well, what do you want to do?’

I watched myself blowing smoke out of my nostrils in the mirror behind Janet’s head and hoped I looked sophisticated. I said, ‘I don’t know what I want.’

That was the real trouble. Boredom saps the will. It makes you feel you no longer have the power to choose. All I could see was the present stretching indefinitely into the future.

But two months later everything changed. My father died. And three weeks after that, on the 19th July 1952, I met Henry Appleyard.

4 (#ulink_665e650a-1f00-5435-b227-e4662e2d0ce8)

Memory bathes the past in a glow of inevitability. It’s tempting to assume that the past could only have happened in the way it did, that this event could only have been followed by that event and in the order they happened. If that were true, of course, nothing would be our fault.

But of course it isn’t true. I didn’t have to marry Henry. I didn’t have to leave him. And I didn’t have to go and stay with Janet at the Dark Hostelry.

During her last year at Oxford, Janet decided that after she had taken her degree she would go to London and try to find work as a translator. Her mother’s contacts might be able to help her. She told me about it over another cup of tea, this time in her cell-like room at St Hilda’s.

‘Is it what you want to do?’

‘It’s all I can do.’

‘Couldn’t you stay here and do research?’

‘I’ll be lucky if I scrape a third. I’m not academic, Wendy. I feel I don’t really belong here. As if I got in by false pretences.’

I shrugged, envious of what she had been offered and refused. ‘I suppose there are lots of lovely young men in London as well as Oxford.’

‘Yes. I suppose so.’

Men liked Janet because she was beautiful. She didn’t say much to them either so they could talk to their hearts’ content and show off to her. But she went out of her way to avoid them. Janet wanted Sir Galahad, not a spotty undergraduate from Christchurch with an MG. In the end, she compromised as we all do. She didn’t get Sir Galahad and she didn’t get the spotty undergraduate with the MG. Instead she got the Reverend David Byfield.

Early in 1952 he came over to Oxford for a couple of days to do some work in the Bodleian. He was writing a book reinterpreting the work of St Thomas Aquinas in terms of modern theology. That’s where he and Janet saw each other, in the library. It was, Janet said, love at first sight. ‘He looked at me and I simply knew.’

Even now, I find it very hard to think objectively about David. The thing you have to remember is that in those days he was very, very good-looking. He turned heads in the street, just as Janet did. Like Henry, he had charm, but unlike Henry he wasn’t aware of it and rarely used it. He had a first-class degree in theology from Cambridge. Afterwards he went to a theological college called Mirfield.

‘Lots of smells and bells,’ Janet told me, ‘and terrifyingly brainy men who don’t like women.’

‘But David’s not like that,’ I said.

‘No,’ she said, and changed the subject.

After Mirfield, David was the curate of a parish near Cambridge for a couple of years. But at the time he met Janet he was lecturing at Rosington Theological College. They didn’t waste time – they were engaged within a month. A few weeks later, David landed the job of vice-principal at the Theological College. They were delighted, Janet wrote, and the prospects were good. The principal was old and would leave a good deal of responsibility to David. David had also been asked to be a minor canon of the Cathedral, which would help financially. The bishop, who was chairman of the Theological College’s trustees, had taken quite a shine to him. Best of all, Janet said, was the house that came with the job. It was in the Cathedral Close, and it was called the Dark Hostelry. Parts of it were medieval. Such a romantic name, she said, like something out of Ivanhoe. It was rather large for them, but they planned to take a lodger.

The wedding was in the chapel of Jerusalem, David’s old college. Janet and David made a lovely couple, something from a fairy tale. If I was in a fairy tale, I told myself, I’d be the Ugly Duckling. What made everything worse was my father’s death – not so much because I’d loved him but because there was now no longer any possibility of his loving me.

Then I saw Henry standing on the other side of the chapel. In those days he was thickset rather than plump. He was wearing a morning suit that was too small for him. We were singing a hymn and he glanced at me. He had wiry hair in need of a cut and straight, strongly marked eyebrows that went up at a sharp angle from the bridge of his nose. He grinned at me and I looked away.

I’ve still got a photograph of Janet’s wedding. It was taken in the front court of Jerusalem. In the centre, with the Wren chapel behind them, are David and Janet looking as if they’ve strayed from the closing scene of a romantic film. David looks like a young Laurence Olivier – all chiselled features and flaring nostrils, a blend of sensitivity and arrogance. He has Janet on one arm and is smiling down at her. Old Granny Byfield hangs grimly on to his other arm.

Henry and I are away to the left, separated from the happy couple by a clump of dour relations, including Mr and Mrs Treevor. Henry is trying half-heartedly to conceal the cigarette in his hand. His belly strains against the buttons of his waistcoat. The hem of my dress is uneven and I am wearing a silly little hat with a half-veil. I remember paying a small fortune for it in the belief that it would make me look sophisticated. That was before I learned that sophistication wasn’t for sale in Bradford.

John Treevor looks very odd. It must have been a trick of the light – perhaps he was standing in a shaft of sunshine. Anyway, in the photograph his face is bleached white, a tall narrow mask with two black holes for eyes and a black slit for the mouth. It’s as if they had taken a dummy from a shop window and draped it in a morning coat and striped trousers.

A moment later, just after the last photograph had been taken, Henry spoke to me for the first time. ‘I like the hat.’

‘Thanks,’ I said, once I’d glanced over my shoulder to make sure he was talking to me and not someone else.

‘I’m Henry Appleyard, by the way.’ He held out his hand. ‘A friend of David’s from Rosington.’

‘How do you do. I’m Wendy Fleetwood. Janet and I were at school together.’

‘I know. She asked me to keep an eye out for you.’ He gave me a swift but unmistakable wink. ‘But I’d have noticed you anywhere.’

I didn’t know what to say to this, so I said nothing.

‘Come on.’ He took my elbow and guided me towards a doorway. ‘There’s no time to lose.’

‘Why?’

The photographer was packing up his tripod. The wedding party was beginning to disintegrate.

‘Because I happen to know there’s only four bottles of champagne. First come first served.’

The reception was austere and dull. For most of the time I stood by the wall and pretended I didn’t mind not having anyone to talk to. Instead, I nibbled a sandwich and looked at the paintings. After Janet and David left for their honeymoon, Henry appeared at my side again, rather to my relief.

‘What you need,’ he said, ‘is a dry martini.’

‘Do I?’

‘Yes. Nothing like it.’

I later learned that Henry was something of an expert on dry martinis – how to make them, how to drink them, how to recover as soon as possible from the aftereffects the following morning.

‘Are you sure no one will mind?’

‘Why should they? Anyway, Janet asked me to look after you. Let’s go down to the University Arms.’

As we were leaving the college I said, ‘Are you at the Theological College too?’

He burst out laughing. ‘God, no. I teach at the Choir School in the Close. David’s my landlord.’

‘So you’re the lodger?’

He nodded. ‘And resident jester. I stop David taking himself too seriously.’

For the next two hours, he made me feel protected, as I had made Janet feel protected all those years ago. I wanted to believe I was normal – and also unobtrusively intelligent, witty and beautiful. So Henry hinted that I was all these things. It was wonderful. It was also some compensation for a) Janet getting married, b) managing to do it before I did, and c) to someone as dashing as David (even though he was a clergyman).

While Henry was being nice to me, he found out a great deal. He learned about my family, my father’s death, the shop, and what I did. Meanwhile, I felt the alcohol pushing me up and up as if in a lift. I liked the idea of myself drinking dry martinis in the bar of a smart hotel. I liked catching sight of my reflection in the big mirror on the wall. I looked slimmer than usual, more mysterious, more chic. I liked the fact I wasn’t feeling nervous any more. Above all I liked being with Henry.

He took his time. After two martinis he bought me dinner at the hotel. Then he insisted on taking me back in a taxi to my hotel, a small place Janet had found for me on the Huntingdon Road. On the way the closest he came to intimacy was when we stopped outside the hotel. He touched my hand and asked if he might possibly see me again.

I said yes. Then I tried to stop him paying for the taxi.

‘No need.’ He waved away the change and smiled at me. ‘Janet gave me the money for everything.’

5 (#ulink_e65b0408-3754-5139-b254-e24b9954eb48)

In those days, in the 1950s, people still wrote letters. Janet and I had settled into a rhythm of writing to each other perhaps once a month, and this continued after her marriage. That’s how I learned she was pregnant, and that Henry had been sacked.

Janet and David went to a hotel in the Lake District for their honeymoon. He must have made her pregnant there, or soon after their return to Rosington. It was a tricky pregnancy, with a lot of bleeding in the early months. But she had a good doctor, a young man named Flaxman, who made her rest as much as possible. As soon as things had settled down, Janet wrote, I must come and visit them.

I envied her the pregnancy just as I envied her having David. I wanted a baby very badly. I told myself it was because I wanted to correct all the mistakes my parents had made with me. With hindsight I think I wanted someone to love. I needed someone to look after and most of all someone to give me a reason for living.

Henry was sacked in October. Not exactly sacked, Janet said in her letter. The official story was that he had resigned for family reasons. She was furious with him, and I knew her well enough to suspect that this was because she had become fond of him. Apparently one of Henry’s responsibilities was administering the Choir School ‘bank’ – the money the boys were given as pocket money at the start of every term. He had to dole it out on Friday afternoon. It seemed he had borrowed five pounds from the cash box that housed the bank and put it on a horse. Unfortunately he was ill the following Friday. The headmaster had taken his place and had discovered that money was missing.

At this time I was very busy. My mother and her solicitor had decided to sell the business. I was helping to make an inventory of the stock, and also chasing up creditors. To my surprise I rather enjoyed the work and I looked forward to going to the shop because it got me away from the house.

When there was a phone call for me one morning I thought it was someone who owed us money.

‘Wendy – it’s Henry.’

‘Who?’

‘Henry Appleyard. You remember? At Cambridge.’

‘Yes,’ I said faintly. ‘How are you?’

‘Wonderful, thanks. Now, what about lunch?’

‘What?’

‘Lunch.’

‘But where are you?’

‘Here.’

‘In Bradford?’

‘Why not? Hundreds of thousands of people are in Bradford. Including you, which is why I’m here. You can manage today, can’t you?’

‘I suppose so.’ Usually I went out for a sandwich.

‘I thought the Metropole, perhaps? Is that OK?’

‘Yes, but –’

Yes, but isn’t it rather expensive? And what shall I wear?

‘Good. How about twelve forty-five in the lounge?’

There was just time for me to go home, deal with my mother’s curiosity (‘A friend of Janet’s, Mother, no one you know’), change into clothes more suitable for the Metropole and reach the hotel five minutes early. It was a large, shabby place, built to impress at the end of the century. I had never been inside it before. Only the prospect of Henry gave me the courage to do so now. I sat, marooned by my own embarrassment, among the potted palms and the leather armchairs, trying to avoid meeting the eyes of hotel staff. Time moved painfully onwards. After five minutes I was convinced that everyone was looking at me, and convinced that he would not come. Then suddenly Henry was leaning over me, his lips brushing my cheek and making me blush.

‘I’m so sorry I’m late.’ He wasn’t – I’d been early. ‘Let’s have a drink before we order.’

Henry wasn’t good-looking in a conventional way or in any way at all. At that time he was in his late twenties but he looked older. He was wearing a grey double-breasted suit. I didn’t know much about men’s tailoring but I persuaded myself that it was what my mother used to call a ‘good’ suit. His collar was faintly grubby, but in this city collars grew dirty very quickly.

Once the dry martinis had been ordered he didn’t beat about the bush. ‘I expect you’ve heard my news from Janet?’

‘That you’ve – you’ve left the Choir School?’

‘They gave me the push, Wendy. Without a reference. You heard why?’

I nodded and stared at my hands, not wanting to see the shame in his eyes.

‘The irony was, the damn horse won.’ He threw back his head and laughed. ‘I knew it would. I could have repaid them five times over. Still, I shouldn’t have done it. You live and learn, eh?’

‘But what will you do now?’

‘Well, teaching’s out. No references, you see, the headmaster made that very clear. It’s a shame, actually – I like teaching. The Choir School was a bit stuffy, of course. But I used to teach at a place in Hampshire that was great fun – a prep school called Veedon Hall. It’s owned by a couple called Cuthbertson who actually like little boys.’ For an instant the laughter vanished and wistfulness passed like a shadow over his face. Then he grinned across the table. ‘Still, one must look at this as an opportunity. I think I might go into business.’

‘What sort?’

‘Investments, perhaps. Stockbroking. There’s a lot of openings. But don’t let’s talk about that now. It’s too boring. I want to talk about you.’

So that’s what we did, on and off, for the next four months. Not just about me. Henry wooed my mother as well and persuaded her to talk to him. We both received the flowers and the boxes of chocolates. I don’t know whether my mother had loved my father, but certainly she missed him when he was no longer there. She also missed what he had done around the house and garden. Here was an opportunity for Henry.

He had the knack of giving the impression he was helping without in fact doing very much. ‘Let me,’ he’d say, but in fact you’d end up doing the job yourself or else it wouldn’t get done at all. Not that you minded, because you somehow felt that Henry had taken the burden from your shoulders. I think he genuinely felt he was helping.

Even now it makes me feel slightly queasy to remember the details of our courtship. I wanted romance and Henry gave it to me. Meanwhile he must have discovered – while helping my mother with her papers – that my father’s estate, including the house and the shop, was worth almost fifty thousand pounds. It was left in trust to my mother for her lifetime and would afterwards come to me.

All this makes me sound naive and stupid, and Henry calculating and mercenary. Both are true. But they are not the whole truth or anything like it. I don’t think you can pin down a person with a handful of adjectives.

Why bother with the details? My father’s executor distrusted Henry but he couldn’t stop us marrying. All he could do was prevent Henry from getting his hands on the capital my father left until after my mother’s death when it became mine absolutely.

We were married in a registry office on Wednesday the 4th of May, 1953. Janet and David sent us a coffee set of white bone china but were unable to come in person because Janet was heavily pregnant with Rosie.

At first we lived in Bradford, which was not a success. After my mother died we sold the house and went briefly to London and then to South Africa in pursuit of the good life. We found it for a while. Henry formed a sort of partnership with a persuasive businessman named Grady. But Grady went bankrupt and we returned to England poorer and perhaps wiser. Nevertheless, it would be easy to forget that Henry and I had good times. When he was enjoying life then so did you.

All things considered, the money lasted surprisingly well. Henry worked as a sort of stockbroker, sometimes by himself, sometimes with partners. If it hadn’t been for Grady he might still be doing it. He once told me it was like going to the races with other people’s money. He was in fact rather good at persuading people to give him their money to invest. Occasionally he even made them a decent profit.

‘Swings and roundabouts, I’m afraid,’ I heard him say dozens of times to disappointed clients. ‘What goes up, must come down.’

So why did his clients trust him? Because he made them laugh, I think, and because he so evidently believed he was going to make their fortunes.

So why did I stay with him for so long?

It was partly because I came to like many of the things he did. Still do, actually. You soon get a taste for big hotels, fast cars and parties. I liked the touch of fur against my skin and the way diamonds sparkled by candlelight. I liked dancing and flirting and taking one or two risks. I occasionally helped Henry attract potential clients, and even that could be fun. ‘Let’s have some old widow,’ he’d say when things were going well for us, and suddenly there would be another bottle of Veuve Clicquot and another toast to us, to the future.

When Henry met me I was a shy, gawky girl. He rescued me from Harewood Drive and gave me confidence in myself. I think I stayed with him partly because I was afraid that without him I would lose all I had gained.

Most of all, though, I stayed because I liked Henry. I suppose I loved him, though I’m not sure what that means. But when things were going well between us, it was the most wonderful thing in the world. Even better than dry martinis and the old widow.

Letters continued to travel between Janet and me. They were proper ones – long and chatty. I didn’t say much about Henry and she didn’t say much about David. A common theme was our plans to meet. Once or twice we managed to snatch a day in London together. But we never went to stay with each other. Somehow there were always reasons why visits had to be delayed.

We were always on the move. Henry never liked settling in one place for any length of time. When he was feeling wealthy we rented flats or stayed in hotels. When money was tight, we went into furnished rooms.

But I was going to spend a few days with Janet and David in Rosington after Easter 1957. Just me, of course – Henry had to go away on what he called a business trip, and in any case he didn’t want to go back to Rosington. Too many people knew why he’d left.

I’d even done my packing. Then the day before I was due to go, a telegram arrived. Mrs Treevor had had a massive heart attack. Once again the visit was postponed. She died three days later. Then there was the funeral, and then the business of settling Mr Treevor into a flat in Cambridge. Janet wrote that her father was finding it hard to cope since her mother’s death.

So we continued to write letters instead. Despite her mother’s death, it seemed to me that Janet had found her fairy tale. She sent me photographs of Rosie, as a baby and then as a little girl. Rosie had her mother’s colouring and her father’s features. It was obvious that she too was perfect, just like David and the Dark Hostelry.

Life’s so bloody unsubtle sometimes. It was all too easy to contrast Janet’s existence with mine. But you carry on, don’t you, even when your life is more like one long hangover than one long party. You think, what else is there to do?

But there was something else. There had to be, as I found out on a beach one sunny day early in October 1957. Henry and I were staying at a hotel in the West Country. We weren’t on holiday – a potential client lived in the neighbourhood, a wealthy widow.

It was a fine afternoon, warm as summer, and I went out after lunch while Henry went off to a meeting. I wandered aimlessly along the beach, a Box Brownie swinging from my hand, trying to walk off an incipient hangover. I rounded the corner of a little rocky headland and there they were, Henry and the widow, lying on a rug.

She was an ugly woman with a moustache and fat legs. I had a very good view of the legs because her dress was up around her thighs and Henry was bouncing around on top of her. His bottom was bare and for a moment I watched the fatty pear-shaped cheeks trembling. The widow was still wearing her shoes, which were navy-blue and high-heeled, surprisingly dainty. I wouldn’t have minded a pair of shoes like that. I remember wondering how she could have walked across the sand in such high heels, and whether she realized that sea water would ruin the leather.

I had never seen Henry from this point of view before. I knew he was vain, and hated the fact that he was growing older. (He secretly touched up his grey hairs with black dye.) The wobbling flesh was wrinkled and flabby. Henry was getting old, and so was I. It was the first moment in my life when I realized that time was running out for me personally as well as for other people and the planet.

Maybe it was the alcohol but I felt removed from the situation, capable of considering it as an abstract problem. I walked towards them, my bare feet soundless on the sand. I crouched a few yards away from the shuddering bodies. Suddenly they realized they were not alone. Simultaneously they turned their heads to look at me, the widow with her legs raised and those pretty shoes in the air.

Still in that state of alcoholic transcendence, I had the sense to raise the Box Brownie and press the shutter.

6 (#ulink_863fd0b1-9393-566b-8127-921204b3100f)

I don’t keep many photographs. I am afraid of nostalgia. You can drown in dead emotions.

Among the photographs I have thrown away is the shot of Henry bouncing on his widow on the beach. I knew at once that it could be valuable, that it meant I could divorce Henry without any trouble. At the time, the remarkable thing was how little the end of the marriage seemed to matter. Perhaps, I thought as I took the film out of the camera, perhaps it was never really a marriage at all, just a mutually convenient arrangement which had now reached a mutually convenient end.

I still have a snap of us by the pool in somebody’s back garden in Durban with Henry sucking in his tummy and me showing what at the time seemed a daring amount of naked flesh. There’s just the two of us in the photograph, but it’s obvious from the body language that Henry and I aren’t a couple in any meaningful sense of the word. Obvious with twenty-twenty hindsight, anyway.

In my letters to Janet I had been honest about everything except Henry. I didn’t conceal the fact that money was sometimes tight, or even that I was drinking too much. But I referred to Henry with wifely affection. ‘Must close now – His Nibs has just come in, and he wants his tea. He sends his love, as do I.’

It was pride. Janet had her Mr Perfect and I wanted mine, or at least the illusion of him. But I think I’d known the marriage was in trouble before the episode with the widow. What I saw on the beach merely confirmed it.

‘I want a divorce,’ I said to Henry when he came back to our room in the hotel. By the smell of him he’d fortified himself in the bar downstairs.

‘Wendy – please. Can’t we –?’

‘No, we can’t.’

‘Darling. Listen to me. I –’

‘I mean it.’

‘All right,’ he said, his opposition crumbling with humiliating speed. ‘As soon as you like.’

I felt sober now and I had a headache. I had found the bottle of black hair dye hidden as usual in one of the pockets of his suitcase. It was empty now. I’d poured the contents over his suits and shirts.

‘No hard feelings,’ I lied. ‘I’ll let you have some money.’

He looked across the room at me and smiled rather sadly. ‘What money?’

‘You know something?’ I said. ‘When I saw you on top of that cow, your bum was wobbling around all over the place. It was like an old man’s. The skin looked as if it needed ironing.’

In the four months after I found Henry doing physical jerks on top of his widow, I wrote to Janet less often than usual. I sent her a lot of postcards. Henry and I were moving around, I said, which was true. Except, of course, we weren’t moving around together. In a sense I spent those four months pretending to myself and everyone else that everything was normal. I didn’t want to leave my rut even if Henry was no longer in there with me.

Eventually the money ran low and I made up my mind I had to do something. I came back to London. It was February now, and the city was grey and dank. I found a solicitor in the phone book. His name was Fielder, and the thing I remember most about him was the ill-fitting toupee whose colour did not quite match his natural hair. He had an office in Praed Street above a hardware shop near the junction with Edgware Road.

I went to see him, explained the situation and gave him the address of Henry’s solicitor. I told him about the photograph but didn’t show it to him, and I mentioned my mother’s money too. He said he’d see what he could do and made an appointment for me the following week.

Time crawled while I waited. I had too much to think about and not enough to do. When the day came round, I went back to Fielder’s office.

‘Well, Mrs Appleyard, things are moving now.’ He slid a sheet of paper across the desk towards me. ‘The wheels are turning. Time for a fresh start, eh?’

I opened the sheet of paper. It was a bill.

‘Just for interim expenses, Mrs Appleyard. No point in letting them mount up.’

‘What does my husband’s solicitor say?’

‘I’m afraid there’s a bit of a problem there.’ Mr Fielder patted his face with a grubby handkerchief. He wore a brown double-breasted pinstripe suit which encased him like a suit of armour and looked thick enough for an Arctic winter. There were drops of moisture on his forehead, and his neck bulged over his tight, hard collar. ‘Yes, a bit of a problem.’

‘Do you mean there isn’t any money?’

‘I did have a reply from Mr Appleyard’s solicitor.’ Fielder scrabbled among the papers on his desk for a few seconds and then gave up the search. ‘The long and the short of it is that Mr Appleyard told him your joint assets no longer seem to exist.’

‘But there must be something left. Can’t we take him to court?’

‘We could, Mrs Appleyard, we could. But we’d have to find him first. Unfortunately Mr Appleyard seems to have left the country. In confidence I may tell you he hasn’t even settled his own solicitor’s bill.’ He shook his head sadly. ‘Not a desirable state of affairs at all. Not at all. Which reminds me …?’

‘Don’t worry.’ I opened my handbag and dropped the bill into it.

‘Of course. And then we’ll carry on in Mr Appleyard’s absence. It should be quite straightforward.’ He glanced at his watch. ‘By the way, your husband left a letter for you care of his solicitor. I have it here.’

‘I don’t want to see it.’

‘Then what would you like me to do with it?’

‘I don’t care. Put it in the wastepaper basket.’ My voice sounded harsh, more Bradford than Hillgard House. ‘I don’t mean to seem rude, Mr Fielder, but I don’t think he has anything to say that I want to hear.’

Walking back to my room along the crowded pavement I wanted to blame Fielder. He had been inefficient, he had been corrupt, but even then I knew neither of these things were true. I just wanted to blame somebody for the mess my life was in. Henry was my preferred candidate but he wasn’t available. So I had to focus my anger on poor Fielder. Before I reached my room, I’d invented at least three cutting curtain lines I might have used, and also constructed a satisfying fantasy which ended with him in the dock at the Old Bailey with myself as the chief prosecution witness. Fantasies reveal the infant that lives within us all. Which is why they’re dangerous because the usual social constraints don’t operate on infants.

When I went into the house, Mrs Hyson, the landlady, opened the kitchen door a crack and peered at me, but said nothing. I ate dry bread and elderly cheese in my room for lunch to save money. I kept on my overcoat to postpone putting a shilling in the gas meter. Since leaving Henry I had lived on the contents of my current account at the bank and my Post Office Savings Account, a total of about two hundred pounds, and by selling a fur coat and one or two pieces of jewellery.

I wasn’t even sure I could afford to divorce Henry. First I needed to find a job but I was not trained to do anything. I was twenty-six years old and completely unemployable. There were relations in Leeds – a couple of aunts I hadn’t seen for years and cousins I’d never met. Even if I could track them down there was no reason why they should help me. That’s when I opened my writing case and began the letter to Janet.

Looking back, I think I must have been very near a nervous breakdown when I wrote that letter. It’s more than forty years ago now, but I can still remember how the panic welled up. The certainties were gone. In the past I’d always known what to do next. I often didn’t want to do it but that was not the point. What had counted was the fact the future was mapped out. I’d also taken for granted there would be a roof over my head, clothes on my back and food on the table. But now I had nothing.

I looked for the letter after Janet’s death and was glad I could not find it. I hope she destroyed it. I cannot remember exactly what I told her, though I would have kept nothing back except perhaps my envy of her. What I do remember is how I felt while I was writing that letter in the chilly little room in Paddington. I felt I was trying to swim in a black sea. The waves were so rough and my waterlogged clothes weighed me down. I was drowning.

Early in the evening I went out to post the letter. On the way back I passed a pub. A few yards down the pavement I stopped, turned back and went into the saloon bar. It was a high-ceilinged room with mirrors on the walls and chairs upholstered in faded purple velvet. Apart from two old ladies drinking port, it was almost empty, which gave me courage. I marched up to the counter and ordered a large gin and bitter lemon, not caring what they thought of me.

‘Waiting for someone then?’ the barmaid asked.

‘No.’ I watched the gin sliding into the glass and moistened my lips. ‘You’re not very busy tonight.’

I doubt if the place was ever busy. It smelled of failure. That suited me. I sat in the corner and drank first one drink, then another and then a third. A man tried to pick me up and I almost said yes, just for the hell of it.

There were women around here who made a living from men. You saw them hanging round the station and on street corners, huddled in doorways or bending down to a car window to talk to the man inside. Could I do that? Would you ever get used to having strange men pawing at you? How much would you charge them? And what happened when you grew old and they stopped wanting you?

To escape the questions I couldn’t answer, I had another drink, and then another. In the end I lost count. I knew I was drinking tomorrow’s lunch and tomorrow’s supper, and then the day after’s meals as well, and in a way that added to the despairing pleasure the process gave me. The barmaid and her mother persuaded me to leave when I ran out of money and started crying.

I dragged myself back to the bed and breakfast. On my way in I met Mrs Hyson. She knew what I’d been doing, I could see it in her face. She could hardly have avoided knowing. I must have smelt like a distillery and it was a miracle I got up those stairs without falling over. It was too much trouble to take off my clothes. The room was swaying so I lay down on top of the eiderdown. Slowly the walls began to revolve round the bed. The whole world had tugged itself free from its moorings. The last thing I remember thinking was that Mrs Hyson would probably want me out of her house by tomorrow.

7 (#ulink_15b827e1-aaef-54d3-a4bb-d605d27f1dde)

I began the slow hard climb towards consciousness around dawn. For hours I lay there and tried to cling to sleep. My mouth was dry and my head felt as though there were a couple of skewers running through it. I was aware of movement in the house around me. The doorbell rang and the skewers twisted inside my skull. A few moments later there was a knock on the door.

Trying not to groan, I stood up slowly and padded across the floor in my stockinged feet. I opened the door a crack. Her nose wrinkling, Mrs Hyson stared up at me. I had slept in my clothes. I hadn’t removed my make-up either.

‘There’s a gentleman to see you, Mrs Appleyard.’

‘A gentleman?’

Mrs Hyson frowned and walked away. My stomach lurched at the thought it might be Henry. But I had nothing left for him to take. Maybe it was that solicitor, anxious about his cheque.

A few minutes later I went downstairs as if down to my execution and into Mrs Hyson’s front room. I found David Byfield examining a menacing photograph of the dear departed Mr Hyson. He turned towards me, holding out his hand and offering me a small, cool smile. He didn’t seem to have changed since his wedding day. Unlike me.

‘I hope you don’t mind my calling. I was up in town anyway, and Janet phoned me this morning with the news.’

‘She’s had my letter, then?’

He nodded. ‘We’re so sorry.’

How I hated that we. ‘No need. It had been coming to an end for a long time.’ I glared at him and winced at the stabs of pain behind my eyes. ‘You should be glad, not sad.’

‘It’s always sad when a marriage breaks down.’

‘Yes, well.’ I realized I must sound ungracious, and added brightly, ‘And how are you? How are Janet and Rosie?’

‘Very well, thank you. Janet’s hoping-we’re hoping that you’ll come and stay with us.’

‘I can manage quite well by myself, thank you.’

‘I’m sure you can.’

The Olivier nostrils flared a little further than usual. ‘It would give us all a great deal of pleasure.’

‘All right.’

‘Good.’

He smiled at me now, showing me his approval. That’s what really irritated me, the way I felt myself warming in the glow of his attention. Sex appeal can be such a depressingly impersonal thing.

David swiftly arranged the next stage of my life, barely bothering to consult me. His charity was as impersonal as his sex appeal. He was helping me because he felt he ought to or because Janet had asked him to. He was earning good marks in heaven or with Janet, possibly both.

A few hours later I was in a second-class smoking compartment and the train was pulling out of the echoing cavern of Liverpool Street Station. I still had the hangover but time, tea and aspirins had dulled the skewers of pain and made them irritating but bearable, like a certain sort of old friend. My suitcase was above my head and the two trunks would be following by road. I had bathed and changed. I’d even managed to eat and keep down a meal that wasn’t quite breakfast and wasn’t quite lunch. David wasn’t with me – his conference ended at lunchtime tomorrow.

The train lumbered north between soot-streaked houses beneath a smoky sky.

‘Let’s face it,’ I told myself as the train began to gather speed and I fumbled for my cigarettes, ‘he doesn’t give a damn about me. And why the hell should he?’

It occurred to me that I wasn’t quite sure which he I meant.

After Cambridge the countryside became flat. The train puffed on a straight line with black fields on either side. It was already getting dark. The horizon was a border zone, neither earth nor sky. I was alone in my compartment. I felt safe and warm and a little sleepy. If the journey went on for ever, that would have been quite all right by me.

The train began to slow. I looked out of the window and saw in the distance the spire of Rosington Cathedral. The closer we got to it, the more it looked like a stone animal preparing to spring. I went to the lavatory, washed a smut off my cheek and powdered my nose. David had telephoned Janet and asked her to meet me.

By the time I got back to the compartment, the platform was sliding along the window. I pulled down my suitcase and left the train. The first thing I noticed was the wind that cut at my throat like a razor blade. The wind in Rosington isn’t like other winds, Janet had written in one of her letters, it comes all the way from Siberia and over the North Sea, it’s not like an English wind at all.

Janet wasn’t on the platform. She wasn’t at the barrier. She wasn’t outside, either.

I dragged my suitcase through the ticket hall and into the forecourt beyond. The station was at the bottom of the hill. At the top was the stone mountain. The wind brought tears to my eyes. A tall clergyman was climbing into a tall, old-fashioned car. He glanced at me with flat, incurious eyes.

Before I went to Rosington I didn’t know any priests. They were there to be laughed at on stage and screen, avoided like the plague at parties, and endured at weddings and funerals of the more traditional sort. After Rosington, all that changed. Priests became people. I could believe in them.

I wasn’t any nearer believing in God, mind you. A girl has her pride. Sometimes, though, I wish I could think that it was all for the best in the long run. That God had a plan we could follow or not follow, as we chose. That when bad things happened they were due to evil, and that even evil had a place in God’s inscrutable but essentially benevolent plan.

It’s nonsense. Why should we matter to anyone, least of all to an omnipotent god whose existence is entirely hypothetical? I still think that Henry got it right. It was one evening in Durban, and we were having a philosophical discussion over our second or third nightcaps.

‘Let’s face it, old girl,’ he said, ‘it’s as if we’re adrift on the ocean in a boat without oars. Not much we can do except drink the rum ration.’

At Rosington station, I watched the clergyman’s car driving up the hill into the darkening February afternoon. I waited a few more minutes for Janet. I went back into the station and phoned the house. Nobody answered.

So there was nothing for it but one of the station taxis. I told the driver to take me to the Dark Hostelry in the Close. In one of her letters, Janet said someone told her that in the Middle Ages, when Rosington was a monastery, the Dark Hostelry was where visiting Benedictine monks would stay. The ‘Dark’ came from the black habits of the order.

The taxi took me up the hill and through the great gateway, the Porta, and into the Close. I saw small boys in caps and shorts and grey mackintoshes. Perhaps they were at the Choir School. None of the boys would remember Henry. Six years is a long time in the life of a school.

We followed the road round the east end of the Cathedral and stopped outside a small gate in a high wall. I didn’t ask the driver to carry in my suitcase – it would have meant a larger tip. I pushed open the gate in the wall, and that’s when I saw Rosie playing hopscotch.

‘And what’s your name?’ I asked.

‘I’m nobody.’

Rosie wasn’t wearing a coat. There she was in February playing outside and wearing sandals and a dress, not even a cardigan. The light was beginning to go. Some children don’t feel the cold.

‘Nobody?’ I said. ‘I’m sure that’s not right. I bet you’re really somebody. Somebody in disguise.’

‘I’m nobody. That’s my name.’

‘Nobody’s called nobody.’

‘I am.’

‘Why?’

‘Because nobody’s perfect.’

And so she was. Perfect. I thought, Henry, you bastard, we could have had this.

I called after Rosie as she skipped down the path towards the house. ‘Rosie! I’m Auntie Wendy.’

I felt a fool saying that. Auntie Wendy sounded like a character in a children’s story, the sort my mother would have liked.

‘Can you tell Mummy I’m here?’

Rosie opened the door and skipped into the house. I picked up my case and followed. I was relieved because Janet must have come back. She wouldn’t have left a child that age alone.

The house was part of a terrace. I had a confused impression of buttresses, the irregular line of high-pitched roofs against a grey velvet skyline, and small deeply recessed windows. At the door I put down my case and looked for the bell. There were panes of glass set in the upper panels and I could see the hall stretching into the depths of the building. Rosie had vanished. Irregularities in the glass gave the interior a green tinge and made it ripple like Rosie’s hair.

A brass bell pull was recessed into the jamb of the door. I tugged it and hoped that a bell was jangling at the far end of the invisible wire. There was no way of knowing. You just had to have faith, not a state of mind that came easily to me at any time. I tried again, wondering if I should have used another door. The skin prickled on the back of my neck at the possibility of embarrassment. I waited a little longer. Someone must be there with the child. I opened the door and a smell of damp rose to meet me. The level of the floor was a foot below the garden.

‘Hello?’ I called. ‘Hello? Anyone home?’

My voice had an unfamiliar echo to it, as though I had spoken in a church. I stepped down into the hall. It felt colder inside than out. A clock ticked. I heard light footsteps running above my head. There was a click as a door opened, then another silence, somehow different in quality from the one before.

Then the screaming began.

There’s something about a child’s screams that makes the heart turn over. I dropped the suitcase. Some part of my mind registered the fact that the lock had burst open in the impact of the fall, that my hastily packed belongings, the debris of my life with Henry, were spilling over the floor of the hall. I ran up a flight of shallow stairs and found myself on a long landing.

The door at the end was open. I saw Rosie’s back, framed in the doorway. She wasn’t screaming any more. She was standing completely still. Her arms hung stiffly by her sides as though they were no longer jointed at the elbows.

‘Rosie! Rosie!’

I walked quickly down the landing and seized her by the shoulders. I spun her round and hugged her face into my belly. Her body was hard and unyielding. She felt like a doll, not a child. There was another scream. This one was mine.

The room was furnished as a bedroom. It smelled of Brylcreem and peppermints. There were two mullioned windows. One of them must have been open a crack because I heard the sound of traffic passing and people talking in the street below. At times like that, the mind soaks up memories like a sponge. Often you don’t know what’s there until afterwards, when you give the sponge a squeeze and you see what trickles out.

At the time I was aware only of the man on the floor. He lay on his back between the bed and the doorway. He wore charcoal-grey flannel trousers, brown brogues and an olive-green, knitted waistcoat over a white shirt with a soft collar. A tweed jacket and a striped tie were draped over a chair beside the bed. His left hand was resting on his belly. His right hand was lying palm upwards on the floor, the fingers loosely curled round the dark bone handle of a carving knife. There was blood on the blade, blood on his neck and blood on his shirt and waistcoat. His horn-rimmed glasses had fallen off. Blue eyes stared up at the ceiling. His hair was greyer and scantier than when I’d seen it last, and his face was thinner, but I recognized him right away. It was Janet’s father.

‘Come away, Rosie,’ I muttered, ‘come away. Grandpa’s sleeping. We’ll go downstairs and wait for Mummy.’

As if my words were a signal, Mr Treevor blinked. His eyes focused on the two of us in the doorway.

‘Fooled you,’ he said, and then he began to laugh.

PART II (#ulink_89c2a440-f622-5275-bc30-27e835b31479)

8 (#ulink_4199622b-8327-5a09-8716-e34781da130e)

‘I’m so sorry.’ Janet was brushing Rosie’s hair. The bristles caught in a tangle, and Janet began carefully to tease it out. ‘He just arrived.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said.

‘Oh, but it does.’ Her eyes met mine, then returned to the shining hair. ‘The doorbell rang at half past three and there he was. He’d come all the way from Cambridge in a taxi.’

Rosie was sitting on a stool on the hearthrug, her back straight, not leaning against her mother’s knees. In her place I would have been fidgeting, or playing with a toy, or looking at a book. But Rosie seemed hypnotized by the gentle scratching of the brush.

‘It didn’t occur to him to telephone. He just came as he was. No luggage, no overcoat. He even forgot his wallet. I had to use the housekeeping.’ Janet smiled but I knew her too well to be fooled. ‘He was still in his slippers.’

We were in a narrow, panelled sitting room. The three of us were huddled round the hearthrug in front of the fire. Rosie was in her nightclothes. Janet had given me a gin and orange, with rather too much orange for my taste, and I was nursing it between my hands, trying to make it last.

‘He’d forgotten his medicine too. Actually they’re laxatives. He gets terribly concerned about them. That’s why I had to pop out to the chemist’s before it closed. And then the dean’s wife swooped and I couldn’t get away.’ The brush faltered. Janet rested her hands on Rosie’s shoulders. ‘Poor Grandpa will forget his own name next, won’t he, poppet? Now, say good night to Auntie Wendy and we’ll put you into bed.’

When they went upstairs, I wandered over to the drinks tray and freshened my glass with a little gin. All three of us had tiptoed round what Mr Treevor had done upstairs. I wondered what Janet was saying to Rosie about it now. If anything. How do you explain to a child that Grandpa found a bottle of tomato ketchup in the kitchen, took it upstairs to his room and splashed it over him to make it look as if he’d stabbed himself to death? What on earth had he been thinking about? He had ruined his clothes and the bedroom rug. God knew what effect he had had on Rosie. The only consolation was that all the excitement had tired him out. He was resting on his bed before supper.

Glass in hand, I wandered round the room, picking up ornaments and looking at the books and pictures. I had grown sensitive to poverty in others as you do when your own money runs low. I thought I saw hints of it here, a cushion placed to cover a stain on a chair’s upholstery, a fire too small for the grate, curtains that needed relining. David couldn’t earn much.

There was a wedding photograph in a silver frame on the pier table between the windows, just the two of them in front of Jerusalem Chapel, David’s clerical bands snapping in the breeze. I didn’t have any photographs of my wedding, a hole-in-the-corner affair compared with theirs. My mother had thought we should have a white wedding with all the trimmings but Henry persuaded her to let us have the money instead for the honeymoon.

Janet came downstairs.

‘Supper will have to be very simple, I’m afraid. Would cheese on toast be all right? There’s some apple crumble in the larder.’

‘That’s fine.’ I noticed her shiver. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘I wanted it to be nice for you on your first evening especially. We haven’t seen each other in such ages.’

‘It’s all right. It’s lovely to be here: Will your father be coming down?’

‘He’s dozed off.’ She went over to the fire and began to add coal. ‘I didn’t like to wake him.’

I sat on the sofa. ‘Janet – does he often do things like that?’

‘The tomato ketchup?’

I said nothing.

‘He’s always had a sense of humour,’ she said, and threw a shovelful of coals on the fire.

‘He kept it well concealed when I came to stay with you.’

Janet glanced at me. Tears made her eyes look larger than ever. ‘Yes. Well. People change.’

‘Come on.’ I patted the seat of the sofa. ‘Come and tell me about it.’

‘But supper –’

‘Damn supper.’

‘I wish I could.’ Suddenly she was almost shouting. ‘You’ve no idea how much I hate cooking. In the morning the sight of a fried egg makes my stomach turn over.’

‘Me too. Anyway, I’m going to help with supper. But come and sit down first.’

She dabbed her eyes with a dainty little handkerchief. She was one of the few people I’ve ever known who don’t make a spectacle of themselves when they cry. Janet managed everything gracefully, even tears. I brought her another drink. She made a half-hearted attempt to push the glass away.

‘I shouldn’t drink this. I’ve already had one tonight.’

‘It’s medicinal.’ I watched her take a sip. ‘Tell me, how long’s he been like this?’

‘I don’t know. I think it must have started before Mummy died. It’s been very gradual.’

‘Have you thought about putting him in a home?’

‘I couldn’t do that. He’s not old. He’s not even seventy yet. And it’s not as if he’s ill. Just a bit forgetful at times.’

‘Has he seen the doctor?’

‘He doesn’t like doctors. That business with the tomato sauce …’

‘Yes?’

‘I think he was just trying to be friendly. Just trying to play a game with Rosie, to make her laugh. But he didn’t realize the effect he would have.’

She hesitated and added carefully, ‘He was never very good with children.’

‘And what does David say?’

‘I haven’t liked to bother him too much. He’s very busy at present. There’s a possibility of a new job …’

‘But surely he must have noticed?’

‘He hasn’t seen Daddy for a while. Anyway, for most of the time he’s all right.’

I felt like an inquisitor. ‘And what did Rosie say?’

‘Nothing really.’ Janet ran her finger round the rim of her glass. ‘I told her that Grandpa was just having a joke, and it was one of those grown-up jokes that children don’t always understand. And she nodded, and that was that.’

It turned into quite a nice evening in the end. Rosie fell asleep, and so did that dreadful old man upstairs. Janet and I ended up making piles of toast over the sitting room fire and getting strawberry jam all over the hearthrug. Janet gave me a chance to talk about Henry but I didn’t want to, not then. So we ignored him altogether (which he would have hated so much) and I was happy. There was I acting the tower of strength while inside I felt like a jelly, just as I had all those years ago at school. Between them, Janet and Mr Treevor made me feel useful again. We choose our own families, especially if our biological ones aren’t very satisfactory.

9 (#ulink_487fe74b-60d3-5845-bbc5-5dacd6e41215)

Even now, when I am as old as John Treevor, I dream about the day I came to Rosington. Not about what happened in the house. About talking to Rosie outside. The odd thing, the disturbing thing, is what Rosie says. Or doesn’t say.

When I see her in the dream I know she’s going to tell her joke, that she’s called Nobody because nobody’s perfect. But the punchline is scrambled. That’s what makes me anxious – the fact I don’t know how the words will come out. Perfect but nobody. Nobody but perfect. A perfect nobody. Perfect no body. No perfect body. Maybe my sleeping mind worries about that because it’s less painful than worrying about what was going on in the house.

But the dream came much later. On my first night in Rosington I slept better than I had for years. I was in a room on the second floor away from the rest of the house. When I woke I knew it was late because of the light filtering through the crack in the curtains. The air in the bedroom was icy. I stayed in the warm nest of the bedclothes for at least twenty minutes more.

Eventually a bursting bladder drove me out of bed. The bathroom was warmer than my room because it had a hot-water tank in it. I took my clothes in there and got dressed. I went downstairs and found Janet’s father sitting in a Windsor chair at the kitchen table reading The Times.

We eyed each other warily. He had not come downstairs again the previous evening; Janet had taken him some soup. He stood up and smiled uncertainly.

‘Hello, Mr Treevor.’

He looked blank.

‘I’m Wendy Appleyard, remember – Janet’s friend from school.’

‘Yes, yes. There’s some tea in the pot, I believe. Shall I –?’ He made a half-hearted attempt to investigate the teapot on my behalf.

‘I think I might make some fresh.’

‘My wife always says that coffee never tastes the same if you let it stand.’ He looked puzzled. ‘Good idea. Yes, yes.’

I was aware of him watching me as I filled the kettle, put it on the stove and lit the gas. He had put on weight since I had seen him last, a great belt of fat. The rest of him still looked relatively slim, including the face with its nose like a beak and the bulging forehead, now even more prominent because the hairline had receded further. His hair was longer than it used to be and unbrushed. He wore a heavy jersey that was too large for his shoulders and too small for his stomach. I wondered if it belonged to David. He did not refer to the incident yesterday and nor did I.