The Mayfair Mystery: 2835 Mayfair

Frank Richardson

David Brawn

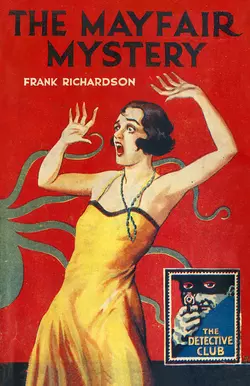

The first in a new series of classic detective stories from the vaults of HarperCollins involves a disappearing corpse, a supernatural theory, and a genuinely shocking finale.“The Detective Story Club”, launched by Collins in 1929, was a clearing house for the best and most ingenious crime stories of the age, chosen by a select committee of experts. Now, almost 90 years later, these books are the classics of the Golden Age, republished at last with the same popular cover designs that appealed to their original readers.“This most entertaining detective story is concerned with an amazing crime. The body of a wealthy man is discovered by his valet. The valet hurried to a friend of the dead man to tell him of the tragedy. They return to find the body gone! The motive of the murder becomes a deeper mystery still, and no clue seems to lead anywhere. Little by little, however, evidence is built up round a theory, and clever detective work triumphs in the end. For ingenuity and dramatic situations “The Mayfair Mystery” is hard to beat.”First published in 1907 as 2835 Mayfair, the book had caught the imagination of the reading public for its thrilling twists, its wit and imagination, and was chosen to be one of the first 12 classic books released by the Club. This new edition comes with a brand new introduction about the history of the Detective Club by HarperCollins’ editor, David Brawn.

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain as 2835 Mayfair by Mitchell Kennerley 1907

Published as The Mayfair Mystery by The Detective Story Club Ltd

for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929

Introduction © David Brawn 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2015

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137083

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780008137090

Version: 2015-07-06

Contents

Cover (#u52089d83-b356-5d27-b7b0-ae6319e454dc)

Title Page (#ubc6e3976-282e-5b6d-89bf-c691d008415d)

Copyright (#u094d4289-47f2-5652-83b1-4095025641c4)

Introduction (#ua3476989-2ba7-5be7-bfeb-2d497b4f22e2)

Chapter I: THE DEAD MAN (#u2c29023f-edda-56f8-b835-2826e33ad2af)

Chapter II: CONCERNING THE CORPSE (#u58e46127-1dc3-58ed-9433-43f96ba20112)

Chapter III: THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE CORPSE (#u4dce3a31-0737-5a8f-99c4-342f3d80bb0d)

Chapter IV: THE ALLEGED ADA (#u8112ac7a-b60a-59df-8acf-dc4202277597)

Chapter V: AT THE GRIDIRON (#u4c70fc86-2423-5be8-88c4-a6bb3733f203)

Chapter VI: THE TROUBLE WITH MINGEY (#uc2e94242-0805-50f7-8b37-252e2a0af459)

Chapter VII: MAINLY ABOUT LOVE (#ud1c667e4-2f6b-5fd9-9f2e-70ab06c8f5ee)

Chapter VIII: 2835 MAYFAIR (#ua5ef0371-ca3f-582f-8314-9084805f6dfb)

Chapter IX: 69 PEMBROKE STREET (#u9306e864-f97c-52e7-876d-2d5ff5f54813)

Chapter X: THE MINGEY MYSTERY (#u651b5403-6191-5368-88b1-0d1ef634c9f1)

Chapter XI: ‘PURE BROMPTON ROAD’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII: AT THE CARLTON (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII: A LITTLE DINNER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV: THE EVIDENCE OF NELLIE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV: INSPECTOR JOHNSON (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI: ‘UNCLE GUSSIE’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII: A PROPOSAL OF MARRIAGE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII: JOHNSON AND BARLOW (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX: THE DETECTIVES (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XX: JOHNSON BECOMES BRIGHTER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI: NEWS OF SARAH (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXII: THE CURE FOR CANCER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIII: THE MYSTERIOUS BEHAVIOUR OF SIR CLIFFORD OAKLEIGH (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIV: UNPOPULARITY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXV: ‘I LOVE YOU’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVI: ‘UNCLE GUSSIE’ IS NONPLUSSED (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVII: AT THE SAVOY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVIII: DISAPPOINTMENT (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIX: REGGIE LOSES HIS JOB (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXX: AN UNFORTUNATE MEETING (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXI: THE DISMISSAL OF MINGEY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXII: THE ASSISTANCE OF SMALLWOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXIII: MORPHIA? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXIV: A POSSIBLE CLUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXV: HARDING MAKES HEADWAY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXVI: THE RETURN OF MIRIAM (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXVII: THE ACCIDENT (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXVIII: ‘SOMETHING IS ON HER MIND’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXIX: AN ASTOUNDING DISCOVERY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XL: MIRIAM’S DEFENCE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XLI: AT THE POLICE-COURT (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XLII: THE SOLUTION (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. was celebrating exactly 100 years of book publishing when in the spring of 1919 Sir Godfrey Collins and his staff announced its first detective novel—The Skeleton Key by Bernard Capes. Capes, a prolific and versatile writer best known for his ghost stories, had delivered his manuscript to Collins shortly before falling prey to the worldwide flu pandemic in the autumn of 1918, and died before his most lucrative book in a 20-year writing career was published.

Sir Godfrey, who had served in the Victorian navy and later entered politics to become a Liberal M.P. and later Secretary of State for Scotland, had become head of publications at the Glasgow-based printing company in 1906 when his uncle, the ambitious and colourful William Collins III, plunged to an untimely death down an empty lift shaft in a freak accident at his Westminster flat. It is not known now whether Sir Godfrey had intended The Skeleton Key to be a one-off book or the start of a new initiative, but its immediate success coincided with a growing post-war interest in modern exciting fiction based on crime and mystery. Within ten years of The Skeleton Key, Collins had built up a rich stable of reliable and popular crime writers, among them Lynn Brock, J. S. Fletcher, Anthony Fielding, Herbert Adams, John Stephen Strange, Hulbert Footner, G. D. H. & M. Cole, J. Jefferson Farjeon, Vernon Loder, John Rhode, Francis D. Grierson, Miles Burton, Philip MacDonald, Freeman Wills Crofts and, in 1926, Agatha Christie.

Nearly all new novels in the early 1920s were hardback, usually costing 7/6 each, and the most popular titles were frequently rejacketed and reprinted in a ‘cheap edition’, still in hardcover but often smaller in size and always on cheaper paper. In fact, the idea of making cheap hardbacks out of popular copyright fiction by living authors (as opposed to nineteenth-century classics, as had been the convention) was one of Godfrey Collins’ earliest initiatives. His revolutionary ‘Books for the Million’ first went on sale in May 1907, but to Collins’ dismay rival publisher Thomas Nelson beat them into the shops with the same idea just three days earlier.

By 1928 Collins had pretty much cornered the market in this area with a rapidly growing number of different series, including Collins Classics, The Literary Press, The Novel Library, The London Book Co. and Westerns (later renamed The Wild West Club), with more than 2,500 cheap fiction titles now appearing in the Collins catalogue. It was probably therefore inevitable that Godfrey Collins would add another imprint to the growing range of sixpenny hardbacks: The Detective Story Club.

Launched in July 1929, the series included the whole panoply of crime writing: classic mystery novels from the previous century; tales of true crime; modern detective stories; and a growing publishing phenomenon, ‘the Book of the Film’, inspired by cinema’s new ‘talkies’. Twelve Detective Story Club books had been published by Christmas 1929, and another 60 or so would follow over the next five years. All had brand new colourful jacket designs with matching spines, finished off with the distinctive stamp of the masked ‘man with the gun’, an evolution of a sinister Zorro-like mask motif which had adorned 1920s Collins crime covers to distinguish them as detective novels.

Perhaps the boldest move was to change many of the book titles to make them sound more obvious: thus Bernard Capes’ The Skeleton Key became The Mystery of the Skeleton Key; Israel Zangwill’s The Big Bow Mystery—the first full-length ‘locked room’ novel—became The Perfect Crime; Maurice Drake’s obscure thriller WO2 was retitled The Mystery of the Mud Flats;and J. S. Le Fanu’s classic The Room in the Dragon Volant became The Flying Dragon. Perhaps the oddest alteration was to J. S. Fletcher’s accomplished short story collection The Ravenwood Mystery, renamed The Canterbury Mystery despite there being no such story in the book.

The Daily Mirror reviewed the new series: ‘Attractively bound in black and gold, with vivid coloured jackets, these books are bound to be immensely popular’, and an advertisement for the Detective Story Club in June 1930 claimed that it was ‘The Club with a Million Members!’ with already 19 books ‘sold by booksellers & newsagents everywhere’. The advert went on to state:

The extraordinary popularity of detective stories shows no signs of diminishing. The late Prime Minister [Stanley Baldwin] has confessed that he enjoys them; eminent men and women of every branch of life find them a mental stimulus. There is room for the Detective Story Club, Limited, founded to issue stories from the best detective writers—from Gaboriau to Edgar Wallace at a uniform price of 6d. Membership of the ‘club’ is completely informal. Any member of the public can buy these books through the ordinary trade channels, and in no other way.

The Detective Story Club was a big success. It spawned its own monthly short story magazine, which also sold for sixpence, and within a year gave Collins the confidence to launch a dedicated imprint for its full-price 7/6 hardbacks. In May 1930 the Crime Club was born, publishing three new mystery books every month, again selected by a body of ‘experts’. For its logo, the masked gunman evolved into a hooded gunman, and fans were invited to register by post for a free quarterly newsletter. The Crime Club ran until 1994 and published more than 2,000 titles, adding many new famous names to Collins’ existing roster, including Anthony Gilbert, Rex Stout, Ngaio Marsh, Elizabeth Ferrars, Joan Fleming, Robert Barnard, Julian Symons, H. R. F. Keating and Reginald Hill.

The Detective Story Club continued alongside the Crime Club until 1934, eventually abandoning the classics, the true crime and the film tie-ins and becoming principally a vehicle for cheap reprints of Collins’ earliest crime novels, such as 1920s titles by Agatha Christie, Freeman Wills Crofts and Philip MacDonald.

Then in 1935 the launch by publisher Allen Lane of his popular Penguin paperbacks sounded the death knell for the cheap hardback. Within a year, Collins launched its own paperback list, ‘White Circle Crime Club’, with stylish green and black covers showing a ghostlike gunman (and a knife-wielding accomplice), whose hood had now become a full-length shroud, and the original Man with the Gun was retired.

The resurrection of the Detective Story Club today is a chance to revisit some the best and most entertaining detective novels of the last century. The editors who picked titles for the Club chose well, although ideas about what constituted a detective story were obviously quite broad. Some books didn’t even feature detectives, and many of the rules and disciplines that characterised the era that has become known as the ‘Golden Age’ had yet to be formalised. These authors were the pioneers of an emerging genre—some broke new ground by inventing new types of story like the locked room mystery, the police procedural or the serial killer, while still drawing on more old-fashioned styles of classical romance, whimsical satire or the supernatural. But these were books with thrills and spills that got under the skin of their readers, and as such offer a candid glimpse today of how people thought and behaved at the time they were written.

The Mayfair Mystery, originally published in 1907 as 2835 Mayfair, is one such example. Author Frank Richardson had become very well known both in the UK and the USA as a satirist, his recurring theme a crusade against the Edwardian fashion for facial hair. He wrote more than a dozen books in just ten years, latterly collections of his widely published stories and parodies, including Bunkum (1907), its imaginatively titled sequel More Bunkum (1909), and perhaps his most famous, Whiskers and Soda (1910). These clearly endeared him to readers and reviewers on both sides of the Atlantic: ‘Whimsical, audacious, unconnected, and discursive, irresistibly amusing’ (Daily Express); ‘A master of extravaganza: No one can take up his books without being infected by the light, careless spirit which pervades them’ (Daily Telegraph); ‘No living writer knows better how to amuse than Mr Frank Richardson’ (New York Herald); ‘One of the wittiest men in London’ (New York Evening News); and so they went on.

Frank Collins Richardson was born in Paddington, Middlesex (as it was then) on 21 August 1870. He went to Marlborough College, where impending unpopularity amongst his peers from a ‘versatile incompetence’ at both games and work was seemingly averted by his ability to invent and tell vivid stories after lights out in the dormitory. After being ‘superannuated’ at Marlborough, he failed to get into Trinity, Oxford, where one Professor declaimed: ‘Richardson, you will always be a fool, but your sense of humour may prevent you from being a damned fool.’ However, he did get into Christ Church, but got out without a degree, and thanks to his father, the (inevitably bewhiskered) Chairman of the North Metropolitan Tramways Company, trained as a barrister and got work in all Courts, Parliamentary Bar, Chancery Bar, the Queen’s Bench and the Old Bailey.

A consistent failure, however, or so he maintained, Richardson took up playwriting, with moderate success, and a breakthrough with the publication of a couple of short stories led to him being invited to write novels. Choosing subjects he knew, but with a comedic twist, his first, The King’s Counsel, was published by Chatto and Windus in 1902, and three more followed in 1903, all with a strong vein of satire and gratuitous references to whiskers. Richardson is credited as coining the term ‘face-fungus’, and Punch called him ‘Mr Frank Whiskerson’. His ability to write caricatures also developed into drawing them, and his later books and articles often featured his own sketches.

Like so many clowns, however, Richardson’s life ended tragically. Widowed before he turned 40, his appetite for writing had all but dried up by the time he published a book of poetry, Shavings, in 1911. Although he may have exhausted his peculiar topic of humour, he had remained a popular figure, opening fêtes, signing books, drawing cartoons and judging seaside beauty contests. But on Thursday 2 August 1917, The Times announced his death, aged 46: ‘Mr Frank Collins Richardson, barrister, and novelist, was found dead in his chambers in Albemarle-Street, Piccadilly, yesterday. An inquest will be held.’ The next day, Westminster Coroner, Ingleby Oddie, heard evidence from Richardson’s sister and ex-valet which showed he had been suffering from depression and was given to ‘alcoholic excess’, despite his successful business interests as director of two flourishing companies: a cataract had robbed him of sight in one eye, and he feared it would spread and he would go blind. He had died on 31 July from a cut to his throat, and the jury returned a verdict of suicide whilst of unsound mind.

Published in the second batch of Detective Story Club titles in November 1929, The Mayfair Mystery was the only one of Frank Richardson’s books acquired by Collins for a reissue. Though none of his others were deemed suitable for the list, its predecessor, The Secret Kingdom (1906), set in the imaginary country of Numania, featured Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson in one of their earliest parodies, and might have been an interesting contender.

DAVID BRAWN

April 2015

CHAPTER I (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

THE DEAD MAN (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

THE body of a man in evening-dress lay on the dull, crimson carpet.

The black eyes were staring fixedly at the electric light hanging from copper shades. The jaw had dropped. The dead man’s face was remarkably handsome. The forehead was broad, and indicative of considerable intellectual power. Strongly-marked black eyebrows jutted perhaps a little too far over the aggressive, aquiline nose. The chin was strong and determined. The close-cut, shiny black hair was silvered at the sides. But for a slight, almost dandified moustache, one would have thought that the features were those of a barrister, of an ideal barrister.

The small room in which the corpse lay had evidently been newly decorated. A smell of varnish was in the air. It was furnished simply and in good taste. The walls were panelled in dark oak, and the few ornaments proved their owner to be a man of excellent judgment in matters of art. A few books, the latest novels, illustrated and scientific papers, lay on a Sheraton table. In the grate burnt a fire of ship’s logs, emitting a fragrant scent that battled with the smell of paint.

In Who’s Who? the dead man’s biography was as follows:

OAKLEIGH, Sir Clifford, First Baronet; created 1903. G.C.B., D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S. Physician-in-Ordinary to the Princess of Salmon von Gluckstein. Born 21st August 1870. Son of John Oakleigh of Aberdeen and Imogen B. Stapp of Chicago. Education: Eton, Christ Church, Oxford. First-class First Public Examination 1891; First Class Greats 1892; Edinburgh University, Gillespie Prizeman. Recreations: shooting, yachting and hypnotism. Address: 218 Harley Street. Clubs: Athenaeum, United Universities, Garrick, Beefsteak, Gridiron and Arthur’s.

CHAPTER II (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

CONCERNING THE CORPSE (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

‘THANK God, I’ve found you!’

As the servant closed the door, Reggie Pardell, in evening-dress, his flabby face pallid, almost ashen, sank into a chair.

George Harding rose hastily.

The K.C. looked down at the frightened figure in the chair, went into the dining-room, and returned with a brandy-and-soda.

‘Drink that,’ he said.

While Reggie drank with long gulps, his eyes stared at the gaunt barrister.

As he scanned the clear-cut, intellectual face, with its piercing grey eyes, its long, sinister, thin nose and tight-shut vigorous mouth, he felt a sensation of returning confidence. At the same time, also, there floated through his mind a feeling of irrelevant despair. Each was thirty-eight years of age. They had been at Christ Church together. George was a brilliant advocate and Reggie was—well, Reggie was an ex-black sheep. A passion for backing losers had been his undoing.

Harding took away the glass.

‘Feel better?’ he asked.

The other nodded.

‘What’s the trouble now?’

It was eleven o’clock, and from the library one could hear the sound of carriages and cabs passing along South Audley Street. In the home there was complete silence.

Reggie shook his head.

‘It’s not a trouble of mine this time, not directly. But it’s the most awful thing that’s ever happened. That’s why I’ve come to see you.’

Harding smiled. His friends always came to him in time of trouble. There was something in the man’s vigorous personality that invited sympathy; his vast reputation for acumen and knowledge of human life rendered him an invaluable adviser in moments of difficulty or danger.

He went back to his chair and lit a cigarette, waiting for his friend to speak.

The first words that came from Reggie’s lips were:

‘Clifford Oakleigh is dead.’

‘Dead!’ cried Harding, aghast at the news that his best friend at Eton and Oxford, and indeed in the world, had died. Horrified, he pressed for particulars.

‘When did he die? How do you know?’

‘I have just come from his house.’

‘From Harley Street?’

‘He doesn’t use that as a house.’

‘I know. He lives at Claridge’s.’ The K.C. corrected himself.

Reggie shook his head.

‘He has lately taken, or rather built, a little house in King Street, Mayfair; just near here. Didn’t he tell you?’

‘Never a word.’

‘Well, he only moved in a week ago.’

‘But what were you doing there? I thought that you and he were not quite…’

‘No,’ said Reggie, grimly. ‘But he has been very good to me one way and another. He has lent me a lot of money; I wouldn’t have gone to him again, but…the fact is I’m his valet.’

The barrister gazed at him in surprise.

‘I was his valet,’ repeated Reggie. ‘He engaged me as a valet.’

‘You were his valet?’

Harding stared at the prematurely fat young man with three pendulous chins and an unbecomingly large waist. It seemed incredible to him that Sir Clifford Oakleigh, one of the most famous physicians of his day, one of the most brilliant men of all time, had selected that mountain of adiposity as his valet. Further, it struck him as extraordinary that a man like Reggie Pardell, a scion of one of the oldest families in England, should be willing to perform these duties.

Reggie explained.

‘You see it was like this, George…Harding. I was absolutely stony. Of course, I’d got clothes, and the run of my teeth, and so on. But I was broke to the world. Poor Clifford met me one day at Arthur’s and he guessed how things were. He made me a sporting offer. He said: “Look here, old chap, you have failed at most things. The only thing you do understand is clothes. Come and be my valet. I will give you £500 a year.” At first, I thought he was joking. But he wasn’t, and he installed me in this little box of his in King Street. Only part of the house is furnished; his sitting-room and bedroom and my bedroom. He never has his meals there. The charwoman comes in every day and sees to the place; all I had to do was to look after his clothes. It really was the most extraordinary arrangement that I’ve ever come across. It was philanthropy on poor old Clifford’s part, because my time was entirely my own.’

The other reflected.

‘It’s strange he never told me about this.’

‘Dear old Clifford wouldn’t,’ rejoined Reggie.

‘You see, he knew that I shouldn’t like it to be known that I was doing a bit of valeting. Well, after all, what’s the disgrace? My elder brother, Horace, is chaperoning the “Venus” at the Nasallheimers’ Gallery in Bond Street. It is his duty to show financiers and peers and people of that sort the beauties of Titian. Of course, if he ever succeeds in selling it, he will lose his job as vestal virgin to the “Venus”. And my cousin, Dartmouth, keeps body and soul and motor together by selling Stereoscopic Co. et Fils Cuvée Anonyme to unwilling aristocrats. Still, Clifford knew that I shouldn’t like people to hear that I was his valet.’

The lawyer’s knowledge of Reggie’s character told him that interruption would be useless. He must tell his story in his own way. He merely showed his impatience by taking out his watch and clicking it.

‘I know,’ said Reggie, accepting the hint.

‘Well, tonight I dined with three pals at White’s. We were going on to the Covent Garden Ball. But, somehow, an extra man turned up and someone suggested Bridge. You know I’ve not got a very good reputation for solvency, and I could see they’d be just as well pleased if I didn’t cut in, so at ten o’clock I left them. I thought at first of going on to the ball alone. But that struck me as being a dull scheme, and so I walked back to King Street.’

‘Yes, yes?’

‘I let myself in with the latchkey and went into the sitting-room, which is at the back of the house on the ground floor, the second room from the front. The front room is not furnished. And there I saw Clifford lying on the floor—dead.’

The barrister was silent at the horror.

‘Dead,’ he whispered at last. ‘My oldest friend, my best friend! What could have happened?’

‘That’s the mystery,’ answered Reggie. ‘That’s the extraordinary thing. What does a man, a man in robust health and strength die of…like that?’

‘Heart disease?’

Reggie shook his head.

‘No, not in this case. I know, in fact, that only three days ago Clifford went to his Life Insurance Office and increased his insurance enormously. Besides,’ and he shrugged his shoulders, ‘you know perfectly well that he was sound in wind and limb. You have shot with him. You know how deuced strong he was. Not an ounce of superfluous flesh on his body. No, no, it wasn’t heart disease.’

‘Then you suspect…’

Reggie leant over:

‘I suspect nothing. I’m afraid they may suspect me…the police may suspect…me.’

Harding threw himself back in his chair and drew a long breath.

‘Have you told the police?’

‘No, I came straight here. I thought it would be better to come straight here. But the police must be called in. You see how much worse it makes it for me if I don’t call them in at once.’

Harding rose from his chair and stood by the mantelpiece.

‘I can’t believe it!’ he said, ‘I can’t believe it! Isn’t it possible that you’re mistaken?’ he said, snatching at a hopeless gleam of hope.

Reggie shook his huge, flabby head.

‘No, no chance of that. I know death when I see it. I was in the Boer War, you remember. Besides, his chin had dropped; his eyes were staring. Poor chap, he was very good to me.’

Quickly Harding spoke:

‘I will go with you to the house. We must go at once. This is a terrible affair. No, we won’t take a cab. We must walk.’

The two passed out into South Audley Street.

They walked rapidly in the direction of King Street.

There was a quick fire of questions and answers.

‘Where did he dine?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What time did he leave the house?’

‘At seven-thirty.’

‘Was he dressed?’

‘Yes.’

‘What time did you leave?’

‘At seven-fifty.’

‘Did he know that you were going to the Covent Garden Ball?’

‘Yes.’

‘He seems to have given you a pretty free hand?’

‘Certainly. I was practically my own master.’

‘And no one else was in the house when you went out?’

‘No one.’

‘That seems extraordinary! What about burglars?’

‘Well, you see, I don’t think that anybody would know the house is occupied. The dining-room is shut up. There is nothing to burgle. There are only a few valuable vases and bronzes that wouldn’t appeal to burglars.’

‘So he would let himself in with his key, would he?’

‘Yes.’

‘How many keys are there?’

‘Only his and mine.’

By this time they had reached the door of a small house in King Street. The house had been newly built. The bricks were red, the paint was white, and the door was green with dull red copper fittings.

Reggie opened the door, and they passed into a narrow hall and thence to the sitting-room.

Scarcely had Reggie turned the handle when he started back.

‘My God!’ he whispered, ‘someone has been here. The light has been turned out!’

CHAPTER III (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE CORPSE (#uf3426624-facb-5a26-8c3a-6d886bfa06df)

WITH hesitating fingers he turned on the electric light, and then fell back nearly into the arms of Harding.

‘My God!’ he said. ‘It’s gone! There’s nothing on the floor!’

With wild, staring eyes he looked at Harding.

Harding returned his glance curiously. The conviction gradually growing in his mind was that Reggie had gone mad.

‘But I saw it, I saw it,’ said the other, detecting the suspicion. ‘I saw it, and I touched it. It was almost cold. It was lying there by the sofa—between the sofa and the fire. The head was on the ground. It seemed as though he might have fallen off the sofa. No, George, no. This is no hallucination. The body was there, as I told you, and it is not there now. Someone has taken it away!’

‘Thank Heaven,’ gasped Harding, ‘he may not be dead!’

‘Oh, yes,’ replied Reggie, firmly, ‘he is dead. Only the body has been taken away. That makes the mystery worse, more terrible.’

‘Come with me,’ said the lawyer, ‘this may be a matter of life and death for you. We must leave no stone unturned. I must search the house in your presence.’

And they searched it thoroughly. The kitchen door proved to be securely fastened: the windows had all been carefully closed. There was not a nook or cranny in which anyone could hide. No means of egress could be discovered.

At length, they returned to the sitting-room. Harding, who had had considerable experience of criminal work at the bar before taking ‘silk,’ felt himself completely nonplussed…provided Reggie was of sound mind. If the body on the floor was an hallucination, then the mystery ceased to exist. If his story—and he had told it lucidly and with no more excitement than the circumstances warranted—was accurate, that he had actually touched the dead man, then the mystery was so appalling as to be almost incredible. Either Clifford would return that night and, as a consequence, Reggie’s mental condition would be inquired into by people competent for such an undertaking or…or there were more things in heaven and earth…

Vainly he cast his mind this way and that, seeking a clue. Automatically he stroked the bronzes on the mantelpiece. Suddenly he took up a pair of spectacles which were lying there, open.

‘That’s curious,’ he commented. ‘I didn’t know Clifford had anything the matter with his eyes. He is one of the best shots I’ve ever seen.’

He was standing with his back to Reggie, who inquired:

‘What do you mean by that? He has the most wonderful eyesight. What makes you think he hasn’t?’

‘Why,’ exclaimed Harding, turning round, ‘these spectacles. A man does not wear spectacles if he has perfect sight.’

‘But Clifford never wore spectacles. These are not his spectacles.’

‘Are they yours or the charwoman’s?’

‘Certainly not.’

‘Who can have left them here?’

‘My dear Harding,’ Reggie answered, ‘since I have been here, not a soul has entered the house. I tell you he never receives anybody here. I don’t know what he keeps the place for except for the excuse for giving me my £500.’

‘Nonsense,’ replied Harding, ‘you could have taken £500 a year all right without his putting himself out to run such an expensive hobby as a house in King Street, even a little house like this.’

‘I tell you what it is, Harding, the whole thing beats me. I have never been able to understand why a man should have his consulting-rooms in Harley Street and sleep here. Of course, no man could live in Harley Street. It is like living in a dissecting-room. But with his reputation he could have brought his patients to…Bayswater or Tulse Hill.’

Carefully the barrister examined the spectacles. He placed them on his nose. Then he whistled.

‘These are a woman’s spectacles,’ he said. ‘I am almost sure of that. They are too small for a man’s face. And the extraordinary thing about them is that they are plain glass, practically plain window-glass. Now what has he got these here for? How did a pair of woman’s spectacles of plain glass come into the possession of an eminent medical man?’

‘I don’t know, Harding. I’ve never seen them before. I suppose he brought them here.’

‘But why, in Heaven’s name?’ queried Harding.

‘A woman does not give away a common pair of steel spectacles as a gage d’amour. You noticed they were open when I found them, as though they had just been taken off the owner’s nose.’

‘Well, what do you make of it?’

The lawyer shrugged his shoulders.

‘Make of it? I don’t make anything of it, at all.’

He affected an air of joviality.

‘But I tell you what it is, Reggie. When Clifford comes home we will have you put away in an asylum for the term of your natural life. A man who comes to one’s house late at night with cock-and-bull stories of corpses on carpets is not needed; there is no market for him. Now I’m going home.’

Reggie, as he let him out, asked: ‘Do you really think that he’s not dead?’

‘The only conclusion to which I have come is that either he is dead or you are mad…if that is a conclusion.’

‘Am I to tell the police?’

‘No. Certainly not. Good-night.’ He turned abruptly up the street.

Reggie remained at the door, looking after the tall figure that strode briskly along the pavement.

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_f61d575f-57ba-5b5c-b91a-b1405a212227)

THE ALLEGED ADA (#ulink_f61d575f-57ba-5b5c-b91a-b1405a212227)

‘OH, we’re not proud at all, are we? Not puffed up with pride, not likely.’

Attracted by the unattractive voice, Reggie looked to his right.

A female servant at No. 35, a much larger house, was seeking to engage him in conversation. This was not the first, the second, nor the third time that she had sought to gain the friendship and—who knows—perhaps, the hand of the ‘gentleman ‘valet in the mysterious house.

‘No, we’re not puffed up with pride,’ answered Reggie, ‘but we don’t converse with menials.’

‘Not when we’ve got our white waistcoat on, eh?’ the girl replied. ‘My word, you are a toff! You’re a deal toffier than your gov’nor. You’re too good for your guv, that’s what you are.’

‘Look here, Ada, we don’t need to go into that.’

The maid was not even pretty. She had a face of the colour and texture of pink blotting-paper. It was of the tint often to be seen on a hard-working hand, unbecoming on the hand, unpleasant on the face. He had no use for her.

‘Not so much of your Ada! My name ain’t Ada,’ she said, tilting up her nose.

‘I thought all scullery-maids were called Ada,’ answered Reggie.

‘That shows what little you know about scullery-maids, mister, and you don’t know anything at all about me. I’m not a scullery-maid. I’m an under-housemaid. £16 a year and beer money. That’s what I am. Scullery-maid, indeed!’

‘I beg your pardon,’ replied Reggie, who had no desire to prolong the conversation. He was on the point of shutting the door, but the girl was agog for a chat. ‘Next door’ was the great topic of conversation in the servants’ hall. ‘Next door’ was a mystery, and the valet of ‘Next door’ was the most glorious valet there had ever been. Apparently he had a position which for lack of labour was the ideal that all gentlemen’s valets strove to find. If his remuneration were in proportion to the comfort of his place, he would make a most desirable husband. That was the universal opinion in the servants’ hall of No. 35.

‘Don’t go in, mister,’ she pleaded.

‘Why not, miss?’ he answered.

‘Don’t call me miss: it’s so stiff like. Call me Nellie.’

‘I decline to call anyone Nellie. It’s a most repulsive name. I regret that your name is Nellie, but,’ he added judicially, ‘I am afraid you deserve it.’

‘Oh, don’t start chipping me, and don’t you go in, neither. Your guv. will be pleased to meet you when he comes back. It will be a great help for him to find you standing there.’

‘What do you mean?’ he inquired in surprise.

‘Well, if he don’t sober-up before he gets home, it will be a difficult job to get him indoors. He was that drunk! And I know something about drunkenness myself, Mr Man. I once had to give notice to one of my guvs for intemperitude. And he never was what you might call rolling drunk: he merely got cursing and fault-finding drunk. But I gave him some of my lip, I can tell you. A nice example to set the other servants!’

‘Who are you talking about?’ persisted Reggie.

‘Who should I be talking about but your guv.’

‘Well, then…Nellie, you’re not talking sense. Sir Clifford is a teetotaller.’

The words had slipped from him in his surprise.

‘Oh, he is a Sir Clifford, is he? Well, that’s something to know. Sir Clifford what, pray?’

But he would go no further.

‘Well, it’s something to know he is Sir Clifford. I don’t suppose there’s so many Sir Cliffords kicking about that I shan’t be able to find out what his full name is. Lor’, he was that drunk I thought he would never get into the cab. I thought I should have died of laughing. Oh, he’s a bad hat, your Sir Clifford is…to go about with a creature like that: a drab I call her.’

‘Look here,’ interjected Reggie, sternly, ‘what are you talking about?’

‘Oh, you want to know, do you? I’ve interested you at last, have I?’

She placed a value on her information.

‘Give me a kiss, mister, and I’ll tell you.’

She coquettishly put up her rough red face and he paid the price. He did not like paying it, and she did not regard his payment as liberal.

‘Why, our Buttons kisses better than that,’ she said. ‘Being kissed by you is like catching a cold. It’s a pity, isn’t it, that gentlemen’s servants aren’t allowed to grow moustaches? That’s where postmen have a pull. When I was living in Westbourne Terrace, I once walked out with a postman…he was proper, I can tell you…’

But Reggie stemmed the tide of amorous recollection. He insisted on knowing what she had seen.

Very deliberately, and in a manner entirely convincing, she said:

‘Just about a quarter past eleven I happened to be standing here; never you mind what for, old inquisitive, but my folks were at the theatre and I do what I like and no questions asked. I should like to see anybody ask ’em. They wouldn’t get any answer, not much…only a month’s warning. Suddenly your door opened and a sort of untidy middle-class woman comes out with your guv. He was so drunk he couldn’t stand. I thought she would have dropped ’im. She must have been a strong woman! But she got him into a four-wheeler as was waiting. Then she comes back and shuts the door, says something to the driver, jumps in, and off they goes. Such goings-on! And not the sort of woman a gentleman should keep company with, to my way o’ thinking; but when the drink takes ’em, you never know. I had a uncle—a Uncle Robert—who was just the same; he was an oil and colourman, too, in a fair way of business. Oh, dash, there’s our rubbish coming back. Must be going. So long!’

And she disappeared down the area as a motor-brougham, with the servants in conspicuous semi-military grey uniforms, dashed up.

Reggie, completely mystified, entered the house. A great weight was taken off his mind.

‘It is much better,’ he reflected, ‘to be drunk than dead…not so dignified, perhaps, but on the whole better…infinitely better.… Besides, I shan’t lose my job.’

CHAPTER V (#ulink_77a4bc07-f6e9-50a3-82c6-3bd4c78f5a64)

AT THE GRIDIRON (#ulink_77a4bc07-f6e9-50a3-82c6-3bd4c78f5a64)

ENGROSSED in thought, Harding scarcely noticed where he was going. His mind was full of the extraordinary circumstances that had occurred.

Automatically he stopped in front of his house. But he hesitated to go in. The December night was clear and crisp. It seemed to him improbable that were he to go to bed, he would sleep.

Therefore he walked on to Piccadilly, and eastwards past the Circus.

Suddenly he felt a hand clapped upon his shoulder, and a hearty voice inquired:

‘Are you on your way to the Gridiron?’

He turned round to find himself in the presence of Lampson Lake, a jovial, middle-aged man whose chief characteristic was his extraordinary versatility in failure. He had failed at everything, and on that account, perhaps, was universally popular with successful men.

At the mention of the club’s name Harding realised that he was hungry and the two turned into the Gridiron.

The single long room which constituted the famous club was desolate except for two men, Sir Algernon Spiers, the famous architect, and Frederick Robinson, a somewhat obscure novelist, who were seated together at the table.

The newcomers took two seats next them.

Robinson, a wisp of a man with a figure like a note of interrogation and hair brushed straight back without any parting, was, after his usual practice, dealing in personalities.

‘I can’t help thinking, Sir Algernon, that it is a very sound scheme of yours to wear your name on your face.’

‘What the dickens do you mean?’ asked Sir Algernon. ‘How do I wear my name on my face?’

‘I will explain. Your name is Algernon, is it not?’

‘Of course, my name is Algernon,’ replied the other, huffily.

‘Well, don’t you know the meaning of Algernon?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘It has a very curious origin. Waiter, another whisky-and-soda. A very curious origin. It would be idle for me to assume that you are not aware that you suffer from whisker trouble. In fact, you are at the present moment toying with your near-side whisker. You are massaging it for purposes of your own. Whether it will do any good I can’t say. But both you and I and any intelligent observer must be aware that you cultivate a superb pair of white face-fins. Now, whiskers were originally introduced into England by the founder of the Percy family. He came over with William the Conqueror. He was known among his friends as William Als Gernons, or “William with the Whiskers”; whence, says Burke, his posterity have constantly borne the name of Algernon. Curious, isn’t it?’

‘It’s damned impertinence, sir,’ roared Sir Algernon, purple with indignation.

‘On the contrary,’ replied Robinson. ‘It is merely useful information; very, very useful information. There is no need to thank me for the information.’

Then he turned his attention to Harding.

‘Ah,’ he said cheerily, ‘here we have the woman-hater.’

Harding gave him the lie.

‘I’m not a woman-hater,’ he said. ‘Life is only long enough to allow even an energetic man to hate one woman—adequately. If a man says he hates two women he is a liar or he has scamped his work, or he has never known a single woman worthy of his hatred. The ordinary “woman-hater” hates one woman and has no claim to the title. Would you call a man a football player because he has played football…once?’

He had no desire to talk. His desire was to eat a devilled bone and return home. But he had always considered it preferable to bore a man than to be bored by him. Also, he was in no mood for the absurdities of Robinson.

‘Still, you have never married,’ pursued the novelist.

‘I told you I was not a misogynist,’ replied Harding, with a perfunctory smile. ‘No girl that I ever knew was so radically bad as to deserve me.’

‘Nonsense,’ broke in Lampson Lake, ‘my dear old chap, I don’t believe there is a man in England who is so anxious to marry as you are. You have got everything in the world except a wife. You are a huge success. You have got a beautiful house…’

‘Thanks to the advice of Sir Algernon here,’ Harding answered.

‘Heaps of friends,’ continued the other. ‘A face that would not exactly frighten the horses. Why, my dear fellow, your whole life is directed with a view to a happy marriage. You are only looking out for…the impossible.’

‘What do you mean by the impossible?’ queried Robinson.

‘Oh, not you,’ replied Lampson Lake, glancing at the novelist, ‘I don’t go in for personalities. You needn’t worry. The impossible is the perfect woman. And that is what Harding is looking for.’

And herein Lampson Lake was right.

Indeed, Harding, tall, sparsely built, handsome—in a non-theatrical manner, despite his clean-shaven face—with bright brown eyes and athletic figure, seemed rather a happily-married man than a man whose one grief was the fact that he had never yet met a woman with whom he had desired to live for the term of his natural life. He knew that life should be duet. The confirmed soloist is regarded with mistrust. If a man declines to take a partner into his life’s business, surely that life must indeed be a dull and drab affair. And Harding was exceedingly popular with both men and women. Yet he had never come across a woman who could rouse in his heart any feeling warmer than the great affection he had for Clifford Oakleigh.

‘But you’re not married either,’ said Sir Algernon to Lampson Lake. ‘Are you looking for the perfect woman, too?’

‘It is no good my looking,’ he replied. ‘No woman will marry a failure—a specialist in failures, that is.’

‘On the contrary,’ interposed Robinson, ‘some of the most shocking failures I know are married.’

‘Yes, but they married first,’ explained Lampson Lake, ‘they became failures afterwards. It is a great consolation for a man, who has made a muddle of his life, to throw the blame on his wife, especially if he can get his wife to believe it.’

‘A perfectly trained wife will believe in anything,’ was the architect’s comment.

‘Except in her husband,’ corrected Robinson, who, not being married, knew all things about wedlock.

‘A woman wants to marry a man who will succeed or who has succeeded, and I think most women prefer the first. It is surely the greatest privilege of her life to accompany the man she loves from poverty to riches, from obscurity to fame.’

‘No doubt,’ answered Lampson Lake. ‘But I am not in a position, and I never have been in a position, to give a woman the chance. I am one of Nature’s failures. And, mind you, I’m not complaining. The world has need of failures. It is a great pleasure to any K.C. who was called to the Bar at the same time as myself to realise that no sane solicitor would ever give me a brief. Besides, people are kind to me because they are not jealous. They give me their best in the way of food and wine because they know I am not too busy to notice such things. They trust me with their wives because they know I am not ambitious, with their daughters because I am too poor to marry. Oh, I have an excellent time, thank you.’

‘Then, Lampson,’ asked the K.C., ‘you really enjoy not being a…success?’

‘Well, I shouldn’t like to be a failure…as a failure. I am, at any rate, the leading failure of this club. But that’s not saying much, because we’re all famous here; except, of course, Robinson. He is merely notorious.’

‘Thank you,’ replied Robinson, smiling. ‘I know you meant to be rude, but you failed even at that. Fame is what we call the reputation of people who are dead, of great men who are dead. Notoriety is the reputation of great men who are alive.’

‘What,’ asked Lampson, ‘would you call Clifford Oakleigh? Is he famous or is he notorious?’

‘As he is alive,’ replied Robinson, ‘he is notorious. When he is dead he will be famous.’

Harding shot a keen glance at him. He was on the point of speaking. But his lips shut tight.

‘He is a most extraordinary man,’ said Sir Algernon. ‘You know I built that house for him in Pembroke Street, No. 69. He gave me an absolutely free hand to do anything I liked, and I must say I was pleased with what I did. Everything went well until the house was almost finished, and then suddenly Clifford, who is one of the best chaps in the world as we all know, began taking a very great personal interest in the details. So keen was his interest that it became very awkward for me, as a professional man. And, mind you, I discovered that he knows a great deal about architecture. In fact, I have never come across anything that he doesn’t understand. Well, we had a sort of amicable quarrel. We agreed to differ. And the result of the whole thing was that the completion of the building was taken out of the contractor’s hands and he gave the job to some tenth-rate builder that he had discovered in Hammersmith.’

Harding had listened in astonishment to the statement made by Sir Algernon. He had never heard that his friend was building a house in Pembroke Street. Yet another house!

He turned to the architect.

‘You surprise me, Sir Algernon. Clifford and I, as you know, are old friends, and he never mentioned to me the fact that he was building a house. The ordinary man can’t buy a motor without boring his friends to death with the subject. It is very strange that Clifford should not have mentioned to me a little thing like that. How long has it been built?’

‘Oh, about six months!’

‘Six months!’ exclaimed the other. ‘But he doesn’t live there?’

‘No,’ replied Sir Algernon, ‘I don’t think he intends to. I think the idea was to let it furnished. It is one of his hobbies, I think.’

‘A very expensive hobby,’ interposed Lampson Lake.

‘Fortunately, he can afford expensive hobbies,’ said the architect. ‘I understand that it is superbly furnished. And now I come to think of it I remember he said that if he let it he would expect to get £2000 a year. No. 69 is one of the smallest houses in Pembroke Street. The idea of £2000 a year is absolutely preposterous.’

To the barrister’s thinking, the whole scheme was preposterous. No matter what Clifford Oakleigh’s fortune might be, it would not stand a habit of building and furnishing houses on which a prohibitive rent was placed.

‘I should like to have a look at the place,’ continued Sir Algernon. ‘But he made me understand,’ he added laughing, ‘that he would never receive me in the house…so as to avoid painful memories as to my professional pride. However, he gave me an excellent dinner at the Savoy the other night. He is a very curious man; certainly, he is a very curious man.’

‘Not for a genius,’ interposed Harding.

It seemed to him uncanny that these four men should be sitting up at night talking of a dead man as though he were alive. Two or three times it had been on the tip of his tongue to tell them of the tragedy that had just occurred. Had it not been for the fact that Reggie might be hopelessly involved therein, he would have spoken. Another reason that kept him silent was the incongruity of his position. His best friend was dead, and he was taking supper at the Gridiron. Why was he taking supper at the Gridiron? He himself hardly knew. His nerves had been shattered by the events of the night.

‘You think he is a genius?’ asked Robinson.

‘Certainly he is,’ Harding replied. ‘Ever since I have known him he has been a genius. He was a genius at Eton, he was a genius at Oxford, and he has been a genius in London. He has one of the largest practices of any physician in London, and what is more he hardly ever has a failure. Then look at “Baldo”. That was really one of the greatest inventions of the age.’

He was alluding to a preparation invented by Clifford that consisted of a white cream which one applied to one’s face in the morning and it instantly removed the night’s growth of hair. By this useful device, a complete substitute for the razor, Clifford Oakleigh had already made nearly half a million.

‘A slight application of “Baldo” to your whiskers, Sir Algernon, would, I am sure, be efficacious,’ said Robinson.

‘Oh, damn my whiskers,’ replied the architect.

Robinson politely responded: ‘My sentiments entirely.’

‘Directly Robinson begins to talk about whiskers, I go home,’ said Lampson Lake, rising.

‘I, too.’

Harding paid his bill and, incidentally, Lampson Lake’s, and left the club.

CHAPTER VI (#ulink_cba8755c-824e-5e50-95f1-ab6b6ef34dbc)

THE TROUBLE WITH MINGEY (#ulink_cba8755c-824e-5e50-95f1-ab6b6ef34dbc)

THE next morning, when Harding reached his chambers in King’s Bench Walk, he noticed that his clerk, Mingey, was looking more dismal and lugubrious than usual.

Were it not that the man was so excellent at his business, Harding could not have tolerated the presence of so lamentable a figure. Mingey was six feet tall, intensely lean, with a dank, black, uncharacteristic, drooping moustache, and a pallid face that looked as if it required starching. He always wore shiny black clothes, and presented the appearance of an undertaker with an artistic taste in his calling. Today there were red rims round his colourless eyes.

‘Cheer up, Mingey,’ said Harding, heartily,

‘this is not your funeral, is it?’

‘Excuse me, sir, but something terrible has happened…my daughter, sir.’

‘Ill, is she?’ inquired Harding. ‘I’m very sorry…’

He went to the table and cast his eyes over his briefs.

‘Worse than that, sir,’ replied the clerk, ‘she has disappeared.’

‘Disappeared!’ echoed the K.C. ‘Perhaps she has eloped,’ he suggested.

‘No, sir, she is not that sort of girl. She never had, to my knowledge, any love affairs. She once did show a sort of feeling for one of our ministers, but he turned out to be engaged to a lady in Scotland, so nothing came of that.’

‘Tell me all about it,’ said Harding, seating himself at his table and preparing to listen.

Succinctly the clerk made his statement. His experience of the Law courts enabled him to do a very unusual thing. He told a simple story in a simple way. It appeared that Miss Mingey was devoted to the creed which her father had discovered was, of all creeds, the most suited to his spiritual wants. [Mr Mingey was, by persuasion, a devout Particular Strict Baptist: an intensely select creed with only two places of worship, one in Peckham and the other in Monmouth Road, Bayswater.] An entirely good girl. She took no interest in clothes or young men. She was, as her father put it, ‘an intellectual girl much given to book-learning.’ As to her appearance, even paternal pride would not enable him to say that she was good-looking.

‘Here is her photo, sir,’ he added to prove his statement.

But the photograph did not quite bear out his contention.

Harding gazed at it intently.

It represented a girl of about twenty—nineteen Mingey maintained was her actual age. Her features, so far as one could judge from a full-face photograph, by a cheap and inadequate practitioner, were regular; she wore spectacles; her hair was done in an unbecoming way; her dress was abominable. It was rather clothing than clothes. With no evidence as to her complexion and her figure one could not say whether the girl was good-looking or plain; but the fact that she took no trouble with her hair, that her dress stood in no relation to the fashion—even, so far as he knew, to Bayswater fashion—that she was photographed in spectacles, proved that she regarded herself as unattractive. A girl who takes this view is almost certain to be right.

He handed the photograph back.

According to the father’s story, after a meat-tea with her mother she had gone out to post a letter. She did not return.

‘She was happy at home, Mingey, was she?’

‘Perfectly, sir. She always attended service twice on Sundays. No, I have never known a girl who was happier, or who had more reason to be happy.’

‘Quite so,’ said the K.C. ‘And no affair of the heart, you say?’

‘Certainly not, sir.’

‘But as to the minister who married the Scotch lady?’

‘Sarah had too much self-respect, sir, to get mixed up with a married man. Directly Mr Septimus Aynesworth married, she—so to speak—cut him out of her life.’

‘Did you go to the police-station?’

‘First thing this morning, sir.’

‘Well, my dear Mingey, I shouldn’t be alarmed if I were you,’ he said, trying to administer consolation. ‘It may be some curious freak…some girlish whim. You will probably find her at home when you get back.’

Mingey shook his head.

‘I’m afraid not, sir. You’ve noticed there have been two mysterious disappearances lately of young girls. They both met their death. There are always three of these things! Sarah will be the third.’

Shaking with grief, he shambled to the door.

‘Wait, wait, wait!’ cried the banister.

‘Surely, surely it was to her that I gave a letter of introduction to Sir Clifford Oakleigh the other day. What did you say the matter was? Her nerves, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes, sir, nerves. It was wonderful the way he put her right then and there. And no charge, sir, to a friend of yours, sir. He’s a wonderful man, sir. She only paid one visit and he cured her completely.’ Woefully he added, ‘And to think it was all no good.’

Then he went out of the room.

CHAPTER VII (#ulink_3bc14bbd-0a77-5b1f-973e-a3439cbb1bb0)

MAINLY ABOUT LOVE (#ulink_3bc14bbd-0a77-5b1f-973e-a3439cbb1bb0)

THAT night Harding fell in love.

It came about quite suddenly.

At first he did not know what was the matter with him, but gradually the conviction forced itself upon him that he, George Berkeley Harding, had fallen in love at first sight, just as a boy at Eton falls in love with a Dowager-Duchess.

It was during dinner at the Savoy that he became aware of his condition.

As the Courts did not sit on Saturday afternoons, he had walked up to King Street and inquired of Reggie for any news of Clifford Oakleigh.

Reggie had answered in the negative. He had suppressed the servant girl’s story, because he had not been convinced in his mind that she was a witness of truth. She might only have been making fun of him—a course of conduct which he would have resented. If, in very truth, Clifford had left the house drunk with a ‘creature’ he would certainly return, and he would not like the disagreeable fact recounted even to his best friend.

Harding had been in two minds. It was obviously his duty or Reggie’s to inform the police of the mysterious occurrence. But, at the same time, as the story was so completely incredible and rested solely on the evidence of Reggie, he thought it might be wise to wait another day. In the meantime, Clifford might return, or Reggie might develop some conspicuous symptom of insanity.

Throughout the afternoon he had vainly puzzled his brain for a solution.

With a clouded brow he had driven up to the Savoy to dine with old Mudge, the eminent family solicitor—solicitor incidentally to Clifford and himself.

From Mudge’s company or from the guests likely to be invited by Mudge he did not expect much amusement.

He found his host and hostess in the hall waiting for him.

Mrs Mudge was obviously Mrs Mudge. She had no figure, no individuality, and no features. Neither had she any colouring. She was, indeed, so colourless as to be almost invisible. When she was with Mr Mudge one could recognise her as his wife. Apart from Mr Mudge one would never have seen her at all.

Harding’s heart fell. He had expected, at worst, a party of men. However large the actual party was to be, Mrs Mudge’s presence would cast a gloom over it. A skeleton at a banquet would be the ‘life and soul of the party’ compared with Mrs Mudge. Horror of horrors, Mr Mudge announced that he was only waiting for one lady.

It flashed through Harding’s mind that it might be possible to say that he had suddenly been called to Scotland, or to state on oath that he was dead, or to tell some other monstrous lie and leave the building.

Then it was that the thing happened.

Sumptuously gowned, magnificently jewelled, a figure glided across the red velvet carpet. Her hair of deep brown was arranged in the French fashion, which on an English woman generally produces the effect of an over-elaborately dressed head, but was particularly becoming to her. Her profile was almost Greek, her violet eyes shone bewitchingly under long eyelashes. But the greatest beauty she possessed was her wonderful complexion like peaches and cream; it was daintily tinted, obviously caressing to the touch. Harding noticed that her figure was in keeping with her other gifts. She walked with all the grace and confidence of an American woman, and she could not be—well, she could not be more than twenty. Oh, if only he was to dine with her!

To his surprise she approached Mr Mudge. This marvel of grace and beauty deliberately went up to the old man with the snow-white Father Christmas beard—a polar beaver of the first water, to be technical—and said:

‘Mr Mudge, I think. Mr Mudge, I’m sure.’

‘May I introduce my wife…Miss Clive. Mr Harding…Miss Clive.’

When the introduction was effected the old man asked:

‘But how did you recognise me?’

‘Ask yourself, Mr Mudge,’ she replied, smiling.

‘Look round this room. Are there any other solicitors here? Obviously you are the only eminent family solicitor present. And you are clearly…oh, so clearly Mr Mudge.’

This little speech had revealed to Harding the additional fact that she was possessed of beautiful teeth. Was the woman in all things perfect? Perhaps she would turn out to be stupid.

He shuddered at the thought. How terrible! What ignominy to fall in love at first sight with a woman who was a dolt!

During dinner he became convinced of two things, one that she was a brilliant woman, and the other that Mr Mudge did not know how to order a meal.

On all subjects she talked, and on all subjects she talked well. Her mind, indeed, seemed to be filled with information that as a rule can only be acquired by personal experience.

He, himself, made every effort to interest her. He even made a sacrifice very uncommon in a barrister. He forbore to tell her anecdotes indicative of his forensic acumen.

The Mudge beard worked hard. He ate heartily and spoke little. Mrs Mudge, after the entrée, had practically ceased to be present.

Harding and Miss Clive performed a conversational duet. Her face mesmerised him. He absorbed it with his eyes. And strangely enough, although he realised he had never in his life seen any woman so beautiful as she, yet there was about her face something not unfamiliar. Was there any truth in the theory of the transmigration of souls? Had he, in a previous existence, wooed and won this marvellous woman? If he had seen her before in this life, he would certainly have remembered her. There were many men at the Savoy, dining at tables near, who stared at her. He was quite convinced that no one of those, if he met her again, would think he met her for the first time. Why was memory playing him such a strange trick? He, who always prided himself upon the fact that he never forgot names or faces, could not shake off the idea that he had seen her before.

He put the question to her:

‘I can’t help thinking, Miss Clive, that I have met you somewhere. Do you remember ever having seen me?’

‘Your name,’ she answered laughing, ‘is very familiar to me, but I have completely forgotten your face.’

As he handed her into her motor, he said:

‘May I come and see you?’

She smiled graciously.

‘Certainly, Mr Harding. I shall be delighted.’

‘On what day?’

‘I am often in about tea-time.’

‘But what day?’ he persisted.

Pouting her lips into a rose-bud, whilst her eyes twinkled, she answered:

‘Oh, please, won’t you take your chance, or am I asking too much? Besides, I am on the telephone. 2835 Mayfair.’

‘2835 Mayfair is the most beautiful telephone number in the world. But what is your address?’

‘Sixty-nine Pembroke Street.’

Then the motor glided off.

She was living in Clifford Oakleigh’s house.

CHAPTER VIII (#ulink_20287b26-3c27-59cc-a906-d99a4604824c)

2835 MAYFAIR (#ulink_20287b26-3c27-59cc-a906-d99a4604824c)

HE went back to Mudge, whose duties as a host, so far as the speeding of the parting guest was concerned, he had usurped.

The solicitor, while an attendant helped him with his greatcoat, was being told by his wife on no account to neglect putting on his muffler. He extricated his huge beard from his coat and draped it satisfactorily over the muffler.

‘What a charming woman!’ exclaimed Harding.

‘I’m delighted to have met her.’

He was intent on extracting particulars. Throughout dinner she had given him no hint as to her circumstances. Beyond the facts that she was Miss Clive, that she was extraordinarily beautiful and fascinating, and that he was hopelessly in love with her, he knew nothing. And yet he did not like to put definite questions to Mudge. He felt that any curiosity exhibited by him would reveal the state of his affections.

‘Is she by any chance the daughter of Frederick Clive—in the wool business?’ he asked, nonchalantly.

He knew of no Frederick Clive in the wool business; he knew of nobody in the wool business; he had but a vague idea of what the wool business was. But the question served its purpose.

‘No,’ replied the solicitor, ‘her father is not alive: neither of the girl’s parents is alive. I’m glad you like her,’ he added, ‘I fancy she takes an interest in you.’

‘You flatter me,’ Harding answered gallantly.

At that moment the lumbering Mudge landau drew up at the door. The shapeless Mudge footman, in the ill-fitting Mudge livery, opened the door and the Mudges entered. Much to his annoyance they did not ask him whether they could give him a lift. He was athirst for information as to Miss Clive. But the landau drove off into the Strand, leaving him alone on the pavement.

However, he knew that her telephone number was 2835 Mayfair.

When he reached his home, he took up a Court Guide and searched the ‘Clives’ for a hint of elucidation. He had faint hope that he would trace her. He found that there existed two Captain Clives; there was also a General Clive; and a Mrs Clive lived in Campden Hill Gardens. They might or might not be related to the only woman in the world.

He felt an irresistible desire to ring her up on the telephone. Irresistible though the desire was, he resisted it.

Heavens! he thought, he must be phenomenally in love to think even for a minute of making himself so ridiculous. Even if he were to ring her up and announce that he had broken his leg, or changed his religion, or grown a beard, such a proceeding would not fail to be regarded as an intolerable impertinence. To summon her to the telephone and say, ‘Are you Miss Clive? I have a shrewd suspicion that your house is on fire. A well-wisher,’ was a course that actually suggested itself to him. He would love to hear her voice. After all, he was in love with her. She was bound to find out that he was in love with her. It would be the object of his life to tell her that he was in love with her. Why should he not let her suspect at once the condition of his feelings?

Although it is idiotic to fall in love at first sight, it is not an unpleasant occurrence to be fallen in love with at first sight. At any rate, she could not take offence. He would zealously lay siege to her heart.

Suddenly he seized his courage in both hands and went to the telephone.

‘2835 Mayfair, please.’

…

‘Are you 2835 Mayfair? Can I speak to Miss Clive?’

…

‘Oh, you are Miss Clive?’

His face broke into a smile.

‘I hope you won’t think I’m awfully rude. I know I have no business to wake you up.’

…

‘Oh, you have only just got into bed. So you have your telephone by your bedside. How very convenient!’

He noticed that she had not asked who he was. Could it be—obviously it must be—that she had recognised his voice? How delightfully intimate was the knowledge that she was talking to him from her bed! How marvellously beautiful she must look in bed!

‘Oh, you know who I am. Yes, I am Mr Harding. George Harding. And I rang you up because I am most anxious to know whether you will be in between four and five tomorrow. I am very methodical,’ he added, by way of explanation, ‘and I never like to go to bed without knowing exactly what I am going to do the next day.’

But her answer displeased him.

A shade of disappointment passed over his face.

‘Well, on Monday?’

To this query the reply was satisfactory.

‘Good-night. I am so sorry to have disturbed you.’

He glanced at his watch.

Twelve o’clock. Good Heavens, there were forty hours to get through before four o’clock on Monday!

He looked at his engagement book. It was good to know that he was lunching out with some cheery friends. The afternoon he would spend in paying calls, and in the evening he was dining with ‘The Beavers’ at the Ritz. He was sure of a delightful evening at the best of all London dining clubs. ‘The Beavers’ would not break up until well after twelve: there would be delightful conversation and merry jests. And on Monday he would be busy in the morning and afternoon in Court.

Yes, he thought, it would be quite possible to live through those forty hours.

Picturing to himself the huge joy of the forty-first he undressed and went to bed.

Sunday passed far less tediously than he had dared to hope.

On Monday morning the papers were full of the disappearance of Mingey’s daughter. Disappearances, apparently, were the order of the day; tunnel murders were no longer in fashion. In two papers which he read there were leaders on the subject. These journals were seriously alarmed. It appeared that no one was safe. Anybody, the most unlikely person for choice, might vanish at any moment. The Morning Star maintained that Parliament ought to interfere. The Morning Star always believed in the omnipotence of Parliament, mainly because it was against the Government. If the weather was bad for crops—which the weather always is—if a church was struck by lightning, the Morning Star tried to rouse the legislature from its lethargy. At the first symptom of the end of the world the Morning Star would certainly urge the Government to take strenuous action to frustrate the peril.

The facts given were exactly as Mingey had described them. There were no new details. The girl had left her humble home in the Monmouth Road, Bayswater, and she had not yet returned. The parents were disconsolate and could suggest no clue. The Morning Star gave a portrait, a wood block, that made the heroine so painfully unattractive that any suggestion of an amorous solution of the matter appeared impossible. As he walked along Piccadilly on his way to the Temple, most of the contents bills bore the legend:

MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE OF A BAYSWATER GIRL

However mysterious the disappearance of this girl might be, he reflected, it was not so mysterious as the appearance of Miss Clive in his life.

Miss Clive! He did not even know her Christian name. He ran through a list of names suitable for beautiful women, but he could not fix upon one which seemed suitable for her. She required a stately name, a beautiful name.

Gwendolen was possible but not adequate. Katherine would not be out of the question. He dismissed contemptuously Winifred and Hilda and Margaret and Maud. Mary was, perhaps, of all names the most beautiful, chiefly in a measure owing to its sentiment. He would not be disappointed if her name was Mary. It would be the right name; the only possible name. As she was perfect in figure and in face, there would be no jarring note in her name.

It could not be that she would answer to the name of Muriel or of Nellie.

He shuddered at the thought.

CHAPTER IX (#ulink_fa42a130-22bd-532d-be5b-a7f0d5ffc745)

69 PEMBROKE STREET (#ulink_fa42a130-22bd-532d-be5b-a7f0d5ffc745)

THAT afternoon, when he rang the bell at 69 Pembroke Street, he was in an ecstasy of happiness. So triumphant was he, that no fear lest she should not be at home crossed his mind.

And she was at home.

A dignified butler showed him to the drawing-room, which was furnished entirely in the fashion of Louis XV. Every piece of furniture in the room was genuine. Each ornament was a veritable specimen of the period.

He felt that he was out of place, angular, awkward, hideously modern in these beautiful antique surroundings. She, on the other hand, though dressed in the height of the fashion of the day, seemed perfectly in the picture. All beautiful things are, as has been well said, of the same period.

‘How good of you to be in, Miss Clive!’

‘How good of you,’ she corrected, ‘to keep your word!’

As he looked at her it seemed to him that she was genuinely pleased at his arrival.

‘I hope you have forgiven me for ringing you up in such an unmannerly way. But I was very, very anxious to see you again.’

‘You were, really?’ she asked, her eyes looking straight into his.

‘Really,’ he replied.

He felt that he was making headway. But still it seemed absurd to be in love with a woman of whose character and of whose antecedents he knew nothing. He hoped that she would enlighten him in the course of the conversation.

Vainly, however, did he strive to make her talk about herself. Of all women she appeared to be the least egotistical. She was as sensible as a man. She showed no sign of desiring to talk about ailments that occurred to the body. If a body is not in good condition it is not a matter to be mentioned in polite society. Either one is well or one is not well. The condition of ill-health is not suitable for discussion.

During tea, he mentioned the fact that she had taken the house belonging to a friend of his.

‘Do you know Sir Clifford Oakleigh?’ he inquired.

‘I have never seen him,’ she answered, ‘but I understand that he is a great friend of yours.’

‘He is my greatest friend, or rather…’ he was on the point of adding, ‘he was my greatest friend.’

For an instant it seemed to him that it was disloyal to his love not to tell her the mystery of the little house in King Street: he felt also that he had been disloyal to his friend in not going to find out if Reggie had any more information. On the whole, there was no object in telling Miss Clive of the strange events of Friday night. What interest would she take in a landlord whom she had never seen?

‘It is a very beautiful house,’ he commented.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I think it is a perfect little house. All the rooms are as charming as this.’

‘But £2000 is a preposterous rent.’

‘I don’t think so,’ she answered, shrugging her shoulders and speaking as one to whom money is of very slight importance. ‘It’s the most perfect house…of its kind…in London, and one must pay for perfection.’

Deeply in love though Harding was, he felt considerable pleasure in this evidence of Miss Clive’s wealth.

He remained talking to her for half an hour and then reluctantly rose to leave.

‘A few friends of mine are coming to dinner on Friday at a quarter past eight at the Carlton. I should be delighted if you would come too.’

She thought for a moment, and then said:

‘On Friday, let me see. What day is this? This is Monday. Oh, yes, I shall be delighted. Thank you very much.’

Then he went away and reflected on the question of which of his friends deserved the privilege of meeting Miss Clive. Clifford Oakleigh should have headed the list.

The thought called to his mind his nearness to King Street. He would go and see Reggie and ascertain if there were any news.

Reggie opened the door and received him with enthusiasm.

‘It’s all right, my dear Harding,’ he said. ‘He’s alive, at any rate.’

Harding mistrusted him.

‘I won’t believe it on your evidence alone.’

‘Here’s the evidence of his own handwriting,’ said Reggie, and he produced from his pocket an envelope containing a plain sheet of notepaper. ‘I found it in the letter-box this morning.’

Harding looked at it curiously.

‘Yes,’ he said, as he examined the envelope, ‘it is his handwriting. But do you know it seems to me to lack a certain amount of vigour. It is not so strong, not so bold as his handwriting used to be. Am I to read the letter?’

‘Yes, certainly.’

This is what he read:

‘Monday.

‘Shall be back tomorrow. Say nothing to anybody.

‘CLIFFORD OAKLEIGH.’

‘Well, that’s all right,’ said Harding, with a sigh of relief. ‘At any rate, he is safe. We know he is alive. But beyond question, his handwriting has altered. I should say he must be ill: it is certainly very feeble, for him. And how did the letter come?’

‘It was dropped in the letter-box. I heard a ring.’

‘You know, Reggie,’ said Harding, thoughtfully, ‘this makes the matter even more mysterious than it was before.’

‘You don’t think,’ answered Reggie, ‘that it is possible that this letter is a forgery. That it was done to prevent my going to the police?’

‘I don’t think so,’ the other replied; ‘a forger would have copied the writing exactly or would have made mistakes here and there. This note is clearly written by our friend, but written under circumstances which are unusual. He has never, to my knowledge, had a day’s illness in his life. I’m afraid he is ill now.’

Reggie might have suggested that his master was recovering from a very serious drinking bout. But he made no such suggestion.

The K.C., with a great weight off his mind, but with a far more astonishing problem on his brain, went out of the house.

At ten o’clock the next morning Reggie heard the sound of a latchkey in the door.

With bated breath he listened and darted into the hall.

The door opened and Clifford Oakleigh entered.

A man in the prime of life, strenuous and active, obviously in the most robust health.

The theory of drunkenness fell to the ground.

He closed the door. He nodded to Reggie.

‘Good-morning.’

‘Good-morning, sir.’ answered the valet, every inch a valet.

‘You got my note, eh?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘By the by, what time did you come in from the Covent Garden Ball on Friday night?’

‘I didn’t go to the ball, sir.’

Sir Clifford looked keenly at him.

‘What did you do? When did you get in?’

‘Soon after ten.’

The eminent physician was on the point of putting a question to him, but he stopped, as though suddenly realising that he knew the answer to the question.