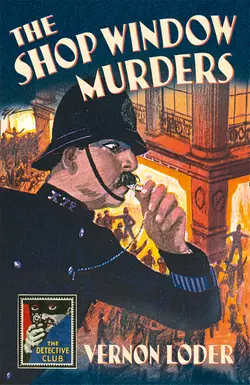

The Shop Window Murders

Vernon Loder

Nigel Moss

The delight of Christmas shoppers at the unveiling of a London department store’s famous window display turns to horror when one of the mannequins is discovered to be a dead body…Mander’s Department Store in London’s West End is so famous for its elaborate window displays that on Monday mornings crowds gather to watch the window blinds being raised on a new weekly display. On this particular Monday, just a few weeks before Christmas, the onlookers quickly realise that one of the figures is in fact a human corpse, placed among the wax mannequins. Then a second body is discovered, and this striking tableau begins a baffling and complex case for Inspector Devenish of Scotland Yard.Vernon Loder’s first book The Mystery at Stowe had endeared him in 1928 as ‘one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers’. Inspired by the glamour of the legendary Selfridges store on London’s Oxford Street, The Shop Window Murders followed, an entertaining and richly plotted example of the Golden Age deductive puzzle novel, one of his best mysteries for bafflement and ingenuity.This Detective Club classic is introduced by Nigel Moss, who looks at how Loder’s books are still acclaimed today by reviewers for being ‘as different from the standard whodunits of his colleagues as champagne is to soda water.’

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd 2018

First published in Great Britain by

W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1930

Introduction © Nigel Moss 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1930, 2018

Vernon Loder asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008282981

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008282998

Version: 2018-08-24

Contents

Cover (#ub07d3e7d-aff2-5e40-a389-0ab8e7aca5dc)

Title Page (#uab9df4e9-22d0-59f7-8ab5-b4dcac2bbc9a)

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

VERNON LODER was a popular and prolific author of Golden Age detective mysteries and spy thrillers. He wrote 22 titles during the decade from 1928 to 1938. Subsequently Loder has been out of print and largely overlooked. Fortunately, the tide is turning. In 2013/14, two noted crime fiction commentators, Curtis Evans and J. F. Norris, championed a number of early Loder titles, the latter in a series of enthusiastic reviews. A flurry of e-reader versions of Loder stories followed. But it was not until 2016 that Loder made his first return in print since the 1930s with the re-issue of his first novel The Mystery at Stowe (1928) as part of the Collins Detective Story Club reprint series. In the original Preface, the Club’s Editor, F. T. (Fred) Smith had welcomed Loder as ‘one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers’.

The Shop Window Murders (1930) was Loder’s fourth novel, after The Mystery at Stowe (1928), Whose Hand? (1929) and The Vase Mystery (1929). It was published by Collins in the UK, and with the same title by Morrow in the USA. The storyline is intriguing and unusual, with one of Loder’s more ingenious plots. The setting is Mander’s Department Store in London’s West End (loosely modelled on Selfridges in Oxford Street), owned by Tobias Mander and famous for its elaborate window displays. Early on a Monday morning, the crowds of passers-by pause to watch the window blinds being raised on a new weekly display, but the onlookers quickly realise that one of the wax figures is in fact a human corpse, shot and placed among the mannequins in the window display. Shortly afterwards a second victim is discovered, and this striking tableau begins a baffling and complex mystery tale. Was it murder and suicide, or double murder?

Loder draws a wide cast of diverse suspects, each with a motive for the killings. To a toxic mix of jealousy, fear, panic and anger, he adds further colour to the story with a proliferation of bizarre circumstances and enigmatic clues, displaying some fiendishly intricate plotting.

The case raises a fundamental question: why did the perpetrator of the killings leave so many signs and clues? Did it show a confused mind? Or was this a deliberate and clever attempt to confuse the police by leaving a trail of red herrings and different angles which implicated more and more characters and made proof of guilt harder to determine?

The police investigation is led by Inspector Devenish of Scotland Yard, who makes his sole appearance in Loder’s canon of detective novels. Devenish is intelligent, workmanlike, tenacious and indefatigable. He displays a strong moral compass, giving short shrift to those who lie when questioned, particularly a suspected blackmailer. He remains firmly in charge throughout, pursuing the case with impressive diligence and total absorption; though his superior powers of ratiocination are largely by dint of effort. In these qualities, Devenish perhaps resembles Freeman Wills Crofts’ famous series detective, Inspector French. He does not have any of the eccentricities which Loder bestows on some of his other police detectives: for example the likeable Superintendent Cobham in Whose Hand? (1929), who deliberately lulls suspects into a false sense of security by pretending to be an absent-minded blunderer (similar to the TV detective Columbo), and who often hums while investigating, alternating between opera arias and music hall tunes. Loder describes Devenish as ‘tall and thin, dark hair, dark eyes, and a swarthy complexion; he might have passed as a southern Italian’. Beyond this, we learn nothing of Devenish’s background or personal life, not even his first name. There is no amateur sleuth on hand to rival or potentially embarrass the police. Devenish works alone, assisted by Detective-Sergeant Davis and reports to Mr Melis, an Assistant-Commissioner. Melis is debonair, suave and ethereal, with the air of an amateur actor. But his ideas on the case often turn out to be perceptive and seminal, providing the germ from which Devenish produces workable theories.

The denouement is surprising, and not easily foreseen. But it is plausible and makes sense, even though partly speculative. It shows the plot to have been solidly clued for the reader who can follow the hints. Loder often shows villains falling prey to their own scheming and he does so again here. There is also a pervading sense of tragedy, almost tragi-comedy, affecting those directly involved. One of the killings involves a variation of a method of dispatch seen in other Loder novels. The other foreshadows the murder setting in Drop to his Death (1939), co-authored by John Dickson Carr (writing as Carter Dickson) and John Rhode.

The Shop Window Murders is an entertaining and richly plotted example of the Golden Age deductive puzzle novel. The unusual and bizarre crimes make it one of Vernon Loder’s best mysteries for bafflement and ingenuity. The narrative is direct, brisk and lively, and the complex storyline is absorbing, well-constructed and moves at a swift pace. Loder pays close attention to carefully worked-out and intricately structured plotting. But his skill in creating clever, insightful ‘good lightning sketches’ of characters, a feat praised by Dorothy L. Sayers in her review of Murder from Three Angles (1934), is also evident—Melis being a good example. The combination of subtle witty observations and good humour help to leaven an otherwise dark tale. Here is Loder describing Mander’s older female admirer: ‘She did not look an amorous type, though she was obviously endeavouring to hold her fugitive youth by the skirts’. Overall, the novel shows Loder writing with assurance and maturity as a crime fiction author.

Of particular interest to Golden Age aficionados will be the striking similarities between The Shop Window Murders and The French Powder Mystery by Ellery Queen, also published in the US and UK in 1930. It was only the second Ellery Queen Mystery, a year after the successful debut of The Roman Hat Mystery. The book begins almost immediately with a murder: a model inside the main shopfront window of French’s Department Store in downtown New York City is demonstrating some modern furniture and accessories on display, with a crowd watching from outside. When a button is pushed to reveal a concealed wall folding bed, out tumbles the murdered body of the wife of the store owner. The similarities continue: the owner has a private apartment above the store which the victim visits late one night when the store is closed. There are bizarre and unexplained clues, strange discoveries of unusual items found where they should not be, and a plethora of alibis and motives. The plot is ingenious, almost to the point of being overly complicated and involuted. Each small fact and clue is examined, discussed and (mostly) discarded with impressive deductive logic and reasoning. The rigorous intellectual approach is indebted to the popular Philo Vance mysteries of S. S. Van Dine. The climax is generously praised by the eminent critic Anthony Boucher as ‘probably the most admirably constructed denouement in the history of the detective story’. Following the trademark Queen ‘challenge to the reader’, it comprises 35 pages of tightly worded explanation, with the identity of the murderer only revealed in the last two words of the novel. Ellery Queen was the nom-de-plume of Fred Dannay and Manfred Lee, two cousins from Brooklyn. According to their biographer Francis M. Nevins, the novel was inspired after one of the cousins passed a Manhattan department store display window and stopped to look at an exhibit of contemporary apartment furnishings which included a Murphy bed. It is not possible to say whether Loder or Queen first conceived the idea of the store window murder, but the similarities between the two stories and close proximity of publication dates are certainly a remarkable coincidence.

Vernon Loder was one of several pseudonyms used by the hugely versatile and productive Anglo-Irish author Jack Vahey (John George Hazlette Vahey), 1881–1938. In addition to the canon of Loder titles between 1928 and 1938, Vahey wrote initially as John Haslette from 1909 to 1916, resuming writing in the 1920s as Anthony Lang, George Varney, John Mowbray, Walter Proudfoot and Henrietta Clandon. Born in Belfast, John Vahey was educated in Ulster and for a while in Hanover, Germany. He began his working life as an architect’s pupil, but after four years switched careers and sat professional examinations with a view to becoming a chartered accountant. However, this too was abandoned after Vahey took up writing fiction. He married Gertrude Crewe and settled in the English south coast town of Bournemouth. His writing career was cut short by his death at the relatively young age of 57.

The Loder novels were all published by Collins in the UK, and from 1930 his detective works were published under their famous Crime Club imprint. Several of his early novels (between 1929 and 1931) were also published in the US by Morrow, sometimes with different titles. The publisher’s biographical note on Loder, which appears in Two Dead (1934), mentions that his initial attempt at writing a novel (apparently never published) was during a period of convalescence in bed. Various colourful claims are made of Loder: he once wrote a novel on a boarding-house table in twenty days, serialised in both England and the US under different names; he worked very quickly, and thought two hours in the morning quite enough for anyone; also, he composed directly on a typewriter, and did not ever re-write. Whether these claims are true—or indeed laudable—is a matter for conjecture.

Loder had several recurring detectives. Inspector Brews and Chief Inspector Chace were each quite contrasting characters, the former a stolid local policeman with an emphasis on the importance of routine, the latter a highly efficient new breed of Scotland Yard CID detective. Brews appears in The Essex Murders (1930) and Death of an Editor (1931); Chace is found in Murder from Three Angles (1934) and Death at the Horse Show (1935). In his later espionage thrillers—Ship of Secrets (1936), The Men with the Double Faces (1937) and The Wolf in the Fold (1938), published under the separate Collins Mystery imprint—Loder’s protagonist was Donald Cairn, a British secret service agent involved in a series of thrilling adventures combatting continental spies in the lead-up to the outbreak of World War 2.

Loder never quite achieved the first rank of detective novelists, and has received scant attention in commentaries of the genre. Nonetheless, he was a popular, dependable author in the 1930s, and better than many; perhaps a paradigm of the English Golden Age mystery writer. The original Collins dust wrappers show that he was warmly reviewed: ‘The name of Mr Loder must be widely known as a reliable and promising indication on the cover of a detective story’ (Times Literary Supplement); ‘Successive books by Vernon Loder confirm the impression gathered by this reviewer that we have no better writer of thrill mystery in England’ (Sunday Mercury); ‘… just the effortless telling of a good story and meticulous observation of the rules’ (Torquemada in the Observer). And in 2014, J. F. Norris wrote: ‘… keep your eyes out for any book with the Vernon Loder pseudonym on the cover. They make for fascinating reading and are as different from the standard whodunits of his colleagues as champagne is to soda water.’

Since the 1930s Loder has remained out of print, and his works have largely been the purview of Golden Age book collectors, among whom he has a following, with scarce first editions commanding high prices. This welcome re-issue of The Shop Window Murders and earlier The Mystery at Stowe, should help Loder, deservedly, to be rediscovered and enjoyed by a new wider readership.

NIGEL MOSS

March 2018

CHAPTER I (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

MR TOBIAS MANDER’S new stores in Gaffikin Street had been a public wonder from start to finish. From the moment that this almost unknown man from the west country had visualised the idea of a store that would beat all other stores for cheapness combined with luxury, a highly-paid press-agent had seen to it that the country should join vicariously in the building and equipment.

The plans had been published in the front sheets of all the prominent newspapers, and every stage of the immense building progress had been reported with diagrams, portraits of the (titled) architect, and descriptions of all the eminent firms that had contributed to the material elegancies and equipment of the famous Store-to-be.

But Mr Tobias himself had remained unphotographed and unfeatured throughout the campaign, and no one from the outside world had even guessed accurately at the manner of man he was, until the Store was opened with a flourish of trumpets, and a luxurious house-warming.

To that function everyone of importance went. People who were wont privately to sneer at trade, forgot their principles, and crowded to the show; even titled actresses (notoriously exclusive) were among the throng.

When Mr Tobias Mander first burst upon the world, the world saw him as a man who might have been a prosperous stockbroker, a genial bookmaker, or a retired Smithfield merchant. He was of medium height, with a very fresh colour, and roving blue eyes; inclined to stoutness, always dressed in trousers with a very black stripe, a morning-coat and vest, with a white slip, and a monocle that never by any chance went into his eye.

The connoisseurs among the men called him a ‘cheery bounder’, but the women’s votes were mixed. Some thought him charming, if vulgar; and others vulgar if charming; while a few, who had encountered his roving blue eyes with a twinkle in them, declared themselves fascinated.

There was one detail in which he differed from most men of his kind, and that was in the fact that he lived on the premises. To call the very luxurious flat on the top floor ‘premises’ is modestly to understate facts. But undoubtedly Mr Mander had taken up his residence within the walls of the store.

One of the stunts with which he had taken London, some months after the store opened, was a new gyroplane. No one knew the inventor’s name, but there was trouble one day when it sailed over London, and landed with the greatest precision on top of the flat roof that covered the store. ‘The Mander Hopper’ it was called, yet that particular hop was frowned on by the authorities, who were not convinced that any aeroplane was quite safe among the roofs of a city. But the necessary prosecution provided further réclame for Mander and his store, and, later, those were not lacking who said they had heard aero-engines at night, and professed to believe that the great man sometimes landed after dark on his own roof.

There was no reason, beyond out-of-date regulations, why he should not have done so, for the ‘Mander Hopper’ proved to be the gyroplane for which the world had been looking, and the department which stocked and sold the ‘Plane you fold up in a room; and land in a tennis-court’ was one of the most paying in the whole Store. The ‘Hopper’ was, as one ancient pilot said, ‘The plane that put the F in safety.’

The windows of the store were enormous, and each window was changed weekly. There you did not see wax figures disposed in solitary state, but naturally disposed in a room, with an appropriate stage-setting, so to speak. And the contents of each window were announced in the Sunday papers, so that an avid public would know where to look for a novelty when the blinds were drawn up on Monday morning.

The store did not believe in a constant, all-night electric-lit display. Mr Mander, with the turn for quaint originality which had helped him so much in booming his business, explained to a reporter (and he, in turn, to a delighted world) the reason for this.

‘It’s my house, you see,’ he told the man. ‘I make it a rule to put business out of my head when business is over. At night, and during the weekends, the Store is my Store only in name, and you do not pull up the blinds, and keep the light on, in private houses during the night.’

During the first week in November, the Sunday papers had spoken of the season of fancy-dress, and the writers had artfully proceeded from the general to the particular, and mentioned that the principal window in the chief bay of Mander’s Store would ‘feature’ the next day a marvellous selection of fancy dresses, carried out by British workers, in British materials, by British designers.

There are always in London, at any hour of the day or night, sufficient people with no visible occupation, and an intense curiosity about anything novel, to form a crowd on the pavement. At five minutes to nine, there was a line of spectators three deep before Mander’s Stores, which was continuously being added to by fresh arrivals. Many of them, it is true, were not of the class likely to wear fancy-dress, but all kept intent eyes fastened on the immense blinds that cloaked the splendours within from view.

At nine precisely, a man inside set in motion the mechanism which raised the blinds, and there was the instant ‘Oo-er!’ of vulgar appreciation, mingled with the more polite enthusiasm of the cultivated.

The floor-space inside the window was dressed as a ball-room, even to a waxen band that sat in a recess at the back. The moment portrayed was a pause between dances, and at least forty couples in the most novel costumes stood about the floor, or leaned against the walls in dégagé attitudes that were almost lifelike.

But there was an exception to the rule, and, while most of the crowd outside were in ecstasies over the originality displayed, it was left to a commoner, a little bricklayer with ginger hair, on the outskirts, to discover it.

‘Lumme!’ he said contemptuously. ‘Mebbe it’s a novelty for the likes of ’im to work, but t’ain’t what I would call novel!’

‘It’s supposed to be a motor-mechanic,’ said someone next to him.

‘Wat if it is?’ he demanded firmly. ‘Moty mechanics isn’t novel!’

The figure in blue overalls to which he referred at once drew every eye. It was not elegant or elegantly disposed, as were the others in that window. And there was something else about it that provoked a sudden shriek, and a flop, from someone in the crowd.

Most of the spectators now concentrated on giving the fainting one as little air as possible. The few who remained at the window gasped and stared, or shivered. For there is a difference between even the best wax model and the appearance of a dead man beside it.

While they shuddered and debated, the bricklayer darted across the road to a policeman and spoke to him energetically. Then, with the policeman at his heels, he hurried in through the principal door of the great stores. Someone in the meantime had removed the public nuisance, who had fainted, and the rest of the crowd surged back to see the horror.

By the time a few more people had fainted and been duly removed, those next the window saw a door panel open at the back, and the blue-coated policeman pass through it. He was followed into the ‘ballroom’ by an alarmed shopwalker, and, when they had passed through, the supererogatory figure of the bricklayer was framed in the doorway.

There was a hush outside as the constable advanced to the figure in blue overalls, reached out a long arm, and gripped its shoulder. There was a scream as the figure overbalanced and fell down, while the mask came off, and where it had been there was disclosed a face that was quite white, but had no other visible relation to wax, and bore a striking likeness to that of Mr Tobias Mander.

Then the shopwalker turned and bellowed something, and, like the safety curtain at a fire in a theatre, the blinds came down with a rush, and blotted out every trace of the tragedy from the public view.

The constable was one of those very superior policemen who have joined up since the war. He recognised Mr Mander, and he recognised the nature of the wound which had put an end to that consummate commercial impresario. He unbuttoned part of the blue overalls.

‘Gunshot wound,’ he said slowly. ‘Let’s have some more of those electrics on, and get to the telephone, and ring up our people quick as you can—Mr Mander, isn’t it?’

‘It is,’ said the horror stricken shopwalker, who looked as if he were going to be sick. ‘It’s murder, that’s what it is!’

‘Maybe,’ said the constable. ‘Now get your manager, and send for our people. They’ll bring a surgeon with them.’

The shopwalker rushed for the door at the back, ejected the bricklayer from it, and closed the panel behind him. The constable, left alone in that scene of empty and now tragic grandeur, let his eyes wander round the ballroom, and suddenly brought them to rest on something that lay on the floor beside one couple of static dancers. He looked at that first searchingly, and then at a figure of a young woman, who sat huddled back in an empire chair, just concealed from the general front view by the dancers at rest already mentioned.

The young woman’s figure wore a balloonish skirt, covered with what looked like painted diagrams of the ‘Mander Hopper’. She wore over that a loose circular cloak which had something about it suggestive of a red parachute. On her head was fixed what looked like an aeroplane propeller with red silk trimmings, and over her face a black crepe mask, while her right hand wore a kid glove.

Taking the utmost precaution to disturb as little as possible, the constable walked over to the first object, and bent down to look at it. It was a Mauser automatic pistol. From it he approached the figure of the young woman. He looked at it hard. Then he extended his index finger, and gravely pressed it against the figure’s shoulder. With that he started, bit his lip, and seemed uncertain what to do. Finally he went back to stand by the sliding panel which formed the door to the ‘set’, and waited there for someone to come.

The manager of the store, Mr Robert Kephim, a smart man of middle-age with a very stolid cast of countenance, suddenly entered. He looked at the constable.

‘Mr Hay tells me there is something suspicious here, constable,’ he said. ‘I—’

And then he stopped, and looked very uncomfortable and unhappy. He was not the type of man to feel sick or faint, but the sight of his employer lying on his back there gave him a dreadful jolt.

‘Do you recognise him, sir?’ asked the constable.

Mr Kephim swore, then he nodded. ‘Why, what has happened? That is Mr Mander—I can’t understand it.’

The constable thought that a mild remark. ‘I think the gentleman has been shot,’ he said, ‘and I shouldn’t be surprised if there isn’t another one gone west too.’

Now Mr Kephim did really go pale, and made incoherent noises in his throat.

‘That young woman in the chair over there looks too natural to be true,’ went on the constable, ‘and there is a pistol on the floor. But we must wait till they send the inspector round before we have a look at that.’

Mr Kephim switched his eyes unwillingly to the woman in the chair. His eyes went from her head to her feet, and there remained, while they appeared to grow rounder and more glaring, and his body trembled to such a degree that the constable gripped him in a friendly way to lend him support.

‘Now then, sir, steady!’ he said.

‘The shoes—her shoes, said Kephim thickly. ‘But it can’t be—it can’t!’

A curious look came into the constable’s face. He stared at the man beside him, and put a sharp question.

‘Whose shoes, sir?’

Kephim gulped. ‘It must be a mistake. Of course it is. They aren’t really uncommon—they must sell hundreds of them.’

‘Very good, sir, but perhaps you would like to tell me to whom you are referring?’

Kephim shook his head. ‘Not just now. I may later. But I don’t think it will be necessary. How soon do you think your people can be here?’

‘As they are just round the corner, they may be here any minute,’ said the constable, and went over to look at the shoes in question.

They were not evening shoes, but walking-shoes of brown leather, with a strap decorated with a serpent whose eyes were the buttons. He was still looking when the panel slid back.

Inspector Devenish, who had just come in, accompanied by a detective-sergeant and the police-surgeon, was tall and thin. He had dark hair, dark eyes, and a swarthy complexion, and might have passed as a southern Italian. Leaving the sergeant to close the panel behind them, he approached the constable, after a dry glance at the white-faced and trembling Mr Kephim.

‘What’s up here?’ he asked the constable, who saluted.

‘Looks like murder and suicide, sir,’ said the policeman.

He pointed out the body of Mr Mander, and then indicated the sitting figure of the young woman. Inspector Devenish bent over the body of the dead man, examined it cursorily, and then left it to the surgeon.

‘Now let’s see the other,’ he remarked to the constable, quite well aware that Mr Kephim had not concerned himself at all with Mr Tobias on the floor, but had continued to stare at the figure in the chair.

Devenish went over, and gently drew off the circular cloak and the mask from the huddled figure of the young woman. Then a thud behind him made him turn quickly. Mr Kephim had fainted, and fallen.

CHAPTER II (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

A SMALL army of officials had taken charge of the ballroom in the main bay of Mander’s Stores. There were many detective officers of various ranks, and two photographers. Leaving them to their routine work, Inspector Devenish had gone upstairs in the lift to Mr Mander’s flat, in the company of Mr Mander’s chief of staff.

Kephim still looked ill, but he was more composed now, and as they entered the lift, he was explaining in a low voice the arrangements his late employer had made to ensure privacy for his own apartments, and his comings and goings out of business hours.

‘He had a private door, and staircase at the back, inspector,’ he said; ‘there was a landing that gave access to a door in the hall of his flat. Then this lift takes you to another door, also opening in his hall, though at another side.’

By this time the lift had taken them to the top-floor, and they got out. Devenish stared at the door before him, then swept the floor with a swift glance.

‘I see. Now if we take it that Mr Mander did not descend into the shop during the weekend, was there any other means than this lift by which he could have been taken down?’

‘But he must have gone down,’ said Kephim, biting his lip. ‘The pistol down there—’

‘I know,’ said the other impatiently, ‘but were there other ways?’

Mr Kephim hesitated for a moment before he replied. ‘Yes, there are, of course, more than a dozen lifts used for parcels and goods from the store-rooms that are on this floor. But Mr Mander’s flat is cut off from that section by an unbroken wall.’

Devenish nodded, and rang the bell of the flat. In a minute the door was opened by a man-servant, a stout and dignified fellow of about fifty. Mr Kephim hastily explained the matter to the man, who looked as upset and frightened as any experienced man-servant can do, and hurriedly voiced his horror and regret.

Devenish nodded. ‘Very natural. Now take us to your master’s drawing-room, please. I shall interview you later, and also the other servants. How many are there?’

‘There’s Hames the footman, sir, Mr Mander’s valet, cook, two housemaids and a parlour-maid.’

‘It’s a large flat then?’

‘Yes, sir. There are ten rooms, and our rooms.’

‘The servants’ quarters are also quite cut off from Mr Mander’s part of the flat,’ explained Kephim.

‘Quite?’

‘I mean except for one communicating door, inspector.’

‘Very well. When I ring, I shall want to interrogate the staff one at a time.’

‘I understand, sir,’ said the butler, intelligently showing them into a vast and expensively furnished drawing-room, and left, closing the door gently behind him.

Devenish sat down, and motioned his companion to a chair.

Kephim sat down, biting his lip, and obviously very ill at ease. The inspector did not add to his embarrassment by staring at him, but surveyed the drawing-room from end to end as he put his first question.

‘Now, Mr Kephim, you saw what happened below. Mr Mander died from a shot-wound that entered the groin. The young woman had been stabbed in the back, with some thin-bladed, pointed weapon. Perhaps you will explain to me the reason why the discovery of the woman’s body proved a much greater shock to you than that of Mr Mander?’

Kephim’s eyes filled with tears. ‘I—we—were engaged to be married,’ he said in a very low voice. ‘A week ago,’ he added.

Devenish looked sympathetic. ‘I am sorry. That is indeed a tragic thing for you. Take your time, sir, and try, if you can, to let me hear a little about her. I won’t keep you any longer than I can help.’

Kephim pulled himself together with a visible effort. ‘Her name is—was Effie Tumour, inspector,’ he said. ‘She came here from Soutar’s, where she was second-buyer in the millinery. Mr Mander made her chief-buyer.’

Devenish had heard of Mander’s methods, and nodded. ‘Promotion, of course. I suppose he did not know her prior to making her this offer?’

‘I am sure he didn’t, inspector. She would have told me. I have known her for three years.’

‘She seems to have been a very handsome girl,’ said Devenish, looking at him thoughtfully.

Kephim coloured, and looked slightly indignant. ‘She wasn’t that kind of girl, and Mr Mander wasn’t that kind of man,’ he snapped. ‘Mr Mander was mad about aeroplanes. He has a kind of laboratory and workshop up here in the flat.’

‘I’ll have a look at that presently,’ replied the detective. ‘I am making no aspersions, remember. Only it seems rather odd that Mr Mander should have had two entrances, one from the rear.’

‘Three entrances,’ said Kephim; ‘there’s the stairs down from the flat roof, where the gyroplane landed the other day.’

‘Ah, the new gyrocopter,’ said Devenish. ‘But let us get back to Miss Tumour, if you please. In spite of Mr Mander’s absorption in aeroplanes, it is pretty obvious that she must have visited Mr Mander here during the weekend.’

‘She was up the river with me yesterday,’ replied Kephim, and drew a long shuddering breath. ‘I left her at eight o’clock at her flat.’

‘Where is that?’

‘No. 22 Capperly Mansions, Pulsey Street.’

‘Thank you. You left her at eight last night. After that she must have come here.’

‘I—yes. I suppose she must.’

Devenish got up, and crossed the room to ring the bell. The butler presented himself a minute later.

‘Did you wish to see me now, sir?’ he asked.

‘Yes. Did you admit anyone to this flat after, say, a quarter-past eight last night?’

‘No one whatever, sir. I am sure of that. Mr Mander had been at Gelover Manor, his country place, during the day. He came in at half-past seven, and dined at eight. He was alone, sir, and had no visitors that I know of last night. I never come in here after ten, unless I have special instructions.’

‘But you heard nothing during the evening, nothing during the night? Nothing out of the common I mean?’

The butler reflected. ‘Unless you mean that engine kind of noise, sir, I didn’t. But then this part is sound-proof from our part.’

‘What do you mean by the engine sound?’

‘Well, it was just like the noise that gyro thing made, sir; when it dropped on the roof, and there was so much fuss about it.’

Devenish nodded. Kephim stared.

The butler went on. ‘Do you want to see the rest of the staff now, sir? I may tell you, that when I lock the communicating door from our part at night, I keep the key under my pillow.’

‘Oh, you lock it from your side?’

‘Yes, sir, but Mr Mander generally shoots the bolts on his side as well.’

‘Awkward, if he lies late?’

‘Well, no, sir. He had a button by his bed, and if he presses it, a mechanic withdraws the bolts.’

‘Thank you. That will do. I’ll send my sergeant up presently to interview the staff.’

When the butler had gone once more, Devenish looked at Kephim. ‘I wonder, sir, if you are the gentleman who figures so well at Bisley every year?’

Kephim’s jaw dropped a little. ‘I am fond of rifle shooting; yes.’

‘I thought so, sir. Your name is not a common one. But now we’ll go through the flat, and end up on the roof.’

‘Do you believe anyone could have landed on the roof last night?’ Kephim demanded quickly, as he rose.

‘It seems to be a possible thing,’ said Devenish.

With Kephim looking on, he made a rapid but careful survey of the big drawing-room, then passed on to a dining-room that opened out of it. There was nothing in either to suggest a crime, or to hint that a woman had visited it lately. From there they entered the billiard-room, and a study. But Devenish did not linger long at any particular spot. His assistants, when they had finished below, would make a minute search, and photograph whatever was necessary for the exposure of finger-prints.

Then they visited four bedrooms, and ended up in a room, with two windows facing to the rear of the Store, one of which was fitted up as a workshop, and the other as a sort of store for metal and spare parts. In the workshop proper, there was a lathe, two benches, various band-saws for cutting metal, and an aero-engine of a rather unusual kind.

‘Is it possible that the engine noise the butler heard was made by one of these saws, or the lathe running?’ asked the detective.

‘I don’t think so,’ replied Kephim. ‘There are dynamos, I think they call them, in the basement. Mr Mander used power from them to work his machines here, but you wouldn’t hear them so far up.’

Devenish looked at a large switch-plate on the wall, ‘I suppose not. But what about this engine. It seems as if it had been strapped—fastened down for a bench test. It may have been that the butler heard.’

Kephim approached. ‘I don’t think so. Look here—there are three sparking-plugs missing. I know a little about cars, if not about aeroplanes.’

The inspector agreed. ‘Couldn’t fire without those, of course. Well, my people will go over this presently, and I think we had better have a look at the roof.’

A stairway led from the flat to the roof, the door let in to the panelling. It was unlocked, and Devenish put his handkerchief over the handle and turned it gently. Then he prepared to mount the stairs.

‘Seems to be the only way up,’ he remarked. ‘Anyone else wanting to get there would have to land from the sky.’

The flat roof of the Stores was a hundred and twenty yards long by fifty wide. It was covered with a rough-surfaced material, to enable an aeroplane to draw up more easily on landing, and, about thirty feet from the parapet at either end, there were banks of sand about two feet high, that had the appearance of emergency buffers.

‘By the way, Mr Kephim,’ said the inspector, as they walked slowly across the roof, ‘November is rather an off month for the river.’

Kephim looked at him resentfully. ‘I did not say we went boating. I meant up the Thames valley in my car. You can check that, I think.’

But Devenish seemed suddenly to have forgotten the point. He looked down at the roof, and raised his eyebrows.

‘Speaking as a layman, those look to me remarkable like the tracks of an aeroplane, which took off from a rather clayey field,’ he said.

Kephim stared at the tracks indicated. ‘That is odd. We have, as you know, had wonderfully dry weather for the past fortnight.’

Devenish went down on his knees, and carefully collected some of the dry clay with the blade of his pen-knife. When he had collected enough he put it in a little box he took from his pocket.

‘It will be interesting to know when that was deposited here,’ he said. ‘I think we shall go down to the workroom again.’

They descended, locked the door behind them this time, for the key was still in the lock, and visited the other room where were the stores of metal and spare aeroplane parts.

‘Ah, here we are,’ said Devenish, going to a large table in a corner, and pointing to two rubber-tyred wheels that lay there, ‘I take it that these belong to a gyrocopter, and we shall be able later to compare their tracks with those above. I shall have the whole of Mr Mander’s part of the flat locked up. No one must enter until we have given permission.’

‘I shall see to it,’ said Kephim. ‘We shall probably pay off his servants, later on, and close the flat.’

Devenish led the way out, locked the door of those two rooms, and put the keys in his pockets. He went back to the drawing-room, and now Kephim was beginning to show signs of restlessness.

‘Well, sir, I suppose, since you are here, you can tell me what your movements were from eight last night until you arrived this morning in your office?’ said the inspector.

Kephim sat down gloomily. ‘That’s an awkward question to answer,’ he said abruptly.

‘I am afraid I must ask it, sir,’ said Devenish calmly.

Kephim bit his lip. ‘I left Miss Tumour, and had supper at my flat in Baker Street—I have dinner in middle day on Sundays. I read a book until ten, and then sat and smoked, and tried to work out a crossword puzzle till eleven.’

‘And after that, sir?’

‘Well, that is the annoying part. I didn’t feel sleepy, so I went out at about a quarter-past eleven, and walked up to Regent’s Park. Mr Mander was a great man for novelties, and he had asked me to try to think of a novel advertising campaign. I always find my brain works best in the open air. At any rate, I did not get back till about two. I let myself in, and went to bed. My trouble is that I am afraid I did not see anyone who could identify me. I suppose that is what I should have had?’

‘It would seem better,’ Devenish replied mildly, ‘but think again, sir. Surely there was a policeman? They are more or less trained observers, and notice people at night. Or there might be lovers somewhere about. Take your time, sir.’

‘I saw various people, but no policeman,’ said Kephim, ‘but I did not see anyone look at me, and I was not always under a lamp.’

‘A policeman in the shadows may have seen you, sir. They do sometimes see without being seen. I’ll make inquiries, if you give me a sketch of your route.’

Kephim repeated from memory what he thought had been his route. He looked weary and dejected now, and Devenish was about to dismiss him, when someone rang the bell of the flat, and on opening it they saw the detective-sergeant who had accompanied Devenish to the Stores.

‘I beg your pardon, sir, but something rather important has been discovered,’ he said. ‘It’s one of the goods lifts. Seems to have traces of the murder.’

Kephim started. The inspector nodded. ‘We can’t apparently get to it from this floor, and I don’t want to examine it below. Have it sent up to the floor below this. Now Mr Kephim, how do we get to the floor below?’

‘We take this lift, inspector. One floor down, we can get along a passage to the goods-lift landing.’

They got into the lift together. The sergeant let them out at the next stop, and then descended in the lift to carry out his instructions.

The inspector was in plain-clothes, and no one took any particular notice of him as he walked at the manager’s side.

As they turned into the corridor, running parallel with the back of the building, and clear of the selling departments, Devenish turned to his companion.

‘I am sorry to speak of it again, sir, but could you tell me how Miss Tumour was dressed when she left you yesterday evening?’

Kephim was very pale, and began to tremble again, but he found voice to reply.

‘As—as we saw her just now, inspector.’

Devenish nodded. He did not say what both of them thought; that Effie Tumour might have gone almost straight from her flat to the flat above them—just waited, perhaps, for her lover to go out of sight!

CHAPTER III (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

AS they approached the lift, Devenish suddenly thought that it was sheer cruelty to take his companion with him any farther.

‘You have had a horrible morning, sir,’ he said to him, noticing how he now dragged his feet. ‘If I were you, I would go out and get some air; and have something to pull you together.’

He had already given instructions to the policemen on the various doors to follow any member of the staff who had been allowed to leave the premises, and felt quite safe in letting the manager go. Kephim thanked him weakly, and left. The detective advanced to where two subordinates stood before an open lift, in a recess at the back of the building.

One was his sergeant, who had brought it up to this floor, and he made way for Devenish, and pointed silently to a tiny spot of dry blood on the floor of the lift itself. The other man handed him a long and slender knife, the handle carefully wrapped in tissue paper, with the information that he had found it lying in the corner by the bloodstain.

Devenish examined the knife most carefully, then returned it. ‘Pack it with the other exhibits, Corbett,’ he said. ‘Where was this lift when you first saw it?’

‘It was down in the basement, sir.’

‘But it can be brought automatically to any floor, can’t it?—It can? Is it a very noiseless lift, or not?—Wonderfully quiet, eh?—Right. It is hard to say whether anyone was brought down in this, or simply came up in it.—Sergeant, I want to see the night watchman who patrols this section of the store. Send him here.’

The sergeant having gone off on this errand, Devenish knelt carefully on the floor inside, and fixed the exact position and dimensions of the blood-spot.

‘It seems to me a useful bit of evidence,’ he remarked, as he got up again, ‘but here is the watchman. Carry on! I am going to question him, but farther along the corridor.’

‘This is Mann, the night watchman, sir,’ said the sergeant.

Devenish nodded to the respectably dressed man of forty who had come up, noted that he looked like an ex-soldier, and motioned him to move a yard down the corridor.

‘Now, sergeant, I have a few jobs for you,’ he said. ‘First you must see the assistant-manager, and he must telephone to a director, if needs be, to have the Store closed. We can’t carry on with people trampling over the place; and if it remains open any longer, we shall have a drive of pressmen harrying us.’

‘But what of the assistants, sir?’ asked the sergeant.

‘My dear fellow, we can’t interrogate thirteen hundred odd men and women today. It doesn’t look like a job that one of them would do either. We must keep those in executive positions for the moment, but get the rest away, and the place closed.’

‘I’ll see to it, sir. Anything else?’

‘You must visit Mr Kephim’s flat in Baker Street, and Miss Tumour’s—I’ll give you both addresses. Find out all you can, and particularly when Miss Tumour left home last night. Also discover at what hour Mr Kephim went out and returned.’

‘Very well, sir.’

When the sergeant had gone, Devenish walked over to the waiting witness. ‘What exactly is your usual round when you patrol this section of the stores at night, Mann?’ he asked, while the ex-soldier kept a steady eye on his face.

‘I come on my shift at ten, sir,’ was the reply. ‘I walk round once, and see that it is all O.K. I have a box to sit in between rounds. They’re every hour, sir.’

‘How long does it take you to get round?’

‘Fifteen minutes. That is as I do it now, sir. But then I have only been here two months, and never seen anything suspicious.’

‘Then I may assume that you set out on your rounds at a quarter-past ten, a quarter-past eleven, a quarter-past—’

‘No, sir, it is an hour after finishing each round. I start the second round at a quarter-past eleven, and have it done by half-past eleven. I set out on the third at half-past twelve, and so on, sir.’

‘You are an ex-soldier, Mann—what branch?’

‘Finished as a sergeant, sir. I was an old regular, discharged unfit 1924.’

‘A man of method apparently, anyway,’ said Devenish. ‘Now, did you see or hear anything suspicious last night in the Store?’

He took out his note-book as he spoke.

‘Nothing at all, sir.’

‘No noise like a lift going up or down, no sound that might suggest an aeroplane engine?’

‘I didn’t hear any lift, sir, but then they are uncommon quiet. I did hear a faint sound like an engine up above, but I often hear that weekends, so I don’t count it suspicious.’

‘The dynamos in the basement were running? Why don’t these people take current from the mains?’

‘I don’t know anything about it, sir. I do know Mr Mander used to tinker with machines up above. I thought he was at it again last night; though it didn’t last long.’

Devenish nodded. ‘Let me see where this box of yours is, Mann,’ he said, and called softly to the detective at work in the lift, ‘I say, Corbett, run that lift up and down a bit for the next three minutes, will you, while I am away.’

Receiving an assent from his subordinate, he accompanied the watchman along the corridor, and down another at right angles, which ended in a sort of cabinet. This cabinet contained a seat, a switchboard and telephone, and the bell of a burglar-alarm. Devenish seated himself in the chair, and looked down the corridor. ‘You don’t see much of the Store from here,’ he remarked thoughtfully; ‘only a corner of it.’

‘So I’m not seen, either,’ replied his companion. ‘If I put on my torch, I might frighten any thieves, and if I keep the place dark I can’t see. But, dark or light, I can hear better than anyone else.’

Devenish smiled dryly. ‘You must have very acute hearing indeed, if you can hear slight sounds in a place as big as this, with partitions to cut sounds off or blur them.’

‘It isn’t that my ears are specially good, but this ear here, sir,’ said the man, with a quiet smile, and pointed to a tiny horn, like a gramophone-horn, at the level of his head, which projected slightly from the wall of the cabinet. ‘Mr Mander was great for the latest dodges. I just switch on this microphone here, and every sound comes my way. More than that, sir. There’s a kind of selective attachment to it, and it tells me from what quarter the sound comes, so I can take action.’

‘Royal Engineer?’ asked the detective gently.

‘Signals, sir. But you see what I mean.’

‘Turn on the switch now.’

Mann obeyed, then looked puzzled. The detective did not look so puzzled, but faintly startled.

‘Someone’s been monkeying with your buzz-saw,’ he murmured. ‘I don’t hear any of the noises magnified now.’

Mann had obviously some mechanical knowledge. He examined the horn and the switch, then looked at the electrical connections, and swore.

‘Cut a lead here, sir,’ he said.

Devenish took out his magnifier, and examined the thing closely, then he dusted the panelling in the region of the lead, and scanned it for finger-prints. None showed. Someone had interfered with the microphone, but he had left no traces while doing it.’

‘He must have been here while you went on one of your rounds. Did you not notice that there were no sounds coming through as loud as you would expect to hear them?’

‘I didn’t, sir, but you know how it is. I didn’t suspect anyone was here, and you aren’t so sharp after nothing has happened for two months on end.’

‘An unfortunate but truly human failing,’ agreed Devenish, ‘but I must admit to defects myself. For example, I have not been listening for the sound of the lift going up and down. I must get my man to keep it working.’

He went away, to return again in a minute, and raise a hand to command silence. It may have been the noises from the Store, but he could hear nothing of the moving of the lift, and realised that the experiment could not be made until the place was empty and perfectly quiet.

Explaining this to the watchman, he went off, and found himself in a couple of minutes in the shop window with the blind down, talking to his superintendent, who had just arrived from the Yard, and the surgeon, who sat smoking a cigarette, and watching the last efforts of the lower ranks, as they measured and surveyed and plotted the big space. When he had finished explaining what he had done, Devenish was rewarded by a nod of approval from the superintendent.

‘Any sign of the bullet yet, sir?’ he asked.

‘None at all,’ said the big man stolidly. ‘High-velocity bullet, Dr Grindley thinks.’

‘Knows,’ said the surgeon, puffing. ‘I saw enough of them during the war. Steel-jacketed, I should say.’

‘Not that Mauser?’ asked Devenish gently.

‘I ought to have been a gunner,’ said the surgeon, smiling. ‘I know all about ’em—all kinds. That Mauser is new, been fired once. But I think your experts will agree that it was fired with blank. I won’t swear, but that is my opinion.’

‘Possible,’ murmured Devenish. ‘A man who would take the trouble to set up his victims as specimens in the window here wouldn’t leave the gun on view.’

‘Was the shot fired at close quarters?’ said the superintendent.

‘I should say not. Not very close anyway.’

‘How long should you say he had been dead?’

The surgeon reflected. ‘It isn’t so easy to answer that as some people imagine. I should say roughly between twelve to fourteen hours, but I may be sadly out.’

‘And the young woman?’

‘Less, I should say, but I can’t tell you how much less. In neither case does the bleeding seem to have been extensive—a sporting bullet with a more or less soft nose would have been different. The other wound was made by a weapon that did not—’

‘Wait a moment,’ said Devenish. ‘If she was killed after him—’

‘Then he didn’t do it,’ said the surgeon. ‘I admit that! I don’t think either of them did it to each other!’

Devenish smiled faintly. ‘Well, you’ll have the P.M., and then we shall know more. I thought, superintendent, of going to see the man in charge of the aeroplane department. I see you have cleared most of the people out of the Store, but the executives will be here.’

‘I asked them to stay in Mr Mander’s private office,’ said the other. ‘I am going to have a talk to them. But if you care to see one alone—’

‘If he would come to me in his department above, sir,’ said the inspector, ‘I will go there now.’

The superintendent nodded. ‘Very well. I’ll send him.’

The inspector nodded to the surgeon, and went away. Taking one of the automatic lifts, which had upon a board outside ‘To Sporting and Aeroplane Departments’, he found himself on the first floor, and presently arrived in an immense room looking over a street at the side of the Stores building. Housed in this department (some ready for flight, and some in the various stages of folding that made the Mander Hopper such a boon to the private pilot without a hangar) were about six machines.

Devenish lit a cigarette, and walked round them thoughtfully until the sound of someone approaching told him that the manager of the department was arriving for his interview. He came in, and greeted the detective briefly. Devenish saw that he was an alert and handsome young man of about thirty, rather of a military cut, and obviously intelligent.

‘I was up on the roof just now, sir,’ the detective told him. ‘There were tracks that made me rather wonder if a machine had landed there lately.’

‘This is a pretty filthy business, inspector,’ said Mr Cane in reply. ‘Hardly bargained for a Wild-West shooting here. But what was that you said? A machine landed on the roof? Most unlikely, I should say. We had enough of that sort of thing a month ago.’

‘A certain amount of trouble, but also a good deal of advertisement, sir! I should like to have a list of purchasers of the “Mander Hopper”.

‘The first purchasers. But suppose they had been resold?’

‘No doubt we could trace them, said Devenish, offering his case to the young man, who took a cigarette and lit up.

‘I suppose you could. I’ll get you a list.’

‘Are these heavy machines?’

‘Yes, they are heavier than machines would be which were not fitted with the gyrocopter device, inspector.’

Devenish approached a machine which was ready for flight. ‘The tyres on the landing wheels are naturally wider when the machine rests on them than when they are removed,’ he said.

Cane grinned. ‘That is what “Punch” would call “another glimpse of the obvious”, inspector. I might even go further, and suggest that, at the moment when a machine lands, the impact makes the track even wider than that!’

‘Quite what I thought, sir,’ replied Devenish innocently. ‘Now could we get one of the wheels to make some sort of track here?’

Cane thought it over. ‘I might chalk the treads of the two tyres, and we could push the ’bus a bit along the floor, if that is any good to you.’

‘Splendid, sir. While you are doing that, I might be looking at your books, and taking down some of the names of purchasers of these machines.’

‘Come to my office in the corner there. You’ll find pens and paper, while I get the books out of the safe.’

There had been perhaps fifty purchasers of the ‘Mander Hopper’ since it had been put on the market, or rather, there had been promise of delivery of that number of machines. Devenish took down the names and addresses, and had completed his list when Cane called to him.

‘Palaver set, inspector.’

Between them, they pushed a machine along the floor, and the inspector not only measured the whitened track made by the tyres, but also the width of the treads pressed out by the weight above.

‘That will do nicely, sir,’ he said when he had finished. ‘Now I want to ask you a question about Mr Mander. He was interested in machines and aerodynamics, wasn’t he? I saw some sort of a laboratory, or workshop, above.’

Cane laughed a little. ‘He did tinker a bit, I believe; but I really know nothing about it. He said he always gave full charge of a department to a man, and never interfered.’

‘But who invented the machine here that is called by his name?’

‘It is assumed that he did.’

‘Well, didn’t he?’

‘Can’t say. He patented it, I know. I was only once up in his workshop, and he didn’t like that much. What I saw there of the jobs he did struck me as elementary. A fellow who invented this had to be a swell at other things than mechanics.’

Devenish’s eyes lit up. ‘You mean that he did not seem to you capable enough?’

Cane nodded. ‘I mean that, when I had to talk to customers once or twice before him, he never said a word. Can you imagine any chap who could invent a perfect gyrocopter standing mum while you were fiddling with his subject? I can’t! I know inventors. Perfect pests, poor devils, and ready to jaw your head off! That is about the only satisfaction they get out of their inventions.’

‘But someone must have invented it?’

‘Obvious again. But isn’t there just a hint that the man who did might have been on his uppers, and beam-ends, and so on, and been told he could get a purchaser if he kept his mouth shut?’

‘Ah!’ said Devenish heavily.

Then he thanked Cane for his help, and left him to go on the roof again, where he made fresh measurements and comparisons, emerging half an hour later, and going towards the lift, when he met a man he had not seen before, a pompous stout man, with a bald head, who introduced himself as the assistant-manager.

‘The Stores are now completely cleared, inspector,’ he informed Devenish. ‘Is there any way in which I can help you?’

The detective reflected, then: ‘Is this a private company?’ he asked.

‘No. Mr Mander was the sole proprietor.’

‘Really. But this is a very big organisation. Do you mean that he financed it himself?’

‘So far as I know. I can’t say.’

The interview got no further than that, for a constable came hurrying up to say that Mr Melis, an Assistant-Commissioner from the Yard, was in Mr Mander’s private office, and wished to see the inspector.

CHAPTER IV (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

THE staff had been turned out of Mr Mander’s room, and Mr Melis sat there in state, a cigarette between his long fingers, and his brown, humorous eyes fixed on Inspector Devenish’s face.

‘Doesn’t seem anything very tangible to take hold of so far, inspector,’ he was murmuring in an agreeable voice, ‘unless it is this business of the gyrocopter.’

‘What interests me more, sir,’ replied Devenish, ‘is the person who financed Mr Mander. I can’t make that out. He seems to have sprung up suddenly from nowhere, and even if he was a genius at this sort of thing, where did he get the money?’

‘Ah, that,’ said the assistant-commissioner, laying down his cigarette and smiling very faintly at some thought, ‘that is not so difficult as it looks. But being simple—at least I think it is, if gossip counts for anything—it does not interest me.’

‘Then you know, sir, who was behind him?’

‘I don’t exactly know, inspector; but one picks up things as one moves about; doesn’t exactly know if they are authentic, you see, but wonders if they may not be.’

‘Then, sir, if I may ask, who do you think, or wonder, may have been behind here?’

Mr Melis began to toy with his cigarette again. ‘Frankly, Dame Rumour hints that Mrs Peden-Hythe was the goddess from the machine. She was the widow of that fellow, you know, who had the shipping company in Buenos Ayres.’

‘About forty-three, and rather handsome,’ said Devenish. ‘I have seen her photographs in the society papers. But why pick on Mander, sir?’

Melis shrugged. ‘Mander was managing-clerk to the country solicitors at Volbury, where her place, Parston Court, is. Fancy is an errant thing, inspector.’

‘So it is, sir,’ replied Devenish. ‘That does put another face on it. But you spoke of the gyrocopter, sir, what is your view about that?’

‘Mine? I thought it was yours. The wide track and the narrow track, you know. It quite seemed to me that you regarded the idea of the machine having landed on the roof last night as more or less—shall we say—a plant?’

Devenish thought that over. ‘You see, sir, it looks like an inside job. Someone who knew Mander and the place thoroughly. But I wouldn’t bank on it all the same. Naturally, it did strike me that the gyrocopter, if it did land on the roof, would make a wider track with its wheels than the track up there. Also, a man who took so much care over the job would hardly leave muddy wheel-tracks.’

‘Since pilots who can fly gyrocopters are rare, and easily identified,’ Melis agreed, ‘the only trouble is the mud. Was that brought in?’

Devenish shrugged. ‘We must find out what kind of mud it is, and where it rained last night, if anywhere. The man would not rise out of a marsh. As a start, I shall inquire if it was wet near Mr Mander’s new country place last night.’

Melis took up the telephone on the desk before him. ‘We’ll get that from the weather people straight away.’ He gave a number, and turned again to Devenish. ‘You have an idea about those spare wheels in Mr Mander’s workshop, eh?’

‘A man could have pushed them along the roof, if he had muddied them first, and cleaned them after, sir. We must remember that, once up in Mander’s flat, the fellow could do anything without being heard or disturbed.’

Mr Melis nodded quickly, then spoke into the telephone.

‘A heavy shower for three-quarters of an hour, eh? At what time? Half-past ten? Thank you. That is all I want to know.’

He looked at the inspector. Devenish looked at him. ‘Just a faint hope?’

Devenish pursed his lips. ‘Who invented this new machine? That is what I want to know. I saw Mr Cane just now—manager of that department—he seems to think Mander’s experiments and workshop-trifling a sort of pose.’

‘Oh, does he? And why should he suggest it? Is he an expert, by any chance?’

Devenish frowned. ‘I wasn’t really thinking of him, sir, but now I do remember reading about him in the paper, when they were advertising this store at first. Well-known flying man to be in charge of aeroplane department, wasn’t it?’

‘I think it was.’

‘Inside the building, been once in Mander’s flat and workshop,’ murmured the inspector, ‘if there is any other link, I ought to look into it.’

Melis smiled. ‘I saw a fat man just lately, who was, I think, the assistant-manager. He is probably a good business man, but he struck me as soft otherwise; sort of fellow we might pump.’

‘Shall I have him in, sir?’

‘May as well.’

Devenish went out, and came back presently with the assistant-manager, Mr Crayte. The man at the desk asked him to sit down, offered him a cigarette, and smiled at him amiably.

‘I am sure you are a very busy man, Mr Crayte, but I know you will help us. We want a little brains on the civil side, and won’t keep you long. It’s just a formal matter of getting a little insight into the relations between the staff here—I mean the executive staff, really. The sooner we get the routine work over and done with, the sooner we can come to grips with the case.’

Mr Crayte was all complaisance. ‘I shall be happy to tell you what I know.’

‘Good! Then we’ll get to it. Mr Kephim now, the manager; I suppose he and the late Mr Mander were on good terms?’

Mr Craye scratched his head. ‘Oh, yes, quite. I should say very good terms. We are, on the whole, a happy family here.’

Mr Melis raised his eyebrows. ‘On the whole? Much as one can expect, I suppose. Can’t expect a dozen different men to be absolutely soul-mates, can we?’

Mr Crayte laughed. ‘But what little friction there has been was nothing to speak of; flashes of temper, no more. You understand that running a big place like this is bound to make one nervy at times.’

‘But it seems to me rather strange,’ said Melis, with his head on one side like a bright bird, ‘rather strange that one of the higher staff even should presume to exhibit temper to his—er—chief.’

Mr Crayte hastened to explain. ‘Oh, they wouldn’t dare to with Mr Mander. I meant among ourselves.’

‘May I ask the names of the antipathies?’

‘Well, it is all over now, but there was rather a scene between the manager of the shipping department and the manager of the furniture. A strictly departmental quarrel, if I may put it so.’

‘Apart from that, may we take it that the rest of the executive staff are good friends?’

‘Well, no. Friends is another thing. Outside our business relations, there may be a certain amount of hostility. I mean to say, men thrown together, as we are, don’t necessarily like each other.’

‘For example?’

Crayte looked at him cautiously, but Mr Melis’s expression was so bland and ingenuous, and his own love for gossip so keen, that he went on to amplify his statement. ‘Kephim and Cane have never hit it off. But I can understand that. Mr Kephim worked up. He has a fine salary now, and is worth it, but he worked up. I will say Mr Cane is a bit of a snob—I mean to say, he rather showed by his manner that he looked down on Mr Kephim.’

‘When, officially, he should have looked up,’ murmured Mr Melis, with a quick glance at Devenish; ‘but after all we are only here to inquire into the murder of Mr Mander. Mr Cane was not on bad terms with the deceased, was he?’

‘Oh, no. Quite the contrary. Mr Mander was rather proud of having a D.S.O. in charge there, and Cane was always pleasant with him.’

Devenish put in a question: ‘Who flew the gyrocopter that time it landed on the roof here?’

‘Who flew it? Let me see? Oh, it was the mechanic who helped Mr Mander with his experiments in the country. What was the name—Wepkin—Weffin—No, Webley. I remember the man very well, since I asked him to explain the way the thing worked, and he appeared to me appallingly stupid.’

‘Although he was able to fly this difficult type of machine?’ said the inspector.

Melis laughed. ‘My dear fellow, when I was in West Africa, I had a negro chauffeur. He was an expert driver, but a complete fool. Some very brainless people have a genius for mechanics. He turned to Crayte, and added: ‘Well, we are very much obliged to you. By the way, do either of these receivers communicate with Mr Mander’s flat above?’

‘This one,’ said Mr Crayte, raising it.

‘Would you mind asking his butler to come down here?’ said Melis. ‘Ah, thank you. Then we shan’t keep you any longer.’

Mr Crayte rang up the butler, told him to come down, and then left the room. Melis stared at Devenish.

‘Now is that a link, or isn’t it?’ he asked. ‘Departmental quarrels apart, we have Cane and Kephim the only dogs that bark and bite.’

‘I can imagine,’ said Devenish thoughtfully, ‘I can imagine that, if it wasn’t for the girl in the case, sir. A man might want to murder one fellow and put it on another he disliked, but he wouldn’t kill a girl to top up, and he couldn’t know that the other fellow hadn’t an alibi.’

‘But suppose the other fellow is Kephim?’ said Melis. ‘And Cane had means of knowing that Kephim was coming here last night. No; that is out of the question, for Kephim wouldn’t be likely to come on a flying machine, and if those marks on the roof do not denote an actual landing, they were put there to suggest that the murderer arrived by air. But, say Kephim determined to do the deed and put it on Cane. Would that go better? As you say, Kephim is a crack shot.’

‘There is still the girl,’ said Devenish. ‘Why kill his fiancée?’

Melis leaned back in his chair, lit another cigarette, and half-closed his eyes. He was a good amateur actor, and carrying that art into official life was the only thing his subordinates had against him.

‘There is a psychological side to this crime that does not seem to have occurred to you, inspector. If it has, I apologise. To put a murdered man and woman in a shop window, where they would inevitably be exposed to the public gaze, what does that suggest?’

‘Revenge; with something personal and bitter in it,’ said Devenish. ‘Not a murder for gain. I see what you mean, sir.’

Melis nodded. ‘Mander is top-dog. With him are promotions, and increased emoluments. He seems—I only say he seems—to have fascinated one wealthy woman, while he was still in a subordinate position. To a poorer woman under him, he might assume the aspect of a little god.’

Devenish bit his lip. ‘The evidence tends that way, sir, but—’

The butler knocked and came in, to apologise for his tardiness. Melis told him to sit down, then bent, picked up a despatch-box, and took from it a slender weapon, the handle covered with tissue paper, and laid it on the table.

‘I suppose there is no chance that this came from your master’s flat?’

The butler suppressed a slight shudder. ‘Excuse me, sir. May I look at it closer?’

Melis nodded, and gently exposed the handle, being careful not to touch it with his fingers. ‘Well?’

I remember it, I think,’ said the butler. ‘I do believe it was the sample Mr Winson showed him one evening at dinner.’

Melis pressed for details, and the butler gave them. A famous Birmingham manufacturer had dined at the flat one night. He and Mander had discussed a contract for a half a million ‘Eastern daggers’, to be made in Birmingham, and sold in the Oriental department for trophies, and paper-knives. The manufacturer had brought a sample with him, and laid it on the table. Mr Mander had kept it, and—

‘Then run up, and see if it is still there,’ said Melis.

‘I’ll go up with him, sir,’ said Devenish. ‘I have locked that part of the flat up. Evidently this telephone connects with the servants’—’

‘With my pantry, sir,’ said the butler, getting up.

‘Where did Mr Mander keep the dagger?’ asked the inspector, as they ascended a minute later.

‘On the ormolu table in the drawing-room, sir.’

Devenish nodded, took the keys of the flat from his pocket, and the lift stopped.

The butler led the way into the drawing-room a few moments later, crossed to the ormolu table, and gave a little cry: ‘It’s gone, sir! It was here yesterday, when I came in after lunch to see that the fire was lit.’

‘You are sure you recognise it?’ said Devenish.

‘I am sure I do, sir. I had an oppportunity to see it on the table, and I saw those curly marks on the blade, and the odd-shaped handle.’

Devenish nodded, and let the man out, telling him he could go back to his quarters. Then he relocked the flat, and went back to the assistant-commissioner.

Mr Melis raised questioning eyebrows, was told that the knife, or dagger, had indeed gone from the flat above, and rose. ‘Well, Devenish,’ he said, ‘I have an appetite for lunch, and an engagement afterwards. Come along and report this evening, will you?’

‘Yes, sir,’ the inspector replied. ‘I sent the sergeant to inquire at Miss Tumour’s flat. I think I shall go round myself, after I have had something to eat.’

‘Do!’ said Melis, with his best amateur actor’s air, picked up his gloves and hat—he never wore an overcoat—and walked out.

For some time after he had gone, Devenish sat drumming his fingers on his knee, and thinking hard. He was still at it when his sergeant came in, saluted, and approached.

‘Miss Tumour went out last night at a quarter to ten, sir,’ he told Devenish, ‘but she didn’t say where she was going, so the porter at the flats told me.’

‘And Mr Kephim?’

‘Mr Kephim, they think, left after eleven. But no one heard him come in again.’

‘Any night-porter at those flats?’

‘Yes, sir, but he did not notice Mr Kephim return. I thought it would be best to come back and tell you, without waiting to make any more inquiries.’

Devenish nodded. ‘Quite right. The times are important—one of them, anyway. I am going over myself this afternoon, so don’t trouble again. I want you to go carefully over the ground here, and make me a plan of the route which the murderer might have taken if he carried one, or both, of the bodies into the front window space from the lift.’

‘The goods-lift where the dagger was found, sir?’

‘That’s it. After you have done that, I want you to make inquiries about the night watchman. Go to Mr Crayte for the address. I don’t want the man to know. By the way, have you seen Mr Kephim anywhere in the building?’

‘No, sir. I think he did not come back.’

CHAPTER V (#u474989ed-3b48-5e19-a6a2-7d8124bf7696)

BETWEEN the Victorian shop and the twentieth century modern store there is a great gulf. It is widest perhaps in the matter of salaries paid to the higher staff. So Inspector Devenish was not much surprised to find that the late Miss Tumour occupied a rather luxurious little flat in a very nice quarter. It is true that she had only moved in there since she got the post at Mander’s.

It was to the porter that the detective first applied for information, and before he could come to grips with the problem he had to endure a small instalment of the man’s curiosity with regard to the crime. He cut that as short as he could, and asked if there was anyone in the flats who had an acquaintance with the dead woman.

‘No one, yet, sir, and aren’t likely to have now,’ said the porter, with rather mordant humour. ‘You see, sir, this was the first time they had anyone like her here. I don’t know who it was blew the gaff, but the others—’

‘I see,’ said Devenish, who knew very well that the man was referring to a certain snobbishness on the part of the other tenants. ‘So it’s no use my asking any of them about her. But you may have seen some of her visitors come in from time to time.’

‘She hadn’t many, and that’s a fact,’ said the man, ‘but one came regular lately, and another used to come with a car.’

He described the regular visitor, and Devenish recognised him as Mr Kephim.

‘Now what about the man in the car?’ he said.

The porter approached a wink. ‘I never saw him, sir. He used to come late sometimes in a closed car, and always sat back.’

‘But I should have thought you would go out to open the car door for him.’

‘It wasn’t ever necessary, sir. His chauffeur used to get out and stand in front of the door, till she came out and got in. I had always to speak up the tube to tell Miss Tumour a car had called for her.’

‘So you have no idea of the visitor’s appearance?’

‘Not a bit. He never went in neither. I’d have got into trouble if I’d gone and looked in at him.’

Devenish looked thoughtful. ‘It won’t have any bearing on the case, I am afraid,’ he said, ‘but could you tell me how long the second man has been coming?’

‘Came first a week after she had been in here, sir.’

‘Thank you. Did all her furniture come in from her former house?’

The porter blinked reflectively. ‘No, not all of it. Two lots came from Warungs ten days after she come, and then some went out to a sale room.’

‘I suppose the two visitors never came on the same day?’

‘No, they didn’t. When Miss Tumour went out with the other one she was always togged up gaudy—regular swell.’

Devenish procured the master-key and visited the flat itself after that.

In a search through Miss Tumour’s papers and correspondence, of which there was no great abundance, he found nothing in the nature of a clue. He finished up with her telephone, and took a note of the numbers in pencil on the pad. There were just five.

Getting on to the exchange, and explaining who he was, he made inquiries about the five numbers. One was Mr Kephim’s, one belonged to a Mrs Hoe in Bester Street (whom he determined to interview later), two were the numbers of her hairdresser and chiropodist respectively. The fifth number was Mr Mander’s, the number belonging to his flat telephone, and not that which would go before the switchboard operator at the store.

That in itself was not conclusive proof of any intimacy between the dead man and woman. It might be useful for her to have her employer’s number, as she held a responsible position at the Store.

Devenish looked at his watch. It was dark early at this time of year, but that did not matter. He would go down to Gelover Manor and satisfy himself with regard to the ‘Mander Hopper’ that was kept down there.