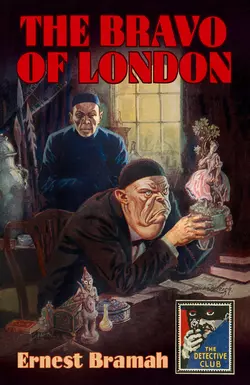

The Bravo of London: And ‘The Bunch of Violets’

Ernest Bramah

Tony Medawar

The classic crime novel featuring blind detective Max Carrados, whose popularity rivalled that of Sherlock Holmes, complete with a new introduction and an extra short story.In his dark little curio shop Julian Joolby is weaving an extravagant scheme to smash the financial machinery of the world by flooding the Oriental market with forged banknotes. But this monster of wickedness has not reckoned on Max Carrados, the suave and resourceful investigator whose visual impairment gives him heightened powers of perception that ordinary detectives overlook.Max Carrados was a blind detective whose stories by Ernest Bramah appeared from 1914 alongside Sherlock Holmes in the Strand Magazine, in which they often had top billing. Described by George Orwell as among ‘the only detective stories since Poe that are worth re-reading’, the 25 stories were collected in three hugely popular volumes, culminating in a full-length novel, The Bravo of London (1934), in which Carrados engages in a battle of wits against a fiendish plot that threatens to overthrow civilisation itself.This Detective Club classic is introduced by Tony Medawar, who investigates the impact on the genre of Bramah’s blind detective and the relative obscurity of this, the only Max Carrados novel. This edition also includes the sole uncollected short story ‘The Bunch of Violets’.As well as on the page, the Max Carrados stories have been a firm favourite on television and film, played over the years by (among others) Robert Stephens, Simon Callow and Pip Torrens, and read on audio by Arthur Darvill and Stephen Fry.

Copyright (#ue3c5f5fd-c71d-5209-8205-95fefb4474d5)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Cassell & Co. 1934

‘The Bunch of Violets’ published in The Specimen Case by Hodder & Stoughton 1924

Introduction © Tony Medawar 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Ernest Bramah asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This book is presented in its original form and may depict ethnic, racial and sexual prejudices that were commonplace at the time it was written.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008297435

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008297442

Version: 2018-07-16

Table of Contents

Cover (#u00e14f4a-2f6a-5d56-bcfc-6229d8d82f09)

Title Page (#u7f69becc-4d52-5f81-bd46-3c3eda9bbedb)

Copyright (#u0f2e99ab-6cb1-5710-bee0-58d1515c6765)

Epigraph (#ufbf1e4f0-8c4c-5397-a652-9359fd2e9b38)

Introduction (#u57180267-2c5a-5fc2-901c-a6bda823084a)

Chapter I (#ud4488976-d13b-52d3-9022-69b2e02ba6a7)

Chapter II (#u8b53a0ac-54ef-540a-8714-d138a48355a3)

Chapter III (#ua5a16add-cf73-543c-8686-b36d09826aae)

Chapter IV (#u1048c583-f208-50cb-9fa2-78d7cdec00fe)

Chapter V (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

The Bunch of Violets (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Abellino,’ said the Doge, ‘thou art a fearful, a detestable man.’

—The Bravo of Venice, Heinrich Zschokke (1771–1848)

BRAVO (1) a daring villain.

—The Oxford English Dictionary

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

INTRODUCTION (#ue3c5f5fd-c71d-5209-8205-95fefb4474d5)

Ernest Bramah Smith, born in 1868, was brought up in Lancashire, England, where he attended Manchester Grammar School. Smith did badly in his academic studies and, after leaving school in 1884, took up farming. While it was an unsuccessful experience, nearly bankrupting his father, farming gave Smith the material for his first book, English Farming, and Why I Turned It Up, which was published as by Ernest Bramah. Inspired by the book’s modest success, Smith took up journalism and secured a position working for the author Jerome K. Jerome at Today Magazine to which Smith contributed numerous short, largely humorous, pieces. He would remain a writer for the rest of his life, editing one magazine—The Minister—and contributing to many others including Chapman’s, Macmillan’s, The Storyteller, London Mercury, Everybody’s and the Windsor, as well as the prestigious title The Graphic.

In the late 1890s, not long after marrying his wife Lucy Maisie Barker at Holborn, London, Smith created the character that was to make him famous: Kai Lung, an itinerant storyteller whose tales and proverbs help him to outwit brigands and thieves in ancient China.

‘My unbecoming name is Kai, to which has been added that of Lung. By profession I am an incapable relater of imagined tales and to this end I spread my mat wherever my uplifted voice can entice together a company to listen. Should my feeble efforts be deemed worthy of reward, those who stand around may perchance contribute to my scanty store, but sometimes this is judged superfluous.’

While many modern readers would dismiss the slyly comic Kai Lung stories as literary yellowface, they were immensely popular on first publication and for many years later and, although Smith never visited China, his portrayal of the Chinese and their customs was accepted as a guide to a country about which most contemporary readers and reviewers knew very little. However, the character of Kai Lung has dated badly and Smith’s purple prose, replicating what he and others considered ‘Oriental quaintness’ and ‘the charm of Oriental courtesy’, means that his many stories of Kai Lung and other Chinese ‘characters’ are little read today.

While continuing to write about Kai Lung, Smith showed himself something of a domestic satirist with, in 1907, The Secret of the League, ‘the story of a social war’ inspired by the success of the then nascent Labour Party in the 1906 General Election. In Smith’s novel, a Labour Government is elected and, crushed by ‘the dead weight of taxation’ and other socialist ‘evils’, the middle classes rise up and, by undermining the coal industry and coal-dependent businesses, cause the Government to collapse. While it anticipates elements of Chris Mullin’s 1982 satire A Very British Coup by more than sixty years, Smith’s novel may seem offensive and naïve. Nonetheless, his predictions of the kinds of policies that a Labour Government would introduce proved in some instances to be not that far off the mark and, despite the anti-democratic tactics of Smith’s ‘Unity League’, his novel was widely praised at the time by Conservative Party politicians and their supporters at the Spectator and elsewhere.

It was in 1913 that Smith created his other great character, Max Carrados the blind detective, who first appeared in a series of stories written specially for The News of the World, a British weekly newspaper. Carrados was immediately hailed as something new and the stories about him were read avidly. He was not the first blind detective but he was the first whose other senses more than compensated for the loss of his sight, which was the result of a riding accident; Carrados therefore has much in common with Lincoln Rhyme, Jeffrey Deaver’s quadriplegic New York detective. And while Carrados and his friend, Louis Carlyle, owe something to Holmes and Watson, the detective’s closest fictional contemporary would be the preternaturally omniscient Dr John Thorndyke, the creation of Richard Austin Freeman. There are also many similarities between the characters of Carrados’s South London household and their North London equivalents in Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke stories, while more than one contemporary critic suggested that Carrados might have been inspired by the career of Edward Emmett, a blind solicitor from Burnley, Lancashire, who achieved some celebrity towards the end of the nineteenth century. If Emmett was an inspiration, Smith never acknowledged it, rebutting scepticism in later years about Carrados’s abilities ‘in the fourth dimension’ by pointing to the abilities and achievements of Helen Keller and Sir John Fielding, as well as to those of less well-known figures such as the seventeenth-century mathematician Nicholas Saunderson and the soldier and road-builder John Metcalf, better known as Blind Jack of Knaresborough.

In all, Max Carrados would appear in 26 short stories, including A Bunch of Violets, the only story about the blind detective not included in any of the three collections of Carrados short stories published in Smith’s lifetime. As well as the detective, Smith’s stories about Carrados feature some economically drawn but memorable characters: these include his amanuensis, Parkinson, who has an eidetic but erratic memory; the self-described ‘pug-ugly’ Miss Frensham, once known as ‘The Girl with the Golden Mug’; the brilliant ‘lady cryptographer’ Clifton Parker; and the detective’s school-friend Jim ‘Earwigs’ Tulloch. Moreover, the Carrados stories often feature contemporary concerns like Irish and Indian nationalist terrorism, the perils of Christian Science and the struggle for universal suffrage. Nonetheless, despite the stories’ merits, Carrados’s hyper-sensory brilliance can sometimes appear unconvincing, no more so than in ‘The Tilling Shaw Mystery’ when he is able to detect, by smell and taste, traces of whitewash on a cigarette-paper after it has been used as wadding and fired from a revolver.

During the First World War, in 1916, Smith enlisted in the Royal Defence Corps. This led to his writing non-fiction pieces for Punch and various other magazines on subjects as diverse as censorship and the military use of animals. When the war ended, Smith went back to journalism proper, writing a steady flow of short stories and articles, a book on British copper coinage in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries and a comic fantasy, the novel A Little Flutter concerning a middle-aged city clerk’s unusual inheritance and the fate of a Groo-Groo, a giant Patagonian bird. Smith later adapted A Little Flutter for the stage, and he also adapted two of the Carrados stories, ‘The Tragedy at Brookbend Cottage’ and ‘The Ingenious Mind of Rigby Lacksome’, though there is as yet no evidence that any of these scripts were ever performed. But that is not the case with Smith’s only original stage play to feature Max Carrados, Blind Man’s Bluff, which opened at the Chelsea Palace of Varieties on 8 April 1918. Smith had written the play for the actor Gilbert Heron who, the previous year, had had great success with anadaptation of the Carrados story, ‘The Game Played in the Dark’. Heron’s play, In the Dark, had opened at the London Metropolitan Music Hall in February 1917 as a dramatic interlude in a programme that featured the famous ventriloquist Fred Russell and other variety acts. The play was reviewed positively, not least for its ‘great surprise finish’ when, as in Smith’s short story, the final scene was performed in absolute darkness. Blind Man’s Bluff also includes a blackout, which Carrados brings about in the thrilling climax of a battle of wits with a cold-blooded spy, and—betraying its origins as a music hall act—his play also ingeniously accommodates an on-stage demonstration of ju-jitsu. Both of the plays continued to be included in variety bills until the early 1920s, while In the Dark was broadcast on radio by the fledgling British Broadcasting Company (later ‘Corporation’ from 1927) several times including, for the last time, in 1930.

The last of Smith’s 26 short stories about Carrados was published in 1927 but Smith revived the character for the novel-length thriller The Bravo of London, which was first published in 1934 and later adapted—by Smith—for the stage, though again no performances have yet been traced. Although the novel has something in common with the short story ‘The Missing Witness Sensation’, first published in Pearson’s Magazine eight years earlier, Carrados’s return, in which he faces the monstrous forger Julian Joolby, was welcomed by readers and critics alike, with one reviewer praising the author for ‘a sound sense of the macabre and a grim humour which raises his work above the average level of thrillers’. A year later, Carrados took his last bow in a profile written and narrated by Smith for the radio series Meet the Detective, broadcast on the BBC’s Empire Service in May 1935. While Carrados was not to appear again, Smith continued to write stories about Kai Lung, with the final collection of stories, Kai Lung beneath the Mulberry Tree, appearing in 1940, forty years after the wiliest of philosophers’ first appearance in The Wallet of Kai Lung.

A very private man throughout his life, Smith died in Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, in 1942.

TONY MEDAWAR

March 2018

CHAPTER I (#ue3c5f5fd-c71d-5209-8205-95fefb4474d5)

THE ROAD TO TAPSFIELD

‘A TOLERABLY hard nut to crack, of course,’ said the self-possessed young man with the very agreeable smile—an accomplishment which he did not trouble to exercise on his associate in this case, since they knew one another pretty well and were strictly talking business; ‘or you wouldn’t be so dead keen about me, Joolby.’

‘Oh, I don’t know; I don’t know, Nickle,’ replied the other with equal coolness, ‘There are hundreds—thousands—of young demobs like yourself to be had today for the asking. All very nice chaps personally, quite unscrupulous, willing to take any risk, competent within certain limits, and not one of them able to earn an honest living. No; if I were you I shouldn’t fancy myself indispensable.’

‘Having now disclosed our mutual standpoints and in a manner cleared the ground, let’s come down to concrete foundations,’ suggested Nickle. ‘You’re hardly thinking of opening a beauty parlour at this benighted Tapsfield?’

The actual expression of the man addressed as Joolby at this callous thrust did not alter, although it might be that a faint quiver of feeling played across the monstrous distortion that composed his face, much as a red-hot coal shows varying shades of incandescence without any change of colour or surface. For such was Joolby’s handicap at birth that any allusion to beauty or to looks made in his presence must of necessity be an outrage.

He was indeed a creature who by externals at all events had more in common with another genus than with that humanity among which fate had cast him, and his familiar nickname of ‘The Toad’ crudely indicated what that species might be. Beneath a large bloated face, mottled with irregular patches of yellow and brown, his pouch-like throat hung loose and pulsed with a steady visible beat that held the fascinated eyes of the squeamish stranger. Completely bald, he always wore a black skull-cap, not for appearance, one would judge, since it only heightened his ambiguous guise, and his absence of eyebrows was emphasised by the jutting hairless ridges that nature had substituted.

Nor did the unhappy being’s unsightliness end with these facial blots, for his shrunken legs were incapable of wholly supporting his bulky frame and whenever he moved about he drew himself slowly and painfully along by the aid of two substantial walking sticks. Only in one noticeable particular did the comparison fail, for while the eye of a toad is bright and gentle Joolby’s reflected either dull apathy or a baleful malice. Small wonder that women often turned unaccountably pale on first meeting him face to face and the doughty urchins of the street, although they were ready enough to shrill ‘Toady, toady, Joolby!’ behind his back, shrieked with real and not affected terror if chance brought them suddenly to close quarters.

‘The one thing that makes me question your fitness for the job is an unfortunate vein of flippancy in your equipment, Nickle,’ commented Joolby without any display of feeling. ‘No doubt it amuses you to score off people whom you despise, but it also gives you away and may put them on their guard about something that really matters. This is just a friendly warning. What sort of business should I be able to do with anyone if I ever let them see my real feelings towards them—yourself, for instance?’

‘True, O cadi,’ admitted Nickle lightly. ‘People aren’t worth sticking the manure fork into—present company included—but it’s frequently temptatious. Proceed, effendi.’

‘The chap who has been at Tapsfield already was a wash-out and I’ve had to drop him. He’ll never come to any good, Nickle—no imagination. Now that’s where you should be able to put something through, and I have confidence in you. You’re a very convincing liar.’

‘You are extremely kind, Master,’ replied Nickle. ‘What had your dud friend got to say about it?’

‘He came back sneeping that it was impossible even to get in anywhere there because they are so suspicious of strangers.’

‘To do with the mill, I suppose?’

‘Of course—what else? He couldn’t stay a night—not a bed to be had anywhere for love or money unless someone can guarantee you bona fide. The fool fish simply dropped in on them with a bag of golf clubs—and there wasn’t a course within five miles. You’ll have to think out something brighter, Nickle.’

‘Leave that to me. Just exactly what do you want to know, Joolby?’

‘Everything that there is to be found out—position, weaknesses, precautions, routine, delivery and despatch: the whole business. And particularly any of the people who are open to be got at with some sort of inducement. But for God’s sake—’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘No need to, Nickle. I only want to emphasise that whatever you do, not a shadow of suspicion must be risked. We haven’t decided yet on what lines the thing will go through and we can’t have any channel barred. I can give you a fortnight.’

‘Thanks; I shall probably take a month. And it’s understood to be five per cent on the clean-up and all exes meanwhile?’

‘Reasonable expenses, Nickle. You can’t spend much in a backwash like this Tapsfield.’

‘My expenses always are reasonable—I mean there is always a reason for them. But I notice that you don’t kick at the other item. That doesn’t look as if you were exactly optimistic of striking a gold mine, Joolby.’

‘In your place I might have thought that, but I shouldn’t have said it. Now I know that you will make it up in exes. Well, let me tell you this, Mr Nickle: no, on the whole I won’t. But what should you say if I hinted not at hundreds or thousands but millions?’

‘I should say much the same as the duchess did—“Oh, Hell, leave my leg alone!”’ languidly admitted Mr Nickle.

The road from Stanbury Junction to Tapsfield was agreeably winding—assuming, of course, that you were at the time susceptible to the graces of nature and not hurrying, for instance, to catch a train—pleasantly shady for such a day as this, and attractively provided, from the leisurely wayfarer’s point of view, with a variety of interesting features. For one stretch it fell in with the vulgarly babbling little river Vole and for several furlongs they pursued an amicable course together, until the Vole, with a sudden flirt like the misplaced coquetry of a gawky wench, was half way across a meadow and although it made some penitent advances to return, the road declined to make it up again and even turned away so that thereafter they meandered on apart: a portentous warning to the numerous young couples who strolled that way on summer evenings, had they been in the mood to profit by the instance. Its place was soon taken by a lethargic, weed-clogged dyke, a very different stream but profuse of an engaging medley of rank grass and flowers—tall bulrushes and swaying sedge, pale flags, saffron kingcups and incredibly artificial-looking pink and white water-lilies, and the sure resort of countless dragonflies of extraordinary agility and brilliance. This channel at one point gave occasion for a moss-grown bridge whereon the curious might inform themselves by the authority of a weather-beaten sign that while the road powers of the county of Sussex claimed the bridge and all that appertained to it, they expressly disclaimed liability for any sort of accident or ill that might be experienced there, and in fact held you strictly responsible and answerable in amercement.

Everywhere was peaceful shade and a cool green smell and the assurance that anything that was happening somewhere else didn’t really matter. A few small, substantial clouds, white and rotund like the puffs of smoke from a cannon’s mouth in an old-type print, floated overhead but imposed on no one to the extent of foretelling rain. Actually, it was the phenomenally dry summer of 1921.

The single pedestrian who had come that way when the 3.27 down train steamed on appeared to be amenable to these tranquil influences, for he continually loitered and looked about, but the frequency with which he took out his watch and the alert expectancy of his backward glances would soon have discounted the impression of aimless leisure had there been anyone to observe his movements. And, in truth, nothing could have been further from casualness or lack of purpose than this inaction, for on that day, at that hour and in that place, the first essential move was being made in a design so vast and far-reaching that the whole future course of civilization might well hang on its issue. So might one disclose a tiny rill in the uplands of Thibet—and thousands of miles away the muddy yellow waters of the surging Whang Ho obliterate an inoffensive province.

Presently, following the same route, the distant figure of another pedestrian had come into sight, and swinging along the road at a fine resolute gait (indicative perhaps, since he wore a clerical garb, of robust Christianity) promised very soon to overtake the laggard. It is only reasonable to assume that in his case there was less inducement to examine the surroundings, for while the first could be dismissed at a glance as a stranger to those parts, the second was the Rev. Octavius Galton, vicar of Tapsfield, who, as everyone could tell you, paid a weekly visit on that day to an outlying hamlet with its little tin mission hall, straggling at least a mile beyond the Junction.

With the first appearance of this new character on the scene the behaviour of the loitering man underwent a change—trifling indeed, but not without significance. His progress was still slow, he continued to take interest in the unfolding details of his way, but he studiously refrained from looking round, and his watch had ceased to concern him. It was, if one would hazard a speculative shot, as though something that he had been expecting had happened now and he was prepared to play a part in the next development.

‘Good afternoon,’ called out the vicar as he went past—he conscientiously greeted every wayfarer encountered on his rounds, tramp or esquire, and few were so churlish as to be unresponsive.

‘Glorious weather, isn’t it?—though of course rain is really needed.’ The after-thought came from over his shoulder, for the Rev. Octavius did not carry universal neighbourliness to the extent of encouraging prolonged wayside conversation.

‘Good afternoon,’ replied the stranger, quite as genially. ‘Yes, isn’t it? Splendid.’

He made no attempt to enlarge the occasion and to all appearance the incident was over. But just when it would have been, Mr Galton heard a sharp exclamation—the instinctive note of surprise—and turned to see the other in the act of stooping to pick up some object.

‘I don’t suppose this is likely to be yours’—he had stopped automatically and the finder had quickened his pace to join him—‘but if you live in these parts you might hear who has lost it. Looks more like a woman’s purse, I should say.’

‘Dear me,’ said the vicar, ‘how unfortunate for someone! No, it certainly isn’t mine. As a matter of fact, I never really use a purse—absurd of me I am often told, but I never have done. Have you seen what is in it?’

Obviously not, since he had only just picked it up and had at once offered it for inspection, but at the suggestion the catch was pressed and the contents turned out for their mutual examination. They were strictly in keeping with the humdrum appearance of the purse itself—no pretty trifle but a substantial thing for everyday shopping—a ten-shilling note, as much in silver and bronze, the stub of a pencil, two safety pins and a newspaper cutting relating to an infallible cough cure.

‘Dropped by one of my poorer parishioners doubtless,’ commented Mr Galton, as the collection was replaced by the finder; ‘but unluckily there is nothing to show which. You will, of course, leave it at the police station?’

‘Well,’ was the reply, given with thoughtful deliberation, ‘if you don’t mind I’d rather prefer to leave it with you, sir.’

‘Oh!’ said the vicar, not unflattered, ‘but the usual thing—’

‘Yes, so I imagine. But I have an idea that you would be more likely to hear whose it is than anyone else might. Then in these cases I believe that there is some sort of a deduction made if the police have the handling of it—not very much, I daresay, but to quite a poor woman even the matter of a shilling or two—eh?’

‘True; true. No doubt it would be a consideration. Well, since you urge it, I will take charge of the find and notify it through the most likely channels. Then if we hear nothing of the loser within say a week I think I shall have to fall back on the local constabulary.’

‘Oh, quite so. But I hardly think that in a little place—I take it that this is only a village?’

‘Tapsfield? A bare five hundred souls at the last census. Of course, the parish is another matter, but that is really a question of area. You are a stranger, I presume? And, by the way, you had better favour me with your address if you don’t mind.’

‘I should be delighted,’ said the stranger with his charming smile—an accomplishment he did not make the mistake of overdoing—‘but just at the moment I haven’t got such a thing—not on this side of the world, I should say. My name is Dixson—Anthony Dixson—and I am over from Australia for a few weeks, a little on business but mostly as a holiday.’

‘Australia? Really; how very interesting. One of our young men—a member of the choir and our best hand-bell ringer, as a matter of fact—left for Australia only last month: Sydney, to be explicit.’

‘My place is Beverley in West Australia,’ volunteered the Colonial. ‘Quite the other side of the Continent, you know.’

‘Still, it is in the same country, is it not?’ The vicar put this unimpeachable statement reasonably but with tolerant firmness. ‘However: the question of an address. It is only that after a certain time, if no one comes forward, it is customary to return anything to the finder.’

‘I don’t think that need trouble anyone in this case, sir. I expect that there are several good works going on in the place that won’t refuse a few shillings. If no one puts in a claim perhaps you wouldn’t mind—?’

‘Now that’s really very kind and generous of you; very thoughtful indeed, Mr Dixson. Yes, we have a variety of useful organisations in the parish, and most of them, as you tactfully suggest, are not by any means self-supporting. There is the Social Centre Organisation, the Literary, Dramatic and Debating Society, a Blanket and Clothing Fund, Junior Athletic Club, the C.L.B. and the C.E.G.G., and half a dozen other excellent causes, to say nothing of a special effort we are making to provide the church heating apparatus with a new boiler. Still, an outsider can’t be interested in our little local efforts, but it’s heartening—distinctly heartening—quite apart from the amount and the—er—slightly speculative element of the contribution.’

‘Well, perhaps not altogether an outsider, in a way,’ suggested Dixson a little cryptically.

‘Oh, really? You mean that you have some connection with Tapsfield? I did not gather—’

‘Actually, that’s what brought me here. My father was never out of Australia in his life, and this is the first time that I have been, but we always understood—I suppose it was passed down from generation to generation—that a good many years ago we had come from a place called Tapsfield somewhere in the south of England.’

‘This is the only place of the name that I know of,’ said the vicar. ‘Possibly the parochial records—’

‘One little bit of evidence—if you can call it that—came to light when I went through my father’s things after his death last year,’ continued Dixson. ‘Plainly it had been kept for its personal association, though it’s only brass and can’t be of any value. I mean, no one called Anthony Dixson would be likely to throw it away and by what I’m told one of us always has been called Anthony, and very few people nowadays spell the name D-i-x-s-o-n.’

‘A coin—really?’ The vicar put on his reading glasses and took the insignificant object that Dixson had meanwhile extracted from a pouch of his serviceable leather belt. ‘I have myself—’

‘I don’t see that it can be a coin because that should have the king—Charles the Second wouldn’t it be?—on it. In fact I don’t understand why—’

‘Oh, but this is quite all right,’ exclaimed Mr Galton with rising enthusiasm, as he carefully deciphered the inscription, ‘It is one of an extensive series called the seventeenth-century tokens. I speak as a collector in a modest way, though I personally favour the regal issues—“Antho Dixson, Cordwainer, of Tapsfield in Susex”, and on the other side “His half peny 1666”, with a device—probably the arms of the cordwainers’ company.’

‘Yes,’ said the namesake of Antho Dixson of 1666 carelessly. ‘That’s what it seems to read isn’t it?’

‘But this is most interesting; really most extraordinarily interesting,’ insisted the now thoroughly intrigued clergyman. ‘In the year when the Great Fire of London was raging and—yes—I suppose Milton would be writing Paradise Lost then, your remote ancestor was issuing these halfpennies to provide the necessary shopping change here in Tapsfield. And now, more than two hundred and fifty years later, you turn up from Australia to visit the birthplace of your race. Do you know, I find that a really suggestive line of thought, Mr Dixson; most extraordinarily impressive.’

‘I can hardly expect to discover any Dixson here,’ commented Anthony, with a speculative note of inquiry, ‘and even if there were they would be too remote to have any actual relationship. But possibly there are some of the old houses standing—’

‘There are no Dixsons now,’ replied Mr Galton with decision. ‘I know every family and can speak positively. Even in the more common form we have no one of that surname. As for old houses—well, Tapsfield is scarcely a show-place, one must admit. “Model” perhaps, but not picturesque. The church is practically the only thing remaining of any note: if you can spare the time I should be delighted to take you over the building where your forebears worshipped. We are almost there now. Was there any particular train back that you were thinking of catching?’

‘As a matter of fact,’ said Dixson readily, ‘I came intending to stay a few days and look around here. I’ve always had a hankering to see the place properly, and in any case I don’t find that living in London suits me. So I shall hope to see over the church when it’s most convenient to you.’

‘Oh, you intend staying? I didn’t—I mean, not seeing any luggage, I inferred that you were just here for the afternoon. Of course—er—any time I shall be really delighted.’

‘I left my traps up at the station. I must find a room and then I can have them sent over. To tell you the truth, I couldn’t stand London any longer. I have hardly slept a wink for the last two nights. Perhaps you could put me in the way of a place where they let apartments?’

It was a very natural request in the circumstances—nothing could have been more so—but for some reason the vicar did not reply at once, nor did his expression seem to indicate that he was considering the most suitable addresses. Actually, one might have guessed that he had become slightly embarrassed.

‘Almost any sort of a place would suit me—just simple meals and a bedroom,’ prompted Dixson, without apparently noticing his acquaintance’s difficulty. ‘On the whole I prefer a private house—even a workman’s—to an inn, but that is only a harmless fancy.’

‘Awkwardly enough, a room is practically unobtainable either at a private house or even at one of the inns,’ at length admitted Mr Galton with slow reluctance. ‘It’s an unusual state of things, I know, but there are special circumstances and the people here have always been encouraged to refuse chance visitors. The consequence is that nobody sets out to let apartments.’

‘“Special circumstances”? Does that mean—?’

‘Evidently you have not heard of the Tapsfield paper mill, Mr Dixson. The particular circumstance is that all the paper used in the printing of Bank of England notes is made here in the village.’

‘You surprise me. I should have imagined that they would be printed in a strongroom at the Bank itself or something of that sort. Surely—?’

‘Printed, yes,’ assented the vicar. ‘I believe they are. But the peculiar and characteristic paper is all made within a stone’s throw of where we are. It is really our only local industry and practically all the people are either employed there or dependent on the business. Of course it is a very important and confidential—I might almost say dangerous—position, and although there is no actual rule, newcomers do not find it practicable to settle here and strangers are not accommodated.’

‘Newcomers and strangers, eh?’ The visitor laughed with a slightly wry good humour.

‘I know, I know,’ admitted the vicar ruefully. ‘It is we who are really the interlopers and newcomers compared with your status. But the difficulty is that owing to the established order of things it is out of these good people’s power to make exceptions.’

‘But what am I to do about it?’ protested Mr Dixson rather blankly. ‘You see how I am placed now?… I can’t go back to London for another wretched night, and it would be too late to get on to some other district … I never dreamt of not finding any sort of lodgings. Surely there must be someone with a room to spare, even if they don’t make it a business. Then if you wouldn’t mind putting in a word—’

‘Now let me think; let me think,’ mused the good-natured pastor. ‘It would be really deplorable if you of all people should find yourself cold-shouldered out of Tapsfield. As you say, there may be someone—’

Since the moment when chance had brought them into conversation, the two men had been walking together towards the village of which the only evidence so far had been an ancient tower showing above a mass of trees, where a querulous congregation of rooks incessantly put resolutions and urged amendments. Now a final bend of the devious lane laid the main village street open before them, and so near that they were in it before Mr Galton’s cogitation had reached any practical expression.

‘There surely might be someone—?’ he repeated hopefully, for by this time, what with one slight influence and another, the excellent man felt himself almost morally bound to get Dixson out of his dilemma. ‘I have it!—at least, there’s really quite a good chance there—Mrs Hocking.’

‘Splendid,’ acquiesced Dixson with an easy assumption that this was as good as settled. ‘Mrs Hocking by all means.’

‘She is an aunt of the youth I mentioned—the one who has gone to Sydney. He lived there, so that she ought to have a bedroom vacant. And I expect that she would like to hear about Australia, so that might make it easier.’

‘Quite providential,’ was Dixson’s comment, and rather inconsequently he could not refrain from adding: ‘How lucky that I didn’t come from Canada! I am sure that if you would kindly introduce me and put in a good word on the score of respectability, that—coupled with a willingness to pay in advance—would make it all right with Mrs Hocking.’

‘We can but see,’ agreed Mr Galton. ‘I will use my utmost powers of persuasion. She is really a most hospitable woman—I believe she provides the buns for the Guild Working Party tea regularly every other Wednesday.’

‘I happen to be very fond of buns,’ said Dixson gravely. ‘I am sure that we shall get on together famously.’

‘Oh, really? As a matter of fact, I never touch them—flatulence. However, her cottage is only just there over the way. Now, had we better—no, perhaps on the whole if you waited by the gate while I broached the matter—what do you think?’

‘I am entirely in your hands,’ said Dixson diplomatically. ‘It’s most tremendously good of you. Is there only a Mrs Hocking?’

‘Oh, no. She has a husband and a daughter as well—an extremely worthy family—but as they work at the mill, like nearly everyone else here, she will probably be the only one at home just now.’

‘Perhaps I had better wait as you suggest then,’—really a non sequitur, thought the vicar—‘and, if it’s any inducement, I’m doing pretty well at home, you know, so that I shouldn’t mind something above the ordinary in the circumstances.’

The gesture that Mr Galton threw back as he turned into the formal little garden of a painfully modern cottage might have implied that it would be or it wouldn’t—or indeed any other meaning. Dixson strolled on as far as an intersecting lane. It began with a couple of rows of hygienic cottages on the severe plan of Mrs Hocking’s, but in the distance a high wall indicated premises of a different use, and from this direction came the regular but not too discordant beat of machinery at work. Less in keeping with the rural scene than this mild evidence of industry was the presence of a sentry-box before what was apparently the principal gate of the place. Plainly a strict guard was kept, but the picket himself was too far away or not sufficiently in view for the actual force he was drawn from to be determined. It was the first indication that Tapsfield held anything particular to safeguard and Dixson experienced a momentary flicker of excitement.

‘So that’s that,’ he summarised as he turned back without betraying any further symptom of interest. He had not long to wait for his new acquaintance’s reappearance.

‘Our efforts have been crowned with success,’ announced Mr Galton, beaming with satisfaction. ‘Mrs Hocking only stipulates for no late cooking.’

‘Famous,’ replied Dixson, a little more careless of his speech now that he had secured quarters. ‘I never tackle a heavy meal after sunset myself—insomnia.’

‘The question of terms I have left for your own arrangement. But I do not think that you will find Mrs Hocking too exacting.’

‘I’m sure. And you’ll remember your promise? I’m dying to see the celebrated twelfth-century canopied sedilia.’

‘You have heard of our unique Norman feature? Oh, really!’ It would have been impossible to strike a better claim on the vicar’s favour. ‘Really, Mr Dixson, I had no idea that you took an actual interest in ecclesiastical architecture.’

‘Well, naturally, I felt a deep regard for the church where my forefathers worshipped. Way out at home someone happened to be able to lend me a sort of guide to Sussex. I simply lapped it. Now I want to go over every nook and cranny in Tapsfield.’

‘So you shall; so you shall,’ promised the clergyman. ‘I will answer for it. We’ll arrange about the church as soon as you are settled.’ He had turned to go, but before Dixson was through the gate he heard his name called with a rather confidential import. ‘And, by the way, while I think of it. We have a little informal entertainment in the school house once a week—a, er, “penny reading” we call it.’

‘A sort of sing-song, I suppose?’

‘Precisely; but not in any way—er—boisterous. Well, we find it increasingly difficult sometimes—not that everyone isn’t most willing; quite the contrary, indeed, but what handicaps us with our limited material is to provide variety. Now I was wondering if you could be persuaded to give a little talk—it need only be quite short, of course—on “Life and Adventure in the Land of the Wombat”, or naturally, any other title that commends itself to you. You—? Well, think it over, won’t you?’

‘That was a tolerably soft shell,’ reflected Dixson, as he discreetly avoided discovering any of the interested eyes that had been following the details of his arrival from behind stealthily arranged curtains. ‘Now for Mrs Hocking—and the husband and daughter who work at the paper mill.’

CHAPTER II (#ue3c5f5fd-c71d-5209-8205-95fefb4474d5)

JOOLBY DOES A LITTLE BUSINESS

STRANGERS who had occasion to visit Mr Joolby’s curio and antique shop—and quite a number of very interesting people went there from time to time—often had some difficulty in finding it at first. For Mr Joolby, in complete antagonism to modern business methods, not only did not advertise but seemed to shun the more obvious forms of commercial advancement. His address had never appeared in that useful compilation, the Post Office London Directory, and as yet—surely a simple enough matter—Mr Joolby had not taken the trouble to have the omission righted. The street in which he had set up, while far from being a slum, was not one of the better-known and easily remembered thoroughfares of the East End, so that collectors who stumbled on his shop (and occasionally discovered some surprising things there) more often than not found themselves quite unable to describe its exact position to others afterwards, unless they had the forethought at the time to jot down the number 169 and the name Padgett Street before they passed on elsewhere. ‘A couple of turns out of Commercial Road, somewhere towards the other end’ was as good as keeping a secret.

Nor would the inquirer’s search be finished once he reached Padgett Street, for with the modesty that marked his activity in sundry other ways, Mr Joolby had neglected to have his name proclaimed about his place of business or else he had allowed it to fade from the public eye under the combined erosion of time and English weather. Of the place of business itself little could be gleaned from outside, for the arrangement of the shop window was more in accord with Oriental reticence than in line with modern ideas of display. Dust and obscurity were the prevailing impressions.

Inside was an astonishing medley of the curious and antique and in this branch of his activities the dictum of an impressed collector did not seem unduly wide of the mark: that Mr Joolby could supply anything on earth, if only he knew where to put his hands upon it. And if the arrangement of the large room one first entered suggested more the massed confusion of an extremely bizarre furniture depository than any other comparison, it had what, to its proprietor’s way of thinking, was this supreme advantage: that from a variety of points of view it was possible to see without being seen, not only about the shop itself but even including the street and pavement.

At the moment that we have chosen for this intrusion—a time some weeks later than the arrival of ‘Anthony Dixson’ in Tapsfield—the place at a casual glance had all the appearance of being empty, for the figure of Won Chou, Mr Joolby’s picturesquely exotic shop assistant, both on account of absolute immobility and the protective obscuration of his drab garb, did not invite attention. But if unseen himself Won Chou was far from being unobservant and when a passer-by did not in fact pass by—when after an abstracted saunter up he threw an anxious glance along the street in both directions and then slipped into the doorway—a yellow hand slid out and in some distant part of the house the discreet tintinnabulation of a warning bell gave its understood message.

Inside the shop the visitor—no one could ever have mistaken him for a customer, unless, perhaps, qualified by ‘rum’—looked curiously about with the sharp and yet furtive reconnaissance of the habitual pilferer. But even so, he failed at the outset to discover the quiescent figure of Won Chou and he was experiencing a slight mental struggle between deciding whether it would be more profitable to wait until someone came or to pick up the most convenient object and bolt, when the impassive attendant settled the difficulty by detaching himself from the screening background and noiselessly coming forward. So quietly and unexpected indeed that Mr Chilly Fank, whose nerves had never been his strongest asset (the playful appellation ‘Chilly’ had reference to his condition when any risk appeared), experienced a momentary shock which he endeavoured to cover by the usual expedient of a weakly aggressive swagger.

‘’Ullo, Chink!’ he exclaimed with an offensive heartiness, ‘blimey if I didn’t take you for a ruddy waxwork. You didn’t oughter scare a bloke like that, making out as you wasn’t real. Boss in?’

‘Yes no,’ replied Won Chou with extreme simplicity and a perfect assurance in the adequacy of his answer.

‘Yes—no? Whacha mean?’ demanded Mr Fank, to whom suspicion of affront was an instinct. ‘Which, you graven image?’

‘All depend,’ explained Won Chou with unmoved composure. ‘You got come bottom side chop pidgin? You blong same pidgin?’

‘Coo blimey! This isn’t a bloomin’ restrong, is it, funny? I want none of yer chop nor yer pigeon either. Is old Joolby abart? If yer can’t speak decent English nod yer blinkin’ ’ed, one wei or the other. Get me, you little Chinese puzzle?’

‘My no sawy. Makee go look-see,’ decided Won, and he melted out of the shop by the door leading to the domestic quarters.

Left to himself Mr Chilly Fank nodded his head sagely several times to convey his virtuous disgust at this pitiable exhibition.

‘Tchk! tchk!’ he murmured half aloud. ‘Exploitation of cheap Asiatic labour! No wonder we have a surplus industrial population and the nachural result that blokes like me—’ but at this point the house door opened again, Won Chou having returned with unforeseen expedition, so that Mr Fank had to turn away rather hastily from the locked show-case which he had been investigating with a critical touch and affect an absorbing interest in something taking place in the street beyond until he suddenly became aware of the other’s presence.

‘Back again, What-ho? Well, you saffron jeopardy, don’t stand like a blinkin’ Eros. Wag yer ruddy tongue abart it.’

‘My been see,’ conceded Won Chou impartially. ‘Him belongy say: him you go come.’

‘My strikes! if this isn’t the nattiest little vade-mecum that ever was!’ apostrophised Mr Fank to the ceiling bitterly. ‘Look here, Confucius, forget yer chops an yer’ pigeon and spit it aht straightforward. The boss—Joolby—is he in or not and did he say me go or him come? Blarst yer, which—er—savvy?’

At this, however, it being apparently rather a subtler idiom than the hearer’s limited grasp of an alien vernacular could cope with, Won Chou merely relapsed into an attitude of studious melancholy, extremely trying to Mr Fank’s conception of the yellow man’s status. He was on the point of commenting on Won Chou’s shortcomings with his customary delicacy of feeling when the sound of hobbling sticks approaching settled the point without any further trouble.

As Mr Joolby was—ethnologically at all events—white, a person of obvious means, and in various subterranean ways reputedly powerful, Mr Fank at once assumed what he considered to be a more suitable manner and it was with an ingratiating deference that he turned to meet the dealer.

‘’Evening, governor,’ he remarked briskly, at the same time beginning to disclose the contents of an irregular newspaper parcel—fish and chips, it could have been safely assumed if he had been seen carrying it—that he had brought with him. ‘Remember me, of course, don’t you?’

‘Never seen you before,’ replied Mr Joolby, with an equally definite lack of cordiality. ‘What is it you want with me?’

To the ordinary business caller this reception might have been unpromising but Mr Fank was not in a position to be put off by it. He understood it indeed as part of the customary routine.

‘Fank—“Chilly” Fank,’ he prompted. ‘Now you get me surely?’

‘Never heard the name in my life,’ declared Joolby with no increase of friendliness.

‘Oh, right you are, governor, if you say so,’ accepted Fank, but with the spitefulness of the stinging insect he could not refrain from adding: ‘I don’t suppose I should have been able to imagine you if I hadn’t seen it. Doing anything in this way now?’

‘This,’ freed of its unsavoury covering, was revealed as an uncommonly fine piece of Dresden china. It would have required no particular connoisseurship to recognise that so perfect and delicate a thing might be of almost any value. Joolby, who combined the inspired flair of the natural expert with sundry other anomalous qualities in his distorted composition, did not need to give more than one glance—although that look was professionally frigid.

‘Where did it come from?’ he asked merely.

‘Been in our family for centuries, governor,’ replied Fank glibly, at the same time working in a foxy wink of mutual appreciation; ‘the elder branch of the Fanks, you understand, the Li-ces-ter-shire de Fankses. Oh, all right, sir, if you feel that way’—for Mr Joolby had abruptly dissolved this proposed partnership in humour by pushing the figure aside and putting a hand to his crutches—‘it’s from a house in Grosvenor Crescent.’

‘Tuesday night’s job?’

‘Yes,’ was the reluctant admission.

‘No good to me,’ said the dealer with sharp decision.

‘It’s the real thing, governor,’ pleaded Mr Fank with fawning persuasiveness, ‘or I wouldn’t ask you to make an offer. The late owner thought very highly of it. Had a cabinet all to itself in the drorin’-room there—so I’m told, for of course I had nothing to do with the job personally. Now—’

‘You needn’t tell me whether it’s the real thing or not,’ said Mr Joolby. ‘That’s my look out.’

‘Well then, why not back yer knowledge, sir? It’s bound to pay yer in the end. Say a … well, what, about a couple of … It’s with you, governor.’

‘It’s no good, I tell you,’ reiterated Mr Joolby with seeming indifference. ‘It’s mucher too valuable to be worth anything—unless it can be shown on the counter. Piece like this is known to every big dealer and every likely collector in the land. Offer it to any Tom, Dick or Harry and in ten minutes I might have Scotland Yard nosing about my place like ferrets.’

‘And that would never do, would it, Mr Joolby?’ leered Fank pointedly. ‘Gawd knows what they wouldn’t find here.’

‘They would find nothings wrong because I don’t buy stuff like this that the first numskull brings me. What do you expect me to do with it, fellow? I can’t melt it, or reset it, or cut it up, can I? You might as well bring me the Albert Memorial … Here, take the thing away and drop it in the river.’

‘Oh blimey, governor, it isn’t as bad as all that. What abart America? You did pretty well with those cameos wot come out of that Park Lane flat, I hear.’

‘Eh, what’s that? You say, rascal—’

‘No offence, governor. All I means is you can keep it for a twelvemonth and then get it quietly off to someone at a distance. Plenty of quite respectable collectors out there will be willing to buy it after it’s been pinched for a year.’

‘Well—you can leave it and I’ll see,’ conceded Mr Joolby, to whom Fank’s random shot had evidently suggested a possible opening. ‘At your own risk, mind you. I may be able to sell it for a trifle some day or I may have all my troubles for nothing.’ But just as Chilly Fank was regarding this as satisfactorily settled and wondering how he could best beat up to the next move, the unaccountable dealer seemed to think better—or worse—of it for he pushed the figure from him with every appearance of a final decision. ‘No; I tell you it isn’t worth it. Here, wrap it up again and don’t waste my time. I’d mucher rather not.’

‘That’ll be all right, governor,’ hastily got in Fank, though similar experiences in the past prompted him not to be entirely impressed by a receiver’s methods. ‘I’ll leave it with you anyhow; I know you’ll do the straight thing when it’s planted. And, could you—you don’t mind a bit on account to go on with, do you? I’m not exactly what you’d call up and in just at the moment.’

‘A bit on account, hear him. Come, I like that when I’m having all the troubles and may be out of my pocket in the end. Be off with you, greedy fellow.’

‘Oh rot yer!’ exclaimed Fank, with a sudden flare of passion that at least carried with it the dignity of a genuine emotion; ‘I’ve had just abart enough of you and your blinkin’ game, Toady Joolby. Here, I’d sooner smash the bloody thing, straight, than be such a ruddy mug as to swallow any of your blahsted promises,’ and there being no doubt that Mr Fank for once in a way meant approximately what he said, Joolby had no alternative, since he had every intention of keeping the piece, but to retire as gracefully as possible from his inflexible position.

‘Well, well; we need not lose our tempers, Mr Fank; that isn’t business,’ he said smoothly and without betraying a shadow of resentment. ‘If you are really stoney up—I’m not always very quick at catching the literal meaning of your picturesque expressions—I don’t mind risking—shall we say?—one half a—or no, you shall have a whole Bradbury.’

‘Now you’re talking English, sir,’ declared the mollified Fank (perhaps a little optimistically), ‘but couldn’t you make it a couple? Yer see—well’—as Mr Joolby’s expression gave little indication of rising to this suggestion—‘one and a thin ’un anyway.’

‘Twenty-five bobs,’ conceded Joolby. ‘Take me or leave it,’ and since there was nothing else to be done, this being in fact quite up to his meagre expectation, Chilly held out his hand and took it, only revenging himself by the impudent satisfaction of ostentatiously holding up the note to the light when it was safely in his possession.

‘You need not do that, my young fellow,’ remarked Mr Joolby, observing the action. ‘I know a dud note when I see it.’

‘Oh I don’t doubt that you know one all right, Mr Joolby,’ replied Fank with gutter insolence. ‘It’s this bloke I’m thinking of. You’ve had a lot more experience than me in that way, you see, so I’ve got to be blinkin’ careful,’ and as he turned to go a whole series of portentous nods underlined a mysterious suggestion.

‘What do you mean, you rascal?’ For the first time a possible note of misgiving tinged Mr Joolby’s bloated assurance. ‘Not that it matters—there’s nothing about me to talk of—but have you been—been hearing anything?’

It was Mr Fank’s turn to be cocky: if he couldn’t wangle that extra fifteen bob out of The Toad he could evidently give him the shivers.

‘Hearing, sir?’ he replied from the door, with an air of exaggerated guilelessness. ‘Oh no, Mr Joolby: whatever should I be hearing? Except that in the City you’re very well spoken of to be the next Lord Mayor!’ and to leave no doubt that this pleasantry should be fully understood he took care that his parting aside reached Joolby’s ear: ‘Idon’t think!’

‘Fank. Chilly Fank,’ mused Mr Joolby as he returned to his private lair, carrying the newly acquired purchase with him and progressing even more grotesquely than his wont since he could only use one stick for assistance. ‘The last time he came he had an amusing remark to make, something about keeping an aquarium …’

Won Chou was still at his observation post when the door opened again an hour later. Again he sped his message—a different intimation from the last, but conveying a sign of doubt for this time the watcher could not immediately ‘place’ the visitors. These were two, both men—‘a belong number one and a belong number two chop men,’ sagely decided Won Chou—but there was something about the more important of the two that for the limited time at his disposal baffled the Chinaman’s deduction. It was not until they were in the shop and he was attending to them that Won Chou astutely suspected this man perchance to be blind—and sought for a positive indication. Yet he was the one who seemed to take the lead rather than wait to be led and except on an occasional trivial point his movements were entirely free from indecision. Certainly he had paused at the step but that was only the natural hesitation of a stranger to the parts and it was apparently the other who supplied the confirmation.

‘This is the right place by the description, sir,’ the second man said.

‘It is the right place by the smell,’ was the reply, as soon as the door was opened. ‘Twenty centuries and a hundred nationalities mingle here, Parkinson. And not the least foreign—’

‘A native of some description, sir,’ tolerantly supplied the literal Parkinson, taking this to apply to the attendant as he came forward.

‘Can do what?’ politely inquired Won Chou, bowing rather more profoundly than the average shopman would, even to a customer in whom he can recognise potential importance.

‘No can do,’ replied the chief visitor, readily accepting the medium. ‘Bring number one man come this side.’

‘How fashion you say what want?’ suggested Won Chou hopefully.

‘That belong one piece curio house man.’

‘He much plenty busy this now,’ persisted Won Chou, faithfully carrying out his instructions. ‘My makee show carpet, makee show cabinet, chiney, ivoly, picture—makee show one ting, two ting, any ting.’

‘Not do,’ was the decided reply. ‘Go make look-see one time.’

‘All same,’ protested Won Chou, though he began to obey the stronger determination, ‘can do heap wella. Not is?’

A good natured but decided shake of the head was the only answer, and looking extremely sad and slightly hurt Won Chou melted through the doorway—presumably to report beyond that: ‘Much heap number one man make plenty bother.’

‘Look round, Parkinson,’ said his master guardedly. ‘Do you see anything here in particular?’

‘No, sir; nothing that I should designate noteworthy. The characteristic of the emporium is an air of remarkable untidiness.’

‘Yet there is something unusual,’ insisted the other, lifting his sightless face to the four quarters of the shop in turn as though he would read their secret. ‘Something unaccountable, something wrong.’

‘I have always understood that the East End of London was not conspicuously law-abiding,’ assented Parkinson impartially. ‘There is nothing of a dangerous nature impending, I hope, sir?’

‘Not to us, Parkinson; not as yet. But all around there’s something—I can feel it—something evil.’

‘Yes, sir—these prices are that.’ It was impossible to suspect the correct Parkinson of ever intentionally ‘being funny’ but there were times when he came perilously near incurring the suspicion. ‘This small extremely second-hand carpet—five guineas.’

‘Everywhere among this junk of centuries there must be things that have played their part in a hundred bloody crimes—can they escape the stigma?’ soliloquised the blind man, beginning to wander about the bestrewn shop with a self-confidence that would have shaken Won Chou’s conclusions if he had been looking on—especially as Parkinson, knowing by long experience the exact function of his office, made no attempt to guide his master. ‘Here is a sword that may have shared in the tragedy of Glencoe, this horn lantern lured some helpless ship to destruction on the Cornish coast, the very cloak perhaps that disguised Wilkes Booth when he crept up to shoot Abraham Lincoln at the play.’

‘It’s very unpleasant to contemplate, sir,’ agreed Parkinson discreetly.

‘But there is something more than that. There’s an influence—a force—permeating here that’s colder and deeper and deadlier than revenge or greed or decent commonplace hatred … It’s inhuman—unnatural—diabolical. And it’s coming nearer, it begins to fill the air—’ He broke off almost with a physical shudder and in the silence there came from the passage beyond the irregular thuds of Joolby’s sticks approaching. ‘It’s poison,’ he muttered; ‘venom.’

‘Had we better go before anyone comes, sir?’ suggested Parkinson, decorously alarmed. ‘As yet the shop is empty.’

‘No!’ was the reply, as though forced out with an effort. ‘No—face it!’ He turned as he spoke towards the opening door and on the word the uncouth figure, laboriously negotiating the awkward corners, entered. ‘Ah, at last!’

‘Well, you see, sir,’ explained Mr Joolby, now the respectful if somewhat unconventional shopman in the presence of a likely customer, ‘I move slowly so you must excuse being kept waiting. And my boy here—well-meaning fellow but so economical even of words that each one has to do for half a dozen different things—quite different things sometimes.’

‘Man come. Say “Can do”; say “No can do”. All same; go tell; come see,’ protested Won Chou, retiring to some obscure but doubtless ingeniously arranged point of observation, and evidently cherishing a slight sense of unappreciation.

‘Exactly. Perfectly explicit.’ Mr Joolby included his visitors in his crooked grin of indulgent amusement. ‘Now those poisoned weapons you wrote about. I’ve looked them up and I have a wonderful collection and, what is very unusual, all in their original condition. This,’ continued Mr Joolby, busying himself vigorously among a pile of arrows with padded barbs, ‘is a very fine example from Guiana—it guarantees death with convulsions and foaming at the mouth within thirty seconds. They’re getting very rare now because since the natives have become civilized by the missionaries they’ve given up their old simple ways of life—they will have our second-hand rifles because they kill much further.’

‘Highly interesting,’ agreed the customer, ‘but in my case—’

‘Or this beautiful little thing from the Upper Congo. It doesn’t kill outright, but, the slightest scratch—just the merest pin prick—and you turn a bright pea green and gradually swell larger and larger until you finally blow up in a very shocking manner. The slightest scratch—so,’ and in his enthusiasm Mr Joolby slid the arrow quickly through his hand towards Parkinson whose face had only too plainly reflected a fascinated horror from the moment of their host’s appearance. ‘Then the tapioca-poison group from Bolivia—’

‘Save yourself the trouble,’ interrupted the blind man, who had correctly interpreted his attendant’s startled movement. ‘I’m not concerned with—the primitive forms of murder.’

‘Not—?’ Joolby pulled up short on the brink of another panegyric, ‘not with poisoned arrows? But aren’t you the Mr Brooks who was to call this afternoon to see what I had in the way of—?’

‘Some mistake evidently. My name is Carrados and I have made no appointment. Antique coins are my hobby—Greek in particular. I was told that you might probably have something in that way.’

‘Coins; Greek coins.’ Mr Joolby was still a little put out by the mischance of his hasty assumption. ‘I might have; I might have. But coins of that class are rather expensive.’

‘So much the better.’

‘Eh?’ Customers in Padgett Street did not generally, one might infer, express approval on the score of dearness.

‘The more expensive they are, the finer and rarer they will be—naturally. I can generally be satisfied with the best of anything.’

‘So—so?’ vaguely assented the dealer, opening drawer after drawer in the various desks and cabinets around and rooting about with elaborate slowness. ‘And you know all about Greek coins then?’

‘I hope not,’ was the smiling admission.

‘Hope not? Eh? Why?’

‘Because there would be nothing more to learn then. I should have to stop collecting. But doubtless you do?’

‘If I said I did—well, my mother was a Greek so that it should come natural. And my father was a—um, no; there was always a doubt about that man. But one grandfather was a Levantine Jew and the other an Italian cardinal. And one grandmamma was an American negress and the other a Polish revolutionary.’

‘That should ensure a tolerably versatile stock, Mr Joolby.’

‘And further back there was an authentic satyr came into the family tree—so I’m told,’ continued Mr Joolby, addressing himself to his prospective customer but turning to favour the scandalised Parkinson with an implicatory leer. ‘You find that amusing, Mr Carrados, I’m sure?’

‘Not half so amusing as the satyr found it I expect,’ was the retort. ‘But come now—’ for Mr Joolby had meanwhile discovered what he had sought and was looking over the contents of a box with provoking deliberation.

‘To be sure—you came for Greek coins, not for Greek family history, eh? Well, here is something very special indeed—a tetradrachm struck at Amphipolis, in Macedonia, by some Greek ruler of the province but I can’t say who. Perhaps Mr Carrados can enlighten me?’

Without committing himself to this the blind man received the coin on his outstretched hand and with subtile fingers delicately touched off the bold relief that still retained its superlative grace of detail. Next he weighed it carefully in a cupped palm, and then after breathing several times on the metal placed it against his lips. Meanwhile Parkinson looked on with the respect that he would have accorded to any high-class entertainment; Joolby merely sceptically indifferent.

‘Yes,’ announced Carrados at the end of this performance, ‘I think I can do that. At all events I know the man who made it.’

‘Come, come, use your eyes, my good sir,’ scoffed Mr Joolby with a contemptuous chuckle. ‘I thought you understood at least something about coins. This isn’t—I don’t know what you think—a Sunday school medal or a stores ticket. It’s a very rare and valuable specimen and it’s at least two thousand years old. And you “know the man who made it”!’

‘I can’t use my eyes because my eyes are useless: I am blind,’ replied Carrados with unruffled evenness of temper. ‘But I can use my hands, my finger-tips, my tongue, lips, my commonplace nose, and they don’t lead me astray as your credulous, self-opinionated eyes seem to have done—if you really take this thing for a genuine antique,’ and with uncanny proficiency he tossed the coin back into the box before him.

‘You can’t see—you say that you are blind—and yet you tell me, an expert, that it’s a forgery!’

‘It certainly is a forgery, but an exceptionally good one at that—so good that no one but Pietro Stelli, who lives in Padua, could in these degenerate days have made it. Pietro makes such beautiful forgeries that in my less experienced years they have taken even me in. Of course I couldn’t have that so I went to Padua to find out how he worked, and Peter, who is, according to his lights, as simple and honest a soul as ever breathed, willingly let me watch him at it.’

‘And how,’ demanded Mr Joolby, seeming almost to puff out aggression towards this imperturbable braggart; ‘how could you see him what you call “at it”, if, as you say, you are blind? You are just a little too clever, Mr Carrados.’

‘How could I see? Exactly as I can see’—stretching out his hand and manipulating the extraordinarily perceptive fingers meaningly—‘any of the ingenious fakes which sharp people offer the blind man; exactly as I could see any of the thousand and one things that you have about your shop. This’—handling it as he seemed to look tranquilly at Mr Joolby—‘this imitation Persian prayer-rug with its lattice-work design and pomegranate scroll, for instance; exactly as I could, if it were necessary, see you,’ and he took a step forward as though to carry out the word, if Mr Joolby hadn’t hastily fallen back at the prospect.

The prayer-rug was no news to Mr Joolby—although it was ticketed five guineas—but he had had complete faith in the tetradrachm notwithstanding that he had bought it at the price of silver; and despite the fact that he would still continue to describe it as a matchless gem it was annoying to have it so unequivocally doubted. He picked up the box without offering any more of its contents, and hobbling back to the desk with it slammed the drawer home in swelling mortification.

‘Well, if that is your way of judging a valuable antique, Mr Carrados, I don’t think that we shall do any business. I have nothing more to show, thank you.’

‘It is my way of judging everything—men included—Mr Joolby, and it never, never fails,’ replied Carrados, not in the least put out by the dealer’s brusqueness. It was a frequent grievance with certain of this rich and influential man’s friends that he never appeared to resent a rudeness. ‘And why should I,’ the blind man would cheerfully reply, ‘when I have the excellent excuse that I do not see it?’

‘Of course I don’t mean by touch alone,’ he continued, apparently unconscious of the fact that Mr Joolby’s indignant back was now pointedly towards him. ‘Taste, when it’s properly treated, becomes strangely communicative; smell’—there could be no doubt of the significance of this allusion from the direction of the speaker’s nose—‘the chief trouble is that at times smell becomes too communicative. And hearing—I daren’t even tell you what a super-trained ear sometimes learns of the goings-on behind the scenes—but a blind man seldom misses a whisper and he never forgets a voice.’

Apparently Mr Joolby was not interested in the subtleties of perception for he still remained markedly aloof, and yet, had he but known it, an exacting test of the boast so confidently made was even then in process, and one moreover surprisingly mixed up with his own plans. For at that moment, as the visitor turned to go, the inner door was opened a cautious couple of inches and:

‘Look here, J.J.,’ said the unseen in a certainly distinctive voice, ‘I hope you know that I’m waiting to go. If you’re likely to be another week—’

‘Don’t neglect your friend on our account, Mr Joolby,’ remarked Carrados very pleasantly—for Won Chou had at once slipped to the unlatched door as if to head off the intruder. ‘I quite agree. I don’t think that we are likely to do any business either. Good day.’

‘Dog dung!’ softly spat out Mr Joolby as the shop door closed on their departing footsteps.

CHAPTER III (#ue3c5f5fd-c71d-5209-8205-95fefb4474d5)

MR BRONSKY HAS MISGIVINGS

AS Mr Carrados and Parkinson left the shop they startled a little group of street children who after the habit of their kind were whispering together, giggling, pushing one another about, screaming mysterious taunts, comparing sores and amusing themselves in the unaccountable but perfectly satisfactory manner of street childhood. Reassured by the harmless appearance of the two intruders the impulse of panic at once passed and a couple of the most precocious little girls went even so far as to smile up at the strangers. More remarkable still, although Parkinson felt constrained by his imperviable dignity to look away, Mr Carrados unerringly returned the innocent greeting.

This incident entailed a break in which the appearance of the visitors, their position in life, place of residence, object in coming and the probable amount of money possessed by each were frankly canvassed, but when that source of entertainment failed the band fell back on what had been their stock game at the moment of interruption. This apparently consisted in daring one another to do various things and in backing out of the contest when the challenge was reciprocated. At last, however, one small maiden, spurred to desperation by repeated ‘dares’, after imploring the others to watch her do it, crept up the step of Mr Joolby’s shop, cautiously pushed open the door and standing well inside (the essence of the test as laid down), chanted in the peculiarly irritating sing-song of her tribe:

‘Toady, toady Jewlicks;

Crawls about on two sticks.

Toady, toady—’

‘Makee go away,’ called out Won Chou from his post, and this not being at once effective he advanced towards the door with a mildly threatening gesture. ‘Makee go much quickly, littee cow-child. Shall do if not gone is.’

The young imp had been prepared for immediate flight the instant anyone appeared, but for some reason Won Chou’s not very aggressive behest must have conveyed a peculiarly galling insult for its effect was to transform the wary gamin into a bristling little spitfire, who hurled back the accumulated scandal of the quarter.

‘’Ere, don’t you call me a cow-child, you ’eathen swine,’ she shrilled, standing her ground pugnaciously. ‘Pig-tail!’ And as Won Chou, conscious of his disadvantage in such an encounter, advanced: ‘Oo made the puppy pie? Oo et Jimmy ’Iggs’s white mice? Oo lives on black beetles? Oo pinched the yaller duck and—’ but at this intriguing point, being suddenly precipitated further into the shop by a mischievous child behind, and honour being fully satisfied by now, she dodged out again and rejoined the fleeing band which was retiring down the street to a noisy accompaniment of feigned alarm, squiggles of meaningless laughter, and the diminishing chant of:

‘Toady, toady Jewlicks;

Goes abaht on two sticks.

Toady, toady—’

Sadly conscious of the inadequacy of his control in a land where for so slight a matter as a clouted child an indignant mother would as soon pull his pig-tail out as look, Won Chou continued his progress in order to close the door. There, however, he came face to face with a stout, consequential gentleman whose presence, opulent complexion, ample beard and slightly alien cut of clothes would have suggested a foreign source even without the ruffled: ‘Tevils! tevils! little tevils!’ drawn from the portly visitor as the result of his somewhat undignified collision with the flying rabble.

‘Plenty childrens,’ remarked Won Chou, agreeably conversational. ‘Makee go much quickly now is.’

‘Little tevils,’ repeated the annoyed visitor, still dusting various sections of his resplendent attire to remove the last traces of infantile contamination. ‘Comrade Joolby is at home? He would expect me.’

‘Make come in,’ invited Won Chou. ‘Him belong say plaps you is blimby.’

‘The little tevils need control. They shall have when—’ grumbled the newcomer, brought back to his grievance by the discovery of a glutinous patch marring an immaculate waistcoat. ‘However, that is not your fault, Won Chou,’ and being now within the shop and away from possibly derisive comment, he kissed the attendant sketchily on each cheek. ‘Peace, little oppressed brother!’

Not apparently inordinately gratified by this act of condescension, Won Chou crossed the shop and pushing open the inner door announced the new arrival to anyone beyond in his usual characteristic lingo:

‘Comlade Blonsky come this side.’

‘Shall I to him go through?’ inquired Mr Bronsky, bustling with activity, but having already correctly interpreted the sounds from that direction Won Chou indicated the position by the sufficient remark: ‘Him will. You is,’ and withdrew into a further period of introspection.

In the sacred cause of universal brotherhood comrade Bronsky knew no boundaries and he hastened forward to meet Mr Joolby with the same fraternal greeting already bestowed on Won Chou, forgetting for the moment what sort of man he was about to encounter. The reminder was sharp and revolting: his outstretched arms dropped to his sides and he turned, affecting to be taken with some object in the shop until he could recompose his agitated faculties. Joolby’s slit-like mouth lengthened into the ghost of an enigmatical grin as he recognised the awkwardness of the comrade’s position.

Bronsky, for his part, felt that he must say something exceptional to pass off the unfortunate situation and he fell back on a highly coloured account of the derangement he had just suffered through being charged and buffeted by a mob of ‘little tevils’—an encounter so upsetting that even yet he scarcely knew which way up he was standing. Any irregularity of his salutation having thus been neatly accounted for he shook Joolby’s two hands with accumulated warmness and expressed an inordinate pleasure in the meeting.

‘But I am forgetting, comrade,’ he broke off from these amiable courtesies when the indiscretion might be deemed sufficiently expiated; ‘those sticky little bastads drove everything from my mind until I just remember. I met two men further off and from what I could see at the distance they seemed to have come out from here?’

‘There were a couple of men here a few minutes ago,’ agreed Mr Joolby. ‘What about it, comrade?’

‘I appear to recognise the look of one, but for life of me I cannot get him. Do you know them, comrade Joolby?’

‘Not from Mahomet. Said his name was Carrados—his nibs. The other was a flunkey.’

‘Max Carrados!’ exclaimed Mr Bronsky with startled enlightenment. ‘What in name of tevil was he doing here in your shop, Joolby?’

‘Wasting his time,’ was the indifferent reply. ‘My time also.’

‘Do you not believe it,’ retorted Bronsky emphatically. ‘He never waste his time, that man. Julian Joolby, do you not realise who has been here with you?’

‘Never heard of him in my life before. Never want to again either.’