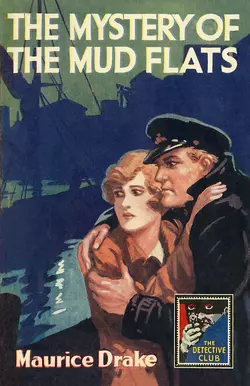

The Mystery of the Mud Flats

Maurice Drake

Nigel Moss

The latest in a new series of classic detective stories from the vaults of HarperCollins is a thrilling mystery concerning twentieth-century pirates smuggling secret cargo across the English Channel.James Carthew-West, the penniless skipper of the Exmouth coasting vessel Luck and Charity, is chartered by a rich trader to carry unprofitable cargo to Flanders through the treacherous shallows of the Scheldt estuary and return with worthless mud ballast. His crewman Austin Voodgt, a former investigative journalist, is intent on revealing the true conspiracy behind this bizarre trade, but with each new discovery comes the growing realisation that there are lives at stake – beginning with their own.The Mystery of the Mud Flats, first published as WO2, was considered one of the most thrilling adventure stories of its time, combining a first-class mystery with the eternal lure of the sea. Introducing the Dutch maritime detective Austin Voogdt (later dubbed ‘Sherlock of the Sea’), and with its unique English Channel setting, this story of intrepid yachtsmen caught up in smuggling, espionage, and the growing menace of Germany as a military power, made truly exciting reading.This Detective Club classic is introduced by Nigel Moss, who explores how Maurice Drake’s popular seafaring novel epitomised pre-war ‘invasion literature’ and helped usher in a new genre of adventure spy fiction.

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#ulink_3471c94b-7186-590c-ae9b-ea8f5087061c)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain as WO2 by Methuen & Co. 1913

Published as The Mystery of the Mud Flats by The Detective Story Club Ltd for W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1930

Introduction © Nigel Moss 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2018

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008168926

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9780008137311

Version: 2017-11-17

Contents

Cover (#u9a589378-98bd-5ada-a6bc-51e2dd9dbd1f)

Title Page (#u9499b1bc-6800-55d0-ba25-5db583a829e2)

Copyright (#u71c219a9-0631-5c99-aa4e-8906e6f96dd7)

Introduction (#u2be88033-8a6c-5058-9bfb-f970e719b37b)

I. CONCERNING A FOOL AND HIS MONEY

II. CONCERNING A STROKE OF GOOD LUCK AND AN ACT OF CHARITY

III. CONCERNING A COMPANY OF MERCHANT ADVENTURERS

IV. CONCERNING A CARGO OF POTATOES

V. IN THE MATTER OF A DESERTING SEAMAN

VI. OF A PRODIGAL’S RETURN

VII. CONCERNING A PENALTY FOR CURIOSITY

VIII. FURTHER RESULTS OF CURIOSITY

IX. OF CURIOSITY REWARDED

X. OF A PARTNERSHIP IN CRIME

XI. OF A LADYLIKE YOUNG PERSON

XII. CONCERNING THE ETHICS OF PARTNERSHIP

XIII. SHOWING A FOWLER IN HIS SNARE

XIV. OF A DIRECTORS’ MEETING

XV. CONCERNING MODERN MAIDENHOOD

XVI. OF A CONVIVIAL GATHERING

XVII. VOOGDT DESERTS AGAIN

XVIII. OF A NONDESCRIPT CREW

XIX. WHICH TELLS OF A WILD-GOOSE CHASE

XX. OF A DISSOLUTION OF PARTNERSHIP

XXI. OF COLLISIONS AT SEA

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_414b9eb3-7af6-5612-bd2f-8d4e3e9cc7d9)

MAURICE DRAKE’s more enduring legacy to date has been as a leading artist in glass painting and eminent authority on medieval stained glass, working in the early twentieth century. By contrast, his fictional writings and reputation as an author of seven popular novels, originally published between 1906 and 1924, have been largely neglected. This new release of the Collins Detective Story Club edition of The Mystery of the Mud Flats (1930), the first in 88 years, provides an opportunity to appraise Drake’s most successful novel, alongside his other works; also, to reflect on his place within the Edwardian high adventure story genre, and to look more broadly at his influence on later authors of nautically themed mystery and espionage thrillers.

Born in 1875 in Newton Abbot, Devon, Frederick Morris Drake—better known by his pseudonym Maurice Drake—was educated at Teignmouth Grammar School. Along with his brother Wilfred, Maurice Drake represented the fourth generation of a famous glass painting family in Exeter, originally established by his great-uncle. He married Alice Wilson in 1897.The family home and glass painting studio were close to Exeter Cathedral, and he was an advisor to the Cathedral authorities on stained glass—a role to which his daughter succeeded him following his death. Maurice’s best known art publications, which have become leading works in their field, are A History of English Glass-painting (1912) and Saints and their Emblems (1916), both co-authored with Wilfred. He was retained by leading museums and became a renowned lecturer and expert advisor on old stained glass, travelling widely in the UK, Continental Europe and USA.

During WW1, Maurice served both with the Infantry and the RAF. In the early 1920s, he resumed his writing career, but in April 1923 died prematurely from pneumonia at the age of 48. It was the same year that saw the publication of his first novel since the Great War.

A popular British circulating magazine of 1913 described Drake as ‘a big, brawny, moustached sunburned man … who looks what he is … an ardent amateur yachtsman. Everything in connection with the sea interests him, and it was this love for salt-water that led him, some seven years ago, to try his hand at a novel about life on the ocean wave.’

In The Mystery of the Mud Flats (also known as WO2), Drake’s fourth novel, the sea and life aboard boats feature constantly. It proved to be his best-selling and best-received novel. Originally published by Methuen in 1913 under the curious title WO2 (the chemical formula of the valuable substance at the heart of the plot), it was also released in the USA and Canada that year under the same title. Acclaim from reviewers and popular commercial success swiftly followed on both sides of the Atlantic; between 1913 and 1930 the book was published in 26 editions world-wide and in three languages. When Collins acquired the publication rights in 1930 for its Detective Story Club imprint, the title was changed to the more accessible (and thrilling) The Mystery of the Mud Flats, and subtitled ‘A Story of Crime’. Interestingly, in 1913, the UK first edition of WO2 was subtitled ‘A Novel’; and the US first edition ‘A Story of Romantic Adventure’. The later change of subtitle in 1930 reflects the rapid growth in popularity of crime stories during the intervening period. By then, the ‘Golden Age’ of mystery fiction was well under way.

Upon the book’s original publication in 1913, the New York Times reflected on the market being flooded with tales of romance, adventure and melodrama, of which few could be classed as literature. While lamenting a lack of authors of the calibre of Dumas, Scott or Stevenson, it was nonetheless sufficiently impressed by WO2 to comment that it represented ‘a rift in the dark outlook for romance in a day of clinical novels and potboilers. The author … is on the right track, and his book is so far above the average hotchpotch of remarkable and incongruous events as to deserve special comment. WO2 is a stirring tale of illicit sea-faring, full of open air thrill … a rattling good yarn, and stands well to the front among books of its kind.’ Scribners magazine applauded the ingenious plot and originality in characterisation. The Nation reviewer concluded: ‘It is not often that detective work, vagabond adventure and love-making are more pleasantly mingled’.

WO2 or The Mystery of the Mud Flats is a model of the Edwardian high adventure story—the tropes of thrills, heroism, mystery and romance are all present in good measure. It blends a mix of themes: a full-blooded, lively paced adventure story with an original and unusual plot and a varied and interesting group of characters; illicit smuggling; gripping and dangerous espionage activity; exciting action at sea, with plenty of sailing detail and sea-faring dialogue; wonderfully descriptive writing, especially of the Dutch Scheldt coastal locations, and evoking life at sea often in bleak conditions; a non-intrusive love interest involving a young woman with thoroughly modern ideas; and, written only a year before WW1, there is a clear foreboding of the growing menace of Germany as a military power. The story is narrated in the first person throughout, and the writing is direct, crisp and terse.

The narrator is James Carthew-West, a fiercely independent, educated young man from an upper middle-class background, whose reading interests include Marcus Aurelius, Balzac and Henry James. He has a consuming passion for the sea, and when we meet him is already an experienced and well-travelled seaman, the owner and skipper of a coasting ketch Luck and Charity, moored in Exmouth harbour. While resourceful and capable, Carthew-West is also prone to periods of idleness and impecuniosity. In the book’s vivid opening passages he is found at a particularly low point: destitute, hung-over, unwashed and unkempt, having slept out on a beach all night—‘I woke on Exmouth beach that early summer morning much as I should think a doomed soul might wake, Resurrection Day’. But Carthew-West’s ill-fortune is about to change for the better. His reverie is rudely disturbed by a young lady, Pamela Brand. A sparky personal chemistry between the two quickly develops. His initial views about Pamela being ‘a sexless little guttersnipe’ and ‘viper tongued’, and her corresponding disgust with his wasted life, gradually give way to a mutual love interest as the story progresses. Pamela is likewise a strongly independent character. She holds a BSc, and is an enthusiastic supporter of the suffragette movement, with forthright views on the role of women in society; very much a modern woman for her time.

Pamela introduces Carthew-West to her business partner, Leonard Ward, formerly an eminent Chemistry professor, now running Axel Trading Company which ships various goods between English ports and the Scheldt delta in the Dutch low countries. Ward is impressed with Luck and Charity as a shallow coasting vessel, ideally suited to navigate the waters of the Scheldt, and he charters the boat, along with Carthew-West and crew, on exceptionally generous financial terms. Axel’s base is in the Scheldt at Terneuzen, located at the entrance to the Ghent ship canal, close to the mouth of the river. Drake’s descriptions of the locale and setting are masterly—vivid and atmospheric, yet pared down and succinct (mud flats have rarely appeared so attractive!)

Prior to embarkation from Exmouth with the first shipment for Terneuzen, Drake introduces another central protagonist, Austin Voogdt. His initial appearance is comedic; one reviewer colourfully described him as resembling a debonair tramp. But this is no ordinary tramp. Of Dutch descent, Voogdt was previously an independent investigative journalist working for London newspapers, who swapped city life for the open road and exercise after being diagnosed with TB. Carthew-West takes to Voogdt, and hires him to work as a crew member on Luck and Charity. Upon reaching Terneuzen, they encounter Axel Trading’s local representative, Willis Cheyne. He is a cousin of Pamela and fellow partner in the business; a secretive young man, with a volatile temper and unpleasant nature, prone to drink and gambling. Unsurprisingly, he later turns out to be dishonest and untrustworthy.

The charter operation runs smoothly and is financially rewarding for Carthew-West. But the trade is not all it seems. The cargoes delivered to Terneuzen are invariably loss-making, and the mud ballast brought back to England is apparently worthless. Yet Voogdt discovers that Ward and his partners have become extremely affluent of late. Increasingly perplexed, and with his investigative traits coming to the fore, Voogdt resolves to uncover the puzzle and find out what is really going on. At the same time, a German company begins setting up operations in Terneuzen, close to Axel Trading. Headed by its manager Van Noppen, its business is conducted secretively; initially thought to be fertiliser, then later explosives. But the Germans too exhibit a keen interest in the mud flats.

Voogdt displays talents and abilities more akin to a secret service agent than a journalist. Why does he initially disguise his true persona from Willis Cheyne and Van Noppen? How does he gain access to firearms at short notice, and what of his relationship with shadowy agents who look to him so admiringly as their leader in action? The allusion to British secret service connections is there, but ultimately Drake opts to keep Voogdt as an investigative journalist, motivated primarily by financial gain, rather than by national interest (although the latter is certainly served).

Stories dominated by sea adventures are at the heart of five out of Drake’s seven novels. His knowledge and experience of sailing gives the books an authenticity which enhances their quality. The first, The Salving of a Derelict (1906), also known by its US title The Coming Back of Lawrence Averil, won a Daily Mail prize of £100 in 1906 for best story by a new writer (out of 600 manuscripts submitted). It sold well both in the UK and USA, and quickly established Drake as a popular adventure novelist. Lawrence Averil is the ‘derelict’ in the story’s title, an Oxford-educated young man from a well-to-do family; inclined to the sea from childhood. He is fond of the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and in particular ‘Heroism’ (apt, given the plot’s development). Following the shock of his father’s suicide after the discovery of financial embezzlement, Averil is offered a lifeline by one of his father’s victims to work on a fishing trawler in the North Sea. Life at sea proves arduous and dangerous, as much from the hostility of other crew members as the bleak hardship of the natural elements. The challenges to Averil’s character are formidable, and he is pushed to the limits. Ultimately, the ‘derelict’ proves himself, encouraged by the daughter of his boss, a modern, self-possessed London newspaper woman. There are clear parallels between the characters and personalities of Lawrence Averil and James Carthew-West (of WO2), as well as their respective female partners. Also, one of Averil’s crew members subsequently appears in WO2, working for Carthew-West on Luck and Charity.

Salvage appears again in Drake’s second sea novel Wrack (1910), but this time in its nautical form. A young naval officer, incapacitated from service early in his career, turns to salvage work at sea. The nature of salvage operations, with its risks and chances, is graphically described. The hero’s efforts prove increasingly successful and highly rewarding; there is also a promising romance interest in the background. However, the story takes an unexpected dark twist following a fateful discovery, and subsequent emotional turmoil and tragedy overtake the previous happiness and good fortune of the protagonist.

In between these two sea adventures, Drake wrote Lethbridge of the Moor (1908). Set in Exmouth and Dartmoor, the story concerns the unfortunate and cruel consequences for the young hero, George Lethbridge, of an unpremeditated act, out of character, which causes injury to a gamekeeper during a foolhardy poaching expedition. Lethbridge is sentenced to five years’ penal servitude. The remainder of the story focuses on the hardship of prison life and the misfortunes he suffers. The sensitive character of Lethbridge is sympathetically drawn. During his incarceration, Lethbridge displays admirable qualities of fortitude and stoicism, and commits acts of selfless virtue towards other inmates. A love interest also develops involving the wife of a fellow prisoner. The novel was praised by reviewers for its good and clear literary style, vivid description of Dartmoor scenery, and restrained yet forceful romance.

The popular success of WO2 in 1913 led Drake to write a sequel. The follow-up novel was The Ocean Sleuth (1915), another sea adventure mystery and featuring the same main protagonists as in WO2. The sleuth is Austin Voogdt, now styled ‘Sherlock of the Sea’. The newly married James Carthew-West and his wife Pamela also appear in the story, but only peripherally. Voogdt, the maritime detective, is the hero of the story. The plot is strong, exciting and fast-paced; but different in many ways from Drake’s previous books. An absconding financier with £80,000 in notes is supposedly drowned at sea, after a foreign liner breaks up on rocks off the Lizard in Cornwall. Subsequently, many of the notes reappear as forgeries. At one point, there is an exchange of batches of real and counterfeit notes aboard a train in the Parsons tunnel at Dawlish. Spurred on by his love interest in a female suspect, Voogdt hunts down the real notes and solves the mystery. Both WO2 and The Ocean Sleuth were sufficiently popular to be serialised in leading British adventure story magazines in their respective years of publication.

After military service in WW1, Drake returned to his writing career in the early 1920s. His penultimate novel The Doom Window (1923) was released in the same year as his death. An interesting and unusual story, concerned with the forgery of old glass specimens. The protagonist is with a firm of glass painters in Shrewsbury, and the plot centres on the famous ‘Doom Window’ of a local church. Like Drake, the hero is an expert in judging and making stained glass, and the book includes plenty of technical detail about its manufacture, as well as the ins and outs of the business. The blurb of the US first edition refers to the story being ‘as colorful as the stained glass around which its plot turns’. The Saturday Review was particularly admiring of the scenes which describe the effect on the hero of his first visit to New York, where he visits as a consulting expert, and how he views all sorts of city life there through eyes fresh from an English cathedral town. We know Drake had himself made such a trip to New York to value a collection of old glass, and he will likely have drawn on his personal experiences when writing these descriptive passages.

Drake’s final novel Galleon Gold (1924) was published posthumously in the year after his death. Fittingly a nautical story, this time set in the Hebridean Islands, it is an exciting and realistic sea adventure of mixed fortunes, complete with discreet romance element. The plot concerns the search for, and tracing of, lost galleons and gold. It particularly brings to mind George Birmingham’s popular novel Spanish Gold (1908), which features treasure hunting off the west coast of Ireland.

While WO2 lies squarely within the Edwardian high adventure tradition, it has a wider literary significance. There are parallels with the classic boating thriller The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers, regarded as one of the finest early secret service stories of literary distinction (alongside Kim by Rudyard Kipling, published the year before). This well-drawn, exciting story of amateur espionage, involving two contrasting young male protagonists sailing in the Baltic and Frisian Islands who stumble across pre-invasion manoeuvres by the German navy, was prescient in calling attention to Germany as a potential threat to Britain, especially at a time (pre-Entente Cordiale) when France was perceived as the nation’s principal enemy. WO2, with its allusions to Germany’s international subterfuge and developing armaments programme, was published in the year leading up to WW1. It forms part of the small but influential body of fiction dubbed ‘invasion literature’, alongside The Riddle of the Sands and The Invasion of 1910 by William Le Quex, published in 1906. All were stories with a purpose, written from patriotic leanings, and intended to raise public awareness of the threat of war with Germany and call for preparedness. Together, they provide an interesting insight into pre-WW1 British perceptions.

These novels were precursors to the adventure spy fiction of John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), Conan Doyle’s His Last Bow (1917) and E. Phillips Oppenheim’s The Great Impersonation (1920)—all involving the rounding-up of German spy gangs at the outbreak of WW1. This influence carried over to WW2. A. G. MacDonell’s The Crew of the Anaconda (1940) is in the same vein; it features the tracking down of German spies by the owner of a motor cruiser and his friends in the early days of WW2. It continues the literary association between small boats and international conspiracy threats, in the tradition of The Riddle of the Sands and WO2. One commentator has described The Crew of the Anaconda as a kind of WW2 equivalent to The Thirty-Nine Steps. Other espionage adventure thrillers with a nautical flavour from that period include Hammond Innes’ Wreckers Must Breathe (1940), featuring the Cornish coastline, disused tin mines and a secret U-boat base; also John Ferguson’s Terror on the Island (1942), which involves abstracting an invention from Germany prior to the outbreak of WW2.

R. Austin Freeman’s The Shadow of the Wolf (1925) is a tale involving the forgery of banknotes and murder on board a yacht off Wolf Rock in Cornwall. There is a significant boating influence in several thrillers by A. E. W. Mason, including The Dean’s Elbow (1930), and The House in Lordship Lane (1946) featuring Inspector Hanaud. Mason was himself a secret agent in WW1, as well as a keen yachtsman. One thinks also of various sea mysteries of the 1930s, including those by Taffrail (Captain Taprell Dorling—‘the Marryat of the modern Navy’) such as Mid-Atlantic (1936), John Remenham’s Sea Gold (1930), John C. Woodiwiss’s Mouseback (1939), Peter Drax’s High Seas Murder (1939) and Ernest McReay’s Murder at Eight Bells (1939). Later, a strong nautical theme can be seen in the novels of Andrew Garve, for example The Megstone Plot (1956) and A Hero for Leanda (1959); Edward Young’s espionage thriller The Fifth Passenger (1963); as well as several boating thrillers by J. R. L. Anderson, including Death in the North Sea (1975) from the series featuring Colonel Peter Blair, and Redundancy Pay (1976), also known as Death in the Channel.

Maurice Drake’s influence can also be seen in some of the sea mysteries of famous Golden Age detection writer Freeman Wills Crofts. The Golden Age commentator Curtis Evans has noted that Crofts was a great admirer of Drake’s sea adventure stories, and interestingly maintains he borrowed the surname of Maxwell Cheyne, the protagonist of Inspector French and the Cheyne Mystery (1926), from Willis Cheyne in WO2. There are similarities too between Joan Merrill, the heroine of Crofts’ story and Pamela Brand in WO2. Both stories feature Dartmouth harbour in their plots. Crofts’ earlier novel The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922) also displays the influence of The Riddle of the Sands and WO2. It centres on investigations by amateur sleuths into illicit smuggling activities, using boats ferrying pit props which sail from the Bordeaux coast canals across to the Humber Estuary.

Time now to rediscover and enjoy afresh the exciting adventures of sea-farers James Carthew-West and Austin Voogdt, as they tackle the strange mystery of the mud flats at Terneuzen, amid increasing dangers to themselves, and against a backdrop of the looming shadow of international conflict.

NIGEL MOSS

September 2017

CHAPTER I (#u72d37d7f-e1e6-566a-864a-7cb6ca23ca90)

CONCERNING A FOOL AND HIS MONEY (#u72d37d7f-e1e6-566a-864a-7cb6ca23ca90)

I WOKE on Exmouth beach that early summer morning much as I should think a doomed soul might wake, Resurrection Day. To the southward rosy, sunlit cliffs showed through faint haze like great opals—like the Gates of Pearl—and the bright business of getting-up was going on all around. Hard by the slimy piles of the wooden pier, in a corner tainted by rotting seaweed and dead shell-fish, I came slowly to consciousness, my eyes clogged and aching, a foul taste in my mouth, and in my mind lurking uneasiness as of a judgment to come. And lying out all night on dewy shingle had made me stiff in every joint, and sore as though I had been beaten all over with a stick.

The young day was one of heaven’s own, all blue and gold. The two men whose crunching feet upon the shingle had roused me were aboard the dinghy that had been mine twelve hours before—my Royal Torbay burgee still fluttering gaily at her masthead. Her new owner was swabbing dew from off her seats, pointing out her merits to his companion the while. He spoke of me, a thumb jerked over one shoulder to show where I lay upon the beach. ‘That there West’—the wind brought me that much; that, and a scornful laugh from the other. The whole bright day seemed laughing at me in derision, and I dropped my arms upon my face again and tried to get another hour of forgetfulness. I was at the bottom end of things. Poor comfort to reflect that I only had myself to blame.

I’d been on my uppers once before, at Kingston, in Jamaica, just after the earthquake; but I was fit then, with a clear conscience, and there was plenty to do. Now, with two years of idling and folly to my discredit, I only had the sore knowledge of chances thrown away. Besides, the past winter had tried me hard: poverty and loneliness and the sight of one’s property slipping away day by day make a man ripe for any foolishness by way of a change. Only the day before I’d parted with the dinghy, almost my last asset, and now, on the morrow, the price didn’t seem good enough. A rotten waterman’s tub, scarcely seaworthy, in part exchange; a couple of pound’s worth of loose silver in my pocket. And worst of all was the uncertainty as to what I should do next.

There had been no uncertainty at Kingston. There were more jobs there than men to do them, and I took the first that offered and did right well out of it. I had been with the Deutsche-West-Indie people till then, third mate on their Oldenburg, and we got into Kingston harbour the day after the town tumbled about the folk’s ears. Trier, our skipper, did the right sort of thing—called at the Consulate and offered free passages out of the place to as many Germans as he could carry, and so on—and then, having done what he considered his duty, was all for the sea again. But I wouldn’t go. Able-bodied whites were badly wanted ashore. Rescue parties were busy; there was a fearful mess to tidy up everywhere; there had been some bad cases of looting, and people were afraid the niggers would get out of hand.

My word, but that was work, that relief business! Awful, a lot of it—ghastly; but I don’t know when I enjoyed myself so much in my life. There were still lots of people alive and buried in the ruins, and we had to get them out. At first I was in a mixed lot of whites and blacks and yellows; and they were a mixture, too! Our foreman was a full-blooded nigger carpenter, a fine chap, a devil to work, and as strong as a bull. We had two doctors, one of ’em off a Japanese man-o’-war in harbour and the other a visitor—a tourist. Their head assistant was another tourist, a woman, wife of a vicar in Lancashire when she was at home; but she’d been a hospital nurse, and she pitched in, like the rest of us. There were nine or ten American sailors, and three of them wouldn’t speak to us English. There had been some fuss with our governor, who had declined the services of the American battleships’ crews, I believe, and they were wild as hawks about it. Dozens of them had sneaked ashore to help, the officers winking at it. One of our three must have known something about permanent deserting unless he’d picked up his Cockney accent in the States. They were good men, those three, and the Cockney wasn’t the worst of ’em. Then there was the son of the Mayor of Kingston and a yellow-bearded Finnish ship’s cook and a Chinese laundryman. Those were all the notabilities. The rank and file were niggers, some of them women.

After a week there weren’t any more of the living imprisoned, and we had to attend to the dead. Faugh! In the tropics. Awful! They broke our gang up and put the mayor’s son and myself in charge of another lot digging out bodies and burning them. The mayor’s son didn’t work up to his collar, I considered. So we had words about it, and he went off with his nose in the air. To do the chap justice, I think now he only meant to go a hundred yards and come back again, but I hadn’t time to think of that then, so I hove a half-brick at him and shouted to him to go to Hades. The brick got him in the back of the knee and brought him down in the road, and I sent a nigger to drag him into the shade and went on with the work. When I went to look for him he had cleared, and I never saw him again, but I fancy the incident had a good deal to do with my being left severely alone after things were tidy once more.

When the land breeze had blown the smoke of the last hideous burning away out to sea I was on my beam-ends, so I cabled the governor: ‘Detained here for want of funds.’ I might as well have saved my money, for I ought to have known what the reply would be. ‘Capital experience. Pitch in and earn some, my son,’ he cabled back.

A hard case, my old man. That’s him all over. Nobody else in the world would have paid for those two unnecessary words at the end, just to show it wasn’t because he was short of cash that he wouldn’t help me.

The relief gangs had broken up and the sailors and most of the tourists departed—and there was I in a suit of rags, my hair about four inches long, and not a notion of what to do next. It was the long hair decided me, I think. I hunted up my nigger carpenter and got him to build me a little lean-to shack against the ruins of the Presbyterian church, promising to pay him when I could. Then I got a sheet of tin, painted a gaudy Chinese dragon on it with the words:

PROF. WATSON

TATTOOING ARTIST

and nailed it up over my door. I copied the dragon from the cover of a packet of Chinese crackers that was blowing about on a rubbish heap, and tattooing anybody can do, if they’ve got the sense to keep their needles clean.

As luck would have it, I hadn’t long to wait for customers. In fact I was busy from the first day. When the shipping began to ply regularly again there were heaps of tourists to see the ruined town, and lots of them came to be tattooed as a souvenir of their visit. One chap gave me a photo of my shack, with me outside it at work on a sailor’s arm. I begged the negative of him, had a few hundreds printed as postcards, and used to make a shilling apiece out of them. Things just boomed. I paid my carpenter and set him at work on a little frame house in a plot I hired, and when it was done I shifted my sign there and settled down to business in earnest. Then I got an assistant—a young Japanese from a sailing ship that had been wrecked on Culebra, in the Virgin Islands. He really was an artist, that chap, and his work put me out of conceit with my own botching. So after two years I sold him the house and business, lock, stock and barrel, and cleared out for home. As a souvenir he did a bit of his best work on my chest whilst I was waiting for my steamer. A lovely bit of tattooing it is: a masterpiece, an eagle holding a fish.

I landed in Plymouth with about six hundred pounds in my pocket, and knocked it down in two years. Lazy, lovely South Devon held me. I was fool enough to let the old man’s cablegram rankle, and I never went near him—just sent him a card to say where I was, which he answered with another, and that’s all the communication we held with one another. I loafed about from one place to another, idling, drinking more than was any use to me, and generally wasting my time. I’d earned six hundred pounds as easily as falling off a log, and thought it would be easy enough to earn another lot when that was gone.

There’s a class of man common on the south coast of England, and especially in Devonshire, who is no manner of use to himself or anybody else. The natives call them remittance men, and that exactly describes them. They’re idlers, mostly sons of busy professional men or manufacturers in London, the Midlands or the north. They idle more or less gracefully; they go fishing and sail small boats, or get drunk and sleep in the sun. They’re very little use to anybody, as I’ve said already, and I wouldn’t mention them if I hadn’t lived with them—been one of them, if you like. They were my only associates for two years, and they and sleepy South Devon brought me down to sleeping out on Exmouth beach.

It was just after Christmas when I landed at Plymouth, and by the spring I’d got tired of messing about and fuddling in a garrison town and thought I’d like a bit of sailing for the summer. Of course every waster I’d picked up with knew of the very boat that would suit me, and I should think I inspected half the rotten tubs in Devon and Cornwall before I found the packet I wanted.

I only heard of her by accident. A boat-builder at Yealmpton had built her as an experiment to the order of his brother-in-law, who was a fisherman in the Brixham fleet. The brother-in-law—a man with more notions in his head than money in his pocket—had died bankrupt before his boat was rigged, and the Yealmpton man had her left on his hands, and half the south Devon coast was laughing at him, for it appeared she was useless to anybody, being the wrong build for a trawler and too small for a coasting boat.

I went over and saw her one Saturday afternoon and fell in love with her on the spot. Her hold, too small for freights, was amply big enough for me, and besides it left more cabin room at each end of her. She was a beauty, to my thinking; a good, beamy boat, not too deep in draught, and built like a house. The builder, normally an honest man, in building for his sister’s husband had put real good stuff into the boat. The day I was there two other fellows had come down from Brixham to see her and were jeering at her, to cheapen her, I suppose. The builder was raving her praises, and I got into his good graces at once by speaking the truth, saying that she was a well-built craft, honest material and honest work in her.

That was the way to tackle the man, for he’d put his heart into her timbers. The other two sheered off and I bought her, hull and masts only, as she stood, for a hundred and ten pounds, and she was dirt cheap at the price. For another hundred he rigged her, fisherman fashion, rough hard gear throughout to stand any weather, divided her hold with cheap matchboard bulkheads into a saloon with two cabins, and decked over her hatch with four skylights. And I got to sea with her, well-pleased, before the middle of June.

Brett had named her the Luck and Charity, of all outlandish names, but I didn’t bother to change it. Sure enough she brought me luck in the end—the best of luck—and at first she was a charity to the fraternity of wasters, and no mistake.

With her hold turned into cabins she was a very roomy packet. Though she was only forty-five feet or so between the perpendiculars, she was fifteen in the beam, every inch. There was a little skipper’s cabin aft, about twelve feet by nine, with just head-room enough to stand upright, two bunks and a flap table; the big square hatch we decked over was about eight feet by thirteen, and there was a roomy forepeak—almost fit to be called a forecastle—with two bunks on each side. Altogether we could shake down ten men without crowding, though I’ve often slept fifteen aboard, the extra members of the family sleeping on the cabin seats or on the floor.

It was an idle time, those two years, but past question I enjoyed it. The wasters were delighted, of course, and I was the dearest old chappie in the west of England whilst funds lasted. It worked out about level, though; they had cheap quarters and I had a cheap crew, so everybody was pleased. We put to sea or stayed on moorings just as the weather served or the whim took us, so mostly we had fair-weather cruising. Ashore, there was plenty of company. There’s a freemasonry of sorts amongst remittance men: they snarl behind each other’s backs pretty much, but can unite upon occasion. I happened to be the occasion this time, and there was plenty of visiting, and card-playing, and fuddling, and remarkably mixed company whenever we went ashore to revel.

The first winter I tied her up in Teignmouth harbour and lived ashore, and when the spring came started off again. Not being built for a yacht the Luck and Charity wanted a lot of ballast, but she wasn’t too deep for getting in and out of those little west of England harbours, and by the end of the second summer I knew the coast from Swanage to Land’s End like the back of my hand. And very useful knowledge it has proved to be since then.

It didn’t seem so useful, though, when I came to tie up for the second winter. I chose Exmouth Bight for anchorage this time. You can’t play the fool without spending money and I was cleaned out down to the last fiver. Exmouth is a free harbour—no dues unless you go into dock—and so Exmouth looked the place for me. The winter before I’d had plenty of invitations ashore, but this time the wasters had got wind of my circumstances and invitations were off. On the whole it seemed a cheerful prospect.

I kept my one paid hand hard at it, lowering topmasts and stripping gear, and, when the lot was snugged down for the winter, paid him off and told him to clear out and go home. He was a stolid shockhead from Topsham, called Hezekiah Pym. The wasters used to laugh at him, and certainly he was the quaintest sample of a yachtsman I ever met. But he might have been born on the water, so handy was he afloat, and he had served my turn so well that I felt sorry to part with him. I had to pawn my watch to make up the money I owed him, and even then it was a near thing. It was a real good watch that my father had given me when I was twenty-one; but the pawnbroker wouldn’t advance me more than the value of the gold case because, he said, the crest and motto engraved on it spoilt its sale value. The result was that when I’d made up ’Kiah’s money I hadn’t half-a-sovereign to my name.

When I paid him he looked first at the money and then inquiringly at me.

‘That’s a fortnight’s brass extra because you haven’t had notice,’ I told him.

‘Aw,’ said he, and put the money in his pocket. Then, as an afterthought: ‘What be yu gweyn t’ du fer th’ weenter, sir?’ he asked.

‘Stop aboard and catch flukes.’

‘Aw,’ said he again meditatively, and went ashore, leaving me to moralise on rats and sinking ships. But I did him an injustice for once.

Next morning he was aboard again before I was out, and brought me my breakfast in bed.

‘What brings you back?’ I asked.

‘Come back t’ catch flukes ’long o’ you,’ he said.

‘Look here,’ I said, ‘I’m broke, ’Kiah, and I can’t afford to keep you. So you just slip off to Topsham again, and get another job.’

‘What for?’ said the fool.

‘Because I’m broke.’

‘I thought you would be, mighty soon,’ he said slowly. ‘Yu been kippin’ all they lot tu long.’

Not once had I ever caught him in the slightest act of incivility all the time I’d had the boat, yet that was how he regarded my guests—‘Yas, sir’; ‘No, sir’; ‘Surely, sir.’ Never a word out of place; but that blinking, stolid lump had all the wasters sized up, all the time. Like their own bogs, South Devon men are. They smile and look tranquil, but you never know what’s under the surface. There’s good rocky ground in them to stand on, though, sometimes, if you’ve the knack of finding it.

After I’d had my breakfast I went forward and told him again I hadn’t a job or pay for him and he must go. He only said ‘Aw’ protestingly; and he didn’t go, and hasn’t gone to this day. He never alluded to the matter again except one day in mid-winter when we’d had a good haul of flukes and could spare some to send ashore to sell. Then he looked up from the loaded dinghy alongside, blowing on his half-frozen fingers.

‘Nort doin’ up to Topsham now,’ said he. ‘I’m better off yere’n what I should be ’ome.’

The winter came in wet and cold, and I nearly went melancholy mad with the sheer monotony of it. With each rising tide we swung our nose towards the harbour mouth and watched the water cover the mud-flats. At flood, we laid up or down or cross-channel before the wind and cursed the swinging round because it tangled our fishing lines. At ebb, our bows pointed up river and the mud-flats became uncovered again. We could only fish at dead water, flood or ebb, and between times we went to sleep or watched the scenery—dirty water or dirty mud, according to the state of the tide.

On the whole I can’t say I was pleased with that winter, and indeed it would take a man with queer tastes to admire wet mud-banks with the thermometer at freezing point, and wind and rain enough to keep you in the cabin for days on end.

Man cannot live on flukes alone, and to get bread and matches and paraffin—to say nothing of an occasional orgy on butcher’s meat—I began to sell the boat’s fittings. First the side-lights went, the spare anchor, the compass—things I thought I could replace cheaply or do without; but by early spring we were pretty well stripped—the fittings and bedding, from the cabins, the saloon table, crockery, spare rigging, any blessed thing that was detachable and had a market value. The saloon and cabins had relapsed to their original condition as hold, the matchboard partitions having been chopped up and burnt in the after-cabin stove, to save buying coal. The hold was a picture with its broken bulkheads jutting from the sides and the floor littered with driftwood and rubbish—anything we could pick up ashore that we thought would come in handy. A marine store dealer’s shop was a fool to it. To save keeping two stoves going ’Kiah came aft and shared my cabin. He never sulked or lost his temper or grumbled once all the winter, and though he never had a word to say for himself, he was company for me of a sort.

Lying on Exmouth beach the day after the dinghy had gone, not the least sore thought I had was that I’d spent money to which he had as much right as myself. I groaned aloud as I tried to get to sleep again, and as the sun rose and warmed my aching bones I fell into a uneasy doze that brought some short forgetfulness.

CHAPTER II (#u72d37d7f-e1e6-566a-864a-7cb6ca23ca90)

CONCERNING A STROKE OF GOOD LUCK AND AN ACT OF CHARITY (#u72d37d7f-e1e6-566a-864a-7cb6ca23ca90)

WITH the sun warming me, I must have slept for over an hour; but, lying face downwards as I was, even my dreams weren’t pleasant. I thought I had fallen overboard from the Luck and Charity, and rising half drowned under her stern called to ’Kiah for a rope. He was steering, but, instead of throwing me the mainsheet, he reached over a long arm, caught me by the side and pushed me under again. Drowning, I gulped salt water, and woke with a jerk, to find a girl standing over me prodding me in the side with her toe. Stupid with sleep, I rolled over and sat up, blinking to stare at her.

The sun, just over her head, dazzled my eyes so that I couldn’t clearly see her face; but from her get-up I judged her to be the usual type of summer visitor to the town. A big straw hat, a light blouse and dark skirt, and a bathing towel in one hand; but with the towel she held her shoes and stockings, and I saw that the foot that she had stirred me with was bare.

I asked her what she wanted, sulkily enough.

‘We want to go across the river.’ She pointed to the yellow sand-hills on the Warren side.

‘Well?’ I said.

‘There doesn’t seem to be a ferryman here. Don’t you want to earn a sixpence?’ Her tone was not conciliatory.

I looked down the beach. A man and woman stood by the waterside, but the boatmen had gone—to breakfast, I supposed. For a moment I was minded to tell her she must wait till they came back, but the thought of ’Kiah came into my mind. I owed it to him to make up what I could for the money I’d spent overnight.

‘I don’t expect my boat’s smart enough for you,’ I said, scrambling to my feet.

‘I didn’t expect anything lavish,’ she snapped; and at her tone I looked down over my clothes and passed a hand over my head and face. I didn’t look prosperous. One boot was broken at the toe, and my serge coat and trousers were stained with every shade of filth, from dry mud to tar, by the winter’s ’longshoring. I wore one of ’Kiah’s jerseys, Luck and Charity in dirty white letters across the breast. Bare headed, my hair was full of sand, and there was a fortnight’s growth on my cheeks. My razor, an elaborate safety fakement, had been sold early in the winter to get ’Kiah an oilskin jacket, and though I considered I had a right to shave with his, it was a right not often exercised. He’d inherited the thing from a grandfather who’d been in the army, and I didn’t share his high opinion of it. But in bright sunlight, with this girl staring at me, I wished I’d done so more recently.

The boat was in a state to match its owner. It couldn’t have had a coat of paint for two years, and to make matters worse the beach children had been playing in it and left it half full of pebbles, seaweed and sand. With the girl looking on, I started to clean out some of the rubbish, and the man and woman strolled along the water’s edge to join us. Feeling ashamed of myself and my shabby craft, I kept my head down and went on with my work till the man spoke.

‘An old boat?’ he said, civilly enough.

For an answer I mumbled some sort of assent.

‘Is she tight?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I only bought her yesterday. She’ll take us that far without sinking, I suppose.’

He said no more and we pushed off. The filthy tub leaked like a basket, of course, and the water was level with the bottom boards before we reached the Warren. I saw what was going to happen when we started, and rowed my hardest to get across before their feet were wet, but facing them I had time to look them over and see what sort of people my first customers were. The other woman was a beauty—a real beauty, of the big, placid type. She said very little on the way across, just trailing one hand in the cool water now and again, and listening to the talk of the others. The man struck me favourably. He was tall and gaunt, with a bit of a stoop in the shoulders. His clean-shaven face was sallow and he wore spectacles, which gave him the air of a student of sorts. His big square mouth was immovable as the slot in a post office, save for an occasional movement at the corners that seemed to hint at a laugh suppressed. A man you took to at sight: straight as a line, you could see he was.

The girl who had waked me was of a different class from the other two. Now that I could see her more plainly I saw that she had a likeable little face enough, but you couldn’t call her a beauty anyhow. Big eyes and short upper lip were her best features; her nose was a snub, and she was well freckled, and wore her hair in a club sort of short pigtail. Her dress was shabbier than the other woman’s, and I took her for a paid companion, or rather a poor relation, which would account for their tolerating her impudence. She was full of life, chattering nonsense the whole way across.

I’ve learnt since that that young woman’s manners do occasionally cause embarrassment in well-bred circles. Blood will out: her grandmother was a mill hand, and the grand-daughter’s thrown back to the original type. She’s told me since that ‘Guttersnipe’ was one of her school nicknames, and like most school names it’s deadly appropriate. She’s got the busy wits and the quick tongue of the gutter, combined with the haste in action and the discerning eye for essentials that lifted her forefathers out of it.

The Warren beach was steep, and when they got out of the boat they had to scramble up a high slope of sand. The girls reached the level beach at the top and were out of sight at once; the man lingered to pay me. He hadn’t anything less than a shilling, and I couldn’t change it.

‘Take the shilling and call it square,’ he said, blinking at me through his spectacles.

‘The fare’s twopence a head. I don’t take charity,’ I said rudely.

‘No need to be rude, my man,’ said he. ‘Either you can trust me or you can take the shilling and bring me the change later. Here’s my card. I’m staying at the Royal.’

‘I don’t know when I shall be ashore again,’ I told him. ‘When are you going back to Exmouth?’

‘In about an hour, I expect. The ladies are going to bathe.’

‘Then I’ll wait till you come back and put you across again,’ I said. ‘That’ll make up the shilling’s worth.’

He nodded and scrambled up the beach after his womenfolk. No sooner was he out of sight than the younger girl’s head appeared against the sky and came slipping and sliding down over the steep bank of sand again. When she reached me she was breathing fast as though with running.

‘How old are you?’ she jerked out.

‘Twenty-eight.’

‘You were drunk last night, weren’t you?’

‘I was.’

‘You fool!’ she said.

Words can’t tell the scorn in her voice. It brought me up all standing, as though she’d slapped me in the face. Literally I couldn’t answer her; before I’d thought of a word she’d scrambled up over the slope again and was gone, leaving me staring after her like a baby.

When I got my wits about me I don’t know when I was in such a rage. The cheek of the little slut!

One thing I would do. I’d show her I was independent, at all events. Somebody else could row them back and spend my sixpence. I got into the boat again and pushed off to where the Luck and Charity lay at anchor.

It’s queer the way one’s resolutions change with one’s moods. ’Kiah was getting breakfast, but I kept mine waiting whilst I had a shave with his awful razor. After a wash I felt better and got overside and had a swim. Scrambling aboard the small boat her looks disgusted me, and I tidied her up as best I could, next thing, and put a couple of cushions from the cabin into her.

Doing this I heard a clock at Exmouth strike nine, and remembered it was eight o’clock when I had left Exmouth beach. I don’t pretend to explain it, but almost before I knew where I was I was rowing back to the Warren beach to await my fares.

I’d been thinking hard about the ckeeky girl, you may be sure, and a good breakfast and a wash had revived my self-conceit. Her slanging indicated that she took some interest in me, I thought, and I made up my mind I’d rout out my last decent suit of clothes and go ashore in the evening and try and pick her up on the promenade. Her behaviour had confirmed me in my notion that she was some sort of dependent, and I thought I could furbish up sufficient togs to impress her with the fact that I was a yacht owner. I’d take the starch out of her, I reckoned. No denying she’d waked me to an interest in her.

They kept me waiting half-an-hour longer. Whilst I was waiting I remembered the card the man had given me and searched my pockets till I found it. ‘Mr Leonard Ward’ was the name, and the address ‘Mason College, Birmingham.’

When they came down the beach the little girl gave me one look up and down, and then sat in the boat with her back to me all the way across, ignoring my existence. The man Ward gave me my shilling and offered to pay me for waiting, which I declined, and the three of them were strolling up the beach together when I was seized with a diabolical impulse.

‘Here,’ I called after them; and as they turned round, ‘You—the little girl. Miss—Pamily, is it? I want you.’

Her face went crimson, but she walked back to me.

‘My name is Brand,’ she said, very stately.

‘Pamela Brand?’ I asked.

‘Pamela Emily Brand. And what do you want of me, pray?’

‘I want to ask you something—two things. Why did you go for me just now like you did?’

‘Because I hate waste,’ she said. ‘What’s the other thing?’

‘Will you meet me this evening?’

It was her turn to be struck speechless now; she couldn’t get any redder than she was already. She looked over her shoulder to see if the man Ward was within call, and then, her face quick and alive with resentment, leaned over and with her open hand fetched my face a smack you could hear fifty yards down the beach. She’s a lady, I tell you! And before I’d recovered, she was marching off with her nose in the air—just boiling with rage, I knew; and I laughed aloud, for all my stinging cheek. I’d drawn her. I’d teach her manners—the gutter-bred little prig.

Rowing back to the Luck and Charity I resolved more than ever to go ashore and seek her out that very evening. Now that she was piqued, I knew she would welcome any advance on my part as giving her an opportunity for revenge. So the first thing I did after scrambling aboard was to look out my best suit of clothes and give them a brush up. Then I turned in to get an hour or two of decent sleep.

Judging from the way the ship’s head was laying, and from the sunlight streaming through the doorway on to the floor, I guessed it must be about half-past two, and three-quarters flood, when I was waked by a boat bumping alongside and by someone climbing on our deck. ’Kiah was about, I knew, and reckoning he could attend to any visitor, I turned over and was trying to doze off again when he swung himself down the companion stair, barefoot.

‘Gen’leman to see you, sir,’ he said.

‘What name?’ I called after him.

A mumbled inquiry, and the voice of my morning customer in answer.

‘Tell him Mr Ward wants to see him. He had my card this morning.’

So Miss Brand had called in male assistance. Somehow I hadn’t thought that of her; but I hadn’t any particular objection to a row, so pulled my boots on and went on deck, stretching myself. He was sitting on the bulwarks, looking aloft, a hired boat and man hitched alongside.

‘Good afternoon,’ he said civilly.

‘Afternoon,’ I answered. ‘Want me?’

‘Yes. I—I—want—’ He hesitated. ‘I understand you want to hire this boat on a charter?’

‘I wanted to sell her and clear out to sea,’ I told him. ‘Failing that I wouldn’t mind a charter, certainly. But she’s not fit for a yacht. Her cabin fittings are stripped, and there’s nothing under this hatch roof but smashed bulkheads and driftwood.’

‘I don’t want a yacht. It’s for the coasting trade. How many tons could you get into her, and what water would she draw, loaded?’

‘Not more than about sixty tons, I should think. And I don’t know about draught. Something under nine feet, for certain. She’d never pay. You’d want three men, and how’s the freight on sixty tons to pay their wages?’

‘The draught is the point,’ he said. ‘They’re shallow waters I want her for. We can’t use a bigger boat very well. In fact, it’s just this small class of vessel I’m down here to look out for. She’s staunch, isn’t she?’

‘Sound as a bell,’ I assured him. ‘Come below and have a look at her, and then you can tell me just what you do want.’

We went all over her, and he seemed an intelligent man, from his comments. Being evidently shore-bred. he couldn’t see how badly she’d been stripped, of course, but the few questions and remarks he did make were all to the point. After going through the hold and forepeak we went aft into my cabin and sat down.

‘She’ll suit my purpose,’ he said, and looked across the table at me inquiringly.

‘Where do you want her to go to?’ I asked.

‘To and from the Scheldt,’ he said. ‘I am a director of a small company trading at Terneuzen, in the Isle of Axel. We have a couple of boats on charter now, but we’re busy and can do with another, for a year at least. You would take our goods from English ports here on the south coast, returning in ballast. What ballast did you say this boat wanted?’

‘Summer, fifteen tons or so; winter, twenty-five, I daresay.’

‘You can allow for more than that,’ he said. ‘We’re excavating beside our wharf there and are glad to get the mud taken away. So you needn’t blow over for want of ballast. And now as to terms.’

We discussed terms easily enough. Thinking such a small company as he described would be sure to haggle. I asked twice what I was prepared to take, and he accepted on the nail. After that, I was almost ashamed to point out that I should have to ask for an advance.

‘The boat isn’t fit for sea as she is,’ I explained. ‘I’ve sold all my spare stores, and shall have to pay for labour as well as fit her out. If you’re in a hurry, that is. I daresay my man and myself could get her rigged in a month or five weeks.’

‘That won’t do,’ he said. ‘I want you to get under way just as soon as you can. We’ll advance you fifty pounds. Will that be enough?’

I nodded. ‘That’ll be ample. As to security? I’ll give you a mortgage on the boat herself.’

He seemed to approve of the suggestion. ‘That’s business,’ he said. ‘I’ll get the mortgage prepared at once, and you can have the cheque when you please. You’ll want to take on another man or two, won’t you?’ He got up and went on deck, me feeling almost dazed with my good luck.

He shook hands as he was going over the side. ‘By the way, I shall want your name and address.’

‘My name’s West—James West.’ It didn’t seem quite the occasion to drag in the Carthew hyphen part of the business. ‘As to address, I haven’t one ashore. You’d better describe me as master and owner of the ketch Luck and Charity, registered at Plymouth.’

‘That’ll be good enough,’ said he, and went down into his boat and was rowed away, leaving me fit to jump with delight.

‘What du he want?’ ’Kiah asked.

‘Sir,’ I shouted at him. ‘Say “sir,” you uncivil Topsham dab.’

‘Yu ’eaved flukes at me for callin’ ’ee “sir” yes’day,’ he protested.

‘That was because you were my partner then. Now you’re my crew, my first orficer, my navigating loo-tenant, my paid wage-slave. We’ve got a job, ’Kiah. Your wages are doubled as from last October. You’ll have a lump of arrears to draw tomorrow. Go and wash your face, and then go ashore and spend the money I got for the dinghy last night. In meat, d’ye hear? A duck, and green peas, and a cold apple tart at Crump’s, and cream to eat with it. Us’ll feed like Topsham men when the salmon comes up river, ’Kiah. Us have got a job, ’Kiah—a twelvemonth charter-party at good money—and us draws fifty quid tomorrow. D’ye understand, you plantigrade?’

‘Caw!’ said ’Kiah cheerfully, and went forward to wash himself before going ashore.

When I woke mext morning it struck me I’d been in rather a hurry to take the man Ward at his word; but the confidence wasn’t misplaced, for he came aboard at eleven with the cheque in his pocket and the mortgage deed ready for signing. That was soon done, and he handed me the money and my first instructions. I was to get the topmast up; replace the missing stores and victual the boat; hire an extra hand and proceed to Teignmouth, there to load clay for Terneuzen. My consignee was a Mr Willis Cheyne, the company’s representative on the spot, and I must look to him for further instructions.

The rigging once started we worked double tides. I took on two men instead of one, and drove them for all I was worth, intending to take whichever proved the better of them to sea with me. They turned out to be a pair of crawling slugs, and I sacked them the third day and looked for another couple to take their place. But the tourist season was beginning, all the best men on the beach were busy, and the report spread by my two failures discouraged the others. In the end ’Kiah went to Topsham one evening and returned with a cousin of his, a Luxon—everybody in Topsham is called either Pym or Luxon—and we three finished the job in a week from the day the other two were sacked. Ward was aboard nearly every day, and once he brought his womenfolk with him. I was aloft, too busy to do the polite, so I shouted to him to make use of the cabin and went on reeving the peak halliards. The Pamily girl scowled up at me till she must have nearly got a crick in her neck, but I gave her a friendly wave of the hand and after that saw no more of her than the top of her big straw hat. Foreshortened, she looked like a mushroom wandering about the deck.

Luxon was just such a silent shockhead as ’Kiah himself. I never learnt his other name; ’Kiah always called him ‘Banny,’ which was obviously impossible. The job done, he drew his money arid went ashore without a word to me of his future intentions, but ’Kiah explained he wouldn’t come to sea with us. ‘’E reckons ’e’d ruther stay ’ome,’ was all I could get out of, him.

The evening before we left Exmouth I was in the dock entrance, filling our water-breakers from the hose where the ferry steamers water, when a voice hailed me from the top of the steps and asked if I was the ferry.

‘What ferry?’ I asked, without looking up.

‘Across the river. To—Dawlish, is it? I want to keep along the coast road.’

‘You’ll find the Warren ferryboat on the outer beach. There’s a steam ferry leaves here for Starcross in half-an-hour or thereabouts.’

‘What good’s a sixpenny steam ferry to me? I’m on the road;’ and the owner of the voice came down and sat upon the steps just above me.

He was on the road and no mistake about it. I never saw such a long, lean, broken-down tramp in my life. His coat and shirt were worn through at the elbows, showing his thin, bare arms. The holes in his ragged tweed trousers showed he had on another pair of blue serge underneath, both pairs frayed to fringes at the heels. He wore no hat, and his boots were past even a tramp’s repairing. As he sat, he took one off, looked at it whimsically with his head on one side, and threw it into the dock, and then served the other in the same way.

‘It’s a pity to separate ’em,’ he said cheerfully. ‘True, they never were a pair, but they’ve done a good few miles in my company.’

‘You’re a chirpy bird,’ I said.

‘Of course I am,’ said he. ‘Why not? Six months ago I wasn’t given as many weeks to live, and yet here I am, fit and well, thanks to God’s fresh air and a sane life. I’ve neither house nor farm nor fine raiment to bother me, nor woman, child nor slave dependent on me. I’ve even half-a-lung less to carry than you have, by the healthy look of you. My hat once on, my house is roofed.’ He put his hand to his head. ‘I forgot. It blew over the cliff a few miles back. All’s for the best in this best of worlds. That’s another worry the less.’

‘You’ve got two pairs of trousers,’ I suggested.

‘True, O seer. A concession to public tastes. They are selected so that the holes in the inner pair do not correspond with those in the outer, and thus decency is observed. And now what about this ferrying business?’

I had got my water-breakers aboard the boat and was stowing them between the thwarts. ‘Jump in,’ I said. ‘I’ll put you across.’

‘I may as well warn you that I haven’t a sou to my name,’ he said. ‘You’ll have to work for love. I’ll take an oar and work my passage, if you like.’

It wasn’t the first time he’d been in a boat, evidently, for he came aboard neatly, without stumbling or awkwardness, took the oar I proffered him, and handled it very fairly.

Half-way across I asked him what he was doing at Dawlish.

‘Nothing, I expect. I’ve given up asking for jobs. It’s much easier to ask for grub. Almost anybody’ll give you that in this dear land of mine—poor folk especially—but work isn’t so easy to get. Besides, I’m an unhandy fool at the best. I never learnt any trade worth knowing.’

‘Have you a trade?’

‘Bless you, yes. I’m a pressman—or was, before my lungs began to go. The doctors ordered me fresh air and exercise in a mild climate and I’m getting them tramping the South of England. Then I was fat and flabby and unhealthy and morose; now I’m the lightest-hearted wastrel on earth, and I’ve stopped spitting blood these last two months.’

‘What are you going to do when the winter comes?’

‘Don’t know. Same thing as before, I suppose, unless I can ship south in some packet or other.’

I pricked up my ears. ‘Ship south, eh? Are you a sailor man?’

‘I used to report the big regattas for The Yachting Gazette,’ he said. ‘I had to know one end of the boat from the other to do that.’

‘Feel like supper aboard my boat?’ I pointed to where lay the Luck and Charity, just visible in the gathering dusk.

‘Nothing I should like better,’ he said airily, so we went aboard and I set before him cold fried sausages and baked mackerel.

The man was ravenous—almost starving—and he ate like a shark, I watching him across the table. In the lamplight one could see him better, and upon examination he wasn’t such a bad looking tramp. He had a short black beard and moustache, his hair was close-clipped, and, for a wonder, he was clean, save for the dust of the roads upon his tattered clothing. Lean as a lath, his cheekbones stuck out and his eyes were sunk in their sockets, yet he looked like what he had claimed to be, fit and well and sunburnt to a healthy brown.

After he wiped the dishes dean he got up.

‘Shall I wash up after myself?’ he asked.

‘No hurry. Sit down and chat. D’you smoke?’

‘When I get the chance. Thanks.’ He produced cigarette papers from some corner of his rags and rolled and lit a cigarette of my tobacco. Inhaling a few breaths luxuriously, he began to look about him. ‘Books—books,’ said he, and got up again to run his nose along my little shelf. ‘Practice of Navigation, Ainsley’s Nautical Almanac, South of England Cruises. Hullo! Pecheur d’Islande. D’you read Loti?’

‘With a dictionary handy.’

‘Good man. Pecheur d’Islande takes a bit of beating, don’t it? Henry James’s American, too.’

‘I’m trying to break myself in to him. The American’s readable.’

‘Readable! You savage. Half-a-mo’, though. Balzac. Marcus Aurelius. What sort of ship d’you call this?’

‘The Luck and Charity, coasting ketch.’

‘The Luck’s mine, the Charity yours. Extend it to a night’s shakedown, will you? A heap of old sails in any lee corner’ll do me well. I’m dog tired—and I give you my word I’m not verminous.’

‘You’re welcome,’ I told him. ‘Turn in when you like. I’ve got to be about early tomorrow morning—we’re going round to Teignmouth to load.’

As luck would have it, the Teignmouth tug brought up a vessel next morning, and as she was going back alone I bargained for a cheap tow round. In the hurry I forgot my guest, and when he came on deck we were passing the harbour mouth.

‘Shanghai’d me, have you?’ he said.

‘I forgot you. We’re only going as far as Teignmouth this trip. That won’t take you off your road, will it?’

‘Any road’s my road,’ he said philosophically. ‘Can I be of any use?’

‘Can you cook?’

‘Near enough, I expect,’ said he, and set ’Kiah free by frying the breakfast, which he did very well.

I was messing about the deck afterwards, tidying up a little, and took a pull on the topsail halliards, which were new stuff and were loosening in the sun. The other end of the rope was insecurely hitched, and my down haul pulled it off the pin and just out of reach. It began slowly to slide aloft over the sheave and was quickening pace when the tramp went up the shrouds like a lamplighter and caught it at the crosstrees.

‘You’ve done some sailoring,’ I said, when he came down, the free end in his teeth.

‘Yachting,’ he said shortly. ‘Just enough to know my own uselessness.’

‘Good talk,’ I said. ‘Care to ship with me aboard this packet. We want a man.’

‘What’s the trade?’

‘South Coast to the Scheldt, I understand.’

‘Sounds good enough,’ he said. ‘But I’m supposed to be an invalid of sorts. I may not be up to the mark, but I’ll try it for a bit, if you’ll have me, on one condition. I’m to chuck it any day I please without any nonsense about giving notice on either side.’

‘All right. We’ll see how it works. If you can’t stick it, you can’t; if you can you’ll be company for me. What’s your name, by the way?’

‘Voogdt.’

‘What a name! Dutch?’

‘My grandfather was. It’s a good enough name for me.’

‘No offence,’ said I, for he sounded testy. ‘Only we seem to have a rum collection of names here. Mine’s Carthew-West, the boat’s the Luck and Charity, the first mate is Hezekiah Pym, and now we’ve shipped a crew called Voogdt.’

‘Austin Voogdt, if you want the lot of it,’ he said, in perfect good temper once more. And so we came to Teignmouth with our full ship’s company.

CHAPTER III (#ulink_64058eea-2605-5f0a-a1ae-604bf1e5ce35)

CONCERNING A COMPANY OF MERCHANT ADVENTURERS (#ulink_64058eea-2605-5f0a-a1ae-604bf1e5ce35)

WE took forty tons of clay from Teignmouth, and with fair weather all the way up Channel reached Terneuzen on the fourth day. We made a lighthearted crew, all three: for me, I was to continue the cruising, that had amused me for the past two years, and be paid well for it, to boot; Voogdt, for all his baresark philosophy, was well enough pleased to have a roof over his head, warm clothing and regular meals; and as for ’Kiah, give him three meals a day and tell him what to do next, and he asked nothing more.

Voogdt got on wonderfully well with ’Kiah. A bundle of nerves, he used to almost dance with irritation at his deliberate speech and gait, slanging him in many-syllabled terms of abuse, which ’Kiah, strangely enough, seemed rather to enjoy.

‘Move. Get a move on you, you slab-sided megatherium,’ he would say; or, ‘Gangway! Make way for your betters, you hibernating troglodyte’; and ’Kiah would grin as he shambled about his work, peaceful and undisturbed. ‘’E’s a funny blook, id’n’ ’er?’ he said to me once, almost admiringly, as he was doing his trick at the wheel. ‘Uses longer words’n what yu du. French, I reckon.’ I fancy he thought Voogdt complimented him by assuming him proficient in that foreign tongue.

Personally, I got on very well with the man, too. He was mad, if ever a man was; but he was a gentleman and a good sort as well. His attitude towards life was recklessly joyous. ‘I lost half-a-lung in a month,’ he told me once. ‘Any shift of wind may finish me—a drop or rise of temperature in the wrong direction, or a degree more or less of humidity or dryness. Nobody really knows much about tubercle—how it may flourish or die in any given individual. I’m like a child wandering in a whirling engine-room in the dark. A false step or a lurch, and—whisk I I’m gone. What’s the use of taking care?’

He couldn’t do the heaviest work, but, apart from that, was as good as any other man—better than most, because he was willing. In fact, he steered better than ’Kiah, who, having held a tiller before he could read, steered rather by instinct than conscious effort. ’Kiah would lean over the wheel as though half asleep, swaying to the motion of the vessel, and although he steered as well as the average fisherman, carelessness born of familiarity often let him half-a-point or so off his true course. He steered as much by the feel of the sails as by compass, and so rarely needed to exert himself. Steering well enough for all practical purposes, he didn’t try to do better. Not so Voogdt. His eyes never left the bows except for an occasional quick glance at the card, and he put his uttermost muscle and will-power into his work. It exhausted him, of course. I’ve seen him mop the perspiration from his face when he was relieved; but he steered to a hair-breadth nicety all the time.

I was thankful to have found him, and when I found out what manner of man he was, I offered him the spare bunk in my cabin, thinking he would be more in place there than sharing the forecastle, good chap though ’Kiah was. Voogdt said as much at once.

‘’Kiah’s an awfully decent sort. Think it’d hurt his feelings if I shifted?’

‘Ask him,’ I suggested, and Voogdt did so. I fancy he told him my bookshelf was the principal attraction aft. ’Kiah displayed no wounded feelings whatever and Voogdt’s thought for him only rendered him the more welcome in my quarters; so it was a very merry and bright ship’s company that entered the Scheldt the fourth morning after leaving Devonshire.

The Deutsche-West-Inde boats used to call at Antwerp, so I’d been in and out of the river often enough before. Terneuzen lies on the south bank, at the entrance to the Ghent ship canal, about a couple of miles from the mouth of the river, and as tide was making we managed to get there without a pilot. It seemed to me a queer place for an English company to open shop, yet there were the sheds, plain enough to see with ‘Isle of Axel Trading Company’ painted upon them as large as life. They were built on the big embankment that keeps the tide off the fields, a good mile from the town and lock-gates, flat Dutch pastures and tillage all around them, and I never saw a place that looked less like business in all my life. Four small sheds of wood and corrugated iron sufficed for office and warehouses, and a chimney smoking behind the office hinted at some sort of dwelling under the same roof. The wharf was a mere skeleton of wooden piles sticking out into the water, with a six-foot planked way along the top leading to the sheds. According to the chart, the whole lot, houses and wharf, would be half-a-mile from the river at low water, and separated from the stream by dreary mud-flats. It was just high tide when we got there, and so were able to float alongside the wharf, a red-faced youngish man with short curly hair shouting directions from the shore. We rode so high that we could look over the embankment right down on the cows feeding in the green pastures behind it. The place was as peaceful as a dairy farm, no houses nearer than the town, and I wondered more than ever what trade any company could do in such a deserted spot. As soon as we were made fast the curly-haired man came aboard, very busy about nothing.

‘My name’s Cheyne. I’m the manager. Capt’n West? With clay from Teignmouth?’

‘Forty tons,’ I said.

‘Good. May as well get your hatch cover off, Capt’n. Then come ashore’n have a drink. We’ll get it out of her tomorrow, ’n then ballast you to rights, ’n off to sea again, eh? Too long in port’s bad f’r th’ morals, eh?’

‘Shouldn’t think there was much chance of going on the bend here,’ I said. ‘Unless you go bird-nesting or chasing cows.’

‘Y’ can go on the bend anywhere, cocky,’ he said, and hiccupped, and I noticed he’d managed it all right. ‘Terneuzen’s a hot little shop, lemme tell you. ’T least I’ve livened ’em up a bit. Sleepy hole it was before they had me t’ liven ’em up. We’ll go into town this evening an’ shake a leg, what?’

I took my papers to his office—the untidiest hole I was ever in—sat among the litter for half-an-hour, had a drink and a chat, and then went aboard again.

Voogdt was stowing the foresail when I got back and looked at me inquiringly.

‘That cove full?’ he asked.

‘Full as an egg. Useful sort of manager, eh?’

‘Useful sort of business generally, I should say,’ he replied. ‘What the dickens are they going to do with this clay here? Feed cows on it? Is your money all right, skipper?’

‘I haven’t earned my advance of fifty yet. When I have, I’ll ask for another.’

‘I should, if I were you,’ said he, and then the matter dropped.

However, there were more signs of activity next morning. We rigged a rubbish wheel at the gaff-end, and with the help of four hired Dutch labourers started to get the clay ashore. Even Cheyne put on an old suit of clothes and bore a hand, but I never saw such slack methods as his in my life. The man worked like a navvy, I grant, but I should have thought he’d have been better employed in tallying the tubs of clay. As it was, he’d pull and haul with the rest of us, very noisy and hearty, and I admit he hustled those slow-bellied Dutchmen better than I could, knowing the language as he did. Then, when we’d got out a half-dozen or dozen tubs, he’d pick up his tally-book again.

‘How many’s that?’ he’d cry.

‘I make it a hundred and twenty-three.’

‘Hundred and twenty-three goes,’ he’d say, and tick them off without checking my figures, and then back to the tackles he’d go again. I put him down as unmethodical but a man-driver; and the driving was wanted no denying that, for those four Dutchmen might have been picked for their stupidity. In fact, two of them were no better than sheer imbeciles.

When we came to the bottom of the forty tons Cheyne began to get fussy. He was as careful to have the last pound or two of clay out of her as he’d been careless about the two-hundredweight tubs. He even had the tubs and buckets scraped and the sides of the hold cleaned down as though he wanted to make up for his slackness in the tallying. It was high water again by the time we had done and he said we could knock off till half-ebb.

‘Your chaps had better turn in for a spell,’ he told me. ‘We work at low water after this. I’m going up town now to get some grub. Care to join me, Capt’n? Yes? Come along, then.’