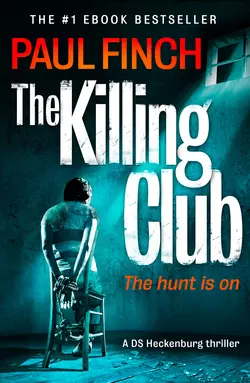

The Killing Club

Paul Finch

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 481.09 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Get hooked on Heck: the maverick detective who knows no boundaries. The perfect read for fans of Stuart Macbride and Luther.DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg is used to bloodbaths. But nothing can prepare him for this.Heck’s most dangerous case to date is open again. Two years ago, countless victims were found dead – massacred at the hands of Britain’s most terrifying gang.When brutal murders start happening across the country, it’s clear the gang is at work again. Their victims are killed in cold blood, in broad daylight, and by any means necessary. And Heck knows it won’t be long before they come for him.Brace yourself as you turn the pages of a living nightmare. Welcome to The Killing Club.