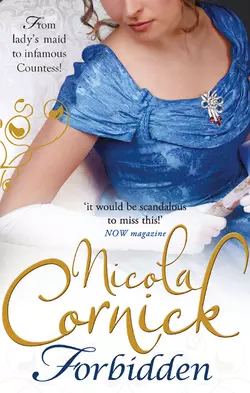

Forbidden

Nicola Cornick

Scandal isn't just for rogues, as the daring women in USA TODAY bestselling author Nicola Cornick's scintillating new series prove….As maid to some of the most wanton ladies of the ton, Margery Mallon lives within the boundaries of any sensible servant. Entanglements with gentlemen are taboo. Wild adventures are for the Gothic novels she secretly reads. Then an intriguing stranger named Mr. Ward offers her a taste of passion, and suddenly the wicked possibilities are too tempting to resist….Henry Atticus Richard Ward is no ordinary gentleman. He’s Lord Wardeaux and he is determined to unite Margery with her newfound inheritance by any means—including seduction and deception. But when the ton condemns the scandalous servant-turned-countess and an unknown danger prepares to strike, will Margery accept Henry's protection in exchange for her trust?

Nicola Cornick’s novels have received acclaim the world over

‘Cornick is first-class, Queen of her game.’

—Romance Junkies

‘A rising star of the Regency arena’

—Publishers Weekly

Praise for the SCANDALOUS WOMEN OF THE TON series

‘A riveting read’

—New York Times bestselling author Mary Jo Putney on Whisper of Scandal

‘One of the finest voices in historical romance’

—SingleTitles.com

‘Ethan Ryder (is) a bad boy to die for! A memorable story of intense emotions, scandals, trust, betrayal and all-encompassing love. A fresh and engrossing tale.’

—Romantic Times on One Wicked Sin

‘Historical romance at its very best is written by Nicola Cornick.’

—Mary Gramlich, The Reading Reviewer

Acclaim for Nicola’s previous books

‘Witty banter, lively action and sizzling passion’

—Library Journal on Undoing of a Lady

‘RITA

Award-nominated Cornick deftly steeps her latest intriguingly complex Regency historical in a beguiling blend of danger and desire.’ —Booklist on Unmasked

Dear Reader,

Welcome to Forbidden, the sixth and final book in the Scandalous Women of the Ton series! Forbidden is a rags-to-riches story featuring Margery Mallon, maidservant to so many of the previous scandalous women.

When Margery discovers that she is heiress to the richest earldom in England, she is swept from her drab existence into a world of unimaginable luxury, with beautiful clothes, glittering jewels and the most handsome men in the country begging to marry her. But the one man she wants is Henry, Lord Wardeaux, the man whose inheritance she has stolen and whom she can never trust. Margery and Henry’s passionate love story unfurls against a backdrop of elegant country houses and fashionable Ton balls, but can the Cinderella from the back streets of London ever find true happiness? Featuring all the previous characters from the Scandalous Women series, Forbidden is a fairy tale I had such great pleasure in writing and I hope you enjoy it too!

Best wishes,

Nicola Cornick

Author’s Note

In the Peerage of Great Britain, there are a dozen titles that can be inherited in the female as well as the male line. The earldom that Margery will inherit is one of these.

Tarot cards are used to foretell the future and the fortunes of the characters in Forbidden. The Tarot has been used for hundreds of years to predict the future.

Forbidden

Nicola Cornick

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Don’t miss the rest of theScandalous Women of the Tonseries, available now!

WHISPER OF SCANDAL

ONE WICKED SIN

MISTRESS BY MIDNIGHT

NOTORIOUS

DESIRED

Also available fromNicola Cornick

DECEIVED

LORD OF SCANDAL

UNMASKED

THE CONFESSIONS OF A DUCHESS

THE SCANDALS OF AN INNOCENT

THE UNDOING OF A LADY

DAUNTSEY PARK: THE LAST RAKE IN LONDON

Browse www.mirabooks.co.uk or www.nicolacornick.co.uk forNicola’s full backlist

To Bellbridge Montagu, Monty, the most loyal animal companion and best friend a writer could have, with love and happy memories

PROLOGUE

The Wheel of Fortune: Fate turns its wheel London, April 1817

THE MAN SITTING BEFORE HIM had a certain reputation.

Ruthless. Intelligent. Controlled. Dangerous.

Mr. Churchward knew a little of his history. Baron Henry Wardeaux had been a soldier. The way he spoke still bore the trace of command, clipped and direct. He had fought with Wellesley in the Peninsular War where he had been known as The Engineer for his skill in military fortifications. He had done other work, too, spoken of in whispers, secret work behind enemy lines. Mr. Churchward was a lawyer, a man given to dealing in facts and figures, but he believed the stories told of Henry Wardeaux.

“So, Mr. Churchward,” Wardeaux said, sitting back in the high-backed armchair and crossing one elegantly booted leg over the other. “Have you discovered proof that Miss Mallon is Lord Templemore’s granddaughter?”

No pleasantries about the weather, which had been mild and wet of late. No enquiries into Mr. Churchward’s health, which was good but for a few twinges of gout. Lord Wardeaux never wasted words.

Mr. Churchward shuffled his papers a little nervously. He cleared his throat. “We have found no definite proof, as yet, my lord,” he admitted. “It has only been two days,” he said, trying not to sound defensive.

Two days since a man had come to Mr. Churchward with information that the Earl of Templemore’s granddaughter, who had been missing for twenty years, was alive and well, and working as a lady’s maid in London. Two days of frantic activity to try to discover if the information could possibly be correct.

It had been astonishing news, news that had revived the health and hopes of the old earl. He had sent his godson and heir, Henry Wardeaux, to London immediately. If the report was true, Henry Wardeaux would no longer be the heir. Templemore was one of only a handful of titles in the country that could descend through the female line.

Churchward wondered how Lord Wardeaux would feel about losing the huge Templemore inheritance. He would never know. Henry Wardeaux would never reveal his emotions on that or any other subject.

“If you have not yet found proof, what have you found?” Wardeaux asked.

Mr. Churchward gave a sharp sigh. “We have discovered a great deal about Miss Mallon’s adoptive family, my lord. None of it is good.”

Wardeaux’s firm lips almost twitched into a smile. “Indeed?”

“Her elder brother owns a business buying and selling secondhand items. It is a cover for the sale of stolen goods,” Churchward said. “Her middle brother works in a tavern and her youngest brother…” The lawyer shook his head sadly. “There is no criminal activity he has not dabbled in. Highway robbery, fraud, larceny…”

“Why is he not locked up?”

“Because he is good at getting away with it,” Mr. Churchward said.

This time, Henry Wardeaux did laugh. “And from this den of thieves comes Lord Templemore’s granddaughter and heiress,” he said.

“Perhaps,” Mr. Churchward admitted. The circumstantial evidence that Margery Mallon was really Lady Marguerite Saint-Pierre was very strong, but he disliked circumstantial evidence. It was irregular, lacking firm verification. He wanted facts, witnesses, written testimony, not the faded miniature portrait and the garnet brooch that his informant had provided.

He fidgeted with the quill pen that lay on his desk. Never, in his long and distinguished career serving the nobility, had he been involved in such a case as this. When the earl’s daughter had been murdered twenty years before and her four-year-old child stolen, no one had ever expected to see little Marguerite again. No one, neither Bow Street nor the private investigators the earl had hired, had been able to trace her. The earl had mourned for years.

Wardeaux shifted slightly in his chair. “If you cannot prove one way or the other whether Miss Mallon is Lord Templemore’s granddaughter, Mr. Churchward, I shall have to do so myself.”

“If you gave me more time, my lord—” Churchward began, but Wardeaux lifted one hand in so authoritative a gesture that he fell silent.

“We don’t have time,” Wardeaux said. There was an edge of steel beneath the quiet words. “The earl is anxious to be reunited with his granddaughter.”

Mr. Churchward understood the urgency. The earl was dying. Even so, he hesitated. He knew Margery Mallon, and in turning over the case to Henry Wardeaux he felt as though he was throwing her to the wolves.

“My lord…” he said.

Wardeaux waited. Churchward sensed his impatience. He was a hard man, a cold man whose life had driven all gentleness out of him.

“The girl has no notion of her parentage,” he warned. “According to my enquiries she is quite…” He groped to find the appropriate word. “Innocent.”

Wardeaux looked at him. Mr. Churchward found it disconcerting. The darkness in his eyes suggested he had long ago forgotten what true innocence was.

“I see,” Wardeaux said slowly. He stood up. “Where do I find her?”

CHAPTER ONE

The Moon: Take care, for all is not as it seems

THE CLOCK ON ST. PAUL’S CHURCH was chiming the hour of ten as Margery went down the servants’ steps into the basement of Mrs. Tong’s brothel. She had not intended to arrive so late. Normally, she called at the Temple of Venus during the day when there were no customers and the courtesans were resting in their rooms in anticipation of a busy night ahead. Mrs. Tong’s girls were generous, which was more than could be said for Mrs. Tong herself. They let Margery into their rooms and let her take away their discarded gowns, hats, gloves, anything they had finished with, in return for the fresh pastries and sweetmeats that Margery made herself.

Tonight Margery had brought candied pineapple and marzipan treats, sugar cakes and tiny Naples biscuits made of sponge and jam.

She made her way up the back stairs to the boudoir on the first floor. The room was a riot of color, silk cushions in purple and gold, red velvet curtains drawn against the night. The air was thick with chatter and the scent of perfume and candle wax. The girls were ready for their night’s work but they almost swooned with greed and delight when they saw Margery with her marketing basket. They ran to fetch scarves and gloves to trade for the cakes.

“Girls, girls!” Mrs. Tong bustled in with the air of a circus trainer rounding up her performing animals. “The gentlemen are arriving!” The madam clapped her hands sharply. “Miss Kitty, Lord Carver is asking for you. Miss Martha, try to charm Lord Wilton this time. Miss Harriet—” she permitted a small, chilly smile to touch her lips “—the Duke of Tyne is very pleased with you.”

Mrs. Tong tweaked a neckline lower here and a hemline upward there, then sent her girls down to the salon. They left in a chatter of conversation and a cloud of perfume, waving farewell to Margery, licking the sugar from their fingers. Margery watched them flutter down the main staircase like a flock of brightly colored birds of paradise. Accustomed to coming and going via the servants’ passage, she had only once glimpsed the brothel’s reception rooms; they had seemed lush and mysterious, a dangerous and different world, draped with bright silks and rich velvets, adorned with the prettiest and most skillful courtesans in London.

The room emptied, the chatter died away. Mrs. Tong’s dark, beady gaze passed over Margery dismissively, as if she was a trader who knew the price of everything and could see nothing worth her time. Margery knew what Mrs. Tong was thinking. She had seen that thought reflected in people’s eyes for years. She was small and plain, a mouse of a creature, all shades of brown. No one ever wasted a second look on her. She was used to it and she did not care. Good looks, Margery had often observed in her career in service, so often led to trouble.

“You’d best be on your way.” Mrs. Tong popped one of Margery’s marzipan treats into her mouth and blinked in ecstasy as the sugar melted on her tongue. “Make sure you take the back stairs,” she added, sharply. The sugar had not sweetened her mood. “I don’t want any of the customers thinking you work for me.” She caught the corner of a golden gown that was trailing from Margery’s basket. “Is that wasteful strumpet Kitty throwing this away? There’s plenty more wear in it.” She tugged and the gown fell to the floor in a waterfall of silk and lace. “Go on, be off with you. And leave those pineapple candies.”

“No gown, no pineapple,” Margery said firmly.

Mrs. Tong rolled her eyes. She bundled the gown up and threw it at Margery, who caught it neatly. Mrs. Tong pounced on the packet of candies.

“I’ll take the marzipan, as well,” she said, snatching it from the basket.

Margery’s last glimpse of Mrs. Tong, as she closed the door and slipped out onto the landing, was of the bawd slumped in a wing chair, wig askew, legs akimbo, stuffing sweetmeats into her painted face as though she were a starving woman.

The landing was quiet and shadowed. The girls were downstairs now, plying their customers with wine and flirtatious conversation. No doubt Mrs. Tong would be joining them as soon as she had recovered from her excesses. Margery could hear snatches of music and laughter from the open doors of the salon. She trod softly toward the servants’ stair, her steps muffled by the thick carpet. Even had she lost the golden gown through Mrs. Tong’s miserliness, she would still have had a good haul tonight. There were three pairs of gloves, two hats—one of which was squashed flat, rolled upon in an amorous encounter, perhaps—two more gowns, one ominously ripped, a beautiful silk scarf that was a little stained with wine, and an assortment of undergarments. These had surprised Margery; the girls had told her they wore none.

Billy would be pleased with her. There was a great deal of material that could be reused and clothing that could be resold. Margery’s brother and his wife ran a shop in Giltspur Street that traded in secondhand clothes and various other things. Margery never enquired too closely into the nature of Billy’s business interests—she suspected he was a fence for stolen goods—but he was fair to her and gave her a cut of the profits on the materials she brought in.

Tomorrow, on her day off, she would deliver the clothes and join Billy, Alison and their brood of infants for tea. Tonight, though, she had to get back to Bedford Square. Lady Grant was the kindest of employers but even she might be taken aback to learn that her lady’s maid visited the London brothels on a regular basis.

Margery was halfway along the landing when her foot caught in the Turkey carpet and she stumbled. The basket lurched from her hand. The golden gown, which she had quickly stuffed on top, unrolled like a balloon canopy, tumbled through the gaps in the wrought-iron banister and floated slowly and elegantly down to land in a heap on the marble floor of the hall below.

Margery stood transfixed. She did not want to lose the expensive silk gown, and she had traded three packets of sweetmeats for it.

On the other hand, she did not want to get caught venturing into those parts of the brothel that were forbidden to her. Mrs. Tong was quite capable of refusing her entry ever again if she broke the rules, and then a very lucrative source of income would be lost to her.

Very slowly, very carefully, Margery started to tiptoe down the broad main stair, all senses alert to discovery. She was halfway down the steps when there was a sound from above and she froze, pressing back into a shadowy alcove among erotic statues of naked frolicking nymphs and shepherds. Something long and hard prodded her in the ribs—a phallus belonging to a marble satyr with a particularly dreamy expression on his face. There was no wonder he looked so happy. Margery looked critically at his physique. She had no firsthand knowledge of such matters but common sense told her that it simply could not be life-size. Perhaps all Mrs. Tong’s statues were overendowed. Margery hoped they did not make the customers feel too inadequate.

Margery took another cautious step down, then another. Only three more to go and then she would be standing on the black-and-white-checkered floor of the brothel’s hall and the beautiful golden gown would be within her grasp. She would grab it, stuff it back in the basket and scoot through the green baize door that led to the servants’ quarters below stairs.

It was a simple plan and it almost worked.

She’d almost reached the entrance to the servants’ quarters when she saw that someone was blocking her way. It was not Mrs. Tong, full of righteous indignation, but a man, lounging in the shadows. He did not move. Nor did he speak.

The candlelight skipped across his face, emphasizing some features, concealing others. Margery could see that he had black hair but not the precise shade. It needed a cut. His face was thin and brown with high cheekbones that reminded her of the carved stone statues she had seen in churches. He had a groove down each cheek where he smiled and a groove in his chin, as well. An odd shiver rippled through her, for this was a man with a saint’s face but with sinner’s eyes, dark, wicked eyes, hiding secrets. His brows were strong and dark, too, and his mouth neither too thin nor too wide. When he smiled, Margery realized that she was staring at him, staring in fact at his mouth, which looked tantalizingly firm.

A bolt of heat streaked through her, fierce and unfamiliar, like the burn of spirits. It made her tingle and set her head spinning. She took a step back, trying to steady herself. It was very hot in the brothel. Perhaps that was why she felt so faint all of a sudden, or perhaps she was sickening for something, as her grandmother would have said.

Still the gentleman did not move. He looked at Margery. She looked back at him. He was a gentleman; there was no doubt about that. He was beautifully dressed, something Margery, with her eye for style and color, was quick to appreciate. His cravat was tied in a complicated arrangement she did not even recognize, and held by a diamond pin. A jacket of elegant proportions fit his shoulders without a wrinkle, in much the same way that his tight buckskins clung to his thighs. A dandy, Margery thought. She had a servant’s finely honed instinct for recognizing various qualities in men and women. This was a man of fashion, but she sensed that there was more to him than that, something dark, deep, dangerous perhaps, in a way she could not begin to understand. She shivered.

He was blocking her escape.

“May I help you, sir?” she asked, wanting to bite back the words as soon as they were spoken, for she realized that they were perhaps not the most felicitous choice in a brothel.

Something flared in his eyes like the shimmer of heat from the candles. He straightened and took a step closer to her. Margery involuntarily tightened her grip on the handle of her basket. The wooden struts creaked.

“I am sure that you can.” His voice was very mellow. He sounded amused. His mouth had curled into another slow smile. It crept into those dark eyes and lit them with warmth that made Margery’s face burn. The strange awareness drummed more persistently in her blood.

This is a rake. Take care….

“I don’t work here,” she said quickly.

He paused. His gaze slid over her in a slow, thorough appraisal. Oh, yes, this was a rake. He knew how to look at a woman. There was an expression in his eyes that Margery had seen before. She had seen it in the eyes of many men looking upon the beautiful scandalous ladies for whom she had worked. She had also seen it in the gaze of people looking at her homemade sweetmeats. It was a mixture of greed and speculation and desire.

No one had ever looked at her in that way. No one had looked at her as though they wanted to eat her up, sample her, taste her and savor that pleasure. Such an idea was absurd, impossible.

Except that it was not, for this man was looking at her with acute interest and—she gulped, her throat suddenly dry—definite desire.

There had to be some mistake. He was confusing her with someone else.

“You don’t work here,” he repeated softly. He took a step closer to her, put out a hand and touched her cheek lightly with the back of his fingers. He wore no gloves and his hand was warm. Margery’s skin felt even hotter now.

“I’m only visiting,” she said in a rush.

His eyes widened. That smile, like sunshine on water, deepened. “There’s nothing wrong in that,” he said.

“No! I mean—” Margery floundered. “I’m not here to—” She stopped, wondering how on earth to describe the many and varied sexual practices that Mrs. Tong’s customers indulged in and she did not.

“I’m a lady’s maid,” she blurted out.

“Of course, you wish to be incognito.” The stranger shrugged. “Don’t worry. Mrs. Tong caters to all tastes. Many ladies enjoy dressing up as maids. Marie Antoinette, for example.” He smiled. “The marketing basket is a nice touch.”

“I’m not dressing up,” Margery said. She whispered it because he was now so close that she seemed to have lost the power of speech. “I really am a lady’s maid.”

The stranger laughed. “Then it is enterprising of you to supplement your income like this.”

Oh, lord. Now he thought she worked part-time as a lightskirt. It was not unheard of. Margery knew plenty of maidservants who sold their favors. It was more lucrative than scrubbing floors. It was whispered about Town that Lord Osborne had once visited his favorite brothel only to be confronted with his housemaid, who was working as a courtesan on the side. Margery had never considered supplementing her income that way. When she had left Berkshire for London it had been with her grandmother’s warnings ringing in her ears.

“London is a cesspool of vice,” Granny Mallon had said. “You take my word for it—I’ve been there once. Keep yourself nice for your husband, my girl.”

Margery had not cared much about finding a husband but she did care about keeping herself nice. It was important to her.

Besides, no one had asked her to give up her virtue anyway. Lady Grant’s twin footmen were too pretty and too much in love with themselves to notice anyone else, and the rest of the male staff were too young, or too old or too unattractive. And they were her friends. Margery had not felt a single amorous flutter toward any of them.

She did have a servant follower, Humphrey, who was the second gardener at the house next door. He brought her flowers and moped about the kitchen inarticulately, staring at her and reddening if she spoke to him. Humphrey reminded Margery of a stray animal. She felt pity for him and a kind of impatient affection. He did not make her tremble, or cause her knees to weaken, as they were weakening now. He did not make the breath catch in her throat or her heart beat like a drum, as it was beating now.

But Margery had also been warned about handsome gentlemen, men who preyed on naive country girls. Granny Mallon had not been wrong. London was indeed a home to every vice beneath the sun, and Margery was fairly certain that this man was intimately acquainted with quite a number of them. There was something downright wicked about him.

“We are at cross-purposes,” she said. She had to force the words out and her voice sounded husky and high-pitched at the same time. “I am not a lightskirt, nor am I here to sample any of the pleasures of the brothel—”

“Are you sure?”

Had he heard the note of wistfulness in her voice? Margery gulped.

“Not even—” his mouth was dangerously close to hers “—one kiss?”

“I’m a virgin!” Margery squeaked.

She saw him smile. “It takes more than one kiss to change that, sweetheart.”

There was a long, long moment in which Margery could feel the warmth of his body and hear the thunder of her pulse in her ears. She did want to kiss him. Her stomach dropped with shock as she realized it. Fierce curiosity licked through her, laced with wickedness. She could barely believe how she was feeling. Things like this did not happen to her; she was far too sensible to want to kiss strange gentlemen in brothels. Or so she had thought. Yet something of the sumptuous, bawdy atmosphere seemed to have infected her like too much wine in the blood, and here she was with this man who was temptation personified….

His lips brushed hers, so light a touch she thought she had imagined it. He captured her gasp of shock in another kiss, hot and sweet, that took her completely by surprise. It was her first kiss. Occasionally, she had wondered what it might feel like and now, all of a sudden, she knew. It felt as though there were too many sensations for her to grasp. She was aware only of the strength of his arms about her and the touch of his mouth on hers. It was all sparks and flame, fiery desire and the ache of wanting. It was enough to set her trembling in a way she had never felt before.

His lips very gently nudged hers apart, his tongue touched hers and everything became dizzying and molten and shocking in a perfectly delicious way. Now she knew why people liked kissing so much. She never wanted to stop. Her body felt soft and yielding against the strength and hardness of his. The pit of her stomach felt hollow with a peculiar longing. She was lost in a dangerous new world and did not want to be found.

A door shut sharply, away to their right, and Margery jumped and awoke, stepping back out of the circle of his arms. The sweetness fled and she felt cold and shocked. She was no Cinderella. Nor was she the heroine of one of the Gothic romances she read in secret. She was a servant girl and he was a gentleman. She wondered what on earth she had been thinking. No, she knew what she had been thinking. She had been thinking that kissing was the most delightful occupation she had yet discovered. More accurately she had been thinking that kissing this particular man was the most delicious thing imaginable. But that did not make it the right thing to do.

“No.” She pressed her fingers to her lips in a brief, betraying gesture and saw his gaze follow the movement and his eyes darken.

“No,” she said again. “This is quite wrong.”

“You!” Mrs. Tong was swooping toward Margery like a vengeful harpy, scarves flying, bangles clashing. “I told you—” She broke off as the man moved protectively close to Margery’s side. A smile of ludicrous brightness transformed her sharp features. “I beg your pardon, sir,” she said. “I did not see you there. Was this girl importuning you? She does not work here.” Mrs. Tong shot Margery another vicious vengeful look. “My girls are a great deal more professional—”

“I don’t doubt it, ma’am.” The gentleman cut in, so smoothly it did not sound like an interruption. “But you have the matter quite mistaken. I was lost—” a hint of amusement in his tone “—and Miss Mallon was doing no more than giving me directions, for which I am most grateful.”

“Since she is in the wrong place herself,” Mrs. Tong said sharply, “it amazes me that she could direct anybody.” She softened her tone and placed a hand on the man’s arm. “If you would care to come with me, sir, I can help you with whatever you require. You.” She jerked her head at Margery. “Out.”

“Goodnight, ma’am.” Margery did not spare Mrs. Tong more than a brief nod of the head. She could feel the madam’s eyes boring into her. She knew that Mrs. Tong suspected her of trying to tout for business. This would be the last time she was permitted in the Temple of Venus.

“Sir…” She dropped the gentleman a curtsy. “I hope you find your way.”

That provocative smile lit his eyes again and made her shiver. “You sound like a Methodist preacher, Miss Mallon.”

Margery turned away. She did not want to see him accompany Mrs. Tong into the brothel’s salon to be pounced upon by all those twittering courtesans. The thought set up an odd sort of ache in her heart. It was foolish to care, when all he had done was flirt with her. He will have forgotten her in less than a day, or very likely in less than an hour. The door of the salon opened, and light and music spilled out across the tiled floor of the hall. The real business of the evening was about to start. Margery tucked the basket beneath her arm and hurried through the door to the servants’ quarters, past the kitchens where the steam was rising and the cooks were sweating to prepare delicacies for Mrs. Tong’s guests. No one looked at her as she passed. Once again she had become invisible.

Out in the street the evening was bright and starlit but Margery’s feet suddenly felt like lead. It was no more than tiredness, she told herself. It had nothing to do with the gentleman she had met in the brothel and the contrary disappointment she felt because the encounter was over. She was tired because she had risen early to launder Lady Grant’s silk underclothes, for they were of such exquisite quality that they could not be trusted to anyone else. She had worked a whole day and here she was working a long evening as well, and once she was back in Bedford Street she would need to stay up into the early hours to await Lady Grant’s return from the theater. Those people who thought that lady’s maids had an easy life had absolutely no notion.

“Moll!”

Margery jumped and spun around. Her brother Jem was the only one who called her Moll. She waited as his tall figure detached itself from the shadows of the street corner and strolled forward.

“Thought it was you,” he said, as he caught up with her. He grinned. “What the devil were you doing in a bawdy house, Moll?”

“Minding my own business,” Margery said sharply.

Jem lifted the cover on the basket and took out the last of the honey cakes. Margery slapped his hand but he ate them anyway.

“They’ll spoil if they don’t get eaten,” Jem said. “They taste good,” he added with his mouth full, scattering crumbs on the cobbles. “You should have been a cook rather than a maid.”

“I don’t want to be a cook,” Margery said. “I only want to make sweets and pastries.” Her ideal was to be a confectioner and sell her beautiful cakes and sweetmeats for a living, but to set up in a shop was too expensive, so in the meantime she earned use of the oven at Bedford Street by helping Lady Grant’s cook with the more complicated French desserts and pastries.

“When I make a fortune,” Jem said, wiping the back of his hand across his mouth, “I’ll set you up in your own shop. I promise.”

Margery laughed. “I’ll die waiting for that day,” she said without rancor. She knew Jem spent every penny of his rather dubious earnings on gambling, drinking and women.

Although she would never admit it, Jem was her favorite brother. He had always been there for her, even though he was ten years her senior. She knew she should not favor him over the others because Billy worked hard to support his wife and growing family, and Jed, back in Berkshire, was a pot man in a respectable hotel. Jem was a scamp who never seemed to do an honest day’s work. But Jem was merry where Billy was serious. There was something about him that made it impossible to be angry with him even when he was helping himself to the rest of her stock. It was charm, Margery thought, as she fastened the cloth down firmly over the remaining cakes. Jem could charm the birds from the trees.

“I’ll walk you back,” Jem said.

“You’ll get no more cakes for your trouble,” Margery warned him.

Jem laughed. “You’re a hard woman, Moll.”

“And if you weren’t my brother,” Margery said, “I wouldn’t give you the time of day.”

Covent Garden piazza was full of evening crowds. An elegant lady, passing on the arm of a very smug-looking elderly gentleman, turned her head to stare at them. Margery sighed. It was always the same; ladies seemed quite unable to resist Jem. His golden hair and blue eyes, his smile and air of raffish charm worked on them like magic. They shed their clothes, their inhibitions and their husbands to fill his bed.

Jem sketched the lady an exaggerated bow and grinned with unabashed arrogance.

“For pity’s sake,” Margery said, pulling on her brother’s arm to draw him away. “Why don’t you just charge by the hour?”

Jem laughed again. “Now there’s a thought.”

“I’m sure Mrs. Tong would give you a job,” Margery said. “She likes pretty boys.”

“She’s not the only one,” Jem said complacently. He patted her hand. “Come along then, Miss Mallon. You had better lend me some of your respectability.”

Margery stopped dead again on the pavement, causing another couple to cannon off them in a volley of exclamations and apologies.

“What the devil?” Jem enquired mildly.

Margery did not hear him. She was clutching the handle of the basket a little more tightly as a frisson of disquiet rippled through her. She was back again in the hallway of the brothel, feeling the stranger’s hands on her, tasting his kiss and hearing his voice, smooth, mellow, charming the bawd out of her anger.

Miss Mallon was doing no more than giving me directions….

For the first time, Margery realized that he had known her name.

CHAPTER TWO

The Magician Reversed: Trickery and deception

MARGERY WAS SITTING on the top step of the sweeping staircase in Lady Grant’s house in Bedford Street. Next to her sat Betty, the second housemaid. They were hidden by the curve of the stair and the soaring marble pillar at the top. None of the guests thronging the hall below could see them, but they had the most marvelous view. Tonight, Lord and Lady Grant were hosting a dinner and a ball—one of the first major events of the new London Season—and word was that the ton were begging, buying and bartering for tickets. Lady Grant’s events were always frightfully fashionable. To fail to secure an invitation was social death.

“Oh, Miss Mallon,” Betty said, her big brown eyes as huge as dinner plates as she stared down on the scene below. “Look at the clothes! Look at the jewels!” She dug Margery slyly in the ribs with her elbow. “Look at the gentlemen! They are so handsome!”

“I’m studying the gowns, Betty, not the gentlemen,” Margery reproved, “and so should you if you wish one day to be a lady’s maid.”

She made a quick pencil sketch of one of the gowns in her notebook. Lady Grant was modish to a fault, a leader of fashion, and as her personal maid it was Margery’s responsibility to keep her at the forefront of style. She watched the ladies as they strolled out of the dining room, making notes of the dresses and the jewels, the combination of colors, materials and styles. She could spot the work of individual modistes and guess to within a guinea or two the price of each gown. She was good at her job and on evenings like this, she enjoyed it.

Margery paused in her sketches, chewing the end of her pencil. Betty was correct. There were some very handsome men present tonight. She could hardly pretend otherwise. For a moment she saw another face, a man with a wicked smile and laughing dark eyes, and she remembered a kiss that was hot and tender and promised so much. She felt a tingling warmth sweep through her, as though her entire body was slowly catching alight.

Margery had thought about the gentleman from the brothel in the week since they had met, and it was starting to annoy her that she could not banish him from her mind. She had thought about his voice, smooth but with that note of command, she had remembered the tilt of his head, the light in his eyes, his smile. Oh, yes, she had remembered his smile. She had seen nothing else when she went about her work, whether she was dressing Lady Grant for a drive in the park, or re-dressing her for an evening at the theater or undressing her afterward. She had been so distracted that she had over-starched the lace, mended Lady Grant’s hem with a most uneven stitch and added the wrong color of feather to her French bonnet. She had mislaid Lady Grant’s jewel box and had folded her favorite pelisse away in the wrong clothes press.

Then there was the kiss. It had haunted her dreams as well as her waking moments. She had lain in her narrow bed under the eaves and dreamed of kissing him, and she had woken flushed and confused, her heart racing, her body quivering with a delicious foretaste of passion. She was not quite sure what it was she wanted, only that her body ached and trembled for him, and that the more she tried to ignore it the more those illicit, demanding sensations rose up in her to beg for fulfillment. She felt on edge and inflamed, angry with herself that she could not conquer it. She was not a girl normally given to fantasies and it was odd and disquieting to be dreaming of a man, especially one she had met only once.

“How red your face is, Miss Mallon.” Betty was looking at her curiously.

“It’s very hot in here,” Margery said. She pushed the memory of the kiss from her mind and concentrated sharply on the crowd of guests now thronging the hall. Lady Rothbury, Lady Grant’s sister, was looking particularly stunning in a gown of eau de nil that shimmered with gold thread. Her gaze moved on, over the welter of colors and styles, the flash of diamonds and the flutter of fans. The air was scented now with a mixture of hothouse flowers and perfume. The chatter of the guests rang in her ears. Margery craned forward for a closer look at a tall, thin woman in a striped gown that shrieked Parisian design. The movement caught the eye of the gentleman by her side. He looked up and their eyes met.

All the air left Margery’s body in a rush. The candles spun in the chandeliers like a wheel of light.

It was the gentleman from the brothel.

For one very long moment they stared at each other while the sound beat in Margery’s ears, and the light dazzled her eyes and she could neither move nor breathe. Then the gentleman inclined his head in the slightest of bows, and a mocking smile curled his mouth, and Margery knew he had recognized her. Movement returned to her body, and with it an intensification of the hot blush that spread through her so fast she felt as though she were burning up. The pencil slid from her fingers. The book tumbled off her lap as she jumped to her feet, smoothing her skirts with clumsy hands. She drew back behind the shelter of the pillar. Her heart was hammering underneath her bodice and her palms felt damp.

Who was he? What was he doing here? Would he give her away?

If he should mention to Lady Grant that one of her maids had been in Mrs. Tong’s brothel, that would be the end of her. She would be thrown out in the street without a reference and with no prospect of another respectable job. Her heated body turned cold. She would be forced to beg her brother Billy for work. She could not be a tavern wench or even a courtesan because she was not pretty enough, and anyway, that was no way to think….

“Miss Mallon!”

Margery’s frightened thoughts were scuttling around and it was a moment before she realized that she was being addressed. Mrs. Biddle, the housekeeper, was standing a foot away, glaring at them. Betty gave a little gasp and leapt up, pressing her hands to her reddening cheeks, horror in her eyes at being caught. Margery retrieved her pencil and notebook, trying to regain a little composure.

“Run along, Betty,” Mrs. Biddle said sharply. “You have work to do.”

Betty scrambled a curtsy and scurried away.

“I’m sorry,” Margery said. “It was my fault. Betty would like to be lady’s maid one day and I was teaching her a little about the job.”

“Lady Grant is asking for her silver gauze scarf,” Mrs. Biddle said, her tone softening. She was always respectful of Margery’s position as a senior servant. In other ways, she mothered her. “If you could take it down to the parlor, Miss Mallon, Mr. Soames will deliver it to the ballroom for her ladyship.”

“Of course, Mrs. Biddle,” Margery said. It would be unheard-of for her to take the scarf to Lady Grant herself. No one but the butler and the footmen could be seen at an evening function. The rest of the servants had to be invisible.

She hurried to Lady Grant’s bedchamber and found the silver gauze scarf that perfectly complemented Lady Grant’s evening gown. It was impossibly sheer and silky, embroidered with tiny silver stars and crescent moons. For a moment Margery raised it to her cheek, enjoying the soft caress of the material against her skin. She had never owned so luxurious an item in her entire life.

With an envious little sigh, she tucked the scarf under her arm and went out along the corridor and down the servants’ stair. She hesitated before pushing open the green baize door that separated the servants’ quarters from the hall. She was not quite sure why. Her mysterious gentlemen, whoever he was, would be in the ballroom by now with the skinny woman in the elegant gown. There was no chance of meeting him.

Sure enough the hall was empty. She felt a slight pang of regret.

Mr. Soames was waiting for her in the parlor. She handed over the shawl and he took it as reverently as though it were a holy relic. Margery tried not to laugh. Mr. Soames was always so serious about everything, but then a butler’s job was a serious business, the very pinnacle of a male servant’s ambition. He had told her that, if she was lucky and worked hard, she might reach the top of her profession, too, and become a housekeeper one day.

Mr. Soames went out carrying his precious burden, closing the door softly behind him. Margery waited for a moment in the warm, silent confines of the parlor.

Margery had a hundred and one tasks waiting for her. Lady Grant’s dressing room needed to be tidied. Her nightclothes needed to be laid out for the moment, several hours ahead, when she finally retired from the ball. In the meantime, there was a pile of mending to be done, invisible work that required Margery’s keen eyes and nimble fingers. Her head ached to think of peering over tiny stitches in the pale candlelight.

On impulse she released the catch on the parlor door instead and stepped out onto the terrace. The mending could wait for a few more minutes.

It was cool outside, so early in the year. The air was fresh, the sky blurred with mist and scented with the smoke of all London’s chimneys. Beneath that was the sweeter smell of flowers mingled with perfume and candle wax. Margery drew in a deep breath. She could hear the music from the ballroom. The orchestra was playing the opening bars of a country-dance. She could picture the scene, the candlelight, the jewels, the vivid rainbow colors of the gowns. It was a world so close and yet so far out of reach.

The music called to something long lost inside her. In her memory, she could hear an orchestra playing and see an enormous ballroom stretching as far as the eye could see. Light sparkled from huge mirrors. The swish of silken gowns was all around her.

Her feet started to move to the music. She had not danced in years. She usually sat out the servants’ balls that employers insisted on holding each Christmas. She had no desire for her feet to be crushed by a clumsy coachman who fancied himself a dancer.

She twirled along the terrace, feeling lighter than air. It was ridiculous; she smiled to herself as she imagined quite how ridiculous she must look. It was also the sort of thing she never did. She was too serious, too sensible, to indulge in such a frivolous activity as dancing alone on a misty moonlit terrace.

The music changed, slid into a waltz, and Margery spun up against a very hard, masculine chest. Arms closed about her, steadying her. Her palms flattened against the smooth material of a particularly expensive and well-made evening jacket. Her legs pressed against a pair of very hard, masculine thighs encased in particularly well-made and expensive trousers. Margery noticed these things and told herself it was because she was a lady’s maid and trained to assess fashion, male or female, at a glance and a touch.

“Dance with me,” her dark gentleman said. He was smiling at her in exactly the way he had smiled in the hall of the brothel before he kissed her, that wicked, provocative smile. “You were meant to dance with me.”

Margery faltered. He was holding her in the way a man held his partner in the waltz, but suddenly she wanted to twist out of his grip and run away. She felt breathless and trapped and excited all at once.

“I cannot waltz,” she protested. It was a modern dance, new and more than a little scandalous. At least, it was the way that he was holding her. She could feel the heat of his body and smell his lime cologne. It made her head spin, which was a curious sensation.

Once she had drunk too much ale at the fair. This was similar, but a great deal more pleasant and a great deal more stimulating. The brush of his thigh against hers made her skin tingle, even through the ugly black wool of her gown. Oddly, it also made her feel very aware of the latent power in him, a strength and masculinity kept banked down under absolute control.

“You waltz beautifully,” he said. They were already moving, catching the beat of the music. “Where did you learn to dance like this?” His breath feathered across Margery’s cheek, raising delicious shivers deep within her.

“I learned to dance as a child,” Margery said. She frowned, reaching for the memories. It seemed ridiculous to think that in the rough-and-tumble of the Mallon household she had learned something as refined as dancing. She could not place the memory precisely. Yet she knew it had happened. Dancing was instinctive to her.

“This is very improper,” she said uncertainly.

“And completely delightful,” he said.

“You should be in the ballroom.”

“I prefer to be here with you.”

It was, indeed, delightful. Margery was forced to agree. His body was pressed against hers at breast, hip and thigh. His hand rested low in the small of her back in a gesture that felt astonishingly intimate. Heat flared through her, the sort of heat one simply should not be feeling on a cool April evening.

“Good gracious,” she said involuntarily. “Is this not illegal in public?”

She saw amusement glint in his eyes. “On the contrary,” he said. “It is positively encouraged.”

He drew her closer. His cheek grazed hers. His scent filled her senses. The warmth of his hand seared her back through the woolen gown and the cotton chemise beneath. Another shiver chased over her skin at the thought of his hands on her. She felt feverish, aware of every little sensation that racked her body. She felt as voluptuous as the nudes she had seen in the paintings in great houses, languid and heavy with wanting, her body as open and ripe as a fruit begging to be plucked and devoured.

It was shocking, it was delicious and it was wanton. She was tumbling down a helter-skelter of forbidden pleasure.

“You make me want to be—” She just managed to stop herself before the scandalous words came tumbling out.

You make me want to be very, very wicked….

He laughed, as though he knew exactly what she had been going to say and exactly how wicked she wanted to be. His lips touched the hollow at the base of her throat and she felt her pulse jump. Then they dipped into the tender skin beneath her ear, and this time her entire body twitched and shivered. She could not prevent it. She was helpless beneath the sure touch of his lips and his hands.

His shoulder brushed a spray of cherry blossom and the petals fell, the scent enveloping them. Somewhere deep in the gardens a nightingale sang.

A stray beam of candlelight from the parlor fell across them and in its light Margery saw that he was studying her face intently, almost as though he was committing it to memory. She felt disturbed. The mood was broken. She slipped from his arms and felt cold and a little bereft to have lost his touch. The music continued but he stood still now, his face in shadow.

“I should go,” she said, but she did not move. Suddenly she was scared; she wanted to beg him not to tell Lady Grant what had happened at the brothel but she was too proud to beg for anything. She always had been. Her brothers often said that pride and stubbornness were her besetting sins.

“Wait,” he said. “I wanted to ask you—” He broke off. It was too late. Some of Lady Grant’s guests spilled out onto the terrace, chattering and laughing. Margery knew that in a moment they would see her; see her with a gentleman, a maidservant caught in a guilty tryst.

“I must go,” she whispered.

He caught her hand. His was warm. He pressed a kiss to her palm, a feather-light caress. It made her tremble. The light in his eyes made her stomach swoop down to her toes in a giddy glide.

“Thank you,” he said, “for the dance.”

She had been seen. She heard the voices and spun around, pulling her hand from his. Her fingers closed over her palm as though to trap the kiss and hold it there.

“Who is that?” A woman in a filmy flame-red gown was peering at Margery through the darkness. Margery shrank back into the shadows as a couple of ladies giggled and pointed.

“It’s no one. A maidservant.”

Someone tittered. “How encroaching of her to be out here spying on her betters in the ballroom!”

Margery’s cheeks burned. At least they had not seen her dancing. And the terrace was empty. Her mysterious gentleman had gone.

Something glittered at her feet. She bent to pick it up. It was a cravat pin, slender, with a diamond head and a couple of initials entwined around the gold stick. She turned it over between her fingers and watched the diamond catch the light.

For a moment temptation caught her in its spell. The pin was valuable. If she gave it to Jem, he would give her money for it with no questions asked. There had been times in the past when he had asked her if Lady Grant had any jewelry or clothing or other possessions that she might not miss. Margery had given him a fine telling off and he had not mentioned it again, but now, staring at the glittering diamond, she thought longingly of the money she could put toward a little confectionery shop.

She gave herself a shake. No and no and no. Thieves and criminals had surrounded her since childhood. Billy was bad enough, a chancer and a con man, and Jem was worse. There was something very dangerous about Jem. Growing up among thieves was no good reason to become one. She would hand over the cravat pin to Lady Grant and tell her that she had found it. She would imply that one of the guests had dropped it and she had come across it by chance. She slipped it into the pocket of her gown.

“You, there! The little maidservant.” One of the women on the terrace was calling to Margery. “Fetch me a glass of champagne.” Her voice was haughty. The light from the colored lanterns skipped over a gown of striped silk. Margery recognized the thin, disdainful woman she had seen in the hall.

“I’ll ask one of the footmen to serve you, ma’am,” she said politely.

“Fetch it yourself,” the woman said. “I don’t want to wait.”

Someone else laughed. They were all looking at Margery, sharp and predatory as the bullies she remembered from the streets of her childhood. Jem had fought those children for her. Now she was on her own.

“I’ll ask the footman, ma’am,” she repeated, and saw the woman’s eyes narrow with dislike.

“What a singularly unhelpful creature you are,” she said contemptuously. “I will be sure to mention your insolence to Lady Grant.”

“Ma’am.” Margery dropped the slightest curtsy, enough to fulfill convention, but so slight as to be almost an insult.

She walked slowly, head held high, to the terrace doors. Once inside the parlor she shut the doors against the laughter and chatter on the terrace, then locked them for good measure and drew the curtains closed. Her hands were trembling and she felt tears pricking her eyes. She knew that it was foolish. Spiteful comments from people like the lady on the terrace were common in a servant’s life. She tried to disregard them. Most of the time the aristocracy ignored those who waited on them. Margery was accustomed to being considered a part of the furniture but it did not make cruelty or rudeness any more tolerable.

She slid a hand into her pocket and felt the prick of the cravat pin against her fingers. Already the waltz on the terrace felt like a dream. She had stepped out of time, forgotten her place as lady’s maid, forgotten her black woolen gown and practical boots, and had stolen a moment of pleasure in the arms of the most handsome man at the ball.

She took the cravat pin from her pocket and ran her fingertips over the entwined initials, H and W. She wondered who he was.

She knew she would not see him again.

CHAPTER THREE

The Hanged Man: Reversal and sacrifice

“COME CLOSER, HENRY, so that I can see you.” The voice was dry as tinder but the tone was still commanding, bearing overtones of the man the Earl of Templemore had been before illness ravaged his body. He sat in a chair before the fire, a fire that roared despite the high sun of an April day. The bright morning light made the red-flocked wallpaper look faded and dull, and struck blindingly across the rococo mirrors, reflecting back endless images of the earl hunched in his chair, a blanket shrouding his knees.

Henry Wardeaux came forward and formally shook the old man’s hand, just as he had greeted him for the past twenty-nine years. They had never been on more intimate terms, even though the earl was also Henry’s godfather. Lord Templemore was not a man given to displays of affection.

“How are you, sir?” Henry asked. It was a courtesy question only. He knew that the earl was dying; the earl also knew that he was dying and never pretended otherwise.

A dry rattle of laughter was his reply.

“I survive.” One white-knuckled hand grasped an ivory-headed cane as the earl sat forward in his chair. “If you have good news for me I might yet feel quite well. Did you meet my granddaughter?”

For a man who showed little emotion there was a wealth of longing in his voice. Henry felt a simultaneous jolt of pity and exasperation, pity that the old man was so desperate to find his daughter’s lost child that he would grasp after every straw, and exasperation that this very desperation made a shrewd man weak.

Mr. Churchward was still working to establish whether Margery Mallon was definitely the earl’s grandchild. Churchward was not the sort of man who liked to make mistakes, particularly not over something as important as the lost heir to one of the most ancient and prestigious earldoms in the country. Lord Templemore, however, had been certain of it from the start because he had wanted it to be true.

Henry took the seat that the earl indicated. “I have met Miss Mallon twice in the past ten days,” he said, taking care not to commit himself over whether the girl was the earl’s granddaughter or not. “In point of fact, I first met her in a brothel.”

The earl’s gaze came up sharply. Gray eyes, so bright, so cool, a mirror image of Margery Mallon’s clear gray gaze, pinned Henry to the seat.

“Did you?” The earl said expressionlessly. “Mr. Churchward indicated that Miss Mallon was a lady’s maid, not a courtesan.”

Henry wondered if it would have made any difference to the earl if Margery Mallon had been the most notorious whore in all of London. He thought it would probably not. The earl had waited twenty years to find his heir and he was not going to be dissuaded from his quest now.

“That is correct, sir,” Henry said. A smile twitched his lips as he remembered the small, bustling but efficient figure that was Margery Mallon. There was a no-nonsense practicality about her that was strangely seductive. “Miss Mallon does indeed work as a lady’s maid for Lady Grant in Bedford Street,” he said. “But she also makes sweetmeats and sells them to the whores in the bawdy houses of Covent Garden.”

The earl’s brows shot up. “How enterprising,” he said. “I assume Mr. Churchward warned you not to disclose that piece of information to me?”

“He counseled against it, sir.” Henry’s smile grew. “He thought that the shock of learning that your granddaughter frequented such a place might kill you.”

“And you said?”

“That you had frequented many such places yourself in the past, sir,” Henry said politely, “and that you would consider it far preferable that your granddaughter sold sweetmeats to whores rather than selling herself.”

The earl gave a bark of laughter. “How well you know me, Henry.”

Henry inclined his head. “Sir.”

The earl glanced at the array of family portraits that marched across the drawing room walls. “Perhaps Miss Mallon is the first Templemore in two hundred years to possess some of the mercantile spirit of our Tudor forebears.”

Henry followed the earl’s gaze to the portrait of Sir Thomas Templemore, founder of the dynasty, pompous in cloth of gold, the chain of office around his neck commemorating the peak of his success as Lord Mayor of London. Sir Thomas had been a self-made man who had risen to enormous wealth and power in the cloth trade, and greater riches still lending money to the feckless courtiers of Queen Elizabeth I. He had been the first and last of the Templemores to demonstrate any business acumen.

Henry’s mouth turned down at the corners. More recent generations of the family had maintained their wealth through spectacularly rich marriages. Templemore was costly to run and each earl had possessed a range of expensive vices from gambling on fast horses to the keeping of fast women. The present earl’s late wife had been the daughter of a nabob and he had married her solely for her fortune.

“I am prepared for Miss Mallon to have had a… checkered past.” The earl’s words drew Henry’s attention back. His gaze was shrewd, searching Henry’s face. “In some ways it would be surprising if she had not, given her upbringing. You may tell me the truth, Henry. It will not kill me.”

Henry sat back. He examined the high polish on his boots. His mother, whom he suspected was currently standing with her ear pressed to the other side of the drawing room door, would be silently urging him to take this God-given opportunity. She would be willing him to blacken Margery Mallon’s name in the hope that the earl might forget these notions of reclaiming his granddaughter and return to the accepted order, the one in which Henry inherited everything, estate, title and fortune.

But there could be no going back. And Henry was, if nothing else, a gentleman, and he was not going to lie.

“As far as I could ascertain,” Henry said, “Miss Mallon is a woman of unimpeachable virtue.”

The earl raised a brow. He had read into Henry’s words everything that Henry had not said. “Did you test that virtue?” He was blunt.

“I tried.” Henry was equally blunt. “We were, after all, in a brothel.”

Seducing Margery Mallon had been very far from his original intention. His purpose was to get to know Margery a little and see if he could determine whether she was the earl’s heir or not. Yet, when he had come face-to-face with her in the hall at the Temple of Venus, he had been presented with an opportunity he could not resist.

Or, more truthfully, an opportunity he had not wanted to resist. There had been something about Margery’s combination of innocence and steely practicality that had intrigued him. He had wanted to kiss her in order to put that innocence to the test, because the cynic in him told him that such virtue could only be pretense. Surely no woman of her age and station in life could be as inexperienced as she had claimed to be.

He had wanted to kiss her from sheer self-indulgence, too. She had smelled of marzipan and sugar cakes, and he had wanted to find out if she tasted as sweet as honey. He had been fascinated by her pale, fine-boned delicacy, by the vulnerable line of her cheek and jaw. Her mouth in particular had transfixed him; it was full, willful and sensual, a complete contradiction to the neat respectability of her appearance and enough to make a man dream of kissing her until she begged for more. The fact that she seemed to have no idea of the effect she had on him had only sharpened his hunger for her.

He had kissed her and discovered that she did indeed taste of honey, so he had kissed her some more and been floored by the desire that had roared through him. It had prompted him to carry her into the nearest room and strip off her disfiguring servant’s clothes and make love to her. If Mrs. Tong had not come upon them he was not sure how far his wayward impulses would have led him.

It had been as bad—worse—when he had seen Margery at the ball. He had forgotten all the questions he had prepared to ask and had lost himself in the pleasure of holding her in his arms. There had been an element of need in his fierce attraction to her. She was all sweetness and innocence and she washed the world clean of the violence and darkness he had seen in it. He wanted that sweetness in his life. He wanted to lose himself in her.

Arousal stirred in him again. Henry dismissed it ruthlessly. It was no more than an aberration. It had to be. He had never been attracted to ingenues and even if he had been, he had no business finding Margery Mallon sensually appealing. If Churchward discovered that she was not the Earl of Templemore’s granddaughter, she would continue her life as a lady’s maid none the wiser. If she was the lost heiress, then she would one day become Countess of Templemore. Either way, she was utterly forbidden to him, and the only thing that surprised him was that he had considered seducing her at all.

He had a beautiful opera singer in keeping who was sophisticated and experienced and everything that Margery was not. He thought of Celia, silken, skillful, obliging, and felt nothing more than vague boredom. He was jaded. No matter. He had long-ago stopped expecting to feel otherwise. Besides, Celia would leave him now that he was no longer heir to Templemore and could not afford her. He thought about it and found he did not greatly care. Mistresses came and mistresses went.

“And after you tried to seduce Miss Mallon,” the earl said, recalling him abruptly to the room and the business in hand. “What happened then?”

“Miss Mallon refused me,” Henry said. “She has no time for rakes.”

The earl’s smile was bitter. “A pity her mama did not display the same good sense.” He shifted in his chair as though his bones hurt him. “I’d scarcely call you a rake, though, Henry. You have far too much self-control to indulge in any excess. You do not have the temperament for it, unlike your papa.”

Unlike you, Henry thought. He studied the earl’s face, the tightly drawn lines about his mouth and chin that indicated both pain and grief. Guilt and remorse were his godfather’s constant companions these days. The Earl of Templemore would never admit to anything as weak as regret and yet Henry knew he must feel it; regret for the quarrel that had driven his daughter from the house twenty years before and led to her murder and the disappearance of her child, regret for the years of unbridled dissolution when he had tried to drown his loss in worldly pleasures, regret even for the difficult relationship that he had endured with his godson because Henry was not the heir that the earl had wanted and he had never been able to forgive him that fact.

Enough. If the earl had regrets about the past, that was his concern. Henry had no intention of emulating him.

“I have been remiss.” The earl’s dry voice cut into his preoccupation. “Will you join me in a glass of port wine, Henry?”

Henry did not trouble to ring the bell. He was perfectly capable of pouring two glasses of port. Besides, he would have to become accustomed to managing without servants if Margery Mallon inherited the Templemore title. His own estate was poor; everything that was unentailed had been sold off to pay for his father’s profligacy. He had been building it back up for years but the estate was small and would never be wealthy.

He could deal with hardship and struggle. He had seen plenty of it, in the Peninsular Wars. His mother, on the other hand, was too sheltered a flower to relish so drastic a change in circumstances. She had been living on the expectation of his future for years and had been in an intolerably bad mood ever since she had heard the news of Margery Mallon’s existence.

“Thank you.” The earl took the glass from his hand and took an appreciative sip. The cellar at Templemore was as fine as the late-seventeenth-century house itself. The collection of wines alone was worth thousands of pounds. Henry wondered if Margery Mallon had the palate to appreciate it.

“I want you to bring her to me.” The earl placed his delicate crystal glass on the Pembroke table and sat forward again, urgency in every line of his body. “I want to meet her, Henry.”

Henry stifled another burst of impatience. “My lord,” he said. “It is too soon. There may be some mistake. Churchward has not yet finished his enquiries and I have not been able to prove Miss Mallon’s identity beyond doubt.”

The earl cut him short with an imperious wave. “There is no mistake,” he said fiercely. “I want to see my granddaughter.”

Henry bit back the response that sprang to his lips. The earl’s face was ashen, his hand shaking on the head of the cane. Henry felt his unspoken words: if we delay I may not live to see her….

“Take Churchward,” the earl said, his gaze pinning Henry with all the fierce power his body lacked. “Go directly to Bedford Street to acquaint Miss Mallon with the details of her parentage and her inheritance. Then bring her here to me.”

It was an order, a series of orders. The earl never asked, Henry thought wryly. He was steeped in autocracy. There could be no argument.

Henry thought about Margery Mallon’s brothers. Unlike Margery, who had promptly returned the diamond pin he had deliberately let fall on the terrace, the Mallon men were dishonest through and through. He and Churchward had been at great pains to protect the earl from their exploitation. For all his fierceness, Lord Templemore was a sick and vulnerable old man whose life had been devastated by tragedy once before. Henry would not permit Margery’s adoptive siblings to manipulate the situation to their advantage.

There was also the danger to Margery herself. Twenty years before, someone had killed the earl’s daughter. The only witness to that murder had been her four-year-old child. If the murderer or murderers were still alive, the news that the earl’s granddaughter had been found could put her in the gravest peril. Henry had to protect Margery from that danger.

Which was why he had to find out the truth about Margery’s identity as swiftly as possible.

Henry forced himself to relax. “Very well, my lord,” he said easily. “It will be as you wish.” He checked the gilt clock on the mantel. He could be back in London before nightfall if he rode hard.

He would seek out Margery Mallon, but not to bring her directly to Templemore. He would learn as much as he could about her in this one night and then he would decide if she was truly Lady Marguerite de Saint-Pierre, heiress to the Templemore title and a huge fortune. He felt a pang of guilt at his deception but quashed it as quickly as he had dismissed the flare of lust. He could not afford either emotion. The future of Templemore was too important.

The earl sat back against the embroidered cushions, closing his eyes, suddenly exhausted. His skin was stretched thin across his high cheekbones. He groped for the wine and drank a greedy mouthful, sitting back with a sigh.

Henry stood abruptly, leaving his glass of wine untouched.

“Excuse me, sir,” he said. “I will go and fulfill your commission at once.”

“You’re a good boy, Henry.” The earl had opened his eyes again. They were weary, shadowed by all the unhappiness he had experienced. “I will see that you do not lose out when my granddaughter inherits.”

Henry felt a violent wave of antipathy. “I want nothing from you, sir. I have my own estate and my engineering projects—”

The earl dismissed them with a lordly wave. “Such matters are not work for a gentleman.”

“They are work for a penniless gentleman,” Henry corrected.

The earl laughed, that dry rattle again. “Marry an heiress and all your difficulties will be solved. Lady Antonia Gristwood—”

“Will not wish to throw herself away on me, my lord,” Henry said matter-of-factly.

“Perhaps a cit’s daughter would not be so choosy. You still have the title.”

How flattering. But it did rather sum up Henry’s prospects now. “I’ve no desire to wed, sir,” Henry said. The heiresses would melt away swiftly enough when they heard of his reversal of fortune. In their own way they were as fickle as his mistress.

The earl seemed not to have heard. His chin had sunk to his chest and he looked as though he was lost in thought. Henry wondered whether his godfather was still lost in the past. The earl, Henry thought, had a remarkable talent for alienating members of his family: first his wife, whom he had married for her money and betrayed before the ink was dry on the marriage lines, then his daughter, then his godson. He hoped to high heaven that if Margery Mallon was indeed the earl’s granddaughter he would not devastate her life, as well.

He swallowed the bitter taste in his mouth, bowed stiffly to the earl and went out. The hall was empty although the air trembled and the door of the Red Saloon was still swinging closed, a sure sign that Lady Wardeaux had indeed been eavesdropping. Henry did not want to have to confront his mother and her ruined hopes yet again.

Nor did he wish to see Lord Templemore’s younger sister, Lady Emily, endlessly reading the tarot cards and reassuring him that his fortunes would turn again.

They would turn because Henry would make them turn.

He had grown up at Templemore. He had been told from childhood that he would inherit the title and land and that he had to learn to be a good master. He had done more than that. He had taken the estate to his heart and he loved every last brick and blade of grass there. It would hurt to give them up, but he had suffered reversals in his life before. He had overcome them all.

The tap of his boots echoed on the black marble floor of the hall. He paused by the door of the library to study the John Hoppner portrait of four-year-old Marguerite Catherine Rose Saint-Pierre, painted just before she had vanished from her grandfather’s life.

The window in the dome far above his head scattered light like jewels on the tiles of the floor and illuminated the painting with a soft glow. Marguerite had been a pretty child, small, delicate, with golden-brown hair. She gazed solemnly out at him from her gilt frame, watching him with Margery Mallon’s clear gray eyes.

The earl had summoned him with such haste that he had not had time to change out of his riding clothes. He strode out to the stable, calling for a fresh horse to take him back to London.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Knight of Swords: A tall dark-haired man with a great deal of charm and wit

IT WAS SEVEN O’CLOCK on a beautiful spring evening. Warmth still shimmered in the air, and the sky over London was turning a deep indigo-blue. The sun was dipping behind the elegant facades of the houses in Bedford Street and the shadows lengthened among the trees in the square.

It was Margery’s evening off. She came up the area steps, tying her bonnet beneath her chin as she walked. She stopped dead when she found the gentleman she had danced with at the ball the previous night loitering at the top. He gave every appearance of waiting for her.

“What are you doing here?” she asked, her tone deliberately sharp. She had come down to earth since her encounter with him and had been berating herself for being a silly little fool whose head was stuffed with romantic nonsense. She was a lady’s maid, not Cinderella.

Even so, her heart tripped a beat, because his smile—the wicked smile that curled his firm mouth and slipped into his dark eyes—was so much more potent in real life than it had been in her dreams and memories.

“Good evening to you, too,” he said. “Are you pleased to see me?”

“Of course not,” Margery said. She put as much disdain into her tone as she could muster, knowing even as she did so that she was betrayed by the shaking of her fingers on the ribbons of her bonnet and the hot color that burned in her cheeks.

Damnation. Surely she had learned enough over the years to know how to deal with a rake. She had acted as maid to any number of scandalous women who had perfected the art of flirtation. She should meet this insolent gentleman’s arrogance with a pert confidence of her own. Yet she could not. She was tongue-tied.

She started to walk. “Why would I be pleased to see you?” she asked over her shoulder. “I barely know you.”

“Henry Ward, at your service.” He sketched a bow. It had an edge of mockery. “Now you know me.”

“I know your name,” Margery corrected. “I have no ambition to learn more.”

He laughed. It was a laugh that said he knew she was lying. He was right, of course, though she was damned if she was going to admit it. She quickened her pace. He matched it with minimum effort.

“Wait,” he said. “I’d like to speak with you.” He hesitated. “Please.”

It was the please that stopped her. She was not accustomed to courtesy from the aristocracy but by the time she had realized her mistake she was standing still and he was holding her hand. She had no idea how either of these things had occurred, only that his charm was clearly very dangerous to her.

“Miss Mallon—”

Margery snatched her hand back. “That reminds me. When we met in the brothel you addressed me as Miss Mallon. How did you know my name?”

She saw a flash of expression in his eyes that she could not read. Then it was gone; he shrugged lightly.

“I forget,” he said. “Perhaps Mrs. Tong mentioned your name.”

Margery shook her head. She knew that was not true. “No,” she said, refusing to be deflected. “She did not.”

Henry looked at her. His gaze was clear and open, yet she sensed something hidden. Instinct warned her that there was something he was not telling her.

“Then I do not know,” he said. “Someone must have told me your name. The brothel servants, perhaps, or one of the girls…”

Margery turned a shoulder and started walking again. A sharp pain had lodged itself in her chest, like a combination of indigestion and disappointment. She did not want to think about Henry spending time with Mrs. Tong’s girls, taking his pleasure with them, lying with one of them or perhaps more than one.

The images jostled in her head, bright, vivid, intolerably lustful and licentious. Jealousy, sudden and vicious, scored her with deep claws. It disturbed her because she had no right to feel it. She did not want to feel it. She had no claim on him. She might as well be jealous of the horribly disdainful lady in the striped gown, the one who had been clinging to Henry’s arm at the ball.

She paused. Now she thought about it, she was jealous of the snobbish aristocrat in the striped gown.

“I didn’t stay at the brothel.” He put one hand on her sleeve. She stopped again. “There is no need to be jealous,” he said softly.

Margery shook him off. “Why would I be jealous?” She did not want him reading her mind. It was too disconcerting.

“You are jealous because you like me.” He smiled at her. It was arrogant. It was irresistible. Something heated and unfurled within her like a flower opening in the sun.

“I like you, too,” he said gently. “I like you very much.”

He touched her cheek and Margery could not help herself; she felt her whole body sweeten and sing at his words. It was impossible for her to withstand his charm. Her defenses felt like straw in the wind.

“Why did you come to find me?” She could hear that her tone had lost its sharpness.

“I wanted to thank you for returning the cravat pin,” Henry said. “I hope it did not cause any difficulties for you with Lady Grant. I would not have wanted you to get into trouble.”

Margery smiled. His concern for her made her feel warm and cherished. It was a new sensation. Jem was a protective brother but he did not make her feel as special as she did now.

“Thank you,” she said. “That is kind of you.” She smiled. “There was no difficulty. Lady Grant was only grateful that your lost property had been found. She is the best of employers. All the ladies I have worked for have been so kind—”

She stopped, aware of the smile in Henry’s eyes, wondering why she was telling him so much. She was not usually so open. Disquiet stirred in her as she realized the extent of her danger. Henry was too charming and too easy to talk to, and she was too inexperienced to deal with him. She should run now, while she still had the chance.

“Thank you for your thoughtfulness,” she said quickly, “and for not giving me away to Lady Grant.”

Henry shook his head. “I’d never do that.” There was warmth and sincerity in his tone. Margery’s pulse fluttered.

“You could have sent a note,” she said. “There was no need—” She stopped abruptly as Henry took her hand again. Her breath caught in her throat. Her heart seemed to skip a beat.

“No need to see you again?” His thumb brushed her gloved palm and she shivered. She felt hot and melting, trembling on the edge of something sweet and dangerous. “But perhaps,” he said, “I am here by choice. Perhaps I am here because I wanted to see you.”

Margery closed her eyes against the seduction of his words. She wondered if she had run mad. Maybe there would be a full moon tonight to account for her foolishness. For she knew she was being very, very foolish. There was nothing more imprudent than a maidservant who succumbed to wicked temptation and a rake’s charm.

Her sensible soul told her to dismiss him and go straight home again.

Her wicked side, the part of her she had not even known existed until Henry had kissed her, told her that this was just a small adventure and it could do no harm.

She took the arm that he offered and they started to walk again, more slowly this time, her hand tucked confidingly into the crook of his elbow. She had thought it would feel like walking with Jem or another of her brothers. She could not have been more wrong. Even through the barrier of her glove, she could feel the hardness of muscle beneath his sleeve. The sensation distracted her; she realized that Henry had asked her a question and she had failed to answer.

“I beg your pardon?”