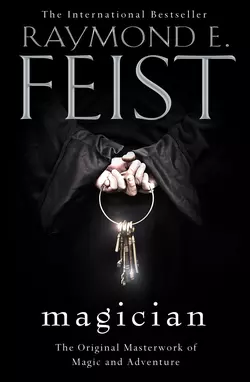

Magician

Raymond E. Feist

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческое фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 581.30 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Magician, available in ebook for the first time, is a masterwork of magic and adventure.The whole of the magnificent Riftwar Cycle, by bestselling author Raymond E. Feist, is now available in ebookThe world had changed even before I discovered the foreign ship wrecked on the shore below Crydee Castle, but it was the harbinger of the chaos and death that was coming to our door.War had come to the Kingdom of the Isles, and in the years that followed it would scatter my friends across the world. I longed to train as a warrior and fight alongside our duke like my foster-brother, but when the time came, I was not offered that choice. My fate would be shaped by other forces.My name is Pug. I was once an orphaned kitchen boy, with no family and no prospects, but I am destined to become a master magician…Magician is the first book in Raymond E. Feist’s acclaimed Riftwar Saga. The trilogy continues with book two, Silverthorn.