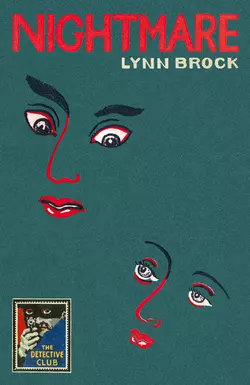

Nightmare

Lynn Brock

Rob Reef

Driven to madness by the cruelty of a small group of people, a young novelist sets about taking murderous revenge.Simon Whalley is an unsuccessful novelist who is gradually going to pieces under the strain of successive setbacks. Brooding over his troubles, and driven to despair by the cruelty of his neighbours, he decides to take his revenge in the only way he knows how – by planning to murder them . . .Lynn Brock made his name in the 1920s and 30s with the popular ‘Colonel Gore’ mysteries, winning praise from fans and critics including Dorothy L. Sayers and T. S. Eliot. In 1932, however, Brock abandoned the formulaic Gore for a new kind of narrative, a ‘psychological thriller’ in the vein of Francis Iles’ recent sensation, Malice Aforethought. Advertised by Collins as ‘one of the most remarkable books that we have ever published’, the unconventional and doom-laden Nightmare provided readers with a disturbing portrayal of what it might take to turn an outwardly normal man into a cold-blooded murderer.This Detective Story Club Classic is introduced by Rob Reef, author of the ‘John Stableford’ Golden Age mysteries, who finds philosophy at the heart of Brock’s landmark crime novel.

NIGHTMARE (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1932

Introduction © Rob Reef 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Francis Durbridge asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137779

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780008137786

Version: 2017-09-27

Dedication (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

TO MY WIFE

All the characters and incidents of this novel are entirely fictitious.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u9eb84fd4-a96e-5e33-8677-d8a306c846c5)

Nightmare (#ub5da915c-311c-5a83-b83e-8a083cd2e2f0)

Title Page (#u82140784-ceb9-5b82-bf0b-36a0c970cf27)

Copyright (#uf2533087-0a52-5035-9320-c87e976d4d4d)

Dedication (#u7b1fcc4b-6530-578e-8f0e-69d50a07a9e2)

Epigraph (#ubb34b6ea-5e1c-5b66-9eb4-34e04477a4c7)

Introduction (#ub10f930e-e817-5833-bc13-42c7a6baa4f7)

Chapter I (#ua1a44bed-dfc1-51a5-813d-8a80bb73b844)

Chapter II (#u4e86dc94-6dc9-5e6e-b686-6bfdb3101716)

Chapter III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter V (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

Lynn Brock’s Nightmare is not a regular Golden Age offering. Its bleak atmosphere bears comparison with noir fiction and the disturbing, almost absurd, hopelessness of its main characters reminds one of protagonists in plays by Samuel Beckett. From a purely formal point of view, Nightmare is most comparable to the fiction structure of inverted detective stories like Francis Iles’ Malice Aforethought or Freeman Wills Crofts’ The 12:30 from Croydon. In all these books, published in the early 1930s, one can follow the genesis of a murder shown from the perspective of the perpetrator. They all paint a gloomy picture of the human condition, but while Iles and Crofts develop sophisticated studies in psychology in their tales, Brock seems to motivate his Nightmare from an even darker and deeper source.

To those who know Brock’s more traditional Colonel Gore detective novels, this ambitious book will come as a surprise. For all the others not so well acquainted with the author, it seems appropriate to start with a brief biographical outline.

Lynn Brock was a pen name used by Alexander Patrick McAllister, an Irish playwright and novelist born in Dublin in 1877. He also published using the pseudonyms Henry Alexander and Anthony P. Wharton. Alexander, or Alister as he was known in the family, was the eldest son of Patrick Frederick McAllister, accountant to the port and docks board in Dublin, and his wife Catherine (née Morgan). Educated at Clongowes Wood College, he later obtained an Honours Degree at the Royal University and was appointed chief clerk shortly after the inception of the National University of Ireland. At the outbreak of the First World War, McAllister enlisted in the military. On July 21, 1915 he went to France, where he served in the Motor Machine Gun Service of the Royal Artillery. Wounded twice, he returned to Dublin in 1918 and resumed his occupation as a clerk of the National University of Ireland. He married the same year. Once retired on a pension, McAllister and his wife Cicely (née Blagg) settled in London before later moving to Ferndown near Wimborne in Dorset where he lived many years and died at the age of 66 on April 6, 1943.

In Dorset, McAllister wrote his first detective novel at the age of 48 under the pseudonym Lynn Brock. This work, The Deductions of Colonel Gore (1926), became a huge success. Many of his later novels featuring his title hero-detective were often reprinted and widely translated. His complex plots and witty style won the praise of Dorothy L. Sayers, T.S. Eliot and S.S. Van Dine. Against this background, his publishers at Collins had perfectly justified high expectations for Nightmare (1932), which they advertised as ‘one of the most remarkable books we have ever published.’ Yet they would be disappointed. Nightmare never saw a second edition, and it was Brock’s first crime novel not to be published in the US.

Though not a success in his time, Nightmare is still a fascinating story and, from the perspective of literary history, his publishers’ statement seems to be not entirely wrong. Reading Nightmare not as another psychological crime novel with a missing twist at the end but rather as a tragedy of the human condition itself allows interpretation of the work as what may be the first philosophical crime novel. For this reason, it may be considered a milestone in crime fiction.

To explain this seemingly surprising hypothesis, it is necessary to take a closer look at McAllister’s career as a writer, which did not start with the first Colonel Gore mystery in 1926. McAllister first made a name for himself twenty years earlier when his play Irene Wycherly, written under the pseudonym Anthony P. Wharton, became a big success in London and on Broadway. In 1912/14, his celebrity reached its peak when At the Barn (later made into a silent movie called Two Weeks in 1922) was staged in theatres on both sides of the Atlantic. Many plays and premieres followed, the last of which was The O’Cuddy, staged shortly before his death. However, neither of these could revive his earlier fame.

Why is it then worth considering his career as a playwright? Because it shows his intellectual origin as a writer. Lynn Brock, one of the author’s alter egos, was much more akin to George Bernard Shaw, T.S. Eliot and Frank Wedekind than to Agatha Christie, Anthony Berkeley or Freeman Wills Crofts. As with many turn-of-the-century pre-Freudian artists and writers, McAllister was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. In Schopenhauer’s principal work The World as Will and Representation (1818), the philosopher describes life as a dream motivated by an essence called ‘Will’—a mindless, aimless, non-rational urge at the foundation of everything including our instinctual drives. The world as ‘Will’ is an endless striving and blind impulse, devoid of knowledge, lawless and meaningless. There is no God, and there is neither good nor evil. The ‘Will’ causes a world of permanent struggle where each individual strives against every other individual in a ‘war of all against all’, and where daily life is suffering, a constant pendular movement between pain and boredom with misfortune in general as a rule. This world-as-representation is a nightmare for all individuals, staged by the ‘Will’ for his eternal self-involved entertainment.

It is this nihilistic and gloomy worldview that motivates Lynn Brock’s Nightmare. Bookended by the appearance of a gramophone playing music—the only art that, according to Schopenhauer, shows the metaphysical ‘Will’ itself—the story follows the tragic misadventures of Simon Whalley and a handful of other characters trapped in an ominous house community revealing the ‘war of all against all’ and individual suffering in a nutshell.

Though Whalley’s life bears some resemblance to McAllister’s biography as a playwright, the whole tale has a surreal quality. There are no distinguishable villains or heroes. All of the characters are driven by the same sinister force towards an abyss of despair, gently oscillating between daydreams of fresh starts and the inevitable nightmare-like realization of the impossibility of those intentions. All of the protagonists are doomed but Whalley, worst-hit by the cruelty of some of his neighbours, succumbs to the pressure and prepares himself for murderous revenge. The following events are predictable, and the ending is as gloomy as the setting of the story against the backdrop of the Great Depression.

What makes Nightmare truly genuine is its subtext. The plot not only unveils the motive of the crimes committed, it leads one to the metaphysical core of the human condition itself. Throughout the book the characters develop an uncanny consciousness of their nightmare-like existence in an endlessly striving and meaningless universe. They feel that ‘Life itself is a silly faked-up old story’, a ‘bitter, merciless struggle’. They anticipate that ‘everything that has been is for ever’ and one ‘might have to start all over again at the end of it’. Such half-hidden maxims of Schopenhauer’s philosophy make Lynn Brock’s Nightmare an extraordinary and notable contribution to the Golden Age of crime and detective fiction, and it is to be hoped that this new edition might help to bring it up for discussion again.

ROB REEF

March 2017

CHAPTER I (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

1

IT was a sullen, sultry afternoon in early June—the unsatisfactory June of 1931—and after lunch Mr Harvey Knayle, who hoped to play tennis at the Edwarde-Lewins’ after tea, had retired to his bedroom for a nap. At half-past three he still lay there on his bed, slumbering soundly in the twilight of down-drawn blinds, clothed, beneath a gay dressing-gown, in gay pyjamas. For Harvey Knayle had reached an age at which an afternoon nap was a thing to be taken seriously and with all possible ease and comfort.

He was a fresh-coloured, clean-shaven, spare little man of fifty precisely, with thinning, carefully-groomed blonde hair, a high forehead, a longish aquilinish nose, good-humouredly sardonic lips, and a cleft chin. The combined effect of these details was agreeable, restful, and unobtrusively distinguished, as became the personal appearance of anyone bearing the name which was his.

For the Knayles were one of the oldest families in Barshire and intricately linked with many others of the same standing all over the west country. It is true that the particular branch of the family to which Harvey Knayle belonged had declined considerably, financially, during the past century. None the less, as things had fallen out with the help of a war, the little man who lay there sleeping peacefully, with one cheek cupped in a well-shaped hand, his knees tucked up, and a smile of child-like content upon his face, was separated by but three lives from a baronetcy, one of the largest estates in the county, and an income of fifty or sixty thousand a year. There was no likelihood whatever that he would become the actual possessor of this dignity and affluence. But it was a source of mild gratification to him that a large number of people—without ill-will towards the three healthy obstacles—quite sincerely hoped that somehow, some day, he would. Meanwhile he had an income of something over two thousand a year from sound investments, hosts of friends, excellent health, and an unfailing interest in the game of life. More especially, as will be seen—this was one of the many reasons of his social popularity—in the games played by life with other people.

For, in point of fact, his own existence had been perfectly uneventful. From Oxford he had returned to his father’s house near Whanton and for a few years had lived the life of a country gentleman. But at thirty he had quickly wearied of unadulterated rurality and had migrated to Rockwood, Dunpool’s most select residential suburb, where, on the frontier between town and country, he had lived ever since in bachelor content. There he had found new friends and had still been within easy reach of old ones. He danced satisfactorily, was a sound bridge-player, a reliable and good-tempered performer at tennis and golf, a sometimes brilliant shot, a good horseman, and a keen fisherman. He knew everyone in the neighbourhood worth knowing and knew everything worth knowing about them. If not a brilliant conversationalist, he was an excellent listener; if he rarely strove to say an amusing thing, he never said a malicious one. Finally he was a Knayle. And so the past twenty-five years of his life (during the War he had acted very efficiently as Adjutant of a Remount Camp close to Rockwood) had flowed tranquilly along a rut of comfortable sociability, pleasantly varied by annual trips abroad. He had found during them plenty of time to take an interest in other people—an occupation which was, indeed, the principal pleasure of his life.

It is necessary, in view of subsequent events, to define his position on that drowsy afternoon, geographically, with a little greater accuracy.

The bedroom in which he lay was situated on the ground floor of a large four-storey house—its number was 47—in Downview Road, one of the main arteries of Rockwood. The house, detached, and formerly, like its fellows, the dignified and undivided residence of a succession of well-to-do tenants, had come down somewhat in a post-War world and had been converted into four flats, the upper two of which were reached by a steeply-pitched outer staircase of concrete built on to one side wall. At the moment the basement flat, beneath Mr Knayle—one went down a little flight of steps from the front garden to its front door—was let to a Mr Ridgeway, a solitary, elderly man, apparently without occupation. The first-floor flat, above Mr Knayle, was occupied by a Mr and Mrs Whalley. And the top flat, above Mr Whalley’s, was tenanted by a Mr Prossip, his wife, and his daughter.

Mr Knayle, as has been said, liked Rockwood. It was, of course, two hours by rail from London. But, though he ran up to London very frequently and had many friends living there, he was always glad to get out of it. Dunpool, he admitted, though it was still the sixth city of England, was a dingy, untidy, shabby-looking place, solely interested in the making of money, doggedly provincial in outlook. But Rockwood was picturesque, dignified, quiet, had agreeable literary and historical associations, and was notoriously healthy. There was a pleasant variety in the people one knew there—the commercial magnates of the city, people connected with the county families, retired Service people of all sorts, the men from the college and the university, people who moved about the world and did all sorts of things. It was true that a good deal of shabby gentility was hidden away in lodging-houses and boarding-houses, and that, since the War, many houses where one had dined and danced had been converted into flats in which curious-looking people lived now. But curious-looking people were everywhere now. One could always avoid seeing them. On the whole Mr Knayle thought Rockwood as good a place as any to live in. At any rate, everyone knew who one was.

At half-past three, as he had arranged, Mr Knayle was awakened by the entry of his servant, Hopgood, and opened his eyes—bright blue eyes—permanently a little surprised, but with a birdlike quickness of movement and fixity of gaze. They watched Hopgood let up the blinds, observed that outside the windows the gloom of the afternoon had deepened to definite menace, and closed themselves again with resignation.

‘No tennis this afternoon, I’m afraid, Hopgood. Looks rather like a thunderstorm, doesn’t it?’

Hopgood, a neat, stolid, oldish man, turned to face his employer. He had been in Mr Knayle’s service for many years and was permitted, upon reasonable occasion, a reasonable liberty of speech.

‘Well, all I can say, sir,’ he replied, his usually colourless voice tinged with acidity, ‘is that if there is one, I hope a good old thunderbolt will plop into the top flat of this house.’

Mr Knayle, opening his eyes again, smiled sympathetically upon his retainer’s grimness of visage and, divining its cause, cocked an ear to catch a remote wailing which had of late grown familiar.

‘Mr Prossip’s gramophone busy again, I hear.’

So far Hopgood, emulating his master’s stoicism, had refrained from complaint of the annoyance to which they had both been subjected for a considerable time past. But, having made up his mind to complain of it, he had entered the room determined to do so, after his fashion, thoroughly.

‘Busy, sir?’ He produced from a pocket a befigured slip. ‘I’d like to ask you, sir, if you have any idea how many times that gramophone plays that same old tune in the day?’

‘None whatever,’ replied Mr Knayle placidly, inserting his neat legs into the trousers with which Hopgood had supplied him. ‘Have you?’

‘Well, I’ve been working it out this afternoon, sir, timing it and taking the average. Say it takes four minutes to play the tune—including stops—though there’s not many stops once it starts. Very well, that’s fifteen times it plays it in an hour. In the morning it plays it from eight o’clock to ten o’clock. In the afternoon it plays it from half-past one until four. And at night it plays it from ten to eleven. That’s five and a half hours a day. If you multiply that by fifteen, sir, you get it that it plays it eighty-two times in the day. And it’s been doing that now for seventeen days. What I make of it, sir, is that since they began that silly game up there in the top flat—last Saturday week it was—their gramophone has played that same blessed old tune fourteen hundred times.’

He put away his memorandum with lips tightened impressively and helped Mr Knayle into his coat.

‘Quite a number of times,’ Mr Knayle agreed. ‘Involving quite a large amount of labour for someone—I should surmise some more than one.’

‘They all have a go at it, sir, I reckon. But it’s that brazen young trollop of a maid of theirs that does most of it. I hear her running out of her kitchen to start it up when it stops.’

‘Why hear her, Hopgood?’ asked Mr Knayle soothingly. ‘Or it? I don’t.’

‘You may say you don’t, sir—but you do. How can you get away from it, with the noise coming down through the well of the staircase like through a flue? I believe they’ve put the gramophone right over it, on purpose.’ Hopgood’s voice, approaching now its real purpose, invested itself with respectful reproach. ‘I wonder you don’t make a complaint to the landlord, sir. It’s disgraceful that a quiet gentleman like you should be worried this way from morning to night. The fiddle was bad enough by itself; but this—well, it’s sheer torture, sir, that’s what it is, sheer downright, cold-blooded torture. Any other gentleman would have complained long ago.’

But, while he surveyed his completed toilette in a long glass critically, Mr Knayle put a kindly foot upon this attempt to stampede him, and scotched it firmly.

‘Never allow yourself to be worried, Hopgood. And never, never let other people know that they can worry you. I admit that the same tune played fourteen hundred times begins to pall a little. But it might have been played twenty-four hundred times. The sound is hardly audible down here—unless you listen for it. Let us console ourselves by the reflection that other people are having a much worse time of it than we are. A great help, that—always.’ He looked towards the windows. ‘Yes, there’s the rain. I had better get off, I think. Has Chidgey brought the car round?’

As Mr Knayle drove off in his smart coupé to spend the afternoon with his friends, the Edwarde-Lewins, he glanced up casually towards the first floor. But there was nothing to see there. Perceiving a showy-looking young woman in coquettish apron and cap standing at one of the windows of the top flat smoking a cigarette, he smiled. The lease of his own flat would expire in September, and he had all but decided, before falling asleep that afternoon, to write that evening to the landlord giving him the agreed three months’ notice that his tenancy would not be renewed. He would be away for the greater part of those three months, so that the persistency of the Prossips’ gramophone, which, he was resolved, should not trouble him in the least, was of no concern to him.

He was quite determined that it should not trouble him in the least. During the past few months, he had noticed, a lot of people whom he knew—quite good-tempered, placid people, formerly—had developed a marked tendency to allow little things to worry them and make them irritable. He had noticed in himself a tendency to attach too much importance to trifling annoyances—a lost golf-ball, or a dud razor-blade, or a little tactlessness on the part of a friend—and had occasionally found it necessary to check it with some firmness. He assured himself now, therefore, that though stupid and childish and, of course, annoying for Mr and Mrs Whalley (a pity, though, that Whalley should allow himself to take it so seriously) the dogged perseverance of the Prossips’ gramophone struck him as rather amusing.

As, of course, it was.

Seated beside Mr Knayle, his chauffeur, Chidgey, had also glanced up to the windows of the top flat and smiled faintly. He knew all about the Prossips’ gramophone and thought it a game. His smile faded almost at once, however, and his rather pleasant face became gloomy. The gear-box and the back-axle of the car should both have been refilled last week. He had not refilled them last week, nor since. He couldn’t explain to himself why he hadn’t, except that it was a messy job and that he had felt disinclined to do it. He had been with Mr Knayle for three years and had always taken anxious care of the two new cars which his employer had acquired in that time. It worried him that he had had this funny feeling lately that he didn’t want to do jobs about the car that were a bit troublesome and messy—a sort of feeling that it wasn’t worth bothering about doing them.

2

At all events Agatha Judd—the brazen young trollop of the top flat—was quite sure that the gramophone’s persistency was amusing—the most priceless lark, in fact, that had so far diverted her light-hearted existence.

As Mr Knayle’s car disappeared from her view round the curve of Downview Road, once more the gramophone blared triumphantly the long-drawn closing note of ‘I can’t give you anything but love, Baby’. The needle slid off the record and the abrupt succeeding silence aroused her from her never-wearying contemplation of the passing traffic. But the disturbance caused her no resentment, though for two hours past, without intermission, at intervals of a few minutes, precisely similar disturbances had called her away from her window. Jamming a cigarette between her full, bedaubed lips, she flitted with hurrying eagerness out of the kitchen and along the little central corridor of the flat to where the gramophone stood on a small landing or platform at one side of the three steps descending from the corridor to the hall-door. Having started the needle once again upon its pilgrimage over the worn record, she wound up the instrument recklessly and then stood for some moments listening, her bold hazel eyes narrowed to exclude the smoke of her cigarette.

She was a slim, shapely girl of twenty-four or five and, despite her hardy allure, her powdered skin, and her salved lips, a noticeably good-looking young creature, obsessed by her own personal appearance, inefficient and lazy, equipped with the mentality of a Dunpool slum-child of ten, and possessed by a never-flagging determination to extract a bit of fun from life. At that moment, as has been said, despite the unavoidable monotony of the means, she was extracting a quite satisfying bit of it. As she stood listening, blissfully unaware of the grim fate whose scissors were already opening above her sleek little head, she smiled with vivid pleasure.

Stooping to the gramophone again—it rested on the bare boards of the little landing, whose carpet had been rolled back—she laid a finger against the edge of the record, increasing and relaxing its pressure alternately. The melody dissolved into hideous ululations, wailing and howling in dolorous insanity. She laughed softly while she continued this manipulation for a minute or so and then climbed over the balusters—relics of the former interior staircase of the house, removed at the time of the conversion—which enclosed the landing on two sides. Bracing herself, she sprang into the air and descended upon the boards with her full weight. The hollow, echoing reverberations which resulted—for the flooring beneath her high-heeled shoes consisted merely of match-boarding—widened her smile. She reproduced it with deliberation half a dozen times, then wound up the gramophone again, restarted the needle, climbed back over the balusters and, crossing the passage, entered the flat’s sitting-room.

In there Marjory Prossip, a heavily-built, sullen-faced young woman of thirty, sat bent over the construction of a silk underskirt. She turned her large, elaborately-waved head as Agatha entered and rose silently from her chair. For a moment of preparation the two faced one another in the middle of the room, then, together, they sprang ceilingward and descended upon the carpet with a violence which set the windows a-rattle. This athletic feat having been repeated several times, Miss Prossip reseated herself with her work and Agatha returned humming to the kitchen, pausing along the way to start the gramophone once more. No word had passed between them. Agatha had not troubled to remove her cigarette from her lips.

For five minutes, measured by a clock upon which she kept a watchful eye, Miss Prossip plied her needle industriously. She rose then and, joined by Agatha, hopped on one foot along the corridor, into a bedroom at the end of it, around the bedroom three times, and then back along the corridor to the sitting-room, where, rather blown, she resumed her sewing. No slightest change of expression manifested itself in her sulky, sallow face while she performed these curious gymnastics, which she executed with the solemnity of a ritual. In the agile Agatha, however, the awkward heaviness of her broad-beamed superior evoked a special gaiety. As she hopped behind Miss Prossip’s labouring clumsiness, she giggled happily.

Another five minutes passed and again Agatha entered the sitting-room, having again attended to the gramophone. Miss Prossip arose and faced her silently. Then, together, they sprang ceilingwards.

Some time later Mr Knayle had the curiosity to make some enquiries about Miss Prossip. He learned that she had always been regarded by people who knew her as of perfectly normal intelligence and general behaviour, had been educated at the local High School, (a celebrated one) where she had been considered by her mistress a rather clever girl, if somewhat difficult and moody, was passionately fond of music and played the violin with talent, and, in general, had been considered a perfectly normal and sensible person. Mr Knayle himself had frequently encountered her in the front garden and exchanged ‘good mornings’ and ‘good afternoons’ with her. His personal estimate of her, until the outbreak of the present hostilities, had been that she was a perfectly sane, if exceedingly unattractive, young woman. Slightly more intent observation of her, in the course of the past few weeks, had afforded him no reason to revise this opinion. Nothing that he ever subsequently learned about her or her family history ever afforded him the slightest reason to revise it. And so the fact is to be accepted that Marjory Prossip was an intelligent, well-educated, well-behaved, industrious, quiet girl of thirty, an accomplished violinist, and very fond of the kind of music which abhors tunes and never says the same thing twice.

3

In the sitting-room of the first-floor flat, directly beneath those four prancing feet, Simon Whalley sat at a small oval table near the open windows. He was tallish, black-haired, grey-eyed, like Mr Knayle, clean-shaven, in his middle-forties and rather noticeably thin. The well-cut lounge suit which he wore fitted him excellently and yet had the effect of having grown a size too large for him. On the table were an ash-tray, half full of cigarette ends, and a writing-block. Three sheets had been detached from the block and lay crumpled-up on the carpet beside his chair—a severely un-easy chair, imported from the dining-room. On a fourth sheet, beneath the carefully-written heading ‘CHAPTER XVII’, he was drawing with a fountain-pen a design of intricate and perfectly unmeaning arabesques.

Over this task, which had occupied him for the past half-hour, he was bent in concentrated absorption, thickening a curve here with nicety, rounding off an angle there, finding always a new joining to make or a new space into which to crowd another little lop-sided scroll or lozenge. At regular intervals, automatically, his left hand removed a cigarette from his lips, tapped it against the ashtray and replaced it. Whenever he lighted a new cigarette from the old one, his eyes made a curiously methodical and concerned journey round the room, beginning always at the window-curtain to his left hand and travelling always round to the armchair, which stood just beside the oval table, at his right. As they made this circuit slowly, they examined each object upon which they rested with an anxious intentness. From the armchair they glanced always to a small, stopped clock on the mantelpiece and then returned, slowly and reluctantly, to the writing-block.

The room was a large, rather low-ceilinged one, quite charming to the cursory eye with its biscuit-coloured wall-paper, bright carpet and curtains and rugs and chintzes, rows of dwarf book-cases, easy chairs and bowls of roses. It was sufficiently high up to escape serious molestation by the noise of Downview Road’s voluminous summer traffic. Its windows looked out across the road, over the wide, pleasantly-timbered expanse of Rockwood Down. It was a friendly, cheerful, comfortable room, and Whalley hated it and everything in it with a hatred that was all but horror.

As he sat elaborating his futile design, his mutinous brain, refusing stubbornly to perform the functions which had once been its delight and relief, persisted in exploring, for the hundredth-thousandth time, the emotion of nauseated distrust and apprehension which the room now evoked in him whenever he entered it or even looked into it. No aim directed this vague, depressed analysis; no satisfaction or hope of remedy resulted from it. It proceeded always, however, he had observed—for it had long ago become a subconscious activity, so persistent as to attract his uneasy attention—along the same line.

It began always with the furtive, secret dinginess and decay that underlay the room’s superficial brightness and freshness—began, oddly, always with the same window-curtain.

Pretty curtains. But they had been up for two years now. When you shook them you found that they were thick with dust. They had faded a lot. There was a small tear in the left-hand one, at the bottom. Bogey-Bogey’s work.

The windows. It must be two months at least since the windows of the flat had been cleaned. Seven-and-six … but they must be done. A nuisance, the window-cleaner, in and out of the rooms with his bucket and his sour-smelling cloths and his curious watching eyes. And then there was that broken sash-cord. And the cracked pane.

The roll-top desk. Lord, what a litter it was in! All those pigeon-holes … full of dust and rubbish. What an uncomfortable brute of a thing it was to sit at. Much too high and too narrow. And your legs were always cramped. He had paid fourteen pounds for it, and had never succeeded in writing a sentence at it …

The chintz covers. They had faded badly, too. All of them wanted cleaning, especially those of the armchairs, which were perfectly filthy …

A leg of that arm-chair wanted repairing.

The rain last winter found its way through the wall up there, above the fireplace, cracked the plaster, and stained the paper. That watercolour below the stain had begun to mildew and blotch …

The fireplace would have to be seen to before the autumn; its back had burnt out, and a lot of the tiles had cracked. The chimney must be swept, too, before the autumn. That would mean that the whole room would have to be turned topsy-turvy in preparation for the sweep and cleaned right out when he had finished. A woman would have to be got in to do that job. Ten shillings. And the room unusable for the whole day.

The carpet. All right until you looked closely. Then you saw that it was dotted all over with little stains and thickly covered with Bogey-Bogey’s hairs. It would have to come up and go to the cleaners, also. And one couldn’t use the room without a carpet.

The Crown Derby set on the Welsh dresser. Thick with dust. A two hours’ job to collect it, piece by piece, and carry it out to the kitchen and wash and dry it and carry it back and arrange it on the dresser again. He had smashed a cup last time he had done that job, three or four—no, it must be six months ago—before last Christmas—and spoiled the set. Clumsy brute, always smashing things. It had worried him ever since, whenever he had looked at it, to think that the set was a cup short.

The portable … God, how he hated the wireless now—the fatuous voices of the announcers—the maudlin, insatiable music … Music … God—

All those infernal dusty, stale, useless old books. Three or four hundred pounds worth of rubbish—one probably wouldn’t get five pounds for the lot if one tried to sell them and get rid of them. Neither he nor Elsa had opened one of them for years. And what a business it had been moving them about. What a business it would be when they would have to be moved again. And they would have to be moved again.

The settee. Ruined by the dog’s paws. That must be re-covered—for the dog’s paws to filthy again.

The rugs. All faded, all soiled and stained and ragged at the fringes. More work for the cleaners.

That armchair. The springs gone and a castor off. He had been intending to fix that castor for over a year.

Expense—disturbance—trouble. And all for nothing. Everything was wearing out—going. Nothing would stop its going. In a few months, after all that fuss and upset, everything would be dirty and dingy again—older—shabbier. Hopeless to try to keep things decent with clouds of dust coming in from the road all day long and a dog messing about from morning to night and no servant. Hopeless—mere waste of time. Time—God, how the time flew away. The sitting-room alone took a couple of hours to do—even scamping the job. And next morning it looked as if it hadn’t been done for weeks.

And yet one couldn’t live in a piggery—one couldn’t allow Elsa to. All those confounded things must be cleaned. All those confounded small jobs must be done and paid for.

For that matter, the room would have to be done up very soon—ceiling, wallpaper, and paintwork. All of them were in a bad way, and would be definitely shabby if they were let go until the spring. If the sitting-room was done, the passage and the bathroom would have to be done at the same time. One job must be made of the lot—one upset. More argument and discussion and difficulty with that surly, tricky brute of a landlord—more worry. Probably he would refuse again to do the work. Even if he did consent to do it, it would mean all sorts of nuisance—the greater part of the flat out of action—workmen about it all day long—noise, smells, mess. Elsa and he would have to sleep and meal at an hotel or somewhere. More expense. And one or other of them would have to be about the flat while the workmen were in it. Lord, what a nuisance.

How pretty the room had looked when they had settled down in the flat two years ago. How sure he had felt, that first afternoon in April, 1929, when he had seated himself at the just-delivered roll-top desk, that, in that friendly, comfortable, peaceful work-room, his brain would come back again, tranquilly and obediently, to the playing of its old tricks.

That damnable, cheerful-faced clock on the mantel-piece. How many hours of bitter defeat and impotent self-reproach it had hurried away, eagerly, irrevocably. For two years of hours, each a little swifter than the last, each a little nearer to panic-speed, it had hustled him and bustled him and mocked his flurry and his failure. Cursed, smug thing … Extraordinary how loud its faint tick had grown—how long he had failed to detect its power to irritate and distract him—how instant had been the relief when, one afternoon six weeks or so back, a sudden impulse had caused him to jump up from his table and stop it. On that afternoon he had written nearly a whole chapter—the chapter which for over three months had refused to begin itself. In the following three weeks he had succeeded in writing four more chapters, turning out four thousand words a day, still with some difficulty, but regularly. The spell had seemed broken at last. For that brief space the sitting-room had worn again the guise of its old encouraging friendliness. He had taken to hurrying in there after lunch, leaving Elsa to wash up unaided.

And then this damnable, idiotic, maddening trouble with the Prossips had begun—just when there had seemed at last, a hope …

He turned his head towards the door of the room. A thick portière was drawn across it and, actually, the sound of the gramophone was a faint and remote whining. No portière, however, could shut out its real torture, the malice of its persistency; for Whalley’s ears that faint, distant whine was a savage, raucous clamour, hammering at their drums. For a little space he remained, half-turned in his chair, listening to it with rigid intentness. Then, as a heavy thump shook the ceiling above his head he flung down his pen furiously, sprang to his feet, and stood with both hands clenched before his face, glaring upwards.

The paroxysm of anger passed almost instantly—before a second thump followed the first. But he remained for a space surprised by its violence and by its sudden complete obliteration of his self-control. It had produced in him for a moment an absolutely novel sensation—a sensation of being on the point of surrendering his will and his consciousness to some overpowering, hostile, dangerous force. A little like the sensation when one was just about to surrender to an anæsthetic—but much more violent—much more eager to leave behind all the things one knew. A dangerous sensation. For a moment he realised he had been upon the point of shouting—bellowing like a mad animal. He discovered that his legs were trembling a little at the knees and that his hands were still raised absurdly in the air, clenched in front of his face. When he dropped them he looked at them—he had a trick of looking at his hands—he saw that their palms were moist with perspiration.

Ridiculous. Grotesque. Shaking legs and sweating hands. That sort of thing would never do. That sort of thing, he must remember, was just the sort of thing those sluts upstairs hoped he would do—allow the business to get on his nerves and shout and slam doors and bang things about. Thank Heaven he hadn’t shouted. Shout? Good God, he had never shouted at anyone in his life. All along, since this annoyance had begun, he had kept a close watch on himself, a tight grip on his temper. He had gone out of his way to shut doors quietly, to speak more gently to the dog. No slightest symptoms of resentment, he flattered himself, had rewarded those idiots in the top flat for all their trouble. No doubt they kept watch up there, too—listened—always hoping for some sound of anger or retaliation. Well, they had waited in vain—they would wait in vain.

Now, why on earth had that one particular thump had that strange effect upon him. They had been thumping and banging away up there for nearly three weeks now. He had heard hundreds of thumps. At least a hundred times a day, he supposed, he had heard a thump somewhere above his head. There—they were at it again now. But he was able to smile now—felt no anger whatever, merely an inclination to yawn. Yet that one particular thump, no louder than the rest, had swept away from him all knowledge of himself save a desire to shout madly. Funny. Too many cigarettes, probably. The afternoon was stuffy. And, of course, the thing had been going on for three weeks now.

The fountain-pen had rebounded from the surface of the table when he had thrown it down and, falling on the carpet had marked it with a small inkstain. An agitated dismay seized him. He clucked, hurried to the roll-top desk, reduced its disorder to chaos with searching hands, found at last a small piece of blotting-paper in a drawer and hurried back to go down on his knees over the stain. The ink had soaked into the pile of the carpet swiftly, however, and the blotting-paper proved of little avail. He picked up the pen with another cluck, and examined its nib solicitously. It had been Elsa’s first gift to him on the first day of their brief engagement—a pledge of the victorious future it was to have won for them. He smiled wryly as he rose to his feet again; there had been no victories.

Luckily, the pen had escaped damage. Laying it on the table, he tore off the bescrawled sheet of the writing-block and, having collected the crumpled debris from the carpet, rolled the result of his afternoon’s work into a ball and dropped it dejectedly into a waste-paper basket. One more afternoon gone—one more defeat—

Thump.

Furiously his face, its pallor flushing darkly, jerked upwards towards the ceiling. He shouted ragingly, ludicrously.

‘Stop it! Stop it, blast you! Stop it, I say!’

4

In the top flat, as if upon an awaited signal, Bedlam had broken loose. Trampling feet were charging from room to room; doors were banging; furniture was hurtling about; a whistle was screaming; a tray was beating like a war-drum; a bucket was rolling backwards and forwards along the passage. For just an instant after he had realised in stupefaction that his own voice had uttered those three cracked, strangled cries, Whalley had hoped that the noise of the traffic might have drowned them. There had been just an instant of silence save for the traffic and the whine of the gramophone. But then exultant triumph had burst forth above him, preluded by a first long-drawn blast of the whistle. The whistle was new. The enemy had made special preparation for the celebration of victory.

As he stood at the centre of the room, dismayed by his folly, he heard the handle of the door turn and saw the portière ruck and sway inwards as the door opened a little beneath it. He made no movement to draw it aside; for the first time his eyes were unwilling to meet Elsa’s. Lest she should edge her way in, he wiped his face hurriedly with his handkerchief in a vague attempt to obliterate its disturbance. His voice essayed bored amusement.

‘Having rather a field day upstairs, aren’t they?’

‘Beasts. Did you call?’

‘Call? No.’

‘Oh, I thought I heard your voice.’

‘No.’

It was his first lie to her—curt and clumsy. He eyed the portière uneasily, glad that it hid him from her clear, steady gaze. There was no suspicion in her voice when it spoke again, but it waited just too long before it did so. She knew that he had shouted, and that he had told her a lie.

‘You can’t possibly work with that awful row going on. Let’s take Bogey for a walk before tea.’

‘It’s going to rain. It’s raining already. Besides, I must do the kitchen.’

‘But you did it not a week ago, dear. Don’t bother about it today. Let’s chance the rain and go out.’

Yes. She had heard him shouting like a lunatic. He was certain now. Well, bad enough that she should know that he had shouted, but …

He hurried to the portière, pulled it aside and saw the slight, adored figure framed in the aperture of the partially opened door. Her unfathomable, enfolding smile fell upon his ruffled spirit like morning sunlight and banished all its anger and defeat and bitter self-reproach. He caught her in his arms and kissed her passionately before he blurted out his confession.

‘Yes. I did call out. I shouted up to them to stop—like an infernal ass.’

She patted his arm, offering him just excuse.

‘It really is rather awful this afternoon. But we’re going to keep on laughing at it, aren’t we, dear? Let’s go out. The kitchen can go for days still, quite well. And it’s such a job.’

He hesitated, for a moment disposed to yield. But just then, startlingly, the offensive upstairs developed a new activity. Behind Elsa, as she stood facing him in the passage, was the little landing—corresponding to that upon which the Prossips’ gramophone rested—covering in the well of the former staircase. Two of its sides were fenced in by surviving balusters, the other two by ugly partitions of painted boarding, the handiwork of the jobbing contractor who had carried out the ‘conversion’. One of these partitions formed the back of the Prossips’ coal-cellar, the greater part of which descended into the Whalleys’ flat. This frail wall, consisting of a single thickness of match-boarding like the landing’s floor, had suddenly been assailed by a wild bombardment, alarming in its abrupt violence. There was no need to speculate as to the nature of the enemy’s ammunition; each furious blow upon the boards was followed by the unmistakable sound of broken coal falling. Already, where the tonguing of the boarding had split away in places, tricklings of black dust had begun to find their way through, to fall upon the rug covering the Whalleys’ landing.

They stood for a little while staring at this visible invasion which, trifling as it was, held an outrage infinitely more acute than the total volume of all the outrageous noises which had assailed their ears during the past weeks. Elsa laughed at length. But for the first time her sense of humour had failed her, and her laugh was, she knew, a failure.

‘Idiots. Well, they’ll have plenty of slack for the winter. I must rescue my rug.’

She stole on tiptoe to the landing and rolled back the rug out of danger, then stole back to him. ‘I shan’t be a moment getting ready.’

Her husband did not appear to have heard her. He was still staring at the trickling coal-dust with a frowning, calculating absorption that made her catch at his hands anxiously.

‘You’re not going to do anything, Si? Don’t. It will only make things worse.’

He came out of his brooding reverie and laughed harshly.

‘Do anything? Yes. I’m going to wash the kitchen floor.’

‘Let me help you to move the things out. I’ve finished all my darning.’

But he twisted away from her, freeing himself from her hands impatiently. ‘No. Don’t worry me, Elsa. Just leave me to myself.’

Incredulously her eyes followed him, hoping that he would turn back to her. His hands—Simon’s hands—the gentlest, tenderest hands in all the world, had pushed her off—pushed her off quite roughly—so roughly that one of her elbows had struck the balusters behind her sharply. Oblivious of the deafening uproar that raged within a few feet of her, she strove with that unbelievable fact, refusing to believe it, trying to find excuse for its devastating reality. An intolerable sense of separation and loneliness fell about her like a dark mist. She became conscious of a little nervous tic beating at the corner of her mouth. With a determined effort she smiled, bracing her whole body with a deep breath.

The coppery glare that announced the near approach of the storm, passing in through the kitchen windows, reached her and detached her vividly against the darkness of the little unlighted passage. When Whalley turned at the bathroom door to ask: ‘Tea at a quarter to five—will that do? I shan’t finish until then,’ he saw her so, illuminated as if by a baleful spotlight. The whistle was blowing again now—in the coal-cellar, apparently—and its shrill screaming blended with the blare of the gramophone and the thudding smash of the coal in an orchestra of almost stunning viciousness. The small, trim, beloved figure, despite its erectness, seemed to him suddenly forlorn—menaced. A little chill passed between her and his eyes and made her indistinct. His heart missed a beat.

Absurd. He turned about again. Her ‘Of course, dear. Any old time,’ had been whispered along the passage to him laughingly. Unusual lighting effects had always affected his imagination strongly … his invincible, idiotic instinct to dramatise. As for shivers and palpitations, they were familiar enough. He went on into the bathroom, which he used also as his dressing-room.

When its door shut Mrs Whalley returned to the bedroom in which she had been working and, having arranged a number of freshly-darned socks and stockings in neat pairs, put them away in her work-basket, walked slowly to the wardrobe and halted before the long mirror set in its central door.

All her life, in moments of loneliness—before her marriage she had had many of them—she had found comfort and company in her own reflection. It confronted her now—at first reassuringly, extraordinarily unchanged by the strains and stresses of the past two years. Two tiny creases, one beneath each long eye (her eyes looked even longer than usual today, she noticed, and, because her jumper was jade and the light was dull, were bright bronze-flecked emerald) were only detectable when she bent forward until her nose all but touched the glass. There was no other line or wrinkle in the fresh smoothness of her skin, no trace of flabbiness or heaviness along the clean sweep of her jaws, about her resolute chin, or at the corners of her lips. Thank Heaven for that. She had always detested flabbiness of any sort. Her lips (she had never had any need to touch them up) had retained their warm red. Her teeth, save for an occasional stopping, had never given her any trouble. Her hair, without any doubt whatever, had grown brighter in colour and much thicker since, at last, Simon had consented to its cropping four years before. No danger of stoutness for her—another good fortune to be grateful for; she was thinner and lighter than she had been at eighteen. Making allowances for short hair and short skirts, that old, tried friend in the mirror had altered hardly at all in twenty years. If at all, for the better. She had been very lucky.

But as she continued her scrutiny, a vague distrust grew in her. There was some change today in that now detached and aloof image. Her eyes narrowed themselves as she searched for it. Where was it? What was it? Elsa of the mirror refused comfort and company today. Had withdrawn. Had—what? It was as if an Elsa who had been had suddenly stopped being and was looking out at someone else—someone different—someone who, she knew, would be very different. What was it? She frowned. After all—ultimately—one was quite alone—

She turned away from the glass and, moving to the narrow space between the two trim beds, stooped and raised the rug which she had spread over Bogey-Bogey’s basket that, as was his desire, his afternoon sleep might be enjoyed in darkness. Bogey-Bogey appeared, a silken-coated black cocker, curled in a warmly-smelling knot. He had not been asleep; his tail was wagging slowly and his lustrous eyes were wide open. They regarded her with solemn reproach and then, revolving fearfully towards the uproar of the passage, refused to be enticed back to her. Nor would he raise his head from his paws. Even a kiss and the magic word ‘Walky-walk’ evoked from him merely a yawn and a slight increase in the tempo of his tail.

A little sharply, Mrs Whalley routed him out of his basket.

‘Now then, young man. Pull yourself together and get that tail up.’

But Bogey-Bogey’s nerves had been sorely tried recently and the new noise in the passage daunted his small soul beyond trust even in his mistress. He yawned again miserably, and then retired under her bed, reducing himself several sizes. In a vain attempt to dislodge him from this retreat, she struck her nose forcibly against the bed’s iron underframe. A little warm gush of blood descended her chin and when she scrambled to her knees she saw that her jumper—a recent, long-considered purchase—was grievously stained. As she rose to hurry to the wash-stand and sponge away this defilement, holding her already saturated handkerchief to her nose, a crashing peal of thunder, apparently directly above the house, joined itself to the Prossips’ orchestra. Bogey-Bogey yelped shrilly. Mrs Whalley realised that she had a violent headache.

‘Well, well—’ she said aloud and, to her dismay, was suddenly overcome by a gust of dry, choking sobbing. She went on, however, towards the wash-stand, her head thrown back as far as it would go, her free hand guiding her. The jumper must be saved, because it had to last her through the summer. If it was to be saved, the blood must be sponged off at once. Most urgent necessity. Simon, who was liable to come into the bedroom at any moment now that he had abandoned the attempt to work, must on no conceivable account know that misfortune had befallen his birthday gift to her. Any damage done to anything upset him so, now. His hands—Simon’s hands—had pushed her away.

At that moment, as it happened, four other people who resided in various parts of No. 47 Downview Road were thinking about Mrs Whalley.

Upstairs, Marjory Prossip, who hated her passionately, was hoping, while she plied her industrious and skilful needle, that at some time in the immediate future—probably that very afternoon—that conceited, stuck-up little green-eyed thing in the first-floor flat would receive an extremely unpleasant surprise. Her heavy face brightened to a faint animation. What a bit of luck that that little beast of a dog had been alone.

In the ground-floor flat, the elderly Hopgood, who in bygone days had received many a half-crown from Mrs Whalley’s father, and who regarded her, with a rather melancholy tenderness, as one of his last links with a past of incredible brightness now vanished for ever, was thinking about her rubbish-bin.

The rubbish bins of the other tenants were kept in the front garden, imperfectly concealed in a recess under the bottom flight of the outside staircase. Mr and Mrs Whalley, however, preferred to keep theirs on their landing of the staircase, outside their hall-door. Lately the Corporation’s scavengers had been kicking up a fuss about having to go up to the landing for the bin, and, upon their last call, had refused point-blank to do so. To Hopgood’s indignation, they had been impertinent to Mrs Whalley when she had remonstrated with them. As he smoked his pipe and waited for his tea-kettle to boil, Hopgood decided that he would himself carry down Mrs Whalley’s bin to the front garden each Monday and Thursday afternoon and carry it up again when it had been emptied into the Corporation cart.

Pleased with this solution of Mrs Whalley’s little difficulty, Hopgood proceeded to the brewing of his tea. He had been really shocked by the way in which the Corporation men—two great, hulking, grinning young louts—had spoken to her and looked at her. Especially the way they had looked at her—looked at her legs—looked her all over, grinning—as if she was one of the young sluts they messed about with. People of that kind, Hopgood had noticed—messengers, vanmen, bus-conductors—in fact, the lower classes generally—had suddenly become markedly uncivil and aggressive lately. He had thought a good deal about this, and, for some reason which he could not quite explain, he was somehow uneasy about it. Things had got queer, somehow. All those things in the newspapers now—wars and disasters and revolutions and suicides and murders. Everything had got queer, somehow, this year. It was pleasant to see a lady like Mrs Whalley tripping in and out with her little spaniel—a bit of the old times still left—something you could look up to and feel sure about … Looking at her legs … The swine.

Below him, in the basement flat, the lonely Mr Ridgeway was also meditating a small service to her. In his dark, dampish-smelling sitting-room—only the upper halves of its windows rose above the level of the front-garden—he was re-reading once more a letter which he had written three days before.

‘DEAR MRS WHALLEY,—I am returning, with gratitude, the books which you so kindly lent me some time ago. I have read them with much interest. Please accept my apologies for having kept them so long. But I am the slowest of readers.

‘Since our last meeting I have heard from a medical friend who is specially interested in your husband’s trouble. I enclose some cuttings which he has sent me with reference to a new extract from which excellent results have been obtained, and hope your husband will be persuaded to give the accompanying small supply of it a trial.

‘Yrs sincerely,

‘AMBROSE RIDGEWAY.’

He laid the letter down and sat back in his chair, a stoutish, untidy man of fifty-five or so, with a rather gross and bloated face which had once been handsome and was still redeemed by a pair of very fine eyes. Presently, he told himself, he would shave and put on a clean collar and shirt and his good suit and go up the steep steps to deliver his note and his two small parcels. Perhaps it would be she who would open the door—more probably her husband. Though, in the afternoon he tried to work—poor devil.

Presently, though. There was plenty of time, and not often something to look forward to.

His eyes rested upon the medical journals from which he had clipped the cuttings several days before. They still lay open upon a small table, grey with the dust of Downview Road. Misgiving grew again in him. Was it wise to associate himself in any way with medical matters?

After some meditation he tore up his letter, dropped one of the parcels into a drawer, and then stretched himself on a sofa, covering his face with a dingy handkerchief. He would write just a note of thanks, returning the books.

But presently. There was plenty of time. It was raining. Tomorrow would do just as well.

Harvey Knayle also was thinking just then of Mrs Whalley, in whom, as we shall see, he took an interest of a somewhat complicated kind. He was standing in Edwarde-Lewin’s study, whither they had retired to discuss, before tea, a projected fortnight’s fishing in Ireland, and, while his host fumbled in a drawer, he was telling about the Prossips’ gramophone.

‘What’s the law of the thing, Lewin?’ he asked, jingling his loose silver. ‘How many times may the chap in the flat over you play the same tune on his gramophone continuously before you can take legal action to make him stop?’

Edwarde-Lewin ceased for a moment to be a genial sportsman and became a discouraging solicitor.

‘You can’t stop him,’ he replied curtly. ‘He may play it all day and all night if he wants to. You have no legal redress. Unless you can prove malice.’

‘Now, how does one prove malice?’ enquired Mr Knayle.

‘Just so,’ snapped Edwarde-Lewin, and immediately resumed his geniality and his fumbling. ‘Now, where the deuce did I put that confounded letter—’ He remembered that he had perused, personally, Mr Knayle’s agreement at the time of his last moving. ‘But the lease of that flat of yours is nearly up, as well as I remember. Noisy place, Downview Road, now. You won’t stay on there, will you?’

To his own surprise, Mr Knayle suddenly abandoned a decision at which, upon prolonged and anxious consideration, he had all but arrived that afternoon.

‘Oh yes, I shall stay on,’ he said quite definitely. ‘I’m used to the noise now. Noises don’t worry me. Besides, I like the look-out over the Downs. No houses opposite. Oh yes. I shall stay on.’

Edwarde-Lewin found the missing letter and proceeded to read it aloud. Mr Knayle, however, although, as has been said, he was an ardent fisherman, looked out at the already soaked tennis-courts and went on thinking about the real reason which had decided him to keep on his flat in Downview Road.

5

While he shut the bathroom door, Whalley looked at his wrist-watch. Five past four. He had been sure that it was not yet a quarter to. The kitchen floor always took an hour and a half to do—two hours if one washed the skirtings and the other paintwork. He couldn’t hope now to finish before half-past five. This alteration of a quarter of an hour in his plans threw him into a flurry. He changed feverishly into the old trousers and dilapidated pullover in which he did his housework and, hurrying to the kitchen, began to move its movable furniture out into the passage.

Once a week for the past eighteen months he had performed this detested task—the most detested and most troublesome of the drudgery to which circumstances had doomed him. Like that of all others, its procedure was now stereotyped—a sequence of merely automatic gestures requiring no least direction from will or judgment or even consciousness. He began it, as always, by carrying out the two chairs into the passage and, as he did so, his impatience, already fatigued, rushed on ahead in desperation, foreseeing every dull, familiar detail of the labour before him, every smallest necessary movement, every trifling difficulty, every unavoidabe compromise with the ideal of a perfect kitchen floor perfectly washed.

After the chairs, the small table by the right hand window to be carried into the passage—far enough along it to leave room for the other things to follow it. Then the three baskets in which Elsa kept vegetables and fruit. Then the little cake-larder, which stood on the floor because the walls wouldn’t hold nails securely. Then the set of shelves on which the saucepans and pan stood and hung. Some of them would fall and kick up a clatter. Then the small table by the sink. Then the basins stacked under it. Then the kitchen bin. (That would have to be washed out with hot water and disinfected when it had been emptied into the big bin outside the hall-door). Then the bread-bin and the flour-bin and the three empty biscuit tins under the big table. Then the big table itself (it had to be turned side up to get it through the door and even then its legs had to be screwed through one by one). Then all the small oddments kept on the floor along the walls, because there was no other place to keep them—unused things, most of them—obsolete trays and grids belonging to the electric-cooker—old boxes and jam pots and tins—kept because they might be useful some time.

The sweeping, then—the same old places that took so much time to get into with the sweeping-brush, the same old snags that caught its loose head, the same old stoopings and twistings to get the same old dust and dirt out. Then the dustpan to gather up the dirt. The dustpan to be emptied into the bin. Then the bucket to be rooted out of the cupboard under the sink (it always jammed against the sink’s waste-pipe) and taken to the bathroom and filled with hot water from the geyser. The scrubbing brush and floor-cloths and soap to be collected from the bathroom cupboard. The bucket to be carried back along the blocked passage to the kitchen, very slowly, lest the water should splash over—

At this point, while he hurried from kitchen to passage and back again, his eyes, at each return, fixing themselves for a moment frowningly on the dresser-clock, he began again the old, never-decided debate as to the wisdom of washing the linoleum covering the floor—an expensive, inlaid linoleum which had been a special pride of Elsa’s in the days of the kitchen’s first freshness. Someone had told Elsa that linoleum ought to be washed—with a dash of paraffin in the water. Someone else had told her that it ought to be washed with Lux. Someone else had told her that it ought never to be washed on any account, but done with polish. He had tried various polishes. Certainly the linoleum had looked better when polished—it always looked grey and dull after washing. But the polishes all left a greasy surface in which dirt lodged. Anyhow, the last tin of polish was practically finished now. The linoleum would have to be washed today—

A vibration—and then a new noise rose in pitch and, piercing a way through the uproar of the Prossips’ offensive, became the strident clamour of a plane, flying very low, over the house. It came into view—was illuminated by a blinding flash of lightning—went on its serene, unswerving way, undismayed by the crashing peal that followed. Whalley’s eyes watched it until it disappeared over the tree-tops. He smiled bitterly at a vision of its pilot—young, fearless, efficient—a man doing a man’s job while he washed the kitchen floor.

Twenty past four—and practically nothing done yet. He fell upon the miniature dresser upon which the pans and saucepans were arranged and lifted it towards the door. A pan and two saucepans fell noisily to the floor. As he deposited his burden in the passage, the bombardment in the Prossips’ coal-cellar ceased sharply and the whistle fell to silence. Footsteps had hurried from the top-flat’s sitting-room; the gramophone stopped. While Whalley stood, vaguely debating the reason of this sudden cessation of hostilities, the bell of his own hall-door rang.

After a brief hesitation—for he disliked being seen in his working-clothes by anyone but his wife—he descended to the door and, opening it, saw his landlord, Mr Penfold, standing in the rain beneath a streaming umbrella. The sudden lull upstairs was explained. By unfortunate chance, the enemy had observed Mr Penfold’s approach—no doubt had seen him—from their sitting-room windows, alight from a bus opposite the front garden’s gate.

There had been trouble with Penfold—a truculent individual, by avocation a commercial traveller, who had inherited Nos. 47 and 48 Downview Road from an aunt deceased some few years before. The Whalleys had moved into the flat rather hurriedly, accepting a merely verbal assurance that it would be ‘done up’ in the following spring. But when the following spring arrived, Penfold had refused to remember having given any assurance of any kind as to doing anything. There had been interviews and, subsequently, correspondence, in the course of which he had passed from evasion to incivility and from incivility to impertinence. Finally Whalley had had the kitchen, the dining-room, and the bedroom repainted and repapered at his own cost, and had consoled himself by the fact that he had never since seen his landlord’s face.

It was a large, heavy-jowled face, out of which a pair of cunning little eyes looked at him now with unconcealed hostility. Without moving any part of it visibly, Penfold said at once:

‘Afternoon. What’s this I hear about that dog of yours?’

‘I’ve no idea,’ replied Whalley. ‘Do come in, won’t you?’

Ignoring the invitation to enter, Penfold surveyed the old trousers and pull-over at his leisure and sniffed. Then, taking a fresh stand with his square-toed boots, he transferred his gaze to the cover of the rubbish-bin.

‘Oh! You’ve no idea. I see. Well, I’ll give you an idea, then. I have received complaints from the other tenants of these flats that your dog has been molesting them—attacking them and causing them annoyance and nuisance.’

‘Who has complained, Mr Penfold?’

‘Never you mind.’ Penfold’s hand swept the question aside. ‘That is what I am informed. And I’m satisfied that I’m correctly informed. So we won’t argue about the point.’

‘I haven’t the slightest intention of arguing about it,’ Whalley retorted sharply. ‘Or about anything else. If you have any complaint to make, put it in writing and I’ll pass it on to my solicitors—if I think it worth while doing so.’

Highly amused, Penfold threw back his head and guffawed. He turned then and feigned to depart, but stopped and delivered his ultimatum over a shoulder.

‘Now, listen here, Mister Whalley—as you’re talking about solicitors. According to your agreement, you are permitted to keep a dog in this flat only on the condition that it causes no annoyance to any of the other tenants. Your dog has caused such annoyance. It attacked one of the other tenants savagely. Jumped up on her and tried to bite her hands. It alarmed her so that she was obliged to remain in bed for two days with a heart attack. I give you notice now to get rid of it immediately. If you fail to do so before this day week, I will instruct my solicitors to take action to compel you to keep to the terms of your agreement.’

‘You can start taking them now, damn you,’ snapped Whalley.

Again Mr Penfold surveyed the old trousers and pullover exhaustively as if expecting to extract from them an explanation of his tenant’s childish ill-temper. He sniffed again, then, and turning away irrevocably went down the steps with threatening slowness and heaviness. As Whalley slammed the hall-door, a voice, humming with exaggerated blitheness above his head, informed him that the interview had had an audience. He made his way slowly back along the crowded passage towards the kitchen, revolving wrathfully this latest manœuvre of the Prossips.

The crude but effective ingenuity of it exasperated him—all the more because its malice was feminine and, he knew, had aimed itself more especially at Elsa. For Bogey-Bogey, though he tolerated a master, had but one god and was entirely the property of his mistress—her inseparable companion and, as the Prossips could not have failed to learn from the daily observation of the six months for which they had occupied the top flat, the light of her eyes. They had struck at her most vulnerable point—at his, because the blow was aimed at her.

Savage attack.

The facts were that one day about a week before, Bogey-Bogey, the gentlest and best-tempered of creatures, had escaped into the front garden and, encountering Mrs Prossip and her daughter there, had, after his inveterate habit of doing the wrong thing, rushed at her joyously and jumped up on her skirts. The Prossip girl had jabbed him savagely with her sunshade and he had fled back whimpering to Elsa, who had witnessed the incident from the kitchen and had hurried out to his rescue. She had met the female Prossips on the steps, but they had made no complaint at that time. It had obviously taken them some days to discover that Bogey-Bogey had placed a new weapon in their hands and to induce that brute Penfold to wield it for them. Not that he was likely to have required much inducement—swine. God! What a face—what eyes.

Victoriously, refreshed by its rest, the gramophone resumed its blaring. He walked slowly back along the passage until he stood almost directly beneath the sound, and stood looking up. Its position could be calculated almost exactly.

Out of the question, of course, to think of parting with Bogey-Bogey … unthinkable. Probably the threat was merely spiteful bluff on Penfold’s part. Though he was quite capable of trying to carry it out. Of course, he couldn’t carry it out. Still … suppose they had to turn out of the flat …

Yes. One could calculate the position of the gramophone almost exactly. The landings of the two flats, of course, corresponded precisely in size and position. The Prossips would have placed the gramophone where it could be most conveniently reached by anyone who had to go to it repeatedly, either from the kitchen or their sitting-room, close to the balusters, two steps down the little stairs from the passage to the hall door. For, of course, they had to lean over the balusters to get at it and would do so where their rail, following the fall of the stairs, first became sufficiently low to place the gramophone within comfortable reach.

He decided upon a knot in the under-surface of the Prossips’ match-boarding. Just there. A line through that knot—say, from the centre of his own landing—ought to pass through the near side of the gramophone. If a hand was restarting the needle, and if a face was bent over it as it did so, the line would just about catch them both—some part of both of them. It would have to be a little oblique, of course—yes, starting from the centre of his own landing—that would be just about right …

Wasn’t there something in the agreement about the landlord being able to take steps to recover possession of the premises if the tenant violated any of the terms of the agreement?

One would be able to time it exactly, too. The footsteps would come hurrying—stop—count one—and then the face would be bent over the record—the bullet would rush up at it out of the record, smash into it, stop its sniggering and grinning.

Perfectly simple. The only difficulty was that the bullet might strike the motor of the gramophone and get deflected, or stopped.

He continued to stand, looking up, calculating absorbedly. One couldn’t possibly do it, of course. The risk would be too great. No one would believe for a moment, knowing of the quarrel with the Prossips, that it had been an accident, though there was, if you came to think of it clearly, no reason why he shouldn’t just happen to examine his old service revolver one day out in the passage of his flat and why it shouldn’t just happen to go off. That sort of thing was always happening …

And, if one could do it safely, of course, it would be so perfectly simple.

Once more the gramophone’s blaring ceased. Once more footsteps hurried to it—stopped. Once more the accursed torment began. Five o’clock? What the devil had he been thinking about—standing there like a fool? Too late to do the floor now.

He began to carry back the things which he had carried out of the kitchen, replacing them exactly in their former positions. Tomorrow or next day they would all have to be carried out again.

6

It is clear that Mr Knayle was right and that Whalley was taking this silly, childish feud with the Prossips altogether too seriously. The curious thing is that Whalley had been living on a sense of humour for the greater part of twenty years.

CHAPTER II (#uad5ee2e2-bcb3-5dfa-ad34-0f5d08a0ca51)

1

IN August, 1918, as he lay in the white, stunning peace of the hospital-ship which was carrying him to England, a matter which for four years had appeared to him of no practical importance whatever began to invest itself with a faint interest. Suppose that rumour at last spoke the truth and that the incredible was to be believed. Suppose that the Boche was finished and that peace was coming some time within the next six months, what was Simon Whalley (Capt., D.S.O.) going to do for the rest of a life which, after all, might continue for a considerable time.

The shrapnel wounds in his head and shoulder were not very serious, he had been told; but it would probably take a year at least to make the shoulder a serviceable one again. It was at all events a possibility that, so far as he was concerned, the War had finished. If it had, what was going to happen him next?