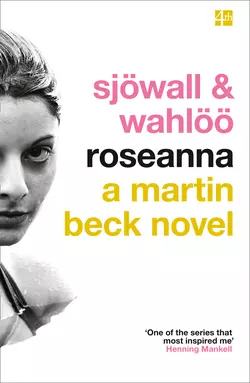

Roseanna

Henning Mankell и Maj Sjowall

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Roseanna is the first book in the hugely acclaimed Martin Beck series: the novels that shaped the future of Scandinavian crime fiction and influenced writers from Stieg Larrson to Jo Nesbo, Henning Mankell to Lars Kepplar.On a July afternoon, the body of a young woman is dredged from a lake in southern Sweden. Raped and murdered, she is naked, unmarked and carries no sign of her identity. As Detective Inspector Martin Beck slowly begins to make the connections that will bring her identity to light, he uncovers a series of crimes further reaching than he ever would have imagined and a killer far more dangerous. How much will Beck be prepared to risk to catch him?