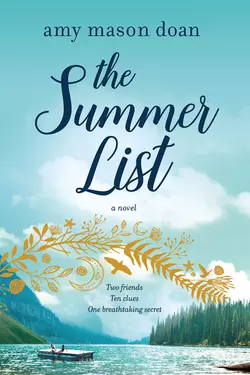

The Summer List

Amy Mason Doan

‘An evocative tale of family, first love, and the unique and lasting gift of a friendship formed in girlhood.’ Meg Donohue, USA Today bestselling authorA breathtaking secret that will change everything…As young girls, Laura and Casey were inseparable in their small California lakeside town, playing scavenger hunts under the starry skies all summer long. Until one night, when a shocking betrayal shatters their friendship seemingly forever…But after seventeen years away, the past is impossible to escape and Laura returns home. Tthis time, a bittersweet trail of clues leads brings back her most cherished memories with Casey. Yet just as the game brings Laura and Casey back together, the clues unravel a stunning secret that threatens to tear them apart…Readers love Amy Mason Doan:“Beautifully descriptive, THE SUMMER LIST by Amy Mason Doan will transport you to a setting of such beauty that it will take your breath away.”“The writing is beautiful, the pacing is great and the story flows seamlessly”“Can't wait to have my book group read so can discuss it more deeply and to give it as gift to family and friends”“I really loved it and look forward to more books by this writer.”“A beautifully crafted novel.”

Laura and Casey were once inseperable...

Coming of age in California, Laura felt connected to her best friend in every way: as they floated on their backs in the sunlit lake, as they dreamed about the future under starry skies, and as they teamed up for the wild scavenger hunts in their small lakeside town. Until one summer night, when a shocking betrayal sent Laura running through the pines, down the dock, and into a new life, leaving Casey and a first love in her wake.

But the past is impossible to escape, and now, after seventeen years away, Laura is pulled home and into a reunion with Casey she can’t resist—one last scavenger hunt. With a twist: this time, the list of clues leads to the settings of their most cherished summer memories. From glistening Jade Cove to the vintage skating rink, each step they take becomes a bittersweet reminder of the friendship they once shared. But just as the game brings Laura and Casey back together, the clues unravel a stunning secret that threatens to tear them apart...

Mesmerizing and unforgettable, Amy Mason Doan’s The Summer List is about losing and recapturing the person who understands you best—and the unbreakable bonds of girlhood.

The Summer List

Amy Mason Doan

Copyright (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Amy Mason Doan 2018

Amy Mason Doan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9781474083713

For Mike and Miranda

Contents

Cover (#u1d1e7074-3dac-5fb3-805d-b5e7a430a9a8)

Back Cover Text (#uc6473525-3396-58ce-9a76-5f5bcf9c422f)

Title Page (#u890d787c-9c7c-5ead-b7b1-639bb4b4869b)

Copyright (#u577ca235-be01-5e73-888f-161e74c2c0e9)

Dedication (#u0181fbdd-3e8f-5ccd-9457-00c848e8e555)

Preface (#ubcf299a1-e524-5445-9f1f-0ee5e3bc8312)

1 Mermaid in the Mailbox (#u84c2682b-c481-5429-b7be-2b187d304445)

2 Ariel and Pocahontas (#u4c09df4f-775d-5ea1-850a-12cd8ce8fcb3)

3 Alexandra the Great (#ud59c2a71-1083-5c02-84b6-c46b64f8189f)

4 The Machine (#ue48f4381-29d5-51a7-a2c6-d804b8fd81b2)

5 Bartles & Jaymes (#uf6f6ecfe-b408-51fb-943d-45be1427705f)

6 Messy (#uf57cc48d-0b05-5c20-b636-03fa0ceff53a)

7 The Boy Behind the Counter (#u12c51a0b-a160-533b-96ab-ea0f76a0219d)

8 (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Raptor Rock (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Critical and Confusing (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Yes, No, Wow (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Things That Don’t Belong (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Velocity (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Stepping Stones (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Dreaming Shepherd Books (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Vanity (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Sorry (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 More than Fun (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Honor System (#litres_trial_promo)

22 June Names That Tune (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Band-Aids (#litres_trial_promo)

24 Liquid Hiding Place (#litres_trial_promo)

25 Gamemaster (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 Women’s Retreat (#litres_trial_promo)

28 Whistle While You Work (#litres_trial_promo)

29 The Moon and Stars (#litres_trial_promo)

30 Doctor Mona’s Hot Springs and Holistic Spa (#litres_trial_promo)

31 (#litres_trial_promo)

32 Another Tiny Surprise (#litres_trial_promo)

33 Biggest Little City in the World (#litres_trial_promo)

34 Rainbow of Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

35 (#litres_trial_promo)

36 Sacred Institutions (#litres_trial_promo)

37 Counting Down (#litres_trial_promo)

38 Lost and Found (#litres_trial_promo)

39 Again (#litres_trial_promo)

40 (#litres_trial_promo)

41 A Pirate (#litres_trial_promo)

42 (#litres_trial_promo)

43 Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

44 Skipping Stones (#litres_trial_promo)

45 Extreme (#litres_trial_promo)

46 (#litres_trial_promo)

47 Fog (#litres_trial_promo)

48 (#litres_trial_promo)

49 Weathr-All (#litres_trial_promo)

50 (#litres_trial_promo)

51 Treasure (#litres_trial_promo)

52 The Visitor (#litres_trial_promo)

53 The Prize (#litres_trial_promo)

epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Reader’s Guide (#litres_trial_promo)

Discussion Questions (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

California

July

27th day of camp

The others were mad at her again.

They clustered behind her on the sand, watching as she stepped onto the wet ledge of rocks.

“What is she doing?”

“What are you doing?”

Ignoring them, she picked her way across tide pools, careful not to hurt the creatures underfoot—quivering purple anemones that retracted under her shadow, barnacles like blisters of stone.

All she wanted was a few minutes away from them. A few minutes alone to breathe in the cold wind off the ocean before the van delivered them back to the airless cabins, the dark chapel.

There were only ten minutes left in the game, and it would take her almost that long to make her way back across the slippery outcropping. If they didn’t return in time it’d be another mark against her.

She spotted something tangled in kelp, lodged between two flat rocks near the drop-off. So close to the surf. As if it had been carried across the ocean and snugged there, at the jagged edge of the world, just for her.

Stepping closer, she crouched, then flattened herself onto her belly. Her shirt and jeans drenched, her elbow scraped, she reached out but got only a rubbery handful of kelp.

She shut her eyes. If she looked down at the sea she would fall in like the doomed man on the keep-off sign behind her, a stick figure tumbling into scalloped waves.

Salt spray stinging her face, she fumbled through the squelching mass of kelp. Until her fingers found what they wanted and it gave, escaping its wet nest with a gentle sucking sound.

She knelt on the wet rocks as she examined her prize, brushing away green muck. The driftwood was longer than her hand, curved into a C. One end was pointier than the other, and in the center the wood splintered and cracked. But imperfect as it was, the resemblance was unmistakable, miraculous: a crescent moon.

Cur-di-lune, he’d said. I grew up in a town called Curdilune.

A strange, pretty name.

He’d drawn it for her in the dusty ground behind the craft cabin that morning. His calloused finger had sketched rectangles for the buildings. Houses and a church, shops and a park, nestled together against the inner curve of a crescent-shaped lake.

Curdilune. Cur is heart in French, he’d explained. Lune is moon. So it means Heart of the Moon. Then, with a light touch on her wrist—You miss home, too?

The others had walked by then, before she could answer, and he’d erased his little map, swirling his palm over the shapes in the dirt so quickly she knew it was their secret.

If she ran back to her team now, her find might help them win—a piece of driftwood was Item 7 on the list stuffed into her back pocket.

She glanced over at them and slid the wet treasure down her pocket, untucking her shirt to hide it. She’d give it to him instead.

It was a thank-you, an offering, an invitation. A cry for help after the long, bewildering summer.

1 (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

Mermaid in the Mailbox (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

June 2016

The invitation came on a Saturday.

I was taking Jett for a walk, and she was frantic with anticipation, nails skittering on the lobby’s tile floor, black fur spiking up so she looked more like a little dragon than a Lab.

“If you calm down I can do this faster, lady,” I said as I high-stepped to free myself from the leash she’d wrapped around my ankles. “Off.”

She retreated, settling under the bank of mailboxes. But right when I got my letters out, she sprang up and butted my wrist with her head. Perfect aim, perfect timing.

“Leave it, Joan Jett. Devious girl.” I tried to maintain the stern voice we learned in Practical Skills Training but couldn’t help laughing as I collected my mail from the floor. A typical assortment. White, business-sized bills. A Sushi Express menu. A slender donation form for Goodwill.

Then—not typical—a hot-pink envelope.

It had fallen facedown, revealing a sticker centered over the triangular flap: a mermaid. In pearls and sunglasses. Holding a sign saying You’re Invited!

I assumed it was for the tween girl who lived in #1. I was #7, so there were sometimes mix-ups. I was halfway down the hall to her family’s unit when I flipped the envelope over, preparing to slide it under their door.

It was for me.

Ms. Laura Christie, 7 Pacific View, San Francisco, CA 94115.

No return address.

But I knew who it was from.

I knew because of the mermaid sticker, which now made sense, and from the surge of something close to happiness in my chest.

I ripped the envelope open and pulled out a photo of two grinning 1950s girls in pajamas. Over their rollered heads, in black ballpoint, she had printed Coeur-de-Lune. My hometown.

Then dates—Thurs. June 23–Sun. June 26. Less than three weeks away.

Below that it said:

Scavenger hunt!

Crank calls!

Manicures!

Trio of cookie dough!

But seriously, please come. We’re supposed to be older and wiser. (35—how did it happen?) I promise it will be ok.

No RSVP necessary.

Casey

Casey Katherine Shepherd. I hadn’t seen her since we were eighteen.

When I ran into people from Coeur-de-Lune they inevitably asked me about Casey, and I always said, “We drifted.” They would nod, as if this was the most natural thing in the world. People drifted.

In my case it’d be more accurate to say I’d swum away. As fast as I could, trying my hardest not to look back.

I slid the card into its torn pink envelope and turned it over again, my thumb smoothing the top edge of the sticker, where it had curled up slightly.

I promise it will be ok, she’d written.

(35—how did it happen?)

I held the invitation over the recycling basket, pausing a second before letting it flutter into the mess of junk mail. I waited for the soft rustle it made on landing before I let Jett tug me to the door.

* * *

It was cool and sunny, a rare reprieve from San Francisco’s usual June Gloom.

Jett headed right on the sidewalk out of habit. Saturdays we always strolled to Lafayette Park, hitting up her favorite leisurely sniff stops on the way. But today I pulled gently on the leash, and she turned, surprised, as I led her to a crosswalk in the opposite direction, charging uphill toward Lyon Street. I needed the steep climb, something to clear my head.

Why now, Casey? After seventeen years?

My childhood home in Coeur-de-Lune was now a vacation rental, managed by efficient strangers. I’d never gone back. But my mother kept a buzzing gossip line into her church women from town, and gave me sporadic updates on Casey’s life.

She always brought Casey up when I was lulled into complacency. When we’d had a surprisingly peaceful afternoon together. When we were outside on her balcony, or sharing a piece of her peach pie like other mothers and daughters did.

Only then would she jab, a master fencer going for the unprotected sliver of my heart.

The first update, when I was twenty—Casey Shepherd dropped out of college. Back living with that mother in town.

That must be nice for them, I’d said, not meeting her eyes.

A few years later—Casey Shepherd bought the bookstore. Moronic. Might as well have thrown her money in the lake.

I was in her kitchen that morning, unloading groceries into her retirement-sized pantry. Macaroni, crackers, mushroom soup. Hands moving smoothly from bag to shelf, making sure the labels faced out.

That’ll be interesting, I’d said. My eyes were trained on my mother’s well-organized shelves, but they saw Casey’s bookcase, crammed with her beloved trashy paperbacks. Fat, dog-eared copies of Lace and Queenie and Princess Daisy.

After the bookstore news I didn’t hear anything about Casey for a long time. I had men in my life, a few friends I met for glasses of wine. I was fine. Settled. Lucky. And able to keep my face blank when my mother said, three years ago:

Casey Shepherd has a child. A girl. Adopted, foster child, something. Hmph. Surprised anyone would let a child into that house. That mother’s still there, you know.

I was thirty-two then, and after nearly a decade of blessed silence on the topic of the Shepherds, I could meet my mother’s eyes and say evenly, Casey always liked kids.

It was the first time I’d said her name out loud since high school.

* * *

I began to run, an easy jog.

Was it because of our ages? Was thirty-five the number at which a goofy card could fix everything?

(35—How did it happen?), she’d written, in that familiar, nearly illegible penmanship. Her cursive had always been sloppy, with big capitals.

Casey’s mother, Alex, had gotten into handwriting analysis one summer. According to Alex’s book, Casey was energetic and loyal, I was creative and romantic, and Alex was an aesthete with a passionate nature. If there had been something in how we looped our Ls or curved our Cs that hinted at what was to come, at less flattering traits, we’d overlooked it.

Alex would be there, if I went. Spinning around as if everything was the same, raving about her latest obsession. Celtic runes or cooking with grandfather grains. Whatever she happened to be into that week.

I sped up, though the grade was now more than forty-five degrees. One of those legendary San Francisco hills, perilous to skateboarders and parallel-parkers. Jett’s leash was slack, not its usual taut water-skiing line dragging me forward. But she pushed on loyally at my side, the plastic bags tied to her leash flapping and whistling.

Why, Casey?

Wind-sprint pace now, sloppier with each stride.

Maybe she was bored and wanted to see what I’d do if she dared me to visit.

At the top of the hill I bent over, hands on my knees. Jett panted, her black coat shiny as obsidian.

Below, the wide grid of streets and houses swept down toward the Marina, to the bright blue bay flecked with white sails, all the way to the hills of Tiburon rising from the opposite shore. To my left, I could just make out the graceful, ruddy lines of the Golden Gate holding it all in, because without it such aching beauty would escape to sea.

The dark little crescent lake where I’d grown up was nothing compared to this.

The Bay could hold thousands of Coeur-de-Lunes.

I headed slowly back downhill toward my building. My back was soaked, my chest tight. I was lucky I hadn’t rolled an ankle.

And I hadn’t managed to cardio the invite from my head. Casey’s words were still in there, burrowing deeper. I could hear her voice now. The voice of an eighteen-year-old girl, plaintive beneath her irony.

But seriously, please come.

* * *

I was sure the mermaid would be safely buried by the time we got back.

But when I passed the mailboxes, there she was, staring up at me. Her tail was covered by a Restoration Hardware catalog, the top edge perfectly horizontal across her waistline. Or finline. Whatever it was called, it looked as if someone had tucked her in for the night, careful to leave her face uncovered so she could breathe.

I reached down and, in one quick gesture, plucked the pink envelope from the basket.

I couldn’t go.

But I also couldn’t leave her like that, all alone.

Coeur-de-Lune

Thursday, June 23

That was nineteen days ago. And now I was in Casey’s driveway, trapped. Too nervous to get out of my car, too embarrassed to leave.

I blamed the mermaid.

Once she’d escaped the recycling bin, the pushy little thing had managed to secure a beachhead on my fridge.

For days, she’d perched there, peering over a black-and-white photo of a young 1970s surf god conquering an impossible wave: one of the magnets I’d designed for Sam, my favorite client and owner of Goofy Foot Surf & Coffee Shackout by Ocean Beach.

As the date grew closer, the mermaid started migrating around my apartment. She kept me company in the bathroom when I flossed in the morning, and as I ate lunch at my small kitchen table. When I couldn’t sleep at night and passed the time brushing the frilled edges of the envelope back and forth under my chin, rereading Casey’s words. Trying to figure out why she’d written them now, after so long.

I still didn’t understand.

The invitation had said No RSVP necessary, and I’d taken her up on that, so she didn’t know I was coming. Until today, I hadn’t been sure myself.

But here I was.

I tunneled my hands into the opposite sleeves of my coat, hugging myself. I’d rolled down my window a few inches, and chilly mountain air was starting to seep in. Jett was in her sheepskin bed in the back, curled into a black ball like a giant roly-poly. I was stalling. Rereading the invite as if I hadn’t memorized it weeks before.

I leaned over the steering wheel and stared up at the house as if it could provide answers. From the front it resembled one of those skinny birdhouses kids made in camp out of hollow tree branches standing on end: a wooden rectangle with a crude, A-shaped cap.

But from the water it looked more like a boat, with rows of small, high windows—so much like portholes—and a long, skinny dock—pirate’s gangplank—to complete the effect. When the place started falling apart in the ’70s, some grumbly neighbor called it The Shipwreck, and the name had stuck.

It was a love-it-or-hate-it house, and the Shepherd women had loved it.

So had I. I’d once felt easier here, more myself, than in my own home. The Shipwreck hadn’t changed, but today it offered me no welcome.

There was a silver Camry ahead of me in the driveway, so someone was probably home. They could be watching, counting how many minutes I sat inside my car. Trying to gather my courage, and failing. I didn’t feel any more courageous than I had when the invitation first arrived.

“Wish me luck,” I whispered toward Jett’s snores as I got out. I shut the door a little harder than necessary, hoping the plunk would draw Casey and Alex outside. Then they’d have to say something to hurdle us over the awkwardness. “You made it!” Or “Come in, it’s getting cold!”

But the front door didn’t budge.

I walked slowly toward the house, past the Camry. The section of lake I could see beyond the house was at its most stunning, framed in pines, streaked with red and pink from the sunset. It was so ridiculously beautiful it seemed almost a rebuke, a point made and underlined twice. This is how a sunset is done.

As I got closer I noticed something about the colors on the water; most of the red shapes were dancing, but one was still. And I realized why Casey hadn’t come outside when I pulled up.

Of course. She was already outside.

I walked past the right side of the house, where the ground became a thick blanket of pine needles. I’d forgotten that spongy feeling, the way it made you bend your knees a little more than you did in the city, the tiny satisfying bounce of each step. There were places where the needles were so deep I had to brush my hand along the rough wood shingles for balance. I hoped the neighbors wouldn’t see me and decide I was a prowler. I was even wearing all black. Tailored black pants and my black cowl-neck cashmere coat, but still. I could be a fashion-conscious burglar. It would be something to talk about, at least, showing up in handcuffs.

Casey sat cross-legged on the dock, her crown of sunlit red hair just visible above the red blanket on her shoulders.

It was the same scratchy wool plaid throw we’d used for picnics. The same one we’d sprawled on in our first bikinis as teenagers. In high school I’d hidden mine in my winter boots, one forbidden scrap of nylon stuffed down each toe.

A duck plunged into the water nearby, its flapping energy abruptly turning to calm, and she said something to it that I couldn’t make out. Maybe we could do this all night. She’d watch ducks, I’d watch her, and once an hour I’d take a few steps closer.

I walked down the sloping, sandy path in the grass and stepped onto the wooden dock. It was still long and narrow, the boards as old and misaligned as ever. Cattywampus, Alex used to call them. Casey’s mom was young—sometimes she seemed even younger than us. But her speech was full of old-fashioned expressions like that. “Cattywampus” and “bless my soul” and “dang it all.”

The feeling of the uneven boards beneath my feet was so familiar I froze again.

The last time I’d been here I’d been running. Pounding the boards, racing away from the feet pounding behind me.

It was not too late to slip away. Take big, quiet steps backward. I could retreat along the side of the house the way I’d come. Return to the city and let the Shepherds sink back into memory, along with everything else in this town.

But a subtle vibration had already traveled down the wooden planks, and Casey turned her head to the side, revealing a profile that was still strong, a chin that still jutted out in her defiant way. “Is it you?”

“Yes, Case.”

I walked slowly to the end of the dock until I stood over her left shoulder, so close I could see the messy part in her hair. It was a darker red now.

The greetings I’d rehearsed, the lines and alternate lines and backup-alternate lines, had abandoned me. They’d sailed away, carried off by the breeze when I wasn’t paying attention.

But Casey spoke first, her eyes on the water. “You’ve been standing back there forever. I thought you were going to leave.”

“I almost did.”

She tilted her head up to look at me. Scanning, evaluating, and, finally, delivering her report—“You’re still you.”

Her face was a little thinner, her skin less freckled. There was something behind her eyes, a weariness or skepticism, that hadn’t been there when we were girls.

I forced a smile. “And you’re still you.”

I got, in return, no smile. And silence.

Casey made no move to get up, so I fumbled on. “And the house is still...”

“Weird,” she finished.

“I was going to say something like charming.”

“Charming? Laura doesn’t say charming. Tell me Laura has not grown up into someone who says charming.”

She wasn’t going to make this easy. I’d thought, from the cheerful humility of her invitation, that she’d at least try. When I didn’t answer, Casey swiveled her body to look back at the house, as if to evaluate it through fresh eyes the way she’d examined me.

“We haven’t done much. That tiny addition on the east side. And I managed to put in a full bath upstairs finally. It’s yours this weekend, along with my old bedroom.”

“I was going to say. I had to bring my dog. I thought it’d be crowded with all of us, Alex and your little girl and my dog. She’s kind of big, and she’s sweet with kids, but she could knock a little one down... I don’t know how old your girl is but...”

Casey looked up at me but let me stumble on.

“Anyway there wasn’t anybody renting our old place this weekend, so I’ll sleep there...”

The truth was my place had been booked solid all summer, so I’d bumped out this weekend’s renters. Some sweet family that had reserved months ago. Other property owners kicked people out all the time when they wanted to use their houses instead, and my property manager grumbled about it, but I’d never done it before. I’d felt so guilty I’d spent hours finding them another place and paid the $230 difference.

Bullshit, Casey’s eyes said.

She knew the truth: I couldn’t bear staying with her. Tiptoeing around politely in the familiar rooms where we’d once been careless and easy as sisters. But I went on, elaborating on my story—the sure sign of a lie. “Of course I couldn’t put you out...”

“‘Put you out,’” she said. “Grown-up Laura says ‘put you out’?”

I didn’t understand it, the utter disconnect between her warm, silly, lovable letter, the Casey I’d first met, and the person who was sitting here next to me, making everything a hundred times harder than it had to be.

Would the running commentary last all weekend? Laura eats with her fork and knife European-style, now. Grown-up Laura prefers red wine to white. Laura wears cuff bracelets now. Laura changed her perfume to L’eau D’Issey. Every little gesture picked over and mocked.

It hit with awful certainty: I shouldn’t have come.

Would it get better or worse when Alex joined us? I didn’t hate her anymore. Enough time had passed. She couldn’t help how she was.

With Alex to fill the silences, and Casey’s daughter around as a buffer, and me sleeping at my place, I’d just make it through the weekend. Less than sixty hours if I left Sunday morning instead of Sunday night, blaming traffic and work.

“Where’s your mom and your little girl? I’m sorry, I don’t know her name.”

“Elle. Off on a trip together. Tahoe.”

So much for the buffer.

Casey nodded at my old house across the lake. “Now. That one has changed, I hear. Modern everything.”

“Only the kitchen, really,” I said. “The rental company insisted. I’ve just seen pictures.” From across the shining water, I could make out the dark line of the dock, a flash of sunset on a window.

I’d planned to drive there first. Drop off Jett, compose myself, drink a glass of wine (or three, or four) to loosen up for the big reunion. If I had I could have kayaked over to Casey’s instead of driving.

And paddled away again the second I realized how she was going to be.

“You haven’t gone inside?” she said. “Not once?”

I shook my head. “I can do everything online. It’s crazy.”

“I thought maybe you were sneaking back at night. Hiding out in the house, staying off the lake, calling your groceries in. To avoid seeing me.”

“I wouldn’t do that.”

She narrowed her eyes. “You didn’t sell it, though.”

The “why?” was there in her expression, daring me, but I didn’t have an answer. I’d always planned to sell the house. My mother didn’t care either way, and we got offers. Every year, I considered it. But I never went through with it.

I met her stare for a minute before I had to look away. My eyes landed on a spot in the lake about ten yards from the edge of the dock. I didn’t mean to look there. Maybe there was a tiny ripple from a fish, or a point in the sunset’s reflection that was a more burnished gold than the surrounding water.

She followed my gaze. And for the first time, her voice softened. “Strange to think it’s still there. After so long.”

“It’s not. It’s crumbled into a million pieces or floated away.”

Casey shook her head. “No. It’s still there.”

“How do you know?”

“I just do. I feel it in my bones.”

“That sounds like something your mom would say. Used to say.”

She tilted her head, thinking. “God. It does.”

She pulled her knees close to her body and rested her right cheek on them, then looked up at me with a funny little lopsided smile.

There was enough of the Casey I remembered in that smile that I returned it.

I sat next to her, wrapping my coat tighter, my legs dangling off the edge of the dock. It felt strange, to sit like that with shoes and pants on. I should be in my old cargo shorts, dipping my bare feet in the water.

For a minute we watched the quivering red-and-gold shapes on the lake. Then I felt the gentle weight of her hand on my shoulder.

“Don’t mind my flails, grown-up Laura,” she said. “Grown-up Casey is doing her best. She’s missed you.”

The words stuck in my throat, and when they finally came out, they were rough. My eyes on the auburn lake, I reached up to clutch her hand—one quick, fumbling squeeze.

“I’ve missed you, too, Case.”

2 (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

Ariel and Pocahontas (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

June 1995

Summer before freshman year

The fourth day of summer started exactly like the first three.

A second of dread when I woke up, followed by a rush of relief when I remembered it was vacation. Then the quick, glorious tally—no school for eighty-eight days. And finally the smell of vanilla floating down the hall. Yesterday it had been crumb cake, the day before it was muffins, so today was probably French toast. My favorite.

I got dressed fast, changing from my nightgown into my summer uniform: a big T-shirt and cargo shorts.

The last part of my routine was too important to be rushed. I transferred a small, silvery-gray object from under my pillow to the Ziploc I kept on my nightstand, made sure it was sealed to the last millimeter, then slipped it into my lower-right shorts pocket, the only one with a zipper. Where it always went.

Then I had the entire day free to explore the lake. French toast, and no Pauline Knowland or Suzanne Farina asking me what my bra size was up to in honeyed tones, or calling me Sister Christian just within earshot, and the whole day free. Bliss.

It only lasted the length of the hallway.

“You’ll bring that to the new neighbors after breakfast,” my mother said when I entered the kitchen. She was scrambling eggs with a rubber spatula, and she paused to point it at a pound cake on the counter. “Good morning.”

Chore assignment first, greeting second. This about summed up my mother.

She went back to parting the sea of yellow in the pan.

So not only was the vanilla smell for some other family, I had an assignment. I examined the cake’s golden surface. It was perfect, but curiously plain. No nuts, no chocolate chips, no blueberries. Not even drizzled with glaze, and it obviously wouldn’t be. My mother always poured the cloudy liquid on when her cakes were still piping hot.

Next to the naked cake she’d set out a paper plate, Saran Wrap, a length of red ribbon, and one of her monogrammed notecards. A complete new-neighbor greeting kit, ready to go before 7:30 a.m. I read the card silently. Welcome—Christies.

A stingy sort of note, nothing like the warm introduction she’d written when the Daytons moved in down the shore last year. That had included an invitation to church. Surely my mother could have spared a few more words for the new family, a the before our last name. They were right across the narrowest part of the lake from us. If they had binoculars, they could see how much salt we put on our eggs.

It seemed she’d already taken a dislike to the new people, and I set about learning why. “You’re not coming with me to meet them?”

“They have a daughter your age, you need to offer to walk to school together the first day,” she said, like this was written in stone somewhere.

Shoot me now. The last thing I needed was more complications at school. My plan was to lie low in September.

I watched the tip of my mother’s white spatula make figure eights in the skillet. How could eggs be so nasty on their own when they played a clutch role in French toast? I’d take a tiny spoonful and distribute it artfully around my plate so it would look like more.

As if she’d heard my thoughts, my mother mounded a triple lumberjack serving of scrambled eggs onto a plate and handed it to me.

I carried it to the breakfast nook and sat next to my dad, who was hidden behind his newspaper. I could only see his tuft of white hair. It was sticking up vertically, shot through with sun from the window. “Last one awake is the welcome wagon,” he said. “New household rule.”

He snapped a corner of the paper down and winked at me. “Morning.”

I smiled. “Morning.”

I pushed egg clumps around with my fork and stared out the window at the small brown shape in the pines across the lake. The junky-looking old Collier place, the one everybody called The Shipwreck. The Collier name was legend around Coeur-de-Lune, though the actual Colliers were long gone. They’d been rich, and a lot of them had died young. The small building across the lake where the Collier kids slept in summer had been falling apart since before I was born, and my mother always said they should just burn it. The Colliers’ main summerhouse, the fancy three-story one that had once been a few hundred yards up the shore, had been torn down when the land was split up decades before.

I’d seen trucks at The Shipwreck since it sold. Pedersen’s Hardware and Ready Windows. I loved the funny little house exactly the way it was, and now the new family would fix it up and ruin it.

So because they had a daughter my age my mother was totally blowing off the visit? Something was off. In her world of social niceties, frozen somewhere around 1955, new neighbors required baked goods. Not from a mix—new neighbors called for separating yolks from whites. And they definitely called for a personal appearance.

“Saw their car the other day when they were moving in,” my dad said behind his New York Times, making it shiver. There was a photo of Bill Clinton on the front page, shaking some dignitary’s hand, and when he spoke it looked like they were dancing.

My mother was transferring patty sausages from a skillet onto a plate. At his words, her elbows really got into stabbing the sausages and violently shaking them off the fork.

When she didn’t respond he continued, “Saw what was on the back bumper.”

That did it.

She dropped the plate between us with a thud and stalked into the dining room to tend to her latest batch of care packages for soldiers. They were arranged in a perfect ten-by-ten grid on the dining room table.

I forked a sausage and took a bite, burning the roof of my mouth with spicy grease.

After I swallowed I whispered, “What was on the car?” Maybe a bumper sticker my mother considered racy. Or inappropriate, to use one of her favorite words.

The day wasn’t blissfully free anymore, but at least it was getting interesting.

A new girl my age, just across the water, with parents who’d slapped an inappropriate bumper sticker on the family wagon. Maybe one of those Playboy women with arched backs and waists as tiny as their ankles, the ones truck drivers liked to keep on their mud flaps.

My dad set his paper down and started working the crossword. He did the puzzle in the Times only after finishing the easier ones in the Reno Statesman and the Tahoe Daily Journal. I liked to watch his forehead lines jump around when he worked on the Times crossword. I could tell when it was going well and when he was stumped, just by how wavy they were in the center.

He tapped on the paper with the tip of his black ballpoint the way he always did when he was struggling. He must have thrown in one or two extra taps because I glanced down. Above the “Across” clues he’d drawn a fish with legs. Ah. That would do it. According to my mother’s complicated book of social equations, one of those pro-Darwin anti-Christian fish with legs on your rear bumper meant you got a red ribbon, but only tied around a no-frills pound cake, and you got a duty visit from her daughter, but not from her.

My dad scribbled over the drawing and cleared his throat, then sent me a quick wink. I nudged my scrambled-egg plate closer to him and he took care of them for me in three bites, one eye on the dining room entryway as he chewed.

He went back to his crossword, and I got up to wrap the cake, curling the ribbon to make up for the terrible note. The unwelcome note. But as I was returning the scissors to the drawer I saw the black pen my mother had used. I’d mastered her handwriting years before. (Please excuse Laura from Physical Education, her migraines have been simply terrible lately.)

Quickly, expertly, I revised her words.

Welcome—Christies became Welcome!!—The Christies. We’re so thrilled you’re here!

Okay, maybe I went overboard.It was the kind of note Pauline Knowland’s and Suzanne Farina’s mothers would write, a message anticipating years of squealing hellos at Back-to-School night.

I tucked the note in my pocket, returned the pen to the drawer, and by the time my mother bustled in again I was at the table sipping orange juice, innocent as anything.

* * *

I dipped my paddle, breaking the glassy surface of the lake. I was the only one out on the water this early—the only human at least. The gentle ploshes and chirps and ticks of the lake felt like solitude; I knew them so well.

It was chilly on the water but warmth spread through my shoulders as I set my short course for The Shipwreck. My dad liked to speak in jaunty nautical terms like this; he always asked when I came home after a day on the lake—How was your voyage? Or—Duel with any pirates?

He gave me my kayak for my tenth birthday. My mother was just as surprised as me when he led us outside after the German chocolate cake. I’d opened up all my other gifts—two sweaters and six books and a Schumann CD I’d requested and a tin of Violetta dusting powder with a massive puff I’d not only not requested, but had absolutely no clue what to do with. My mother and I both thought the birthday was done.

Then he’d said, Might be one more thing outside.

He’d covered his surprise with a black tarp, pulling it off to reveal the sleek yellow vessel. So you can explore, he’d explained.

To my quietly fuming mother, he had said, his eyes dodging hers, Because she’s in the double digits now.

If they fought about it later—him writing such a big check without asking or, the more serious offense, the implication that he knew me best—I hadn’t heard it, and the heating duct in our small house ran right from their bedroom up to mine. I heard their whispered “discussions” all the time.

Eventually my mother grew to accept the kayak. She told her church friends that she liked me to play outdoors all summer. Sermons in stones and all of that.

The lake was small, a crescent of water only six miles around. At the narrowest, southernmost point, where we were, it was only four hundred feet wide. I could paddle across our end in two minutes without breaking a sweat.

Today I took it easy so I could size up the new neighbors as I crossed. I expected them to be outside commanding an army of painters and fix-it people, but the place seemed as run-down as ever, the gutters overflowing with pine needles, the dull wood shingles fringed in moss, the narrow dock as rickety as a gangplank. Whatever the trucks had been there for, it wasn’t visible from the back.

The house hadn’t been rented in more than six months. We were too far from the good skiing and stores, and you couldn’t take anything motorized on our little lake. Everybody wanted to live in Tahoe, or at least Pinecrest.

But there were signs of life. A rainbow beach towel draped over the dock ladder, bags of mulch stacked by the garden gate. The small square garden, to the left of the house, had been untended for years and used unofficially as a dog run. It was basically an ugly, deer-proof metal fence surrounding weeds, but obviously the new owners had plans.

Something else new—a small red spot on the edge of the dock, right at the center. Paddling closer, I saw that it was a kid’s figurine dangling from a nail. A plastic Ariel, from The Little Mermaid, her chest puffed out like when she was on the prow of the ship pretending to be a statue. It definitely had not been there the last time I’d snooped around The Shipwreck.

I wondered if the famous “daughter my age” had done it. I hoped not. It was the kind of joke I liked, and I didn’t want to like her. There was no way we would be friends, not when she found out what I was at school. The best I could hope for was that she would be what I called a Neutral. Someone I didn’t need to think about at all. Someone who didn’t make my day better or worse.

“You look exactly like an Indian princess.”

I jumped in my seat, almost losing my paddle.

A girl was swimming up to me. Her pale skin had splatters of mud on it and she had threads of green lake gunk in her hair. Red hair. The toy Ariel on the dock had definitely been her idea.

“You know, like Pocahontas or someone, with your dark braid, in your canoe?” she continued, breaststroking close enough that I could see it was freckles on her shoulders, not dirt. I’d never seen so many freckles. There were goose bumps, too, which didn’t surprise me. The lake wasn’t really comfortable for swimming until after the Fourth of July.

I composed myself enough to correct her. “Kayak.”

“Right, canoes are the kneeling ones. You coming to see us?” She tilted her head at the house.

Before I could answer, she closed her eyes and sank down into the water up to her hairline. When she popped back up, she squeezed her nostrils between her thumb and index finger to clear them.

“My mother wanted me to bring you this,” I said. I stashed my paddle in the nose of the kayak, yanked my backpack from the front seat, and unzipped it so she could see the cake under its pouf of plastic wrap. “To welcome you and your parents.”

“Parent. Singular. So you didn’t want to bring it? Your mom made you?”

I still wasn’t sure what category she belonged to, but she was definitely not a Neutral.

“I didn’t mean that,” I said.

I was starting to drift from the dock but she swam close and for a second I worried she would grab the hull and capsize me.

At the thought, I automatically gripped my shorts pocket, squeezing the familiar shape, smaller than a deck of cards, through the worn cotton. The Ziploc was only insurance. My good-luck charm couldn’t get wet.

The swimming girl’s eyes darted from my face down to the edge of my shorts, where my hand clutched. She cleared water from her ears, repositioned her purple bathing suit straps, and slicked her red hair back with both hands.

The whole time she performed this aquatic grooming routine, her eyes didn’t budge from my right hand. I forced myself to let go of my pocket and fidgeted with my braid instead.

But her eyes didn’t follow my hand. They stayed right on the zippered compartment of my shorts.

I’d have to invent a new category for this girl. She missed nothing.

I would set the cake on the dock. I’d paddle over to Meriwether Point like I’d planned and have my picnic. Lie in the sun as long as I wanted, with nobody to bug me, on my favorite spot on the big rock that curved perfectly under my back. Later I’d collect pieces of driftwood for a mirror I was making and go swimming in Jade Cove.

I had all kinds of plans for the summer.

“Well, I’ve got to...” I began.

“Do you want to...” She laughed. “What were you saying?”

“Just that I should go. I told my mom I’d help around the house.”

“Where’s your place?”

I pointed.

She paddled herself around to face the opposite shore. “Cool. We can swim that, easy. We can go back and forth all the time.”

She was so sure we’d be friends. She was sure enough for both of us.

“Come in and we’ll eat the whole cake ourselves,” she said, completing her circle in the water to face me. “My mom’s in Tahoe. She won’t be back ’til late.”

“I wish I could.” Stop being so nice.I can’t afford to like you.

“Are you going to be in ninth?” she went on, panting a little as she tread water.

“Yeah.”

“Me, too. You can say you were telling me about the high school. That’s helpful.”

“There’s not much to tell about the school. It’s tiny. It’s not very good. The football team is the Astros, because everyone around here is seriously into the moon thing.”

“See? I need you. Come on.”

I didn’t offer the most valuable piece of advice—If you want to make friends at CDL High, don’t hang around with me.

“Please. Tell your mom I totally forced you to eat a piece of cake and help me unpack.” The girl grinned, sure of her charm.

It was a wide grin that stretched out the freckles on her nose, and I couldn’t resist it.

* * *

Her name was Casey.

“Casey Katherine Shepherd, named after Casey Kasem, that old DJ,” she said, sprinting ahead of me up the dock to her house. She wrapped the rainbow beach towel around her bottom half as she ran. “My mom was obsessed with him,” she called back, leaping onto the sandy path in the sloping, scrubby patch of lawn behind the house. “She has CD box sets of radio countdowns from 1970 to 1988. What’s your name?”

“Laura. Named after a great-great-aunt I never met. But I’m guessing she wasn’t a DJ.”

Casey turned so I could see she was laughing, but she didn’t stop running. She didn’t rinse her feet off, though there was a faucet right there by the back door, but pounded up the rotting wood steps, opened the screen door, and walked inside, tracking muck.

I’d always wanted to go inside The Shipwreck. When I was little, I’d imagined wood walls, hammocks, ropes dangling from the ceiling. Maybe a captain’s wheel.

But it was only an ordinary room crammed with moving boxes. The small windows and dark green paint made everything gloomy.

“Well, welcome to the neighborhood.” I pulled the cake from my backpack and set it on a brown box labeled Stuff!

“I have no clue where the knives are, so here.” Casey yanked at the curly ribbon. She broke the cake in two pieces, handed me one, and knocked her hunk against mine. “Cheers.”

“Cheers.”

“Did you know this used to be a kids’ cabin for another house that’s not here anymore, and everyone calls it The Shipwreck?” she said, crumbs on her bottom lip.

I nodded, finished chewing. “Who told you, your Realtor?”

“We didn’t have a Realtor. My mom bought the house from the owner. The guy who fixed the windows told her. When he realized my mom was the colorful type he wouldn’t stop talking about it. Flirting with her.” She rolled her eyes. “A house with real history, he said. Built in the 1920s. One of a kind.”

The colorful type. I was tempted to ask if her colorful mother knew the stir her quadruped bumper-fish had caused. “I noticed the Ariel on the dock. Did you put it there because...”

“Yes. Screw them if they think The Shipwreck is an insult, it’s cool the way it is. Look, you can still see the marks from the bunk beds.” She shoved boxes around to show me the dark rectangles in the wood floor. “There were five bunks, so I guess ten kids could sleep down here. And one babysitter had to deal with them all summer, I bet.”

“My mother grew up in our house. She says the boys who stayed here in the forties and fifties ran wild all summer. But she never told me about the bunk beds.” I bent to touch one of the marks. “Cool.”

There were no bunk beds now. The only furniture in the room was a saggy, opened-out futon against the long wall. It was unmade, the imprint from a body still visible in the swirl of sheets.

“My mom’s sleeping down here for now,” she said. “She’s using one of the rooms upstairs for her studio because the light’s better and the daybed she ordered hasn’t come yet. Come see my room.”

I followed her up the dark staircase. “So she’s an artist?”

“Ultrabizarre stuff, but people pay a ton for it because bizarre is in.” She thumped her hand on a closed door as we passed, but didn’t offer to show me any of the ultrabizarre art.

“When’s your furniture coming?” I followed her down the narrow hall.

“Our last four places were furnished so my mom’s off buying stuff.”

Last four places? As I considered this, Casey disappeared into a wall of gold. At least that’s what I thought it was until I got closer and figured out it was yellow candy wrappers stuck together in chains, dangling from her doorjamb to form a crinkly, sunlit curtain.

“I made that for our hallway in San Francisco,” she said from the other side of the swaying lengths of plastic. “I was going through a butterscotch phase.”

“I like it,” I said. Did I? I had no idea. I was just trying to step through the ropes of cellophane without breaking them. “How many wrappers did it take?”

“A hundred and eighty-eight. My mom put my real door on sawhorses in her studio, for a table.”

I could only imagine what my mother would say if I tried to replace my bedroom door with candy wrappers. When I was little, she didn’t let me take hard candy from the free bowl at the bank, saying it was a scam they had going with the dentist.

But the fact that Casey’s mom apparently didn’t worry about cavities wasn’t the weirdest part. The weirdest part was that this girl had voluntarily taken her bedroom door off its hinges, not minding that now her mother could peek in whenever. She could catch her undressed, or interrupt her when she was writing in her journal, or yell at her from downstairs right when she’d reached the best part of her book.

My bedroom not only had a door—the wooden variety—but a lock. I used it twice a day, when I transferred my good-luck charm between my pocket and my pillow.

I stashed other objects in my room, too. I had a Maybelline Raspberry Burst lip gloss tucked into the bottom of my Kleenex box. A Cosmopolitan I’d filched from the dentist hidden inside the zippered cushion of my desk chair, with 50 Tips That’ll Drive Him Wild in Bed. I had come to know well the thrill of concealing objects in my room, the secret electric charge they emitted from their hiding places. My bedroom was strung in currents only I knew about.

I didn’t tell her any of this. I’d known her only twenty minutes.

“Didn’t you get sick of all that butterscotch by the end?”

She laughed. “Totally. I threw out the last fifty.”

We sat facing each other on her unmade single bed, inside a fortress of brown moving boxes, finishing the cake. She was still wearing her wet bathing suit and towel. I would never wear a thin bathing suit like that, even in the water, and definitely not out of it. But Casey, named after the male DJ, was flat as a boy. And something told me she wouldn’t have cared about covering up even if she wasn’t.

As we ate, and she talked about San Francisco—the freezing fog, the garlic smell that would drift up the apartment air shaft from the restaurant below—I monitored a damp spot spreading out on her yellow bedspread. It expanded around her hips, like a shadow. My mother would have gone ballistic; she pressed our sheets once a week and had a dedicated rack in the laundry room for used beach towels.

By my last bite of cake I had to admit that I liked this sturdy, confident girl. And I felt bad for her. She said she’d had no idea she was moving until her mom announced it on the last day of middle school.

“We’d only been in San Francisco for a year, and I was all registered at Union High for September, then all of a sudden my mom heard about this house, and here we are. Goodbye, Union. Hello, Coeur-de-Lune High.”

“People never say that. They say CDL High.”

“Got it.”

“Which is kind of dumb since it’s exactly the same number of syllables.”

She laughed, and I realized in that second just how much I wanted her to like me. I couldn’t resist going on. “Like I said, it’s not such a great school.”

“Go, Astronauts,” she said, laughing, shaking her fists as if she was holding miniature pom-poms.

“Astros.”

“Right. Keep the insider tips coming.”

“I’m definitely not an insider, I... So why’d your mom want to move?”

“She’s impulsive like that. You’ll get it when you meet her. We lived in a bunch of places before San Francisco. Reno, Oakland, Berkeley. Then suddenly she was all about nature. Fresh air, peace and quiet so she could work and I could... I don’t know. Suck in all the fresh air.”

“Weren’t you sad? Leaving your friends in San Francisco?”

“Yeah, but...my mom’s my best friend.”

I licked crumbs from my fingers. “That must be nice. My mother is...”

Strict? That wasn’t the right word. Cold was closer to the truth, but not quite fair. My mother took my temperature when I was sick, and remembered that I liked German chocolate cake, and once said I played the piano like an angel. She asked me for my Christmas list the day after Thanksgiving. Rigid? Overly efficient? Judgmental? None of them added up to a good answer.

“She’s what?”

“She’s older than most mothers.”

“Grandma old?”

“Sixty-two. I’m adopted. And my dad’s almost sixty-four. But my mother seems older than him because she’s kind of religious.”

“Like that nutjob fanatic mom in Carrie? I have that, have you read it? It’s awesome.”

“No, but I saw an ad for the movie on TV. She’s not like that. She’s just... I don’t know. Old-fashioned.”

“Bummer.”

“Yeah.”

Bummer. I liked that tidy summary of my relationship with my mother. It took something that made me feel freakish and confused and brought it into the light, transforming it into a typical teenagey complaint.

I didn’t tell Casey she was sharing her cake with Sister Christian, or about how Pauline Knowland stole my bra during a shower after gym last September, so I’d spent the rest of the school day hunched over and red-faced.

I didn’t tell her how hard it is in a small town, where you’re shoved into a role in fifth grade and you can’t escape it no matter what you do, how it squeezes the fight out of you, because everybody knows everybody and you aren’t allowed to change.

And I didn’t tell her that one of the things hidden in my bedroom was a homemade calendar taped to the inside back wall of my closet, where I crossed off the number of CDL High days I had to survive until graduation. 581.

Go Astros.

Instead I said, even though I wasn’t that interested in horror novels, “Can I borrow Carrie sometime?”

“Sure.” Casey jumped off the crumb-strewn bed and went through boxes, tossing books on the floor.

She had more books than I did, and I had a ton. I even had a first edition of Little Women. Casey had Little Women, too, I noticed, and I picked it up off the floor, about to ask if she liked it and if she’d ever read Little Men or Rose in Bloom,which could be preachy but had some entertaining parts.

Only when I looked closer I realized it wasn’t Little Women. It was The Little Woman.

And judging by the cover, it was definitely not an homage to Louisa May Alcott. It had a lady sashaying down her hallway in a skimpy white nightgown, with a gun stuffed down her cleavage. Behind her, at the other end of the hall, you could just make out a shadowy male figure.

The perfect wife is about to get the perfect revenge, it said.

“We had this fantastic used bookstore down the street from our last place,” Casey said, her head down in the moving box. “It’s one thing I’ll miss. That and foghorns. And pork buns.

“Found it,” she said, lobbing a paperback of Carrie at me. “Keep it as long as you want. And take this, too. You might be into it, being adopted and all. I went through a phase where I totally imagined I was adopted because of that book. It seemed so romantic.”

“It’s not, believe me.”

The cover of Carrie, with a pop-eyed teenage girl covered in streams of blood, creeped me out. I’d probably just skim it. The other one looked pretty good, though. Lace, it said in pink, on a black lacy background. The book every mother kept from her daughter at the bottom. Which sounded promising.

This daughter would definitely keep it from her mother. Maybe I could stuff it down one of my winter boots. It was too big to conceal inside my Kleenex box.

“You’re lucky your mother lets you read whatever you want,” I said.

“My mom’s annoying, too. She can never stick to one hobby. She gets totally into something, then just when I get interested she’s onto something else. It sucks.”

It didn’t sound sucky at all. It sounded kind of great. My mother hadn’t developed a new hobby in decades. She was content with her baking and her needlepoint and her charitable bustling-around. Even my father was pretty stuck in his ways. He had his crosswords, and his never-ending house repairs, and his twice-a-week volunteer job at the Historical Society which consisted—as far as I could tell—of playing backgammon with Ollie Pedersen above the hardware store surrounded by old photos.

“Last month it was pressure valves,” Casey said.

“Like, plumbing?”

“No. This philosophy on stress relief. She got this book by some lady named Alberta R. Topenchiek and it’s all she talked about for weeks. Pressure Valves and Self-Monitoring of Wants versus Needs and Minor Stress Triggers versus Major Triggers.”

I laughed.

“I almost threw the book down our garbage chute, I got so sick of talking about it. Anyway, Alberta R. Topenchiek says everyone has to have a pressure valve. The thing they do when nothing else makes them feel good. My mom’s is her art, and mine’s swimming. What’s yours?”

“Kayaking,” I said. I’d never thought of it that way before, but of course it was.

“Will you teach me? I’ve never done it.”

I hesitated a second but I didn’t have a chance against her smile. Her smile, her ridiculous candy-wrapper curtain, her directness.

And her total confidence that the only thing separating us was a few hundred feet of lake water.

“Sure.”

I stayed at Casey’s for three hours that first day, helping her organize her books and clothes, listening to the Top 40 radio countdown CD for 1982. I’d never seen someone sing along so completely unselfconsciously to Toto’s “Africa”before. Usually people sort of mumbled it in the back of their throats, looking around as if they were worried they’d get caught.

When she wasn’t singing I tried to stick to safe topics. The principal is married to the history teacher. Hot lunch in our district is $3.60, or you can do the salad and fruit bar for $1.80.

But Casey kept steering the conversation back to exactly where I didn’t want it—me.

“So what are your friends like?” she said, folding a green sweater.

“I used to hang out with this girl Dee, but she moved to Tahoe last year.”

This was a lie. Dee and I had been friends in third grade, and she’d moved away in fifth, right when I could have used her. Fifth grade was when Pauline Knowland decided I had entertainment value.

“Are you allowed to go on dates yet?”

“It hasn’t come up,” I admitted.

“Right. It’s early.”

“What about you? Have you had a boyfriend yet?”

Casey got a funny half smile, looking at a spot over my right shoulder. She spoke slowly, as if she was in a witness box, enunciating for the court reporter. “No, ma’am. I have not had a boyfriend yet.”

With the cake polished off, she set a big pink-and-white Brach’s Pick-a-Mix bag on the bed. Root beer barrels, lemon drops, toffee, and starlight mints. No butterscotch.

“Sustenance, because we’re working so hard,” she said.

By the time I kayaked home, promising to return at ten the next morning, Casey’s closet was organized, her CDs were lined up alphabetically along one wall, and my back molars were little skating rinks of hard candy.

I ran my tongue across my teeth as I paddled, trying not to smile.

3 (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

Alexandra the Great (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

I spent five hours with Casey the next day, and seven the next, and as the long summer days ran on it became easier to count the hours we were not together.

She proved to be a quick study on the kayak but I still sat in back, where I could take over if things got dicey. She liked to go fast. We’d be floating along, lazy and destinationless, and she’d shout, “Let’s do warp speed!” and we’d fly, enjoying a windblown rush for a minute until we inevitably knocked paddles and collapsed into laughter.

I showed her my favorite spots on the lake. The flat, sunny rock at Meriwether Point, where I’d always picnicked alone, and shady little Jade Cove, where tiny fish tickled your ankles and there was a downed pine tree that made a good, bouncy diving board.

One day I took her to Clark Beach on the North shore. We ate cheese-and-sourdough sandwiches and drowsed in the sun, and it would have been another perfect day if I wasn’t slightly on edge, worrying that Pauline Knowland and her pack of blow-dried minions would show up. I hadn’t taken Casey anywhere so public before. But Pauline didn’t come. She spent most of her summer afternoons at the mall or at Pinecrest Lake Beach, where there was more action. Action was in short supply around Coeur-de-Lune.

Sitting behind Casey in the kayak day after day, I got to know the pattern of freckles on her shoulders. She didn’t brush her hair before we met by her dock each morning so the back rose up in a snarled mat, revealing the flipped-up size tag of her purple bathing suit.

Freckles on pink skin, a tangle of red hair, an upside-down Jantzen Swimwear size six label: these are the strongest visual memories of that summer before high school.

I had a journal my dad gave me when I was seven, a puffy pink thing with A Girl’s First Diary on the cover in gold script. I hid it inside a hollowed-out copy of Silas Marner on my bottom bookshelf, and concealed the key in a mint tin in my third-best church purse.

I wasn’t a dedicated diary writer. My entries were sloppy and I sometimes went weeks without turning the key in the little gold lock. But on June 13, seven days after I met Casey, I wrote:

A summer friend. Ariel. She’s...disarming.

TGTBT

Disarming. (One of my PSAT words.) TGTBT. Too good to be true.

The acronym—such an obvious attempt to sound like other fourteen-year-olds—wasn’t the most pathetic part. It’s that I was afraid she’d vanish if I wrote her real name.

It’s not that I didn’t think she liked me. I knew she did. I made her laugh, not polite laughs but snorty diaphragm laughs. I didn’t talk much about my life at school, but my family was safe material. I told her how my dad and I once secretly replaced the gritty homemade apricot fruit leather in my mother’s charity care packages with Snickers bars. How he always saluted me if we met in the upstairs hallway, because of my vaguely military cargo shorts.

“You’d like my dad,” I said.

We were swimming in Jade Cove, floating on our backs, Casey in her purple one-piece, me in my loose black T-shirt and underwear, once again pretending I’d forgotten to bring a suit. I’d carefully rolled up my shorts in a towel and set the bundle on a rock, far from the water.

Disarming. She had disarmed me. I rarely separated myself from the charm I kept in my pocket, but for her I did. I wasn’t ready to tell her about it, though.

“Would he like me?” Casey said, eyes closed, arching her back to stay afloat so her stomach made a little purple island. The skin on her nose was bright pink, and the freckles there merged closer every day.

“Definitely.”

“Hey. Why do you always wear them?”

“Hmm?”

“Your cargos. I’ve never seen you in anything else. Not that I mind.”

“I just like them. The pockets are good for collecting things. Hey, I have oatmeal cookies in my backpack. Are you hungry?” I splashed over to the beach.

* * *

Two weeks into summer we still hadn’t met each other’s parents. We rendezvoused at Casey’s dock every morning and stayed on the water all day.

I said my mother got on my nerves and Casey accepted this. She kept me out of her house, too, telling me her mom wanted to fix the place up before inviting me over.

“She’s dying to meet you, though,” she said. “She just wants to get the house done first. She was mad you saw it before it was finished.”

“Does this mother of yours really exist?” I teased. I could tease her by then.

“She’s in some kind of retro homemaking phase. Yesterday she drove all the way to Twaine Harte for an antique firewood holder. I just hope she puts up my bedroom curtains before she gets bored with antiquing and moves on to rock climbing or whatever.”

Casey scattered crumbs like this about her mother all the time. I stored them up, greedy for more. I was as fascinated by her fond, indulgent tone of voice as I was by the composite picture they created of this person I hadn’t met yet.

On June 26 I wrote in my diary:

Ariel’s mother—Alexandra Shepherd

Only 36.

+ Once a card dealer in Reno.

+ Makes lots of $ off her art. Scandalous art?

+ Let her boyfriends sleep over til Casey asked her not to.

= Exact opposite of Ingrid Christie

* * *

One afternoon in late June, as I was showing Casey how to make a hard stop-turn in the kayak, I got an official nickname, too.

“Slow down, Pocahontas, I didn’t quite get that,” she said.

Pocahontas. The four syllables were a sweet drumbeat in my head for the rest of the day. Casey had sort of called me Pocahontas the first day we met. But this was different. I’d never been given a nickname by a friend.

When I left her dock a few hours later, she sat on the edge to see me off, legs dangling over the silvery-gray wood. I was late for dinner and was already paddling hard when she called out, feet now churning the water, “I almost forgot, come early tomorrow. My mom wants you for breakfast.”

I showed off my stop-turn. “Really?”

“The house is done so she wants to meet you. Nine, okay?”

I hadn’t planned to say it out loud. I was giddy from the day, the breakfast invite, and my diary name for Casey just slipped out at the last second. “Okay. Goodbye, Ariel.”

But when I felt myself saying it I got shy, and her nickname came out so soft it got lost crossing the water.

“What?”

I gathered my courage and repeated it, louder this time. “I said, goodbye, Ariel.”

She stilled her legs and tilted her head, considering. Then she grinned, kicking out a high, rainbowed arc. “I love that.”

As I started to paddle away again, Casey pulled the Disney figurine off the nail by her legs and waved it.

“Twins,” she yelled. Then she set it on her shoulder and made a goofball face.

I smiled all the way home.

But in my diary that night, I wrote:

65 days til school. Wish there were zeros at the end. Infinite zeros. 00000000000000000000

Before I slipped the diary back inside Silas Marner, I filled in the string of zeros, making each oval into a sad face.

It’s not that I thought she’d instantly transform on September 2. Change into someone cruel, from a fourteen-year-old who could still make dumb jokes about Disney princesses into a sneering wannabe grown-up like some of the high school girls I’d observed. I knew she was better than that.

It’s just that she didn’t know what a machine school could be. I’d already been processed through the machine, because our town was so small sixth through twelfth were in the same building complex, the high school separated only by a covered walkway. My reputation as Sister Christian had already traveled down that walkway, I was sure of it.

And the machine had decided that I didn’t deserve a friend.

I had this fantasy that Casey would say she wasn’t going to CDL High after all, that her mother would have an overnight religious conversion and send her to the Catholic girls’ school four towns over. It would solve everything, and it wasn’t completely ridiculous. I knew all about her mom’s impulsive nature. If I scattered some pamphlets about St. Bridget’s and maybe some enticing religious icons on her futon, I could probably make Catholicism her next obsession.

But even if I could pull it off, judging by what Casey had told me, her mother would end her fling with the Lord long before first-day registration.

Casey was definitely bound for CDL High.

It was bad enough, worrying about the time limit on Casey’s friendship. Then I met Alex.

* * *

The morning of the breakfast, I wore my hair loose, and though I wasn’t willing to alter my Ziploc-inside-cargos arrangement on my bottom half, I went fancier on top, with a light blue peasant blouse. It was the one nice shirt I owned that was sufficiently baggy.

Halfway across the lake I could see them waiting for me on their dock. Both of them short, with bare legs. Both with sun glinting off their red hair.

But as I got closer I could spot the differences between them. Casey’s hair was shoulder length and bone straight; her mother’s fell in spirals past the waist of her cutoffs. Casey was sturdy and slightly bowlegged, giving the impression that she was firmly planted on the ground. Her mother, though no taller, was fine-boned. All jumpy vertical lines. Alexandra was like Casey, made with more care. And though she was thirty-six, she could have passed for a college girl.

She reminded me of one of the redheads in my European art book, a full-page print I’d tried (unsuccessfully) to copy. Not the woozy Klimt lover, who looked like she’d been folded to pack in a trunk. I liked this painting better: a modern Russian oil of a young auburn-haired dancer surrounded by chaotic brushstrokes, her eyes defiant, her arms so fluttery they seemed to disturb her painted background. That’s what Alexandra was like.

“Need help?” Alexandra darted across the dock as I tied up. To Casey she asked, wringing her hands, “Does she need help?”

“She’s fine, Mom. Laura’s a pro.”

I climbed up the ladder, self-conscious under her steady gaze. When I tried to shake her hand she pulled me in for a hug, speaking close to my ear. “Alexandra Shepherd, but call me Alex, of course.”

My dad’s version of a hug was one palm rapping me on the back like I was choking on a chicken bone, and my mother limited her displays of affection to awkward shoulder pats.

This was a full-body squeeze, and the force of it, coming from someone so little, unnerved me. When she finally let go she didn’t really let go. She only leaned back, still so close I could count the freckles on her nose. She didn’t have as many as Casey.

“Laura,” she said, cupping my jaw in both warm hands.

“Mom.”

“Oh, I’m just excited. Your first friend in the new town. I’m sorry, Laura.”

“It’s okay.”

It wasn’t exactly okay, though. I didn’t know where to look. She still had both hands under my chin and her gray eyes were darting and circling, scanning my features.

“Careful, Laura, she wants you to sit for her. When she analyzes someone’s face like that, she’s making plans. And it sucks, believe me.”

“You caught me.” Alex dropped her hands and stepped back. “Laura, you’re welcome here anytime.”

Some people pronounced my name Low-ra, and some people said Laah-ra, and neither was correct. It was just Laura, standard pronunciation.

Alex said it like there were three syllables, not two, adding a breathy cascade within the vowel. Lau-aura. She said it like a declaration, like I couldn’t possibly be anyone else, and like meeting me confirmed that I was just as wonderful as Casey had said.

“I’m starved and you’re freaking out my friend.” Casey was already running to the back door. She was barefoot, wearing her purple bathing suit, but she’d pulled on cutoffs for the occasion.

Alex didn’t speak as we walked up the path together, and as she held open the screen door, she watched me closely again, her eyes monitoring my face for a response as I took in the fixed-up house.

She’d transformed it. Newly white walls brightened up the long room and set off the blue of the lake and the green of the pines coming through the small, high windows and screen door. There were the antiques I’d heard about—a circular wooden table and chairs near the tiny kitchen, a deep armchair on a braided oval rug next to the fireplace, and a low yellow daybed had replaced the futon in one corner. But she hadn’t sanded away the marks in the floor from the old bunk beds, I was relieved to see.

“Like it, Laura?” she said, fidgeting with the hem of her white eyelet tank top.

“It’s perfect.”

“You did a good job, Mom,” Casey said from the kitchen table, a croissant hanging from her mouth. “Now can you two please stop being so freaking polite so we can eat?”

* * *

When Alex was in the kitchen slicing an almond pastry, Casey whispered across the small table, “I’ve never seen her so quiet. She must really want to paint you. Watch out.”

“I don’t mind.”

* * *

Alex was more relaxed each time I came over. She stopped saying my name more than the standard amount, and began to match Casey’s description. She did talk too much. She did launch from one hobby to another so fast it was hard to keep up.

And she did want to paint me. I chalked up her odd behavior on that first morning to the overwhelming impression I’d made as a potential subject, and I was flattered.

By midsummer we’d settled into a routine. Mornings I sat for sketches on the back porch, muscles aching, but happy to let Alex and Casey entertain me.

One hot day in late July Alex had me in a stiff-backed dining room chair with my hair in a tight bun. She said she was trying to capture something in my eyes. That I was “an old soul but tried to hide it,” and she hadn’t managed to draw this to her satisfaction.

“You have a... What is it, Case? What’s in her eyes that’s so hard for me to get right? That bit of sadness mixed with... I don’t know what.”

“That’s a neck cramp mixed with the desperate need to pee. I know the feeling well.” Casey was sprawled in the sun by my feet, a paperback of Peyton Place tented above her face.

She read a section aloud: a couple writhing around, monitoring the status of the man’s erection, panting out a play-by-play of their lovemaking.

When Casey wasn’t acting out Peyton Place, making me laugh until I broke form, Alex would lecture us on her latest bird. Her birding mania had abruptly replaced a brief heirloom tomato kick. She’d even invested in binoculars and a leather journal for recording her sightings. Casey and I knew as much about the yellow-headed blackbird as the local Audubon Society.

“Their scientific name is Xanthocephalus,” Alex said from behind her easel. “And the Tahoe basin has lost hundreds in the last ten years, isn’t that awful? Their call is so unusual. Like...a rusty gate opening over and over, and—”

“Oh, my God, Mom. You’re a rusty gate opening over and over. Give it a rest.”

Alex popped her head above her easel. She had her curls piled on top of her head, and a double pine needle had fallen onto it like a hair ornament. “Laura’s interested. Aren’t you, Laura?”

“Definitely.”

“She’s just being polite. Laura doesn’t give a shit about the Xanadu birds anymore and neither do I.”

“Xanthocephalus,” I said, laughing.

“Kiss-up,” Casey said.

“Dang it all, Case, you made me mess up.” Alex had the same laugh as Casey, full-throated and coppery. “Naughty girl.”

A few days later, Peyton Place and the yellow-headed blackbird were replaced by My Sweet Audrina and the dark-eyed junco bird. The material varied, but the two-woman show did not. Alex the flighty. Casey the sarcastic.

And me. I was the audience. Sometimes the egger-on or the mediator. They each tried to get me on their side, and I loved every second of this gentle tug-of-war.

After lunch Alex would wander upstairs to her studio—painting was the one constant in her day—and it became me and Casey again, kayaking and swimming and picnicking until dinner. They invited me for every meal, but I only stayed one out of five times, figuring that this amount would not push my mother over the edge.

I told my mother the Shepherds’ car was used and they couldn’t pry the anti-Christian fish off. She hmphed at me, not buying it but not forbidding me to see them, either.

By August I’d thrown myself into the Shepherd household completely. Without a flicker of loyalty to my own slow-moving, well-meaning, predictable parents.

I kayaked across the lake every chance I got. I spent the night almost every Saturday, ignoring my mother’s hmphs, her narrowed eyes.

On Sunday, I rushed over again as soon as I ditched my church clothes. Paddling hard, like I was racing backward across the river Styx, from the land of the dead to the land of the living.

I wished school would never start.

4 (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

The Machine (#u236f77e7-f97a-50a5-9940-7b51bc16a6b9)

September 2