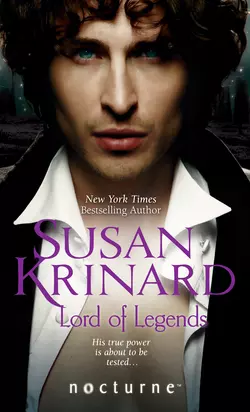

Lord of Legends

Susan Krinard

Forbidden Desire…Powerful and seductive, shapeshifter Arion could possess any female he desired – until now. Cursed to live as a man, Arion’s only hope for freedom is the enchanting Lady Mariah Donnington’s innocence. Abandoned on her wedding night, frightened of her hidden, otherworldly heritage, Mariah is instinctively drawn to the mysterious stranger she discovers imprisoned on her husband’s estate.But as the secret of Arion’s magical identity unfolds, their friendship burns into a passion that cannot, must not, be consummated. For to do so would destroy them both…

Praise for the novels ofNew York Timesbestselling author Susan Krinard

“Animal lovers as well as romance readers and those who enjoy stories about mystical creatures and what happens when their world collides with ours will all find Krinard’s book impossible to put down.”

—Booklist on Lord of the Beasts

“A poignant tale of redemption.”

—Booklist on To Tame a Wolf

“A master of atmosphere and description.”

—Library Journal

“Susan Krinard was born to write romance.”

—New York Times bestselling author Amanda Quick

“Magical, mystical, and moving … fans will be delighted.”

—Booklist on The Forest Lord

“A darkly magical story of love, betrayal, and redemption …

Krinard is a bestselling, highly regarded writer who is deservedly carving out a niche in the romance arena.”

—Library Journal on The Forest Lord

“With riveting dialogue and passionate characters, Ms Krinard exemplifies her exceptional knack for creating an extraordinary story of love, strength, courage and compassion.”

—RT Book Reviews on Secret of the Wolf

Also available from Susan Krinard

COME THE NIGHT

DARK OF THE MOON

CHASING MIDNIGHT

LORD OF THE BEASTS

LORD OF SIN

Lord of Legends

Susan Krinard

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Now I will believe

That there are unicorns …

—William Shakespeare,

The Tempest

PROLOGUE

New York City, 1883

“MAMA? Mama!”

Portia Marron looked at Mariah the same way she had for the past week, her eyes slightly glazed and unfocused, as if she could no longer see the real world.

But the world as Mariah knew it hadn’t been real to her mother for many years. Portia saw one much more beautiful, inhabited by wondrous creatures who sometimes crossed the barriers in her mind to whisper in her ear.

“Mama,” Mariah said again, squeezing the frail hand. “Please come back.”

Briefly, the faded blue eyes cleared. “Is that my little girl?” Portia asked in the croak of a voice seldom used. “Now, now. Don’t you fret none.”

Mariah looked away. Mama had relapsed so far that she was living in the distant past, when Papa had still been working on the railroad with his own hands and muscle, and Mama had been a rancher’s daughter.

Papa had tried to put that past far behind him. He’d done his best to buy his way into New York society, but his efforts had proved largely futile. Wealthy as he was, he was still one of the nouveau riche, without an ancient family name to open the gates.

Not that Mama had cared. In fact, it had always seemed that the harder Papa pushed his family to enter a society that rejected them, the deeper Mama retreated into her realms of fantasy.

Mariah patted the withered flesh stretched over the hills of blue veins. “Yes, Mama,” she said. “Everything will be all right.”

The brief moment of coherence left Mama’s eyes. “Do you hear them?” she asked dreamily. “They’re louder now. They’re calling me.”

It took all Mariah’s control not to squeeze too tight before she released Mama’s hand. “Not yet, Mama. They don’t want you yet.”

“But they sing so beautifully. Can’t you hear?” Mrs. Marron rolled her head on the down pillow. “So sweet. You must hear them, my darling. They will be coming for you, too.”

Mariah shuddered, knowing her mother wouldn’t see. “Perhaps someday, Mama.”

“Someday,” Portia sighed, releasing her breath too slowly. Then she turned her head toward Mariah, and a strange ferocity took hold of her gaunt face.

“Don’t let those doctors take me back,” she said. “Promise me, Merry. Promise me you won’t let them take me.”

Sickness surged in Mariah’s throat. “No, Mama. I won’t.”

“Promise!”

“I promise.” She sketched a pattern across her chest just as she’d done as a little girl. “Cross my heart and hope to die.”

Mrs. Marron relaxed, the tension draining from her body. “You’re a good girl, Merry. Always have been. You never cared about them snooty harpies. The best of them ain’t as good as you.” She smiled again. “You remember when you was little, and I read you them fairy stories? How you loved them.”

“Yes, Mama.” She had loved them: fairy tales and all the romantic adventure stories about lost princes and hidden treasures. She’d half believed they were true. Not anymore.

Mama felt across the sheets for Mariah’s hand. “Don’t give up, Merry,” she said. “Sometimes the good things seem far away. Good things like love. But it’ll find you, my girl. Sooner or later, you’ll have to believe in something you can’t see.”

That was the old Mama. The one who had been less and less in evidence as the months and years passed. The one who never would have survived in the asylum if not for her invisible companions.

The one Mariah missed so terribly.

She leaned over to kiss Mama’s cheek. “You should sleep now,” she said. “When you wake, I’ll bring you a nice cup of tea and a few of Cook’s fresh biscuits.”

“Biscuits.” Mama slipped away again. “I wonder if they have biscuits there. I’ll have to ask.…” She closed her eyes and almost immediately sank into a deep sleep.

Mariah’s legs were trembling as she rose from the chair beside the bed. All her efforts had gone for nothing. She had been the one to insist that Mama be brought home, so she could care for her. But she’d failed. She was certain that Mama was dying for no other reason than that she wanted to go to that other place.

A place that wasn’t heaven. It wasn’t even hell. It didn’t exist at all and never had.

Mariah trudged down the stairs, hardly bothering to lift her skirts above the floor. The idea of dressing for dinner was repellent to her, but Papa would insist. He would not abandon the life he’d fought so hard to achieve, not even with death so close in the house.

“Miss Marron?”

Ives bowed slightly, always proper, as only an English butler could be. “Mr. Marron requests your presence in his office.”

“Yes, Ives. I shall be there presently.”

“Very good, miss.” Ives bowed again, passed her and continued up the stairs. Mariah wondered if Papa had sent him to check on Mama. He still loved the woman he’d married, though in truth she’d left him long ago.

Mariah continued on to the office and knocked on the door. Papa let her in, chomping furiously on an unlit cigar. His big bear paws hung in the air, as if he didn’t know whether he ought to embrace her or fend her away.

“Well, sit down,” he said, gesturing toward a chair. “I’ve something to discuss with you.”

She sat and smoothed her skirts, reminded again of how much she detested the new fashion of large, projecting bustles.

Papa cleared his throat. She sat up straighter. He still wanted her to be the proper lady, even when no one was there to see or care.

“You know your mother and I had always planned for you to have an advantageous marriage,” Papa began, sinking heavily into his leather chair. “You asked that we put off such discussions while … while your mother was indisposed. But it is now clear that she will not recover as we had hoped.”

“She needs more time,” Mariah said, knowing that she was lying to herself as much as to him. “Please, Papa. Be patient just a while longer.”

“No.” He stubbed out his cigar and leaned heavily on the ebony desk. “No more waiting, Merry. It’s time and past that you were married.”

To someone who will take me before I begin showing the same signs as Mama, Mariah added silently. If such a person existed.

“You may wonder if I have someone specific in mind,” he rushed on. “There is a fresh crop of English gentlemen arriving this season, and you will be meeting all of them.”

Impoverished gentlemen, he meant. “Viscounts” and “earls” and assorted “sirs” who were in desperate need of a wealthy wife, even if she were American.

Mariah didn’t have to ask why Papa wanted her out of New York. Away from the influence of her crazy mother. Away from the gossip. He wanted to secure her future, her security … and, above all, her sanity. But there were some things the human will, however indomitable, could not overcome.

“I don’t wish to leave New York,” she said, meeting his gaze. “Not so long as Mama needs me.”

“You’ve spent enough time in asylums,” he said harshly. “You can’t make your mother any better, there or here.” He pinched the bridge of his nose. “She wants your happiness. You know that, Merry.” His commanding tone became persuasive, almost gentle. “You’d make her happiest in these … last days by marrying well and starting on the road to having your own family.”

Mariah pressed her palms to her hot cheeks. She wanted children. She wanted them badly. But if she should inherit the madness that had claimed her mother and her mother’s mother before her.

Papa was blinded by the hope that she would be different. He still intended to see that she climbed to the heights of society, high enough to sneer at the snobbish “old money” of New York. And the surest way of achieving his goal was by trading money for a title.

As if that would make a difference.

I don’t need it, Papa. Oh, I can ape the manners of a fine lady, but I don’t belong among them. I’ve been by myself too long. All I want is a quiet life. Then, if anything goes wrong …

“I can’t, Papa. You know I can’t.”

“I know you can.” He was all brute force now, the man who had brought the New York Stock Exchange to its knees more than once, and in spite of herself, she quailed. “You will. And you’ll begin next week, when the Viscount Ainscough arrives.” He turned his back on her. “Mrs. Abercrombie is throwing a ball for him. She has invited you.”

Mariah wondered how Papa had wangled such an invitation. Perhaps Mr. Abercrombie hoped to encourage a substantial investment from Mr. Marron and had prevailed upon his wife to accept the former pariah.

“—you’ll be wearing a new gown and looking like a queen,” Papa was saying.

“I don’t need more gowns, Papa.”

“You will from now on. A new one for every concert, soirée, breakfast and party during the Season.”

Mariah rose and walked to the window, looking out over Central Park. Leaves were turning and beginning to fall. Mrs. Abercrombie’s ball was only the beginning. Soon the Season would be in full bloom, and she would be in the thick of it, as if Mama didn’t exist.

“I know it’s difficult for you, sweetheart,” Papa said, coming up behind her and laying his broad hand on her shoulder. “But you’ll carry on. You’re stronger than …”

Stronger than your mother. You won’t hear voices. You’ll behave normally. You won’t ever end up in a … “Promise that you won’t send Mama back to the asylum,” she said.

He looked at her with that shrewd, hard gaze. “Are you trying to bargain with me, Merry?”

“Keep her here. Let me see her between engagements, and I’ll become whatever you want me to be.”

His shoulders sagged. “I don’t want to send her back. I only want what’s best.” He seemed to shrink to the size of an ordinary man. “I agree.”

All the air rushed out of Mariah’s lungs. “Thank you, Papa.”

He waved his hand, dismissing her words, and returned to his desk. “The ivory gown from Worth just arrived from Paris,” he said, as if they had never discussed anything more important than her wardrobe. “You’ll wear that one to the ball. We’ll have to use a few local couturiers until the rest arrive.”

“Yes, Papa.” Mariah drew her finger across the window-pane, watching her breath condense on the glass. “How many Englishmen do you suppose I’ll have to choose from?”

“I imagine you’ll snag a duke, Merry. How could any man resist you?”

And what about love? Wasn’t she as unlikely to find that with an English lord as with anyone in New York? Was there a man anywhere who didn’t want her only for her money?

Papa would use every means necessary to quash any current gossip about the state of Mrs. Marron’s sanity, of course. Sufficient wealth could buy almost everything. Everything but what really mattered.

Mariah walked to the door. “I’d best get ready for dinner, Papa.”

“You do that. Wear that little pink frock, the one with the lace at the bottom. Bring some cheer to the table.”

She nodded, left the office and climbed the stairs, acknowledging the nurse who was just leaving Mama’s suite. As she entered her room, she wondered if she might possibly escape marriage entirely. Papa thought her beautiful, but she knew that to be untrue. She was, in fact, a nobody. She had a considerable allowance of her own. Perhaps she could bribe the noblemen to leave her alone. Then Papa would have to give up, and she could find a way to be with Mama until the end.

But things didn’t work out as she’d planned. Halfway through the Season she met the dashing Earl of Donnington, already wealthy in his own right, and fell in love. He wanted a quiet, unassuming wife who would be content to remain at his estate in Cambridgeshire while he pursued his own interests; she could think of no better arrangement.

A few months later, Mama died. Mariah insisted on the full period of mourning, but Donnington waited patiently. A year later, she was on a steamer bound for England and the marriage her father had so wanted for her. The end of one life and the beginning of another.

And she never heard a single voice in her head.

CHAPTER ONE

Cambridgeshire, 1885

IT HAD BEEN no marriage at all.

Mariah crossed the well-groomed park as she had done every day for the past few months, her walking boots leaving a damp trail in the grass. Tall trees stood alone or in small clusters, strewn about the park in a seemingly random pattern that belied the perfect organization of the estate.

Donbridge. It was hers now. Or should have been.

No one will ever know what happened that night.

The maids had blushed and giggled behind their hands the next morning when she had descended from her room into the grim, dark hall with its mounted animal heads and pelts on display. She had run the gauntlet of glassy, staring eyes, letting nothing show on her face.

They didn’t know. Neither did Vivian, the dowager Lady Donnington, for all her barely veiled barbs. Giles had left too soon … suspiciously soon. But no one would believe that the lord of Donbridge had failed to claim his husbandly rights.

Was it me? Did he sense something wrong?

She broke off the familiar thought and walked more quickly, lifting her skirts above the dew-soaked lawn. She was the Countess of Donnington, whether or not she had a right to be. And she would play the part. It was all she had, now that Mama was gone and Papa believed her safely disposed in a highly advantageous marriage.

Lady Donnington. In name only.

A bird called tentatively from a nearby tree. Mariah turned abruptly and set off toward the small mere, neatly oblong and graced by a spurting marble fountain. One of the several follies, vaguely Georgian in striking contrast to the Old English manor house, stood to one side of the mere. It had been built in the rotunda style, patterned after a Greek temple, with white fluted columns, a domed roof and an open portico, welcoming anyone who might chance by.

A man stood near the folly … a shadowy, bent figure she could not remember ever having seen before. One of the groundskeepers, she thought.

But there was something very odd about him, about the way he started when he saw her and went loping off like a three-legged dog. A poacher. A gypsy. Either way, someone who ought not to be on the estate.

Mariah hesitated and then continued toward the folly. The man scuttled into the shrubbery and disappeared. Mariah paused beside the folly, considered her lack of defenses and thought better of further pursuit.

As she debated returning to the manor, a large flock of birds flew up from the lakeshore in a swirl of wings. She shaded her eyes with one hand to watch them fly, though they didn’t go far. What seemed peculiar to her was that the birds were not all of one type, but a mixture of what the English called robins, blackbirds and thrushes.

She noticed at once that the folly seemed to have attracted an unusual variety of wildlife. She caught sight of a pair of foxes, several rabbits and a doughty badger. The fact that the rabbits had apparently remained safe from the foxes was remarkable in itself, but that all should be congregating so near the folly aroused an interest in Mariah that she had not felt since Giles had left.

Kneeling at the foot of the marble steps, she held out her hands. The rabbits came close enough to sniff her fingers. The badger snuffled and grunted, but didn’t run away. The foxes merely watched, half-hidden in the foliage. Mariah heard a faint sound and glanced up at the folly. The animals melted into the grass as she stood, shook out the hem of her walking skirt and mounted the steps.

The sound did not come again, but Mariah felt something pulling her, tugging at her body, whispering in her soul. Not a voice, precisely, but—

Her heart stopped, and so did her feet. You’re imagining things. That’s all it is.

Perhaps it would be best to go back. At least she could find solace in the old favorite books she’d begun to read again, and the servants would leave her alone.

But then she would have to endure her mother-in-law’s sour, suspicious glances. You drove him away, the dowager’s eyes accused. What is wrong with you?

She dismissed the thought and continued up to the portico. There were no more unexpected animal visitors. The area was utterly silent. Even the birds across the mere seemed to stand still and watch her.

The nape of her neck prickling, Mariah walked between the columns and listened. It wasn’t only her imagination; she could hear something. Something inside the small, round building, beyond the door that led to the interior.

She tested the door. It wouldn’t budge. She walked completely around the rotunda, finding not a single window or additional door. Air, she supposed, must enter the building from the cupola above, but the place was so inaccessible that she might almost have guessed that it had been built to hide a secret … a secret somebody didn’t want anyone else to find.

Perhaps this was where her prodigal husband stored the vast quantity of guns he must need to shoot the plethora of game he so proudly displayed on every available wall of the house.

But why should he hide them? He was certainly not ashamed of his bloody pastime, of which she’d been so ignorant when she’d accompanied him to England.

Defying the doubts that had haunted her since Giles’s departure, she searched the portico and then the general area around the folly. Impulse prompted her to look under several large, decoratively placed stones.

The key was under the smallest of them. She flourished it with an all-too-fleeting sense of triumph, walked back up the stairs and slipped the key in the lock.

The door opened with a groan. Directly inside was a small antechamber with a single chair and a second door. The room smelled of mice.

That was what you heard, she thought to herself. But she also detected the scent of stale food. Someone had eaten in here, sitting on that rickety chair. Perhaps even that man she’d seen loitering about the place with such a suspicious air.

But why?

She stood facing the inner door, wondering if the key would fit that lock, as well.

Leave well enough alone, she told herself. But she couldn’t. She walked slowly to the door and tried the key.

It worked. Though the lock grated terribly and gave way only with the greatest effort on her part, the door opened.

The smell rolled over her like the heavy wetness of a New York summer afternoon. A body left unwashed, the stale-food odor and something else she couldn’t quite define. She was already backing away when she saw the prisoner.

He crouched at the back of the cell, behind the heavy bars that crossed the semicircular room from one wall to the other. The first thing Mariah noticed was his eyes … black, as black as her husband’s but twice as brilliant, like the darkest of diamonds. They were even more striking when contrasted with the prisoner’s pale hair, true silver without a trace of gray. And the face.

It didn’t match the silver hair. Not in the least. In fact, it looked very much like Lord Donnington’s. Too much.

She backed away another step. I’m seeing things. Just like Mama. I’m.

With a movement too swift for her to follow, the prisoner leaped across the cell and crashed into the bars. His strong, white teeth were bared, his eyes crazed with rage and despair. He rattled his cage frantically, never taking his gaze from hers.

Mariah retreated no farther. She was not imagining this. Whoever this man might be, he was being held captive in a cell so small that no matter how he had begun, he must surely have been driven insane. A violent captive who, should he escape, might strangle her on the spot.

A madman.

Her mouth too dry for speech, Mariah stood very still and forced herself to remain calm. The man’s body was all whipcord muscle; the tendons stood out on his neck as he clutched the bars, and his broad shoulders strained with tension. He wore only a scrap of cloth around his hips, barely covering a part of him that must have been quite impressively large. Papa, for all his talk of her “starting a family,” would have been shocked to learn that she knew about such matters, and had since she first visited Mama in the asylum at the age of fourteen.

The prisoner must have noticed the direction of her gaze, because his silent snarl turned into an expression she could only describe as “waiting.”

“I beg your pardon,” she said, knowing how ridiculous the words sounded even as she spoke them. “May I ask … do you know who you are?”

Anyone else might have laughed at so foolish a question. But Mariah knew the mad often had no idea of their own identities. She had seen many examples of severe amnesia and far worse afflictions at the asylum.

The prisoner tossed back his wild, pale mane and closed his mouth. It was a fine mouth above a strong chin, identical to Donnington’s in almost every way. Only his hair and his pale skin distinguished him from the Earl of Donnington.

Surely they are related. The prospect made the situation that much more horrible.

“My name,” she said, summoning up her courage, “is Mariah.”

He cocked his head as if he found something fascinating in her pronouncement. But when he opened his mouth as if to answer, only a faint moan escaped.

It was all Mariah could do not to run. Perhaps he’s mute. Or worse.

“It’s all right,” she said, feeling she was speaking more to a beast than a man. “No one will hurt you.”

His face suggested that he might have laughed had he been able. Instead, he continued to stare at her, and her heart began to pound uncomfortably.

“I want to help you,” she said, the words out of her mouth before she could stop them.

The man’s expression lost any suggestion of mirth. He touched his lips and shook his head.

He understands me, Mariah thought, relief rushing through her. He isn’t a half-wit. He understands.

Self-consciousness froze her in place. He was looking at her with the same intent purpose as she had looked at him … studying her clothing, her face, her figure.

She swallowed, walked back through the door, picked up the chair and carried it into the inner chamber. She placed it as far from the cage as she could and sat down. It creaked as she settled, only a little noisier than her heartbeat. The prisoner stood unmoving at the bars.

“I suppose,” Mariah said, “that it won’t do any good to ask why you are here.”

His lips curled again in a half snarl. He didn’t precisely growl, but it was far from a happy sound.

“I understand,” she said, swallowing again. “I can leave, if you wish.”

She almost hoped he would indicate just such a desire, but he shook his head in a perfectly comprehensible gesture. Ah, yes, he certainly understood her.

The ideas racing through her mind were nearly beyond bearing. Who had put him here?

There are too many similarities. He and Giles must be related. A lost brother. A cousin. A relative not once mentioned by anyone in the household.

Insane thoughts. It was her dangerously vivid imagination at work again.

And yet.

This prisoner had obviously not been meant to be found. And with Donnington gone, she couldn’t ask for an explanation.

Dark secrets. It didn’t surprise Mariah that Donbridge had its share.

This man is not just a secret. He’s a human being who needs your help.

She twisted her gloved hands in her lap. “I won’t leave,” she said softly. “Do you think you can answer a few simple questions by moving your head?”

His black eyes narrowed. Indeed, why should he trust her? He was being treated like an animal, his conditions far worse than anything Mama had ever had to endure.

She examined the cage. It was furnished with a single ragged blanket, a basin nearly empty of water and a bowl that presumably had once contained food.

“Are you hungry?” she asked.

He pushed away from the bars and began to pace, back and forth like a leopard at the zoo. She had an even clearer glimpse of his fine, lithe body: his graceful stride, the ripple of muscle in his thighs and shoulders, the breadth of his chest, the narrow lines of his hips and waist.

Heat rushed into her face, and she lifted her eyes. He had stopped and was staring again. Reading her shameful thoughts. Thoughts she hadn’t entertained since that night two months ago when she’d lain in her bed, waiting for Donnington to make her his bride in every way.

“Shall I bring you food?” she asked quickly. “A cut of beef? Or venison?”

He shook his head violently, shuddering as if she’d offered him dirt and grass. But the leanness of his belly under his ribs told her she dared not give up.

“Very well, then,” she said. “Fresh bread? Butter and jam?”

His gaze leaped to hers.

“Yes,” she said. “I’ll bring you bread. And fruit? I remember seeing strawberries in the conservatory.”

Hope. That was what she saw in him now, though he moved no closer to the bars. Who saw to his needs? She had no way of knowing and had every reason to assume the worst.

“You also require clothing,” she said. “I’ll bring you a shirt and trousers.” His eloquent face was dubious. “They should … they ought to fit you very well.”

Because he and Donnington were as close to twins as any two men Mariah had ever seen.

The Man in the Iron Mask had always been one of her favorite stories. The true king imprisoned, while the brother ruled in his stead.

“Your feet must be sore,” she went on, her words tripping over themselves. “I can bring you shoes and stockings, and … undergarments, as well. Blankets, of course, and pillows. What else?” She pretended not to notice how ferociously focused he was on her person. “A comb. Shaving gear. Fresh water. Towels.”

The prisoner listened, his head slightly cocked as if he didn’t entirely take her meaning. Had he been so long without such simple comforts? Yet his face lacked even the shadow of a beard, his hair was not unclean, and his body, though not precisely fragrant, was not as dirty as one might expect.

Again she wondered who looked after him. Someone on the estate knew every detail of this man’s existence, and she intended to find the jailer.

She resolved, in spite of her fears, to try a new and dangerous tack. “Do you … do you know Lord Donnington?”

His reaction was terrifying. He flung himself against the bars and banged at them with his fists. Mariah started up from the chair, prepared to run, then stopped.

This was more than mere madness, more than rage. This was pain, crouched in the shadows beneath his eyes, etched into the lines framing his mouth. He reached through the bars, fist clenched. Mariah held her ground. Gradually his hand relaxed, the fingers stretching toward her. Pleading. Begging her to overcome her natural fear.

Drawn by forces beyond her control, Mariah took a step toward him. Inch by inch she crossed the five feet between them. By the tiniest increments she lifted her hand and touched his.

His fingers closed around hers, tightly enough to hurt. His strength was such that he could have pulled her into the bars and strangled her in an instant. But he was shaking, perspiration standing out on his forehead beneath the pale shock of hair, his mouth opening and closing on low, guttural sounds she had no way of interpreting.

Desperation. Yearning. A final effort to make someone listen to the words he couldn’t speak.

“It will be all right,” she said. “I will help you.”

His shaking began to subside, though he refused to let go of her hand. But now he was astonishingly gentle, running his thumb in a featherlight caress over her wrist. It was her turn to shiver, though she fought the overwhelming sensations that coursed through her body and pooled between her legs.

Oh, God.

“Please,” she whispered. “Let me go.”

He did, but only with obvious reluctance. She took a steadying step back, but not so far that he would become upset again.

Her feelings meant nothing. Not when he needed her so much—this stranger who had captured her mind and heart within a few vivid minutes.

“I …” She struggled to find words that wouldn’t alarm him. “I must go now. I’ll come back soon with the things you need. I promise.”

He gazed at her as if he were trying to memorize everything about her. As if he didn’t believe her. As if he expected never to see her again.

“I promise,” she repeated, and retreated toward the door. His broad shoulders sagged in defeat, and she knew there was no more she could say to him now; he would not trust her until she returned.

Her stomach taut with foreboding, she picked up the chair, moved it back to its place in the antechamber and continued through the door. The prisoner made not a sound. She poked her head out the second door, saw no one, left the chamber and hastily locked the door.

She leaned against it for a moment, breathing fast, until she was certain of her composure. Then she assured herself that there was no observer in the vicinity, replaced the key under the stone and set out for the house.

He hates Donnington, she thought, sickened by the implications of the prisoner’s reaction. Why? And what if he knew that I am Lady Donnington?

It didn’t bear thinking of. And it didn’t really matter. She would do exactly as she said. Help him, as she hadn’t been able to help Mama.

Perhaps that would be enough to save her.

DO YOU KNOW who you are?

He had understood the question, but he had not been able to answer it, just as he had been unable to tell the female what he wanted above all else.

Freedom. Memory. All the bright and beautiful things that had been stolen from him, though he had no recollection of what they had actually been.

She had not known him, though he had seen her before. She had been present on that day of pain and turmoil, when he had tried to escape his captors. The female.

Woman, he reminded himself, pronouncing the word inside his mind. The woman who had been with the man, his tormentor, in that time he couldn’t remember.

She had been afraid then, as he had been afraid. She had fallen and grown quiet, so quiet that he had believed her dead. Then Donnington had taken her away, and he had been compelled to endure this numb emptiness of captivity.

Until today. Until she had come to him with her soft voice and a warm, half-familiar scent gathered in the heavy folds of her strange garments.

And asked him who he was.

He backed against the wall and slid down until he was crouching on the cold floor. He had greeted her with rage, for that was all he had known for so long. He had flung himself against the bars, ignoring the pain searing into his flesh, and sought to drive her away even as the silent voice within begged her to stay.

And she had stayed. She had told him her name.

Mariah. He rolled the name over his tongue, though it emerged as a moan. Ma-ri-ah. It was a good sound. One that he might have spoken with pleasure if his mouth would obey his commands.

I want to help you.

He grunted—a sound of amusement he had heard in some other life—and remembered the first thought that had come to him then. He had wanted her to open the cage door, but not merely to release him. He had wanted her to come inside, remove the heavy weight of fabric that bound her, open her arms to him and kneel beside him. He would place his head in her lap, and then … and then.

With a shudder, he flung back his head and plunged his fingers into his hair. There was still so little he grasped, so little he understood, yet he knew why she drew him. Male and female. It had been the same in that long-ago he had only begun to put together in his mind.

But never like this. Never like her.

Once more he tried to remember the events that had brought him to this cage. He pieced together terrible images of being violently reborn in this world, finding himself horribly changed, hearing a harsh and unlovely voice that made no sense. Men had taken him and carried him to this place where the taint of iron held him prisoner as surely as the bars themselves.

For the first while after he had been locked inside, he had staggered about on his two awkward legs, bumping into the high curved walls and fighting for balance. When at last he was able to walk, he had circled the room again and again, looking for a way out that did not exist.

They had left him alone for two risings of the sun, though he could see nothing but filtered light through the holes in the roof high above. Then another man, ugly and bent, had brought him food, water and a scrap of cloth to cover the most vulnerable part of his body. The man hadn’t spoken to him, and after a few days he had realized that his keeper was as mute as he. When the man had returned, he had flung a slab of flesh, saturated with the smell of newly shed blood, into the cell.

Stomach churning with disgust, he hadn’t touched it. It wasn’t until after another sun’s rise that the men had brought him things he could eat. Fruit. Bread. The same things the girl had promised him.

Girl. Mariah. She had seen only a man in him, not what he had been.

He had been mighty once. No one had dared.

Who am I?

There must be an answer. Mariah had promised to help him. He had believed her, until she had spoken the word he hated with all his heart.

Donnington.

He leaped up again, clenching and unclenching his fists, those useless appendages that could do nothing but pull at the bars until his palms were burned and raw.

And yet she had let him hold her hand.

He struggled to compose a picture of her eyes, far brighter than the sky lost somewhere above him. Captivating him. Holding him frozen with need.

Donnington. She spoke as if she knew him well; she had asked if he knew the man, and she was not afraid of him. He could not trust her, despite all her gentle speech.

No. He must learn to understand her—and himself. And until he could speak in her tongue, there could be no further communication.

He returned to his corner and began to memorize every word she had spoken.

MARIAH REACHED THE house in ten minutes, shook the worst of the wetness out of her skirts and strode into the entrance hall. As always, it was dark and grim, with its heavy wood paneling and mounted heads, daring the casual visitor to penetrate the manor’s secrets. She walked at a fast pace for the stairs, hoping to avoid the dowager Lady Donnington.

She was out of luck. Just as if Vivian had anticipated her return, she swept out of the main drawing room and accosted Mariah at the foot of the staircase.

“Lady Donnington,” she said, a false smile on her handsome face. Her gaze swept down to Mariah’s hem. “I see that you have been out walking again. How very industrious of you.”

Mariah faced her. “I must contrive to keep myself occupied somehow, Lady Donnington,” she said, “considering my current state of solitude.”

“Yes. Such a pity that my son felt the need to leave so suddenly after your wedding.”

It was the same unpleasant veiled accusation the dowager had flung at her immediately after Donnington had left. You were never really his wife, Vivian’s look said. You drove him away.

Mariah lifted her chin. “I assure you,” she said, “he was not in the least displeased with me.”

If her statement had been truly a lie, she might not have been able to pull it off. But it was at least half-true, for Donnington had shown no more disgust for her than he had affection. He’d simply ignored her, remained in his own room and left the next morning.

He’d said he loved her. Had it been the money, after all? Plenty of wealthy men could never be content with what they had, and she’d brought a large marriage settlement, in addition to her own separate inheritance.

But surely no healthy man would choose not to take advantage of his marriage bed. The other reasons why he might have left her alone were disturbing. And that was why, if the dowager did believe that her son hadn’t consummated the marriage, she must feel compelled to blame that fact on Mariah.

“I’m certain that Giles will return to us very soon,” Mariah said calmly.

“Let us hope you are correct.” Vivian’s stare scoured Mariah to the bone. “You had best go up and change, my dear. Donnington would never approve of your wild appearance.”

And of course he would not. The quiet unassuming wife he’d desired must be proper at all times.

Mariah nodded brusquely and continued up the stairs. Halfway to the landing, she paused and turned. “By the way,” she said, “Donnington doesn’t have any brothers besides Sinjin, does he?”

“Why … why do you ask such a question?”

The outrage in the dowager’s voice told Mariah that she had made a serious mistake. “I do apologize,” she said. “It was only a dream I had last night.”

“A dream?” The older woman followed Mariah up the stairs. “A dream about my son?”

“It was nothing. If you will excuse me …”

Mariah continued to the landing, Vivian’s stare burning into her back, and went quickly to her room.

A hidden brother. How could she have been so stupid? It was all too bizarre to be credible. If she hadn’t seen the prisoner with her own eyes.

You did see him. You touched him. He is real.

Preoccupied with such disturbing thoughts, Mariah opened the door to find one of the chambermaids—Nola, that was her name—crouched before the fireplace, cleaning the grate.

“Oh!” the maid cried, leaping to her feet. “Lady Donnington! I’m so sorry.” She curtseyed, so nervous that she dropped her broom and nearly upset the contents of her scuttle. She bent to snatch the broom up again.

Mariah tossed her hat on the bed. “I’m not angry, Nola,” she said.

The girl, her face smudged above the starched collar of her uniform, paused to meet Mariah’s gaze. “Thank you, your ladyship,” she said, her country accent a little thicker as she relaxed. “I’ll be gone in a trice.”

“No need to hurry.” Mariah sank into the chair by her dressing table and pulled the pins from her hair. She knew she ought to ring for her personal maid, Alice, but she had no desire to be fussed over now.

Not after what had happened an hour ago. Not after visiting a prisoner who had been treated so abominably, worse than any of the patients she had encountered in the asylum.

“Your ladyship?”

Mariah looked up. Nola was standing with her scuttle and supplies, watching Mariah anxiously. “Are you all right?”

It was a presumptuous question from a servant, at least by English lights. Mariah took no offense.

“I’m fine,” she said. She took a better look at the girl, wondering why she hadn’t really noticed her before. Nola must have been close to eighteen, with a round, rather plain face, vivid red hair tucked under her cap, light gray eyes, and a mouth that must smile frequently when she wasn’t in the presence of her supposed betters. “How are you, Nola?”

The girl couldn’t have been more surprised. “I … I am very well, your ladyship.”

As well as anyone could be in this mausoleum of a house, Mariah thought. But Nola’s reply gave her a sudden peculiar notion. If there was one thing she’d learned, both at home and at Donbridge, it was that the servants—from the steward to the lowliest scullery maid—always knew everything that went on in a household. If anyone at Donbridge had heard of a prisoner in the folly, they would have done so.

But she had to be very careful not to frighten Nola. Mariah had few enough allies, and Nola, so easily ignored by everyone else, might be just the ticket. “Sit down, Nola,” she said.

The maid looked about wildly as if someone had threatened to cut her throat. “I—I should go, your ladyship.”

“I’d like to have a talk, if you don’t mind.”

She realized how she sounded as soon as she spoke. Nola undoubtedly believed she was in for a scolding for being caught cleaning up, and that was the last thing Mariah wanted her to think.

“You’re not in any trouble,” Mariah said. “I really only want to talk. I’m alone here, you see.”

Comprehension flashed across the girl’s face. “You … you wish to talk to me, your ladyship?”

“Yes. Please, sit down.”

Nola returned to the fireplace, set down her scuttle and brushed off her skirts before venturing onto the carpet again. She sat gingerly in the chair next to the hearth, her back rigid.

“Don’t be concerned, Nola,” Mariah said. “I’d like to ask you a few questions about the house, if you don’t mind.”

“I … of course, your ladyship.”

Mariah folded her hands in her lap, hoping she looked sufficiently unthreatening. “How long have you been here, Nola?”

“Well … mmm … almost six months, your ladyship.”

“You must observe a great deal of what goes on at Donbridge.”

Nola blanched, and Mariah knew she’d moved too fast. “I realize you really don’t know me well, Nola,” she said. “If you don’t feel comfortable confiding in me …”

“Oh, no, your ladyship! You’ve never been anything but kind to everyone.” She paused, evidently amazed by her own frankness. “It must be very different in America.”

“In many ways it is.” Mariah leaned forward a little. “The former Lady Donnington hasn’t been kind, has she?”

Nola glanced toward the door. “Why should she care about the likes of us?”

That was close to downright rebellion. Mariah might have smiled if not for her more sober purpose. “I don’t believe she cares much about anyone but her son.”

The girl dropped her gaze. “That’s not for me to say, your ladyship.”

“Please don’t call me that, Nola. My name is Mariah.”

A stubborn expression replaced the unease on Nola’s face. “It isn’t right, your ladyship.”

The subject certainly wasn’t worth arguing over. “Very well. But this is very important, Nola. I believe you can help me with something that matters a great deal to me. Will you answer my questions honestly?”

The armchair creaked as Nola shifted her weight. “Yes, your ladyship.”

“Do you know if Lord Donnington has a relative … a cousin, perhaps … who looks very much like him?”

Nola’s eyes widened. “A cousin, your ladyship?”

“Anyone who might resemble him strongly, except for the color of his hair.”

Mariah thought that Nola would have bolted from her chair and out the door if she’d thought she could get away with it. But the maid must have seen that Mariah was very serious indeed, for she gave up the battle.

“There are rumors,” she whispered, her head still half-cocked toward the door. “Only rumors, your ladyship.”

“What sort of rumors?”

“Of someone … someone being kept at Donbridge.”

“Kept against their will?”

Nola shivered. “Yes, your ladyship.”

This conversation was proving to be far more productive than Mariah could have hoped. “Do the rumors tell why?” she asked.

The maid shook her head anxiously.

“It’s all right, Nola. Do you know who is supposed to be guarding this prisoner?”

She could almost feel the girl’s trembling. “There’s a strange man who lives in a cottage at the edge of the estate. They say he never speaks, and no one knows what he does. I heard—”

CHAPTER TWO

FOOTSTEPS SOUNDED IN the corridor outside, and Nola leaped from her seat.

“Begging your pardon, your ladyship,” she gasped. “I must go!”

She was out of the room before Mariah could rise from her own chair. She listened for a moment, hearing the rapid patter of Nola’s feet as she hurried toward the servants’ stairs. There would be no more questioning her today, that was certain.

But she’d confirmed what Mariah had already surmised; the prisoner’s captivity was not a complete secret. Was it possible that she’d been too hasty in assuming that Vivian didn’t know about it?

Could she have kept such a secret from her own daughter-in-law for the ten weeks since Mariah had arrived at Donbridge? A secret her son must share.

Mariah shook her head. She was jumping to conclusions, which was a very dangerous habit. She had no evidence whatsoever, only the prisoner’s reaction to Donnington’s name. And confronting Vivian directly was unthinkable. Mariah could only hope that Nola wouldn’t go running directly to the dowager, though the tone of dislike in the maid’s voice when she’d spoken of her former mistress suggested she wouldn’t. Nevertheless, their conversation might very well be the talk of the house by noon.

You’ve gone about this the wrong way, Mariah told herself. In her eagerness to discover the truth, she’d trusted a girl she knew nothing about. She’d made wild assumptions based upon one meeting with a man she didn’t know.

But that man still needed her. From now on, she had to be extremely cautious. If Nola held her tongue, no one else should guess what Mariah had discovered. She must, with utmost discretion, collect the things the prisoner required.

There was only one place in Donbridge where she might find them. It wouldn’t be difficult to enter Donnington’s rooms; they were directly next door to her own, with a small dressing room between them. And there was no time to waste.

Donnington hadn’t locked his door. Mariah stepped into his room, briefly arrested by the faint smell of the man she’d married. He was prone to using a certain cologne, one she had liked when he was courting her.

She had never been in his suite before. It was his domain, like his study and the billiard room. The furniture was unmistakably masculine, and Donnington had managed to find space on the walls to mount a few more of the smaller animal heads.

Shaking off an uncomfortable blend of disgust and regret, Mariah went directly to his wardrobe. She opened one of the drawers, selected appropriate undergarments—which might have made her blush, had she not seen far worse at the asylum—chose two of the shirts he’d left behind, then moved quickly to the trousers. Stockings were next, along with a pair of walking shoes that had seen hard use. She filched the towels from his washstand, along with a spare shaving kit, a comb and a bar of soap.

She paused, quite in spite of herself, to glance in his mirror, wondering what Donnington had seen in her.

Black, slightly waving hair, now loose around her shoulders. An oval face with rather common blue eyes, straight brows, and a well-shaped nose and mouth. Not pretty, perhaps, but perfectly acceptable.

Was it really my fault that he left? Did he find out about Mama, despite all Papa’s efforts to buy off anyone who might tattle?

Mariah turned away from the mirror and glanced once more about the room. A waistcoat? No, that was hardly necessary now. A jacket. The prisoner would need its warmth in that cold chamber, though it might be pleasant enough outside. She returned to the wardrobe and removed one of Donnington’s hunting jackets, the one he preferred to wear on the estate. Searching for something in which to wrap the clothing and supplies, she found a rucksack tucked in a corner of the room, along with several empty crates and a pair of lens-less binoculars.

Stuffing the clothing into the bag, she returned to her own room. On impulse, she went straight to her small bookcase, where she kept the books she’d loved as a child. Most were volumes of fairy tales, which for months after Mama’s death Mariah hadn’t dared to open.

Now she had some use for them. If the prisoner was capable of regaining his speech—presuming he’d ever had it to begin with—reading to him would surely assist in the process.

I can’t keep calling him the prisoner, she thought. But no appropriate name came to her.

She set down the bag, thumbed through a book of Perrault’s fairy tales and found the story of Cendrillon, Cinderella. When Mariah was very young, Mrs. Marron had liked to collect stories from every country.

Cinderella in the German language was Aschenbrödel. Mariah vaguely remembered a variation on the tale where the main character had been a boy, not a girl.

Aschen. Ash. Ashton was a proper name, especially in England.

“Ash.” She spoke the name aloud, nodded to herself and placed three of the books in the bag. Then she hid the bag under her bed. She would go out again tonight, when the dowager was asleep.

Caution. Discretion …

A knock at the door broke into her thoughts. It was Barbara, the parlor maid, who bobbed a curtsey as Mariah let her in.

“The dowager Lady Donnington requests your presence in the morning room, your ladyship,” she said, never meeting Mariah’s eyes.

Mariah wondered if Vivian had already heard about her conversation with Nola. “What does she want, Barbara?” she asked warily.

Barbara was clearly dismayed by Mariah’s directness. “Mr. Ware has come, your ladyship,” she said.

“Sinjin!” Mariah instantly forgot her worry and smoothed her skirts. Not that he would care about her appearance; he had excellent taste in ladies’ fashions and an extraordinary eye, but he was, after all, her brother-in-law. He and Mariah had been friends from their first meeting.

“Please inform the dowager that I’ll be down directly,” Mariah told the maid, who was off in a flash. Mariah glanced at the mirror over her washstand to make certain her pins were still in place, and then descended to the morning room.

St. John Ware rose to his feet as soon as she entered. He smiled at her … that sly, enigmatic smile that suggested he and she shared a secret no one else would ever know. Mariah nodded to the dowager and greeted Sinjin with an extended hand.

“Mr. Ware,” she said. “How delightful to see you again.”

He rolled his eyes at her unaccustomed formality and turned to Vivian. “The dowager was kind enough to let me in despite the early hour.”

Vivian looked askance at him. “And why should I not welcome my own son at any hour?” she asked crisply.

“Your scapegrace son,” he said. “Or ought that title now go to Donnington?”

The very room froze as Vivian understood his jest. She stiffened, her spine as rigid as one of Donnington’s elephant guns.

“You will not speak so of your elder brother,” she said.

Sinjin managed to seem chastened. “You’re quite right, Mother,” he said. “Please forgive me.”

Forgiveness was not in Vivian’s nature, but she nodded with the graciousness of a queen. “You may ring for tea.”

He moved swiftly to the bellpull and summoned Parish, the butler. Barbara arrived with the tray a short while later. The dowager poured without acknowledging Mariah’s right to do so.

She is still angry about the question I asked her, Mariah thought. But why? Is it merely because it might have implied …

“What brings you to Donbridge, Sinjin?” Vivian asked briskly.

Sinjin examined his fine china teacup. “Why shouldn’t I pay my respects to my own mother?”

“You have never shown much respect for anything, let alone your mother,” Vivian said.

“You quite wound me,” Sinjin said, too lightly to be reproachful. “I have the utmost respect for you, my dear.”

Vivian was incapable of being less than dignified, but she came very close to a snort. “What do you require, Sinjin? A loan for the repayment of your debts?”

Sinjin’s expression grew pained. “I am not so mercenary as you think, Mother.”

She sipped her tea delicately. “If you had gone into the army as your father intended, you would not be in such straits.”

For all the relative brevity of their acquaintance, Mariah knew how much Sinjin despised this topic. “Lady Donnington,” he said pointedly, “must find such a subject tedious, Mother.”

Mariah knew it would have been politic to absent herself, but Sinjin’s eyes begged her to stay, and she wasn’t of a mind to hand the dowager an easy victory. “The army is a fine vocation,” she said. “For those suited to it.”

“Indeed,” Sinjin said. “A vocation to which I could not have done proper justice.”

A teacup rattled in its saucer. Vivian waited while Barbara mopped up the almost invisible spillage where the dowager had set down her cup with a little too much force. “You do proper justice to very little,” she said in a brittle voice. “If your brother were here …”

“But he is not, is he?” Sinjin stood abruptly. “I shall not impose upon your sensibilities any longer.”

Vivian looked almost surprised at the vehemence beneath his veneer of unruffled courtesy. “There is no need for you to go.”

“But I cannot replace the earl as company for you and Lady Donnington,” he said. He bowed with soldierly precision, first to his mother and then to Mariah. “If you will excuse me …”

His stride was brisk as he left the room. Mariah excused herself with equal haste, earning a glare from the dowager, and hurried after him.

“Sinjin!”

He turned, slightly flushed, and doffed the hat he’d already retrieved from Barbara. “Lady Donnington,” he said. “I apologize for my hasty departure.”

“Oh, pish,” Mariah said. “Don’t come all formal with me, Sinjin.”

His anger evaporated into his usual good humor. “How you deal with her every day is beyond my capacity to understand.”

“No it isn’t. You’ve dealt with her all your life.”

He offered his arm, and she took it. They left the house, and Mariah was distracted by thoughts of Ash, so near and yet so far away.

Ask Sinjin. He would be glad to help.

But what if he already knew about the prisoner?

She refused to believe it. Not Sinjin. He was a good man.

As Donnington is not?

“A penny for your thoughts,” Sinjin said, peering at her face with his keen brown eyes. “You look positively pensive, my dear. Are you yearning for Donnington?”

“It’s nothing,” she said, refusing to rise to his bait.

“Ha! Mother won’t leave it alone, will she? How can she blame you?” He laughed. “Then again, how can she not? It’s in her nature. My brother can do no wrong.”

It wasn’t the first time the subject had come up between them, and ordinarily Mariah would have been glad for his sympathetic ear. But self-pity seemed very unimportant in light of this morning’s encounter.

“I do find it a bit odd that she has remained so calm,” he went on, oblivious. “I should have expected her to go a little mad, not knowing where her darling has gone.”

Mariah flinched at the mention of madness. It’s only a word, she thought. But it wasn’t. Not today. Not ever.

“Mariah.”

She looked into Sinjin’s eyes. He wasn’t laughing now. “How has it been with Mother?” he asked. “I am perfectly fine, Sinjin.”

He drew her hand from the crook of his arm and held it in his. “Has she made any sort of comment … any kind of intimation that you … that you might be …”

“Might be what?”

Seldom had she seen Sinjin look as uncomfortable as he did in that moment. “Seeing someone,” he said.

“Seeing someone? I see Lady Westlake, Lady Hurst …”

“A man, Mariah. Seeing a man.”

Slowly she began to take his meaning. “A man?” Her face grew hot. “Do you mean—”

But she really didn’t have to ask. He was talking about an affair. Something she’d only read about in books and heard of in the ghosts of rumors about a society to which she didn’t belong.

“Don’t look so shocked, Merry,” Sinjin said, using her nickname in the familiar way to which they both had become accustomed since her arrival at Donbridge. “You may not have much experience of the world, but I know you aren’t that naïve. Mother’s wanted an excuse to end your marriage to my brother ever since he brought you to England. She’d love to think the worst of you.” He sighed. “She mentioned to me once—just in passing, you understand—that she thought it odd that you spend so much time walking alone in the early mornings. Ridiculous, I know. There is no one in the world less likely to be unfaithful than you.”

But she scarcely heard his reassurances. All she could wonder was how long the dowager had harbored such suspicions. Since the very night Donnington had left? A week after? A month? Did she have someone specific in mind?

“I shouldn’t have spoken up,” Sinjin said, his voice tight with remorse. “I just thought that perhaps it would never occur to you that she might think such a thing. She isn’t quite rational when it comes to Donnie.”

Mariah removed her hand from Sinjin’s. “I’m glad you did,” she said. “I knew there was something more to her anger than blaming me for Donnington’s sudden absence.”

Sinjin puffed out his cheeks. “Well, then,” he said. “You’ve handled the whole thing admirably.” He caught her hand again and lifted it to his lips. “You know you may always count on me for anything.”

She managed a smile. “And you may count on me. I shall send a check for whatever you need.”

If he had been as mercenary as his mother supposed, he wouldn’t have looked so uneasy. “I’m not so badly off as all that. I shall recoup.”

“If only you’d stop the gambling—”

“For God’s sake, Merry. One Lady Donnington is quite enough.”

“I apologize. Sinjin …?”

“Hmm?”

“Are you very busy at Marlborough House?”

“Not terribly. I come and go. Why?”

“If you can spare the time, I might ask for your assistance.”

“With what?”

“I would prefer to explain when I have … certain additional information.”

“How very mysterious.” She could see he was about to make an unfortunate joke before he thought better of it. “Just as you wish, little sister.”

They turned and walked back to the house. After Sinjin had gone, Mariah wrote a letter to her banker in London, authorizing a transfer of funds to the Honourable St. John Ware. At least it was her money to do with as she chose, now that Parliament had passed the act allowing wives to keep at least some of their own wealth.

Somehow she made it through the rest of the day, trying not to think about what Sinjin had told her of Vivian’s suspicions. She wrote a cheerful letter to her father, sketched flowers in the garden and supervised the running of the household as much as the dowager permitted.

But she couldn’t forget. The dowager wanted to end her marriage to Donnington. She wanted to believe that Mariah was capable of being unfaithful to her husband, a notion that offended Mariah deeply.

And yet you already knew you must hide your next visit to the folly, she thought. Even if her reasons had been entirely innocent, based upon her desire to keep anyone else from learning that she had discovered Donbridge’s strange prisoner.

Now she had another reason for concealing her activities.

You are going to see a strange man. Alone.

For compassion. For justice, since some wrong had clearly been done. To Mariah, Ash was simply a patient in need of healing, a human being worthy of assistance and respect. And there would be bars between them … at least until she could determine what had happened and what must be done.

He touched your hand.

She shut the memory away and moved through the afternoon like a wraith. Dinner was an unpleasant affair, with long stretches of weighted silence and the occasional tart comment from the dowager. The elder Lady Donnington stared pointedly and repeatedly at the empty seat at the head of the table. Mariah imagined that she could hear Vivian’s thoughts.

I know why Donnington left you.…

There was no lingering at the table when dinner was finished. Mariah excused herself to her own rooms. Night fell at last, though the sky remained suspended in twilight until past ten.

The dowager was slow about going to bed, but Mariah waited until the house was silent. Then she retrieved her rucksack and raided the linen closet for blankets. The kitchen was dark save for a faint glow in the huge hearth; she entered the dry larder and found half a loaf of bread, along with several peaches from the conservatory. She chose a small knife from a row hung on the wall. She found an empty bottle and filled it with water from the kitchen tap.

She wrapped the food in a kitchen towel and then in one of the blankets, slung it over one shoulder and looped the rucksack over the other. Satisfied that she had the supplies she needed, she lit a lantern and passed quickly through the entrance hall.

It wasn’t a noise that made her stop, nor any sign of movement. But something caused her to look up at one of the heavy ceiling beams over the door, hung with a shield bearing the Donnington coat of arms.

Cave cornum meum: Beware my horn. The motto of the earls of Donnington was a silver unicorn rearing atop a blood-red field, ready to charge at any potential enemy.

There was no earthly reason to shiver. Mariah had seen the shield every time she left the house. But it troubled her now in a way she couldn’t understand.

Beware my horn.

Taking herself in hand, she opened the door and set off across the park. As always, the night was silent; there were faint rustlings of small creatures in the grass and shrubbery, but no indications of human presence. London was far away, and the nearest village was hardly a hotbed of activity so late at night.

She reached the folly in record time. No sound came from inside, and though she knew the heavy walls of the interior chamber were thick, she faced a moment of panic. She dropped the bag and blankets on the portico, rushed to the stone at the foot of the stairs and felt under it frantically.

The key was still there. No one had moved it. Ash must be where she had left him.

Wasting no further time, she unlocked the outer door and set the bag on the chair, laying the blanket with the food on the floor beside it. She hesitated just outside the inner door.

He’s ill, quite possibly mad. What will I do if I can’t save him?

The fear paralyzed her for all of ten seconds. Then she raised the lantern, set the key in the lock and opened the door.

Ash was waiting for her, pressed against the bars, clutching them with the same ferocity. His black gaze met hers, speaking just as eloquently as before.

Help me.

As if of their own accord, her eyes took him in as they had done that morning, cataloging every detail of his body. She had never seen her husband like this. She had glimpsed him once without his shirt, but that—and the brief touch of his lips and clasp of his hand—had been the extent of her experience with his body.

Would he look so magnificent, so powerful, so—

He is a patient. A patient, Mariah.

She turned away to collect the bag and blankets. “I’ve brought you some things you need,” she said. “Clothing, blankets, food. It isn’t nearly enough, but it should do for tonight.”

Without looking up to observe his reaction, she removed the clothing, food and books, and immediately laid the bread and fruit on the kitchen towel. Only then did she pause to consider the narrowness of the gap between the bars.

There would be no trouble, of course, with the bread or fruit. They could be cut. She wasn’t so certain about the bottle.

“You must be hungry,” she said, simply to fill the quiet. She selected one of the peaches, cutting off several small slices. Sweet juice coated her fingers, and she wiped the excess on the towel.

She rose and turned toward the cell. Ash hadn’t moved. Immediately she saw the second problem. In order to give him the food, she must venture within his reach.

You’ve done it before, she told herself. He won’t harm you. But she remembered too keenly how she had felt when he’d run his thumb up and down the back of her hand.

“I am going to give you the fruit,” she said slowly. “Do you understand?”

His dark gaze flickered to the slices of peach in her palm and back to her face. She moved closer. His eyes never wavered. She reached the bars and extended her hand just far enough that he could take the fruit.

He didn’t. Mariah was both puzzled and frustrated. Someone had fed him, though not generously. He wasn’t mad enough to require constant care, like an infant. Perhaps the problem was that he still had no reason to trust her.

“See?” she said, and took a bite of one of the slices. Juice trickled down her chin, and she licked her lips. “Delicious.”

His gaze moved from her eyes to her mouth. The floor gave the tiniest lurch under her feet.

“Here,” she said, pushing a piece through the bars. “Try it.”

He took the fruit as delicately as a butterfly alights on a flower petal. Long, strong fingers lifted it to his lips. With strange fascination, she watched him eat it with a kind of sensual deliberation, as if he were savoring every bite. When he finished, she saw what might have been real pleasure in his eyes.

“More?” she asked. She adjusted the knife to cut another slice, and the blade slipped. She felt a stab of pain as the sharp edge cut into her thumb. Blood welled on her skin.

Ash reached through the bars and grabbed her hand, pulling gently until her own fingers were inside the cell, and drew them into his mouth.

Sparklers exploded inside her head. She gasped. His tongue rolled over her skin as if seeking the wound. She closed her eyes, incapable of moving as he licked between her fingers and laved her thumb almost tenderly.

Her senses returned too late, and she snatched her hand away. Heat flowed through her arm, into her chest, and continued on to her stomach and thighs. Her most secret place ached as it never had before, not even when she had been most in love with Donnington.

But there was another unexpected change in her body. She examined her thumb. It no longer hurt. More remarkably, the cut was gone, leaving only a trace of pink healing flesh where it had been.

Impossible.

She set the peach on the towel, nearly dropping it in her haste. Her fingers trembled as she picked up a chunk of bread and placed it on one of the blankets. She didn’t dare allow Ash to accost her again.

Her second approach was far more cautious. She laid the blanket on the ground, several inches from the bars. Then she backed away and watched.

Lithe as a panther, he crouched and took the bread. He lifted his head and continued to watch her as he ate, not wolfing the food as one might expect him to do, but eating with all the finesse of a courtier at a prince’s table. Mariah put the rest down for him and withdrew again, half-ashamed that she should still be letting her fear rule her.

If it were only fear.

Ash made a sound in his throat. Mariah jumped, recovered, and saw that he had finished the bread. She remembered the water but could think of no way of giving it to him … unless she found a way to open the cell door.

It was unthinkable. She still knew nothing about him and was no closer to learning.

“Are you very thirsty?” she asked.

He lowered his chin, the veil of hair obscuring his eyes, and shook his head. She felt only a little relieved.

Remembering the blanket, she shook it out, refolded it and placed it at the foot of the bars again. Ash didn’t touch it. That uncanny stare continued to follow her as she bent all her attention on selecting one of the books.

Will he understand? Or is this all just wasted effort?

No, not wasted if there was the slightest chance of discovering just how much he could understand.

She sat in the chair, the chosen book in her lap, and set the lantern a little distance from her feet. It cast eerie shadows about the room and provided the bare minimum of light she would need to read. Her hand still tingled from the feel of Ash’s tongue on her flesh, and several times her fingers slipped from the pages.

At last she found her place. She cleared her throat.

“‘East of the Sun and West of the Moon,’” she read aloud.

Ash cocked his head, dropped into a crouch against the wall nearest the bars and let his hands dangle over his knees. As she began to read about the girl whose destitute father had given her to a mystical white bear in exchange for wealth and comfort, she began to wonder why she had chosen this tale, in particular, of all those in the book, or why this book of the three she had brought.

And she wondered—as she related how the girl had been visited every night by the same handsome prince, only to be deserted each morning—why, instead of the great white bear, she saw another creature, pale and elusive as a ghost, a beast very much like a horse but a thousand times more beautiful, his eyes black as a moonless night, his broad forehead topped by a glittering spiraled horn.

Startled, Mariah lost her place and looked at Ash. He was listening intently, but otherwise neither his posture nor his appearance had altered.

The Donnington coat of arms. Why should it so vividly come to mind at this moment? No one could have looked less like such a magical creature than Ash. It was certainly beyond any possibility that he should guess what fancies tumbled through her mind, and he looked entirely unresponsive to the story she was reading.

He doesn’t understand. How shall I ever hope to—

Suddenly he stood, moved to the bars and opened his mouth. His lips moved without producing any sound, but he pointed at the book and then gestured toward Mariah’s face.

“What is it?” she asked, half rising.

He gave a sharp, impatient gesture, and something very near anger crossed his features … not the savagery of their first meeting, but an arrogant, impatient emotion, as if he were no mere prisoner but a prince himself.

“You wish me to finish the story,” she said.

He nodded and gestured again toward the book. With a sensation quite unlike the satisfaction she had expected to feel at his response, she bent to the pages once more.

She related how the girl lived in luxury but saw no other person by day and only the prince by night. The girl became very lonely. One night, she bent to kiss the prince as he slept but woke him by letting drops of tallow fall on his shirt. He told her that he had been cursed by his wicked stepmother to be a bear by day and a man only by night, but that now he would be forced to leave her and marry a hideous troll.

Glancing up again to gauge Ash’s reaction, Mariah saw that his lips were forming a word she could almost make out: troll. It was if he recognized that one word out of all those she had spoken.

The possibility encouraged her. She continued the story until she’d reached the end, where the girl, who had undertaken a long and dangerous journey to reach her prince at the castle East of the Sun and West of the Moon, had helped him to outwit the trolls who held him captive.

“‘The old troll woman flew into such a rage that she burst into a thousand pieces, taking the troll princess with her. The bear prince and his love freed all the trolls’ captives, took the trolls’ gold and silver, and flew far away from the castle that lay East of the Sun and West of the Moon.’”

She closed the book and let it rest in her lap, watching Ash out of the corner of her eye. Frowning, he walked away from the bars and began to pace the length of his cage with his long, graceful stride.

Suddenly he swung around, his nostrils flared and his eyes unfathomable. He studied her so intently that her stomach began to feel peculiar all over again.

“Why a bear?” he asked.

CHAPTER THREE

ASTONISHED, SHE JUMPED up, nearly upsetting the chair, tripping on her skirts and stepping on the fruit that still lay on the towel. “You … you can speak!” she stammered.

He lifted his head and tossed his hair out of his eyes. “I speak,” he said. His voice was a lilting baritone with a slight English accent, unmistakably upper-class. “I.” He hesitated, gathering his words. “I speak now.”

Now. Which implied a before, a time … when? Before she had come? Before he had been confined to this tiny prison?

Why didn’t you tell me? Why didn’t you answer my simple questions?

But she didn’t ask aloud. She had made progress. If he had deliberately deceived her, it must have been because he hadn’t trusted her. All she’d done was read a fairy tale, and yet.

“Why a bear?” he repeated.

A whole army of questions marched through her mind, but the situation was far too chancy for her to ask them. The best thing she could do was play along.

“I don’t know,” she said. “It’s simply part of the story, the way the writer wanted to tell it.”

She could see the thoughts working behind his eyes. “But he became a … man.”

Excitement began to build in her chest. “Yes. When his curse was broken by the love of the girl.”

“Curse,” he said. His frown became a scowl so intimidating that she was glad of the bars between them. A moment later nothing but bewilderment showed on his face. “I don’t remember.”

“Don’t remember what?” she asked very quietly.

He gave her a long, appraising look. “You do not know?”

“I’m afraid …” She tossed aside the temptation to equivocate. “I didn’t realize you were here until this morning.”

If it were possible to swoon from nothing more than a stare, she might have forgotten that she’d never fainted in her life. She had the feeling that he could have snapped the bars in two if he’d put his mind to it.

“Who am I?” he asked.

As if she could answer. But surely he must have realized from her previous questions that she was as ignorant as he was.

“I don’t know,” she said, drawing the chair closer to the cage. “I wish I could tell you.”

“Donnington,” he said. Without hatred, only a calm indifference.

She braced herself. “What about Donnington?”

Ash gestured at the cage around him. “He … did this.”

The validation of her worst supposition made her ill enough to wish that she could run from the room and empty her roiling stomach.

This isn’t the Middle Ages. People don’t imprison other people for no reason.

And Ash was deeply troubled, even dangerous. There was no telling what was real in his mind and what imaginary. Who could know that better than she?

But Nola had heard the rumors about a captive on the grounds. And he looks like Donnington’s twin.…

She sucked in her breath. “You believe that Donnington put you here,” she said, matching Ash’s emotionless tone. “Do you know why?”

His hair flew as he shook his head again, on the very edge of violence. One moment calm, the next raging. Sure signs of insanity.

There would be no logical answers from him. Only the bits and pieces she could glean from the most cautious exploration. She must put from her mind the enticing contours of his body, the intensity of his eyes, the hunger.

She bent abruptly to gather up the spoiled fruit and left just long enough to toss it into the shrubbery outside. Ash was clutching the bars when she returned, his face pressed against them.

“I will not leave you,” she said, knowing her promise was only a partial truth. “I am your friend.”

“Friend,” he repeated.

“I care what happens to you. I want to help you.”

Belatedly she remembered the bottle of water she’d brought and considered the basin Ash’s keeper had left just inside the cage. She would have to take the risk of filling it with fresh water.

She crept toward the cage, knelt and poked the bottle’s neck through the bars. Ash made no move toward her, and she managed to fill the basin halfway before it became too difficult to pour. She glanced at the towels that still hung over the back of the chair. Rising, she wetted one thoroughly, walked back to the cage and held the moist towel up for Ash’s inspection.

“Wash,” she said, demonstrating for him by bathing her hands and face.

He followed her every movement, his gaze finally settling, as always, on her eyes. “Wash,” she repeated.

“Yes,” he said. “Wash.”

Her throat felt thick. “If I give this to you,” she said, “you must not touch me.”

He seemed to understand. When she extended the towel, he simply took it. No flesh touched flesh. But as he withdrew his hand, she saw something that made the squirming minnows in her middle seem like ravenous sharks.

His hands were burned. Red and black marks crossed his fingers and palms, stripes matching the bars he had so often grasped. There were similar stripes on his face. Even as she stared in horror, they began to diminish.

“Good God,” she whispered. Without hesitation, she seized his hand, wrapping it in the wet towel he still held. “How did you burn yourself?”

“Iron,” he said in a low voice.

“Iron? You mean the bars?” She touched one gingerly. They were cold, not hot.

“I don’t know how you did this,” she said tightly, “but your hands will need to be bandaged. And your face.” She looked up from her work. The brands across his jaw, cheeks and forehead were gone. She peeled the towel away from his hand. The marks were disappearing before her eyes.

She dropped his hand. It brushed the bar, and an angry red welt formed across his knuckles.